User login

What Are the Benefits and Risks of Inhaled Corticosteroids for COPD?

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), either alone or with a long-acting β agonist (LABA), reduce the frequency of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and statistically, but not clinically, improve quality of life (QOL) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, meta-analyses of heterogeneous studies).

However, ICS have no mortality benefit and don’t consistently improve forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes). They increase the risk of pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes).

Withdrawal of ICS doesn’t significantly increase the risk of COPD exacerbation (SOR: B, a meta-analysis).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A Cochrane meta-analysis designed to determine the efficacy of ICS in patients with stable COPD found 55 randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) with a total of 16,154 participants that compared ICS with placebo for 2 weeks to 3 years duration.1 COPD varied from moderate to severe in most studies.

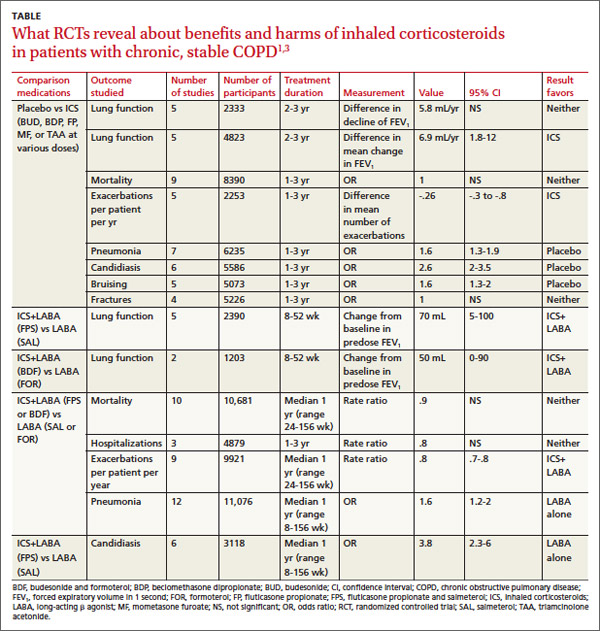

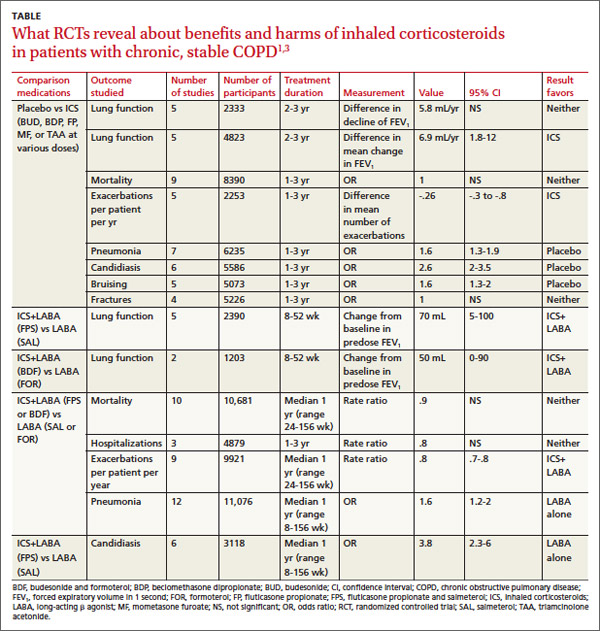

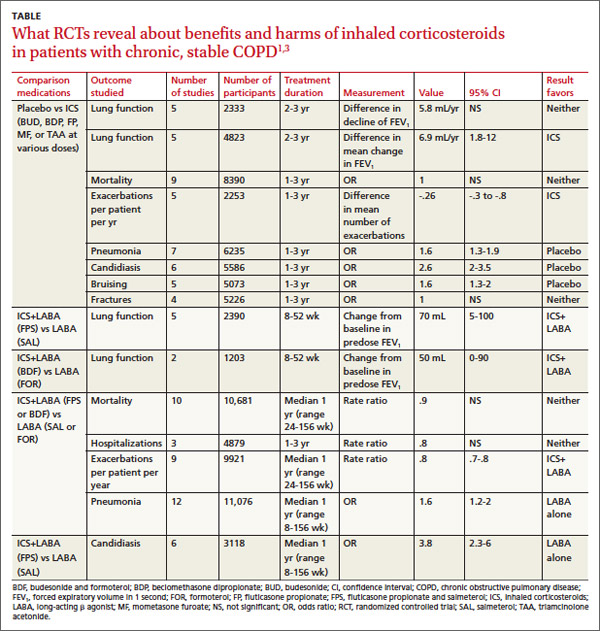

In pooled data, ICS for 2 or more years didn’t consistently improve lung function, the primary outcome (TABLE). However, the largest RCT (N=2617) of 3 years duration showed a small decrease in decline of FEV1 (55 mL compared with 42 mL, P value not provided). Regarding the secondary outcomes of mortality and exacerbations, ICS for a year or longer didn’t reduce mortality but decreased exacerbations by 19%.

Clinically significant adverse effects of ICS use included pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising; for ICS treatment longer than one year, the numbers needed to harm (NNH) compared with placebo were 30, 27, and 32, respectively. Bone fractures weren’t more common among ICS users. Investigators observed a statistical, but not clinical, QOL benefit as measured by the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) in 5 RCTs with a total of 2507 patients (mean difference, ‒1.22 units/year; 95% confidence interval, ‒1.83 to ‒.60). The minimum clinically important difference on the 76-item questionnaire was 4 units.2

Adding ICS to LABA increases risk of pneumonia and candidiasis

A Cochrane meta-analysis of 14 double-blind RCTs comprising a total of 11,794 participants with severe COPD compared LABA plus ICS with LABA alone over 8 weeks to 3 years.3 Primary outcomes were exacerbations, mortality, hospitalizations, and pneumonia. Secondary outcomes included oropharyngeal candidiasis and health-related QOL.

The LABA-plus-ICS group had lower rates of exacerbations than the LABA group, but the data were of low quality because of significant heterogeneity among studies and high rates of attrition. No significant difference in mortality or hospitalizations was found between the groups. The risk of pneumonia in the LABA-plus-ICS group was higher than in the LABA-alone group, with a NNH of 48.

Candidiasis occurred more often in patients on combination fluticasone and salmeterol than salmeterol alone, with a NNH of 22. QOL scores (measured by the SGRQ) in patients on combination therapy were statistically better, but clinically insignificant.

Discontinuing ICS doesn’t increase exacerbations

A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs that enrolled a total of 877 patients with COPD compared the number of exacerbations in patients who continued fluticasone 500 mcg inhaled twice daily and patients who were withdrawn from the medication. All patients had been treated with ICS for at least 3 months, and had been on fluticasone for at least 2 weeks. Subjects had a baseline FEV1 between 25% and 80% predicted. No significant increase in exacerbations occurred after discontinuing ICS.4

Recommendations

The American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society, in a joint guideline, recommend against using ICS as monotherapy for patients with stable COPD. They acknowledge that these drugs are superior to placebo in reducing exacerbations, but note that concerns about their side-effect profile (thrush, potential for bone loss, and moderate to severe easy bruisability) make them less desirable than LABAs or long-acting inhaled anticholinergics.5

The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease likewise discourages long-term use of ICS because of the risk of pneumonia and fractures.6 Both groups note that patients with severe COPD may benefit from a combination of ICS and a long-acting medication (usually a LABA).

1. Yang IA, Clarke MS, Sim EH, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(7):CD002991.

2. Jones PW. St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire: MCID. COPD. 2005;2:75-79.

3. Nannini LJ, Lasserson TJ, Poole P. Combined corticosteroid and long-acting beta(2)-agonist in one inhaler versus long-acting beta(2)-agonists for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9:CD006829.

4. Nadeem NJ, Taylor SJ, Eldridge SM. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids in individuals with COPD—a systemic review and comment on trial methodology. Respir Res. 2011;12:107.

5. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE, et al; American College of Physicians; American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:179-191.

6. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Web site. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD. 2014. Available at: www.goldcopd.org/uploads/users/files/GOLD_Report2014_Feb07.pdf. Accessed April 4, 2013.

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), either alone or with a long-acting β agonist (LABA), reduce the frequency of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and statistically, but not clinically, improve quality of life (QOL) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, meta-analyses of heterogeneous studies).

However, ICS have no mortality benefit and don’t consistently improve forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes). They increase the risk of pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes).

Withdrawal of ICS doesn’t significantly increase the risk of COPD exacerbation (SOR: B, a meta-analysis).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A Cochrane meta-analysis designed to determine the efficacy of ICS in patients with stable COPD found 55 randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) with a total of 16,154 participants that compared ICS with placebo for 2 weeks to 3 years duration.1 COPD varied from moderate to severe in most studies.

In pooled data, ICS for 2 or more years didn’t consistently improve lung function, the primary outcome (TABLE). However, the largest RCT (N=2617) of 3 years duration showed a small decrease in decline of FEV1 (55 mL compared with 42 mL, P value not provided). Regarding the secondary outcomes of mortality and exacerbations, ICS for a year or longer didn’t reduce mortality but decreased exacerbations by 19%.

Clinically significant adverse effects of ICS use included pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising; for ICS treatment longer than one year, the numbers needed to harm (NNH) compared with placebo were 30, 27, and 32, respectively. Bone fractures weren’t more common among ICS users. Investigators observed a statistical, but not clinical, QOL benefit as measured by the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) in 5 RCTs with a total of 2507 patients (mean difference, ‒1.22 units/year; 95% confidence interval, ‒1.83 to ‒.60). The minimum clinically important difference on the 76-item questionnaire was 4 units.2

Adding ICS to LABA increases risk of pneumonia and candidiasis

A Cochrane meta-analysis of 14 double-blind RCTs comprising a total of 11,794 participants with severe COPD compared LABA plus ICS with LABA alone over 8 weeks to 3 years.3 Primary outcomes were exacerbations, mortality, hospitalizations, and pneumonia. Secondary outcomes included oropharyngeal candidiasis and health-related QOL.

The LABA-plus-ICS group had lower rates of exacerbations than the LABA group, but the data were of low quality because of significant heterogeneity among studies and high rates of attrition. No significant difference in mortality or hospitalizations was found between the groups. The risk of pneumonia in the LABA-plus-ICS group was higher than in the LABA-alone group, with a NNH of 48.

Candidiasis occurred more often in patients on combination fluticasone and salmeterol than salmeterol alone, with a NNH of 22. QOL scores (measured by the SGRQ) in patients on combination therapy were statistically better, but clinically insignificant.

Discontinuing ICS doesn’t increase exacerbations

A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs that enrolled a total of 877 patients with COPD compared the number of exacerbations in patients who continued fluticasone 500 mcg inhaled twice daily and patients who were withdrawn from the medication. All patients had been treated with ICS for at least 3 months, and had been on fluticasone for at least 2 weeks. Subjects had a baseline FEV1 between 25% and 80% predicted. No significant increase in exacerbations occurred after discontinuing ICS.4

Recommendations

The American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society, in a joint guideline, recommend against using ICS as monotherapy for patients with stable COPD. They acknowledge that these drugs are superior to placebo in reducing exacerbations, but note that concerns about their side-effect profile (thrush, potential for bone loss, and moderate to severe easy bruisability) make them less desirable than LABAs or long-acting inhaled anticholinergics.5

The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease likewise discourages long-term use of ICS because of the risk of pneumonia and fractures.6 Both groups note that patients with severe COPD may benefit from a combination of ICS and a long-acting medication (usually a LABA).

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), either alone or with a long-acting β agonist (LABA), reduce the frequency of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and statistically, but not clinically, improve quality of life (QOL) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, meta-analyses of heterogeneous studies).

However, ICS have no mortality benefit and don’t consistently improve forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes). They increase the risk of pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes).

Withdrawal of ICS doesn’t significantly increase the risk of COPD exacerbation (SOR: B, a meta-analysis).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A Cochrane meta-analysis designed to determine the efficacy of ICS in patients with stable COPD found 55 randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) with a total of 16,154 participants that compared ICS with placebo for 2 weeks to 3 years duration.1 COPD varied from moderate to severe in most studies.

In pooled data, ICS for 2 or more years didn’t consistently improve lung function, the primary outcome (TABLE). However, the largest RCT (N=2617) of 3 years duration showed a small decrease in decline of FEV1 (55 mL compared with 42 mL, P value not provided). Regarding the secondary outcomes of mortality and exacerbations, ICS for a year or longer didn’t reduce mortality but decreased exacerbations by 19%.

Clinically significant adverse effects of ICS use included pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising; for ICS treatment longer than one year, the numbers needed to harm (NNH) compared with placebo were 30, 27, and 32, respectively. Bone fractures weren’t more common among ICS users. Investigators observed a statistical, but not clinical, QOL benefit as measured by the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) in 5 RCTs with a total of 2507 patients (mean difference, ‒1.22 units/year; 95% confidence interval, ‒1.83 to ‒.60). The minimum clinically important difference on the 76-item questionnaire was 4 units.2

Adding ICS to LABA increases risk of pneumonia and candidiasis

A Cochrane meta-analysis of 14 double-blind RCTs comprising a total of 11,794 participants with severe COPD compared LABA plus ICS with LABA alone over 8 weeks to 3 years.3 Primary outcomes were exacerbations, mortality, hospitalizations, and pneumonia. Secondary outcomes included oropharyngeal candidiasis and health-related QOL.

The LABA-plus-ICS group had lower rates of exacerbations than the LABA group, but the data were of low quality because of significant heterogeneity among studies and high rates of attrition. No significant difference in mortality or hospitalizations was found between the groups. The risk of pneumonia in the LABA-plus-ICS group was higher than in the LABA-alone group, with a NNH of 48.

Candidiasis occurred more often in patients on combination fluticasone and salmeterol than salmeterol alone, with a NNH of 22. QOL scores (measured by the SGRQ) in patients on combination therapy were statistically better, but clinically insignificant.

Discontinuing ICS doesn’t increase exacerbations

A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs that enrolled a total of 877 patients with COPD compared the number of exacerbations in patients who continued fluticasone 500 mcg inhaled twice daily and patients who were withdrawn from the medication. All patients had been treated with ICS for at least 3 months, and had been on fluticasone for at least 2 weeks. Subjects had a baseline FEV1 between 25% and 80% predicted. No significant increase in exacerbations occurred after discontinuing ICS.4

Recommendations

The American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society, in a joint guideline, recommend against using ICS as monotherapy for patients with stable COPD. They acknowledge that these drugs are superior to placebo in reducing exacerbations, but note that concerns about their side-effect profile (thrush, potential for bone loss, and moderate to severe easy bruisability) make them less desirable than LABAs or long-acting inhaled anticholinergics.5

The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease likewise discourages long-term use of ICS because of the risk of pneumonia and fractures.6 Both groups note that patients with severe COPD may benefit from a combination of ICS and a long-acting medication (usually a LABA).

1. Yang IA, Clarke MS, Sim EH, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(7):CD002991.

2. Jones PW. St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire: MCID. COPD. 2005;2:75-79.

3. Nannini LJ, Lasserson TJ, Poole P. Combined corticosteroid and long-acting beta(2)-agonist in one inhaler versus long-acting beta(2)-agonists for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9:CD006829.

4. Nadeem NJ, Taylor SJ, Eldridge SM. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids in individuals with COPD—a systemic review and comment on trial methodology. Respir Res. 2011;12:107.

5. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE, et al; American College of Physicians; American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:179-191.

6. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Web site. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD. 2014. Available at: www.goldcopd.org/uploads/users/files/GOLD_Report2014_Feb07.pdf. Accessed April 4, 2013.

1. Yang IA, Clarke MS, Sim EH, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(7):CD002991.

2. Jones PW. St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire: MCID. COPD. 2005;2:75-79.

3. Nannini LJ, Lasserson TJ, Poole P. Combined corticosteroid and long-acting beta(2)-agonist in one inhaler versus long-acting beta(2)-agonists for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9:CD006829.

4. Nadeem NJ, Taylor SJ, Eldridge SM. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids in individuals with COPD—a systemic review and comment on trial methodology. Respir Res. 2011;12:107.

5. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE, et al; American College of Physicians; American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:179-191.

6. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Web site. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD. 2014. Available at: www.goldcopd.org/uploads/users/files/GOLD_Report2014_Feb07.pdf. Accessed April 4, 2013.

What are the benefits and risks of inhaled corticosteroids for COPD?

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), either alone or with a long-acting β agonist (LABA), reduce the frequency of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and statistically, but not clinically, improve quality of life (QOL) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, meta-analyses of heterogeneous studies).

However, ICS have no mortality benefit and don’t consistently improve forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes). They increase the risk of pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes).

Withdrawal of ICS doesn’t significantly increase the risk of COPD exacerbation (SOR: B, a meta-analysis).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A Cochrane meta-analysis designed to determine the efficacy of ICS in patients with stable COPD found 55 randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) with a total of 16,154 participants that compared ICS with placebo for 2 weeks to 3 years duration.1 COPD varied from moderate to severe in most studies.

In pooled data, ICS for 2 or more years didn’t consistently improve lung function, the primary outcome (TABLE). However, the largest RCT (N=2617) of 3 years duration showed a small decrease in decline of FEV1 (55 mL compared with 42 mL, P value not provided). Regarding the secondary outcomes of mortality and exacerbations, ICS for a year or longer didn’t reduce mortality but decreased exacerbations by 19%.

Clinically significant adverse effects of ICS use included pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising; for ICS treatment longer than one year, the numbers needed to harm (NNH) compared with placebo were 30, 27, and 32, respectively. Bone fractures weren’t more common among ICS users. Investigators observed a statistical, but not clinical, QOL benefit as measured by the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) in 5 RCTs with a total of 2507 patients (mean difference, ‒1.22 units/year; 95% confidence interval, ‒1.83 to ‒.60). The minimum clinically important difference on the 76-item questionnaire was 4 units.2

Adding ICS to LABA increases risk of pneumonia and candidiasis

A Cochrane meta-analysis of 14 double-blind RCTs comprising a total of 11,794 participants with severe COPD compared LABA plus ICS with LABA alone over 8 weeks to 3 years.3 Primary outcomes were exacerbations, mortality, hospitalizations, and pneumonia. Secondary outcomes included oropharyngeal candidiasis and health-related QOL.

The LABA-plus-ICS group had lower rates of exacerbations than the LABA group, but the data were of low quality because of significant heterogeneity among studies and high rates of attrition. No significant difference in mortality or hospitalizations was found between the groups. The risk of pneumonia in the LABA-plus-ICS group was higher than in the LABA-alone group, with a NNH of 48.

Candidiasis occurred more often in patients on combination fluticasone and salmeterol than salmeterol alone, with a NNH of 22. QOL scores (measured by the SGRQ) in patients on combination therapy were statistically better, but clinically insignificant.

Discontinuing ICS doesn’t increase exacerbations

A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs that enrolled a total of 877 patients with COPD compared the number of exacerbations in patients who continued fluticasone 500 mcg inhaled twice daily and patients who were withdrawn from the medication. All patients had been treated with ICS for at least 3 months, and had been on fluticasone for at least 2 weeks. Subjects had a baseline FEV1 between 25% and 80% predicted. No significant increase in exacerbations occurred after discontinuing ICS.4

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society, in a joint guideline, recommend against using ICS as monotherapy for patients with stable COPD. They acknowledge that these drugs are superior to placebo in reducing exacerbations, but note that concerns about their side-effect profile (thrush, potential for bone loss, and moderate to severe easy bruisability) make them less desirable than LABAs or long-acting inhaled anticholinergics.5

The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease likewise discourages long-term use of ICS because of the risk of pneumonia and fractures.6 Both groups note that patients with severe COPD may benefit from a combination of ICS and a long-acting medication (usually a LABA).

1. Yang IA, Clarke MS, Sim EH, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(7):CD002991.

2. Jones PW. St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire: MCID. COPD. 2005;2:75-79.

3. Nannini LJ, Lasserson TJ, Poole P. Combined corticosteroid and long-acting beta(2)-agonist in one inhaler versus long-acting beta(2)-agonists for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9:CD006829.

4. Nadeem NJ, Taylor SJ, Eldridge SM. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids in individuals with COPD—a systemic review and comment on trial methodology. Respir Res. 2011;12:107.

5. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE, et al; American College of Physicians; American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:179-191.

6. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Web site. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD. 2014. Available at: www.goldcopd.org/uploads/users/files/GOLD_Report2014_Feb07.pdf. Accessed April 4, 2013.

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), either alone or with a long-acting β agonist (LABA), reduce the frequency of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and statistically, but not clinically, improve quality of life (QOL) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, meta-analyses of heterogeneous studies).

However, ICS have no mortality benefit and don’t consistently improve forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes). They increase the risk of pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes).

Withdrawal of ICS doesn’t significantly increase the risk of COPD exacerbation (SOR: B, a meta-analysis).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A Cochrane meta-analysis designed to determine the efficacy of ICS in patients with stable COPD found 55 randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) with a total of 16,154 participants that compared ICS with placebo for 2 weeks to 3 years duration.1 COPD varied from moderate to severe in most studies.

In pooled data, ICS for 2 or more years didn’t consistently improve lung function, the primary outcome (TABLE). However, the largest RCT (N=2617) of 3 years duration showed a small decrease in decline of FEV1 (55 mL compared with 42 mL, P value not provided). Regarding the secondary outcomes of mortality and exacerbations, ICS for a year or longer didn’t reduce mortality but decreased exacerbations by 19%.

Clinically significant adverse effects of ICS use included pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising; for ICS treatment longer than one year, the numbers needed to harm (NNH) compared with placebo were 30, 27, and 32, respectively. Bone fractures weren’t more common among ICS users. Investigators observed a statistical, but not clinical, QOL benefit as measured by the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) in 5 RCTs with a total of 2507 patients (mean difference, ‒1.22 units/year; 95% confidence interval, ‒1.83 to ‒.60). The minimum clinically important difference on the 76-item questionnaire was 4 units.2

Adding ICS to LABA increases risk of pneumonia and candidiasis

A Cochrane meta-analysis of 14 double-blind RCTs comprising a total of 11,794 participants with severe COPD compared LABA plus ICS with LABA alone over 8 weeks to 3 years.3 Primary outcomes were exacerbations, mortality, hospitalizations, and pneumonia. Secondary outcomes included oropharyngeal candidiasis and health-related QOL.

The LABA-plus-ICS group had lower rates of exacerbations than the LABA group, but the data were of low quality because of significant heterogeneity among studies and high rates of attrition. No significant difference in mortality or hospitalizations was found between the groups. The risk of pneumonia in the LABA-plus-ICS group was higher than in the LABA-alone group, with a NNH of 48.

Candidiasis occurred more often in patients on combination fluticasone and salmeterol than salmeterol alone, with a NNH of 22. QOL scores (measured by the SGRQ) in patients on combination therapy were statistically better, but clinically insignificant.

Discontinuing ICS doesn’t increase exacerbations

A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs that enrolled a total of 877 patients with COPD compared the number of exacerbations in patients who continued fluticasone 500 mcg inhaled twice daily and patients who were withdrawn from the medication. All patients had been treated with ICS for at least 3 months, and had been on fluticasone for at least 2 weeks. Subjects had a baseline FEV1 between 25% and 80% predicted. No significant increase in exacerbations occurred after discontinuing ICS.4

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society, in a joint guideline, recommend against using ICS as monotherapy for patients with stable COPD. They acknowledge that these drugs are superior to placebo in reducing exacerbations, but note that concerns about their side-effect profile (thrush, potential for bone loss, and moderate to severe easy bruisability) make them less desirable than LABAs or long-acting inhaled anticholinergics.5

The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease likewise discourages long-term use of ICS because of the risk of pneumonia and fractures.6 Both groups note that patients with severe COPD may benefit from a combination of ICS and a long-acting medication (usually a LABA).

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), either alone or with a long-acting β agonist (LABA), reduce the frequency of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and statistically, but not clinically, improve quality of life (QOL) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, meta-analyses of heterogeneous studies).

However, ICS have no mortality benefit and don’t consistently improve forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes). They increase the risk of pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising (SOR: B, meta-analyses of secondary outcomes).

Withdrawal of ICS doesn’t significantly increase the risk of COPD exacerbation (SOR: B, a meta-analysis).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A Cochrane meta-analysis designed to determine the efficacy of ICS in patients with stable COPD found 55 randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) with a total of 16,154 participants that compared ICS with placebo for 2 weeks to 3 years duration.1 COPD varied from moderate to severe in most studies.

In pooled data, ICS for 2 or more years didn’t consistently improve lung function, the primary outcome (TABLE). However, the largest RCT (N=2617) of 3 years duration showed a small decrease in decline of FEV1 (55 mL compared with 42 mL, P value not provided). Regarding the secondary outcomes of mortality and exacerbations, ICS for a year or longer didn’t reduce mortality but decreased exacerbations by 19%.

Clinically significant adverse effects of ICS use included pneumonia, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and bruising; for ICS treatment longer than one year, the numbers needed to harm (NNH) compared with placebo were 30, 27, and 32, respectively. Bone fractures weren’t more common among ICS users. Investigators observed a statistical, but not clinical, QOL benefit as measured by the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) in 5 RCTs with a total of 2507 patients (mean difference, ‒1.22 units/year; 95% confidence interval, ‒1.83 to ‒.60). The minimum clinically important difference on the 76-item questionnaire was 4 units.2

Adding ICS to LABA increases risk of pneumonia and candidiasis

A Cochrane meta-analysis of 14 double-blind RCTs comprising a total of 11,794 participants with severe COPD compared LABA plus ICS with LABA alone over 8 weeks to 3 years.3 Primary outcomes were exacerbations, mortality, hospitalizations, and pneumonia. Secondary outcomes included oropharyngeal candidiasis and health-related QOL.

The LABA-plus-ICS group had lower rates of exacerbations than the LABA group, but the data were of low quality because of significant heterogeneity among studies and high rates of attrition. No significant difference in mortality or hospitalizations was found between the groups. The risk of pneumonia in the LABA-plus-ICS group was higher than in the LABA-alone group, with a NNH of 48.

Candidiasis occurred more often in patients on combination fluticasone and salmeterol than salmeterol alone, with a NNH of 22. QOL scores (measured by the SGRQ) in patients on combination therapy were statistically better, but clinically insignificant.

Discontinuing ICS doesn’t increase exacerbations

A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs that enrolled a total of 877 patients with COPD compared the number of exacerbations in patients who continued fluticasone 500 mcg inhaled twice daily and patients who were withdrawn from the medication. All patients had been treated with ICS for at least 3 months, and had been on fluticasone for at least 2 weeks. Subjects had a baseline FEV1 between 25% and 80% predicted. No significant increase in exacerbations occurred after discontinuing ICS.4

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society, in a joint guideline, recommend against using ICS as monotherapy for patients with stable COPD. They acknowledge that these drugs are superior to placebo in reducing exacerbations, but note that concerns about their side-effect profile (thrush, potential for bone loss, and moderate to severe easy bruisability) make them less desirable than LABAs or long-acting inhaled anticholinergics.5

The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease likewise discourages long-term use of ICS because of the risk of pneumonia and fractures.6 Both groups note that patients with severe COPD may benefit from a combination of ICS and a long-acting medication (usually a LABA).

1. Yang IA, Clarke MS, Sim EH, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(7):CD002991.

2. Jones PW. St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire: MCID. COPD. 2005;2:75-79.

3. Nannini LJ, Lasserson TJ, Poole P. Combined corticosteroid and long-acting beta(2)-agonist in one inhaler versus long-acting beta(2)-agonists for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9:CD006829.

4. Nadeem NJ, Taylor SJ, Eldridge SM. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids in individuals with COPD—a systemic review and comment on trial methodology. Respir Res. 2011;12:107.

5. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE, et al; American College of Physicians; American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:179-191.

6. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Web site. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD. 2014. Available at: www.goldcopd.org/uploads/users/files/GOLD_Report2014_Feb07.pdf. Accessed April 4, 2013.

1. Yang IA, Clarke MS, Sim EH, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(7):CD002991.

2. Jones PW. St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire: MCID. COPD. 2005;2:75-79.

3. Nannini LJ, Lasserson TJ, Poole P. Combined corticosteroid and long-acting beta(2)-agonist in one inhaler versus long-acting beta(2)-agonists for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9:CD006829.

4. Nadeem NJ, Taylor SJ, Eldridge SM. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids in individuals with COPD—a systemic review and comment on trial methodology. Respir Res. 2011;12:107.

5. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE, et al; American College of Physicians; American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:179-191.

6. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Web site. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD. 2014. Available at: www.goldcopd.org/uploads/users/files/GOLD_Report2014_Feb07.pdf. Accessed April 4, 2013.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network