User login

What is the diagnosis?

Syphilis

Although extremely rare, we checked a Venereal Disease Research Laboratory PCR, the results of which came back positive. A Treponema pallidum hemagglutination assay also returned positive with titers 1:5120 (ULN, < 1:80), confirming the diagnosis of syphilis. During his hospitalization, the patient developed a syphilitic skin rash on his back, chest, palms, feet, and soles (Figure C). The patient was started on penicillin G, 4 million units intravenously every 4 hours. The fever broke 36 hours after antibiotic initiation and 48 hours later, his bilirubin started to downtrend, followed by the alkaline phosphatase and GGT 3 days later. His rash completely disappeared 5 days after antibiotic initiation. He received a total of 2 weeks of penicillin G intravenously at 24 million units a day and his liver enzymes normalized 7 weeks later.

Syphilitic hepatitis is extremely rare and occurs in 0.2% of patients with secondary syphilis.1 There are few cases of syphilitic hepatitis in HIV carriers reported in the literature. Of the described cases, only two patients had an undetectable viral load.2,3 The clinical presentation of syphilitic hepatitis includes jaundice, pruritus, nausea, and vomiting, in addition to generalized symptoms of fatigue, malaise, and weight loss. Biochemically, alkaline phosphatase and GGT are predominantly elevated with mild elevation in the transaminases. Few cases describe an elevation in the bilirubin. Diagnosis is made based on treponemal testing and/or evaluation of tissue for spirochetes on liver biopsy. The majority of cases used penicillin G with excellent response. Doxycycline was also used in one case and ceftriaxone was used in another.

In our case, the patient had several other possible reasons for his liver enzyme elevation, including drug-induced liver injury, cocaine, and alcohol use, which could have contributed to his disturbed liver enzymes. The steady improvement in his cholestatic liver enzymes, fever, and rash, shortly after the initiation of penicillin G indicates that syphilis was the cause of his hepatitis. Given the improvement in his symptoms and biochemical markers, we refrained from obtaining a liver biopsy.

References

1. Lee M., Wang C., Dorer R. et al. A great masquerader: Acute syphilitic hepatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:923-5.

2. Mullick CJ. Liappis A.P. Benator D.A. et al. Syphilitic hepatitis in HIV-infected patients: A report of 7 cases and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:e100-e105.

3. German MN. Matkowskyj K.A. Hoffman R.J. et al. A case of syphilitic hepatitis in an HIV-infected patient. Hum Pathol. 2018;79:184-7.

Syphilis

Although extremely rare, we checked a Venereal Disease Research Laboratory PCR, the results of which came back positive. A Treponema pallidum hemagglutination assay also returned positive with titers 1:5120 (ULN, < 1:80), confirming the diagnosis of syphilis. During his hospitalization, the patient developed a syphilitic skin rash on his back, chest, palms, feet, and soles (Figure C). The patient was started on penicillin G, 4 million units intravenously every 4 hours. The fever broke 36 hours after antibiotic initiation and 48 hours later, his bilirubin started to downtrend, followed by the alkaline phosphatase and GGT 3 days later. His rash completely disappeared 5 days after antibiotic initiation. He received a total of 2 weeks of penicillin G intravenously at 24 million units a day and his liver enzymes normalized 7 weeks later.

Syphilitic hepatitis is extremely rare and occurs in 0.2% of patients with secondary syphilis.1 There are few cases of syphilitic hepatitis in HIV carriers reported in the literature. Of the described cases, only two patients had an undetectable viral load.2,3 The clinical presentation of syphilitic hepatitis includes jaundice, pruritus, nausea, and vomiting, in addition to generalized symptoms of fatigue, malaise, and weight loss. Biochemically, alkaline phosphatase and GGT are predominantly elevated with mild elevation in the transaminases. Few cases describe an elevation in the bilirubin. Diagnosis is made based on treponemal testing and/or evaluation of tissue for spirochetes on liver biopsy. The majority of cases used penicillin G with excellent response. Doxycycline was also used in one case and ceftriaxone was used in another.

In our case, the patient had several other possible reasons for his liver enzyme elevation, including drug-induced liver injury, cocaine, and alcohol use, which could have contributed to his disturbed liver enzymes. The steady improvement in his cholestatic liver enzymes, fever, and rash, shortly after the initiation of penicillin G indicates that syphilis was the cause of his hepatitis. Given the improvement in his symptoms and biochemical markers, we refrained from obtaining a liver biopsy.

References

1. Lee M., Wang C., Dorer R. et al. A great masquerader: Acute syphilitic hepatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:923-5.

2. Mullick CJ. Liappis A.P. Benator D.A. et al. Syphilitic hepatitis in HIV-infected patients: A report of 7 cases and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:e100-e105.

3. German MN. Matkowskyj K.A. Hoffman R.J. et al. A case of syphilitic hepatitis in an HIV-infected patient. Hum Pathol. 2018;79:184-7.

Syphilis

Although extremely rare, we checked a Venereal Disease Research Laboratory PCR, the results of which came back positive. A Treponema pallidum hemagglutination assay also returned positive with titers 1:5120 (ULN, < 1:80), confirming the diagnosis of syphilis. During his hospitalization, the patient developed a syphilitic skin rash on his back, chest, palms, feet, and soles (Figure C). The patient was started on penicillin G, 4 million units intravenously every 4 hours. The fever broke 36 hours after antibiotic initiation and 48 hours later, his bilirubin started to downtrend, followed by the alkaline phosphatase and GGT 3 days later. His rash completely disappeared 5 days after antibiotic initiation. He received a total of 2 weeks of penicillin G intravenously at 24 million units a day and his liver enzymes normalized 7 weeks later.

Syphilitic hepatitis is extremely rare and occurs in 0.2% of patients with secondary syphilis.1 There are few cases of syphilitic hepatitis in HIV carriers reported in the literature. Of the described cases, only two patients had an undetectable viral load.2,3 The clinical presentation of syphilitic hepatitis includes jaundice, pruritus, nausea, and vomiting, in addition to generalized symptoms of fatigue, malaise, and weight loss. Biochemically, alkaline phosphatase and GGT are predominantly elevated with mild elevation in the transaminases. Few cases describe an elevation in the bilirubin. Diagnosis is made based on treponemal testing and/or evaluation of tissue for spirochetes on liver biopsy. The majority of cases used penicillin G with excellent response. Doxycycline was also used in one case and ceftriaxone was used in another.

In our case, the patient had several other possible reasons for his liver enzyme elevation, including drug-induced liver injury, cocaine, and alcohol use, which could have contributed to his disturbed liver enzymes. The steady improvement in his cholestatic liver enzymes, fever, and rash, shortly after the initiation of penicillin G indicates that syphilis was the cause of his hepatitis. Given the improvement in his symptoms and biochemical markers, we refrained from obtaining a liver biopsy.

References

1. Lee M., Wang C., Dorer R. et al. A great masquerader: Acute syphilitic hepatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:923-5.

2. Mullick CJ. Liappis A.P. Benator D.A. et al. Syphilitic hepatitis in HIV-infected patients: A report of 7 cases and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:e100-e105.

3. German MN. Matkowskyj K.A. Hoffman R.J. et al. A case of syphilitic hepatitis in an HIV-infected patient. Hum Pathol. 2018;79:184-7.

A 48-year-old man with HIV infection (PCR undetectable CD4 483) who used cocaine and was a heavy user of alcohol presented with jaundice, fever, and acute-onset left-upper quadrant abdominal pain. The pain was exacerbated by breathing. He had associated intermittent fevers and weight loss starting 3 weeks before presentation. He denied chest pain, nausea, vomiting, or a change in bowel habits. Home medications included dolutegravir, emtricitabine, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, and recent intake of tamoxifen, clomiphene, and chorionic gonadotropin to counteract the effects of anabolic steroids that were used 4 months before presentation.

On examination, his temperature was 39°C, he was jaundiced, and he had icteric sclera. The abdomen was soft and nondistended with minimal left-upper quadrant tenderness. Blood work showed a white blood cell count of 7,800/mcL, hemoglobin of 12.2 g/dL, platelets of 378,000/mcL, alanine aminotransferase 236 IU/L (upper limit of normal [ULN], 65 IU/L), aspartate aminotransferase 166 IU/L (ULN, 50 IU/L), total bilirubin 3.4 mg/dL (ULN, 1.2 mg/dL), direct bilirubin 2.6 mg/dL (ULN, 0.3 mg/dL), alkaline phosphatase 1,064 IU/L (ULN, 120 IU/L), gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) of 655 (ULN, 50 IU/L), protein of 73 g/L, and albumin of 34 g/L. Lipase, lactate dehydrogenase, and international normalized ratio were normal. Blood smear was unrevealing. A contrasted computed tomography scan showed multiple subcentimetric mesenteric and multiple retroperitoneal lymph nodes, the largest of which was 1.3 cm in the aortocaval area. All medications were discontinued. Hepatitis A, B, and C serologies were negative, including hepatitis B and C PCR. Epstein-Barr virus IgM was negative and cytomegalovirus IgM was equivocal.

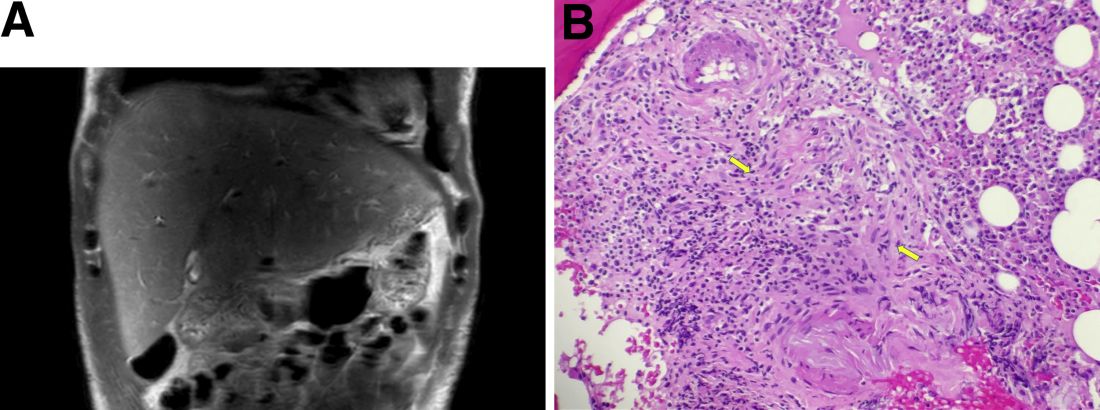

During this hospitalization, his cholestatic liver enzymes continued to rise, reaching a maximum value of total bilirubin of 7.8 mg/dL, direct bilirubin of 6.5 mg/dL, and 3 days later, alkaline phosphatase of 1,637 IU/L and GGT of 1,171 IU/L. Alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase slowly downtrended during the hospitalization. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography showed an edematous enlarged liver with minimal peripheral intrahepatic dilatation without an obstructing mass or extrahepatic biliary ductal dilatation (Figure A). Comprehensive autoimmune hepatic serology, iron studies, ceruloplasmin, and alpha-1 antitrypsin labs were negative. The patient remained febrile, so a positron emission tomography computed tomography scan was done and it showed active and enlarged (2.8-cm) portocaval and porta hepatis lymph nodes. Bone marrow biopsy showed no lymphoproliferative disorder, but there was a small poorly formed granuloma (Figure B, between the arrows).

What other testing would you obtain to evaluate this patient's fever and abnormal liver enzymes?

Previously published in Gastroenterology