User login

Hyperpigmented Macules Caused by Burrowing Bugs (Cydnidae) May Mimic More Serious Conditions

Hyperpigmented Macules Caused by Burrowing Bugs (Cydnidae) May Mimic More Serious Conditions

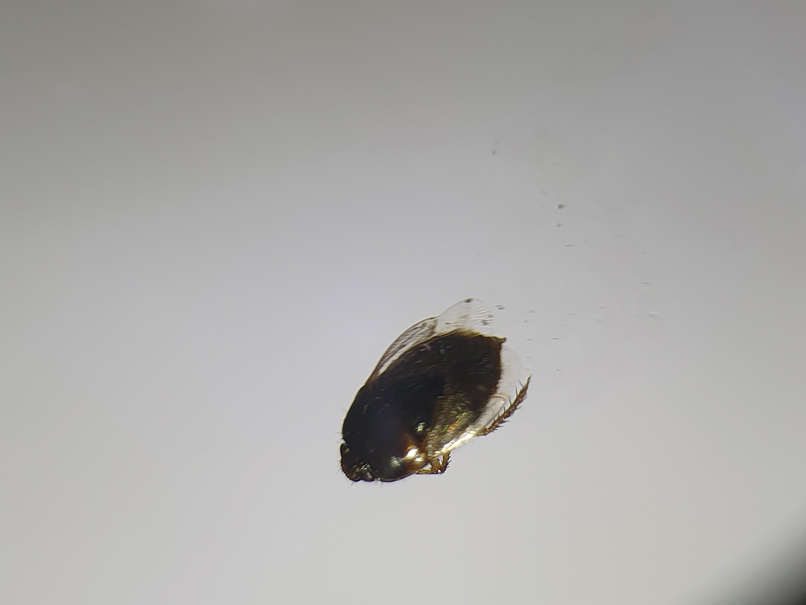

Cydnidae is a family of small to medium-sized shield bugs with spiny legs that commonly are known as burrowing bugs (or burrower bugs). The family Cydnidae includes more than 100 genera and approximately 600 species worldwide.1 These insects are arthropods of the order Hemiptera (suborder: Heteroptera; superfamily: Pentatomoidae) and largely are concentrated in tropical and temperate regions. Approximately 145 species have been recorded in the Neotropical Region and have been included in the subfamilies Amnestinae, Cephalocteinae, and Sehirinae, in addition to Cydnidae.2 Burrowing bugs are ovoid in shape and 2 to 20 mm in length and morphologically are well adapted for burrowing. Their life span is 100 to 300 days. Being phytophagous, they burrow to feed on plants and roots. Adult burrowing bugs have wings and can fly. They have specialized glands located in either the abdomen (nymph) or thorax (adult) that secrete odorous chemicals for self-protection.3 The secretions contain hydrocarbonates that function as repellents and danger signals, can cause paralysis in prey, and act as a chemoattractant for mates.4-6 They also cause hyperpigmentation upon contact with the skin.

In this article, we present a series of cases from the same community to demonstrate the characteristic features of hyperpigmented macules caused by exposure to burrowing bugs. Dermatologists should be aware of this entity to prevent misdiagnosis and unnecessary investigations and treatment.

Case Series

A 36-year-old woman and 6 children (age range, 6-12 years) presented with a widespread, acute, brown-pigmented, macular eruption with lesions that increased in number over a 1-week period. All 7 patients resided in the same locality and were otherwise systemically healthy. Initially, the index case, a 7-year-old girl, was referred to our tertiary care center by a dermatologist with a provisional diagnosis of idiopathic macular eruptive pigmentation. The patient’s mother recalled noticing a tiny black insect on the child's scalp that left pigment on the skin when she crushed it between her fingers. The rest of the patients presented over the next few days: 3 of the children belonged to the same household as the index case, and there was history of all 6 children playing in the neighborhood park during late evening hours. The adult patient was the parent of one of the affected children. The lesions were associated with mild itching and tingling in 3 children but were asymptomatic in the other patients.

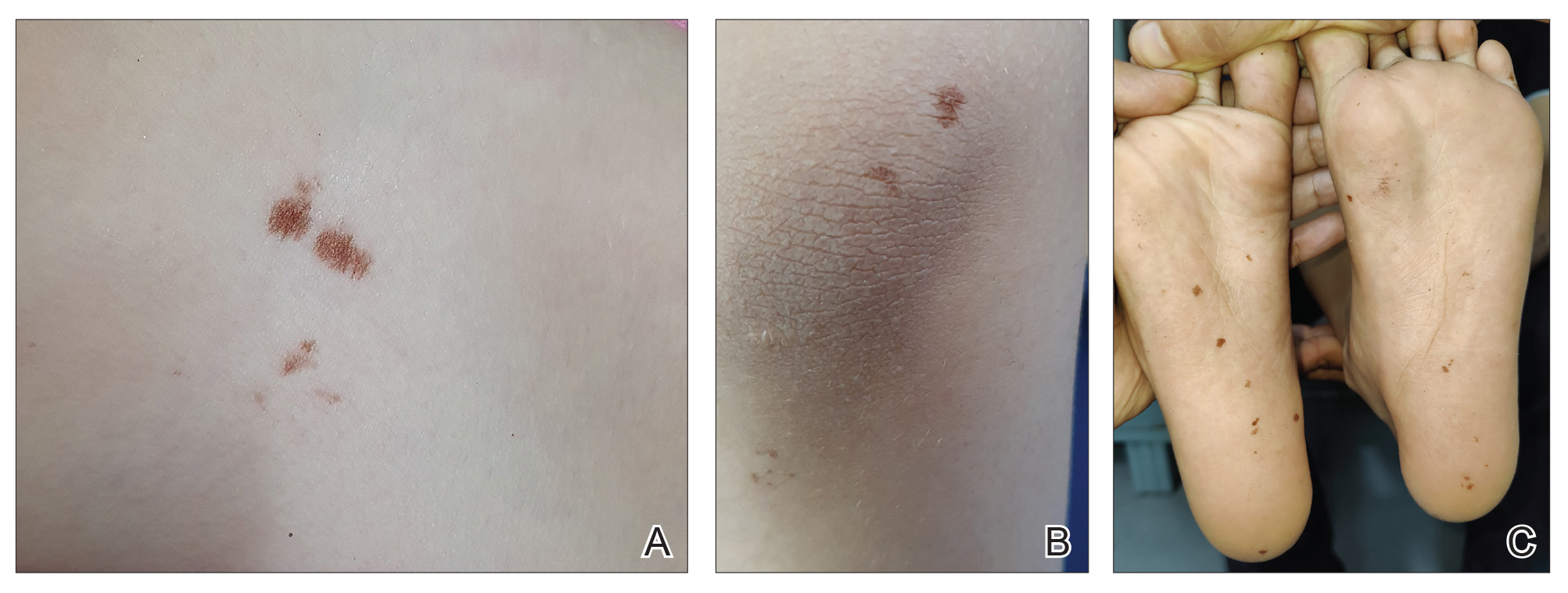

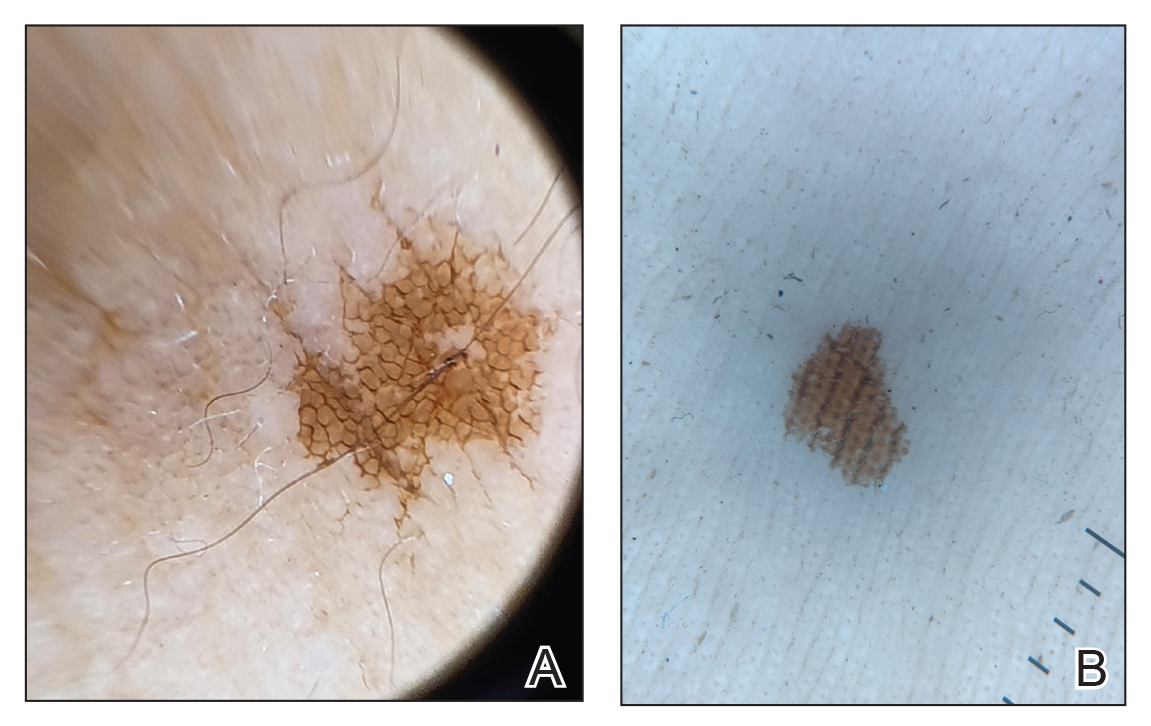

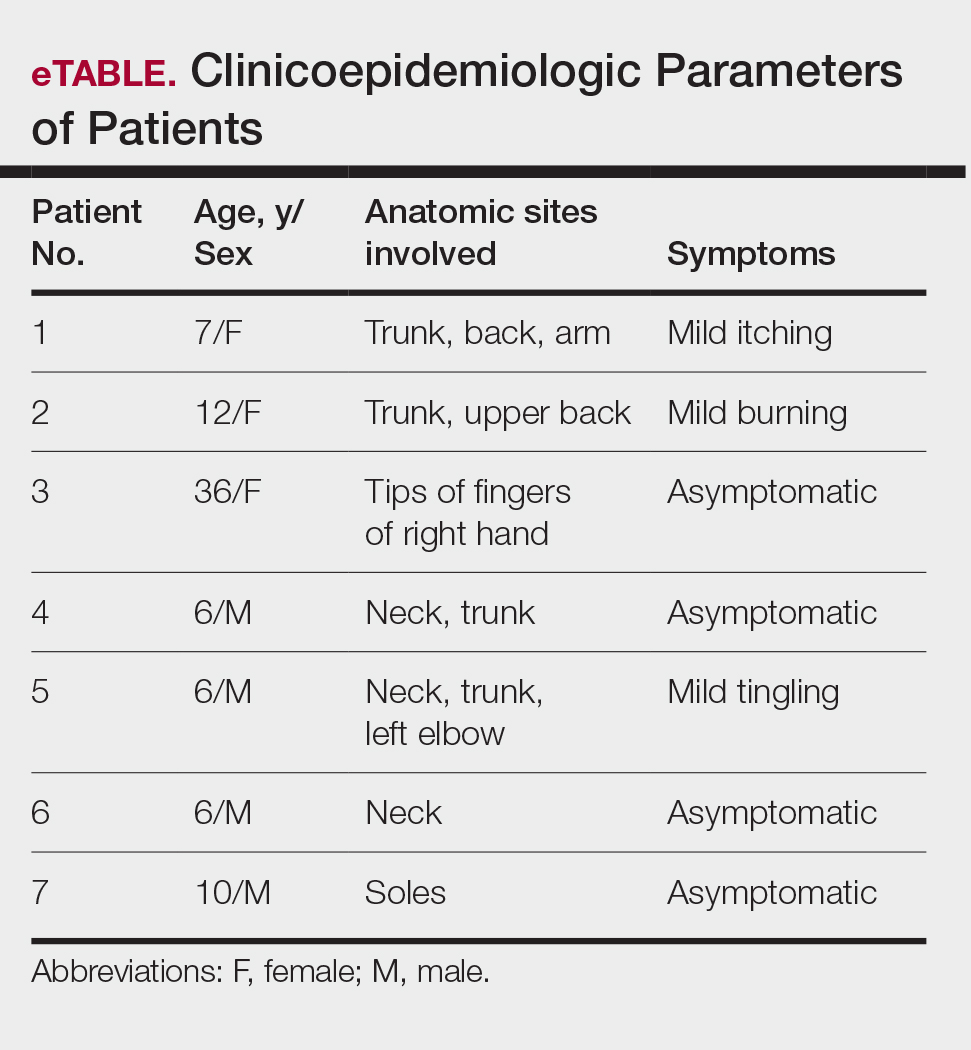

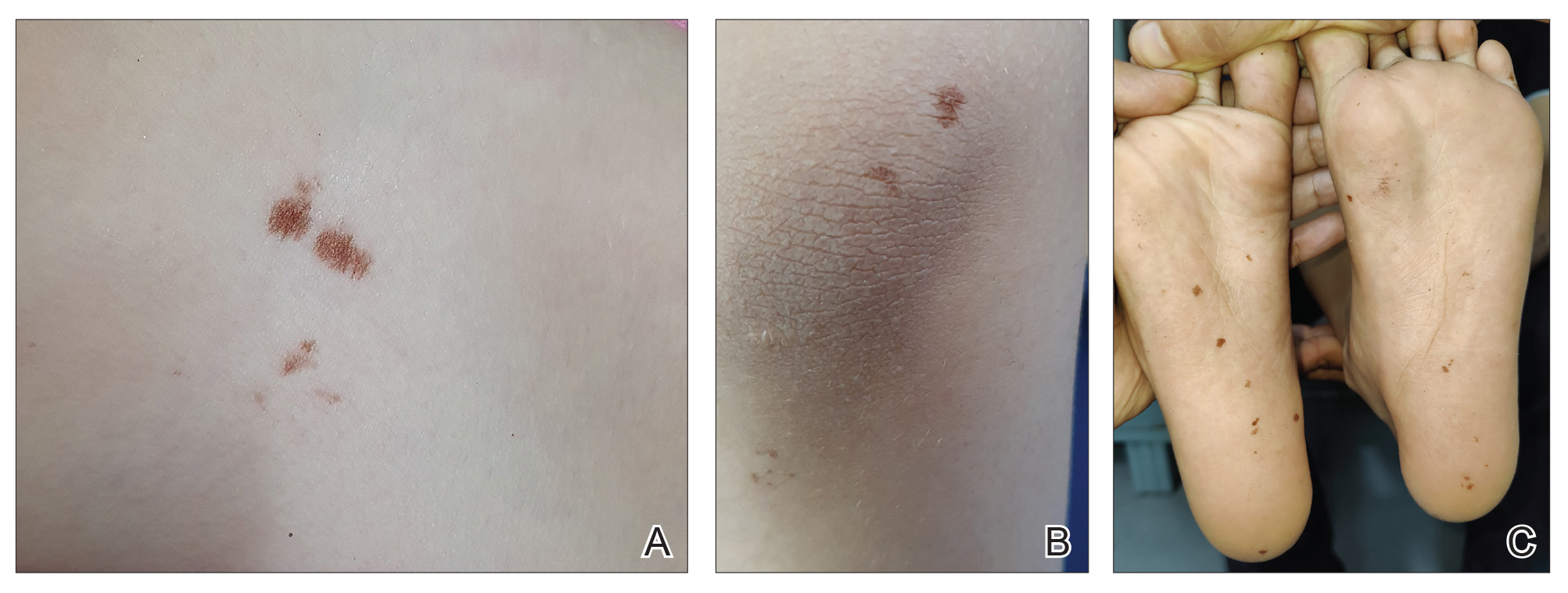

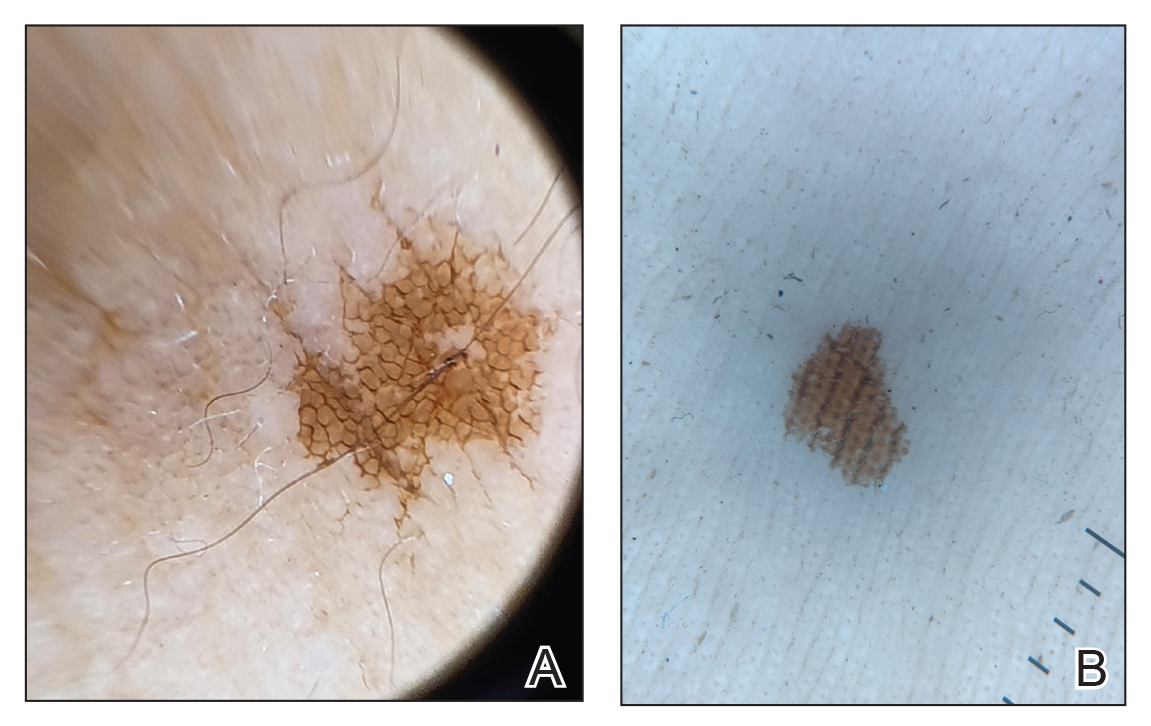

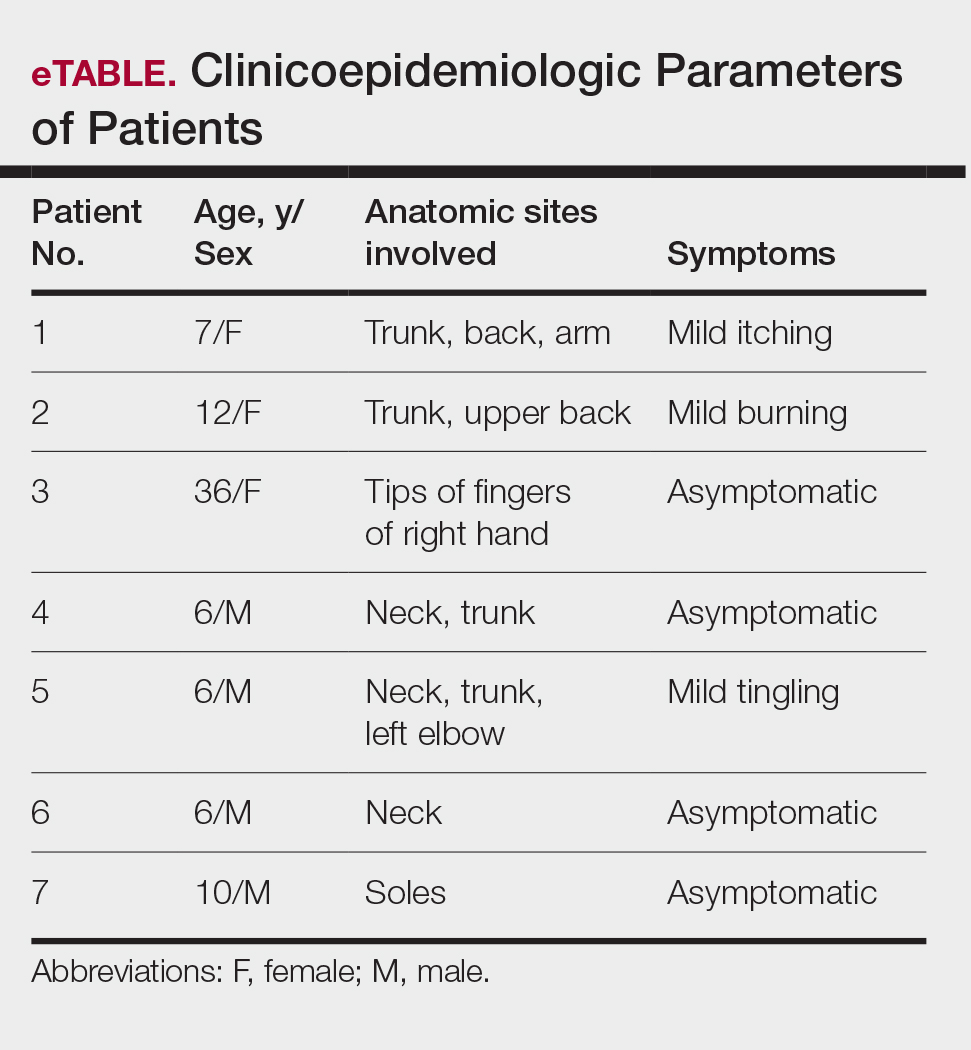

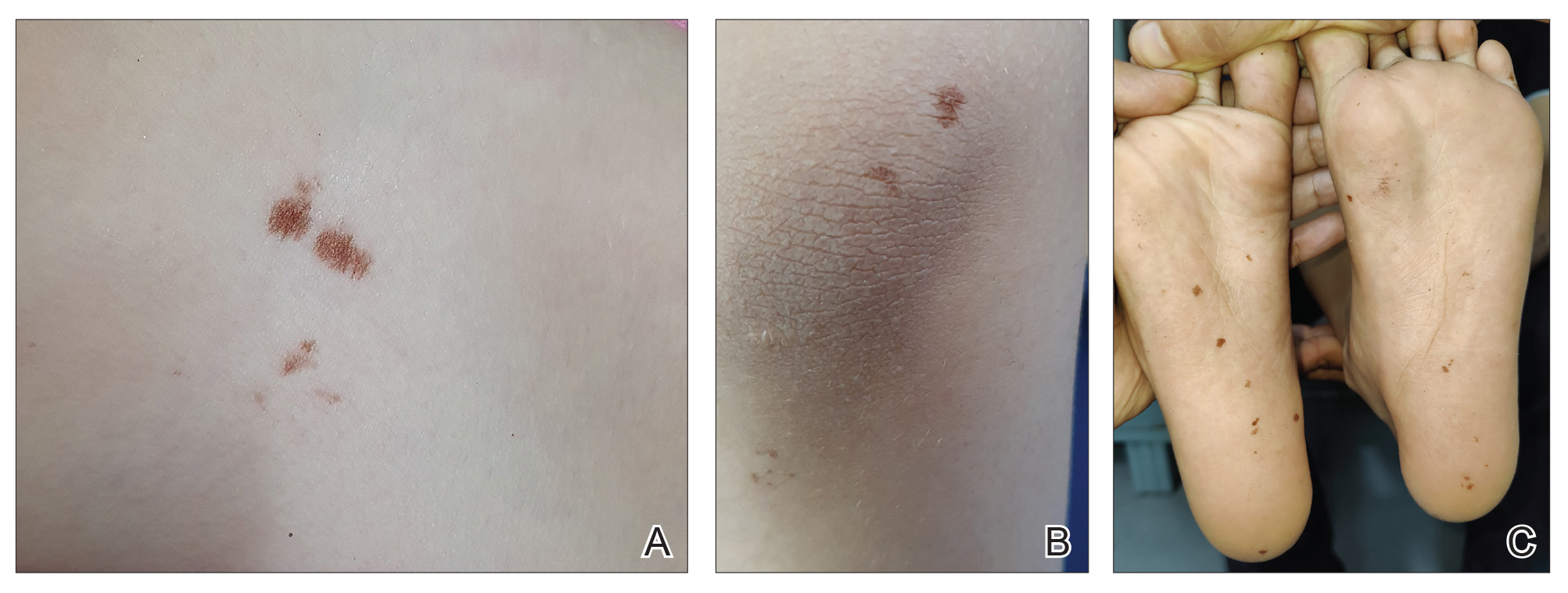

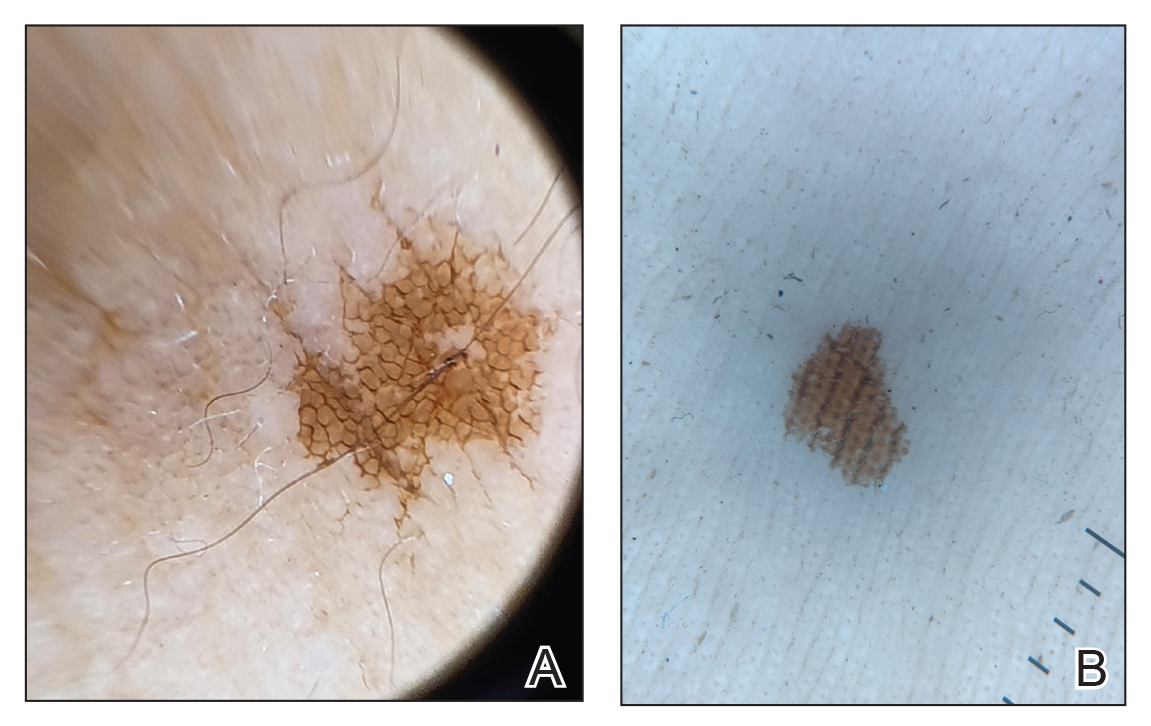

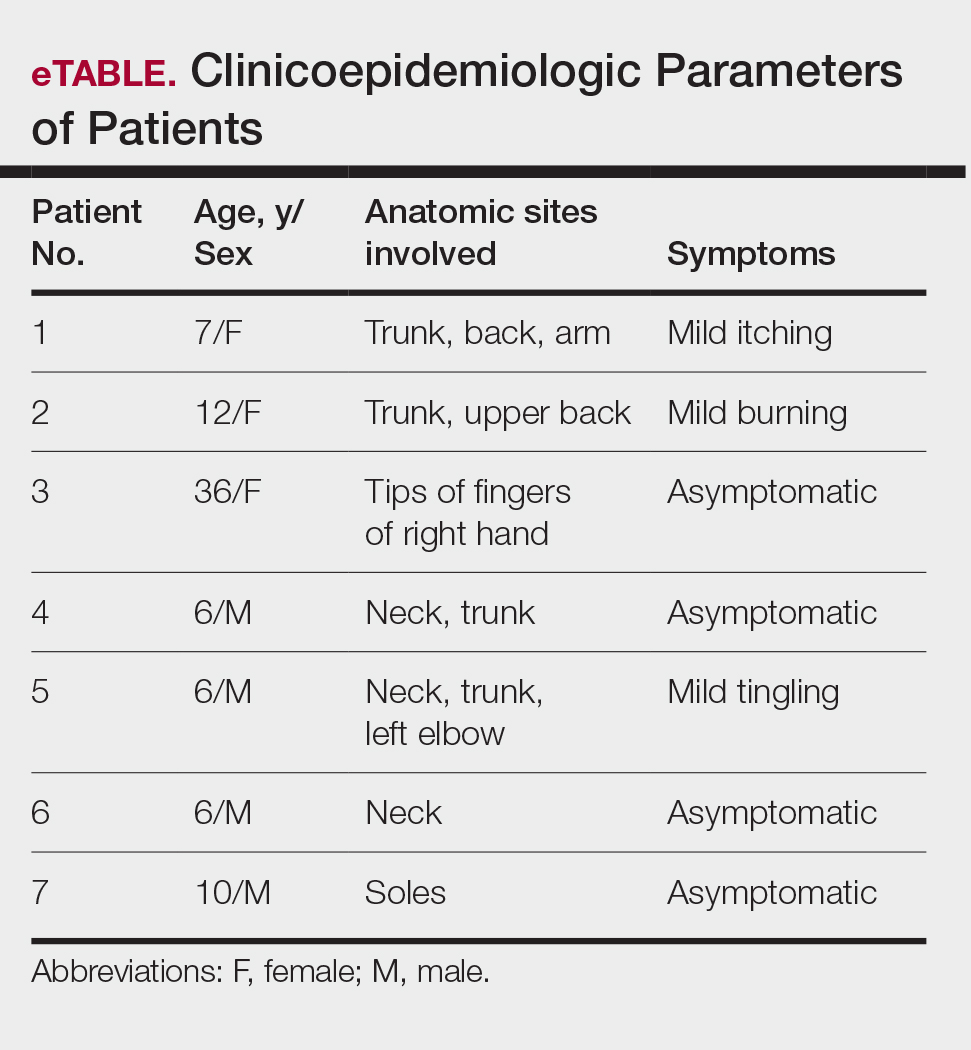

Clinical examination of the patients revealed multiple dark- to light-brown, discrete, irregularly shaped macules over the trunk, arms, and soles (eFigure 1). Dermoscopic examination of a pigmented macule showed an irregularly shaped, brownish, structureless area with accentuation of the pigment at skin creases and perieccrine pigmentation (eFigure 2). The pigmentation was unaffected by rubbing with alcohol or water. Clinicoepidemiologic parameters of the patients are summarized in the eTable.

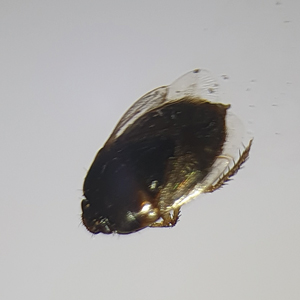

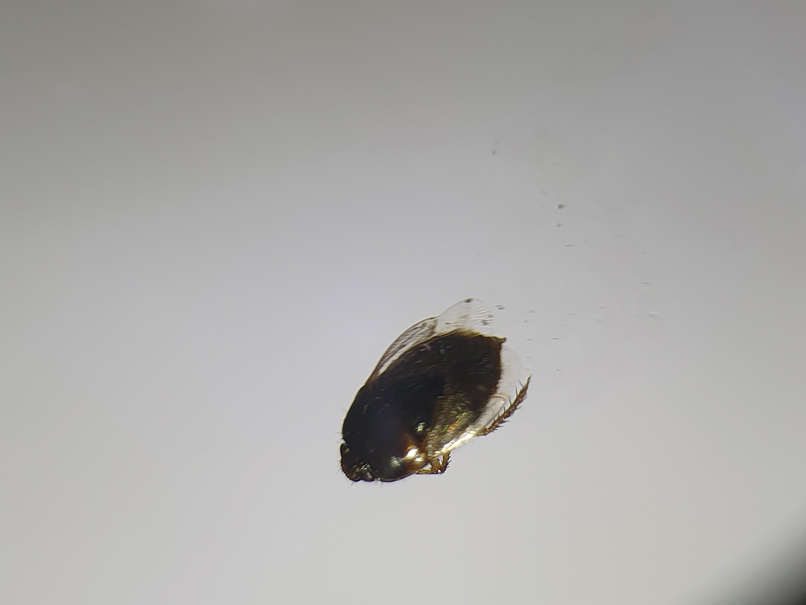

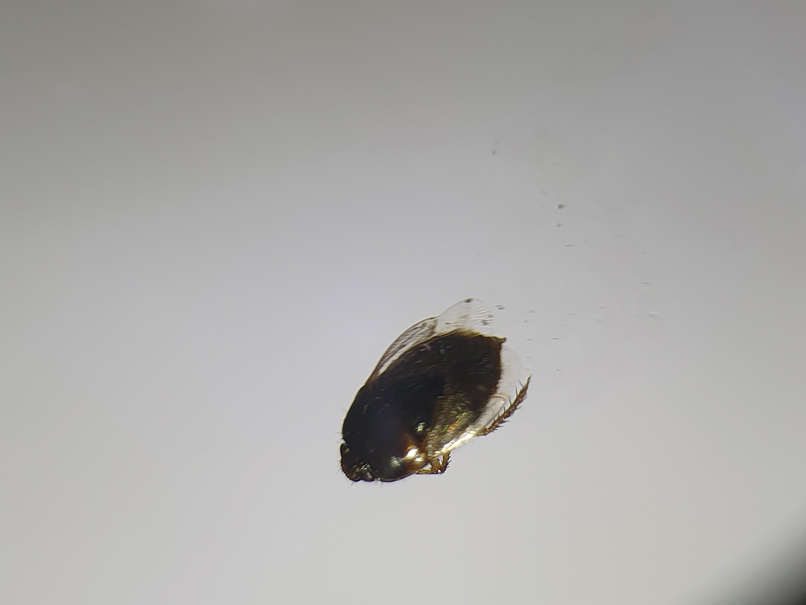

One of the children’s parents conducted a geological examination of the ground in the neighborhood park during evening hours and found tiny burrowing bugs (eFigure 3). When crushed between the fingers, these insects left a similar brownish hyperpigmentation on the skin. The parents were counseled on the nature of the eruption, and the patients were kept under observation for 2 weeks. On follow-up after 5 days, the lesions showed markedly decreased intensity of hyperpigmentation, and no new lesions were observed in any of the 7 patients.

Comment

Pentatomoidae insects generally are benign and harmless to humans. There have been isolated reports of erythematous plaques caused by Antiteuchus mixtus and Edessa maculate.7 Malhotra et al8 reported the first known series of cases with Cydnidae insect–induced hyperpigmented macules. The reported patients presented with asymptomatic, brown, hyperpigmented macules over exposed sites such as the feet, neck, and chest. All the cases occurred during the monsoon season in tropical and temperate regions of the world, and the patients were characteristically clustered in similar geographic areas. The causative insect was identified as Chilocoris assmuthi Breddin, 1904, belonging to the family Cydnidae. When it was crushed between the fingers, the skin became hyperpigmented, confirming the role of the secretions from the insect in the etiology.8

A second case was described by Sonthalia,9 who also described the dermoscopic features of hyperpigmented macules caused by burrowing bugs. The lesions showed a stuck-on, clustered appearance of ovoid and bizarre pigmented clods, globules, and granules.9 Although the lesions occur mainly over exposed sites, pigmented macules occurring over unusual sites such as the abdomen and back also have been reported in association with burrowing bugs.10 Characteristically, the lesions initially are faint and darken with time and usually fade within a week. They can be rubbed off with acetone but persist when washed with soap and water. The fleeting nature of the pigmentation also has led to the term transient pseudo-lentigines sign to describe hyperpigmentation caused by burrowing bugs.11

Soil and plants are burrowing bugs’ natural habitats, and the insects typically are seen in vegetation-rich, moist areas adjoining human dwellings (eg, parks, gardens), where clusters of cases can occur. These insects proliferate during the monsoon season in tropical and temperate areas, leading to more cases occurring during these months.

Compared to prior reports,8,9 a few of our patients had predominant trunk and neck involvement with an occasional tingling sensation or pruritus while the rest were asymptomatic. Dermoscopic features from our patients shared similar reported features of Cydnidae pigmentation.4,5 The accentuation of pigment over skin creases seen on dermoscopy was due to accumulation of Cydnidae secretion at these sites.

The differential diagnosis commonly includes idiopathic macular eruptive pigmentation, which is characterized by an asymptomatic progressive eruption of hyperpigmented macules over the trunk that persists from a few months up to 3 years. Other conditions in the differential include benign conditions such as acral benign melanocytic nevi, lentigines, pigmented purpuric dermatosis, and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, as well as malignant conditions such as acral melanoma. Dermoscopy is a helpful, easy-to-use tool in differentiating these pigmentation disorders, obviating the need for an invasive investigation such as histopathologic analysis. Simultaneous involvement in a group of people living together or visiting the same place, abrupt onset, predominant involvement of the exposed sites, characteristic clinical and dermoscopic features, self-limiting course, and timing with the monsoon season should suggest a possibility of Cydnidae dermatitis/pigmentation, which can be confirmed by finding the causative bug in the affected locality.

Management

No specific treatment is required for the pigmentation caused by Cydnidae, as it is self-resolving. The macules can, however, be removed with acetone. Patients must be counseled regarding the benign and fleeting nature of this condition, as the abrupt onset may alarm them of a systemic disease. Affected patients should be advised against walking barefoot in areas where the insects can be found. Spraying insecticides in the affected locality also helps to reduce the presence of burrowing bugs.

- Hosokawa T, Kikuchi Y, Nikoh N, et al. Polyphyly of gut symbionts in stinkbugs of the family Cydnidae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012; 78:4758-4761.

- Schwertner CF, Nardi C. Burrower bugs (Cydnidae). In: Panizzi A, Grazia J, eds. True Bugs (Heteroptera) of the Neotropics. Entomology in Focus, vol 2. Springer; 2015.

- Lis JA. Burrower bugs of the Old World: a catalogue (Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Cydnidae). Genus (Wroclaw). 1999;10:165-249.

- Hayashi N, Yamamura Y, Ôhama S, et al. Defensive substances from stink bugs of Cydnidae. Experientia. 1976;32:418-419.

- Smith RM. The defensive secretion of the bugs Lampropharadifasciata, Adrisanumeensis, and Tectocorisdiophthalmus from Fiji. NZ J Zool. 1978;5:821-822.

- Krall BS, Zilkowski BW, Kight SL, et al. Chemistry and defensive efficacy of secretion of burrowing bugs. J Chem Ecol. 1997;23:1951-1962.

- Haddad V Jr, Cardoso J, Moraes R. Skin lesions caused by stink bugs (Insecta: Heteroptera: Pentatomidae): first report of dermatological injuries in humans. Wilderness Environ Med. 2002;13:48-50.

- Malhotra AK, Lis JA, Ramam M. Cydnidae (burrowing bug) pigmentation: a novel arthropod dermatosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:232-233.

- Sonthalia S. Dermoscopy of Cydnidae pigmentation: a novel disorder of pigmentation. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2019;9:228-229.

- Poojary S, Baddireddy K. Demystifying the stinking reddish brown stains through the dermoscope: Cydnidae pigmentation. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2019;10:757-758.

- Amrani A, Das A. Cydnidae pigmentation: unusual location on the abdomen and back. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184:E125.

Cydnidae is a family of small to medium-sized shield bugs with spiny legs that commonly are known as burrowing bugs (or burrower bugs). The family Cydnidae includes more than 100 genera and approximately 600 species worldwide.1 These insects are arthropods of the order Hemiptera (suborder: Heteroptera; superfamily: Pentatomoidae) and largely are concentrated in tropical and temperate regions. Approximately 145 species have been recorded in the Neotropical Region and have been included in the subfamilies Amnestinae, Cephalocteinae, and Sehirinae, in addition to Cydnidae.2 Burrowing bugs are ovoid in shape and 2 to 20 mm in length and morphologically are well adapted for burrowing. Their life span is 100 to 300 days. Being phytophagous, they burrow to feed on plants and roots. Adult burrowing bugs have wings and can fly. They have specialized glands located in either the abdomen (nymph) or thorax (adult) that secrete odorous chemicals for self-protection.3 The secretions contain hydrocarbonates that function as repellents and danger signals, can cause paralysis in prey, and act as a chemoattractant for mates.4-6 They also cause hyperpigmentation upon contact with the skin.

In this article, we present a series of cases from the same community to demonstrate the characteristic features of hyperpigmented macules caused by exposure to burrowing bugs. Dermatologists should be aware of this entity to prevent misdiagnosis and unnecessary investigations and treatment.

Case Series

A 36-year-old woman and 6 children (age range, 6-12 years) presented with a widespread, acute, brown-pigmented, macular eruption with lesions that increased in number over a 1-week period. All 7 patients resided in the same locality and were otherwise systemically healthy. Initially, the index case, a 7-year-old girl, was referred to our tertiary care center by a dermatologist with a provisional diagnosis of idiopathic macular eruptive pigmentation. The patient’s mother recalled noticing a tiny black insect on the child's scalp that left pigment on the skin when she crushed it between her fingers. The rest of the patients presented over the next few days: 3 of the children belonged to the same household as the index case, and there was history of all 6 children playing in the neighborhood park during late evening hours. The adult patient was the parent of one of the affected children. The lesions were associated with mild itching and tingling in 3 children but were asymptomatic in the other patients.

Clinical examination of the patients revealed multiple dark- to light-brown, discrete, irregularly shaped macules over the trunk, arms, and soles (eFigure 1). Dermoscopic examination of a pigmented macule showed an irregularly shaped, brownish, structureless area with accentuation of the pigment at skin creases and perieccrine pigmentation (eFigure 2). The pigmentation was unaffected by rubbing with alcohol or water. Clinicoepidemiologic parameters of the patients are summarized in the eTable.

One of the children’s parents conducted a geological examination of the ground in the neighborhood park during evening hours and found tiny burrowing bugs (eFigure 3). When crushed between the fingers, these insects left a similar brownish hyperpigmentation on the skin. The parents were counseled on the nature of the eruption, and the patients were kept under observation for 2 weeks. On follow-up after 5 days, the lesions showed markedly decreased intensity of hyperpigmentation, and no new lesions were observed in any of the 7 patients.

Comment

Pentatomoidae insects generally are benign and harmless to humans. There have been isolated reports of erythematous plaques caused by Antiteuchus mixtus and Edessa maculate.7 Malhotra et al8 reported the first known series of cases with Cydnidae insect–induced hyperpigmented macules. The reported patients presented with asymptomatic, brown, hyperpigmented macules over exposed sites such as the feet, neck, and chest. All the cases occurred during the monsoon season in tropical and temperate regions of the world, and the patients were characteristically clustered in similar geographic areas. The causative insect was identified as Chilocoris assmuthi Breddin, 1904, belonging to the family Cydnidae. When it was crushed between the fingers, the skin became hyperpigmented, confirming the role of the secretions from the insect in the etiology.8

A second case was described by Sonthalia,9 who also described the dermoscopic features of hyperpigmented macules caused by burrowing bugs. The lesions showed a stuck-on, clustered appearance of ovoid and bizarre pigmented clods, globules, and granules.9 Although the lesions occur mainly over exposed sites, pigmented macules occurring over unusual sites such as the abdomen and back also have been reported in association with burrowing bugs.10 Characteristically, the lesions initially are faint and darken with time and usually fade within a week. They can be rubbed off with acetone but persist when washed with soap and water. The fleeting nature of the pigmentation also has led to the term transient pseudo-lentigines sign to describe hyperpigmentation caused by burrowing bugs.11

Soil and plants are burrowing bugs’ natural habitats, and the insects typically are seen in vegetation-rich, moist areas adjoining human dwellings (eg, parks, gardens), where clusters of cases can occur. These insects proliferate during the monsoon season in tropical and temperate areas, leading to more cases occurring during these months.

Compared to prior reports,8,9 a few of our patients had predominant trunk and neck involvement with an occasional tingling sensation or pruritus while the rest were asymptomatic. Dermoscopic features from our patients shared similar reported features of Cydnidae pigmentation.4,5 The accentuation of pigment over skin creases seen on dermoscopy was due to accumulation of Cydnidae secretion at these sites.

The differential diagnosis commonly includes idiopathic macular eruptive pigmentation, which is characterized by an asymptomatic progressive eruption of hyperpigmented macules over the trunk that persists from a few months up to 3 years. Other conditions in the differential include benign conditions such as acral benign melanocytic nevi, lentigines, pigmented purpuric dermatosis, and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, as well as malignant conditions such as acral melanoma. Dermoscopy is a helpful, easy-to-use tool in differentiating these pigmentation disorders, obviating the need for an invasive investigation such as histopathologic analysis. Simultaneous involvement in a group of people living together or visiting the same place, abrupt onset, predominant involvement of the exposed sites, characteristic clinical and dermoscopic features, self-limiting course, and timing with the monsoon season should suggest a possibility of Cydnidae dermatitis/pigmentation, which can be confirmed by finding the causative bug in the affected locality.

Management

No specific treatment is required for the pigmentation caused by Cydnidae, as it is self-resolving. The macules can, however, be removed with acetone. Patients must be counseled regarding the benign and fleeting nature of this condition, as the abrupt onset may alarm them of a systemic disease. Affected patients should be advised against walking barefoot in areas where the insects can be found. Spraying insecticides in the affected locality also helps to reduce the presence of burrowing bugs.

Cydnidae is a family of small to medium-sized shield bugs with spiny legs that commonly are known as burrowing bugs (or burrower bugs). The family Cydnidae includes more than 100 genera and approximately 600 species worldwide.1 These insects are arthropods of the order Hemiptera (suborder: Heteroptera; superfamily: Pentatomoidae) and largely are concentrated in tropical and temperate regions. Approximately 145 species have been recorded in the Neotropical Region and have been included in the subfamilies Amnestinae, Cephalocteinae, and Sehirinae, in addition to Cydnidae.2 Burrowing bugs are ovoid in shape and 2 to 20 mm in length and morphologically are well adapted for burrowing. Their life span is 100 to 300 days. Being phytophagous, they burrow to feed on plants and roots. Adult burrowing bugs have wings and can fly. They have specialized glands located in either the abdomen (nymph) or thorax (adult) that secrete odorous chemicals for self-protection.3 The secretions contain hydrocarbonates that function as repellents and danger signals, can cause paralysis in prey, and act as a chemoattractant for mates.4-6 They also cause hyperpigmentation upon contact with the skin.

In this article, we present a series of cases from the same community to demonstrate the characteristic features of hyperpigmented macules caused by exposure to burrowing bugs. Dermatologists should be aware of this entity to prevent misdiagnosis and unnecessary investigations and treatment.

Case Series

A 36-year-old woman and 6 children (age range, 6-12 years) presented with a widespread, acute, brown-pigmented, macular eruption with lesions that increased in number over a 1-week period. All 7 patients resided in the same locality and were otherwise systemically healthy. Initially, the index case, a 7-year-old girl, was referred to our tertiary care center by a dermatologist with a provisional diagnosis of idiopathic macular eruptive pigmentation. The patient’s mother recalled noticing a tiny black insect on the child's scalp that left pigment on the skin when she crushed it between her fingers. The rest of the patients presented over the next few days: 3 of the children belonged to the same household as the index case, and there was history of all 6 children playing in the neighborhood park during late evening hours. The adult patient was the parent of one of the affected children. The lesions were associated with mild itching and tingling in 3 children but were asymptomatic in the other patients.

Clinical examination of the patients revealed multiple dark- to light-brown, discrete, irregularly shaped macules over the trunk, arms, and soles (eFigure 1). Dermoscopic examination of a pigmented macule showed an irregularly shaped, brownish, structureless area with accentuation of the pigment at skin creases and perieccrine pigmentation (eFigure 2). The pigmentation was unaffected by rubbing with alcohol or water. Clinicoepidemiologic parameters of the patients are summarized in the eTable.

One of the children’s parents conducted a geological examination of the ground in the neighborhood park during evening hours and found tiny burrowing bugs (eFigure 3). When crushed between the fingers, these insects left a similar brownish hyperpigmentation on the skin. The parents were counseled on the nature of the eruption, and the patients were kept under observation for 2 weeks. On follow-up after 5 days, the lesions showed markedly decreased intensity of hyperpigmentation, and no new lesions were observed in any of the 7 patients.

Comment

Pentatomoidae insects generally are benign and harmless to humans. There have been isolated reports of erythematous plaques caused by Antiteuchus mixtus and Edessa maculate.7 Malhotra et al8 reported the first known series of cases with Cydnidae insect–induced hyperpigmented macules. The reported patients presented with asymptomatic, brown, hyperpigmented macules over exposed sites such as the feet, neck, and chest. All the cases occurred during the monsoon season in tropical and temperate regions of the world, and the patients were characteristically clustered in similar geographic areas. The causative insect was identified as Chilocoris assmuthi Breddin, 1904, belonging to the family Cydnidae. When it was crushed between the fingers, the skin became hyperpigmented, confirming the role of the secretions from the insect in the etiology.8

A second case was described by Sonthalia,9 who also described the dermoscopic features of hyperpigmented macules caused by burrowing bugs. The lesions showed a stuck-on, clustered appearance of ovoid and bizarre pigmented clods, globules, and granules.9 Although the lesions occur mainly over exposed sites, pigmented macules occurring over unusual sites such as the abdomen and back also have been reported in association with burrowing bugs.10 Characteristically, the lesions initially are faint and darken with time and usually fade within a week. They can be rubbed off with acetone but persist when washed with soap and water. The fleeting nature of the pigmentation also has led to the term transient pseudo-lentigines sign to describe hyperpigmentation caused by burrowing bugs.11

Soil and plants are burrowing bugs’ natural habitats, and the insects typically are seen in vegetation-rich, moist areas adjoining human dwellings (eg, parks, gardens), where clusters of cases can occur. These insects proliferate during the monsoon season in tropical and temperate areas, leading to more cases occurring during these months.

Compared to prior reports,8,9 a few of our patients had predominant trunk and neck involvement with an occasional tingling sensation or pruritus while the rest were asymptomatic. Dermoscopic features from our patients shared similar reported features of Cydnidae pigmentation.4,5 The accentuation of pigment over skin creases seen on dermoscopy was due to accumulation of Cydnidae secretion at these sites.

The differential diagnosis commonly includes idiopathic macular eruptive pigmentation, which is characterized by an asymptomatic progressive eruption of hyperpigmented macules over the trunk that persists from a few months up to 3 years. Other conditions in the differential include benign conditions such as acral benign melanocytic nevi, lentigines, pigmented purpuric dermatosis, and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, as well as malignant conditions such as acral melanoma. Dermoscopy is a helpful, easy-to-use tool in differentiating these pigmentation disorders, obviating the need for an invasive investigation such as histopathologic analysis. Simultaneous involvement in a group of people living together or visiting the same place, abrupt onset, predominant involvement of the exposed sites, characteristic clinical and dermoscopic features, self-limiting course, and timing with the monsoon season should suggest a possibility of Cydnidae dermatitis/pigmentation, which can be confirmed by finding the causative bug in the affected locality.

Management

No specific treatment is required for the pigmentation caused by Cydnidae, as it is self-resolving. The macules can, however, be removed with acetone. Patients must be counseled regarding the benign and fleeting nature of this condition, as the abrupt onset may alarm them of a systemic disease. Affected patients should be advised against walking barefoot in areas where the insects can be found. Spraying insecticides in the affected locality also helps to reduce the presence of burrowing bugs.

- Hosokawa T, Kikuchi Y, Nikoh N, et al. Polyphyly of gut symbionts in stinkbugs of the family Cydnidae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012; 78:4758-4761.

- Schwertner CF, Nardi C. Burrower bugs (Cydnidae). In: Panizzi A, Grazia J, eds. True Bugs (Heteroptera) of the Neotropics. Entomology in Focus, vol 2. Springer; 2015.

- Lis JA. Burrower bugs of the Old World: a catalogue (Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Cydnidae). Genus (Wroclaw). 1999;10:165-249.

- Hayashi N, Yamamura Y, Ôhama S, et al. Defensive substances from stink bugs of Cydnidae. Experientia. 1976;32:418-419.

- Smith RM. The defensive secretion of the bugs Lampropharadifasciata, Adrisanumeensis, and Tectocorisdiophthalmus from Fiji. NZ J Zool. 1978;5:821-822.

- Krall BS, Zilkowski BW, Kight SL, et al. Chemistry and defensive efficacy of secretion of burrowing bugs. J Chem Ecol. 1997;23:1951-1962.

- Haddad V Jr, Cardoso J, Moraes R. Skin lesions caused by stink bugs (Insecta: Heteroptera: Pentatomidae): first report of dermatological injuries in humans. Wilderness Environ Med. 2002;13:48-50.

- Malhotra AK, Lis JA, Ramam M. Cydnidae (burrowing bug) pigmentation: a novel arthropod dermatosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:232-233.

- Sonthalia S. Dermoscopy of Cydnidae pigmentation: a novel disorder of pigmentation. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2019;9:228-229.

- Poojary S, Baddireddy K. Demystifying the stinking reddish brown stains through the dermoscope: Cydnidae pigmentation. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2019;10:757-758.

- Amrani A, Das A. Cydnidae pigmentation: unusual location on the abdomen and back. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184:E125.

- Hosokawa T, Kikuchi Y, Nikoh N, et al. Polyphyly of gut symbionts in stinkbugs of the family Cydnidae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012; 78:4758-4761.

- Schwertner CF, Nardi C. Burrower bugs (Cydnidae). In: Panizzi A, Grazia J, eds. True Bugs (Heteroptera) of the Neotropics. Entomology in Focus, vol 2. Springer; 2015.

- Lis JA. Burrower bugs of the Old World: a catalogue (Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Cydnidae). Genus (Wroclaw). 1999;10:165-249.

- Hayashi N, Yamamura Y, Ôhama S, et al. Defensive substances from stink bugs of Cydnidae. Experientia. 1976;32:418-419.

- Smith RM. The defensive secretion of the bugs Lampropharadifasciata, Adrisanumeensis, and Tectocorisdiophthalmus from Fiji. NZ J Zool. 1978;5:821-822.

- Krall BS, Zilkowski BW, Kight SL, et al. Chemistry and defensive efficacy of secretion of burrowing bugs. J Chem Ecol. 1997;23:1951-1962.

- Haddad V Jr, Cardoso J, Moraes R. Skin lesions caused by stink bugs (Insecta: Heteroptera: Pentatomidae): first report of dermatological injuries in humans. Wilderness Environ Med. 2002;13:48-50.

- Malhotra AK, Lis JA, Ramam M. Cydnidae (burrowing bug) pigmentation: a novel arthropod dermatosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:232-233.

- Sonthalia S. Dermoscopy of Cydnidae pigmentation: a novel disorder of pigmentation. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2019;9:228-229.

- Poojary S, Baddireddy K. Demystifying the stinking reddish brown stains through the dermoscope: Cydnidae pigmentation. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2019;10:757-758.

- Amrani A, Das A. Cydnidae pigmentation: unusual location on the abdomen and back. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184:E125.

Hyperpigmented Macules Caused by Burrowing Bugs (Cydnidae) May Mimic More Serious Conditions

Hyperpigmented Macules Caused by Burrowing Bugs (Cydnidae) May Mimic More Serious Conditions

Practice Points

- Burrowing bugs (Cydnidae) are phytophagous and burrow to feed on plants and roots. They are more numerous during the monsoon season in tropical and temperate regions.

- Secretions from burrowing bugs cause asymptomatic, hyperpigmented, irregularly shaped macules suggestive of an exogenous cause that commonly affect clusters of patients from the same geographic locality.

- The lesions are self-limiting and must be differentiated from close mimickers to ensure adequate and appropriate patient counseling.

Pigmented Papules on the Face, Neck, and Chest

The Diagnosis: Syringoma

Syringomas are benign adnexal tumors with distinct histopathologic features, including the characteristic comma- or tadpole-shaped tail comprised of dilated cystic eccrine ducts. Clinically, syringomas typically present predominantly in the periorbital region in adolescent girls. They may present as solitary or multiple lesions, and sites such as the genital area, palms, scalp, and chest rarely can be involved.1 Eruptive syringoma is a clinical subtype of syringoma that is seen on the face, neck, chest, and axillae that predominantly occurs in females with skin of color in countries such as Asia and Africa before or during puberty.2,3 Lesions appear as small, flesh-colored or slightly pigmented, flat-topped papules.3 The condition can be cosmetically disfiguring and difficult to treat, especially in patients with darker skin.

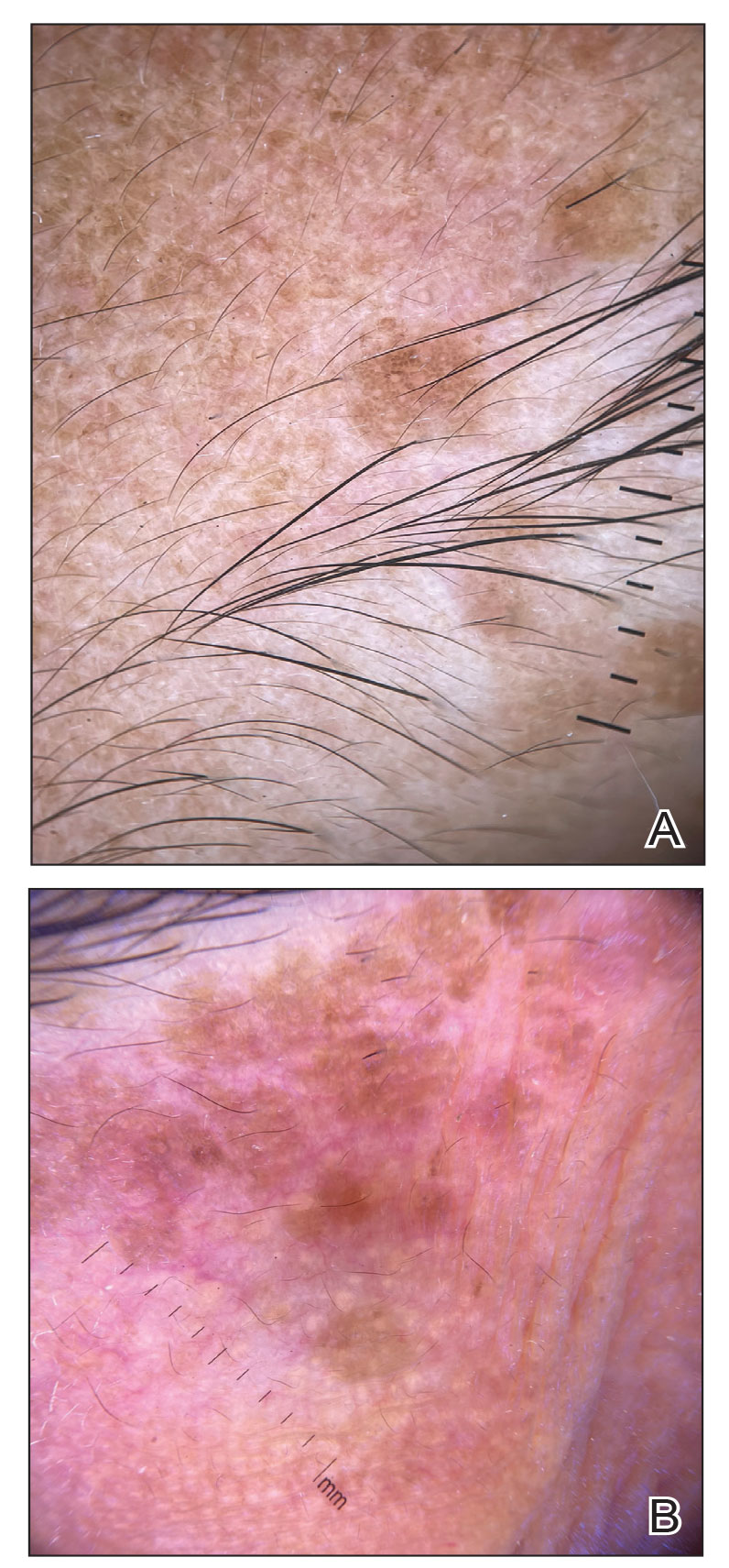

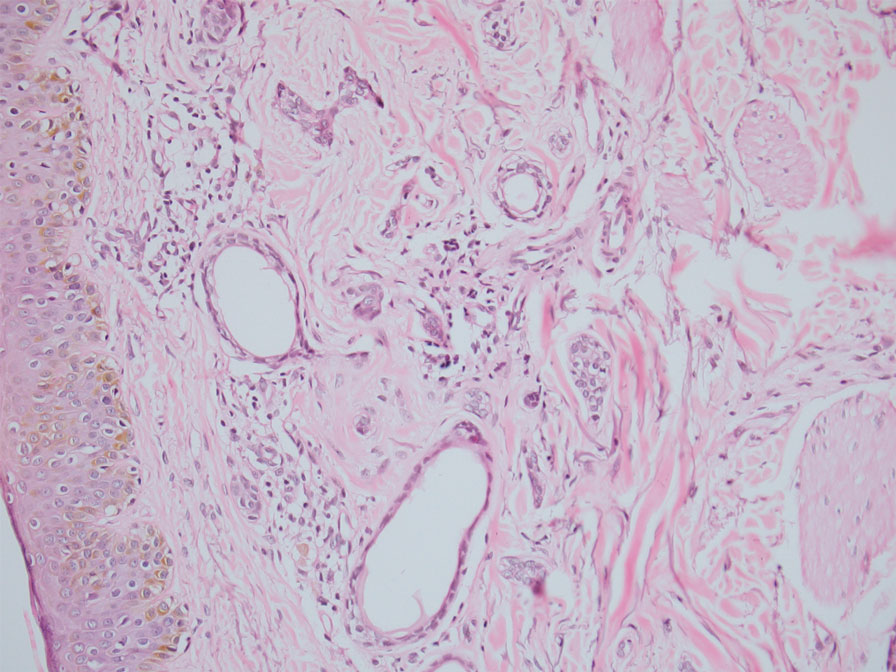

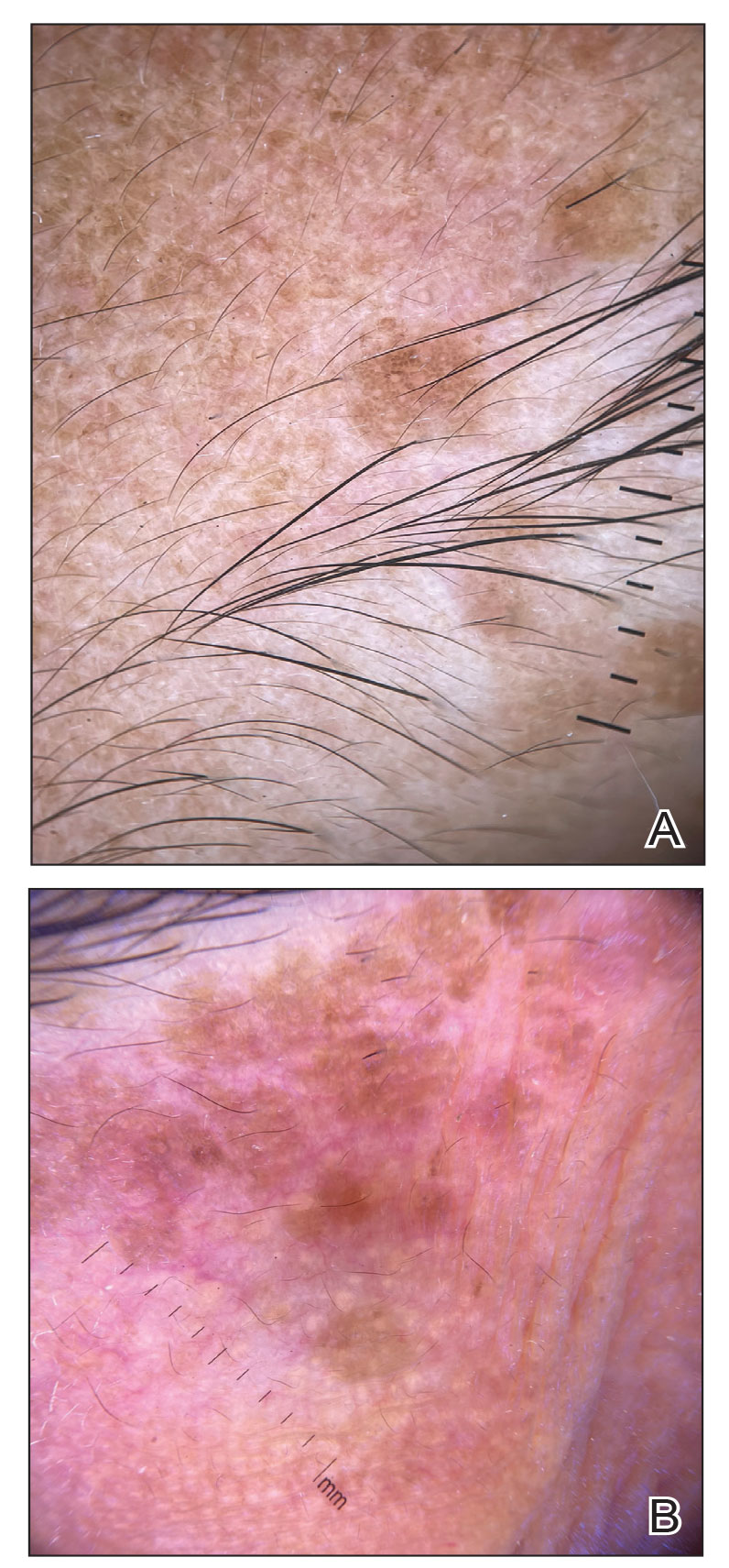

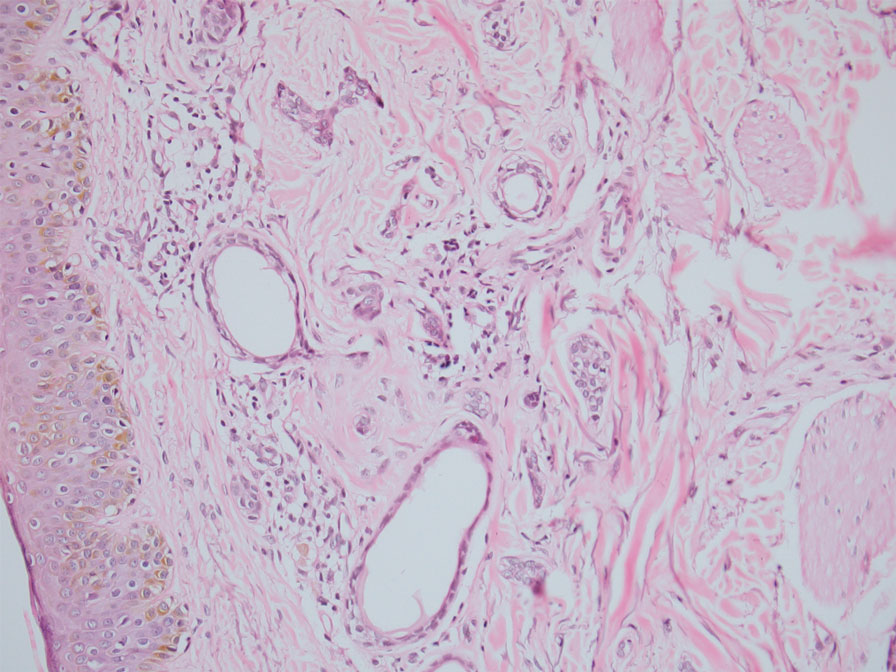

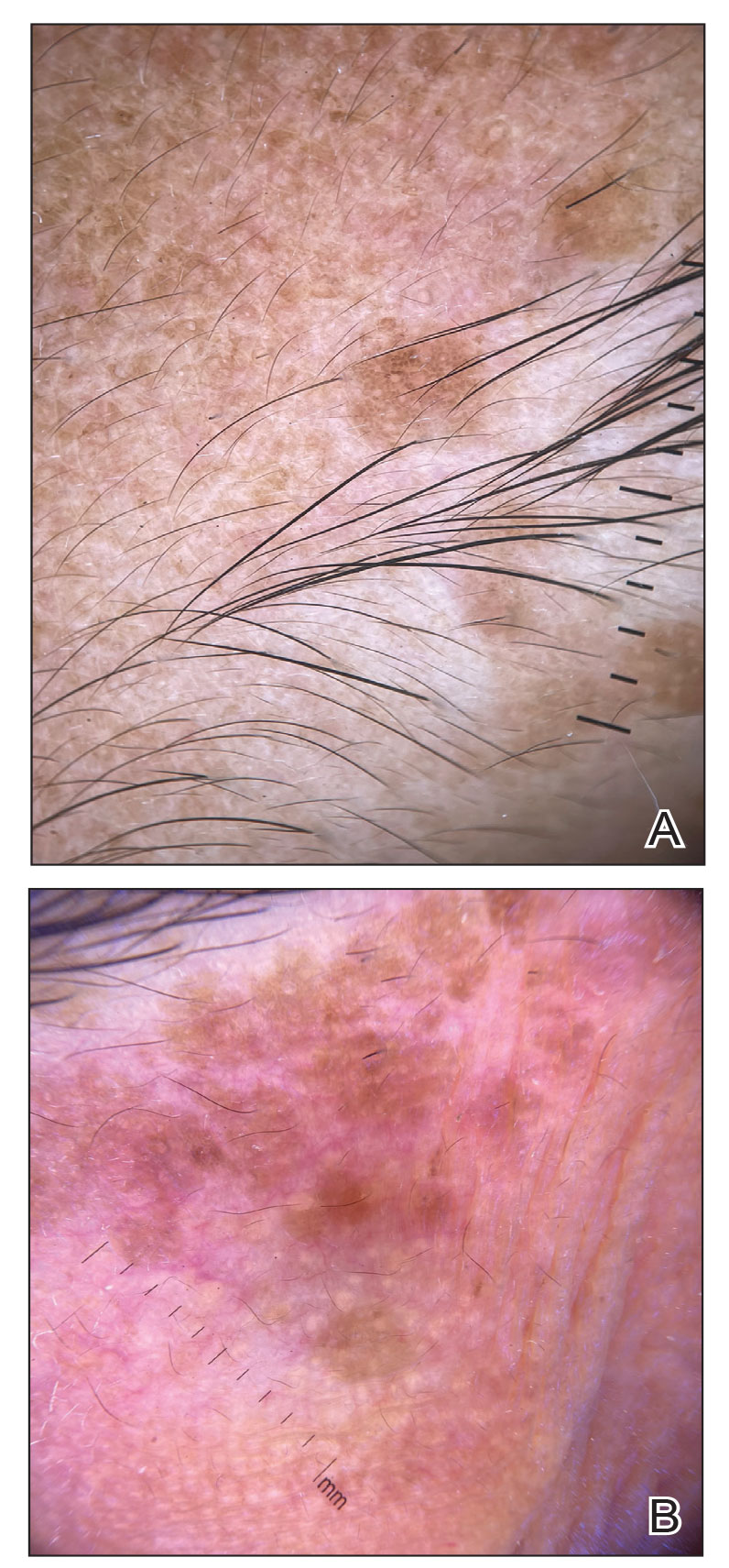

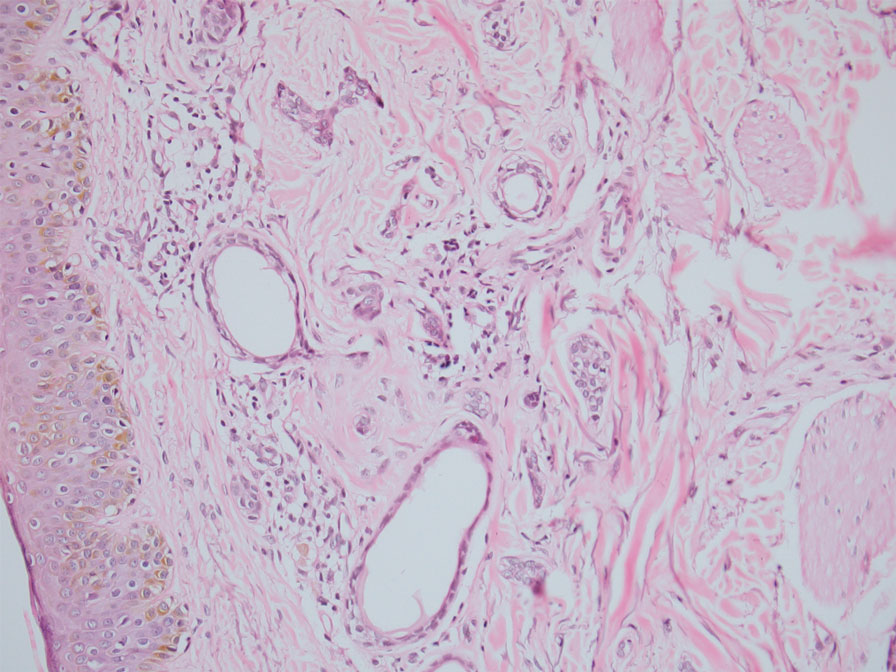

In our patient, dermoscopic evaluation revealed reticular light brown lines, structureless light brown areas, clustered brown dots, globules, and reticular vessels on a faint background (Figure 1A). Glittering yellow-whitish round structures over a fading pink-brown background also were seen at some sites (Figure 1B). Histologic examination of a neck lesion revealed an epidermis with focal acanthosis; the upper dermis had tumor islands and ducts with cells with round to vesicular nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm. A well-circumscribed tumor in the dermis composed of tubules of varying sizes lined by cuboidal cells was seen, consistent with syringoma (Figure 2).

Dermoscopic features of syringomas have not been widely studied. Hayashi et al4 reported the dermoscopic features of unilateral linear syringomas as a delicate and faint reticular pigmentation network and multiple hypopigmented areas. Sakiyama et al5 also defined an incomplete pigment network with faint erythema in 2 eruptive syringoma cases.

Treatment of this condition is for cosmetic reasons only, and there are no reports of long-term morbidity associated with the disease.6,7 Multiple therapeutic options are available but are associated with complications such as hyperpigmentation and sclerosis in patients with skin of color due to the dermal location of these syringomas. Management of syringomas includes topical and surgical methods, including topical retinoids such as tretinoin and atropine solution 1%; surgical methods include dermabrasion, excision, cryotherapy, electrocautery, electrofulguration, laser therapy, and chemical cautery. However, there is a substantial risk for recurrence with these treatment options. In a case series of 5 patients with periorbital syringomas, treatment using radiofrequency and a CO2 laser was performed with favorable outcomes, highlighting the use of combination therapies for treatment.8 Seo et al9 reported a retrospective case series of 92 patients with periorbital syringomas in which they treated one group with CO2 laser and the other with botulinum toxin A injection; CO2 laser combined with botulinum toxin A showed a greater effect than laser treatment alone. The differential diagnosis includes pigmented plane warts, sebaceous hyperplasia, eruptive xanthomas, and hidrocystomas. Pigmented plane warts characteristically present as flat-topped papules with small hemorrhagic dots or tiny pinpoint vessels on dermoscopy. In sebaceous hyperplasia, yellowish umbilicated papular lesions are seen with crown vessels on dermoscopy. Eruptive xanthomas usually are erythematous to yellow, dome-shaped papules that appear mainly over the extensor aspects of the extremities. Hidrocystoma presents as a solitary translucent larger syringomalike lesion commonly seen in the periorbital region and/or on the cheeks.

We report a case of widespread syringomas with multiple close mimickers such as pigmented plane warts; however, dermoscopy of the lesions helped to arrive at the diagnosis. Dermatologists should be aware of this condition and its benign nature to ensure correct diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

- Williams K, Shinkai K. Evaluation and management of the patient with multiple syringomas: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1234.e9-1240.e9.

- Tsunemi Y, Ihn H, Saeki H, et al. Generalized eruptive syringoma. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:492-493.

- Singh S, Tewari R, Gupta S. An unusual case of generalised eruptive syringoma in an adult male. Med J Armed Forces India. 2014;70:389-391.

- Hayashi Y, Tanaka M, Nakajima S, et al. Unilateral linear syringoma in a Japanese female: dermoscopic differentiation from lichen lanus linearis. Dermatol Rep. 2011;3:E42.

- Sakiyama M, Maeda M, Fujimoto N, et al. Eruptive syringoma localized in intertriginous areas. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2014;12:72-73.

- Wang JI, Roenigk HH Jr. Treatment of multiple facial syringomas with the carbon dioxide (CO2) laser. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:136-139.

- Tsunemi Y, Ihn H, Saeki H, et al. Generalized eruptive syringoma. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:492-493.

- Hasson A, Farias MM, Nicklas C, et al. Periorbital syringoma treated with radiofrequency and carbon dioxide (CO2) laser in 5 patients. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:879-880.

- Seo HM, Choi JY, Min J, et al. Carbon dioxide laser combined with botulinum toxin A for patients with periorbital syringomas [published online March 31, 2016]. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2016;18:149-153.

The Diagnosis: Syringoma

Syringomas are benign adnexal tumors with distinct histopathologic features, including the characteristic comma- or tadpole-shaped tail comprised of dilated cystic eccrine ducts. Clinically, syringomas typically present predominantly in the periorbital region in adolescent girls. They may present as solitary or multiple lesions, and sites such as the genital area, palms, scalp, and chest rarely can be involved.1 Eruptive syringoma is a clinical subtype of syringoma that is seen on the face, neck, chest, and axillae that predominantly occurs in females with skin of color in countries such as Asia and Africa before or during puberty.2,3 Lesions appear as small, flesh-colored or slightly pigmented, flat-topped papules.3 The condition can be cosmetically disfiguring and difficult to treat, especially in patients with darker skin.

In our patient, dermoscopic evaluation revealed reticular light brown lines, structureless light brown areas, clustered brown dots, globules, and reticular vessels on a faint background (Figure 1A). Glittering yellow-whitish round structures over a fading pink-brown background also were seen at some sites (Figure 1B). Histologic examination of a neck lesion revealed an epidermis with focal acanthosis; the upper dermis had tumor islands and ducts with cells with round to vesicular nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm. A well-circumscribed tumor in the dermis composed of tubules of varying sizes lined by cuboidal cells was seen, consistent with syringoma (Figure 2).

Dermoscopic features of syringomas have not been widely studied. Hayashi et al4 reported the dermoscopic features of unilateral linear syringomas as a delicate and faint reticular pigmentation network and multiple hypopigmented areas. Sakiyama et al5 also defined an incomplete pigment network with faint erythema in 2 eruptive syringoma cases.

Treatment of this condition is for cosmetic reasons only, and there are no reports of long-term morbidity associated with the disease.6,7 Multiple therapeutic options are available but are associated with complications such as hyperpigmentation and sclerosis in patients with skin of color due to the dermal location of these syringomas. Management of syringomas includes topical and surgical methods, including topical retinoids such as tretinoin and atropine solution 1%; surgical methods include dermabrasion, excision, cryotherapy, electrocautery, electrofulguration, laser therapy, and chemical cautery. However, there is a substantial risk for recurrence with these treatment options. In a case series of 5 patients with periorbital syringomas, treatment using radiofrequency and a CO2 laser was performed with favorable outcomes, highlighting the use of combination therapies for treatment.8 Seo et al9 reported a retrospective case series of 92 patients with periorbital syringomas in which they treated one group with CO2 laser and the other with botulinum toxin A injection; CO2 laser combined with botulinum toxin A showed a greater effect than laser treatment alone. The differential diagnosis includes pigmented plane warts, sebaceous hyperplasia, eruptive xanthomas, and hidrocystomas. Pigmented plane warts characteristically present as flat-topped papules with small hemorrhagic dots or tiny pinpoint vessels on dermoscopy. In sebaceous hyperplasia, yellowish umbilicated papular lesions are seen with crown vessels on dermoscopy. Eruptive xanthomas usually are erythematous to yellow, dome-shaped papules that appear mainly over the extensor aspects of the extremities. Hidrocystoma presents as a solitary translucent larger syringomalike lesion commonly seen in the periorbital region and/or on the cheeks.

We report a case of widespread syringomas with multiple close mimickers such as pigmented plane warts; however, dermoscopy of the lesions helped to arrive at the diagnosis. Dermatologists should be aware of this condition and its benign nature to ensure correct diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

The Diagnosis: Syringoma

Syringomas are benign adnexal tumors with distinct histopathologic features, including the characteristic comma- or tadpole-shaped tail comprised of dilated cystic eccrine ducts. Clinically, syringomas typically present predominantly in the periorbital region in adolescent girls. They may present as solitary or multiple lesions, and sites such as the genital area, palms, scalp, and chest rarely can be involved.1 Eruptive syringoma is a clinical subtype of syringoma that is seen on the face, neck, chest, and axillae that predominantly occurs in females with skin of color in countries such as Asia and Africa before or during puberty.2,3 Lesions appear as small, flesh-colored or slightly pigmented, flat-topped papules.3 The condition can be cosmetically disfiguring and difficult to treat, especially in patients with darker skin.

In our patient, dermoscopic evaluation revealed reticular light brown lines, structureless light brown areas, clustered brown dots, globules, and reticular vessels on a faint background (Figure 1A). Glittering yellow-whitish round structures over a fading pink-brown background also were seen at some sites (Figure 1B). Histologic examination of a neck lesion revealed an epidermis with focal acanthosis; the upper dermis had tumor islands and ducts with cells with round to vesicular nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm. A well-circumscribed tumor in the dermis composed of tubules of varying sizes lined by cuboidal cells was seen, consistent with syringoma (Figure 2).

Dermoscopic features of syringomas have not been widely studied. Hayashi et al4 reported the dermoscopic features of unilateral linear syringomas as a delicate and faint reticular pigmentation network and multiple hypopigmented areas. Sakiyama et al5 also defined an incomplete pigment network with faint erythema in 2 eruptive syringoma cases.

Treatment of this condition is for cosmetic reasons only, and there are no reports of long-term morbidity associated with the disease.6,7 Multiple therapeutic options are available but are associated with complications such as hyperpigmentation and sclerosis in patients with skin of color due to the dermal location of these syringomas. Management of syringomas includes topical and surgical methods, including topical retinoids such as tretinoin and atropine solution 1%; surgical methods include dermabrasion, excision, cryotherapy, electrocautery, electrofulguration, laser therapy, and chemical cautery. However, there is a substantial risk for recurrence with these treatment options. In a case series of 5 patients with periorbital syringomas, treatment using radiofrequency and a CO2 laser was performed with favorable outcomes, highlighting the use of combination therapies for treatment.8 Seo et al9 reported a retrospective case series of 92 patients with periorbital syringomas in which they treated one group with CO2 laser and the other with botulinum toxin A injection; CO2 laser combined with botulinum toxin A showed a greater effect than laser treatment alone. The differential diagnosis includes pigmented plane warts, sebaceous hyperplasia, eruptive xanthomas, and hidrocystomas. Pigmented plane warts characteristically present as flat-topped papules with small hemorrhagic dots or tiny pinpoint vessels on dermoscopy. In sebaceous hyperplasia, yellowish umbilicated papular lesions are seen with crown vessels on dermoscopy. Eruptive xanthomas usually are erythematous to yellow, dome-shaped papules that appear mainly over the extensor aspects of the extremities. Hidrocystoma presents as a solitary translucent larger syringomalike lesion commonly seen in the periorbital region and/or on the cheeks.

We report a case of widespread syringomas with multiple close mimickers such as pigmented plane warts; however, dermoscopy of the lesions helped to arrive at the diagnosis. Dermatologists should be aware of this condition and its benign nature to ensure correct diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

- Williams K, Shinkai K. Evaluation and management of the patient with multiple syringomas: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1234.e9-1240.e9.

- Tsunemi Y, Ihn H, Saeki H, et al. Generalized eruptive syringoma. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:492-493.

- Singh S, Tewari R, Gupta S. An unusual case of generalised eruptive syringoma in an adult male. Med J Armed Forces India. 2014;70:389-391.

- Hayashi Y, Tanaka M, Nakajima S, et al. Unilateral linear syringoma in a Japanese female: dermoscopic differentiation from lichen lanus linearis. Dermatol Rep. 2011;3:E42.

- Sakiyama M, Maeda M, Fujimoto N, et al. Eruptive syringoma localized in intertriginous areas. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2014;12:72-73.

- Wang JI, Roenigk HH Jr. Treatment of multiple facial syringomas with the carbon dioxide (CO2) laser. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:136-139.

- Tsunemi Y, Ihn H, Saeki H, et al. Generalized eruptive syringoma. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:492-493.

- Hasson A, Farias MM, Nicklas C, et al. Periorbital syringoma treated with radiofrequency and carbon dioxide (CO2) laser in 5 patients. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:879-880.

- Seo HM, Choi JY, Min J, et al. Carbon dioxide laser combined with botulinum toxin A for patients with periorbital syringomas [published online March 31, 2016]. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2016;18:149-153.

- Williams K, Shinkai K. Evaluation and management of the patient with multiple syringomas: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1234.e9-1240.e9.

- Tsunemi Y, Ihn H, Saeki H, et al. Generalized eruptive syringoma. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:492-493.

- Singh S, Tewari R, Gupta S. An unusual case of generalised eruptive syringoma in an adult male. Med J Armed Forces India. 2014;70:389-391.

- Hayashi Y, Tanaka M, Nakajima S, et al. Unilateral linear syringoma in a Japanese female: dermoscopic differentiation from lichen lanus linearis. Dermatol Rep. 2011;3:E42.

- Sakiyama M, Maeda M, Fujimoto N, et al. Eruptive syringoma localized in intertriginous areas. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2014;12:72-73.

- Wang JI, Roenigk HH Jr. Treatment of multiple facial syringomas with the carbon dioxide (CO2) laser. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:136-139.

- Tsunemi Y, Ihn H, Saeki H, et al. Generalized eruptive syringoma. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:492-493.

- Hasson A, Farias MM, Nicklas C, et al. Periorbital syringoma treated with radiofrequency and carbon dioxide (CO2) laser in 5 patients. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:879-880.

- Seo HM, Choi JY, Min J, et al. Carbon dioxide laser combined with botulinum toxin A for patients with periorbital syringomas [published online March 31, 2016]. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2016;18:149-153.

A 46-year-old woman presented with multiple asymptomatic, flesh-colored, hyperpigmented papules on the face of 5 to 6 months’ duration that were progressively increasing in number. The lesions first appeared near the eyebrows and cheeks (top) and subsequently spread to involve the neck. She had no notable medical history. Cutaneous examination revealed multiple tan to brown papules over the periorbital, malar, and neck regions ranging in size from 1 to 5 mm. The lesions over the periorbital region were arranged in a linear pattern (bottom). Similar lesions also were present on the chest and arms. No other sites were involved, and systemic examination was normal.