User login

Richard Franki is the associate editor who writes and creates graphs. He started with the company in 1987, when it was known as the International Medical News Group. In his years as a journalist, Richard has worked for Cap Cities/ABC, Disney, Harcourt, Elsevier, Quadrant, Frontline, and Internet Brands. In the 1990s, he was a contributor to the ill-fated Indications column, predecessor of Livin' on the MDedge.

U.S. flu activity already at mid-season levels

according to the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention.

Nationally, 6% of all outpatient visits were because of flu or flu-like illness for the week of Nov. 13-19, up from 5.8% the previous week, the CDC’s Influenza Division said in its weekly FluView report.

Those figures are the highest recorded in November since 2009, but the peak of the 2009-10 flu season occurred even earlier – the week of Oct. 18-24 – and the rate of flu-like illness had already dropped to just over 4.0% by Nov. 15-21 that year and continued to drop thereafter.

Although COVID-19 and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) are included in the data from the CDC’s Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network, the agency did note that “seasonal influenza activity is elevated across the country” and estimated that “there have been at least 6.2 million illnesses, 53,000 hospitalizations, and 2,900 deaths from flu” during the 2022-23 season.

Total flu deaths include 11 reported in children as of Nov. 19, and children ages 0-4 had a higher proportion of visits for flu like-illness than other age groups.

The agency also said the cumulative hospitalization rate of 11.3 per 100,000 population “is higher than the rate observed in [the corresponding week of] every previous season since 2010-2011.” Adults 65 years and older have the highest cumulative rate, 25.9 per 100,000, for this year, compared with 20.7 for children 0-4; 11.1 for adults 50-64; 10.3 for children 5-17; and 5.6 for adults 18-49 years old, the CDC said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

according to the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention.

Nationally, 6% of all outpatient visits were because of flu or flu-like illness for the week of Nov. 13-19, up from 5.8% the previous week, the CDC’s Influenza Division said in its weekly FluView report.

Those figures are the highest recorded in November since 2009, but the peak of the 2009-10 flu season occurred even earlier – the week of Oct. 18-24 – and the rate of flu-like illness had already dropped to just over 4.0% by Nov. 15-21 that year and continued to drop thereafter.

Although COVID-19 and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) are included in the data from the CDC’s Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network, the agency did note that “seasonal influenza activity is elevated across the country” and estimated that “there have been at least 6.2 million illnesses, 53,000 hospitalizations, and 2,900 deaths from flu” during the 2022-23 season.

Total flu deaths include 11 reported in children as of Nov. 19, and children ages 0-4 had a higher proportion of visits for flu like-illness than other age groups.

The agency also said the cumulative hospitalization rate of 11.3 per 100,000 population “is higher than the rate observed in [the corresponding week of] every previous season since 2010-2011.” Adults 65 years and older have the highest cumulative rate, 25.9 per 100,000, for this year, compared with 20.7 for children 0-4; 11.1 for adults 50-64; 10.3 for children 5-17; and 5.6 for adults 18-49 years old, the CDC said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

according to the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention.

Nationally, 6% of all outpatient visits were because of flu or flu-like illness for the week of Nov. 13-19, up from 5.8% the previous week, the CDC’s Influenza Division said in its weekly FluView report.

Those figures are the highest recorded in November since 2009, but the peak of the 2009-10 flu season occurred even earlier – the week of Oct. 18-24 – and the rate of flu-like illness had already dropped to just over 4.0% by Nov. 15-21 that year and continued to drop thereafter.

Although COVID-19 and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) are included in the data from the CDC’s Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network, the agency did note that “seasonal influenza activity is elevated across the country” and estimated that “there have been at least 6.2 million illnesses, 53,000 hospitalizations, and 2,900 deaths from flu” during the 2022-23 season.

Total flu deaths include 11 reported in children as of Nov. 19, and children ages 0-4 had a higher proportion of visits for flu like-illness than other age groups.

The agency also said the cumulative hospitalization rate of 11.3 per 100,000 population “is higher than the rate observed in [the corresponding week of] every previous season since 2010-2011.” Adults 65 years and older have the highest cumulative rate, 25.9 per 100,000, for this year, compared with 20.7 for children 0-4; 11.1 for adults 50-64; 10.3 for children 5-17; and 5.6 for adults 18-49 years old, the CDC said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

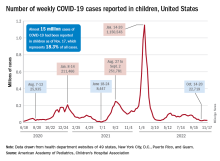

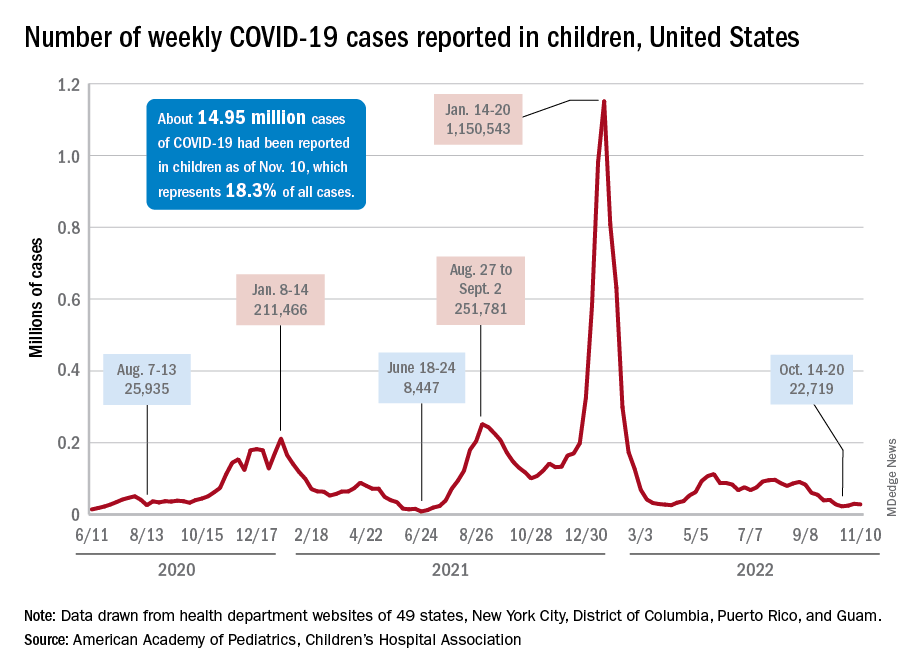

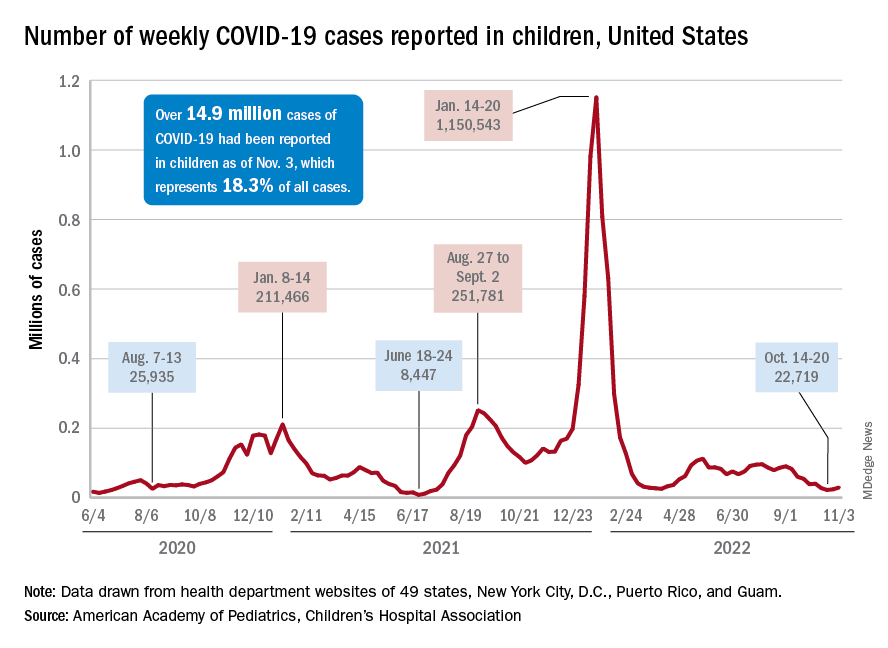

Children and COVID: Weekly cases maintain a low-level plateau

A less-than-1% decrease in weekly COVID-19 cases in children demonstrated continued stability in the pandemic situation as the nation heads into the holiday season.

the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in the latest edition of their joint COVID report.

New cases for the week of Nov. 11-17 totaled 27,899, down by 0.9% from the previous week and just 4 weeks removed from the lowest total of the year: 22,719 for Oct. 14-20. There have been just under 15 million cases of COVID-19 in children since the pandemic began, and children represent 18.3% of cases in all ages, the AAP and CHA reported.

Conditions look favorable for that plateau to continue, despite the upcoming holidays, White House COVID-19 coordinator Ashish Jha said recently. “We are in a very different place and we will remain in a different place,” Dr. Jha said, according to STAT News. “We are now at a point where I believe if you’re up to date on your vaccines, you have access to treatments ... there really should be no restrictions on people’s activities.”

One possible spoiler, an apparent spike in COVID-related hospitalizations in children we reported last week, seems to have been a false alarm. The rate of new admissions for Nov. 11, which preliminary data suggested was 0.48 per 100,000 population, has now been revised with more solid data to 0.20 per 100,000, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“We continue to monitor the recent increases in admissions among children. Some of these may be admissions with COVID-19, not because of COVID-19. Co-infections are being noted in our surveillance systems for hospitalizations among children; as much as 10% of admissions or higher have viruses codetected (RSV, influenza, enterovirus/rhinovirus, and other respiratory viruses),” a CDC spokesperson told this news organization.

For children aged 0-17 years, the current 7-day (Nov. 13-19) average number of new admissions with confirmed COVID is 129 per day, down from 147 for the previous 7-day average. Emergency department visits with diagnosed COVID, measured as a percentage of all ED visits, are largely holding steady. The latest 7-day averages available (Nov. 18) – 1.0% for children aged 0-11 years, 0.7% for 12- to 15-year-olds, and 0.8% in 16- to 17-year-olds – are the same or within a tenth of a percent of the rates recorded on Oct. 18, CDC data show.

New vaccinations for the week of Nov. 10-16 were down just slightly for children under age 5 years and for those aged 5-11 years, with a larger drop seen among 12- to 17-year-olds, the AAP said in its weekly vaccination report. So far, 7.9% of all children under age 5 have received at least one dose of COVID vaccine, as have 39.1% of 5 to 11-year-olds and 71.5% of those aged 12-17years, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

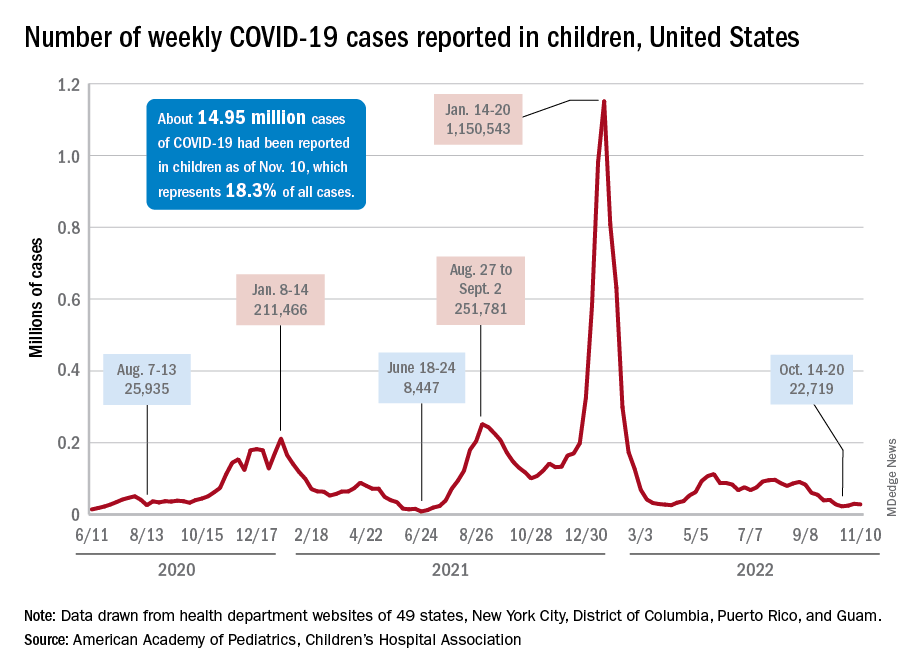

A less-than-1% decrease in weekly COVID-19 cases in children demonstrated continued stability in the pandemic situation as the nation heads into the holiday season.

the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in the latest edition of their joint COVID report.

New cases for the week of Nov. 11-17 totaled 27,899, down by 0.9% from the previous week and just 4 weeks removed from the lowest total of the year: 22,719 for Oct. 14-20. There have been just under 15 million cases of COVID-19 in children since the pandemic began, and children represent 18.3% of cases in all ages, the AAP and CHA reported.

Conditions look favorable for that plateau to continue, despite the upcoming holidays, White House COVID-19 coordinator Ashish Jha said recently. “We are in a very different place and we will remain in a different place,” Dr. Jha said, according to STAT News. “We are now at a point where I believe if you’re up to date on your vaccines, you have access to treatments ... there really should be no restrictions on people’s activities.”

One possible spoiler, an apparent spike in COVID-related hospitalizations in children we reported last week, seems to have been a false alarm. The rate of new admissions for Nov. 11, which preliminary data suggested was 0.48 per 100,000 population, has now been revised with more solid data to 0.20 per 100,000, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“We continue to monitor the recent increases in admissions among children. Some of these may be admissions with COVID-19, not because of COVID-19. Co-infections are being noted in our surveillance systems for hospitalizations among children; as much as 10% of admissions or higher have viruses codetected (RSV, influenza, enterovirus/rhinovirus, and other respiratory viruses),” a CDC spokesperson told this news organization.

For children aged 0-17 years, the current 7-day (Nov. 13-19) average number of new admissions with confirmed COVID is 129 per day, down from 147 for the previous 7-day average. Emergency department visits with diagnosed COVID, measured as a percentage of all ED visits, are largely holding steady. The latest 7-day averages available (Nov. 18) – 1.0% for children aged 0-11 years, 0.7% for 12- to 15-year-olds, and 0.8% in 16- to 17-year-olds – are the same or within a tenth of a percent of the rates recorded on Oct. 18, CDC data show.

New vaccinations for the week of Nov. 10-16 were down just slightly for children under age 5 years and for those aged 5-11 years, with a larger drop seen among 12- to 17-year-olds, the AAP said in its weekly vaccination report. So far, 7.9% of all children under age 5 have received at least one dose of COVID vaccine, as have 39.1% of 5 to 11-year-olds and 71.5% of those aged 12-17years, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

A less-than-1% decrease in weekly COVID-19 cases in children demonstrated continued stability in the pandemic situation as the nation heads into the holiday season.

the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in the latest edition of their joint COVID report.

New cases for the week of Nov. 11-17 totaled 27,899, down by 0.9% from the previous week and just 4 weeks removed from the lowest total of the year: 22,719 for Oct. 14-20. There have been just under 15 million cases of COVID-19 in children since the pandemic began, and children represent 18.3% of cases in all ages, the AAP and CHA reported.

Conditions look favorable for that plateau to continue, despite the upcoming holidays, White House COVID-19 coordinator Ashish Jha said recently. “We are in a very different place and we will remain in a different place,” Dr. Jha said, according to STAT News. “We are now at a point where I believe if you’re up to date on your vaccines, you have access to treatments ... there really should be no restrictions on people’s activities.”

One possible spoiler, an apparent spike in COVID-related hospitalizations in children we reported last week, seems to have been a false alarm. The rate of new admissions for Nov. 11, which preliminary data suggested was 0.48 per 100,000 population, has now been revised with more solid data to 0.20 per 100,000, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“We continue to monitor the recent increases in admissions among children. Some of these may be admissions with COVID-19, not because of COVID-19. Co-infections are being noted in our surveillance systems for hospitalizations among children; as much as 10% of admissions or higher have viruses codetected (RSV, influenza, enterovirus/rhinovirus, and other respiratory viruses),” a CDC spokesperson told this news organization.

For children aged 0-17 years, the current 7-day (Nov. 13-19) average number of new admissions with confirmed COVID is 129 per day, down from 147 for the previous 7-day average. Emergency department visits with diagnosed COVID, measured as a percentage of all ED visits, are largely holding steady. The latest 7-day averages available (Nov. 18) – 1.0% for children aged 0-11 years, 0.7% for 12- to 15-year-olds, and 0.8% in 16- to 17-year-olds – are the same or within a tenth of a percent of the rates recorded on Oct. 18, CDC data show.

New vaccinations for the week of Nov. 10-16 were down just slightly for children under age 5 years and for those aged 5-11 years, with a larger drop seen among 12- to 17-year-olds, the AAP said in its weekly vaccination report. So far, 7.9% of all children under age 5 have received at least one dose of COVID vaccine, as have 39.1% of 5 to 11-year-olds and 71.5% of those aged 12-17years, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

Give bacterial diversity a chance: The antibiotic dichotomy

What’s the opposite of an antibiotic?

Everyone knows that LOTME loves a good dichotomy: yin/yang, good/evil, heads/tails, particle/wave, peanut butter/jelly. They’re all great. We’re also big fans of microbiomes, particularly the gut microbiome. But what if we could combine the two? A healthy and nutritious story about the gut microbiome, with a dash of added dichotomy for flavor. Is such a thing even possible? Let’s find out.

First, we need an antibiotic, a drug designed to fight bacterial infections. If you’ve got strep throat, otitis media, or bubonic plague, there’s a good chance you will receive an antibiotic. That antibiotic will kill the bad bacteria that are making you sick, but it will also kill a lot of the good bacteria that inhabit your gut microbiome, which results in side effects like bloating and diarrhea.

It comes down to diversity, explained Elisa Marroquin, PhD, of Texas Christian University (Go Horned Frogs!): “In a human community, we need people that have different professions because we don’t all know how to do every single job. And so the same happens with bacteria. We need lots of different gut bacteria that know how to do different things.”

She and her colleagues reviewed 29 studies published over the last 7 years and found a way to preserve the diversity of a human gut microbiome that’s dealing with an antibiotic. Their solution? Prescribe a probiotic.

The way to fight the effects of stopping a bacterial infection is to provide food for what are, basically, other bacterial infections. Antibiotic/probiotic is a prescription for dichotomy, and it means we managed to combine gut microbiomes with a dichotomy. And you didn’t think we could do it.

The earphone of hearing aids

It’s estimated that up to 75% of people who need hearing aids don’t wear them. Why? Well, there’s the social stigma about not wanting to appear too old, and then there’s the cost factor.

Is there a cheaper, less stigmatizing option to amplify hearing? The answer, according to otolaryngologist Yen-fu Cheng, MD, of Taipei Veterans General Hospital and associates, is wireless earphones. AirPods, if you want to be brand specific.

Airpods can be on the more expensive side – running about $129 for AirPods 2 and $249 for AirPods Pro – but when compared with premium hearing aids ($10,000), or even basic aids (about $1,500), the Apple products come off inexpensive after all.

The team tested the premium and basic hearing aids against the AirPods 2 and the AirPod Pro using Apple’s Live Listen feature, which helps amplify sound through the company’s wireless earphones and iPhones and was initially designed to assist people with normal hearing in situations such as birdwatching.

The AirPods Pro worked just as well as the basic hearing aid but not quite as well as the premium hearing aid in a quiet setting, while the AirPods 2 performed the worst. When tested in a noisy setting, the AirPods Pro was pretty comparable to the premium hearing aid, as long as the noise came from a lateral direction. Neither of the AirPod models did as well as the hearing aids with head-on noises.

Wireless earbuds may not be the perfect solution from a clinical standpoint, but they’re a good start for people who don’t have access to hearing aids, Dr. Cheng noted.

So who says headphones damage your hearing? They might actually help.

Now I lay me down to sleep, I pray the computer my soul to keep

Radiation is the boring hazard of space travel. No one dies in a space horror movie because they’ve been slowly exposed to too much cosmic radiation. It’s always “thrown out the airlock” this and “eaten by a xenomorph” that.

Radiation, however, is not something that can be ignored, but it turns out that a potential solution is another science fiction staple: artificial hibernation. Generally in sci-fi, hibernation is a plot convenience to get people from point A to point B in a ship that doesn’t break the laws of physics. Here on Earth, though, it is well known that animals naturally entering a state of torpor during hibernation gain significant resistance to radiation.

The problem, of course, is that humans don’t hibernate, and no matter how hard people who work 100-hour weeks for Elon Musk try, sleeping for months on end is simply something we can’t do. However, a new study shows that it’s possible to induce this torpor state in animals that don’t naturally hibernate. By injecting rats with adenosine 5’-monophosphate monohydrate and keeping them in a room held at 16° C, an international team of scientists successfully induced a synthetic torpor state.

That’s not all they did: The scientists also exposed the hibernating rats to a large dose of radiation approximating that found in deep space. Which isn’t something we’d like to explain to our significant other when we got home from work. “So how was your day?” “Oh, I irradiated a bunch of sleeping rats. … Don’t worry they’re fine!” Which they were. Thanks to the hypoxic and hypothermic state, the tissue was spared damage from the high-energy ion radiation.

Obviously, there’s a big difference between a rat and a human and a lot of work to be done, but the study does show that artificial hibernation is possible. Perhaps one day we’ll be able to fall asleep and wake up light-years away under an alien sky, and we won’t be horrifically mutated or riddled with cancer. If, however, you find yourself in hibernation on your way to Jupiter (or Saturn) to investigate a mysterious black monolith, we suggest sleeping with one eye open and gripping your pillow tight.

What’s the opposite of an antibiotic?

Everyone knows that LOTME loves a good dichotomy: yin/yang, good/evil, heads/tails, particle/wave, peanut butter/jelly. They’re all great. We’re also big fans of microbiomes, particularly the gut microbiome. But what if we could combine the two? A healthy and nutritious story about the gut microbiome, with a dash of added dichotomy for flavor. Is such a thing even possible? Let’s find out.

First, we need an antibiotic, a drug designed to fight bacterial infections. If you’ve got strep throat, otitis media, or bubonic plague, there’s a good chance you will receive an antibiotic. That antibiotic will kill the bad bacteria that are making you sick, but it will also kill a lot of the good bacteria that inhabit your gut microbiome, which results in side effects like bloating and diarrhea.

It comes down to diversity, explained Elisa Marroquin, PhD, of Texas Christian University (Go Horned Frogs!): “In a human community, we need people that have different professions because we don’t all know how to do every single job. And so the same happens with bacteria. We need lots of different gut bacteria that know how to do different things.”

She and her colleagues reviewed 29 studies published over the last 7 years and found a way to preserve the diversity of a human gut microbiome that’s dealing with an antibiotic. Their solution? Prescribe a probiotic.

The way to fight the effects of stopping a bacterial infection is to provide food for what are, basically, other bacterial infections. Antibiotic/probiotic is a prescription for dichotomy, and it means we managed to combine gut microbiomes with a dichotomy. And you didn’t think we could do it.

The earphone of hearing aids

It’s estimated that up to 75% of people who need hearing aids don’t wear them. Why? Well, there’s the social stigma about not wanting to appear too old, and then there’s the cost factor.

Is there a cheaper, less stigmatizing option to amplify hearing? The answer, according to otolaryngologist Yen-fu Cheng, MD, of Taipei Veterans General Hospital and associates, is wireless earphones. AirPods, if you want to be brand specific.

Airpods can be on the more expensive side – running about $129 for AirPods 2 and $249 for AirPods Pro – but when compared with premium hearing aids ($10,000), or even basic aids (about $1,500), the Apple products come off inexpensive after all.

The team tested the premium and basic hearing aids against the AirPods 2 and the AirPod Pro using Apple’s Live Listen feature, which helps amplify sound through the company’s wireless earphones and iPhones and was initially designed to assist people with normal hearing in situations such as birdwatching.

The AirPods Pro worked just as well as the basic hearing aid but not quite as well as the premium hearing aid in a quiet setting, while the AirPods 2 performed the worst. When tested in a noisy setting, the AirPods Pro was pretty comparable to the premium hearing aid, as long as the noise came from a lateral direction. Neither of the AirPod models did as well as the hearing aids with head-on noises.

Wireless earbuds may not be the perfect solution from a clinical standpoint, but they’re a good start for people who don’t have access to hearing aids, Dr. Cheng noted.

So who says headphones damage your hearing? They might actually help.

Now I lay me down to sleep, I pray the computer my soul to keep

Radiation is the boring hazard of space travel. No one dies in a space horror movie because they’ve been slowly exposed to too much cosmic radiation. It’s always “thrown out the airlock” this and “eaten by a xenomorph” that.

Radiation, however, is not something that can be ignored, but it turns out that a potential solution is another science fiction staple: artificial hibernation. Generally in sci-fi, hibernation is a plot convenience to get people from point A to point B in a ship that doesn’t break the laws of physics. Here on Earth, though, it is well known that animals naturally entering a state of torpor during hibernation gain significant resistance to radiation.

The problem, of course, is that humans don’t hibernate, and no matter how hard people who work 100-hour weeks for Elon Musk try, sleeping for months on end is simply something we can’t do. However, a new study shows that it’s possible to induce this torpor state in animals that don’t naturally hibernate. By injecting rats with adenosine 5’-monophosphate monohydrate and keeping them in a room held at 16° C, an international team of scientists successfully induced a synthetic torpor state.

That’s not all they did: The scientists also exposed the hibernating rats to a large dose of radiation approximating that found in deep space. Which isn’t something we’d like to explain to our significant other when we got home from work. “So how was your day?” “Oh, I irradiated a bunch of sleeping rats. … Don’t worry they’re fine!” Which they were. Thanks to the hypoxic and hypothermic state, the tissue was spared damage from the high-energy ion radiation.

Obviously, there’s a big difference between a rat and a human and a lot of work to be done, but the study does show that artificial hibernation is possible. Perhaps one day we’ll be able to fall asleep and wake up light-years away under an alien sky, and we won’t be horrifically mutated or riddled with cancer. If, however, you find yourself in hibernation on your way to Jupiter (or Saturn) to investigate a mysterious black monolith, we suggest sleeping with one eye open and gripping your pillow tight.

What’s the opposite of an antibiotic?

Everyone knows that LOTME loves a good dichotomy: yin/yang, good/evil, heads/tails, particle/wave, peanut butter/jelly. They’re all great. We’re also big fans of microbiomes, particularly the gut microbiome. But what if we could combine the two? A healthy and nutritious story about the gut microbiome, with a dash of added dichotomy for flavor. Is such a thing even possible? Let’s find out.

First, we need an antibiotic, a drug designed to fight bacterial infections. If you’ve got strep throat, otitis media, or bubonic plague, there’s a good chance you will receive an antibiotic. That antibiotic will kill the bad bacteria that are making you sick, but it will also kill a lot of the good bacteria that inhabit your gut microbiome, which results in side effects like bloating and diarrhea.

It comes down to diversity, explained Elisa Marroquin, PhD, of Texas Christian University (Go Horned Frogs!): “In a human community, we need people that have different professions because we don’t all know how to do every single job. And so the same happens with bacteria. We need lots of different gut bacteria that know how to do different things.”

She and her colleagues reviewed 29 studies published over the last 7 years and found a way to preserve the diversity of a human gut microbiome that’s dealing with an antibiotic. Their solution? Prescribe a probiotic.

The way to fight the effects of stopping a bacterial infection is to provide food for what are, basically, other bacterial infections. Antibiotic/probiotic is a prescription for dichotomy, and it means we managed to combine gut microbiomes with a dichotomy. And you didn’t think we could do it.

The earphone of hearing aids

It’s estimated that up to 75% of people who need hearing aids don’t wear them. Why? Well, there’s the social stigma about not wanting to appear too old, and then there’s the cost factor.

Is there a cheaper, less stigmatizing option to amplify hearing? The answer, according to otolaryngologist Yen-fu Cheng, MD, of Taipei Veterans General Hospital and associates, is wireless earphones. AirPods, if you want to be brand specific.

Airpods can be on the more expensive side – running about $129 for AirPods 2 and $249 for AirPods Pro – but when compared with premium hearing aids ($10,000), or even basic aids (about $1,500), the Apple products come off inexpensive after all.

The team tested the premium and basic hearing aids against the AirPods 2 and the AirPod Pro using Apple’s Live Listen feature, which helps amplify sound through the company’s wireless earphones and iPhones and was initially designed to assist people with normal hearing in situations such as birdwatching.

The AirPods Pro worked just as well as the basic hearing aid but not quite as well as the premium hearing aid in a quiet setting, while the AirPods 2 performed the worst. When tested in a noisy setting, the AirPods Pro was pretty comparable to the premium hearing aid, as long as the noise came from a lateral direction. Neither of the AirPod models did as well as the hearing aids with head-on noises.

Wireless earbuds may not be the perfect solution from a clinical standpoint, but they’re a good start for people who don’t have access to hearing aids, Dr. Cheng noted.

So who says headphones damage your hearing? They might actually help.

Now I lay me down to sleep, I pray the computer my soul to keep

Radiation is the boring hazard of space travel. No one dies in a space horror movie because they’ve been slowly exposed to too much cosmic radiation. It’s always “thrown out the airlock” this and “eaten by a xenomorph” that.

Radiation, however, is not something that can be ignored, but it turns out that a potential solution is another science fiction staple: artificial hibernation. Generally in sci-fi, hibernation is a plot convenience to get people from point A to point B in a ship that doesn’t break the laws of physics. Here on Earth, though, it is well known that animals naturally entering a state of torpor during hibernation gain significant resistance to radiation.

The problem, of course, is that humans don’t hibernate, and no matter how hard people who work 100-hour weeks for Elon Musk try, sleeping for months on end is simply something we can’t do. However, a new study shows that it’s possible to induce this torpor state in animals that don’t naturally hibernate. By injecting rats with adenosine 5’-monophosphate monohydrate and keeping them in a room held at 16° C, an international team of scientists successfully induced a synthetic torpor state.

That’s not all they did: The scientists also exposed the hibernating rats to a large dose of radiation approximating that found in deep space. Which isn’t something we’d like to explain to our significant other when we got home from work. “So how was your day?” “Oh, I irradiated a bunch of sleeping rats. … Don’t worry they’re fine!” Which they were. Thanks to the hypoxic and hypothermic state, the tissue was spared damage from the high-energy ion radiation.

Obviously, there’s a big difference between a rat and a human and a lot of work to be done, but the study does show that artificial hibernation is possible. Perhaps one day we’ll be able to fall asleep and wake up light-years away under an alien sky, and we won’t be horrifically mutated or riddled with cancer. If, however, you find yourself in hibernation on your way to Jupiter (or Saturn) to investigate a mysterious black monolith, we suggest sleeping with one eye open and gripping your pillow tight.

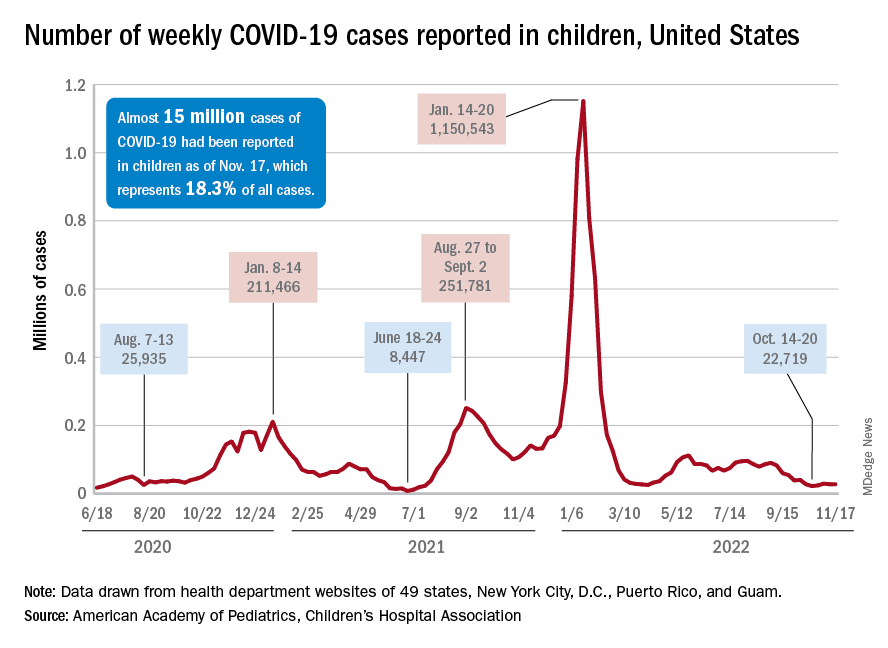

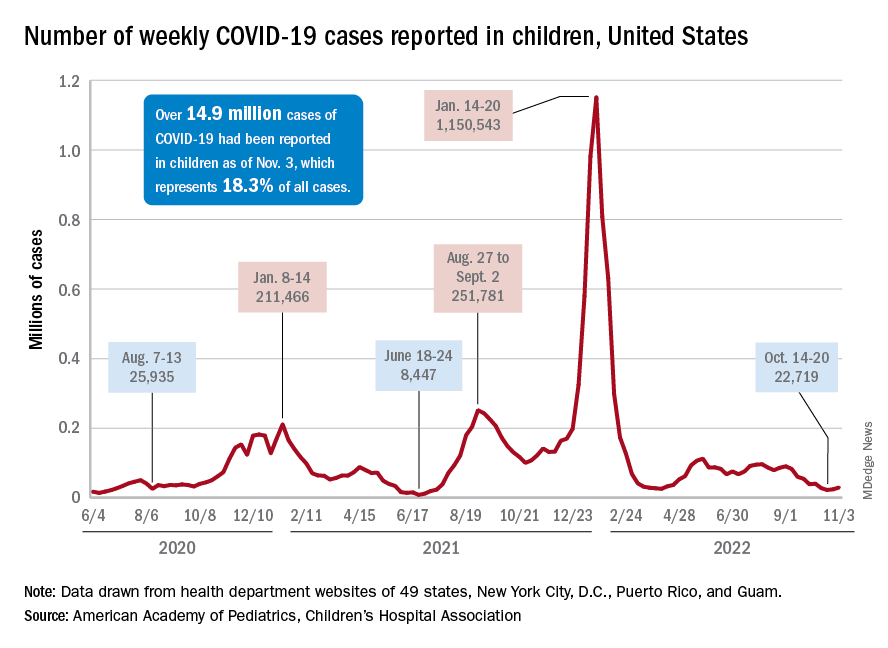

Children and COVID: Weekly cases continue to hold fairly steady

The incidence of new COVID-19 cases in children seems to have stabilized as the national count remained under 30,000 for the fifth consecutive week, but hospitalization data may indicate some possible turbulence.

Just over 28,000 pediatric cases were reported during the week of Nov. 4-10, a drop of 5.4% from the previous week, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly COVID-19 report involving data from state and territorial health departments, several of which are no longer updating their websites.

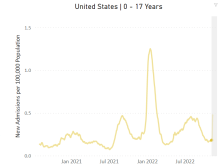

The stability in weekly cases, however, comes in contrast to a very recent and considerable increase in new hospital admissions of children aged 0-17 years with confirmed COVID-19. That rate, which was 0.18 hospitalizations per 100,000 population on Nov. 7 and 0.19 per 100,000 on Nov. 8 and 9, jumped all the way to 0.34 on Nov. 10 and 0.48 on Nov. 11, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That is the highest rate since the closing days of the Omicron surge in February.

The rate for Nov. 12, the most recent one available, was down slightly to 0.47 admissions per 100,000. There doesn’t seem to be any evidence in the CDC’s data of a similar sudden increase in new hospitalizations among any other age group, and no age group, including children, shows any sign of a recent increase in emergency department visits with diagnosed COVID. (The CDC has not yet responded to our inquiry about this development.)

The two most recent 7-day averages for new admissions in children aged 0-17 show a small increase, but they cover the periods of Oct. 15 to Oct. 31, when there were 126 admissions per day, and Nov. 1 to Nov. 7, when the average went up to 133 per day, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

The CDC does not publish a weekly count of new COVID cases, but its latest data on the rate of incident cases seem to agree with the AAP/CHA figures: A gradual decline in all age groups, including children, since the beginning of September.

Vaccinations, on the other hand, bucked their recent trend and increased in the last week. About 43,000 children under age 5 years received their initial dose of COVID vaccine during Nov. 3-9, compared with 30,000 and 33,000 the 2 previous weeks, while 5- to 11-year-olds hit their highest weekly mark (31,000) since late August and 12- to 17-year-olds had their biggest week (27,000) since mid-August, the AAP reported based on CDC data.

The incidence of new COVID-19 cases in children seems to have stabilized as the national count remained under 30,000 for the fifth consecutive week, but hospitalization data may indicate some possible turbulence.

Just over 28,000 pediatric cases were reported during the week of Nov. 4-10, a drop of 5.4% from the previous week, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly COVID-19 report involving data from state and territorial health departments, several of which are no longer updating their websites.

The stability in weekly cases, however, comes in contrast to a very recent and considerable increase in new hospital admissions of children aged 0-17 years with confirmed COVID-19. That rate, which was 0.18 hospitalizations per 100,000 population on Nov. 7 and 0.19 per 100,000 on Nov. 8 and 9, jumped all the way to 0.34 on Nov. 10 and 0.48 on Nov. 11, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That is the highest rate since the closing days of the Omicron surge in February.

The rate for Nov. 12, the most recent one available, was down slightly to 0.47 admissions per 100,000. There doesn’t seem to be any evidence in the CDC’s data of a similar sudden increase in new hospitalizations among any other age group, and no age group, including children, shows any sign of a recent increase in emergency department visits with diagnosed COVID. (The CDC has not yet responded to our inquiry about this development.)

The two most recent 7-day averages for new admissions in children aged 0-17 show a small increase, but they cover the periods of Oct. 15 to Oct. 31, when there were 126 admissions per day, and Nov. 1 to Nov. 7, when the average went up to 133 per day, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

The CDC does not publish a weekly count of new COVID cases, but its latest data on the rate of incident cases seem to agree with the AAP/CHA figures: A gradual decline in all age groups, including children, since the beginning of September.

Vaccinations, on the other hand, bucked their recent trend and increased in the last week. About 43,000 children under age 5 years received their initial dose of COVID vaccine during Nov. 3-9, compared with 30,000 and 33,000 the 2 previous weeks, while 5- to 11-year-olds hit their highest weekly mark (31,000) since late August and 12- to 17-year-olds had their biggest week (27,000) since mid-August, the AAP reported based on CDC data.

The incidence of new COVID-19 cases in children seems to have stabilized as the national count remained under 30,000 for the fifth consecutive week, but hospitalization data may indicate some possible turbulence.

Just over 28,000 pediatric cases were reported during the week of Nov. 4-10, a drop of 5.4% from the previous week, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly COVID-19 report involving data from state and territorial health departments, several of which are no longer updating their websites.

The stability in weekly cases, however, comes in contrast to a very recent and considerable increase in new hospital admissions of children aged 0-17 years with confirmed COVID-19. That rate, which was 0.18 hospitalizations per 100,000 population on Nov. 7 and 0.19 per 100,000 on Nov. 8 and 9, jumped all the way to 0.34 on Nov. 10 and 0.48 on Nov. 11, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That is the highest rate since the closing days of the Omicron surge in February.

The rate for Nov. 12, the most recent one available, was down slightly to 0.47 admissions per 100,000. There doesn’t seem to be any evidence in the CDC’s data of a similar sudden increase in new hospitalizations among any other age group, and no age group, including children, shows any sign of a recent increase in emergency department visits with diagnosed COVID. (The CDC has not yet responded to our inquiry about this development.)

The two most recent 7-day averages for new admissions in children aged 0-17 show a small increase, but they cover the periods of Oct. 15 to Oct. 31, when there were 126 admissions per day, and Nov. 1 to Nov. 7, when the average went up to 133 per day, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

The CDC does not publish a weekly count of new COVID cases, but its latest data on the rate of incident cases seem to agree with the AAP/CHA figures: A gradual decline in all age groups, including children, since the beginning of September.

Vaccinations, on the other hand, bucked their recent trend and increased in the last week. About 43,000 children under age 5 years received their initial dose of COVID vaccine during Nov. 3-9, compared with 30,000 and 33,000 the 2 previous weeks, while 5- to 11-year-olds hit their highest weekly mark (31,000) since late August and 12- to 17-year-olds had their biggest week (27,000) since mid-August, the AAP reported based on CDC data.

Have you heard the one about the emergency dept. that called 911?

Who watches the ED staff?

We heard a really great joke recently, one we simply have to share.

A man in Seattle went to a therapist. “I’m depressed,” he says. “Depressed, overworked, and lonely.”

“Oh dear, that sounds quite serious,” the therapist replies. “Tell me all about it.”

“Life just seems so harsh and cruel,” the man explains. “The pandemic has caused 300,000 health care workers across the country to leave the industry.”

“Such as the doctor typically filling this role in the joke,” the therapist, who is not licensed to prescribe medicine, nods.

“Exactly! And with so many respiratory viruses circulating and COVID still hanging around, emergency departments all over the country are facing massive backups. People are waiting outside the hospital for hours, hoping a bed will open up. Things got so bad at a hospital near Seattle in October that a nurse called 911 on her own ED. Told the 911 operator to send the fire department to help out, since they were ‘drowning’ and ‘in dire straits.’ They had 45 patients waiting and only five nurses to take care of them.”

“That is quite serious,” the therapist says, scribbling down unseen notes.

“The fire chief did send a crew out, and they cleaned rooms, changed beds, and took vitals for 90 minutes until the crisis passed,” the man says. “But it’s only a matter of time before it happens again. The hospital president said they have 300 open positions, and literally no one has applied to work in the emergency department. Not one person.”

“And how does all this make you feel?” the therapist asks.

“I feel all alone,” the man says. “This world feels so threatening, like no one cares, and I have no idea what will come next. It’s so vague and uncertain.”

“Ah, I think I have a solution for you,” the therapist says. “Go to the emergency department at St. Michael Medical Center in Silverdale, near Seattle. They’ll get your bad mood all settled, and they’ll prescribe you the medicine you need to relax.”

The man bursts into tears. “You don’t understand,” he says. “I am the emergency department at St. Michael Medical Center.”

Good joke. Everybody laugh. Roll on snare drum. Curtains.

Myth buster: Supplements for cholesterol lowering

When it comes to that nasty low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, some people swear by supplements over statins as a holistic approach. Well, we’re busting the myth that those heart-healthy supplements are even effective in comparison.

Which supplements are we talking about? These six are always on sale at the pharmacy: fish oil, cinnamon, garlic, turmeric, plant sterols, and red yeast rice.

In a study presented at the recent American Heart Association scientific sessions, researchers compared these supplements’ effectiveness in lowering LDL cholesterol with low-dose rosuvastatin or placebo among 199 adults aged 40-75 years who didn’t have a personal history of cardiovascular disease.

Participants who took the statin for 28 days had an average of 24% decrease in total cholesterol and a 38% reduction in LDL cholesterol, while 28 days’ worth of the supplements did no better than the placebo in either measure. Compared with placebo, the plant sterols supplement notably lowered HDL cholesterol and the garlic supplement notably increased LDL cholesterol.

Even though there are other studies showing the validity of plant sterols and red yeast rice to lower LDL cholesterol, author Luke J. Laffin, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic noted that this study shows how supplement results can vary and that more research is needed to see the effect they truly have on cholesterol over time.

So, should you stop taking or recommending supplements for heart health or healthy cholesterol levels? Well, we’re not going to come to your house and raid your medicine cabinet, but the authors of this study are definitely not saying that you should rely on them.

Consider this myth mostly busted.

COVID dept. of unintended consequences, part 2

The surveillance testing programs conducted in the first year of the pandemic were, in theory, meant to keep everyone safer. Someone, apparently, forgot to explain that to the students of the University of Wyoming and the University of Idaho.

We’re all familiar with the drill: Students at the two schools had to undergo frequent COVID screening to keep the virus from spreading, thereby making everyone safer. Duck your head now, because here comes the unintended consequence.

The students who didn’t get COVID eventually, and perhaps not so surprisingly, “perceived that the mandatory testing policy decreased their risk of contracting COVID-19, and … this perception led to higher participation in COVID-risky events,” Chian Jones Ritten, PhD, and associates said in PNAS Nexus.

They surveyed 757 students from the Univ. of Washington and 517 from the Univ. of Idaho and found that those who were tested more frequently perceived that they were less likely to contract the virus. Those respondents also more frequently attended indoor gatherings, both small and large, and spent more time in restaurants and bars.

The investigators did not mince words: “From a public health standpoint, such behavior is problematic.”

Current parents/participants in the workforce might have other ideas about an appropriate response to COVID.

At this point, we probably should mention that appropriation is the second-most sincere form of flattery.

Who watches the ED staff?

We heard a really great joke recently, one we simply have to share.

A man in Seattle went to a therapist. “I’m depressed,” he says. “Depressed, overworked, and lonely.”

“Oh dear, that sounds quite serious,” the therapist replies. “Tell me all about it.”

“Life just seems so harsh and cruel,” the man explains. “The pandemic has caused 300,000 health care workers across the country to leave the industry.”

“Such as the doctor typically filling this role in the joke,” the therapist, who is not licensed to prescribe medicine, nods.

“Exactly! And with so many respiratory viruses circulating and COVID still hanging around, emergency departments all over the country are facing massive backups. People are waiting outside the hospital for hours, hoping a bed will open up. Things got so bad at a hospital near Seattle in October that a nurse called 911 on her own ED. Told the 911 operator to send the fire department to help out, since they were ‘drowning’ and ‘in dire straits.’ They had 45 patients waiting and only five nurses to take care of them.”

“That is quite serious,” the therapist says, scribbling down unseen notes.

“The fire chief did send a crew out, and they cleaned rooms, changed beds, and took vitals for 90 minutes until the crisis passed,” the man says. “But it’s only a matter of time before it happens again. The hospital president said they have 300 open positions, and literally no one has applied to work in the emergency department. Not one person.”

“And how does all this make you feel?” the therapist asks.

“I feel all alone,” the man says. “This world feels so threatening, like no one cares, and I have no idea what will come next. It’s so vague and uncertain.”

“Ah, I think I have a solution for you,” the therapist says. “Go to the emergency department at St. Michael Medical Center in Silverdale, near Seattle. They’ll get your bad mood all settled, and they’ll prescribe you the medicine you need to relax.”

The man bursts into tears. “You don’t understand,” he says. “I am the emergency department at St. Michael Medical Center.”

Good joke. Everybody laugh. Roll on snare drum. Curtains.

Myth buster: Supplements for cholesterol lowering

When it comes to that nasty low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, some people swear by supplements over statins as a holistic approach. Well, we’re busting the myth that those heart-healthy supplements are even effective in comparison.

Which supplements are we talking about? These six are always on sale at the pharmacy: fish oil, cinnamon, garlic, turmeric, plant sterols, and red yeast rice.

In a study presented at the recent American Heart Association scientific sessions, researchers compared these supplements’ effectiveness in lowering LDL cholesterol with low-dose rosuvastatin or placebo among 199 adults aged 40-75 years who didn’t have a personal history of cardiovascular disease.

Participants who took the statin for 28 days had an average of 24% decrease in total cholesterol and a 38% reduction in LDL cholesterol, while 28 days’ worth of the supplements did no better than the placebo in either measure. Compared with placebo, the plant sterols supplement notably lowered HDL cholesterol and the garlic supplement notably increased LDL cholesterol.

Even though there are other studies showing the validity of plant sterols and red yeast rice to lower LDL cholesterol, author Luke J. Laffin, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic noted that this study shows how supplement results can vary and that more research is needed to see the effect they truly have on cholesterol over time.

So, should you stop taking or recommending supplements for heart health or healthy cholesterol levels? Well, we’re not going to come to your house and raid your medicine cabinet, but the authors of this study are definitely not saying that you should rely on them.

Consider this myth mostly busted.

COVID dept. of unintended consequences, part 2

The surveillance testing programs conducted in the first year of the pandemic were, in theory, meant to keep everyone safer. Someone, apparently, forgot to explain that to the students of the University of Wyoming and the University of Idaho.

We’re all familiar with the drill: Students at the two schools had to undergo frequent COVID screening to keep the virus from spreading, thereby making everyone safer. Duck your head now, because here comes the unintended consequence.

The students who didn’t get COVID eventually, and perhaps not so surprisingly, “perceived that the mandatory testing policy decreased their risk of contracting COVID-19, and … this perception led to higher participation in COVID-risky events,” Chian Jones Ritten, PhD, and associates said in PNAS Nexus.

They surveyed 757 students from the Univ. of Washington and 517 from the Univ. of Idaho and found that those who were tested more frequently perceived that they were less likely to contract the virus. Those respondents also more frequently attended indoor gatherings, both small and large, and spent more time in restaurants and bars.

The investigators did not mince words: “From a public health standpoint, such behavior is problematic.”

Current parents/participants in the workforce might have other ideas about an appropriate response to COVID.

At this point, we probably should mention that appropriation is the second-most sincere form of flattery.

Who watches the ED staff?

We heard a really great joke recently, one we simply have to share.

A man in Seattle went to a therapist. “I’m depressed,” he says. “Depressed, overworked, and lonely.”

“Oh dear, that sounds quite serious,” the therapist replies. “Tell me all about it.”

“Life just seems so harsh and cruel,” the man explains. “The pandemic has caused 300,000 health care workers across the country to leave the industry.”

“Such as the doctor typically filling this role in the joke,” the therapist, who is not licensed to prescribe medicine, nods.

“Exactly! And with so many respiratory viruses circulating and COVID still hanging around, emergency departments all over the country are facing massive backups. People are waiting outside the hospital for hours, hoping a bed will open up. Things got so bad at a hospital near Seattle in October that a nurse called 911 on her own ED. Told the 911 operator to send the fire department to help out, since they were ‘drowning’ and ‘in dire straits.’ They had 45 patients waiting and only five nurses to take care of them.”

“That is quite serious,” the therapist says, scribbling down unseen notes.

“The fire chief did send a crew out, and they cleaned rooms, changed beds, and took vitals for 90 minutes until the crisis passed,” the man says. “But it’s only a matter of time before it happens again. The hospital president said they have 300 open positions, and literally no one has applied to work in the emergency department. Not one person.”

“And how does all this make you feel?” the therapist asks.

“I feel all alone,” the man says. “This world feels so threatening, like no one cares, and I have no idea what will come next. It’s so vague and uncertain.”

“Ah, I think I have a solution for you,” the therapist says. “Go to the emergency department at St. Michael Medical Center in Silverdale, near Seattle. They’ll get your bad mood all settled, and they’ll prescribe you the medicine you need to relax.”

The man bursts into tears. “You don’t understand,” he says. “I am the emergency department at St. Michael Medical Center.”

Good joke. Everybody laugh. Roll on snare drum. Curtains.

Myth buster: Supplements for cholesterol lowering

When it comes to that nasty low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, some people swear by supplements over statins as a holistic approach. Well, we’re busting the myth that those heart-healthy supplements are even effective in comparison.

Which supplements are we talking about? These six are always on sale at the pharmacy: fish oil, cinnamon, garlic, turmeric, plant sterols, and red yeast rice.

In a study presented at the recent American Heart Association scientific sessions, researchers compared these supplements’ effectiveness in lowering LDL cholesterol with low-dose rosuvastatin or placebo among 199 adults aged 40-75 years who didn’t have a personal history of cardiovascular disease.

Participants who took the statin for 28 days had an average of 24% decrease in total cholesterol and a 38% reduction in LDL cholesterol, while 28 days’ worth of the supplements did no better than the placebo in either measure. Compared with placebo, the plant sterols supplement notably lowered HDL cholesterol and the garlic supplement notably increased LDL cholesterol.

Even though there are other studies showing the validity of plant sterols and red yeast rice to lower LDL cholesterol, author Luke J. Laffin, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic noted that this study shows how supplement results can vary and that more research is needed to see the effect they truly have on cholesterol over time.

So, should you stop taking or recommending supplements for heart health or healthy cholesterol levels? Well, we’re not going to come to your house and raid your medicine cabinet, but the authors of this study are definitely not saying that you should rely on them.

Consider this myth mostly busted.

COVID dept. of unintended consequences, part 2

The surveillance testing programs conducted in the first year of the pandemic were, in theory, meant to keep everyone safer. Someone, apparently, forgot to explain that to the students of the University of Wyoming and the University of Idaho.

We’re all familiar with the drill: Students at the two schools had to undergo frequent COVID screening to keep the virus from spreading, thereby making everyone safer. Duck your head now, because here comes the unintended consequence.

The students who didn’t get COVID eventually, and perhaps not so surprisingly, “perceived that the mandatory testing policy decreased their risk of contracting COVID-19, and … this perception led to higher participation in COVID-risky events,” Chian Jones Ritten, PhD, and associates said in PNAS Nexus.

They surveyed 757 students from the Univ. of Washington and 517 from the Univ. of Idaho and found that those who were tested more frequently perceived that they were less likely to contract the virus. Those respondents also more frequently attended indoor gatherings, both small and large, and spent more time in restaurants and bars.

The investigators did not mince words: “From a public health standpoint, such behavior is problematic.”

Current parents/participants in the workforce might have other ideas about an appropriate response to COVID.

At this point, we probably should mention that appropriation is the second-most sincere form of flattery.

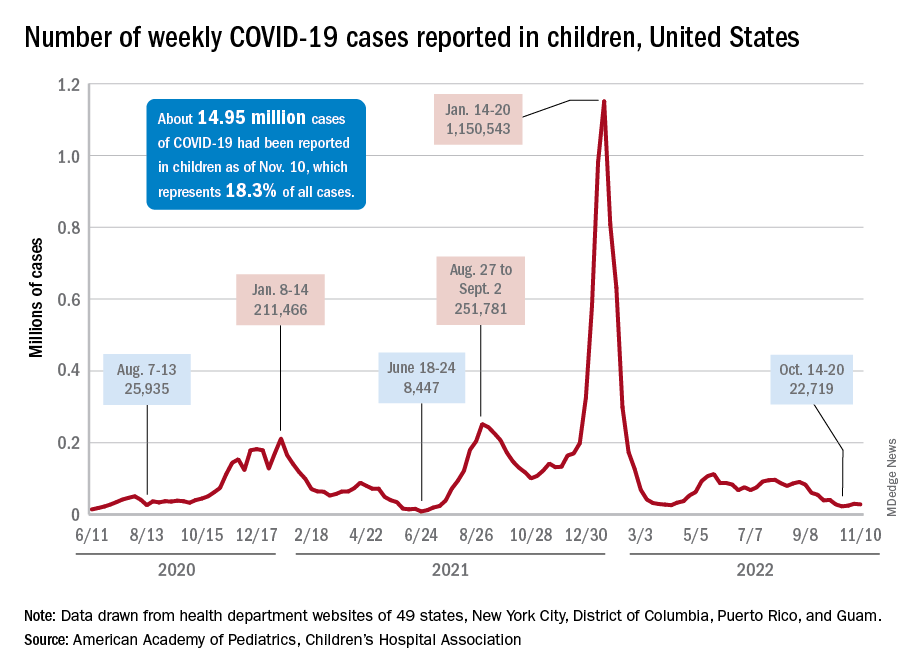

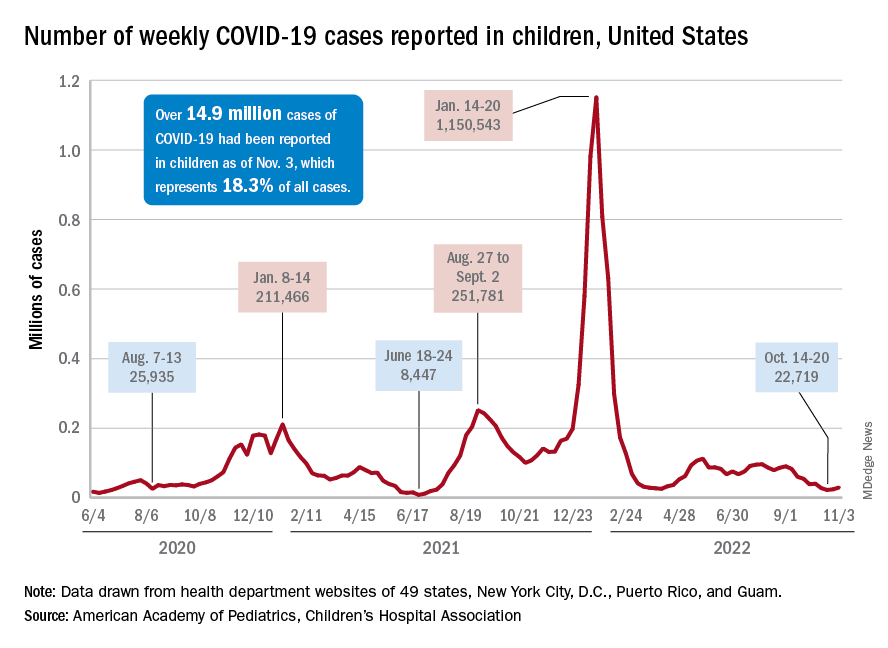

Children and COVID: New cases increase for second straight week

New COVID-19 cases rose among U.S. children for the second consecutive week, while hospitals saw signs of renewed activity on the part of SARS-CoV-2.

, when the count fell to its lowest level in more than a year, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their joint report.

The 7-day average for ED visits with diagnosed COVID was down to just 0.6% of all ED visits for 12- to 15-year-olds as late as Oct. 23 but has moved up to 0.7% since then. Among those aged 16-17 years, the 7-day average was also down to 0.6% for just one day, Oct. 19, but was up to 0.8% as of Nov. 4. So far, though, a similar increase has not yet occurred for ED visits among children aged 0-11 years, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

The trend is discernible, however, when looking at hospitalizations of children with confirmed COVID. The rate of new admissions of children aged 0-17 years was 0.16 per 100,000 population as late as Oct. 23 but ticked up a notch after that and has been 0.17 per 100,000 since, according to the CDC. As with the ED rate, hospitalizations had been steadily declining since late August.

Vaccine initiation continues to slow

During the week of Oct. 27 to Nov. 2, about 30,000 children under 5 years of age received their initial COVID vaccination. A month earlier (Sept. 29 to Oct. 5), that number was about 40,000. A month before that, about 53,000 children aged 0-5 years received their initial dose, the AAP said in a separate vaccination report based on CDC data.

All of that reduced interest adds up to 7.4% of the age group having received at least one dose and just 3.2% being fully vaccinated as of Nov. 2. Among children aged 5-11 years, the corresponding vaccination rates are 38.9% and 31.8%, while those aged 12-17 years are at 71.3% and 61.1%, the CDC said.

Looking at just the first 20 weeks of the vaccination experience for each age group shows that 1.6 million children under 5 years of age had received at least an initial dose, compared with 8.1 million children aged 5-11 years and 8.1 million children aged 12-15, the AAP said.

New COVID-19 cases rose among U.S. children for the second consecutive week, while hospitals saw signs of renewed activity on the part of SARS-CoV-2.

, when the count fell to its lowest level in more than a year, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their joint report.

The 7-day average for ED visits with diagnosed COVID was down to just 0.6% of all ED visits for 12- to 15-year-olds as late as Oct. 23 but has moved up to 0.7% since then. Among those aged 16-17 years, the 7-day average was also down to 0.6% for just one day, Oct. 19, but was up to 0.8% as of Nov. 4. So far, though, a similar increase has not yet occurred for ED visits among children aged 0-11 years, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

The trend is discernible, however, when looking at hospitalizations of children with confirmed COVID. The rate of new admissions of children aged 0-17 years was 0.16 per 100,000 population as late as Oct. 23 but ticked up a notch after that and has been 0.17 per 100,000 since, according to the CDC. As with the ED rate, hospitalizations had been steadily declining since late August.

Vaccine initiation continues to slow

During the week of Oct. 27 to Nov. 2, about 30,000 children under 5 years of age received their initial COVID vaccination. A month earlier (Sept. 29 to Oct. 5), that number was about 40,000. A month before that, about 53,000 children aged 0-5 years received their initial dose, the AAP said in a separate vaccination report based on CDC data.

All of that reduced interest adds up to 7.4% of the age group having received at least one dose and just 3.2% being fully vaccinated as of Nov. 2. Among children aged 5-11 years, the corresponding vaccination rates are 38.9% and 31.8%, while those aged 12-17 years are at 71.3% and 61.1%, the CDC said.

Looking at just the first 20 weeks of the vaccination experience for each age group shows that 1.6 million children under 5 years of age had received at least an initial dose, compared with 8.1 million children aged 5-11 years and 8.1 million children aged 12-15, the AAP said.

New COVID-19 cases rose among U.S. children for the second consecutive week, while hospitals saw signs of renewed activity on the part of SARS-CoV-2.

, when the count fell to its lowest level in more than a year, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their joint report.

The 7-day average for ED visits with diagnosed COVID was down to just 0.6% of all ED visits for 12- to 15-year-olds as late as Oct. 23 but has moved up to 0.7% since then. Among those aged 16-17 years, the 7-day average was also down to 0.6% for just one day, Oct. 19, but was up to 0.8% as of Nov. 4. So far, though, a similar increase has not yet occurred for ED visits among children aged 0-11 years, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

The trend is discernible, however, when looking at hospitalizations of children with confirmed COVID. The rate of new admissions of children aged 0-17 years was 0.16 per 100,000 population as late as Oct. 23 but ticked up a notch after that and has been 0.17 per 100,000 since, according to the CDC. As with the ED rate, hospitalizations had been steadily declining since late August.

Vaccine initiation continues to slow

During the week of Oct. 27 to Nov. 2, about 30,000 children under 5 years of age received their initial COVID vaccination. A month earlier (Sept. 29 to Oct. 5), that number was about 40,000. A month before that, about 53,000 children aged 0-5 years received their initial dose, the AAP said in a separate vaccination report based on CDC data.

All of that reduced interest adds up to 7.4% of the age group having received at least one dose and just 3.2% being fully vaccinated as of Nov. 2. Among children aged 5-11 years, the corresponding vaccination rates are 38.9% and 31.8%, while those aged 12-17 years are at 71.3% and 61.1%, the CDC said.

Looking at just the first 20 weeks of the vaccination experience for each age group shows that 1.6 million children under 5 years of age had received at least an initial dose, compared with 8.1 million children aged 5-11 years and 8.1 million children aged 12-15, the AAP said.

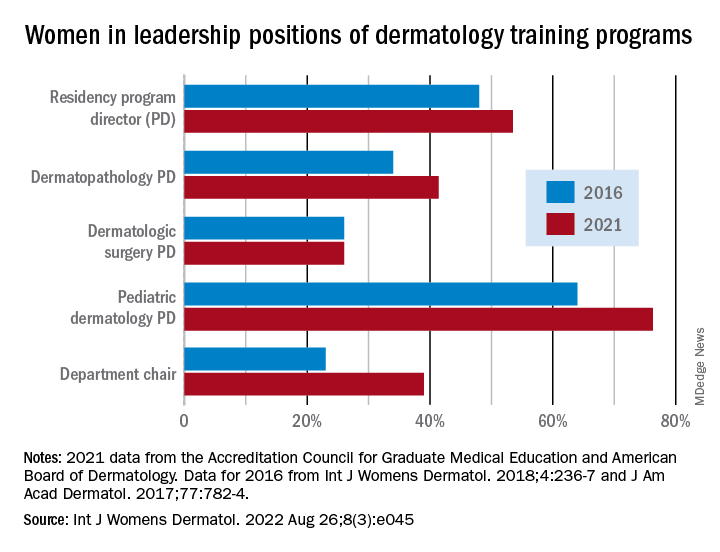

Academic dermatology: Gender diversity advances as some gaps persist

, according to a recent cross-sectional study.

Although women made up more than half of the dermatology residency program directors (53.5%), associate directors (62.6%), and assistant directors (58.3%) in 2021, those numbers fall short of women’s majority (65% in 2018) among the trainees themselves, Yasmine Abushukur of Oakland University in Rochester, Mich., and associates said in a research letter.

Advancements were “made in gender diversity within academic dermatology from 2016 to 2021, [but] women remain underrepresented, particularly in leadership of dermatopathology and dermatologic surgery fellowships,” the investigators wrote.

Data gathered from 142 dermatology residency programs accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education show that progress has been made since 2016, at least among program directors (PDs), of whom 48% were women, according to a previous study. Data on associate and assistant PDs from 2016 were not available to Ms. Abushukur and associates.

At the fellowship program level, women made gains as PDs in dermatopathology (34% in 2016 and 41% in 2021) and pediatric dermatology (64% in 2016 and 76% in 2021), but not in dermatologic surgery, where the proportion held at 26% over the study period. “This disparity is reflective of the general trend in surgery and pathology leadership nationally,” the researchers noted.

Taking a couple of steps up the ladder of authority shows that 39% of dermatology chairs were women in 2021, compared with 23% in 2016. A study published in 2016 demonstrated decreased diversity among academic faculty members as faculty rank increased, and “our data mirror this sentiment by demonstrating a majority of women in assistant and associate PD positions, with a minority of women chairs,” they wrote.

The investigators said that they had no conflicts of interest and no outside funding. Ms. Abushukur’s coauthors were from the departments of dermatology at the Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, and Wayne State University, Dearborn, Mich.

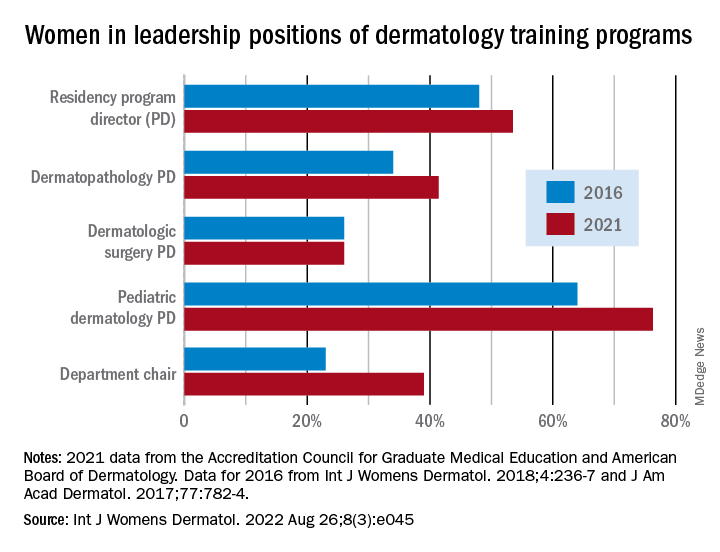

, according to a recent cross-sectional study.

Although women made up more than half of the dermatology residency program directors (53.5%), associate directors (62.6%), and assistant directors (58.3%) in 2021, those numbers fall short of women’s majority (65% in 2018) among the trainees themselves, Yasmine Abushukur of Oakland University in Rochester, Mich., and associates said in a research letter.

Advancements were “made in gender diversity within academic dermatology from 2016 to 2021, [but] women remain underrepresented, particularly in leadership of dermatopathology and dermatologic surgery fellowships,” the investigators wrote.

Data gathered from 142 dermatology residency programs accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education show that progress has been made since 2016, at least among program directors (PDs), of whom 48% were women, according to a previous study. Data on associate and assistant PDs from 2016 were not available to Ms. Abushukur and associates.

At the fellowship program level, women made gains as PDs in dermatopathology (34% in 2016 and 41% in 2021) and pediatric dermatology (64% in 2016 and 76% in 2021), but not in dermatologic surgery, where the proportion held at 26% over the study period. “This disparity is reflective of the general trend in surgery and pathology leadership nationally,” the researchers noted.

Taking a couple of steps up the ladder of authority shows that 39% of dermatology chairs were women in 2021, compared with 23% in 2016. A study published in 2016 demonstrated decreased diversity among academic faculty members as faculty rank increased, and “our data mirror this sentiment by demonstrating a majority of women in assistant and associate PD positions, with a minority of women chairs,” they wrote.

The investigators said that they had no conflicts of interest and no outside funding. Ms. Abushukur’s coauthors were from the departments of dermatology at the Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, and Wayne State University, Dearborn, Mich.

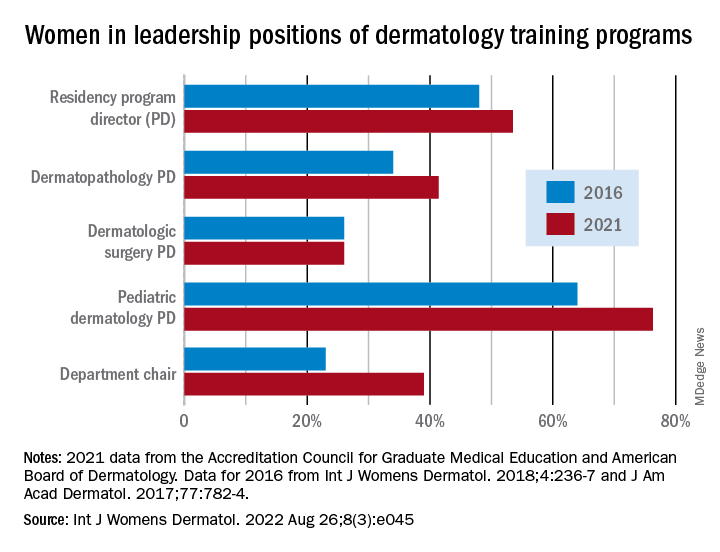

, according to a recent cross-sectional study.

Although women made up more than half of the dermatology residency program directors (53.5%), associate directors (62.6%), and assistant directors (58.3%) in 2021, those numbers fall short of women’s majority (65% in 2018) among the trainees themselves, Yasmine Abushukur of Oakland University in Rochester, Mich., and associates said in a research letter.

Advancements were “made in gender diversity within academic dermatology from 2016 to 2021, [but] women remain underrepresented, particularly in leadership of dermatopathology and dermatologic surgery fellowships,” the investigators wrote.

Data gathered from 142 dermatology residency programs accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education show that progress has been made since 2016, at least among program directors (PDs), of whom 48% were women, according to a previous study. Data on associate and assistant PDs from 2016 were not available to Ms. Abushukur and associates.

At the fellowship program level, women made gains as PDs in dermatopathology (34% in 2016 and 41% in 2021) and pediatric dermatology (64% in 2016 and 76% in 2021), but not in dermatologic surgery, where the proportion held at 26% over the study period. “This disparity is reflective of the general trend in surgery and pathology leadership nationally,” the researchers noted.

Taking a couple of steps up the ladder of authority shows that 39% of dermatology chairs were women in 2021, compared with 23% in 2016. A study published in 2016 demonstrated decreased diversity among academic faculty members as faculty rank increased, and “our data mirror this sentiment by demonstrating a majority of women in assistant and associate PD positions, with a minority of women chairs,” they wrote.

The investigators said that they had no conflicts of interest and no outside funding. Ms. Abushukur’s coauthors were from the departments of dermatology at the Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, and Wayne State University, Dearborn, Mich.

FROM INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF WOMEN’S DERMATOLOGY

The truth of alcohol consequences

Bad drinking consequence No. 87: Joining the LOTME team

Alcohol and college students go together like peanut butter and jelly. Or peanut butter and chocolate. Or peanut butter and toothpaste. Peanut butter goes with a lot of things.

Naturally, when you combine alcohol and college students, bad decisions are sure to follow. But have you ever wondered just how many bad decisions alcohol causes? A team of researchers from Penn State University, the undisputed champion of poor drinking decisions (trust us, we know), sure has. They’ve even conducted a 4-year study of 1,700 students as they carved a drunken swath through the many fine local drinking establishments, such as East Halls or that one frat house that hosts medieval battle–style ping pong tournaments.

The students were surveyed twice a year throughout the study, and the researchers compiled a list of all the various consequences their subjects experienced. Ultimately, college students will experience an average of 102 consequences from drinking during their 4-year college careers, which is an impressive number. Try thinking up a hundred consequences for anything.

Some consequences are less common than others – we imagine “missing the Renaissance Faire because you felt drunker the morning after than while you were drinking” is pretty low on the list – but more than 96% of students reported that they’d experienced a hangover and that drinking had caused them to say or do embarrassing things. Also, more than 70% said they needed additional alcohol to feel any effect, a potential sign of alcohol use disorder.

Once they had their list, the researchers focused on 12 of the more common and severe consequences, such as blacking out, hangovers, and missing work/class, and asked the study participants how their parents would react to their drinking and those specific consequences. Students who believed their parents would disapprove of alcohol-related consequences actually experienced fewer consequences overall.

College students, it seems, really do care what their parents think, even if they don’t express it, the researchers said. That gives space for parents to offer advice about the consequences of hard drinking, making decisions while drunk, or bringing godawful Fireball whiskey to parties. Seriously, don’t do that. Stuff’s bad, and you should feel bad for bringing it. Your parents raised you better than that.

COVID ‘expert’ discusses data sharing

We interrupt our regularly scheduled programming to bring you this special news event. Elon Musk, the world’s second-most annoying human, is holding a press conference to discuss, of all things, COVID-19.

Reporter: Hey, Mr. Musketeer, what qualifies you to talk about a global pandemic?

EM: As the official king of the Twitterverse, I’m pretty much an expert on any topic.

Reporter: Okay then, Mr. Muskmelon, what can you tell us about the new study in Agricultural Economics, which looked at consumers’ knowledge of local COVID infection rates and their willingness to eat at restaurants?

EM: Well, I know that one of the investigators, Rigoberto Lopez, PhD, of the University of Connecticut, said “no news is bad news.” Restaurants located in cities where local regulations required COVID tracking recovered faster than those in areas that did not, according to data from 87 restaurants in 10 Chinese cities that were gathered between Dec. 1, 2019, and March 27, 2020. Having access to local infection rate data made customers more comfortable going out to eat, the investigators explained.

Second reporter: Interesting, Mr. Muskox, but how about this headline from CNN: “Workers flee China’s biggest iPhone factory over Covid outbreak”? Do you agree with analysts, who said that “the chaos at Zhengzhou could jeopardize Apple and Foxconn’s output in the coming weeks,” as CNN put it?

EM: I did see that a manager at Foxconn, which owns the factory and is known to its friends as Hon Hai Precision Industry, told a Chinese media outlet that “workers are panicking over the spread of the virus at the factory and lack of access to official information.” As we’ve already discussed, no news is bad news.

That’s all the time I have to chat with you today. I’m off to fire some more Twitter employees.

In case you hadn’t already guessed, Vlad Putin is officially more annoying than Elon Musk. We now return to this week’s typical LOTME shenanigans, already in progress.

The deadliest month

With climate change making the world hotter, leading to more heat stroke and organ failure, you would think the summer months would be the most deadly. In reality, though, it’s quite the opposite.

There are multiple factors that make January the most deadly month out of the year, as LiveScience discovered in a recent analysis.

Let’s go through them, shall we?

Respiratory viruses: Robert Glatter, MD, of Lenox Hill Hospital in New York, told LiveScence that winter is the time for illnesses like the flu, bacterial pneumonia, and RSV. Millions of people worldwide die from the flu, according to the CDC. And the World Health Organization reported lower respiratory infections as the fourth-leading cause of death worldwide before COVID came along.

Heart disease: Heart conditions are actually more fatal in the winter months, according to a study published in Circulation. The cold puts more stress on the heart to keep the body warm, which can be a challenge for people who already have preexisting heart conditions.

Space heaters: Dr. Glatter also told Live Science that the use of space heaters could be a factor in the cold winter months since they can lead to carbon monoxide poisoning and even fires. Silent killers.

Holiday season: A time for joy and merriment, certainly, but Christmas et al. have their downsides. By January we’re coming off a 3-month food and alcohol binge, which leads to cardiac stress. There’s also the psychological stress that comes with the season. Sometimes the most wonderful time of the year just isn’t.

So even though summer is hot, fall has hurricanes, and spring tends to have the highest suicide rate, winter still ends up being the deadliest season.

Bad drinking consequence No. 87: Joining the LOTME team

Alcohol and college students go together like peanut butter and jelly. Or peanut butter and chocolate. Or peanut butter and toothpaste. Peanut butter goes with a lot of things.

Naturally, when you combine alcohol and college students, bad decisions are sure to follow. But have you ever wondered just how many bad decisions alcohol causes? A team of researchers from Penn State University, the undisputed champion of poor drinking decisions (trust us, we know), sure has. They’ve even conducted a 4-year study of 1,700 students as they carved a drunken swath through the many fine local drinking establishments, such as East Halls or that one frat house that hosts medieval battle–style ping pong tournaments.

The students were surveyed twice a year throughout the study, and the researchers compiled a list of all the various consequences their subjects experienced. Ultimately, college students will experience an average of 102 consequences from drinking during their 4-year college careers, which is an impressive number. Try thinking up a hundred consequences for anything.

Some consequences are less common than others – we imagine “missing the Renaissance Faire because you felt drunker the morning after than while you were drinking” is pretty low on the list – but more than 96% of students reported that they’d experienced a hangover and that drinking had caused them to say or do embarrassing things. Also, more than 70% said they needed additional alcohol to feel any effect, a potential sign of alcohol use disorder.

Once they had their list, the researchers focused on 12 of the more common and severe consequences, such as blacking out, hangovers, and missing work/class, and asked the study participants how their parents would react to their drinking and those specific consequences. Students who believed their parents would disapprove of alcohol-related consequences actually experienced fewer consequences overall.

College students, it seems, really do care what their parents think, even if they don’t express it, the researchers said. That gives space for parents to offer advice about the consequences of hard drinking, making decisions while drunk, or bringing godawful Fireball whiskey to parties. Seriously, don’t do that. Stuff’s bad, and you should feel bad for bringing it. Your parents raised you better than that.

COVID ‘expert’ discusses data sharing

We interrupt our regularly scheduled programming to bring you this special news event. Elon Musk, the world’s second-most annoying human, is holding a press conference to discuss, of all things, COVID-19.

Reporter: Hey, Mr. Musketeer, what qualifies you to talk about a global pandemic?

EM: As the official king of the Twitterverse, I’m pretty much an expert on any topic.

Reporter: Okay then, Mr. Muskmelon, what can you tell us about the new study in Agricultural Economics, which looked at consumers’ knowledge of local COVID infection rates and their willingness to eat at restaurants?

EM: Well, I know that one of the investigators, Rigoberto Lopez, PhD, of the University of Connecticut, said “no news is bad news.” Restaurants located in cities where local regulations required COVID tracking recovered faster than those in areas that did not, according to data from 87 restaurants in 10 Chinese cities that were gathered between Dec. 1, 2019, and March 27, 2020. Having access to local infection rate data made customers more comfortable going out to eat, the investigators explained.

Second reporter: Interesting, Mr. Muskox, but how about this headline from CNN: “Workers flee China’s biggest iPhone factory over Covid outbreak”? Do you agree with analysts, who said that “the chaos at Zhengzhou could jeopardize Apple and Foxconn’s output in the coming weeks,” as CNN put it?

EM: I did see that a manager at Foxconn, which owns the factory and is known to its friends as Hon Hai Precision Industry, told a Chinese media outlet that “workers are panicking over the spread of the virus at the factory and lack of access to official information.” As we’ve already discussed, no news is bad news.

That’s all the time I have to chat with you today. I’m off to fire some more Twitter employees.

In case you hadn’t already guessed, Vlad Putin is officially more annoying than Elon Musk. We now return to this week’s typical LOTME shenanigans, already in progress.

The deadliest month

With climate change making the world hotter, leading to more heat stroke and organ failure, you would think the summer months would be the most deadly. In reality, though, it’s quite the opposite.

There are multiple factors that make January the most deadly month out of the year, as LiveScience discovered in a recent analysis.

Let’s go through them, shall we?

Respiratory viruses: Robert Glatter, MD, of Lenox Hill Hospital in New York, told LiveScence that winter is the time for illnesses like the flu, bacterial pneumonia, and RSV. Millions of people worldwide die from the flu, according to the CDC. And the World Health Organization reported lower respiratory infections as the fourth-leading cause of death worldwide before COVID came along.