User login

A veteran who is suicidal while sleeping

CASE Suicidal while asleep

Mr. R, age 28, an Iraq and Afghanistan veteran with major depressive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), is awoken by his wife to check on their daughter approximately 30 minutes after he takes his nightly regimen of zolpidem, 10 mg, melatonin, 6 mg, and hydroxyzine, 20 mg. When Mr. R returns to the bedroom, he appears to be confused. Mr. R grabs an unloaded gun from under the mattress, puts it in his mouth, and pulls the trigger. Then Mr. R holds the gun to his head and pulls the trigger while saying that his wife and children will be better off without him. His wife takes the gun away, but he grabs another gun from his gun box and loads it. His wife convinces him to remove the ammunition; however, Mr. R gets the other unloaded gun and pulls the trigger on himself again. After his wife takes this gun away, he tries cutting himself with a pocketknife, causing superficial cuts. Eventually, Mr. R goes back to bed. He does not remember these events in the morning.

What increased the likelihood of parasomnia in Mr. R?

a) high zolpidem dosage

b) concomitant use of other sedating agents

c) sleep deprivation

d) dehydration

[polldaddy:9712545]

The authors’ observations

Parasomnias are sleep-wake transition disorders classified by the sleep stage from which they arise, either NREM or rapid eye movement (REM). NREM parasomnias could result from incomplete awakening from NREM sleep, typically in Stage N3 (slow-wave) sleep.1 DSM-5 describes NREM parasomnias as arousal disorders in which the disturbance is not attributable to the physiological effects of substance; substance/medication-induced sleep disorder, parasomnia type, is when the disturbance can be attributed to a substance.2 The latter also can occur during REM sleep.

NREM parasomnias are characterized by abnormal behaviors during sleep with significant harm potential.3 Somnambulism or sleepwalking and sleep terrors are the 2 types of NREM parasomnias in DSM-5. Sleepwalking could involve complex behaviors, including:

- eating

- talking

- cooking

- shopping

- driving

- sexual activity.

Zolpidem, a benzodiazepine receptor agonist, is a preferred hypnotic agent for insomnia because of its low risk for abuse and daytime sedation.4 However, the drug has been associated with NREM parasomnias, namely somnambulism or sleepwalking, and its variants including sleep-driving, sleep-related eating disorder, and rarely sexsomnia (sleep-sex), with anterograde amnesia for the event.5 Suicidal behavior that occurs while the patient is asleep with next-day amnesia is another variant of somnambulism. There are several reports of suicidal behavior during sleep,6,7 but to our knowledge, there are only 2 previous cases implicating zolpidem as the cause:

- Gibson et al8 described a 49-year-old man who sustained a self-inflicted gunshot wound to his head while asleep. He just had started taking zolpidem, and in the weeks before the incident he had several episodes of sleepwalking and sleep-eating. He had consumed alcohol the night of the self-inflicted gunshot wound, but had no other psychiatric history.

- Chopra et al4 described a 37-year-old man, with no prior episodes of sleepwalking or associated complex behaviors, who was taking zolpidem, 10 mg/d, for chronic insomnia. He shot a gun in the basement of his home, and then held the loaded gun to his neck while asleep. The authors attributed the event to zolpidem in combination with other predisposing factors, including dehydration after intense exercise and alcohol use. The authors categorized this type of event as “para-suicidal amnestic behavior,” although “sleep-related pseudo-suicidal behavior” might be a better term for this type of parasomnia because of its occurrence during sleep and non-deliberate nature.

In another case report, a 27-year-old man took additional zolpidem after he did not experience desired sedative effects from an initial 20 mg.9 Because the patient remembered the suicidal thoughts, the authors believed that the patient attempted suicide while under the influence of zolpidem. The authors did not believe the incident to be sleep-related suicidal behavior, because it was uncertain if he attempted suicide while asleep.

Mr. R does not remember the events his wife witnessed while he was asleep. To our knowledge, Mr. R’s case is the first sleep-related pseudo-suicidal behavior case resulting from zolpidem, 10 mg/d, without concurrent alcohol use in an adult male veteran with PTSD and no suicidal ideation while awake.

HISTORY Further details revealed

Mr. R says that in the days leading to the incident he was not sleep-deprived and was getting at least 6 hours of restful sleep every night. He had been taking zolpidem every night. He has no childhood or family history of NREM parasomnias. He says he did not engage in intense exercise that evening or have a fever the night of the incident and has abstained from alcohol for 2 years.

His wife says that after he took zolpidem, when he was woken up, “He was not there; his eyes were glazed and glossy, and it’s like he was in another world,” and his speech and behavior were bizarre. She also reports that his eyes were open when he engaged in this behavior that appeared suicidal.

Three months before the incident, Mr. R had reported nightmares with dream enactment behaviors, hypervigilance on awakening and during the daytime, irritability, and anxious and depressed mood with neurovegetative symptoms, and was referred to our clinic for medication management. He also reported no prior or current manic or psychotic symptoms, denied suicidal thoughts, and had no history of suicide attempts. Mr. R’s medication regimen included tramadol, 400 mg/d, for chronic knee pain; fluoxetine, 60 mg/d, for depression and PTSD; and propranolol ER, 60 mg/d, and propranolol, 10 mg/d as needed, for anxiety. He was started on prazosin, 2 mg/d, titrated to 4 mg/d, for medication management of nightmares.

Mr. R also was referred to the sleep laboratory for a polysomnogram (PSG) because of reported loud snoring and witnessed apneas, especially because sleep apnea can cause nightmares and dream enactment behaviors. The PSG was negative for sleep apnea or excessive periodic limb movements of sleep, but showed increased electromyographic (EMG) activity during REM sleep, which was consistent with his report of dream enactment behaviors. Two months later, he reported improvement in nightmares and depression, but not in dream enactment behaviors. Because of prominent anxiety and irritability, he was started on gabapentin, 300 mg, 3 times a day.

What factor increases the risk of NREM parasomnias with zolpidem compared with benzodiazepines?

a) greater preservation of Stage N3 sleep

b) lesser degree of muscle relaxation

c) both a and b

d) none of the above

[polldaddy:9712556]

The authors’ observations

Factors that increase the likelihood of parasomnias include:

- zolpidem >10 mg at bedtime

- concomitant use of other CNS depressants, including sedative hypnotic agents and alcohol

- female sex

- not falling asleep immediately after taking zolpidem

- personal or family history of parasomnias

- living alone

- poor pill management

- presence of sleep disruptors such as sleep apnea and periodic limb movements of sleep.1,4,5,10

Higher dosages of zolpidem (>10 mg/d) have been identified as the predictive risk factor.5 In the Chopra et al4 case report on sleep-related suicidal behavior related to zolpidem, 10 mg at bedtime, concomitant dehydration and alcohol use were implicated as facilitating factors. Dehydration could increase serum levels of zolpidem resulting in greater CNS effects. Alcohol use was implicated in the Gibson et al8 case report as well, and the patient had multiple episodes of sleepwalking and sleep-related eating.However, Mr. R was not dehydrated or using alcohol.

An interesting feature of Mr. R’s case is that he was taking fluoxetine. Cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 is involved in metabolizing zolpidem, and norfluoxetine, a metabolite of fluoxetine, inhibits CYP3A4. Although studies have not found pharmacokinetic interactions between fluoxetine and zolpidem, these studies did not investigate fluoxetine dosages >20 mg/d.11 The inhibition of CYP enzymes by fluoxetine likely is dose-dependent,12 and therefore concomitant administration of high-dosage fluoxetine (>20 mg/d) with zolpidem might result in higher serum levels of zolpidem.

Mr. R also was taking several sedating agents (gabapentin, hydroxyzine, melatonin, and tramadol). The concomitant use of these sedative-hypnotic agents could have increased his risk of parasomnia. A review of the literature did not reveal any reports of gabapentin, hydroxyzine, melatonin, or tramadol causing parasomnias. This observation, as well as the well-known role of zolpidem5 in etiopathogenesis of parasomnias, indicates that the pseudo-suicidal behavior Mr. R displayed while asleep likely was a direct result of zolpidem use in presence of other facilitating factors. Gabapentin, which is known to increase the depth of sleep, was added to his regimen 1 month before his parasomnia episode. Therefore, gabapentin could have triggered parasomnia with zolpidem therapy.1,13

Conditions that provoke repeated cortical arousals (eg, periodic limb movement disorder [PLMD] and sleep apnea) or increase depth or pressure of sleep (intense exercise in the evening, fever, sleep deprivation) are thought to be associated with NREM parasomnias.1-4 However, Mr. R underwent in-laboratory PSG and tested negative for major cortical arousal-inducing conditions, such as PLMD and sleep apnea.

Some other sleep disruptors likely were involved in Mr. R’s case. Auditory and tactile stimuli are known to cause cortical arousals, with additive effect seen when these 2 stimuli are combined.3,14 Additionally, these exogenous stimuli are known to trigger sleep-related violent parasomnias.15 Mr. R displayed this behavior after his wife woke him up. The auditory stimulus of his wife’s voice and/or tactile stimulus involved in the act of waking Mr. R likely played a role in the suicidal and violent nature of his NREM parasomnia.

[polldaddy:9712581]

The authors’ observations

In general, the mechanisms by which zolpidem causes NREM parasomnias are not completely understood. The sedation-related amnestic properties of zolpidem might explain some of these behaviors. Patients could perform these behaviors after waking and have subsequent amnesia.4 There is greater preservation of Stage N3 sleep with zolpidem compared with benzodiazepines. Benzodiazepines also cause muscle relaxation while the motor system remains relatively more active during sleep with zolpidem because of its selectivity for α-1 subunit of gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptor. These factors might increase the likelihood of NREM parasomnias with zolpidem compared with benzodiazepines.4

Types of parasomnias

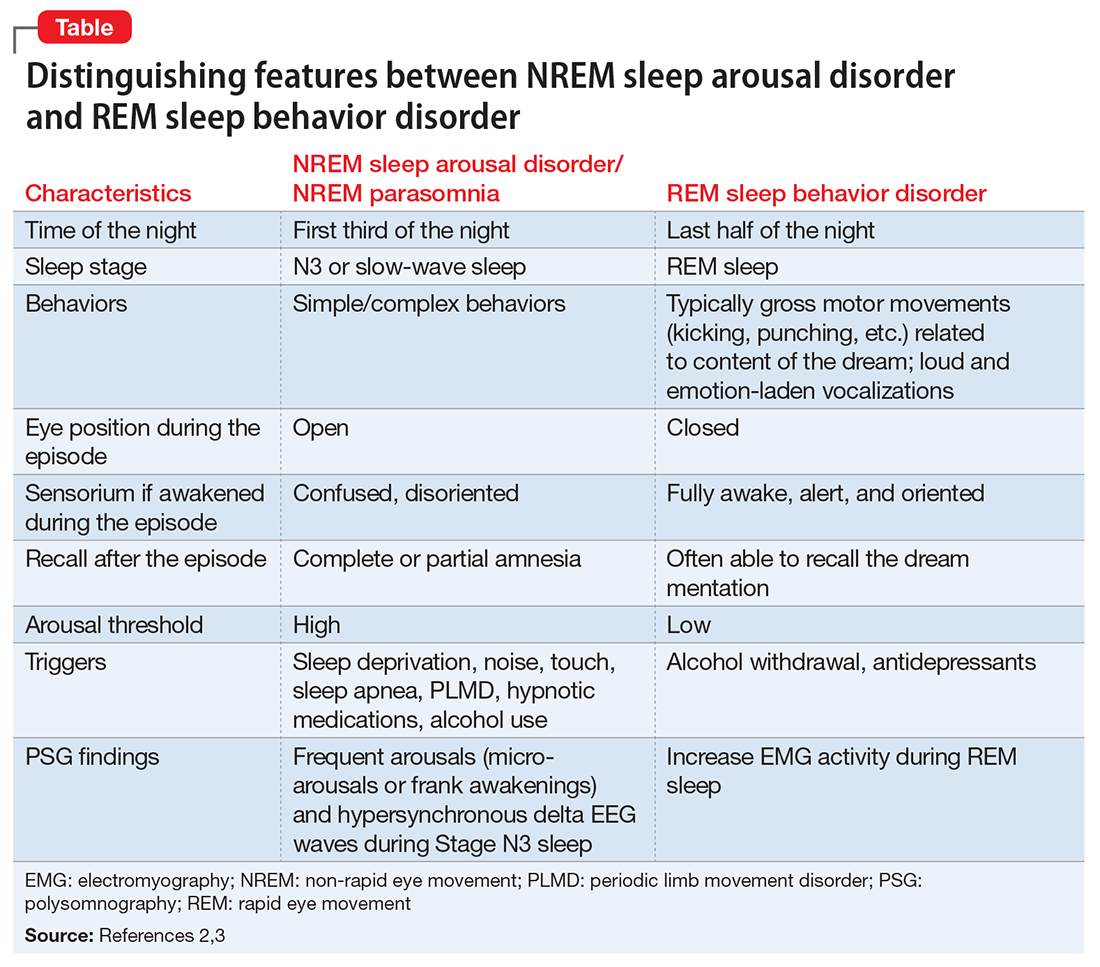

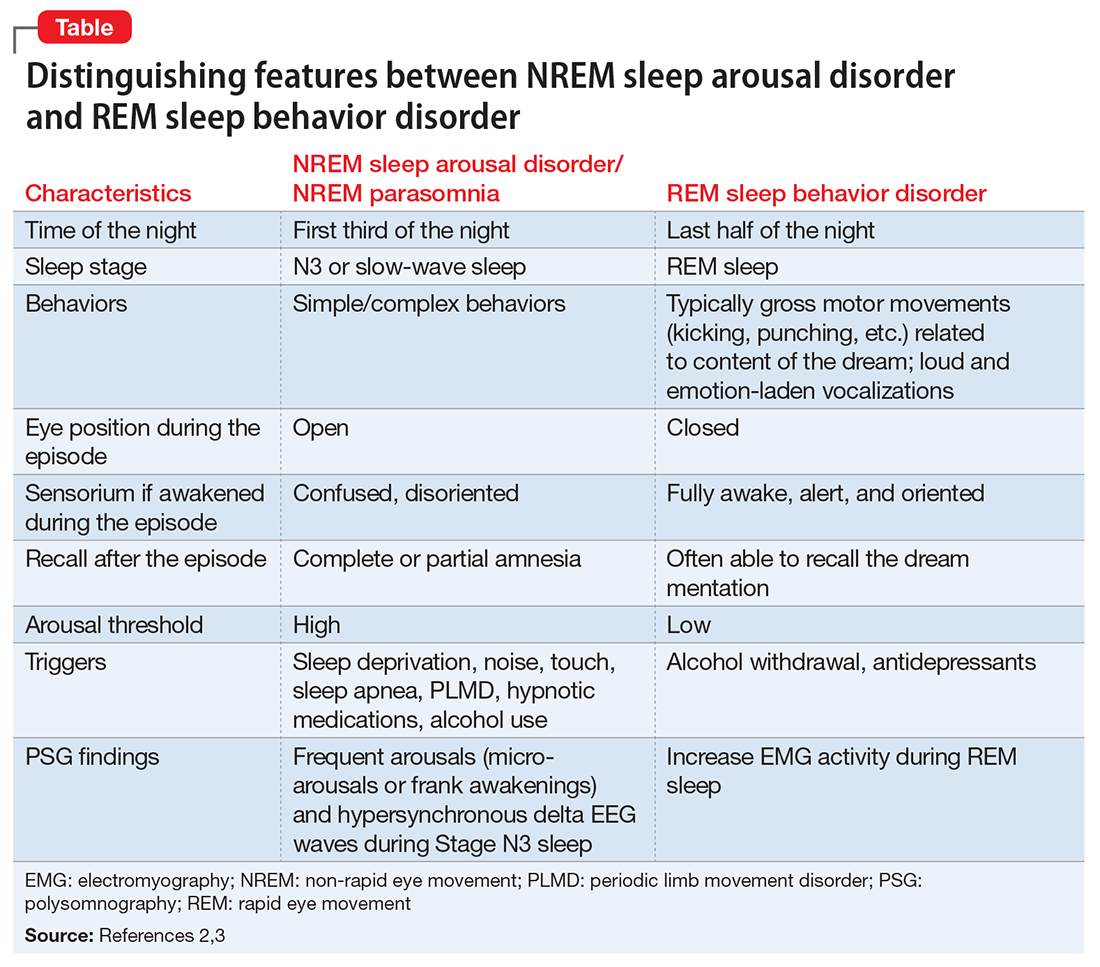

According to DSM-5, there are 2 categories of parasomnias based on the sleep stage from which a parasomnia emerges.2 REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD) refers to complex motor and/or vocalizations during REM sleep, accompanied by increased EMG activity during REM sleep (Table).2,3

The pseudo-suicidal behavior Mr. R displayed likely was NREM parasomnia because it occurred in the first third of the night with his eyes open and impaired recall after the event. Interestingly, Mr. R had RBD in addition to the NREM parasomnia likely caused by zolpidem. This is evident from Mr. R’s frequent dream enactment behaviors, such as kicking, thrashing, and punching during sleep, along with increased EMG activity during REM sleep as recorded on the PSG.10 The presence of RBD could be explained by selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (fluoxetine) use, and comorbidity with PTSD.2,16

Management of parasomnias

Initial management of parasomnias involves decreasing the risk of parasomnia-related injury. Suggested safety measures include:

- sleeping away from windows

- sleeping in a sleeping bag

- sleeping on a lower floor

- locking windows and doors

- removing potentially dangerous objects from the bedroom

- putting gates across stairwells

- installing bells or alarms on door knobs.15

Removing access to firearms or other weapons such as knives is of utmost importance especially with patients who have easy access during wakefulness. If removing weapons is not feasible, consider disarming, securing, or locking them.15 These considerations are relevant to veterans with PTSD because of the high prevalence of symptoms, including depression, insomnia, and pain, which require sedating medications.17 A review of parasomnias among a large sample of psychiatric outpatients revealed that a variety of sedating medications, including antidepressants, can lead to NREM parasomnias.18 Therefore, exercise caution when prescribing sedating medications, especially in patients vulnerable to developing dangerous parasomnias, such as a veteran with PTSD and easy access to guns.19

TREATMENT Zolpidem stopped

Mr. R immediately stops taking zolpidem because he is aware of its association with abnormal behaviors during sleep, and his wife removes his access to firearms and knives at night. Because of his history of clinical benefit and no history of parasomnias with mirtazapine, Mr. R is started on mirtazapine for insomnia that previously was treated with zolpidem, and residual depression. Six months after discontinuing zolpidem, he does not experience NREM parasomnias, and there are no changes in his dream enactment behaviors.

Summing up

Zolpidem therapy could be associated with unusual variants of NREM parasomnia, sleepwalking type; sleep-related pseudo-suicidal behavior is one such variant. Several factors could play a role in increasing the likelihood of NREM parasomnia with zolpidem therapy. In Mr. R’s case, the pharmacokinetic drug interactions between fluoxetine and zolpidem, as well as concomitant use of several sedating agents could have played a role in increasing the likelihood of NREM parasomnia, with audio-tactile stimuli contributing to the violent and suicidal nature of the parasomnia. Exercise caution when using CYP enzyme inhibitors, such as fluoxetine and paroxetine, in combination with zolpidem. Knowledge of the potential interaction between zolpidem and fluoxetine is important because antidepressants and hypnotics are commonly co-prescribed because insomnia often is comorbid with other psychiatric disorders.

In veterans with PTSD who do not have suicidal ideations while awake, life-threatening non-intentional behavior is a risk because of easy access to guns or other weapons. Sedative-hypnotic medications commonly are prescribed to patients with PTSD. Exercise caution when using hypnotic agents such as zolpidem, and consider sleep aids with a lower risk of parasomnias (based on the author’s experience, trazodone, mirtazapine, melatonin, and gabapentin) when possible. Non-pharmacologic treatments of insomnia, such as sleep hygiene education and, more importantly, cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia, are preferred. If a patient is already taking zolpidem, nightly dosage should not be >10 mg. Polypharmacy with other sedating medications should be avoided when possible and both exogenous (noise, pets) and endogenous sleep disruptors (sleep apnea, PLMD) should be addressed. Advise the patient to avoid alcohol and remove firearms and other potential weapons. Discontinue zolpidem if the patient develops sleep-related abnormal behavior because of its potential to take on violent forms.

1. Howell MJ. Parasomnias: an updated review. Neurotherapeutics. 2012;9(4):753-775.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

3. Zadra A, Desautels A, Petit D, et al. Somnambulism: clinical aspects and pathophysiological hypotheses. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(3):285-294.

4. Chopra A, Selim B, Silber MH, et al. Para-suicidal amnestic behavior associated with chronic zolpidem use: implications for patient safety. Psychosomatics. 2013;54(5):498-501.

5. Hwang TJ, Ni HC, Chen HC, et al. Risk predictors for hypnosedative-related complex sleep behaviors: a retrospective, cross-sectional pilot study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(10):1331-1335.

6. Shatkin JP, Feinfield K, Strober M. The misinterpretation of a non-REM sleep parasomnia as suicidal behavior in an adolescent. Sleep Breath. 2002;6(4):175-179.

7. Mahowald MW, Schenck CH, Goldner M, et al. Parasomnia pseudo-suicide. J Forensic Sci. 2003;48(5):1158-1162.

8. Gibson CE, Caplan JP. Zolpidem-associated parasomnia with serious self-injury: a shot in the dark. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(1):88-91.

9. Mortaz Hejri S, Faizi M, Babaeian M. Zolpidem-induced suicide attempt: a case report. Daru. 2013;20;21(1):77.

10. Poceta JS. Zolpidem ingestion, automatisms, and sleep driving: a clinical and legal case series. J Clin Sleep Med. 2011;7(6):632-638.

11. Hesse LM, von Moltke LL, Greenblatt DJ. Clinically important drug interactions with zopiclone, zolpidem and zaleplon. CNS Drugs. 2003;17(7):513-532.

12. Catterson ML, Preskorn SH. Pharmacokinetics of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: clinical relevance. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1996;78(4):203-208.

13. Rosenberg RP, Hull SG, Lankford DA, et al. A randomized, double-blind, single-dose, placebo-controlled, multicenter, polysomnographic study of gabapentin in transient insomnia induced by sleep phase advance. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;10(10):1093-1100.

14. Kato T, Montplaisir JY, Lavigne GJ. Experimentally induced arousals during sleep: a cross-modality matching paradigm. J Sleep Res. 2004;13(3):229-238.

15. Siclari F, Khatami R, Urbaniok F, et al. Violence in sleep. Brain. 2010;133(pt 12):3494-3509.

16. Husain AM, Miller PP, Carwile ST. Rem sleep behavior disorder: potential relationship to post-traumatic stress disorder. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;18(2):148-157.

17. Bernardy NC, Lund BC, Alexander B, et al. Increased polysedative use in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Pain Med. 2014;15(7):1083-1090.

18. Lam SP, Fong SY, Ho CK, et al. Parasomnia among psychiatric outpatients: a clinical, epidemiologic, cross-sectional study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(9):1374-1382.

19. Freeman TW, Roca V, Kimbrell T. A survey of gun collection and use among three groups of veteran patients admitted to veterans affairs hospital treatment programs. South Med J. 2003;96(3):240-243.

CASE Suicidal while asleep

Mr. R, age 28, an Iraq and Afghanistan veteran with major depressive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), is awoken by his wife to check on their daughter approximately 30 minutes after he takes his nightly regimen of zolpidem, 10 mg, melatonin, 6 mg, and hydroxyzine, 20 mg. When Mr. R returns to the bedroom, he appears to be confused. Mr. R grabs an unloaded gun from under the mattress, puts it in his mouth, and pulls the trigger. Then Mr. R holds the gun to his head and pulls the trigger while saying that his wife and children will be better off without him. His wife takes the gun away, but he grabs another gun from his gun box and loads it. His wife convinces him to remove the ammunition; however, Mr. R gets the other unloaded gun and pulls the trigger on himself again. After his wife takes this gun away, he tries cutting himself with a pocketknife, causing superficial cuts. Eventually, Mr. R goes back to bed. He does not remember these events in the morning.

What increased the likelihood of parasomnia in Mr. R?

a) high zolpidem dosage

b) concomitant use of other sedating agents

c) sleep deprivation

d) dehydration

[polldaddy:9712545]

The authors’ observations

Parasomnias are sleep-wake transition disorders classified by the sleep stage from which they arise, either NREM or rapid eye movement (REM). NREM parasomnias could result from incomplete awakening from NREM sleep, typically in Stage N3 (slow-wave) sleep.1 DSM-5 describes NREM parasomnias as arousal disorders in which the disturbance is not attributable to the physiological effects of substance; substance/medication-induced sleep disorder, parasomnia type, is when the disturbance can be attributed to a substance.2 The latter also can occur during REM sleep.

NREM parasomnias are characterized by abnormal behaviors during sleep with significant harm potential.3 Somnambulism or sleepwalking and sleep terrors are the 2 types of NREM parasomnias in DSM-5. Sleepwalking could involve complex behaviors, including:

- eating

- talking

- cooking

- shopping

- driving

- sexual activity.

Zolpidem, a benzodiazepine receptor agonist, is a preferred hypnotic agent for insomnia because of its low risk for abuse and daytime sedation.4 However, the drug has been associated with NREM parasomnias, namely somnambulism or sleepwalking, and its variants including sleep-driving, sleep-related eating disorder, and rarely sexsomnia (sleep-sex), with anterograde amnesia for the event.5 Suicidal behavior that occurs while the patient is asleep with next-day amnesia is another variant of somnambulism. There are several reports of suicidal behavior during sleep,6,7 but to our knowledge, there are only 2 previous cases implicating zolpidem as the cause:

- Gibson et al8 described a 49-year-old man who sustained a self-inflicted gunshot wound to his head while asleep. He just had started taking zolpidem, and in the weeks before the incident he had several episodes of sleepwalking and sleep-eating. He had consumed alcohol the night of the self-inflicted gunshot wound, but had no other psychiatric history.

- Chopra et al4 described a 37-year-old man, with no prior episodes of sleepwalking or associated complex behaviors, who was taking zolpidem, 10 mg/d, for chronic insomnia. He shot a gun in the basement of his home, and then held the loaded gun to his neck while asleep. The authors attributed the event to zolpidem in combination with other predisposing factors, including dehydration after intense exercise and alcohol use. The authors categorized this type of event as “para-suicidal amnestic behavior,” although “sleep-related pseudo-suicidal behavior” might be a better term for this type of parasomnia because of its occurrence during sleep and non-deliberate nature.

In another case report, a 27-year-old man took additional zolpidem after he did not experience desired sedative effects from an initial 20 mg.9 Because the patient remembered the suicidal thoughts, the authors believed that the patient attempted suicide while under the influence of zolpidem. The authors did not believe the incident to be sleep-related suicidal behavior, because it was uncertain if he attempted suicide while asleep.

Mr. R does not remember the events his wife witnessed while he was asleep. To our knowledge, Mr. R’s case is the first sleep-related pseudo-suicidal behavior case resulting from zolpidem, 10 mg/d, without concurrent alcohol use in an adult male veteran with PTSD and no suicidal ideation while awake.

HISTORY Further details revealed

Mr. R says that in the days leading to the incident he was not sleep-deprived and was getting at least 6 hours of restful sleep every night. He had been taking zolpidem every night. He has no childhood or family history of NREM parasomnias. He says he did not engage in intense exercise that evening or have a fever the night of the incident and has abstained from alcohol for 2 years.

His wife says that after he took zolpidem, when he was woken up, “He was not there; his eyes were glazed and glossy, and it’s like he was in another world,” and his speech and behavior were bizarre. She also reports that his eyes were open when he engaged in this behavior that appeared suicidal.

Three months before the incident, Mr. R had reported nightmares with dream enactment behaviors, hypervigilance on awakening and during the daytime, irritability, and anxious and depressed mood with neurovegetative symptoms, and was referred to our clinic for medication management. He also reported no prior or current manic or psychotic symptoms, denied suicidal thoughts, and had no history of suicide attempts. Mr. R’s medication regimen included tramadol, 400 mg/d, for chronic knee pain; fluoxetine, 60 mg/d, for depression and PTSD; and propranolol ER, 60 mg/d, and propranolol, 10 mg/d as needed, for anxiety. He was started on prazosin, 2 mg/d, titrated to 4 mg/d, for medication management of nightmares.

Mr. R also was referred to the sleep laboratory for a polysomnogram (PSG) because of reported loud snoring and witnessed apneas, especially because sleep apnea can cause nightmares and dream enactment behaviors. The PSG was negative for sleep apnea or excessive periodic limb movements of sleep, but showed increased electromyographic (EMG) activity during REM sleep, which was consistent with his report of dream enactment behaviors. Two months later, he reported improvement in nightmares and depression, but not in dream enactment behaviors. Because of prominent anxiety and irritability, he was started on gabapentin, 300 mg, 3 times a day.

What factor increases the risk of NREM parasomnias with zolpidem compared with benzodiazepines?

a) greater preservation of Stage N3 sleep

b) lesser degree of muscle relaxation

c) both a and b

d) none of the above

[polldaddy:9712556]

The authors’ observations

Factors that increase the likelihood of parasomnias include:

- zolpidem >10 mg at bedtime

- concomitant use of other CNS depressants, including sedative hypnotic agents and alcohol

- female sex

- not falling asleep immediately after taking zolpidem

- personal or family history of parasomnias

- living alone

- poor pill management

- presence of sleep disruptors such as sleep apnea and periodic limb movements of sleep.1,4,5,10

Higher dosages of zolpidem (>10 mg/d) have been identified as the predictive risk factor.5 In the Chopra et al4 case report on sleep-related suicidal behavior related to zolpidem, 10 mg at bedtime, concomitant dehydration and alcohol use were implicated as facilitating factors. Dehydration could increase serum levels of zolpidem resulting in greater CNS effects. Alcohol use was implicated in the Gibson et al8 case report as well, and the patient had multiple episodes of sleepwalking and sleep-related eating.However, Mr. R was not dehydrated or using alcohol.

An interesting feature of Mr. R’s case is that he was taking fluoxetine. Cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 is involved in metabolizing zolpidem, and norfluoxetine, a metabolite of fluoxetine, inhibits CYP3A4. Although studies have not found pharmacokinetic interactions between fluoxetine and zolpidem, these studies did not investigate fluoxetine dosages >20 mg/d.11 The inhibition of CYP enzymes by fluoxetine likely is dose-dependent,12 and therefore concomitant administration of high-dosage fluoxetine (>20 mg/d) with zolpidem might result in higher serum levels of zolpidem.

Mr. R also was taking several sedating agents (gabapentin, hydroxyzine, melatonin, and tramadol). The concomitant use of these sedative-hypnotic agents could have increased his risk of parasomnia. A review of the literature did not reveal any reports of gabapentin, hydroxyzine, melatonin, or tramadol causing parasomnias. This observation, as well as the well-known role of zolpidem5 in etiopathogenesis of parasomnias, indicates that the pseudo-suicidal behavior Mr. R displayed while asleep likely was a direct result of zolpidem use in presence of other facilitating factors. Gabapentin, which is known to increase the depth of sleep, was added to his regimen 1 month before his parasomnia episode. Therefore, gabapentin could have triggered parasomnia with zolpidem therapy.1,13

Conditions that provoke repeated cortical arousals (eg, periodic limb movement disorder [PLMD] and sleep apnea) or increase depth or pressure of sleep (intense exercise in the evening, fever, sleep deprivation) are thought to be associated with NREM parasomnias.1-4 However, Mr. R underwent in-laboratory PSG and tested negative for major cortical arousal-inducing conditions, such as PLMD and sleep apnea.

Some other sleep disruptors likely were involved in Mr. R’s case. Auditory and tactile stimuli are known to cause cortical arousals, with additive effect seen when these 2 stimuli are combined.3,14 Additionally, these exogenous stimuli are known to trigger sleep-related violent parasomnias.15 Mr. R displayed this behavior after his wife woke him up. The auditory stimulus of his wife’s voice and/or tactile stimulus involved in the act of waking Mr. R likely played a role in the suicidal and violent nature of his NREM parasomnia.

[polldaddy:9712581]

The authors’ observations

In general, the mechanisms by which zolpidem causes NREM parasomnias are not completely understood. The sedation-related amnestic properties of zolpidem might explain some of these behaviors. Patients could perform these behaviors after waking and have subsequent amnesia.4 There is greater preservation of Stage N3 sleep with zolpidem compared with benzodiazepines. Benzodiazepines also cause muscle relaxation while the motor system remains relatively more active during sleep with zolpidem because of its selectivity for α-1 subunit of gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptor. These factors might increase the likelihood of NREM parasomnias with zolpidem compared with benzodiazepines.4

Types of parasomnias

According to DSM-5, there are 2 categories of parasomnias based on the sleep stage from which a parasomnia emerges.2 REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD) refers to complex motor and/or vocalizations during REM sleep, accompanied by increased EMG activity during REM sleep (Table).2,3

The pseudo-suicidal behavior Mr. R displayed likely was NREM parasomnia because it occurred in the first third of the night with his eyes open and impaired recall after the event. Interestingly, Mr. R had RBD in addition to the NREM parasomnia likely caused by zolpidem. This is evident from Mr. R’s frequent dream enactment behaviors, such as kicking, thrashing, and punching during sleep, along with increased EMG activity during REM sleep as recorded on the PSG.10 The presence of RBD could be explained by selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (fluoxetine) use, and comorbidity with PTSD.2,16

Management of parasomnias

Initial management of parasomnias involves decreasing the risk of parasomnia-related injury. Suggested safety measures include:

- sleeping away from windows

- sleeping in a sleeping bag

- sleeping on a lower floor

- locking windows and doors

- removing potentially dangerous objects from the bedroom

- putting gates across stairwells

- installing bells or alarms on door knobs.15

Removing access to firearms or other weapons such as knives is of utmost importance especially with patients who have easy access during wakefulness. If removing weapons is not feasible, consider disarming, securing, or locking them.15 These considerations are relevant to veterans with PTSD because of the high prevalence of symptoms, including depression, insomnia, and pain, which require sedating medications.17 A review of parasomnias among a large sample of psychiatric outpatients revealed that a variety of sedating medications, including antidepressants, can lead to NREM parasomnias.18 Therefore, exercise caution when prescribing sedating medications, especially in patients vulnerable to developing dangerous parasomnias, such as a veteran with PTSD and easy access to guns.19

TREATMENT Zolpidem stopped

Mr. R immediately stops taking zolpidem because he is aware of its association with abnormal behaviors during sleep, and his wife removes his access to firearms and knives at night. Because of his history of clinical benefit and no history of parasomnias with mirtazapine, Mr. R is started on mirtazapine for insomnia that previously was treated with zolpidem, and residual depression. Six months after discontinuing zolpidem, he does not experience NREM parasomnias, and there are no changes in his dream enactment behaviors.

Summing up

Zolpidem therapy could be associated with unusual variants of NREM parasomnia, sleepwalking type; sleep-related pseudo-suicidal behavior is one such variant. Several factors could play a role in increasing the likelihood of NREM parasomnia with zolpidem therapy. In Mr. R’s case, the pharmacokinetic drug interactions between fluoxetine and zolpidem, as well as concomitant use of several sedating agents could have played a role in increasing the likelihood of NREM parasomnia, with audio-tactile stimuli contributing to the violent and suicidal nature of the parasomnia. Exercise caution when using CYP enzyme inhibitors, such as fluoxetine and paroxetine, in combination with zolpidem. Knowledge of the potential interaction between zolpidem and fluoxetine is important because antidepressants and hypnotics are commonly co-prescribed because insomnia often is comorbid with other psychiatric disorders.

In veterans with PTSD who do not have suicidal ideations while awake, life-threatening non-intentional behavior is a risk because of easy access to guns or other weapons. Sedative-hypnotic medications commonly are prescribed to patients with PTSD. Exercise caution when using hypnotic agents such as zolpidem, and consider sleep aids with a lower risk of parasomnias (based on the author’s experience, trazodone, mirtazapine, melatonin, and gabapentin) when possible. Non-pharmacologic treatments of insomnia, such as sleep hygiene education and, more importantly, cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia, are preferred. If a patient is already taking zolpidem, nightly dosage should not be >10 mg. Polypharmacy with other sedating medications should be avoided when possible and both exogenous (noise, pets) and endogenous sleep disruptors (sleep apnea, PLMD) should be addressed. Advise the patient to avoid alcohol and remove firearms and other potential weapons. Discontinue zolpidem if the patient develops sleep-related abnormal behavior because of its potential to take on violent forms.

CASE Suicidal while asleep

Mr. R, age 28, an Iraq and Afghanistan veteran with major depressive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), is awoken by his wife to check on their daughter approximately 30 minutes after he takes his nightly regimen of zolpidem, 10 mg, melatonin, 6 mg, and hydroxyzine, 20 mg. When Mr. R returns to the bedroom, he appears to be confused. Mr. R grabs an unloaded gun from under the mattress, puts it in his mouth, and pulls the trigger. Then Mr. R holds the gun to his head and pulls the trigger while saying that his wife and children will be better off without him. His wife takes the gun away, but he grabs another gun from his gun box and loads it. His wife convinces him to remove the ammunition; however, Mr. R gets the other unloaded gun and pulls the trigger on himself again. After his wife takes this gun away, he tries cutting himself with a pocketknife, causing superficial cuts. Eventually, Mr. R goes back to bed. He does not remember these events in the morning.

What increased the likelihood of parasomnia in Mr. R?

a) high zolpidem dosage

b) concomitant use of other sedating agents

c) sleep deprivation

d) dehydration

[polldaddy:9712545]

The authors’ observations

Parasomnias are sleep-wake transition disorders classified by the sleep stage from which they arise, either NREM or rapid eye movement (REM). NREM parasomnias could result from incomplete awakening from NREM sleep, typically in Stage N3 (slow-wave) sleep.1 DSM-5 describes NREM parasomnias as arousal disorders in which the disturbance is not attributable to the physiological effects of substance; substance/medication-induced sleep disorder, parasomnia type, is when the disturbance can be attributed to a substance.2 The latter also can occur during REM sleep.

NREM parasomnias are characterized by abnormal behaviors during sleep with significant harm potential.3 Somnambulism or sleepwalking and sleep terrors are the 2 types of NREM parasomnias in DSM-5. Sleepwalking could involve complex behaviors, including:

- eating

- talking

- cooking

- shopping

- driving

- sexual activity.

Zolpidem, a benzodiazepine receptor agonist, is a preferred hypnotic agent for insomnia because of its low risk for abuse and daytime sedation.4 However, the drug has been associated with NREM parasomnias, namely somnambulism or sleepwalking, and its variants including sleep-driving, sleep-related eating disorder, and rarely sexsomnia (sleep-sex), with anterograde amnesia for the event.5 Suicidal behavior that occurs while the patient is asleep with next-day amnesia is another variant of somnambulism. There are several reports of suicidal behavior during sleep,6,7 but to our knowledge, there are only 2 previous cases implicating zolpidem as the cause:

- Gibson et al8 described a 49-year-old man who sustained a self-inflicted gunshot wound to his head while asleep. He just had started taking zolpidem, and in the weeks before the incident he had several episodes of sleepwalking and sleep-eating. He had consumed alcohol the night of the self-inflicted gunshot wound, but had no other psychiatric history.

- Chopra et al4 described a 37-year-old man, with no prior episodes of sleepwalking or associated complex behaviors, who was taking zolpidem, 10 mg/d, for chronic insomnia. He shot a gun in the basement of his home, and then held the loaded gun to his neck while asleep. The authors attributed the event to zolpidem in combination with other predisposing factors, including dehydration after intense exercise and alcohol use. The authors categorized this type of event as “para-suicidal amnestic behavior,” although “sleep-related pseudo-suicidal behavior” might be a better term for this type of parasomnia because of its occurrence during sleep and non-deliberate nature.

In another case report, a 27-year-old man took additional zolpidem after he did not experience desired sedative effects from an initial 20 mg.9 Because the patient remembered the suicidal thoughts, the authors believed that the patient attempted suicide while under the influence of zolpidem. The authors did not believe the incident to be sleep-related suicidal behavior, because it was uncertain if he attempted suicide while asleep.

Mr. R does not remember the events his wife witnessed while he was asleep. To our knowledge, Mr. R’s case is the first sleep-related pseudo-suicidal behavior case resulting from zolpidem, 10 mg/d, without concurrent alcohol use in an adult male veteran with PTSD and no suicidal ideation while awake.

HISTORY Further details revealed

Mr. R says that in the days leading to the incident he was not sleep-deprived and was getting at least 6 hours of restful sleep every night. He had been taking zolpidem every night. He has no childhood or family history of NREM parasomnias. He says he did not engage in intense exercise that evening or have a fever the night of the incident and has abstained from alcohol for 2 years.

His wife says that after he took zolpidem, when he was woken up, “He was not there; his eyes were glazed and glossy, and it’s like he was in another world,” and his speech and behavior were bizarre. She also reports that his eyes were open when he engaged in this behavior that appeared suicidal.

Three months before the incident, Mr. R had reported nightmares with dream enactment behaviors, hypervigilance on awakening and during the daytime, irritability, and anxious and depressed mood with neurovegetative symptoms, and was referred to our clinic for medication management. He also reported no prior or current manic or psychotic symptoms, denied suicidal thoughts, and had no history of suicide attempts. Mr. R’s medication regimen included tramadol, 400 mg/d, for chronic knee pain; fluoxetine, 60 mg/d, for depression and PTSD; and propranolol ER, 60 mg/d, and propranolol, 10 mg/d as needed, for anxiety. He was started on prazosin, 2 mg/d, titrated to 4 mg/d, for medication management of nightmares.

Mr. R also was referred to the sleep laboratory for a polysomnogram (PSG) because of reported loud snoring and witnessed apneas, especially because sleep apnea can cause nightmares and dream enactment behaviors. The PSG was negative for sleep apnea or excessive periodic limb movements of sleep, but showed increased electromyographic (EMG) activity during REM sleep, which was consistent with his report of dream enactment behaviors. Two months later, he reported improvement in nightmares and depression, but not in dream enactment behaviors. Because of prominent anxiety and irritability, he was started on gabapentin, 300 mg, 3 times a day.

What factor increases the risk of NREM parasomnias with zolpidem compared with benzodiazepines?

a) greater preservation of Stage N3 sleep

b) lesser degree of muscle relaxation

c) both a and b

d) none of the above

[polldaddy:9712556]

The authors’ observations

Factors that increase the likelihood of parasomnias include:

- zolpidem >10 mg at bedtime

- concomitant use of other CNS depressants, including sedative hypnotic agents and alcohol

- female sex

- not falling asleep immediately after taking zolpidem

- personal or family history of parasomnias

- living alone

- poor pill management

- presence of sleep disruptors such as sleep apnea and periodic limb movements of sleep.1,4,5,10

Higher dosages of zolpidem (>10 mg/d) have been identified as the predictive risk factor.5 In the Chopra et al4 case report on sleep-related suicidal behavior related to zolpidem, 10 mg at bedtime, concomitant dehydration and alcohol use were implicated as facilitating factors. Dehydration could increase serum levels of zolpidem resulting in greater CNS effects. Alcohol use was implicated in the Gibson et al8 case report as well, and the patient had multiple episodes of sleepwalking and sleep-related eating.However, Mr. R was not dehydrated or using alcohol.

An interesting feature of Mr. R’s case is that he was taking fluoxetine. Cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 is involved in metabolizing zolpidem, and norfluoxetine, a metabolite of fluoxetine, inhibits CYP3A4. Although studies have not found pharmacokinetic interactions between fluoxetine and zolpidem, these studies did not investigate fluoxetine dosages >20 mg/d.11 The inhibition of CYP enzymes by fluoxetine likely is dose-dependent,12 and therefore concomitant administration of high-dosage fluoxetine (>20 mg/d) with zolpidem might result in higher serum levels of zolpidem.

Mr. R also was taking several sedating agents (gabapentin, hydroxyzine, melatonin, and tramadol). The concomitant use of these sedative-hypnotic agents could have increased his risk of parasomnia. A review of the literature did not reveal any reports of gabapentin, hydroxyzine, melatonin, or tramadol causing parasomnias. This observation, as well as the well-known role of zolpidem5 in etiopathogenesis of parasomnias, indicates that the pseudo-suicidal behavior Mr. R displayed while asleep likely was a direct result of zolpidem use in presence of other facilitating factors. Gabapentin, which is known to increase the depth of sleep, was added to his regimen 1 month before his parasomnia episode. Therefore, gabapentin could have triggered parasomnia with zolpidem therapy.1,13

Conditions that provoke repeated cortical arousals (eg, periodic limb movement disorder [PLMD] and sleep apnea) or increase depth or pressure of sleep (intense exercise in the evening, fever, sleep deprivation) are thought to be associated with NREM parasomnias.1-4 However, Mr. R underwent in-laboratory PSG and tested negative for major cortical arousal-inducing conditions, such as PLMD and sleep apnea.

Some other sleep disruptors likely were involved in Mr. R’s case. Auditory and tactile stimuli are known to cause cortical arousals, with additive effect seen when these 2 stimuli are combined.3,14 Additionally, these exogenous stimuli are known to trigger sleep-related violent parasomnias.15 Mr. R displayed this behavior after his wife woke him up. The auditory stimulus of his wife’s voice and/or tactile stimulus involved in the act of waking Mr. R likely played a role in the suicidal and violent nature of his NREM parasomnia.

[polldaddy:9712581]

The authors’ observations

In general, the mechanisms by which zolpidem causes NREM parasomnias are not completely understood. The sedation-related amnestic properties of zolpidem might explain some of these behaviors. Patients could perform these behaviors after waking and have subsequent amnesia.4 There is greater preservation of Stage N3 sleep with zolpidem compared with benzodiazepines. Benzodiazepines also cause muscle relaxation while the motor system remains relatively more active during sleep with zolpidem because of its selectivity for α-1 subunit of gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptor. These factors might increase the likelihood of NREM parasomnias with zolpidem compared with benzodiazepines.4

Types of parasomnias

According to DSM-5, there are 2 categories of parasomnias based on the sleep stage from which a parasomnia emerges.2 REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD) refers to complex motor and/or vocalizations during REM sleep, accompanied by increased EMG activity during REM sleep (Table).2,3

The pseudo-suicidal behavior Mr. R displayed likely was NREM parasomnia because it occurred in the first third of the night with his eyes open and impaired recall after the event. Interestingly, Mr. R had RBD in addition to the NREM parasomnia likely caused by zolpidem. This is evident from Mr. R’s frequent dream enactment behaviors, such as kicking, thrashing, and punching during sleep, along with increased EMG activity during REM sleep as recorded on the PSG.10 The presence of RBD could be explained by selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (fluoxetine) use, and comorbidity with PTSD.2,16

Management of parasomnias

Initial management of parasomnias involves decreasing the risk of parasomnia-related injury. Suggested safety measures include:

- sleeping away from windows

- sleeping in a sleeping bag

- sleeping on a lower floor

- locking windows and doors

- removing potentially dangerous objects from the bedroom

- putting gates across stairwells

- installing bells or alarms on door knobs.15

Removing access to firearms or other weapons such as knives is of utmost importance especially with patients who have easy access during wakefulness. If removing weapons is not feasible, consider disarming, securing, or locking them.15 These considerations are relevant to veterans with PTSD because of the high prevalence of symptoms, including depression, insomnia, and pain, which require sedating medications.17 A review of parasomnias among a large sample of psychiatric outpatients revealed that a variety of sedating medications, including antidepressants, can lead to NREM parasomnias.18 Therefore, exercise caution when prescribing sedating medications, especially in patients vulnerable to developing dangerous parasomnias, such as a veteran with PTSD and easy access to guns.19

TREATMENT Zolpidem stopped

Mr. R immediately stops taking zolpidem because he is aware of its association with abnormal behaviors during sleep, and his wife removes his access to firearms and knives at night. Because of his history of clinical benefit and no history of parasomnias with mirtazapine, Mr. R is started on mirtazapine for insomnia that previously was treated with zolpidem, and residual depression. Six months after discontinuing zolpidem, he does not experience NREM parasomnias, and there are no changes in his dream enactment behaviors.

Summing up

Zolpidem therapy could be associated with unusual variants of NREM parasomnia, sleepwalking type; sleep-related pseudo-suicidal behavior is one such variant. Several factors could play a role in increasing the likelihood of NREM parasomnia with zolpidem therapy. In Mr. R’s case, the pharmacokinetic drug interactions between fluoxetine and zolpidem, as well as concomitant use of several sedating agents could have played a role in increasing the likelihood of NREM parasomnia, with audio-tactile stimuli contributing to the violent and suicidal nature of the parasomnia. Exercise caution when using CYP enzyme inhibitors, such as fluoxetine and paroxetine, in combination with zolpidem. Knowledge of the potential interaction between zolpidem and fluoxetine is important because antidepressants and hypnotics are commonly co-prescribed because insomnia often is comorbid with other psychiatric disorders.

In veterans with PTSD who do not have suicidal ideations while awake, life-threatening non-intentional behavior is a risk because of easy access to guns or other weapons. Sedative-hypnotic medications commonly are prescribed to patients with PTSD. Exercise caution when using hypnotic agents such as zolpidem, and consider sleep aids with a lower risk of parasomnias (based on the author’s experience, trazodone, mirtazapine, melatonin, and gabapentin) when possible. Non-pharmacologic treatments of insomnia, such as sleep hygiene education and, more importantly, cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia, are preferred. If a patient is already taking zolpidem, nightly dosage should not be >10 mg. Polypharmacy with other sedating medications should be avoided when possible and both exogenous (noise, pets) and endogenous sleep disruptors (sleep apnea, PLMD) should be addressed. Advise the patient to avoid alcohol and remove firearms and other potential weapons. Discontinue zolpidem if the patient develops sleep-related abnormal behavior because of its potential to take on violent forms.

1. Howell MJ. Parasomnias: an updated review. Neurotherapeutics. 2012;9(4):753-775.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

3. Zadra A, Desautels A, Petit D, et al. Somnambulism: clinical aspects and pathophysiological hypotheses. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(3):285-294.

4. Chopra A, Selim B, Silber MH, et al. Para-suicidal amnestic behavior associated with chronic zolpidem use: implications for patient safety. Psychosomatics. 2013;54(5):498-501.

5. Hwang TJ, Ni HC, Chen HC, et al. Risk predictors for hypnosedative-related complex sleep behaviors: a retrospective, cross-sectional pilot study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(10):1331-1335.

6. Shatkin JP, Feinfield K, Strober M. The misinterpretation of a non-REM sleep parasomnia as suicidal behavior in an adolescent. Sleep Breath. 2002;6(4):175-179.

7. Mahowald MW, Schenck CH, Goldner M, et al. Parasomnia pseudo-suicide. J Forensic Sci. 2003;48(5):1158-1162.

8. Gibson CE, Caplan JP. Zolpidem-associated parasomnia with serious self-injury: a shot in the dark. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(1):88-91.

9. Mortaz Hejri S, Faizi M, Babaeian M. Zolpidem-induced suicide attempt: a case report. Daru. 2013;20;21(1):77.

10. Poceta JS. Zolpidem ingestion, automatisms, and sleep driving: a clinical and legal case series. J Clin Sleep Med. 2011;7(6):632-638.

11. Hesse LM, von Moltke LL, Greenblatt DJ. Clinically important drug interactions with zopiclone, zolpidem and zaleplon. CNS Drugs. 2003;17(7):513-532.

12. Catterson ML, Preskorn SH. Pharmacokinetics of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: clinical relevance. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1996;78(4):203-208.

13. Rosenberg RP, Hull SG, Lankford DA, et al. A randomized, double-blind, single-dose, placebo-controlled, multicenter, polysomnographic study of gabapentin in transient insomnia induced by sleep phase advance. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;10(10):1093-1100.

14. Kato T, Montplaisir JY, Lavigne GJ. Experimentally induced arousals during sleep: a cross-modality matching paradigm. J Sleep Res. 2004;13(3):229-238.

15. Siclari F, Khatami R, Urbaniok F, et al. Violence in sleep. Brain. 2010;133(pt 12):3494-3509.

16. Husain AM, Miller PP, Carwile ST. Rem sleep behavior disorder: potential relationship to post-traumatic stress disorder. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;18(2):148-157.

17. Bernardy NC, Lund BC, Alexander B, et al. Increased polysedative use in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Pain Med. 2014;15(7):1083-1090.

18. Lam SP, Fong SY, Ho CK, et al. Parasomnia among psychiatric outpatients: a clinical, epidemiologic, cross-sectional study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(9):1374-1382.

19. Freeman TW, Roca V, Kimbrell T. A survey of gun collection and use among three groups of veteran patients admitted to veterans affairs hospital treatment programs. South Med J. 2003;96(3):240-243.

1. Howell MJ. Parasomnias: an updated review. Neurotherapeutics. 2012;9(4):753-775.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

3. Zadra A, Desautels A, Petit D, et al. Somnambulism: clinical aspects and pathophysiological hypotheses. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(3):285-294.

4. Chopra A, Selim B, Silber MH, et al. Para-suicidal amnestic behavior associated with chronic zolpidem use: implications for patient safety. Psychosomatics. 2013;54(5):498-501.

5. Hwang TJ, Ni HC, Chen HC, et al. Risk predictors for hypnosedative-related complex sleep behaviors: a retrospective, cross-sectional pilot study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(10):1331-1335.

6. Shatkin JP, Feinfield K, Strober M. The misinterpretation of a non-REM sleep parasomnia as suicidal behavior in an adolescent. Sleep Breath. 2002;6(4):175-179.

7. Mahowald MW, Schenck CH, Goldner M, et al. Parasomnia pseudo-suicide. J Forensic Sci. 2003;48(5):1158-1162.

8. Gibson CE, Caplan JP. Zolpidem-associated parasomnia with serious self-injury: a shot in the dark. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(1):88-91.

9. Mortaz Hejri S, Faizi M, Babaeian M. Zolpidem-induced suicide attempt: a case report. Daru. 2013;20;21(1):77.

10. Poceta JS. Zolpidem ingestion, automatisms, and sleep driving: a clinical and legal case series. J Clin Sleep Med. 2011;7(6):632-638.

11. Hesse LM, von Moltke LL, Greenblatt DJ. Clinically important drug interactions with zopiclone, zolpidem and zaleplon. CNS Drugs. 2003;17(7):513-532.

12. Catterson ML, Preskorn SH. Pharmacokinetics of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: clinical relevance. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1996;78(4):203-208.

13. Rosenberg RP, Hull SG, Lankford DA, et al. A randomized, double-blind, single-dose, placebo-controlled, multicenter, polysomnographic study of gabapentin in transient insomnia induced by sleep phase advance. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;10(10):1093-1100.

14. Kato T, Montplaisir JY, Lavigne GJ. Experimentally induced arousals during sleep: a cross-modality matching paradigm. J Sleep Res. 2004;13(3):229-238.

15. Siclari F, Khatami R, Urbaniok F, et al. Violence in sleep. Brain. 2010;133(pt 12):3494-3509.

16. Husain AM, Miller PP, Carwile ST. Rem sleep behavior disorder: potential relationship to post-traumatic stress disorder. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;18(2):148-157.

17. Bernardy NC, Lund BC, Alexander B, et al. Increased polysedative use in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Pain Med. 2014;15(7):1083-1090.

18. Lam SP, Fong SY, Ho CK, et al. Parasomnia among psychiatric outpatients: a clinical, epidemiologic, cross-sectional study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(9):1374-1382.

19. Freeman TW, Roca V, Kimbrell T. A survey of gun collection and use among three groups of veteran patients admitted to veterans affairs hospital treatment programs. South Med J. 2003;96(3):240-243.

A medication change, then involuntary lip smacking and tongue rolling

CASE Insurer denies drug coverage

Ms. X, age 65, has a 35-year history of bipolar I disorder (BD I) characterized by psychotic mania and severe suicidal depression. For the past year, her symptoms have been well controlled with aripiprazole, 5 mg/d; trazodone, 50 mg at bedtime; and citalopram, 20 mg/d. Because her health insurance has changed, Ms. X asks to be switched to an alternative antipsychotic because the new provider denied coverage of aripiprazole.

While taking aripiprazole, Ms. X did not report any extrapyramidal side effects, including tardive dyskinesia. Her Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) score is 4. No significant abnormal movements were noted on examination during previous medication management sessions.

We decide to replace aripiprazole with quetiapine, 50 mg/d. At a 2-week follow-up visit, Ms. X is noted to have euphoric mood and reduced need to sleep, flight of ideas, increased talkativeness, and paranoia. We also notice that she has significant tongue rolling and lip smacking, which she says started 10 days after changing from aripiprazole to quetiapine. Her AIMS score is 17.

What could be causing Ms. X’s tongue rolling and lip smacking?

a) an irreversible syndrome usually starting after 1 or 2 years of continuous exposure to antipsychotics

b) a self-limited condition expected to resolve completely within 12 weeks

c) an acute manifestation of an antipsychotic that can respond to an anticholinergic agent

d) none of the above

The authors’ observations

Tardive dyskinesia (TD) refers to at least moderate abnormal involuntary movements in ≥1 areas of the body or at least mild movements in ≥2 areas of the body, developing after ≥3 months of cumulative exposure (continuous or discontinuous) to dopamine D2 receptor-blocking agents.1 AIMS is a 14-item, clinician-administered questionnaire designed to evaluate such movements and track their severity over time. The first 10 items are rated on 5-point scale (0 = none; 1 = minimal; 2 = mild; 3 = moderate; 4 = severe), with items 1 to 4 assessing orofacial movements, 5 to 7 assessing extremity and truncal movements, and 8 to 10 assessing overall severity, impairment, and subjective distress. Items 11 to 13 assess dental status because lack of teeth can result in oral movements mimicking TDs. The last item assesses whether these movements disappear during sleep.

HISTORY Poor response

Ms. X was given a diagnosis of BD I at age 30; she first started taking antipsychotics 10 years later. Previous psychotropic trials included lamotrigine, divalproex sodium, risperidone, and ziprasidone, which were ineffective or poorly tolerated. Her medical history includes obstructive sleep apnea, narcolepsy, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, fibromyalgia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and hypothyroidism. She takes metformin, omeprazole, pravastatin, carvedilol, insulin, levothyroxine, methylphenidate (for hypersomnia), and enalapril.

What is the next best step in management?

a) discontinue quetiapine

b) replace quetiapine with clozapine

c) increase quetiapine to target manic symptoms and reassess in a few weeks

d) continue quetiapine and treat abnormal movements with benztropine

TREATMENT Increase dosage

We increase quetiapine to 150 mg/d to target Ms. X’s manic symptoms. She is scheduled for a follow-up visit in 4 weeks but is instructed to return to the clinic earlier if her manic symptoms do not improve. At the 4-week follow-up visit, Ms. X does not have any abnormal movements and her manic symptoms have resolved. Her AIMS score is 4. Her husband reports that her abnormal movements resolved 4 days after increasing quetiapine to 150 mg/d.

The authors’ observations

Second-generation antipsychotics are known to have a lower risk of extrapyramidal adverse reactions compared with older first-generation antipsychotics.2,3 TD differs from other extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) because of its delayed onset. Risk factors for TD include:

• female sex

• age >50

• history of brain damage

• long-term antipsychotic use

• diagnosis of a mood disorder.

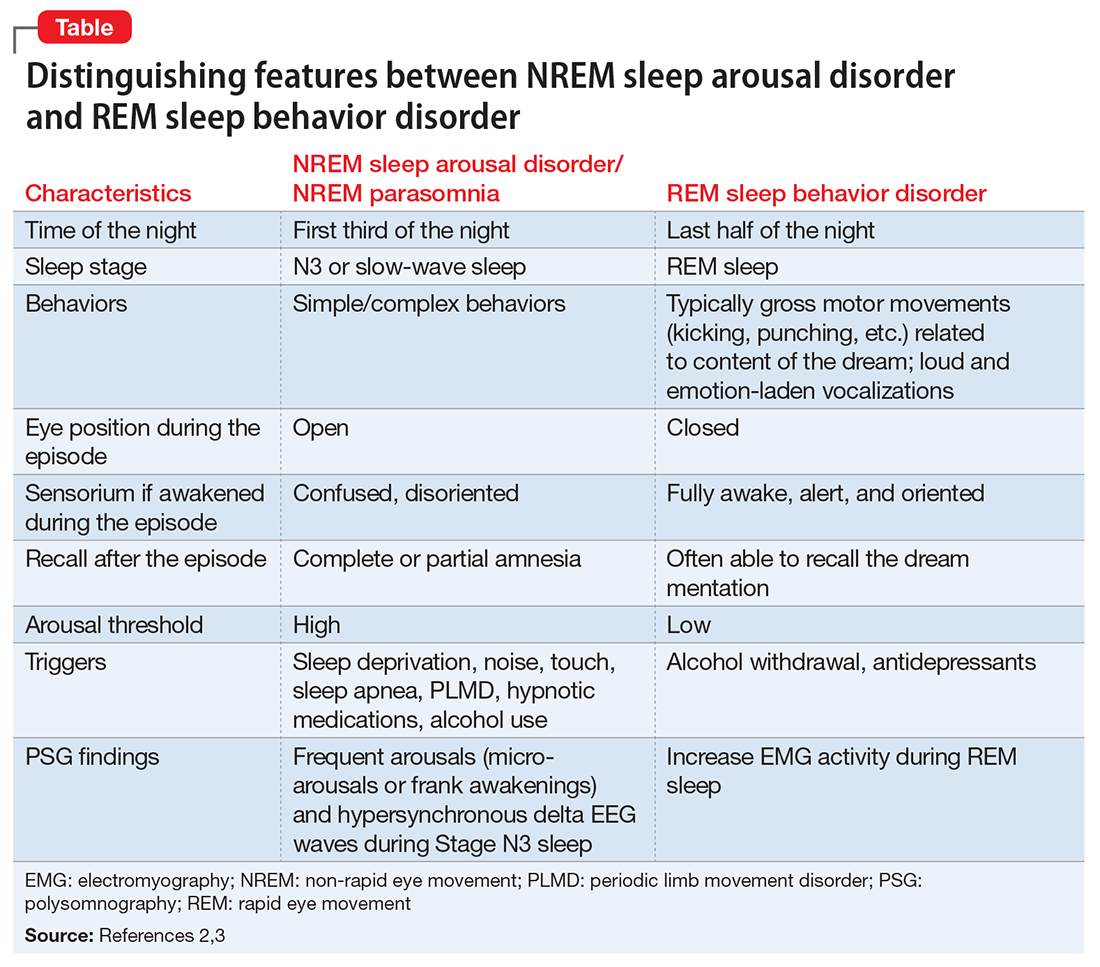

Gardos et al4 described 2 other forms of delayed dyskinesias related to antipsychotic use but resulting from antipsychotic discontinuation: withdrawal dyskinesia and covert dyskinesia. Evidence for these types of antipsychotic discontinuation syndromes mostly is anecdotal.5,6Table 1 highlights 3 different types of dyskinesias and their management.

Withdrawal dyskinesia has been described as a syndrome resembling TD that appears after discontinuation or dosage reduction of an antipsychotic in a patient who does not have an earlier TD diagnosis.7 The prevalence of withdrawal dyskinesia among patients undergoing antipsychotic discontinuation is approximately 30%.8 Cases of withdrawal dyskinesia are self-limited and resolve in 1 to 3 months.9,10 We believe that Ms. X’s movement disorder was withdrawal dyskinesia from aripiprazole because her symptoms started 10 days after the drug was discontinued, and was self-limited and reversible.

Similar to TD, withdrawal dyskinesia can present in different forms:

• tongue protrusion movements

• facial grimacing

• ticks

• chorea

• tremors

• athetosis

• involuntary vocalizations

• abnormal movements of hands and legs

• “dyspnea” due to involvement of respiratory musculature.5,11

There may be a sex difference in duration of withdrawal dyskinesias, because symptoms persist longer in females.9

Although covert dyskinesia also develops after discontinuation or dosage reduction of a dopamine-blocking agent, the symptoms usually are permanent, and could require reintroducing the antipsychotic or management with evidence-based treatments for TD, such as tetrabenazine or amantadine.6,12

What is the cause of Ms. X’s abnormal involuntary movements?

a) quetiapine-induced D2 receptor hypersensitivity

b) aripiprazole-induced cholinergic overactivity

c) quetiapine-induced cholinergic overactivity

d) aripiprazole-induced D2 receptor hypersensitivity

The authors’ observations

Pathophysiology of this condition is unknown but different theories have been proposed. D2 receptor up-regulation and hypersensitivity to compensate for chronic D2 receptor blockade by antipsychotics is a commonly cited theory.7,13 Discontinuation of an antipsychotic can make this D2 receptor up-regulation and hypersensitivity manifest as withdrawal dyskinesia by creating a temporary hyperdopaminergic state in basal ganglia. Other theories implicate decrease of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in the globus pallidus (GP) and substantia nigra (SN) regions of the brain, and oxidative damage to GABAergic interneurons in GP and SN from excess production of catecholamines in response to chronic dopamine blockade.14

It has been proposed that patients with withdrawal dyskinesia might be in an early phase of D2 receptor modulation that, if continued because of use of the antipsychotic implicated in withdrawal dyskinesia, can lead to development of TD.4,7,8 A feature of withdrawal dyskinesia that differentiates it from TD is that it usually remits spontaneously within several weeks to a few months.4,7 Because of this characteristic, Schultz et al8 propose that, if withdrawal dyskinesia is identified early in treatment, it may be possible to prevent development of persistent TD.

Look carefully for dyskinetic movements in patients who have recently discontinued or decreased the dosage of their antipsychotic. Non-compliance and partial compliance are common problems among patients taking an antipsychotic.15 Therefore, careful watchfulness for withdrawal dyskinesias at all times can be beneficial. Inquiring about recent history of these dyskinesias in such patients is probably more useful than an exam because the dyskinesias may not be evident on exam when these patients show up for their follow-up visit, because of their self-limited nature.8

Treatment options

If a patient is noted to have a withdrawal-emergent dyskinesia, a clinician has options to prevent TD, including:

• decreasing the dosage of the antipsychotic

• switching from a typical antipsychotic to an atypical antipsychotic

• switching from one atypical to another with lesser affinity for striatal D2 receptor, such as clozapine or quetiapine.16,17

In addition, researchers are investigating the use of vitamin B6, Ginkgo biloba, amantadine, levetiracetam, melatonin, tetrabenazine, zonisamide, branched chain amino acids, clonazepam, and vitamin E as treatment alternatives for TD.

Tetrabenazine acts by blocking vesicular monoamine transporter type 2, thereby inhibiting release of monoamines, including dopamine into synaptic cleft area in basal ganglia.18 Clonazepam’s benefit for TD relates to its facilitation of GABAergic neurotransmission, because reduced GABAergic transmission in GP and SN has been associ ated with hyperkinetic movements, including TD.14Ginkgo biloba and melatonin exert their beneficial effects in TD through their antioxidant function.14

The agents listed in Table 219 could be used on a short-term basis for symptomatic treatment of withdrawal dyskinesias.1,18,20

Withdrawal dyskinesia has been reported with aripiprazole discontinuation and is thought to be related to aripiprazole’s strong affinity for D2 receptors.21 Aripiprazole at dosages of 15 to 30 mg/d can occupy more than 80% of the striatal D2 dopamine receptors. The dosage of ≥30 mg/d can lead to receptor occupancy of >90%.22 Studies have shown that EPS correlate with D2 receptor occupancy in steady-state conditions, and occupancy exceeding 80% results in these symptoms.22

Compared with aripiprazole, quetiapine has weak affinity for D2 receptors (Table 3), making it an unlikely culprit if dyskinesia emerges within 2 weeks of initation.22 We believe that, in Ms. X’s case, quetiapine might have masked the severity of aripiprazole withdrawal dyskinesia by causing some degree of D2 receptor blockade. It may have decreased the duration of withdrawal dyskinesia by the same effect on D2 receptors. It may have lasted longer if aripiprazole was not replaced by another antipsychotic. This is particularly evident because dyskinesia improved quickly when quetiapine was titrated to 150 mg/d. The higher quetiapine dosage of 150 mg/d is closer to 5 mg/d of aripiprazole in terms of D2 receptor occupancy and affinity. However, quetiapine is weaker than aripiprazole in terms of D2 receptor occupancy at all dosages, and therefore less likely to cause EPS.16

Summing up

Withdrawal dyskinesia in the absence of a history of TD is a common symptom of antipsychotic discontinuation or dosage reduction after long-term use of an antipsychotic. It is more commonly seen with antipsychotics with high D2 receptor occupancy, and has been hypothesized to be related to D2 receptor supersensitivity to ambient dopamine, resulting as a compensatory response to chronic D2 blockade by this class of medication.

Evidence suggests that reversible withdrawal dyskinesia could represent a prodrome to irreversible TD. Therefore, keeping a watchful eye for these movements during the exam, along with specific inquiry about withdrawal dyskinesias while taking a history at every follow-up visit, is important because doing so can:

• inform the clinician about partial compliance or noncompliance to these medications, which could lead to treatment failure

• help prevent development of irreversible TD syndrome.

Ms. X’s case reminds clinicians (1) to be aware of this unexpected side effect occurring even with second-generation antipsychotics and (2) that they should consider EPS in patients while they are discontinuing their drugs. Furthermore, it is important for clinical and medicolegal reasons to inform our patients that different forms of dyskinesias can be potential side effects of antipsychotics.

Bottom Line

Dyskinesias can result from withdrawal of both typical and atypical antipsychotics, and usually are self-limited. Withdrawal dyskinesia may represent a prodrome to tardive dyskinesia; early recognition may aid in preventing development of persistent tardive dyskinesia.

Related Resources

• Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale. http://www.cqaimh.org/pdf/toolaims.pdf.

• Goldberg JF, Ernst CL. Managing the side effects of psychotropic medications. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2012.

• Tarsay D. Tardive dyskinesia: prevention and treatment. http:// www.uptodate.com/contents/tardive-dyskinesia-prevention-and-treatment?topicKey=NEURO%2F4908&elapsedTimeMs=3 &view=print&displayedView=full#.

Drug Brand Names

Amantadine • Symmetrel

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Benztropine • Cogentin

Carvedilol • Coreg

Citalopram • Celexa

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Clozapine • Clozaril

Divalproex sodium • Depakote

Donepezil • Aricept

Enalapril • Vasotec

Haloperidol • Haldol

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Levetiracetam • Keppra

Levothyroxine • Levoxyl, Synthroid

Metformin • Glucophage

Methylphenidate • Ritalin

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Omeprazole • Prilosec

Pravastatin • Pravachol

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Tetrabenazine • Xenazine

Trazodone • Desyrel, Oleptro

Ziprasidone • Geodon

Zonisamide • Zonegran

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Bhidayasiri R1, Fahn S, Weiner WJ, et al; American Academy of Neurology. Evidence-based guideline: treatment of tardive syndromes: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2013;81(5):463-469.

2. Dolder CR, Jeste DV. Incidence of tardive dyskinesia with typical versus atypical antipsychotics in very high risk patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53(12):1142-1145.

3. Correll CU, Leucht S, Kane JM. Lower risk for tardive dyskinesia associated with second-generation antipsychotics: a systematic review of 1-year studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(3):414-425.

4. Gardos G, Cole JO, Tarsy D. Withdrawal syndromes associated with antipsychotic drugs. Am J Psychiatry. 1978;135(11):1321-1324.

5. Salomon C, Hamilton B. Antipsychotic discontinuation syndromes: a narrative review of the evidence and its integration into Australian mental health nursing textbooks. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2014;23(1):69-78.

6. Moseley CN, Simpson-Khanna HA, Catalano G, et al. Covert dyskinesia associated with aripiprazole: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2013;36(4):128-130.

7. Anand VS, Dewan MJ. Withdrawal-emergent dyskinesia in a patient on risperidone undergoing dosage reduction. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 1996;8(3):179-182.

8. Schultz SK, Miller DD, Arndt S, et al. Withdrawal-emergent dyskinesia in patients with schizophrenia during antipsychotic discontinuation. Biol Psychiatry. 1995;38(11):713-719.

9. Degkwitz R, Bauer MP, Gruber M, et al. Time relationship between the appearance of persisting extrapyramidal hyperkineses and psychotic recurrences following sudden interruption of prolonged neuroleptic therapy of chronic schizophrenic patients [in German]. Arzneimittelforschung. 1970;20(7):890-893.

10. Sethi KD. Tardive dyskinesias. In: Adler CH, Ahlskog JE, eds. Parkinson’s disease and movement disorders: diagnosis and treatment guidelines for the practicing physician. New York, NY: Humana Press; 2000:331-338.

11. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

12. Horváth K, Aschermann Z, Komoly S, et al. Treatment of tardive syndromes [in Hungarian]. Psychiatr Hung. 2014;29(2):214-224.

13. Samaha AN, Seeman P, Stewart J, et al. “Breakthrough” dopamine supersensitivity during ongoing antipsychotic treatment leads to treatment failure over time. J Neurosci. 2007;27(11):2979-2986.

14. Thelma B, Srivastava V, Tiwari AK. Genetic underpinnings of tardive dyskinesia: passing the baton to pharmacogenetics. Pharmacogenomics. 2008;9(9):1285-1306.

15. Keith SJ, Kane JM. Partial compliance and patient consequences in schizophrenia: our patients can do better. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(11):1308-1315.

16. Lieberman JA, Saltz BL, Johns CA, et al. The effects of clozapine on tardive dyskinesia. Br J Psychiatry. 1991;158:503-510.

17. Farah A. Atypicality of atypical antipsychotics. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;7(6):268-274.

18. Rana AQ, Chaudry ZM, Blanchet PJ. New and emerging treatments for symptomatic tardive dyskinesia. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2013;7:1329-1340.

19. Shekelle PG, Woolf SH, Eccles M, et al. Developing clinical guidelines. West J Med. 1999;170(6):348-351.

20. Cloud LJ, Zutshi D, Factor SA. Tardive dyskinesia: therapeutic options for an increasingly common disorder. Neurotherapeutics. 2014;11(1):166-176.

21. Urbano M, Spiegel D, Rai A. Atypical antipsychotic withdrawal dyskinesia in 4 patients with mood disorders. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27(6):705-707.

22. Pani L, Pira L, Marchese G. Antipsychotic efficacy: relationship to optimal D2-receptor occupancy. Eur Psychiatry. 2007;22(5):267-275.

CASE Insurer denies drug coverage

Ms. X, age 65, has a 35-year history of bipolar I disorder (BD I) characterized by psychotic mania and severe suicidal depression. For the past year, her symptoms have been well controlled with aripiprazole, 5 mg/d; trazodone, 50 mg at bedtime; and citalopram, 20 mg/d. Because her health insurance has changed, Ms. X asks to be switched to an alternative antipsychotic because the new provider denied coverage of aripiprazole.

While taking aripiprazole, Ms. X did not report any extrapyramidal side effects, including tardive dyskinesia. Her Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) score is 4. No significant abnormal movements were noted on examination during previous medication management sessions.

We decide to replace aripiprazole with quetiapine, 50 mg/d. At a 2-week follow-up visit, Ms. X is noted to have euphoric mood and reduced need to sleep, flight of ideas, increased talkativeness, and paranoia. We also notice that she has significant tongue rolling and lip smacking, which she says started 10 days after changing from aripiprazole to quetiapine. Her AIMS score is 17.

What could be causing Ms. X’s tongue rolling and lip smacking?

a) an irreversible syndrome usually starting after 1 or 2 years of continuous exposure to antipsychotics

b) a self-limited condition expected to resolve completely within 12 weeks

c) an acute manifestation of an antipsychotic that can respond to an anticholinergic agent

d) none of the above

The authors’ observations

Tardive dyskinesia (TD) refers to at least moderate abnormal involuntary movements in ≥1 areas of the body or at least mild movements in ≥2 areas of the body, developing after ≥3 months of cumulative exposure (continuous or discontinuous) to dopamine D2 receptor-blocking agents.1 AIMS is a 14-item, clinician-administered questionnaire designed to evaluate such movements and track their severity over time. The first 10 items are rated on 5-point scale (0 = none; 1 = minimal; 2 = mild; 3 = moderate; 4 = severe), with items 1 to 4 assessing orofacial movements, 5 to 7 assessing extremity and truncal movements, and 8 to 10 assessing overall severity, impairment, and subjective distress. Items 11 to 13 assess dental status because lack of teeth can result in oral movements mimicking TDs. The last item assesses whether these movements disappear during sleep.

HISTORY Poor response

Ms. X was given a diagnosis of BD I at age 30; she first started taking antipsychotics 10 years later. Previous psychotropic trials included lamotrigine, divalproex sodium, risperidone, and ziprasidone, which were ineffective or poorly tolerated. Her medical history includes obstructive sleep apnea, narcolepsy, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, fibromyalgia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and hypothyroidism. She takes metformin, omeprazole, pravastatin, carvedilol, insulin, levothyroxine, methylphenidate (for hypersomnia), and enalapril.

What is the next best step in management?

a) discontinue quetiapine

b) replace quetiapine with clozapine

c) increase quetiapine to target manic symptoms and reassess in a few weeks

d) continue quetiapine and treat abnormal movements with benztropine

TREATMENT Increase dosage

We increase quetiapine to 150 mg/d to target Ms. X’s manic symptoms. She is scheduled for a follow-up visit in 4 weeks but is instructed to return to the clinic earlier if her manic symptoms do not improve. At the 4-week follow-up visit, Ms. X does not have any abnormal movements and her manic symptoms have resolved. Her AIMS score is 4. Her husband reports that her abnormal movements resolved 4 days after increasing quetiapine to 150 mg/d.

The authors’ observations

Second-generation antipsychotics are known to have a lower risk of extrapyramidal adverse reactions compared with older first-generation antipsychotics.2,3 TD differs from other extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) because of its delayed onset. Risk factors for TD include:

• female sex

• age >50

• history of brain damage

• long-term antipsychotic use

• diagnosis of a mood disorder.

Gardos et al4 described 2 other forms of delayed dyskinesias related to antipsychotic use but resulting from antipsychotic discontinuation: withdrawal dyskinesia and covert dyskinesia. Evidence for these types of antipsychotic discontinuation syndromes mostly is anecdotal.5,6Table 1 highlights 3 different types of dyskinesias and their management.

Withdrawal dyskinesia has been described as a syndrome resembling TD that appears after discontinuation or dosage reduction of an antipsychotic in a patient who does not have an earlier TD diagnosis.7 The prevalence of withdrawal dyskinesia among patients undergoing antipsychotic discontinuation is approximately 30%.8 Cases of withdrawal dyskinesia are self-limited and resolve in 1 to 3 months.9,10 We believe that Ms. X’s movement disorder was withdrawal dyskinesia from aripiprazole because her symptoms started 10 days after the drug was discontinued, and was self-limited and reversible.

Similar to TD, withdrawal dyskinesia can present in different forms:

• tongue protrusion movements

• facial grimacing

• ticks

• chorea

• tremors