User login

Enlarging Pigmented Lesion on the Thigh

The Diagnosis: Localized Cutaneous Argyria

The differential diagnosis of an enlarging pigmented lesion is broad, including various neoplasms, pigmented deep fungal infections, and cutaneous deposits secondary to systemic or topical medications or other exogenous substances. In our patient, identification of black particulate material on biopsy prompted further questioning. After the sinus tract persisted for 6 months, our patient’s infectious disease physician started applying silver nitrate at 3-week intervals to minimize drainage, exudate, and granulation tissue formation. After 3 months, marked pigmentation of the skin around the sinus tract was noted.

Argyria is a rare skin disorder that results from deposition of silver via localized exposure or systemic ingestion. Discoloration can either be reversible or irreversible, usually dependent on the length of silver exposure.1 Affected individuals exhibit blue-gray pigmentation of the skin that may be localized or diffuse. Photoactivated reduction of silver salts leads to conversion to elemental silver in the skin.2 Although argyria is most common on sun-exposed areas, the mucosae and nails may be involved in systemic cases. The etiology of argyria includes occupational exposure by ingestion of dust or traumatic cutaneous exposure in jewelry manufacturing, mining, or photographic or radiograph manufacturing. Other sources of localized argyria include prolonged contact with topical silver nitrate or silver sulfadiazine for wound care, silver-coated jewelry or piercings, acupuncture, tooth restoration procedures using dental amalgam, silver-containing surgical implants, or other silver-containing medications or wound dressings. Discontinuing contact with the source of silver minimizes further pigmentation, and excision of deposits may be helpful in some instances.3

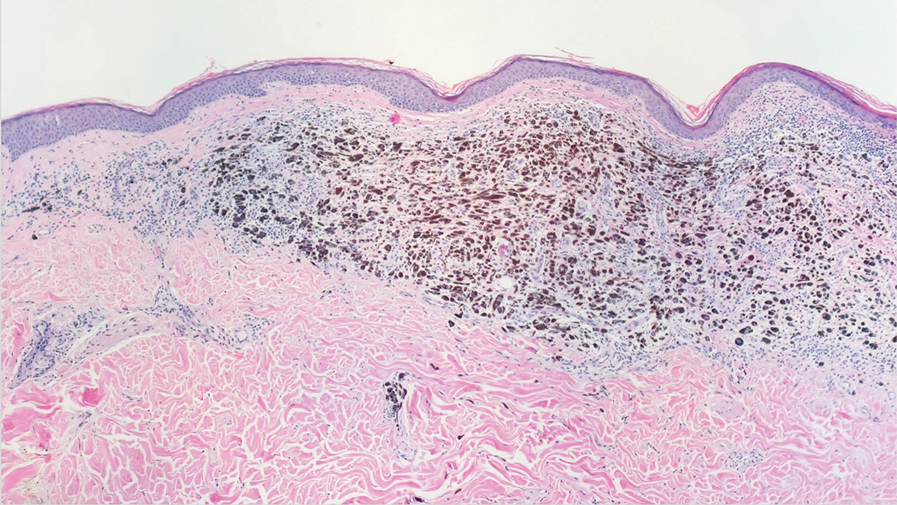

Histopathologic findings in argyria may be subtle and diverse. Small particulate material may be apparent on careful examination at high magnification only, and the depth of deposition can depend on the etiology of absorption or implantation as well as the length of exposure. Short-term exposure may be associated with deposition of dark, brown-black, coarse granules confined to the stratum corneum.1 Frequently, cases of argyria reveal small, extracellular, brown-black, pigmented granules in a bandlike distribution primarily around vasculature, eccrine glands, perineural tissue, hair follicles, or arrector pili muscles or free in the dermis around collagen bundles. The granules can be highlighted by dark-field microscopy that will display scattered, refractile, white particles, described as a “stars in heaven” pattern.3 Rare ochre-colored collagen bundles have been reported in some cases, described as a pseudo-ochronosis pattern of argyria.4

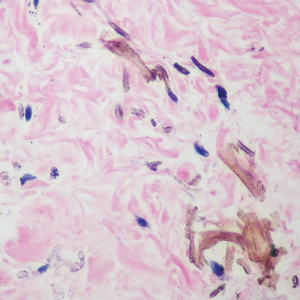

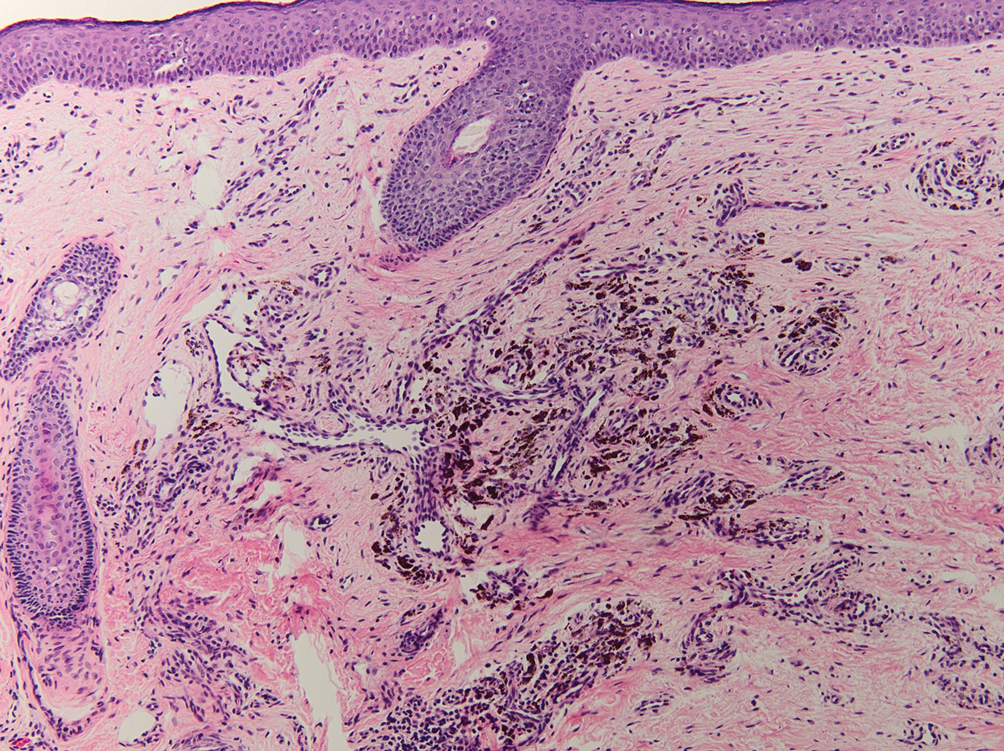

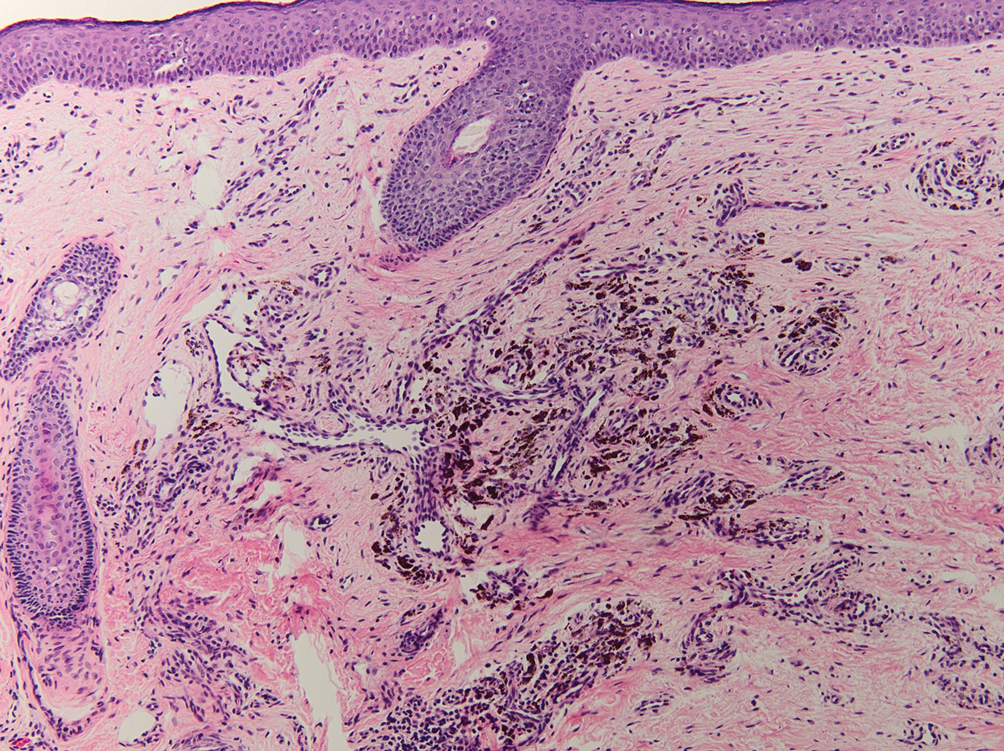

Given the clinical history in our patient, a melanocytic lesion was considered but was excluded based on the histopathologic findings. Regressed melanoma clinically may resemble cutaneous silver deposition, as tumoral melanosis can be associated with an intense blue-black presentation. Histopathology will reveal an absence of melanocytes with residual coarse melanin in melanophages (Figure 1) rather than the particulate material associated with silver deposition. Although argyria can be associated with increased melanin in the basal epidermal keratinocytes and melanophages in the papillary dermis, silver granules can be distinguished by their uniform appearance and location throughout the skin (dermis, around vasculature/adnexal structures vs melanin in melanophages and basal epidermal keratinocytes).3,5,6

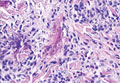

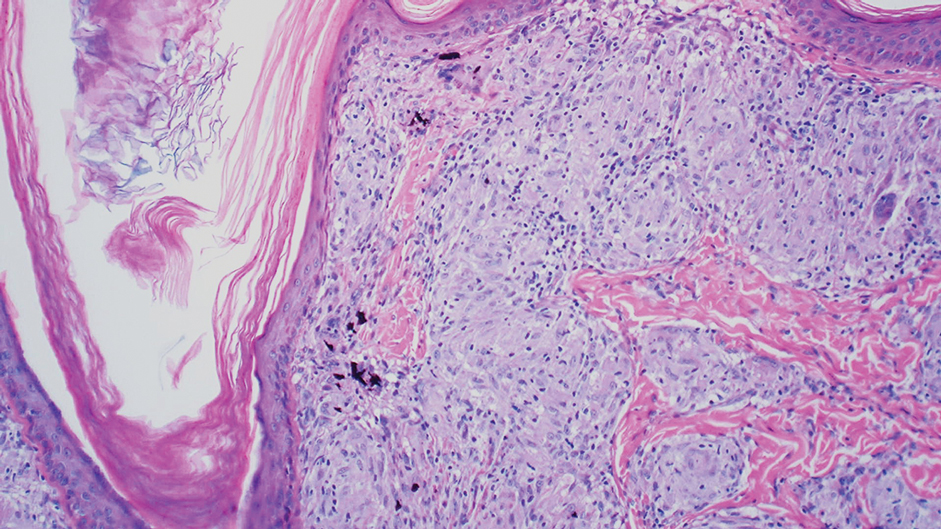

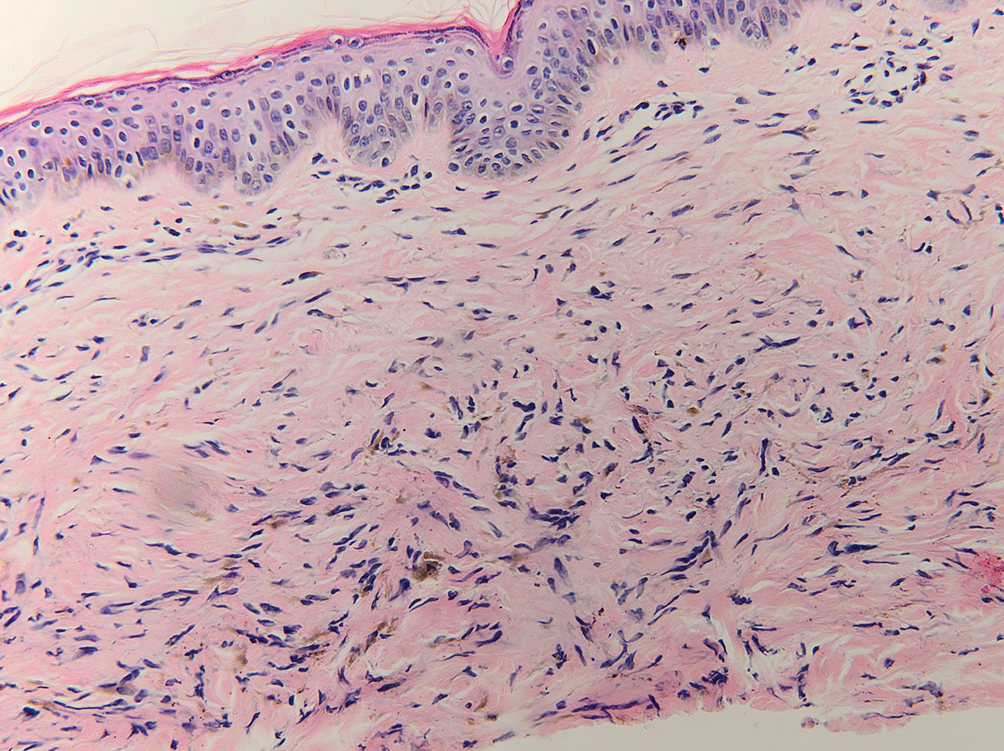

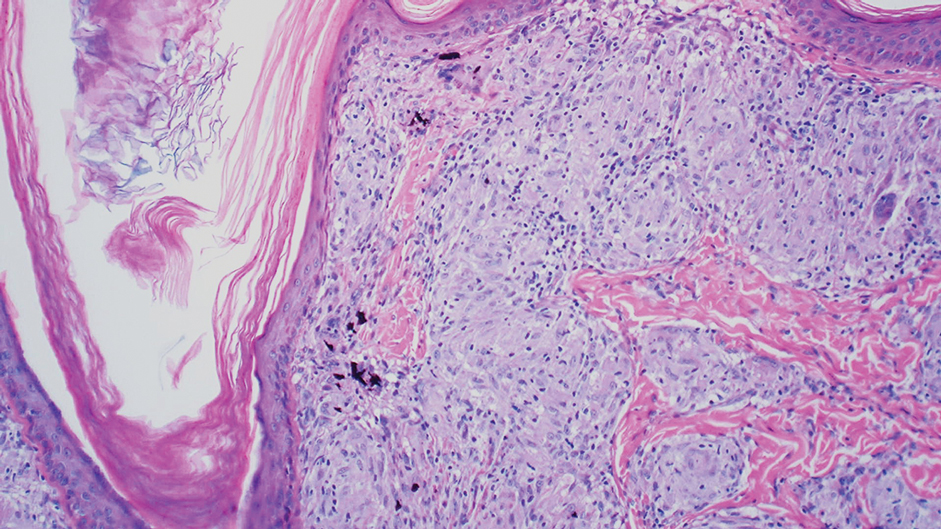

Blue nevi typically present as well-circumscribed, blue to gray or even dark brown lesions most often located on the arms, legs, head, and neck. Histopathology reveals spindle-shaped dendritic melanocytes dissecting through collagen bundles in the dermis with melanophages (Figure 2). Pigmentation may vary from extensive to little or even none. Blue nevi are demarcated and may be associated with dermal sclerosis.7

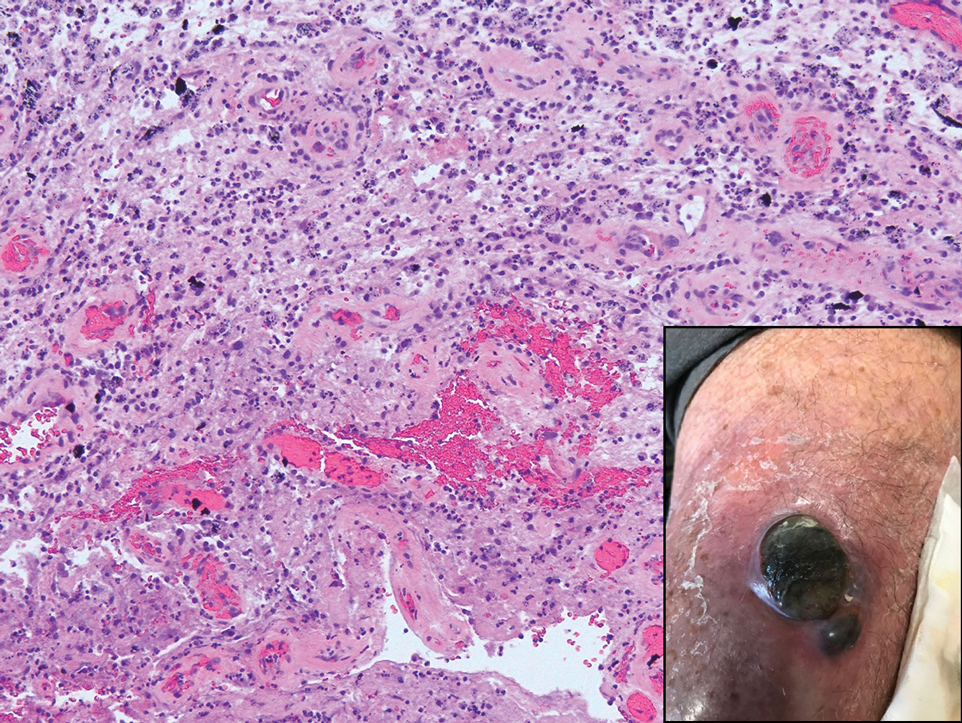

Drug-induced hyperpigmentation has a variable presentation both clinically and histologically depending on the type of drug implicated. Tetracyclines, particularly minocycline, are known culprits of drug-induced pigmentation, which can present as blue-gray to brown discoloration in at least 3 classically described patterns: (1) blue-black pigmentation around scars or prior inflammatory sites, (2) blue-black pigmentation on the shins or upper extremities, or (3) brown pigmentation in photosensitive areas. Histopathology reveals brown-black granules intracellularly in macrophages or fibroblasts or localized around vessels or eccrine glands (Figure 3). Special stains such as Perls Prussian blue or Fontana-Masson may highlight the pigmented granules. Widespread pigmentation in other organs, such as the thyroid, and history of long-standing tetracycline use are helpful clues to distinguish drug-induced pigmentation from other entities.8

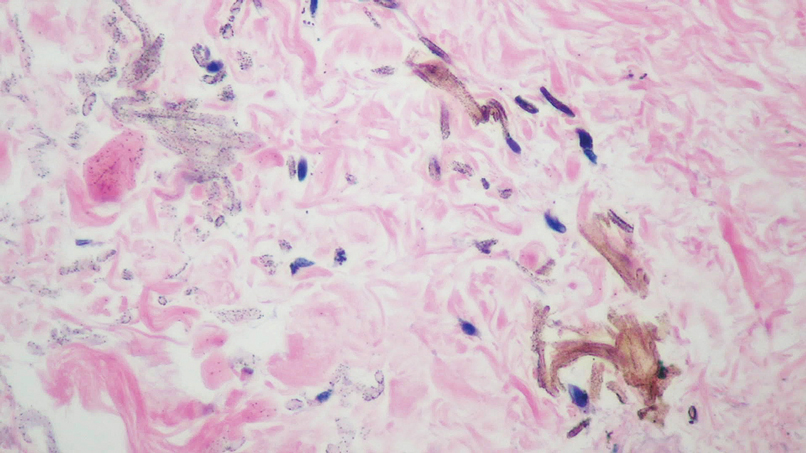

Tattoo ink reaction frequently presents as an irregular pigmented lesion that can have associated features of inflammation including rash, erythema, and swelling. Histopathology reveals small clumped pigment in the dermis localized either extracellularly preferentially around vascular structures and collagen fibers or intracellularly in macrophages or fibroblasts (Figure 4). Considering the pigment is foreign material, a mixed inflammatory infiltrate can be present or more rarely the presence of pigment may induce pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. The inflammatory reaction pattern on histology can vary, but granulomatous and lichenoid patterns frequently have been described. Other helpful clues to suggest tattoo pigment include refractile granules under polarized light and multiple pigmented colors.3

Dermal melanocytosis also may be considered, which consists of blue-gray irregular macules to patches on the skin that are frequently present at birth but may develop later in life. Histopathology reveals pigmented dendritic to spindle-shaped dermal melanocytes and melanophages dissecting between collagen fibers localized to the deep dermis. In addition, some hematologic or vascular disorders, including resolving hemorrhage or cyanosis, may be considered in the clinical differential. Deposition disorders such as chrysiasis and ochronosis could exhibit clinical or histopathologic similarities.3,8

Occasionally, prolonged use of topical silver nitrate may result in a pigmented lesion that mimics a melanocytic neoplasm or other pigmented lesions. However, these conditions can be readily differentiated by their characteristic histopathologic findings along with detailed clinical history.

- Ondrasik RM, Jordan P, Sriharan A. A clinical mimicker of melanoma with distinctive histopathology: topical silver nitrate exposure. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:1205-1210.

- Gill P, Richards K, Cho WC, et al. Localized cutaneous argyria: review of a rare clinical mimicker of melanocytic lesions. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2021;54:151776.

- Molina-Ruiz AM, Cerroni L, Kutzner H, et al. Cutaneous deposits. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:1-48.

- Lee J, Korgavkar K, DiMarco C, et al. Localized argyria with pseudoochronosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:671-674.

- El Sharouni MA, Aivazian K, Witkamp AJ, et al. Association of histologic regression with a favorable outcome in patients with stage 1 and stage 2 cutaneous melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:166-173.

- Staser K, Chen D, Solus J, et al. Extensive tumoral melanosis associated with ipilimumab-treated melanoma. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:391-393.

- Sugianto JZ, Ralston JS, Metcalf JS, et al. Blue nevus and “malignant blue nevus”: a concise review. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2016;33:219-224.

- Wang RF, Ko D, Friedman BJ, et al. Disorders of hyperpigmentation. part I. pathogenesis and clinical features of common pigmentary disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:271-288.

The Diagnosis: Localized Cutaneous Argyria

The differential diagnosis of an enlarging pigmented lesion is broad, including various neoplasms, pigmented deep fungal infections, and cutaneous deposits secondary to systemic or topical medications or other exogenous substances. In our patient, identification of black particulate material on biopsy prompted further questioning. After the sinus tract persisted for 6 months, our patient’s infectious disease physician started applying silver nitrate at 3-week intervals to minimize drainage, exudate, and granulation tissue formation. After 3 months, marked pigmentation of the skin around the sinus tract was noted.

Argyria is a rare skin disorder that results from deposition of silver via localized exposure or systemic ingestion. Discoloration can either be reversible or irreversible, usually dependent on the length of silver exposure.1 Affected individuals exhibit blue-gray pigmentation of the skin that may be localized or diffuse. Photoactivated reduction of silver salts leads to conversion to elemental silver in the skin.2 Although argyria is most common on sun-exposed areas, the mucosae and nails may be involved in systemic cases. The etiology of argyria includes occupational exposure by ingestion of dust or traumatic cutaneous exposure in jewelry manufacturing, mining, or photographic or radiograph manufacturing. Other sources of localized argyria include prolonged contact with topical silver nitrate or silver sulfadiazine for wound care, silver-coated jewelry or piercings, acupuncture, tooth restoration procedures using dental amalgam, silver-containing surgical implants, or other silver-containing medications or wound dressings. Discontinuing contact with the source of silver minimizes further pigmentation, and excision of deposits may be helpful in some instances.3

Histopathologic findings in argyria may be subtle and diverse. Small particulate material may be apparent on careful examination at high magnification only, and the depth of deposition can depend on the etiology of absorption or implantation as well as the length of exposure. Short-term exposure may be associated with deposition of dark, brown-black, coarse granules confined to the stratum corneum.1 Frequently, cases of argyria reveal small, extracellular, brown-black, pigmented granules in a bandlike distribution primarily around vasculature, eccrine glands, perineural tissue, hair follicles, or arrector pili muscles or free in the dermis around collagen bundles. The granules can be highlighted by dark-field microscopy that will display scattered, refractile, white particles, described as a “stars in heaven” pattern.3 Rare ochre-colored collagen bundles have been reported in some cases, described as a pseudo-ochronosis pattern of argyria.4

Given the clinical history in our patient, a melanocytic lesion was considered but was excluded based on the histopathologic findings. Regressed melanoma clinically may resemble cutaneous silver deposition, as tumoral melanosis can be associated with an intense blue-black presentation. Histopathology will reveal an absence of melanocytes with residual coarse melanin in melanophages (Figure 1) rather than the particulate material associated with silver deposition. Although argyria can be associated with increased melanin in the basal epidermal keratinocytes and melanophages in the papillary dermis, silver granules can be distinguished by their uniform appearance and location throughout the skin (dermis, around vasculature/adnexal structures vs melanin in melanophages and basal epidermal keratinocytes).3,5,6

Blue nevi typically present as well-circumscribed, blue to gray or even dark brown lesions most often located on the arms, legs, head, and neck. Histopathology reveals spindle-shaped dendritic melanocytes dissecting through collagen bundles in the dermis with melanophages (Figure 2). Pigmentation may vary from extensive to little or even none. Blue nevi are demarcated and may be associated with dermal sclerosis.7

Drug-induced hyperpigmentation has a variable presentation both clinically and histologically depending on the type of drug implicated. Tetracyclines, particularly minocycline, are known culprits of drug-induced pigmentation, which can present as blue-gray to brown discoloration in at least 3 classically described patterns: (1) blue-black pigmentation around scars or prior inflammatory sites, (2) blue-black pigmentation on the shins or upper extremities, or (3) brown pigmentation in photosensitive areas. Histopathology reveals brown-black granules intracellularly in macrophages or fibroblasts or localized around vessels or eccrine glands (Figure 3). Special stains such as Perls Prussian blue or Fontana-Masson may highlight the pigmented granules. Widespread pigmentation in other organs, such as the thyroid, and history of long-standing tetracycline use are helpful clues to distinguish drug-induced pigmentation from other entities.8

Tattoo ink reaction frequently presents as an irregular pigmented lesion that can have associated features of inflammation including rash, erythema, and swelling. Histopathology reveals small clumped pigment in the dermis localized either extracellularly preferentially around vascular structures and collagen fibers or intracellularly in macrophages or fibroblasts (Figure 4). Considering the pigment is foreign material, a mixed inflammatory infiltrate can be present or more rarely the presence of pigment may induce pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. The inflammatory reaction pattern on histology can vary, but granulomatous and lichenoid patterns frequently have been described. Other helpful clues to suggest tattoo pigment include refractile granules under polarized light and multiple pigmented colors.3

Dermal melanocytosis also may be considered, which consists of blue-gray irregular macules to patches on the skin that are frequently present at birth but may develop later in life. Histopathology reveals pigmented dendritic to spindle-shaped dermal melanocytes and melanophages dissecting between collagen fibers localized to the deep dermis. In addition, some hematologic or vascular disorders, including resolving hemorrhage or cyanosis, may be considered in the clinical differential. Deposition disorders such as chrysiasis and ochronosis could exhibit clinical or histopathologic similarities.3,8

Occasionally, prolonged use of topical silver nitrate may result in a pigmented lesion that mimics a melanocytic neoplasm or other pigmented lesions. However, these conditions can be readily differentiated by their characteristic histopathologic findings along with detailed clinical history.

The Diagnosis: Localized Cutaneous Argyria

The differential diagnosis of an enlarging pigmented lesion is broad, including various neoplasms, pigmented deep fungal infections, and cutaneous deposits secondary to systemic or topical medications or other exogenous substances. In our patient, identification of black particulate material on biopsy prompted further questioning. After the sinus tract persisted for 6 months, our patient’s infectious disease physician started applying silver nitrate at 3-week intervals to minimize drainage, exudate, and granulation tissue formation. After 3 months, marked pigmentation of the skin around the sinus tract was noted.

Argyria is a rare skin disorder that results from deposition of silver via localized exposure or systemic ingestion. Discoloration can either be reversible or irreversible, usually dependent on the length of silver exposure.1 Affected individuals exhibit blue-gray pigmentation of the skin that may be localized or diffuse. Photoactivated reduction of silver salts leads to conversion to elemental silver in the skin.2 Although argyria is most common on sun-exposed areas, the mucosae and nails may be involved in systemic cases. The etiology of argyria includes occupational exposure by ingestion of dust or traumatic cutaneous exposure in jewelry manufacturing, mining, or photographic or radiograph manufacturing. Other sources of localized argyria include prolonged contact with topical silver nitrate or silver sulfadiazine for wound care, silver-coated jewelry or piercings, acupuncture, tooth restoration procedures using dental amalgam, silver-containing surgical implants, or other silver-containing medications or wound dressings. Discontinuing contact with the source of silver minimizes further pigmentation, and excision of deposits may be helpful in some instances.3

Histopathologic findings in argyria may be subtle and diverse. Small particulate material may be apparent on careful examination at high magnification only, and the depth of deposition can depend on the etiology of absorption or implantation as well as the length of exposure. Short-term exposure may be associated with deposition of dark, brown-black, coarse granules confined to the stratum corneum.1 Frequently, cases of argyria reveal small, extracellular, brown-black, pigmented granules in a bandlike distribution primarily around vasculature, eccrine glands, perineural tissue, hair follicles, or arrector pili muscles or free in the dermis around collagen bundles. The granules can be highlighted by dark-field microscopy that will display scattered, refractile, white particles, described as a “stars in heaven” pattern.3 Rare ochre-colored collagen bundles have been reported in some cases, described as a pseudo-ochronosis pattern of argyria.4

Given the clinical history in our patient, a melanocytic lesion was considered but was excluded based on the histopathologic findings. Regressed melanoma clinically may resemble cutaneous silver deposition, as tumoral melanosis can be associated with an intense blue-black presentation. Histopathology will reveal an absence of melanocytes with residual coarse melanin in melanophages (Figure 1) rather than the particulate material associated with silver deposition. Although argyria can be associated with increased melanin in the basal epidermal keratinocytes and melanophages in the papillary dermis, silver granules can be distinguished by their uniform appearance and location throughout the skin (dermis, around vasculature/adnexal structures vs melanin in melanophages and basal epidermal keratinocytes).3,5,6

Blue nevi typically present as well-circumscribed, blue to gray or even dark brown lesions most often located on the arms, legs, head, and neck. Histopathology reveals spindle-shaped dendritic melanocytes dissecting through collagen bundles in the dermis with melanophages (Figure 2). Pigmentation may vary from extensive to little or even none. Blue nevi are demarcated and may be associated with dermal sclerosis.7

Drug-induced hyperpigmentation has a variable presentation both clinically and histologically depending on the type of drug implicated. Tetracyclines, particularly minocycline, are known culprits of drug-induced pigmentation, which can present as blue-gray to brown discoloration in at least 3 classically described patterns: (1) blue-black pigmentation around scars or prior inflammatory sites, (2) blue-black pigmentation on the shins or upper extremities, or (3) brown pigmentation in photosensitive areas. Histopathology reveals brown-black granules intracellularly in macrophages or fibroblasts or localized around vessels or eccrine glands (Figure 3). Special stains such as Perls Prussian blue or Fontana-Masson may highlight the pigmented granules. Widespread pigmentation in other organs, such as the thyroid, and history of long-standing tetracycline use are helpful clues to distinguish drug-induced pigmentation from other entities.8

Tattoo ink reaction frequently presents as an irregular pigmented lesion that can have associated features of inflammation including rash, erythema, and swelling. Histopathology reveals small clumped pigment in the dermis localized either extracellularly preferentially around vascular structures and collagen fibers or intracellularly in macrophages or fibroblasts (Figure 4). Considering the pigment is foreign material, a mixed inflammatory infiltrate can be present or more rarely the presence of pigment may induce pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. The inflammatory reaction pattern on histology can vary, but granulomatous and lichenoid patterns frequently have been described. Other helpful clues to suggest tattoo pigment include refractile granules under polarized light and multiple pigmented colors.3

Dermal melanocytosis also may be considered, which consists of blue-gray irregular macules to patches on the skin that are frequently present at birth but may develop later in life. Histopathology reveals pigmented dendritic to spindle-shaped dermal melanocytes and melanophages dissecting between collagen fibers localized to the deep dermis. In addition, some hematologic or vascular disorders, including resolving hemorrhage or cyanosis, may be considered in the clinical differential. Deposition disorders such as chrysiasis and ochronosis could exhibit clinical or histopathologic similarities.3,8

Occasionally, prolonged use of topical silver nitrate may result in a pigmented lesion that mimics a melanocytic neoplasm or other pigmented lesions. However, these conditions can be readily differentiated by their characteristic histopathologic findings along with detailed clinical history.

- Ondrasik RM, Jordan P, Sriharan A. A clinical mimicker of melanoma with distinctive histopathology: topical silver nitrate exposure. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:1205-1210.

- Gill P, Richards K, Cho WC, et al. Localized cutaneous argyria: review of a rare clinical mimicker of melanocytic lesions. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2021;54:151776.

- Molina-Ruiz AM, Cerroni L, Kutzner H, et al. Cutaneous deposits. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:1-48.

- Lee J, Korgavkar K, DiMarco C, et al. Localized argyria with pseudoochronosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:671-674.

- El Sharouni MA, Aivazian K, Witkamp AJ, et al. Association of histologic regression with a favorable outcome in patients with stage 1 and stage 2 cutaneous melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:166-173.

- Staser K, Chen D, Solus J, et al. Extensive tumoral melanosis associated with ipilimumab-treated melanoma. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:391-393.

- Sugianto JZ, Ralston JS, Metcalf JS, et al. Blue nevus and “malignant blue nevus”: a concise review. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2016;33:219-224.

- Wang RF, Ko D, Friedman BJ, et al. Disorders of hyperpigmentation. part I. pathogenesis and clinical features of common pigmentary disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:271-288.

- Ondrasik RM, Jordan P, Sriharan A. A clinical mimicker of melanoma with distinctive histopathology: topical silver nitrate exposure. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:1205-1210.

- Gill P, Richards K, Cho WC, et al. Localized cutaneous argyria: review of a rare clinical mimicker of melanocytic lesions. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2021;54:151776.

- Molina-Ruiz AM, Cerroni L, Kutzner H, et al. Cutaneous deposits. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:1-48.

- Lee J, Korgavkar K, DiMarco C, et al. Localized argyria with pseudoochronosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:671-674.

- El Sharouni MA, Aivazian K, Witkamp AJ, et al. Association of histologic regression with a favorable outcome in patients with stage 1 and stage 2 cutaneous melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:166-173.

- Staser K, Chen D, Solus J, et al. Extensive tumoral melanosis associated with ipilimumab-treated melanoma. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:391-393.

- Sugianto JZ, Ralston JS, Metcalf JS, et al. Blue nevus and “malignant blue nevus”: a concise review. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2016;33:219-224.

- Wang RF, Ko D, Friedman BJ, et al. Disorders of hyperpigmentation. part I. pathogenesis and clinical features of common pigmentary disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:271-288.

An 80-year-old man presented with a pigmented lesion on the left lateral thigh near the knee that had been gradually enlarging over several weeks (top [inset]). He underwent a left knee replacement surgery for advanced osteoarthritis many months prior that was complicated by postoperative Staphylococcus aureus infection with sinus tract formation that was persistent for 6 months and treated with a topical medication. A pigmented lesion developed near the opening of the sinus tract. His medical history was remarkable for extensive actinic damage as well as multiple actinic keratoses treated with cryotherapy but no history of melanoma. An excisional biopsy was performed (top and bottom).

Rapidly Enlarging Noduloulcerative Lesions

The Diagnosis: Lues Maligna

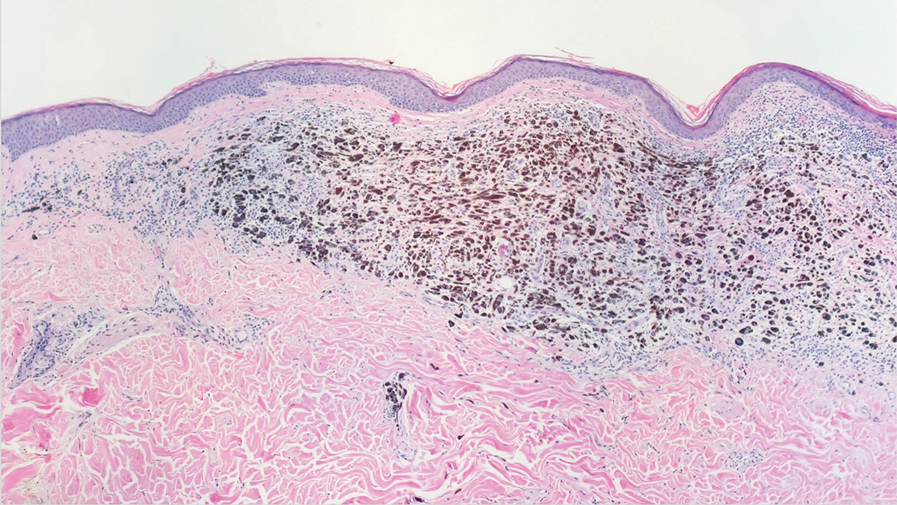

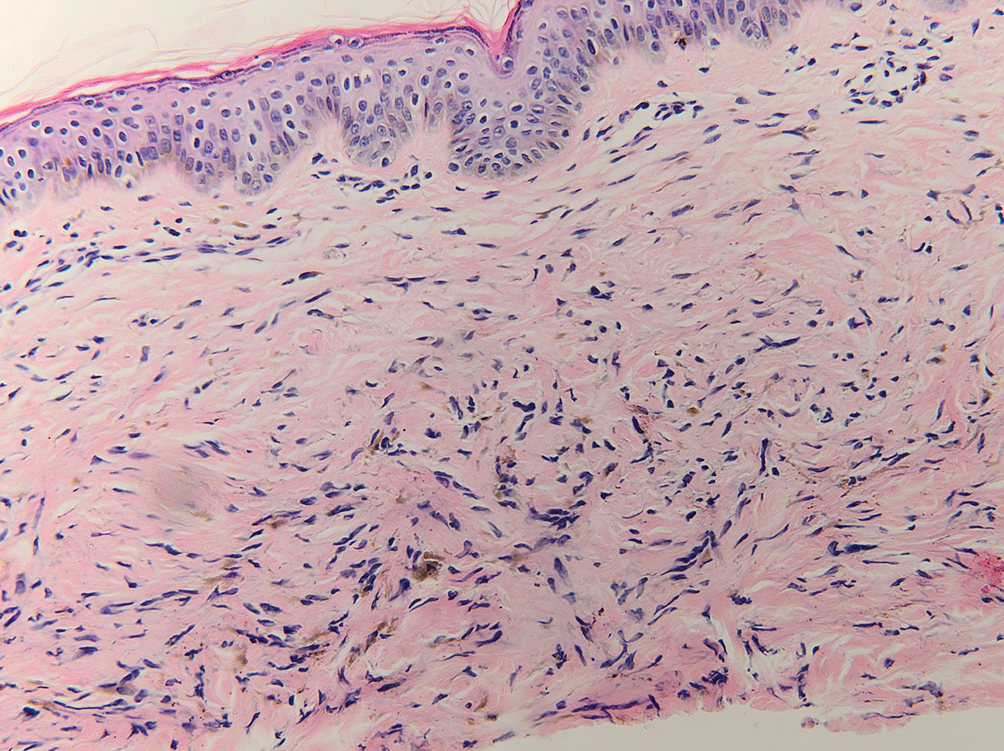

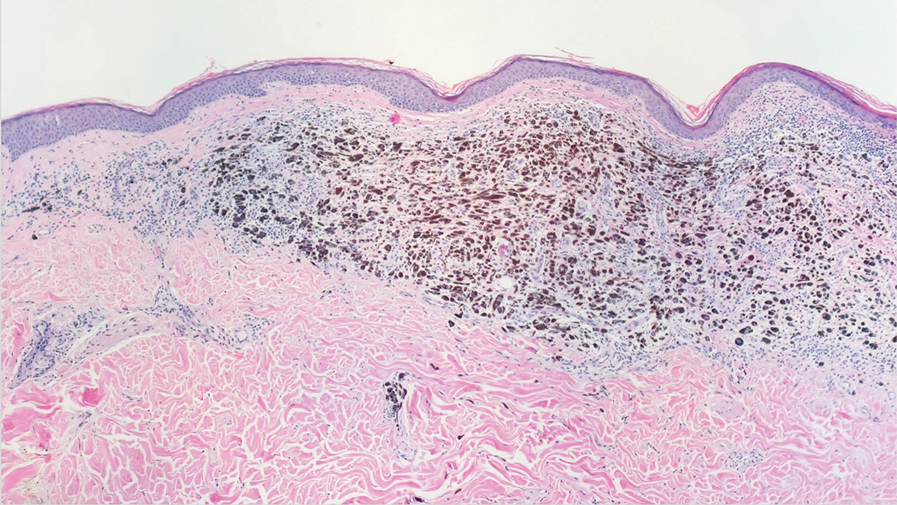

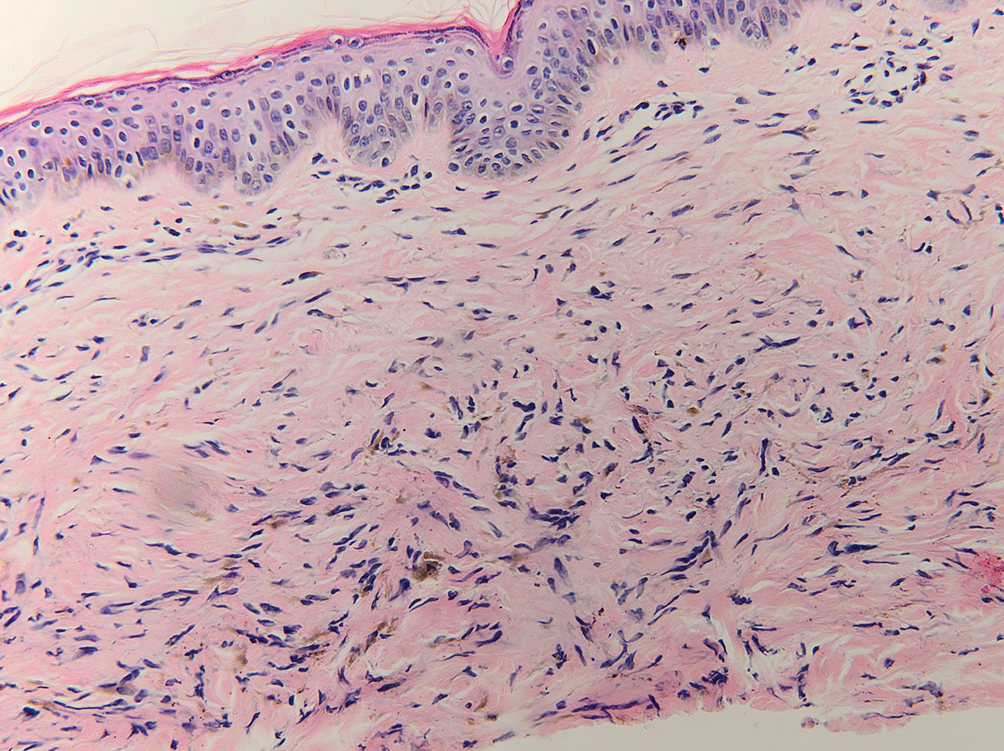

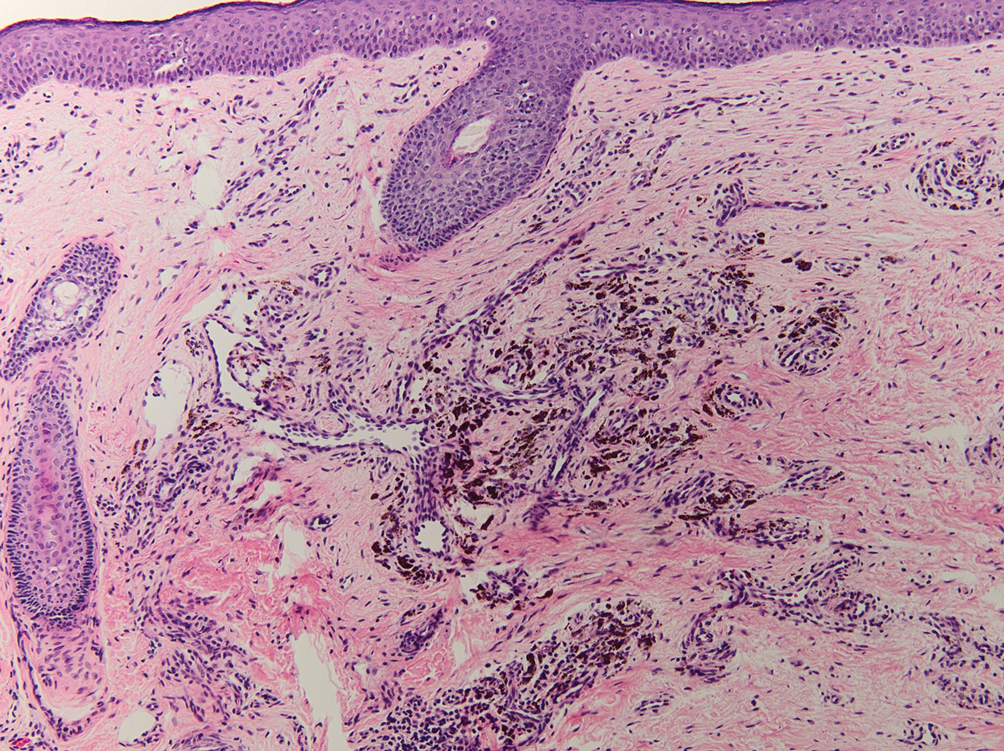

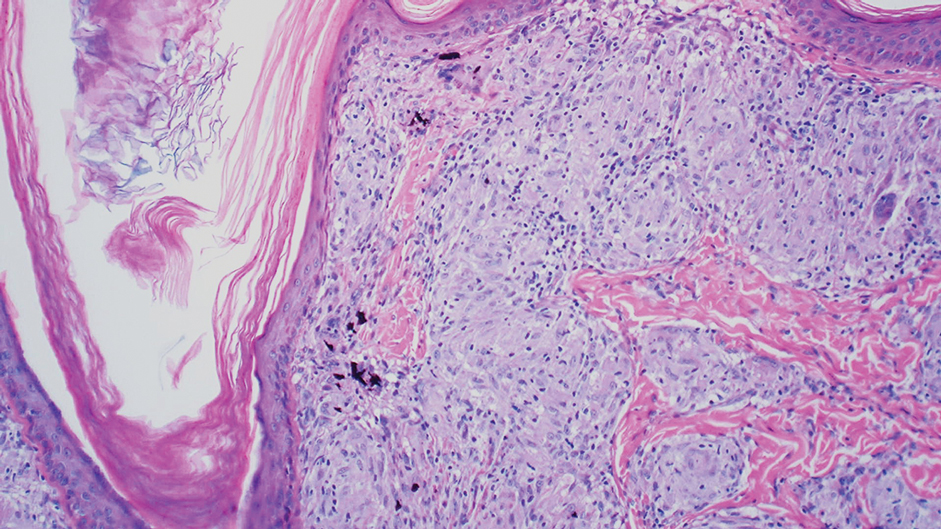

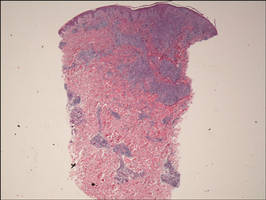

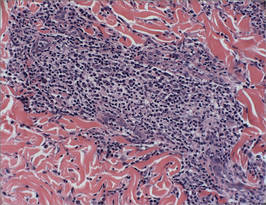

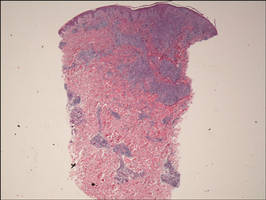

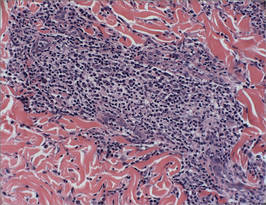

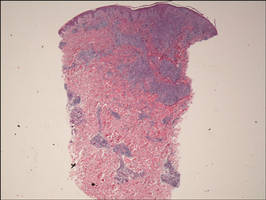

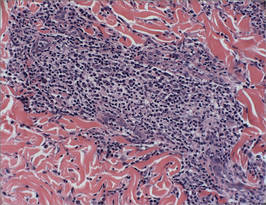

Biopsy revealed dense nodular aggregates of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and abundant plasma cells in both the superficial and deep dermis (Figure 1). There were perivascular and periadnexal aggregates of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and numerous plasma cells (Figure 2). Special stains for organisms, including Warthin-Starry silver, Giemsa, acid-fast bacilli, Gomori methenamine-silver, and Brown-Brenn stains were negative. Immunoperoxidase stain for Treponema pallidum also was negative. The patient’s rapid plasma reagin titer at the time of the fourth biopsy was 1:256, and appropriate treatment with penicillin resulted in complete clearance of the lesions in 3 to 4 weeks.

|

| Figure 1. Superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphohistiocytic infiltrate (H&E, original magnification ×2). |

|

| Figure 2. Perivascular and periadnexal aggregates of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and numerous plasma cells (H&E, original magnification ×20). |

Syphilis is caused by T pallidum. Three stages typically are identified in immunocompetent hosts: primary, secondary, and tertiary syphilis. Immunocompromised patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection may have unusual presentations.

Lues maligna is used to describe a rare noduloulcerative form of secondary syphilis.1 It was first described in 18592 and has been associated with other disorders such as diabetes mellitus3 and chronic alcoholism.4 Patients usually are gravely ill and develop polymorphic ulcerating lesions. Facial and scalp involvement are common, but patients typically do not have palmoplantar involvement in conventional presentations of secondary syphilis.

A scanning view of a punch biopsy from our patient revealed irregular acanthosis of the epidermis with long and thin rete pegs, a bandlike infiltrate at the dermoepidermal junction, and a dense superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal infiltrate. The histologic differential diagnosis includes pyoderma gangrenosum, vasculitis, lymphoma, leishmaniasis, leprosy, yaws, and mycobacterial or fungal infections.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends screening of all HIV-positive indivi-duals for syphilis, and all sexually active individuals with syphilis should be screened for HIV.5 If clinical examination and findings suggest syphilis in the presence of negative serologic testing, then direct fluorescence assay for T pallidum staining of lesions, exudates or biopsy, or dark-field microscopic examination should be performed. In our case, dark-field microscopy was not performed and serologic tests were negative at presentation. Silver stains can detect T pallidum in tissue specimens, though detection may not be possible late in the course of disease.6

The morphology and rapid response to treatment confirmed the diagnosis in our patient. The incidence of syphilis in HIV-positive patients has risen substantially in the last 2 decades. This case illustrates an uncommon presentation that is increasing in prevalence.

1. Fisher DA, Chang LW, Tuffanelli DL. Lues maligna: presentation of a case and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 1969;99:70-73.

2. Passoni LF, de Menezes JA, Ribeiro SR, et al. Lues maligna in an HIV-infected patient [published online ahead of print March 30, 2005]. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2005;38:181-184.

3. Hofmann UB, Hund M, Bröcker EB, et al. Lues maligna in a female patient with diabetes [in German]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3:780-782.

4. Bayramgürler D, Bilen N, Yildiz K, et al. Lues maligna in a chronic alcoholic patient. J Dermatol. 2005;32:217-219.

5. Centers for Disease Control. Recommendations for diagnosing and treating syphilis in HIV-infected patients. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1988;37:600-602.

6. Mannara GM. Bilateral secondary syphilis of the tonsil. J Laryngol Otol. 1999;113:1125-1127.

The Diagnosis: Lues Maligna

Biopsy revealed dense nodular aggregates of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and abundant plasma cells in both the superficial and deep dermis (Figure 1). There were perivascular and periadnexal aggregates of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and numerous plasma cells (Figure 2). Special stains for organisms, including Warthin-Starry silver, Giemsa, acid-fast bacilli, Gomori methenamine-silver, and Brown-Brenn stains were negative. Immunoperoxidase stain for Treponema pallidum also was negative. The patient’s rapid plasma reagin titer at the time of the fourth biopsy was 1:256, and appropriate treatment with penicillin resulted in complete clearance of the lesions in 3 to 4 weeks.

|

| Figure 1. Superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphohistiocytic infiltrate (H&E, original magnification ×2). |

|

| Figure 2. Perivascular and periadnexal aggregates of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and numerous plasma cells (H&E, original magnification ×20). |

Syphilis is caused by T pallidum. Three stages typically are identified in immunocompetent hosts: primary, secondary, and tertiary syphilis. Immunocompromised patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection may have unusual presentations.

Lues maligna is used to describe a rare noduloulcerative form of secondary syphilis.1 It was first described in 18592 and has been associated with other disorders such as diabetes mellitus3 and chronic alcoholism.4 Patients usually are gravely ill and develop polymorphic ulcerating lesions. Facial and scalp involvement are common, but patients typically do not have palmoplantar involvement in conventional presentations of secondary syphilis.

A scanning view of a punch biopsy from our patient revealed irregular acanthosis of the epidermis with long and thin rete pegs, a bandlike infiltrate at the dermoepidermal junction, and a dense superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal infiltrate. The histologic differential diagnosis includes pyoderma gangrenosum, vasculitis, lymphoma, leishmaniasis, leprosy, yaws, and mycobacterial or fungal infections.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends screening of all HIV-positive indivi-duals for syphilis, and all sexually active individuals with syphilis should be screened for HIV.5 If clinical examination and findings suggest syphilis in the presence of negative serologic testing, then direct fluorescence assay for T pallidum staining of lesions, exudates or biopsy, or dark-field microscopic examination should be performed. In our case, dark-field microscopy was not performed and serologic tests were negative at presentation. Silver stains can detect T pallidum in tissue specimens, though detection may not be possible late in the course of disease.6

The morphology and rapid response to treatment confirmed the diagnosis in our patient. The incidence of syphilis in HIV-positive patients has risen substantially in the last 2 decades. This case illustrates an uncommon presentation that is increasing in prevalence.

The Diagnosis: Lues Maligna

Biopsy revealed dense nodular aggregates of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and abundant plasma cells in both the superficial and deep dermis (Figure 1). There were perivascular and periadnexal aggregates of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and numerous plasma cells (Figure 2). Special stains for organisms, including Warthin-Starry silver, Giemsa, acid-fast bacilli, Gomori methenamine-silver, and Brown-Brenn stains were negative. Immunoperoxidase stain for Treponema pallidum also was negative. The patient’s rapid plasma reagin titer at the time of the fourth biopsy was 1:256, and appropriate treatment with penicillin resulted in complete clearance of the lesions in 3 to 4 weeks.

|

| Figure 1. Superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphohistiocytic infiltrate (H&E, original magnification ×2). |

|

| Figure 2. Perivascular and periadnexal aggregates of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and numerous plasma cells (H&E, original magnification ×20). |

Syphilis is caused by T pallidum. Three stages typically are identified in immunocompetent hosts: primary, secondary, and tertiary syphilis. Immunocompromised patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection may have unusual presentations.

Lues maligna is used to describe a rare noduloulcerative form of secondary syphilis.1 It was first described in 18592 and has been associated with other disorders such as diabetes mellitus3 and chronic alcoholism.4 Patients usually are gravely ill and develop polymorphic ulcerating lesions. Facial and scalp involvement are common, but patients typically do not have palmoplantar involvement in conventional presentations of secondary syphilis.

A scanning view of a punch biopsy from our patient revealed irregular acanthosis of the epidermis with long and thin rete pegs, a bandlike infiltrate at the dermoepidermal junction, and a dense superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal infiltrate. The histologic differential diagnosis includes pyoderma gangrenosum, vasculitis, lymphoma, leishmaniasis, leprosy, yaws, and mycobacterial or fungal infections.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends screening of all HIV-positive indivi-duals for syphilis, and all sexually active individuals with syphilis should be screened for HIV.5 If clinical examination and findings suggest syphilis in the presence of negative serologic testing, then direct fluorescence assay for T pallidum staining of lesions, exudates or biopsy, or dark-field microscopic examination should be performed. In our case, dark-field microscopy was not performed and serologic tests were negative at presentation. Silver stains can detect T pallidum in tissue specimens, though detection may not be possible late in the course of disease.6

The morphology and rapid response to treatment confirmed the diagnosis in our patient. The incidence of syphilis in HIV-positive patients has risen substantially in the last 2 decades. This case illustrates an uncommon presentation that is increasing in prevalence.

1. Fisher DA, Chang LW, Tuffanelli DL. Lues maligna: presentation of a case and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 1969;99:70-73.

2. Passoni LF, de Menezes JA, Ribeiro SR, et al. Lues maligna in an HIV-infected patient [published online ahead of print March 30, 2005]. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2005;38:181-184.

3. Hofmann UB, Hund M, Bröcker EB, et al. Lues maligna in a female patient with diabetes [in German]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3:780-782.

4. Bayramgürler D, Bilen N, Yildiz K, et al. Lues maligna in a chronic alcoholic patient. J Dermatol. 2005;32:217-219.

5. Centers for Disease Control. Recommendations for diagnosing and treating syphilis in HIV-infected patients. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1988;37:600-602.

6. Mannara GM. Bilateral secondary syphilis of the tonsil. J Laryngol Otol. 1999;113:1125-1127.

1. Fisher DA, Chang LW, Tuffanelli DL. Lues maligna: presentation of a case and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 1969;99:70-73.

2. Passoni LF, de Menezes JA, Ribeiro SR, et al. Lues maligna in an HIV-infected patient [published online ahead of print March 30, 2005]. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2005;38:181-184.

3. Hofmann UB, Hund M, Bröcker EB, et al. Lues maligna in a female patient with diabetes [in German]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3:780-782.

4. Bayramgürler D, Bilen N, Yildiz K, et al. Lues maligna in a chronic alcoholic patient. J Dermatol. 2005;32:217-219.

5. Centers for Disease Control. Recommendations for diagnosing and treating syphilis in HIV-infected patients. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1988;37:600-602.

6. Mannara GM. Bilateral secondary syphilis of the tonsil. J Laryngol Otol. 1999;113:1125-1127.

A 43-year-old man presented with a rapidly enlarging ulcerated nodule on the right ankle with a necrotic and crusted center. He also had multiple red-brown papules on the trunk and extremities. Some of these lesions had central erosions, while others had surface scale. He was known to be human immunodeficiency virus positive but had no lymphadenopathy. The CD4+ lymphocyte count was 153 cells/mm3 (reference range, 400–1600 cells/mm3) and he was on highly active antiretroviral therapy.