User login

Do ACE inhibitors or ARBs help prevent kidney disease in patients with diabetes and normal BP?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2011 meta-analysis of 5 RCTs (total 2975 patients) that compared ACE inhibitor therapy with placebo in diabetic patients without hypertension and albuminuria found that ACE inhibitors reduced the risk of new-onset microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria by 18% (relative risk [RR]=0.82; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.73-0.92).1 Normal albuminuria was defined in all included studies as an albumin excretion rate of <30 mg/d on a timed specimen confirmed with 3 serial measurements.

The RCTs included patients treated with lisinopril, enalapril, and perindopril. All but one examined patients with type 1 diabetes (2781 patients). The study that evaluated type 2 diabetes (194 patients) assessed patients with hypertension who used other antihypertensives to achieve normal blood pressure targets before ACE inhibitor initiation, a potential limitation.

Compared with placebo or no treatment, ACE inhibitor therapy reduced the risk of death from any cause (6 studies; 11,350 patients; RR=0.84; 95% CI, 0.73-0.97).1 Patient populations across pooled RCTs were heterogeneous, including subjects with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, with or without hypertension, and with or without albuminuria.

ACE inhibitors increase risk of cough

Patients taking an ACE inhibitor have an increased risk of cough (6 studies; 11,791 patients; RR=1.84; 95% CI, 1.24-2.72).1 ACE inhibitor therapy doesn’t increase the risk of headache or hyperkalemia.

ARBs don’t help prevent diabetic kidney disease in normotensive patients

The 2011 meta-analysis also included 5 RCTs (4604 patients, approximately 3000 with type 2 diabetes and more than 1000 with type 1 diabetes) that compared ARBs with placebo in patients without hypertension.1 Unlike ACE inhibitor therapy, ARB treatment didn’t significantly affect new-onset microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria (RR=1.06; 95% CI, 0.67-1.69).

The trials evaluated losartan, candesartan, olmesartan, and valsartan. One study used other antihypertensives to achieve target blood pressure, and another included patients of any albuminuria status.

Compared with placebo or no treatment, ARBs didn’t reduce the risk of death (5 studies; 7653 patients; RR=1.12; 95% CI, 0.88-1.41).1 All 5 RCTs assessed normoalbuminuric patients. Three of the 5 studies examined normotensive patients; one evaluated only hypertensive patients, and another assessed mostly hypertensive patients.

ARBs usually don’t produce significant adverse effects

Within the meta-analysis, ARBs didn’t increase risk of cough, headache, or hyperkalemia.1

1. Lv J, Perkovic V, Foote CV, et al. Antihypertensive agents for preventing diabetic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(12):CD004136.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2011 meta-analysis of 5 RCTs (total 2975 patients) that compared ACE inhibitor therapy with placebo in diabetic patients without hypertension and albuminuria found that ACE inhibitors reduced the risk of new-onset microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria by 18% (relative risk [RR]=0.82; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.73-0.92).1 Normal albuminuria was defined in all included studies as an albumin excretion rate of <30 mg/d on a timed specimen confirmed with 3 serial measurements.

The RCTs included patients treated with lisinopril, enalapril, and perindopril. All but one examined patients with type 1 diabetes (2781 patients). The study that evaluated type 2 diabetes (194 patients) assessed patients with hypertension who used other antihypertensives to achieve normal blood pressure targets before ACE inhibitor initiation, a potential limitation.

Compared with placebo or no treatment, ACE inhibitor therapy reduced the risk of death from any cause (6 studies; 11,350 patients; RR=0.84; 95% CI, 0.73-0.97).1 Patient populations across pooled RCTs were heterogeneous, including subjects with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, with or without hypertension, and with or without albuminuria.

ACE inhibitors increase risk of cough

Patients taking an ACE inhibitor have an increased risk of cough (6 studies; 11,791 patients; RR=1.84; 95% CI, 1.24-2.72).1 ACE inhibitor therapy doesn’t increase the risk of headache or hyperkalemia.

ARBs don’t help prevent diabetic kidney disease in normotensive patients

The 2011 meta-analysis also included 5 RCTs (4604 patients, approximately 3000 with type 2 diabetes and more than 1000 with type 1 diabetes) that compared ARBs with placebo in patients without hypertension.1 Unlike ACE inhibitor therapy, ARB treatment didn’t significantly affect new-onset microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria (RR=1.06; 95% CI, 0.67-1.69).

The trials evaluated losartan, candesartan, olmesartan, and valsartan. One study used other antihypertensives to achieve target blood pressure, and another included patients of any albuminuria status.

Compared with placebo or no treatment, ARBs didn’t reduce the risk of death (5 studies; 7653 patients; RR=1.12; 95% CI, 0.88-1.41).1 All 5 RCTs assessed normoalbuminuric patients. Three of the 5 studies examined normotensive patients; one evaluated only hypertensive patients, and another assessed mostly hypertensive patients.

ARBs usually don’t produce significant adverse effects

Within the meta-analysis, ARBs didn’t increase risk of cough, headache, or hyperkalemia.1

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2011 meta-analysis of 5 RCTs (total 2975 patients) that compared ACE inhibitor therapy with placebo in diabetic patients without hypertension and albuminuria found that ACE inhibitors reduced the risk of new-onset microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria by 18% (relative risk [RR]=0.82; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.73-0.92).1 Normal albuminuria was defined in all included studies as an albumin excretion rate of <30 mg/d on a timed specimen confirmed with 3 serial measurements.

The RCTs included patients treated with lisinopril, enalapril, and perindopril. All but one examined patients with type 1 diabetes (2781 patients). The study that evaluated type 2 diabetes (194 patients) assessed patients with hypertension who used other antihypertensives to achieve normal blood pressure targets before ACE inhibitor initiation, a potential limitation.

Compared with placebo or no treatment, ACE inhibitor therapy reduced the risk of death from any cause (6 studies; 11,350 patients; RR=0.84; 95% CI, 0.73-0.97).1 Patient populations across pooled RCTs were heterogeneous, including subjects with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, with or without hypertension, and with or without albuminuria.

ACE inhibitors increase risk of cough

Patients taking an ACE inhibitor have an increased risk of cough (6 studies; 11,791 patients; RR=1.84; 95% CI, 1.24-2.72).1 ACE inhibitor therapy doesn’t increase the risk of headache or hyperkalemia.

ARBs don’t help prevent diabetic kidney disease in normotensive patients

The 2011 meta-analysis also included 5 RCTs (4604 patients, approximately 3000 with type 2 diabetes and more than 1000 with type 1 diabetes) that compared ARBs with placebo in patients without hypertension.1 Unlike ACE inhibitor therapy, ARB treatment didn’t significantly affect new-onset microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria (RR=1.06; 95% CI, 0.67-1.69).

The trials evaluated losartan, candesartan, olmesartan, and valsartan. One study used other antihypertensives to achieve target blood pressure, and another included patients of any albuminuria status.

Compared with placebo or no treatment, ARBs didn’t reduce the risk of death (5 studies; 7653 patients; RR=1.12; 95% CI, 0.88-1.41).1 All 5 RCTs assessed normoalbuminuric patients. Three of the 5 studies examined normotensive patients; one evaluated only hypertensive patients, and another assessed mostly hypertensive patients.

ARBs usually don’t produce significant adverse effects

Within the meta-analysis, ARBs didn’t increase risk of cough, headache, or hyperkalemia.1

1. Lv J, Perkovic V, Foote CV, et al. Antihypertensive agents for preventing diabetic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(12):CD004136.

1. Lv J, Perkovic V, Foote CV, et al. Antihypertensive agents for preventing diabetic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(12):CD004136.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Yes for angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, no for angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs).

In normotensive patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, ACE inhibitor therapy reduces the risk of developing diabetic kidney disease, defined as new-onset microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria, by 18% (strength of recommendation [SOR]: C, meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [RCTs], disease-oriented evidence).

ACE inhibitor treatment improves all-cause mortality by 16% in patients with diabetes, including patients with and without hypertension. Patients on ACE inhibitor therapy are at increased risk of cough (SOR: A, meta-analysis of RCTs).

ARB therapy doesn’t lower the risk of developing kidney disease in normotensive patients with type 2 diabetes (SOR: C, meta-analysis of RCTs, disease-oriented evidence); nor does it reduce all-cause mortality in patients with or without hypertension (SOR: A, meta-analysis of RCTs). ARBs aren’t associated with significant adverse events (SOR: A, meta-analysis of RCTs).

Is there an increased risk of GI bleeds with SSRIs?

Yes. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are likely associated with a moderate increased risk of upper gastrointestinal (UGI) bleeding. Use of a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) in combination with the SSRI appears to amplify the risk (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, meta-analysis of cohort and case control studies).

The increased risk from SSRIs occurs within the first 7 to 28 days after exposure (SOR: B, retrospective study).

SSRIs raise bleeding risk; concurrent NSAIDs raise it more

A 2014 systematic review and meta-analysis of 19 case-control and cohort studies with a total of 446,949 patients investigated the risk of UGI bleeding in patients using SSRIs and NSAIDs.1 The studies, which included both inpatients and outpatients, were done in Europe and North America. Patients were at least 16 years old, but pooled demographics were not reported. Investigators compared SSRI use with or without concurrent NSAID use to placebo or no treatment.

SSRI use was associated with an increased risk of UGI bleeding in 15 case-control studies (393,268 patients; odds ratio [OR]=1.7; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.4-1.9) and 4 cohort studies (53,681 patients; OR=1.7; 95% CI, 1.1-2.5). The simultaneous use of SSRIs and NSAIDs compared to nonuse of both medications was associated with a larger increase in bleeding risk (10 case-control studies, 223,336 patients; OR=4.3; 95% CI, 2.8-6.4).

The meta-analysis is limited by statistically significant heterogeneity in all of the pooled results and high risk of bias in 9 of the case-control studies and all of the cohort studies. There was no evidence of publication bias, however.

Bleeding risk rises 7 to 28 days after SSRI exposure

A 2014 case-crossover study of 5377 inpatients in Taiwan with a psychiatric diagnosis evaluated the risk of UGI bleeding within the first 28 days after SSRI exposure (SSRI-mediated inhibition of platelets occurs within the first 7 to 14 days).2 The average age of the patients was 58 years and 75% of the study population was male. Each patient served as his or her own control.

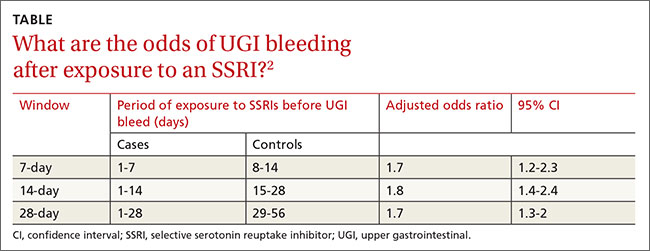

ORs were calculated to compare patients who were exposed to SSRIs only during 7-, 14-, and 21-day windows immediately before a UGI bleed to controls exposed to SSRIs only during the control periods before the 7-, 14-, and 21-day windows. The ORs were adjusted through multivariate analysis to account for 7 potential confounding factors.

SSRI use was associated with an increased risk of UGI bleeding in 7-, 14-, and 21-day windows before the index event (TABLE2). An increased bleeding risk in the 14 days after SSRI initiation was observed in men (OR=2.4; 95% CI, 1.8-3.4) but not women (OR=1.0; 95% CI, 0.6-1.6). Increased bleeding risk in the 14 days after SSRI initiation was also observed in patients younger than 55 years (OR=2.1; 95% CI, 1.5-3.1), patients with a history of upper GI disease (OR=3.1; 95% CI, 1.7-6.0), and patients with no previous exposure to SSRIs (OR=2.6; 95% CI, 1.6-4.2).

This study didn’t account for SSRI indication as a potential confounder, and the study’s inclusion of inpatients, whose illnesses are typically more severe, may limit generalizability.

1. Anglin R, Yuan Y, Moayyedi P, et al. Risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors with or without concurrent nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:811-819.

2. Wang YP, Chen YT, Tsai C, et al. Short-term use of serotonin reuptake inhibitors and risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171:54-61.

Yes. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are likely associated with a moderate increased risk of upper gastrointestinal (UGI) bleeding. Use of a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) in combination with the SSRI appears to amplify the risk (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, meta-analysis of cohort and case control studies).

The increased risk from SSRIs occurs within the first 7 to 28 days after exposure (SOR: B, retrospective study).

SSRIs raise bleeding risk; concurrent NSAIDs raise it more

A 2014 systematic review and meta-analysis of 19 case-control and cohort studies with a total of 446,949 patients investigated the risk of UGI bleeding in patients using SSRIs and NSAIDs.1 The studies, which included both inpatients and outpatients, were done in Europe and North America. Patients were at least 16 years old, but pooled demographics were not reported. Investigators compared SSRI use with or without concurrent NSAID use to placebo or no treatment.

SSRI use was associated with an increased risk of UGI bleeding in 15 case-control studies (393,268 patients; odds ratio [OR]=1.7; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.4-1.9) and 4 cohort studies (53,681 patients; OR=1.7; 95% CI, 1.1-2.5). The simultaneous use of SSRIs and NSAIDs compared to nonuse of both medications was associated with a larger increase in bleeding risk (10 case-control studies, 223,336 patients; OR=4.3; 95% CI, 2.8-6.4).

The meta-analysis is limited by statistically significant heterogeneity in all of the pooled results and high risk of bias in 9 of the case-control studies and all of the cohort studies. There was no evidence of publication bias, however.

Bleeding risk rises 7 to 28 days after SSRI exposure

A 2014 case-crossover study of 5377 inpatients in Taiwan with a psychiatric diagnosis evaluated the risk of UGI bleeding within the first 28 days after SSRI exposure (SSRI-mediated inhibition of platelets occurs within the first 7 to 14 days).2 The average age of the patients was 58 years and 75% of the study population was male. Each patient served as his or her own control.

ORs were calculated to compare patients who were exposed to SSRIs only during 7-, 14-, and 21-day windows immediately before a UGI bleed to controls exposed to SSRIs only during the control periods before the 7-, 14-, and 21-day windows. The ORs were adjusted through multivariate analysis to account for 7 potential confounding factors.

SSRI use was associated with an increased risk of UGI bleeding in 7-, 14-, and 21-day windows before the index event (TABLE2). An increased bleeding risk in the 14 days after SSRI initiation was observed in men (OR=2.4; 95% CI, 1.8-3.4) but not women (OR=1.0; 95% CI, 0.6-1.6). Increased bleeding risk in the 14 days after SSRI initiation was also observed in patients younger than 55 years (OR=2.1; 95% CI, 1.5-3.1), patients with a history of upper GI disease (OR=3.1; 95% CI, 1.7-6.0), and patients with no previous exposure to SSRIs (OR=2.6; 95% CI, 1.6-4.2).

This study didn’t account for SSRI indication as a potential confounder, and the study’s inclusion of inpatients, whose illnesses are typically more severe, may limit generalizability.

Yes. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are likely associated with a moderate increased risk of upper gastrointestinal (UGI) bleeding. Use of a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) in combination with the SSRI appears to amplify the risk (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, meta-analysis of cohort and case control studies).

The increased risk from SSRIs occurs within the first 7 to 28 days after exposure (SOR: B, retrospective study).

SSRIs raise bleeding risk; concurrent NSAIDs raise it more

A 2014 systematic review and meta-analysis of 19 case-control and cohort studies with a total of 446,949 patients investigated the risk of UGI bleeding in patients using SSRIs and NSAIDs.1 The studies, which included both inpatients and outpatients, were done in Europe and North America. Patients were at least 16 years old, but pooled demographics were not reported. Investigators compared SSRI use with or without concurrent NSAID use to placebo or no treatment.

SSRI use was associated with an increased risk of UGI bleeding in 15 case-control studies (393,268 patients; odds ratio [OR]=1.7; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.4-1.9) and 4 cohort studies (53,681 patients; OR=1.7; 95% CI, 1.1-2.5). The simultaneous use of SSRIs and NSAIDs compared to nonuse of both medications was associated with a larger increase in bleeding risk (10 case-control studies, 223,336 patients; OR=4.3; 95% CI, 2.8-6.4).

The meta-analysis is limited by statistically significant heterogeneity in all of the pooled results and high risk of bias in 9 of the case-control studies and all of the cohort studies. There was no evidence of publication bias, however.

Bleeding risk rises 7 to 28 days after SSRI exposure

A 2014 case-crossover study of 5377 inpatients in Taiwan with a psychiatric diagnosis evaluated the risk of UGI bleeding within the first 28 days after SSRI exposure (SSRI-mediated inhibition of platelets occurs within the first 7 to 14 days).2 The average age of the patients was 58 years and 75% of the study population was male. Each patient served as his or her own control.

ORs were calculated to compare patients who were exposed to SSRIs only during 7-, 14-, and 21-day windows immediately before a UGI bleed to controls exposed to SSRIs only during the control periods before the 7-, 14-, and 21-day windows. The ORs were adjusted through multivariate analysis to account for 7 potential confounding factors.

SSRI use was associated with an increased risk of UGI bleeding in 7-, 14-, and 21-day windows before the index event (TABLE2). An increased bleeding risk in the 14 days after SSRI initiation was observed in men (OR=2.4; 95% CI, 1.8-3.4) but not women (OR=1.0; 95% CI, 0.6-1.6). Increased bleeding risk in the 14 days after SSRI initiation was also observed in patients younger than 55 years (OR=2.1; 95% CI, 1.5-3.1), patients with a history of upper GI disease (OR=3.1; 95% CI, 1.7-6.0), and patients with no previous exposure to SSRIs (OR=2.6; 95% CI, 1.6-4.2).

This study didn’t account for SSRI indication as a potential confounder, and the study’s inclusion of inpatients, whose illnesses are typically more severe, may limit generalizability.

1. Anglin R, Yuan Y, Moayyedi P, et al. Risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors with or without concurrent nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:811-819.

2. Wang YP, Chen YT, Tsai C, et al. Short-term use of serotonin reuptake inhibitors and risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171:54-61.

1. Anglin R, Yuan Y, Moayyedi P, et al. Risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors with or without concurrent nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:811-819.

2. Wang YP, Chen YT, Tsai C, et al. Short-term use of serotonin reuptake inhibitors and risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171:54-61.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network