User login

Verma unveils Medicaid scorecard but refuses to judge efforts

“This is about bringing a level of transparency and accountability to the Medicaid program that we have never had before,” said Seema Verma, administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Yet in a meeting with reporters, Ms. Verma refused to discuss the findings in any detail or comment on any individual states that performed poorly or exceptionally.

“I will let you look at the data and make your own conclusions,” she told journalists a few minutes before the report was posted online.

When reporters pressed Ms. Verma to comment on the document, she refused to give an assessment of the Medicaid program, the federal-state health program for low-income residents. She has run Medicaid for the past 15 months.

“The idea here is to give you a sense of where states are on different areas,” she said. “The idea is to be used for best practices,” and it’s “an opportunity for us to identify” and have discussions with states that aren’t performing well.

Medicaid covers about 75 million people, about half of them children.

The report looked at how well states provide a wide variety of health services to children and adults. It also reviewed how quickly the federal government was approving state waiver requests to change their programs.

But not all states provided data for each service because sharing information was voluntary.

For example, half the states did not show how well they control Medicaid enrollees’ blood pressure.

The National Association of Medicaid Directors panned the scorecard. It acknowledged the need for a system to measure performance but said its members have concerns about its accuracy and usefulness.

“There are significant methodological issues with the underlying data, including completeness, timeliness, and quality,” the association said in a statement. It noted that most of the data come from 2015.

As expected, the data showed great variation in how states provide care, including immunizing teenagers and getting dental care to children. A big reason is that state Medicaid benefits and payments to doctors vary dramatically, the Medicaid directors said, so that “it will not be possible to make apples-to-apples comparisons between states.”

In her first public speech, Ms. Verma promised last November to release a Medicaid scorecard. She said states won’t immediately face any consequences for poor performance – but that could change.

“The data … begins to offer taxpayers insights into how their dollars are being spent and the impact those dollars have on health outcomes,” Ms. Verma said on June 4.

Sara Rosenbaum, a professor of health law and policy at George Washington University in Washington, who previously led a congressional advisory board on Medicaid, suggested that the information is still too incomplete to be of great value.

“It is amazing to me that in 2018 this is all we have when trying to understand how the nation’s largest insurer performs for its poorest and most vulnerable residents,” she said.

KHN’s coverage of children’s health care issues is supported in part by the Heising-Simons Foundation. Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

“This is about bringing a level of transparency and accountability to the Medicaid program that we have never had before,” said Seema Verma, administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Yet in a meeting with reporters, Ms. Verma refused to discuss the findings in any detail or comment on any individual states that performed poorly or exceptionally.

“I will let you look at the data and make your own conclusions,” she told journalists a few minutes before the report was posted online.

When reporters pressed Ms. Verma to comment on the document, she refused to give an assessment of the Medicaid program, the federal-state health program for low-income residents. She has run Medicaid for the past 15 months.

“The idea here is to give you a sense of where states are on different areas,” she said. “The idea is to be used for best practices,” and it’s “an opportunity for us to identify” and have discussions with states that aren’t performing well.

Medicaid covers about 75 million people, about half of them children.

The report looked at how well states provide a wide variety of health services to children and adults. It also reviewed how quickly the federal government was approving state waiver requests to change their programs.

But not all states provided data for each service because sharing information was voluntary.

For example, half the states did not show how well they control Medicaid enrollees’ blood pressure.

The National Association of Medicaid Directors panned the scorecard. It acknowledged the need for a system to measure performance but said its members have concerns about its accuracy and usefulness.

“There are significant methodological issues with the underlying data, including completeness, timeliness, and quality,” the association said in a statement. It noted that most of the data come from 2015.

As expected, the data showed great variation in how states provide care, including immunizing teenagers and getting dental care to children. A big reason is that state Medicaid benefits and payments to doctors vary dramatically, the Medicaid directors said, so that “it will not be possible to make apples-to-apples comparisons between states.”

In her first public speech, Ms. Verma promised last November to release a Medicaid scorecard. She said states won’t immediately face any consequences for poor performance – but that could change.

“The data … begins to offer taxpayers insights into how their dollars are being spent and the impact those dollars have on health outcomes,” Ms. Verma said on June 4.

Sara Rosenbaum, a professor of health law and policy at George Washington University in Washington, who previously led a congressional advisory board on Medicaid, suggested that the information is still too incomplete to be of great value.

“It is amazing to me that in 2018 this is all we have when trying to understand how the nation’s largest insurer performs for its poorest and most vulnerable residents,” she said.

KHN’s coverage of children’s health care issues is supported in part by the Heising-Simons Foundation. Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

“This is about bringing a level of transparency and accountability to the Medicaid program that we have never had before,” said Seema Verma, administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Yet in a meeting with reporters, Ms. Verma refused to discuss the findings in any detail or comment on any individual states that performed poorly or exceptionally.

“I will let you look at the data and make your own conclusions,” she told journalists a few minutes before the report was posted online.

When reporters pressed Ms. Verma to comment on the document, she refused to give an assessment of the Medicaid program, the federal-state health program for low-income residents. She has run Medicaid for the past 15 months.

“The idea here is to give you a sense of where states are on different areas,” she said. “The idea is to be used for best practices,” and it’s “an opportunity for us to identify” and have discussions with states that aren’t performing well.

Medicaid covers about 75 million people, about half of them children.

The report looked at how well states provide a wide variety of health services to children and adults. It also reviewed how quickly the federal government was approving state waiver requests to change their programs.

But not all states provided data for each service because sharing information was voluntary.

For example, half the states did not show how well they control Medicaid enrollees’ blood pressure.

The National Association of Medicaid Directors panned the scorecard. It acknowledged the need for a system to measure performance but said its members have concerns about its accuracy and usefulness.

“There are significant methodological issues with the underlying data, including completeness, timeliness, and quality,” the association said in a statement. It noted that most of the data come from 2015.

As expected, the data showed great variation in how states provide care, including immunizing teenagers and getting dental care to children. A big reason is that state Medicaid benefits and payments to doctors vary dramatically, the Medicaid directors said, so that “it will not be possible to make apples-to-apples comparisons between states.”

In her first public speech, Ms. Verma promised last November to release a Medicaid scorecard. She said states won’t immediately face any consequences for poor performance – but that could change.

“The data … begins to offer taxpayers insights into how their dollars are being spent and the impact those dollars have on health outcomes,” Ms. Verma said on June 4.

Sara Rosenbaum, a professor of health law and policy at George Washington University in Washington, who previously led a congressional advisory board on Medicaid, suggested that the information is still too incomplete to be of great value.

“It is amazing to me that in 2018 this is all we have when trying to understand how the nation’s largest insurer performs for its poorest and most vulnerable residents,” she said.

KHN’s coverage of children’s health care issues is supported in part by the Heising-Simons Foundation. Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

HHS says no to lifetime limits on Medicaid

The Trump administration’s promise of unprecedented flexibility to states in running their Medicaid programs hit its limit on May 7.

“We seek to create a pathway out of poverty, but we also understand that people’s circumstances change, and we must ensure that our programs are sustainable and available to them when they need and qualify for them,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said May 7 at an American Hospital Association meeting in Washington.

Arizona, Utah, Maine and Wisconsin have also requested lifetime limits on Medicaid.

This marked the first time the Trump administration has rejected a state’s Medicaid waiver request regarding who is eligible for the program.

Critics of time limits, who say such a change would unfairly burden people who struggle financially throughout their lives, cheered the decision.

“This is good news,” said Joan Alker, executive director of Georgetown University’s Center for Children and Families, a Medicaid advocate. “This was a bridge too far for this CMS.”

Ms. Alker’s enthusiasm, though, was tempered because Ms. Verma did not also reject Kansas’ effort to place work requirements on some adult enrollees. That decision is still pending.

CMS has approved work requirements for adults in four states – the latest, New Hampshire, winning approval May 7. The other states are Kentucky, Indiana, and Arkansas.

All these states expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act to cover everyone with incomes of more than 138% of the federal poverty level ($16,753 for an individual). The work requirements would apply only to adults added through that ACA expansion.

Kansas and a handful of states, including Alabama and Mississippi – which did not expand the program – want to add the work requirement for some of their adult enrollees, many of whom have incomes well below the poverty level. In Kansas, an individual qualifying for Medicaid can earn no more than $4,600.

Adding work requirements to Medicaid has also been controversial. The National Health Law Program, an advocacy group, has filed suit against CMS and Kentucky to block the work requirement from taking effect, saying it violates federal law.

The Kansas proposal would have imposed a cumulative 3-year maximum benefit only on Medicaid recipients deemed able to work. It would have applied to about 12,000 low-income parents who make up a tiny fraction of the 400,000 Kansans who receive Medicaid.

Kansas Gov. Jeff Colyer, a Republican, responded to the announcement saying state officials decided in April to no longer pursue the lifetime limits after CMS indicated it would not be approved.

“While we will not be moving forward with lifetime caps, we are pleased that the Administration has been supportive of our efforts to include a work requirement in the [Medicaid] waiver,” Gov. Colyer said in a statement. “This important provision will help improve outcomes and ensure that Kansans are empowered to achieve self-sufficiency.”

Eliot Fishman, senior director of health policy for the advocacy group Families USA, applauded Ms. Verma’s decision.

“The decision on the Kansas time limits proposal that Seema Verma announced today is the right one. CMS should apply this precedent to all state requests to impose time limits on any group of people who get health coverage through Medicaid – including adults who are covered through Medicaid expansion,” he said. “Time limits in Medicaid are bad law and bad policy, harming people who rely on the program for lifesaving health care.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

The Trump administration’s promise of unprecedented flexibility to states in running their Medicaid programs hit its limit on May 7.

“We seek to create a pathway out of poverty, but we also understand that people’s circumstances change, and we must ensure that our programs are sustainable and available to them when they need and qualify for them,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said May 7 at an American Hospital Association meeting in Washington.

Arizona, Utah, Maine and Wisconsin have also requested lifetime limits on Medicaid.

This marked the first time the Trump administration has rejected a state’s Medicaid waiver request regarding who is eligible for the program.

Critics of time limits, who say such a change would unfairly burden people who struggle financially throughout their lives, cheered the decision.

“This is good news,” said Joan Alker, executive director of Georgetown University’s Center for Children and Families, a Medicaid advocate. “This was a bridge too far for this CMS.”

Ms. Alker’s enthusiasm, though, was tempered because Ms. Verma did not also reject Kansas’ effort to place work requirements on some adult enrollees. That decision is still pending.

CMS has approved work requirements for adults in four states – the latest, New Hampshire, winning approval May 7. The other states are Kentucky, Indiana, and Arkansas.

All these states expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act to cover everyone with incomes of more than 138% of the federal poverty level ($16,753 for an individual). The work requirements would apply only to adults added through that ACA expansion.

Kansas and a handful of states, including Alabama and Mississippi – which did not expand the program – want to add the work requirement for some of their adult enrollees, many of whom have incomes well below the poverty level. In Kansas, an individual qualifying for Medicaid can earn no more than $4,600.

Adding work requirements to Medicaid has also been controversial. The National Health Law Program, an advocacy group, has filed suit against CMS and Kentucky to block the work requirement from taking effect, saying it violates federal law.

The Kansas proposal would have imposed a cumulative 3-year maximum benefit only on Medicaid recipients deemed able to work. It would have applied to about 12,000 low-income parents who make up a tiny fraction of the 400,000 Kansans who receive Medicaid.

Kansas Gov. Jeff Colyer, a Republican, responded to the announcement saying state officials decided in April to no longer pursue the lifetime limits after CMS indicated it would not be approved.

“While we will not be moving forward with lifetime caps, we are pleased that the Administration has been supportive of our efforts to include a work requirement in the [Medicaid] waiver,” Gov. Colyer said in a statement. “This important provision will help improve outcomes and ensure that Kansans are empowered to achieve self-sufficiency.”

Eliot Fishman, senior director of health policy for the advocacy group Families USA, applauded Ms. Verma’s decision.

“The decision on the Kansas time limits proposal that Seema Verma announced today is the right one. CMS should apply this precedent to all state requests to impose time limits on any group of people who get health coverage through Medicaid – including adults who are covered through Medicaid expansion,” he said. “Time limits in Medicaid are bad law and bad policy, harming people who rely on the program for lifesaving health care.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

The Trump administration’s promise of unprecedented flexibility to states in running their Medicaid programs hit its limit on May 7.

“We seek to create a pathway out of poverty, but we also understand that people’s circumstances change, and we must ensure that our programs are sustainable and available to them when they need and qualify for them,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said May 7 at an American Hospital Association meeting in Washington.

Arizona, Utah, Maine and Wisconsin have also requested lifetime limits on Medicaid.

This marked the first time the Trump administration has rejected a state’s Medicaid waiver request regarding who is eligible for the program.

Critics of time limits, who say such a change would unfairly burden people who struggle financially throughout their lives, cheered the decision.

“This is good news,” said Joan Alker, executive director of Georgetown University’s Center for Children and Families, a Medicaid advocate. “This was a bridge too far for this CMS.”

Ms. Alker’s enthusiasm, though, was tempered because Ms. Verma did not also reject Kansas’ effort to place work requirements on some adult enrollees. That decision is still pending.

CMS has approved work requirements for adults in four states – the latest, New Hampshire, winning approval May 7. The other states are Kentucky, Indiana, and Arkansas.

All these states expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act to cover everyone with incomes of more than 138% of the federal poverty level ($16,753 for an individual). The work requirements would apply only to adults added through that ACA expansion.

Kansas and a handful of states, including Alabama and Mississippi – which did not expand the program – want to add the work requirement for some of their adult enrollees, many of whom have incomes well below the poverty level. In Kansas, an individual qualifying for Medicaid can earn no more than $4,600.

Adding work requirements to Medicaid has also been controversial. The National Health Law Program, an advocacy group, has filed suit against CMS and Kentucky to block the work requirement from taking effect, saying it violates federal law.

The Kansas proposal would have imposed a cumulative 3-year maximum benefit only on Medicaid recipients deemed able to work. It would have applied to about 12,000 low-income parents who make up a tiny fraction of the 400,000 Kansans who receive Medicaid.

Kansas Gov. Jeff Colyer, a Republican, responded to the announcement saying state officials decided in April to no longer pursue the lifetime limits after CMS indicated it would not be approved.

“While we will not be moving forward with lifetime caps, we are pleased that the Administration has been supportive of our efforts to include a work requirement in the [Medicaid] waiver,” Gov. Colyer said in a statement. “This important provision will help improve outcomes and ensure that Kansans are empowered to achieve self-sufficiency.”

Eliot Fishman, senior director of health policy for the advocacy group Families USA, applauded Ms. Verma’s decision.

“The decision on the Kansas time limits proposal that Seema Verma announced today is the right one. CMS should apply this precedent to all state requests to impose time limits on any group of people who get health coverage through Medicaid – including adults who are covered through Medicaid expansion,” he said. “Time limits in Medicaid are bad law and bad policy, harming people who rely on the program for lifesaving health care.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

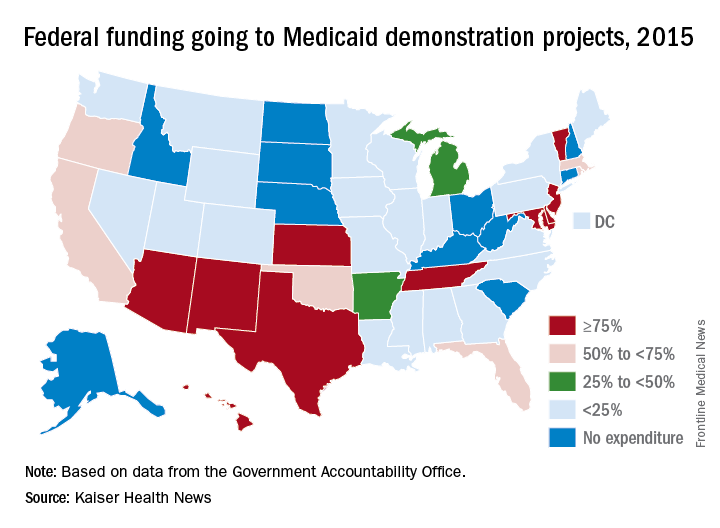

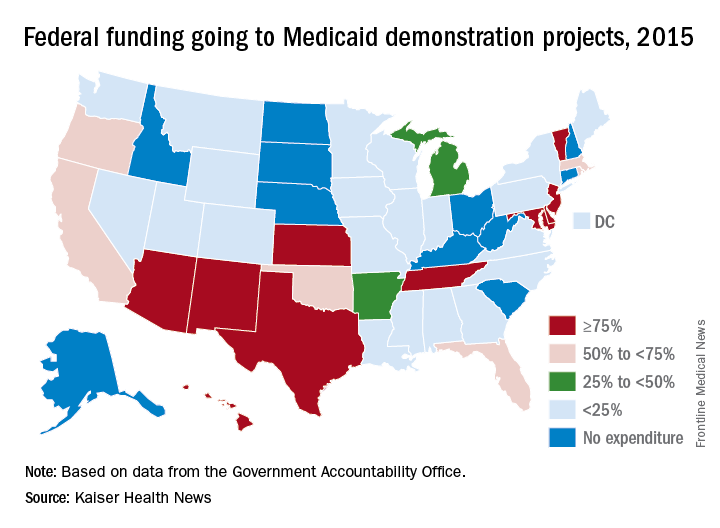

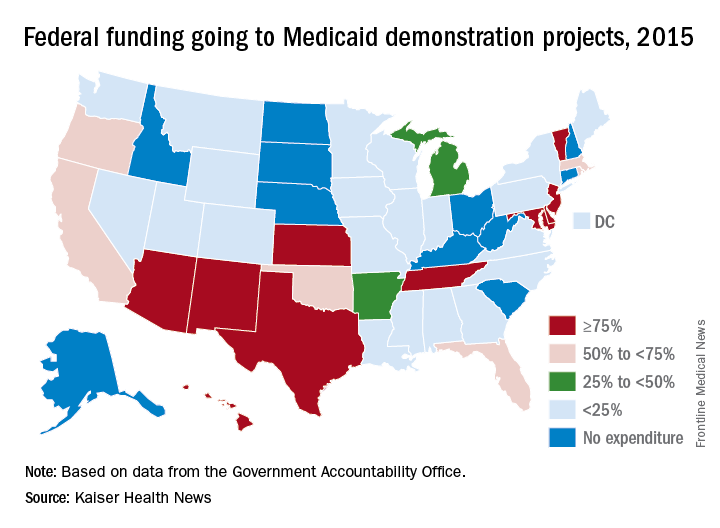

Evaluations of Medicaid experiments by states, CMS are weak, GAO says

With federal spending on Medicaid experiments soaring in recent years, a congressional watchdog said state and federal governments fail to adequately evaluate if the efforts improve care and save money.

A study by the Government Accountability Office released Feb. 20 found that some states don’t complete evaluation reports for up to 7 years after an experiment begins and often fail to answer vital questions to determine effectiveness. The GAO also slammed the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for failing to make results from Medicaid evaluation reports public in a timely manner.

“CMS is missing an opportunity to inform federal and state policy discussions,” the GAO report said.

Joan Alker, executive director of the Georgetown University Center for Children and Families, called the report’s findings “troubling but not surprising.”

“It has been clear for some time that evaluations of Section 1115 waivers are not adequate,” she said. “There is some good work going on in this space at the state level, for example in Michigan and Iowa, but as the report makes clear state’s evaluations are often incomplete and not rigorous enough.”

These experiments are often called “demonstration projects” or “1115 demonstration waivers” – based on the section of the law that allows the federal government to authorize them. They allow federal officials to approve states’ requests to test new approaches to providing coverage. They are used for a wide variety of purposes, including efforts to extend Medicaid to people or services not generally covered or to change payment systems to improve care.

Medicaid demonstration programs often run for a decade or more. Several states that expanded Medicaid eligibility under the Affordable Care Act did so through a demonstration program, including Indiana, Iowa, Arkansas and New Hampshire.

The study, requested by top GOP lawmakers including Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah), reviewed demonstration programs in eight states – Arizona, Arkansas, California, Indiana, Kansas, Maryland, Massachusetts, and New York.

In five of these states, money from their Medicaid demonstration program makes up more than half their total federal Medicaid budgets. Nearly all of Arizona’s funding – 99.7% – is through a demonstration program.

The use of Medicaid demonstration programs accelerated during the 1990s. But, in recent years, the experiments often have reflected the political leanings of state officials or the party controlling the White House. Under a demonstration program, the Trump administration this year approved requests from Indiana and Kentucky to enact work requirements for some adult Medicaid enrollees.

The GAO report noted that states often do not complete their evaluation reports until after the federal government renews their demonstration program. For example, Indiana’s Medicaid expansion demonstration program, which charges premiums and locks some enrollees out of coverage for lack of payment, was renewed in February even though a final evaluation report is not yet complete.

GAO said Indiana’s evaluation of its Medicaid expansion won’t look at the effect of the state’s provision that locks out enrollees for six months if they fail to pay premiums.

“GAO found that selected states’ evaluations of these demonstrations often had significant limitations that affected their usefulness in informing policy decisions,” the report said.

Ms. Alker said that “more sunshine and data are needed” to assess waivers, “especially as they are clearly the vehicle the Trump administration is now using to pursue its ideological objectives for Medicaid.”

While states typically contract with independent groups to evaluate Medicaid demonstration programs, the federal government sometimes does its own review.

But the GAO investigators found Indiana’s Medicaid agency wasn’t willing to work with the federal contractor out of privacy concerns, which halted efforts for a federal review.

Joel Cantor, director of the Center for State Health Policy at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, N.J., said the demonstration programs often have shifted from their intended purpose because they are designed by lawmakers pushing an agenda rather than as a scientific experiment to find better ways to deliver care.

“Demonstration programs have been used since the 1990s to advance policy agenda for whoever holds power in Washington and not designed to test an innovative idea,” he said.

The evaluations often take several years to complete, he said, because of the difficulty of getting patient data from states. His center has done evaluations for New Jersey’s Medicaid program.

GAO recommended that CMS require states to submit a final evaluation report after the end of the waiver period, regardless of whether the experiment is being renewed, and that the federal agency publicly release findings from federal evaluations in a timely manner. Federal officials said they agreed with the recommendations.

Matt Salo, executive director of the National Association of Medicaid Directors, said the report highlighted a need to modernize the law dealing with Medicaid so that successful experiments are quickly incorporated into the overall program.

“The underlying problem is that the Medicaid statute has fundamentally failed to keep up with the changing reality of health care in the 21st century,” he said. “There’s no way to update the rules to make these changes” a permanent part of the program.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

With federal spending on Medicaid experiments soaring in recent years, a congressional watchdog said state and federal governments fail to adequately evaluate if the efforts improve care and save money.

A study by the Government Accountability Office released Feb. 20 found that some states don’t complete evaluation reports for up to 7 years after an experiment begins and often fail to answer vital questions to determine effectiveness. The GAO also slammed the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for failing to make results from Medicaid evaluation reports public in a timely manner.

“CMS is missing an opportunity to inform federal and state policy discussions,” the GAO report said.

Joan Alker, executive director of the Georgetown University Center for Children and Families, called the report’s findings “troubling but not surprising.”

“It has been clear for some time that evaluations of Section 1115 waivers are not adequate,” she said. “There is some good work going on in this space at the state level, for example in Michigan and Iowa, but as the report makes clear state’s evaluations are often incomplete and not rigorous enough.”

These experiments are often called “demonstration projects” or “1115 demonstration waivers” – based on the section of the law that allows the federal government to authorize them. They allow federal officials to approve states’ requests to test new approaches to providing coverage. They are used for a wide variety of purposes, including efforts to extend Medicaid to people or services not generally covered or to change payment systems to improve care.

Medicaid demonstration programs often run for a decade or more. Several states that expanded Medicaid eligibility under the Affordable Care Act did so through a demonstration program, including Indiana, Iowa, Arkansas and New Hampshire.

The study, requested by top GOP lawmakers including Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah), reviewed demonstration programs in eight states – Arizona, Arkansas, California, Indiana, Kansas, Maryland, Massachusetts, and New York.

In five of these states, money from their Medicaid demonstration program makes up more than half their total federal Medicaid budgets. Nearly all of Arizona’s funding – 99.7% – is through a demonstration program.

The use of Medicaid demonstration programs accelerated during the 1990s. But, in recent years, the experiments often have reflected the political leanings of state officials or the party controlling the White House. Under a demonstration program, the Trump administration this year approved requests from Indiana and Kentucky to enact work requirements for some adult Medicaid enrollees.

The GAO report noted that states often do not complete their evaluation reports until after the federal government renews their demonstration program. For example, Indiana’s Medicaid expansion demonstration program, which charges premiums and locks some enrollees out of coverage for lack of payment, was renewed in February even though a final evaluation report is not yet complete.

GAO said Indiana’s evaluation of its Medicaid expansion won’t look at the effect of the state’s provision that locks out enrollees for six months if they fail to pay premiums.

“GAO found that selected states’ evaluations of these demonstrations often had significant limitations that affected their usefulness in informing policy decisions,” the report said.

Ms. Alker said that “more sunshine and data are needed” to assess waivers, “especially as they are clearly the vehicle the Trump administration is now using to pursue its ideological objectives for Medicaid.”

While states typically contract with independent groups to evaluate Medicaid demonstration programs, the federal government sometimes does its own review.

But the GAO investigators found Indiana’s Medicaid agency wasn’t willing to work with the federal contractor out of privacy concerns, which halted efforts for a federal review.

Joel Cantor, director of the Center for State Health Policy at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, N.J., said the demonstration programs often have shifted from their intended purpose because they are designed by lawmakers pushing an agenda rather than as a scientific experiment to find better ways to deliver care.

“Demonstration programs have been used since the 1990s to advance policy agenda for whoever holds power in Washington and not designed to test an innovative idea,” he said.

The evaluations often take several years to complete, he said, because of the difficulty of getting patient data from states. His center has done evaluations for New Jersey’s Medicaid program.

GAO recommended that CMS require states to submit a final evaluation report after the end of the waiver period, regardless of whether the experiment is being renewed, and that the federal agency publicly release findings from federal evaluations in a timely manner. Federal officials said they agreed with the recommendations.

Matt Salo, executive director of the National Association of Medicaid Directors, said the report highlighted a need to modernize the law dealing with Medicaid so that successful experiments are quickly incorporated into the overall program.

“The underlying problem is that the Medicaid statute has fundamentally failed to keep up with the changing reality of health care in the 21st century,” he said. “There’s no way to update the rules to make these changes” a permanent part of the program.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

With federal spending on Medicaid experiments soaring in recent years, a congressional watchdog said state and federal governments fail to adequately evaluate if the efforts improve care and save money.

A study by the Government Accountability Office released Feb. 20 found that some states don’t complete evaluation reports for up to 7 years after an experiment begins and often fail to answer vital questions to determine effectiveness. The GAO also slammed the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for failing to make results from Medicaid evaluation reports public in a timely manner.

“CMS is missing an opportunity to inform federal and state policy discussions,” the GAO report said.

Joan Alker, executive director of the Georgetown University Center for Children and Families, called the report’s findings “troubling but not surprising.”

“It has been clear for some time that evaluations of Section 1115 waivers are not adequate,” she said. “There is some good work going on in this space at the state level, for example in Michigan and Iowa, but as the report makes clear state’s evaluations are often incomplete and not rigorous enough.”

These experiments are often called “demonstration projects” or “1115 demonstration waivers” – based on the section of the law that allows the federal government to authorize them. They allow federal officials to approve states’ requests to test new approaches to providing coverage. They are used for a wide variety of purposes, including efforts to extend Medicaid to people or services not generally covered or to change payment systems to improve care.

Medicaid demonstration programs often run for a decade or more. Several states that expanded Medicaid eligibility under the Affordable Care Act did so through a demonstration program, including Indiana, Iowa, Arkansas and New Hampshire.

The study, requested by top GOP lawmakers including Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah), reviewed demonstration programs in eight states – Arizona, Arkansas, California, Indiana, Kansas, Maryland, Massachusetts, and New York.

In five of these states, money from their Medicaid demonstration program makes up more than half their total federal Medicaid budgets. Nearly all of Arizona’s funding – 99.7% – is through a demonstration program.

The use of Medicaid demonstration programs accelerated during the 1990s. But, in recent years, the experiments often have reflected the political leanings of state officials or the party controlling the White House. Under a demonstration program, the Trump administration this year approved requests from Indiana and Kentucky to enact work requirements for some adult Medicaid enrollees.

The GAO report noted that states often do not complete their evaluation reports until after the federal government renews their demonstration program. For example, Indiana’s Medicaid expansion demonstration program, which charges premiums and locks some enrollees out of coverage for lack of payment, was renewed in February even though a final evaluation report is not yet complete.

GAO said Indiana’s evaluation of its Medicaid expansion won’t look at the effect of the state’s provision that locks out enrollees for six months if they fail to pay premiums.

“GAO found that selected states’ evaluations of these demonstrations often had significant limitations that affected their usefulness in informing policy decisions,” the report said.

Ms. Alker said that “more sunshine and data are needed” to assess waivers, “especially as they are clearly the vehicle the Trump administration is now using to pursue its ideological objectives for Medicaid.”

While states typically contract with independent groups to evaluate Medicaid demonstration programs, the federal government sometimes does its own review.

But the GAO investigators found Indiana’s Medicaid agency wasn’t willing to work with the federal contractor out of privacy concerns, which halted efforts for a federal review.

Joel Cantor, director of the Center for State Health Policy at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, N.J., said the demonstration programs often have shifted from their intended purpose because they are designed by lawmakers pushing an agenda rather than as a scientific experiment to find better ways to deliver care.

“Demonstration programs have been used since the 1990s to advance policy agenda for whoever holds power in Washington and not designed to test an innovative idea,” he said.

The evaluations often take several years to complete, he said, because of the difficulty of getting patient data from states. His center has done evaluations for New Jersey’s Medicaid program.

GAO recommended that CMS require states to submit a final evaluation report after the end of the waiver period, regardless of whether the experiment is being renewed, and that the federal agency publicly release findings from federal evaluations in a timely manner. Federal officials said they agreed with the recommendations.

Matt Salo, executive director of the National Association of Medicaid Directors, said the report highlighted a need to modernize the law dealing with Medicaid so that successful experiments are quickly incorporated into the overall program.

“The underlying problem is that the Medicaid statute has fundamentally failed to keep up with the changing reality of health care in the 21st century,” he said. “There’s no way to update the rules to make these changes” a permanent part of the program.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Uninsured rate falls to record low of 8.8%

Three years after the Affordable Care Act’s coverage expansion took effect, the number of Americans without health insurance fell to 28.1 million in 2016, down from 29 million in 2015, according to a federal report released Sept. 12.

The latest numbers from the U.S. Census Bureau showed the nation’s uninsured rate dropped to 8.8%. It had been 9.1% in 2015.

Both the overall number of uninsured and the percentage are record lows.

The latest figures from the Census Bureau effectively close the book on President Barack Obama’s record on lowering the number of uninsured. He made that a linchpin of his 2008 campaign, and his administration’s effort to overhaul the nation’s health system through the ACA focused on expanding coverage.

When Mr. Obama took office in 2009, during the worst economic recession since the Great Depression, more than 50 million Americans were uninsured, or nearly 17% of the population.

The number of uninsured has fallen from 42 million in 2013 – before the ACA in 2014 allowed states to expand Medicaid, the federal-state program that provides coverage to low-income people, and provided federal subsidies to help lower- and middle-income Americans buy coverage on the insurance marketplaces. The decline also reflected the improving economy, which has put more Americans in jobs that offer health coverage.

The dramatic drop in the uninsured over the past few years played a major role in the congressional debate over the summer about whether to replace the 2010 health law. Advocates pleaded with the Republican-controlled Congress not to take steps to reverse the gains in coverage.

The Census Bureau numbers are considered the gold standard for tracking who has insurance because the survey samples are so large.

The uninsured rate has fallen in all 50 states and the District of Columbia since 2013, although the rate has been lower among the 31 states that expanded Medicaid as part of the health law. The lowest uninsured rate last year was 2.5% in Massachusetts, and the highest was 16.6% in Texas, the Census Bureau reported. States that expanded Medicaid had an average uninsured rate of 6.5%, compared with an 11.7% average among states that did not expand.

More than half of Americans – 55.7% – get health insurance through their jobs. But government coverage is becoming more common. Medicaid now covers more than 19% of the population and Medicare, nearly 17%.

Kaiser Health News is a national health policy news service that is part of the nonpartisan Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

Three years after the Affordable Care Act’s coverage expansion took effect, the number of Americans without health insurance fell to 28.1 million in 2016, down from 29 million in 2015, according to a federal report released Sept. 12.

The latest numbers from the U.S. Census Bureau showed the nation’s uninsured rate dropped to 8.8%. It had been 9.1% in 2015.

Both the overall number of uninsured and the percentage are record lows.

The latest figures from the Census Bureau effectively close the book on President Barack Obama’s record on lowering the number of uninsured. He made that a linchpin of his 2008 campaign, and his administration’s effort to overhaul the nation’s health system through the ACA focused on expanding coverage.

When Mr. Obama took office in 2009, during the worst economic recession since the Great Depression, more than 50 million Americans were uninsured, or nearly 17% of the population.

The number of uninsured has fallen from 42 million in 2013 – before the ACA in 2014 allowed states to expand Medicaid, the federal-state program that provides coverage to low-income people, and provided federal subsidies to help lower- and middle-income Americans buy coverage on the insurance marketplaces. The decline also reflected the improving economy, which has put more Americans in jobs that offer health coverage.

The dramatic drop in the uninsured over the past few years played a major role in the congressional debate over the summer about whether to replace the 2010 health law. Advocates pleaded with the Republican-controlled Congress not to take steps to reverse the gains in coverage.

The Census Bureau numbers are considered the gold standard for tracking who has insurance because the survey samples are so large.

The uninsured rate has fallen in all 50 states and the District of Columbia since 2013, although the rate has been lower among the 31 states that expanded Medicaid as part of the health law. The lowest uninsured rate last year was 2.5% in Massachusetts, and the highest was 16.6% in Texas, the Census Bureau reported. States that expanded Medicaid had an average uninsured rate of 6.5%, compared with an 11.7% average among states that did not expand.

More than half of Americans – 55.7% – get health insurance through their jobs. But government coverage is becoming more common. Medicaid now covers more than 19% of the population and Medicare, nearly 17%.

Kaiser Health News is a national health policy news service that is part of the nonpartisan Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

Three years after the Affordable Care Act’s coverage expansion took effect, the number of Americans without health insurance fell to 28.1 million in 2016, down from 29 million in 2015, according to a federal report released Sept. 12.

The latest numbers from the U.S. Census Bureau showed the nation’s uninsured rate dropped to 8.8%. It had been 9.1% in 2015.

Both the overall number of uninsured and the percentage are record lows.

The latest figures from the Census Bureau effectively close the book on President Barack Obama’s record on lowering the number of uninsured. He made that a linchpin of his 2008 campaign, and his administration’s effort to overhaul the nation’s health system through the ACA focused on expanding coverage.

When Mr. Obama took office in 2009, during the worst economic recession since the Great Depression, more than 50 million Americans were uninsured, or nearly 17% of the population.

The number of uninsured has fallen from 42 million in 2013 – before the ACA in 2014 allowed states to expand Medicaid, the federal-state program that provides coverage to low-income people, and provided federal subsidies to help lower- and middle-income Americans buy coverage on the insurance marketplaces. The decline also reflected the improving economy, which has put more Americans in jobs that offer health coverage.

The dramatic drop in the uninsured over the past few years played a major role in the congressional debate over the summer about whether to replace the 2010 health law. Advocates pleaded with the Republican-controlled Congress not to take steps to reverse the gains in coverage.

The Census Bureau numbers are considered the gold standard for tracking who has insurance because the survey samples are so large.

The uninsured rate has fallen in all 50 states and the District of Columbia since 2013, although the rate has been lower among the 31 states that expanded Medicaid as part of the health law. The lowest uninsured rate last year was 2.5% in Massachusetts, and the highest was 16.6% in Texas, the Census Bureau reported. States that expanded Medicaid had an average uninsured rate of 6.5%, compared with an 11.7% average among states that did not expand.

More than half of Americans – 55.7% – get health insurance through their jobs. But government coverage is becoming more common. Medicaid now covers more than 19% of the population and Medicare, nearly 17%.

Kaiser Health News is a national health policy news service that is part of the nonpartisan Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.