User login

Chronic, nonhealing leg ulcer

An 80-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, psoriasis vulgaris with associated pruritus, and well-controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus presented with a slowly enlarging ulceration on her left leg of 1 year’s duration. She noted that this lesion healed less rapidly than previous stasis leg ulcerations, despite using the same treatment approach that included dressings, elevation, and diuretics to decrease pedal edema.

Physical examination revealed plaques with white micaceous scaling over her extensor surfaces and scalp, as well as guttate lesions on the trunk, typical of psoriasis vulgaris. A 5.8 × 7.2-cm malodorous ulceration was superimposed on a large psoriatic plaque on her left anterior lower leg (FIGURE 1). A 4-mm punch biopsy was obtained from the peripheral margin.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Basal cell carcinoma

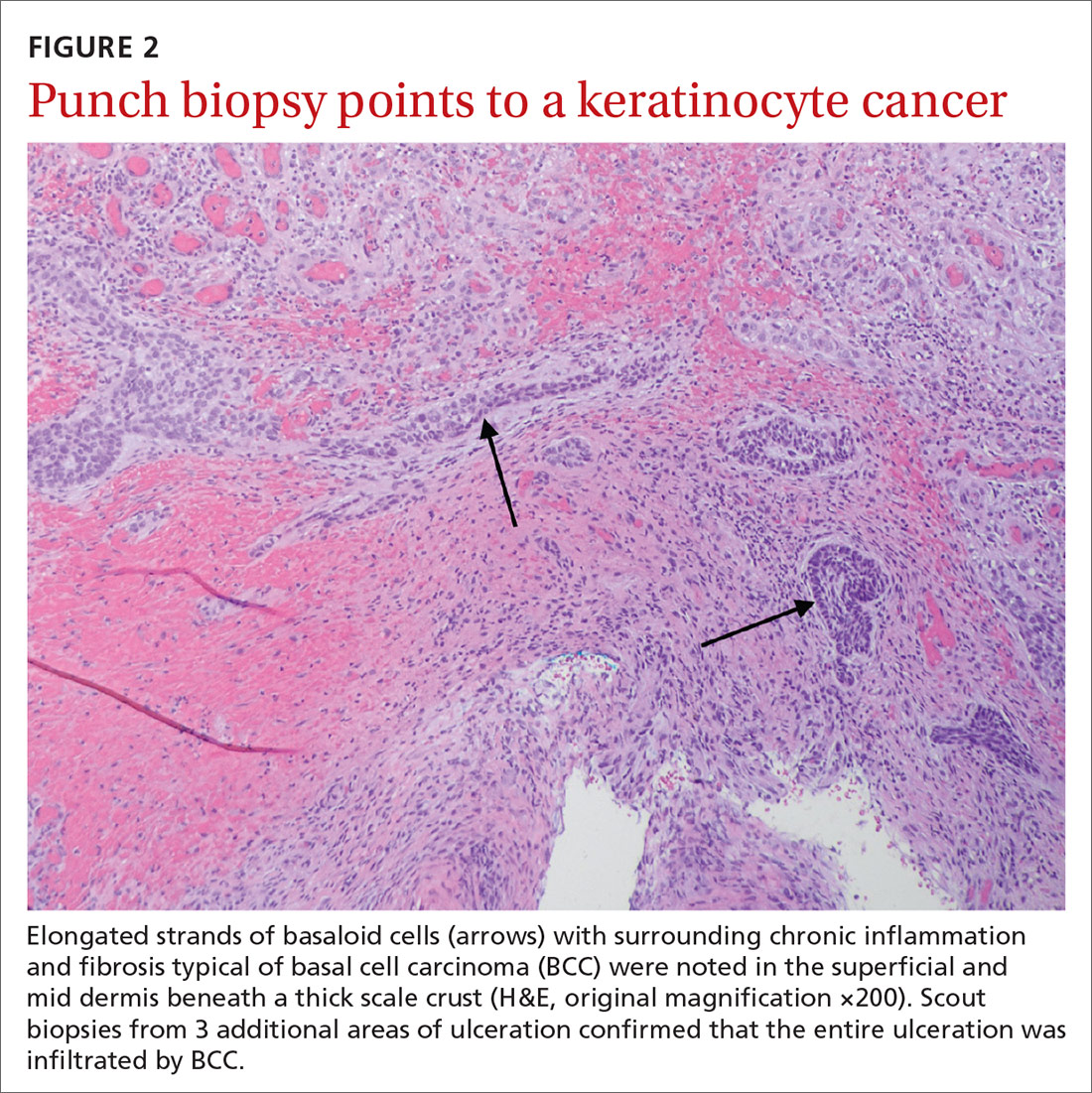

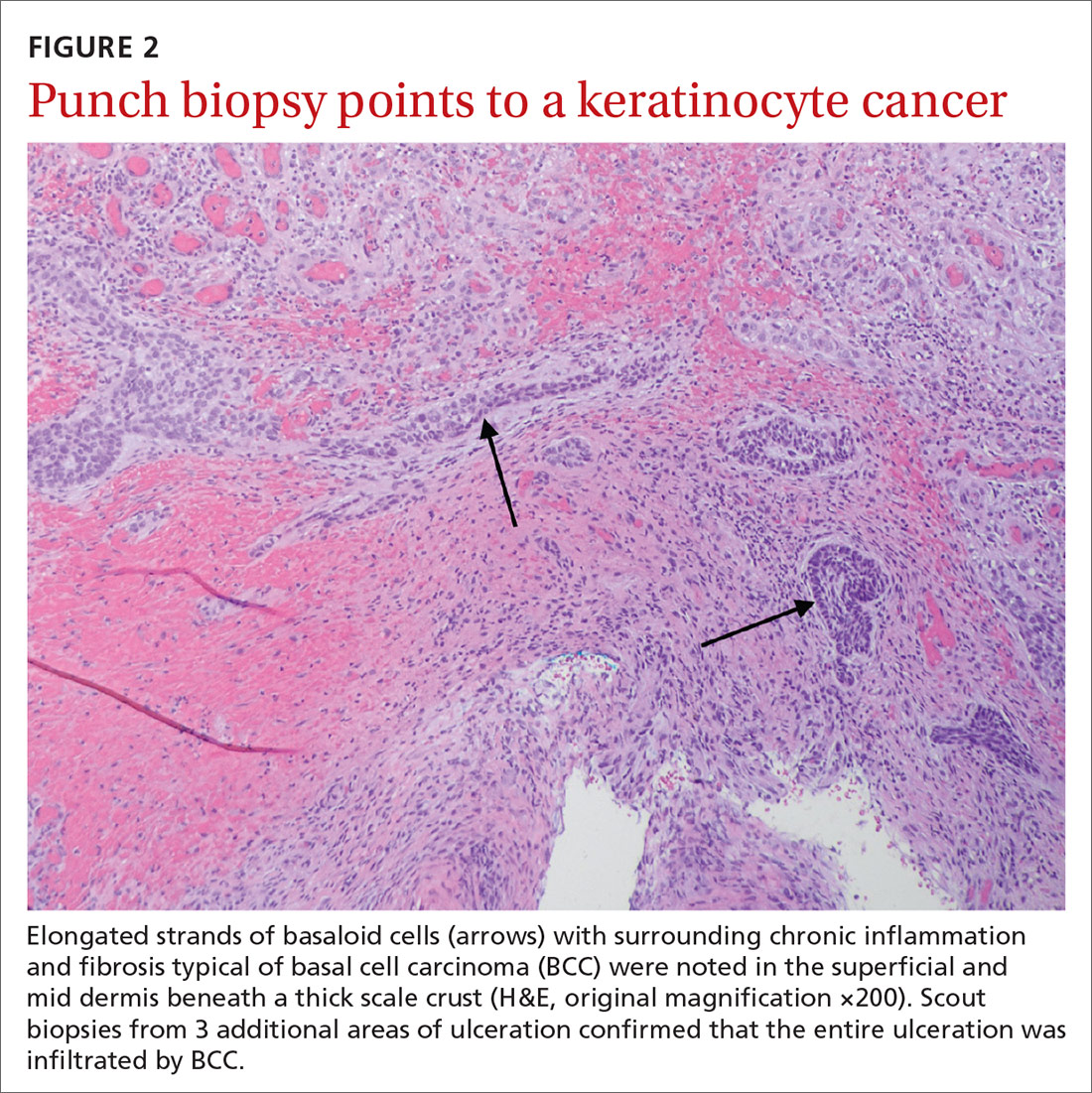

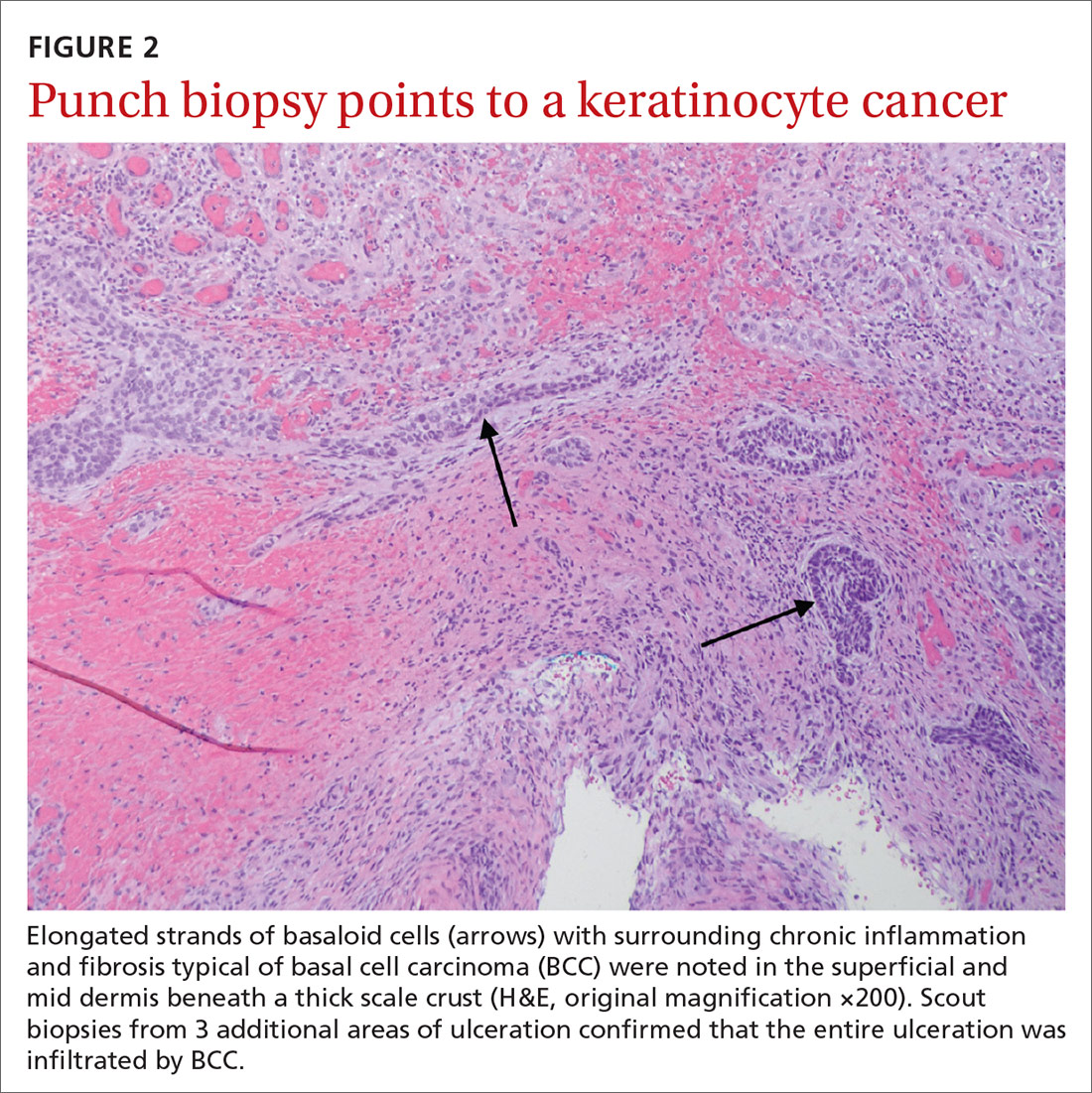

Histopathological examination revealed elongated strands of closely packed basaloid cells embedded in a dense fibrous stroma with overlying ulceration and crusting (FIGURE 2). Immunohistochemical staining with cytokeratin (CK) 5/6 decorated the cytoplasm of the tumor cells, which confirmed that the tumor was a keratinocyte cancer. CK 20 was negative, excluding the possibility of a Merkel cell carcinoma. Scout biopsies from 3 additional areas of ulceration confirmed that the entire ulceration was infiltrated by basal cell carcinoma (BCC).

A surprise hidden in a chronic ulcer

More than 6 million Americans have chronic ulcers and most occur on the legs.1 The majority of these chronic ulcerations are etiologically related to venous stasis, arterial insufficiency, or neuropathy.2

Bacterial pyoderma, chronic infection caused by atypical acid-fast bacilli or deep fungal infection, pyoderma gangrenosum, cutaneous vasculitis, calciphylaxis, and venous ulceration were all considered to explain this patient’s nonhealing wound. A biopsy was required to fully assess these possibilities.

Don’t overlook the possibility of malignancy. In a cross-sectional, multicenter study by Senet et al,3 144 patients with 154 total chronic leg ulcers were evaluated in tertiary care centers for malignancy, which was found to occur at a rate of 10.4%. Similarly, Ghasemi et al4 demonstrated a malignancy rate of 16.1% in 124 patients who underwent biopsy; the anterior shin was determined to be the most frequent location for malignancy. The most common skin cancer identified within the setting of chronic ulcers is squamous cell carcinoma.3 Although rare, there are reports of BCC identified in chronic wounds.3-7

Morphological signs suggestive of malignancy in chronic ulcerations include hyperkeratosis, granulation tissue surrounded by a raised border, unusual pain or bleeding, and increased tissue friability. Our patient had none of these signs and symptoms. However, it is possible that she had a tumor that ulcerated and would not heal.

Continue to: Which came first?

Which came first? It’s difficult to know in this case whether a persistent BCC ulcerated, forming this lesion, or if scarring associated with a chronic ulceration led to the development of the BCC.6 Based on biopsies taken at an earlier date, Schnirring-Judge and Belpedio7 concluded that a chronic leg ulcer could, indeed, transform into a BCC; however, pre-existing BCC more commonly ulcerates and then does not heal.

Treatment options

While smaller, superficial BCCs can be treated with topical imiquimod, photodynamic therapy, or electrodesiccation and curettage, larger lesions should be treated with Mohs micrographic surgery and excisional surgery with grafting. Inoperable tumors may be treated with radiation therapy and vismodegib.

Our patient. Once the diagnosis of BCC was established, treatment options were discussed, including excision, local radiation therapy, and oral hedgehog inhibitor drug therapy.8 Our patient opted to undergo a wide local excision of the lesion followed by negative-pressure wound therapy, which led to complete healing.

CORRESPONDENCE

David Crasto, DO, William Carey University College of Osteopathic Medicine, 498 Tuscan Avenue, Hattiesburg, MS 39401; crastodave@gmail.com

1. Sen CK, Gordillo GM, Roy S, et al. Human skin wounds: a major and snowballing threat to public health and the economy. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;17:763-771.

2. Fox JD, Baquerizo Nole KL, Berriman SJ, et al. Chronic wounds: the need for greater emphasis in medical schools, post-graduate training and public health discussions. Ann Surg. 2016;264:241-243.

3. Senet P, Combemale P, Debure C, et al. Malignancy and chronic leg ulcers. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:704-708.

4. Ghasemi F, Anooshirvani N, Sibbald RG, et al. The point prevalence of malignancy in a wound clinic. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2016;15:58-62.

5. Labropoulos N, Manalo D, Patel N, et al. Uncommon leg ulcers in the lower extremity. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:568-573.

6. Tchanque-Fossuo CN, Millsop J, Johnson MA, et al. Ulcerated basal cell carcinomas masquerading as venous leg ulcers. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2018;31:130-134.

7. Schnirring-Judge M, Belpedio D. Malignant transformation of a chronic venous stasis ulcer to basal cell carcinoma in a diabetic patient: case and review of the pathophysiology. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2010;49:75-79.

8. Puig S, Berrocal A. Management of high-risk and advanced basal cell carcinoma. Clin Transl Oncol. 2015;17:497-503.

An 80-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, psoriasis vulgaris with associated pruritus, and well-controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus presented with a slowly enlarging ulceration on her left leg of 1 year’s duration. She noted that this lesion healed less rapidly than previous stasis leg ulcerations, despite using the same treatment approach that included dressings, elevation, and diuretics to decrease pedal edema.

Physical examination revealed plaques with white micaceous scaling over her extensor surfaces and scalp, as well as guttate lesions on the trunk, typical of psoriasis vulgaris. A 5.8 × 7.2-cm malodorous ulceration was superimposed on a large psoriatic plaque on her left anterior lower leg (FIGURE 1). A 4-mm punch biopsy was obtained from the peripheral margin.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Basal cell carcinoma

Histopathological examination revealed elongated strands of closely packed basaloid cells embedded in a dense fibrous stroma with overlying ulceration and crusting (FIGURE 2). Immunohistochemical staining with cytokeratin (CK) 5/6 decorated the cytoplasm of the tumor cells, which confirmed that the tumor was a keratinocyte cancer. CK 20 was negative, excluding the possibility of a Merkel cell carcinoma. Scout biopsies from 3 additional areas of ulceration confirmed that the entire ulceration was infiltrated by basal cell carcinoma (BCC).

A surprise hidden in a chronic ulcer

More than 6 million Americans have chronic ulcers and most occur on the legs.1 The majority of these chronic ulcerations are etiologically related to venous stasis, arterial insufficiency, or neuropathy.2

Bacterial pyoderma, chronic infection caused by atypical acid-fast bacilli or deep fungal infection, pyoderma gangrenosum, cutaneous vasculitis, calciphylaxis, and venous ulceration were all considered to explain this patient’s nonhealing wound. A biopsy was required to fully assess these possibilities.

Don’t overlook the possibility of malignancy. In a cross-sectional, multicenter study by Senet et al,3 144 patients with 154 total chronic leg ulcers were evaluated in tertiary care centers for malignancy, which was found to occur at a rate of 10.4%. Similarly, Ghasemi et al4 demonstrated a malignancy rate of 16.1% in 124 patients who underwent biopsy; the anterior shin was determined to be the most frequent location for malignancy. The most common skin cancer identified within the setting of chronic ulcers is squamous cell carcinoma.3 Although rare, there are reports of BCC identified in chronic wounds.3-7

Morphological signs suggestive of malignancy in chronic ulcerations include hyperkeratosis, granulation tissue surrounded by a raised border, unusual pain or bleeding, and increased tissue friability. Our patient had none of these signs and symptoms. However, it is possible that she had a tumor that ulcerated and would not heal.

Continue to: Which came first?

Which came first? It’s difficult to know in this case whether a persistent BCC ulcerated, forming this lesion, or if scarring associated with a chronic ulceration led to the development of the BCC.6 Based on biopsies taken at an earlier date, Schnirring-Judge and Belpedio7 concluded that a chronic leg ulcer could, indeed, transform into a BCC; however, pre-existing BCC more commonly ulcerates and then does not heal.

Treatment options

While smaller, superficial BCCs can be treated with topical imiquimod, photodynamic therapy, or electrodesiccation and curettage, larger lesions should be treated with Mohs micrographic surgery and excisional surgery with grafting. Inoperable tumors may be treated with radiation therapy and vismodegib.

Our patient. Once the diagnosis of BCC was established, treatment options were discussed, including excision, local radiation therapy, and oral hedgehog inhibitor drug therapy.8 Our patient opted to undergo a wide local excision of the lesion followed by negative-pressure wound therapy, which led to complete healing.

CORRESPONDENCE

David Crasto, DO, William Carey University College of Osteopathic Medicine, 498 Tuscan Avenue, Hattiesburg, MS 39401; crastodave@gmail.com

An 80-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, psoriasis vulgaris with associated pruritus, and well-controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus presented with a slowly enlarging ulceration on her left leg of 1 year’s duration. She noted that this lesion healed less rapidly than previous stasis leg ulcerations, despite using the same treatment approach that included dressings, elevation, and diuretics to decrease pedal edema.

Physical examination revealed plaques with white micaceous scaling over her extensor surfaces and scalp, as well as guttate lesions on the trunk, typical of psoriasis vulgaris. A 5.8 × 7.2-cm malodorous ulceration was superimposed on a large psoriatic plaque on her left anterior lower leg (FIGURE 1). A 4-mm punch biopsy was obtained from the peripheral margin.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Basal cell carcinoma

Histopathological examination revealed elongated strands of closely packed basaloid cells embedded in a dense fibrous stroma with overlying ulceration and crusting (FIGURE 2). Immunohistochemical staining with cytokeratin (CK) 5/6 decorated the cytoplasm of the tumor cells, which confirmed that the tumor was a keratinocyte cancer. CK 20 was negative, excluding the possibility of a Merkel cell carcinoma. Scout biopsies from 3 additional areas of ulceration confirmed that the entire ulceration was infiltrated by basal cell carcinoma (BCC).

A surprise hidden in a chronic ulcer

More than 6 million Americans have chronic ulcers and most occur on the legs.1 The majority of these chronic ulcerations are etiologically related to venous stasis, arterial insufficiency, or neuropathy.2

Bacterial pyoderma, chronic infection caused by atypical acid-fast bacilli or deep fungal infection, pyoderma gangrenosum, cutaneous vasculitis, calciphylaxis, and venous ulceration were all considered to explain this patient’s nonhealing wound. A biopsy was required to fully assess these possibilities.

Don’t overlook the possibility of malignancy. In a cross-sectional, multicenter study by Senet et al,3 144 patients with 154 total chronic leg ulcers were evaluated in tertiary care centers for malignancy, which was found to occur at a rate of 10.4%. Similarly, Ghasemi et al4 demonstrated a malignancy rate of 16.1% in 124 patients who underwent biopsy; the anterior shin was determined to be the most frequent location for malignancy. The most common skin cancer identified within the setting of chronic ulcers is squamous cell carcinoma.3 Although rare, there are reports of BCC identified in chronic wounds.3-7

Morphological signs suggestive of malignancy in chronic ulcerations include hyperkeratosis, granulation tissue surrounded by a raised border, unusual pain or bleeding, and increased tissue friability. Our patient had none of these signs and symptoms. However, it is possible that she had a tumor that ulcerated and would not heal.

Continue to: Which came first?

Which came first? It’s difficult to know in this case whether a persistent BCC ulcerated, forming this lesion, or if scarring associated with a chronic ulceration led to the development of the BCC.6 Based on biopsies taken at an earlier date, Schnirring-Judge and Belpedio7 concluded that a chronic leg ulcer could, indeed, transform into a BCC; however, pre-existing BCC more commonly ulcerates and then does not heal.

Treatment options

While smaller, superficial BCCs can be treated with topical imiquimod, photodynamic therapy, or electrodesiccation and curettage, larger lesions should be treated with Mohs micrographic surgery and excisional surgery with grafting. Inoperable tumors may be treated with radiation therapy and vismodegib.

Our patient. Once the diagnosis of BCC was established, treatment options were discussed, including excision, local radiation therapy, and oral hedgehog inhibitor drug therapy.8 Our patient opted to undergo a wide local excision of the lesion followed by negative-pressure wound therapy, which led to complete healing.

CORRESPONDENCE

David Crasto, DO, William Carey University College of Osteopathic Medicine, 498 Tuscan Avenue, Hattiesburg, MS 39401; crastodave@gmail.com

1. Sen CK, Gordillo GM, Roy S, et al. Human skin wounds: a major and snowballing threat to public health and the economy. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;17:763-771.

2. Fox JD, Baquerizo Nole KL, Berriman SJ, et al. Chronic wounds: the need for greater emphasis in medical schools, post-graduate training and public health discussions. Ann Surg. 2016;264:241-243.

3. Senet P, Combemale P, Debure C, et al. Malignancy and chronic leg ulcers. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:704-708.

4. Ghasemi F, Anooshirvani N, Sibbald RG, et al. The point prevalence of malignancy in a wound clinic. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2016;15:58-62.

5. Labropoulos N, Manalo D, Patel N, et al. Uncommon leg ulcers in the lower extremity. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:568-573.

6. Tchanque-Fossuo CN, Millsop J, Johnson MA, et al. Ulcerated basal cell carcinomas masquerading as venous leg ulcers. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2018;31:130-134.

7. Schnirring-Judge M, Belpedio D. Malignant transformation of a chronic venous stasis ulcer to basal cell carcinoma in a diabetic patient: case and review of the pathophysiology. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2010;49:75-79.

8. Puig S, Berrocal A. Management of high-risk and advanced basal cell carcinoma. Clin Transl Oncol. 2015;17:497-503.

1. Sen CK, Gordillo GM, Roy S, et al. Human skin wounds: a major and snowballing threat to public health and the economy. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;17:763-771.

2. Fox JD, Baquerizo Nole KL, Berriman SJ, et al. Chronic wounds: the need for greater emphasis in medical schools, post-graduate training and public health discussions. Ann Surg. 2016;264:241-243.

3. Senet P, Combemale P, Debure C, et al. Malignancy and chronic leg ulcers. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:704-708.

4. Ghasemi F, Anooshirvani N, Sibbald RG, et al. The point prevalence of malignancy in a wound clinic. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2016;15:58-62.

5. Labropoulos N, Manalo D, Patel N, et al. Uncommon leg ulcers in the lower extremity. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:568-573.

6. Tchanque-Fossuo CN, Millsop J, Johnson MA, et al. Ulcerated basal cell carcinomas masquerading as venous leg ulcers. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2018;31:130-134.

7. Schnirring-Judge M, Belpedio D. Malignant transformation of a chronic venous stasis ulcer to basal cell carcinoma in a diabetic patient: case and review of the pathophysiology. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2010;49:75-79.

8. Puig S, Berrocal A. Management of high-risk and advanced basal cell carcinoma. Clin Transl Oncol. 2015;17:497-503.

Evaluating the Malignant Potential of Nevus Spilus

Annular plaques on the back and flanks

An 86-year-old African American woman sought care for an asymptomatic rash on her back and flanks that she’d had for 14 months. Physical examination of her trunk revealed 3 to 6 cm annular/arcuate plaques with central clearing. The lesions also had a delicate trailing scale behind a slightly raised erythematous rim (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythema annulare centrifugum

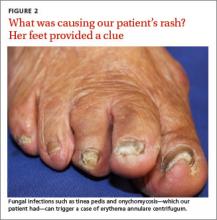

Potassium hydroxide (KOH) testing and culture of the rash were negative, but a KOH of the skin between her toes and her toenails revealed septate hyphae, which confirmed a diagnosis of tinea pedis and onychomycosis. The combination of tinea pedis/onychomycosis and the clinical appearance of the rash on the patient’s flanks led us to diagnose erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) in this patient.

EAC is a noninfectious hypersensitivity phenomenon.1 It is most commonly associated with dermatophyte fungi, but other inciting agents include candida, penicillium in blue cheese, viruses (varicella zoster virus, human immunodeficiency virus, Epstein-Barr virus), ectoparasites (phthirus pubis), and, rarely, certain medications, including diuretics, finasteride, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antimalarials, and amitriptyline.2-6 Hormonal changes during pregnancy and neoplasms have occasionally been associated with EAC.2-4

Histologic findings are nonspecific in EAC, but a biopsy may be performed to exclude other conditions. Superficial EAC demonstrates histologic changes primarily in the epidermis, including spongiosis, parakeratosis, and a superficial inflammatory infiltrate.8 The deep variant demonstrates superficial to deep dermal lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate in a perivascular “sleeve-like” distribution with little epidermal change.7,8

Differential diagnosis includes figurate erythemas

The differential diagnosis includes figurate erythemas (erythema chronicum migrans and erythema marginatum) and other conditions with annular, scaling plaques (tinea corporis [ringworm], annular psoriasis, pityriasis rosea, syphilis (secondary stage), and mycosis fungoides).2,9

Figurate erythemas. Unlike EAC, figurate erythemas are non-scaling annular lesions. Erythema chronicum migrans is a manifestation of Lyme disease. It is characterized by papules that expand peripherally at the site of a tick bite. In some cases, secondary lesions distant from the bite occur. Erythema marginatum is associated with rheumatic fever. These nonpruritic red circular rings without scale are unique in their capacity to expand several centimeters per day.

Conditions characterized by annular scaling plaques. Tinea corporis presents as round red patches that slowly become ring-shaped, with a raised border and clear center. Unlike EAC, the scale is present at the leading border of the rings.

Annular psoriasis is characterized by ring-shaped patches with white micaceous scaling and central clearing. Topical steroid use may be responsible for the central clearing as scaled patches expand. This rash can appear in places EAC typically does not, such as on the scalp, elbows, and knees.

Pityriasis rosea starts with a solitary herald patch a few days before hundreds of small oval scaled patches appear on the trunk in a “fir tree” distribution. Unlike EAC, the herald patch does not show the trailing scale.

The rash associated with the secondary stage of syphilis can appear on the soles of the feet and palms, which differs from EAC because EAC typically spares the feet and hands.

In the patch stage of mycosis fungoides, the ring-shaped rash can appear similar to psoriasis or chronic eczema, but can sometimes last years to even decades. Unlike EAC, these rings do not show a trailing scale and the patches may demonstrate poikiloderma (erythema, atrophy, and dyspigmentation).

To treat EAC, eliminate the trigger

Treatment of EAC should focus on eliminating the inciting agent.2 In one study of 66 patients with EAC, 42%, had a concomitant cutaneous fungal infection (tinea pedis, tinea corporis, or onychomycosis).3 A direct cause-and-effect relationship was established in 2 patients with dermatophyte-induced EAC whose lesions were reproduced and subsequently cleared by the experimental inoculation and treatment of tinea pedis.1

Our patient. Four weeks of oral terbinafine 250 mg/d effectively cleared our patient’s case of tinea pedis and EAC. After 3 months of treatment with terbinafine the onychomycosis showed one-third clearing at the proximal nail fold. Without additional treatment, the nails were completely clear 8 months later.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert T. Brodell, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216; rbrodell@umc.edu

1. Jillson OF, Hoekelman RA. Further amplification of the concept of dermatophytid. I. Erythema annulare centrifugum as a dermatophytid. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1952;66:738-745.

2. España A. Figurate erythemas. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadephia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:307-312.

3. Kim KJ, Chang SE, Choi JH, et al. Clinicopathologic analysis of 66 cases of erythema annulare centrifugum. J Dermatol. 2002;29:61-67.

4. Ziemer M, Eisendle K, Zelger B. New concepts on erythema annulare centrifugum: a clinical reaction pattern that does not represent a specific clinicopathological entity. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:119-126.

5. Ohmori S, Sugita K, Ikenouci-Sugita A, et al. Erythema annulare centrifugum associated with herpes zoster. J UOEH. 2012;34:225-229.

6. Shelley WB. Erythema annulare centrifugum. A case due to hypersensitivity to blue cheese penicillium. Arch Dermatol. 1964;90:54-58.

7. Weyers W, Diaz-Cascajo C, Weyers I. Erythema annulare centrifugum: results of a clinicopathologic study of 73 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:451-462.

8. Ríos-Martín JJ, Ferrándiz-Pulido L, Moreno-Ramírez D. Approaches to the dermatopathologic diagnosis of figurate lesions [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2011;102:316-324.

9. Boucher K, Haimowitz J. Erythema annulare centrifugum. In: Lebwohl MG, Heymann WR, Berth-Jones J, et al. Treatment of Skin Disease: Comprehensive Therapeutic Strategies. New York, NY: Mosby; 2002:188-189.

An 86-year-old African American woman sought care for an asymptomatic rash on her back and flanks that she’d had for 14 months. Physical examination of her trunk revealed 3 to 6 cm annular/arcuate plaques with central clearing. The lesions also had a delicate trailing scale behind a slightly raised erythematous rim (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythema annulare centrifugum

Potassium hydroxide (KOH) testing and culture of the rash were negative, but a KOH of the skin between her toes and her toenails revealed septate hyphae, which confirmed a diagnosis of tinea pedis and onychomycosis. The combination of tinea pedis/onychomycosis and the clinical appearance of the rash on the patient’s flanks led us to diagnose erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) in this patient.

EAC is a noninfectious hypersensitivity phenomenon.1 It is most commonly associated with dermatophyte fungi, but other inciting agents include candida, penicillium in blue cheese, viruses (varicella zoster virus, human immunodeficiency virus, Epstein-Barr virus), ectoparasites (phthirus pubis), and, rarely, certain medications, including diuretics, finasteride, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antimalarials, and amitriptyline.2-6 Hormonal changes during pregnancy and neoplasms have occasionally been associated with EAC.2-4

Histologic findings are nonspecific in EAC, but a biopsy may be performed to exclude other conditions. Superficial EAC demonstrates histologic changes primarily in the epidermis, including spongiosis, parakeratosis, and a superficial inflammatory infiltrate.8 The deep variant demonstrates superficial to deep dermal lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate in a perivascular “sleeve-like” distribution with little epidermal change.7,8

Differential diagnosis includes figurate erythemas

The differential diagnosis includes figurate erythemas (erythema chronicum migrans and erythema marginatum) and other conditions with annular, scaling plaques (tinea corporis [ringworm], annular psoriasis, pityriasis rosea, syphilis (secondary stage), and mycosis fungoides).2,9

Figurate erythemas. Unlike EAC, figurate erythemas are non-scaling annular lesions. Erythema chronicum migrans is a manifestation of Lyme disease. It is characterized by papules that expand peripherally at the site of a tick bite. In some cases, secondary lesions distant from the bite occur. Erythema marginatum is associated with rheumatic fever. These nonpruritic red circular rings without scale are unique in their capacity to expand several centimeters per day.

Conditions characterized by annular scaling plaques. Tinea corporis presents as round red patches that slowly become ring-shaped, with a raised border and clear center. Unlike EAC, the scale is present at the leading border of the rings.

Annular psoriasis is characterized by ring-shaped patches with white micaceous scaling and central clearing. Topical steroid use may be responsible for the central clearing as scaled patches expand. This rash can appear in places EAC typically does not, such as on the scalp, elbows, and knees.

Pityriasis rosea starts with a solitary herald patch a few days before hundreds of small oval scaled patches appear on the trunk in a “fir tree” distribution. Unlike EAC, the herald patch does not show the trailing scale.

The rash associated with the secondary stage of syphilis can appear on the soles of the feet and palms, which differs from EAC because EAC typically spares the feet and hands.

In the patch stage of mycosis fungoides, the ring-shaped rash can appear similar to psoriasis or chronic eczema, but can sometimes last years to even decades. Unlike EAC, these rings do not show a trailing scale and the patches may demonstrate poikiloderma (erythema, atrophy, and dyspigmentation).

To treat EAC, eliminate the trigger

Treatment of EAC should focus on eliminating the inciting agent.2 In one study of 66 patients with EAC, 42%, had a concomitant cutaneous fungal infection (tinea pedis, tinea corporis, or onychomycosis).3 A direct cause-and-effect relationship was established in 2 patients with dermatophyte-induced EAC whose lesions were reproduced and subsequently cleared by the experimental inoculation and treatment of tinea pedis.1

Our patient. Four weeks of oral terbinafine 250 mg/d effectively cleared our patient’s case of tinea pedis and EAC. After 3 months of treatment with terbinafine the onychomycosis showed one-third clearing at the proximal nail fold. Without additional treatment, the nails were completely clear 8 months later.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert T. Brodell, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216; rbrodell@umc.edu

An 86-year-old African American woman sought care for an asymptomatic rash on her back and flanks that she’d had for 14 months. Physical examination of her trunk revealed 3 to 6 cm annular/arcuate plaques with central clearing. The lesions also had a delicate trailing scale behind a slightly raised erythematous rim (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythema annulare centrifugum

Potassium hydroxide (KOH) testing and culture of the rash were negative, but a KOH of the skin between her toes and her toenails revealed septate hyphae, which confirmed a diagnosis of tinea pedis and onychomycosis. The combination of tinea pedis/onychomycosis and the clinical appearance of the rash on the patient’s flanks led us to diagnose erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) in this patient.

EAC is a noninfectious hypersensitivity phenomenon.1 It is most commonly associated with dermatophyte fungi, but other inciting agents include candida, penicillium in blue cheese, viruses (varicella zoster virus, human immunodeficiency virus, Epstein-Barr virus), ectoparasites (phthirus pubis), and, rarely, certain medications, including diuretics, finasteride, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antimalarials, and amitriptyline.2-6 Hormonal changes during pregnancy and neoplasms have occasionally been associated with EAC.2-4

Histologic findings are nonspecific in EAC, but a biopsy may be performed to exclude other conditions. Superficial EAC demonstrates histologic changes primarily in the epidermis, including spongiosis, parakeratosis, and a superficial inflammatory infiltrate.8 The deep variant demonstrates superficial to deep dermal lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate in a perivascular “sleeve-like” distribution with little epidermal change.7,8

Differential diagnosis includes figurate erythemas

The differential diagnosis includes figurate erythemas (erythema chronicum migrans and erythema marginatum) and other conditions with annular, scaling plaques (tinea corporis [ringworm], annular psoriasis, pityriasis rosea, syphilis (secondary stage), and mycosis fungoides).2,9

Figurate erythemas. Unlike EAC, figurate erythemas are non-scaling annular lesions. Erythema chronicum migrans is a manifestation of Lyme disease. It is characterized by papules that expand peripherally at the site of a tick bite. In some cases, secondary lesions distant from the bite occur. Erythema marginatum is associated with rheumatic fever. These nonpruritic red circular rings without scale are unique in their capacity to expand several centimeters per day.

Conditions characterized by annular scaling plaques. Tinea corporis presents as round red patches that slowly become ring-shaped, with a raised border and clear center. Unlike EAC, the scale is present at the leading border of the rings.

Annular psoriasis is characterized by ring-shaped patches with white micaceous scaling and central clearing. Topical steroid use may be responsible for the central clearing as scaled patches expand. This rash can appear in places EAC typically does not, such as on the scalp, elbows, and knees.

Pityriasis rosea starts with a solitary herald patch a few days before hundreds of small oval scaled patches appear on the trunk in a “fir tree” distribution. Unlike EAC, the herald patch does not show the trailing scale.

The rash associated with the secondary stage of syphilis can appear on the soles of the feet and palms, which differs from EAC because EAC typically spares the feet and hands.

In the patch stage of mycosis fungoides, the ring-shaped rash can appear similar to psoriasis or chronic eczema, but can sometimes last years to even decades. Unlike EAC, these rings do not show a trailing scale and the patches may demonstrate poikiloderma (erythema, atrophy, and dyspigmentation).

To treat EAC, eliminate the trigger

Treatment of EAC should focus on eliminating the inciting agent.2 In one study of 66 patients with EAC, 42%, had a concomitant cutaneous fungal infection (tinea pedis, tinea corporis, or onychomycosis).3 A direct cause-and-effect relationship was established in 2 patients with dermatophyte-induced EAC whose lesions were reproduced and subsequently cleared by the experimental inoculation and treatment of tinea pedis.1

Our patient. Four weeks of oral terbinafine 250 mg/d effectively cleared our patient’s case of tinea pedis and EAC. After 3 months of treatment with terbinafine the onychomycosis showed one-third clearing at the proximal nail fold. Without additional treatment, the nails were completely clear 8 months later.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert T. Brodell, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216; rbrodell@umc.edu

1. Jillson OF, Hoekelman RA. Further amplification of the concept of dermatophytid. I. Erythema annulare centrifugum as a dermatophytid. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1952;66:738-745.

2. España A. Figurate erythemas. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadephia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:307-312.

3. Kim KJ, Chang SE, Choi JH, et al. Clinicopathologic analysis of 66 cases of erythema annulare centrifugum. J Dermatol. 2002;29:61-67.

4. Ziemer M, Eisendle K, Zelger B. New concepts on erythema annulare centrifugum: a clinical reaction pattern that does not represent a specific clinicopathological entity. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:119-126.

5. Ohmori S, Sugita K, Ikenouci-Sugita A, et al. Erythema annulare centrifugum associated with herpes zoster. J UOEH. 2012;34:225-229.

6. Shelley WB. Erythema annulare centrifugum. A case due to hypersensitivity to blue cheese penicillium. Arch Dermatol. 1964;90:54-58.

7. Weyers W, Diaz-Cascajo C, Weyers I. Erythema annulare centrifugum: results of a clinicopathologic study of 73 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:451-462.

8. Ríos-Martín JJ, Ferrándiz-Pulido L, Moreno-Ramírez D. Approaches to the dermatopathologic diagnosis of figurate lesions [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2011;102:316-324.

9. Boucher K, Haimowitz J. Erythema annulare centrifugum. In: Lebwohl MG, Heymann WR, Berth-Jones J, et al. Treatment of Skin Disease: Comprehensive Therapeutic Strategies. New York, NY: Mosby; 2002:188-189.

1. Jillson OF, Hoekelman RA. Further amplification of the concept of dermatophytid. I. Erythema annulare centrifugum as a dermatophytid. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1952;66:738-745.

2. España A. Figurate erythemas. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadephia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:307-312.

3. Kim KJ, Chang SE, Choi JH, et al. Clinicopathologic analysis of 66 cases of erythema annulare centrifugum. J Dermatol. 2002;29:61-67.

4. Ziemer M, Eisendle K, Zelger B. New concepts on erythema annulare centrifugum: a clinical reaction pattern that does not represent a specific clinicopathological entity. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:119-126.

5. Ohmori S, Sugita K, Ikenouci-Sugita A, et al. Erythema annulare centrifugum associated with herpes zoster. J UOEH. 2012;34:225-229.

6. Shelley WB. Erythema annulare centrifugum. A case due to hypersensitivity to blue cheese penicillium. Arch Dermatol. 1964;90:54-58.

7. Weyers W, Diaz-Cascajo C, Weyers I. Erythema annulare centrifugum: results of a clinicopathologic study of 73 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:451-462.

8. Ríos-Martín JJ, Ferrándiz-Pulido L, Moreno-Ramírez D. Approaches to the dermatopathologic diagnosis of figurate lesions [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2011;102:316-324.

9. Boucher K, Haimowitz J. Erythema annulare centrifugum. In: Lebwohl MG, Heymann WR, Berth-Jones J, et al. Treatment of Skin Disease: Comprehensive Therapeutic Strategies. New York, NY: Mosby; 2002:188-189.

Occipital scalp papules in a teenage boy

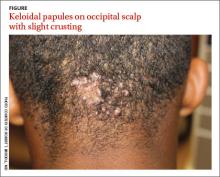

A 15-year-old African American boy with no previous medical problems presented with a 2-month history of hair loss and pruritic papules on the occipital scalp that had developed after a barber shaved the area. Physical examination revealed 2 dozen 1 to 2 mm keloidal papules on the posterior neck and occipital scalp with areas of focal crusting (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Acne keloidalis nuchae

Acne keloidalis nuchae is a chronic folliculitis that is characterized by smooth, dome-shaped papules on the posterior scalp and neck that become confluent, forming firm papules and hairless, keloid-like plaques.1 Seen almost exclusively in young, postpubescent African American males, the condition is often asymptomatic, although some patients complain that the affected area itches. The cause of acne keloidalis nuchae may be associated with an acute pseudofolliculitis secondary to close-shaved curly hair reentering the skin; this leads to a foreign body reaction to hair protein and subsequent fibrosis.2

Differential Dx includes acne vulgaris

Acne keloidalis nuchae is diagnosed based on the appearance and location of the papules and keloid-like plaques as well as the patient’s history. The differential diagnosis includes acne vulgaris, hidradenitis suppurativa, and pseudofolliculitis barbae.

Acne vulgaris is a disorder of the pilosebaceous follicles primarily seen on the face, upper part of the chest, and back. Unlike acne keloidalis, it is characterized by the presence of comedones.1,3

Hidradenitis suppurativa is characterized by secondary inflammation of the apocrine glands, which produces inflamed nodules and abscesses, primarily in the axillae, groin, and anogenital region.1

Pseudofolliculitis barbae looks very similar to the initial presentation of acne keloidalis nuchae, and in fact, the pathophysiologic mechanism is the same. That said, pseudofolliculitis barbae occurs on the beard area and rarely produces keloidal papules.3

Treat with steroids, antibiotics

Treatment of acne keloidalis nuchae is often difficult. Early treatment, however, decreases the potential for developing larger lesions and long-term disfigurement.1

Topical steroid therapy is indicated for mild to moderate acne keloidalis nuchae. Application of tretinoin 0.01% gel once or twice daily for several months has an anti-inflammatory effect and alters keratinocyte differentiation, which may discharge ingrown hairs. Topical and systemic antibiotics minimize infection associated with pseudofolliculitis and have anti-inflammatory effects.1,3 Intralesional steroid injections (triamcinolone acetonide 2.5-5 mg/cc) with 0.1 cc injected into each lesion every 2 to 3 weeks for 3 to 6 injections can reduce inflammation and pruritus and reduce the thickness of keloidal scars.3 (For a how-to video that illustrates intralesional injections, go to http://www.jfponline.com/multimedia/video.html.)

Surgical management is generally reserved for large lesions that do not respond to medical management. Surgical excision with healing by secondary intention has been reported to cause fewer recurrences than surgical excision with primary closure.4 The use of CO2 laser ablation can be considered for advanced cases.5

Teach patients with acne keloidalis nuchae that they can prevent further irritation of the affected area by not wearing head gear that rubs on the involved area. Patients should also refrain from shaving the posterior scalp and neck to prevent the pseudofolliculitis that may be causing this condition.1,3 Electric barber trimmers that leave a short stubble but do not cleanly shave the skin are OK to use.

Our patient’s papules flattened and became asymptomatic over several months of treatment with tretinoin 0.01% gel, doxycycline 100 mg daily, and a series of biweekly intralesion steroid injections. A flat-scarred patch remained.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert T. Brodell, MD, Division of Dermatology, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216; rbrodell@umc.edu

1. McMichael A, Sanchez DG, Kelly P. Folliculitis and the follicular occlusion tetrad. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo, JL, Rapini RP, et al (eds). Dermatology. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Mosby; 2008: 517-530.

2. Herzberg AJ, Dinehart SM, Kerns BJ, et al. Acne keloidalis. Transverse microscopy, immunohistochemistry, and electron microscopy. Am J Dermatopathol. 1990;12:109-121.

3. Kelly AP. Pseudofolliculitis barbae and acne keloidalis nuchae. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:645-653.

4. Glenn MG, Bennett RG, Kelly AP. Acne keloidalis nuchae: treatment with excision and second-intention healing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33(2 pt 1):243-246.

5. Kantor GR, Ratz JL, Wheeland RG. Treatment of acne keloidalis nuchae with carbon dioxide laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14(2 pt 1):263-267.

A 15-year-old African American boy with no previous medical problems presented with a 2-month history of hair loss and pruritic papules on the occipital scalp that had developed after a barber shaved the area. Physical examination revealed 2 dozen 1 to 2 mm keloidal papules on the posterior neck and occipital scalp with areas of focal crusting (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Acne keloidalis nuchae

Acne keloidalis nuchae is a chronic folliculitis that is characterized by smooth, dome-shaped papules on the posterior scalp and neck that become confluent, forming firm papules and hairless, keloid-like plaques.1 Seen almost exclusively in young, postpubescent African American males, the condition is often asymptomatic, although some patients complain that the affected area itches. The cause of acne keloidalis nuchae may be associated with an acute pseudofolliculitis secondary to close-shaved curly hair reentering the skin; this leads to a foreign body reaction to hair protein and subsequent fibrosis.2

Differential Dx includes acne vulgaris

Acne keloidalis nuchae is diagnosed based on the appearance and location of the papules and keloid-like plaques as well as the patient’s history. The differential diagnosis includes acne vulgaris, hidradenitis suppurativa, and pseudofolliculitis barbae.

Acne vulgaris is a disorder of the pilosebaceous follicles primarily seen on the face, upper part of the chest, and back. Unlike acne keloidalis, it is characterized by the presence of comedones.1,3

Hidradenitis suppurativa is characterized by secondary inflammation of the apocrine glands, which produces inflamed nodules and abscesses, primarily in the axillae, groin, and anogenital region.1

Pseudofolliculitis barbae looks very similar to the initial presentation of acne keloidalis nuchae, and in fact, the pathophysiologic mechanism is the same. That said, pseudofolliculitis barbae occurs on the beard area and rarely produces keloidal papules.3

Treat with steroids, antibiotics

Treatment of acne keloidalis nuchae is often difficult. Early treatment, however, decreases the potential for developing larger lesions and long-term disfigurement.1

Topical steroid therapy is indicated for mild to moderate acne keloidalis nuchae. Application of tretinoin 0.01% gel once or twice daily for several months has an anti-inflammatory effect and alters keratinocyte differentiation, which may discharge ingrown hairs. Topical and systemic antibiotics minimize infection associated with pseudofolliculitis and have anti-inflammatory effects.1,3 Intralesional steroid injections (triamcinolone acetonide 2.5-5 mg/cc) with 0.1 cc injected into each lesion every 2 to 3 weeks for 3 to 6 injections can reduce inflammation and pruritus and reduce the thickness of keloidal scars.3 (For a how-to video that illustrates intralesional injections, go to http://www.jfponline.com/multimedia/video.html.)

Surgical management is generally reserved for large lesions that do not respond to medical management. Surgical excision with healing by secondary intention has been reported to cause fewer recurrences than surgical excision with primary closure.4 The use of CO2 laser ablation can be considered for advanced cases.5

Teach patients with acne keloidalis nuchae that they can prevent further irritation of the affected area by not wearing head gear that rubs on the involved area. Patients should also refrain from shaving the posterior scalp and neck to prevent the pseudofolliculitis that may be causing this condition.1,3 Electric barber trimmers that leave a short stubble but do not cleanly shave the skin are OK to use.

Our patient’s papules flattened and became asymptomatic over several months of treatment with tretinoin 0.01% gel, doxycycline 100 mg daily, and a series of biweekly intralesion steroid injections. A flat-scarred patch remained.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert T. Brodell, MD, Division of Dermatology, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216; rbrodell@umc.edu

A 15-year-old African American boy with no previous medical problems presented with a 2-month history of hair loss and pruritic papules on the occipital scalp that had developed after a barber shaved the area. Physical examination revealed 2 dozen 1 to 2 mm keloidal papules on the posterior neck and occipital scalp with areas of focal crusting (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Acne keloidalis nuchae

Acne keloidalis nuchae is a chronic folliculitis that is characterized by smooth, dome-shaped papules on the posterior scalp and neck that become confluent, forming firm papules and hairless, keloid-like plaques.1 Seen almost exclusively in young, postpubescent African American males, the condition is often asymptomatic, although some patients complain that the affected area itches. The cause of acne keloidalis nuchae may be associated with an acute pseudofolliculitis secondary to close-shaved curly hair reentering the skin; this leads to a foreign body reaction to hair protein and subsequent fibrosis.2

Differential Dx includes acne vulgaris

Acne keloidalis nuchae is diagnosed based on the appearance and location of the papules and keloid-like plaques as well as the patient’s history. The differential diagnosis includes acne vulgaris, hidradenitis suppurativa, and pseudofolliculitis barbae.

Acne vulgaris is a disorder of the pilosebaceous follicles primarily seen on the face, upper part of the chest, and back. Unlike acne keloidalis, it is characterized by the presence of comedones.1,3

Hidradenitis suppurativa is characterized by secondary inflammation of the apocrine glands, which produces inflamed nodules and abscesses, primarily in the axillae, groin, and anogenital region.1

Pseudofolliculitis barbae looks very similar to the initial presentation of acne keloidalis nuchae, and in fact, the pathophysiologic mechanism is the same. That said, pseudofolliculitis barbae occurs on the beard area and rarely produces keloidal papules.3

Treat with steroids, antibiotics

Treatment of acne keloidalis nuchae is often difficult. Early treatment, however, decreases the potential for developing larger lesions and long-term disfigurement.1

Topical steroid therapy is indicated for mild to moderate acne keloidalis nuchae. Application of tretinoin 0.01% gel once or twice daily for several months has an anti-inflammatory effect and alters keratinocyte differentiation, which may discharge ingrown hairs. Topical and systemic antibiotics minimize infection associated with pseudofolliculitis and have anti-inflammatory effects.1,3 Intralesional steroid injections (triamcinolone acetonide 2.5-5 mg/cc) with 0.1 cc injected into each lesion every 2 to 3 weeks for 3 to 6 injections can reduce inflammation and pruritus and reduce the thickness of keloidal scars.3 (For a how-to video that illustrates intralesional injections, go to http://www.jfponline.com/multimedia/video.html.)

Surgical management is generally reserved for large lesions that do not respond to medical management. Surgical excision with healing by secondary intention has been reported to cause fewer recurrences than surgical excision with primary closure.4 The use of CO2 laser ablation can be considered for advanced cases.5

Teach patients with acne keloidalis nuchae that they can prevent further irritation of the affected area by not wearing head gear that rubs on the involved area. Patients should also refrain from shaving the posterior scalp and neck to prevent the pseudofolliculitis that may be causing this condition.1,3 Electric barber trimmers that leave a short stubble but do not cleanly shave the skin are OK to use.

Our patient’s papules flattened and became asymptomatic over several months of treatment with tretinoin 0.01% gel, doxycycline 100 mg daily, and a series of biweekly intralesion steroid injections. A flat-scarred patch remained.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert T. Brodell, MD, Division of Dermatology, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216; rbrodell@umc.edu

1. McMichael A, Sanchez DG, Kelly P. Folliculitis and the follicular occlusion tetrad. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo, JL, Rapini RP, et al (eds). Dermatology. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Mosby; 2008: 517-530.

2. Herzberg AJ, Dinehart SM, Kerns BJ, et al. Acne keloidalis. Transverse microscopy, immunohistochemistry, and electron microscopy. Am J Dermatopathol. 1990;12:109-121.

3. Kelly AP. Pseudofolliculitis barbae and acne keloidalis nuchae. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:645-653.

4. Glenn MG, Bennett RG, Kelly AP. Acne keloidalis nuchae: treatment with excision and second-intention healing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33(2 pt 1):243-246.

5. Kantor GR, Ratz JL, Wheeland RG. Treatment of acne keloidalis nuchae with carbon dioxide laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14(2 pt 1):263-267.

1. McMichael A, Sanchez DG, Kelly P. Folliculitis and the follicular occlusion tetrad. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo, JL, Rapini RP, et al (eds). Dermatology. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Mosby; 2008: 517-530.

2. Herzberg AJ, Dinehart SM, Kerns BJ, et al. Acne keloidalis. Transverse microscopy, immunohistochemistry, and electron microscopy. Am J Dermatopathol. 1990;12:109-121.

3. Kelly AP. Pseudofolliculitis barbae and acne keloidalis nuchae. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:645-653.

4. Glenn MG, Bennett RG, Kelly AP. Acne keloidalis nuchae: treatment with excision and second-intention healing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33(2 pt 1):243-246.

5. Kantor GR, Ratz JL, Wheeland RG. Treatment of acne keloidalis nuchae with carbon dioxide laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14(2 pt 1):263-267.

Cutaneous eruption on chest and back

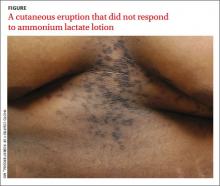

A 22-year-old African American man sought care at our clinic for an asymptomatic, “dirty-looking” rash on the epigastrium that had expanded and thickened over the previous 2 years. The rash hadn’t responded to scrubbing with soap and water, ammonium lactate lotion 12% BID, or over-the-counter moisturizing lotions.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis

This patient was given a diagnosis of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (CRP) based on the clinical presentation.

Although this condition is uncommon,1 we see it at least once a month in our dermatology clinic. CRP is characterized by centrally confluent and peripherally reticulated scaly brown plaques and papules that are cosmetically disfiguring.1

CRP usually is asymptomatic2 and primarily affects young adults—especially teenagers.3 It occurs in both males and females3 and it commonly occurs on the trunk.1,2

CRP is believed to be a disorder of keratinization. Malassezia furfur may induce CRP’s hyperproliferative epidermal changes, but systemic treatment that eliminates this organism does not clear CRP.3

Differential diagnosis includes acanthosis nigricans

Acanthosis nigricans (AN) shares similar “dirty” brown, confluent textural plaques, as well as nonspecific acanthosis and papillomatosis on histopathologic examination. However, AN affects flexural areas, whereas CRP typically is found on the epigastrium, central chest, and central back.1,2

Tinea versicolor (TV) and CRP are both brown in color, and occur in a similar distribution on the central back and chest.4 However, in contrast to the fine perifollicular scaling seen in TV, CRP is associated with textural, confluent plaques. TV also can be distinguished by its pathognomonic “spaghetti and meatball” pattern of hyphae and spores on potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation; KOH will be negative in patients with CRP. When a presumed case of TV does not respond to antifungal therapy, CRP should be considered.1

Making the diagnosis

A CRP diagnosis is made based on clinical presentation. The eruption usually begins as verrucous papules in the inframammary or epigastric region that enlarge to 4 to 5 mm in diameter and coalesce to form a confluent plaque with a peripheral reticulated pattern. CRP can extend over the back, chest, and abdomen to the neck, shoulders, and gluteal cleft. CRP does not affect the oral mucosa and rarely involves flexural areas.2 Although most cases are asymptomatic, mild pruritus may occur.1,2

A skin biopsy rarely is necessary for making a CRP diagnosis, but histopathologic findings include papillomatosis, hyperkeratosis, variable acanthosis, follicular plugging, and sparse dermal inflammation.1,3

Antibiotics usually clear this rash

Systemic antibiotics, most commonly minocycline 100 mg twice daily for 30 days or doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 30 days, are safe and effective for CRP.1,5 Sometimes treatment is extended for as long as 6 months. Although CRP usually responds to minocycline or doxycycline, it is believed that this is the result of these drugs’ anti-inflammatory—rather than antibiotic—properties.1,2,5 Azithromycin is an effective alternative therapy.2,5

There is a high rate of recurrence of CRP in patients after systemic antibiotics are discontinued.2 Uniform responses to treatment and retreatment of flares have solidified the belief that antibiotics are an effective suppressive if not curative therapy, despite a lack of randomized controlled trials.5

Our patient was treated with minocycline 100 mg BID. After 1 month, the rash had improved by 70%. In 3 months it was completely clear and the treatment was discontinued.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert T. Brodell, MD, Division of Dermatology, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216; rbrodell@umc.edu

1. Davis MD, Weenig RH, Camilleri MJ. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (Gougerot-Carteaud syndrome): a minocycline-responsive dermatosis without evidence for yeast in pathogenesis. A study of 39 patients and a proposal of diagnostic criteria. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:287-293.

2. Scheinfeld N. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis: a review of the literature. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7: 305-313.

3. Tamraz H, Raffoul M, Kurban M, et al. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis: clinical and histopathological study of 10 cases from Lebanon. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:e119-e123.

4. Hudacek KD, Haque MS, Hochberg AL, et al. An unusual variant of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis masquerading as tinea versicolor. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:505-508.

5. Jang HS, Oh CK, Cha JH, et al. Six cases of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis alleviated by various antibiotics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:652-655.

A 22-year-old African American man sought care at our clinic for an asymptomatic, “dirty-looking” rash on the epigastrium that had expanded and thickened over the previous 2 years. The rash hadn’t responded to scrubbing with soap and water, ammonium lactate lotion 12% BID, or over-the-counter moisturizing lotions.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis

This patient was given a diagnosis of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (CRP) based on the clinical presentation.

Although this condition is uncommon,1 we see it at least once a month in our dermatology clinic. CRP is characterized by centrally confluent and peripherally reticulated scaly brown plaques and papules that are cosmetically disfiguring.1

CRP usually is asymptomatic2 and primarily affects young adults—especially teenagers.3 It occurs in both males and females3 and it commonly occurs on the trunk.1,2

CRP is believed to be a disorder of keratinization. Malassezia furfur may induce CRP’s hyperproliferative epidermal changes, but systemic treatment that eliminates this organism does not clear CRP.3

Differential diagnosis includes acanthosis nigricans

Acanthosis nigricans (AN) shares similar “dirty” brown, confluent textural plaques, as well as nonspecific acanthosis and papillomatosis on histopathologic examination. However, AN affects flexural areas, whereas CRP typically is found on the epigastrium, central chest, and central back.1,2

Tinea versicolor (TV) and CRP are both brown in color, and occur in a similar distribution on the central back and chest.4 However, in contrast to the fine perifollicular scaling seen in TV, CRP is associated with textural, confluent plaques. TV also can be distinguished by its pathognomonic “spaghetti and meatball” pattern of hyphae and spores on potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation; KOH will be negative in patients with CRP. When a presumed case of TV does not respond to antifungal therapy, CRP should be considered.1

Making the diagnosis

A CRP diagnosis is made based on clinical presentation. The eruption usually begins as verrucous papules in the inframammary or epigastric region that enlarge to 4 to 5 mm in diameter and coalesce to form a confluent plaque with a peripheral reticulated pattern. CRP can extend over the back, chest, and abdomen to the neck, shoulders, and gluteal cleft. CRP does not affect the oral mucosa and rarely involves flexural areas.2 Although most cases are asymptomatic, mild pruritus may occur.1,2

A skin biopsy rarely is necessary for making a CRP diagnosis, but histopathologic findings include papillomatosis, hyperkeratosis, variable acanthosis, follicular plugging, and sparse dermal inflammation.1,3

Antibiotics usually clear this rash

Systemic antibiotics, most commonly minocycline 100 mg twice daily for 30 days or doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 30 days, are safe and effective for CRP.1,5 Sometimes treatment is extended for as long as 6 months. Although CRP usually responds to minocycline or doxycycline, it is believed that this is the result of these drugs’ anti-inflammatory—rather than antibiotic—properties.1,2,5 Azithromycin is an effective alternative therapy.2,5

There is a high rate of recurrence of CRP in patients after systemic antibiotics are discontinued.2 Uniform responses to treatment and retreatment of flares have solidified the belief that antibiotics are an effective suppressive if not curative therapy, despite a lack of randomized controlled trials.5

Our patient was treated with minocycline 100 mg BID. After 1 month, the rash had improved by 70%. In 3 months it was completely clear and the treatment was discontinued.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert T. Brodell, MD, Division of Dermatology, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216; rbrodell@umc.edu

A 22-year-old African American man sought care at our clinic for an asymptomatic, “dirty-looking” rash on the epigastrium that had expanded and thickened over the previous 2 years. The rash hadn’t responded to scrubbing with soap and water, ammonium lactate lotion 12% BID, or over-the-counter moisturizing lotions.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis

This patient was given a diagnosis of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (CRP) based on the clinical presentation.

Although this condition is uncommon,1 we see it at least once a month in our dermatology clinic. CRP is characterized by centrally confluent and peripherally reticulated scaly brown plaques and papules that are cosmetically disfiguring.1

CRP usually is asymptomatic2 and primarily affects young adults—especially teenagers.3 It occurs in both males and females3 and it commonly occurs on the trunk.1,2

CRP is believed to be a disorder of keratinization. Malassezia furfur may induce CRP’s hyperproliferative epidermal changes, but systemic treatment that eliminates this organism does not clear CRP.3

Differential diagnosis includes acanthosis nigricans

Acanthosis nigricans (AN) shares similar “dirty” brown, confluent textural plaques, as well as nonspecific acanthosis and papillomatosis on histopathologic examination. However, AN affects flexural areas, whereas CRP typically is found on the epigastrium, central chest, and central back.1,2

Tinea versicolor (TV) and CRP are both brown in color, and occur in a similar distribution on the central back and chest.4 However, in contrast to the fine perifollicular scaling seen in TV, CRP is associated with textural, confluent plaques. TV also can be distinguished by its pathognomonic “spaghetti and meatball” pattern of hyphae and spores on potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation; KOH will be negative in patients with CRP. When a presumed case of TV does not respond to antifungal therapy, CRP should be considered.1

Making the diagnosis

A CRP diagnosis is made based on clinical presentation. The eruption usually begins as verrucous papules in the inframammary or epigastric region that enlarge to 4 to 5 mm in diameter and coalesce to form a confluent plaque with a peripheral reticulated pattern. CRP can extend over the back, chest, and abdomen to the neck, shoulders, and gluteal cleft. CRP does not affect the oral mucosa and rarely involves flexural areas.2 Although most cases are asymptomatic, mild pruritus may occur.1,2

A skin biopsy rarely is necessary for making a CRP diagnosis, but histopathologic findings include papillomatosis, hyperkeratosis, variable acanthosis, follicular plugging, and sparse dermal inflammation.1,3

Antibiotics usually clear this rash

Systemic antibiotics, most commonly minocycline 100 mg twice daily for 30 days or doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 30 days, are safe and effective for CRP.1,5 Sometimes treatment is extended for as long as 6 months. Although CRP usually responds to minocycline or doxycycline, it is believed that this is the result of these drugs’ anti-inflammatory—rather than antibiotic—properties.1,2,5 Azithromycin is an effective alternative therapy.2,5

There is a high rate of recurrence of CRP in patients after systemic antibiotics are discontinued.2 Uniform responses to treatment and retreatment of flares have solidified the belief that antibiotics are an effective suppressive if not curative therapy, despite a lack of randomized controlled trials.5

Our patient was treated with minocycline 100 mg BID. After 1 month, the rash had improved by 70%. In 3 months it was completely clear and the treatment was discontinued.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert T. Brodell, MD, Division of Dermatology, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216; rbrodell@umc.edu

1. Davis MD, Weenig RH, Camilleri MJ. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (Gougerot-Carteaud syndrome): a minocycline-responsive dermatosis without evidence for yeast in pathogenesis. A study of 39 patients and a proposal of diagnostic criteria. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:287-293.

2. Scheinfeld N. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis: a review of the literature. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7: 305-313.

3. Tamraz H, Raffoul M, Kurban M, et al. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis: clinical and histopathological study of 10 cases from Lebanon. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:e119-e123.

4. Hudacek KD, Haque MS, Hochberg AL, et al. An unusual variant of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis masquerading as tinea versicolor. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:505-508.

5. Jang HS, Oh CK, Cha JH, et al. Six cases of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis alleviated by various antibiotics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:652-655.

1. Davis MD, Weenig RH, Camilleri MJ. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (Gougerot-Carteaud syndrome): a minocycline-responsive dermatosis without evidence for yeast in pathogenesis. A study of 39 patients and a proposal of diagnostic criteria. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:287-293.

2. Scheinfeld N. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis: a review of the literature. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7: 305-313.

3. Tamraz H, Raffoul M, Kurban M, et al. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis: clinical and histopathological study of 10 cases from Lebanon. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:e119-e123.

4. Hudacek KD, Haque MS, Hochberg AL, et al. An unusual variant of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis masquerading as tinea versicolor. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:505-508.

5. Jang HS, Oh CK, Cha JH, et al. Six cases of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis alleviated by various antibiotics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:652-655.

Young girl with lower leg rash

An 8-year-old girl was brought into our clinic for evaluation of a leg rash on her right lower leg that had been bothering her for 2 months. Another physician had performed a biopsy and diagnosed subacute spongiotic dermatitis, but the rash did not respond to treatment with triamcinolone cream 0.1% twice daily.

The rash was mildly tender and markedly pruritic. The girl had no history of trauma, prior skin conditions, or other areas with a similar rash. Physical examination revealed concentric annular lesions on the right lower leg (FIGURE). The central areas demonstrated a bruised appearance that did not resolve with diascopy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: tinea corporis

A potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation was performed. It showed septate hyphae and confirmed a diagnosis of tinea corporis. We ordered a periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stain on the previous biopsy specimen, and it revealed septate hyphae in the stratum corneum that were not apparent on the original hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained sections.

Dermatophyte infections of the skin are known as tinea corporis or “ringworm.” Ringworm fungi belong to 3 genera, Microsporum, Trichophyton, and Epidermophyton. These infections occur at any age and are more common in warmer climates.1 The classic lesion is an annular scaly patch, sometimes with the concentric rings, as seen in our patient (FIGURE). The bruising was almost certainly caused by rubbing and scratching.

We suspected tinea coporis based on the physical characteristics of the rash and the fact that it did not respond promptly to topical steroids. Our suspicions were confirmed by the KOH prep. Inked KOH using chlorazol black E stain turns fungal hyphae black, which makes them easier to distinguish from keratinocyte cell walls.2

Differential of a nonspecific rash should include infections

The initial misdiagnosis was based on the histopathologic diagnosis of spongiotic dermatitis. Subacute spongiotic dermatitis is associated with intracellular and intercellular edema of the keratinocytes in the epidermis. This is a nonspecific finding seen in eczematous dermatitis and can be etiologically associated with a wide variety of clinical conditions, including allergic contact dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, nummular eczema, and, in this case, dermatophytosis.3

If a biopsy is performed for a nonspecific rash, the pathologist should be advised of the possibility of superficial fungal infection. Providing a history and the physical characteristics of the rash or a differential diagnosis will prompt the performance of a PAS stain. Otherwise, the diagnosis can be missed because fungal elements are often not visible on routine H&E stains.

Proper treatment

provides speedy relief

Tinea corporis on a non-hair-bearing area is readily cleared with a topical azole antifungal agent, such as ketoconazole cream 2% twice daily for 2 weeks or a topical allylamine, such as terbinafine cream 1%, twice daily for 2 weeks. Topical allylamines may be more effective than topical azoles for tinea corporis4 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A). Hair-bearing areas such as the scalp, fingers, and toes are unlikely to respond to topically applied medications and require an oral anti-fungal medication, such as griseofulvin 15 to 20 mg/kg/d.5

Relief for our patient

Our patient’s rash was treated with griseofulvin oral suspension 20 mg/kg/d (with milk to enhance absorption) for 6 weeks. There was complete clearing and the condition did not recur.

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

1. Shrum JP, Millikan LE, Bataineh O. Superficial fungal infections in the tropics. Dermatol Clin. 1994;12:687-693.

2. Burke WA, Jones BE. A simple stain for rapid office diagnosis of fungus infections of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1519-1520.

3. Alsaad KO, Ghazarian D. My approach to superficial inflammatory dermatoses. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58:1233-1241.

4. Rotta I, Otuki MF, Sanches AC, et al. Efficacy of topical antifungal drugs in different dermatomycoses: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2012;58:308-318.

5. Noble SL, Forbes RC, Stamm PL. Diagnosis and management of common tinea infections. Am Fam Physician. 1998;58:163-174,177-178.

An 8-year-old girl was brought into our clinic for evaluation of a leg rash on her right lower leg that had been bothering her for 2 months. Another physician had performed a biopsy and diagnosed subacute spongiotic dermatitis, but the rash did not respond to treatment with triamcinolone cream 0.1% twice daily.

The rash was mildly tender and markedly pruritic. The girl had no history of trauma, prior skin conditions, or other areas with a similar rash. Physical examination revealed concentric annular lesions on the right lower leg (FIGURE). The central areas demonstrated a bruised appearance that did not resolve with diascopy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: tinea corporis

A potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation was performed. It showed septate hyphae and confirmed a diagnosis of tinea corporis. We ordered a periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stain on the previous biopsy specimen, and it revealed septate hyphae in the stratum corneum that were not apparent on the original hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained sections.

Dermatophyte infections of the skin are known as tinea corporis or “ringworm.” Ringworm fungi belong to 3 genera, Microsporum, Trichophyton, and Epidermophyton. These infections occur at any age and are more common in warmer climates.1 The classic lesion is an annular scaly patch, sometimes with the concentric rings, as seen in our patient (FIGURE). The bruising was almost certainly caused by rubbing and scratching.

We suspected tinea coporis based on the physical characteristics of the rash and the fact that it did not respond promptly to topical steroids. Our suspicions were confirmed by the KOH prep. Inked KOH using chlorazol black E stain turns fungal hyphae black, which makes them easier to distinguish from keratinocyte cell walls.2

Differential of a nonspecific rash should include infections

The initial misdiagnosis was based on the histopathologic diagnosis of spongiotic dermatitis. Subacute spongiotic dermatitis is associated with intracellular and intercellular edema of the keratinocytes in the epidermis. This is a nonspecific finding seen in eczematous dermatitis and can be etiologically associated with a wide variety of clinical conditions, including allergic contact dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, nummular eczema, and, in this case, dermatophytosis.3

If a biopsy is performed for a nonspecific rash, the pathologist should be advised of the possibility of superficial fungal infection. Providing a history and the physical characteristics of the rash or a differential diagnosis will prompt the performance of a PAS stain. Otherwise, the diagnosis can be missed because fungal elements are often not visible on routine H&E stains.

Proper treatment

provides speedy relief

Tinea corporis on a non-hair-bearing area is readily cleared with a topical azole antifungal agent, such as ketoconazole cream 2% twice daily for 2 weeks or a topical allylamine, such as terbinafine cream 1%, twice daily for 2 weeks. Topical allylamines may be more effective than topical azoles for tinea corporis4 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A). Hair-bearing areas such as the scalp, fingers, and toes are unlikely to respond to topically applied medications and require an oral anti-fungal medication, such as griseofulvin 15 to 20 mg/kg/d.5

Relief for our patient

Our patient’s rash was treated with griseofulvin oral suspension 20 mg/kg/d (with milk to enhance absorption) for 6 weeks. There was complete clearing and the condition did not recur.

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

An 8-year-old girl was brought into our clinic for evaluation of a leg rash on her right lower leg that had been bothering her for 2 months. Another physician had performed a biopsy and diagnosed subacute spongiotic dermatitis, but the rash did not respond to treatment with triamcinolone cream 0.1% twice daily.

The rash was mildly tender and markedly pruritic. The girl had no history of trauma, prior skin conditions, or other areas with a similar rash. Physical examination revealed concentric annular lesions on the right lower leg (FIGURE). The central areas demonstrated a bruised appearance that did not resolve with diascopy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: tinea corporis

A potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation was performed. It showed septate hyphae and confirmed a diagnosis of tinea corporis. We ordered a periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stain on the previous biopsy specimen, and it revealed septate hyphae in the stratum corneum that were not apparent on the original hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained sections.

Dermatophyte infections of the skin are known as tinea corporis or “ringworm.” Ringworm fungi belong to 3 genera, Microsporum, Trichophyton, and Epidermophyton. These infections occur at any age and are more common in warmer climates.1 The classic lesion is an annular scaly patch, sometimes with the concentric rings, as seen in our patient (FIGURE). The bruising was almost certainly caused by rubbing and scratching.

We suspected tinea coporis based on the physical characteristics of the rash and the fact that it did not respond promptly to topical steroids. Our suspicions were confirmed by the KOH prep. Inked KOH using chlorazol black E stain turns fungal hyphae black, which makes them easier to distinguish from keratinocyte cell walls.2

Differential of a nonspecific rash should include infections

The initial misdiagnosis was based on the histopathologic diagnosis of spongiotic dermatitis. Subacute spongiotic dermatitis is associated with intracellular and intercellular edema of the keratinocytes in the epidermis. This is a nonspecific finding seen in eczematous dermatitis and can be etiologically associated with a wide variety of clinical conditions, including allergic contact dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, nummular eczema, and, in this case, dermatophytosis.3

If a biopsy is performed for a nonspecific rash, the pathologist should be advised of the possibility of superficial fungal infection. Providing a history and the physical characteristics of the rash or a differential diagnosis will prompt the performance of a PAS stain. Otherwise, the diagnosis can be missed because fungal elements are often not visible on routine H&E stains.

Proper treatment

provides speedy relief

Tinea corporis on a non-hair-bearing area is readily cleared with a topical azole antifungal agent, such as ketoconazole cream 2% twice daily for 2 weeks or a topical allylamine, such as terbinafine cream 1%, twice daily for 2 weeks. Topical allylamines may be more effective than topical azoles for tinea corporis4 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A). Hair-bearing areas such as the scalp, fingers, and toes are unlikely to respond to topically applied medications and require an oral anti-fungal medication, such as griseofulvin 15 to 20 mg/kg/d.5

Relief for our patient

Our patient’s rash was treated with griseofulvin oral suspension 20 mg/kg/d (with milk to enhance absorption) for 6 weeks. There was complete clearing and the condition did not recur.

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

1. Shrum JP, Millikan LE, Bataineh O. Superficial fungal infections in the tropics. Dermatol Clin. 1994;12:687-693.

2. Burke WA, Jones BE. A simple stain for rapid office diagnosis of fungus infections of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1519-1520.

3. Alsaad KO, Ghazarian D. My approach to superficial inflammatory dermatoses. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58:1233-1241.

4. Rotta I, Otuki MF, Sanches AC, et al. Efficacy of topical antifungal drugs in different dermatomycoses: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2012;58:308-318.

5. Noble SL, Forbes RC, Stamm PL. Diagnosis and management of common tinea infections. Am Fam Physician. 1998;58:163-174,177-178.

1. Shrum JP, Millikan LE, Bataineh O. Superficial fungal infections in the tropics. Dermatol Clin. 1994;12:687-693.

2. Burke WA, Jones BE. A simple stain for rapid office diagnosis of fungus infections of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1519-1520.

3. Alsaad KO, Ghazarian D. My approach to superficial inflammatory dermatoses. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58:1233-1241.

4. Rotta I, Otuki MF, Sanches AC, et al. Efficacy of topical antifungal drugs in different dermatomycoses: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2012;58:308-318.

5. Noble SL, Forbes RC, Stamm PL. Diagnosis and management of common tinea infections. Am Fam Physician. 1998;58:163-174,177-178.

Adolescent with rash on face and scalp

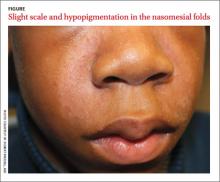

A 13-year-old African American male presented with a 2-year history of a mildly pruritic central facial rash (FIGURE) and dandruff. Recent treatment with hydrocortisone 1% cream and nystatin cream (100,000 U/gm) for 1 week resulted in no improvement.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Seborrheic dermatitis