User login

How does gender-affirming hormone therapy affect QOL in transgender patients?

Evidence summary

GAHT may improve depression and quality of life, but not anxiety

A well-done systematic review of transgender men and transgender women demonstrated that GAHT of more than a year’s duration was associated with modestly improved standardized scores for QOL, depression, and possibly anxiety.1 It was also associated with improved scores for depression in transgender adolescents.

The authors identified 15 prospective cohort studies (n = 626 transgender adults [mean age, 25-34 years]; 198 transgender adolescent girls and boys [mean age, 15-16 years]), 2 retrospective cohort studies (n = 1756 adults; mean age, 25-32 years), and 4 cross-sectional studies (n = 336 adults; mean age, 30-37 years).

Researchers recruited participants using strict eligibility criteria (psychiatric evaluation and formal diagnosis of gender dysphoria), with no prior history of GAHT, largely from gender-affirming specialty clinics at university hospitals. Most studies were conducted after the year 2000, predominantly in Europe (8 studies in Italy; 2 each in Belgium, the Netherlands, the United States, and Spain).

GAHT comprised testosterone for transgender men (14 studies used injectable testosterone cypionate, enanthate, undecanoate, or transdermal gels), estrogens (usually with an anti-androgen such as cyproterone acetate or spironolactone) for transgender women (10 studies used transdermal, oral, or injectable estradiol valerate or conjugated estrogens), and gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) therapy for transgender adolescents (3 studies).

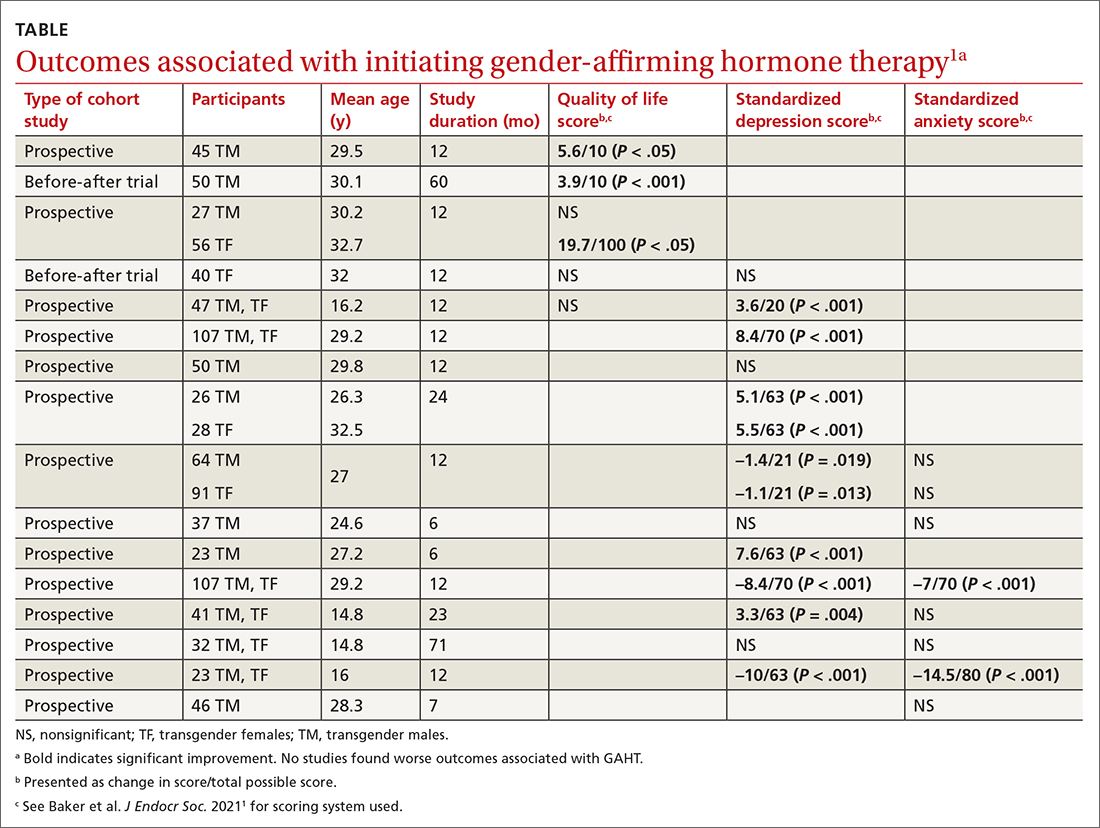

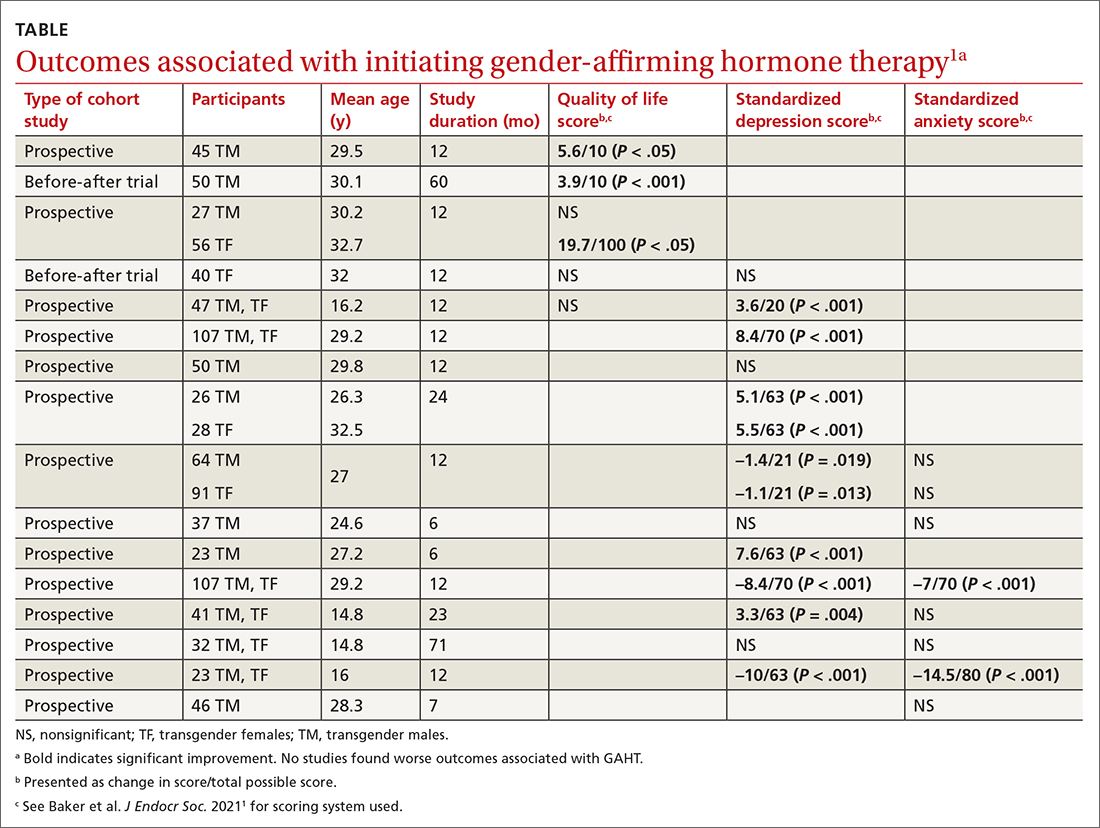

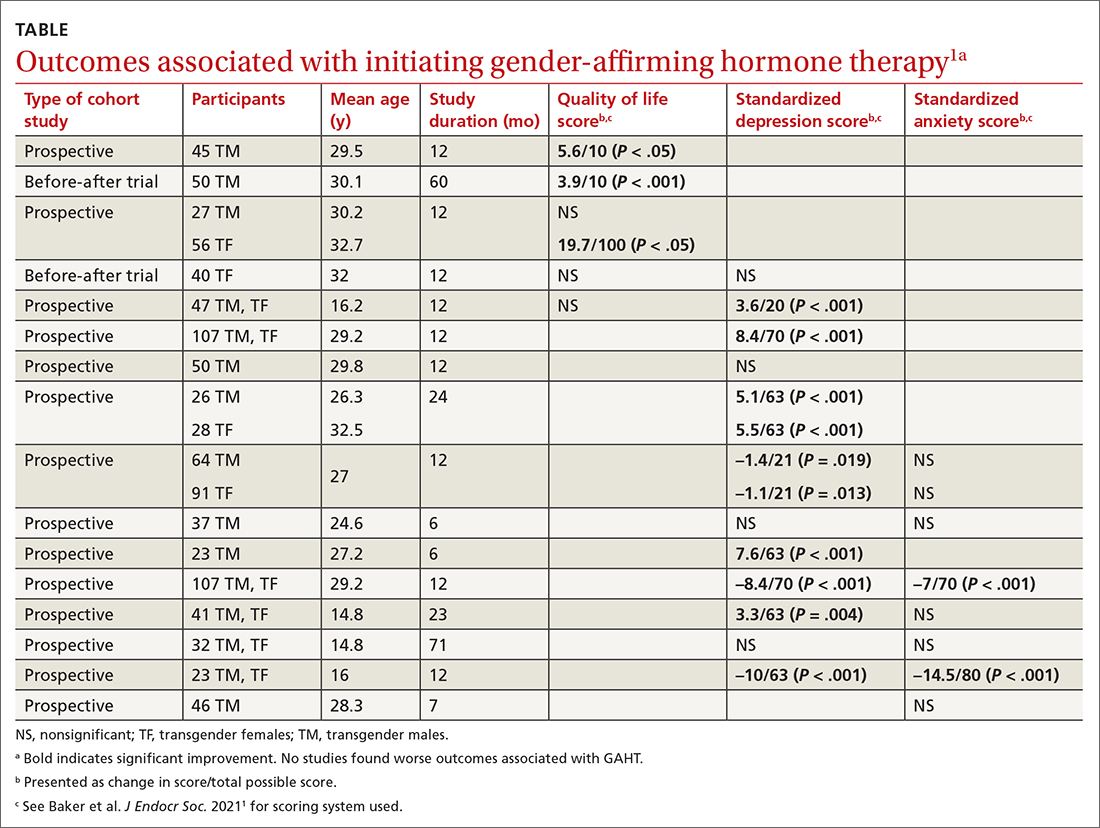

Researchers evaluated the outcomes of QOL, depression, and anxiety with standardized scores on validated screening tools and suicide (2 studies) by medical records. GAHT in adult transgender men and transgender women was associated with modest improvements in QOL (3 of 5 studies) and depression (8 of 12 studies), and some improvement in anxiety scores (2 of 8 studies; see TABLE1). There was insufficient evidence to determine whether GAHT had any effect on suicide. In adolescent transgender girls and boys, GAHT was associated with modest improvements in depression but not QOL or anxiety scores.

The authors rated the strength of evidence from the included studies as low, based on study quality (small study sizes, uncontrolled confounding factors, and risk of bias in study designs).

Additional research supports GAHT’s association with improved outcomes

Three studies, published after the systematic review, evaluated outcomes before and after GAHT and found similar results. All studies recruited treatment-seeking participants from specialty clinics.

Continue to: An Australian propsective longitudinal..

An Australian prospective longitudinal controlled study (n = 77 transgender adults; 103 cisgender controls) evaluated GAHT outcomes after 6 months and found a significant reduction in gender dysphoria scores in both transgender males (adjusted mean difference [aMD] = –6.8; 95% CI, –8.7 to –4.9; P < .001) and transgender females (aMD = –4.2; 95% CI, –6.2 to –2.2; P < .001) vs controls. QOL scores (emotional well-being, social functioning) improved only for transgender males (well-being: aMD = +7.5; 95% CI, 1.3 to 13.6; P < .018; social functioning: aMD = +12.5; 95% CI, 2.8 to 22.2; P = .011).2

A US prospective cohort study (n = 104 adolescents; mean age, 16 years) examined the effect of GnRH and/or GAHT over a 12-month period and found significant decreases in standardized scores for depression (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 0.4; 95% CI, 0.17-0.95) and suicidality (aOR = 0.27; 95% CI, 0.11-0.65) but not for anxiety. Participants who did not receive hormonal interventions had increased scores for depression and suicidality at 3 and 6 months’ follow-up.3

A prospective cohort study from the UK (n = 178 transgender adults) examined outcomes before and after GAHT treatment over 18 months and found significant decreases in standardized scores for depression (transgender males: –2.1; 95% CI, –3.2 to –1.2; P < .001; transgender females: –1.9; 95% CI, –2.8 to –1.0; P < .001) but not for anxiety.4

A large US study shows GAHT may reduce depression scores

A recent large cross-sectional study from the United States (n = 11,914 transgender or nonbinary youth, ages 13-24 years) found that receiving GAHT was associated with significantly lower odds of recent depression (aOR = 0.73; P < .001) and suicidality (aOR = 0.74; P < .001) compared to those who wanted GAHT but did not receive it. The authors were unable to differentiate the effects of receiving GAHT from the effects of parental support for their child’s gender identity, which may be a confounding factor.5

Recommendations from others

The World Professional Association for Transgender Health Standards of Care state that “gender incongruence that causes clinically significant distress and impairment often requires medically necessary clinical interventions” and recommends “health care professionals initiate and continue gender-affirming hormone therapy … due to demonstrated improvement in psychosocial functioning and quality of life.”6 The Endocrine Society Position Statement on Transgender Health states that “medical intervention for transgender youth and adults (including … hormone therapy) is effective, relatively safe (when appropriately monitored), and has been established as the standard of care.”7 The American Academy of Family Physicians “supports gender-affirming care as an evidence-informed intervention that can promote health equity for gender-diverse individuals.”8

Editor’s takeaway

Family physicians commonly address many factors that can impact the QOL for our patients with gender dysphoria: lack of fixed residence, underemployment, food insecurity, and trauma. GAHT, especially in male-to-female transgender patients, may further improve QOL without evidence of harm.

1. Baker KE, Wilson LM, Sharma R, et al. Hormone therapy, mental health, and quality of life among transgender people: a systematic review. J Endocr Soc. 2021;5:bvab011. doi: 10.1210/jendso/bvab011

2. Foster Skewis L, Bretherton I, Leemaqz, SY, et al. Short-term effects of gender-affirming hormone therapy on dysphoria and quality of life in transgender individuals: a prospective controlled study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:717766.

3. Tordoff DM, Wanta JW, Collin A, et al. Mental health outcomes in transgender and nonbinary youths receiving gender-affirming care. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e220978. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.0978

4. Aldridge Z, Patel S, Guo B, et al. Long-term effect of gender-affirming hormone treatment on depression and anxiety symptoms in transgender people: a prospective cohort study. Andrology. 2021;9:1808-1816. doi: 10.1111/andr.12884

5. Green AE, DeChants JP, Price MN, et al. Association of gender-affirming hormone therapy with depression, thoughts of suicide, and attempted suicide among transgender and nonbinary youth. J Adolesc Health. 2022;70:643-649. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.10.036

6. World Professional Association for Transgender Health. Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender Nonconforming People. 8th version. Published 2022. Accessed November 17, 2022. www.wpath.org/publications/soc

7. Endocrine Society. Transgender health: an Endocrine Society position statement. Updated December 16, 2020. Accessed November 17, 2022. www.endocrine.org/advocacy/position-statements/transgender-health

8. American Academy of Family Physicians. Care for the transgender and gender nonbinary patient. Updated September 2022. Accessed November 17, 2022. www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/transgender-nonbinary.html

Evidence summary

GAHT may improve depression and quality of life, but not anxiety

A well-done systematic review of transgender men and transgender women demonstrated that GAHT of more than a year’s duration was associated with modestly improved standardized scores for QOL, depression, and possibly anxiety.1 It was also associated with improved scores for depression in transgender adolescents.

The authors identified 15 prospective cohort studies (n = 626 transgender adults [mean age, 25-34 years]; 198 transgender adolescent girls and boys [mean age, 15-16 years]), 2 retrospective cohort studies (n = 1756 adults; mean age, 25-32 years), and 4 cross-sectional studies (n = 336 adults; mean age, 30-37 years).

Researchers recruited participants using strict eligibility criteria (psychiatric evaluation and formal diagnosis of gender dysphoria), with no prior history of GAHT, largely from gender-affirming specialty clinics at university hospitals. Most studies were conducted after the year 2000, predominantly in Europe (8 studies in Italy; 2 each in Belgium, the Netherlands, the United States, and Spain).

GAHT comprised testosterone for transgender men (14 studies used injectable testosterone cypionate, enanthate, undecanoate, or transdermal gels), estrogens (usually with an anti-androgen such as cyproterone acetate or spironolactone) for transgender women (10 studies used transdermal, oral, or injectable estradiol valerate or conjugated estrogens), and gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) therapy for transgender adolescents (3 studies).

Researchers evaluated the outcomes of QOL, depression, and anxiety with standardized scores on validated screening tools and suicide (2 studies) by medical records. GAHT in adult transgender men and transgender women was associated with modest improvements in QOL (3 of 5 studies) and depression (8 of 12 studies), and some improvement in anxiety scores (2 of 8 studies; see TABLE1). There was insufficient evidence to determine whether GAHT had any effect on suicide. In adolescent transgender girls and boys, GAHT was associated with modest improvements in depression but not QOL or anxiety scores.

The authors rated the strength of evidence from the included studies as low, based on study quality (small study sizes, uncontrolled confounding factors, and risk of bias in study designs).

Additional research supports GAHT’s association with improved outcomes

Three studies, published after the systematic review, evaluated outcomes before and after GAHT and found similar results. All studies recruited treatment-seeking participants from specialty clinics.

Continue to: An Australian propsective longitudinal..

An Australian prospective longitudinal controlled study (n = 77 transgender adults; 103 cisgender controls) evaluated GAHT outcomes after 6 months and found a significant reduction in gender dysphoria scores in both transgender males (adjusted mean difference [aMD] = –6.8; 95% CI, –8.7 to –4.9; P < .001) and transgender females (aMD = –4.2; 95% CI, –6.2 to –2.2; P < .001) vs controls. QOL scores (emotional well-being, social functioning) improved only for transgender males (well-being: aMD = +7.5; 95% CI, 1.3 to 13.6; P < .018; social functioning: aMD = +12.5; 95% CI, 2.8 to 22.2; P = .011).2

A US prospective cohort study (n = 104 adolescents; mean age, 16 years) examined the effect of GnRH and/or GAHT over a 12-month period and found significant decreases in standardized scores for depression (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 0.4; 95% CI, 0.17-0.95) and suicidality (aOR = 0.27; 95% CI, 0.11-0.65) but not for anxiety. Participants who did not receive hormonal interventions had increased scores for depression and suicidality at 3 and 6 months’ follow-up.3

A prospective cohort study from the UK (n = 178 transgender adults) examined outcomes before and after GAHT treatment over 18 months and found significant decreases in standardized scores for depression (transgender males: –2.1; 95% CI, –3.2 to –1.2; P < .001; transgender females: –1.9; 95% CI, –2.8 to –1.0; P < .001) but not for anxiety.4

A large US study shows GAHT may reduce depression scores

A recent large cross-sectional study from the United States (n = 11,914 transgender or nonbinary youth, ages 13-24 years) found that receiving GAHT was associated with significantly lower odds of recent depression (aOR = 0.73; P < .001) and suicidality (aOR = 0.74; P < .001) compared to those who wanted GAHT but did not receive it. The authors were unable to differentiate the effects of receiving GAHT from the effects of parental support for their child’s gender identity, which may be a confounding factor.5

Recommendations from others

The World Professional Association for Transgender Health Standards of Care state that “gender incongruence that causes clinically significant distress and impairment often requires medically necessary clinical interventions” and recommends “health care professionals initiate and continue gender-affirming hormone therapy … due to demonstrated improvement in psychosocial functioning and quality of life.”6 The Endocrine Society Position Statement on Transgender Health states that “medical intervention for transgender youth and adults (including … hormone therapy) is effective, relatively safe (when appropriately monitored), and has been established as the standard of care.”7 The American Academy of Family Physicians “supports gender-affirming care as an evidence-informed intervention that can promote health equity for gender-diverse individuals.”8

Editor’s takeaway

Family physicians commonly address many factors that can impact the QOL for our patients with gender dysphoria: lack of fixed residence, underemployment, food insecurity, and trauma. GAHT, especially in male-to-female transgender patients, may further improve QOL without evidence of harm.

Evidence summary

GAHT may improve depression and quality of life, but not anxiety

A well-done systematic review of transgender men and transgender women demonstrated that GAHT of more than a year’s duration was associated with modestly improved standardized scores for QOL, depression, and possibly anxiety.1 It was also associated with improved scores for depression in transgender adolescents.

The authors identified 15 prospective cohort studies (n = 626 transgender adults [mean age, 25-34 years]; 198 transgender adolescent girls and boys [mean age, 15-16 years]), 2 retrospective cohort studies (n = 1756 adults; mean age, 25-32 years), and 4 cross-sectional studies (n = 336 adults; mean age, 30-37 years).

Researchers recruited participants using strict eligibility criteria (psychiatric evaluation and formal diagnosis of gender dysphoria), with no prior history of GAHT, largely from gender-affirming specialty clinics at university hospitals. Most studies were conducted after the year 2000, predominantly in Europe (8 studies in Italy; 2 each in Belgium, the Netherlands, the United States, and Spain).

GAHT comprised testosterone for transgender men (14 studies used injectable testosterone cypionate, enanthate, undecanoate, or transdermal gels), estrogens (usually with an anti-androgen such as cyproterone acetate or spironolactone) for transgender women (10 studies used transdermal, oral, or injectable estradiol valerate or conjugated estrogens), and gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) therapy for transgender adolescents (3 studies).

Researchers evaluated the outcomes of QOL, depression, and anxiety with standardized scores on validated screening tools and suicide (2 studies) by medical records. GAHT in adult transgender men and transgender women was associated with modest improvements in QOL (3 of 5 studies) and depression (8 of 12 studies), and some improvement in anxiety scores (2 of 8 studies; see TABLE1). There was insufficient evidence to determine whether GAHT had any effect on suicide. In adolescent transgender girls and boys, GAHT was associated with modest improvements in depression but not QOL or anxiety scores.

The authors rated the strength of evidence from the included studies as low, based on study quality (small study sizes, uncontrolled confounding factors, and risk of bias in study designs).

Additional research supports GAHT’s association with improved outcomes

Three studies, published after the systematic review, evaluated outcomes before and after GAHT and found similar results. All studies recruited treatment-seeking participants from specialty clinics.

Continue to: An Australian propsective longitudinal..

An Australian prospective longitudinal controlled study (n = 77 transgender adults; 103 cisgender controls) evaluated GAHT outcomes after 6 months and found a significant reduction in gender dysphoria scores in both transgender males (adjusted mean difference [aMD] = –6.8; 95% CI, –8.7 to –4.9; P < .001) and transgender females (aMD = –4.2; 95% CI, –6.2 to –2.2; P < .001) vs controls. QOL scores (emotional well-being, social functioning) improved only for transgender males (well-being: aMD = +7.5; 95% CI, 1.3 to 13.6; P < .018; social functioning: aMD = +12.5; 95% CI, 2.8 to 22.2; P = .011).2

A US prospective cohort study (n = 104 adolescents; mean age, 16 years) examined the effect of GnRH and/or GAHT over a 12-month period and found significant decreases in standardized scores for depression (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 0.4; 95% CI, 0.17-0.95) and suicidality (aOR = 0.27; 95% CI, 0.11-0.65) but not for anxiety. Participants who did not receive hormonal interventions had increased scores for depression and suicidality at 3 and 6 months’ follow-up.3

A prospective cohort study from the UK (n = 178 transgender adults) examined outcomes before and after GAHT treatment over 18 months and found significant decreases in standardized scores for depression (transgender males: –2.1; 95% CI, –3.2 to –1.2; P < .001; transgender females: –1.9; 95% CI, –2.8 to –1.0; P < .001) but not for anxiety.4

A large US study shows GAHT may reduce depression scores

A recent large cross-sectional study from the United States (n = 11,914 transgender or nonbinary youth, ages 13-24 years) found that receiving GAHT was associated with significantly lower odds of recent depression (aOR = 0.73; P < .001) and suicidality (aOR = 0.74; P < .001) compared to those who wanted GAHT but did not receive it. The authors were unable to differentiate the effects of receiving GAHT from the effects of parental support for their child’s gender identity, which may be a confounding factor.5

Recommendations from others

The World Professional Association for Transgender Health Standards of Care state that “gender incongruence that causes clinically significant distress and impairment often requires medically necessary clinical interventions” and recommends “health care professionals initiate and continue gender-affirming hormone therapy … due to demonstrated improvement in psychosocial functioning and quality of life.”6 The Endocrine Society Position Statement on Transgender Health states that “medical intervention for transgender youth and adults (including … hormone therapy) is effective, relatively safe (when appropriately monitored), and has been established as the standard of care.”7 The American Academy of Family Physicians “supports gender-affirming care as an evidence-informed intervention that can promote health equity for gender-diverse individuals.”8

Editor’s takeaway

Family physicians commonly address many factors that can impact the QOL for our patients with gender dysphoria: lack of fixed residence, underemployment, food insecurity, and trauma. GAHT, especially in male-to-female transgender patients, may further improve QOL without evidence of harm.

1. Baker KE, Wilson LM, Sharma R, et al. Hormone therapy, mental health, and quality of life among transgender people: a systematic review. J Endocr Soc. 2021;5:bvab011. doi: 10.1210/jendso/bvab011

2. Foster Skewis L, Bretherton I, Leemaqz, SY, et al. Short-term effects of gender-affirming hormone therapy on dysphoria and quality of life in transgender individuals: a prospective controlled study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:717766.

3. Tordoff DM, Wanta JW, Collin A, et al. Mental health outcomes in transgender and nonbinary youths receiving gender-affirming care. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e220978. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.0978

4. Aldridge Z, Patel S, Guo B, et al. Long-term effect of gender-affirming hormone treatment on depression and anxiety symptoms in transgender people: a prospective cohort study. Andrology. 2021;9:1808-1816. doi: 10.1111/andr.12884

5. Green AE, DeChants JP, Price MN, et al. Association of gender-affirming hormone therapy with depression, thoughts of suicide, and attempted suicide among transgender and nonbinary youth. J Adolesc Health. 2022;70:643-649. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.10.036

6. World Professional Association for Transgender Health. Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender Nonconforming People. 8th version. Published 2022. Accessed November 17, 2022. www.wpath.org/publications/soc

7. Endocrine Society. Transgender health: an Endocrine Society position statement. Updated December 16, 2020. Accessed November 17, 2022. www.endocrine.org/advocacy/position-statements/transgender-health

8. American Academy of Family Physicians. Care for the transgender and gender nonbinary patient. Updated September 2022. Accessed November 17, 2022. www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/transgender-nonbinary.html

1. Baker KE, Wilson LM, Sharma R, et al. Hormone therapy, mental health, and quality of life among transgender people: a systematic review. J Endocr Soc. 2021;5:bvab011. doi: 10.1210/jendso/bvab011

2. Foster Skewis L, Bretherton I, Leemaqz, SY, et al. Short-term effects of gender-affirming hormone therapy on dysphoria and quality of life in transgender individuals: a prospective controlled study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:717766.

3. Tordoff DM, Wanta JW, Collin A, et al. Mental health outcomes in transgender and nonbinary youths receiving gender-affirming care. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e220978. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.0978

4. Aldridge Z, Patel S, Guo B, et al. Long-term effect of gender-affirming hormone treatment on depression and anxiety symptoms in transgender people: a prospective cohort study. Andrology. 2021;9:1808-1816. doi: 10.1111/andr.12884

5. Green AE, DeChants JP, Price MN, et al. Association of gender-affirming hormone therapy with depression, thoughts of suicide, and attempted suicide among transgender and nonbinary youth. J Adolesc Health. 2022;70:643-649. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.10.036

6. World Professional Association for Transgender Health. Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender Nonconforming People. 8th version. Published 2022. Accessed November 17, 2022. www.wpath.org/publications/soc

7. Endocrine Society. Transgender health: an Endocrine Society position statement. Updated December 16, 2020. Accessed November 17, 2022. www.endocrine.org/advocacy/position-statements/transgender-health

8. American Academy of Family Physicians. Care for the transgender and gender nonbinary patient. Updated September 2022. Accessed November 17, 2022. www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/transgender-nonbinary.html

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

There are modest effects on depression but not anxiety. Gender-affirming hormone therapy (GAHT) is associated with modest improvements in standardized scores for quality of life (QOL) and depression in adult male-to-female and female-to-male transgender people and modest improvements in depression scores in transgender adolescents, but the effect on anxiety is uncertain (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, based on a preponderance of low-quality prospective cohort studies with inconsistent results).

GAHT is associated with reduced gender dysphoria and decreased suicidality (SOR: B, based on a prospective cohort study). However, there is insufficient evidence to determine any effect on suicide completion. No studies associated GAHT with worsened QOL, depression, or anxiety scores.

Which infants need lumbar puncture for suspected sepsis?

Evidence from prospective and retrospective clinical trials suggests that for infants <2 months old, only those at high risk for serious bacterial infection by standardized criteria (eg, Rochester classification) require lumbar puncture (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, based on prospective and retrospective cohort studies). However, expert opinion suggests lumbar puncture on all infants aged 0 to 28 days with suspected sepsis, and all infants aged >2 months who are to receive empiric antibiotics (SOR: C, based on expert opinion).

Evidence summary

Standardized clinical criteria (Table) exist to determine the risk of serious bacterial infection, which includes meningitis; of particular note, these criteria do not require cerebrospinal fluid examination. Infants aged <3 months who fall into the “high-risk” category or appear toxic have 21% probability of a serious bacterial infection, 10% probability of bacteremia, and 2% probability of bacterial meningitis.1 The “low-risk” infants have a correspondingly lower incidence of serious bacterial infection: the negative predictive value of the Rochester classification is 98.9% (95% confidence interval [CI], 97.2–99.6%).2

The negative predictive value for bacterial meningitis (a subset of serious bacterial infection) is even greater. Five studies applied the standardized criteria to febrile infants and monitored them for the development of serious bacterial infection, including meningitis. Two prospective cohort studies of outpatients aged 0 to 2 months used the Rochester criteria to assign infants to risk groups. They studied a total of 1294 infants; 659 (51%) were low-risk. None of the low-risk infants developed bacterial meningitis.2,3

One prospective cohort study of infants aged <1 month hospitalized for fever used a similar method for assessing risk, but added a C-reactive protein value <20 mg/L to criteria for low-risk. Of 250 infants studied, 131 (52%) were low-risk; none of these developed bacterial meningitis.4

A retrospective chart review of 492 infants aged <3 months who were hospitalized due to fever included 108 infants aged <1 month. Thirty percent (114) of the infants aged 1 to 3 months and 67% (72) of the younger infants underwent lumbar puncture at the discretion of the treating physician. All infants were retrospectively assigned to low- or high-risk groups for serious bacterial infection using the Rochester criteria. Of the 296 infants rated “low-risk,” none developed bacterial meningitis. Ten of these infants subsequently developed evidence of another bacterial focus (predominantly urinary tract infection).5

RECOMMENDATIONS FROM OTHERS

The American Academy of Pediatrics has not issued a clinical practice guideline or clinical report addressing this issue. An evidence-based guideline developed at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center in 1998 recommends hospitalization and a full sepsis workup (including lumbar puncture) for infants aged <1 month, or infants aged 1 to 2 months who are high-risk.6

A clinical review-based guideline published in 1993 gives the same recommendations.7 The expert panel that devised this guideline emphasized a full sepsis evaluation (including cerebrospinal fluid cultures) for infants <28 days of age “despite the low probability of serious bacterial infections in this age group and the favorable outcome of the children managed to date with careful observation.” For low-risk infants aged 1 to 2 months, lumbar puncture is not necessary unless empiric antibiotics are given; having a cerebrospinal fluid culture prior to empiric antibiotics reduces the concern of partially treated meningitis in the case of clinical deterioration after hospital discharge.6,7

TABLE

How to identify infants at low risk of serious bacterial infection: Rochester Classification

| Febrile infants (temperature ≥38°C, 100.4°F) ≥60 days of age who meet all criteria are at low risk of serious bacterial infection: | |

|---|---|

| General health | Born at ≥37 weeks’ gestation |

| Did not receive perinatal or antenatal antibiotics | |

| Was not treated for unexplained hyperbilirubinemia | |

| Was not hospitalized in the nursery longer than the mother | |

| Has had no hospitalization since discharge | |

| No diagnosed chronic or underlying illnesses | |

| Physical findings | Appears well and nontoxic |

| No evidence of skin, soft tissue, bone, or joint abnormalities, or otitis media | |

| Laboratory findings | Peripheral total white blood cells 5,000–15,000/mm3 |

| Absolute band form leukocytes <1,500/mm3 | |

| Spun urine sediment <10 white blood cells per high power field | |

| Fresh stool smear <5 white blood cells per high power field | |

Evaluating fever in infants: judging the risks

Randy Ward, MD

Family Medicine/Psychiatry Residency, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee

The evaluation of the febrile infant is often fraught with anxiety. Physicians must balance the potentially devastating consequences of a missed serious bacterial infection with the desire to avoid unnecessary work-ups.

In the past, guidelines have had an extremely conservative viewpoint, essentially grouping all infants by age, and recommended an extensive inpatient work-up regardless of clinical status. The Rochester Criteria have provided guidelines for clinical risk stratification in this age group, allowing a more rational approach to the workup. The above data provide further useful guidance for the appropriate use of lumbar puncture in evaluation of these infants.

1. Baraff LJ, Oslund SA, Schriger DL, Stephen ML. Probability of bacterial infections in febrile infants less than three months of age: a meta-analysis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1992;11:257-264.

2. Jaskiewicz JA, McCarthy CA, Richardson AC, et al. Febrile infants at low risk for serious bacterial infection—an appraisal of the Rochester criteria and implications for management. Febrile Infant Collaborative Study Group. Pediatrics 1994;94:390-396.

3. Dagan R, Sofer S, Phillip M, Shachak E. Ambulatory care of febrile infants younger than 2 months of age classified as being at low risk for having serious bacterial infections. J Pediatr 1988;112:355-360.

4. Chiu CH, Lin TY, Bullard MJ. Identification of febrile neonates unlikely to have bacterial infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1997;16:59-63.

5. Brik R, Hamissah R, Shehada N, Berant M. Evaluation of febrile infants under 3 months of age: is routine lumbar puncture warranted?. Isr J Med Sci 1997;33:93-97.

6. Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Evidence based clinical protocol guideline for fever of uncertain source in infants 60 days of age or less. Cincinnati, Ohio: Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center; 1998.

7. Baraff LJ, Bass JW, Fleisher GR, et al. Practice guideline for the management of infants and children 0 to 36 months of age with fever without source. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Ann Emerg Med 1993;22:1198-1210.

Evidence from prospective and retrospective clinical trials suggests that for infants <2 months old, only those at high risk for serious bacterial infection by standardized criteria (eg, Rochester classification) require lumbar puncture (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, based on prospective and retrospective cohort studies). However, expert opinion suggests lumbar puncture on all infants aged 0 to 28 days with suspected sepsis, and all infants aged >2 months who are to receive empiric antibiotics (SOR: C, based on expert opinion).

Evidence summary

Standardized clinical criteria (Table) exist to determine the risk of serious bacterial infection, which includes meningitis; of particular note, these criteria do not require cerebrospinal fluid examination. Infants aged <3 months who fall into the “high-risk” category or appear toxic have 21% probability of a serious bacterial infection, 10% probability of bacteremia, and 2% probability of bacterial meningitis.1 The “low-risk” infants have a correspondingly lower incidence of serious bacterial infection: the negative predictive value of the Rochester classification is 98.9% (95% confidence interval [CI], 97.2–99.6%).2

The negative predictive value for bacterial meningitis (a subset of serious bacterial infection) is even greater. Five studies applied the standardized criteria to febrile infants and monitored them for the development of serious bacterial infection, including meningitis. Two prospective cohort studies of outpatients aged 0 to 2 months used the Rochester criteria to assign infants to risk groups. They studied a total of 1294 infants; 659 (51%) were low-risk. None of the low-risk infants developed bacterial meningitis.2,3

One prospective cohort study of infants aged <1 month hospitalized for fever used a similar method for assessing risk, but added a C-reactive protein value <20 mg/L to criteria for low-risk. Of 250 infants studied, 131 (52%) were low-risk; none of these developed bacterial meningitis.4

A retrospective chart review of 492 infants aged <3 months who were hospitalized due to fever included 108 infants aged <1 month. Thirty percent (114) of the infants aged 1 to 3 months and 67% (72) of the younger infants underwent lumbar puncture at the discretion of the treating physician. All infants were retrospectively assigned to low- or high-risk groups for serious bacterial infection using the Rochester criteria. Of the 296 infants rated “low-risk,” none developed bacterial meningitis. Ten of these infants subsequently developed evidence of another bacterial focus (predominantly urinary tract infection).5

RECOMMENDATIONS FROM OTHERS

The American Academy of Pediatrics has not issued a clinical practice guideline or clinical report addressing this issue. An evidence-based guideline developed at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center in 1998 recommends hospitalization and a full sepsis workup (including lumbar puncture) for infants aged <1 month, or infants aged 1 to 2 months who are high-risk.6

A clinical review-based guideline published in 1993 gives the same recommendations.7 The expert panel that devised this guideline emphasized a full sepsis evaluation (including cerebrospinal fluid cultures) for infants <28 days of age “despite the low probability of serious bacterial infections in this age group and the favorable outcome of the children managed to date with careful observation.” For low-risk infants aged 1 to 2 months, lumbar puncture is not necessary unless empiric antibiotics are given; having a cerebrospinal fluid culture prior to empiric antibiotics reduces the concern of partially treated meningitis in the case of clinical deterioration after hospital discharge.6,7

TABLE

How to identify infants at low risk of serious bacterial infection: Rochester Classification

| Febrile infants (temperature ≥38°C, 100.4°F) ≥60 days of age who meet all criteria are at low risk of serious bacterial infection: | |

|---|---|

| General health | Born at ≥37 weeks’ gestation |

| Did not receive perinatal or antenatal antibiotics | |

| Was not treated for unexplained hyperbilirubinemia | |

| Was not hospitalized in the nursery longer than the mother | |

| Has had no hospitalization since discharge | |

| No diagnosed chronic or underlying illnesses | |

| Physical findings | Appears well and nontoxic |

| No evidence of skin, soft tissue, bone, or joint abnormalities, or otitis media | |

| Laboratory findings | Peripheral total white blood cells 5,000–15,000/mm3 |

| Absolute band form leukocytes <1,500/mm3 | |

| Spun urine sediment <10 white blood cells per high power field | |

| Fresh stool smear <5 white blood cells per high power field | |

Evaluating fever in infants: judging the risks

Randy Ward, MD

Family Medicine/Psychiatry Residency, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee

The evaluation of the febrile infant is often fraught with anxiety. Physicians must balance the potentially devastating consequences of a missed serious bacterial infection with the desire to avoid unnecessary work-ups.

In the past, guidelines have had an extremely conservative viewpoint, essentially grouping all infants by age, and recommended an extensive inpatient work-up regardless of clinical status. The Rochester Criteria have provided guidelines for clinical risk stratification in this age group, allowing a more rational approach to the workup. The above data provide further useful guidance for the appropriate use of lumbar puncture in evaluation of these infants.

Evidence from prospective and retrospective clinical trials suggests that for infants <2 months old, only those at high risk for serious bacterial infection by standardized criteria (eg, Rochester classification) require lumbar puncture (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, based on prospective and retrospective cohort studies). However, expert opinion suggests lumbar puncture on all infants aged 0 to 28 days with suspected sepsis, and all infants aged >2 months who are to receive empiric antibiotics (SOR: C, based on expert opinion).

Evidence summary

Standardized clinical criteria (Table) exist to determine the risk of serious bacterial infection, which includes meningitis; of particular note, these criteria do not require cerebrospinal fluid examination. Infants aged <3 months who fall into the “high-risk” category or appear toxic have 21% probability of a serious bacterial infection, 10% probability of bacteremia, and 2% probability of bacterial meningitis.1 The “low-risk” infants have a correspondingly lower incidence of serious bacterial infection: the negative predictive value of the Rochester classification is 98.9% (95% confidence interval [CI], 97.2–99.6%).2

The negative predictive value for bacterial meningitis (a subset of serious bacterial infection) is even greater. Five studies applied the standardized criteria to febrile infants and monitored them for the development of serious bacterial infection, including meningitis. Two prospective cohort studies of outpatients aged 0 to 2 months used the Rochester criteria to assign infants to risk groups. They studied a total of 1294 infants; 659 (51%) were low-risk. None of the low-risk infants developed bacterial meningitis.2,3

One prospective cohort study of infants aged <1 month hospitalized for fever used a similar method for assessing risk, but added a C-reactive protein value <20 mg/L to criteria for low-risk. Of 250 infants studied, 131 (52%) were low-risk; none of these developed bacterial meningitis.4

A retrospective chart review of 492 infants aged <3 months who were hospitalized due to fever included 108 infants aged <1 month. Thirty percent (114) of the infants aged 1 to 3 months and 67% (72) of the younger infants underwent lumbar puncture at the discretion of the treating physician. All infants were retrospectively assigned to low- or high-risk groups for serious bacterial infection using the Rochester criteria. Of the 296 infants rated “low-risk,” none developed bacterial meningitis. Ten of these infants subsequently developed evidence of another bacterial focus (predominantly urinary tract infection).5

RECOMMENDATIONS FROM OTHERS

The American Academy of Pediatrics has not issued a clinical practice guideline or clinical report addressing this issue. An evidence-based guideline developed at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center in 1998 recommends hospitalization and a full sepsis workup (including lumbar puncture) for infants aged <1 month, or infants aged 1 to 2 months who are high-risk.6

A clinical review-based guideline published in 1993 gives the same recommendations.7 The expert panel that devised this guideline emphasized a full sepsis evaluation (including cerebrospinal fluid cultures) for infants <28 days of age “despite the low probability of serious bacterial infections in this age group and the favorable outcome of the children managed to date with careful observation.” For low-risk infants aged 1 to 2 months, lumbar puncture is not necessary unless empiric antibiotics are given; having a cerebrospinal fluid culture prior to empiric antibiotics reduces the concern of partially treated meningitis in the case of clinical deterioration after hospital discharge.6,7

TABLE

How to identify infants at low risk of serious bacterial infection: Rochester Classification

| Febrile infants (temperature ≥38°C, 100.4°F) ≥60 days of age who meet all criteria are at low risk of serious bacterial infection: | |

|---|---|

| General health | Born at ≥37 weeks’ gestation |

| Did not receive perinatal or antenatal antibiotics | |

| Was not treated for unexplained hyperbilirubinemia | |

| Was not hospitalized in the nursery longer than the mother | |

| Has had no hospitalization since discharge | |

| No diagnosed chronic or underlying illnesses | |

| Physical findings | Appears well and nontoxic |

| No evidence of skin, soft tissue, bone, or joint abnormalities, or otitis media | |

| Laboratory findings | Peripheral total white blood cells 5,000–15,000/mm3 |

| Absolute band form leukocytes <1,500/mm3 | |

| Spun urine sediment <10 white blood cells per high power field | |

| Fresh stool smear <5 white blood cells per high power field | |

Evaluating fever in infants: judging the risks

Randy Ward, MD

Family Medicine/Psychiatry Residency, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee

The evaluation of the febrile infant is often fraught with anxiety. Physicians must balance the potentially devastating consequences of a missed serious bacterial infection with the desire to avoid unnecessary work-ups.

In the past, guidelines have had an extremely conservative viewpoint, essentially grouping all infants by age, and recommended an extensive inpatient work-up regardless of clinical status. The Rochester Criteria have provided guidelines for clinical risk stratification in this age group, allowing a more rational approach to the workup. The above data provide further useful guidance for the appropriate use of lumbar puncture in evaluation of these infants.

1. Baraff LJ, Oslund SA, Schriger DL, Stephen ML. Probability of bacterial infections in febrile infants less than three months of age: a meta-analysis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1992;11:257-264.

2. Jaskiewicz JA, McCarthy CA, Richardson AC, et al. Febrile infants at low risk for serious bacterial infection—an appraisal of the Rochester criteria and implications for management. Febrile Infant Collaborative Study Group. Pediatrics 1994;94:390-396.

3. Dagan R, Sofer S, Phillip M, Shachak E. Ambulatory care of febrile infants younger than 2 months of age classified as being at low risk for having serious bacterial infections. J Pediatr 1988;112:355-360.

4. Chiu CH, Lin TY, Bullard MJ. Identification of febrile neonates unlikely to have bacterial infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1997;16:59-63.

5. Brik R, Hamissah R, Shehada N, Berant M. Evaluation of febrile infants under 3 months of age: is routine lumbar puncture warranted?. Isr J Med Sci 1997;33:93-97.

6. Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Evidence based clinical protocol guideline for fever of uncertain source in infants 60 days of age or less. Cincinnati, Ohio: Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center; 1998.

7. Baraff LJ, Bass JW, Fleisher GR, et al. Practice guideline for the management of infants and children 0 to 36 months of age with fever without source. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Ann Emerg Med 1993;22:1198-1210.

1. Baraff LJ, Oslund SA, Schriger DL, Stephen ML. Probability of bacterial infections in febrile infants less than three months of age: a meta-analysis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1992;11:257-264.

2. Jaskiewicz JA, McCarthy CA, Richardson AC, et al. Febrile infants at low risk for serious bacterial infection—an appraisal of the Rochester criteria and implications for management. Febrile Infant Collaborative Study Group. Pediatrics 1994;94:390-396.

3. Dagan R, Sofer S, Phillip M, Shachak E. Ambulatory care of febrile infants younger than 2 months of age classified as being at low risk for having serious bacterial infections. J Pediatr 1988;112:355-360.

4. Chiu CH, Lin TY, Bullard MJ. Identification of febrile neonates unlikely to have bacterial infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1997;16:59-63.

5. Brik R, Hamissah R, Shehada N, Berant M. Evaluation of febrile infants under 3 months of age: is routine lumbar puncture warranted?. Isr J Med Sci 1997;33:93-97.

6. Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Evidence based clinical protocol guideline for fever of uncertain source in infants 60 days of age or less. Cincinnati, Ohio: Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center; 1998.

7. Baraff LJ, Bass JW, Fleisher GR, et al. Practice guideline for the management of infants and children 0 to 36 months of age with fever without source. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Ann Emerg Med 1993;22:1198-1210.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network