User login

What’s the most effective topical Tx for scalp psoriasis?

Single-agent therapy with a very potent or potent topical corticosteroid appears more effective than other topical agents, including vitamin D3 analogues, for treating scalp psoriasis (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Combined therapy with a vitamin D3 analogue and a potent topical corticosteroid may be slightly more effective than monotherapy with either agent (SOR: B, systematic reviews of RCTs with inconsistent results).

Evidence summary

A 2013 meta-analysis of 26 RCTs with 8020 patients evaluated topical treatments for scalp psoriasis as part of a subanalysis of a larger Cochrane review of psoriasis therapy.1 Only 20 studies reported the severity of disease: 13 studies looked at moderate to severe scalp psoriasis and the others examined mild to severe disease.

Results were reported as standardized mean differences (SMD) and also converted to a 6-point global improvement scale created by the authors to provide a combined endpoint of provider- or patient-assessed improvement in symptoms such as redness, thickness, and scaling. Higher scores indicate more improvement.

Compared with placebo, the very potent corticosteroid clobetasol propionate improved psoriasis by 1.9 points on the 6-point scale (4 trials, 788 patients; SMD= −1.6; 95% confidence interval [CI], −1.8 to −1.3). The potent steroid betamethasone diproprionate improved symptoms by 1.3 points compared with placebo (2 trials, 712 patients; SMD= −1.1; 95% CI, −1.3 to −0.90).

The topical corticosteroids clobetasol, betamethasone diproprionate, and betamethasone valerate improved symptoms more than the vitamin D3 analogue calcipotriol in head-to-head trials. The corticosteroid improvement scores exceeded calcipotriol scores by 0.5 points (1 trial, 151 patients; SMD=0.37; 95% CI, 0.05-0.69), 0.6 points (1 trial, 1676 patients; SMD=0.48; 95% CI, 0.32-0.64), and 0.5 points (1 trial, 510 patients; SMD=0.37; 95% CI, 0.20-0.55), respectively.

Combination therapy with a vitamin D3 analogue and a corticosteroid yielded approximately 0.2 points of improvement over corticosteroid alone (6 trials, 2444 patients; SMD= −0.18; 95% CI, −0.26 to −0.10). Four trials of combination therapy (2581 patients) resulted in 0.5 to 1.2 points of improvement compared with vitamin D3 analogues alone (SMD=0.64; 95% CI, 0.44-0.84). Specific strengths and dosing regimens weren’t reported.

The Cochrane systematic review, using the same outcome reporting methods, provided data on the vitamin D3 analogue calcipotriol compared with placebo for treating scalp psoriasis.2 Calcipotriol resulted in 0.9 points of improvement on the 6-point global improvement scale (2 trials, 457 patients; SMD= −0.72; 95% CI, −1.3 to −0.16).

Very potent corticosteroids show a better response than potent agents

In 2013, a meta-analysis of 13 placebo-controlled RCTs (5640 patients) evaluated topical therapies for scalp psoriasis licensed in the United Kingdom. This meta-analysis included the same placebo-controlled studies as the Cochrane review but added one study published after the search date of the review.3

The outcome reporting was different from the Cochrane review. The primary outcome was percentage of patients with at least moderate scalp psoriasis who achieved clear or nearly clear status on provider assessment scales. All treatments were compared to twice-daily placebo with a response rate of 11%.

Very potent steroids had response rates of 78% for twice-daily application (risk ratio [RR]=7.0; 95% CI, 5.6-8.0) and 69% for once-daily application (RR=6.2; 95% CI, 3.0-8.3). The combination of a vitamin D3 analogue and a potent corticosteroid showed a response rate of 64% (RR=5.7; 95% CI, 2.4-8.0) whereas response rates for potent corticosteroids alone were 57% (RR=5.0; 95% CI, 1.6-7.8) for once-daily application and 49% (RR=4.4; 95% CI, 2.2-6.7) for twice-daily administration. The authors suggested patient satisfaction at using once daily vs twice daily application as a possible explanation for the difference in response rate.

Vitamin D3 analogues showed response rates of approximately 34%, which is nonsignificant for once-daily application (RR=3.1; 95% CI, 0.71-6.6) but significant for twice-daily administration (RR=3.1; 95% CI, 1.3-5.9). Exact numbers of studies and participants, as well as specific agents and preparation information, were not included.

1. Mason AR, Mason JM, Cork MJ, et al. Topical treatments for chronic plaque psoriasis of the scalp: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:519-527.

2. Mason A, Mason J, Cork M, et al. Topical treatments for chronic plaque psoriasis: an abridged Cochrane systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013; 69:799-807.

3. Samarasekera EJ, Sawyer L, Wonderling D, et al. Topical therapies for the treatment of plaque psoriasis: systematic review and network meta-analyses. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:954-967.

Single-agent therapy with a very potent or potent topical corticosteroid appears more effective than other topical agents, including vitamin D3 analogues, for treating scalp psoriasis (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Combined therapy with a vitamin D3 analogue and a potent topical corticosteroid may be slightly more effective than monotherapy with either agent (SOR: B, systematic reviews of RCTs with inconsistent results).

Evidence summary

A 2013 meta-analysis of 26 RCTs with 8020 patients evaluated topical treatments for scalp psoriasis as part of a subanalysis of a larger Cochrane review of psoriasis therapy.1 Only 20 studies reported the severity of disease: 13 studies looked at moderate to severe scalp psoriasis and the others examined mild to severe disease.

Results were reported as standardized mean differences (SMD) and also converted to a 6-point global improvement scale created by the authors to provide a combined endpoint of provider- or patient-assessed improvement in symptoms such as redness, thickness, and scaling. Higher scores indicate more improvement.

Compared with placebo, the very potent corticosteroid clobetasol propionate improved psoriasis by 1.9 points on the 6-point scale (4 trials, 788 patients; SMD= −1.6; 95% confidence interval [CI], −1.8 to −1.3). The potent steroid betamethasone diproprionate improved symptoms by 1.3 points compared with placebo (2 trials, 712 patients; SMD= −1.1; 95% CI, −1.3 to −0.90).

The topical corticosteroids clobetasol, betamethasone diproprionate, and betamethasone valerate improved symptoms more than the vitamin D3 analogue calcipotriol in head-to-head trials. The corticosteroid improvement scores exceeded calcipotriol scores by 0.5 points (1 trial, 151 patients; SMD=0.37; 95% CI, 0.05-0.69), 0.6 points (1 trial, 1676 patients; SMD=0.48; 95% CI, 0.32-0.64), and 0.5 points (1 trial, 510 patients; SMD=0.37; 95% CI, 0.20-0.55), respectively.

Combination therapy with a vitamin D3 analogue and a corticosteroid yielded approximately 0.2 points of improvement over corticosteroid alone (6 trials, 2444 patients; SMD= −0.18; 95% CI, −0.26 to −0.10). Four trials of combination therapy (2581 patients) resulted in 0.5 to 1.2 points of improvement compared with vitamin D3 analogues alone (SMD=0.64; 95% CI, 0.44-0.84). Specific strengths and dosing regimens weren’t reported.

The Cochrane systematic review, using the same outcome reporting methods, provided data on the vitamin D3 analogue calcipotriol compared with placebo for treating scalp psoriasis.2 Calcipotriol resulted in 0.9 points of improvement on the 6-point global improvement scale (2 trials, 457 patients; SMD= −0.72; 95% CI, −1.3 to −0.16).

Very potent corticosteroids show a better response than potent agents

In 2013, a meta-analysis of 13 placebo-controlled RCTs (5640 patients) evaluated topical therapies for scalp psoriasis licensed in the United Kingdom. This meta-analysis included the same placebo-controlled studies as the Cochrane review but added one study published after the search date of the review.3

The outcome reporting was different from the Cochrane review. The primary outcome was percentage of patients with at least moderate scalp psoriasis who achieved clear or nearly clear status on provider assessment scales. All treatments were compared to twice-daily placebo with a response rate of 11%.

Very potent steroids had response rates of 78% for twice-daily application (risk ratio [RR]=7.0; 95% CI, 5.6-8.0) and 69% for once-daily application (RR=6.2; 95% CI, 3.0-8.3). The combination of a vitamin D3 analogue and a potent corticosteroid showed a response rate of 64% (RR=5.7; 95% CI, 2.4-8.0) whereas response rates for potent corticosteroids alone were 57% (RR=5.0; 95% CI, 1.6-7.8) for once-daily application and 49% (RR=4.4; 95% CI, 2.2-6.7) for twice-daily administration. The authors suggested patient satisfaction at using once daily vs twice daily application as a possible explanation for the difference in response rate.

Vitamin D3 analogues showed response rates of approximately 34%, which is nonsignificant for once-daily application (RR=3.1; 95% CI, 0.71-6.6) but significant for twice-daily administration (RR=3.1; 95% CI, 1.3-5.9). Exact numbers of studies and participants, as well as specific agents and preparation information, were not included.

Single-agent therapy with a very potent or potent topical corticosteroid appears more effective than other topical agents, including vitamin D3 analogues, for treating scalp psoriasis (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Combined therapy with a vitamin D3 analogue and a potent topical corticosteroid may be slightly more effective than monotherapy with either agent (SOR: B, systematic reviews of RCTs with inconsistent results).

Evidence summary

A 2013 meta-analysis of 26 RCTs with 8020 patients evaluated topical treatments for scalp psoriasis as part of a subanalysis of a larger Cochrane review of psoriasis therapy.1 Only 20 studies reported the severity of disease: 13 studies looked at moderate to severe scalp psoriasis and the others examined mild to severe disease.

Results were reported as standardized mean differences (SMD) and also converted to a 6-point global improvement scale created by the authors to provide a combined endpoint of provider- or patient-assessed improvement in symptoms such as redness, thickness, and scaling. Higher scores indicate more improvement.

Compared with placebo, the very potent corticosteroid clobetasol propionate improved psoriasis by 1.9 points on the 6-point scale (4 trials, 788 patients; SMD= −1.6; 95% confidence interval [CI], −1.8 to −1.3). The potent steroid betamethasone diproprionate improved symptoms by 1.3 points compared with placebo (2 trials, 712 patients; SMD= −1.1; 95% CI, −1.3 to −0.90).

The topical corticosteroids clobetasol, betamethasone diproprionate, and betamethasone valerate improved symptoms more than the vitamin D3 analogue calcipotriol in head-to-head trials. The corticosteroid improvement scores exceeded calcipotriol scores by 0.5 points (1 trial, 151 patients; SMD=0.37; 95% CI, 0.05-0.69), 0.6 points (1 trial, 1676 patients; SMD=0.48; 95% CI, 0.32-0.64), and 0.5 points (1 trial, 510 patients; SMD=0.37; 95% CI, 0.20-0.55), respectively.

Combination therapy with a vitamin D3 analogue and a corticosteroid yielded approximately 0.2 points of improvement over corticosteroid alone (6 trials, 2444 patients; SMD= −0.18; 95% CI, −0.26 to −0.10). Four trials of combination therapy (2581 patients) resulted in 0.5 to 1.2 points of improvement compared with vitamin D3 analogues alone (SMD=0.64; 95% CI, 0.44-0.84). Specific strengths and dosing regimens weren’t reported.

The Cochrane systematic review, using the same outcome reporting methods, provided data on the vitamin D3 analogue calcipotriol compared with placebo for treating scalp psoriasis.2 Calcipotriol resulted in 0.9 points of improvement on the 6-point global improvement scale (2 trials, 457 patients; SMD= −0.72; 95% CI, −1.3 to −0.16).

Very potent corticosteroids show a better response than potent agents

In 2013, a meta-analysis of 13 placebo-controlled RCTs (5640 patients) evaluated topical therapies for scalp psoriasis licensed in the United Kingdom. This meta-analysis included the same placebo-controlled studies as the Cochrane review but added one study published after the search date of the review.3

The outcome reporting was different from the Cochrane review. The primary outcome was percentage of patients with at least moderate scalp psoriasis who achieved clear or nearly clear status on provider assessment scales. All treatments were compared to twice-daily placebo with a response rate of 11%.

Very potent steroids had response rates of 78% for twice-daily application (risk ratio [RR]=7.0; 95% CI, 5.6-8.0) and 69% for once-daily application (RR=6.2; 95% CI, 3.0-8.3). The combination of a vitamin D3 analogue and a potent corticosteroid showed a response rate of 64% (RR=5.7; 95% CI, 2.4-8.0) whereas response rates for potent corticosteroids alone were 57% (RR=5.0; 95% CI, 1.6-7.8) for once-daily application and 49% (RR=4.4; 95% CI, 2.2-6.7) for twice-daily administration. The authors suggested patient satisfaction at using once daily vs twice daily application as a possible explanation for the difference in response rate.

Vitamin D3 analogues showed response rates of approximately 34%, which is nonsignificant for once-daily application (RR=3.1; 95% CI, 0.71-6.6) but significant for twice-daily administration (RR=3.1; 95% CI, 1.3-5.9). Exact numbers of studies and participants, as well as specific agents and preparation information, were not included.

1. Mason AR, Mason JM, Cork MJ, et al. Topical treatments for chronic plaque psoriasis of the scalp: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:519-527.

2. Mason A, Mason J, Cork M, et al. Topical treatments for chronic plaque psoriasis: an abridged Cochrane systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013; 69:799-807.

3. Samarasekera EJ, Sawyer L, Wonderling D, et al. Topical therapies for the treatment of plaque psoriasis: systematic review and network meta-analyses. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:954-967.

1. Mason AR, Mason JM, Cork MJ, et al. Topical treatments for chronic plaque psoriasis of the scalp: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:519-527.

2. Mason A, Mason J, Cork M, et al. Topical treatments for chronic plaque psoriasis: an abridged Cochrane systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013; 69:799-807.

3. Samarasekera EJ, Sawyer L, Wonderling D, et al. Topical therapies for the treatment of plaque psoriasis: systematic review and network meta-analyses. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:954-967.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

What Are the Benefits and Risks of Inhaled Corticosteroids for COPD?

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), either alone or with a long-acting β agonist (LABA), reduce the frequency of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and statistically, but not clinically, improve quality of life (QOL) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, meta-analyses of heterogeneous studies).

However, ICS have no mortality benefit and don’t consistently improve forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes). They increase the risk of pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes).

Withdrawal of ICS doesn’t significantly increase the risk of COPD exacerbation (SOR: B, a meta-analysis).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A Cochrane meta-analysis designed to determine the efficacy of ICS in patients with stable COPD found 55 randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) with a total of 16,154 participants that compared ICS with placebo for 2 weeks to 3 years duration.1 COPD varied from moderate to severe in most studies.

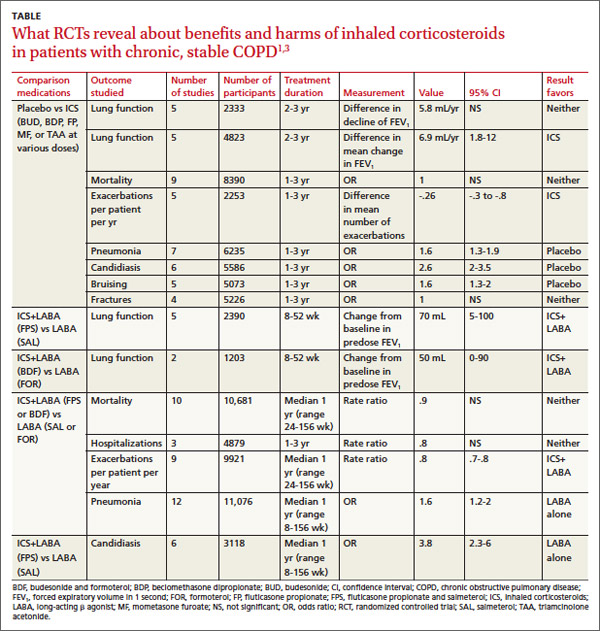

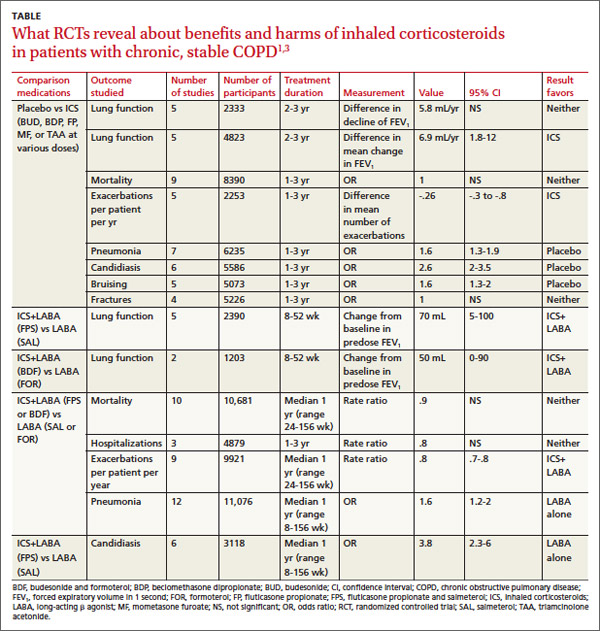

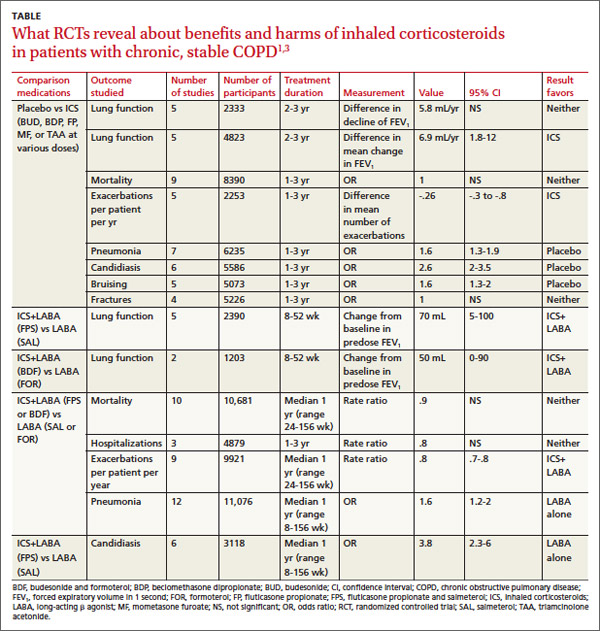

In pooled data, ICS for 2 or more years didn’t consistently improve lung function, the primary outcome (TABLE). However, the largest RCT (N=2617) of 3 years duration showed a small decrease in decline of FEV1 (55 mL compared with 42 mL, P value not provided). Regarding the secondary outcomes of mortality and exacerbations, ICS for a year or longer didn’t reduce mortality but decreased exacerbations by 19%.

Clinically significant adverse effects of ICS use included pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising; for ICS treatment longer than one year, the numbers needed to harm (NNH) compared with placebo were 30, 27, and 32, respectively. Bone fractures weren’t more common among ICS users. Investigators observed a statistical, but not clinical, QOL benefit as measured by the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) in 5 RCTs with a total of 2507 patients (mean difference, ‒1.22 units/year; 95% confidence interval, ‒1.83 to ‒.60). The minimum clinically important difference on the 76-item questionnaire was 4 units.2

Adding ICS to LABA increases risk of pneumonia and candidiasis

A Cochrane meta-analysis of 14 double-blind RCTs comprising a total of 11,794 participants with severe COPD compared LABA plus ICS with LABA alone over 8 weeks to 3 years.3 Primary outcomes were exacerbations, mortality, hospitalizations, and pneumonia. Secondary outcomes included oropharyngeal candidiasis and health-related QOL.

The LABA-plus-ICS group had lower rates of exacerbations than the LABA group, but the data were of low quality because of significant heterogeneity among studies and high rates of attrition. No significant difference in mortality or hospitalizations was found between the groups. The risk of pneumonia in the LABA-plus-ICS group was higher than in the LABA-alone group, with a NNH of 48.

Candidiasis occurred more often in patients on combination fluticasone and salmeterol than salmeterol alone, with a NNH of 22. QOL scores (measured by the SGRQ) in patients on combination therapy were statistically better, but clinically insignificant.

Discontinuing ICS doesn’t increase exacerbations

A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs that enrolled a total of 877 patients with COPD compared the number of exacerbations in patients who continued fluticasone 500 mcg inhaled twice daily and patients who were withdrawn from the medication. All patients had been treated with ICS for at least 3 months, and had been on fluticasone for at least 2 weeks. Subjects had a baseline FEV1 between 25% and 80% predicted. No significant increase in exacerbations occurred after discontinuing ICS.4

Recommendations

The American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society, in a joint guideline, recommend against using ICS as monotherapy for patients with stable COPD. They acknowledge that these drugs are superior to placebo in reducing exacerbations, but note that concerns about their side-effect profile (thrush, potential for bone loss, and moderate to severe easy bruisability) make them less desirable than LABAs or long-acting inhaled anticholinergics.5

The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease likewise discourages long-term use of ICS because of the risk of pneumonia and fractures.6 Both groups note that patients with severe COPD may benefit from a combination of ICS and a long-acting medication (usually a LABA).

1. Yang IA, Clarke MS, Sim EH, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(7):CD002991.

2. Jones PW. St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire: MCID. COPD. 2005;2:75-79.

3. Nannini LJ, Lasserson TJ, Poole P. Combined corticosteroid and long-acting beta(2)-agonist in one inhaler versus long-acting beta(2)-agonists for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9:CD006829.

4. Nadeem NJ, Taylor SJ, Eldridge SM. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids in individuals with COPD—a systemic review and comment on trial methodology. Respir Res. 2011;12:107.

5. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE, et al; American College of Physicians; American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:179-191.

6. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Web site. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD. 2014. Available at: www.goldcopd.org/uploads/users/files/GOLD_Report2014_Feb07.pdf. Accessed April 4, 2013.

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), either alone or with a long-acting β agonist (LABA), reduce the frequency of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and statistically, but not clinically, improve quality of life (QOL) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, meta-analyses of heterogeneous studies).

However, ICS have no mortality benefit and don’t consistently improve forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes). They increase the risk of pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes).

Withdrawal of ICS doesn’t significantly increase the risk of COPD exacerbation (SOR: B, a meta-analysis).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A Cochrane meta-analysis designed to determine the efficacy of ICS in patients with stable COPD found 55 randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) with a total of 16,154 participants that compared ICS with placebo for 2 weeks to 3 years duration.1 COPD varied from moderate to severe in most studies.

In pooled data, ICS for 2 or more years didn’t consistently improve lung function, the primary outcome (TABLE). However, the largest RCT (N=2617) of 3 years duration showed a small decrease in decline of FEV1 (55 mL compared with 42 mL, P value not provided). Regarding the secondary outcomes of mortality and exacerbations, ICS for a year or longer didn’t reduce mortality but decreased exacerbations by 19%.

Clinically significant adverse effects of ICS use included pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising; for ICS treatment longer than one year, the numbers needed to harm (NNH) compared with placebo were 30, 27, and 32, respectively. Bone fractures weren’t more common among ICS users. Investigators observed a statistical, but not clinical, QOL benefit as measured by the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) in 5 RCTs with a total of 2507 patients (mean difference, ‒1.22 units/year; 95% confidence interval, ‒1.83 to ‒.60). The minimum clinically important difference on the 76-item questionnaire was 4 units.2

Adding ICS to LABA increases risk of pneumonia and candidiasis

A Cochrane meta-analysis of 14 double-blind RCTs comprising a total of 11,794 participants with severe COPD compared LABA plus ICS with LABA alone over 8 weeks to 3 years.3 Primary outcomes were exacerbations, mortality, hospitalizations, and pneumonia. Secondary outcomes included oropharyngeal candidiasis and health-related QOL.

The LABA-plus-ICS group had lower rates of exacerbations than the LABA group, but the data were of low quality because of significant heterogeneity among studies and high rates of attrition. No significant difference in mortality or hospitalizations was found between the groups. The risk of pneumonia in the LABA-plus-ICS group was higher than in the LABA-alone group, with a NNH of 48.

Candidiasis occurred more often in patients on combination fluticasone and salmeterol than salmeterol alone, with a NNH of 22. QOL scores (measured by the SGRQ) in patients on combination therapy were statistically better, but clinically insignificant.

Discontinuing ICS doesn’t increase exacerbations

A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs that enrolled a total of 877 patients with COPD compared the number of exacerbations in patients who continued fluticasone 500 mcg inhaled twice daily and patients who were withdrawn from the medication. All patients had been treated with ICS for at least 3 months, and had been on fluticasone for at least 2 weeks. Subjects had a baseline FEV1 between 25% and 80% predicted. No significant increase in exacerbations occurred after discontinuing ICS.4

Recommendations

The American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society, in a joint guideline, recommend against using ICS as monotherapy for patients with stable COPD. They acknowledge that these drugs are superior to placebo in reducing exacerbations, but note that concerns about their side-effect profile (thrush, potential for bone loss, and moderate to severe easy bruisability) make them less desirable than LABAs or long-acting inhaled anticholinergics.5

The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease likewise discourages long-term use of ICS because of the risk of pneumonia and fractures.6 Both groups note that patients with severe COPD may benefit from a combination of ICS and a long-acting medication (usually a LABA).

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), either alone or with a long-acting β agonist (LABA), reduce the frequency of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and statistically, but not clinically, improve quality of life (QOL) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, meta-analyses of heterogeneous studies).

However, ICS have no mortality benefit and don’t consistently improve forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes). They increase the risk of pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes).

Withdrawal of ICS doesn’t significantly increase the risk of COPD exacerbation (SOR: B, a meta-analysis).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A Cochrane meta-analysis designed to determine the efficacy of ICS in patients with stable COPD found 55 randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) with a total of 16,154 participants that compared ICS with placebo for 2 weeks to 3 years duration.1 COPD varied from moderate to severe in most studies.

In pooled data, ICS for 2 or more years didn’t consistently improve lung function, the primary outcome (TABLE). However, the largest RCT (N=2617) of 3 years duration showed a small decrease in decline of FEV1 (55 mL compared with 42 mL, P value not provided). Regarding the secondary outcomes of mortality and exacerbations, ICS for a year or longer didn’t reduce mortality but decreased exacerbations by 19%.

Clinically significant adverse effects of ICS use included pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising; for ICS treatment longer than one year, the numbers needed to harm (NNH) compared with placebo were 30, 27, and 32, respectively. Bone fractures weren’t more common among ICS users. Investigators observed a statistical, but not clinical, QOL benefit as measured by the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) in 5 RCTs with a total of 2507 patients (mean difference, ‒1.22 units/year; 95% confidence interval, ‒1.83 to ‒.60). The minimum clinically important difference on the 76-item questionnaire was 4 units.2

Adding ICS to LABA increases risk of pneumonia and candidiasis

A Cochrane meta-analysis of 14 double-blind RCTs comprising a total of 11,794 participants with severe COPD compared LABA plus ICS with LABA alone over 8 weeks to 3 years.3 Primary outcomes were exacerbations, mortality, hospitalizations, and pneumonia. Secondary outcomes included oropharyngeal candidiasis and health-related QOL.

The LABA-plus-ICS group had lower rates of exacerbations than the LABA group, but the data were of low quality because of significant heterogeneity among studies and high rates of attrition. No significant difference in mortality or hospitalizations was found between the groups. The risk of pneumonia in the LABA-plus-ICS group was higher than in the LABA-alone group, with a NNH of 48.

Candidiasis occurred more often in patients on combination fluticasone and salmeterol than salmeterol alone, with a NNH of 22. QOL scores (measured by the SGRQ) in patients on combination therapy were statistically better, but clinically insignificant.

Discontinuing ICS doesn’t increase exacerbations

A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs that enrolled a total of 877 patients with COPD compared the number of exacerbations in patients who continued fluticasone 500 mcg inhaled twice daily and patients who were withdrawn from the medication. All patients had been treated with ICS for at least 3 months, and had been on fluticasone for at least 2 weeks. Subjects had a baseline FEV1 between 25% and 80% predicted. No significant increase in exacerbations occurred after discontinuing ICS.4

Recommendations

The American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society, in a joint guideline, recommend against using ICS as monotherapy for patients with stable COPD. They acknowledge that these drugs are superior to placebo in reducing exacerbations, but note that concerns about their side-effect profile (thrush, potential for bone loss, and moderate to severe easy bruisability) make them less desirable than LABAs or long-acting inhaled anticholinergics.5

The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease likewise discourages long-term use of ICS because of the risk of pneumonia and fractures.6 Both groups note that patients with severe COPD may benefit from a combination of ICS and a long-acting medication (usually a LABA).

1. Yang IA, Clarke MS, Sim EH, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(7):CD002991.

2. Jones PW. St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire: MCID. COPD. 2005;2:75-79.

3. Nannini LJ, Lasserson TJ, Poole P. Combined corticosteroid and long-acting beta(2)-agonist in one inhaler versus long-acting beta(2)-agonists for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9:CD006829.

4. Nadeem NJ, Taylor SJ, Eldridge SM. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids in individuals with COPD—a systemic review and comment on trial methodology. Respir Res. 2011;12:107.

5. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE, et al; American College of Physicians; American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:179-191.

6. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Web site. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD. 2014. Available at: www.goldcopd.org/uploads/users/files/GOLD_Report2014_Feb07.pdf. Accessed April 4, 2013.

1. Yang IA, Clarke MS, Sim EH, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(7):CD002991.

2. Jones PW. St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire: MCID. COPD. 2005;2:75-79.

3. Nannini LJ, Lasserson TJ, Poole P. Combined corticosteroid and long-acting beta(2)-agonist in one inhaler versus long-acting beta(2)-agonists for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9:CD006829.

4. Nadeem NJ, Taylor SJ, Eldridge SM. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids in individuals with COPD—a systemic review and comment on trial methodology. Respir Res. 2011;12:107.

5. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE, et al; American College of Physicians; American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:179-191.

6. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Web site. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD. 2014. Available at: www.goldcopd.org/uploads/users/files/GOLD_Report2014_Feb07.pdf. Accessed April 4, 2013.

What are the benefits and risks of inhaled corticosteroids for COPD?

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), either alone or with a long-acting β agonist (LABA), reduce the frequency of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and statistically, but not clinically, improve quality of life (QOL) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, meta-analyses of heterogeneous studies).

However, ICS have no mortality benefit and don’t consistently improve forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes). They increase the risk of pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes).

Withdrawal of ICS doesn’t significantly increase the risk of COPD exacerbation (SOR: B, a meta-analysis).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A Cochrane meta-analysis designed to determine the efficacy of ICS in patients with stable COPD found 55 randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) with a total of 16,154 participants that compared ICS with placebo for 2 weeks to 3 years duration.1 COPD varied from moderate to severe in most studies.

In pooled data, ICS for 2 or more years didn’t consistently improve lung function, the primary outcome (TABLE). However, the largest RCT (N=2617) of 3 years duration showed a small decrease in decline of FEV1 (55 mL compared with 42 mL, P value not provided). Regarding the secondary outcomes of mortality and exacerbations, ICS for a year or longer didn’t reduce mortality but decreased exacerbations by 19%.

Clinically significant adverse effects of ICS use included pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising; for ICS treatment longer than one year, the numbers needed to harm (NNH) compared with placebo were 30, 27, and 32, respectively. Bone fractures weren’t more common among ICS users. Investigators observed a statistical, but not clinical, QOL benefit as measured by the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) in 5 RCTs with a total of 2507 patients (mean difference, ‒1.22 units/year; 95% confidence interval, ‒1.83 to ‒.60). The minimum clinically important difference on the 76-item questionnaire was 4 units.2

Adding ICS to LABA increases risk of pneumonia and candidiasis

A Cochrane meta-analysis of 14 double-blind RCTs comprising a total of 11,794 participants with severe COPD compared LABA plus ICS with LABA alone over 8 weeks to 3 years.3 Primary outcomes were exacerbations, mortality, hospitalizations, and pneumonia. Secondary outcomes included oropharyngeal candidiasis and health-related QOL.

The LABA-plus-ICS group had lower rates of exacerbations than the LABA group, but the data were of low quality because of significant heterogeneity among studies and high rates of attrition. No significant difference in mortality or hospitalizations was found between the groups. The risk of pneumonia in the LABA-plus-ICS group was higher than in the LABA-alone group, with a NNH of 48.

Candidiasis occurred more often in patients on combination fluticasone and salmeterol than salmeterol alone, with a NNH of 22. QOL scores (measured by the SGRQ) in patients on combination therapy were statistically better, but clinically insignificant.

Discontinuing ICS doesn’t increase exacerbations

A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs that enrolled a total of 877 patients with COPD compared the number of exacerbations in patients who continued fluticasone 500 mcg inhaled twice daily and patients who were withdrawn from the medication. All patients had been treated with ICS for at least 3 months, and had been on fluticasone for at least 2 weeks. Subjects had a baseline FEV1 between 25% and 80% predicted. No significant increase in exacerbations occurred after discontinuing ICS.4

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society, in a joint guideline, recommend against using ICS as monotherapy for patients with stable COPD. They acknowledge that these drugs are superior to placebo in reducing exacerbations, but note that concerns about their side-effect profile (thrush, potential for bone loss, and moderate to severe easy bruisability) make them less desirable than LABAs or long-acting inhaled anticholinergics.5

The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease likewise discourages long-term use of ICS because of the risk of pneumonia and fractures.6 Both groups note that patients with severe COPD may benefit from a combination of ICS and a long-acting medication (usually a LABA).

1. Yang IA, Clarke MS, Sim EH, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(7):CD002991.

2. Jones PW. St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire: MCID. COPD. 2005;2:75-79.

3. Nannini LJ, Lasserson TJ, Poole P. Combined corticosteroid and long-acting beta(2)-agonist in one inhaler versus long-acting beta(2)-agonists for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9:CD006829.

4. Nadeem NJ, Taylor SJ, Eldridge SM. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids in individuals with COPD—a systemic review and comment on trial methodology. Respir Res. 2011;12:107.

5. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE, et al; American College of Physicians; American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:179-191.

6. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Web site. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD. 2014. Available at: www.goldcopd.org/uploads/users/files/GOLD_Report2014_Feb07.pdf. Accessed April 4, 2013.

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), either alone or with a long-acting β agonist (LABA), reduce the frequency of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and statistically, but not clinically, improve quality of life (QOL) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, meta-analyses of heterogeneous studies).

However, ICS have no mortality benefit and don’t consistently improve forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes). They increase the risk of pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes).

Withdrawal of ICS doesn’t significantly increase the risk of COPD exacerbation (SOR: B, a meta-analysis).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A Cochrane meta-analysis designed to determine the efficacy of ICS in patients with stable COPD found 55 randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) with a total of 16,154 participants that compared ICS with placebo for 2 weeks to 3 years duration.1 COPD varied from moderate to severe in most studies.

In pooled data, ICS for 2 or more years didn’t consistently improve lung function, the primary outcome (TABLE). However, the largest RCT (N=2617) of 3 years duration showed a small decrease in decline of FEV1 (55 mL compared with 42 mL, P value not provided). Regarding the secondary outcomes of mortality and exacerbations, ICS for a year or longer didn’t reduce mortality but decreased exacerbations by 19%.

Clinically significant adverse effects of ICS use included pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising; for ICS treatment longer than one year, the numbers needed to harm (NNH) compared with placebo were 30, 27, and 32, respectively. Bone fractures weren’t more common among ICS users. Investigators observed a statistical, but not clinical, QOL benefit as measured by the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) in 5 RCTs with a total of 2507 patients (mean difference, ‒1.22 units/year; 95% confidence interval, ‒1.83 to ‒.60). The minimum clinically important difference on the 76-item questionnaire was 4 units.2

Adding ICS to LABA increases risk of pneumonia and candidiasis

A Cochrane meta-analysis of 14 double-blind RCTs comprising a total of 11,794 participants with severe COPD compared LABA plus ICS with LABA alone over 8 weeks to 3 years.3 Primary outcomes were exacerbations, mortality, hospitalizations, and pneumonia. Secondary outcomes included oropharyngeal candidiasis and health-related QOL.

The LABA-plus-ICS group had lower rates of exacerbations than the LABA group, but the data were of low quality because of significant heterogeneity among studies and high rates of attrition. No significant difference in mortality or hospitalizations was found between the groups. The risk of pneumonia in the LABA-plus-ICS group was higher than in the LABA-alone group, with a NNH of 48.

Candidiasis occurred more often in patients on combination fluticasone and salmeterol than salmeterol alone, with a NNH of 22. QOL scores (measured by the SGRQ) in patients on combination therapy were statistically better, but clinically insignificant.

Discontinuing ICS doesn’t increase exacerbations

A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs that enrolled a total of 877 patients with COPD compared the number of exacerbations in patients who continued fluticasone 500 mcg inhaled twice daily and patients who were withdrawn from the medication. All patients had been treated with ICS for at least 3 months, and had been on fluticasone for at least 2 weeks. Subjects had a baseline FEV1 between 25% and 80% predicted. No significant increase in exacerbations occurred after discontinuing ICS.4

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society, in a joint guideline, recommend against using ICS as monotherapy for patients with stable COPD. They acknowledge that these drugs are superior to placebo in reducing exacerbations, but note that concerns about their side-effect profile (thrush, potential for bone loss, and moderate to severe easy bruisability) make them less desirable than LABAs or long-acting inhaled anticholinergics.5

The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease likewise discourages long-term use of ICS because of the risk of pneumonia and fractures.6 Both groups note that patients with severe COPD may benefit from a combination of ICS and a long-acting medication (usually a LABA).

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), either alone or with a long-acting β agonist (LABA), reduce the frequency of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and statistically, but not clinically, improve quality of life (QOL) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, meta-analyses of heterogeneous studies).

However, ICS have no mortality benefit and don’t consistently improve forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes). They increase the risk of pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes).

Withdrawal of ICS doesn’t significantly increase the risk of COPD exacerbation (SOR: B, a meta-analysis).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A Cochrane meta-analysis designed to determine the efficacy of ICS in patients with stable COPD found 55 randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) with a total of 16,154 participants that compared ICS with placebo for 2 weeks to 3 years duration.1 COPD varied from moderate to severe in most studies.

In pooled data, ICS for 2 or more years didn’t consistently improve lung function, the primary outcome (TABLE). However, the largest RCT (N=2617) of 3 years duration showed a small decrease in decline of FEV1 (55 mL compared with 42 mL, P value not provided). Regarding the secondary outcomes of mortality and exacerbations, ICS for a year or longer didn’t reduce mortality but decreased exacerbations by 19%.

Clinically significant adverse effects of ICS use included pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising; for ICS treatment longer than one year, the numbers needed to harm (NNH) compared with placebo were 30, 27, and 32, respectively. Bone fractures weren’t more common among ICS users. Investigators observed a statistical, but not clinical, QOL benefit as measured by the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) in 5 RCTs with a total of 2507 patients (mean difference, ‒1.22 units/year; 95% confidence interval, ‒1.83 to ‒.60). The minimum clinically important difference on the 76-item questionnaire was 4 units.2

Adding ICS to LABA increases risk of pneumonia and candidiasis

A Cochrane meta-analysis of 14 double-blind RCTs comprising a total of 11,794 participants with severe COPD compared LABA plus ICS with LABA alone over 8 weeks to 3 years.3 Primary outcomes were exacerbations, mortality, hospitalizations, and pneumonia. Secondary outcomes included oropharyngeal candidiasis and health-related QOL.

The LABA-plus-ICS group had lower rates of exacerbations than the LABA group, but the data were of low quality because of significant heterogeneity among studies and high rates of attrition. No significant difference in mortality or hospitalizations was found between the groups. The risk of pneumonia in the LABA-plus-ICS group was higher than in the LABA-alone group, with a NNH of 48.

Candidiasis occurred more often in patients on combination fluticasone and salmeterol than salmeterol alone, with a NNH of 22. QOL scores (measured by the SGRQ) in patients on combination therapy were statistically better, but clinically insignificant.

Discontinuing ICS doesn’t increase exacerbations

A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs that enrolled a total of 877 patients with COPD compared the number of exacerbations in patients who continued fluticasone 500 mcg inhaled twice daily and patients who were withdrawn from the medication. All patients had been treated with ICS for at least 3 months, and had been on fluticasone for at least 2 weeks. Subjects had a baseline FEV1 between 25% and 80% predicted. No significant increase in exacerbations occurred after discontinuing ICS.4

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society, in a joint guideline, recommend against using ICS as monotherapy for patients with stable COPD. They acknowledge that these drugs are superior to placebo in reducing exacerbations, but note that concerns about their side-effect profile (thrush, potential for bone loss, and moderate to severe easy bruisability) make them less desirable than LABAs or long-acting inhaled anticholinergics.5

The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease likewise discourages long-term use of ICS because of the risk of pneumonia and fractures.6 Both groups note that patients with severe COPD may benefit from a combination of ICS and a long-acting medication (usually a LABA).

1. Yang IA, Clarke MS, Sim EH, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(7):CD002991.

2. Jones PW. St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire: MCID. COPD. 2005;2:75-79.

3. Nannini LJ, Lasserson TJ, Poole P. Combined corticosteroid and long-acting beta(2)-agonist in one inhaler versus long-acting beta(2)-agonists for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9:CD006829.

4. Nadeem NJ, Taylor SJ, Eldridge SM. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids in individuals with COPD—a systemic review and comment on trial methodology. Respir Res. 2011;12:107.

5. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE, et al; American College of Physicians; American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:179-191.

6. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Web site. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD. 2014. Available at: www.goldcopd.org/uploads/users/files/GOLD_Report2014_Feb07.pdf. Accessed April 4, 2013.

1. Yang IA, Clarke MS, Sim EH, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(7):CD002991.

2. Jones PW. St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire: MCID. COPD. 2005;2:75-79.

3. Nannini LJ, Lasserson TJ, Poole P. Combined corticosteroid and long-acting beta(2)-agonist in one inhaler versus long-acting beta(2)-agonists for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9:CD006829.

4. Nadeem NJ, Taylor SJ, Eldridge SM. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids in individuals with COPD—a systemic review and comment on trial methodology. Respir Res. 2011;12:107.

5. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE, et al; American College of Physicians; American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:179-191.

6. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Web site. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD. 2014. Available at: www.goldcopd.org/uploads/users/files/GOLD_Report2014_Feb07.pdf. Accessed April 4, 2013.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network