User login

Metabolic surgery for treating type 2 diabetes mellitus: Now supported by the world's leading diabetes organizations

LIMITATIONS OF LIFESTYLE MANAGEMENT AND MEDICATIONS

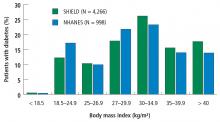

First-line therapy with lifestyle management and second-line therapy with medications, including oral agents and insulin, are the mainstays of type 2 DM therapy. Although these approaches have reduced hyperglycemia and cardiovascular mortality, many patients have poor glycemic control and develop severe diabetes-related complications. A study using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (N = 4,926) to evaluate success rates of lifestyle management plus drug therapy found that just 53% of patients with type 2 DM maintained a hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) below 7%.6 Similarly, only 51% of those patients achieved a systolic and diastolic blood pressure less than 130/80 mm Hg, and only 56% achieved a low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level less than 100 mg/dL. Altogether, only 19% of the study cohort achieved all 3 therapy targets. Documented limitations of lifestyle counseling and drug therapy include behavior maladaptation, limitations in drug potency, nonadherence to medications, adverse effects, and economic deterrents.7

METABOLIC SURGERY FOR TYPE 2 DM

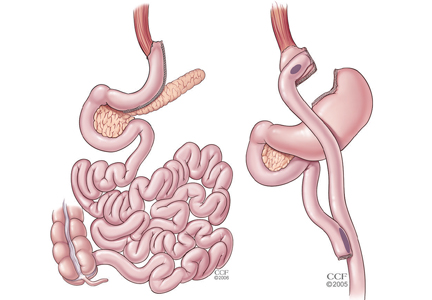

For patients with obesity and type 2 DM in whom lifestyle management and medications do not achieve desired treatment goals, bariatric surgery has emerged as the most effective treatment for attaining significant and durable weight loss. These gastrointestinal (GI) procedures, which reduce gastric volume with or without rerouting nutrient flow through the small intestine, were developed to yield long-term weight loss in patients with severe obesity. It is now known that they also cause dramatic improvement or remission of obesity-related comorbidities, especially type 2 DM. Research has shown that these effects are not only secondary to weight loss but also depend on neuroendocrine mechanisms secondary to changes in GI physiology. For these reasons, bariatric surgery is increasingly used with the primary intent to treat type 2 DM or metabolic disease, a practice referred to as metabolic surgery.

For more than 2 decades, indications for metabolic surgery reflected guidelines from a 1991 National Institutes of Health (NIH) consensus conference, which suggested considering surgery only in patients with a BMI of 40 kg/m2 or greater or a BMI of 35 kg/m2 or greater and significant obesity-related comorbidities.11 Guidelines published in 2013 expanded the recommendations to include adults with a BMI of at least 35 kg/m2 and an obesity-related comorbidity, such as diabetes, who are motivated to lose weight.4 These recommendations were primarily designed to guide the use of surgery as a weight-loss intervention for severe obesity. However, guidelines published in 2016 support use of metabolic surgery as a specific treatment for type 2 DM.5

Potential mechanisms resolving type 2 DM: More than weight loss

Bariatric surgery has been shown to have profound glucoregulatory effects. These include rapid improvement in hyperglycemia and reduction in exogenous insulin requirements that occur early after surgery and before the patient has any significant weight loss.12,13 Additionally, experiments in rodents showed that changes to GI anatomy can directly influence glucose homeostasis, independently of weight loss and caloric restriction.14

Although the exact molecular mechanisms underlying the effects of metabolic surgery on diabetes are not fully understood, many factors appear to play a role, including changes in bile acid metabolism, GI tract nutrient sensing, glucose utilization, insulin resistance, and intestinal microbiomes.15 These changes, acting through peripheral or central pathways, or perhaps both, lead to reduced hepatic glucose production, increased tissue glucose uptake, improved insulin sensitivity, and enhanced beta-cell function. A constellation of gut-derived neuroendocrine changes, rather than a single overarching mechanism, is the likely mediator of postoperative glycemic improvement, with the contributing factors varying according to the surgical procedure.

METABOLIC SURGERY OUTCOMES

Weight loss

Long-term reduction of excess body fat is a major goal of metabolic and bariatric surgery. Weight loss is usually expressed as either the percent of weight loss or the percent of excess weight loss (ie, weight loss above ideal weight). A meta-analysis of mostly short-term weight-loss outcomes (ie, < 5 years) from more than 22,000 procedures found an overall mean excess weight loss of 47.5% for patients who underwent LAGB, 61.6% for RYGB, 68.2% for vertical-banded gastroplasty, and 70.1% for BPD-DS.16 Vertical-banded gastroplasty differs from LAGB in that both a band and staples are used to create a small stomach pouch. Excess weight loss for SG generally averages 50% to 55%, which is intermediate between LAGB and RYGB.17,18

The Swedish Obese Subjects study (N = 4,047), a prospective study of bariatric surgery vs nonsurgical weight management of severely obese patients (BMI > 34), is the largest weight-loss study with the longest follow-up.19 At 20 years, the mean weight loss was 26% for gastric bypass, 18% for vertical-banded gastroplasty, 13% for gastric banding, and 1% for controls. A 10-year study in 1,787 severely obese patients (BMI ≥ 35) who underwent RYGB had 21% more weight loss from their baseline weight than the nonsurgical match.20 At 4-year follow-up in 2,410 patients, there were significant variations in weight loss depending on the procedure: 27.5% for RYGB, 17.8% for SG, and 10.6% in LAGB. Between 2% and 31% regained weight back to baseline: 30.5% for LAGB, 14.6% for SG, and 2.5% for RYGB.20 In contrast, long-term medical (nonsurgical) weight loss rarely exceeds 5%, even with intensive lifestyle intervention.21

Diabetes remission, cardiovascular risk factors, glycemic control

A meta-analysis of 19 mostly observational studies (N = 4,070 patients) reported an overall type 2 DM remission rate of 78% after bariatric surgery with 1 to 3 years of follow-up.22 Resolution or remission was typically defined as becoming “nondiabetic” with normal HbA1c without medications. In the Swedish Obese Subjects study, the remission rate was 72% at 2 years and 36% at 10 years compared with 21% and 13%, respectively, for the nonsurgical controls (P < .001).23 Bariatric surgery was also markedly more effective than nonsurgical treatment in preventing type 2 DM, with a relative risk reduction of 78%.

A systematic review published in 2012 evaluated long-term cardiovascular risk reduction after bariatric surgery in 73 studies and 19,543 patients.24 At a mean follow-up of 57.8 months, the average excess weight loss for all procedures was 54% and rates of remission or improvement were 63% for hypertension, 73% for type 2 DM, and 65% for hyperlipidemia. Results from 12 cohort-matched, nonrandomized studies comparing bariatric surgery vs nonsurgical controls suggest that improvements in surrogate disease markers such as HbA1c, blood pressure, lipids, and body weight after surgery translate to reduced macrovascular and microvascular events and death.25 One of these studies involving male veterans who were mostly at high cardiovascular risk reported a 42% reduction in mortality at 10 years compared with medical therapy.26

In the Swedish Obese Subjects study, the mortality rate from cardiovascular disease in the bariatric surgical group was lower than for control patients (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.47; P = .002) despite a greater prevalence of smoking and higher baseline weights and blood pressures in the surgical cohort.19 For patients with type 2 DM in this study, surgery was associated with a 50% reduction in microvascular complications.27 After 15 years of follow-up, the cumulative incidence of microvascular complications was 41.8 per 1,000 person-years for control patients and 20.6 per 1,000 person-years in the surgery group (hazard ratio, 0.44; P < .001).

These observational, nonrandomized study data suggest that in patients with type 2 DM, bariatric surgery is significantly better than medical management alone in improving glycemic control, reducing cardiovascular risk factors, and lowering long-term morbidity and mortality associated with type 2 DM.

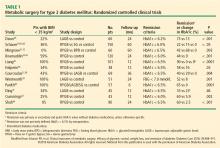

METABOLIC SURGERY: CLINICAL TRIALS

Collectively, these RCTs showed that surgery was significantly superior to medical treatment in reaching the designated glycemic target (P < .05 for all). The one exception showed that diabetes remission for LAGB vs medical treatment was 33% and 23%, respectively.41 This result might be due to patients in this study having advanced type 2 DM (HbA1c 8.2% ± 1.2%, with 40% on insulin), and they likely had reduced beta-cell function. Overall, surgery decreased HbA1c by 2% to 3.5%, whereas medical treatment lowered it by only 1% to 1.5%. Most of these studies also showed superiority of surgery over medical treatment in achieving secondary end points such as weight loss, remission of metabolic syndrome, reduction in diabetes and cardiovascular medications, and improvement in triglycerides, lipids, and quality of life. Results were mixed in terms of improvements in systolic and diastolic blood pressure or low-density lipoproteins after surgery vs medical treatment, but many studies did show a corresponding reduction in medication usage.

Durability of the effects of surgery was demonstrated in a 5-year study that showed superior and durable weight loss and glycemic control (remission) with both RYGB and BPD in severely obese patients (BMI ≥ 35) vs medical therapy.32 Similarly, Schauer et al43 showed that RYGB and SG were more effective than intensive medical therapy in improving or, in some cases, resolving hyperglycemia for 5 years. In the RCTs, patients who preoperatively had shorter duration of diabetes, lower HbA1c levels, no insulin requirement, and more postoperative weight loss were more likely to achieve diabetes remission.

Although previous guidelines and payer coverage policies had limited metabolic surgery to severely obese patients (BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2), nearly all RCTs showed that the surgical procedures, especially RYGB and SG, were equally effective in patients with BMI 30 to 35 kg/m2. This is particularly important given that most patients with type 2 DM have a BMI less than 35 kg/m2. The effect of surgery in these patients with mild obesity is also durable out to at least 5 years.43

No RCT was sufficiently powered to detect differences in macrovascular or microvascular complications or death, especially at the relatively short follow-up, and no such differences have been detected thus far. The STAMPEDE (Surgical Therapy and Medications Potentially Eradicate Diabetes Efficiently) trial43 showed that bariatric surgery (RYGB or SG) did not appear to worsen or improve retinopathy outcomes at 5 years compared with intensive medical management.

METABOLIC SURGERY: ADVERSE EVENTS

Surgical complications

Nutritional deficiencies

Postoperative nutritional deficiencies are typically associated with diminished nutrient intake or the malabsorptive effect of bariatric procedures. They are more common after RYGB and BPD-DS and less common after SG and LAGB. In addition, there is a high prevalence of nutritional deficiencies (35%–80%) in patients seeking bariatric surgery; thus, poor preoperative nutrition may be a factor in the development of postoperative deficiencies. Common preoperative nutrient deficiencies are vitamin A (11%), vitamin B12 (13%), vitamin D (40%), zinc (30%), iron (16%), ferritin (9%), selenium (58%), and folate (6%).51 Recommendations are to assess for these deficiencies and correct any identified before surgery.

Mild anemia after bariatric procedures is common, occurring in 15% to 20% of cases, and it is believed to result from reduced absorption of iron and B12, as well from pre-existing iron deficiency anemia in premenopausal patients.52 Deficiencies in trace minerals (selenium, zinc, and copper) and vitamins (B12, B1, A, E, D, and K) can occur after bariatric procedures, especially after BPD-DS.53 Nutrient deficiencies can be prevented or corrected with appropriate vitamin, iron, and calcium supplementation.54

Bone mineral density may decrease after bariatric surgery (14% in the proximal femur).55 Reduced mechanical loading after weight loss, reduced consumption and malabsorption of micronutrients (calcium, vitamin D), and neurohormonal alterations are potential underlying mechanisms of bone mineral density reduction after bariatric surgery. Rates of bone fracture and osteoporosis are not well delineated, raising questions about whether bone loss after bariatric surgery is clinically relevant or a functional adaptation to skeletal unloading. However, the extreme malabsorptive procedures of BPD-DS have been associated with severe calcium and vitamin D deficiencies, leading to decreased bone mineral density and osteoporosis.

Protein malnutrition also can occur after these extreme malabsorptive procedures. Patients require postoperative oral protein supplementation (80–100 g/day) and lifelong monitoring for nutritional complications after these procedures.56

Additional complications

Other late complications of bariatric surgery that are less clear in incidence and cause include kidney stones, alcohol abuse, depression, and suicide. One study of patients after RYGB (N = 4,690) reported a significantly higher prevalence of kidney stones than in obese controls: 7.5% vs 4.6%, respectively.57 Proposed causes of kidney stone formation following bariatric surgery include hyperoxaluria, hypocitraturia, and elevated urine acidity.58

The prevalence of alcohol-use disorder after bariatric surgery ranges from 7.6% to 11.8% and appears to be higher in patients with a history of alcohol use.59 Paradoxically, while bariatric surgery has been shown to significantly decrease depression,60 some studies suggest that a slight increase in the risk of suicide may occur,61 while others do not.62 A recent review concluded that accurate rates of suicide after bariatric surgery are not known, but practitioners should be aware of this concern and appropriately screen and counsel their patients.63

Although the 12 RCTs reported in Table 1 were not powered to detect differences in treatment-related complications, the overall rates of complications were consistent with those in observational studies.9 The most common surgical complications were anemia (15%), need for reoperation (8%), and GI (5%–10%). The 30-day surgical mortality rate was 0.2% (1 death) among the 465 surgical patients. Complications were not limited to the surgical patients. In the medical-treatment control group of the STAMPEDE trial,30 anemia (16%) and weight gain (16%) were common. Investigators reported challenges with medication compliance, including adverse effects leading to discontinuation of medications. Mild hypoglycemia was common, with no significant differences between the surgical and medical treatment groups.

METABOLIC SURGERY: COST EFFECTIVENESS

The cost of bariatric procedures varies considerably but, in general, ranges from $20,000 to $30,000, similar to the cost of cholecystectomy, hysterectomy, and colectomy. Retrospective analyses and modeling studies indicate that metabolic surgery is cost-effective and may present a cost savings in patients with type 2 DM, with a break-even time between 5 and 10 years.64,65 The cost savings, largely based on assumptions of long-term effectiveness and safety, result from reductions in medication use, outpatient care costs, and long-term complications of type 2 DM.

WHO SHOULD HAVE METABOLIC SURGERY?

Until recently, there was no clear national or international consensus on the role of metabolic surgery in treating type 2 DM. In 2015, the 2nd Diabetes Surgery Summit (DSS-II) Consensus Conference published guidelines that were endorsed by more than 50 diabetes and medical organizations.5 The recommendations cover many clinically relevant issues, including patient selection, preoperative evaluation, choice of procedure, and postoperative follow-up. The consensus conference delegates concluded that there is sufficient evidence demonstrating that metabolic surgery achieves excellent glycemic control and reduces cardiovascular risk factors.

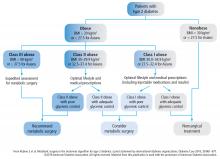

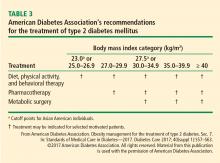

The treatment algorithm from DSS-II incorporates appropriate use of all 3 treatment modalities: lifestyle intervention, drug therapy, and surgery (Figure 5).5 The 2017 Standards of Care for Diabetes from the American Diabetes Association include those key indications in the recommendations for metabolic surgery (Table 3).2

SUMMARY

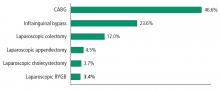

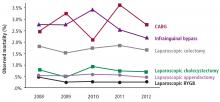

The safety of metabolic surgery has significantly improved with the advent of laparoscopic surgery and recent national quality improvement initiatives that have made gastric bypass and SG as safe as cholecystectomy and appendectomy. Although observational studies suggest that metabolic surgery is associated with a reduction in cardiovascular and diabetes complications and mortality, these observations have not been confirmed in long-term RCTs.

Based on the published evidence, metabolic surgery is now endorsed as a standard treatment option, which provides patients and practitioners with a powerful tool to help combat the life-impairing effects of type 2 DM.

- Bays HE, Chapman RH, Grandy S; for the SHIELD Investigators Group. The relationship of body mass index to diabetes mellitus, hypertension and dyslipidaemia: comparison of data from two national surveys. Int J Clin Pract May 2007; 61:737–747.

- Marathe PH, Gao HX, Close KL. American Diabetes Association standards of medical care in diabetes—2017. Diabetes Care 2017; 40(suppl 1):S1–S135.

- Fox CS, Golden SH, Anderson C, et al; American Heart Association; American Diabetes Association. Update on prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus in light of recent evidence: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American Diabetes Association. Circulation 2015; 132:691–718.

- Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; Obesity Society. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 63:2985–3023.

- Rubino F, Nathan DM, Eckel RH, et al; Delegates of the 2nd Diabetes Surgery Summit. Metabolic surgery in the treatment algorithm for type 2 diabetes: a joint statement by international diabetes organizations. Diabetes Care 2016; 39:861–877.

- Stark Casagrande S, Fradkin JE, Saydah SH, Rust KF, Cowie CC. The prevalence of meeting A1C, blood pressure, and LDL goals among people with diabetes, 1988–2010. Diabetes Care 2013; 36:2271–2279.

- Kolandaivelu K, Leiden BB, O’Gara PT, Bhatt DL. Non-adherence to cardiovascular medications. Eur Heart J 2014; 35:3267–3276.

- Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P, Formisano G, Buchwald H, Scopinaro N. Bariatric surgery worldwide 2013. Obes Surg 2015; 25:1822–1832.

- Schauer PR, Mingrone G, Ikramuddin S, Wolfe B. Clinical outcomes of metabolic surgery: efficacy of glycemic control, weight loss, and remission of diabetes. Diabetes Care 2016; 39:902–911.

- Khorgami Z, Andalib A, Corcelles R, Aminian A, Brethauer S, Schauer P. Recent national trends in the surgical treatment of obesity: sleeve gastrectomy dominates. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2015; 11(suppl):S1–S34 [Abstract A111].

- Consensus Development Conference Panel. NIH conference. Gastrointestinal surgery for severe obesity. Ann Intern Med 1991; 115:956–961.

- Pories WJ, MacDonald KG Jr, Flickinger EG, et al. Is type II diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) a surgical disease? Ann Surg 1992; 215:633–642.

- Schauer PR, Burguera B, Ikramuddin S, et al. Effect of laparoscopic Roux-en Y gastric bypass on type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Surg 2003; 238:467–484.

- Rubino F, Marescaux J. Effect of duodenal-jejunal exclusion in a non-obese animal model of type 2 diabetes: a new perspective for an old disease. Ann Surg 2004; 239:1–11.

- Batterham RL, Cummings DE. Mechanisms of diabetes improvement following bariatric/metabolic surgery. Diabetes Care 2016; 39:893–901.

- Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2004; 292:1724–1737.

- Brethauer SA, Hammel JP, Schauer PR. Systematic review of sleeve gastrectomy as staging and primary bariatric procedure. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2009; 5:469–475.

- Eid GM, Brethauer S, Mattar SG, Titchner RL, Gourash W, Schauer PR. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for super obese patients: forty-eight percent excess weight loss after 6 to 8 years with 93% follow-up. Ann Surg 2012; 256:262–265.

- Sjöström L, Peltonen M, Jacobson P, et al. Bariatric surgery and long-term cardiovascular events. JAMA 2012; 307:56–65.

- Maciejewski ML, Arterburn DE, Van Scoyoc L, et al. Bariatric surgery and long-term durability of weight loss. JAMA Surg 2016; 151:1046–1055.

- Wing RR, Bolin P, Brancati FL, et al; for the Look AHEAD Research Group. Cardiovascular effects of intensive lifestyle intervention in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2013; 369:145–154.

- Buchwald H, Estok R, Fahrbach K, et al. Weight and type 2 diabetes after bariatric surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Med 2009; 122:248–256.

- Sjöström L, Lindroos AK, Peltonen M, et al; Swedish Obese Subjects Study Scientific Group. Lifestyle, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors 10 years after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med 2004; 351:2683–2693.

- Vest AR, Heneghan HM, Agarwal S, Schauer PR, Young JB. Bariatric surgery and cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review. Heart 2012; 98:1763–1777.

- Vest AR, Heneghan HM, Schauer PR, Young JB. Surgical management of obesity and the relationship to cardiovascular disease. Circulation 2013; 127:945–959.

- Arterburn DE, Olsen MK, Smith VA, et al. Association between bariatric surgery and long-term survival. JAMA 2015; 313:62–70.

- Sjöström L, Peltonen M, Jacobson P, et al. Association of bariatric surgery with long-term remission of type 2 diabetes and with microvascular and macrovascular complications. JAMA 2014; 311:2297–2304.

- Dixon JB, O’Brien PE, Playfair J, et al. Adjustable gastric banding and conventional therapy for type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2008; 299:316–323.

- Schauer PR, Kashyap SR, Wolski K, et al. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy in obese patients with diabetes. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:1567–1576.

- Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, et al; STAMPEDE Investigators. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes—3-year outcomes. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:2002–2013.

- Mingrone G, Panunzi S, De Gaetano A, et al. Bariatric surgery versus conventional medical therapy for type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:1577–1585.

- Mingrone G, Panunzi S, De Gaetano A, et al. Bariatric-metabolic surgery versus conventional medical treatment in obese patients with type 2 diabetes: 5 year follow-up of an open-label, single-centre, randomized controlled trial. Lancet 2015; 386:964–973.

- Ikramuddin S, Korner J, Lee WJ, et al. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass vs intensive medical management for the control of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia: the Diabetes Surgery Study randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2013; 309:2240–2249.

- Ikramuddin S, Billington CJ, Lee WJ, et al. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for diabetes (the Diabetes Surgery Study): 2-year outcomes of a 5-year, randomized, controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2015; 3:413–422.

- Liang Z, Wu Q, Chen B, Yu P, Zhao H, Ouyang X. Effect of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery on type 2 diabetes mellitus with hypertension: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2013; 101:50–56.

- Halperin F, Ding SA, Simonson DC, et al. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery or lifestyle with intensive medical management in patients with type 2 diabetes: feasibility and 1-year results of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg 2014; 149:716–726.

- Courcoulas AP, Goodpaster BH, Eagleton JK, et al. Surgical vs medical treatments for type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg 2014; 149:707–715.

- Courcoulas AP, Belle SH, Neiberg RH, et al. Three-year outcomes of bariatric surgery vs. lifestyle intervention for type 2 diabetes mellitus treatment: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg 2015; 150:931–940.

- Wentworth JM, Playfair J, Laurie C, et al. Multidisciplinary diabetes care with and without bariatric surgery in overweight people: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014; 2:545–552.

- Parikh M, Chung M, Sheth S, et al. Randomized pilot trial of bariatric surgery versus intensive medical weight management on diabetes remission in type 2 diabetic patients who do not meet NIH criteria for surgery and the role of soluble RAGE as a novel biomarker of success. Ann Surg 2014; 260:617–622.

- Ding SA, Simonson DC, Wewalka M, et al. Adjustable gastric band surgery or medical management in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015; 100:2546–2556.

- Cummings DE, Arterburn DE, Westbrook EO, et al. Gastric bypass surgery vs. intensive lifestyle and medical intervention for type 2 diabetes: the CROSSROADS randomized controlled trial. Diabetologia 2016; 59:945–953.

- Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, et al; STAMPEDE Investigators. Metabolic surgery vs. intensive medical therapy for diabetes: 5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med 2017; 376:641–651.

- Shah SS, Todkar J, Phadake U, et al. Gastric bypass vs. medical/lifestyle care for type 2 diabetes in South Asians with BMI 25-40 kg/m2: the COSMID randomized trial [261-OR]. Presented at the American Diabetes Association’s 76th Scientific Session; June 10–14, 2016; New Orleans, LA.

- Flum DR, Belle SH, King WC, et al; Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS) Consortium. Perioperative safety in the longitudinal assessment of bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:445–454.

- Aminian A, Brethauer SA, Kirwan JP, Kashyap SR, Burguera B, Schauer PR. How safe is metabolic/diabetes surgery? Diabetes Obes Metab 2015; 17:198–201.

- Thodiyil PA, Yenumula P, Rogula T, et al. Selective non operative management of leaks after gastric bypass: lessons learned from 2675 consecutive patients. Ann Surg 2008; 248:782–792.

- Rogula T, Yenumula PR, Schauer PR. A complication of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: intestinal obstruction. Surg Endosc 2007; 21:1914–1918.

- Thornton CM, Rozen WM, So D, Kaplan ED, Wilkinson S. Reducing band slippage in laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding: the mesh plication pars flaccida technique. Obes Surg 2009; 19:1702–1706.

- Himpens J, Cadière G-B, Bazi M, Vouche M, Cadière B, Dapri G. Long-term outcomes of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Arch Surg 2011; 146:802–807.

- Madan AK, Orth WS, Tichansky DS, Ternovits CA. Vitamin and trace mineral levels after laparoscopic gastric bypass. Obes Surg 2006; 16:603–606.

- Love AL, Billett HH. Obesity, bariatric surgery, and iron deficiency: true, true, true and related. Am J Hematol 2008; 83:403–409.

- Shankar P, Boylan M, Sriram K. Micronutrient deficiencies after bariatric surgery. Nutrition 2010; 26:1031–1037.

- Gong K, Gagner M, Pomp A, Almahmeed T, Bardaro SJ. Micronutrient deficiencies after laparoscopic gastric bypass: recommendations. Obes Surg 2008; 18:1062–1066.

- Scibora LM. Skeletal effects of bariatric surgery: examining bone loss, potential mechanisms and clinical relevance. Diabetes Obes Metab 2014; 16:1204–1213.

- Baptista V, Wassef W. Bariatric procedures: an update on techniques, outcomes and complications. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2013; 29:684–693.

- Matlaga BR, Shore AD, Magnuson T, Clark JM, Johns R, Makary MA. Effect of gastric bypass surgery on kidney stone disease. J Urol 2009; 181:2573–2577.

- Sakhaee K, Poindexter J, Aguirre C. The effects of bariatric surgery on bone and nephrolithiasis. Bone 2016; 84:1–8.

- Li L, Wu LT. Substance use after bariatric surgery: a review. J Psychiatr Res 2016; 76:16–29.

- Ayloo S, Thompson K, Choudhury N, Sheriffdeen R. Correlation between the Beck Depression Inventory and bariatric surgical procedures. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2015; 11:637–342.

- Adams TD, Gress RE, Smith SC, et al. Long-term mortality after gastric bypass surgery. N Engl J Med 2007; 357:753–761.

- Sjöström L, Narbro K, Sjöström CD, et al; Swedish Obese Subjects Study. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med 2007; 357:741–752.

- Mitchell JE, Crosby R, de Zwaan M, et al. Possible risk factors for increased suicide following bariatric surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013; 21:665–672.

- Fouse T, Schauer P. The socioeconomic impact of morbid obesity and factors affecting access to obesity surgery. Surg Clin North Am 2016; 96:669–679.

- Rubin JK, Hinrichs-Krapels S, Hesketh R, Martin A, Herman WH, Rubino F. Identifying barriers to appropriate use of metabolic/bariatric surgery for type 2 diabetes treatment: policy lab results. Diabetes Care 2016; 39:954–963.

LIMITATIONS OF LIFESTYLE MANAGEMENT AND MEDICATIONS

First-line therapy with lifestyle management and second-line therapy with medications, including oral agents and insulin, are the mainstays of type 2 DM therapy. Although these approaches have reduced hyperglycemia and cardiovascular mortality, many patients have poor glycemic control and develop severe diabetes-related complications. A study using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (N = 4,926) to evaluate success rates of lifestyle management plus drug therapy found that just 53% of patients with type 2 DM maintained a hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) below 7%.6 Similarly, only 51% of those patients achieved a systolic and diastolic blood pressure less than 130/80 mm Hg, and only 56% achieved a low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level less than 100 mg/dL. Altogether, only 19% of the study cohort achieved all 3 therapy targets. Documented limitations of lifestyle counseling and drug therapy include behavior maladaptation, limitations in drug potency, nonadherence to medications, adverse effects, and economic deterrents.7

METABOLIC SURGERY FOR TYPE 2 DM

For patients with obesity and type 2 DM in whom lifestyle management and medications do not achieve desired treatment goals, bariatric surgery has emerged as the most effective treatment for attaining significant and durable weight loss. These gastrointestinal (GI) procedures, which reduce gastric volume with or without rerouting nutrient flow through the small intestine, were developed to yield long-term weight loss in patients with severe obesity. It is now known that they also cause dramatic improvement or remission of obesity-related comorbidities, especially type 2 DM. Research has shown that these effects are not only secondary to weight loss but also depend on neuroendocrine mechanisms secondary to changes in GI physiology. For these reasons, bariatric surgery is increasingly used with the primary intent to treat type 2 DM or metabolic disease, a practice referred to as metabolic surgery.

For more than 2 decades, indications for metabolic surgery reflected guidelines from a 1991 National Institutes of Health (NIH) consensus conference, which suggested considering surgery only in patients with a BMI of 40 kg/m2 or greater or a BMI of 35 kg/m2 or greater and significant obesity-related comorbidities.11 Guidelines published in 2013 expanded the recommendations to include adults with a BMI of at least 35 kg/m2 and an obesity-related comorbidity, such as diabetes, who are motivated to lose weight.4 These recommendations were primarily designed to guide the use of surgery as a weight-loss intervention for severe obesity. However, guidelines published in 2016 support use of metabolic surgery as a specific treatment for type 2 DM.5

Potential mechanisms resolving type 2 DM: More than weight loss

Bariatric surgery has been shown to have profound glucoregulatory effects. These include rapid improvement in hyperglycemia and reduction in exogenous insulin requirements that occur early after surgery and before the patient has any significant weight loss.12,13 Additionally, experiments in rodents showed that changes to GI anatomy can directly influence glucose homeostasis, independently of weight loss and caloric restriction.14

Although the exact molecular mechanisms underlying the effects of metabolic surgery on diabetes are not fully understood, many factors appear to play a role, including changes in bile acid metabolism, GI tract nutrient sensing, glucose utilization, insulin resistance, and intestinal microbiomes.15 These changes, acting through peripheral or central pathways, or perhaps both, lead to reduced hepatic glucose production, increased tissue glucose uptake, improved insulin sensitivity, and enhanced beta-cell function. A constellation of gut-derived neuroendocrine changes, rather than a single overarching mechanism, is the likely mediator of postoperative glycemic improvement, with the contributing factors varying according to the surgical procedure.

METABOLIC SURGERY OUTCOMES

Weight loss

Long-term reduction of excess body fat is a major goal of metabolic and bariatric surgery. Weight loss is usually expressed as either the percent of weight loss or the percent of excess weight loss (ie, weight loss above ideal weight). A meta-analysis of mostly short-term weight-loss outcomes (ie, < 5 years) from more than 22,000 procedures found an overall mean excess weight loss of 47.5% for patients who underwent LAGB, 61.6% for RYGB, 68.2% for vertical-banded gastroplasty, and 70.1% for BPD-DS.16 Vertical-banded gastroplasty differs from LAGB in that both a band and staples are used to create a small stomach pouch. Excess weight loss for SG generally averages 50% to 55%, which is intermediate between LAGB and RYGB.17,18

The Swedish Obese Subjects study (N = 4,047), a prospective study of bariatric surgery vs nonsurgical weight management of severely obese patients (BMI > 34), is the largest weight-loss study with the longest follow-up.19 At 20 years, the mean weight loss was 26% for gastric bypass, 18% for vertical-banded gastroplasty, 13% for gastric banding, and 1% for controls. A 10-year study in 1,787 severely obese patients (BMI ≥ 35) who underwent RYGB had 21% more weight loss from their baseline weight than the nonsurgical match.20 At 4-year follow-up in 2,410 patients, there were significant variations in weight loss depending on the procedure: 27.5% for RYGB, 17.8% for SG, and 10.6% in LAGB. Between 2% and 31% regained weight back to baseline: 30.5% for LAGB, 14.6% for SG, and 2.5% for RYGB.20 In contrast, long-term medical (nonsurgical) weight loss rarely exceeds 5%, even with intensive lifestyle intervention.21

Diabetes remission, cardiovascular risk factors, glycemic control

A meta-analysis of 19 mostly observational studies (N = 4,070 patients) reported an overall type 2 DM remission rate of 78% after bariatric surgery with 1 to 3 years of follow-up.22 Resolution or remission was typically defined as becoming “nondiabetic” with normal HbA1c without medications. In the Swedish Obese Subjects study, the remission rate was 72% at 2 years and 36% at 10 years compared with 21% and 13%, respectively, for the nonsurgical controls (P < .001).23 Bariatric surgery was also markedly more effective than nonsurgical treatment in preventing type 2 DM, with a relative risk reduction of 78%.

A systematic review published in 2012 evaluated long-term cardiovascular risk reduction after bariatric surgery in 73 studies and 19,543 patients.24 At a mean follow-up of 57.8 months, the average excess weight loss for all procedures was 54% and rates of remission or improvement were 63% for hypertension, 73% for type 2 DM, and 65% for hyperlipidemia. Results from 12 cohort-matched, nonrandomized studies comparing bariatric surgery vs nonsurgical controls suggest that improvements in surrogate disease markers such as HbA1c, blood pressure, lipids, and body weight after surgery translate to reduced macrovascular and microvascular events and death.25 One of these studies involving male veterans who were mostly at high cardiovascular risk reported a 42% reduction in mortality at 10 years compared with medical therapy.26

In the Swedish Obese Subjects study, the mortality rate from cardiovascular disease in the bariatric surgical group was lower than for control patients (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.47; P = .002) despite a greater prevalence of smoking and higher baseline weights and blood pressures in the surgical cohort.19 For patients with type 2 DM in this study, surgery was associated with a 50% reduction in microvascular complications.27 After 15 years of follow-up, the cumulative incidence of microvascular complications was 41.8 per 1,000 person-years for control patients and 20.6 per 1,000 person-years in the surgery group (hazard ratio, 0.44; P < .001).

These observational, nonrandomized study data suggest that in patients with type 2 DM, bariatric surgery is significantly better than medical management alone in improving glycemic control, reducing cardiovascular risk factors, and lowering long-term morbidity and mortality associated with type 2 DM.

METABOLIC SURGERY: CLINICAL TRIALS

Collectively, these RCTs showed that surgery was significantly superior to medical treatment in reaching the designated glycemic target (P < .05 for all). The one exception showed that diabetes remission for LAGB vs medical treatment was 33% and 23%, respectively.41 This result might be due to patients in this study having advanced type 2 DM (HbA1c 8.2% ± 1.2%, with 40% on insulin), and they likely had reduced beta-cell function. Overall, surgery decreased HbA1c by 2% to 3.5%, whereas medical treatment lowered it by only 1% to 1.5%. Most of these studies also showed superiority of surgery over medical treatment in achieving secondary end points such as weight loss, remission of metabolic syndrome, reduction in diabetes and cardiovascular medications, and improvement in triglycerides, lipids, and quality of life. Results were mixed in terms of improvements in systolic and diastolic blood pressure or low-density lipoproteins after surgery vs medical treatment, but many studies did show a corresponding reduction in medication usage.

Durability of the effects of surgery was demonstrated in a 5-year study that showed superior and durable weight loss and glycemic control (remission) with both RYGB and BPD in severely obese patients (BMI ≥ 35) vs medical therapy.32 Similarly, Schauer et al43 showed that RYGB and SG were more effective than intensive medical therapy in improving or, in some cases, resolving hyperglycemia for 5 years. In the RCTs, patients who preoperatively had shorter duration of diabetes, lower HbA1c levels, no insulin requirement, and more postoperative weight loss were more likely to achieve diabetes remission.

Although previous guidelines and payer coverage policies had limited metabolic surgery to severely obese patients (BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2), nearly all RCTs showed that the surgical procedures, especially RYGB and SG, were equally effective in patients with BMI 30 to 35 kg/m2. This is particularly important given that most patients with type 2 DM have a BMI less than 35 kg/m2. The effect of surgery in these patients with mild obesity is also durable out to at least 5 years.43

No RCT was sufficiently powered to detect differences in macrovascular or microvascular complications or death, especially at the relatively short follow-up, and no such differences have been detected thus far. The STAMPEDE (Surgical Therapy and Medications Potentially Eradicate Diabetes Efficiently) trial43 showed that bariatric surgery (RYGB or SG) did not appear to worsen or improve retinopathy outcomes at 5 years compared with intensive medical management.

METABOLIC SURGERY: ADVERSE EVENTS

Surgical complications

Nutritional deficiencies

Postoperative nutritional deficiencies are typically associated with diminished nutrient intake or the malabsorptive effect of bariatric procedures. They are more common after RYGB and BPD-DS and less common after SG and LAGB. In addition, there is a high prevalence of nutritional deficiencies (35%–80%) in patients seeking bariatric surgery; thus, poor preoperative nutrition may be a factor in the development of postoperative deficiencies. Common preoperative nutrient deficiencies are vitamin A (11%), vitamin B12 (13%), vitamin D (40%), zinc (30%), iron (16%), ferritin (9%), selenium (58%), and folate (6%).51 Recommendations are to assess for these deficiencies and correct any identified before surgery.

Mild anemia after bariatric procedures is common, occurring in 15% to 20% of cases, and it is believed to result from reduced absorption of iron and B12, as well from pre-existing iron deficiency anemia in premenopausal patients.52 Deficiencies in trace minerals (selenium, zinc, and copper) and vitamins (B12, B1, A, E, D, and K) can occur after bariatric procedures, especially after BPD-DS.53 Nutrient deficiencies can be prevented or corrected with appropriate vitamin, iron, and calcium supplementation.54

Bone mineral density may decrease after bariatric surgery (14% in the proximal femur).55 Reduced mechanical loading after weight loss, reduced consumption and malabsorption of micronutrients (calcium, vitamin D), and neurohormonal alterations are potential underlying mechanisms of bone mineral density reduction after bariatric surgery. Rates of bone fracture and osteoporosis are not well delineated, raising questions about whether bone loss after bariatric surgery is clinically relevant or a functional adaptation to skeletal unloading. However, the extreme malabsorptive procedures of BPD-DS have been associated with severe calcium and vitamin D deficiencies, leading to decreased bone mineral density and osteoporosis.

Protein malnutrition also can occur after these extreme malabsorptive procedures. Patients require postoperative oral protein supplementation (80–100 g/day) and lifelong monitoring for nutritional complications after these procedures.56

Additional complications

Other late complications of bariatric surgery that are less clear in incidence and cause include kidney stones, alcohol abuse, depression, and suicide. One study of patients after RYGB (N = 4,690) reported a significantly higher prevalence of kidney stones than in obese controls: 7.5% vs 4.6%, respectively.57 Proposed causes of kidney stone formation following bariatric surgery include hyperoxaluria, hypocitraturia, and elevated urine acidity.58

The prevalence of alcohol-use disorder after bariatric surgery ranges from 7.6% to 11.8% and appears to be higher in patients with a history of alcohol use.59 Paradoxically, while bariatric surgery has been shown to significantly decrease depression,60 some studies suggest that a slight increase in the risk of suicide may occur,61 while others do not.62 A recent review concluded that accurate rates of suicide after bariatric surgery are not known, but practitioners should be aware of this concern and appropriately screen and counsel their patients.63

Although the 12 RCTs reported in Table 1 were not powered to detect differences in treatment-related complications, the overall rates of complications were consistent with those in observational studies.9 The most common surgical complications were anemia (15%), need for reoperation (8%), and GI (5%–10%). The 30-day surgical mortality rate was 0.2% (1 death) among the 465 surgical patients. Complications were not limited to the surgical patients. In the medical-treatment control group of the STAMPEDE trial,30 anemia (16%) and weight gain (16%) were common. Investigators reported challenges with medication compliance, including adverse effects leading to discontinuation of medications. Mild hypoglycemia was common, with no significant differences between the surgical and medical treatment groups.

METABOLIC SURGERY: COST EFFECTIVENESS

The cost of bariatric procedures varies considerably but, in general, ranges from $20,000 to $30,000, similar to the cost of cholecystectomy, hysterectomy, and colectomy. Retrospective analyses and modeling studies indicate that metabolic surgery is cost-effective and may present a cost savings in patients with type 2 DM, with a break-even time between 5 and 10 years.64,65 The cost savings, largely based on assumptions of long-term effectiveness and safety, result from reductions in medication use, outpatient care costs, and long-term complications of type 2 DM.

WHO SHOULD HAVE METABOLIC SURGERY?

Until recently, there was no clear national or international consensus on the role of metabolic surgery in treating type 2 DM. In 2015, the 2nd Diabetes Surgery Summit (DSS-II) Consensus Conference published guidelines that were endorsed by more than 50 diabetes and medical organizations.5 The recommendations cover many clinically relevant issues, including patient selection, preoperative evaluation, choice of procedure, and postoperative follow-up. The consensus conference delegates concluded that there is sufficient evidence demonstrating that metabolic surgery achieves excellent glycemic control and reduces cardiovascular risk factors.

The treatment algorithm from DSS-II incorporates appropriate use of all 3 treatment modalities: lifestyle intervention, drug therapy, and surgery (Figure 5).5 The 2017 Standards of Care for Diabetes from the American Diabetes Association include those key indications in the recommendations for metabolic surgery (Table 3).2

SUMMARY

The safety of metabolic surgery has significantly improved with the advent of laparoscopic surgery and recent national quality improvement initiatives that have made gastric bypass and SG as safe as cholecystectomy and appendectomy. Although observational studies suggest that metabolic surgery is associated with a reduction in cardiovascular and diabetes complications and mortality, these observations have not been confirmed in long-term RCTs.

Based on the published evidence, metabolic surgery is now endorsed as a standard treatment option, which provides patients and practitioners with a powerful tool to help combat the life-impairing effects of type 2 DM.

LIMITATIONS OF LIFESTYLE MANAGEMENT AND MEDICATIONS

First-line therapy with lifestyle management and second-line therapy with medications, including oral agents and insulin, are the mainstays of type 2 DM therapy. Although these approaches have reduced hyperglycemia and cardiovascular mortality, many patients have poor glycemic control and develop severe diabetes-related complications. A study using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (N = 4,926) to evaluate success rates of lifestyle management plus drug therapy found that just 53% of patients with type 2 DM maintained a hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) below 7%.6 Similarly, only 51% of those patients achieved a systolic and diastolic blood pressure less than 130/80 mm Hg, and only 56% achieved a low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level less than 100 mg/dL. Altogether, only 19% of the study cohort achieved all 3 therapy targets. Documented limitations of lifestyle counseling and drug therapy include behavior maladaptation, limitations in drug potency, nonadherence to medications, adverse effects, and economic deterrents.7

METABOLIC SURGERY FOR TYPE 2 DM

For patients with obesity and type 2 DM in whom lifestyle management and medications do not achieve desired treatment goals, bariatric surgery has emerged as the most effective treatment for attaining significant and durable weight loss. These gastrointestinal (GI) procedures, which reduce gastric volume with or without rerouting nutrient flow through the small intestine, were developed to yield long-term weight loss in patients with severe obesity. It is now known that they also cause dramatic improvement or remission of obesity-related comorbidities, especially type 2 DM. Research has shown that these effects are not only secondary to weight loss but also depend on neuroendocrine mechanisms secondary to changes in GI physiology. For these reasons, bariatric surgery is increasingly used with the primary intent to treat type 2 DM or metabolic disease, a practice referred to as metabolic surgery.

For more than 2 decades, indications for metabolic surgery reflected guidelines from a 1991 National Institutes of Health (NIH) consensus conference, which suggested considering surgery only in patients with a BMI of 40 kg/m2 or greater or a BMI of 35 kg/m2 or greater and significant obesity-related comorbidities.11 Guidelines published in 2013 expanded the recommendations to include adults with a BMI of at least 35 kg/m2 and an obesity-related comorbidity, such as diabetes, who are motivated to lose weight.4 These recommendations were primarily designed to guide the use of surgery as a weight-loss intervention for severe obesity. However, guidelines published in 2016 support use of metabolic surgery as a specific treatment for type 2 DM.5

Potential mechanisms resolving type 2 DM: More than weight loss

Bariatric surgery has been shown to have profound glucoregulatory effects. These include rapid improvement in hyperglycemia and reduction in exogenous insulin requirements that occur early after surgery and before the patient has any significant weight loss.12,13 Additionally, experiments in rodents showed that changes to GI anatomy can directly influence glucose homeostasis, independently of weight loss and caloric restriction.14

Although the exact molecular mechanisms underlying the effects of metabolic surgery on diabetes are not fully understood, many factors appear to play a role, including changes in bile acid metabolism, GI tract nutrient sensing, glucose utilization, insulin resistance, and intestinal microbiomes.15 These changes, acting through peripheral or central pathways, or perhaps both, lead to reduced hepatic glucose production, increased tissue glucose uptake, improved insulin sensitivity, and enhanced beta-cell function. A constellation of gut-derived neuroendocrine changes, rather than a single overarching mechanism, is the likely mediator of postoperative glycemic improvement, with the contributing factors varying according to the surgical procedure.

METABOLIC SURGERY OUTCOMES

Weight loss

Long-term reduction of excess body fat is a major goal of metabolic and bariatric surgery. Weight loss is usually expressed as either the percent of weight loss or the percent of excess weight loss (ie, weight loss above ideal weight). A meta-analysis of mostly short-term weight-loss outcomes (ie, < 5 years) from more than 22,000 procedures found an overall mean excess weight loss of 47.5% for patients who underwent LAGB, 61.6% for RYGB, 68.2% for vertical-banded gastroplasty, and 70.1% for BPD-DS.16 Vertical-banded gastroplasty differs from LAGB in that both a band and staples are used to create a small stomach pouch. Excess weight loss for SG generally averages 50% to 55%, which is intermediate between LAGB and RYGB.17,18

The Swedish Obese Subjects study (N = 4,047), a prospective study of bariatric surgery vs nonsurgical weight management of severely obese patients (BMI > 34), is the largest weight-loss study with the longest follow-up.19 At 20 years, the mean weight loss was 26% for gastric bypass, 18% for vertical-banded gastroplasty, 13% for gastric banding, and 1% for controls. A 10-year study in 1,787 severely obese patients (BMI ≥ 35) who underwent RYGB had 21% more weight loss from their baseline weight than the nonsurgical match.20 At 4-year follow-up in 2,410 patients, there were significant variations in weight loss depending on the procedure: 27.5% for RYGB, 17.8% for SG, and 10.6% in LAGB. Between 2% and 31% regained weight back to baseline: 30.5% for LAGB, 14.6% for SG, and 2.5% for RYGB.20 In contrast, long-term medical (nonsurgical) weight loss rarely exceeds 5%, even with intensive lifestyle intervention.21

Diabetes remission, cardiovascular risk factors, glycemic control

A meta-analysis of 19 mostly observational studies (N = 4,070 patients) reported an overall type 2 DM remission rate of 78% after bariatric surgery with 1 to 3 years of follow-up.22 Resolution or remission was typically defined as becoming “nondiabetic” with normal HbA1c without medications. In the Swedish Obese Subjects study, the remission rate was 72% at 2 years and 36% at 10 years compared with 21% and 13%, respectively, for the nonsurgical controls (P < .001).23 Bariatric surgery was also markedly more effective than nonsurgical treatment in preventing type 2 DM, with a relative risk reduction of 78%.

A systematic review published in 2012 evaluated long-term cardiovascular risk reduction after bariatric surgery in 73 studies and 19,543 patients.24 At a mean follow-up of 57.8 months, the average excess weight loss for all procedures was 54% and rates of remission or improvement were 63% for hypertension, 73% for type 2 DM, and 65% for hyperlipidemia. Results from 12 cohort-matched, nonrandomized studies comparing bariatric surgery vs nonsurgical controls suggest that improvements in surrogate disease markers such as HbA1c, blood pressure, lipids, and body weight after surgery translate to reduced macrovascular and microvascular events and death.25 One of these studies involving male veterans who were mostly at high cardiovascular risk reported a 42% reduction in mortality at 10 years compared with medical therapy.26

In the Swedish Obese Subjects study, the mortality rate from cardiovascular disease in the bariatric surgical group was lower than for control patients (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.47; P = .002) despite a greater prevalence of smoking and higher baseline weights and blood pressures in the surgical cohort.19 For patients with type 2 DM in this study, surgery was associated with a 50% reduction in microvascular complications.27 After 15 years of follow-up, the cumulative incidence of microvascular complications was 41.8 per 1,000 person-years for control patients and 20.6 per 1,000 person-years in the surgery group (hazard ratio, 0.44; P < .001).

These observational, nonrandomized study data suggest that in patients with type 2 DM, bariatric surgery is significantly better than medical management alone in improving glycemic control, reducing cardiovascular risk factors, and lowering long-term morbidity and mortality associated with type 2 DM.

METABOLIC SURGERY: CLINICAL TRIALS

Collectively, these RCTs showed that surgery was significantly superior to medical treatment in reaching the designated glycemic target (P < .05 for all). The one exception showed that diabetes remission for LAGB vs medical treatment was 33% and 23%, respectively.41 This result might be due to patients in this study having advanced type 2 DM (HbA1c 8.2% ± 1.2%, with 40% on insulin), and they likely had reduced beta-cell function. Overall, surgery decreased HbA1c by 2% to 3.5%, whereas medical treatment lowered it by only 1% to 1.5%. Most of these studies also showed superiority of surgery over medical treatment in achieving secondary end points such as weight loss, remission of metabolic syndrome, reduction in diabetes and cardiovascular medications, and improvement in triglycerides, lipids, and quality of life. Results were mixed in terms of improvements in systolic and diastolic blood pressure or low-density lipoproteins after surgery vs medical treatment, but many studies did show a corresponding reduction in medication usage.

Durability of the effects of surgery was demonstrated in a 5-year study that showed superior and durable weight loss and glycemic control (remission) with both RYGB and BPD in severely obese patients (BMI ≥ 35) vs medical therapy.32 Similarly, Schauer et al43 showed that RYGB and SG were more effective than intensive medical therapy in improving or, in some cases, resolving hyperglycemia for 5 years. In the RCTs, patients who preoperatively had shorter duration of diabetes, lower HbA1c levels, no insulin requirement, and more postoperative weight loss were more likely to achieve diabetes remission.

Although previous guidelines and payer coverage policies had limited metabolic surgery to severely obese patients (BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2), nearly all RCTs showed that the surgical procedures, especially RYGB and SG, were equally effective in patients with BMI 30 to 35 kg/m2. This is particularly important given that most patients with type 2 DM have a BMI less than 35 kg/m2. The effect of surgery in these patients with mild obesity is also durable out to at least 5 years.43

No RCT was sufficiently powered to detect differences in macrovascular or microvascular complications or death, especially at the relatively short follow-up, and no such differences have been detected thus far. The STAMPEDE (Surgical Therapy and Medications Potentially Eradicate Diabetes Efficiently) trial43 showed that bariatric surgery (RYGB or SG) did not appear to worsen or improve retinopathy outcomes at 5 years compared with intensive medical management.

METABOLIC SURGERY: ADVERSE EVENTS

Surgical complications

Nutritional deficiencies

Postoperative nutritional deficiencies are typically associated with diminished nutrient intake or the malabsorptive effect of bariatric procedures. They are more common after RYGB and BPD-DS and less common after SG and LAGB. In addition, there is a high prevalence of nutritional deficiencies (35%–80%) in patients seeking bariatric surgery; thus, poor preoperative nutrition may be a factor in the development of postoperative deficiencies. Common preoperative nutrient deficiencies are vitamin A (11%), vitamin B12 (13%), vitamin D (40%), zinc (30%), iron (16%), ferritin (9%), selenium (58%), and folate (6%).51 Recommendations are to assess for these deficiencies and correct any identified before surgery.

Mild anemia after bariatric procedures is common, occurring in 15% to 20% of cases, and it is believed to result from reduced absorption of iron and B12, as well from pre-existing iron deficiency anemia in premenopausal patients.52 Deficiencies in trace minerals (selenium, zinc, and copper) and vitamins (B12, B1, A, E, D, and K) can occur after bariatric procedures, especially after BPD-DS.53 Nutrient deficiencies can be prevented or corrected with appropriate vitamin, iron, and calcium supplementation.54

Bone mineral density may decrease after bariatric surgery (14% in the proximal femur).55 Reduced mechanical loading after weight loss, reduced consumption and malabsorption of micronutrients (calcium, vitamin D), and neurohormonal alterations are potential underlying mechanisms of bone mineral density reduction after bariatric surgery. Rates of bone fracture and osteoporosis are not well delineated, raising questions about whether bone loss after bariatric surgery is clinically relevant or a functional adaptation to skeletal unloading. However, the extreme malabsorptive procedures of BPD-DS have been associated with severe calcium and vitamin D deficiencies, leading to decreased bone mineral density and osteoporosis.

Protein malnutrition also can occur after these extreme malabsorptive procedures. Patients require postoperative oral protein supplementation (80–100 g/day) and lifelong monitoring for nutritional complications after these procedures.56

Additional complications

Other late complications of bariatric surgery that are less clear in incidence and cause include kidney stones, alcohol abuse, depression, and suicide. One study of patients after RYGB (N = 4,690) reported a significantly higher prevalence of kidney stones than in obese controls: 7.5% vs 4.6%, respectively.57 Proposed causes of kidney stone formation following bariatric surgery include hyperoxaluria, hypocitraturia, and elevated urine acidity.58

The prevalence of alcohol-use disorder after bariatric surgery ranges from 7.6% to 11.8% and appears to be higher in patients with a history of alcohol use.59 Paradoxically, while bariatric surgery has been shown to significantly decrease depression,60 some studies suggest that a slight increase in the risk of suicide may occur,61 while others do not.62 A recent review concluded that accurate rates of suicide after bariatric surgery are not known, but practitioners should be aware of this concern and appropriately screen and counsel their patients.63

Although the 12 RCTs reported in Table 1 were not powered to detect differences in treatment-related complications, the overall rates of complications were consistent with those in observational studies.9 The most common surgical complications were anemia (15%), need for reoperation (8%), and GI (5%–10%). The 30-day surgical mortality rate was 0.2% (1 death) among the 465 surgical patients. Complications were not limited to the surgical patients. In the medical-treatment control group of the STAMPEDE trial,30 anemia (16%) and weight gain (16%) were common. Investigators reported challenges with medication compliance, including adverse effects leading to discontinuation of medications. Mild hypoglycemia was common, with no significant differences between the surgical and medical treatment groups.

METABOLIC SURGERY: COST EFFECTIVENESS

The cost of bariatric procedures varies considerably but, in general, ranges from $20,000 to $30,000, similar to the cost of cholecystectomy, hysterectomy, and colectomy. Retrospective analyses and modeling studies indicate that metabolic surgery is cost-effective and may present a cost savings in patients with type 2 DM, with a break-even time between 5 and 10 years.64,65 The cost savings, largely based on assumptions of long-term effectiveness and safety, result from reductions in medication use, outpatient care costs, and long-term complications of type 2 DM.

WHO SHOULD HAVE METABOLIC SURGERY?

Until recently, there was no clear national or international consensus on the role of metabolic surgery in treating type 2 DM. In 2015, the 2nd Diabetes Surgery Summit (DSS-II) Consensus Conference published guidelines that were endorsed by more than 50 diabetes and medical organizations.5 The recommendations cover many clinically relevant issues, including patient selection, preoperative evaluation, choice of procedure, and postoperative follow-up. The consensus conference delegates concluded that there is sufficient evidence demonstrating that metabolic surgery achieves excellent glycemic control and reduces cardiovascular risk factors.

The treatment algorithm from DSS-II incorporates appropriate use of all 3 treatment modalities: lifestyle intervention, drug therapy, and surgery (Figure 5).5 The 2017 Standards of Care for Diabetes from the American Diabetes Association include those key indications in the recommendations for metabolic surgery (Table 3).2

SUMMARY

The safety of metabolic surgery has significantly improved with the advent of laparoscopic surgery and recent national quality improvement initiatives that have made gastric bypass and SG as safe as cholecystectomy and appendectomy. Although observational studies suggest that metabolic surgery is associated with a reduction in cardiovascular and diabetes complications and mortality, these observations have not been confirmed in long-term RCTs.

Based on the published evidence, metabolic surgery is now endorsed as a standard treatment option, which provides patients and practitioners with a powerful tool to help combat the life-impairing effects of type 2 DM.

- Bays HE, Chapman RH, Grandy S; for the SHIELD Investigators Group. The relationship of body mass index to diabetes mellitus, hypertension and dyslipidaemia: comparison of data from two national surveys. Int J Clin Pract May 2007; 61:737–747.

- Marathe PH, Gao HX, Close KL. American Diabetes Association standards of medical care in diabetes—2017. Diabetes Care 2017; 40(suppl 1):S1–S135.

- Fox CS, Golden SH, Anderson C, et al; American Heart Association; American Diabetes Association. Update on prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus in light of recent evidence: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American Diabetes Association. Circulation 2015; 132:691–718.

- Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; Obesity Society. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 63:2985–3023.

- Rubino F, Nathan DM, Eckel RH, et al; Delegates of the 2nd Diabetes Surgery Summit. Metabolic surgery in the treatment algorithm for type 2 diabetes: a joint statement by international diabetes organizations. Diabetes Care 2016; 39:861–877.

- Stark Casagrande S, Fradkin JE, Saydah SH, Rust KF, Cowie CC. The prevalence of meeting A1C, blood pressure, and LDL goals among people with diabetes, 1988–2010. Diabetes Care 2013; 36:2271–2279.

- Kolandaivelu K, Leiden BB, O’Gara PT, Bhatt DL. Non-adherence to cardiovascular medications. Eur Heart J 2014; 35:3267–3276.

- Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P, Formisano G, Buchwald H, Scopinaro N. Bariatric surgery worldwide 2013. Obes Surg 2015; 25:1822–1832.

- Schauer PR, Mingrone G, Ikramuddin S, Wolfe B. Clinical outcomes of metabolic surgery: efficacy of glycemic control, weight loss, and remission of diabetes. Diabetes Care 2016; 39:902–911.

- Khorgami Z, Andalib A, Corcelles R, Aminian A, Brethauer S, Schauer P. Recent national trends in the surgical treatment of obesity: sleeve gastrectomy dominates. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2015; 11(suppl):S1–S34 [Abstract A111].

- Consensus Development Conference Panel. NIH conference. Gastrointestinal surgery for severe obesity. Ann Intern Med 1991; 115:956–961.

- Pories WJ, MacDonald KG Jr, Flickinger EG, et al. Is type II diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) a surgical disease? Ann Surg 1992; 215:633–642.

- Schauer PR, Burguera B, Ikramuddin S, et al. Effect of laparoscopic Roux-en Y gastric bypass on type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Surg 2003; 238:467–484.

- Rubino F, Marescaux J. Effect of duodenal-jejunal exclusion in a non-obese animal model of type 2 diabetes: a new perspective for an old disease. Ann Surg 2004; 239:1–11.

- Batterham RL, Cummings DE. Mechanisms of diabetes improvement following bariatric/metabolic surgery. Diabetes Care 2016; 39:893–901.

- Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2004; 292:1724–1737.

- Brethauer SA, Hammel JP, Schauer PR. Systematic review of sleeve gastrectomy as staging and primary bariatric procedure. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2009; 5:469–475.

- Eid GM, Brethauer S, Mattar SG, Titchner RL, Gourash W, Schauer PR. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for super obese patients: forty-eight percent excess weight loss after 6 to 8 years with 93% follow-up. Ann Surg 2012; 256:262–265.

- Sjöström L, Peltonen M, Jacobson P, et al. Bariatric surgery and long-term cardiovascular events. JAMA 2012; 307:56–65.

- Maciejewski ML, Arterburn DE, Van Scoyoc L, et al. Bariatric surgery and long-term durability of weight loss. JAMA Surg 2016; 151:1046–1055.

- Wing RR, Bolin P, Brancati FL, et al; for the Look AHEAD Research Group. Cardiovascular effects of intensive lifestyle intervention in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2013; 369:145–154.

- Buchwald H, Estok R, Fahrbach K, et al. Weight and type 2 diabetes after bariatric surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Med 2009; 122:248–256.

- Sjöström L, Lindroos AK, Peltonen M, et al; Swedish Obese Subjects Study Scientific Group. Lifestyle, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors 10 years after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med 2004; 351:2683–2693.

- Vest AR, Heneghan HM, Agarwal S, Schauer PR, Young JB. Bariatric surgery and cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review. Heart 2012; 98:1763–1777.

- Vest AR, Heneghan HM, Schauer PR, Young JB. Surgical management of obesity and the relationship to cardiovascular disease. Circulation 2013; 127:945–959.

- Arterburn DE, Olsen MK, Smith VA, et al. Association between bariatric surgery and long-term survival. JAMA 2015; 313:62–70.

- Sjöström L, Peltonen M, Jacobson P, et al. Association of bariatric surgery with long-term remission of type 2 diabetes and with microvascular and macrovascular complications. JAMA 2014; 311:2297–2304.

- Dixon JB, O’Brien PE, Playfair J, et al. Adjustable gastric banding and conventional therapy for type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2008; 299:316–323.

- Schauer PR, Kashyap SR, Wolski K, et al. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy in obese patients with diabetes. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:1567–1576.

- Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, et al; STAMPEDE Investigators. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes—3-year outcomes. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:2002–2013.

- Mingrone G, Panunzi S, De Gaetano A, et al. Bariatric surgery versus conventional medical therapy for type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:1577–1585.

- Mingrone G, Panunzi S, De Gaetano A, et al. Bariatric-metabolic surgery versus conventional medical treatment in obese patients with type 2 diabetes: 5 year follow-up of an open-label, single-centre, randomized controlled trial. Lancet 2015; 386:964–973.

- Ikramuddin S, Korner J, Lee WJ, et al. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass vs intensive medical management for the control of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia: the Diabetes Surgery Study randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2013; 309:2240–2249.

- Ikramuddin S, Billington CJ, Lee WJ, et al. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for diabetes (the Diabetes Surgery Study): 2-year outcomes of a 5-year, randomized, controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2015; 3:413–422.

- Liang Z, Wu Q, Chen B, Yu P, Zhao H, Ouyang X. Effect of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery on type 2 diabetes mellitus with hypertension: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2013; 101:50–56.

- Halperin F, Ding SA, Simonson DC, et al. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery or lifestyle with intensive medical management in patients with type 2 diabetes: feasibility and 1-year results of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg 2014; 149:716–726.

- Courcoulas AP, Goodpaster BH, Eagleton JK, et al. Surgical vs medical treatments for type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg 2014; 149:707–715.

- Courcoulas AP, Belle SH, Neiberg RH, et al. Three-year outcomes of bariatric surgery vs. lifestyle intervention for type 2 diabetes mellitus treatment: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg 2015; 150:931–940.

- Wentworth JM, Playfair J, Laurie C, et al. Multidisciplinary diabetes care with and without bariatric surgery in overweight people: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014; 2:545–552.

- Parikh M, Chung M, Sheth S, et al. Randomized pilot trial of bariatric surgery versus intensive medical weight management on diabetes remission in type 2 diabetic patients who do not meet NIH criteria for surgery and the role of soluble RAGE as a novel biomarker of success. Ann Surg 2014; 260:617–622.

- Ding SA, Simonson DC, Wewalka M, et al. Adjustable gastric band surgery or medical management in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015; 100:2546–2556.

- Cummings DE, Arterburn DE, Westbrook EO, et al. Gastric bypass surgery vs. intensive lifestyle and medical intervention for type 2 diabetes: the CROSSROADS randomized controlled trial. Diabetologia 2016; 59:945–953.

- Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, et al; STAMPEDE Investigators. Metabolic surgery vs. intensive medical therapy for diabetes: 5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med 2017; 376:641–651.

- Shah SS, Todkar J, Phadake U, et al. Gastric bypass vs. medical/lifestyle care for type 2 diabetes in South Asians with BMI 25-40 kg/m2: the COSMID randomized trial [261-OR]. Presented at the American Diabetes Association’s 76th Scientific Session; June 10–14, 2016; New Orleans, LA.

- Flum DR, Belle SH, King WC, et al; Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS) Consortium. Perioperative safety in the longitudinal assessment of bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:445–454.

- Aminian A, Brethauer SA, Kirwan JP, Kashyap SR, Burguera B, Schauer PR. How safe is metabolic/diabetes surgery? Diabetes Obes Metab 2015; 17:198–201.

- Thodiyil PA, Yenumula P, Rogula T, et al. Selective non operative management of leaks after gastric bypass: lessons learned from 2675 consecutive patients. Ann Surg 2008; 248:782–792.

- Rogula T, Yenumula PR, Schauer PR. A complication of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: intestinal obstruction. Surg Endosc 2007; 21:1914–1918.

- Thornton CM, Rozen WM, So D, Kaplan ED, Wilkinson S. Reducing band slippage in laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding: the mesh plication pars flaccida technique. Obes Surg 2009; 19:1702–1706.

- Himpens J, Cadière G-B, Bazi M, Vouche M, Cadière B, Dapri G. Long-term outcomes of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Arch Surg 2011; 146:802–807.

- Madan AK, Orth WS, Tichansky DS, Ternovits CA. Vitamin and trace mineral levels after laparoscopic gastric bypass. Obes Surg 2006; 16:603–606.

- Love AL, Billett HH. Obesity, bariatric surgery, and iron deficiency: true, true, true and related. Am J Hematol 2008; 83:403–409.

- Shankar P, Boylan M, Sriram K. Micronutrient deficiencies after bariatric surgery. Nutrition 2010; 26:1031–1037.

- Gong K, Gagner M, Pomp A, Almahmeed T, Bardaro SJ. Micronutrient deficiencies after laparoscopic gastric bypass: recommendations. Obes Surg 2008; 18:1062–1066.

- Scibora LM. Skeletal effects of bariatric surgery: examining bone loss, potential mechanisms and clinical relevance. Diabetes Obes Metab 2014; 16:1204–1213.

- Baptista V, Wassef W. Bariatric procedures: an update on techniques, outcomes and complications. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2013; 29:684–693.

- Matlaga BR, Shore AD, Magnuson T, Clark JM, Johns R, Makary MA. Effect of gastric bypass surgery on kidney stone disease. J Urol 2009; 181:2573–2577.

- Sakhaee K, Poindexter J, Aguirre C. The effects of bariatric surgery on bone and nephrolithiasis. Bone 2016; 84:1–8.

- Li L, Wu LT. Substance use after bariatric surgery: a review. J Psychiatr Res 2016; 76:16–29.

- Ayloo S, Thompson K, Choudhury N, Sheriffdeen R. Correlation between the Beck Depression Inventory and bariatric surgical procedures. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2015; 11:637–342.

- Adams TD, Gress RE, Smith SC, et al. Long-term mortality after gastric bypass surgery. N Engl J Med 2007; 357:753–761.

- Sjöström L, Narbro K, Sjöström CD, et al; Swedish Obese Subjects Study. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med 2007; 357:741–752.

- Mitchell JE, Crosby R, de Zwaan M, et al. Possible risk factors for increased suicide following bariatric surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013; 21:665–672.

- Fouse T, Schauer P. The socioeconomic impact of morbid obesity and factors affecting access to obesity surgery. Surg Clin North Am 2016; 96:669–679.

- Rubin JK, Hinrichs-Krapels S, Hesketh R, Martin A, Herman WH, Rubino F. Identifying barriers to appropriate use of metabolic/bariatric surgery for type 2 diabetes treatment: policy lab results. Diabetes Care 2016; 39:954–963.

- Bays HE, Chapman RH, Grandy S; for the SHIELD Investigators Group. The relationship of body mass index to diabetes mellitus, hypertension and dyslipidaemia: comparison of data from two national surveys. Int J Clin Pract May 2007; 61:737–747.

- Marathe PH, Gao HX, Close KL. American Diabetes Association standards of medical care in diabetes—2017. Diabetes Care 2017; 40(suppl 1):S1–S135.

- Fox CS, Golden SH, Anderson C, et al; American Heart Association; American Diabetes Association. Update on prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus in light of recent evidence: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American Diabetes Association. Circulation 2015; 132:691–718.

- Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; Obesity Society. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 63:2985–3023.

- Rubino F, Nathan DM, Eckel RH, et al; Delegates of the 2nd Diabetes Surgery Summit. Metabolic surgery in the treatment algorithm for type 2 diabetes: a joint statement by international diabetes organizations. Diabetes Care 2016; 39:861–877.

- Stark Casagrande S, Fradkin JE, Saydah SH, Rust KF, Cowie CC. The prevalence of meeting A1C, blood pressure, and LDL goals among people with diabetes, 1988–2010. Diabetes Care 2013; 36:2271–2279.

- Kolandaivelu K, Leiden BB, O’Gara PT, Bhatt DL. Non-adherence to cardiovascular medications. Eur Heart J 2014; 35:3267–3276.

- Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P, Formisano G, Buchwald H, Scopinaro N. Bariatric surgery worldwide 2013. Obes Surg 2015; 25:1822–1832.

- Schauer PR, Mingrone G, Ikramuddin S, Wolfe B. Clinical outcomes of metabolic surgery: efficacy of glycemic control, weight loss, and remission of diabetes. Diabetes Care 2016; 39:902–911.

- Khorgami Z, Andalib A, Corcelles R, Aminian A, Brethauer S, Schauer P. Recent national trends in the surgical treatment of obesity: sleeve gastrectomy dominates. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2015; 11(suppl):S1–S34 [Abstract A111].

- Consensus Development Conference Panel. NIH conference. Gastrointestinal surgery for severe obesity. Ann Intern Med 1991; 115:956–961.

- Pories WJ, MacDonald KG Jr, Flickinger EG, et al. Is type II diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) a surgical disease? Ann Surg 1992; 215:633–642.

- Schauer PR, Burguera B, Ikramuddin S, et al. Effect of laparoscopic Roux-en Y gastric bypass on type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Surg 2003; 238:467–484.

- Rubino F, Marescaux J. Effect of duodenal-jejunal exclusion in a non-obese animal model of type 2 diabetes: a new perspective for an old disease. Ann Surg 2004; 239:1–11.