User login

‘Med check’ appointments: How to minimize your malpractice risk

Medical malpractice claims can arise in any type of health care setting. The purpose of this article is to discuss the risk of medical malpractice suits in the context of brief “med checks,” which are 15- to 20-minute follow-up appointments for psychiatric outpatient medication management. Similar issues arise in brief new patient and transfer visits.

Malpractice hinges on ‘reasonableness’

Malpractice is an allegation of professional negligence.1 More specifically, it is an allegation that a clinician violated an existing duty by deviating from the standard of care, and that deviation caused damages.2 Medical malpractice claims involve questions about whether there was a deviation from the standard of care (whether the clinician failed to exercise a reasonable degree of skill and care given the context of the situation) and whether there was causation (whether a deviation caused a patient’s damages).3 These are fact-based determinations. Thus, the legal resolution of a malpractice claim is based on the facts of each specific case.

The advisability of 15-minute med checks and the associated limitation on a clinician’s ability to provide talk therapy are beyond the scope of this article. What is clear, however, is that not all brief med check appointments are created equal. Their safety and efficacy are dictated by the milieu in which they exist.

Practically speaking, although many factors need to be considered, the standard of care in a medical malpractice lawsuit is based on reasonableness.4-6 One strategy to proactively manage your malpractice risk is to consider—either for your existing job or before accepting a new position—whether your agency’s setup for brief med checks will allow you to practice reasonably. This article provides information to help you answer this question and describes a hypothetical case vignette to illustrate how certain factors might help lower the chances of facing a malpractice suit.

Established patients

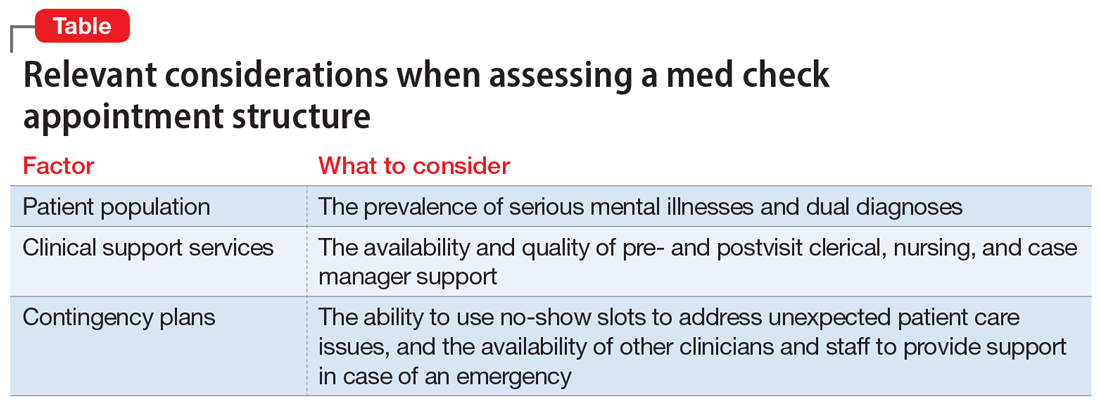

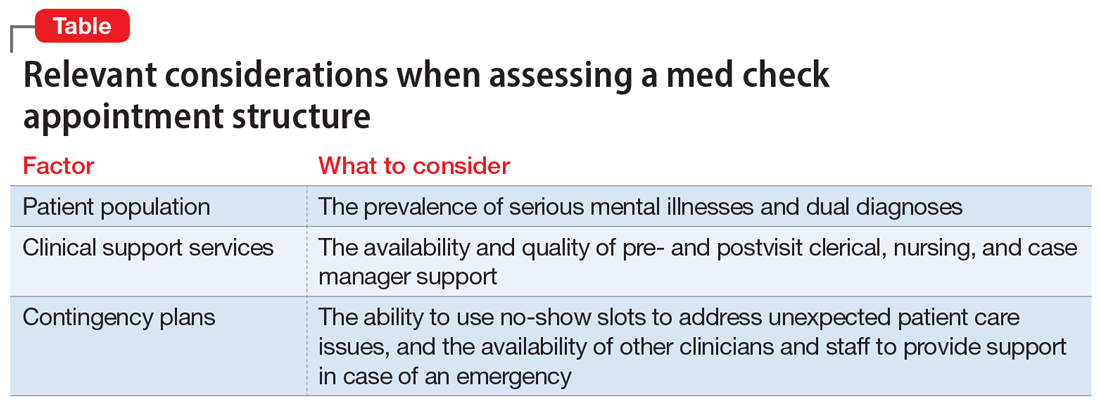

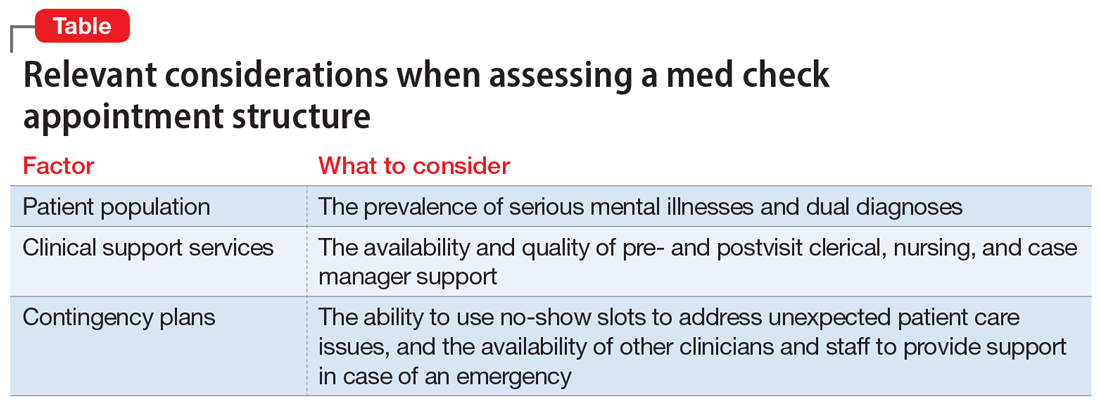

In med check appointments for established patients, consider the patient population, the availability of pre- and postvisit support services, and contingency plans (Table).

Different patient populations require different levels of treatment. Consider, for example, a patient with anxiety and trauma who is actively engaged with a therapist who works at the same agency as their psychiatrist, where the medication management appointments are solely for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor refills. Compare that to a dual-diagnosis patient—with a psychotic and substance use disorder—who has had poor medication compliance and frequent rehospitalizations. The first patient is more likely to be reasonably managed in a 15-minute med check. The second patient would need significantly more pre- and postvisit support services. This consideration is relevant from a clinical perspective, and if a bad outcome occurs, from a malpractice perspective. Patient populations are not homogeneous; the reasonableness of a clinician’s actions during a brief med check visit depends on the specific patient.

Pre- and postvisit support services vary greatly from clinic to clinic. They range from clerical support (eg, calling a pharmacy to ensure that a patient’s medication is available for same-day pickup) to nursing support (eg, an injection nurse who is on site and can immediately provide a patient with a missed injection) to case manager support (eg, a case manager to facilitate coordination of care, such as by having a patient fill out record releases and then working to ensure that relevant hospital records are received prior to the next visit). The real-world availability of these services can determine the feasibility of safely conducting a 15-minute med check visit.

Continue to: Regardless of the patient population...

Regardless of the patient population, unexpected situations will arise. It could be a patient with posttraumatic stress disorder who was recently retraumatized and is in the midst of disclosing this new trauma at the end of a 15-minute visit. Or it could be a patient with dual diagnoses who comes to the agency intoxicated and manic, describing a plan to kill his neighbor with a shotgun. A clinician’s ability to meet the standard of care, and act reasonably within the confines of a brief med check structure, can thus depend on whether there are means of adequately managing such emergent situations.

Some clinics have fairly high no-show rates. Leaving no-show slots open for administrative time can provide a means of managing emergent situations. If, however, they are automatically rebooked with walk-ins, brief visits become more challenging. Thus, when assessing contingency plan logistics, consider the no-show rate, what happens when there are no-shows, how many other clinicians are available on a given day, and whether staff is available to provide support (eg, sitting with a patient while waiting for an ambulance).

New and transfer patients

Brief visits for new or transfer patients require the same assessment described above. However, there are additional considerations regarding previsit support services. Some clinics use clinical social workers to perform intake evaluations before a new patient sees the psychiatrist. A high-quality intake evaluation can allow a psychiatrist to focus, in a shorter amount of time, on a patient’s medication needs. An additional time saver is having support staff who will obtain relevant medical records before a patient’s first psychiatric visit. Such actions can greatly increase the efficacy of a new patient appointment for the prescribing clinician.

The reliability of and level of detail assessed in prior evaluations can be particularly relevant when considering a job providing coverage as locum tenens, when all patients will be new to you. Unfortunately, if you are not employed at a clinic, it can be hard to assess this ahead of time. If you know colleagues in the area where you are considering taking a locum position, ask for their opinions about the quality of work at the agency.

Case vignette

Mr. J is a 30-year-old man with schizoaffective disorder. For several years, he has been followed once every 4 weeks at the local clinic. During the first year of treatment, he had numerous hospitalizations due to medication noncompliance, psychotic episodes, and threats of violence against his mother. For the past year, he had been stable on the same dose of an oral antipsychotic medication (risperidone 2 mg twice a day). Then he stopped taking his medication, became increasingly psychotic, and, while holding a butcher knife, threatened to kill his mother. His mother called 911 and Mr. J was hospitalized.

Continue to: While in the hospital...

While in the hospital, Mr. J was restarted on risperidone 2 mg twice a day, and lithium 600 mg twice a day was added. As part of discharge planning, the hospital social worker set up an outpatient appointment with Dr. R, Mr. J’s treating psychiatrist at the clinic. That appointment was scheduled as a 15-minute med check. At the visit, Dr. R did not have or try to obtain a copy of the hospital discharge summary. Mr. J told Dr. R that he had been hospitalized because he had run out of his oral antipsychotic, and that it had been restarted during the hospitalization. Dr. R—who did not know about the recent incident involving a butcher knife or the subsequent medication changes—continued Mr. J’s risperidone, but did not continue his lithium because she did not know it had been added.

Dr. R scheduled a 4-week follow-up visit for Mr. J. Then she went on maternity leave. Because the agency was short-staffed, they hired Dr. C—a locum tenens—to see all of Dr. R’s established patients in 15-minute time slots.

At their first visit, Mr. J told Dr. C that he was gaining too much weight from his antipsychotic and wanted to know if it would be OK to decrease the dose. Dr. C reviewed Dr. R’s last office note but, due to limited time, did not review any other notes. Although Dr. C had 2 no-shows that day, the clinic had a policy that required Dr. C to see walk-ins whenever there was a no-show.

Dr. C did not know of Mr. J’s threats of violence or the medication changes associated with his recent hospitalization (they were not referenced in Dr. R’s last note). Dr. C decreased the dose of Mr. J’s risperidone from 2 mg twice a day to 0.5 mg twice a day. He did not do a violence risk assessment. Two weeks after the visit with Dr. C, Mr. J, who had become increasingly depressed and psychotic, killed his mother and died by suicide.

The estates of Mr. J and his mother filed a medical malpractice lawsuit against Dr. R and Dr. C. Both psychiatrists had a duty to Mr. J. Whether there was a duty to Mr. J’s mother would depend in part on the state’s duty to protect laws. Either way, the malpractice case would hinge on whether the psychiatrists’ conduct fell below the standard of care.

Continue to: In this case...

In this case, the critical issues were Dr. R’s failure to obtain and review the recent hospital records and Dr. C’s decision to decrease the antipsychotic dose. Of particular concern is Dr. C’s decision to decrease the antipsychotic dose without reviewing more information from past records, and the resultant failure to perform a violence risk assessment. These deviations cannot be blamed entirely on the brevity of the med check appointment. They could happen in a clinic that allotted longer time periods for follow-up visits, but they are, however, more likely to occur in a short med check appointment due to time constraints.

The likelihood of these errors could have been reduced by additional support services, as well as more time for Dr. C to see each patient who was new to him. For example, if there had been a support person available to obtain hospital records prior to the postdischarge appointment, Dr. R and Dr. C would have been more likely to be aware of the violent threat associated with Mr. J’s hospitalization. Additionally, if the busy clinicians had contingency plans to assess complicated patients, such as the ability to use no-show time to deal with difficult situations, Dr. C could have taken more time to review past records.

Bottom Line

When working in a setting that involves brief med check appointments, assess the agency structure, and whether it will allow you to practice reasonably. This will be relevant clinically and may reduce the risk of malpractice lawsuits. Reasonableness of a clinician’s actions is a fact-specific question and is influenced by multiple factors, including the patient population, the availability and quality of an agency’s support services, and contingency plans.

Related Resources

- Mossman D. Successfully navigating the 15-minute ‘med check.’ Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(6):40-43.

- Olfson M, Marcus SC. National trends in outpatient psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(12):1456-1463.

Drug Brand Names

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Risperidone • Risperdal

1. Malpractice. In: Garner BA, ed. Black’s Law Dictionary. 11th ed. Thomson West; 2019:1148.

2. Frierson RL, Joshi KG. Malpractice law and psychiatry: an overview. Focus. 2019;17:332-336. doi:10.1176/appi.focus.20190017

3. Negligence Based Claims. In: Boumil MM, Hattis PA, eds. Medical Liability in a Nutshell. 4th ed. West Academic Publishing; 2017:43-88

4. Peters PG. The quiet demise of deference to custom: malpractice law at the millennium. Washington and Lee Law Review. 2000;57(1):163-205. Accessed July 8, 2022. https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr/vol57/iss1/5

5. Simon RI. Standard-of-care testimony: best practices or reasonable care? J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2005;33(1):8-11. Accessed July 8, 2022. http://jaapl.org/content/33/1/8

6. Behrens SA. Call in Houdini: the time has come to be released from the geographic straightjacket known as the locality rule. Drake Law Review. 2008; 56(3):753-790. Accessed June 20, 2022. https://lawreviewdrake.files.wordpress.com/2015/06/lrvol56-3_behrens.pdf

Medical malpractice claims can arise in any type of health care setting. The purpose of this article is to discuss the risk of medical malpractice suits in the context of brief “med checks,” which are 15- to 20-minute follow-up appointments for psychiatric outpatient medication management. Similar issues arise in brief new patient and transfer visits.

Malpractice hinges on ‘reasonableness’

Malpractice is an allegation of professional negligence.1 More specifically, it is an allegation that a clinician violated an existing duty by deviating from the standard of care, and that deviation caused damages.2 Medical malpractice claims involve questions about whether there was a deviation from the standard of care (whether the clinician failed to exercise a reasonable degree of skill and care given the context of the situation) and whether there was causation (whether a deviation caused a patient’s damages).3 These are fact-based determinations. Thus, the legal resolution of a malpractice claim is based on the facts of each specific case.

The advisability of 15-minute med checks and the associated limitation on a clinician’s ability to provide talk therapy are beyond the scope of this article. What is clear, however, is that not all brief med check appointments are created equal. Their safety and efficacy are dictated by the milieu in which they exist.

Practically speaking, although many factors need to be considered, the standard of care in a medical malpractice lawsuit is based on reasonableness.4-6 One strategy to proactively manage your malpractice risk is to consider—either for your existing job or before accepting a new position—whether your agency’s setup for brief med checks will allow you to practice reasonably. This article provides information to help you answer this question and describes a hypothetical case vignette to illustrate how certain factors might help lower the chances of facing a malpractice suit.

Established patients

In med check appointments for established patients, consider the patient population, the availability of pre- and postvisit support services, and contingency plans (Table).

Different patient populations require different levels of treatment. Consider, for example, a patient with anxiety and trauma who is actively engaged with a therapist who works at the same agency as their psychiatrist, where the medication management appointments are solely for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor refills. Compare that to a dual-diagnosis patient—with a psychotic and substance use disorder—who has had poor medication compliance and frequent rehospitalizations. The first patient is more likely to be reasonably managed in a 15-minute med check. The second patient would need significantly more pre- and postvisit support services. This consideration is relevant from a clinical perspective, and if a bad outcome occurs, from a malpractice perspective. Patient populations are not homogeneous; the reasonableness of a clinician’s actions during a brief med check visit depends on the specific patient.

Pre- and postvisit support services vary greatly from clinic to clinic. They range from clerical support (eg, calling a pharmacy to ensure that a patient’s medication is available for same-day pickup) to nursing support (eg, an injection nurse who is on site and can immediately provide a patient with a missed injection) to case manager support (eg, a case manager to facilitate coordination of care, such as by having a patient fill out record releases and then working to ensure that relevant hospital records are received prior to the next visit). The real-world availability of these services can determine the feasibility of safely conducting a 15-minute med check visit.

Continue to: Regardless of the patient population...

Regardless of the patient population, unexpected situations will arise. It could be a patient with posttraumatic stress disorder who was recently retraumatized and is in the midst of disclosing this new trauma at the end of a 15-minute visit. Or it could be a patient with dual diagnoses who comes to the agency intoxicated and manic, describing a plan to kill his neighbor with a shotgun. A clinician’s ability to meet the standard of care, and act reasonably within the confines of a brief med check structure, can thus depend on whether there are means of adequately managing such emergent situations.

Some clinics have fairly high no-show rates. Leaving no-show slots open for administrative time can provide a means of managing emergent situations. If, however, they are automatically rebooked with walk-ins, brief visits become more challenging. Thus, when assessing contingency plan logistics, consider the no-show rate, what happens when there are no-shows, how many other clinicians are available on a given day, and whether staff is available to provide support (eg, sitting with a patient while waiting for an ambulance).

New and transfer patients

Brief visits for new or transfer patients require the same assessment described above. However, there are additional considerations regarding previsit support services. Some clinics use clinical social workers to perform intake evaluations before a new patient sees the psychiatrist. A high-quality intake evaluation can allow a psychiatrist to focus, in a shorter amount of time, on a patient’s medication needs. An additional time saver is having support staff who will obtain relevant medical records before a patient’s first psychiatric visit. Such actions can greatly increase the efficacy of a new patient appointment for the prescribing clinician.

The reliability of and level of detail assessed in prior evaluations can be particularly relevant when considering a job providing coverage as locum tenens, when all patients will be new to you. Unfortunately, if you are not employed at a clinic, it can be hard to assess this ahead of time. If you know colleagues in the area where you are considering taking a locum position, ask for their opinions about the quality of work at the agency.

Case vignette

Mr. J is a 30-year-old man with schizoaffective disorder. For several years, he has been followed once every 4 weeks at the local clinic. During the first year of treatment, he had numerous hospitalizations due to medication noncompliance, psychotic episodes, and threats of violence against his mother. For the past year, he had been stable on the same dose of an oral antipsychotic medication (risperidone 2 mg twice a day). Then he stopped taking his medication, became increasingly psychotic, and, while holding a butcher knife, threatened to kill his mother. His mother called 911 and Mr. J was hospitalized.

Continue to: While in the hospital...

While in the hospital, Mr. J was restarted on risperidone 2 mg twice a day, and lithium 600 mg twice a day was added. As part of discharge planning, the hospital social worker set up an outpatient appointment with Dr. R, Mr. J’s treating psychiatrist at the clinic. That appointment was scheduled as a 15-minute med check. At the visit, Dr. R did not have or try to obtain a copy of the hospital discharge summary. Mr. J told Dr. R that he had been hospitalized because he had run out of his oral antipsychotic, and that it had been restarted during the hospitalization. Dr. R—who did not know about the recent incident involving a butcher knife or the subsequent medication changes—continued Mr. J’s risperidone, but did not continue his lithium because she did not know it had been added.

Dr. R scheduled a 4-week follow-up visit for Mr. J. Then she went on maternity leave. Because the agency was short-staffed, they hired Dr. C—a locum tenens—to see all of Dr. R’s established patients in 15-minute time slots.

At their first visit, Mr. J told Dr. C that he was gaining too much weight from his antipsychotic and wanted to know if it would be OK to decrease the dose. Dr. C reviewed Dr. R’s last office note but, due to limited time, did not review any other notes. Although Dr. C had 2 no-shows that day, the clinic had a policy that required Dr. C to see walk-ins whenever there was a no-show.

Dr. C did not know of Mr. J’s threats of violence or the medication changes associated with his recent hospitalization (they were not referenced in Dr. R’s last note). Dr. C decreased the dose of Mr. J’s risperidone from 2 mg twice a day to 0.5 mg twice a day. He did not do a violence risk assessment. Two weeks after the visit with Dr. C, Mr. J, who had become increasingly depressed and psychotic, killed his mother and died by suicide.

The estates of Mr. J and his mother filed a medical malpractice lawsuit against Dr. R and Dr. C. Both psychiatrists had a duty to Mr. J. Whether there was a duty to Mr. J’s mother would depend in part on the state’s duty to protect laws. Either way, the malpractice case would hinge on whether the psychiatrists’ conduct fell below the standard of care.

Continue to: In this case...

In this case, the critical issues were Dr. R’s failure to obtain and review the recent hospital records and Dr. C’s decision to decrease the antipsychotic dose. Of particular concern is Dr. C’s decision to decrease the antipsychotic dose without reviewing more information from past records, and the resultant failure to perform a violence risk assessment. These deviations cannot be blamed entirely on the brevity of the med check appointment. They could happen in a clinic that allotted longer time periods for follow-up visits, but they are, however, more likely to occur in a short med check appointment due to time constraints.

The likelihood of these errors could have been reduced by additional support services, as well as more time for Dr. C to see each patient who was new to him. For example, if there had been a support person available to obtain hospital records prior to the postdischarge appointment, Dr. R and Dr. C would have been more likely to be aware of the violent threat associated with Mr. J’s hospitalization. Additionally, if the busy clinicians had contingency plans to assess complicated patients, such as the ability to use no-show time to deal with difficult situations, Dr. C could have taken more time to review past records.

Bottom Line

When working in a setting that involves brief med check appointments, assess the agency structure, and whether it will allow you to practice reasonably. This will be relevant clinically and may reduce the risk of malpractice lawsuits. Reasonableness of a clinician’s actions is a fact-specific question and is influenced by multiple factors, including the patient population, the availability and quality of an agency’s support services, and contingency plans.

Related Resources

- Mossman D. Successfully navigating the 15-minute ‘med check.’ Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(6):40-43.

- Olfson M, Marcus SC. National trends in outpatient psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(12):1456-1463.

Drug Brand Names

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Risperidone • Risperdal

Medical malpractice claims can arise in any type of health care setting. The purpose of this article is to discuss the risk of medical malpractice suits in the context of brief “med checks,” which are 15- to 20-minute follow-up appointments for psychiatric outpatient medication management. Similar issues arise in brief new patient and transfer visits.

Malpractice hinges on ‘reasonableness’

Malpractice is an allegation of professional negligence.1 More specifically, it is an allegation that a clinician violated an existing duty by deviating from the standard of care, and that deviation caused damages.2 Medical malpractice claims involve questions about whether there was a deviation from the standard of care (whether the clinician failed to exercise a reasonable degree of skill and care given the context of the situation) and whether there was causation (whether a deviation caused a patient’s damages).3 These are fact-based determinations. Thus, the legal resolution of a malpractice claim is based on the facts of each specific case.

The advisability of 15-minute med checks and the associated limitation on a clinician’s ability to provide talk therapy are beyond the scope of this article. What is clear, however, is that not all brief med check appointments are created equal. Their safety and efficacy are dictated by the milieu in which they exist.

Practically speaking, although many factors need to be considered, the standard of care in a medical malpractice lawsuit is based on reasonableness.4-6 One strategy to proactively manage your malpractice risk is to consider—either for your existing job or before accepting a new position—whether your agency’s setup for brief med checks will allow you to practice reasonably. This article provides information to help you answer this question and describes a hypothetical case vignette to illustrate how certain factors might help lower the chances of facing a malpractice suit.

Established patients

In med check appointments for established patients, consider the patient population, the availability of pre- and postvisit support services, and contingency plans (Table).

Different patient populations require different levels of treatment. Consider, for example, a patient with anxiety and trauma who is actively engaged with a therapist who works at the same agency as their psychiatrist, where the medication management appointments are solely for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor refills. Compare that to a dual-diagnosis patient—with a psychotic and substance use disorder—who has had poor medication compliance and frequent rehospitalizations. The first patient is more likely to be reasonably managed in a 15-minute med check. The second patient would need significantly more pre- and postvisit support services. This consideration is relevant from a clinical perspective, and if a bad outcome occurs, from a malpractice perspective. Patient populations are not homogeneous; the reasonableness of a clinician’s actions during a brief med check visit depends on the specific patient.

Pre- and postvisit support services vary greatly from clinic to clinic. They range from clerical support (eg, calling a pharmacy to ensure that a patient’s medication is available for same-day pickup) to nursing support (eg, an injection nurse who is on site and can immediately provide a patient with a missed injection) to case manager support (eg, a case manager to facilitate coordination of care, such as by having a patient fill out record releases and then working to ensure that relevant hospital records are received prior to the next visit). The real-world availability of these services can determine the feasibility of safely conducting a 15-minute med check visit.

Continue to: Regardless of the patient population...

Regardless of the patient population, unexpected situations will arise. It could be a patient with posttraumatic stress disorder who was recently retraumatized and is in the midst of disclosing this new trauma at the end of a 15-minute visit. Or it could be a patient with dual diagnoses who comes to the agency intoxicated and manic, describing a plan to kill his neighbor with a shotgun. A clinician’s ability to meet the standard of care, and act reasonably within the confines of a brief med check structure, can thus depend on whether there are means of adequately managing such emergent situations.

Some clinics have fairly high no-show rates. Leaving no-show slots open for administrative time can provide a means of managing emergent situations. If, however, they are automatically rebooked with walk-ins, brief visits become more challenging. Thus, when assessing contingency plan logistics, consider the no-show rate, what happens when there are no-shows, how many other clinicians are available on a given day, and whether staff is available to provide support (eg, sitting with a patient while waiting for an ambulance).

New and transfer patients

Brief visits for new or transfer patients require the same assessment described above. However, there are additional considerations regarding previsit support services. Some clinics use clinical social workers to perform intake evaluations before a new patient sees the psychiatrist. A high-quality intake evaluation can allow a psychiatrist to focus, in a shorter amount of time, on a patient’s medication needs. An additional time saver is having support staff who will obtain relevant medical records before a patient’s first psychiatric visit. Such actions can greatly increase the efficacy of a new patient appointment for the prescribing clinician.

The reliability of and level of detail assessed in prior evaluations can be particularly relevant when considering a job providing coverage as locum tenens, when all patients will be new to you. Unfortunately, if you are not employed at a clinic, it can be hard to assess this ahead of time. If you know colleagues in the area where you are considering taking a locum position, ask for their opinions about the quality of work at the agency.

Case vignette

Mr. J is a 30-year-old man with schizoaffective disorder. For several years, he has been followed once every 4 weeks at the local clinic. During the first year of treatment, he had numerous hospitalizations due to medication noncompliance, psychotic episodes, and threats of violence against his mother. For the past year, he had been stable on the same dose of an oral antipsychotic medication (risperidone 2 mg twice a day). Then he stopped taking his medication, became increasingly psychotic, and, while holding a butcher knife, threatened to kill his mother. His mother called 911 and Mr. J was hospitalized.

Continue to: While in the hospital...

While in the hospital, Mr. J was restarted on risperidone 2 mg twice a day, and lithium 600 mg twice a day was added. As part of discharge planning, the hospital social worker set up an outpatient appointment with Dr. R, Mr. J’s treating psychiatrist at the clinic. That appointment was scheduled as a 15-minute med check. At the visit, Dr. R did not have or try to obtain a copy of the hospital discharge summary. Mr. J told Dr. R that he had been hospitalized because he had run out of his oral antipsychotic, and that it had been restarted during the hospitalization. Dr. R—who did not know about the recent incident involving a butcher knife or the subsequent medication changes—continued Mr. J’s risperidone, but did not continue his lithium because she did not know it had been added.

Dr. R scheduled a 4-week follow-up visit for Mr. J. Then she went on maternity leave. Because the agency was short-staffed, they hired Dr. C—a locum tenens—to see all of Dr. R’s established patients in 15-minute time slots.

At their first visit, Mr. J told Dr. C that he was gaining too much weight from his antipsychotic and wanted to know if it would be OK to decrease the dose. Dr. C reviewed Dr. R’s last office note but, due to limited time, did not review any other notes. Although Dr. C had 2 no-shows that day, the clinic had a policy that required Dr. C to see walk-ins whenever there was a no-show.

Dr. C did not know of Mr. J’s threats of violence or the medication changes associated with his recent hospitalization (they were not referenced in Dr. R’s last note). Dr. C decreased the dose of Mr. J’s risperidone from 2 mg twice a day to 0.5 mg twice a day. He did not do a violence risk assessment. Two weeks after the visit with Dr. C, Mr. J, who had become increasingly depressed and psychotic, killed his mother and died by suicide.

The estates of Mr. J and his mother filed a medical malpractice lawsuit against Dr. R and Dr. C. Both psychiatrists had a duty to Mr. J. Whether there was a duty to Mr. J’s mother would depend in part on the state’s duty to protect laws. Either way, the malpractice case would hinge on whether the psychiatrists’ conduct fell below the standard of care.

Continue to: In this case...

In this case, the critical issues were Dr. R’s failure to obtain and review the recent hospital records and Dr. C’s decision to decrease the antipsychotic dose. Of particular concern is Dr. C’s decision to decrease the antipsychotic dose without reviewing more information from past records, and the resultant failure to perform a violence risk assessment. These deviations cannot be blamed entirely on the brevity of the med check appointment. They could happen in a clinic that allotted longer time periods for follow-up visits, but they are, however, more likely to occur in a short med check appointment due to time constraints.

The likelihood of these errors could have been reduced by additional support services, as well as more time for Dr. C to see each patient who was new to him. For example, if there had been a support person available to obtain hospital records prior to the postdischarge appointment, Dr. R and Dr. C would have been more likely to be aware of the violent threat associated with Mr. J’s hospitalization. Additionally, if the busy clinicians had contingency plans to assess complicated patients, such as the ability to use no-show time to deal with difficult situations, Dr. C could have taken more time to review past records.

Bottom Line

When working in a setting that involves brief med check appointments, assess the agency structure, and whether it will allow you to practice reasonably. This will be relevant clinically and may reduce the risk of malpractice lawsuits. Reasonableness of a clinician’s actions is a fact-specific question and is influenced by multiple factors, including the patient population, the availability and quality of an agency’s support services, and contingency plans.

Related Resources

- Mossman D. Successfully navigating the 15-minute ‘med check.’ Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(6):40-43.

- Olfson M, Marcus SC. National trends in outpatient psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(12):1456-1463.

Drug Brand Names

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Risperidone • Risperdal

1. Malpractice. In: Garner BA, ed. Black’s Law Dictionary. 11th ed. Thomson West; 2019:1148.

2. Frierson RL, Joshi KG. Malpractice law and psychiatry: an overview. Focus. 2019;17:332-336. doi:10.1176/appi.focus.20190017

3. Negligence Based Claims. In: Boumil MM, Hattis PA, eds. Medical Liability in a Nutshell. 4th ed. West Academic Publishing; 2017:43-88

4. Peters PG. The quiet demise of deference to custom: malpractice law at the millennium. Washington and Lee Law Review. 2000;57(1):163-205. Accessed July 8, 2022. https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr/vol57/iss1/5

5. Simon RI. Standard-of-care testimony: best practices or reasonable care? J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2005;33(1):8-11. Accessed July 8, 2022. http://jaapl.org/content/33/1/8

6. Behrens SA. Call in Houdini: the time has come to be released from the geographic straightjacket known as the locality rule. Drake Law Review. 2008; 56(3):753-790. Accessed June 20, 2022. https://lawreviewdrake.files.wordpress.com/2015/06/lrvol56-3_behrens.pdf

1. Malpractice. In: Garner BA, ed. Black’s Law Dictionary. 11th ed. Thomson West; 2019:1148.

2. Frierson RL, Joshi KG. Malpractice law and psychiatry: an overview. Focus. 2019;17:332-336. doi:10.1176/appi.focus.20190017

3. Negligence Based Claims. In: Boumil MM, Hattis PA, eds. Medical Liability in a Nutshell. 4th ed. West Academic Publishing; 2017:43-88

4. Peters PG. The quiet demise of deference to custom: malpractice law at the millennium. Washington and Lee Law Review. 2000;57(1):163-205. Accessed July 8, 2022. https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr/vol57/iss1/5

5. Simon RI. Standard-of-care testimony: best practices or reasonable care? J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2005;33(1):8-11. Accessed July 8, 2022. http://jaapl.org/content/33/1/8

6. Behrens SA. Call in Houdini: the time has come to be released from the geographic straightjacket known as the locality rule. Drake Law Review. 2008; 56(3):753-790. Accessed June 20, 2022. https://lawreviewdrake.files.wordpress.com/2015/06/lrvol56-3_behrens.pdf

Evaluating suicidality

From paranoid fear to completed homicide

A crescendo of paranoid fear sharply increases the likelihood that a person will kill his (her) misperceived persecutor. Persecutory delusions are more likely to lead to homicide than any other psychiatric symptom.1 If people define a delusional situation as real, the situation is real in its consequences.

Based on my experience performing more than 100 insanity evaluations of paranoid persons charged with murder, I have identified 4 paranoid motives for homicide.

Self-defense. The most common paranoid motive for murder is the misperceived need to defend one’s self.

A steel worker believed that there was a conspiracy to kill him. His wife insisted that he go to a hospital emergency room for an evaluation. He then concluded that his wife was in on the conspiracy and stabbed her to death.

Defense of one’s manhood. Homosexual panic occurs in men who think of themselves as heterosexual.

A man with paranoid schizophrenia developed a delusion that his former high school football coach was having the entire team rape him at night. He shot the coach 6 times in front of 22 witnesses.

Defense of one’s children. A parent may kill to save her (his) children’s souls.

A deeply religious woman developed persecutory delusions that her 9-year-old son and 3-year-old daughter were going to be kidnapped and forced to make child pornography. To save her children’s souls, she stabbed her children more than 100 times.

Defense of the world. Homicide may be seen as a way to protect all humankind.

A woman developed a delusion that her father was Satan and would kill her. She believed that if she could kill her father (Satan) and his family she would save herself and bring about world peace. After killing her father, she thrust the sharp end of a tire iron into her grandmother’s umbilicus and vagina because those body parts were involved in “birthing Satan.”

Questioning to determine risk

I have found that, when evaluating a paranoid, delusional person for potential violence, it is better to present that person with a hypothetical question about encountering his perceived persecutor than with a generic question about homicidality.2 For example, a delusional person who reports that he was afraid of being killed by the Mafia could be asked, “If you were walking down an alley and encountered a man dressed like a Mafia hit man with a bulge in his jacket, what would you do?” One interviewee might reply, “The Mafia has so much power there is nothing I could do.” Another might answer, “As soon as I got close enough I would blow his head off with my .357 Magnum.” Although both people would be reporting honestly that they have no homicidal ideas, the latter has a much lower threshold for killing in misperceived self-defense.

Summing up

Persecutory delusions are more likely than any other psychiatric symptom to lead a psychotic person to commit homicide. The killing might be motivated by misperceived self-defense, defense of one’s manhood, defense of one’s children, or defense of the world.

A crescendo of paranoid fear sharply increases the likelihood that a person will kill his (her) misperceived persecutor. Persecutory delusions are more likely to lead to homicide than any other psychiatric symptom.1 If people define a delusional situation as real, the situation is real in its consequences.

Based on my experience performing more than 100 insanity evaluations of paranoid persons charged with murder, I have identified 4 paranoid motives for homicide.

Self-defense. The most common paranoid motive for murder is the misperceived need to defend one’s self.

A steel worker believed that there was a conspiracy to kill him. His wife insisted that he go to a hospital emergency room for an evaluation. He then concluded that his wife was in on the conspiracy and stabbed her to death.

Defense of one’s manhood. Homosexual panic occurs in men who think of themselves as heterosexual.

A man with paranoid schizophrenia developed a delusion that his former high school football coach was having the entire team rape him at night. He shot the coach 6 times in front of 22 witnesses.

Defense of one’s children. A parent may kill to save her (his) children’s souls.

A deeply religious woman developed persecutory delusions that her 9-year-old son and 3-year-old daughter were going to be kidnapped and forced to make child pornography. To save her children’s souls, she stabbed her children more than 100 times.

Defense of the world. Homicide may be seen as a way to protect all humankind.

A woman developed a delusion that her father was Satan and would kill her. She believed that if she could kill her father (Satan) and his family she would save herself and bring about world peace. After killing her father, she thrust the sharp end of a tire iron into her grandmother’s umbilicus and vagina because those body parts were involved in “birthing Satan.”

Questioning to determine risk

I have found that, when evaluating a paranoid, delusional person for potential violence, it is better to present that person with a hypothetical question about encountering his perceived persecutor than with a generic question about homicidality.2 For example, a delusional person who reports that he was afraid of being killed by the Mafia could be asked, “If you were walking down an alley and encountered a man dressed like a Mafia hit man with a bulge in his jacket, what would you do?” One interviewee might reply, “The Mafia has so much power there is nothing I could do.” Another might answer, “As soon as I got close enough I would blow his head off with my .357 Magnum.” Although both people would be reporting honestly that they have no homicidal ideas, the latter has a much lower threshold for killing in misperceived self-defense.

Summing up

Persecutory delusions are more likely than any other psychiatric symptom to lead a psychotic person to commit homicide. The killing might be motivated by misperceived self-defense, defense of one’s manhood, defense of one’s children, or defense of the world.

A crescendo of paranoid fear sharply increases the likelihood that a person will kill his (her) misperceived persecutor. Persecutory delusions are more likely to lead to homicide than any other psychiatric symptom.1 If people define a delusional situation as real, the situation is real in its consequences.

Based on my experience performing more than 100 insanity evaluations of paranoid persons charged with murder, I have identified 4 paranoid motives for homicide.

Self-defense. The most common paranoid motive for murder is the misperceived need to defend one’s self.

A steel worker believed that there was a conspiracy to kill him. His wife insisted that he go to a hospital emergency room for an evaluation. He then concluded that his wife was in on the conspiracy and stabbed her to death.

Defense of one’s manhood. Homosexual panic occurs in men who think of themselves as heterosexual.

A man with paranoid schizophrenia developed a delusion that his former high school football coach was having the entire team rape him at night. He shot the coach 6 times in front of 22 witnesses.

Defense of one’s children. A parent may kill to save her (his) children’s souls.

A deeply religious woman developed persecutory delusions that her 9-year-old son and 3-year-old daughter were going to be kidnapped and forced to make child pornography. To save her children’s souls, she stabbed her children more than 100 times.

Defense of the world. Homicide may be seen as a way to protect all humankind.

A woman developed a delusion that her father was Satan and would kill her. She believed that if she could kill her father (Satan) and his family she would save herself and bring about world peace. After killing her father, she thrust the sharp end of a tire iron into her grandmother’s umbilicus and vagina because those body parts were involved in “birthing Satan.”

Questioning to determine risk

I have found that, when evaluating a paranoid, delusional person for potential violence, it is better to present that person with a hypothetical question about encountering his perceived persecutor than with a generic question about homicidality.2 For example, a delusional person who reports that he was afraid of being killed by the Mafia could be asked, “If you were walking down an alley and encountered a man dressed like a Mafia hit man with a bulge in his jacket, what would you do?” One interviewee might reply, “The Mafia has so much power there is nothing I could do.” Another might answer, “As soon as I got close enough I would blow his head off with my .357 Magnum.” Although both people would be reporting honestly that they have no homicidal ideas, the latter has a much lower threshold for killing in misperceived self-defense.

Summing up

Persecutory delusions are more likely than any other psychiatric symptom to lead a psychotic person to commit homicide. The killing might be motivated by misperceived self-defense, defense of one’s manhood, defense of one’s children, or defense of the world.

Postpartum psychosis: Strategies to protect infant and mother from harm

In June 2001, Andrea Yates drowned her 5 children ages 6 months to 7 years in the bathtub of their home. She had delusions that her house was bugged and television cameras were monitoring her mothering skills. She came to believe that “the one and only Satan” was within her, and that her children would burn in hell if she did not save their souls while they were still innocent.

Her conviction of capital murder in her first trial was overturned on appeal. She was found not guilty by reason of insanity at her retrial in 2006 and committed to a Texas state mental hospital.1

Postpartum psychosis (PPP) presents dramatically days to weeks after delivery, with wide-ranging symptoms that can include dysphoric mania and delirium. Because untreated PPP has an estimated 4% risk of infanticide (murder of the infant in the first year of life),2 and a 5% risk of suicide,3 psychiatric hospitalization usually is required to protect the mother and her baby.

The diagnosis may be missed, however, because postpartum psychotic symptoms wax and wane and suspiciousness or poor insight cause some women—such as Andrea Yates—to hide their delusional thinking from their families. This article discusses the risk factors, prevention, and treatment of PPP, including a review of:

- infanticide and suicide risks in the postpartum period

- increased susceptibility to PPP in women with bipolar disorder and other psychiatric disorders

- hospitalization for support and safety of the mother and her infant.

Risks of infanticide and suicide

A number of motives exist for infanticide (Table 1).4 Psychiatric literature shows that mothers who kill their children often have experienced psychosis, suicidality, depression, and considerable life stress.5 Common factors include alcohol use, limited social support, and a personal history of abuse. Studies on infanticide found a significant increase in common psychiatric disorders and financial stress among the mothers. Neonaticide (murder of the infant in the first day of life) generally is not related to PPP because PPP usually does not begin until after the day of delivery.6

Among women who develop psychiatric illness, homicidal ideation is more frequent in those with a perinatal onset of psychopathology.7 Infanticidal ideas and behavior are associated with psychotic ideas about the infant.8 Suicide is the cause of up to 20% of postpartum deaths.9

Table 1

Motives for infanticide: Mental illness or something else?

| Motives | Examples |

|---|---|

| Likely related to postpartum psychosis or depression | |

| Altruistic | A depressed or psychotic mother may believe she is sending her baby to heaven to prevent suffering on earth |

| A suicidal mother may kill her infant along with herself rather than leave the child alone | |

| Acutely psychotic | A mother kills her baby for no comprehensible reason, such as in response to command hallucinations or the confusion of delirium |

| Rarely related to postpartum psychosis | |

| Fatal maltreatment | ‘Battered child’ syndrome is the most common cause of infanticide; death often occurs after chronic abuse or neglect |

| A minority of perpetrators are psychotic; a mother out of touch with reality may have difficulty providing for her infant’s needs | |

| Not likely related to postpartum psychosis | |

| Unwanted child | Parent does not want child because of inconvenience or out-of-wedlock birth |

| Spouse revenge | Murder of a child to cause emotional suffering for the other parent is the least frequent motive for infanticide |

| Source: Reference 4 | |

The bipolar connection

Many factors can elevate the risk of PPP, including sleep deprivation in susceptible women, the hormonal shifts after birth, and psychiatric comorbidity (Table 2). Nearly three-fourths (>72%) of mothers with PPP have bipolar disorder or schizoaffective disorder, whereas 12% have schizophrenia.10 Some authors consider PPP to be bipolar disorder until proven otherwise. Mothers with a history of bipolar disorder or PPP have a 100-fold increase in rates of psychiatric hospitalization in the postpartum period.11

Presentation. PPP is relatively rare, occurring at a rate of 1 to 3 cases per 1,000 births. Symptoms often have an abrupt onset, within days to weeks of delivery.10 In at least one-half of cases, symptoms begin by the third postpartum day,13 when many mothers have been discharged home and may be solely responsible for their infants.

Symptoms include confusion, bizarre behaviors, hallucinations (including rarer types such as tactile and olfactory), mood lability (ranging from euphoria to depression), decreased need for sleep or insomnia, restlessness, agitation, disorganized thinking, and bizarre delusions of relatively rapid onset.13 One mother might believe God wants her baby to be sacrificed as the second coming of the Messiah, a second may believe she has special powers, and a third that her baby is defective.

Table 2

Postpartum psychosis: Risk factors supported by evidence

| Sleep deprivation in susceptible women |

| Hormonal shifts after birth (primarily the rapid drop in estrogen) |

| Psychosocial stressors such as marital problems, older age, single motherhood, lower socioeconomic status |

| Bipolar disorder or schizoaffective disorder |

| Past history of postpartum psychosis |

| Family history of postpartum psychosis |

| Previous psychiatric hospitalization, especially during the prenatal period for a bipolar or psychotic condition |

| Menstruation or cessation of lactation |

Obstetric factors that can cause a small increase in relative risk:

|

| Source: For bibliographic citations |

Differential diagnosis

When evaluating a postpartum woman with psychotic symptoms, stay in contact with her obstetrician and the child’s pediatrician. Rule out delirium and organic causes of the mother’s symptoms (Box).11

Postpartum depression (PPD) occurs in approximately 10% to 15% of new mothers.14 Depressive symptoms occur within weeks to months after delivery and often coexist with anxious symptoms. Some women with severe depression may present with psychotic symptoms. A mother may experience insomnia, sometimes not being able to sleep when the baby is sleeping. She may lack interest in caring for her baby and experience difficulty bonding.

At times it can be difficult to distinguish PPD from PPP. When evaluating a mother who is referred for “postpartum depression,” consider PPP in the differential diagnosis. A woman with PPD or PPP may report depressed mood, but in PPP this symptom usually is related to rapid mood changes. Other clinical features that point toward PPP are abnormal hallucinations (such as olfactory or tactile), hypomanic or mixed mood symptoms, and confusion.

When evaluating a postpartum woman with psychotic symptoms, stay in contact with her obstetrician and the child’s pediatrician. Rule out delirium and organic causes of the mother’s symptoms, giving special consideration to metabolic, neurologic, cardiovascular, infectious, and substance- or medication-induced origins. The extensive differential diagnosis includes:

- thyroiditis

- tumor

- CNS infection

- head injury

- embolism

- eclampsia

- substance withdrawal

- medication-induced (such as corticosteroids)

- electrolyte anomalies

- anoxia

- vitamin B12 deficiency.11

Psychosis vs OCD. Psychotic thinking and behaviors also must be differentiated from obsessive thoughts and compulsions.10,16 Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) may be exacerbated or emerge for the first time during the perinatal period.17

In postpartum OCD, women may experience intrusive thoughts of accidental or purposeful harm to their baby. As opposed to women with PPP, mothers with OCD are not out of touch with reality and their thoughts are ego-dystonic.17 When these mothers have thoughts of their infants being harmed, they realize that these thoughts are not plans but fears and they try to avoid the thoughts.

Preventing PPP

Bipolar disorder is one of the most difficult disorders to treat during pregnancy because the serious risks of untreated illness must be balanced against the potential teratogenic risk of medications. Nevertheless, proactively managing bipolar disorder during pregnancy may reduce the risk of PPP.10

Closely monitor women with a history of bipolar disorder or PPP. During pregnancy, counsel them—and their partners—to:

- anticipate that depressive or psychotic symptoms could develop within days after delivery18

- seek treatment immediately if this occurs.

Postpartum medication. Whether or not a woman with bipolar disorder takes medication during pregnancy, consider treatment with mood stabilizers or atypical antipsychotics in the postpartum to prevent PPP (Table 3). Evidence is limited, but a search of PubMed found 1 study in which prophylactic lithium was given late in the third trimester or immediately after delivery to 21 women with a history of bipolar disorder or PPP. Only 2 patients had a psychotic recurrence while on prophylactic lithium; 1 unexplained stillbirth occurred.19

A retrospective study examined the course of women with bipolar disorder, some of whom were given prophylactic mood stabilizers immediately in the postpartum. One of 14 who received antimanic agents relapsed within the first 3 months postpartum, compared with 8 of 13 who were not so treated.18

Compared with antiepileptics, less information is available about the use of atypical antipsychotics in pregnancy and lactation. Antipsychotics’ potential advantage in women at risk for PPP is that these agents may help prevent or treat both manic and psychotic symptoms.

In a small, naturalistic, prospective study, 11 women at risk for PPP received olanzapine alone or with an antidepressant or mood stabilizer for at least 4 weeks after delivery. Two (18%) experienced a postpartum mood episode, compared with 8 (57%) of 14 other at-risk women who received antidepressants, mood stabilizers, or no medication.20

When you discuss breast-feeding, consider possible risks to the neonate as well as potential sleep interruption for the mother. If a mother has a supportive partner, the partner might be put in charge of night-time feedings in a routine combining breast-feeding and bottle-feeding. In some cases you may need to recommend cessation of lactation.21

Table 3

Treating postpartum psychosis: Consider 3 components

| Component | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Hospitalization vs home care | Hospitalize in most cases because of emergent severe symptoms and fluctuating course; base decision on risk evaluation/safety issues for patient and infant After discharge, visiting nurses are useful to help monitor the mother’s condition at home |

| Psychoeducation | Educate patient, family, and social support network; address risks to mother and infant and risks in future pregnancies |

| Medication | When prescribing mood stabilizers and/or antipsychotics, consider:

|

Managing PPP

Early symptoms. Because of its severity and rapid evolution, PPP often presents as a psychiatric emergency. Monitor atrisk patients’ sleep patterns and mood for early signs of psychosis.22 Watch especially for hypomanic symptoms such as elevated or mixed mood and decreased judgment, which are common early in PPP.13

A mother with few signs of abnormal mood, good social support, and close follow-up may potentially be safely managed as an outpatient. Initial evaluation and management of PPP usually requires hospitalization, however, because of the risks of suicide, infanticide, and child maltreatment.23

Hospitalization. Mother-infant bonding is important, but safety is paramount if a mother is psychotic—especially if she is experiencing psychotic thoughts about her infant. If possible, the infant should remain with family members during the mother’s hospitalization. Supervised mother-infant visits are often arranged, as appropriate.

Mood-stabilizing medications, including antipsychotics, are mainstays of treatment.24 In some cases, conventional antipsychotics such as haloperidol may be useful because of a lower risk of weight gain or of sedation that could impair a mother’s ability to respond to her infant. Electroconvulsive therapy often yields rapid symptomatic improvement for mothers with postpartum mood or psychotic symptoms.25

Discharge planning. Assuming that the mother adheres to prescribed treatment, discharge may occur within 1 week. Plan discharge arrangements carefully (Table 4).28 A team approach can be very useful within the outpatient clinic. In the model of the Perinatal Psychiatry Clinic of Connections in suburban Cleveland, OH, the mother’s treatment team includes perinatal psychiatrists, nurses, counsellors, case managers (who do home visits), and peer counselors.

Outpatient civil commitment, in which patients are mandated to accept treatment, is an option in some jurisdictions and could help ensure that patients receive treatment consistently.

Table 4

Discharge planning for safety of mother and infant

| Notify child protective services (CPS) depending on the risk to the child. Case-by-case review is needed to assess whether the infant should be removed. CPS may put in place a plan for safety, short of removal. The plan may require that the woman continue psychiatric care |

| Meet with the patient and family to discuss her diagnosis, the risks, the importance of continued medication adherence, and the need for family or social supports to assist with child care |

| Consider engaging visiting nurses or doulas to provide help and support at home |

| Schedule frequent outpatient appointments for the mother after discharge |

| Consider family therapy after the mother has improved because of her risk for affective episodes outside the postpartum28 |

Related resources

- Altshuler L, Richards M, Yonkers K. Treating bipolar disorder during pregnancy. Current Psychiatry. 2003;2(7):14-26. www.CurrentPsychiatry.com.

- Gentile S. Infant safety with antipsychotic therapy in breastfeeding: a systematic review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(4):666-673.

- Miller LJ. Postpartum mood disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 1999.

- Stowe ZN. The use of mood stabilizers during breastfeeding. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(suppl 9):22-28.

- Toxicology Data Network (Toxnet). Literature on reproductive risks associated with psychotropics. National Library of Medicine. http://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov.

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Lithium • various

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Acknowledgement

Dr. Resnick, a forensic psychiatrist and coauthor of this article, testified for the defense in both trials of Andrea Yates.

1. Resnick PJ. The Andrea Yates case: insanity on trial. Cleveland State Law Review. 2007;55(2):147-156.

2. Altshuler LL, Hendrick V, Cohen LS. Course of mood and anxiety disorders during pregnancy and the postpartum period. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(suppl. 2):29-33.

3. Knops GG. Postpartum mood disorders. Postgrad Med. 1993;93:103-116.

4. Resnick PJ. Child murder by parents: a psychiatric review of filicide. Am J Psychiatry. 1969;126:73-82.

5. Friedman SH, Horwitz SM, Resnick PJ. Child murder by mothers: a critical analysis of the current state of knowledge and a research agenda. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1578-1587.

6. Friedman SH, Resnick PJ. Neonaticide: phenomenology and considerations for prevention. Int J Law Psychiatry. In press.

7. Wisner K, Peindl K, Hanusa BH. Symptomatology of affective and psychotic illnesses related to childbearing. J Affect Disord. 1994;30:77-87.

8. Chandra PS, Venkatasubramanian G, Thomas T. Infanticidal ideas and infanticidal behaviour in Indian women with severe postpartum psychiatric disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2002;190(7):457-461.

9. Lindahl V, Pearson JL, Colpe L. Prevalence of suicidality during pregnancy and the postpartum. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2005;8(2):77-87.

10. Sit D, Rothschild AJ, Wisner KL. A review of postpartum psychosis. J Women’s Health. 2006;15(4):352-368.

11. Attia E, Downey J, Oberman M. Postpartum psychoses. In: Miller LJ, ed. Postpartum mood disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing Inc.; 1999:99-117.

12. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

13. Heron J, McGuinness M, Blackmore ER, et al. Early postpartum symptoms in puerperal psychosis. BJOG. 2008;115(3):348-353.

14. Meltzer-Brody S, Payne J, Rubinow D. Postpartum depression: what to tell patients who breast-feed. Current Psychiatry. 2008;7(5):87-95.

15. Jennings KD, Ross S, Popper S, et al. Thoughts of harming infants in depressed and nondepressed mothers. J Affect Disord. 1999;54:21-28.

16. Wisner KL, Gracious BL, Piontek CM, et al. Postpartum disorders: phenomenology, treatment approaches, and relationship to infanticide. In: Spinelli MG, ed. Infanticide: psychosocial and legal perspectives on mothers who kill. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2003.

17. Fairbrother N, Abramowitz JS. New parenthood as a risk factors for the development of obsessional problems. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45(9):2155-2163.

18. Cohen LS, Sichel DA, Robertson LM, et al. Postpartum prophylaxis for women with bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(11):1641-1645.

19. Stewart DE, Klompenhouwer JL, Kendell RE, et al. Prophylactic lithium in puerperal psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 1991;158:393-397.

20. Sharma V, Smith A, Mazmanian D. Olanzapine in the prevention of postpartum psychosis and mood episodes in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8(4):400-404.

21. Pfuhlmann B, Stoeber G, Beckmann H. Postpartum psychoses: prognosis, risk factors, and treatment. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2002;4(3):185-190.

22. Sharma V, Mazmanian D. Sleep loss and postpartum psychosis. Bipolar Disord. 2003;5(2):98-105.

23. Lindahl V, Pearson JL, Colpe L. Prevalence of suicidality during pregnancy and the postpartum. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2005;8(2):77-87.

24. Connell M. The postpartum psychosis defense and feminism: more or less justice for women? Case Western Reserve Law Review. 2002;53:143.-

25. Forray A, Ostroff RB. The use of electroconvulsive therapy in postpartum affective disorders. J ECT. 2007;23(3):188-193.

26. Engqvist I, Nilsson A, Nilsson K, et al. Strategies in caring for women with postpartum psychosis—an interview study with psychiatric nurses. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16(7):1333-1342.

27. Robertson E, Lyons A. Living with puerperal psychosis: a qualitative analysis. Psychol Psychother. 2003;76(4):411-431.

28. Robertson E, Jones I, Haque S, et al. Risk of puerperal and non-puerperal recurrence of illness following bipolar affective puerperal (post-partum) psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:258-259.

In June 2001, Andrea Yates drowned her 5 children ages 6 months to 7 years in the bathtub of their home. She had delusions that her house was bugged and television cameras were monitoring her mothering skills. She came to believe that “the one and only Satan” was within her, and that her children would burn in hell if she did not save their souls while they were still innocent.

Her conviction of capital murder in her first trial was overturned on appeal. She was found not guilty by reason of insanity at her retrial in 2006 and committed to a Texas state mental hospital.1

Postpartum psychosis (PPP) presents dramatically days to weeks after delivery, with wide-ranging symptoms that can include dysphoric mania and delirium. Because untreated PPP has an estimated 4% risk of infanticide (murder of the infant in the first year of life),2 and a 5% risk of suicide,3 psychiatric hospitalization usually is required to protect the mother and her baby.

The diagnosis may be missed, however, because postpartum psychotic symptoms wax and wane and suspiciousness or poor insight cause some women—such as Andrea Yates—to hide their delusional thinking from their families. This article discusses the risk factors, prevention, and treatment of PPP, including a review of:

- infanticide and suicide risks in the postpartum period

- increased susceptibility to PPP in women with bipolar disorder and other psychiatric disorders

- hospitalization for support and safety of the mother and her infant.

Risks of infanticide and suicide

A number of motives exist for infanticide (Table 1).4 Psychiatric literature shows that mothers who kill their children often have experienced psychosis, suicidality, depression, and considerable life stress.5 Common factors include alcohol use, limited social support, and a personal history of abuse. Studies on infanticide found a significant increase in common psychiatric disorders and financial stress among the mothers. Neonaticide (murder of the infant in the first day of life) generally is not related to PPP because PPP usually does not begin until after the day of delivery.6

Among women who develop psychiatric illness, homicidal ideation is more frequent in those with a perinatal onset of psychopathology.7 Infanticidal ideas and behavior are associated with psychotic ideas about the infant.8 Suicide is the cause of up to 20% of postpartum deaths.9

Table 1

Motives for infanticide: Mental illness or something else?

| Motives | Examples |

|---|---|

| Likely related to postpartum psychosis or depression | |

| Altruistic | A depressed or psychotic mother may believe she is sending her baby to heaven to prevent suffering on earth |

| A suicidal mother may kill her infant along with herself rather than leave the child alone | |

| Acutely psychotic | A mother kills her baby for no comprehensible reason, such as in response to command hallucinations or the confusion of delirium |

| Rarely related to postpartum psychosis | |

| Fatal maltreatment | ‘Battered child’ syndrome is the most common cause of infanticide; death often occurs after chronic abuse or neglect |

| A minority of perpetrators are psychotic; a mother out of touch with reality may have difficulty providing for her infant’s needs | |

| Not likely related to postpartum psychosis | |

| Unwanted child | Parent does not want child because of inconvenience or out-of-wedlock birth |

| Spouse revenge | Murder of a child to cause emotional suffering for the other parent is the least frequent motive for infanticide |

| Source: Reference 4 | |

The bipolar connection

Many factors can elevate the risk of PPP, including sleep deprivation in susceptible women, the hormonal shifts after birth, and psychiatric comorbidity (Table 2). Nearly three-fourths (>72%) of mothers with PPP have bipolar disorder or schizoaffective disorder, whereas 12% have schizophrenia.10 Some authors consider PPP to be bipolar disorder until proven otherwise. Mothers with a history of bipolar disorder or PPP have a 100-fold increase in rates of psychiatric hospitalization in the postpartum period.11

Presentation. PPP is relatively rare, occurring at a rate of 1 to 3 cases per 1,000 births. Symptoms often have an abrupt onset, within days to weeks of delivery.10 In at least one-half of cases, symptoms begin by the third postpartum day,13 when many mothers have been discharged home and may be solely responsible for their infants.

Symptoms include confusion, bizarre behaviors, hallucinations (including rarer types such as tactile and olfactory), mood lability (ranging from euphoria to depression), decreased need for sleep or insomnia, restlessness, agitation, disorganized thinking, and bizarre delusions of relatively rapid onset.13 One mother might believe God wants her baby to be sacrificed as the second coming of the Messiah, a second may believe she has special powers, and a third that her baby is defective.

Table 2

Postpartum psychosis: Risk factors supported by evidence

| Sleep deprivation in susceptible women |

| Hormonal shifts after birth (primarily the rapid drop in estrogen) |

| Psychosocial stressors such as marital problems, older age, single motherhood, lower socioeconomic status |

| Bipolar disorder or schizoaffective disorder |

| Past history of postpartum psychosis |

| Family history of postpartum psychosis |

| Previous psychiatric hospitalization, especially during the prenatal period for a bipolar or psychotic condition |

| Menstruation or cessation of lactation |

Obstetric factors that can cause a small increase in relative risk:

|

| Source: For bibliographic citations |

Differential diagnosis

When evaluating a postpartum woman with psychotic symptoms, stay in contact with her obstetrician and the child’s pediatrician. Rule out delirium and organic causes of the mother’s symptoms (Box).11

Postpartum depression (PPD) occurs in approximately 10% to 15% of new mothers.14 Depressive symptoms occur within weeks to months after delivery and often coexist with anxious symptoms. Some women with severe depression may present with psychotic symptoms. A mother may experience insomnia, sometimes not being able to sleep when the baby is sleeping. She may lack interest in caring for her baby and experience difficulty bonding.

At times it can be difficult to distinguish PPD from PPP. When evaluating a mother who is referred for “postpartum depression,” consider PPP in the differential diagnosis. A woman with PPD or PPP may report depressed mood, but in PPP this symptom usually is related to rapid mood changes. Other clinical features that point toward PPP are abnormal hallucinations (such as olfactory or tactile), hypomanic or mixed mood symptoms, and confusion.

When evaluating a postpartum woman with psychotic symptoms, stay in contact with her obstetrician and the child’s pediatrician. Rule out delirium and organic causes of the mother’s symptoms, giving special consideration to metabolic, neurologic, cardiovascular, infectious, and substance- or medication-induced origins. The extensive differential diagnosis includes:

- thyroiditis

- tumor

- CNS infection

- head injury

- embolism

- eclampsia

- substance withdrawal

- medication-induced (such as corticosteroids)

- electrolyte anomalies

- anoxia

- vitamin B12 deficiency.11

Psychosis vs OCD. Psychotic thinking and behaviors also must be differentiated from obsessive thoughts and compulsions.10,16 Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) may be exacerbated or emerge for the first time during the perinatal period.17

In postpartum OCD, women may experience intrusive thoughts of accidental or purposeful harm to their baby. As opposed to women with PPP, mothers with OCD are not out of touch with reality and their thoughts are ego-dystonic.17 When these mothers have thoughts of their infants being harmed, they realize that these thoughts are not plans but fears and they try to avoid the thoughts.

Preventing PPP

Bipolar disorder is one of the most difficult disorders to treat during pregnancy because the serious risks of untreated illness must be balanced against the potential teratogenic risk of medications. Nevertheless, proactively managing bipolar disorder during pregnancy may reduce the risk of PPP.10

Closely monitor women with a history of bipolar disorder or PPP. During pregnancy, counsel them—and their partners—to:

- anticipate that depressive or psychotic symptoms could develop within days after delivery18

- seek treatment immediately if this occurs.

Postpartum medication. Whether or not a woman with bipolar disorder takes medication during pregnancy, consider treatment with mood stabilizers or atypical antipsychotics in the postpartum to prevent PPP (Table 3). Evidence is limited, but a search of PubMed found 1 study in which prophylactic lithium was given late in the third trimester or immediately after delivery to 21 women with a history of bipolar disorder or PPP. Only 2 patients had a psychotic recurrence while on prophylactic lithium; 1 unexplained stillbirth occurred.19

A retrospective study examined the course of women with bipolar disorder, some of whom were given prophylactic mood stabilizers immediately in the postpartum. One of 14 who received antimanic agents relapsed within the first 3 months postpartum, compared with 8 of 13 who were not so treated.18

Compared with antiepileptics, less information is available about the use of atypical antipsychotics in pregnancy and lactation. Antipsychotics’ potential advantage in women at risk for PPP is that these agents may help prevent or treat both manic and psychotic symptoms.

In a small, naturalistic, prospective study, 11 women at risk for PPP received olanzapine alone or with an antidepressant or mood stabilizer for at least 4 weeks after delivery. Two (18%) experienced a postpartum mood episode, compared with 8 (57%) of 14 other at-risk women who received antidepressants, mood stabilizers, or no medication.20

When you discuss breast-feeding, consider possible risks to the neonate as well as potential sleep interruption for the mother. If a mother has a supportive partner, the partner might be put in charge of night-time feedings in a routine combining breast-feeding and bottle-feeding. In some cases you may need to recommend cessation of lactation.21

Table 3

Treating postpartum psychosis: Consider 3 components

| Component | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Hospitalization vs home care | Hospitalize in most cases because of emergent severe symptoms and fluctuating course; base decision on risk evaluation/safety issues for patient and infant After discharge, visiting nurses are useful to help monitor the mother’s condition at home |

| Psychoeducation | Educate patient, family, and social support network; address risks to mother and infant and risks in future pregnancies |

| Medication | When prescribing mood stabilizers and/or antipsychotics, consider:

|

Managing PPP

Early symptoms. Because of its severity and rapid evolution, PPP often presents as a psychiatric emergency. Monitor atrisk patients’ sleep patterns and mood for early signs of psychosis.22 Watch especially for hypomanic symptoms such as elevated or mixed mood and decreased judgment, which are common early in PPP.13

A mother with few signs of abnormal mood, good social support, and close follow-up may potentially be safely managed as an outpatient. Initial evaluation and management of PPP usually requires hospitalization, however, because of the risks of suicide, infanticide, and child maltreatment.23

Hospitalization. Mother-infant bonding is important, but safety is paramount if a mother is psychotic—especially if she is experiencing psychotic thoughts about her infant. If possible, the infant should remain with family members during the mother’s hospitalization. Supervised mother-infant visits are often arranged, as appropriate.

Mood-stabilizing medications, including antipsychotics, are mainstays of treatment.24 In some cases, conventional antipsychotics such as haloperidol may be useful because of a lower risk of weight gain or of sedation that could impair a mother’s ability to respond to her infant. Electroconvulsive therapy often yields rapid symptomatic improvement for mothers with postpartum mood or psychotic symptoms.25

Discharge planning. Assuming that the mother adheres to prescribed treatment, discharge may occur within 1 week. Plan discharge arrangements carefully (Table 4).28 A team approach can be very useful within the outpatient clinic. In the model of the Perinatal Psychiatry Clinic of Connections in suburban Cleveland, OH, the mother’s treatment team includes perinatal psychiatrists, nurses, counsellors, case managers (who do home visits), and peer counselors.

Outpatient civil commitment, in which patients are mandated to accept treatment, is an option in some jurisdictions and could help ensure that patients receive treatment consistently.

Table 4

Discharge planning for safety of mother and infant

| Notify child protective services (CPS) depending on the risk to the child. Case-by-case review is needed to assess whether the infant should be removed. CPS may put in place a plan for safety, short of removal. The plan may require that the woman continue psychiatric care |

| Meet with the patient and family to discuss her diagnosis, the risks, the importance of continued medication adherence, and the need for family or social supports to assist with child care |

| Consider engaging visiting nurses or doulas to provide help and support at home |

| Schedule frequent outpatient appointments for the mother after discharge |

| Consider family therapy after the mother has improved because of her risk for affective episodes outside the postpartum28 |

Related resources