User login

Hyperkeratotic Papules and Black Macules on the Hands

THE DIAGNOSIS: Acral Hemorrhagic Darier Disease

Darier disease (DD), also known as keratosis follicularis, is a rare autosomal-dominant genodermatosis caused by mutations in the ATPase sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ transporting 2 gene (ATP2A2). This gene encodes the enzyme sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2, which results in abnormal calcium signaling in keratinocytes and leads to dyskeratosis.1 Darier disease commonly manifests in the second decade of life with hyperkeratotic papules coalescing into plaques, often accompanied by erosions and fissures that cause discomfort and pruritus. Darier disease also is associated with characteristic nail findings such as the classic candy cane nails and V-shaped nicking.

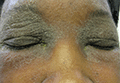

Acral hemorrhagic lesions are a rare manifestation of DD. Clinically, these lesions can manifest as hemorrhagic macules, papules, and/or vesicles, most commonly occurring following local trauma or retinoid use. Patients with these lesions are believed to have either specific mutations in the ATP2A2 gene that impair sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2 function in the vascular endothelium or a mutation in the sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase protein itself, leading to dysregulation of mitochondrial homeostasis from within the cell, provoking oxidative stress and causing detrimental effects on blood vessels.2 Patients with this variant can present with all the features of classic DD concomitantly, with varying symptom severity or distinct clinical features during separate episodic flares, or as the sole manifestation. Other nonclassical lesions of DD include acral keratoderma, giant comedones, keloidlike vegetations, and leucodermic macules (Figure).3

Acral hemorrhagic DD may appear either in isolation or in tandem with more traditional symptoms, necessitating consideration of other possible differential diagnoses such as acrokeratosis verruciformis of Hopf (AKV), porphyria cutanea tarda, bullous lichen planus (BLP), and hemorrhagic lichen sclerosus.

Sometimes regarded as a variant of DD, AKV is an autosomal- dominant genodermatosis characterized by flat or verrucous hyperkeratotic papules on the hands and feet. In AKV, the nails also may be affected, with changes including striations, subungual hyperkeratosis, and V-shaped nicking of the distal nails. Although our patient displayed features of AKV, it has not been associated with acral hemorrhagic macules, making this diagnosis less likely than DD.4

Porphyria cutanea tarda, a condition caused by decreased levels of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase, also can cause skin manifestations such as blistering as well as increased skin fragility, predominantly in sun-exposed areas.5 Our patient’s lack of photosensitivity and absence of other common symptoms of this disorder, such as hypertrichosis and hyperpigmentation, made porphyria cutanea tarda less likely.

Bullous lichen planus is a rare subtype of lichen planus characterized by tense bullae arising from preexisting lichen planus lesions or appearing de novo, most commonly manifesting on the oral mucosa or the legs.6 The bullae associated with BLP can rupture and form ulcers—a symptom that could potentially be mistaken for hemorrhagic macules like the ones observed in our patient. However, BLP typically is characterized by erythematous, violaceous, polygonal papules commonly appearing on the oral mucosa and the legs with blisters developing near or on pre-existing lichen planus lesions. These are different from the hyperkeratotic papules and leucodermic macules seen in our patient, which aligned more closely with the clinical presentation of DD.

Hemorrhagic lichen sclerosus presents with white atrophic patches and plaques and hemorrhagic bullae, which may resemble the leucodermic macules and hemorrhagic macules of DD. However, hemorrhagic lichen sclerosus most commonly involves the genital area in postmenopausal women. Extragenital manifestations of lichen sclerosus, although less common, can occur and typically manifest on the thighs, buttocks, breasts, back, chest, axillae, shoulders, and wrists.7 Notably, these hemorrhagic lesions typically are surrounded by hypopigmented skin and display an atrophic appearance.

Management of DD can be challenging. General measures include sun protection, heat avoidance, and friction reduction. Retinoids are considered the first-line therapy for severe DD, as they help normalize keratinocyte differentiation and reduce keratotic scaling.8 Topical corticosteroids can help manage inflammation and reduce the risk for secondary infections. Our patient responded well to this treatment approach, with a notable reduction in the number and severity of the hyperkeratotic plaques and resolution of the acral hemorrhagic lesions.

- Savignac M, Edir A, Simon M, et al. Darier disease: a disease model of impaired calcium homeostasis in the skin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813:1111-1117. doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.12.006

- Hong E, Hu R, Posligua A, et al. Acral hemorrhagic Darier disease: a case report of a rare presentation and literature review. JAAD Case Rep. 2023;31:93-96. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.05.030

- Yeshurun A, Ziv M, Cohen-Barak E, et al. An update on the cutaneous manifestations of Darier disease. J Cutan Med Surg. 2021;25:498-503. doi:10.1177/1203475421999331

- Williams GM, Lincoln M. Acrokeratosis verruciformis of Hopf. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; May 1, 2023.

- Shah A, Bhatt H. Cutanea tarda porphyria. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; April 17, 2023.

- Liakopoulou A, Rallis E. Bullous lichen planus—a review. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2017;11:1-4. doi:10.3315/jdcr.2017.1239

- Arnold N, Manway M, Stephenson S, et al. Extragenital bullous lichen sclerosus on the anterior lower extremities: report of a case and literature review. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030

- Haber RN, Dib NG. Management of Darier disease: a review of the literature and update. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2021;87:14-21. doi:10.25259/IJDVL_963_19 /qt8dn3p7kv.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Acral Hemorrhagic Darier Disease

Darier disease (DD), also known as keratosis follicularis, is a rare autosomal-dominant genodermatosis caused by mutations in the ATPase sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ transporting 2 gene (ATP2A2). This gene encodes the enzyme sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2, which results in abnormal calcium signaling in keratinocytes and leads to dyskeratosis.1 Darier disease commonly manifests in the second decade of life with hyperkeratotic papules coalescing into plaques, often accompanied by erosions and fissures that cause discomfort and pruritus. Darier disease also is associated with characteristic nail findings such as the classic candy cane nails and V-shaped nicking.

Acral hemorrhagic lesions are a rare manifestation of DD. Clinically, these lesions can manifest as hemorrhagic macules, papules, and/or vesicles, most commonly occurring following local trauma or retinoid use. Patients with these lesions are believed to have either specific mutations in the ATP2A2 gene that impair sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2 function in the vascular endothelium or a mutation in the sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase protein itself, leading to dysregulation of mitochondrial homeostasis from within the cell, provoking oxidative stress and causing detrimental effects on blood vessels.2 Patients with this variant can present with all the features of classic DD concomitantly, with varying symptom severity or distinct clinical features during separate episodic flares, or as the sole manifestation. Other nonclassical lesions of DD include acral keratoderma, giant comedones, keloidlike vegetations, and leucodermic macules (Figure).3

Acral hemorrhagic DD may appear either in isolation or in tandem with more traditional symptoms, necessitating consideration of other possible differential diagnoses such as acrokeratosis verruciformis of Hopf (AKV), porphyria cutanea tarda, bullous lichen planus (BLP), and hemorrhagic lichen sclerosus.

Sometimes regarded as a variant of DD, AKV is an autosomal- dominant genodermatosis characterized by flat or verrucous hyperkeratotic papules on the hands and feet. In AKV, the nails also may be affected, with changes including striations, subungual hyperkeratosis, and V-shaped nicking of the distal nails. Although our patient displayed features of AKV, it has not been associated with acral hemorrhagic macules, making this diagnosis less likely than DD.4

Porphyria cutanea tarda, a condition caused by decreased levels of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase, also can cause skin manifestations such as blistering as well as increased skin fragility, predominantly in sun-exposed areas.5 Our patient’s lack of photosensitivity and absence of other common symptoms of this disorder, such as hypertrichosis and hyperpigmentation, made porphyria cutanea tarda less likely.

Bullous lichen planus is a rare subtype of lichen planus characterized by tense bullae arising from preexisting lichen planus lesions or appearing de novo, most commonly manifesting on the oral mucosa or the legs.6 The bullae associated with BLP can rupture and form ulcers—a symptom that could potentially be mistaken for hemorrhagic macules like the ones observed in our patient. However, BLP typically is characterized by erythematous, violaceous, polygonal papules commonly appearing on the oral mucosa and the legs with blisters developing near or on pre-existing lichen planus lesions. These are different from the hyperkeratotic papules and leucodermic macules seen in our patient, which aligned more closely with the clinical presentation of DD.

Hemorrhagic lichen sclerosus presents with white atrophic patches and plaques and hemorrhagic bullae, which may resemble the leucodermic macules and hemorrhagic macules of DD. However, hemorrhagic lichen sclerosus most commonly involves the genital area in postmenopausal women. Extragenital manifestations of lichen sclerosus, although less common, can occur and typically manifest on the thighs, buttocks, breasts, back, chest, axillae, shoulders, and wrists.7 Notably, these hemorrhagic lesions typically are surrounded by hypopigmented skin and display an atrophic appearance.

Management of DD can be challenging. General measures include sun protection, heat avoidance, and friction reduction. Retinoids are considered the first-line therapy for severe DD, as they help normalize keratinocyte differentiation and reduce keratotic scaling.8 Topical corticosteroids can help manage inflammation and reduce the risk for secondary infections. Our patient responded well to this treatment approach, with a notable reduction in the number and severity of the hyperkeratotic plaques and resolution of the acral hemorrhagic lesions.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Acral Hemorrhagic Darier Disease

Darier disease (DD), also known as keratosis follicularis, is a rare autosomal-dominant genodermatosis caused by mutations in the ATPase sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ transporting 2 gene (ATP2A2). This gene encodes the enzyme sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2, which results in abnormal calcium signaling in keratinocytes and leads to dyskeratosis.1 Darier disease commonly manifests in the second decade of life with hyperkeratotic papules coalescing into plaques, often accompanied by erosions and fissures that cause discomfort and pruritus. Darier disease also is associated with characteristic nail findings such as the classic candy cane nails and V-shaped nicking.

Acral hemorrhagic lesions are a rare manifestation of DD. Clinically, these lesions can manifest as hemorrhagic macules, papules, and/or vesicles, most commonly occurring following local trauma or retinoid use. Patients with these lesions are believed to have either specific mutations in the ATP2A2 gene that impair sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2 function in the vascular endothelium or a mutation in the sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase protein itself, leading to dysregulation of mitochondrial homeostasis from within the cell, provoking oxidative stress and causing detrimental effects on blood vessels.2 Patients with this variant can present with all the features of classic DD concomitantly, with varying symptom severity or distinct clinical features during separate episodic flares, or as the sole manifestation. Other nonclassical lesions of DD include acral keratoderma, giant comedones, keloidlike vegetations, and leucodermic macules (Figure).3

Acral hemorrhagic DD may appear either in isolation or in tandem with more traditional symptoms, necessitating consideration of other possible differential diagnoses such as acrokeratosis verruciformis of Hopf (AKV), porphyria cutanea tarda, bullous lichen planus (BLP), and hemorrhagic lichen sclerosus.

Sometimes regarded as a variant of DD, AKV is an autosomal- dominant genodermatosis characterized by flat or verrucous hyperkeratotic papules on the hands and feet. In AKV, the nails also may be affected, with changes including striations, subungual hyperkeratosis, and V-shaped nicking of the distal nails. Although our patient displayed features of AKV, it has not been associated with acral hemorrhagic macules, making this diagnosis less likely than DD.4

Porphyria cutanea tarda, a condition caused by decreased levels of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase, also can cause skin manifestations such as blistering as well as increased skin fragility, predominantly in sun-exposed areas.5 Our patient’s lack of photosensitivity and absence of other common symptoms of this disorder, such as hypertrichosis and hyperpigmentation, made porphyria cutanea tarda less likely.

Bullous lichen planus is a rare subtype of lichen planus characterized by tense bullae arising from preexisting lichen planus lesions or appearing de novo, most commonly manifesting on the oral mucosa or the legs.6 The bullae associated with BLP can rupture and form ulcers—a symptom that could potentially be mistaken for hemorrhagic macules like the ones observed in our patient. However, BLP typically is characterized by erythematous, violaceous, polygonal papules commonly appearing on the oral mucosa and the legs with blisters developing near or on pre-existing lichen planus lesions. These are different from the hyperkeratotic papules and leucodermic macules seen in our patient, which aligned more closely with the clinical presentation of DD.

Hemorrhagic lichen sclerosus presents with white atrophic patches and plaques and hemorrhagic bullae, which may resemble the leucodermic macules and hemorrhagic macules of DD. However, hemorrhagic lichen sclerosus most commonly involves the genital area in postmenopausal women. Extragenital manifestations of lichen sclerosus, although less common, can occur and typically manifest on the thighs, buttocks, breasts, back, chest, axillae, shoulders, and wrists.7 Notably, these hemorrhagic lesions typically are surrounded by hypopigmented skin and display an atrophic appearance.

Management of DD can be challenging. General measures include sun protection, heat avoidance, and friction reduction. Retinoids are considered the first-line therapy for severe DD, as they help normalize keratinocyte differentiation and reduce keratotic scaling.8 Topical corticosteroids can help manage inflammation and reduce the risk for secondary infections. Our patient responded well to this treatment approach, with a notable reduction in the number and severity of the hyperkeratotic plaques and resolution of the acral hemorrhagic lesions.

- Savignac M, Edir A, Simon M, et al. Darier disease: a disease model of impaired calcium homeostasis in the skin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813:1111-1117. doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.12.006

- Hong E, Hu R, Posligua A, et al. Acral hemorrhagic Darier disease: a case report of a rare presentation and literature review. JAAD Case Rep. 2023;31:93-96. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.05.030

- Yeshurun A, Ziv M, Cohen-Barak E, et al. An update on the cutaneous manifestations of Darier disease. J Cutan Med Surg. 2021;25:498-503. doi:10.1177/1203475421999331

- Williams GM, Lincoln M. Acrokeratosis verruciformis of Hopf. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; May 1, 2023.

- Shah A, Bhatt H. Cutanea tarda porphyria. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; April 17, 2023.

- Liakopoulou A, Rallis E. Bullous lichen planus—a review. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2017;11:1-4. doi:10.3315/jdcr.2017.1239

- Arnold N, Manway M, Stephenson S, et al. Extragenital bullous lichen sclerosus on the anterior lower extremities: report of a case and literature review. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030

- Haber RN, Dib NG. Management of Darier disease: a review of the literature and update. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2021;87:14-21. doi:10.25259/IJDVL_963_19 /qt8dn3p7kv.

- Savignac M, Edir A, Simon M, et al. Darier disease: a disease model of impaired calcium homeostasis in the skin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813:1111-1117. doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.12.006

- Hong E, Hu R, Posligua A, et al. Acral hemorrhagic Darier disease: a case report of a rare presentation and literature review. JAAD Case Rep. 2023;31:93-96. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.05.030

- Yeshurun A, Ziv M, Cohen-Barak E, et al. An update on the cutaneous manifestations of Darier disease. J Cutan Med Surg. 2021;25:498-503. doi:10.1177/1203475421999331

- Williams GM, Lincoln M. Acrokeratosis verruciformis of Hopf. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; May 1, 2023.

- Shah A, Bhatt H. Cutanea tarda porphyria. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; April 17, 2023.

- Liakopoulou A, Rallis E. Bullous lichen planus—a review. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2017;11:1-4. doi:10.3315/jdcr.2017.1239

- Arnold N, Manway M, Stephenson S, et al. Extragenital bullous lichen sclerosus on the anterior lower extremities: report of a case and literature review. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030

- Haber RN, Dib NG. Management of Darier disease: a review of the literature and update. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2021;87:14-21. doi:10.25259/IJDVL_963_19 /qt8dn3p7kv.

An elderly woman with a long history of hyperkeratotic papules on the abdomen, forearms, dorsal hands, and skinfolds presented with new lesions on the dorsal hands that had developed over the preceding few months after a lapse in treatment with her previous dermatologist. Her medical history was otherwise unremarkable. Physical examination revealed hyperkeratotic papules, black hemorrhagic macules with jagged borders, and a thin hemorrhagic plaque on the dorsal hands. Nail findings were notable for alternating white and red longitudinal bands with nicking of the distal nail plates. She also had scattered leucodermic macules over the trunk, feet, arms, and legs, as well as numerous hyperkeratotic papules coalescing into plaques over the mons pubis and in the inguinal folds.

Staphylococcal Scalded Skin Syndrome in Pregnancy

To the Editor:

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS) is a superficial blistering disorder mediated by Staphylococcus aureus exfoliative toxins (ETs).1 It is rare in adults, but when diagnosed, it is often associated with renal failure, immunodeficiency, or overwhelming staphylococcal infection.2 We present a unique case of a pregnant woman with chronic atopic dermatitis (AD) who developed SSSS.

A 21-year-old gravida 3, para 2, aborta 0pregnant woman (29 weeks’ gestation) with a history of chronic AD who was hospitalized with facial edema, purulent ocular discharge, and substantial worsening of AD presented for a dermatology consultation. Her AD was previously managed with topical steroids but had been complicated by multiple methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections. On physical examination, she had substantial periorbital edema with purulent discharge from both eyes (Figure 1A), perioral crust with radial fissures (Figure 2A), and mild generalized facial swelling and desquamation (Figure 3). However, the oral cavity was not involved. She had diffuse desquamation in addition to chronic lichenified plaques of the arms, legs, and trunk and SSSS was clinically diagnosed. Cultures of conjunctival discharge were positive for MRSA. The patient was treated with intravenous vancomycin and had a full recovery (Figures 1B and 2B). She delivered a healthy newborn with Apgar scores of 9 and 9 at 1 and 5 minutes, respectively, at 36 weeks and 6 days’ gestation by cesarean delivery; however, her postoperative care was complicated by preeclampsia, which was treated with magnesium sulfate. The newborn showed no evidence of infection or blistering at birth or during the hospital stay.

|

| ||

Figure 1. Periorbital edema with purulent ocular discharge before (A) and after (B) treatment. | Figure 2. Perioral desquamation and radial fissuring before (A) and after (B) treatment. |

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome is a superficial blistering disorder that ranges in severity from localized blisters to generalized exfoliation.1 Exfoliative toxin is the major virulence factor responsible for SSSS. Exfoliative toxin is a serine protease that targets desmoglein 1, resulting in intraepidermal separation of keratinocytes.3 Two serologically distinct exfoliative toxins—ETA and ETB—have been associated with human disease.4 Although ETA is encoded on a phage genome, ETB is encoded on a large plasmid.3 Initially it was thought that only strains of S aureus carrying lytic group II phages were responsible for ET production; however, it is now accepted that all phage groups are capable of producing ET and causing SSSS.1

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome is most common in infants and children and rare in adults. Although it has been occasionally described in otherwise healthy adults,5 it is most often diagnosed in patients with renal failure (decreased toxin excretion), immunodeficiency (lack of antibodies against toxins), and overwhelming staphylococcal infection (excessive toxin).2 Mortality in treated children is low, but it can reach almost 60% in adults1; therefore, defining risk factors that may aid in early diagnosis are exceedingly important.

We believe that both our patient’s history of AD and her pregnancy contributed to the development of SSSS. The patient had a history of multiple MRSA infections prior to this hospitalization, suggesting MRSA colonization, which is a common complication of AD with more than 75% of AD patients colonized with S aureus.6 Additionally, S aureus superantigen stimulation can result in the loss of regulatory T cells’ natural immunosuppression. Regulatory T cells are remarkably increased in patients with AD; therefore, the inflammatory response to S aureus is likely amplified in an atopic patient, as there is more native immunosuppressive capacity to be affected.4 Furthermore, we believe that pregnancy and its associated immunomodulation is a risk for SSSS. Immune changes in pregnancy are still not well understood; however, it is known that there are alterations to allow symbiosis between the mother and fetus. Anti-ET IgG antibodies are thought to play an important role in protecting against SSSS. Historically, studies on serum immunoglobulin levels during pregnancy have had conflicting findings. They have shown that IgG is either unchanged or decreased, while IgA, IgE, and IgM can be increased, decreased, or unchanged.7 In a study of immunoglobulins in pregnancy, Bahna et al7 showed that IgE is unchanged over the course of pregnancy, but their analysis did not address IgG levels. If IgG levels in fact decrease during pregnancy, the mother could be at risk for SSSS due to her inability to neutralize toxins. Even if total IgG levels remain unchanged, it is possible that specific antitoxin antibodies are decreased. Additionally, there is a documented suppression and alteration in T-cell response to prevent fetal rejection during pregnancy.8 Adult SSSS has been documented several times in human immunodeficiency virus–positive patients, suggesting there may be some association between T-cell suppression and SSSS susceptibility.9 Interestingly, pregnancy, similar to AD, results in an increase in immunosuppressive T cells,10 which, if deactivated by superantigens, could potentially contribute to an increased inflammatory response. All of these immune system alterations likely leave the mother vulnerable to toxin-mediated events such as SSSS.

We believe this case highlights the importance of considering SSSS in both atopic and pregnant patients with desquamating eruptions. In the case of pregnant patients, it is important to consider the risks and benefits of any medical treatments for both the mother and infant. Vancomycin is a pregnancy category B drug and was chosen for its known effectiveness and safety in pregnancy. One study compared 10 babies with mothers who were treated with vancomycin during the second and third trimesters for MRSA to 20 babies with mothers who did not receive vancomycin and did not find an increased risk for sensorineural hearing loss or nephrotoxicity.11 There is no known increased risk for preeclampsia with vancomycin, but some studies have suggested that maternal infection independently increases the risk for preeclampsia.12 Other treatment options were not as safe as vancomycin in this case: doxycycline is contraindicated (pregnancy category D) due to the potential for staining of deciduous teeth and skeletal growth impairment, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is a pregnancy category D drug during the third trimester due to the risk of kernicterus, and linezolid is a pregnancy category C drug.13

1. Ladhani S. Recent developments in staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2001;7:301-307.

2. Ladhani S, Joannou CL, Lochrie DP, et al. Clinical, microbial, and biochemical aspects of the exfoliative toxins causing staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:224-242.

3. Kato F, Kadomoto N, Iwamoto Y, et al. Regulatory mechanism for exfoliative toxin production in Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immun. 2011;79:1660-1670.

4. Iwatsuki K, Yamasaki O, Morizane S, et al. Staphylococcal cutaneous infections: invasion, evasion and aggression. J Dermatol Sci. 2006;42:203-214.

5. Opal SM, Johnson-Winegar AD, Cross AS. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in two immunocompetent adults caused by exfoliation B-producing Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:1283-1286.

6. Hill SE, Yung A, Rademaker M. Prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus and antibiotic resistance in children with atopic dermatitis: a New Zealand experience. Australas J Dermatol. 2011;52:27-31.

7. Bahna SL, Woo CK, Manuel PV, et al. Serum total IgE level during pregnancy and postpartum. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2011;39:291-294.

8. Poole JA, Claman HN. Immunology of pregnancy: implications for the mother. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2004;26:161-170.

9. Farrell AM, Ross JS, Umasankar S, et al. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in an HIV-1 seropositive man. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:962-965.

10. Somerset DA, Zheng Y, Kilby MD, et al. Normal human pregnancy is associated with an elevation in the immune suppressive CD251 CD41 regulatory T-cell subset. Immunology. 2004;112:38-43.

11. Reyes MP, Ostrea EM Jr, Carbinian AE, et al. Vancomycin during pregnancy: does it cause hearing loss or nephrotoxicity in the infant? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;161:977-981.

12. Rustveldt LO, Kelsey SF, Sharma, R. Associations between maternal infections and preeclampsia: a systemic review of epidemiologic studies. Matern Child Health J. 2008;12: 223-242.

13. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 2nd ed. Barcelona, Spain: Elsevier Limited; 2008.

To the Editor:

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS) is a superficial blistering disorder mediated by Staphylococcus aureus exfoliative toxins (ETs).1 It is rare in adults, but when diagnosed, it is often associated with renal failure, immunodeficiency, or overwhelming staphylococcal infection.2 We present a unique case of a pregnant woman with chronic atopic dermatitis (AD) who developed SSSS.

A 21-year-old gravida 3, para 2, aborta 0pregnant woman (29 weeks’ gestation) with a history of chronic AD who was hospitalized with facial edema, purulent ocular discharge, and substantial worsening of AD presented for a dermatology consultation. Her AD was previously managed with topical steroids but had been complicated by multiple methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections. On physical examination, she had substantial periorbital edema with purulent discharge from both eyes (Figure 1A), perioral crust with radial fissures (Figure 2A), and mild generalized facial swelling and desquamation (Figure 3). However, the oral cavity was not involved. She had diffuse desquamation in addition to chronic lichenified plaques of the arms, legs, and trunk and SSSS was clinically diagnosed. Cultures of conjunctival discharge were positive for MRSA. The patient was treated with intravenous vancomycin and had a full recovery (Figures 1B and 2B). She delivered a healthy newborn with Apgar scores of 9 and 9 at 1 and 5 minutes, respectively, at 36 weeks and 6 days’ gestation by cesarean delivery; however, her postoperative care was complicated by preeclampsia, which was treated with magnesium sulfate. The newborn showed no evidence of infection or blistering at birth or during the hospital stay.

|

| ||

Figure 1. Periorbital edema with purulent ocular discharge before (A) and after (B) treatment. | Figure 2. Perioral desquamation and radial fissuring before (A) and after (B) treatment. |

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome is a superficial blistering disorder that ranges in severity from localized blisters to generalized exfoliation.1 Exfoliative toxin is the major virulence factor responsible for SSSS. Exfoliative toxin is a serine protease that targets desmoglein 1, resulting in intraepidermal separation of keratinocytes.3 Two serologically distinct exfoliative toxins—ETA and ETB—have been associated with human disease.4 Although ETA is encoded on a phage genome, ETB is encoded on a large plasmid.3 Initially it was thought that only strains of S aureus carrying lytic group II phages were responsible for ET production; however, it is now accepted that all phage groups are capable of producing ET and causing SSSS.1

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome is most common in infants and children and rare in adults. Although it has been occasionally described in otherwise healthy adults,5 it is most often diagnosed in patients with renal failure (decreased toxin excretion), immunodeficiency (lack of antibodies against toxins), and overwhelming staphylococcal infection (excessive toxin).2 Mortality in treated children is low, but it can reach almost 60% in adults1; therefore, defining risk factors that may aid in early diagnosis are exceedingly important.

We believe that both our patient’s history of AD and her pregnancy contributed to the development of SSSS. The patient had a history of multiple MRSA infections prior to this hospitalization, suggesting MRSA colonization, which is a common complication of AD with more than 75% of AD patients colonized with S aureus.6 Additionally, S aureus superantigen stimulation can result in the loss of regulatory T cells’ natural immunosuppression. Regulatory T cells are remarkably increased in patients with AD; therefore, the inflammatory response to S aureus is likely amplified in an atopic patient, as there is more native immunosuppressive capacity to be affected.4 Furthermore, we believe that pregnancy and its associated immunomodulation is a risk for SSSS. Immune changes in pregnancy are still not well understood; however, it is known that there are alterations to allow symbiosis between the mother and fetus. Anti-ET IgG antibodies are thought to play an important role in protecting against SSSS. Historically, studies on serum immunoglobulin levels during pregnancy have had conflicting findings. They have shown that IgG is either unchanged or decreased, while IgA, IgE, and IgM can be increased, decreased, or unchanged.7 In a study of immunoglobulins in pregnancy, Bahna et al7 showed that IgE is unchanged over the course of pregnancy, but their analysis did not address IgG levels. If IgG levels in fact decrease during pregnancy, the mother could be at risk for SSSS due to her inability to neutralize toxins. Even if total IgG levels remain unchanged, it is possible that specific antitoxin antibodies are decreased. Additionally, there is a documented suppression and alteration in T-cell response to prevent fetal rejection during pregnancy.8 Adult SSSS has been documented several times in human immunodeficiency virus–positive patients, suggesting there may be some association between T-cell suppression and SSSS susceptibility.9 Interestingly, pregnancy, similar to AD, results in an increase in immunosuppressive T cells,10 which, if deactivated by superantigens, could potentially contribute to an increased inflammatory response. All of these immune system alterations likely leave the mother vulnerable to toxin-mediated events such as SSSS.

We believe this case highlights the importance of considering SSSS in both atopic and pregnant patients with desquamating eruptions. In the case of pregnant patients, it is important to consider the risks and benefits of any medical treatments for both the mother and infant. Vancomycin is a pregnancy category B drug and was chosen for its known effectiveness and safety in pregnancy. One study compared 10 babies with mothers who were treated with vancomycin during the second and third trimesters for MRSA to 20 babies with mothers who did not receive vancomycin and did not find an increased risk for sensorineural hearing loss or nephrotoxicity.11 There is no known increased risk for preeclampsia with vancomycin, but some studies have suggested that maternal infection independently increases the risk for preeclampsia.12 Other treatment options were not as safe as vancomycin in this case: doxycycline is contraindicated (pregnancy category D) due to the potential for staining of deciduous teeth and skeletal growth impairment, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is a pregnancy category D drug during the third trimester due to the risk of kernicterus, and linezolid is a pregnancy category C drug.13

To the Editor:

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS) is a superficial blistering disorder mediated by Staphylococcus aureus exfoliative toxins (ETs).1 It is rare in adults, but when diagnosed, it is often associated with renal failure, immunodeficiency, or overwhelming staphylococcal infection.2 We present a unique case of a pregnant woman with chronic atopic dermatitis (AD) who developed SSSS.

A 21-year-old gravida 3, para 2, aborta 0pregnant woman (29 weeks’ gestation) with a history of chronic AD who was hospitalized with facial edema, purulent ocular discharge, and substantial worsening of AD presented for a dermatology consultation. Her AD was previously managed with topical steroids but had been complicated by multiple methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections. On physical examination, she had substantial periorbital edema with purulent discharge from both eyes (Figure 1A), perioral crust with radial fissures (Figure 2A), and mild generalized facial swelling and desquamation (Figure 3). However, the oral cavity was not involved. She had diffuse desquamation in addition to chronic lichenified plaques of the arms, legs, and trunk and SSSS was clinically diagnosed. Cultures of conjunctival discharge were positive for MRSA. The patient was treated with intravenous vancomycin and had a full recovery (Figures 1B and 2B). She delivered a healthy newborn with Apgar scores of 9 and 9 at 1 and 5 minutes, respectively, at 36 weeks and 6 days’ gestation by cesarean delivery; however, her postoperative care was complicated by preeclampsia, which was treated with magnesium sulfate. The newborn showed no evidence of infection or blistering at birth or during the hospital stay.

|

| ||

Figure 1. Periorbital edema with purulent ocular discharge before (A) and after (B) treatment. | Figure 2. Perioral desquamation and radial fissuring before (A) and after (B) treatment. |

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome is a superficial blistering disorder that ranges in severity from localized blisters to generalized exfoliation.1 Exfoliative toxin is the major virulence factor responsible for SSSS. Exfoliative toxin is a serine protease that targets desmoglein 1, resulting in intraepidermal separation of keratinocytes.3 Two serologically distinct exfoliative toxins—ETA and ETB—have been associated with human disease.4 Although ETA is encoded on a phage genome, ETB is encoded on a large plasmid.3 Initially it was thought that only strains of S aureus carrying lytic group II phages were responsible for ET production; however, it is now accepted that all phage groups are capable of producing ET and causing SSSS.1

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome is most common in infants and children and rare in adults. Although it has been occasionally described in otherwise healthy adults,5 it is most often diagnosed in patients with renal failure (decreased toxin excretion), immunodeficiency (lack of antibodies against toxins), and overwhelming staphylococcal infection (excessive toxin).2 Mortality in treated children is low, but it can reach almost 60% in adults1; therefore, defining risk factors that may aid in early diagnosis are exceedingly important.

We believe that both our patient’s history of AD and her pregnancy contributed to the development of SSSS. The patient had a history of multiple MRSA infections prior to this hospitalization, suggesting MRSA colonization, which is a common complication of AD with more than 75% of AD patients colonized with S aureus.6 Additionally, S aureus superantigen stimulation can result in the loss of regulatory T cells’ natural immunosuppression. Regulatory T cells are remarkably increased in patients with AD; therefore, the inflammatory response to S aureus is likely amplified in an atopic patient, as there is more native immunosuppressive capacity to be affected.4 Furthermore, we believe that pregnancy and its associated immunomodulation is a risk for SSSS. Immune changes in pregnancy are still not well understood; however, it is known that there are alterations to allow symbiosis between the mother and fetus. Anti-ET IgG antibodies are thought to play an important role in protecting against SSSS. Historically, studies on serum immunoglobulin levels during pregnancy have had conflicting findings. They have shown that IgG is either unchanged or decreased, while IgA, IgE, and IgM can be increased, decreased, or unchanged.7 In a study of immunoglobulins in pregnancy, Bahna et al7 showed that IgE is unchanged over the course of pregnancy, but their analysis did not address IgG levels. If IgG levels in fact decrease during pregnancy, the mother could be at risk for SSSS due to her inability to neutralize toxins. Even if total IgG levels remain unchanged, it is possible that specific antitoxin antibodies are decreased. Additionally, there is a documented suppression and alteration in T-cell response to prevent fetal rejection during pregnancy.8 Adult SSSS has been documented several times in human immunodeficiency virus–positive patients, suggesting there may be some association between T-cell suppression and SSSS susceptibility.9 Interestingly, pregnancy, similar to AD, results in an increase in immunosuppressive T cells,10 which, if deactivated by superantigens, could potentially contribute to an increased inflammatory response. All of these immune system alterations likely leave the mother vulnerable to toxin-mediated events such as SSSS.

We believe this case highlights the importance of considering SSSS in both atopic and pregnant patients with desquamating eruptions. In the case of pregnant patients, it is important to consider the risks and benefits of any medical treatments for both the mother and infant. Vancomycin is a pregnancy category B drug and was chosen for its known effectiveness and safety in pregnancy. One study compared 10 babies with mothers who were treated with vancomycin during the second and third trimesters for MRSA to 20 babies with mothers who did not receive vancomycin and did not find an increased risk for sensorineural hearing loss or nephrotoxicity.11 There is no known increased risk for preeclampsia with vancomycin, but some studies have suggested that maternal infection independently increases the risk for preeclampsia.12 Other treatment options were not as safe as vancomycin in this case: doxycycline is contraindicated (pregnancy category D) due to the potential for staining of deciduous teeth and skeletal growth impairment, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is a pregnancy category D drug during the third trimester due to the risk of kernicterus, and linezolid is a pregnancy category C drug.13

1. Ladhani S. Recent developments in staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2001;7:301-307.

2. Ladhani S, Joannou CL, Lochrie DP, et al. Clinical, microbial, and biochemical aspects of the exfoliative toxins causing staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:224-242.

3. Kato F, Kadomoto N, Iwamoto Y, et al. Regulatory mechanism for exfoliative toxin production in Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immun. 2011;79:1660-1670.

4. Iwatsuki K, Yamasaki O, Morizane S, et al. Staphylococcal cutaneous infections: invasion, evasion and aggression. J Dermatol Sci. 2006;42:203-214.

5. Opal SM, Johnson-Winegar AD, Cross AS. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in two immunocompetent adults caused by exfoliation B-producing Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:1283-1286.

6. Hill SE, Yung A, Rademaker M. Prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus and antibiotic resistance in children with atopic dermatitis: a New Zealand experience. Australas J Dermatol. 2011;52:27-31.

7. Bahna SL, Woo CK, Manuel PV, et al. Serum total IgE level during pregnancy and postpartum. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2011;39:291-294.

8. Poole JA, Claman HN. Immunology of pregnancy: implications for the mother. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2004;26:161-170.

9. Farrell AM, Ross JS, Umasankar S, et al. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in an HIV-1 seropositive man. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:962-965.

10. Somerset DA, Zheng Y, Kilby MD, et al. Normal human pregnancy is associated with an elevation in the immune suppressive CD251 CD41 regulatory T-cell subset. Immunology. 2004;112:38-43.

11. Reyes MP, Ostrea EM Jr, Carbinian AE, et al. Vancomycin during pregnancy: does it cause hearing loss or nephrotoxicity in the infant? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;161:977-981.

12. Rustveldt LO, Kelsey SF, Sharma, R. Associations between maternal infections and preeclampsia: a systemic review of epidemiologic studies. Matern Child Health J. 2008;12: 223-242.

13. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 2nd ed. Barcelona, Spain: Elsevier Limited; 2008.

1. Ladhani S. Recent developments in staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2001;7:301-307.

2. Ladhani S, Joannou CL, Lochrie DP, et al. Clinical, microbial, and biochemical aspects of the exfoliative toxins causing staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:224-242.

3. Kato F, Kadomoto N, Iwamoto Y, et al. Regulatory mechanism for exfoliative toxin production in Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immun. 2011;79:1660-1670.

4. Iwatsuki K, Yamasaki O, Morizane S, et al. Staphylococcal cutaneous infections: invasion, evasion and aggression. J Dermatol Sci. 2006;42:203-214.

5. Opal SM, Johnson-Winegar AD, Cross AS. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in two immunocompetent adults caused by exfoliation B-producing Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:1283-1286.

6. Hill SE, Yung A, Rademaker M. Prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus and antibiotic resistance in children with atopic dermatitis: a New Zealand experience. Australas J Dermatol. 2011;52:27-31.

7. Bahna SL, Woo CK, Manuel PV, et al. Serum total IgE level during pregnancy and postpartum. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2011;39:291-294.

8. Poole JA, Claman HN. Immunology of pregnancy: implications for the mother. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2004;26:161-170.

9. Farrell AM, Ross JS, Umasankar S, et al. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in an HIV-1 seropositive man. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:962-965.

10. Somerset DA, Zheng Y, Kilby MD, et al. Normal human pregnancy is associated with an elevation in the immune suppressive CD251 CD41 regulatory T-cell subset. Immunology. 2004;112:38-43.

11. Reyes MP, Ostrea EM Jr, Carbinian AE, et al. Vancomycin during pregnancy: does it cause hearing loss or nephrotoxicity in the infant? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;161:977-981.

12. Rustveldt LO, Kelsey SF, Sharma, R. Associations between maternal infections and preeclampsia: a systemic review of epidemiologic studies. Matern Child Health J. 2008;12: 223-242.

13. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 2nd ed. Barcelona, Spain: Elsevier Limited; 2008.