User login

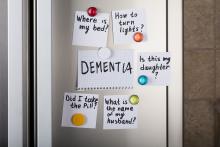

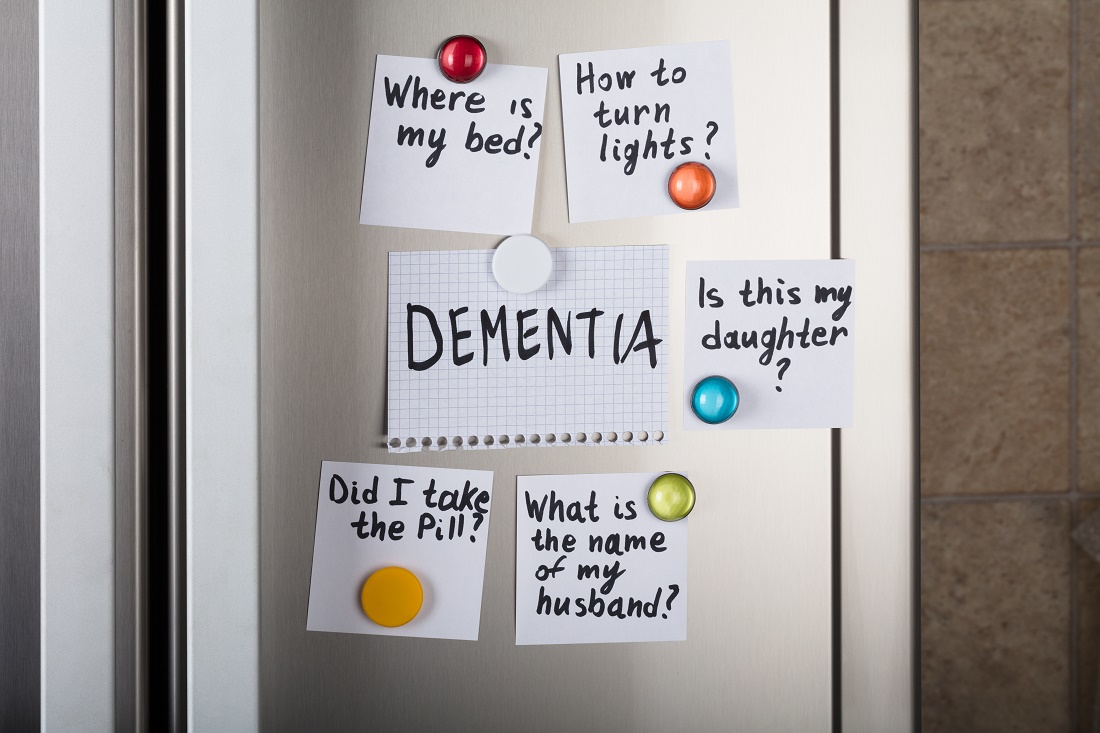

Cannabinoids promising for improving appetite, behavior in dementia

For patients with dementia, cannabinoids may be a promising intervention for treating neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) and the refusing of food, new research suggests.

Results of a systematic literature review, presented at the 2021 meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, showed that cannabinoids were associated with reduced agitation, longer sleep, and lower NPS. They were also linked to increased meal consumption and weight gain.

Refusing food is a common problem for patients with dementia, often resulting in worsening sleep, agitation, and mood, study investigator Niraj Asthana, MD, a second-year resident in the department of psychiatry, University of California, San Diego, said in an interview. Dr. Asthana noted that certain cannabinoid analogues are now used to stimulate appetite for patients undergoing chemotherapy.

Filling a treatment gap

After years of legal and other problems affecting cannabinoid research, there is renewed interest in investigating its use for patients with dementia. Early evidence suggests that cannabinoids may also be beneficial for pain, sleep, and aggression.

The researchers noted that cannabinoids may be especially valuable in areas where there are currently limited therapies, including food refusal and NPS.

“Unfortunately, there are limited treatments available for food refusal, so we’re left with appetite stimulants and electroconvulsive therapy, and although atypical antipsychotics are commonly used to treat NPS, they’re associated with an increased risk of serious adverse events and mortality in older patients,” said Dr. Asthana.

Dr. Asthana and colleague Dan Sewell, MD, carried out a systematic literature review of relevant studies of the use of cannabinoids for dementia patients.

“We found there are lot of studies, but they’re small scale; I’d say the largest was probably about 50 patients, with most studies having 10-50 patients,” said Dr. Asthana. In part, this may be because, until very recently, research on cannabinoids was controversial.

To review the current literature on the potential applications of cannabinoids in the treatment of food refusal and NPS in dementia patients, the researchers conducted a literature review.

They identified 23 relevant studies of the use of synthetic cannabinoids, including dronabinol and nabilone, for dementia patients. These products contain tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the main psychoactive compound in cannabis.

More research coming

Several studies showed that cannabinoid use was associated with reduced nighttime motor activity, improved sleep duration, reduced agitation, and lower Neuropsychiatric Inventory scores.

One crossover placebo-controlled trial showed an overall increase in body weight among dementia patients who took dronabinol.

This suggests there might be something to the “colloquial cultural association between cannabinoids and the munchies,” said Dr. Asthana.

Possible mechanisms for the effects on appetite may be that cannabinoids increase levels of the hormone ghrelin, which is also known as the “hunger hormone,” and decrease leptin levels, a hormone that inhibits hunger. Dr. Asthana noted that, in these studies, the dose of THC was low and that overall, cannabinoids appeared to be safe.

“We found that, at least in these small-scale studies, cannabinoid analogues are well tolerated,” possibly because of the relatively low doses of THC, said Dr. Asthana. “They generally don’t seem to have a ton of side effects; they may make people a little sleepy, which is actually good, because these patents also have a lot of trouble sleeping.”

He noted that more recent research suggests cannabidiol oil may reduce agitation by up to 40%.

“Now that cannabis is losing a lot of its stigma, both culturally and in the scientific community, you’re seeing a lot of grant applications for clinical trials,” said Dr. Asthana. “I’m excited to see what we find in the next 5-10 years.”

In a comment, Kirsten Wilkins, MD, associate professor of psychiatry, Yale University, New Haven, Conn., who is also a geriatric psychiatrist at the Veterans Affairs Connecticut Health Care System, welcomed the new research in this area.

“With limited safe and effective treatments for food refusal and neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia, Dr. Asthana and Dr. Sewell highlight the growing body of literature suggesting cannabinoids may be a novel treatment option,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For patients with dementia, cannabinoids may be a promising intervention for treating neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) and the refusing of food, new research suggests.

Results of a systematic literature review, presented at the 2021 meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, showed that cannabinoids were associated with reduced agitation, longer sleep, and lower NPS. They were also linked to increased meal consumption and weight gain.

Refusing food is a common problem for patients with dementia, often resulting in worsening sleep, agitation, and mood, study investigator Niraj Asthana, MD, a second-year resident in the department of psychiatry, University of California, San Diego, said in an interview. Dr. Asthana noted that certain cannabinoid analogues are now used to stimulate appetite for patients undergoing chemotherapy.

Filling a treatment gap

After years of legal and other problems affecting cannabinoid research, there is renewed interest in investigating its use for patients with dementia. Early evidence suggests that cannabinoids may also be beneficial for pain, sleep, and aggression.

The researchers noted that cannabinoids may be especially valuable in areas where there are currently limited therapies, including food refusal and NPS.

“Unfortunately, there are limited treatments available for food refusal, so we’re left with appetite stimulants and electroconvulsive therapy, and although atypical antipsychotics are commonly used to treat NPS, they’re associated with an increased risk of serious adverse events and mortality in older patients,” said Dr. Asthana.

Dr. Asthana and colleague Dan Sewell, MD, carried out a systematic literature review of relevant studies of the use of cannabinoids for dementia patients.

“We found there are lot of studies, but they’re small scale; I’d say the largest was probably about 50 patients, with most studies having 10-50 patients,” said Dr. Asthana. In part, this may be because, until very recently, research on cannabinoids was controversial.

To review the current literature on the potential applications of cannabinoids in the treatment of food refusal and NPS in dementia patients, the researchers conducted a literature review.

They identified 23 relevant studies of the use of synthetic cannabinoids, including dronabinol and nabilone, for dementia patients. These products contain tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the main psychoactive compound in cannabis.

More research coming

Several studies showed that cannabinoid use was associated with reduced nighttime motor activity, improved sleep duration, reduced agitation, and lower Neuropsychiatric Inventory scores.

One crossover placebo-controlled trial showed an overall increase in body weight among dementia patients who took dronabinol.

This suggests there might be something to the “colloquial cultural association between cannabinoids and the munchies,” said Dr. Asthana.

Possible mechanisms for the effects on appetite may be that cannabinoids increase levels of the hormone ghrelin, which is also known as the “hunger hormone,” and decrease leptin levels, a hormone that inhibits hunger. Dr. Asthana noted that, in these studies, the dose of THC was low and that overall, cannabinoids appeared to be safe.

“We found that, at least in these small-scale studies, cannabinoid analogues are well tolerated,” possibly because of the relatively low doses of THC, said Dr. Asthana. “They generally don’t seem to have a ton of side effects; they may make people a little sleepy, which is actually good, because these patents also have a lot of trouble sleeping.”

He noted that more recent research suggests cannabidiol oil may reduce agitation by up to 40%.

“Now that cannabis is losing a lot of its stigma, both culturally and in the scientific community, you’re seeing a lot of grant applications for clinical trials,” said Dr. Asthana. “I’m excited to see what we find in the next 5-10 years.”

In a comment, Kirsten Wilkins, MD, associate professor of psychiatry, Yale University, New Haven, Conn., who is also a geriatric psychiatrist at the Veterans Affairs Connecticut Health Care System, welcomed the new research in this area.

“With limited safe and effective treatments for food refusal and neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia, Dr. Asthana and Dr. Sewell highlight the growing body of literature suggesting cannabinoids may be a novel treatment option,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For patients with dementia, cannabinoids may be a promising intervention for treating neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) and the refusing of food, new research suggests.

Results of a systematic literature review, presented at the 2021 meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, showed that cannabinoids were associated with reduced agitation, longer sleep, and lower NPS. They were also linked to increased meal consumption and weight gain.

Refusing food is a common problem for patients with dementia, often resulting in worsening sleep, agitation, and mood, study investigator Niraj Asthana, MD, a second-year resident in the department of psychiatry, University of California, San Diego, said in an interview. Dr. Asthana noted that certain cannabinoid analogues are now used to stimulate appetite for patients undergoing chemotherapy.

Filling a treatment gap

After years of legal and other problems affecting cannabinoid research, there is renewed interest in investigating its use for patients with dementia. Early evidence suggests that cannabinoids may also be beneficial for pain, sleep, and aggression.

The researchers noted that cannabinoids may be especially valuable in areas where there are currently limited therapies, including food refusal and NPS.

“Unfortunately, there are limited treatments available for food refusal, so we’re left with appetite stimulants and electroconvulsive therapy, and although atypical antipsychotics are commonly used to treat NPS, they’re associated with an increased risk of serious adverse events and mortality in older patients,” said Dr. Asthana.

Dr. Asthana and colleague Dan Sewell, MD, carried out a systematic literature review of relevant studies of the use of cannabinoids for dementia patients.

“We found there are lot of studies, but they’re small scale; I’d say the largest was probably about 50 patients, with most studies having 10-50 patients,” said Dr. Asthana. In part, this may be because, until very recently, research on cannabinoids was controversial.

To review the current literature on the potential applications of cannabinoids in the treatment of food refusal and NPS in dementia patients, the researchers conducted a literature review.

They identified 23 relevant studies of the use of synthetic cannabinoids, including dronabinol and nabilone, for dementia patients. These products contain tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the main psychoactive compound in cannabis.

More research coming

Several studies showed that cannabinoid use was associated with reduced nighttime motor activity, improved sleep duration, reduced agitation, and lower Neuropsychiatric Inventory scores.

One crossover placebo-controlled trial showed an overall increase in body weight among dementia patients who took dronabinol.

This suggests there might be something to the “colloquial cultural association between cannabinoids and the munchies,” said Dr. Asthana.

Possible mechanisms for the effects on appetite may be that cannabinoids increase levels of the hormone ghrelin, which is also known as the “hunger hormone,” and decrease leptin levels, a hormone that inhibits hunger. Dr. Asthana noted that, in these studies, the dose of THC was low and that overall, cannabinoids appeared to be safe.

“We found that, at least in these small-scale studies, cannabinoid analogues are well tolerated,” possibly because of the relatively low doses of THC, said Dr. Asthana. “They generally don’t seem to have a ton of side effects; they may make people a little sleepy, which is actually good, because these patents also have a lot of trouble sleeping.”

He noted that more recent research suggests cannabidiol oil may reduce agitation by up to 40%.

“Now that cannabis is losing a lot of its stigma, both culturally and in the scientific community, you’re seeing a lot of grant applications for clinical trials,” said Dr. Asthana. “I’m excited to see what we find in the next 5-10 years.”

In a comment, Kirsten Wilkins, MD, associate professor of psychiatry, Yale University, New Haven, Conn., who is also a geriatric psychiatrist at the Veterans Affairs Connecticut Health Care System, welcomed the new research in this area.

“With limited safe and effective treatments for food refusal and neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia, Dr. Asthana and Dr. Sewell highlight the growing body of literature suggesting cannabinoids may be a novel treatment option,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Traumatic brain injury tied to long-term sleep problems

Veterans who have suffered a traumatic brain injury (TBI) are significantly more likely to develop insomnia and other sleep problems years later compared to their counterparts who have not suffered a brain injury, a new study shows.

Results of a large longitudinal study show that those with TBI were about 40% more likely to develop insomnia, sleep apnea, excessive daytime sleepiness, or another sleep disorder in later years, after adjusting for demographics and medical and psychiatric conditions.

Interestingly, the association with sleep disorders was strongest among those with mild TBI versus a more severe brain injury.

The study showed that the risk for sleep disorders increased up to 14 years after a brain injury, an indicator that “clinicians should really pay attention to sleep disorders in TBI patients both in the short term and the long term,” study investigator Yue Leng, MD, PhD, assistant professor, department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, University of California, San Francisco, told this news organization.

The study was published online March 3 in Neurology.

First long-term look

TBI is common among veterans, who may have sleep complaints or psychiatric symptoms, but previous studies into the consequences of TBI have examined the short- vs. long-term impact, said Dr. Leng.

To examine the longitudinal association between TBI and sleep disorders, the investigators examined data on 98,709 Veterans Health Administration patients diagnosed with TBI and an age-matched group of the same number of veterans who had not received such a diagnosis. The mean age of the participants was 49 years at baseline, and 11.7% were women. Of the TBI cases, 49.6% were mild.

Researchers used an exposure survey and diagnostic codes to establish TBI and its severity.

Patients with TBI were more likely to be male and were much more likely to have a psychiatric condition, such as a mood disorder (22.4% vs. 9.3%), anxiety (10.5% vs. 4.4%), posttraumatic stress disorder (19.5% vs. 4.4%), or substance abuse (11.4% vs. 5.2%). They were also more likely to smoke or use tobacco (13.5% vs. 8.7%).

Researchers assessed a number of sleep disorders, including insomnia, hypersomnia disorders, narcolepsy, sleep-related breathing disorders, and sleep-related movement disorders.

During a follow-up period that averaged 5 years but ranged up to 14 years, 23.4% of veterans with TBI and 15.8% of those without TBI developed a sleep disorder.

After adjusting for age, sex, race, education, and income, those who had suffered a TBI were 50% more likely to develop any sleep disorder, compared with those who had not had a TBI (hazard ratio, 1.50; 95% confidence interval, 1.47-1.53.)

After controlling for medical conditions that included diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction, and cerebrovascular disease, as well as psychiatric disorders such as mood disorders, anxiety, PTSD, substance use disorder, and tobacco use, the HR for developing a sleep disorder was 1.41 (95% CI, 1.37-1.44).

The association with TBI was stronger for some sleep disorders. Adjusted HRs were 1.50 (95% CI, 1.45-1.55) for insomnia, 1.50 (95% CI, 1.39-1.61) for hypersomnia, 1.33 (95% CI, 1.16-1.52) for sleep-related movement disorders, and 1.28 (95% CI, 1.24-1.32) for sleep apnea.

It’s unclear what causes postinjury sleep problems, but it could be that TBI induces structural brain damage, or it could affect melatonin secretion or wake-promoting neurons.

Damage to arousal-promoting neurons could help explain the reason the link between TBI and sleep disorders was strongest for insomnia and hypersomnia, although the exact mechanism is unclear, said Dr. Leng.

Greater risk with mild TBI

Overall, the association was stronger for mild TBI than for moderate to severe TBI. This, said Dr. Leng, might be because of differences in the brain injury mechanism.

Mild TBI often involves repetitive concussive or subconcussive injuries, such as sports injuries or blast injury among active-duty military personnel. This type of injury is more likely to cause diffuse axonal injury and inflammation, whereas moderate or severe TBI is often attributable to a direct blow with more focal but severe damage, explained Dr. Leng.

She noted that veterans with mild TBI were more likely to have a psychiatric condition, but because the study controlled for such conditions, this doesn’t fully explain the stronger association between mild TBI and sleep disorders.

Further studies are needed to sort out the exact mechanisms, she said.

The association between TBI and risk for sleep disorders was reduced somewhat but was still moderate in an analysis that excluded patients who developed a sleep disorder within 2 years of a brain injury.

This analysis, said Dr. Leng, helped ensure that the sleep disorder developed after the brain injury.

The researchers could not examine the trajectory of sleep problems, so it’s not clear whether sleep problems worsen or get better over time, said Dr. Leng.

Because PTSD also leads to sleep problems, the researchers thought that having both PTSD and TBI might increase the risk for sleep problems. “But actually we found the association was pretty similar in those with, and without, PTSD, so that was kind of contrary to our hypothesis,” she said.

The new results underline the need for more screening for sleep disorders among patients with TBI, both in the short term and the long term, said Dr. Leng. “Clinicians should ask TBI patients about their sleep, and they should follow that up,” she said.

She added that long-term sleep disorders can affect a patient’s health and can lead to psychiatric problems and neurodegenerative diseases.

Depending on the type of sleep disorder, there are a number of possible treatments. For example, for patients with sleep apnea, continuous positive airway pressure treatment may be considered.

‘Outstanding’ research

Commenting for this news organization, Frank Conidi, MD, director, Florida Center for Headache and Sports Neurology; CEO, Brainsport, Team Neurologist, the Florida Panthers of the National Hockey League; and past president, Florida Society of Neurology, said the study is “by far” the largest to investigate the correlation between sleep disorders and head trauma.

The design and outcome measures “were well thought out,” and the researchers “did an outstanding job in sorting through and analyzing the data,” said Dr. Conidi.

He added that he was particularly impressed with how the researchers addressed PTSD, which is highly prevalent among veterans with head trauma and is known to affect sleep.

The new results “solidify what those of us who see individuals with TBI have observed over the years: that there is a higher incidence of all types of sleep disorders” in individuals with a TBI, said Dr. Conidi.

However, he questioned the study’s use of guidelines to classify the various types of head trauma. These guidelines, he said, “are based on loss of consciousness, which we have started to move away from when classifying TBI.”

In addition, Dr. Conidi said he “would have loved to have seen” some correlation with neuroimaging studies, such as those used to assess subdural hematoma, epidural hematoma, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and diffuse axonal injury, but that this “could be an impetus for future studies.”

In “a perfect world,” all patients with a TBI would undergo a polysomnography study in a sleep laboratory, but insurance companies now rarely cover such studies and have attempted to have clinicians shift to home sleep studies, said Dr. Conidi. “These are marginal at best for screening for sleep disorders,” he noted.

At his centers, every TBI patient is screened for sleep disorders and, whenever possible, undergoes formal evaluation in the sleep lab, he added.

The study was supported by the U.S. Army Medical Research and Material Command and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Leng and Dr. Conidi have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Veterans who have suffered a traumatic brain injury (TBI) are significantly more likely to develop insomnia and other sleep problems years later compared to their counterparts who have not suffered a brain injury, a new study shows.

Results of a large longitudinal study show that those with TBI were about 40% more likely to develop insomnia, sleep apnea, excessive daytime sleepiness, or another sleep disorder in later years, after adjusting for demographics and medical and psychiatric conditions.

Interestingly, the association with sleep disorders was strongest among those with mild TBI versus a more severe brain injury.

The study showed that the risk for sleep disorders increased up to 14 years after a brain injury, an indicator that “clinicians should really pay attention to sleep disorders in TBI patients both in the short term and the long term,” study investigator Yue Leng, MD, PhD, assistant professor, department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, University of California, San Francisco, told this news organization.

The study was published online March 3 in Neurology.

First long-term look

TBI is common among veterans, who may have sleep complaints or psychiatric symptoms, but previous studies into the consequences of TBI have examined the short- vs. long-term impact, said Dr. Leng.

To examine the longitudinal association between TBI and sleep disorders, the investigators examined data on 98,709 Veterans Health Administration patients diagnosed with TBI and an age-matched group of the same number of veterans who had not received such a diagnosis. The mean age of the participants was 49 years at baseline, and 11.7% were women. Of the TBI cases, 49.6% were mild.

Researchers used an exposure survey and diagnostic codes to establish TBI and its severity.

Patients with TBI were more likely to be male and were much more likely to have a psychiatric condition, such as a mood disorder (22.4% vs. 9.3%), anxiety (10.5% vs. 4.4%), posttraumatic stress disorder (19.5% vs. 4.4%), or substance abuse (11.4% vs. 5.2%). They were also more likely to smoke or use tobacco (13.5% vs. 8.7%).

Researchers assessed a number of sleep disorders, including insomnia, hypersomnia disorders, narcolepsy, sleep-related breathing disorders, and sleep-related movement disorders.

During a follow-up period that averaged 5 years but ranged up to 14 years, 23.4% of veterans with TBI and 15.8% of those without TBI developed a sleep disorder.

After adjusting for age, sex, race, education, and income, those who had suffered a TBI were 50% more likely to develop any sleep disorder, compared with those who had not had a TBI (hazard ratio, 1.50; 95% confidence interval, 1.47-1.53.)

After controlling for medical conditions that included diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction, and cerebrovascular disease, as well as psychiatric disorders such as mood disorders, anxiety, PTSD, substance use disorder, and tobacco use, the HR for developing a sleep disorder was 1.41 (95% CI, 1.37-1.44).

The association with TBI was stronger for some sleep disorders. Adjusted HRs were 1.50 (95% CI, 1.45-1.55) for insomnia, 1.50 (95% CI, 1.39-1.61) for hypersomnia, 1.33 (95% CI, 1.16-1.52) for sleep-related movement disorders, and 1.28 (95% CI, 1.24-1.32) for sleep apnea.

It’s unclear what causes postinjury sleep problems, but it could be that TBI induces structural brain damage, or it could affect melatonin secretion or wake-promoting neurons.

Damage to arousal-promoting neurons could help explain the reason the link between TBI and sleep disorders was strongest for insomnia and hypersomnia, although the exact mechanism is unclear, said Dr. Leng.

Greater risk with mild TBI

Overall, the association was stronger for mild TBI than for moderate to severe TBI. This, said Dr. Leng, might be because of differences in the brain injury mechanism.

Mild TBI often involves repetitive concussive or subconcussive injuries, such as sports injuries or blast injury among active-duty military personnel. This type of injury is more likely to cause diffuse axonal injury and inflammation, whereas moderate or severe TBI is often attributable to a direct blow with more focal but severe damage, explained Dr. Leng.

She noted that veterans with mild TBI were more likely to have a psychiatric condition, but because the study controlled for such conditions, this doesn’t fully explain the stronger association between mild TBI and sleep disorders.

Further studies are needed to sort out the exact mechanisms, she said.

The association between TBI and risk for sleep disorders was reduced somewhat but was still moderate in an analysis that excluded patients who developed a sleep disorder within 2 years of a brain injury.

This analysis, said Dr. Leng, helped ensure that the sleep disorder developed after the brain injury.

The researchers could not examine the trajectory of sleep problems, so it’s not clear whether sleep problems worsen or get better over time, said Dr. Leng.

Because PTSD also leads to sleep problems, the researchers thought that having both PTSD and TBI might increase the risk for sleep problems. “But actually we found the association was pretty similar in those with, and without, PTSD, so that was kind of contrary to our hypothesis,” she said.

The new results underline the need for more screening for sleep disorders among patients with TBI, both in the short term and the long term, said Dr. Leng. “Clinicians should ask TBI patients about their sleep, and they should follow that up,” she said.

She added that long-term sleep disorders can affect a patient’s health and can lead to psychiatric problems and neurodegenerative diseases.

Depending on the type of sleep disorder, there are a number of possible treatments. For example, for patients with sleep apnea, continuous positive airway pressure treatment may be considered.

‘Outstanding’ research

Commenting for this news organization, Frank Conidi, MD, director, Florida Center for Headache and Sports Neurology; CEO, Brainsport, Team Neurologist, the Florida Panthers of the National Hockey League; and past president, Florida Society of Neurology, said the study is “by far” the largest to investigate the correlation between sleep disorders and head trauma.

The design and outcome measures “were well thought out,” and the researchers “did an outstanding job in sorting through and analyzing the data,” said Dr. Conidi.

He added that he was particularly impressed with how the researchers addressed PTSD, which is highly prevalent among veterans with head trauma and is known to affect sleep.

The new results “solidify what those of us who see individuals with TBI have observed over the years: that there is a higher incidence of all types of sleep disorders” in individuals with a TBI, said Dr. Conidi.

However, he questioned the study’s use of guidelines to classify the various types of head trauma. These guidelines, he said, “are based on loss of consciousness, which we have started to move away from when classifying TBI.”

In addition, Dr. Conidi said he “would have loved to have seen” some correlation with neuroimaging studies, such as those used to assess subdural hematoma, epidural hematoma, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and diffuse axonal injury, but that this “could be an impetus for future studies.”

In “a perfect world,” all patients with a TBI would undergo a polysomnography study in a sleep laboratory, but insurance companies now rarely cover such studies and have attempted to have clinicians shift to home sleep studies, said Dr. Conidi. “These are marginal at best for screening for sleep disorders,” he noted.

At his centers, every TBI patient is screened for sleep disorders and, whenever possible, undergoes formal evaluation in the sleep lab, he added.

The study was supported by the U.S. Army Medical Research and Material Command and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Leng and Dr. Conidi have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Veterans who have suffered a traumatic brain injury (TBI) are significantly more likely to develop insomnia and other sleep problems years later compared to their counterparts who have not suffered a brain injury, a new study shows.

Results of a large longitudinal study show that those with TBI were about 40% more likely to develop insomnia, sleep apnea, excessive daytime sleepiness, or another sleep disorder in later years, after adjusting for demographics and medical and psychiatric conditions.

Interestingly, the association with sleep disorders was strongest among those with mild TBI versus a more severe brain injury.

The study showed that the risk for sleep disorders increased up to 14 years after a brain injury, an indicator that “clinicians should really pay attention to sleep disorders in TBI patients both in the short term and the long term,” study investigator Yue Leng, MD, PhD, assistant professor, department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, University of California, San Francisco, told this news organization.

The study was published online March 3 in Neurology.

First long-term look

TBI is common among veterans, who may have sleep complaints or psychiatric symptoms, but previous studies into the consequences of TBI have examined the short- vs. long-term impact, said Dr. Leng.

To examine the longitudinal association between TBI and sleep disorders, the investigators examined data on 98,709 Veterans Health Administration patients diagnosed with TBI and an age-matched group of the same number of veterans who had not received such a diagnosis. The mean age of the participants was 49 years at baseline, and 11.7% were women. Of the TBI cases, 49.6% were mild.

Researchers used an exposure survey and diagnostic codes to establish TBI and its severity.

Patients with TBI were more likely to be male and were much more likely to have a psychiatric condition, such as a mood disorder (22.4% vs. 9.3%), anxiety (10.5% vs. 4.4%), posttraumatic stress disorder (19.5% vs. 4.4%), or substance abuse (11.4% vs. 5.2%). They were also more likely to smoke or use tobacco (13.5% vs. 8.7%).

Researchers assessed a number of sleep disorders, including insomnia, hypersomnia disorders, narcolepsy, sleep-related breathing disorders, and sleep-related movement disorders.

During a follow-up period that averaged 5 years but ranged up to 14 years, 23.4% of veterans with TBI and 15.8% of those without TBI developed a sleep disorder.

After adjusting for age, sex, race, education, and income, those who had suffered a TBI were 50% more likely to develop any sleep disorder, compared with those who had not had a TBI (hazard ratio, 1.50; 95% confidence interval, 1.47-1.53.)

After controlling for medical conditions that included diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction, and cerebrovascular disease, as well as psychiatric disorders such as mood disorders, anxiety, PTSD, substance use disorder, and tobacco use, the HR for developing a sleep disorder was 1.41 (95% CI, 1.37-1.44).

The association with TBI was stronger for some sleep disorders. Adjusted HRs were 1.50 (95% CI, 1.45-1.55) for insomnia, 1.50 (95% CI, 1.39-1.61) for hypersomnia, 1.33 (95% CI, 1.16-1.52) for sleep-related movement disorders, and 1.28 (95% CI, 1.24-1.32) for sleep apnea.

It’s unclear what causes postinjury sleep problems, but it could be that TBI induces structural brain damage, or it could affect melatonin secretion or wake-promoting neurons.

Damage to arousal-promoting neurons could help explain the reason the link between TBI and sleep disorders was strongest for insomnia and hypersomnia, although the exact mechanism is unclear, said Dr. Leng.

Greater risk with mild TBI

Overall, the association was stronger for mild TBI than for moderate to severe TBI. This, said Dr. Leng, might be because of differences in the brain injury mechanism.

Mild TBI often involves repetitive concussive or subconcussive injuries, such as sports injuries or blast injury among active-duty military personnel. This type of injury is more likely to cause diffuse axonal injury and inflammation, whereas moderate or severe TBI is often attributable to a direct blow with more focal but severe damage, explained Dr. Leng.

She noted that veterans with mild TBI were more likely to have a psychiatric condition, but because the study controlled for such conditions, this doesn’t fully explain the stronger association between mild TBI and sleep disorders.

Further studies are needed to sort out the exact mechanisms, she said.

The association between TBI and risk for sleep disorders was reduced somewhat but was still moderate in an analysis that excluded patients who developed a sleep disorder within 2 years of a brain injury.

This analysis, said Dr. Leng, helped ensure that the sleep disorder developed after the brain injury.

The researchers could not examine the trajectory of sleep problems, so it’s not clear whether sleep problems worsen or get better over time, said Dr. Leng.

Because PTSD also leads to sleep problems, the researchers thought that having both PTSD and TBI might increase the risk for sleep problems. “But actually we found the association was pretty similar in those with, and without, PTSD, so that was kind of contrary to our hypothesis,” she said.

The new results underline the need for more screening for sleep disorders among patients with TBI, both in the short term and the long term, said Dr. Leng. “Clinicians should ask TBI patients about their sleep, and they should follow that up,” she said.

She added that long-term sleep disorders can affect a patient’s health and can lead to psychiatric problems and neurodegenerative diseases.

Depending on the type of sleep disorder, there are a number of possible treatments. For example, for patients with sleep apnea, continuous positive airway pressure treatment may be considered.

‘Outstanding’ research

Commenting for this news organization, Frank Conidi, MD, director, Florida Center for Headache and Sports Neurology; CEO, Brainsport, Team Neurologist, the Florida Panthers of the National Hockey League; and past president, Florida Society of Neurology, said the study is “by far” the largest to investigate the correlation between sleep disorders and head trauma.

The design and outcome measures “were well thought out,” and the researchers “did an outstanding job in sorting through and analyzing the data,” said Dr. Conidi.

He added that he was particularly impressed with how the researchers addressed PTSD, which is highly prevalent among veterans with head trauma and is known to affect sleep.

The new results “solidify what those of us who see individuals with TBI have observed over the years: that there is a higher incidence of all types of sleep disorders” in individuals with a TBI, said Dr. Conidi.

However, he questioned the study’s use of guidelines to classify the various types of head trauma. These guidelines, he said, “are based on loss of consciousness, which we have started to move away from when classifying TBI.”

In addition, Dr. Conidi said he “would have loved to have seen” some correlation with neuroimaging studies, such as those used to assess subdural hematoma, epidural hematoma, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and diffuse axonal injury, but that this “could be an impetus for future studies.”

In “a perfect world,” all patients with a TBI would undergo a polysomnography study in a sleep laboratory, but insurance companies now rarely cover such studies and have attempted to have clinicians shift to home sleep studies, said Dr. Conidi. “These are marginal at best for screening for sleep disorders,” he noted.

At his centers, every TBI patient is screened for sleep disorders and, whenever possible, undergoes formal evaluation in the sleep lab, he added.

The study was supported by the U.S. Army Medical Research and Material Command and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Leng and Dr. Conidi have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Sleep apnea and cognitive impairment are common bedfellows

“The study shows obstructive sleep apnea is common in patients with cognitive impairment. The results suggest that people with cognitive impairment should be assessed for sleep apnea if they have difficulty with sleep or if they demonstrate sleep-related symptoms,” said study investigator David Colelli, MSc, research coordinator at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto.

The findings were released ahead of the study’s scheduled presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology..

Linked to cognitive impairment

OSA is a common sleep disorder and is associated with an increased risk of developing cognitive impairment. It is also prevalent in the general population, but even more common among patients with dementia.

However, the investigators noted, the frequency and predictors of OSA have not been well established in Alzheimer’s disease and other related conditions such as vascular dementia.

The investigators had conducted a previous feasibility study investigating a home sleep monitor as an OSA screening tool. The current research examined potential correlations between OSA detected by this monitor and cognitive impairment.

The study included 67 patients with cognitive impairment due to neurodegenerative or vascular disease. The range of disorders included Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment caused by Alzheimer’s disease, dementia caused by Parkinson’s or Lewy body disease, and vascular conditions.

Participants had a mean age of 72.8 years and 44.8% were male. The mean body mass index (BMI) was 25.6 kg/m2.

These participants completed a home sleep apnea test, which is an alternative to polysomnography for the detection of OSA.

Researchers identified OSA in 52.2% of the study population. This, Mr. Colelli said, “is in the range” of other research investigating sleep and cognitive impairment.

“In the general population, however, this number is a lot lower – in the 10%-20% range depending on the population or country you’re looking at,” Mr. Colelli said.

He emphasized that, without an objective sleep test, some patients may be unaware of their sleep issues. Those with cognitive impairment may “misjudge how they’re sleeping,” especially if they sleep without a partner, so it’s possible that sleep disorder symptoms often go undetected.

Bidirectional relationship?

Participants answered questionnaires on sleep, cognition, and mood. They also completed the 30-point Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) to assess language, visuospatial abilities, memory and recall, and abstract thinking.

Scores on this test range from 0 to 30, with a score of 26 or higher signifying normal, 18-25 indicating mild cognitive impairment, and 17 or lower indicating moderate to severe cognitive impairment. The average score for study participants with OSA was 20.5, compared with 23.6 for those without the sleep disorder.

Results showed OSA was significantly associated with a lower score on the MoCA scale (odds ratio, 0.40; P = .048). “This demonstrated an association of OSA with lower cognitive scores,” Mr. Colelli said.

The analysis also showed that OSA severity was correlated with actigraphy-derived sleep variables, including lower total sleep time, greater sleep onset latency, lower sleep efficiency, and more awakenings.

The study was too small to determine whether a specific diagnosis of cognitive impairment affected the link to OSA, Mr. Colelli said. “But definitely future research should be directed towards looking at this.”

Obesity is a risk factor for OSA, but the mean BMI in the study was not in the obese range of 30 and over. This, Mr. Colelli said, suggests that sleep apnea may present differently in those with cognitive impairment.

“Sleep apnea in this population might not present with the typical risk factors of obesity or snoring or feeling tired.”

While the new study “adds to the understanding that there’s a link between sleep and cognitive impairment, the direction of that link isn’t entirely clear,” Mr. Colelli said.

“It’s slowly becoming appreciated that the relationship might be bidirectionality, where sleep apnea might be contributing to the cognitive impairment and cognitive impairment could be contributing to the sleep issues.”

The study highlights how essential sleep is to mental health, Mr. Colelli said. “I feel, and I’m sure you do too, that if you don’t get good sleep, you feel tired during the day and you may not have the best concentration or memory.”

Identifying sleep issues in patients with cognitive impairment is important, as treatment and management of these issues could affect outcomes including cognition and quality of life, he added.

“Future research should be directed to see if treatment of sleep disorders with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), which is the gold standard, and various other treatments, can improve outcomes.” Future research should also examine OSA prevalence in larger cohorts.

Common, undertreated

Commenting on the resaerch, Lei Gao, MD, assistant professor of anesthesia at Harvard Medical School, Boston, whose areas of expertise include disorders of cognition, sleep, and circadian rhythm, believes the findings are important. “It highlights how common and potentially undertreated OSA is in this age group, and in particular, its link to cognitive impairment.”

OSA is often associated with significant comorbidities, as well as sleep disruption, Dr. Gao noted. One of the study’s strengths was including objective assessment of sleep using actigraphy. “It will be interesting to see to what extent the OSA link to cognitive impairment is via poor sleep or disrupted circadian rest/activity cycles.”

It would also be interesting “to tease out whether OSA is more linked to dementia of vascular etiologies due to common risk factors, or whether it is pervasive to all forms of dementia,” he added.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“The study shows obstructive sleep apnea is common in patients with cognitive impairment. The results suggest that people with cognitive impairment should be assessed for sleep apnea if they have difficulty with sleep or if they demonstrate sleep-related symptoms,” said study investigator David Colelli, MSc, research coordinator at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto.

The findings were released ahead of the study’s scheduled presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology..

Linked to cognitive impairment

OSA is a common sleep disorder and is associated with an increased risk of developing cognitive impairment. It is also prevalent in the general population, but even more common among patients with dementia.

However, the investigators noted, the frequency and predictors of OSA have not been well established in Alzheimer’s disease and other related conditions such as vascular dementia.

The investigators had conducted a previous feasibility study investigating a home sleep monitor as an OSA screening tool. The current research examined potential correlations between OSA detected by this monitor and cognitive impairment.

The study included 67 patients with cognitive impairment due to neurodegenerative or vascular disease. The range of disorders included Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment caused by Alzheimer’s disease, dementia caused by Parkinson’s or Lewy body disease, and vascular conditions.

Participants had a mean age of 72.8 years and 44.8% were male. The mean body mass index (BMI) was 25.6 kg/m2.

These participants completed a home sleep apnea test, which is an alternative to polysomnography for the detection of OSA.

Researchers identified OSA in 52.2% of the study population. This, Mr. Colelli said, “is in the range” of other research investigating sleep and cognitive impairment.

“In the general population, however, this number is a lot lower – in the 10%-20% range depending on the population or country you’re looking at,” Mr. Colelli said.

He emphasized that, without an objective sleep test, some patients may be unaware of their sleep issues. Those with cognitive impairment may “misjudge how they’re sleeping,” especially if they sleep without a partner, so it’s possible that sleep disorder symptoms often go undetected.

Bidirectional relationship?

Participants answered questionnaires on sleep, cognition, and mood. They also completed the 30-point Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) to assess language, visuospatial abilities, memory and recall, and abstract thinking.

Scores on this test range from 0 to 30, with a score of 26 or higher signifying normal, 18-25 indicating mild cognitive impairment, and 17 or lower indicating moderate to severe cognitive impairment. The average score for study participants with OSA was 20.5, compared with 23.6 for those without the sleep disorder.

Results showed OSA was significantly associated with a lower score on the MoCA scale (odds ratio, 0.40; P = .048). “This demonstrated an association of OSA with lower cognitive scores,” Mr. Colelli said.

The analysis also showed that OSA severity was correlated with actigraphy-derived sleep variables, including lower total sleep time, greater sleep onset latency, lower sleep efficiency, and more awakenings.

The study was too small to determine whether a specific diagnosis of cognitive impairment affected the link to OSA, Mr. Colelli said. “But definitely future research should be directed towards looking at this.”

Obesity is a risk factor for OSA, but the mean BMI in the study was not in the obese range of 30 and over. This, Mr. Colelli said, suggests that sleep apnea may present differently in those with cognitive impairment.

“Sleep apnea in this population might not present with the typical risk factors of obesity or snoring or feeling tired.”

While the new study “adds to the understanding that there’s a link between sleep and cognitive impairment, the direction of that link isn’t entirely clear,” Mr. Colelli said.

“It’s slowly becoming appreciated that the relationship might be bidirectionality, where sleep apnea might be contributing to the cognitive impairment and cognitive impairment could be contributing to the sleep issues.”

The study highlights how essential sleep is to mental health, Mr. Colelli said. “I feel, and I’m sure you do too, that if you don’t get good sleep, you feel tired during the day and you may not have the best concentration or memory.”

Identifying sleep issues in patients with cognitive impairment is important, as treatment and management of these issues could affect outcomes including cognition and quality of life, he added.

“Future research should be directed to see if treatment of sleep disorders with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), which is the gold standard, and various other treatments, can improve outcomes.” Future research should also examine OSA prevalence in larger cohorts.

Common, undertreated

Commenting on the resaerch, Lei Gao, MD, assistant professor of anesthesia at Harvard Medical School, Boston, whose areas of expertise include disorders of cognition, sleep, and circadian rhythm, believes the findings are important. “It highlights how common and potentially undertreated OSA is in this age group, and in particular, its link to cognitive impairment.”

OSA is often associated with significant comorbidities, as well as sleep disruption, Dr. Gao noted. One of the study’s strengths was including objective assessment of sleep using actigraphy. “It will be interesting to see to what extent the OSA link to cognitive impairment is via poor sleep or disrupted circadian rest/activity cycles.”

It would also be interesting “to tease out whether OSA is more linked to dementia of vascular etiologies due to common risk factors, or whether it is pervasive to all forms of dementia,” he added.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“The study shows obstructive sleep apnea is common in patients with cognitive impairment. The results suggest that people with cognitive impairment should be assessed for sleep apnea if they have difficulty with sleep or if they demonstrate sleep-related symptoms,” said study investigator David Colelli, MSc, research coordinator at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto.

The findings were released ahead of the study’s scheduled presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology..

Linked to cognitive impairment

OSA is a common sleep disorder and is associated with an increased risk of developing cognitive impairment. It is also prevalent in the general population, but even more common among patients with dementia.

However, the investigators noted, the frequency and predictors of OSA have not been well established in Alzheimer’s disease and other related conditions such as vascular dementia.

The investigators had conducted a previous feasibility study investigating a home sleep monitor as an OSA screening tool. The current research examined potential correlations between OSA detected by this monitor and cognitive impairment.

The study included 67 patients with cognitive impairment due to neurodegenerative or vascular disease. The range of disorders included Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment caused by Alzheimer’s disease, dementia caused by Parkinson’s or Lewy body disease, and vascular conditions.

Participants had a mean age of 72.8 years and 44.8% were male. The mean body mass index (BMI) was 25.6 kg/m2.

These participants completed a home sleep apnea test, which is an alternative to polysomnography for the detection of OSA.

Researchers identified OSA in 52.2% of the study population. This, Mr. Colelli said, “is in the range” of other research investigating sleep and cognitive impairment.

“In the general population, however, this number is a lot lower – in the 10%-20% range depending on the population or country you’re looking at,” Mr. Colelli said.

He emphasized that, without an objective sleep test, some patients may be unaware of their sleep issues. Those with cognitive impairment may “misjudge how they’re sleeping,” especially if they sleep without a partner, so it’s possible that sleep disorder symptoms often go undetected.

Bidirectional relationship?

Participants answered questionnaires on sleep, cognition, and mood. They also completed the 30-point Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) to assess language, visuospatial abilities, memory and recall, and abstract thinking.

Scores on this test range from 0 to 30, with a score of 26 or higher signifying normal, 18-25 indicating mild cognitive impairment, and 17 or lower indicating moderate to severe cognitive impairment. The average score for study participants with OSA was 20.5, compared with 23.6 for those without the sleep disorder.

Results showed OSA was significantly associated with a lower score on the MoCA scale (odds ratio, 0.40; P = .048). “This demonstrated an association of OSA with lower cognitive scores,” Mr. Colelli said.

The analysis also showed that OSA severity was correlated with actigraphy-derived sleep variables, including lower total sleep time, greater sleep onset latency, lower sleep efficiency, and more awakenings.

The study was too small to determine whether a specific diagnosis of cognitive impairment affected the link to OSA, Mr. Colelli said. “But definitely future research should be directed towards looking at this.”

Obesity is a risk factor for OSA, but the mean BMI in the study was not in the obese range of 30 and over. This, Mr. Colelli said, suggests that sleep apnea may present differently in those with cognitive impairment.

“Sleep apnea in this population might not present with the typical risk factors of obesity or snoring or feeling tired.”

While the new study “adds to the understanding that there’s a link between sleep and cognitive impairment, the direction of that link isn’t entirely clear,” Mr. Colelli said.

“It’s slowly becoming appreciated that the relationship might be bidirectionality, where sleep apnea might be contributing to the cognitive impairment and cognitive impairment could be contributing to the sleep issues.”

The study highlights how essential sleep is to mental health, Mr. Colelli said. “I feel, and I’m sure you do too, that if you don’t get good sleep, you feel tired during the day and you may not have the best concentration or memory.”

Identifying sleep issues in patients with cognitive impairment is important, as treatment and management of these issues could affect outcomes including cognition and quality of life, he added.

“Future research should be directed to see if treatment of sleep disorders with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), which is the gold standard, and various other treatments, can improve outcomes.” Future research should also examine OSA prevalence in larger cohorts.

Common, undertreated

Commenting on the resaerch, Lei Gao, MD, assistant professor of anesthesia at Harvard Medical School, Boston, whose areas of expertise include disorders of cognition, sleep, and circadian rhythm, believes the findings are important. “It highlights how common and potentially undertreated OSA is in this age group, and in particular, its link to cognitive impairment.”

OSA is often associated with significant comorbidities, as well as sleep disruption, Dr. Gao noted. One of the study’s strengths was including objective assessment of sleep using actigraphy. “It will be interesting to see to what extent the OSA link to cognitive impairment is via poor sleep or disrupted circadian rest/activity cycles.”

It would also be interesting “to tease out whether OSA is more linked to dementia of vascular etiologies due to common risk factors, or whether it is pervasive to all forms of dementia,” he added.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AAN 2021

‘Landmark’ schizophrenia drug in the wings?

A novel therapy that combines a muscarinic receptor agonist with an anticholinergic agent is associated with a greater reduction in psychosis symptoms, compared with placebo, new research shows.

In a randomized, phase 2 trial composed of nearly 200 participants, xanomeline-trospium (KarXT) was generally well tolerated and had none of the common side effects linked to current antipsychotics, including weight gain and extrapyramidal symptoms such as dystonia, parkinsonism, and tardive dyskinesia.

“The results showing robust therapeutic efficacy of a non–dopamine targeting antipsychotic drug is an important milestone in the advance of the therapeutics of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders,” coinvestigator Jeffrey A. Lieberman, MD, professor and chairman in the department of psychiatry, Columbia University, New York, said in an interview.

If approved, the new agent will be a “landmark” drug, Dr. Lieberman added.

The study was published in the Feb. 25, 2021, issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.

Long journey

The journey to develop an effective schizophrenia drug that reduces psychosis symptoms without onerous side effects has been a long one full of excitement and disappointment.

First-generation antipsychotics, dating back to the 1950s, targeted the postsynaptic dopamine-2 (D2) receptor. At the time, it was a “breakthrough” similar in scope to insulin for diabetes or antibiotics for infections, said Dr. Lieberman.

That was followed by development of numerous “me too” drugs with the same mechanism of action. However, these drugs had significant side effects, especially neurologic adverse events such as parkinsonism.

In 1989, second-generation antipsychotics were introduced, beginning with clozapine. They still targeted the D2 receptor but were “kinder and gentler,” Dr. Lieberman noted. “They didn’t bind to [the receptor] with such affinity that it shut things down completely, so had fewer neurologic side effects.”

However, these agents had other adverse consequences, such as weight gain and other metabolic effects including hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia.

Many have poor functional status and quality of life despite lifelong treatment with current antipsychotic agents.

“The pharmaceutical industry, biotech industry, and academic psychiatric community have been desperately trying to find novel strategies for antipsychotic drug development and asking, ‘Is D2 the only holy grail or are there other ways of treating psychotic symptoms of schizophrenia?’ ” Dr. Lieberman said.

Enter KarXT – a novel combination of xanomeline with trospium.

An ‘ingenious’ combination

Xanomeline, an oral muscarinic cholinergic receptor agonist, does not have direct effects on the dopamine receptor. Evidence suggests the muscarinic cholinergic system is involved in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia.

However, there may be dose-dependent adverse events with the medication, such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, sweating, and hypersalivation from stimulation of peripheral muscarinic cholinergic receptors.

That’s where trospium chloride, an oral panmuscarinic receptor antagonist approved for treating overactive bladder, comes in. It does not reach detectable levels in the cerebrospinal fluid and should avoid adverse central nervous system effects.

Dr. Lieberman said the idea of the drug combination is “ingenious.”

The new phase 2, multisite study included adult patients with a validated diagnosis of schizophrenia who were hospitalized with an acute exacerbation of psychosis, and who were free of antipsychotic medication for at least 2 weeks.

Participants were required to have a baseline Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total score of 80 points or more.

In addition to seven positive symptom items, including delusions, hallucinations, and conceptual disorganization, the PANSS has seven negative symptom items. These include restricted emotional expression, paucity of speech, and diminished interest, social drive, and activity. Each item is scored from 1 to 7, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms.

Patients also had to have a score on the Clinical Global Impression–Severity (CGI-S) scale of 4 or higher. Scores on the CGI-S range from 1 to 7, with higher scores indicating greater severity of illness.

The modified intention-to-treat analysis included patients randomly assigned to receive oral xanomeline-trospium (n = 83) or placebo (n = 87).

The dosing schedule was flexible, starting with 50 mg of xanomeline and 20 mg of trospium twice daily. The schedule increased to a maximum of 125 mg of xanomeline and 30 mg of trospium twice daily, with the option of lowering the dose if there were unacceptable side effects.

Mean scores at baseline for the treatment and placebo groups were 97.7 versus 96.6 for the PANSS total score, 26.4 versus 26.3 for the positive subscore, 22.6 versus 22.8 for the negative subscore, and 5.0 versus 4.9 in the CGI-S scale.

‘Impressively robust’ effect size

The primary endpoint was change in the PANSS total score at 5 weeks. Results showed a change of –17.4 points in the treatment group and –5.9 points in the placebo group (least-squares mean difference, –11.6 points; 95% confidence interval, –16.1 to –7.1; P < .001).

The effect size, which was almost 0.8 (0.75), was “impressively robust,” said Dr. Lieberman, adding that a moderate effect size in this patient population might be in the order of 0.4 or 0.5.

“That gives hope that this drug may not just be as effective as other antipsychotics, albeit acting in a novel way and in a way that has a less of side effect burden, but that it may actually have some elements of superior efficacy,” he said.

There were significant benefits on some secondary outcomes, including change in the PANSS positive symptom subscore (–5.6 points in the treatment group vs. –2.4 points in the placebo group; least-squares mean difference, –3.2 points; 95% CI, –4.8 to –1.7; P < .001).

The active treatment also came out on top for CGI-S scores (P < .001), and PANSS negative symptom subscore (P < .001).

Because participants were hospitalized with an acute exacerbation of positive symptoms at time of study, it is difficult to determine “definitive efficacy” for negative symptoms, Dr. Lieberman noted. Negative symptoms may have improved simply because positive symptoms got better, he said.

Although the study included adults only, “there is nothing in the KarXT clinical profile that suggests it would be problematic for younger people,” Dr. Lieberman noted. This could include teenagers with first-episode psychosis.

Safety profile

Adverse events (AEs) were reported in 54% of the treatment group and 43% of the placebo group. AEs that were more common in the active treatment group included constipation (17% vs. 3%), nausea (17% vs. 4%), dry mouth (9% vs. 1%), dyspepsia (9% vs. 4%), and vomiting (9% vs. 4%). All AEs were rated as mild or moderate in severity and none resulted in discontinuation of treatment.

Rates of nausea, vomiting, and dry mouth were highest early in the trial and lower at the end, whereas constipation remained constant throughout the study.

Persistent constipation could affect the drug’s “utility” in elderly patients with cognitive issues but may be more of a “minor nuisance,” compared with other antipsychotics for those with schizophrenia, said Dr. Lieberman. He added that constipation might be mitigated with an over-the-counter treatment such as Metamucil. Importantly, there was no difference between groups in extrapyramidal symptoms.

In addition, participants receiving the active treatment did not have greater weight gain, which was about 3% versus 4% in the placebo group. The mean change in weight was 1.5 kg (3.3 lb) and 1.1 kg (2.4 lb), respectively.

Dr. Lieberman praised the manufacturer for undertaking the study.

“In an era when Big Pharma has retreated to a considerable degree from psychotropic drug development, it’s commendable that some companies have stayed the course and are succeeding in drug development,” he said.

Exciting mechanism

Commenting on the findings in an interview, Thomas Sedlak, MD, PhD, director of the Schizophrenia and Psychosis Consult Clinic and assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, called some aspects of the study “exciting.”

What’s especially important is that the novel agent “acts by a different mechanism than what we have been using for maybe 60 years,” said Dr. Sedlak, who was not involved with the research.

“There has been a lot of research in the last few decades into drugs that might act by alternate mechanisms of action, but nothing’s really gotten to market for schizophrenia,” he noted.

Another interesting aspect of the study is that it examined a combination drug that aims to maximize effects on the brain while minimizing periphery effects, Dr. Sedlak said.

In addition, he called the PANSS results “respectable.”

“It’s interesting that you get a big change in PANSS total score, but it’s not as big in the positive symptom score as you might have expected, and it’s not a huge drop in negative symptoms either,” said Dr. Sedlak.

It’s possible, he said, that the drug is targeting PANSS elements not captured in the main positive or negative symptom items; for example, anxiety, depression, guilt, attention, impulse control, disorientation, and judgment.

Dr. Sedlak noted that, while the new results are exciting, the enthusiasm may not be long-lasting. “When a new drug comes out, there’s often a lot of excitement about it, but once you start using it, expectations may deflate..

“More flexible ratios” of the two components of the drug might be useful to treat individual patients, he added.

In addition, using the components by themselves might be preferable for some clinicians. “I think a lot of physicians prefer using two separate drugs so they can alter the dose of each one independently and not be stuck with the ratio the manufacturer is providing,” Dr. Sedlak said.

However, he acknowledged that studying different choices of ratios would require much larger trials.

The study was supported by Karuna Therapeutics and the Wellcome Trust. Dr. Lieberman reported serving on an advisory board for Karuna Therapeutics and Intra-Cellular Therapies. Dr. Sedlak disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A novel therapy that combines a muscarinic receptor agonist with an anticholinergic agent is associated with a greater reduction in psychosis symptoms, compared with placebo, new research shows.

In a randomized, phase 2 trial composed of nearly 200 participants, xanomeline-trospium (KarXT) was generally well tolerated and had none of the common side effects linked to current antipsychotics, including weight gain and extrapyramidal symptoms such as dystonia, parkinsonism, and tardive dyskinesia.

“The results showing robust therapeutic efficacy of a non–dopamine targeting antipsychotic drug is an important milestone in the advance of the therapeutics of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders,” coinvestigator Jeffrey A. Lieberman, MD, professor and chairman in the department of psychiatry, Columbia University, New York, said in an interview.

If approved, the new agent will be a “landmark” drug, Dr. Lieberman added.

The study was published in the Feb. 25, 2021, issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.

Long journey

The journey to develop an effective schizophrenia drug that reduces psychosis symptoms without onerous side effects has been a long one full of excitement and disappointment.

First-generation antipsychotics, dating back to the 1950s, targeted the postsynaptic dopamine-2 (D2) receptor. At the time, it was a “breakthrough” similar in scope to insulin for diabetes or antibiotics for infections, said Dr. Lieberman.

That was followed by development of numerous “me too” drugs with the same mechanism of action. However, these drugs had significant side effects, especially neurologic adverse events such as parkinsonism.

In 1989, second-generation antipsychotics were introduced, beginning with clozapine. They still targeted the D2 receptor but were “kinder and gentler,” Dr. Lieberman noted. “They didn’t bind to [the receptor] with such affinity that it shut things down completely, so had fewer neurologic side effects.”

However, these agents had other adverse consequences, such as weight gain and other metabolic effects including hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia.

Many have poor functional status and quality of life despite lifelong treatment with current antipsychotic agents.

“The pharmaceutical industry, biotech industry, and academic psychiatric community have been desperately trying to find novel strategies for antipsychotic drug development and asking, ‘Is D2 the only holy grail or are there other ways of treating psychotic symptoms of schizophrenia?’ ” Dr. Lieberman said.

Enter KarXT – a novel combination of xanomeline with trospium.

An ‘ingenious’ combination

Xanomeline, an oral muscarinic cholinergic receptor agonist, does not have direct effects on the dopamine receptor. Evidence suggests the muscarinic cholinergic system is involved in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia.

However, there may be dose-dependent adverse events with the medication, such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, sweating, and hypersalivation from stimulation of peripheral muscarinic cholinergic receptors.

That’s where trospium chloride, an oral panmuscarinic receptor antagonist approved for treating overactive bladder, comes in. It does not reach detectable levels in the cerebrospinal fluid and should avoid adverse central nervous system effects.

Dr. Lieberman said the idea of the drug combination is “ingenious.”

The new phase 2, multisite study included adult patients with a validated diagnosis of schizophrenia who were hospitalized with an acute exacerbation of psychosis, and who were free of antipsychotic medication for at least 2 weeks.

Participants were required to have a baseline Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total score of 80 points or more.

In addition to seven positive symptom items, including delusions, hallucinations, and conceptual disorganization, the PANSS has seven negative symptom items. These include restricted emotional expression, paucity of speech, and diminished interest, social drive, and activity. Each item is scored from 1 to 7, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms.

Patients also had to have a score on the Clinical Global Impression–Severity (CGI-S) scale of 4 or higher. Scores on the CGI-S range from 1 to 7, with higher scores indicating greater severity of illness.

The modified intention-to-treat analysis included patients randomly assigned to receive oral xanomeline-trospium (n = 83) or placebo (n = 87).

The dosing schedule was flexible, starting with 50 mg of xanomeline and 20 mg of trospium twice daily. The schedule increased to a maximum of 125 mg of xanomeline and 30 mg of trospium twice daily, with the option of lowering the dose if there were unacceptable side effects.

Mean scores at baseline for the treatment and placebo groups were 97.7 versus 96.6 for the PANSS total score, 26.4 versus 26.3 for the positive subscore, 22.6 versus 22.8 for the negative subscore, and 5.0 versus 4.9 in the CGI-S scale.

‘Impressively robust’ effect size

The primary endpoint was change in the PANSS total score at 5 weeks. Results showed a change of –17.4 points in the treatment group and –5.9 points in the placebo group (least-squares mean difference, –11.6 points; 95% confidence interval, –16.1 to –7.1; P < .001).

The effect size, which was almost 0.8 (0.75), was “impressively robust,” said Dr. Lieberman, adding that a moderate effect size in this patient population might be in the order of 0.4 or 0.5.

“That gives hope that this drug may not just be as effective as other antipsychotics, albeit acting in a novel way and in a way that has a less of side effect burden, but that it may actually have some elements of superior efficacy,” he said.

There were significant benefits on some secondary outcomes, including change in the PANSS positive symptom subscore (–5.6 points in the treatment group vs. –2.4 points in the placebo group; least-squares mean difference, –3.2 points; 95% CI, –4.8 to –1.7; P < .001).

The active treatment also came out on top for CGI-S scores (P < .001), and PANSS negative symptom subscore (P < .001).

Because participants were hospitalized with an acute exacerbation of positive symptoms at time of study, it is difficult to determine “definitive efficacy” for negative symptoms, Dr. Lieberman noted. Negative symptoms may have improved simply because positive symptoms got better, he said.

Although the study included adults only, “there is nothing in the KarXT clinical profile that suggests it would be problematic for younger people,” Dr. Lieberman noted. This could include teenagers with first-episode psychosis.

Safety profile

Adverse events (AEs) were reported in 54% of the treatment group and 43% of the placebo group. AEs that were more common in the active treatment group included constipation (17% vs. 3%), nausea (17% vs. 4%), dry mouth (9% vs. 1%), dyspepsia (9% vs. 4%), and vomiting (9% vs. 4%). All AEs were rated as mild or moderate in severity and none resulted in discontinuation of treatment.

Rates of nausea, vomiting, and dry mouth were highest early in the trial and lower at the end, whereas constipation remained constant throughout the study.

Persistent constipation could affect the drug’s “utility” in elderly patients with cognitive issues but may be more of a “minor nuisance,” compared with other antipsychotics for those with schizophrenia, said Dr. Lieberman. He added that constipation might be mitigated with an over-the-counter treatment such as Metamucil. Importantly, there was no difference between groups in extrapyramidal symptoms.

In addition, participants receiving the active treatment did not have greater weight gain, which was about 3% versus 4% in the placebo group. The mean change in weight was 1.5 kg (3.3 lb) and 1.1 kg (2.4 lb), respectively.

Dr. Lieberman praised the manufacturer for undertaking the study.

“In an era when Big Pharma has retreated to a considerable degree from psychotropic drug development, it’s commendable that some companies have stayed the course and are succeeding in drug development,” he said.

Exciting mechanism

Commenting on the findings in an interview, Thomas Sedlak, MD, PhD, director of the Schizophrenia and Psychosis Consult Clinic and assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, called some aspects of the study “exciting.”

What’s especially important is that the novel agent “acts by a different mechanism than what we have been using for maybe 60 years,” said Dr. Sedlak, who was not involved with the research.

“There has been a lot of research in the last few decades into drugs that might act by alternate mechanisms of action, but nothing’s really gotten to market for schizophrenia,” he noted.

Another interesting aspect of the study is that it examined a combination drug that aims to maximize effects on the brain while minimizing periphery effects, Dr. Sedlak said.

In addition, he called the PANSS results “respectable.”

“It’s interesting that you get a big change in PANSS total score, but it’s not as big in the positive symptom score as you might have expected, and it’s not a huge drop in negative symptoms either,” said Dr. Sedlak.

It’s possible, he said, that the drug is targeting PANSS elements not captured in the main positive or negative symptom items; for example, anxiety, depression, guilt, attention, impulse control, disorientation, and judgment.

Dr. Sedlak noted that, while the new results are exciting, the enthusiasm may not be long-lasting. “When a new drug comes out, there’s often a lot of excitement about it, but once you start using it, expectations may deflate..

“More flexible ratios” of the two components of the drug might be useful to treat individual patients, he added.

In addition, using the components by themselves might be preferable for some clinicians. “I think a lot of physicians prefer using two separate drugs so they can alter the dose of each one independently and not be stuck with the ratio the manufacturer is providing,” Dr. Sedlak said.

However, he acknowledged that studying different choices of ratios would require much larger trials.

The study was supported by Karuna Therapeutics and the Wellcome Trust. Dr. Lieberman reported serving on an advisory board for Karuna Therapeutics and Intra-Cellular Therapies. Dr. Sedlak disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A novel therapy that combines a muscarinic receptor agonist with an anticholinergic agent is associated with a greater reduction in psychosis symptoms, compared with placebo, new research shows.

In a randomized, phase 2 trial composed of nearly 200 participants, xanomeline-trospium (KarXT) was generally well tolerated and had none of the common side effects linked to current antipsychotics, including weight gain and extrapyramidal symptoms such as dystonia, parkinsonism, and tardive dyskinesia.

“The results showing robust therapeutic efficacy of a non–dopamine targeting antipsychotic drug is an important milestone in the advance of the therapeutics of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders,” coinvestigator Jeffrey A. Lieberman, MD, professor and chairman in the department of psychiatry, Columbia University, New York, said in an interview.

If approved, the new agent will be a “landmark” drug, Dr. Lieberman added.

The study was published in the Feb. 25, 2021, issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.

Long journey

The journey to develop an effective schizophrenia drug that reduces psychosis symptoms without onerous side effects has been a long one full of excitement and disappointment.