User login

A Randomized Cohort Controlled Trial to Compare Intern Sign-Out Training Interventions

Patient sign-outs are defined as the transition of patient care that includes the transfer of information, task accountability, and personal responsibility between providers.1-3 The adoption of mnemonics as a memory aid has been used to improve the transfer of patient information between providers.4 In the transfer of task accountability, providers transfer follow-up tasks to on-call or coverage providers and ensure that directives are understood. Joint task accountability is enhanced through collaborative giving and cross-checking of information received through assertive questioning to detect errors, and it also enables the receiver to codevelop an understanding of a patient’s condition.5-8 In the transfer of personal responsibility for the primary team’s patients, the provision of anticipatory guidance enables the coverage provider to have prospective information about potential, upcoming issues to facilitate care plans.6 Enabling coverage providers to anticipate overnight events helps them exercise responsibility for patients who are under their temporary care.2

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requires residency programs to provide formal instruction on sign-outs.9 Yet, variability across training programs exists,8,10 with training emphasis on the transfer of information over accountability or responsibility.11 Previous studies have demonstrated the efficacy of sign-out training, such as the illness severity, patient summary, action list, situation awareness and contingency planning, and synthesis by reviewer (I-PASS) bundle.3 Yet, participation is far from 100% because the I-PASS bundle requires in-person workshops, e-learning platforms, organizational change campaigns, and faculty participation,12 involving resource and time commitments that few programs can afford. To address this issue, we seek to compare resource-efficient, knowledge-based, skill-based, compliance-based, and learner-initiated sign-out training pedagogies. We focused on the evening sign-out because it is a high-risk period when care for inpatients is transferred to smaller coverage intern teams.

METHODS

Setting and Study Design

A prospective, randomized cohort trial of 4 training interventions was conducted at an internal medicine residency program at a Mid-Atlantic, academic, tertiary-care hospital with 1192 inpatient beds. The 52 interns admitted to the program were randomly assigned to 4 firms caring for up to 25 inpatients on each floor of the hospital. The case mix faced by each firm was similar because patients were randomly assigned to firms based on bed availability. Teams of 5 interns in each firm worked in 5-day duty cycles, during which each intern rotated as a night cover for his or her firm. Interns remain in their firm throughout their residency. Sign-outs were conducted face to face with a computer. Receivers printed sign-out sheets populated with patient information and took notes when senders communicated information from the computer. The hospital’s institutional review board approved this study.

Interventions

The firms were randomly assigned to 1 of 4 one-hour quality-improvement training interventions delivered at the same time and day in November 2014 at each firm’s office, located on different floors of the hospital. There was virtually no cross-talk among the firms in the first year, which ensured the integrity of the cohort randomization and interventions. Faculty from an affiliated business school of the academic center worked with attending physicians to train the firms.

All interventions took 1 hour at noontime. Firm 1 (the control) received a didactic lecture on sign-out, which participants heard during orientation. Repeating that lecture reinforced their knowledge of sign-outs. Firm 2 was trained on the I-PASS mnemonic with a predictable progression of information elements to transfer.3,12 Interns role-played 3 scenarios to practice sign-out.3 They received skills feedback and a debriefing to link I-PASS with information elements to transfer. Firm 3 was dealt a policy mandate by the interns’ attending physician to perform specific tasks at sign-out. Senders were to provide the night cover with to-do tasks, and receivers were to actively discuss and verify these tasks to ensure task accountability.13 Firm 4 was trained on a Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) protocol to identify and solve perceived barriers to sign-outs. Firm 4 agreed to solve the problem of the lack of care plans by the day team to the night cover. An ad hoc team in Firm 4 refined, pilot tested, and rolled out the solution within a month. Its protocol emphasized information on anticipated changes in patient status, providing contingency plans and their rationale as well as discussions to clarify care plans. Details of the 4 interventions are shown in the Table.

Data Collection Process

Outcomes

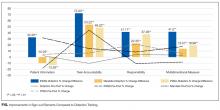

We measured improvements in sign-out quality by the mean percentage differences for each of the 3 dimensions of sign-out, as well as a multidimensional measure of sign-out comprising the 3 dimensions for each firm in 2 ways: (1) pre- and postintervention, and (2) vis-à-vis the control group postintervention.

Statistical Analysis

We factor analyzed the 17 sign-out elements using principal components analysis with varimax rotation to confirm their groupings within the 3 dimensions of sign-out using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 24 (IBM, North Castle, NY). We calculated the mean percentage differences and used Student t tests to evaluate statistical differences at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Five hundred and sixty-three patient sign-outs were observed prior to the training interventions (κ = 0.646), and 620 patient sign-outs were observed after the interventions (κ = 0.648). Kappa values derived from SPSS were within acceptable interrater agreement ranges. Factor analysis of the 17 sign-out elements yielded 3 factors that we named patient information, task accountability, and responsibility, as shown in the supporting Table.

DISCUSSION

The results indicated that after only 1 hour of training, skill-based, compliance-based, and learner-initiated sign-out training improved sign-out quality beyond knowledge-based didactics even though the number of sign-out elements taught in the latter 2 was lower than in the didactics group. Different training emphases influenced different dimensions of sign-out quality so that training interns to focus on task accountability or responsibility led to improvements in those dimensions only. The lower scores in other dimensions suggest potential risks in sign-out quality from focusing attention on 1 dimension at the expense of other dimensions. I-PASS, which covered the most sign-out elements and utilized 5 facilitators, led to the best overall improvement in sign-out quality, which is consistent with previous studies.3,12 We demonstrated that only 1 hour of training on the I-PASS mnemonics using video, role-playing, and feedback led to significant improvements. This approach is portable and easily applied to any program. Potential improvements in I-PASS training could be obtained by emphasizing task accountability and responsibility because the mandate and PDSA groups obtained higher scores than the I-PASS group in these dimensions.

Limitations

We measured sign-out quality in the evening at this site because it was at greatest risk for errors. Future studies should consider daytime sign-outs, interunit handoffs, and other hospital settings, such as community or rural hospitals and nonacute patient settings, to ascertain generalizability. Data were collected from observations, so Hawthorne effects may introduce bias. However, we believe that using a standardized checklist, a control group, and assessing relative changes minimized this risk. Although we observed almost 1200 patient sign-outs over 80 shift changes, we were not able to observe every intern in every firm. Finally, no sentinel events were reported during the study period, and we did not include other measures of clinical outcomes, which represent an opportunity for future researchers to test which specific sign-out elements or dimensions are related to clinical outcomes or are relevant to specific patient types.

CONCLUSION

The results of this study indicate that 1 hour of formal training can improve sign-out quality. Program directors should consider including I-PASS with additional focus on task accountability and personal responsibility in their sign-out training plans.

Disclosure

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Darbyshire D, Gordon M, Baker P. Teaching handover of care to medical students. Clin Teach. 2013;10:32-37. PubMed

2. Lee SH, Phan PH, Dorman T, Weaver SJ, Pronovost PJ. Handoffs, safety culture, and practices: evidence from the hospital survey on patient safety culture. BMJ Health Serv Res. 2016;16:254. DOI 10.1186/s12913-016-1502-7. PubMed

3. Starmer AJ, O’Toole JK, Rosenbluth G, et al. Development, implementation, and dissemination of the I-PASS handoff curriculum: a multisite educational intervention to improve patient handoffs. Acad Med. 2014:89:876-884. PubMed

4. Riesenberg LA, Leitzsch J, Little BW. Systematic review of handoff mnemonics literature. Am J Med Qual. 2009;24:196-204. PubMed

5. Cohen MD, Hilligoss B, Kajdacsy-Balla A. A handoff is not a telegram: an understanding of the patient is co-constructed. Crit Care. 2012;16:303. PubMed

6. McMullan A, Parush A, Momtahan K. Transferring patient care: patterns of synchronous bidisciplinary communication between physicians and nurses during handoffs in a critical care unit. J Perianesth Nurs. 2015;30:92-104. PubMed

7. Rayo MF, Mount-Campbell AF, O’Brien JM, et al. Interactive questioning in critical care during handovers: a transcript analysis of communication behaviours by physicians, nurses and nurse practitioners. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23:483-489. PubMed

8. Gordon M, Findley R. Educational interventions to improve handover in health care: a systematic review. Med Educ. 2011;45:1081-1089. PubMed

9. Nasca TJ, Day SH, Amis ES Jr; ACGME Duty Hour Task Force. The new recommendations on duty hours from the ACGME Task Force. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:e3. PubMed

10. Wohlauer MV, Arora VM, Horwitz LI, et al. The patient handoff: a comprehensive curricular blueprint for resident education to improve continuity of care. Acad Med. 2012;87:411-418. PubMed

11. Riesenberg LA, Leitzsch J, Massucci JL, et al. Residents’ and attending physicians’ handoffs: a systematic review of the literature. Acad Med. 2009;84:1775-1787. PubMed

12. Huth K, Hart F, Moreau K, et al. Real-world implementation of a standardized handover program (I-PASS) on a pediatric clinical teaching unit. Acad Ped. 2016;16:532-539. PubMed

13. Jonas E, Schulz-Hardt S, Frey D, Thelen N. Confirmation bias in sequential information search after preliminary decisions: An expansion of dissonance theoretical research on selective exposure to information. J Per Soc Psy. 2001;80:557-571. PubMed

14. Joint Commission. Improving handoff communications: Meeting national patient safety goal 2E. Jt Pers Patient Saf. 2006;6:9-15.

15. Improving Hand-off Communication. Joint Commission Resources. 2007. PubMed

Patient sign-outs are defined as the transition of patient care that includes the transfer of information, task accountability, and personal responsibility between providers.1-3 The adoption of mnemonics as a memory aid has been used to improve the transfer of patient information between providers.4 In the transfer of task accountability, providers transfer follow-up tasks to on-call or coverage providers and ensure that directives are understood. Joint task accountability is enhanced through collaborative giving and cross-checking of information received through assertive questioning to detect errors, and it also enables the receiver to codevelop an understanding of a patient’s condition.5-8 In the transfer of personal responsibility for the primary team’s patients, the provision of anticipatory guidance enables the coverage provider to have prospective information about potential, upcoming issues to facilitate care plans.6 Enabling coverage providers to anticipate overnight events helps them exercise responsibility for patients who are under their temporary care.2

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requires residency programs to provide formal instruction on sign-outs.9 Yet, variability across training programs exists,8,10 with training emphasis on the transfer of information over accountability or responsibility.11 Previous studies have demonstrated the efficacy of sign-out training, such as the illness severity, patient summary, action list, situation awareness and contingency planning, and synthesis by reviewer (I-PASS) bundle.3 Yet, participation is far from 100% because the I-PASS bundle requires in-person workshops, e-learning platforms, organizational change campaigns, and faculty participation,12 involving resource and time commitments that few programs can afford. To address this issue, we seek to compare resource-efficient, knowledge-based, skill-based, compliance-based, and learner-initiated sign-out training pedagogies. We focused on the evening sign-out because it is a high-risk period when care for inpatients is transferred to smaller coverage intern teams.

METHODS

Setting and Study Design

A prospective, randomized cohort trial of 4 training interventions was conducted at an internal medicine residency program at a Mid-Atlantic, academic, tertiary-care hospital with 1192 inpatient beds. The 52 interns admitted to the program were randomly assigned to 4 firms caring for up to 25 inpatients on each floor of the hospital. The case mix faced by each firm was similar because patients were randomly assigned to firms based on bed availability. Teams of 5 interns in each firm worked in 5-day duty cycles, during which each intern rotated as a night cover for his or her firm. Interns remain in their firm throughout their residency. Sign-outs were conducted face to face with a computer. Receivers printed sign-out sheets populated with patient information and took notes when senders communicated information from the computer. The hospital’s institutional review board approved this study.

Interventions

The firms were randomly assigned to 1 of 4 one-hour quality-improvement training interventions delivered at the same time and day in November 2014 at each firm’s office, located on different floors of the hospital. There was virtually no cross-talk among the firms in the first year, which ensured the integrity of the cohort randomization and interventions. Faculty from an affiliated business school of the academic center worked with attending physicians to train the firms.

All interventions took 1 hour at noontime. Firm 1 (the control) received a didactic lecture on sign-out, which participants heard during orientation. Repeating that lecture reinforced their knowledge of sign-outs. Firm 2 was trained on the I-PASS mnemonic with a predictable progression of information elements to transfer.3,12 Interns role-played 3 scenarios to practice sign-out.3 They received skills feedback and a debriefing to link I-PASS with information elements to transfer. Firm 3 was dealt a policy mandate by the interns’ attending physician to perform specific tasks at sign-out. Senders were to provide the night cover with to-do tasks, and receivers were to actively discuss and verify these tasks to ensure task accountability.13 Firm 4 was trained on a Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) protocol to identify and solve perceived barriers to sign-outs. Firm 4 agreed to solve the problem of the lack of care plans by the day team to the night cover. An ad hoc team in Firm 4 refined, pilot tested, and rolled out the solution within a month. Its protocol emphasized information on anticipated changes in patient status, providing contingency plans and their rationale as well as discussions to clarify care plans. Details of the 4 interventions are shown in the Table.

Data Collection Process

Outcomes

We measured improvements in sign-out quality by the mean percentage differences for each of the 3 dimensions of sign-out, as well as a multidimensional measure of sign-out comprising the 3 dimensions for each firm in 2 ways: (1) pre- and postintervention, and (2) vis-à-vis the control group postintervention.

Statistical Analysis

We factor analyzed the 17 sign-out elements using principal components analysis with varimax rotation to confirm their groupings within the 3 dimensions of sign-out using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 24 (IBM, North Castle, NY). We calculated the mean percentage differences and used Student t tests to evaluate statistical differences at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Five hundred and sixty-three patient sign-outs were observed prior to the training interventions (κ = 0.646), and 620 patient sign-outs were observed after the interventions (κ = 0.648). Kappa values derived from SPSS were within acceptable interrater agreement ranges. Factor analysis of the 17 sign-out elements yielded 3 factors that we named patient information, task accountability, and responsibility, as shown in the supporting Table.

DISCUSSION

The results indicated that after only 1 hour of training, skill-based, compliance-based, and learner-initiated sign-out training improved sign-out quality beyond knowledge-based didactics even though the number of sign-out elements taught in the latter 2 was lower than in the didactics group. Different training emphases influenced different dimensions of sign-out quality so that training interns to focus on task accountability or responsibility led to improvements in those dimensions only. The lower scores in other dimensions suggest potential risks in sign-out quality from focusing attention on 1 dimension at the expense of other dimensions. I-PASS, which covered the most sign-out elements and utilized 5 facilitators, led to the best overall improvement in sign-out quality, which is consistent with previous studies.3,12 We demonstrated that only 1 hour of training on the I-PASS mnemonics using video, role-playing, and feedback led to significant improvements. This approach is portable and easily applied to any program. Potential improvements in I-PASS training could be obtained by emphasizing task accountability and responsibility because the mandate and PDSA groups obtained higher scores than the I-PASS group in these dimensions.

Limitations

We measured sign-out quality in the evening at this site because it was at greatest risk for errors. Future studies should consider daytime sign-outs, interunit handoffs, and other hospital settings, such as community or rural hospitals and nonacute patient settings, to ascertain generalizability. Data were collected from observations, so Hawthorne effects may introduce bias. However, we believe that using a standardized checklist, a control group, and assessing relative changes minimized this risk. Although we observed almost 1200 patient sign-outs over 80 shift changes, we were not able to observe every intern in every firm. Finally, no sentinel events were reported during the study period, and we did not include other measures of clinical outcomes, which represent an opportunity for future researchers to test which specific sign-out elements or dimensions are related to clinical outcomes or are relevant to specific patient types.

CONCLUSION

The results of this study indicate that 1 hour of formal training can improve sign-out quality. Program directors should consider including I-PASS with additional focus on task accountability and personal responsibility in their sign-out training plans.

Disclosure

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Patient sign-outs are defined as the transition of patient care that includes the transfer of information, task accountability, and personal responsibility between providers.1-3 The adoption of mnemonics as a memory aid has been used to improve the transfer of patient information between providers.4 In the transfer of task accountability, providers transfer follow-up tasks to on-call or coverage providers and ensure that directives are understood. Joint task accountability is enhanced through collaborative giving and cross-checking of information received through assertive questioning to detect errors, and it also enables the receiver to codevelop an understanding of a patient’s condition.5-8 In the transfer of personal responsibility for the primary team’s patients, the provision of anticipatory guidance enables the coverage provider to have prospective information about potential, upcoming issues to facilitate care plans.6 Enabling coverage providers to anticipate overnight events helps them exercise responsibility for patients who are under their temporary care.2

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requires residency programs to provide formal instruction on sign-outs.9 Yet, variability across training programs exists,8,10 with training emphasis on the transfer of information over accountability or responsibility.11 Previous studies have demonstrated the efficacy of sign-out training, such as the illness severity, patient summary, action list, situation awareness and contingency planning, and synthesis by reviewer (I-PASS) bundle.3 Yet, participation is far from 100% because the I-PASS bundle requires in-person workshops, e-learning platforms, organizational change campaigns, and faculty participation,12 involving resource and time commitments that few programs can afford. To address this issue, we seek to compare resource-efficient, knowledge-based, skill-based, compliance-based, and learner-initiated sign-out training pedagogies. We focused on the evening sign-out because it is a high-risk period when care for inpatients is transferred to smaller coverage intern teams.

METHODS

Setting and Study Design

A prospective, randomized cohort trial of 4 training interventions was conducted at an internal medicine residency program at a Mid-Atlantic, academic, tertiary-care hospital with 1192 inpatient beds. The 52 interns admitted to the program were randomly assigned to 4 firms caring for up to 25 inpatients on each floor of the hospital. The case mix faced by each firm was similar because patients were randomly assigned to firms based on bed availability. Teams of 5 interns in each firm worked in 5-day duty cycles, during which each intern rotated as a night cover for his or her firm. Interns remain in their firm throughout their residency. Sign-outs were conducted face to face with a computer. Receivers printed sign-out sheets populated with patient information and took notes when senders communicated information from the computer. The hospital’s institutional review board approved this study.

Interventions

The firms were randomly assigned to 1 of 4 one-hour quality-improvement training interventions delivered at the same time and day in November 2014 at each firm’s office, located on different floors of the hospital. There was virtually no cross-talk among the firms in the first year, which ensured the integrity of the cohort randomization and interventions. Faculty from an affiliated business school of the academic center worked with attending physicians to train the firms.

All interventions took 1 hour at noontime. Firm 1 (the control) received a didactic lecture on sign-out, which participants heard during orientation. Repeating that lecture reinforced their knowledge of sign-outs. Firm 2 was trained on the I-PASS mnemonic with a predictable progression of information elements to transfer.3,12 Interns role-played 3 scenarios to practice sign-out.3 They received skills feedback and a debriefing to link I-PASS with information elements to transfer. Firm 3 was dealt a policy mandate by the interns’ attending physician to perform specific tasks at sign-out. Senders were to provide the night cover with to-do tasks, and receivers were to actively discuss and verify these tasks to ensure task accountability.13 Firm 4 was trained on a Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) protocol to identify and solve perceived barriers to sign-outs. Firm 4 agreed to solve the problem of the lack of care plans by the day team to the night cover. An ad hoc team in Firm 4 refined, pilot tested, and rolled out the solution within a month. Its protocol emphasized information on anticipated changes in patient status, providing contingency plans and their rationale as well as discussions to clarify care plans. Details of the 4 interventions are shown in the Table.

Data Collection Process

Outcomes

We measured improvements in sign-out quality by the mean percentage differences for each of the 3 dimensions of sign-out, as well as a multidimensional measure of sign-out comprising the 3 dimensions for each firm in 2 ways: (1) pre- and postintervention, and (2) vis-à-vis the control group postintervention.

Statistical Analysis

We factor analyzed the 17 sign-out elements using principal components analysis with varimax rotation to confirm their groupings within the 3 dimensions of sign-out using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 24 (IBM, North Castle, NY). We calculated the mean percentage differences and used Student t tests to evaluate statistical differences at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Five hundred and sixty-three patient sign-outs were observed prior to the training interventions (κ = 0.646), and 620 patient sign-outs were observed after the interventions (κ = 0.648). Kappa values derived from SPSS were within acceptable interrater agreement ranges. Factor analysis of the 17 sign-out elements yielded 3 factors that we named patient information, task accountability, and responsibility, as shown in the supporting Table.

DISCUSSION

The results indicated that after only 1 hour of training, skill-based, compliance-based, and learner-initiated sign-out training improved sign-out quality beyond knowledge-based didactics even though the number of sign-out elements taught in the latter 2 was lower than in the didactics group. Different training emphases influenced different dimensions of sign-out quality so that training interns to focus on task accountability or responsibility led to improvements in those dimensions only. The lower scores in other dimensions suggest potential risks in sign-out quality from focusing attention on 1 dimension at the expense of other dimensions. I-PASS, which covered the most sign-out elements and utilized 5 facilitators, led to the best overall improvement in sign-out quality, which is consistent with previous studies.3,12 We demonstrated that only 1 hour of training on the I-PASS mnemonics using video, role-playing, and feedback led to significant improvements. This approach is portable and easily applied to any program. Potential improvements in I-PASS training could be obtained by emphasizing task accountability and responsibility because the mandate and PDSA groups obtained higher scores than the I-PASS group in these dimensions.

Limitations

We measured sign-out quality in the evening at this site because it was at greatest risk for errors. Future studies should consider daytime sign-outs, interunit handoffs, and other hospital settings, such as community or rural hospitals and nonacute patient settings, to ascertain generalizability. Data were collected from observations, so Hawthorne effects may introduce bias. However, we believe that using a standardized checklist, a control group, and assessing relative changes minimized this risk. Although we observed almost 1200 patient sign-outs over 80 shift changes, we were not able to observe every intern in every firm. Finally, no sentinel events were reported during the study period, and we did not include other measures of clinical outcomes, which represent an opportunity for future researchers to test which specific sign-out elements or dimensions are related to clinical outcomes or are relevant to specific patient types.

CONCLUSION

The results of this study indicate that 1 hour of formal training can improve sign-out quality. Program directors should consider including I-PASS with additional focus on task accountability and personal responsibility in their sign-out training plans.

Disclosure

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Darbyshire D, Gordon M, Baker P. Teaching handover of care to medical students. Clin Teach. 2013;10:32-37. PubMed

2. Lee SH, Phan PH, Dorman T, Weaver SJ, Pronovost PJ. Handoffs, safety culture, and practices: evidence from the hospital survey on patient safety culture. BMJ Health Serv Res. 2016;16:254. DOI 10.1186/s12913-016-1502-7. PubMed

3. Starmer AJ, O’Toole JK, Rosenbluth G, et al. Development, implementation, and dissemination of the I-PASS handoff curriculum: a multisite educational intervention to improve patient handoffs. Acad Med. 2014:89:876-884. PubMed

4. Riesenberg LA, Leitzsch J, Little BW. Systematic review of handoff mnemonics literature. Am J Med Qual. 2009;24:196-204. PubMed

5. Cohen MD, Hilligoss B, Kajdacsy-Balla A. A handoff is not a telegram: an understanding of the patient is co-constructed. Crit Care. 2012;16:303. PubMed

6. McMullan A, Parush A, Momtahan K. Transferring patient care: patterns of synchronous bidisciplinary communication between physicians and nurses during handoffs in a critical care unit. J Perianesth Nurs. 2015;30:92-104. PubMed

7. Rayo MF, Mount-Campbell AF, O’Brien JM, et al. Interactive questioning in critical care during handovers: a transcript analysis of communication behaviours by physicians, nurses and nurse practitioners. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23:483-489. PubMed

8. Gordon M, Findley R. Educational interventions to improve handover in health care: a systematic review. Med Educ. 2011;45:1081-1089. PubMed

9. Nasca TJ, Day SH, Amis ES Jr; ACGME Duty Hour Task Force. The new recommendations on duty hours from the ACGME Task Force. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:e3. PubMed

10. Wohlauer MV, Arora VM, Horwitz LI, et al. The patient handoff: a comprehensive curricular blueprint for resident education to improve continuity of care. Acad Med. 2012;87:411-418. PubMed

11. Riesenberg LA, Leitzsch J, Massucci JL, et al. Residents’ and attending physicians’ handoffs: a systematic review of the literature. Acad Med. 2009;84:1775-1787. PubMed

12. Huth K, Hart F, Moreau K, et al. Real-world implementation of a standardized handover program (I-PASS) on a pediatric clinical teaching unit. Acad Ped. 2016;16:532-539. PubMed

13. Jonas E, Schulz-Hardt S, Frey D, Thelen N. Confirmation bias in sequential information search after preliminary decisions: An expansion of dissonance theoretical research on selective exposure to information. J Per Soc Psy. 2001;80:557-571. PubMed

14. Joint Commission. Improving handoff communications: Meeting national patient safety goal 2E. Jt Pers Patient Saf. 2006;6:9-15.

15. Improving Hand-off Communication. Joint Commission Resources. 2007. PubMed

1. Darbyshire D, Gordon M, Baker P. Teaching handover of care to medical students. Clin Teach. 2013;10:32-37. PubMed

2. Lee SH, Phan PH, Dorman T, Weaver SJ, Pronovost PJ. Handoffs, safety culture, and practices: evidence from the hospital survey on patient safety culture. BMJ Health Serv Res. 2016;16:254. DOI 10.1186/s12913-016-1502-7. PubMed

3. Starmer AJ, O’Toole JK, Rosenbluth G, et al. Development, implementation, and dissemination of the I-PASS handoff curriculum: a multisite educational intervention to improve patient handoffs. Acad Med. 2014:89:876-884. PubMed

4. Riesenberg LA, Leitzsch J, Little BW. Systematic review of handoff mnemonics literature. Am J Med Qual. 2009;24:196-204. PubMed

5. Cohen MD, Hilligoss B, Kajdacsy-Balla A. A handoff is not a telegram: an understanding of the patient is co-constructed. Crit Care. 2012;16:303. PubMed

6. McMullan A, Parush A, Momtahan K. Transferring patient care: patterns of synchronous bidisciplinary communication between physicians and nurses during handoffs in a critical care unit. J Perianesth Nurs. 2015;30:92-104. PubMed

7. Rayo MF, Mount-Campbell AF, O’Brien JM, et al. Interactive questioning in critical care during handovers: a transcript analysis of communication behaviours by physicians, nurses and nurse practitioners. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23:483-489. PubMed

8. Gordon M, Findley R. Educational interventions to improve handover in health care: a systematic review. Med Educ. 2011;45:1081-1089. PubMed

9. Nasca TJ, Day SH, Amis ES Jr; ACGME Duty Hour Task Force. The new recommendations on duty hours from the ACGME Task Force. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:e3. PubMed

10. Wohlauer MV, Arora VM, Horwitz LI, et al. The patient handoff: a comprehensive curricular blueprint for resident education to improve continuity of care. Acad Med. 2012;87:411-418. PubMed

11. Riesenberg LA, Leitzsch J, Massucci JL, et al. Residents’ and attending physicians’ handoffs: a systematic review of the literature. Acad Med. 2009;84:1775-1787. PubMed

12. Huth K, Hart F, Moreau K, et al. Real-world implementation of a standardized handover program (I-PASS) on a pediatric clinical teaching unit. Acad Ped. 2016;16:532-539. PubMed

13. Jonas E, Schulz-Hardt S, Frey D, Thelen N. Confirmation bias in sequential information search after preliminary decisions: An expansion of dissonance theoretical research on selective exposure to information. J Per Soc Psy. 2001;80:557-571. PubMed

14. Joint Commission. Improving handoff communications: Meeting national patient safety goal 2E. Jt Pers Patient Saf. 2006;6:9-15.

15. Improving Hand-off Communication. Joint Commission Resources. 2007. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Primary Care Provider Preferences for Communication with Inpatient Teams: One Size Does Not Fit All

As the hospitalist’s role in medicine grows, the transition of care from inpatient to primary care providers (PCPs, including primary care physicians, nurse practitioners, or physician assistants), becomes increasingly important. Inadequate communication at this transition is associated with preventable adverse events leading to rehospitalization, disability, and death.1-

Providing PCPs access to the inpatient electronic health record (EHR) may reduce the need for active communication. However, a recent survey of PCPs in the general internal medicine division of an academic hospital found a strong preference for additional communication with inpatient providers, despite a shared EHR.5

We examined communication preferences of general internal medicine PCPs at a different academic institution and extended our study to include community-based PCPs who were both affiliated and unaffiliated with the institution.

METHODS

Between October 2015 and June 2016, we surveyed PCPs from 3 practice groups with institutional affiliation or proximity to The Johns Hopkins Hospital: all general internal medicine faculty with outpatient practices (“academic,” 2 practice sites, n = 35), all community-based PCPs affiliated with the health system (“community,” 36 practice sites, n = 220), and all PCPs from an unaffiliated managed care organization (“unaffiliated,” 5 practice sites ranging from 0.3 to 4 miles from The Johns Hopkins Hospital, n = 29).

All groups have work-sponsored e-mail services. At the time of the survey, both the academic and community groups used an EHR that allowed access to inpatient laboratory and radiology data and discharge summaries. The unaffiliated group used paper health records. The hospital faxes discharge summaries to all PCPs who are identified by patients.

The investigators and representatives from each practice group collaborated to develop 15 questions with mutually exclusive answers to evaluate PCP experiences with and preferences for communication with inpatient teams. The survey was constructed and administered through Qualtrics’ online platform (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) and distributed via e-mail. The study was reviewed and acknowledged by the Johns Hopkins institutional review board as quality improvement activity.

The survey contained branching logic. Only respondents who indicated preference for communication received questions regarding preferred mode of communication. We used the preferred mode of communication for initial contact from the inpatient team in our analysis. χ2 and Fischer’s exact tests were performed with JMP 12 software (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Fourteen (40%) academic, 43 (14%) community, and 16 (55%) unaffiliated PCPs completed the survey, for 73 total responses from 284 surveys distributed (26%).

Among the 73 responding PCPs, 31 (42%) reported receiving notification of admission during “every” or “almost every” hospitalization, with no significant variation across practice groups (P = 0.5).

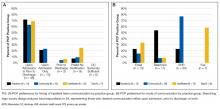

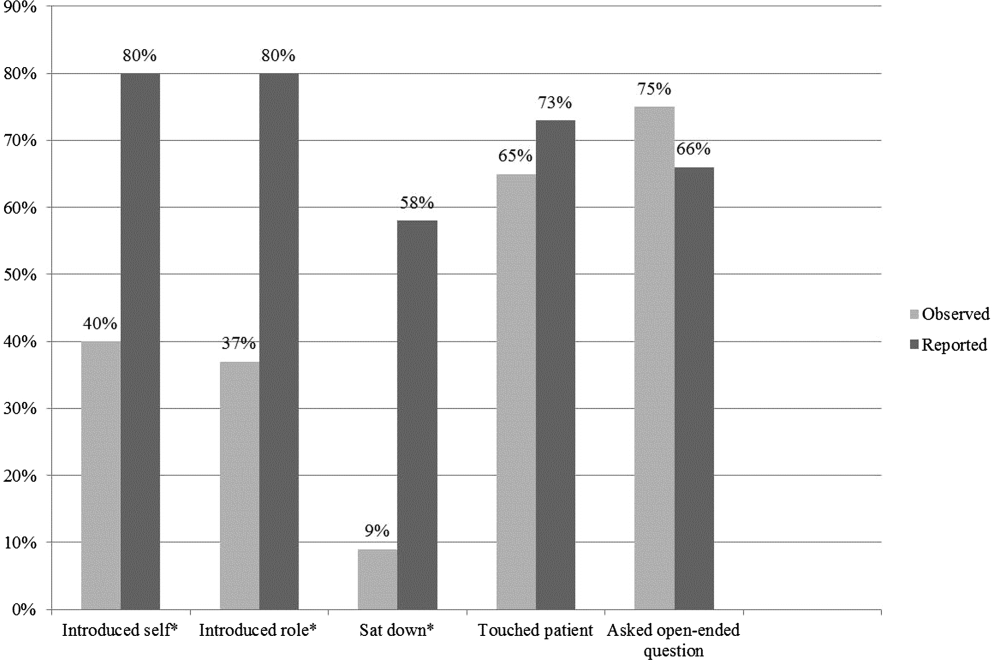

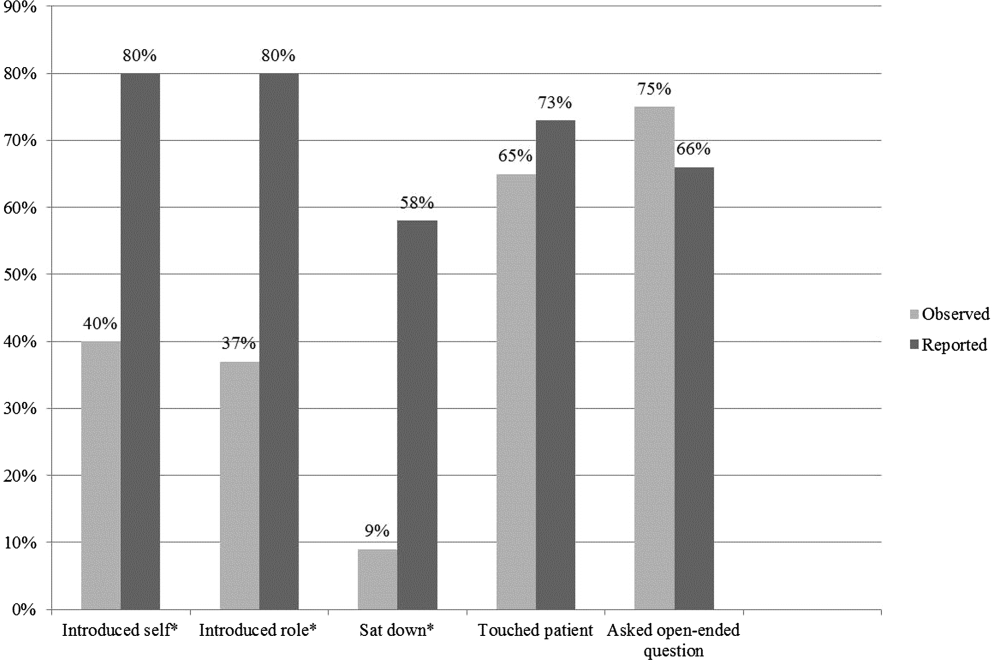

Across all groups, 64 PCPs (88%) preferred communication at 1 or more points during hospitalizations (panel A of Figure). “Both upon admission and prior to discharge” was selected most frequently, and there were no differences between practice groups (P = 0.2).

Preferred mode of communication, however, differed significantly between groups (panel B of Figure). The academic group had a greater preference for telephone (54%) than the community (8%; P < 0.001) and unaffiliated groups (8%; P < 0.001), the community group a greater preference for EHR (77%) than the academic (23%; P = 0.002) and unaffiliated groups (0%; P < 0.001), and the unaffiliated group a greater preference for fax (58%) than the other groups (both 0%; P < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

Our findings add to previous evidence of low rates of communication between inpatient providers and PCPs6 and a preference from PCPs for communication during hospitalizations despite shared EHRs.5 We extend previous work by demonstrating that PCP preferences for mode of communication vary by practice setting. Our findings lead us to hypothesize that identifying and incorporating PCP preferences may improve communication, though at the potential expense of standardization and efficiency.

There may be several reasons for the differing communication preferences observed. Most academic PCPs are located near or have admitting privileges to the hospital and are not in clinic full time. Their preference for the telephone may thus result from interpersonal relationships born from proximity and greater availability for telephone calls, or reduced fluency with the EHR compared to full-time community clinicians.

The unaffiliated group’s preference for fax may reflect a desire for communication that integrates easily with paper charts and is least disruptive to workflow, or concerns about health information confidentiality in e-mails.

Our study’s generalizability is limited by a low response rate, though it is comparable to prior studies.7 The unaffiliated group was accessed by convenience (acquaintance with the medical director); however, we note it had the highest response rate (55%).

In summary, we found low rates of communication between inpatient providers and PCPs, despite a strong preference from most PCPs for such communication during hospitalizations. PCPs’ preferred mode of communication differed based on practice setting. Addressing PCP communication preferences may be important to future care transition interventions.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

1. Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161-174. PubMed

2. Moore C, Wisnivesky J, Williams S, McGinn T. Medical errors related to discontinuity of care from an inpatient to an outpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(8):646-651. PubMed

3. van Walraven C, Mamdani M, Fang J, Austin PC. Continuity of care and patient outcomes after hospital discharge. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(6):624-631. PubMed

4. Snow V, Beck D, Budnitz T, et al. Transitions of Care Consensus policy statement: American College of Physicians, Society of General Internal Medicine, Society of Hospital Medicine, American Geriatrics Society, American College Of Emergency Physicians, and Society for Academic Emergency M. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(6):364-370. PubMed

5. Sheu L, Fung K, Mourad M, Ranji S, Wu E. We need to talk: Primary care provider communication at discharge in the era of a shared electronic medical record. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(5):307-310. PubMed

6. Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831-841. PubMed

7. Pantilat SZ, Lindenauer PK, Katz PP, Wachter RM. Primary care physician attitudes regarding communication with hospitalists. Am J Med. 2001(9B);111:15-20. PubMed

As the hospitalist’s role in medicine grows, the transition of care from inpatient to primary care providers (PCPs, including primary care physicians, nurse practitioners, or physician assistants), becomes increasingly important. Inadequate communication at this transition is associated with preventable adverse events leading to rehospitalization, disability, and death.1-

Providing PCPs access to the inpatient electronic health record (EHR) may reduce the need for active communication. However, a recent survey of PCPs in the general internal medicine division of an academic hospital found a strong preference for additional communication with inpatient providers, despite a shared EHR.5

We examined communication preferences of general internal medicine PCPs at a different academic institution and extended our study to include community-based PCPs who were both affiliated and unaffiliated with the institution.

METHODS

Between October 2015 and June 2016, we surveyed PCPs from 3 practice groups with institutional affiliation or proximity to The Johns Hopkins Hospital: all general internal medicine faculty with outpatient practices (“academic,” 2 practice sites, n = 35), all community-based PCPs affiliated with the health system (“community,” 36 practice sites, n = 220), and all PCPs from an unaffiliated managed care organization (“unaffiliated,” 5 practice sites ranging from 0.3 to 4 miles from The Johns Hopkins Hospital, n = 29).

All groups have work-sponsored e-mail services. At the time of the survey, both the academic and community groups used an EHR that allowed access to inpatient laboratory and radiology data and discharge summaries. The unaffiliated group used paper health records. The hospital faxes discharge summaries to all PCPs who are identified by patients.

The investigators and representatives from each practice group collaborated to develop 15 questions with mutually exclusive answers to evaluate PCP experiences with and preferences for communication with inpatient teams. The survey was constructed and administered through Qualtrics’ online platform (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) and distributed via e-mail. The study was reviewed and acknowledged by the Johns Hopkins institutional review board as quality improvement activity.

The survey contained branching logic. Only respondents who indicated preference for communication received questions regarding preferred mode of communication. We used the preferred mode of communication for initial contact from the inpatient team in our analysis. χ2 and Fischer’s exact tests were performed with JMP 12 software (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Fourteen (40%) academic, 43 (14%) community, and 16 (55%) unaffiliated PCPs completed the survey, for 73 total responses from 284 surveys distributed (26%).

Among the 73 responding PCPs, 31 (42%) reported receiving notification of admission during “every” or “almost every” hospitalization, with no significant variation across practice groups (P = 0.5).

Across all groups, 64 PCPs (88%) preferred communication at 1 or more points during hospitalizations (panel A of Figure). “Both upon admission and prior to discharge” was selected most frequently, and there were no differences between practice groups (P = 0.2).

Preferred mode of communication, however, differed significantly between groups (panel B of Figure). The academic group had a greater preference for telephone (54%) than the community (8%; P < 0.001) and unaffiliated groups (8%; P < 0.001), the community group a greater preference for EHR (77%) than the academic (23%; P = 0.002) and unaffiliated groups (0%; P < 0.001), and the unaffiliated group a greater preference for fax (58%) than the other groups (both 0%; P < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

Our findings add to previous evidence of low rates of communication between inpatient providers and PCPs6 and a preference from PCPs for communication during hospitalizations despite shared EHRs.5 We extend previous work by demonstrating that PCP preferences for mode of communication vary by practice setting. Our findings lead us to hypothesize that identifying and incorporating PCP preferences may improve communication, though at the potential expense of standardization and efficiency.

There may be several reasons for the differing communication preferences observed. Most academic PCPs are located near or have admitting privileges to the hospital and are not in clinic full time. Their preference for the telephone may thus result from interpersonal relationships born from proximity and greater availability for telephone calls, or reduced fluency with the EHR compared to full-time community clinicians.

The unaffiliated group’s preference for fax may reflect a desire for communication that integrates easily with paper charts and is least disruptive to workflow, or concerns about health information confidentiality in e-mails.

Our study’s generalizability is limited by a low response rate, though it is comparable to prior studies.7 The unaffiliated group was accessed by convenience (acquaintance with the medical director); however, we note it had the highest response rate (55%).

In summary, we found low rates of communication between inpatient providers and PCPs, despite a strong preference from most PCPs for such communication during hospitalizations. PCPs’ preferred mode of communication differed based on practice setting. Addressing PCP communication preferences may be important to future care transition interventions.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

As the hospitalist’s role in medicine grows, the transition of care from inpatient to primary care providers (PCPs, including primary care physicians, nurse practitioners, or physician assistants), becomes increasingly important. Inadequate communication at this transition is associated with preventable adverse events leading to rehospitalization, disability, and death.1-

Providing PCPs access to the inpatient electronic health record (EHR) may reduce the need for active communication. However, a recent survey of PCPs in the general internal medicine division of an academic hospital found a strong preference for additional communication with inpatient providers, despite a shared EHR.5

We examined communication preferences of general internal medicine PCPs at a different academic institution and extended our study to include community-based PCPs who were both affiliated and unaffiliated with the institution.

METHODS

Between October 2015 and June 2016, we surveyed PCPs from 3 practice groups with institutional affiliation or proximity to The Johns Hopkins Hospital: all general internal medicine faculty with outpatient practices (“academic,” 2 practice sites, n = 35), all community-based PCPs affiliated with the health system (“community,” 36 practice sites, n = 220), and all PCPs from an unaffiliated managed care organization (“unaffiliated,” 5 practice sites ranging from 0.3 to 4 miles from The Johns Hopkins Hospital, n = 29).

All groups have work-sponsored e-mail services. At the time of the survey, both the academic and community groups used an EHR that allowed access to inpatient laboratory and radiology data and discharge summaries. The unaffiliated group used paper health records. The hospital faxes discharge summaries to all PCPs who are identified by patients.

The investigators and representatives from each practice group collaborated to develop 15 questions with mutually exclusive answers to evaluate PCP experiences with and preferences for communication with inpatient teams. The survey was constructed and administered through Qualtrics’ online platform (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) and distributed via e-mail. The study was reviewed and acknowledged by the Johns Hopkins institutional review board as quality improvement activity.

The survey contained branching logic. Only respondents who indicated preference for communication received questions regarding preferred mode of communication. We used the preferred mode of communication for initial contact from the inpatient team in our analysis. χ2 and Fischer’s exact tests were performed with JMP 12 software (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Fourteen (40%) academic, 43 (14%) community, and 16 (55%) unaffiliated PCPs completed the survey, for 73 total responses from 284 surveys distributed (26%).

Among the 73 responding PCPs, 31 (42%) reported receiving notification of admission during “every” or “almost every” hospitalization, with no significant variation across practice groups (P = 0.5).

Across all groups, 64 PCPs (88%) preferred communication at 1 or more points during hospitalizations (panel A of Figure). “Both upon admission and prior to discharge” was selected most frequently, and there were no differences between practice groups (P = 0.2).

Preferred mode of communication, however, differed significantly between groups (panel B of Figure). The academic group had a greater preference for telephone (54%) than the community (8%; P < 0.001) and unaffiliated groups (8%; P < 0.001), the community group a greater preference for EHR (77%) than the academic (23%; P = 0.002) and unaffiliated groups (0%; P < 0.001), and the unaffiliated group a greater preference for fax (58%) than the other groups (both 0%; P < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

Our findings add to previous evidence of low rates of communication between inpatient providers and PCPs6 and a preference from PCPs for communication during hospitalizations despite shared EHRs.5 We extend previous work by demonstrating that PCP preferences for mode of communication vary by practice setting. Our findings lead us to hypothesize that identifying and incorporating PCP preferences may improve communication, though at the potential expense of standardization and efficiency.

There may be several reasons for the differing communication preferences observed. Most academic PCPs are located near or have admitting privileges to the hospital and are not in clinic full time. Their preference for the telephone may thus result from interpersonal relationships born from proximity and greater availability for telephone calls, or reduced fluency with the EHR compared to full-time community clinicians.

The unaffiliated group’s preference for fax may reflect a desire for communication that integrates easily with paper charts and is least disruptive to workflow, or concerns about health information confidentiality in e-mails.

Our study’s generalizability is limited by a low response rate, though it is comparable to prior studies.7 The unaffiliated group was accessed by convenience (acquaintance with the medical director); however, we note it had the highest response rate (55%).

In summary, we found low rates of communication between inpatient providers and PCPs, despite a strong preference from most PCPs for such communication during hospitalizations. PCPs’ preferred mode of communication differed based on practice setting. Addressing PCP communication preferences may be important to future care transition interventions.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

1. Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161-174. PubMed

2. Moore C, Wisnivesky J, Williams S, McGinn T. Medical errors related to discontinuity of care from an inpatient to an outpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(8):646-651. PubMed

3. van Walraven C, Mamdani M, Fang J, Austin PC. Continuity of care and patient outcomes after hospital discharge. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(6):624-631. PubMed

4. Snow V, Beck D, Budnitz T, et al. Transitions of Care Consensus policy statement: American College of Physicians, Society of General Internal Medicine, Society of Hospital Medicine, American Geriatrics Society, American College Of Emergency Physicians, and Society for Academic Emergency M. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(6):364-370. PubMed

5. Sheu L, Fung K, Mourad M, Ranji S, Wu E. We need to talk: Primary care provider communication at discharge in the era of a shared electronic medical record. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(5):307-310. PubMed

6. Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831-841. PubMed

7. Pantilat SZ, Lindenauer PK, Katz PP, Wachter RM. Primary care physician attitudes regarding communication with hospitalists. Am J Med. 2001(9B);111:15-20. PubMed

1. Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161-174. PubMed

2. Moore C, Wisnivesky J, Williams S, McGinn T. Medical errors related to discontinuity of care from an inpatient to an outpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(8):646-651. PubMed

3. van Walraven C, Mamdani M, Fang J, Austin PC. Continuity of care and patient outcomes after hospital discharge. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(6):624-631. PubMed

4. Snow V, Beck D, Budnitz T, et al. Transitions of Care Consensus policy statement: American College of Physicians, Society of General Internal Medicine, Society of Hospital Medicine, American Geriatrics Society, American College Of Emergency Physicians, and Society for Academic Emergency M. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(6):364-370. PubMed

5. Sheu L, Fung K, Mourad M, Ranji S, Wu E. We need to talk: Primary care provider communication at discharge in the era of a shared electronic medical record. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(5):307-310. PubMed

6. Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831-841. PubMed

7. Pantilat SZ, Lindenauer PK, Katz PP, Wachter RM. Primary care physician attitudes regarding communication with hospitalists. Am J Med. 2001(9B);111:15-20. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

sberry8@jhmi.edu

Outcomes after 2011 Residency Reform

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Common Program Requirements implemented in July 2011 increased supervision requirements and limited continuous work hours for first‐year residents.[1] Similar to the 2003 mandates, these requirements were introduced to improve patient safety and education at academic medical centers.[2] Work‐hour reforms have been associated with decreased resident burnout and improved sleep.[3, 4, 5] However, national observational studies and systematic reviews of the impact of the 2003 reforms on patient safety and quality of care have been varied in terms of outcome.[6, 7, 8, 9, 10] Small studies of the 2011 recommendations have shown increased sleep duration and decreased burnout, but also an increased number of handoffs and increased resident concerns about making a serious medical error.[11, 12, 13, 14] Although national surveys of residents and program directors have not indicated improvements in education or quality of life, 1 observational study did show improvement in clinical exposure and conference attendance.[15, 16, 17, 18] The impact of the 2011 reforms on patient safety remains unclear.[19, 20]

The objective of this study was to evaluate the association between implementation of the 2011 residency work‐hour mandates and patient safety outcomes at a large academic medical center.

METHODS

Study Design

This observational study used a quasi‐experimental difference‐in‐differences approach to evaluate whether residency work‐hour changes were associated with patient safety outcomes among general medicine inpatients. We compared safety outcomes among adult patients discharged from resident general medical services (referred to as resident) to safety outcomes among patients discharged by the hospitalist general medical service (referred to as hospitalist) before and after the 2011 residency work‐hour reforms at a large academic medical center. Differences in outcomes for the resident group were compared to differences observed in the hospitalist group, with adjustment for relevant demographic and case mix factors.[21] We used the hospitalist service as a control group, because ACGME changes applied only to resident services. The strength of this design is that it controls for secular trends that are correlated with patient safety, impacting both residents and hospitalists similarly.[9]

Approval for this study and a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act waiver were granted by the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine institutional review board. We retrospectively examined administrative data on all patient discharges from the general medicine services at Johns Hopkins Hospital between July 1, 2008 and June 30, 2012 that were identified as pertaining to resident or hospitalist services.

Patient Allocation and Physician Scheduling

Patient admission to the resident or hospitalist service was decided by a number of factors. To maintain continuity of care, patients were preferentially admitted to the same service as for prior admissions. New patients were admitted to a service based on bed availability, nurse staffing, patient gender, isolation precautions, and cardiac monitor availability.

The inpatient resident services were staffed prior to July 2011 using a traditional 30‐hour overnight call system. Following July 2011, the inpatient resident services were staffed using a modified overnight call system, in which interns took overnight calls from 8 pm until 12 pm the following day, once every 5 nights with supervision by upper‐level residents. These interns rotated through daytime admitting and coverage roles on the intervening days. The hospitalist service was organized into a 3‐physician rotation of day shift, evening shift, and overnight shift.

Data and Outcomes

Twenty‐nine percent of patients in the sample were admitted more than once during the study period, and patients were generally admitted to the same resident team during each admission. Patients with multiple admissions were counted multiple times in the model. We categorized admissions as prereform (July 1, 2008June 30, 2011) and postreform (July 1, 2011June 30, 2012). Outcomes evaluated included hospital length of stay, 30‐day readmission, intensive care unit stay (ICU) stay, inpatient mortality, and number of Maryland Hospital Acquired Conditions (MHACs). ICU stay pertained to any ICU admission including initial admission and transfer from the inpatient floor. MHACs are a set of inpatient performance indicators derived from a list of 64 inpatient Potentially Preventable Complications developed by 3M Health Information Systems.[22] MHACs are used by the Maryland Health Services Cost Review Commission to link hospital payment to performance for costly, preventable, and clinically relevant complications. MHACs were coded in our analysis as a dichotomous variable. Independent variables included patient age at admission, race, gender, and case mix index. Case mix index (CMI) is a numeric score that measures resource utilization for a specific patient population. CMI is a weighted value assigned to patients based on resource utilization and All Patient Refined Diagnostic Related Group and was included as an indicator of patient illness severity and risk of mortality.[23] Data were obtained from administrative records from the case mix research team at Johns Hopkins Medicine.

To account for transitional differences that may have coincided with the opening of a new hospital wing in late April 2012, we conducted a sensitivity analysis, in which we excluded from analysis any visits that took place in May 2012 to June 2012.

Data Analysis

Based on historical studies, we calculated that a sample size of at least 3600 discharges would allow us to detect a difference of 5% between the pre‐ and postreform period assuming baseline 20% occurrence of dichotomous outcomes (=0.05; =0.2; r=4).[21]

The primary unit of analysis was the hospital discharge. Similar to Horwitz et al., we analyzed data using a difference‐in‐differences estimation strategy.[21] We used multivariable linear regression for length of stay measured as a continuous variable, and multivariable logistic regression for inpatient mortality, 30‐day readmission, MHACs coded as a dichotomous variable, and ICU stay coded as a dichotomous variable.[9] The difference‐in‐differences estimation was used to determine whether the postreform period relative to prereform period was associated with differences in outcomes comparing resident and hospitalist services. In the regression models, the independent variables of interest included an indicator variable for whether a patient was treated on a resident service, an indicator variable for whether a patient was discharged in the postreform period, and the interaction of these 2 variables (resident*postreform). The interaction term can be interpreted as a differential change over time comparing resident and hospitalist services. In all models, we adjusted for patient age, gender, race, and case mix index.

To determine whether prereform trends were similar among the resident and hospitalist services, we performed a test of controls as described by Volpp and colleagues.[6] Interaction terms for resident service and prereform years 2010 and 2011 were added to the model. A Wald test was then used to test for improved model fit, which would indicate differential trends among resident and hospitalist services during the prereform period. Where such trends were found, postreform results were compared only to 2011 rather than the 2009 to 2011 prereform period.[6]

To account for correlation within patients who had multiple discharges, we used a clustering approach and estimated robust variances.[24] From the regression model results, we calculated predicted probabilities adjusted for relevant covariates and prepost differences, and used linear probability models to estimate percentage‐point differences in outcomes, comparing residents and hospitalists in the pre‐ and postreform periods.[25] All analyses were performed using Stata/IC version 11 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

In the 3 years before the 2011 residency work‐hour reforms were implemented (prereform), there were a total of 15,688 discharges for 8983 patients to the resident services and 4622 discharges for 3649 patients to the hospitalist services. In the year following implementation of residency work‐hour changes (postreform), there were 5253 discharges for 3805 patients to the resident services and 1767 discharges for 1454 patients to the hospitalist service. Table 1 shows the characteristics of patients discharged from the resident and hospitalist services in the pre‐ and postreform periods. Patients discharged from the resident services were more likely to be older, male, African American, and have a higher CMI.

| Resident Services | Hospitalist Service | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | P Valuea | |

| |||||||||

| Discharges, n | 5345 | 5299 | 5044 | 5253 | 1366 | 1492 | 1764 | 1767 | |

| Unique patients, n | 3082 | 2968 | 2933 | 3805 | 1106 | 1180 | 1363 | 1454 | |

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 55.1 (17.7) | 55.7 (17.4) | 56.4 (17.9) | 56.7 (17.1) | 55.9 (17.9) | 56.2 (18.4) | 55.5 (18.8) | 54 (18.7) | 0.02 |

| Sex male, n (%) | 1503 (48.8) | 1397 (47.1) | 1432 (48.8) | 1837 (48.3) | 520 (47) | 550 (46.6) | 613 (45) | 654 (45) | <0.01 |

| Race | |||||||||

| African American, n (%) | 2072 (67.2) | 1922 (64.8) | 1820 (62.1) | 2507 (65.9) | 500 (45.2) | 592 (50.2) | 652 (47.8) | 747 (51.4) | <0.01 |

| White, n (%) | 897 (29.1) | 892 (30.1) | 957 (32.6) | 1118 (29.4) | 534 (48.3) | 527 (44.7) | 621 (45.6) | 619 (42.6) | |

| Asian, n (%) | 19 (.6%) | 35 (1.2) | 28 (1) | 32 (.8) | 11 (1) | 7 (.6) | 25 (1.8) | 12 (.8) | |

| Other, n (%) | 94 (3.1) | 119 (4) | 128 (4.4) | 148 (3.9) | 61 (5.5) | 54 (4.6) | 65 (4.8) | 76 (5.2) | |

| Case mix index, mean (SD) | 1.2 (1) | 1.1 (0.9) | 1.1 (0.9) | 1.1 (1.2) | 1.2 (1) | 1.1 (1) | 1.1 (1) | 1 (0.7) | <0.01 |

Differences in Outcomes Among Resident and Hospitalist Services Pre‐ and Postreform

Table 2 shows unadjusted results. Patients discharged from the resident services in the postreform period as compared to the prereform period had a higher likelihood of an ICU stay (5.9% vs 4.5%, P<0.01), and lower likelihood of 30‐day readmission (17.1% vs 20.1%, P<0.01). Patients discharged from the hospitalist service in the postreform period as compared to the prereform period had a significantly shorter mean length of stay (4.51 vs 4.88 days, P=0.03)

| Resident Services | Hospitalist Service | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Prereforma | Postreform | P Value | Prereforma | Postreform | P Value |

| ||||||

| Length of stay (mean) | 4.55 (5.39) | 4.50 (5.47) | 0.61 | 4.88 (5.36) | 4.51 (4.64) | 0.03 |

| Any ICU stay (%) | 225 (4.5%) | 310 (5.9%) | <0.01 | 82 (4.7%) | 83 (4.7%) | 0.95 |

| Any MHACs (%) | 560 (3.6%) | 180 (3.4%) | 0.62 | 210 (4.5%) | 64 (3.6%) | 0.09 |

| Readmit in 30 days (%) | 3155 (20.1%) | 900 (17.1%) | <0.01 | 852 (18.4%) | 296 (16.8%) | 0.11 |

| Inpatient mortality (%) | 71 (0.5%) | 28 (0.5%) | 0.48 | 18 (0.4%) | 7 (0.4%) | 0.97 |

Table 3 presents the results of regression analyses examining correlates of patient safety outcomes, adjusted for age, gender, race, and CMI. As the test of controls indicated differential prereform trends for ICU admission and length of stay, the prereform period was limited to 2011 for these outcomes. After adjustment for covariates, the probability of an ICU stay remained greater, and the 30‐day readmission rate was lower among patients discharged from resident services in the postreform period than the prereform period. Among patients discharged from the hospitalist services, there were no significant differences in length of stay, readmissions, ICU admissions, MHACs, or inpatient mortality comparing the pre‐ and postreform periods.

| Resident Services | Hospitalist Service | Difference in Differences | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Prereforma | Postreform | Difference | Prereform | Postreform | Difference | (ResidentHospitalist) |

| |||||||

| ICU stay | 4.5% (4.0% to 5.1%) | 5.7% (5.1% to 6.3%) | 1.4% (0.5% to 2.2%) | 4.4% (3.5% to 5.3%) | 5.3% (4.3% to 6.3%) | 1.1% (0.2 to 2.4%) | 0.3% (1.1% to 1.8%) |

| Inpatient mortality | 0.5% (0.4% to 0.6%) | 0.5% (0.3% to 0.7%) | 0 (0.2% to 0.2%) | 0.3% (0.2% to 0.6%) | 0.5% (0.1% to 0.8%) | 0.1% (0.3% to 0.5%) | 0.1% (0.5% to 0.3%) |

| MHACs | 3.6% (3.3% to 3.9%) | 3.3% (2.9% to 3.7%) | 0.4% (0.9 to 0.2%) | 4.5% (3.9% to 5.1%) | 4.1% (3.2% to 5.1%) | 0.3% (1.4% to 0.7%) | 0.2% (1.0% to 1.3%) |

| Readmit 30 days | 20.1% (19.1% to 21.1%) | 17.2% (15.9% to 18.5%) | 2.8% (4.3% to 1.3%) | 18.4% (16.5% to 20.2%) | 16.6% (14.7% to 18.5%) | 1.7% (4.1% to 0.8%) | 1.8% (0.2% to 3.7%) |

| Length of stay | 4.6 (4.4 to 4.7) | 4.4 (4.3 to 4.6) | 0.1 (0.3 to 0.1) | 4.9 (4.6 to 5.1) | 4.7 (4.5 to 5.0) | 0.1 (0.4 to 0.2) | 0.01 (0.37 to 0.34) |

Differences in Outcomes Comparing Resident and Hospitalist Services Pre‐ and Postreform

Comparing pre‐ and postreform periods in the resident and hospitalist services, there were no significant differences in ICU admission, length of stay, MHACs, 30‐day readmissions, or inpatient mortality. In the sensitivity analysis, in which we excluded all discharges in May 2012 to June 2012, results were not significantly different for any of the outcomes examined.

DISCUSSION

Using difference‐in‐differences estimation, we evaluated whether the implementation of the 2011 residency work‐hour mandate was associated with differences in patient safety outcomes including length of stay, 30‐day readmission, inpatient mortality, MHACs, and ICU admissions comparing resident and hospitalist services at a large academic medical center. Adjusting for patient age, race, gender, and clinical complexity, we found no significant changes in any of the patient safety outcomes indicators in the postreform period comparing resident to hospitalist services.

Our quasiexperimental study design allowed us to gauge differences in patient safety outcomes, while reducing bias due to unmeasured confounders that might impact patient safety indicators.[9] We were able to examine all discharges from the resident and hospitalist general medicine services during the academic years 2009 to 2012, while adjusting for age, race, gender, and clinical complexity. Though ICU admission was higher and readmission rates were lower on the resident services post‐2011, we did not observe a significant difference in ICU admission or 30‐day readmission rates in the postreform period comparing patients discharged from the resident and hospitalist services and all patients in the prereform period.

Our neutral findings differ from some other single‐institution evaluations of reduced resident work hours, several of which have shown improved quality of life, education, and patient safety indicators.[18, 21, 26, 27, 28] It is unclear why improvements in patient safety were not identified in the current study. The 2011 reforms were more broad‐based than some of the preliminary studies of reduced work hours, and therefore additional variables may be at play. For instance, challenges related to decreased work hours, including the increased number of handoffs in care and work compression, may require specific interventions to produce sustained improvements in patient safety.[3, 14, 29, 30]

Improving patient safety requires more than changing resident work hours. Blum et al. recommended enhanced funding to increase supervision, decrease resident caseload, and incentivize achievement of quality indicators to achieve the goal of improved patient safety within work‐hour reform.[31] Schumacher et al. proposed a focus on supervision, professionalism, safe transitions of care, and optimizing workloads as a means to improve patient safety and education within the new residency training paradigm.[29]

Limitations of this study include limited follow‐up time after implementation of the work‐hour reforms. It may take more time to optimize systems of care to see benefits in patient safety indicators. This was a single‐institution study of a limited number of outcomes in a single department, which limits generalizability and may reflect local experience rather than broader trends. The call schedule on the resident service in this study differs from programs that have adopted night float schedules. [27] This may have had an effect on patient care outcomes.[32] In an attempt to conduct a timely study of inpatient safety indicators following the 2011 changes, our study was not powered to detect small changes in low‐frequency outcomes such as mortality; longer‐term studies at multiple institutions will be needed to answer these key questions. We limited the prereform period where our test of controls indicated differential prereform trends, which reduced power.

As this was an observational study rather than an experiment, there may have been both measured and unmeasured differences in patient characteristics and comorbidity between the intervention and control group. For example, CMI was lower on the hospitalist service than the resident services. Demographics varied somewhat between services; male and African American patients were more likely to be discharged from resident services than hospitalist services for unknown reasons. Although we adjusted for demographics and CMI in our model, there may be residual confounding. Limitations in data collection did not allow us to separate patients initially admitted to the ICU from patients transferred to the ICU from the inpatient floors. We attempted to overcome this limitation through use of a difference‐in‐differences model to account for secular trends, but factors other than residency work hours may have impacted the resident and hospitalist services differentially. For example, hospital quality‐improvement programs or provider‐level factors may have differentially impacted the resident versus hospitalist services during the study period.

Work‐hour limitations for residents were established to improve residency education and patient safety. As noted by the Institute of Medicine, improving patient safety will require significant investment by program directors, hospitals, and the public to keep resident caseloads manageable, ensure adequate supervision of first‐year residents, train residents on safe handoffs in care, and conduct ongoing evaluations of patient safety and any unintended consequences of the regulations.[33] In the first year after implementation of the 2011 work‐hour reforms, we found no change in ICU admission, inpatient mortality, 30‐day readmission rates, length of stay, or MHACs compared with patients treated by hospitalists. Studies of the long‐term impact of residency work‐hour reform are necessary to determine whether changes in work hours have been associated with improvement in resident education and patient safety.

Disclosure: Nothing to report.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common program requirements effective: July 1, 2011. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramResources/Common_Program_Requirements_07012011[1].pdf. Accessed February 10, 2014.

- , , . The new recommendations on duty hours from the ACGME Task Force. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:e3.

- , , , , . Interns' compliance with Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education work‐hour limits. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1063–1070.

- , , , , , . Effects of work hour reduction on residents' lives: a systematic review. JAMA. 2005;294(9):1088–1100.

- , , , et al. Effects of the ACGME duty hour limits on sleep, work hours, and safety. Pediatrics. 2008;122(2):250–258.

- , , . Teaching hospital five‐year mortality trends in the wake of duty hour reforms. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(8):1048–1055.

- , , , . Duty hour limits and patient care and resident outcomes: can high‐quality studies offer insight into complex relationships? Ann Rev Med. 2013;64:467–483.

- , , . Patient safety, resident education and resident well‐being following implementation of the 2003 ACGME duty hour rules. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(8):907–919.

- , , , et al. Mortality among hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries in the first 2 years following ACGME resident duty hour reform. JAMA. 2007;298(9):975–983.

- , , , et al. Effects of resident duty hour reform on surgical and procedural patient safety indicators among hospitalized Veterans Health Administration and Medicare patients. Med Care. 2009;47(7):723–731.

- , , , et al. Pilot trial of IOM duty hour recommendations in neurology residency programs. Neurology. 2011;77(9):883–887.

- , , , et al. Effect of 16‐hour duty periods of patient care and resident education. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86:192–196.

- , , , et al. Effects of the 2011 duty hour reforms on interns and their patients: a prospective longitudinal cohort study. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(8):657–662.

- , , , et al. Effect of the 2011 vs 2003 duty hour regulation—compliant models on sleep duration, trainee education, and continuity of patient care among internal medicine house staff. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(8):649–655.

- , , . Residents' response to duty‐hour regulations—a follow‐up national survey. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:e35.

- , , , . Surgical residents' perceptions of 2011 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education duty hour regulations. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(5):427–433.

- , , . The 2011 duty hour requirements—a survey of residency program directors. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:694–697.

- , , , et al. The effect of reducing maximum shift lengths to 16 hours on internal medicine interns' educational opportunities. Acad Med. 2013;88(4):512–518.

- , . Residency work‐hours reform. A cost analysis including preventable adverse events. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(10):873–878.

- , , , , . Cost implications of reduced work hours and workloads for resident physicians. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2202–2215.

- , , , . Changes in outcomes for internal medicine inpatients after work‐hour regulations. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:97–103.

- .Maryland Health Services Cost Review Commission. Complications: Maryland Hospital Acquired Conditions. Available at: http://www.hscrc.state.md.us/init_qi_MHAC.cfm. Accessed May 23, 2013.

- , , , et al. What are APR‐DRGs? An introduction to severity of illness and risk of mortality adjustment methodology. 3M Health Information Systems. Available at: http://solutions.3m.com/3MContentRetrievalAPI/BlobServlet?locale=it_IT44(4):1049–1060.

- , , , , . Impact of the 2008 US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation to discontinue prostate cancer screening among male Medicare beneficiaries. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(20):1601–1603.

- , , , et al. Effect of reducing interns' work hour on serious medical errors in intensive care units. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(18):1838–1848.

- , , . Effects of reducing or eliminating resident work shifts over 16 hours: a systematic review. Sleep. 2010;33(8):1043–1053.

- , , , et al. Impact of duty hours restrictions on quality of care and clinical outcomes. Am J Med. 2007;120(11):968–974.