User login

Bullous Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Successfully Treated With Rituximab

Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus (BSLE) is a rare cutaneous presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).1 Although 59% to 85% of SLE patients develop skin-related symptoms, fewer than 5% of SLE patients develop BSLE.1-3 This acquired autoimmune bullous disease, characterized by subepidermal bullae with a neutrophilic infiltrate on histopathology, is precipitated by autoantibodies to type VII collagen. Bullae can appear on both cutaneous and mucosal surfaces but tend to favor the trunk, upper extremities, neck, face, and vermilion border.3

Our case of an 18-year-old black woman with BSLE was originally reported in 2011.4 We update the case to illustrate the heterogeneous presentation of BSLE in a single patient and to expand on the role of rituximab in this disease.

Case Report

An 18-year-old black woman presented with a vesicular eruption of 3 weeks’ duration that started on the trunk and buttocks and progressed to involve the face, oral mucosa, and posterior auricular area. The vesicular eruption was accompanied by fatigue, arthralgia, and myalgia.

Physical examination revealed multiple tense, fluid-filled vesicles, measuring roughly 2 to 3 mm in diameter, over the cheeks, chin, postauricular area, vermilion border, oral mucosa, and left side of the neck and shoulder. Resolved lesions on the trunk and buttocks were marked by superficial crust and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Scarring was absent.

Laboratory analysis demonstrated hemolytic anemia with a positive direct antiglobulin test, hypocomplementemia, and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Antinuclear antibody testing was positive (titer, 1:640).

Biopsies were taken from the left cheek for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and direct immunofluorescence (DIF), which revealed subepidermal clefting, few neutrophils, and notable mucin deposition. Direct immunofluorescence showed a broad deposition of IgG, IgA, and IgM, as well as C3 in a ribbonlike pattern at the dermoepidermal junction.

A diagnosis of SLE with BSLE was made. The patient initially was treated with prednisone, hydroxychloroquine, mycophenolate mofetil, and intravenous immunoglobulin, but the cutaneous disease persisted. The bullous eruption resolved with 2 infusions of rituximab (1000 mg) spaced 2 weeks apart.

The patient was in remission on 5 mg of prednisone for 2 years following the initial course of rituximab. However, she developed a flare of SLE, with fatigue, arthralgia, hypocomplementemia, and recurrence of BSLE with tense bullae on the face and lips. The flare resolved with prednisone and a single infusion of rituximab (1000 mg). She was then maintained on hydroxychloroquine (200 mg/d).

Three years later (5 years after the initial presentation), the patient presented with pruritic erythematous papulovesicles on the bilateral extensor elbows and right knee (Figure 1). The clinical appearance suggested dermatitis herpetiformis (DH).

Punch biopsies were obtained from the right elbow for H&E and DIF testing; the H&E-stained specimen showed lichenoid dermatitis with prominent dermal mucin, consistent with cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Direct immunofluorescence showed prominent linear IgG, linear IgA, and granular IgM along the basement membrane, which were identical to DIF findings of the original eruption.

Further laboratory testing revealed hypocomplementemia, anemia of chronic disease (hemoglobin, 8.4 g/dL [reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL]), and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Given the clinical appearance of the vesicles, DIF findings, and the corresponding SLE flare, a diagnosis of BSLE was made. Because of the systemic symptoms, skin findings, and laboratory results, azathioprine was started. The cutaneous symptoms were treated and resolved with the addition of triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily.

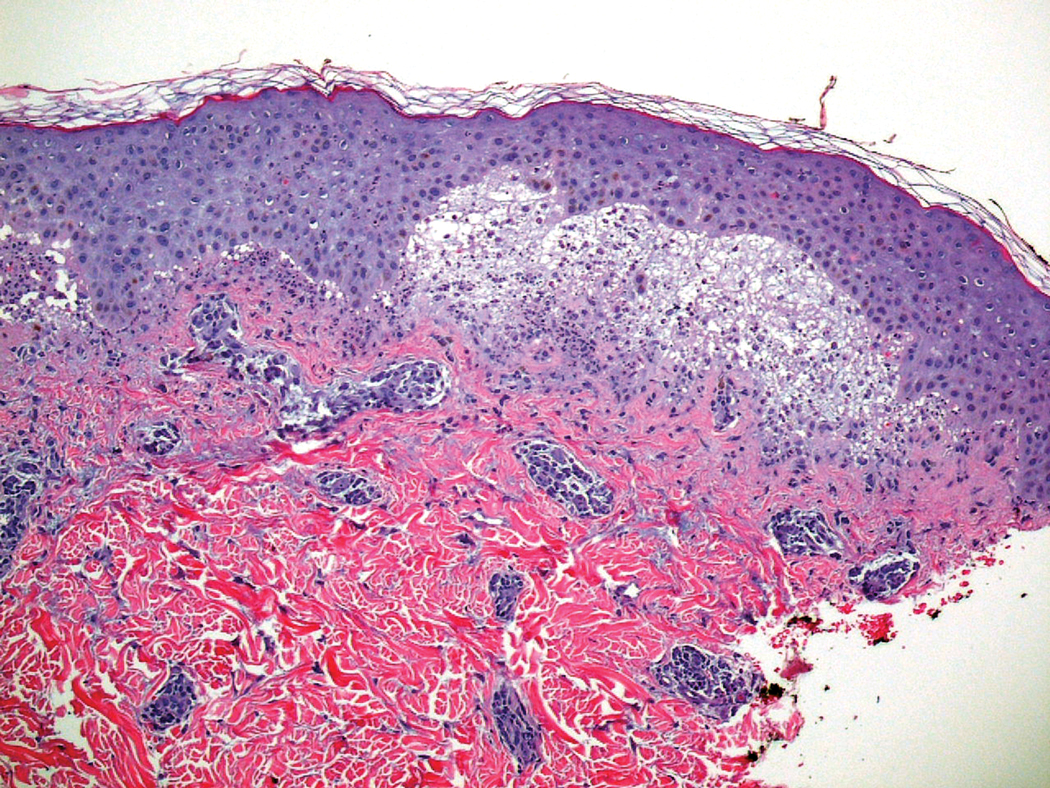

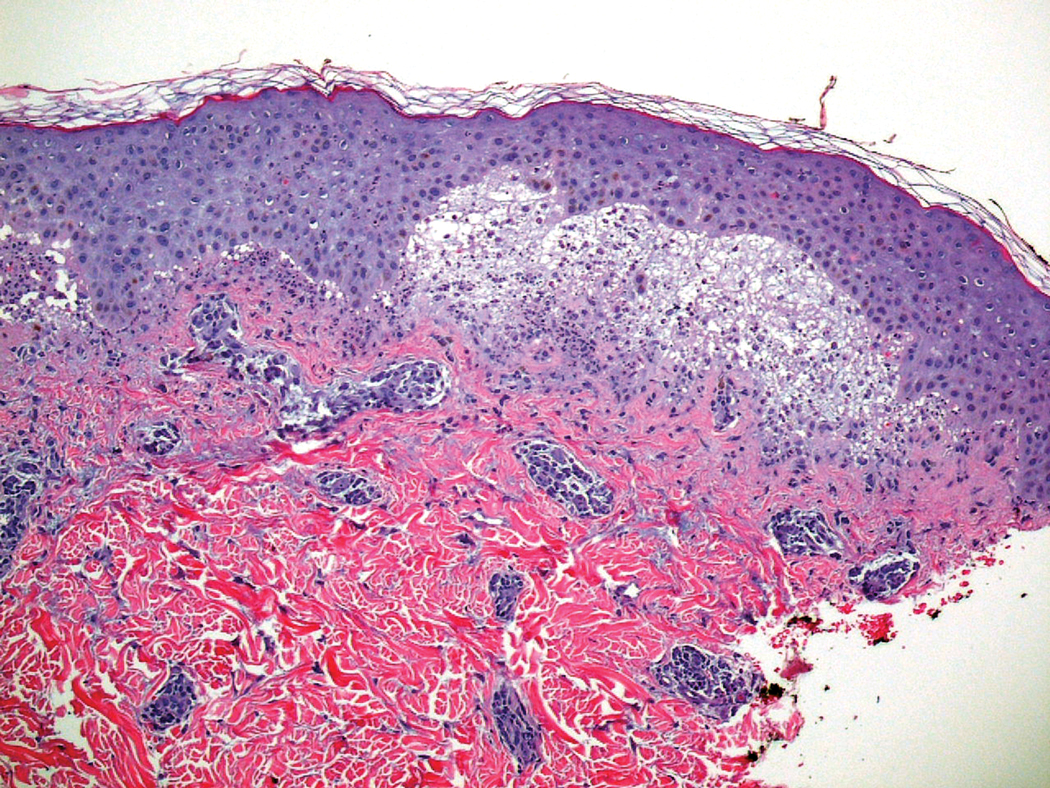

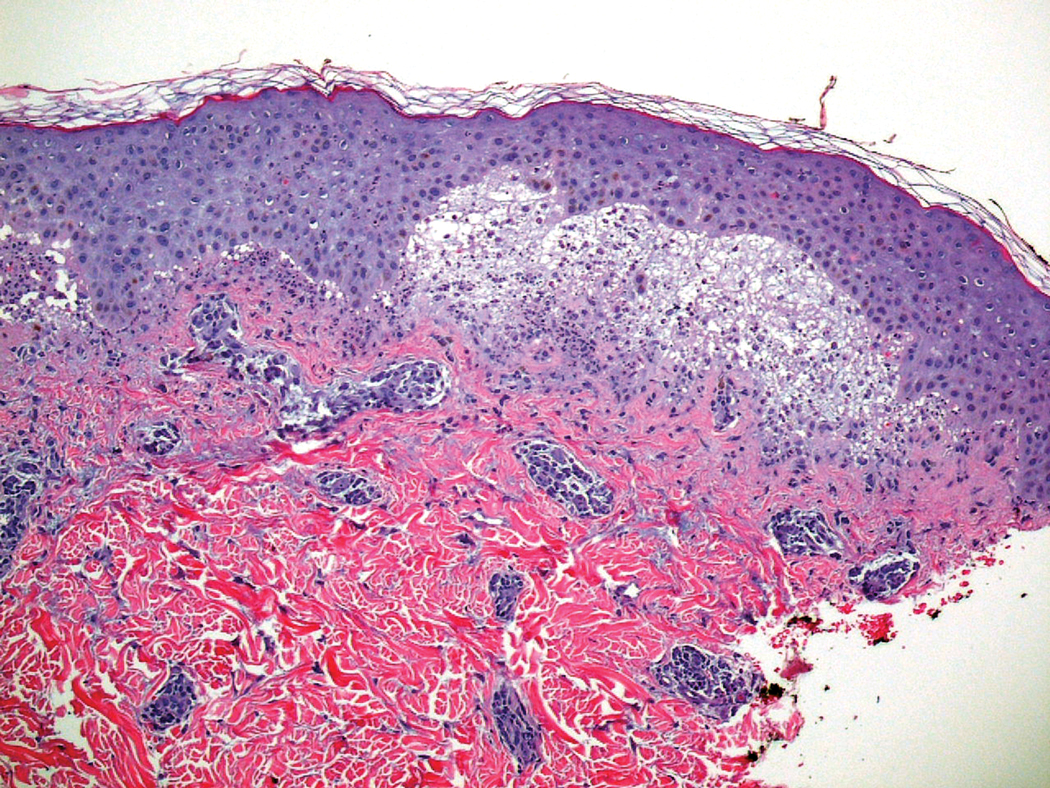

Six months later, the patient presented to our facility with fatigue, arthralgia, and numerous erythematous papules coalescing into a large plaque on the left upper arm (Figure 2). Biopsy showed interface dermatitis with numerous neutrophils and early vesiculation, consistent with BSLE (Figure 3). She underwent another course of 2 infusions of rituximab (1000 mg) administered 2 weeks apart, with resolution of cutaneous and systemic disease.

Comment

Diagnosis of BSLE

Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus is a rare cutaneous complication of SLE. It typically affects young black women in the second to fourth decades of life.1 It is a heterogeneous disorder with several clinical variants reported in the literature, and it can be mistaken for bullous pemphigoid, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA), linear IgA bullous dermatosis, and DH.1-3 Despite its varying clinical phenotypes, BSLE is associated with autoantibodies to the EBA antigen, type VII collagen.1

Current diagnostic criteria for BSLE, revised in 1995,5 include the following: (1) a diagnosis of SLE, based on criteria outlined by the American College of Rheumatology6; (2) vesicles or bullae, or both, involving but not limited to sun-exposed skin; (3) histopathologic features similar to DH; (4) DIF with IgG or IgM, or both, and IgA at the basement membrane zone; and (5) indirect immunofluorescence testing for circulating autoantibodies against the basement membrane zone, using the salt-split skin technique.

Clinical Presentation of BSLE

The classic phenotype associated with BSLE is similar to our patient’s original eruption, with tense bullae favoring the upper trunk and healing without scarring. The extensor surfaces typically are spared. Another presentation of BSLE is an EBA-like phenotype, with bullae on acral and extensor surfaces that heal with scarring. The EBA-like phenotype usually is more difficult to control. Lesions appearing clinically similar to DH have been reported, either as DH associated with SLE (later postulated to have been BSLE) or as herpetiform BSLE.1,4,7-10

Histopathology of BSLE

The typical histologic appearance of BSLE is similar to DH or linear IgA bullous dermatosis, with a predominantly neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrate in the upper dermis and a subepidermal split. Direct immunofluorescence shows broad deposition of IgG along the basement membrane zone (93% of cases; 60% of which are linear and 40% are granular), with approximately 70% of cases showing positive IgA or IgM, or both, at the basement membrane zone. Indirect immunofluorescence performed on 1 M NaCl salt-split skin showed staining on the dermal side of the split, similar to EBA.11

Treatment Options

Rapid clinical response has been reported with dapsone, usually in combination with other immunosuppresants.1,2 A subset of patients does not respond to dapsone, however, as was the case in our patient who tried dapsone early in the disease course but was not effective. Other therapies including azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, and antimalarials have been used with some success.3

Rituximab, an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, has been used off label to treat BSLE cases that are resistant to dapsone, corticosteroids, and other immunosuppressants.12 Rituximab functions by depleting CD20+ B cells, thus altering the production of autoantibodies and, in the case of BSLE, reducing the concentration of circulating anti–type VII collagen antibodies. Rituximab was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 1997 for the treatment of non–Hodgkin lymphoma and later for chronic lymphocytic leukemia, rheumatoid arthritis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener granulomatosis), and microscopic polyangiitis.12 Off-label administration of rituximab to treat autoimmune bullous dermatoses has been increasing, and the drug is now approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat pemphigus vulgaris (as of June 2018).13

In 2011, Alsanafi et al12 reported successful treatment of BSLE with rituximab in a 61-year-old black woman who had rapid clearance of skin lesions. Our patient had rapid resolution of cutaneous disease with rituximab after the second infusion in a 2-infusion regimen. Interestingly, rituximab is the only agent that has reliably resulted in resolution of our patient’s cutaneous and systemic disease during multiple episodes.

There is little information in the literature regarding the duration of response to rituximab in BSLE or its use in subsequent flares. Our patient relapsed at 2 years and again 3 years later (5 years after the initial presentation). The original cutaneous outbreak and subsequent relapse had classic clinical and histological findings for BSLE; however, the third cutaneous relapse was more similar to DH, given its distribution and appearance. However, the histopathologic findings were the same at the third relapse as they were at the initial presentation and not reflective of DH. We propose that our patient’s prior treatment with rituximab and ongoing immunosuppression at presentation contributed to the more atypical cutaneous findings observed late in the disease course.

Conclusion

We report this case to highlight the heterogeneity of BSLE, even in a single patient, and to report the time course of treatment with rituximab. Although BSLE is considered a rare cutaneous complication of SLE, it is important to note that BSLE also can present as the initial manifestation of SLE.7 As such, BSLE should always be included in the differential diagnosis for a patient presenting with a bullous eruption and symptoms that suggest SLE.

This case also illustrates the repeated use of rituximab for the treatment of BSLE over a 5-year period and justifies the need for larger population-based studies to demonstrate the efficacy of rituximab in BSLE.

- Contestable JJ, Edhegard KD, Meyerle JH. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus: a review and update to diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:517-524.

- Camisa C. Vesiculobullous systemic lupus erythematosus. a report of four cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18(1, pt 1):93-100.

- Tincopa M, Puttgen KB, Sule S, et al. Bullous lupus: an unusual initial presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus in an adolescent girl. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:373-376.

- Burke KR, Green BP, Meyerle J. Bullous lupus in an 18-year-old. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:483.

- Yell JA, Allen J, Wojnarowska F, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus: revised criteria for diagnosis. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:921-928.

- Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumat. 1997;40:1725.

- Fujimoto W, Hamada T, Yamada J, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus as an initial manifestation of SLE. J Dermatol. 2005;32:1021-1027.

- Moncada B. Dermatitis herpetiformis in association with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1974;109:723-725.

- Davies MG, Marks R, Waddington E. Simultaneous systemic lupus erythematosus and dermatitis herpetiformis. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1292-1294.

- Burrows N, Bhogal BS, Black MM, et al. Bullous eruption of systemic lupus erythematosus: a clinicopathological study of four cases. Br J Dermatol. 1993;128:332-338.

- Sebaratnam DF, Murrell DF. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus. Dermatol Clin. 2011;29:649-653.

- Alsanafi S, Kovarik C, Mermelstein AL, et al. Rituximab in the treatment of bullous systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Rheumatol. 2011;17:142-144.

- Durable remission of pemphigus with a fixed-dose rituximab protocol. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:703-708.

Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus (BSLE) is a rare cutaneous presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).1 Although 59% to 85% of SLE patients develop skin-related symptoms, fewer than 5% of SLE patients develop BSLE.1-3 This acquired autoimmune bullous disease, characterized by subepidermal bullae with a neutrophilic infiltrate on histopathology, is precipitated by autoantibodies to type VII collagen. Bullae can appear on both cutaneous and mucosal surfaces but tend to favor the trunk, upper extremities, neck, face, and vermilion border.3

Our case of an 18-year-old black woman with BSLE was originally reported in 2011.4 We update the case to illustrate the heterogeneous presentation of BSLE in a single patient and to expand on the role of rituximab in this disease.

Case Report

An 18-year-old black woman presented with a vesicular eruption of 3 weeks’ duration that started on the trunk and buttocks and progressed to involve the face, oral mucosa, and posterior auricular area. The vesicular eruption was accompanied by fatigue, arthralgia, and myalgia.

Physical examination revealed multiple tense, fluid-filled vesicles, measuring roughly 2 to 3 mm in diameter, over the cheeks, chin, postauricular area, vermilion border, oral mucosa, and left side of the neck and shoulder. Resolved lesions on the trunk and buttocks were marked by superficial crust and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Scarring was absent.

Laboratory analysis demonstrated hemolytic anemia with a positive direct antiglobulin test, hypocomplementemia, and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Antinuclear antibody testing was positive (titer, 1:640).

Biopsies were taken from the left cheek for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and direct immunofluorescence (DIF), which revealed subepidermal clefting, few neutrophils, and notable mucin deposition. Direct immunofluorescence showed a broad deposition of IgG, IgA, and IgM, as well as C3 in a ribbonlike pattern at the dermoepidermal junction.

A diagnosis of SLE with BSLE was made. The patient initially was treated with prednisone, hydroxychloroquine, mycophenolate mofetil, and intravenous immunoglobulin, but the cutaneous disease persisted. The bullous eruption resolved with 2 infusions of rituximab (1000 mg) spaced 2 weeks apart.

The patient was in remission on 5 mg of prednisone for 2 years following the initial course of rituximab. However, she developed a flare of SLE, with fatigue, arthralgia, hypocomplementemia, and recurrence of BSLE with tense bullae on the face and lips. The flare resolved with prednisone and a single infusion of rituximab (1000 mg). She was then maintained on hydroxychloroquine (200 mg/d).

Three years later (5 years after the initial presentation), the patient presented with pruritic erythematous papulovesicles on the bilateral extensor elbows and right knee (Figure 1). The clinical appearance suggested dermatitis herpetiformis (DH).

Punch biopsies were obtained from the right elbow for H&E and DIF testing; the H&E-stained specimen showed lichenoid dermatitis with prominent dermal mucin, consistent with cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Direct immunofluorescence showed prominent linear IgG, linear IgA, and granular IgM along the basement membrane, which were identical to DIF findings of the original eruption.

Further laboratory testing revealed hypocomplementemia, anemia of chronic disease (hemoglobin, 8.4 g/dL [reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL]), and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Given the clinical appearance of the vesicles, DIF findings, and the corresponding SLE flare, a diagnosis of BSLE was made. Because of the systemic symptoms, skin findings, and laboratory results, azathioprine was started. The cutaneous symptoms were treated and resolved with the addition of triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily.

Six months later, the patient presented to our facility with fatigue, arthralgia, and numerous erythematous papules coalescing into a large plaque on the left upper arm (Figure 2). Biopsy showed interface dermatitis with numerous neutrophils and early vesiculation, consistent with BSLE (Figure 3). She underwent another course of 2 infusions of rituximab (1000 mg) administered 2 weeks apart, with resolution of cutaneous and systemic disease.

Comment

Diagnosis of BSLE

Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus is a rare cutaneous complication of SLE. It typically affects young black women in the second to fourth decades of life.1 It is a heterogeneous disorder with several clinical variants reported in the literature, and it can be mistaken for bullous pemphigoid, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA), linear IgA bullous dermatosis, and DH.1-3 Despite its varying clinical phenotypes, BSLE is associated with autoantibodies to the EBA antigen, type VII collagen.1

Current diagnostic criteria for BSLE, revised in 1995,5 include the following: (1) a diagnosis of SLE, based on criteria outlined by the American College of Rheumatology6; (2) vesicles or bullae, or both, involving but not limited to sun-exposed skin; (3) histopathologic features similar to DH; (4) DIF with IgG or IgM, or both, and IgA at the basement membrane zone; and (5) indirect immunofluorescence testing for circulating autoantibodies against the basement membrane zone, using the salt-split skin technique.

Clinical Presentation of BSLE

The classic phenotype associated with BSLE is similar to our patient’s original eruption, with tense bullae favoring the upper trunk and healing without scarring. The extensor surfaces typically are spared. Another presentation of BSLE is an EBA-like phenotype, with bullae on acral and extensor surfaces that heal with scarring. The EBA-like phenotype usually is more difficult to control. Lesions appearing clinically similar to DH have been reported, either as DH associated with SLE (later postulated to have been BSLE) or as herpetiform BSLE.1,4,7-10

Histopathology of BSLE

The typical histologic appearance of BSLE is similar to DH or linear IgA bullous dermatosis, with a predominantly neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrate in the upper dermis and a subepidermal split. Direct immunofluorescence shows broad deposition of IgG along the basement membrane zone (93% of cases; 60% of which are linear and 40% are granular), with approximately 70% of cases showing positive IgA or IgM, or both, at the basement membrane zone. Indirect immunofluorescence performed on 1 M NaCl salt-split skin showed staining on the dermal side of the split, similar to EBA.11

Treatment Options

Rapid clinical response has been reported with dapsone, usually in combination with other immunosuppresants.1,2 A subset of patients does not respond to dapsone, however, as was the case in our patient who tried dapsone early in the disease course but was not effective. Other therapies including azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, and antimalarials have been used with some success.3

Rituximab, an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, has been used off label to treat BSLE cases that are resistant to dapsone, corticosteroids, and other immunosuppressants.12 Rituximab functions by depleting CD20+ B cells, thus altering the production of autoantibodies and, in the case of BSLE, reducing the concentration of circulating anti–type VII collagen antibodies. Rituximab was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 1997 for the treatment of non–Hodgkin lymphoma and later for chronic lymphocytic leukemia, rheumatoid arthritis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener granulomatosis), and microscopic polyangiitis.12 Off-label administration of rituximab to treat autoimmune bullous dermatoses has been increasing, and the drug is now approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat pemphigus vulgaris (as of June 2018).13

In 2011, Alsanafi et al12 reported successful treatment of BSLE with rituximab in a 61-year-old black woman who had rapid clearance of skin lesions. Our patient had rapid resolution of cutaneous disease with rituximab after the second infusion in a 2-infusion regimen. Interestingly, rituximab is the only agent that has reliably resulted in resolution of our patient’s cutaneous and systemic disease during multiple episodes.

There is little information in the literature regarding the duration of response to rituximab in BSLE or its use in subsequent flares. Our patient relapsed at 2 years and again 3 years later (5 years after the initial presentation). The original cutaneous outbreak and subsequent relapse had classic clinical and histological findings for BSLE; however, the third cutaneous relapse was more similar to DH, given its distribution and appearance. However, the histopathologic findings were the same at the third relapse as they were at the initial presentation and not reflective of DH. We propose that our patient’s prior treatment with rituximab and ongoing immunosuppression at presentation contributed to the more atypical cutaneous findings observed late in the disease course.

Conclusion

We report this case to highlight the heterogeneity of BSLE, even in a single patient, and to report the time course of treatment with rituximab. Although BSLE is considered a rare cutaneous complication of SLE, it is important to note that BSLE also can present as the initial manifestation of SLE.7 As such, BSLE should always be included in the differential diagnosis for a patient presenting with a bullous eruption and symptoms that suggest SLE.

This case also illustrates the repeated use of rituximab for the treatment of BSLE over a 5-year period and justifies the need for larger population-based studies to demonstrate the efficacy of rituximab in BSLE.

Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus (BSLE) is a rare cutaneous presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).1 Although 59% to 85% of SLE patients develop skin-related symptoms, fewer than 5% of SLE patients develop BSLE.1-3 This acquired autoimmune bullous disease, characterized by subepidermal bullae with a neutrophilic infiltrate on histopathology, is precipitated by autoantibodies to type VII collagen. Bullae can appear on both cutaneous and mucosal surfaces but tend to favor the trunk, upper extremities, neck, face, and vermilion border.3

Our case of an 18-year-old black woman with BSLE was originally reported in 2011.4 We update the case to illustrate the heterogeneous presentation of BSLE in a single patient and to expand on the role of rituximab in this disease.

Case Report

An 18-year-old black woman presented with a vesicular eruption of 3 weeks’ duration that started on the trunk and buttocks and progressed to involve the face, oral mucosa, and posterior auricular area. The vesicular eruption was accompanied by fatigue, arthralgia, and myalgia.

Physical examination revealed multiple tense, fluid-filled vesicles, measuring roughly 2 to 3 mm in diameter, over the cheeks, chin, postauricular area, vermilion border, oral mucosa, and left side of the neck and shoulder. Resolved lesions on the trunk and buttocks were marked by superficial crust and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Scarring was absent.

Laboratory analysis demonstrated hemolytic anemia with a positive direct antiglobulin test, hypocomplementemia, and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Antinuclear antibody testing was positive (titer, 1:640).

Biopsies were taken from the left cheek for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and direct immunofluorescence (DIF), which revealed subepidermal clefting, few neutrophils, and notable mucin deposition. Direct immunofluorescence showed a broad deposition of IgG, IgA, and IgM, as well as C3 in a ribbonlike pattern at the dermoepidermal junction.

A diagnosis of SLE with BSLE was made. The patient initially was treated with prednisone, hydroxychloroquine, mycophenolate mofetil, and intravenous immunoglobulin, but the cutaneous disease persisted. The bullous eruption resolved with 2 infusions of rituximab (1000 mg) spaced 2 weeks apart.

The patient was in remission on 5 mg of prednisone for 2 years following the initial course of rituximab. However, she developed a flare of SLE, with fatigue, arthralgia, hypocomplementemia, and recurrence of BSLE with tense bullae on the face and lips. The flare resolved with prednisone and a single infusion of rituximab (1000 mg). She was then maintained on hydroxychloroquine (200 mg/d).

Three years later (5 years after the initial presentation), the patient presented with pruritic erythematous papulovesicles on the bilateral extensor elbows and right knee (Figure 1). The clinical appearance suggested dermatitis herpetiformis (DH).

Punch biopsies were obtained from the right elbow for H&E and DIF testing; the H&E-stained specimen showed lichenoid dermatitis with prominent dermal mucin, consistent with cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Direct immunofluorescence showed prominent linear IgG, linear IgA, and granular IgM along the basement membrane, which were identical to DIF findings of the original eruption.

Further laboratory testing revealed hypocomplementemia, anemia of chronic disease (hemoglobin, 8.4 g/dL [reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL]), and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Given the clinical appearance of the vesicles, DIF findings, and the corresponding SLE flare, a diagnosis of BSLE was made. Because of the systemic symptoms, skin findings, and laboratory results, azathioprine was started. The cutaneous symptoms were treated and resolved with the addition of triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily.

Six months later, the patient presented to our facility with fatigue, arthralgia, and numerous erythematous papules coalescing into a large plaque on the left upper arm (Figure 2). Biopsy showed interface dermatitis with numerous neutrophils and early vesiculation, consistent with BSLE (Figure 3). She underwent another course of 2 infusions of rituximab (1000 mg) administered 2 weeks apart, with resolution of cutaneous and systemic disease.

Comment

Diagnosis of BSLE

Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus is a rare cutaneous complication of SLE. It typically affects young black women in the second to fourth decades of life.1 It is a heterogeneous disorder with several clinical variants reported in the literature, and it can be mistaken for bullous pemphigoid, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA), linear IgA bullous dermatosis, and DH.1-3 Despite its varying clinical phenotypes, BSLE is associated with autoantibodies to the EBA antigen, type VII collagen.1

Current diagnostic criteria for BSLE, revised in 1995,5 include the following: (1) a diagnosis of SLE, based on criteria outlined by the American College of Rheumatology6; (2) vesicles or bullae, or both, involving but not limited to sun-exposed skin; (3) histopathologic features similar to DH; (4) DIF with IgG or IgM, or both, and IgA at the basement membrane zone; and (5) indirect immunofluorescence testing for circulating autoantibodies against the basement membrane zone, using the salt-split skin technique.

Clinical Presentation of BSLE

The classic phenotype associated with BSLE is similar to our patient’s original eruption, with tense bullae favoring the upper trunk and healing without scarring. The extensor surfaces typically are spared. Another presentation of BSLE is an EBA-like phenotype, with bullae on acral and extensor surfaces that heal with scarring. The EBA-like phenotype usually is more difficult to control. Lesions appearing clinically similar to DH have been reported, either as DH associated with SLE (later postulated to have been BSLE) or as herpetiform BSLE.1,4,7-10

Histopathology of BSLE

The typical histologic appearance of BSLE is similar to DH or linear IgA bullous dermatosis, with a predominantly neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrate in the upper dermis and a subepidermal split. Direct immunofluorescence shows broad deposition of IgG along the basement membrane zone (93% of cases; 60% of which are linear and 40% are granular), with approximately 70% of cases showing positive IgA or IgM, or both, at the basement membrane zone. Indirect immunofluorescence performed on 1 M NaCl salt-split skin showed staining on the dermal side of the split, similar to EBA.11

Treatment Options

Rapid clinical response has been reported with dapsone, usually in combination with other immunosuppresants.1,2 A subset of patients does not respond to dapsone, however, as was the case in our patient who tried dapsone early in the disease course but was not effective. Other therapies including azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, and antimalarials have been used with some success.3

Rituximab, an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, has been used off label to treat BSLE cases that are resistant to dapsone, corticosteroids, and other immunosuppressants.12 Rituximab functions by depleting CD20+ B cells, thus altering the production of autoantibodies and, in the case of BSLE, reducing the concentration of circulating anti–type VII collagen antibodies. Rituximab was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 1997 for the treatment of non–Hodgkin lymphoma and later for chronic lymphocytic leukemia, rheumatoid arthritis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener granulomatosis), and microscopic polyangiitis.12 Off-label administration of rituximab to treat autoimmune bullous dermatoses has been increasing, and the drug is now approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat pemphigus vulgaris (as of June 2018).13

In 2011, Alsanafi et al12 reported successful treatment of BSLE with rituximab in a 61-year-old black woman who had rapid clearance of skin lesions. Our patient had rapid resolution of cutaneous disease with rituximab after the second infusion in a 2-infusion regimen. Interestingly, rituximab is the only agent that has reliably resulted in resolution of our patient’s cutaneous and systemic disease during multiple episodes.

There is little information in the literature regarding the duration of response to rituximab in BSLE or its use in subsequent flares. Our patient relapsed at 2 years and again 3 years later (5 years after the initial presentation). The original cutaneous outbreak and subsequent relapse had classic clinical and histological findings for BSLE; however, the third cutaneous relapse was more similar to DH, given its distribution and appearance. However, the histopathologic findings were the same at the third relapse as they were at the initial presentation and not reflective of DH. We propose that our patient’s prior treatment with rituximab and ongoing immunosuppression at presentation contributed to the more atypical cutaneous findings observed late in the disease course.

Conclusion

We report this case to highlight the heterogeneity of BSLE, even in a single patient, and to report the time course of treatment with rituximab. Although BSLE is considered a rare cutaneous complication of SLE, it is important to note that BSLE also can present as the initial manifestation of SLE.7 As such, BSLE should always be included in the differential diagnosis for a patient presenting with a bullous eruption and symptoms that suggest SLE.

This case also illustrates the repeated use of rituximab for the treatment of BSLE over a 5-year period and justifies the need for larger population-based studies to demonstrate the efficacy of rituximab in BSLE.

- Contestable JJ, Edhegard KD, Meyerle JH. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus: a review and update to diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:517-524.

- Camisa C. Vesiculobullous systemic lupus erythematosus. a report of four cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18(1, pt 1):93-100.

- Tincopa M, Puttgen KB, Sule S, et al. Bullous lupus: an unusual initial presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus in an adolescent girl. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:373-376.

- Burke KR, Green BP, Meyerle J. Bullous lupus in an 18-year-old. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:483.

- Yell JA, Allen J, Wojnarowska F, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus: revised criteria for diagnosis. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:921-928.

- Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumat. 1997;40:1725.

- Fujimoto W, Hamada T, Yamada J, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus as an initial manifestation of SLE. J Dermatol. 2005;32:1021-1027.

- Moncada B. Dermatitis herpetiformis in association with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1974;109:723-725.

- Davies MG, Marks R, Waddington E. Simultaneous systemic lupus erythematosus and dermatitis herpetiformis. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1292-1294.

- Burrows N, Bhogal BS, Black MM, et al. Bullous eruption of systemic lupus erythematosus: a clinicopathological study of four cases. Br J Dermatol. 1993;128:332-338.

- Sebaratnam DF, Murrell DF. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus. Dermatol Clin. 2011;29:649-653.

- Alsanafi S, Kovarik C, Mermelstein AL, et al. Rituximab in the treatment of bullous systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Rheumatol. 2011;17:142-144.

- Durable remission of pemphigus with a fixed-dose rituximab protocol. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:703-708.

- Contestable JJ, Edhegard KD, Meyerle JH. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus: a review and update to diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:517-524.

- Camisa C. Vesiculobullous systemic lupus erythematosus. a report of four cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18(1, pt 1):93-100.

- Tincopa M, Puttgen KB, Sule S, et al. Bullous lupus: an unusual initial presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus in an adolescent girl. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:373-376.

- Burke KR, Green BP, Meyerle J. Bullous lupus in an 18-year-old. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:483.

- Yell JA, Allen J, Wojnarowska F, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus: revised criteria for diagnosis. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:921-928.

- Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumat. 1997;40:1725.

- Fujimoto W, Hamada T, Yamada J, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus as an initial manifestation of SLE. J Dermatol. 2005;32:1021-1027.

- Moncada B. Dermatitis herpetiformis in association with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1974;109:723-725.

- Davies MG, Marks R, Waddington E. Simultaneous systemic lupus erythematosus and dermatitis herpetiformis. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1292-1294.

- Burrows N, Bhogal BS, Black MM, et al. Bullous eruption of systemic lupus erythematosus: a clinicopathological study of four cases. Br J Dermatol. 1993;128:332-338.

- Sebaratnam DF, Murrell DF. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus. Dermatol Clin. 2011;29:649-653.

- Alsanafi S, Kovarik C, Mermelstein AL, et al. Rituximab in the treatment of bullous systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Rheumatol. 2011;17:142-144.

- Durable remission of pemphigus with a fixed-dose rituximab protocol. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:703-708.

Practice Points

- Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus (BSLE) can present with a waxing and waning course punctuated by flares.

- Different clinical presentations can occur over the disease course.

- Rituximab is a viable treatment option in BSLE.

Heparin-Induced Bullous Hemorrhagic Dermatosis Confined to the Oral Mucosa

Heparin is a naturally occurring anticoagulant and is commonly used to treat or prevent venous thrombosis or the extension of thrombosis.

Adverse effects of heparin administration include bleeding, injection-site pain, and thrombocytopenia. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is a serious side effect wherein antibodies are formed against platelet antigens and predispose the patient to venous and arterial thrombosis.

Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is a poorly understood idiosyncratic drug reaction characterized by tense, blood-filled blisters that arise following the administration of subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin or intravenous unfractionated heparin (UFH). First reported in 2006 by Perrinaud et al

Case Report

An 84-year-old man was admitted to the cardiology service with severe substernal chest pain. An electrocardiogram did not show any ST-segment elevations; however, he had elevated troponin T levels. He had a medical history of coronary artery disease complicated by myocardial infarction (MI), as well as ischemic cardiomyopathy, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, ischemic stroke, and pulmonary embolism for which he was on long-term anticoagulation for years with warfarin, aspirin, and clopidogrel. The patient was diagnosed with a non–ST-segment elevation MI. Accordingly, the patient’s warfarin was discontinued, and he was administered a bolus and continuous infusion of UFH. He also was continued on aspirin and clopidogrel. Within 6 hours of initiation of UFH, the patient noted multiple discrete swollen lesions in the mouth. Dermatology consultation and biopsy of the lesions were deferred due to acute management of the patient’s MI.

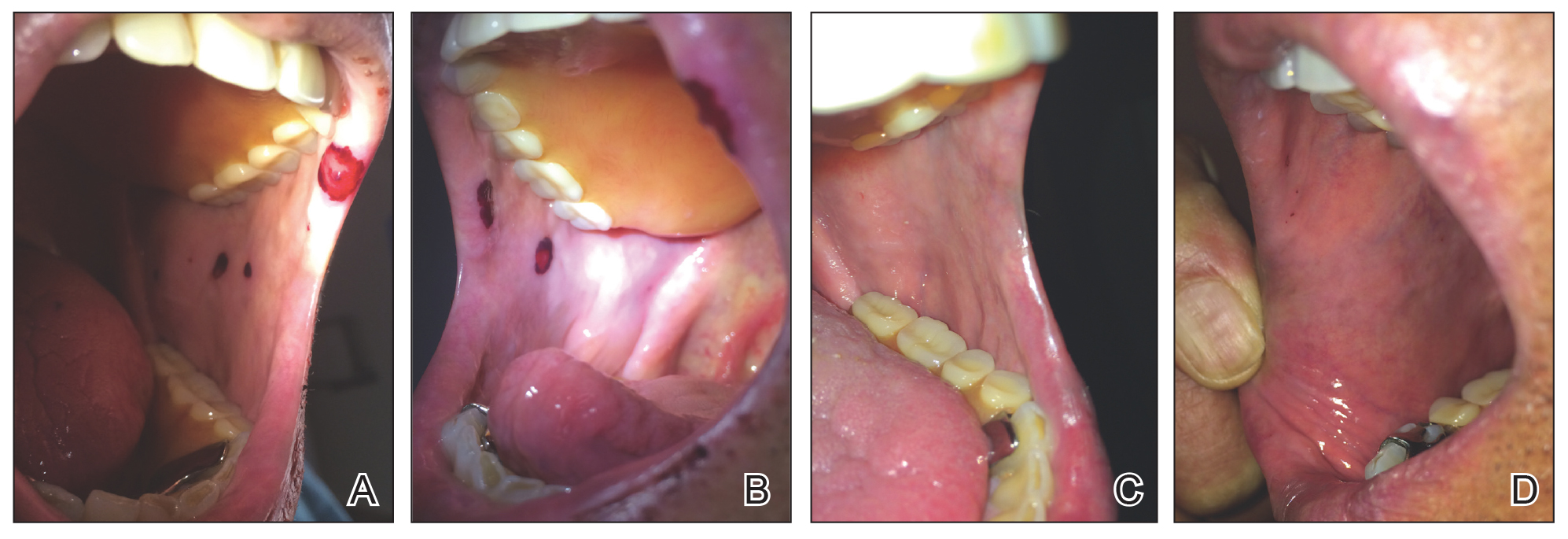

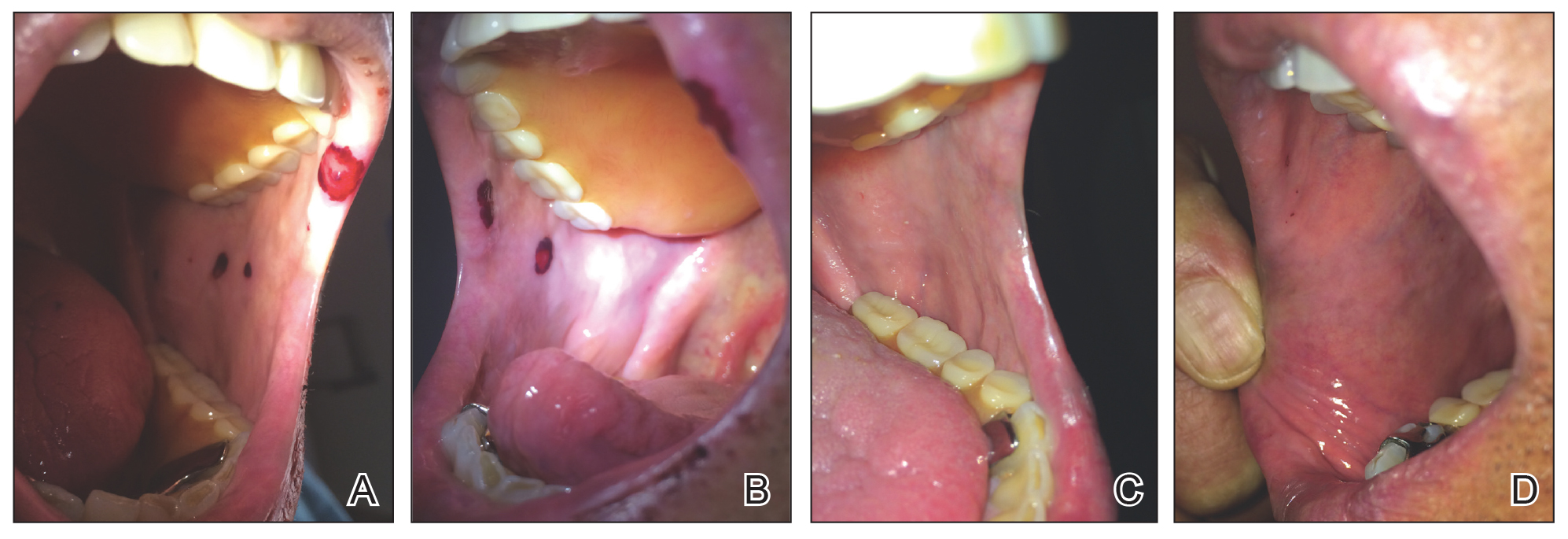

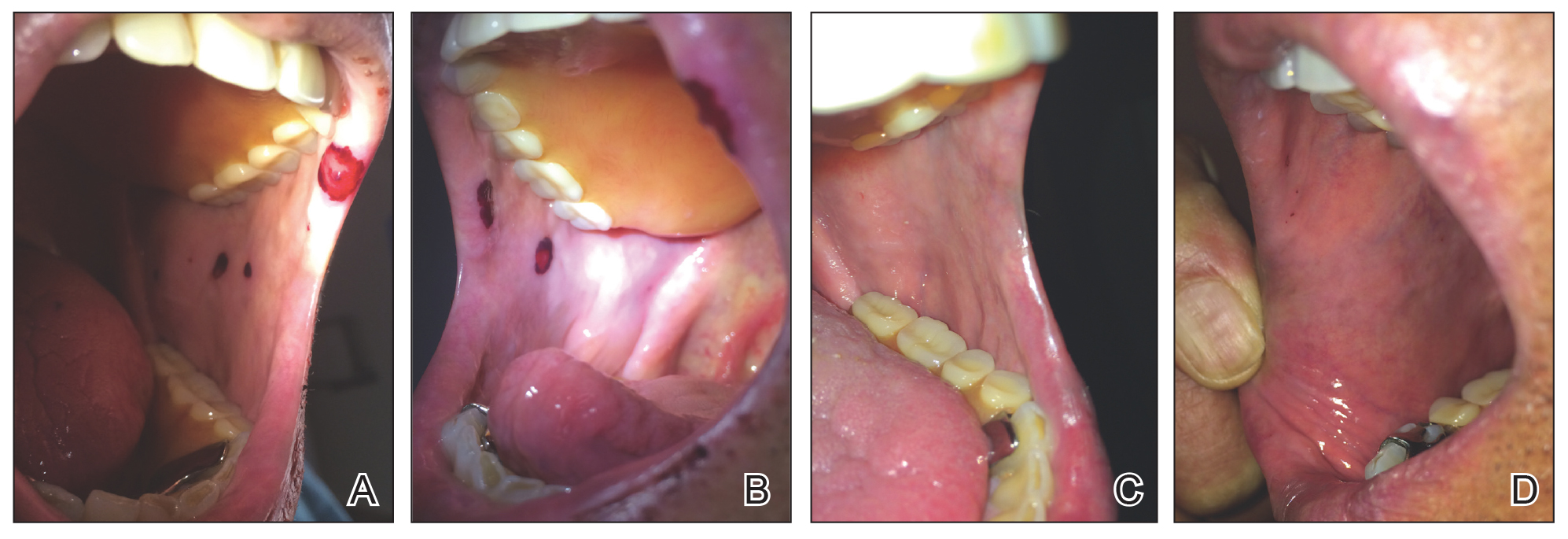

Physical examination revealed a moist oral mucosa with 7 slightly raised, hemorrhagic bullae ranging from 2 to 7 mm in diameter (Figure, A and B). One oral lesion was tense and had become denuded prior to evaluation. Laboratory testing included a normal platelet count (160,000/µL), a nearly therapeutic international normalized ratio (1.9), and a partial thromboplastin time that was initially normal (27 seconds) prior to admission and development of the oral lesions but found to be elevated (176 seconds) after admission and initial UFH bolus.

Upon further questioning, the patient revealed a history of similar oral lesions 1 year prior, following exposure to subcutaneous enoxaparin. At that time, formal evaluation by dermatology was deferred due to the rapid resolution of the blisters. Despite these new oral lesions, the patient was continued on a heparin drip for the next 48 hours because of the mortality benefit of heparin in non–ST-segment elevation MI. The patient was discharged from the hospital on a regimen of aspirin, warfarin, and clopidogrel. At 2-week follow-up, the oral lesions had resolved (Figure, C and D).

Comment

Heparin-Induced Skin Lesions

The 2 most common types of heparin-induced skin lesions are delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions and immune-mediated HIT. A 2009 Canadian study found that the overwhelming majority of heparin-induced skin lesions are due to delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions.

Types of HIT

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia is one of the most serious adverse reactions to heparin administration. There are 2 subtypes of HIT, which differ in their clinical significance and pathophysiology.

Type II HIT is an immune-mediated response caused by the formation of IgG autoantibodies against the heparin–platelet factor 4 complex. Antibody formation and thrombocytopenia typically occur after 4 to 10 days of heparin exposure, and there can be devastating arterial and venous thrombotic complications.

Diagnosis of HIT

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia should be suspected in patients with a lowered platelet count, particularly if the decrease is more than 50% from baseline, and in patients who develop stroke, MI, pulmonary embolism, or deep vein thrombosis while on heparin. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia was not observed in our patient, as his platelet count remained stable between 160,000 and 164,000/µL throughout his hospital stay and he did not develop any evidence of thrombosis.

Differential Diagnosis

Our patient’s lesions appeared morphologically similar to

Bullous pemphigoid also was considered given the presence of tense bullae in an elderly patient. However, the rapid and spontaneous resolution of these lesions with complete lack of skin involvement made this diagnosis less likely.12

Heparin-Induced Bullous Hemorrhagic Dermatosis

Because our patient described a similar reaction while taking enoxaparin in the past, this case represents an idiosyncratic drug reaction, possibly from antibodies to a heparin-antigen complex. Heparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is a rarely reported condition with the majority of lesions presenting on the extremities.

Conclusion

We describe a rare side effect of heparin therapy characterized by discrete blisters on the oral mucosa. However, familiarity with the spectrum of reactions to heparin allowed the patient to continue heparin therapy despite this side effect, as the eruption was not life-threatening and the benefit of continuing heparin outweighed this adverse effect.

- Gómez-Outes A, Suárez-Gea ML, Calvo-Rojas G, et al. Discovery of anticoagulant drugs: a historical perspective. Curr Drug Discov Technol. 2012;9:83-104.

- Noti C, Seeberger PH. Chemical approaches to define the structure-activity relationship of heparin-like glycosaminoglycans. Chem Biol. 2005;12:731-756.

- Bakchoul T. An update on heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: diagnosis and management. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2016;15:787-797.

- Schindewolf M, Schwaner S, Wolter M, et al. Incidence and causes of heparin-induced skin lesions. Can Med Assoc J. 2009;181:477-481.

- Perrinaud A, Jacobi D, Machet MC, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis occurring at sites distant from subcutaneous injections of heparin: three cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(2 suppl):S5-S7.

- Naveen KN, Rai V. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis: a case report. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:423.

- Choudhry S, Fishman PM, Hernandez C. Heparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis. Cutis. 2013;91:93-98.

- Villanueva CA, Nájera L, Espinosa P, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis at distant sites: a report of 2 new cases due to enoxaparin injection and a review of the literature. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:816-819.

- Ahmed I, Majeed A, Powell R. Heparin induced thrombocytopenia: diagnosis and management update. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83:575-582.

- Horie N, Kawano R, Inaba J, et al. Angina bullosa hemorrhagica of the soft palate: a clinical study of 16 cases. J Oral Sci. 2008;50:33-36.

- Rai S, Kaur M, Goel S. Angina bullosa hemorrhagica: report of 2 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:503.

- Lawson W. Bullous oral lesions: clues to identifying—and managing—the cause. Consultant. 2013;53:168-176.

Heparin is a naturally occurring anticoagulant and is commonly used to treat or prevent venous thrombosis or the extension of thrombosis.

Adverse effects of heparin administration include bleeding, injection-site pain, and thrombocytopenia. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is a serious side effect wherein antibodies are formed against platelet antigens and predispose the patient to venous and arterial thrombosis.

Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is a poorly understood idiosyncratic drug reaction characterized by tense, blood-filled blisters that arise following the administration of subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin or intravenous unfractionated heparin (UFH). First reported in 2006 by Perrinaud et al

Case Report

An 84-year-old man was admitted to the cardiology service with severe substernal chest pain. An electrocardiogram did not show any ST-segment elevations; however, he had elevated troponin T levels. He had a medical history of coronary artery disease complicated by myocardial infarction (MI), as well as ischemic cardiomyopathy, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, ischemic stroke, and pulmonary embolism for which he was on long-term anticoagulation for years with warfarin, aspirin, and clopidogrel. The patient was diagnosed with a non–ST-segment elevation MI. Accordingly, the patient’s warfarin was discontinued, and he was administered a bolus and continuous infusion of UFH. He also was continued on aspirin and clopidogrel. Within 6 hours of initiation of UFH, the patient noted multiple discrete swollen lesions in the mouth. Dermatology consultation and biopsy of the lesions were deferred due to acute management of the patient’s MI.

Physical examination revealed a moist oral mucosa with 7 slightly raised, hemorrhagic bullae ranging from 2 to 7 mm in diameter (Figure, A and B). One oral lesion was tense and had become denuded prior to evaluation. Laboratory testing included a normal platelet count (160,000/µL), a nearly therapeutic international normalized ratio (1.9), and a partial thromboplastin time that was initially normal (27 seconds) prior to admission and development of the oral lesions but found to be elevated (176 seconds) after admission and initial UFH bolus.

Upon further questioning, the patient revealed a history of similar oral lesions 1 year prior, following exposure to subcutaneous enoxaparin. At that time, formal evaluation by dermatology was deferred due to the rapid resolution of the blisters. Despite these new oral lesions, the patient was continued on a heparin drip for the next 48 hours because of the mortality benefit of heparin in non–ST-segment elevation MI. The patient was discharged from the hospital on a regimen of aspirin, warfarin, and clopidogrel. At 2-week follow-up, the oral lesions had resolved (Figure, C and D).

Comment

Heparin-Induced Skin Lesions

The 2 most common types of heparin-induced skin lesions are delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions and immune-mediated HIT. A 2009 Canadian study found that the overwhelming majority of heparin-induced skin lesions are due to delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions.

Types of HIT

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia is one of the most serious adverse reactions to heparin administration. There are 2 subtypes of HIT, which differ in their clinical significance and pathophysiology.

Type II HIT is an immune-mediated response caused by the formation of IgG autoantibodies against the heparin–platelet factor 4 complex. Antibody formation and thrombocytopenia typically occur after 4 to 10 days of heparin exposure, and there can be devastating arterial and venous thrombotic complications.

Diagnosis of HIT

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia should be suspected in patients with a lowered platelet count, particularly if the decrease is more than 50% from baseline, and in patients who develop stroke, MI, pulmonary embolism, or deep vein thrombosis while on heparin. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia was not observed in our patient, as his platelet count remained stable between 160,000 and 164,000/µL throughout his hospital stay and he did not develop any evidence of thrombosis.

Differential Diagnosis

Our patient’s lesions appeared morphologically similar to

Bullous pemphigoid also was considered given the presence of tense bullae in an elderly patient. However, the rapid and spontaneous resolution of these lesions with complete lack of skin involvement made this diagnosis less likely.12

Heparin-Induced Bullous Hemorrhagic Dermatosis

Because our patient described a similar reaction while taking enoxaparin in the past, this case represents an idiosyncratic drug reaction, possibly from antibodies to a heparin-antigen complex. Heparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is a rarely reported condition with the majority of lesions presenting on the extremities.

Conclusion

We describe a rare side effect of heparin therapy characterized by discrete blisters on the oral mucosa. However, familiarity with the spectrum of reactions to heparin allowed the patient to continue heparin therapy despite this side effect, as the eruption was not life-threatening and the benefit of continuing heparin outweighed this adverse effect.

Heparin is a naturally occurring anticoagulant and is commonly used to treat or prevent venous thrombosis or the extension of thrombosis.

Adverse effects of heparin administration include bleeding, injection-site pain, and thrombocytopenia. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is a serious side effect wherein antibodies are formed against platelet antigens and predispose the patient to venous and arterial thrombosis.

Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is a poorly understood idiosyncratic drug reaction characterized by tense, blood-filled blisters that arise following the administration of subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin or intravenous unfractionated heparin (UFH). First reported in 2006 by Perrinaud et al

Case Report

An 84-year-old man was admitted to the cardiology service with severe substernal chest pain. An electrocardiogram did not show any ST-segment elevations; however, he had elevated troponin T levels. He had a medical history of coronary artery disease complicated by myocardial infarction (MI), as well as ischemic cardiomyopathy, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, ischemic stroke, and pulmonary embolism for which he was on long-term anticoagulation for years with warfarin, aspirin, and clopidogrel. The patient was diagnosed with a non–ST-segment elevation MI. Accordingly, the patient’s warfarin was discontinued, and he was administered a bolus and continuous infusion of UFH. He also was continued on aspirin and clopidogrel. Within 6 hours of initiation of UFH, the patient noted multiple discrete swollen lesions in the mouth. Dermatology consultation and biopsy of the lesions were deferred due to acute management of the patient’s MI.

Physical examination revealed a moist oral mucosa with 7 slightly raised, hemorrhagic bullae ranging from 2 to 7 mm in diameter (Figure, A and B). One oral lesion was tense and had become denuded prior to evaluation. Laboratory testing included a normal platelet count (160,000/µL), a nearly therapeutic international normalized ratio (1.9), and a partial thromboplastin time that was initially normal (27 seconds) prior to admission and development of the oral lesions but found to be elevated (176 seconds) after admission and initial UFH bolus.

Upon further questioning, the patient revealed a history of similar oral lesions 1 year prior, following exposure to subcutaneous enoxaparin. At that time, formal evaluation by dermatology was deferred due to the rapid resolution of the blisters. Despite these new oral lesions, the patient was continued on a heparin drip for the next 48 hours because of the mortality benefit of heparin in non–ST-segment elevation MI. The patient was discharged from the hospital on a regimen of aspirin, warfarin, and clopidogrel. At 2-week follow-up, the oral lesions had resolved (Figure, C and D).

Comment

Heparin-Induced Skin Lesions

The 2 most common types of heparin-induced skin lesions are delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions and immune-mediated HIT. A 2009 Canadian study found that the overwhelming majority of heparin-induced skin lesions are due to delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions.

Types of HIT

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia is one of the most serious adverse reactions to heparin administration. There are 2 subtypes of HIT, which differ in their clinical significance and pathophysiology.

Type II HIT is an immune-mediated response caused by the formation of IgG autoantibodies against the heparin–platelet factor 4 complex. Antibody formation and thrombocytopenia typically occur after 4 to 10 days of heparin exposure, and there can be devastating arterial and venous thrombotic complications.

Diagnosis of HIT

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia should be suspected in patients with a lowered platelet count, particularly if the decrease is more than 50% from baseline, and in patients who develop stroke, MI, pulmonary embolism, or deep vein thrombosis while on heparin. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia was not observed in our patient, as his platelet count remained stable between 160,000 and 164,000/µL throughout his hospital stay and he did not develop any evidence of thrombosis.

Differential Diagnosis

Our patient’s lesions appeared morphologically similar to

Bullous pemphigoid also was considered given the presence of tense bullae in an elderly patient. However, the rapid and spontaneous resolution of these lesions with complete lack of skin involvement made this diagnosis less likely.12

Heparin-Induced Bullous Hemorrhagic Dermatosis

Because our patient described a similar reaction while taking enoxaparin in the past, this case represents an idiosyncratic drug reaction, possibly from antibodies to a heparin-antigen complex. Heparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is a rarely reported condition with the majority of lesions presenting on the extremities.

Conclusion

We describe a rare side effect of heparin therapy characterized by discrete blisters on the oral mucosa. However, familiarity with the spectrum of reactions to heparin allowed the patient to continue heparin therapy despite this side effect, as the eruption was not life-threatening and the benefit of continuing heparin outweighed this adverse effect.

- Gómez-Outes A, Suárez-Gea ML, Calvo-Rojas G, et al. Discovery of anticoagulant drugs: a historical perspective. Curr Drug Discov Technol. 2012;9:83-104.

- Noti C, Seeberger PH. Chemical approaches to define the structure-activity relationship of heparin-like glycosaminoglycans. Chem Biol. 2005;12:731-756.

- Bakchoul T. An update on heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: diagnosis and management. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2016;15:787-797.

- Schindewolf M, Schwaner S, Wolter M, et al. Incidence and causes of heparin-induced skin lesions. Can Med Assoc J. 2009;181:477-481.

- Perrinaud A, Jacobi D, Machet MC, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis occurring at sites distant from subcutaneous injections of heparin: three cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(2 suppl):S5-S7.

- Naveen KN, Rai V. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis: a case report. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:423.

- Choudhry S, Fishman PM, Hernandez C. Heparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis. Cutis. 2013;91:93-98.

- Villanueva CA, Nájera L, Espinosa P, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis at distant sites: a report of 2 new cases due to enoxaparin injection and a review of the literature. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:816-819.

- Ahmed I, Majeed A, Powell R. Heparin induced thrombocytopenia: diagnosis and management update. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83:575-582.

- Horie N, Kawano R, Inaba J, et al. Angina bullosa hemorrhagica of the soft palate: a clinical study of 16 cases. J Oral Sci. 2008;50:33-36.

- Rai S, Kaur M, Goel S. Angina bullosa hemorrhagica: report of 2 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:503.

- Lawson W. Bullous oral lesions: clues to identifying—and managing—the cause. Consultant. 2013;53:168-176.

- Gómez-Outes A, Suárez-Gea ML, Calvo-Rojas G, et al. Discovery of anticoagulant drugs: a historical perspective. Curr Drug Discov Technol. 2012;9:83-104.

- Noti C, Seeberger PH. Chemical approaches to define the structure-activity relationship of heparin-like glycosaminoglycans. Chem Biol. 2005;12:731-756.

- Bakchoul T. An update on heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: diagnosis and management. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2016;15:787-797.

- Schindewolf M, Schwaner S, Wolter M, et al. Incidence and causes of heparin-induced skin lesions. Can Med Assoc J. 2009;181:477-481.

- Perrinaud A, Jacobi D, Machet MC, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis occurring at sites distant from subcutaneous injections of heparin: three cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(2 suppl):S5-S7.

- Naveen KN, Rai V. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis: a case report. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:423.

- Choudhry S, Fishman PM, Hernandez C. Heparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis. Cutis. 2013;91:93-98.

- Villanueva CA, Nájera L, Espinosa P, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis at distant sites: a report of 2 new cases due to enoxaparin injection and a review of the literature. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:816-819.

- Ahmed I, Majeed A, Powell R. Heparin induced thrombocytopenia: diagnosis and management update. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83:575-582.

- Horie N, Kawano R, Inaba J, et al. Angina bullosa hemorrhagica of the soft palate: a clinical study of 16 cases. J Oral Sci. 2008;50:33-36.

- Rai S, Kaur M, Goel S. Angina bullosa hemorrhagica: report of 2 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:503.

- Lawson W. Bullous oral lesions: clues to identifying—and managing—the cause. Consultant. 2013;53:168-176.

Practice Points

- It is important for physicians to recognize the clinical appearance of cutaneous adverse reactions to heparin, including bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis.

- Heparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis tends to self-resolve, even with continuation of unfractionated heparin.