User login

Scholarly Productivity and Rank in Academic Hospital Medicine

Hospital medicine has grown rapidly, with more than 50,000 hospitalists practicing nationally in 2016.1 Despite the remarkable increase in academic hospital medicine faculty (AHMF), scholarly productivity remains underdeveloped. Prior evidence suggests peer-reviewed publications remain an important aspect of promotion in academic hospital medicine.2 However, there are multiple barriers to robust scholarly productivity among AHMF, including inadequate mentorship,3 lack of protected scholarship time,4 and greater participation in nonclinical activities outside of peer-reviewed clinical research.5 Though research barriers have been described previously, the current state of scholarly productivity among AHMF has not been characterized. In this cross-sectional study, we describe the distribution of academic rank and scholarly output of a national sample of AHMF.

METHODS

Study Design and Data Source

We performed a cross-sectional study of AHMF at the top 25 internal medicine residency programs as determined by Doximity.com as of February 1, 2020 (Appendix Table 1). Between March and August 2020, two authors (NS, MT) visited each residency program’s website, identified all faculty listed as members of the hospital medicine program, and extracted demographic data, including degrees, sex, residency, medical school, year of residency graduation, completion of chief residency, completion of fellowship, and rank. We categorized all academic titles into full professor, associate professor, assistant professor, and instructor/lecturer. Missing information was supplemented by searching state licensing websites and Doximity.com. Sex was validated using Genderize.io. We queried the Scopus database for each AHMF’s name and affiliated institution to extract publications, citations, and H-index (metric of productivity and impact, derived from the number of publications and their associated citations).6 We categorized medical schools by rank (top 25, top 50, or unranked), as defined by the 2020 US News Best Medical Schools, sorted by research7 and by location (United States, international Caribbean, and international non-Caribbean). We excluded programs without hospital medicine section/division webpages and AHMF with nonpromotion titles such as “adjunct professor” or “acting professor” or those with missing data that could not be identified using these methods.

Analysis

Summary statistics were generated using means with standard deviations and medians with interquartile ranges. We evaluated postresidency years 6 to 10 and 14 to 18 as conservative time frames for promotion to associate and full professor, respectively. These windows account for time spent for additional degrees, instructor years, and alternative career pathways. Demographic differences between academic ranks were determined using chi-square and Kruskal-Wallis analyses.

Because promotion occurs sequentially, a proportional odds logistic regression model was used to evaluate the association of academic rank and H-index, number of years post residency, completion of chief residency, graduation from a top 25 medical school, and sex. Since not all programs have the instructor/lecturer rank, only assistant, associate, and full professors were included in this model. Significance was assessed with the likelihood ratio test. The proportional odds assumption was assessed using the score test. All adjusted odds ratios and their associated 95% confidence intervals were recorded. A two-tailed P value < .05 was considered significant for this study, and SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc) was used to conduct all analyses. This study was approved by the UT Southwestern Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Cohort Demographics

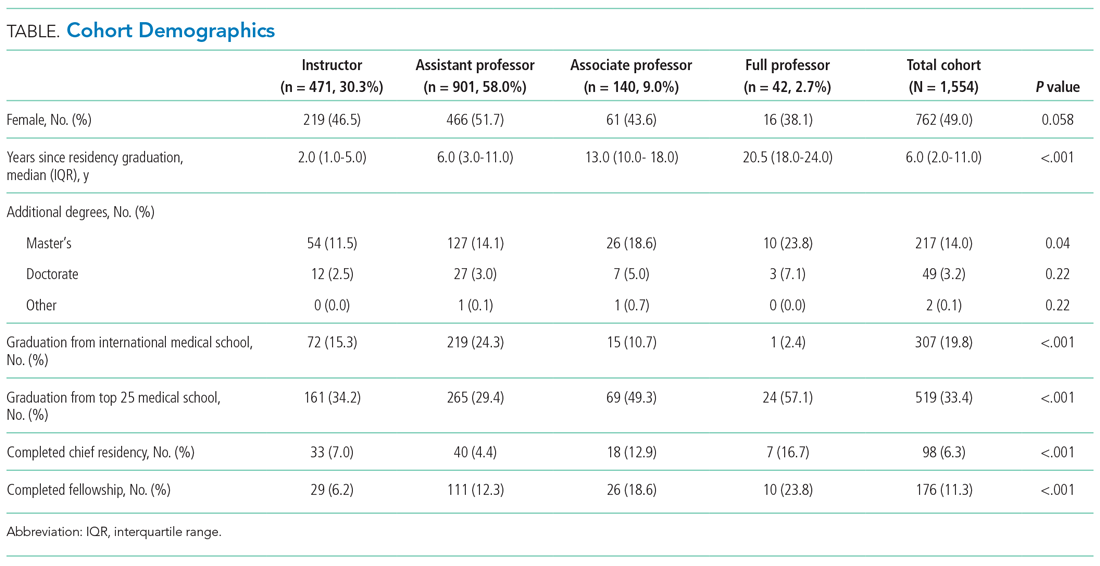

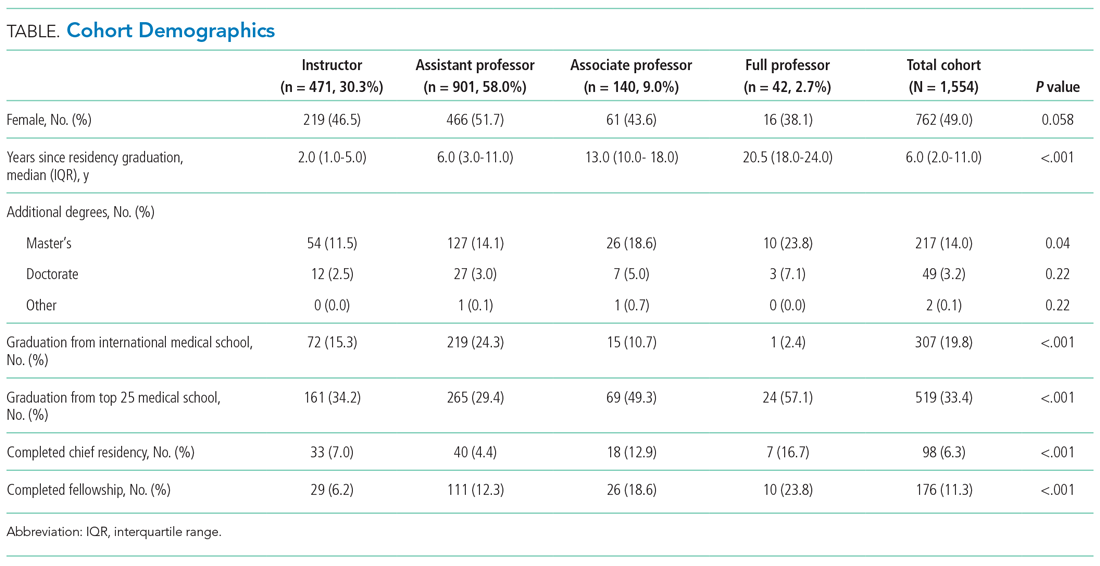

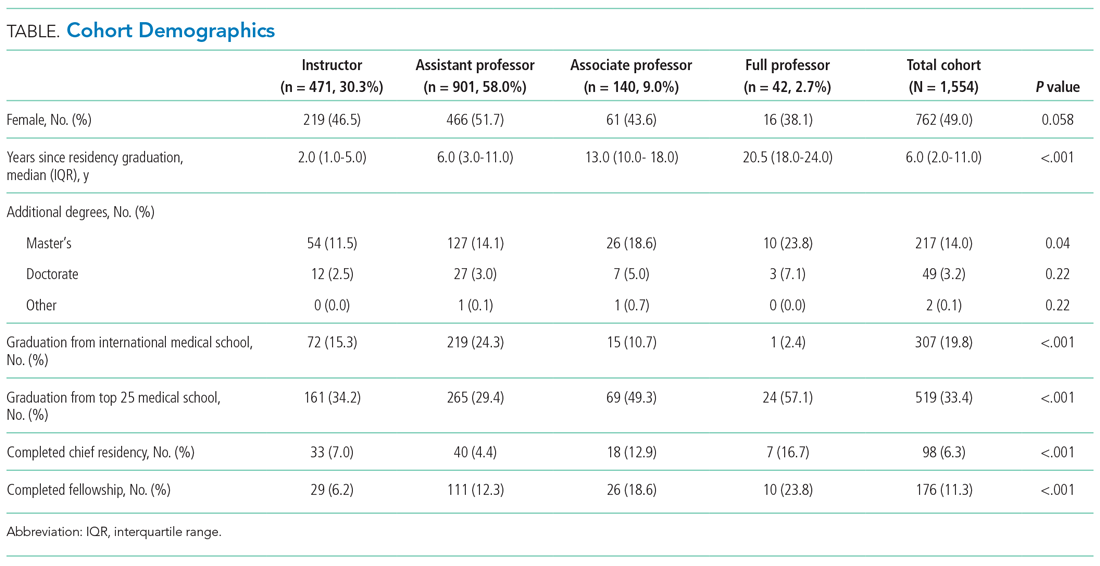

Of the top 25 internal medicine programs, 3 were excluded because they did not have websites that listed AHMF. Of the remaining 22 programs, we identified 1,829 AHMF. We excluded 166 AHMF because we could not identify title or year of residency graduation and 109 for having nonpromotion titles, leaving 1,554 AHMF (Appendix Figure). The cohort characteristics are described in Table 1.

Research Productivity

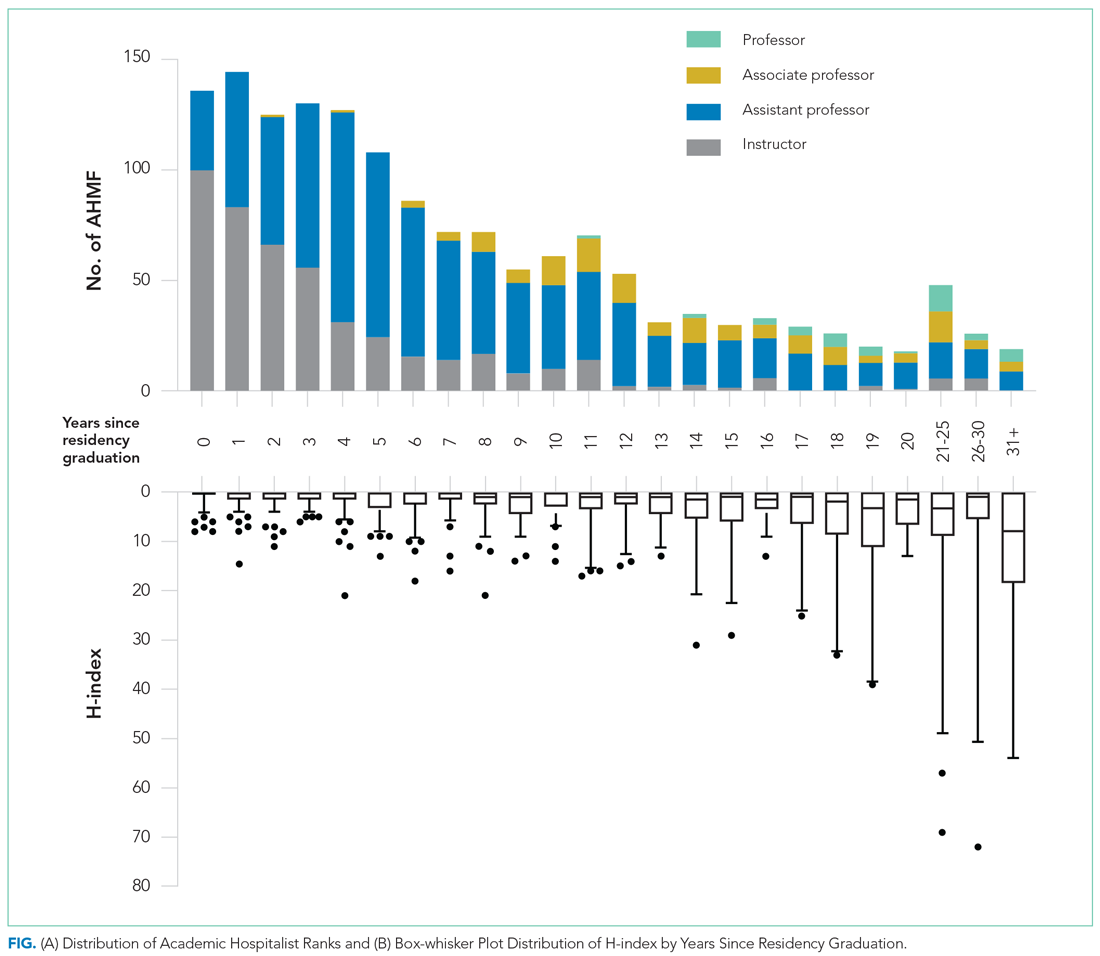

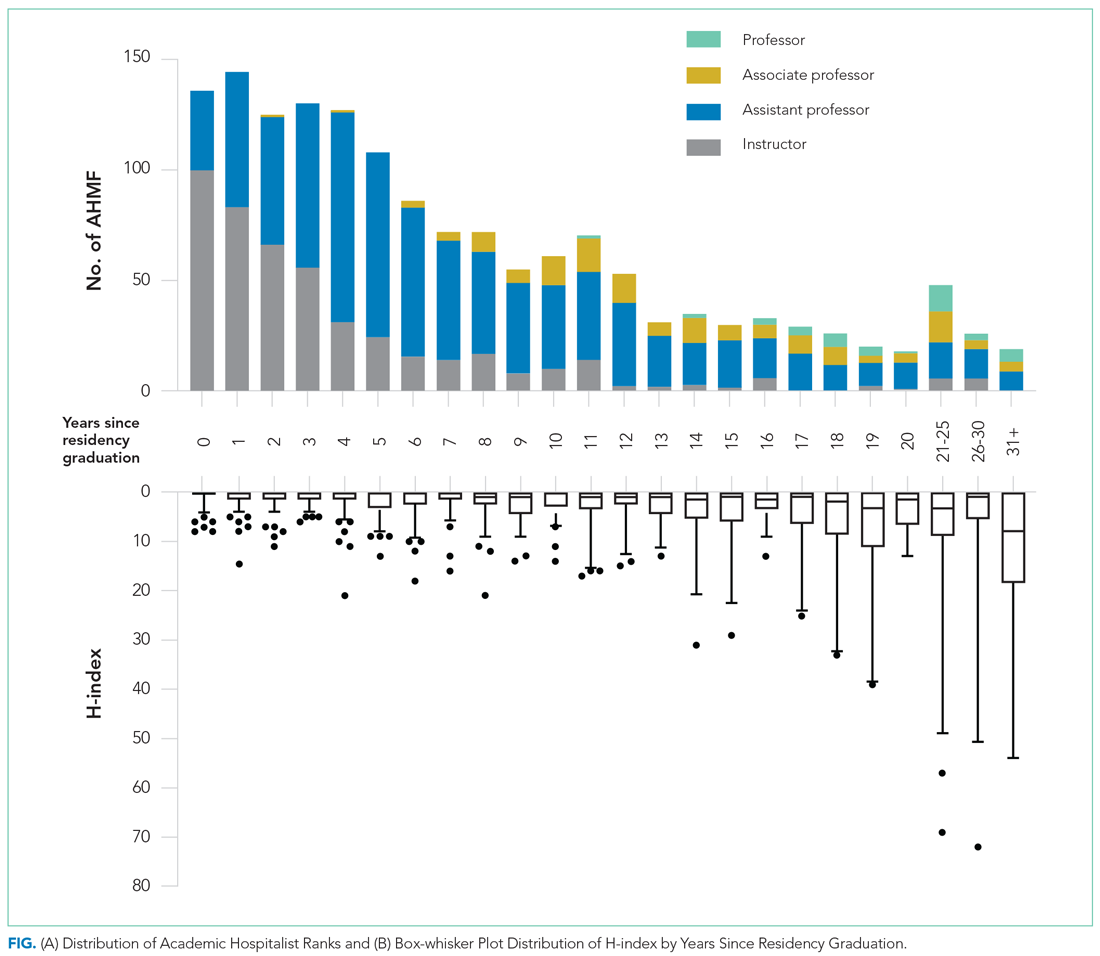

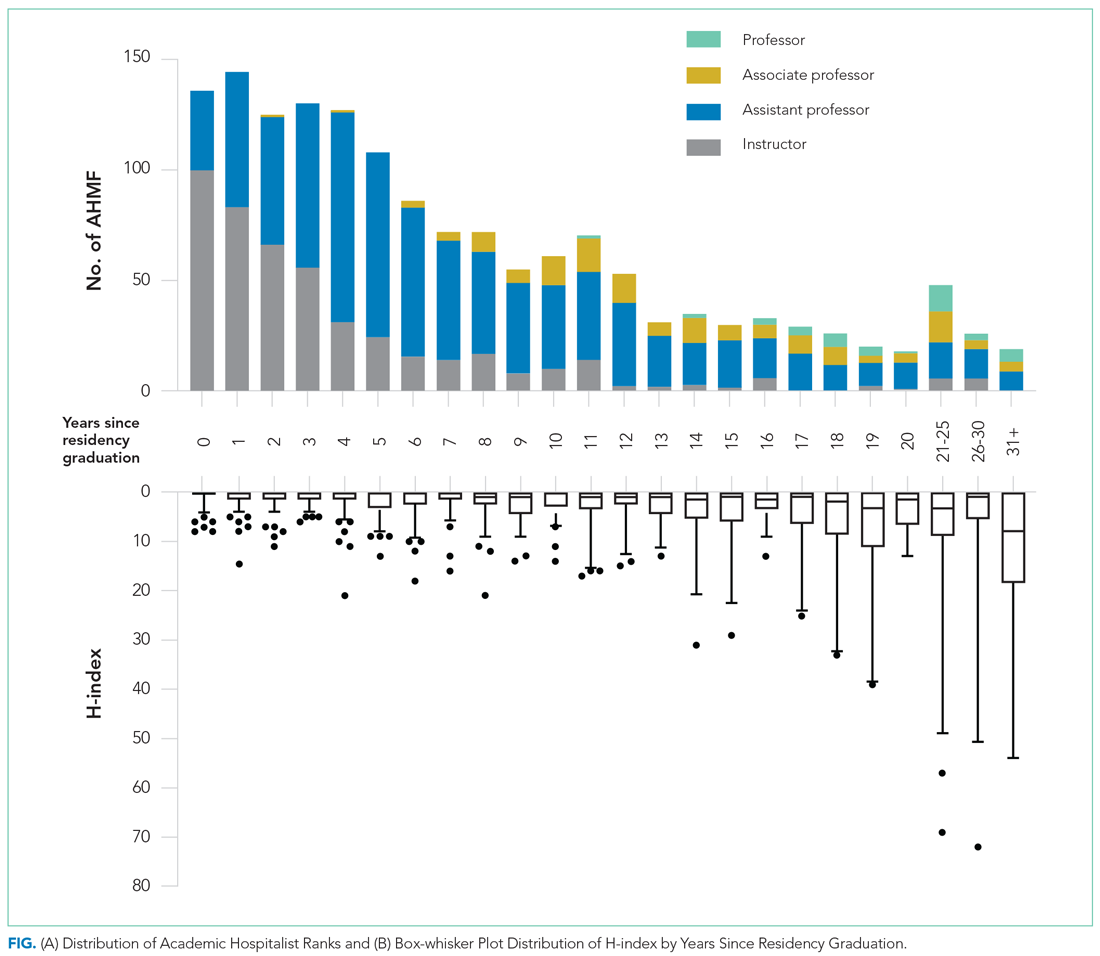

A total of 9,809 documents had been published by this cohort of academic hospitalists (Appendix Table 2). Overall mean (SD) and median (IQR) publications were 6.3 (24.3) and 0.0 (0.0-4.0), respectively. A total of 799 (51.4%) AHMF had no publications, 347 (22.3%) had one to three publications, 209 (13.4%) had 10 or more, and 39 (2.5%) had 50 or more. The median number of publications stratified by academic rank were 0.0 (IQR, 0.0-1.0) for instructors, 0.0 (IQR, 0.0-3.0) for assistant professors, 8.0 (IQR, 2.0-23.0) for associate professors, and 38.0 (IQR, 6.0-99.0) for full professors. Among men, 54.3% had published at least one manuscript, compared to 42.7% of women (P < .0001). The distribution of H-indices by years since residency graduation is shown in the Figure. The median number of documents published by faculty 6 to 10 years post residency was 1.0 (IQR, 0.0-4.0), with 46.8% of these faculty without a publication. For faculty 14 to 18 years post residency, the median number of documents was 3.0 (IQR, 0.0-11.0), with 30.1% of these faculty without a publication. Years post residency and academic rank were correlated with higher H-indices as well as more publications and citations (P < .0001).

Factors Associated With Academic Rank

Factors associated with rank are described in Appendix Table 3. In our multivariable ordinal regression model, H-index (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.16 per single H-index point; 95% CI, 1.12-1.20), years post residency graduation (aOR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.11-1.17), completion of chief residency (aOR, 2.46; 95% CI, 1.34-4.51), and graduation from a top 25 medical school (aOR, 2.10; 95% CI, 1.44-3.06) were associated with promotion.

DISCUSSION

In this cross-sectional analysis of more than 1,500 AHMF at the top 25 internal medicine residencies in the United States, 88.3% were instructors or assistant professors, while only 11.7% were associate or full professors. Furthermore, 51.4% were without a publication, and only 26.3% had published more than three manuscripts. Last, H-index, completion of a chief residency, years post residency, and graduation from a top 25 medical school were associated with higher academic rank.

Only 2.7% of the cohort were full professors, and 9.0% were associate professors. In comparison, academic cardiology faculty are 28.2% full professors and 22.9% associate professors.8 While the field of hospital medicine is relatively new, many faculty members had practiced for the expected duration of time for promotion consideration, with assistant professors or instructors constituting 89.9% of faculty at 6 to 10 years and 63.6% of faculty at 14 to 18 years post residency. We additionally observed a gender gap in publication history in hospital medicine, consistent with prior studies in hospital medicine that suggested gender disparities in scholarship.9,10 Increased focus will be needed in the future to ensure opportunities for scholarship are equitable for all faculty in hospital medicine.

Our findings suggest that scholarly productivity in academic hospital medicine remains a challenge. Prior studies have reported that less than half of academic hospitalists have ever published, and fewer than one in eight have received research funding.11,12 It is encouraging, however, that publications increase with time after residency. These data are consistent with the literature demonstrating a modest increase in hospitalists who had ever published, increasing from 43.0% in 2012 to 48.6% in 2020.12 Despite these trends, however, some early-career academic hospitalists report ambivalence toward academic productivity and promotion.13 Whether this ambivalence is the source of low scholarship output or the outcome of insufficient mentorship and limited research success is uncertain. But these factors, combined with the pressures of clinical productivity, the existing lack of mentorship, and inadequate protected research time represent barriers to successful scholarship in academic hospital medicine.3,14

Our study has several limitations. First, our inclusion criteria for the top 25 internal medicine residencies may have excluded hospital medicine divisions with substantial scholarly productivity. However, with 21 of the 25 programs listed on Doximity.com in the top 25 for internal medicine research funding, it is likely that our results overestimate scholarly productivity if compared to a complete, national cohort of AHMF.15 Second, our findings may not be generalizable to hospitalists who practice in nonacademic settings. Third, we were unable to account for differences in promotion criteria/tracks or scholarly output expectations between institutions. This limitation has been seen similarly in prior studies linking promotion and H-index.2 Furthermore, our study does not capture promotion via other pathways that may not depend on scholarly output, such as hospital leadership roles. Last, as data were abstracted from academic center websites, it is possible that not all information was accurate or updated. However, we randomly reevaluated 25% of hospital division webpages 6 months after our initial data collection and noted that all had been updated with new faculty and academic ranks, suggesting our data were accurate.

These data highlight that research productivity and academic promotion remain challenges in academic hospital medicine. Future studies may examine topics that include understanding pathways and milestones to promotion, reducing disparities in scholarship, and improving mentorship, protected time, and research funding in academic hospital medicine.

1. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000—the 20th anniversary of the hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1009-1011. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1607958

2. Leykum LK, Parekh VI, Sharpe B, Boonyasai RT, Centor RM. Tried and true: a survey of successfully promoted academic hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(7):411-415. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.894

3. Harrison R, Hunter AJ, Sharpe B, Auerbach AD. Survey of US academic hospitalist leaders about mentorship and academic activities in hospitalist groups. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(1):5-9. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.836

4. Cumbler E, Rendón P, Yirdaw E, et al. Keys to career success: resources and barriers identified by early career academic hospitalists. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(5):588-589. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4336-7

5. Flanders SA, Centor B, Weber V, McGinn T, DeSalvo K, Auerbach A. Challenges and opportunities in academic hospital medicine: report from the Academic Hospital Medicine Summit. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(4):240-246. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.497

6. Hirsch JE. An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(46):16569-16572. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0507655102

7. 2021 Best Medical Schools: Research. U.S. News & World Report. Accessed April 23, 2021. https://www.usnews.com/best-graduate-schools/top-medical-schools/research-rankings

8. Blumenthal DM, Olenski AR, Yeh RW, et al. Sex differences in faculty rank among academic cardiologists in the United States. Circulation. 2017;135(6):506-517. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.023520

9. Burden M, Frank MG, Keniston A, et al. Gender disparities in leadership and scholarly productivity of academic hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(8):481-485. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2340

10. Adler E, Hobbs A, Dhaliwal G, Babik JM. Gender differences in authorship of clinical problem-solving articles. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(8):475-478. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3465

11. Chopra V, Burden M, Jones CD, et al. State of research in adult hospital medicine: results of a national survey. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(4):207-211. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3136

12. Dang Do AN, Munchhof AM, Terry C, Emmett T, Kara A. Research and publication trends in hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):148-154. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2148

13. Cumbler E, Yirdaw E, Kneeland P, et al. What is career success for academic hospitalists? A qualitative analysis of early-career faculty perspectives. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(6):372-377. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2924

14. Reid MB, Misky GJ, Harrison RA, Sharpe B, Auerbach A, Glasheen JJ. Mentorship, productivity, and promotion among academic hospitalists. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):23-27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1892-5

15. Roskoski R Jr, Parslow TG. Ranking tables of NIH funding to US medical schools in 2019. Accessed April 23, 2021. http://www.brimr.org/NIH_Awards/2019/NIH_Awards_2019.htm

Hospital medicine has grown rapidly, with more than 50,000 hospitalists practicing nationally in 2016.1 Despite the remarkable increase in academic hospital medicine faculty (AHMF), scholarly productivity remains underdeveloped. Prior evidence suggests peer-reviewed publications remain an important aspect of promotion in academic hospital medicine.2 However, there are multiple barriers to robust scholarly productivity among AHMF, including inadequate mentorship,3 lack of protected scholarship time,4 and greater participation in nonclinical activities outside of peer-reviewed clinical research.5 Though research barriers have been described previously, the current state of scholarly productivity among AHMF has not been characterized. In this cross-sectional study, we describe the distribution of academic rank and scholarly output of a national sample of AHMF.

METHODS

Study Design and Data Source

We performed a cross-sectional study of AHMF at the top 25 internal medicine residency programs as determined by Doximity.com as of February 1, 2020 (Appendix Table 1). Between March and August 2020, two authors (NS, MT) visited each residency program’s website, identified all faculty listed as members of the hospital medicine program, and extracted demographic data, including degrees, sex, residency, medical school, year of residency graduation, completion of chief residency, completion of fellowship, and rank. We categorized all academic titles into full professor, associate professor, assistant professor, and instructor/lecturer. Missing information was supplemented by searching state licensing websites and Doximity.com. Sex was validated using Genderize.io. We queried the Scopus database for each AHMF’s name and affiliated institution to extract publications, citations, and H-index (metric of productivity and impact, derived from the number of publications and their associated citations).6 We categorized medical schools by rank (top 25, top 50, or unranked), as defined by the 2020 US News Best Medical Schools, sorted by research7 and by location (United States, international Caribbean, and international non-Caribbean). We excluded programs without hospital medicine section/division webpages and AHMF with nonpromotion titles such as “adjunct professor” or “acting professor” or those with missing data that could not be identified using these methods.

Analysis

Summary statistics were generated using means with standard deviations and medians with interquartile ranges. We evaluated postresidency years 6 to 10 and 14 to 18 as conservative time frames for promotion to associate and full professor, respectively. These windows account for time spent for additional degrees, instructor years, and alternative career pathways. Demographic differences between academic ranks were determined using chi-square and Kruskal-Wallis analyses.

Because promotion occurs sequentially, a proportional odds logistic regression model was used to evaluate the association of academic rank and H-index, number of years post residency, completion of chief residency, graduation from a top 25 medical school, and sex. Since not all programs have the instructor/lecturer rank, only assistant, associate, and full professors were included in this model. Significance was assessed with the likelihood ratio test. The proportional odds assumption was assessed using the score test. All adjusted odds ratios and their associated 95% confidence intervals were recorded. A two-tailed P value < .05 was considered significant for this study, and SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc) was used to conduct all analyses. This study was approved by the UT Southwestern Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Cohort Demographics

Of the top 25 internal medicine programs, 3 were excluded because they did not have websites that listed AHMF. Of the remaining 22 programs, we identified 1,829 AHMF. We excluded 166 AHMF because we could not identify title or year of residency graduation and 109 for having nonpromotion titles, leaving 1,554 AHMF (Appendix Figure). The cohort characteristics are described in Table 1.

Research Productivity

A total of 9,809 documents had been published by this cohort of academic hospitalists (Appendix Table 2). Overall mean (SD) and median (IQR) publications were 6.3 (24.3) and 0.0 (0.0-4.0), respectively. A total of 799 (51.4%) AHMF had no publications, 347 (22.3%) had one to three publications, 209 (13.4%) had 10 or more, and 39 (2.5%) had 50 or more. The median number of publications stratified by academic rank were 0.0 (IQR, 0.0-1.0) for instructors, 0.0 (IQR, 0.0-3.0) for assistant professors, 8.0 (IQR, 2.0-23.0) for associate professors, and 38.0 (IQR, 6.0-99.0) for full professors. Among men, 54.3% had published at least one manuscript, compared to 42.7% of women (P < .0001). The distribution of H-indices by years since residency graduation is shown in the Figure. The median number of documents published by faculty 6 to 10 years post residency was 1.0 (IQR, 0.0-4.0), with 46.8% of these faculty without a publication. For faculty 14 to 18 years post residency, the median number of documents was 3.0 (IQR, 0.0-11.0), with 30.1% of these faculty without a publication. Years post residency and academic rank were correlated with higher H-indices as well as more publications and citations (P < .0001).

Factors Associated With Academic Rank

Factors associated with rank are described in Appendix Table 3. In our multivariable ordinal regression model, H-index (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.16 per single H-index point; 95% CI, 1.12-1.20), years post residency graduation (aOR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.11-1.17), completion of chief residency (aOR, 2.46; 95% CI, 1.34-4.51), and graduation from a top 25 medical school (aOR, 2.10; 95% CI, 1.44-3.06) were associated with promotion.

DISCUSSION

In this cross-sectional analysis of more than 1,500 AHMF at the top 25 internal medicine residencies in the United States, 88.3% were instructors or assistant professors, while only 11.7% were associate or full professors. Furthermore, 51.4% were without a publication, and only 26.3% had published more than three manuscripts. Last, H-index, completion of a chief residency, years post residency, and graduation from a top 25 medical school were associated with higher academic rank.

Only 2.7% of the cohort were full professors, and 9.0% were associate professors. In comparison, academic cardiology faculty are 28.2% full professors and 22.9% associate professors.8 While the field of hospital medicine is relatively new, many faculty members had practiced for the expected duration of time for promotion consideration, with assistant professors or instructors constituting 89.9% of faculty at 6 to 10 years and 63.6% of faculty at 14 to 18 years post residency. We additionally observed a gender gap in publication history in hospital medicine, consistent with prior studies in hospital medicine that suggested gender disparities in scholarship.9,10 Increased focus will be needed in the future to ensure opportunities for scholarship are equitable for all faculty in hospital medicine.

Our findings suggest that scholarly productivity in academic hospital medicine remains a challenge. Prior studies have reported that less than half of academic hospitalists have ever published, and fewer than one in eight have received research funding.11,12 It is encouraging, however, that publications increase with time after residency. These data are consistent with the literature demonstrating a modest increase in hospitalists who had ever published, increasing from 43.0% in 2012 to 48.6% in 2020.12 Despite these trends, however, some early-career academic hospitalists report ambivalence toward academic productivity and promotion.13 Whether this ambivalence is the source of low scholarship output or the outcome of insufficient mentorship and limited research success is uncertain. But these factors, combined with the pressures of clinical productivity, the existing lack of mentorship, and inadequate protected research time represent barriers to successful scholarship in academic hospital medicine.3,14

Our study has several limitations. First, our inclusion criteria for the top 25 internal medicine residencies may have excluded hospital medicine divisions with substantial scholarly productivity. However, with 21 of the 25 programs listed on Doximity.com in the top 25 for internal medicine research funding, it is likely that our results overestimate scholarly productivity if compared to a complete, national cohort of AHMF.15 Second, our findings may not be generalizable to hospitalists who practice in nonacademic settings. Third, we were unable to account for differences in promotion criteria/tracks or scholarly output expectations between institutions. This limitation has been seen similarly in prior studies linking promotion and H-index.2 Furthermore, our study does not capture promotion via other pathways that may not depend on scholarly output, such as hospital leadership roles. Last, as data were abstracted from academic center websites, it is possible that not all information was accurate or updated. However, we randomly reevaluated 25% of hospital division webpages 6 months after our initial data collection and noted that all had been updated with new faculty and academic ranks, suggesting our data were accurate.

These data highlight that research productivity and academic promotion remain challenges in academic hospital medicine. Future studies may examine topics that include understanding pathways and milestones to promotion, reducing disparities in scholarship, and improving mentorship, protected time, and research funding in academic hospital medicine.

Hospital medicine has grown rapidly, with more than 50,000 hospitalists practicing nationally in 2016.1 Despite the remarkable increase in academic hospital medicine faculty (AHMF), scholarly productivity remains underdeveloped. Prior evidence suggests peer-reviewed publications remain an important aspect of promotion in academic hospital medicine.2 However, there are multiple barriers to robust scholarly productivity among AHMF, including inadequate mentorship,3 lack of protected scholarship time,4 and greater participation in nonclinical activities outside of peer-reviewed clinical research.5 Though research barriers have been described previously, the current state of scholarly productivity among AHMF has not been characterized. In this cross-sectional study, we describe the distribution of academic rank and scholarly output of a national sample of AHMF.

METHODS

Study Design and Data Source

We performed a cross-sectional study of AHMF at the top 25 internal medicine residency programs as determined by Doximity.com as of February 1, 2020 (Appendix Table 1). Between March and August 2020, two authors (NS, MT) visited each residency program’s website, identified all faculty listed as members of the hospital medicine program, and extracted demographic data, including degrees, sex, residency, medical school, year of residency graduation, completion of chief residency, completion of fellowship, and rank. We categorized all academic titles into full professor, associate professor, assistant professor, and instructor/lecturer. Missing information was supplemented by searching state licensing websites and Doximity.com. Sex was validated using Genderize.io. We queried the Scopus database for each AHMF’s name and affiliated institution to extract publications, citations, and H-index (metric of productivity and impact, derived from the number of publications and their associated citations).6 We categorized medical schools by rank (top 25, top 50, or unranked), as defined by the 2020 US News Best Medical Schools, sorted by research7 and by location (United States, international Caribbean, and international non-Caribbean). We excluded programs without hospital medicine section/division webpages and AHMF with nonpromotion titles such as “adjunct professor” or “acting professor” or those with missing data that could not be identified using these methods.

Analysis

Summary statistics were generated using means with standard deviations and medians with interquartile ranges. We evaluated postresidency years 6 to 10 and 14 to 18 as conservative time frames for promotion to associate and full professor, respectively. These windows account for time spent for additional degrees, instructor years, and alternative career pathways. Demographic differences between academic ranks were determined using chi-square and Kruskal-Wallis analyses.

Because promotion occurs sequentially, a proportional odds logistic regression model was used to evaluate the association of academic rank and H-index, number of years post residency, completion of chief residency, graduation from a top 25 medical school, and sex. Since not all programs have the instructor/lecturer rank, only assistant, associate, and full professors were included in this model. Significance was assessed with the likelihood ratio test. The proportional odds assumption was assessed using the score test. All adjusted odds ratios and their associated 95% confidence intervals were recorded. A two-tailed P value < .05 was considered significant for this study, and SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc) was used to conduct all analyses. This study was approved by the UT Southwestern Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Cohort Demographics

Of the top 25 internal medicine programs, 3 were excluded because they did not have websites that listed AHMF. Of the remaining 22 programs, we identified 1,829 AHMF. We excluded 166 AHMF because we could not identify title or year of residency graduation and 109 for having nonpromotion titles, leaving 1,554 AHMF (Appendix Figure). The cohort characteristics are described in Table 1.

Research Productivity

A total of 9,809 documents had been published by this cohort of academic hospitalists (Appendix Table 2). Overall mean (SD) and median (IQR) publications were 6.3 (24.3) and 0.0 (0.0-4.0), respectively. A total of 799 (51.4%) AHMF had no publications, 347 (22.3%) had one to three publications, 209 (13.4%) had 10 or more, and 39 (2.5%) had 50 or more. The median number of publications stratified by academic rank were 0.0 (IQR, 0.0-1.0) for instructors, 0.0 (IQR, 0.0-3.0) for assistant professors, 8.0 (IQR, 2.0-23.0) for associate professors, and 38.0 (IQR, 6.0-99.0) for full professors. Among men, 54.3% had published at least one manuscript, compared to 42.7% of women (P < .0001). The distribution of H-indices by years since residency graduation is shown in the Figure. The median number of documents published by faculty 6 to 10 years post residency was 1.0 (IQR, 0.0-4.0), with 46.8% of these faculty without a publication. For faculty 14 to 18 years post residency, the median number of documents was 3.0 (IQR, 0.0-11.0), with 30.1% of these faculty without a publication. Years post residency and academic rank were correlated with higher H-indices as well as more publications and citations (P < .0001).

Factors Associated With Academic Rank

Factors associated with rank are described in Appendix Table 3. In our multivariable ordinal regression model, H-index (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.16 per single H-index point; 95% CI, 1.12-1.20), years post residency graduation (aOR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.11-1.17), completion of chief residency (aOR, 2.46; 95% CI, 1.34-4.51), and graduation from a top 25 medical school (aOR, 2.10; 95% CI, 1.44-3.06) were associated with promotion.

DISCUSSION

In this cross-sectional analysis of more than 1,500 AHMF at the top 25 internal medicine residencies in the United States, 88.3% were instructors or assistant professors, while only 11.7% were associate or full professors. Furthermore, 51.4% were without a publication, and only 26.3% had published more than three manuscripts. Last, H-index, completion of a chief residency, years post residency, and graduation from a top 25 medical school were associated with higher academic rank.

Only 2.7% of the cohort were full professors, and 9.0% were associate professors. In comparison, academic cardiology faculty are 28.2% full professors and 22.9% associate professors.8 While the field of hospital medicine is relatively new, many faculty members had practiced for the expected duration of time for promotion consideration, with assistant professors or instructors constituting 89.9% of faculty at 6 to 10 years and 63.6% of faculty at 14 to 18 years post residency. We additionally observed a gender gap in publication history in hospital medicine, consistent with prior studies in hospital medicine that suggested gender disparities in scholarship.9,10 Increased focus will be needed in the future to ensure opportunities for scholarship are equitable for all faculty in hospital medicine.

Our findings suggest that scholarly productivity in academic hospital medicine remains a challenge. Prior studies have reported that less than half of academic hospitalists have ever published, and fewer than one in eight have received research funding.11,12 It is encouraging, however, that publications increase with time after residency. These data are consistent with the literature demonstrating a modest increase in hospitalists who had ever published, increasing from 43.0% in 2012 to 48.6% in 2020.12 Despite these trends, however, some early-career academic hospitalists report ambivalence toward academic productivity and promotion.13 Whether this ambivalence is the source of low scholarship output or the outcome of insufficient mentorship and limited research success is uncertain. But these factors, combined with the pressures of clinical productivity, the existing lack of mentorship, and inadequate protected research time represent barriers to successful scholarship in academic hospital medicine.3,14

Our study has several limitations. First, our inclusion criteria for the top 25 internal medicine residencies may have excluded hospital medicine divisions with substantial scholarly productivity. However, with 21 of the 25 programs listed on Doximity.com in the top 25 for internal medicine research funding, it is likely that our results overestimate scholarly productivity if compared to a complete, national cohort of AHMF.15 Second, our findings may not be generalizable to hospitalists who practice in nonacademic settings. Third, we were unable to account for differences in promotion criteria/tracks or scholarly output expectations between institutions. This limitation has been seen similarly in prior studies linking promotion and H-index.2 Furthermore, our study does not capture promotion via other pathways that may not depend on scholarly output, such as hospital leadership roles. Last, as data were abstracted from academic center websites, it is possible that not all information was accurate or updated. However, we randomly reevaluated 25% of hospital division webpages 6 months after our initial data collection and noted that all had been updated with new faculty and academic ranks, suggesting our data were accurate.

These data highlight that research productivity and academic promotion remain challenges in academic hospital medicine. Future studies may examine topics that include understanding pathways and milestones to promotion, reducing disparities in scholarship, and improving mentorship, protected time, and research funding in academic hospital medicine.

1. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000—the 20th anniversary of the hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1009-1011. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1607958

2. Leykum LK, Parekh VI, Sharpe B, Boonyasai RT, Centor RM. Tried and true: a survey of successfully promoted academic hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(7):411-415. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.894

3. Harrison R, Hunter AJ, Sharpe B, Auerbach AD. Survey of US academic hospitalist leaders about mentorship and academic activities in hospitalist groups. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(1):5-9. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.836

4. Cumbler E, Rendón P, Yirdaw E, et al. Keys to career success: resources and barriers identified by early career academic hospitalists. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(5):588-589. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4336-7

5. Flanders SA, Centor B, Weber V, McGinn T, DeSalvo K, Auerbach A. Challenges and opportunities in academic hospital medicine: report from the Academic Hospital Medicine Summit. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(4):240-246. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.497

6. Hirsch JE. An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(46):16569-16572. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0507655102

7. 2021 Best Medical Schools: Research. U.S. News & World Report. Accessed April 23, 2021. https://www.usnews.com/best-graduate-schools/top-medical-schools/research-rankings

8. Blumenthal DM, Olenski AR, Yeh RW, et al. Sex differences in faculty rank among academic cardiologists in the United States. Circulation. 2017;135(6):506-517. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.023520

9. Burden M, Frank MG, Keniston A, et al. Gender disparities in leadership and scholarly productivity of academic hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(8):481-485. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2340

10. Adler E, Hobbs A, Dhaliwal G, Babik JM. Gender differences in authorship of clinical problem-solving articles. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(8):475-478. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3465

11. Chopra V, Burden M, Jones CD, et al. State of research in adult hospital medicine: results of a national survey. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(4):207-211. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3136

12. Dang Do AN, Munchhof AM, Terry C, Emmett T, Kara A. Research and publication trends in hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):148-154. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2148

13. Cumbler E, Yirdaw E, Kneeland P, et al. What is career success for academic hospitalists? A qualitative analysis of early-career faculty perspectives. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(6):372-377. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2924

14. Reid MB, Misky GJ, Harrison RA, Sharpe B, Auerbach A, Glasheen JJ. Mentorship, productivity, and promotion among academic hospitalists. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):23-27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1892-5

15. Roskoski R Jr, Parslow TG. Ranking tables of NIH funding to US medical schools in 2019. Accessed April 23, 2021. http://www.brimr.org/NIH_Awards/2019/NIH_Awards_2019.htm

1. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000—the 20th anniversary of the hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1009-1011. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1607958

2. Leykum LK, Parekh VI, Sharpe B, Boonyasai RT, Centor RM. Tried and true: a survey of successfully promoted academic hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(7):411-415. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.894

3. Harrison R, Hunter AJ, Sharpe B, Auerbach AD. Survey of US academic hospitalist leaders about mentorship and academic activities in hospitalist groups. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(1):5-9. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.836

4. Cumbler E, Rendón P, Yirdaw E, et al. Keys to career success: resources and barriers identified by early career academic hospitalists. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(5):588-589. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4336-7

5. Flanders SA, Centor B, Weber V, McGinn T, DeSalvo K, Auerbach A. Challenges and opportunities in academic hospital medicine: report from the Academic Hospital Medicine Summit. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(4):240-246. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.497

6. Hirsch JE. An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(46):16569-16572. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0507655102

7. 2021 Best Medical Schools: Research. U.S. News & World Report. Accessed April 23, 2021. https://www.usnews.com/best-graduate-schools/top-medical-schools/research-rankings

8. Blumenthal DM, Olenski AR, Yeh RW, et al. Sex differences in faculty rank among academic cardiologists in the United States. Circulation. 2017;135(6):506-517. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.023520

9. Burden M, Frank MG, Keniston A, et al. Gender disparities in leadership and scholarly productivity of academic hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(8):481-485. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2340

10. Adler E, Hobbs A, Dhaliwal G, Babik JM. Gender differences in authorship of clinical problem-solving articles. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(8):475-478. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3465

11. Chopra V, Burden M, Jones CD, et al. State of research in adult hospital medicine: results of a national survey. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(4):207-211. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3136

12. Dang Do AN, Munchhof AM, Terry C, Emmett T, Kara A. Research and publication trends in hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):148-154. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2148

13. Cumbler E, Yirdaw E, Kneeland P, et al. What is career success for academic hospitalists? A qualitative analysis of early-career faculty perspectives. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(6):372-377. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2924

14. Reid MB, Misky GJ, Harrison RA, Sharpe B, Auerbach A, Glasheen JJ. Mentorship, productivity, and promotion among academic hospitalists. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):23-27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1892-5

15. Roskoski R Jr, Parslow TG. Ranking tables of NIH funding to US medical schools in 2019. Accessed April 23, 2021. http://www.brimr.org/NIH_Awards/2019/NIH_Awards_2019.htm

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Improving Respiratory Rate Accuracy in the Hospital: A Quality Improvement Initiative

Respiratory rate (RR) is an essential vital sign that is routinely measured for hospitalized adults. It is a strong predictor of adverse events.1,2 Therefore, RR is a key component of several widely used risk prediction scores, including the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS).3

Despite its clinical utility, RR is inaccurately measured.4-7 One reason for the inaccurate measurement of RR is that RR measurement, in contrast to that of other vital signs, is not automated. The gold-standard technique for measuring RR is the visual assessment of a resting patient. Thus, RR measurement is perceived as time-consuming. Clinical staff instead frequently approximate RR through brief observation.8-11

Given its clinical importance and widespread inaccuracy, we conducted a quality improvement (QI) initiative to improve RR accuracy.

METHODS

Design and Setting

We conducted an interdisciplinary QI initiative by using the plan–do–study–act (PDSA) methodology from July 2017 to February 2018. The initiative was set in a single adult 28-bed medical inpatient unit of a large, urban, safety-net hospital consisting of general internal medicine and hematology/oncology patients. Routine vital sign measurements on this unit occur at four- or six-hour intervals per physician orders and are performed by patient-care assistants (PCAs) who are nonregistered nursing support staff. PCAs use a vital signs cart equipped with automated tools to measure vital signs except for RR, which is manually assessed. PCAs are trained on vital sign measurements during a two-day onboarding orientation and four to six weeks of on-the-job training by experienced PCAs. PCAs are directly supervised by nursing operations managers. Formal continuing education programs for PCAs or performance audits of their clinical duties did not exist prior to our QI initiative.

Intervention

Intervention development addressing several important barriers and workflow inefficiencies was based on the direct observation of PCA workflow and information gathering by engaging stakeholders, including PCAs, nursing operations management, nursing leadership, and hospital administration (PDSA cycles 1-7 in Table). Our modified PCA vital sign workflow incorporated RR measurement during the approximate 30 seconds needed to complete automated blood pressure measurement as previously described.12 Nursing administration purchased three stopwatches (each $5 US) to attach to vital signs carts. One investigator (NK) participated in two monthly one-hour meetings, and three investigators (NK, KB, and SD) participated in 19 daily 15-minute huddles to conduct stakeholder engagement and educate and retrain PCAs on proper technique (total of 6.75 hours).

Evaluation

The primary aim of this QI initiative was to improve RR accuracy, which was evaluated using two distinct but complementary analyses: the prospective comparison of PCA-recorded RRs with gold-standard recorded RRs and the retrospective comparison of RRs recorded in electronic health records (EHR) on the intervention unit versus two control units. The secondary aims were to examine time to complete vital sign measurement and to assess whether the intervention was associated with a reduction in the incidence of SIRS specifically due to tachypnea.

Respiratory Rate Accuracy

PCA-recorded RRs were considered accurate if the RR was within ±2 breaths of a gold-standard RR measurement performed by a trained study member (NK or KB). We conducted gold-standard RR measurements for 100 observations pre- and postintervention within 30 minutes of PCA measurement to avoid Hawthorne bias.

We assessed the variability of recorded RRs in the EHR for all patients in the intervention unit as a proxy for accuracy. We hypothesized on the basis of prior research that improving the accuracy of RR measurement would increase the variability and normality of distribution in RRs.13 This is an approach that we have employed previously.7 The EHR cohort included consecutive hospitalizations by patients who were admitted to either the intervention unit or to one of two nonintervention general medicine inpatient units that served as concurrent controls. We grouped hospitalizations into a preintervention phase from March 1, 2017-July 22, 2017, a planning phase from July 23, 2017-December 3, 2017, and a postintervention phase from December 21, 2017-February 28, 2018. Hospitalizations during the two-week teaching phase from December 3, 2017-December 21, 2017 were excluded. We excluded vital signs obtained in the emergency department or in a location different from the patient’s admission unit. We qualitatively assessed RR distribution using histograms as we have done previously.7

We examined the distributions of RRs recorded in the EHR before and after intervention by individual PCAs on the intervention floor to assess for fidelity and adherence in the PCA uptake of the intervention.

Time

We compared the time to complete vital sign measurement among convenience samples of 50 unique observations pre- and postintervention using the Wilcoxon rank sum test.

SIRS Incidence

Since we hypothesized that improved RR accuracy would reduce falsely elevated RRs but have no impact on the other three SIRS criteria, we assessed changes in tachypnea-specific SIRS incidence, which was defined a priori as the presence of exactly two concurrent SIRS criteria, one of which was an elevated RR.3 We examined changes using a difference-in-differences approach with three different units of analysis (per vital sign measurement, hospital-day, and hospitalization; see footnote for Appendix Table 1 for methodological details. All analyses were conducted using STATA 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

Respiratory Rate Accuracy

Prior to the intervention, the median PCA RR was 18 (IQR 18-20) versus 12 (IQR 12-18) for the gold-standard RR (Appendix Figure 1), with only 36% of PCA measurements considered accurate. After the intervention, the median PCA-recorded RR was 14 (IQR 15-20) versus 14 (IQR 14-20) for the gold-standard RR and a RR accuracy of 58% (P < .001).

For our analyses on RR distribution using EHR data, we included 143,447 unique RRs (Appendix Table 2). After the intervention, the normality of the distribution of RRs on the intervention unit had increased, whereas those of RRs on the control units remained qualitatively similar pre- and postintervention (Appendix Figure 2).

Notable differences existed among the 11 individual PCAs (Figure) despite observing increased variability in PCA-recorded RRs postintervention. Some PCAs (numbers 2, 7, and 10) shifted their narrow RR interquartile range lower by several breaths/minute, whereas most other PCAs had a reduced median RR and widened interquartile range.

Time

Before the intervention, the median time to complete vital sign measurements was 2:36 (IQR 2:04-3:20). After the intervention, the time to complete vital signs decreased to 1:55 (IQR, 1:40-2:22; P < .001), which was 41 less seconds on average per vital sign set.

SIRS Incidence

The intervention was associated with a 3.3% reduction (95% CI, –6.4% to –0.005%) in tachypnea-specific SIRS incidence per hospital-day and a 7.8% reduction (95% CI, –13.5% to –2.2%) per hospitalization (Appendix Table 1). We also observed a modest reduction in overall SIRS incidence after the intervention (2.9% less per vital sign check, 4.6% less per hospital-day, and 3.2% less per hospitalization), although these reductions were not statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

Our QI initiative improved the absolute RR accuracy by 22%, saved PCAs 41 seconds on average per vital sign measurement, and decreased the absolute proportion of hospitalizations with tachypnea-specific SIRS by 7.8%. Our intervention is a novel, interdisciplinary, low-cost, low-effort, low-tech approach that addressed known challenges to accurate RR measurement,8,9,11 as well as the key barriers identified in our initial PDSA cycles. Our approach includes adding a time-keeping device to vital sign carts and standardizing a PCA vital sign workflow with increased efficiency. Lastly, this intervention is potentially scalable because stakeholder engagement, education, and retraining of the entire PCA staff for the unit required only 6.75 hours.

While our primary goal was to improve RR accuracy, our QI initiative also improved vital sign efficiency. By extrapolating our findings to an eight-hour PCA shift caring for eight patients who require vital sign checks every four hours, we estimated that our intervention would save approximately 16:24 minutes per PCA shift. This newfound time could be repurposed for other patient-care tasks or could be spent ensuring the accuracy of other vital signs given that accurate monitoring may be neglected because of time constraints.11 Additionally, the improvement in RR accuracy reduced falsely elevated RRs and thus lowered SIRS incidence specifically due to tachypnea. Given that EHR-based sepsis alerts are often based on SIRS criteria, improved RR accuracy may also improve alarm fatigue by reducing the rate of false-positive alerts.14

This initiative is not without limitations. Generalizability to other hospitals and even other units within the same hospital is uncertain. However, because this initiative was conducted within a safety-net hospital, we anticipate at least similar, if not increased, success in better-resourced hospitals. Second, the long-term durability of our intervention is unclear, although EHR RR variability remained steady for two months after our intervention (data not shown).

To ensure long-term sustainability and further improve RR accuracy, future PDSA cycles could include electing a PCA “vital signs champion” to reiterate the importance of RRs in clinical decision-making and ensure adherence to the modified workflow. Nursing champions act as persuasive change agents that disseminate and implement healthcare change,15 which may also be true of PCA champions. Additionally, future PDSA cycles can obviate the need for labor-intensive manual audits by leveraging EHR-based auditing to target education and retraining interventions to PCAs with minimal RR variability to optimize workflow adherence.

In conclusion, through a multipronged QI initiative we improved RR accuracy, increased the efficiency of vital sign measurement, and decreased SIRS incidence specifically due to tachypnea by reducing the number of falsely elevated RRs. This novel, low-cost, low-effort, low-tech approach can readily be implemented and disseminated in hospital inpatient settings.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the meaningful contributions of Mr. Sudarshaan Pathak, RN, Ms. Shirly Koduvathu, RN, and Ms. Judy Herrington MSN, RN in this multidisciplinary initiative. We thank Mr. Christopher McKintosh, RN for his support in data acquisition. Lastly, the authors would like to acknowledge all of the patient-care assistants involved in this QI initiative.

Disclosures

Dr. Makam reports grants from NIA/NIH, during the conduct of the study. All other authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This work is supported in part by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality-funded UT Southwestern Center for Patient-Centered Outcomes Research (R24HS022418). OKN is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K23HL133441), and ANM is funded by the National Institute on Aging (K23AG052603).

1. Fieselmann JF, Hendryx MS, Helms CM, Wakefield DS. Respiratory rate predicts cardiopulmonary arrest for internal medicine inpatients. J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8(7):354-360. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02600071.

2. Hodgetts TJ, Kenward G, Vlachonikolis IG, Payne S, Castle N. The identification of risk factors for cardiac arrest and formulation of activation criteria to alert a medical emergency team. Resuscitation. 2002;54(2):125-131. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0300-9572(02)00100-4.

3. Bone RC, Sibbald WJ, Sprung CL. The ACCP-SCCM consensus conference on sepsis and organ failure. Chest. 1992;101(6):1481-1483.

4. Lovett PB, Buchwald JM, Sturmann K, Bijur P. The vexatious vital: neither clinical measurements by nurses nor an electronic monitor provides accurate measurements of respiratory rate in triage. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;45(1):68-76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.06.016.

5. Chen J, Hillman K, Bellomo R, et al. The impact of introducing medical emergency team system on the documentations of vital signs. Resuscitation. 2009;80(1):35-43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2008.10.009.

6. Leuvan CH, Mitchell I. Missed opportunities? An observational study of vital sign measurements. Crit Care Resusc. 2008;10(2):111-115.

7. Badawy J, Nguyen OK, Clark C, Halm EA, Makam AN. Is everyone really breathing 20 times a minute? Assessing epidemiology and variation in recorded respiratory rate in hospitalised adults. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017;26(10):832-836. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2017-006671.

8. Chua WL, Mackey S, Ng EK, Liaw SY. Front line nurses’ experiences with deteriorating ward patients: a qualitative study. Int Nurs Rev. 2013;60(4):501-509. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12061.

9. De Meester K, Van Bogaert P, Clarke SP, Bossaert L. In-hospital mortality after serious adverse events on medical and surgical nursing units: a mixed methods study. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(15-16):2308-2317. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04154.x.

10. Cheng AC, Black JF, Buising KL. Respiratory rate: the neglected vital sign. Med J Aust. 2008;189(9):531. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb02163.x.

11. Mok W, Wang W, Cooper S, Ang EN, Liaw SY. Attitudes towards vital signs monitoring in the detection of clinical deterioration: scale development and survey of ward nurses. Int J Qual Health Care. 2015;27(3):207-213. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzv019.

12. Keshvani N, Berger K, Nguyen OK, Makam AN. Roadmap for improving the accuracy of respiratory rate measurements. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27(8):e5. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007516.

13. Semler MW, Stover DG, Copland AP, et al. Flash mob research: a single-day, multicenter, resident-directed study of respiratory rate. Chest. 2013;143(6):1740-1744. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.12-1837.

14. Makam AN, Nguyen OK, Auerbach AD. Diagnostic accuracy and effectiveness of automated electronic sepsis alert systems: a systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(6):396-402. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2347.

15. Ploeg J, Skelly J, Rowan M, et al. The role of nursing best practice champions in diffusing practice guidelines: a mixed methods study. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2010;7(4):238-251. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6787.2010.00202.x.

Respiratory rate (RR) is an essential vital sign that is routinely measured for hospitalized adults. It is a strong predictor of adverse events.1,2 Therefore, RR is a key component of several widely used risk prediction scores, including the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS).3

Despite its clinical utility, RR is inaccurately measured.4-7 One reason for the inaccurate measurement of RR is that RR measurement, in contrast to that of other vital signs, is not automated. The gold-standard technique for measuring RR is the visual assessment of a resting patient. Thus, RR measurement is perceived as time-consuming. Clinical staff instead frequently approximate RR through brief observation.8-11

Given its clinical importance and widespread inaccuracy, we conducted a quality improvement (QI) initiative to improve RR accuracy.

METHODS

Design and Setting

We conducted an interdisciplinary QI initiative by using the plan–do–study–act (PDSA) methodology from July 2017 to February 2018. The initiative was set in a single adult 28-bed medical inpatient unit of a large, urban, safety-net hospital consisting of general internal medicine and hematology/oncology patients. Routine vital sign measurements on this unit occur at four- or six-hour intervals per physician orders and are performed by patient-care assistants (PCAs) who are nonregistered nursing support staff. PCAs use a vital signs cart equipped with automated tools to measure vital signs except for RR, which is manually assessed. PCAs are trained on vital sign measurements during a two-day onboarding orientation and four to six weeks of on-the-job training by experienced PCAs. PCAs are directly supervised by nursing operations managers. Formal continuing education programs for PCAs or performance audits of their clinical duties did not exist prior to our QI initiative.

Intervention

Intervention development addressing several important barriers and workflow inefficiencies was based on the direct observation of PCA workflow and information gathering by engaging stakeholders, including PCAs, nursing operations management, nursing leadership, and hospital administration (PDSA cycles 1-7 in Table). Our modified PCA vital sign workflow incorporated RR measurement during the approximate 30 seconds needed to complete automated blood pressure measurement as previously described.12 Nursing administration purchased three stopwatches (each $5 US) to attach to vital signs carts. One investigator (NK) participated in two monthly one-hour meetings, and three investigators (NK, KB, and SD) participated in 19 daily 15-minute huddles to conduct stakeholder engagement and educate and retrain PCAs on proper technique (total of 6.75 hours).

Evaluation

The primary aim of this QI initiative was to improve RR accuracy, which was evaluated using two distinct but complementary analyses: the prospective comparison of PCA-recorded RRs with gold-standard recorded RRs and the retrospective comparison of RRs recorded in electronic health records (EHR) on the intervention unit versus two control units. The secondary aims were to examine time to complete vital sign measurement and to assess whether the intervention was associated with a reduction in the incidence of SIRS specifically due to tachypnea.

Respiratory Rate Accuracy

PCA-recorded RRs were considered accurate if the RR was within ±2 breaths of a gold-standard RR measurement performed by a trained study member (NK or KB). We conducted gold-standard RR measurements for 100 observations pre- and postintervention within 30 minutes of PCA measurement to avoid Hawthorne bias.

We assessed the variability of recorded RRs in the EHR for all patients in the intervention unit as a proxy for accuracy. We hypothesized on the basis of prior research that improving the accuracy of RR measurement would increase the variability and normality of distribution in RRs.13 This is an approach that we have employed previously.7 The EHR cohort included consecutive hospitalizations by patients who were admitted to either the intervention unit or to one of two nonintervention general medicine inpatient units that served as concurrent controls. We grouped hospitalizations into a preintervention phase from March 1, 2017-July 22, 2017, a planning phase from July 23, 2017-December 3, 2017, and a postintervention phase from December 21, 2017-February 28, 2018. Hospitalizations during the two-week teaching phase from December 3, 2017-December 21, 2017 were excluded. We excluded vital signs obtained in the emergency department or in a location different from the patient’s admission unit. We qualitatively assessed RR distribution using histograms as we have done previously.7

We examined the distributions of RRs recorded in the EHR before and after intervention by individual PCAs on the intervention floor to assess for fidelity and adherence in the PCA uptake of the intervention.

Time

We compared the time to complete vital sign measurement among convenience samples of 50 unique observations pre- and postintervention using the Wilcoxon rank sum test.

SIRS Incidence

Since we hypothesized that improved RR accuracy would reduce falsely elevated RRs but have no impact on the other three SIRS criteria, we assessed changes in tachypnea-specific SIRS incidence, which was defined a priori as the presence of exactly two concurrent SIRS criteria, one of which was an elevated RR.3 We examined changes using a difference-in-differences approach with three different units of analysis (per vital sign measurement, hospital-day, and hospitalization; see footnote for Appendix Table 1 for methodological details. All analyses were conducted using STATA 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

Respiratory Rate Accuracy

Prior to the intervention, the median PCA RR was 18 (IQR 18-20) versus 12 (IQR 12-18) for the gold-standard RR (Appendix Figure 1), with only 36% of PCA measurements considered accurate. After the intervention, the median PCA-recorded RR was 14 (IQR 15-20) versus 14 (IQR 14-20) for the gold-standard RR and a RR accuracy of 58% (P < .001).

For our analyses on RR distribution using EHR data, we included 143,447 unique RRs (Appendix Table 2). After the intervention, the normality of the distribution of RRs on the intervention unit had increased, whereas those of RRs on the control units remained qualitatively similar pre- and postintervention (Appendix Figure 2).

Notable differences existed among the 11 individual PCAs (Figure) despite observing increased variability in PCA-recorded RRs postintervention. Some PCAs (numbers 2, 7, and 10) shifted their narrow RR interquartile range lower by several breaths/minute, whereas most other PCAs had a reduced median RR and widened interquartile range.

Time

Before the intervention, the median time to complete vital sign measurements was 2:36 (IQR 2:04-3:20). After the intervention, the time to complete vital signs decreased to 1:55 (IQR, 1:40-2:22; P < .001), which was 41 less seconds on average per vital sign set.

SIRS Incidence

The intervention was associated with a 3.3% reduction (95% CI, –6.4% to –0.005%) in tachypnea-specific SIRS incidence per hospital-day and a 7.8% reduction (95% CI, –13.5% to –2.2%) per hospitalization (Appendix Table 1). We also observed a modest reduction in overall SIRS incidence after the intervention (2.9% less per vital sign check, 4.6% less per hospital-day, and 3.2% less per hospitalization), although these reductions were not statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

Our QI initiative improved the absolute RR accuracy by 22%, saved PCAs 41 seconds on average per vital sign measurement, and decreased the absolute proportion of hospitalizations with tachypnea-specific SIRS by 7.8%. Our intervention is a novel, interdisciplinary, low-cost, low-effort, low-tech approach that addressed known challenges to accurate RR measurement,8,9,11 as well as the key barriers identified in our initial PDSA cycles. Our approach includes adding a time-keeping device to vital sign carts and standardizing a PCA vital sign workflow with increased efficiency. Lastly, this intervention is potentially scalable because stakeholder engagement, education, and retraining of the entire PCA staff for the unit required only 6.75 hours.

While our primary goal was to improve RR accuracy, our QI initiative also improved vital sign efficiency. By extrapolating our findings to an eight-hour PCA shift caring for eight patients who require vital sign checks every four hours, we estimated that our intervention would save approximately 16:24 minutes per PCA shift. This newfound time could be repurposed for other patient-care tasks or could be spent ensuring the accuracy of other vital signs given that accurate monitoring may be neglected because of time constraints.11 Additionally, the improvement in RR accuracy reduced falsely elevated RRs and thus lowered SIRS incidence specifically due to tachypnea. Given that EHR-based sepsis alerts are often based on SIRS criteria, improved RR accuracy may also improve alarm fatigue by reducing the rate of false-positive alerts.14

This initiative is not without limitations. Generalizability to other hospitals and even other units within the same hospital is uncertain. However, because this initiative was conducted within a safety-net hospital, we anticipate at least similar, if not increased, success in better-resourced hospitals. Second, the long-term durability of our intervention is unclear, although EHR RR variability remained steady for two months after our intervention (data not shown).

To ensure long-term sustainability and further improve RR accuracy, future PDSA cycles could include electing a PCA “vital signs champion” to reiterate the importance of RRs in clinical decision-making and ensure adherence to the modified workflow. Nursing champions act as persuasive change agents that disseminate and implement healthcare change,15 which may also be true of PCA champions. Additionally, future PDSA cycles can obviate the need for labor-intensive manual audits by leveraging EHR-based auditing to target education and retraining interventions to PCAs with minimal RR variability to optimize workflow adherence.

In conclusion, through a multipronged QI initiative we improved RR accuracy, increased the efficiency of vital sign measurement, and decreased SIRS incidence specifically due to tachypnea by reducing the number of falsely elevated RRs. This novel, low-cost, low-effort, low-tech approach can readily be implemented and disseminated in hospital inpatient settings.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the meaningful contributions of Mr. Sudarshaan Pathak, RN, Ms. Shirly Koduvathu, RN, and Ms. Judy Herrington MSN, RN in this multidisciplinary initiative. We thank Mr. Christopher McKintosh, RN for his support in data acquisition. Lastly, the authors would like to acknowledge all of the patient-care assistants involved in this QI initiative.

Disclosures

Dr. Makam reports grants from NIA/NIH, during the conduct of the study. All other authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This work is supported in part by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality-funded UT Southwestern Center for Patient-Centered Outcomes Research (R24HS022418). OKN is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K23HL133441), and ANM is funded by the National Institute on Aging (K23AG052603).

Respiratory rate (RR) is an essential vital sign that is routinely measured for hospitalized adults. It is a strong predictor of adverse events.1,2 Therefore, RR is a key component of several widely used risk prediction scores, including the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS).3

Despite its clinical utility, RR is inaccurately measured.4-7 One reason for the inaccurate measurement of RR is that RR measurement, in contrast to that of other vital signs, is not automated. The gold-standard technique for measuring RR is the visual assessment of a resting patient. Thus, RR measurement is perceived as time-consuming. Clinical staff instead frequently approximate RR through brief observation.8-11

Given its clinical importance and widespread inaccuracy, we conducted a quality improvement (QI) initiative to improve RR accuracy.

METHODS

Design and Setting

We conducted an interdisciplinary QI initiative by using the plan–do–study–act (PDSA) methodology from July 2017 to February 2018. The initiative was set in a single adult 28-bed medical inpatient unit of a large, urban, safety-net hospital consisting of general internal medicine and hematology/oncology patients. Routine vital sign measurements on this unit occur at four- or six-hour intervals per physician orders and are performed by patient-care assistants (PCAs) who are nonregistered nursing support staff. PCAs use a vital signs cart equipped with automated tools to measure vital signs except for RR, which is manually assessed. PCAs are trained on vital sign measurements during a two-day onboarding orientation and four to six weeks of on-the-job training by experienced PCAs. PCAs are directly supervised by nursing operations managers. Formal continuing education programs for PCAs or performance audits of their clinical duties did not exist prior to our QI initiative.

Intervention

Intervention development addressing several important barriers and workflow inefficiencies was based on the direct observation of PCA workflow and information gathering by engaging stakeholders, including PCAs, nursing operations management, nursing leadership, and hospital administration (PDSA cycles 1-7 in Table). Our modified PCA vital sign workflow incorporated RR measurement during the approximate 30 seconds needed to complete automated blood pressure measurement as previously described.12 Nursing administration purchased three stopwatches (each $5 US) to attach to vital signs carts. One investigator (NK) participated in two monthly one-hour meetings, and three investigators (NK, KB, and SD) participated in 19 daily 15-minute huddles to conduct stakeholder engagement and educate and retrain PCAs on proper technique (total of 6.75 hours).

Evaluation

The primary aim of this QI initiative was to improve RR accuracy, which was evaluated using two distinct but complementary analyses: the prospective comparison of PCA-recorded RRs with gold-standard recorded RRs and the retrospective comparison of RRs recorded in electronic health records (EHR) on the intervention unit versus two control units. The secondary aims were to examine time to complete vital sign measurement and to assess whether the intervention was associated with a reduction in the incidence of SIRS specifically due to tachypnea.

Respiratory Rate Accuracy

PCA-recorded RRs were considered accurate if the RR was within ±2 breaths of a gold-standard RR measurement performed by a trained study member (NK or KB). We conducted gold-standard RR measurements for 100 observations pre- and postintervention within 30 minutes of PCA measurement to avoid Hawthorne bias.

We assessed the variability of recorded RRs in the EHR for all patients in the intervention unit as a proxy for accuracy. We hypothesized on the basis of prior research that improving the accuracy of RR measurement would increase the variability and normality of distribution in RRs.13 This is an approach that we have employed previously.7 The EHR cohort included consecutive hospitalizations by patients who were admitted to either the intervention unit or to one of two nonintervention general medicine inpatient units that served as concurrent controls. We grouped hospitalizations into a preintervention phase from March 1, 2017-July 22, 2017, a planning phase from July 23, 2017-December 3, 2017, and a postintervention phase from December 21, 2017-February 28, 2018. Hospitalizations during the two-week teaching phase from December 3, 2017-December 21, 2017 were excluded. We excluded vital signs obtained in the emergency department or in a location different from the patient’s admission unit. We qualitatively assessed RR distribution using histograms as we have done previously.7

We examined the distributions of RRs recorded in the EHR before and after intervention by individual PCAs on the intervention floor to assess for fidelity and adherence in the PCA uptake of the intervention.

Time

We compared the time to complete vital sign measurement among convenience samples of 50 unique observations pre- and postintervention using the Wilcoxon rank sum test.

SIRS Incidence

Since we hypothesized that improved RR accuracy would reduce falsely elevated RRs but have no impact on the other three SIRS criteria, we assessed changes in tachypnea-specific SIRS incidence, which was defined a priori as the presence of exactly two concurrent SIRS criteria, one of which was an elevated RR.3 We examined changes using a difference-in-differences approach with three different units of analysis (per vital sign measurement, hospital-day, and hospitalization; see footnote for Appendix Table 1 for methodological details. All analyses were conducted using STATA 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

Respiratory Rate Accuracy

Prior to the intervention, the median PCA RR was 18 (IQR 18-20) versus 12 (IQR 12-18) for the gold-standard RR (Appendix Figure 1), with only 36% of PCA measurements considered accurate. After the intervention, the median PCA-recorded RR was 14 (IQR 15-20) versus 14 (IQR 14-20) for the gold-standard RR and a RR accuracy of 58% (P < .001).

For our analyses on RR distribution using EHR data, we included 143,447 unique RRs (Appendix Table 2). After the intervention, the normality of the distribution of RRs on the intervention unit had increased, whereas those of RRs on the control units remained qualitatively similar pre- and postintervention (Appendix Figure 2).

Notable differences existed among the 11 individual PCAs (Figure) despite observing increased variability in PCA-recorded RRs postintervention. Some PCAs (numbers 2, 7, and 10) shifted their narrow RR interquartile range lower by several breaths/minute, whereas most other PCAs had a reduced median RR and widened interquartile range.

Time

Before the intervention, the median time to complete vital sign measurements was 2:36 (IQR 2:04-3:20). After the intervention, the time to complete vital signs decreased to 1:55 (IQR, 1:40-2:22; P < .001), which was 41 less seconds on average per vital sign set.

SIRS Incidence

The intervention was associated with a 3.3% reduction (95% CI, –6.4% to –0.005%) in tachypnea-specific SIRS incidence per hospital-day and a 7.8% reduction (95% CI, –13.5% to –2.2%) per hospitalization (Appendix Table 1). We also observed a modest reduction in overall SIRS incidence after the intervention (2.9% less per vital sign check, 4.6% less per hospital-day, and 3.2% less per hospitalization), although these reductions were not statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

Our QI initiative improved the absolute RR accuracy by 22%, saved PCAs 41 seconds on average per vital sign measurement, and decreased the absolute proportion of hospitalizations with tachypnea-specific SIRS by 7.8%. Our intervention is a novel, interdisciplinary, low-cost, low-effort, low-tech approach that addressed known challenges to accurate RR measurement,8,9,11 as well as the key barriers identified in our initial PDSA cycles. Our approach includes adding a time-keeping device to vital sign carts and standardizing a PCA vital sign workflow with increased efficiency. Lastly, this intervention is potentially scalable because stakeholder engagement, education, and retraining of the entire PCA staff for the unit required only 6.75 hours.

While our primary goal was to improve RR accuracy, our QI initiative also improved vital sign efficiency. By extrapolating our findings to an eight-hour PCA shift caring for eight patients who require vital sign checks every four hours, we estimated that our intervention would save approximately 16:24 minutes per PCA shift. This newfound time could be repurposed for other patient-care tasks or could be spent ensuring the accuracy of other vital signs given that accurate monitoring may be neglected because of time constraints.11 Additionally, the improvement in RR accuracy reduced falsely elevated RRs and thus lowered SIRS incidence specifically due to tachypnea. Given that EHR-based sepsis alerts are often based on SIRS criteria, improved RR accuracy may also improve alarm fatigue by reducing the rate of false-positive alerts.14

This initiative is not without limitations. Generalizability to other hospitals and even other units within the same hospital is uncertain. However, because this initiative was conducted within a safety-net hospital, we anticipate at least similar, if not increased, success in better-resourced hospitals. Second, the long-term durability of our intervention is unclear, although EHR RR variability remained steady for two months after our intervention (data not shown).

To ensure long-term sustainability and further improve RR accuracy, future PDSA cycles could include electing a PCA “vital signs champion” to reiterate the importance of RRs in clinical decision-making and ensure adherence to the modified workflow. Nursing champions act as persuasive change agents that disseminate and implement healthcare change,15 which may also be true of PCA champions. Additionally, future PDSA cycles can obviate the need for labor-intensive manual audits by leveraging EHR-based auditing to target education and retraining interventions to PCAs with minimal RR variability to optimize workflow adherence.

In conclusion, through a multipronged QI initiative we improved RR accuracy, increased the efficiency of vital sign measurement, and decreased SIRS incidence specifically due to tachypnea by reducing the number of falsely elevated RRs. This novel, low-cost, low-effort, low-tech approach can readily be implemented and disseminated in hospital inpatient settings.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the meaningful contributions of Mr. Sudarshaan Pathak, RN, Ms. Shirly Koduvathu, RN, and Ms. Judy Herrington MSN, RN in this multidisciplinary initiative. We thank Mr. Christopher McKintosh, RN for his support in data acquisition. Lastly, the authors would like to acknowledge all of the patient-care assistants involved in this QI initiative.

Disclosures

Dr. Makam reports grants from NIA/NIH, during the conduct of the study. All other authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This work is supported in part by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality-funded UT Southwestern Center for Patient-Centered Outcomes Research (R24HS022418). OKN is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K23HL133441), and ANM is funded by the National Institute on Aging (K23AG052603).

1. Fieselmann JF, Hendryx MS, Helms CM, Wakefield DS. Respiratory rate predicts cardiopulmonary arrest for internal medicine inpatients. J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8(7):354-360. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02600071.

2. Hodgetts TJ, Kenward G, Vlachonikolis IG, Payne S, Castle N. The identification of risk factors for cardiac arrest and formulation of activation criteria to alert a medical emergency team. Resuscitation. 2002;54(2):125-131. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0300-9572(02)00100-4.

3. Bone RC, Sibbald WJ, Sprung CL. The ACCP-SCCM consensus conference on sepsis and organ failure. Chest. 1992;101(6):1481-1483.

4. Lovett PB, Buchwald JM, Sturmann K, Bijur P. The vexatious vital: neither clinical measurements by nurses nor an electronic monitor provides accurate measurements of respiratory rate in triage. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;45(1):68-76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.06.016.

5. Chen J, Hillman K, Bellomo R, et al. The impact of introducing medical emergency team system on the documentations of vital signs. Resuscitation. 2009;80(1):35-43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2008.10.009.

6. Leuvan CH, Mitchell I. Missed opportunities? An observational study of vital sign measurements. Crit Care Resusc. 2008;10(2):111-115.

7. Badawy J, Nguyen OK, Clark C, Halm EA, Makam AN. Is everyone really breathing 20 times a minute? Assessing epidemiology and variation in recorded respiratory rate in hospitalised adults. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017;26(10):832-836. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2017-006671.

8. Chua WL, Mackey S, Ng EK, Liaw SY. Front line nurses’ experiences with deteriorating ward patients: a qualitative study. Int Nurs Rev. 2013;60(4):501-509. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12061.

9. De Meester K, Van Bogaert P, Clarke SP, Bossaert L. In-hospital mortality after serious adverse events on medical and surgical nursing units: a mixed methods study. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(15-16):2308-2317. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04154.x.

10. Cheng AC, Black JF, Buising KL. Respiratory rate: the neglected vital sign. Med J Aust. 2008;189(9):531. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb02163.x.

11. Mok W, Wang W, Cooper S, Ang EN, Liaw SY. Attitudes towards vital signs monitoring in the detection of clinical deterioration: scale development and survey of ward nurses. Int J Qual Health Care. 2015;27(3):207-213. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzv019.

12. Keshvani N, Berger K, Nguyen OK, Makam AN. Roadmap for improving the accuracy of respiratory rate measurements. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27(8):e5. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007516.

13. Semler MW, Stover DG, Copland AP, et al. Flash mob research: a single-day, multicenter, resident-directed study of respiratory rate. Chest. 2013;143(6):1740-1744. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.12-1837.