User login

Postoperative delirium in a 64-year-old woman

A 64-year-old woman undergoes elective T10-S1 nerve decompression with fusion for chronic idiopathic scoliosis. Soon afterward, she develops acute urinary retention attributed to an Escherichia coli urinary tract infection and narcotic medications. She is treated with antibiotics, an indwelling catheter is inserted, and her symptoms resolve. She is transferred to the inpatient physical rehabilitation unit.

On postoperative day 9, she develops an acute change in mental status, suddenly becoming extremely anxious and falsely believing she has a “terminal illness.” A psychiatrist suggests that these symptoms are a manifestation of delirium, given the patient’s recent surgery and exposure to benzodiazepine and narcotic medications. On postoperative day 10, she is awake but is now mute and uncooperative. An internist is consulted for an evaluation for encephalopathy and delirium.

MEDICAL HISTORY

Her medical history, obtained by chart review and interviewing her husband, includes well-controlled bipolar disorder over the last 4 years, with no episodes of frank psychosis or mania. She had a “bout of delirium” 4 years earlier attributed to a catastrophic life event, but the symptoms resolved after adjustment of her anxiolytic and mood-stabilizing drugs. She also has well-controlled hypertension, hypothyroidism, and gastroesophageal reflux. Her only surgery was her recent elective procedure.

She has a family history of dementia (Pick disease in her mother).

She is married, lives with her husband, and has an adult son. She is employed as a media specialist and also teaches English as a second language. Before this hospital admission, she was described as happy and content, though her primary psychiatrist had noted intermittent anxiety. Her husband does not suspect illicit drug use and denies significant alcohol or tobacco abuse.

A thorough review of systems is not possible, given her encephalopathy. But before her acute decline, she had complained of “choking on blood” and a subjective inability to swallow.

Her home medications include dextroamphetamine extended-release, alprazolam as needed for sleep, venlafaxine extended-release, lamotrigine, lisinopril, propranolol, amlodipine, atorvastatin, levothyroxine, omeprazole, iron, and vitamin B12. At the time of the evaluation, she is on her home medications with the addition of olanzapine, vitamin D, polyethylene glycol, and an intravenous infusion of dextrose 5% with 0.45% saline at a rate of 100 mL/hour. She has allergies to latex, penicillin, peanuts, and shellfish.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

On physical examination, the patient seems healthy and appears normal for her stated age. She is wearing a spinal brace and is in no apparent distress. She is afebrile, pulse 104 beats per minute, respirations 16 breaths per minute and unlabored, and oxygen saturation good on room air. The skin is normal. No thyromegaly, bruits, or lymphadenopathy is noted. Cardiovascular, respiratory, and abdominal examinations, though limited by the spinal brace, are unremarkable. She has no evidence of peripheral edema or vascular insufficiency. Muscle bulk and tone are adequate and symmetric.

She is awake and alert and able to follow simple commands with some prompting. She does not initiate movements spontaneously. She makes some eye contact but does not track or acknowledge the interviewer consistently and does not respond verbally to questions. Her sclera are nonicteric, the pupils are equally round and reactive to light, and the external ocular muscles are intact. There is no facial asymmetry, and the tongue protrudes at midline. She blinks appropriately to threat bilaterally. Strength is at least 3/5 in the upper extremities and 2/5 in the lower extremities, though the examination is limited by lack of patient cooperation. She shows minimal grimace on noxious stimulation but does not withdraw extremities. Reflexes are present and mildly depressed symmetrically. Plantar reflexes are downgoing bilaterally.

INITIAL LABORATORY EVALUATION

On initial laboratory testing, the serum sodium is 132 mmol/L (reference range 136–144), stable since admission. Point-of-care glucose is 98 mg/dL. Aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase levels are mildly elevated at 59 U/L (13–35) and 51 U/L (7–38), respectively, but serum ammonia is undetectable. Vitamin B12, folate, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and free thyroxine are within the normal ranges. Leukocytosis is noted, with 14 × 109 cells/L (3.7–11.0), 86% neutrophils, and a mild left shift. Urinalysis is negative for leukocyte esterase, nitrites, and white blood cells.

APPROACH TO ALTERED MENTAL STATUS

1. Which of the following risk factors predisposes this patient to postoperative delirium?

- Hyponatremia

- Polypharmacy

- Family history of dementia

- Depression

Altered mental status, or encephalopathy, is one of the most common yet challenging conditions in medicine. When a consult is placed for altered mental status, it is important to determine the affected domain that has changed from the patient’s normal state. Changes can include alterations in consciousness, attention, behavior, cognition, language, speech, and praxis and can reflect varying degrees of cerebral dysfunction.

Electrolyte abnormalities

Disorders of sodium homeostasis are common in hospitalized patients and may contribute to the onset of delirium. Hyponatremia is especially frequent and often iatrogenic, with a prevalence significantly higher in women (2.1% vs 1.3%, P = .0044) and in the elderly.2

Neurologic manifestations are often the result of cerebral edema due to osmolar volume shifts.3–6 Acute hyponatremic encephalopathy is most likely to occur when sodium shifts are rapid, usually within 24 hours, and is often seen in postoperative patients requiring significant volume resuscitation with hypotonic fluids.6 Young premenopausal women appear to be at especially high risk of permanent brain damage secondary to hyponatremic encephalopathy,7 a finding that may reflect the limited compliance within the intracranial vault and lack of significant involutional parenchymal changes that occur with aging.8–11

Aging also has important effects on fluid balance, as restoration of body fluid homeostasis is slower in older patients.12

Hormonal effects of estrogen appear to play a synergistic role in the expression of arginine vasopressin in postmenopausal women, further contributing to hyponatremia.

Although our patient has mild hyponatremia, there has been no acute change in her sodium balance since admission to the hospital, and so it is unlikely to be the cause of her acute delirium. Her mild hyponatremia may in part be from hypo-osmolar maintenance fluids with dextrose 5% and 0.45% normal saline.

Mild chronic hyponatremia may affect balance and has been associated with increased mortality risk in certain chronic disease states, but this is unlikely to be the main cause of acute delirium.

Polypharmacy

Patients admitted to the hospital with polypharmacy are at high risk of drug-induced delirium. In approaching delirium, a patient’s medications should be evaluated for interactions, as well as for possible effects of newly prescribed drugs. New medications that affect cytochrome P450 enzymes warrant investigation, as do drugs with narrow therapeutic windows that the patient has been using long-term.

Consultation with a clinical pharmacist is often helpful. Macrolides, protease inhibitors, and nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers are common P450 inhibitors, while many anticonvulsants are known inducers of the P450 system. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and diuretics can lead to electrolyte imbalances such as hyponatremia, which may further predispose to bouts of delirium, as described above.

The patient’s extensive list of psychoactive medications makes polypharmacy a significant risk factor for delirium. Quetiapine and venlafaxine both cause sedation and increase the risk of serotonin syndrome. However, in this case, the patient does not have marked fever, rigidity, or hyperreflexia to corroborate that diagnosis.

Dementia

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), defines dementia as a disorder involving cognitive impairment in at least 1 cognitive domain, with a significant decline from a previous level of functioning.1 These impairments need not necessarily occur separately from bouts of delirium, but the time course for most forms of dementia tends to be progressive over a subacute to chronic duration.

Dementia increases the risk for acute confusion and delirium in hospitalized patients.13 This is partly reflected by pathophysiologic changes that leave elderly patients susceptible to the effects of anticholinergic drugs.14 Structural changes due to small-vessel ischemia may also predispose patients to seizures in the setting of metabolic derangement or critical illness. Diagnosing dementia thus remains a challenge, as dementia must be clearly distinguished from other disorders such as delirium and depression.

The acute change in this patient’s case makes the isolated diagnosis of dementia much less likely than other causes of altered mental status. Also, her previous level of function does not suggest a clinically significant personal history of impairment.

Mental illness

Several studies have examined the link between preoperative mental health disorders and postoperative delirium.15–17 Depression appears to be a risk factor for postoperative delirium in patients undergoing elective orthopedic surgery,15 and this includes elderly patients.16 While a clear etiologic link has yet to be determined, disruption of circadian rhythm and abnormal cerebral response to stress may play a role. Studies have also suggested an association between schizophrenia and delirium, though this may be related to perioperative suspension of medications.17

Bipolar disorder has not been well studied with regard to postoperative complications. However, this patient has had a previous episode of decompensated mania, therefore making bipolar disorder a plausible condition in the differential diagnosis.

CASE CONTINUED: ACUTE DETERIORATION

Without a clearly identifiable cause for our patient’s acute confusional state, neurology and medical consultants recommend neuroimaging.

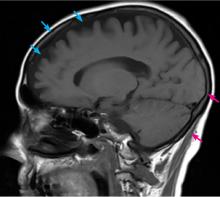

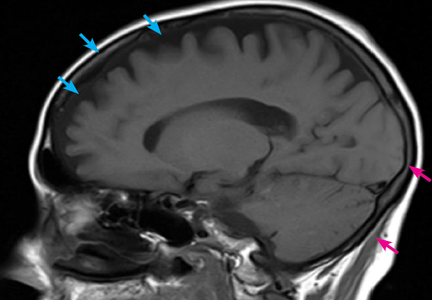

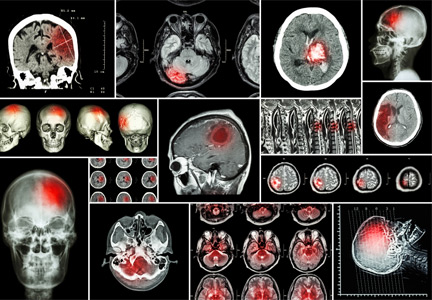

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) without contrast are ordered and performed on postoperative day 11 and demonstrate chronic small-vessel ischemic disease, consistent with our patient’s age, as well as frontotemporal atrophy. There is no evidence of mass effect, bleeding, or acute ischemia.

Overnight, she becomes obtunded, and the rapid response team is called. Her vital signs appear stable, and she is afebrile. Basic laboratory studies, imaging, and electrocardiography are repeated, and the results are unchanged from recent tests. She is transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) for closer monitoring.

2. What is most likely cause of the patient’s declining mental status, and what is the next appropriate step?

- Acute stroke: repeat MRI with contrast

- Urinary tract infection: order blood and urine cultures, and start empiric antibiotics

- Neuroleptic malignant syndrome: start dantrolene

- Seizures: order electroencephalography (EEG)

Acute stroke

Acute stroke can affect mental status and consciousness through several pathways. Stroke syndromes can vary in presentation depending on the level of cortical and subcortical involvement, with clinical manifestations including confusion, aphasia, neglect, and inattention. Wakefulness and the ability to maintain consciousness is impaired, with disruption of the ascending reticular activating system, often seen in injuries to the brainstem. Large territorial or hemispheric infarcts, with subsequent cerebral edema, can also disrupt this system and lead to cerebral herniation and coma.

MRI without contrast is extremely sensitive for ischemia and can typically detect ischemia in acute stroke within 3 to 30 minutes.18–20 Repeating the study with contrast is unlikely to provide additional benefit.

In our patient’s case, the lack of localizing neurologic symptoms, in addition to her recent negative neuroimaging workup, makes the diagnosis of acute stroke unlikely.

Infection

The role of severe infection in patients with altered mental status is well documented and likely relates to diffuse cerebral dysfunction caused by an inflammatory cascade. Less well understood is the role of occult infection, especially urinary tract infection, in otherwise immunocompetent patients. Urinary tract infection has long been thought to cause delirium in otherwise asymptomatic elderly patients, but few studies have examined this relationship, and those studies have been shown to have significant methodologic errors.21 In the absence of better data, urinary tract infection as the cause of frank delirium in an otherwise well patient should be viewed with skepticism, and alternative causes should be sought.

Although the patient has a nonspecific leukocytosis, her benign urinalysis and lack of corroborating evidence makes urinary tract infection an unlikely cause of her frank delirium.

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome is defined as fever, rigidity, mental status changes, and autonomic instability after exposure to antidopaminergic drugs. It is classically seen after administration of typical antipsychotics, though atypical antipsychotics and antiemetic drugs may be implicated as well.

Patients often exhibit agitation and confusion, which when severe may progress to mutism and catatonia. Likewise, psychotropic drugs such as quetiapine and venlafaxine, used in combination, have the additional risk of serotonin syndrome.

Additional symptoms include hyperreflexia, ataxia, and myoclonus. Withdrawal of the causative agent and supportive care are the mainstays of therapy. Targeted therapies with agents such as dantrolene, bromocriptine, and amantadine have also been reported anecdotally, but their efficacy is unclear, with variable results.22

As noted earlier, the addition of quetiapine to the patient’s already lengthy medication list could conceivably cause neuroleptic malignant syndrome or serotonin syndrome and should be considered. However, additional neurologic findings to confirm this diagnosis are lacking.

Seizures

Nonconvulsive seizure, particularly nonconvulsive status epilepticus (NCSE), is not well recognized and is particularly challenging to diagnose without EEG. In several case series of patients presenting to the emergency room with altered mental status, NCSE was found in 16% to 28% of patients in whom EEG was performed after an initial evaluation failed to show an obvious cause for the delirium.23,24 Historical features are unreliable for ruling out NCSE as a cause of delirium, as up to 41% of patients in whom the condition is ultimately diagnosed have only confusion as the presenting clinical symptom.25

Likewise, alternating ictal and postictal periods may mimic the typical waxing and waning course classically associated with delirium of other causes. Physical findings such as nystagmus, anisocoria, and hippus may be helpful but are often overlooked or absent. EEG is thus an essential requirement for the diagnosis.26

Given the lack of a clear diagnosis, a workup with EEG should be considered in this patient.

CASE CONTINUED: ADDITIONAL SIGNS

In the ICU, our patient is evaluated by the intensivist team. Her vital signs are stable, and while she is now awakening, she is unable to follow commands and remains mute. She does not initiate movement spontaneously but offers slight resistance to passive movements, holding and maintaining postures her extremities are placed in. She keeps her eyes closed, but when opened by the examining physician, dysconjugate gaze and anisocoria are noted.

3. What clinical entity is most consistent with these physical findings, and what is the next step in management?

- Catatonia secondary to bipolar disorder type I: challenge with intravenous lorazepam 2 mg

- Oculomotor nerve palsy due to enlarging intracranial aneurysm: aggressive blood pressure lowering, elevation of the head of the bed

- Toxic leukoencephalopathy: supportive care and withdrawal of the causative agent

- NCSE: challenge with intravenous lorazepam 2 mg and order EEG

Catatonia

The DSM-5 defines catatonia as a behavioral syndrome complicating an underlying psychiatric or medical condition, as opposed to a distinct diagnosis. It is most commonly encountered in psychiatric illnesses including bipolar disorder, major depression, and schizophrenia. Akinesis, stupor, mutism, and “waxy” flexibility often dominate the clinical picture.

The pathophysiology is poorly defined, but likely involves neurotransmitter imbalances particularly with an increase in N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) activity and suppression of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) activity. This hypothesis is supported by the finding that benzodiazepines, electroconvulsive therapy, and NMDA antagonists such as amantadine are all effective in treating catatonia.27,28 Findings of focal neurologic abnormalities warrant further investigation. EEG may be necessary to differentiate catatonia from NCSE, as both may respond to a benzodiazepine challenge.

As pure catatonia is a diagnosis of exclusion, further workup, including EEG, is necessary to confirm the diagnosis.

Oculomotor nerve palsy

Anisocoria together with dysconjugate gaze should prompt consideration of a lesion involving the oculomotor nerve. Loss of tonic muscle activity from the lateral rectus and superior oblique cause a downward and outward gaze. Furthermore, loss of parasympathetic tone occurs with compressive palsies of the oculomotor nerve, clinically manifesting as a mydriatic and unreactive pupil with ptosis. Given its anatomic course and proximity to other vascular and parenchymal structures, the oculomotor nerve is vulnerable to compression from many sources, including aneurysmal dilation (especially of the posterior cerebral artery), uncal herniation, and inflammation of the cavernous sinus.

Noncontrast CT and lumbar puncture are very sensitive for making the diagnosis of sentinel bleeding within the first 24 hours,29 whereas computed tomographic angiography and magnetic resonance angiography can reliably detect unruptured aneurysms as small as 3 mm.30

Conditions that can lead to oculomotor palsy are unlikely to cause an acute gain in appendicular muscle tone, as noted by the catatonia this patient is demonstrating. Also, mass lesions or bleeding associated with oculomotor palsy is likely to cause acute loss of tone. Chronic upper-motor neuron lesions lead to spasticity rather than the waxy flexibility seen in this patient. In our patient, the findings of isolated anisocoria without further clinical evidence of oculomotor nerve compression make this diagnosis unlikely.

Toxic leukoencephalopathy

Toxic leukoencephalopathy—widespread destruction of myelin, particularly in the white matter tracts that support higher cortical functions—can be caused by antineoplastic agents, immunosuppressant agents, and industrial solvents, as well as by abuse of vaporized drugs such as heroin (“chasing the dragon”). In its mild forms it may cause behavioral disturbances or inattention. In severe forms, a neurobehavioral syndrome of akinetic mutism may be present and can mimic catatonia.31

The diagnosis is often based on the clinical history and neuroimaging, particularly MRI, which demonstrates hyperintensity of the white matter tracts in T2-weighted images.32

This patient does not have a clear history of exposure to an agent typically associated with toxic leukoencephalopathy and does not have the corroborating MRI findings to support this diagnosis.

CASE CONTINUED

Because recent neuroimaging revealed no structural brain lesions and no cause for brain herniation, the patient receives a challenge of 2 mg of intravenous lorazepam to treat potential NCSE. Subsequent improvement is noted in her anisocoria, gaze deviation, and encephalopathy. EEG reveals frequent focal seizures arising from mesial frontal regions with bilateral hemisphere propagation, consistent with bifrontal focal NCSE.

As our patient is being transferred to a room for continuous EEG monitoring, her condition begins to deteriorate, and she again becomes more encephalopathic, with anisocoria and dysconjugate gaze. Additional doses of lorazepam are given (to complete a 0.1-mg/kg load), and additional therapy with intravenous fosphenytoin (20-mg/kg load) is given. Intubation is done for airway protection.

Continuous EEG monitoring reveals multiple frequent electrographic seizures arising from the bifrontal territories, concerning for persistent focal NCSE. A midazolam drip is initiated for EEG burst suppression of cerebral activity. Over 24 hours, EEG shows resolution of seizure activity. As the patient is weaned from sedation, she awakens and follows commands consistently, tolerating extubation without complications. Her neurologic status remains stable over the next 48 hours, having returned to her neurologic baseline level of functioning. She is able to be transferred out of the ICU in stable condition while continuing on scheduled antiepileptic therapy with phenytoin.

ALTERED MENTAL STATUS IN INPATIENTS

Altered mental status is one of the most frequently encountered reasons for medical consultation from nonmedical services. The workup and management of metabolic, toxic, psychiatric, and neurologic causes requires a deep appreciation for the broad differential diagnosis and a multidisciplinary approach. Physicians caring for these patients should avoid prematurely drawing conclusions when the patient’s clinical condition fails to respond to typical measures.

Delirium is a challenging adverse event in older patients during hospitalization, with a significant national financial burden of $164 billion per year.33 The prevalence of delirium in adults on hospital admission is estimated as 14% to 24%, with an inpatient hospitalization incidence ranging from 6% to 56% in general hospital patients.34 In addition, postoperative delirium has been reported in 15% to 53% of older patients.35

While delirium is preventable in 30% to 40% of cases,36,37 it remains an important independent prognostic determinant of hospital outcomes.38–40

Delirium in hospitalized patients requires a thorough, individualized workup. In our patient’s case, the clinical findings of hypoactive delirium were found to be manifestations of NCSE, a rare life-threatening and potentially reversible neurologic disease.

While establishing seizures as a diagnosis, careful attention must first be directed towards investigating environmental or metabolic triggers that may be inciting the disease. This often involves a similar workup for metabolic derangements, as seen in the approach to delirium.

The diagnosis of NCSE, while made in this patient’s case, remains challenging. Careful physical examination should assess for automatisms, “negative” symptoms (staring, aphasia, weakness), and “positive” symptoms (hallucinations, psychosis). Cataplexy, mutism, and other acute psychiatric features have been associated with NCSE,44 highlighting the importance of EEG. A trial of a benzodiazepine in conjunction with clinical and EEG monitoring may help guide clinical decision- making.

As there is no current universally accepted definition for NCSE nor an accepted agreement on required EEG diagnostic features at this time,41 accurate diagnosis is most likely to be obtained in facilities with both subspecialty neurologic consultation and EEG capabilities.

Our patient’s family history of Pick disease is interesting, as this is a progressive form of frontotemporal dementia with both sporadic and genetically linked cases. Recent studies have shown evidence that patients with neurodegenerative disease have increased seizure frequency early in the disease course,31 and efforts are under way to establish the incidence of first unprovoked seizure in patients with frontotemporal dementia. In our patient’s case, resolution of seizure activity yielded a return to her baseline level of neurologic function.

Early use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors has been shown to help with the behavioral symptoms of frontotemporal dementia,45 but increasing requirements over time may indicate progression of neurodegeneration and should warrant further appropriate investigation.

In our patient’s case, escalating dose requirements may have reflected worsening frontotemporal atrophy. However, the diagnosis of a neurodegenerative disease such as frontotemporal dementia in a patient such as ours is not definitively established at this time and is being investigated on an outpatient basis.

Given the frequency of delirium and its many risk factors in the inpatient setting, verifying a causative diagnosis can be difficult. Detailed consideration of the patient’s individual clinical circumstances, often in concert with appropriate subspecialty consultations, is essential to the evaluation. Although it is time-intensive, multidisciplinary intervention can lead to safer outcomes and shorter hospital stays.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2013. http://psychiatryonline.org/doi/book/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596. Accessed July 7, 2017.

- Mohan S, Gu S, Parikh A, Radhakrishnan J. Prevalence of hyponatremia and association with mortality: results from NHANES. Am J Med 2013; 126:1127–1137.e1.

- Sterns RH. Disorders of plasma sodium—causes, consequences, and correction. N Engl J Med 2015; 372:55–65.

- Rose B, Post T. Clinical physiology of acid-base and electrolyte disorders. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2001.

- McManus ML, Churchwell KB, Strange K. Regulation of cell volume in health and disease. N Engl J Med 1995; 333:1260–1266.

- Strange K. Regulation of solute and water balance and cell volume in the central nervous system. J Am Soc Nephrol 1992; 3:12–27.

- Ayus JC, Wheeler JM, Arieff AI. Postoperative hyponatremic encephalopathy in menstruant women. Ann Intern Med 1992; 117:891–897.

- Gur RC, Mozley PD, Resnick SM, et al. Gender differences in age effect on brain atrophy measured by magnetic resonance imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1991; 88:2845–2849.

- Rosomoff HL, Zugibe FT. Distribution of intracranial contents in experimental edema. Arch Neurol 1963; 9:26–34.

- Melton JE, Nattie EE. Brain and CSF water and ions during dilutional and isosmotic hyponatremia in the rat. Am J Physiol 1983; 244:R724–R732.

- Nattie EE, Edwards WH. Brain and CSF water and ions in newborn puppies during acute hypo- and hypernatremia. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol 1981; 51:1086–1091.

- Stachenfeld NS, DiPietro L, Palter SF, Nadel ER. Estrogen influences osmotic secretion of AVP and body water balance in postmenopausal women. Am J Physiol 1998; 274:R187–R195.

- Fick DM, Agostini JV, Inouye SK. Delirium superimposed on dementia: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002; 50:1723–1732.

- de Smet Y, Ruberg M, Serdaru M, Dubois B, Lhermitte F, Agid Y. Confusion, dementia and anticholinergics in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1982; 45:1161–1164.

- Mollon B, Mahure SA, Ding DY, Zuckerman JD, Kwon YW. The influence of a history of clinical depression on peri-operative outcomes in elective total shoulder arthroplasty: a ten-year national analysis. Bone Joint J 2016; 98-B:818–824.

- Kosar CM, Tabloski PA, Travison TG, et al. Effect of preoperative pain and depressive symptoms on the development of postoperative delirium. Lancet Psychiatry 2014; 1:431–436.

- Copeland LA, Zeber JE, Pugh MJ, Mortensen EM, Restrepo MI, Lawrence VA. Postoperative complications in the seriously mentally ill: a systematic review of the literature. Ann Surg 2008; 248:31–38.

- Warach S, Gaa J, Siewert B, Wielopolski P, Edelman RR. Acute human stroke studied by whole brain echo planar diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Neurol 1995; 37:231–241.

- Sorensen AG, Buonanno FS, Gonzalez RG, et al. Hyperacute stroke: evaluation with combined multisection diffusion-weighted and hemodynamically weighted echo-planar MR imaging. Radiology 1996; 199:391–401.

- Li F, Han S, Tatlisumak T, et al. A new method to improve in-bore middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats: demonstration with diffusion—and perfusion—weighted imaging. Stroke 1998; 29:1715–1720.

- Balogun SA, Philbrick JT. Delirium, a symptom of UTI in the elderly: fact or fable? A systematic review. Can Geriatr J 2013; 17:22–26.

- Reulbach U, Dütsch C, Biermann T, et al. Managing an effective treatment for neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Crit Care 2007; 11:R4.

- Naeije G, Depondt C, Meeus C, Korpak K, Pepersack T, Legros B. EEG patterns compatible with nonconvulsive status epilepticus are common in elderly patients with delirium: a prospective study with continuous EEG monitoring. Epilepsy Behav 2014; 36:18–21.

- Veran O, Kahane P, Thomas P, Hamelin S, Sabourdy C, Vercueil L. De novo epileptic confusion in the elderly: a 1-year prospective study. Epilepsia 2010; 51:1030–1035.

- Sutter R, Rüegg S, Kaplan PW. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of nonconvulsive status epilepticus. Opening Pandora’s box. Neurol Clin Pract 2012; 2:275–286.

- Husain AM, Horn GJ, Jacobson MP. Non-convulsive status epilepticus: usefulness of clinical features in selecting patients for urgent EEG. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003; 74:189–191.

- Ungvari GS, Chiu HF, Chow LY, Lau BS, Tang WK. Lorazepam for chronic catatonia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled cross-over study. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999; 142:393–398.

- Carroll BT, Goforth HW, Thomas C, et al. Review of adjunctive glutamate antagonist therapy in the treatment of catatonic syndromes. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2007; 19:406– 412.

- Perry JJ, Spacek A, Forbes M, et al. Is the combination of negative computed tomography result and negative lumbar puncture result sufficient to rule out subarachnoid hemorrhage? Ann Emerg Med 2008; 51:707–713.

- Li MH, Cheng YS, Li YD, et al. Large-cohort comparison between three-dimensional time-of-flight magnetic resonance and rotational digital subtraction angiographies in intracranial aneurysm detection. Stroke 2009; 40:3127–3129.

- Filley CM, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK. Toxic leukoencephalopathy. N Engl J Med 2001; 345:425–432.

- Magnetic resonance imaging of the central nervous system. Council on Scientific Affairs. Report of the Panel on Magnetic Resonance Imaging. JAMA 1988; 259:1211–1222.

- Leslie DL, Marcantonio ER, Zhang Y, Leo-Summers L, Inouye SK. One-year health care costs associated with delirium in the elderly population. Arch Intern Med 2008; 168:27–32.

- Inouye SK. Delirium in hospitalized older patients. Clin Geriatr Med 1998; 14:745–764.

- Agostini JV, Inouye SK, Hazzard W, Blass J. Delirium. In: Principles of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2003:1503–1515.

- Inouye SK, Bogardus ST Jr, Charpentier PA, et al. A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N Engl J Med 1999; 340:669–676.

- Marcantonio ER, Flacker JM, Wright RJ, Resnick NM. Reducing delirium after hip fracture: a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001; 49:516–522.

- Inouye SK, Rushing JT, Foreman MD, Palmer RM, Pompei P. Does delirium contribute to poor hospital outcomes? A three-site epidemiologic study. J Gen Intern Med 1998; 13:234–242.

- Rothschild JM, Bates DW, Leape LL. Preventable medical injuries in older patients. Arch Intern Med 2000; 160:2717–2728.

- Gillick MR, Serrell NA, Gillick LS. Adverse consequences of hospitalization in the elderly. Soc Sci Med 1982; 16:1033–1038.

- Drislane FW. Presentation, evaluation, and treatment of nonconvulsive status epilepticus. Epilepsy Behav 2000; 1:301-314.

- Rosenow F, Hamer HM, Knake S. The epidemiology of convulsive and nonconvulsive status epilepticus. Epilepsia 2007; 48(suppl 8):82–84.

- Woodford HJ, George J, Jackson M. Non-convulsive status epilepticus: a practical approach to diagnosis in confused older people. Postgrad Med J 2015; 91:655–661.

- Kaplan PW. Nonconvulsive status epilepticus in the emergency room. Epilepsia 1996; 37:643–650.

- Swartz JR, Miller BL, Lesser IM, Darby AL. Frontotemporal dementia: treatment response to serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors. J Clin Psychiatry 1997; 58:212–216.

A 64-year-old woman undergoes elective T10-S1 nerve decompression with fusion for chronic idiopathic scoliosis. Soon afterward, she develops acute urinary retention attributed to an Escherichia coli urinary tract infection and narcotic medications. She is treated with antibiotics, an indwelling catheter is inserted, and her symptoms resolve. She is transferred to the inpatient physical rehabilitation unit.

On postoperative day 9, she develops an acute change in mental status, suddenly becoming extremely anxious and falsely believing she has a “terminal illness.” A psychiatrist suggests that these symptoms are a manifestation of delirium, given the patient’s recent surgery and exposure to benzodiazepine and narcotic medications. On postoperative day 10, she is awake but is now mute and uncooperative. An internist is consulted for an evaluation for encephalopathy and delirium.

MEDICAL HISTORY

Her medical history, obtained by chart review and interviewing her husband, includes well-controlled bipolar disorder over the last 4 years, with no episodes of frank psychosis or mania. She had a “bout of delirium” 4 years earlier attributed to a catastrophic life event, but the symptoms resolved after adjustment of her anxiolytic and mood-stabilizing drugs. She also has well-controlled hypertension, hypothyroidism, and gastroesophageal reflux. Her only surgery was her recent elective procedure.

She has a family history of dementia (Pick disease in her mother).

She is married, lives with her husband, and has an adult son. She is employed as a media specialist and also teaches English as a second language. Before this hospital admission, she was described as happy and content, though her primary psychiatrist had noted intermittent anxiety. Her husband does not suspect illicit drug use and denies significant alcohol or tobacco abuse.

A thorough review of systems is not possible, given her encephalopathy. But before her acute decline, she had complained of “choking on blood” and a subjective inability to swallow.

Her home medications include dextroamphetamine extended-release, alprazolam as needed for sleep, venlafaxine extended-release, lamotrigine, lisinopril, propranolol, amlodipine, atorvastatin, levothyroxine, omeprazole, iron, and vitamin B12. At the time of the evaluation, she is on her home medications with the addition of olanzapine, vitamin D, polyethylene glycol, and an intravenous infusion of dextrose 5% with 0.45% saline at a rate of 100 mL/hour. She has allergies to latex, penicillin, peanuts, and shellfish.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

On physical examination, the patient seems healthy and appears normal for her stated age. She is wearing a spinal brace and is in no apparent distress. She is afebrile, pulse 104 beats per minute, respirations 16 breaths per minute and unlabored, and oxygen saturation good on room air. The skin is normal. No thyromegaly, bruits, or lymphadenopathy is noted. Cardiovascular, respiratory, and abdominal examinations, though limited by the spinal brace, are unremarkable. She has no evidence of peripheral edema or vascular insufficiency. Muscle bulk and tone are adequate and symmetric.

She is awake and alert and able to follow simple commands with some prompting. She does not initiate movements spontaneously. She makes some eye contact but does not track or acknowledge the interviewer consistently and does not respond verbally to questions. Her sclera are nonicteric, the pupils are equally round and reactive to light, and the external ocular muscles are intact. There is no facial asymmetry, and the tongue protrudes at midline. She blinks appropriately to threat bilaterally. Strength is at least 3/5 in the upper extremities and 2/5 in the lower extremities, though the examination is limited by lack of patient cooperation. She shows minimal grimace on noxious stimulation but does not withdraw extremities. Reflexes are present and mildly depressed symmetrically. Plantar reflexes are downgoing bilaterally.

INITIAL LABORATORY EVALUATION

On initial laboratory testing, the serum sodium is 132 mmol/L (reference range 136–144), stable since admission. Point-of-care glucose is 98 mg/dL. Aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase levels are mildly elevated at 59 U/L (13–35) and 51 U/L (7–38), respectively, but serum ammonia is undetectable. Vitamin B12, folate, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and free thyroxine are within the normal ranges. Leukocytosis is noted, with 14 × 109 cells/L (3.7–11.0), 86% neutrophils, and a mild left shift. Urinalysis is negative for leukocyte esterase, nitrites, and white blood cells.

APPROACH TO ALTERED MENTAL STATUS

1. Which of the following risk factors predisposes this patient to postoperative delirium?

- Hyponatremia

- Polypharmacy

- Family history of dementia

- Depression

Altered mental status, or encephalopathy, is one of the most common yet challenging conditions in medicine. When a consult is placed for altered mental status, it is important to determine the affected domain that has changed from the patient’s normal state. Changes can include alterations in consciousness, attention, behavior, cognition, language, speech, and praxis and can reflect varying degrees of cerebral dysfunction.

Electrolyte abnormalities

Disorders of sodium homeostasis are common in hospitalized patients and may contribute to the onset of delirium. Hyponatremia is especially frequent and often iatrogenic, with a prevalence significantly higher in women (2.1% vs 1.3%, P = .0044) and in the elderly.2

Neurologic manifestations are often the result of cerebral edema due to osmolar volume shifts.3–6 Acute hyponatremic encephalopathy is most likely to occur when sodium shifts are rapid, usually within 24 hours, and is often seen in postoperative patients requiring significant volume resuscitation with hypotonic fluids.6 Young premenopausal women appear to be at especially high risk of permanent brain damage secondary to hyponatremic encephalopathy,7 a finding that may reflect the limited compliance within the intracranial vault and lack of significant involutional parenchymal changes that occur with aging.8–11

Aging also has important effects on fluid balance, as restoration of body fluid homeostasis is slower in older patients.12

Hormonal effects of estrogen appear to play a synergistic role in the expression of arginine vasopressin in postmenopausal women, further contributing to hyponatremia.

Although our patient has mild hyponatremia, there has been no acute change in her sodium balance since admission to the hospital, and so it is unlikely to be the cause of her acute delirium. Her mild hyponatremia may in part be from hypo-osmolar maintenance fluids with dextrose 5% and 0.45% normal saline.

Mild chronic hyponatremia may affect balance and has been associated with increased mortality risk in certain chronic disease states, but this is unlikely to be the main cause of acute delirium.

Polypharmacy

Patients admitted to the hospital with polypharmacy are at high risk of drug-induced delirium. In approaching delirium, a patient’s medications should be evaluated for interactions, as well as for possible effects of newly prescribed drugs. New medications that affect cytochrome P450 enzymes warrant investigation, as do drugs with narrow therapeutic windows that the patient has been using long-term.

Consultation with a clinical pharmacist is often helpful. Macrolides, protease inhibitors, and nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers are common P450 inhibitors, while many anticonvulsants are known inducers of the P450 system. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and diuretics can lead to electrolyte imbalances such as hyponatremia, which may further predispose to bouts of delirium, as described above.

The patient’s extensive list of psychoactive medications makes polypharmacy a significant risk factor for delirium. Quetiapine and venlafaxine both cause sedation and increase the risk of serotonin syndrome. However, in this case, the patient does not have marked fever, rigidity, or hyperreflexia to corroborate that diagnosis.

Dementia

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), defines dementia as a disorder involving cognitive impairment in at least 1 cognitive domain, with a significant decline from a previous level of functioning.1 These impairments need not necessarily occur separately from bouts of delirium, but the time course for most forms of dementia tends to be progressive over a subacute to chronic duration.

Dementia increases the risk for acute confusion and delirium in hospitalized patients.13 This is partly reflected by pathophysiologic changes that leave elderly patients susceptible to the effects of anticholinergic drugs.14 Structural changes due to small-vessel ischemia may also predispose patients to seizures in the setting of metabolic derangement or critical illness. Diagnosing dementia thus remains a challenge, as dementia must be clearly distinguished from other disorders such as delirium and depression.

The acute change in this patient’s case makes the isolated diagnosis of dementia much less likely than other causes of altered mental status. Also, her previous level of function does not suggest a clinically significant personal history of impairment.

Mental illness

Several studies have examined the link between preoperative mental health disorders and postoperative delirium.15–17 Depression appears to be a risk factor for postoperative delirium in patients undergoing elective orthopedic surgery,15 and this includes elderly patients.16 While a clear etiologic link has yet to be determined, disruption of circadian rhythm and abnormal cerebral response to stress may play a role. Studies have also suggested an association between schizophrenia and delirium, though this may be related to perioperative suspension of medications.17

Bipolar disorder has not been well studied with regard to postoperative complications. However, this patient has had a previous episode of decompensated mania, therefore making bipolar disorder a plausible condition in the differential diagnosis.

CASE CONTINUED: ACUTE DETERIORATION

Without a clearly identifiable cause for our patient’s acute confusional state, neurology and medical consultants recommend neuroimaging.

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) without contrast are ordered and performed on postoperative day 11 and demonstrate chronic small-vessel ischemic disease, consistent with our patient’s age, as well as frontotemporal atrophy. There is no evidence of mass effect, bleeding, or acute ischemia.

Overnight, she becomes obtunded, and the rapid response team is called. Her vital signs appear stable, and she is afebrile. Basic laboratory studies, imaging, and electrocardiography are repeated, and the results are unchanged from recent tests. She is transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) for closer monitoring.

2. What is most likely cause of the patient’s declining mental status, and what is the next appropriate step?

- Acute stroke: repeat MRI with contrast

- Urinary tract infection: order blood and urine cultures, and start empiric antibiotics

- Neuroleptic malignant syndrome: start dantrolene

- Seizures: order electroencephalography (EEG)

Acute stroke

Acute stroke can affect mental status and consciousness through several pathways. Stroke syndromes can vary in presentation depending on the level of cortical and subcortical involvement, with clinical manifestations including confusion, aphasia, neglect, and inattention. Wakefulness and the ability to maintain consciousness is impaired, with disruption of the ascending reticular activating system, often seen in injuries to the brainstem. Large territorial or hemispheric infarcts, with subsequent cerebral edema, can also disrupt this system and lead to cerebral herniation and coma.

MRI without contrast is extremely sensitive for ischemia and can typically detect ischemia in acute stroke within 3 to 30 minutes.18–20 Repeating the study with contrast is unlikely to provide additional benefit.

In our patient’s case, the lack of localizing neurologic symptoms, in addition to her recent negative neuroimaging workup, makes the diagnosis of acute stroke unlikely.

Infection

The role of severe infection in patients with altered mental status is well documented and likely relates to diffuse cerebral dysfunction caused by an inflammatory cascade. Less well understood is the role of occult infection, especially urinary tract infection, in otherwise immunocompetent patients. Urinary tract infection has long been thought to cause delirium in otherwise asymptomatic elderly patients, but few studies have examined this relationship, and those studies have been shown to have significant methodologic errors.21 In the absence of better data, urinary tract infection as the cause of frank delirium in an otherwise well patient should be viewed with skepticism, and alternative causes should be sought.

Although the patient has a nonspecific leukocytosis, her benign urinalysis and lack of corroborating evidence makes urinary tract infection an unlikely cause of her frank delirium.

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome is defined as fever, rigidity, mental status changes, and autonomic instability after exposure to antidopaminergic drugs. It is classically seen after administration of typical antipsychotics, though atypical antipsychotics and antiemetic drugs may be implicated as well.

Patients often exhibit agitation and confusion, which when severe may progress to mutism and catatonia. Likewise, psychotropic drugs such as quetiapine and venlafaxine, used in combination, have the additional risk of serotonin syndrome.

Additional symptoms include hyperreflexia, ataxia, and myoclonus. Withdrawal of the causative agent and supportive care are the mainstays of therapy. Targeted therapies with agents such as dantrolene, bromocriptine, and amantadine have also been reported anecdotally, but their efficacy is unclear, with variable results.22

As noted earlier, the addition of quetiapine to the patient’s already lengthy medication list could conceivably cause neuroleptic malignant syndrome or serotonin syndrome and should be considered. However, additional neurologic findings to confirm this diagnosis are lacking.

Seizures

Nonconvulsive seizure, particularly nonconvulsive status epilepticus (NCSE), is not well recognized and is particularly challenging to diagnose without EEG. In several case series of patients presenting to the emergency room with altered mental status, NCSE was found in 16% to 28% of patients in whom EEG was performed after an initial evaluation failed to show an obvious cause for the delirium.23,24 Historical features are unreliable for ruling out NCSE as a cause of delirium, as up to 41% of patients in whom the condition is ultimately diagnosed have only confusion as the presenting clinical symptom.25

Likewise, alternating ictal and postictal periods may mimic the typical waxing and waning course classically associated with delirium of other causes. Physical findings such as nystagmus, anisocoria, and hippus may be helpful but are often overlooked or absent. EEG is thus an essential requirement for the diagnosis.26

Given the lack of a clear diagnosis, a workup with EEG should be considered in this patient.

CASE CONTINUED: ADDITIONAL SIGNS

In the ICU, our patient is evaluated by the intensivist team. Her vital signs are stable, and while she is now awakening, she is unable to follow commands and remains mute. She does not initiate movement spontaneously but offers slight resistance to passive movements, holding and maintaining postures her extremities are placed in. She keeps her eyes closed, but when opened by the examining physician, dysconjugate gaze and anisocoria are noted.

3. What clinical entity is most consistent with these physical findings, and what is the next step in management?

- Catatonia secondary to bipolar disorder type I: challenge with intravenous lorazepam 2 mg

- Oculomotor nerve palsy due to enlarging intracranial aneurysm: aggressive blood pressure lowering, elevation of the head of the bed

- Toxic leukoencephalopathy: supportive care and withdrawal of the causative agent

- NCSE: challenge with intravenous lorazepam 2 mg and order EEG

Catatonia

The DSM-5 defines catatonia as a behavioral syndrome complicating an underlying psychiatric or medical condition, as opposed to a distinct diagnosis. It is most commonly encountered in psychiatric illnesses including bipolar disorder, major depression, and schizophrenia. Akinesis, stupor, mutism, and “waxy” flexibility often dominate the clinical picture.

The pathophysiology is poorly defined, but likely involves neurotransmitter imbalances particularly with an increase in N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) activity and suppression of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) activity. This hypothesis is supported by the finding that benzodiazepines, electroconvulsive therapy, and NMDA antagonists such as amantadine are all effective in treating catatonia.27,28 Findings of focal neurologic abnormalities warrant further investigation. EEG may be necessary to differentiate catatonia from NCSE, as both may respond to a benzodiazepine challenge.

As pure catatonia is a diagnosis of exclusion, further workup, including EEG, is necessary to confirm the diagnosis.

Oculomotor nerve palsy

Anisocoria together with dysconjugate gaze should prompt consideration of a lesion involving the oculomotor nerve. Loss of tonic muscle activity from the lateral rectus and superior oblique cause a downward and outward gaze. Furthermore, loss of parasympathetic tone occurs with compressive palsies of the oculomotor nerve, clinically manifesting as a mydriatic and unreactive pupil with ptosis. Given its anatomic course and proximity to other vascular and parenchymal structures, the oculomotor nerve is vulnerable to compression from many sources, including aneurysmal dilation (especially of the posterior cerebral artery), uncal herniation, and inflammation of the cavernous sinus.

Noncontrast CT and lumbar puncture are very sensitive for making the diagnosis of sentinel bleeding within the first 24 hours,29 whereas computed tomographic angiography and magnetic resonance angiography can reliably detect unruptured aneurysms as small as 3 mm.30

Conditions that can lead to oculomotor palsy are unlikely to cause an acute gain in appendicular muscle tone, as noted by the catatonia this patient is demonstrating. Also, mass lesions or bleeding associated with oculomotor palsy is likely to cause acute loss of tone. Chronic upper-motor neuron lesions lead to spasticity rather than the waxy flexibility seen in this patient. In our patient, the findings of isolated anisocoria without further clinical evidence of oculomotor nerve compression make this diagnosis unlikely.

Toxic leukoencephalopathy

Toxic leukoencephalopathy—widespread destruction of myelin, particularly in the white matter tracts that support higher cortical functions—can be caused by antineoplastic agents, immunosuppressant agents, and industrial solvents, as well as by abuse of vaporized drugs such as heroin (“chasing the dragon”). In its mild forms it may cause behavioral disturbances or inattention. In severe forms, a neurobehavioral syndrome of akinetic mutism may be present and can mimic catatonia.31

The diagnosis is often based on the clinical history and neuroimaging, particularly MRI, which demonstrates hyperintensity of the white matter tracts in T2-weighted images.32

This patient does not have a clear history of exposure to an agent typically associated with toxic leukoencephalopathy and does not have the corroborating MRI findings to support this diagnosis.

CASE CONTINUED

Because recent neuroimaging revealed no structural brain lesions and no cause for brain herniation, the patient receives a challenge of 2 mg of intravenous lorazepam to treat potential NCSE. Subsequent improvement is noted in her anisocoria, gaze deviation, and encephalopathy. EEG reveals frequent focal seizures arising from mesial frontal regions with bilateral hemisphere propagation, consistent with bifrontal focal NCSE.

As our patient is being transferred to a room for continuous EEG monitoring, her condition begins to deteriorate, and she again becomes more encephalopathic, with anisocoria and dysconjugate gaze. Additional doses of lorazepam are given (to complete a 0.1-mg/kg load), and additional therapy with intravenous fosphenytoin (20-mg/kg load) is given. Intubation is done for airway protection.

Continuous EEG monitoring reveals multiple frequent electrographic seizures arising from the bifrontal territories, concerning for persistent focal NCSE. A midazolam drip is initiated for EEG burst suppression of cerebral activity. Over 24 hours, EEG shows resolution of seizure activity. As the patient is weaned from sedation, she awakens and follows commands consistently, tolerating extubation without complications. Her neurologic status remains stable over the next 48 hours, having returned to her neurologic baseline level of functioning. She is able to be transferred out of the ICU in stable condition while continuing on scheduled antiepileptic therapy with phenytoin.

ALTERED MENTAL STATUS IN INPATIENTS

Altered mental status is one of the most frequently encountered reasons for medical consultation from nonmedical services. The workup and management of metabolic, toxic, psychiatric, and neurologic causes requires a deep appreciation for the broad differential diagnosis and a multidisciplinary approach. Physicians caring for these patients should avoid prematurely drawing conclusions when the patient’s clinical condition fails to respond to typical measures.

Delirium is a challenging adverse event in older patients during hospitalization, with a significant national financial burden of $164 billion per year.33 The prevalence of delirium in adults on hospital admission is estimated as 14% to 24%, with an inpatient hospitalization incidence ranging from 6% to 56% in general hospital patients.34 In addition, postoperative delirium has been reported in 15% to 53% of older patients.35

While delirium is preventable in 30% to 40% of cases,36,37 it remains an important independent prognostic determinant of hospital outcomes.38–40

Delirium in hospitalized patients requires a thorough, individualized workup. In our patient’s case, the clinical findings of hypoactive delirium were found to be manifestations of NCSE, a rare life-threatening and potentially reversible neurologic disease.

While establishing seizures as a diagnosis, careful attention must first be directed towards investigating environmental or metabolic triggers that may be inciting the disease. This often involves a similar workup for metabolic derangements, as seen in the approach to delirium.

The diagnosis of NCSE, while made in this patient’s case, remains challenging. Careful physical examination should assess for automatisms, “negative” symptoms (staring, aphasia, weakness), and “positive” symptoms (hallucinations, psychosis). Cataplexy, mutism, and other acute psychiatric features have been associated with NCSE,44 highlighting the importance of EEG. A trial of a benzodiazepine in conjunction with clinical and EEG monitoring may help guide clinical decision- making.

As there is no current universally accepted definition for NCSE nor an accepted agreement on required EEG diagnostic features at this time,41 accurate diagnosis is most likely to be obtained in facilities with both subspecialty neurologic consultation and EEG capabilities.

Our patient’s family history of Pick disease is interesting, as this is a progressive form of frontotemporal dementia with both sporadic and genetically linked cases. Recent studies have shown evidence that patients with neurodegenerative disease have increased seizure frequency early in the disease course,31 and efforts are under way to establish the incidence of first unprovoked seizure in patients with frontotemporal dementia. In our patient’s case, resolution of seizure activity yielded a return to her baseline level of neurologic function.

Early use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors has been shown to help with the behavioral symptoms of frontotemporal dementia,45 but increasing requirements over time may indicate progression of neurodegeneration and should warrant further appropriate investigation.

In our patient’s case, escalating dose requirements may have reflected worsening frontotemporal atrophy. However, the diagnosis of a neurodegenerative disease such as frontotemporal dementia in a patient such as ours is not definitively established at this time and is being investigated on an outpatient basis.

Given the frequency of delirium and its many risk factors in the inpatient setting, verifying a causative diagnosis can be difficult. Detailed consideration of the patient’s individual clinical circumstances, often in concert with appropriate subspecialty consultations, is essential to the evaluation. Although it is time-intensive, multidisciplinary intervention can lead to safer outcomes and shorter hospital stays.

A 64-year-old woman undergoes elective T10-S1 nerve decompression with fusion for chronic idiopathic scoliosis. Soon afterward, she develops acute urinary retention attributed to an Escherichia coli urinary tract infection and narcotic medications. She is treated with antibiotics, an indwelling catheter is inserted, and her symptoms resolve. She is transferred to the inpatient physical rehabilitation unit.

On postoperative day 9, she develops an acute change in mental status, suddenly becoming extremely anxious and falsely believing she has a “terminal illness.” A psychiatrist suggests that these symptoms are a manifestation of delirium, given the patient’s recent surgery and exposure to benzodiazepine and narcotic medications. On postoperative day 10, she is awake but is now mute and uncooperative. An internist is consulted for an evaluation for encephalopathy and delirium.

MEDICAL HISTORY

Her medical history, obtained by chart review and interviewing her husband, includes well-controlled bipolar disorder over the last 4 years, with no episodes of frank psychosis or mania. She had a “bout of delirium” 4 years earlier attributed to a catastrophic life event, but the symptoms resolved after adjustment of her anxiolytic and mood-stabilizing drugs. She also has well-controlled hypertension, hypothyroidism, and gastroesophageal reflux. Her only surgery was her recent elective procedure.

She has a family history of dementia (Pick disease in her mother).

She is married, lives with her husband, and has an adult son. She is employed as a media specialist and also teaches English as a second language. Before this hospital admission, she was described as happy and content, though her primary psychiatrist had noted intermittent anxiety. Her husband does not suspect illicit drug use and denies significant alcohol or tobacco abuse.

A thorough review of systems is not possible, given her encephalopathy. But before her acute decline, she had complained of “choking on blood” and a subjective inability to swallow.

Her home medications include dextroamphetamine extended-release, alprazolam as needed for sleep, venlafaxine extended-release, lamotrigine, lisinopril, propranolol, amlodipine, atorvastatin, levothyroxine, omeprazole, iron, and vitamin B12. At the time of the evaluation, she is on her home medications with the addition of olanzapine, vitamin D, polyethylene glycol, and an intravenous infusion of dextrose 5% with 0.45% saline at a rate of 100 mL/hour. She has allergies to latex, penicillin, peanuts, and shellfish.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

On physical examination, the patient seems healthy and appears normal for her stated age. She is wearing a spinal brace and is in no apparent distress. She is afebrile, pulse 104 beats per minute, respirations 16 breaths per minute and unlabored, and oxygen saturation good on room air. The skin is normal. No thyromegaly, bruits, or lymphadenopathy is noted. Cardiovascular, respiratory, and abdominal examinations, though limited by the spinal brace, are unremarkable. She has no evidence of peripheral edema or vascular insufficiency. Muscle bulk and tone are adequate and symmetric.

She is awake and alert and able to follow simple commands with some prompting. She does not initiate movements spontaneously. She makes some eye contact but does not track or acknowledge the interviewer consistently and does not respond verbally to questions. Her sclera are nonicteric, the pupils are equally round and reactive to light, and the external ocular muscles are intact. There is no facial asymmetry, and the tongue protrudes at midline. She blinks appropriately to threat bilaterally. Strength is at least 3/5 in the upper extremities and 2/5 in the lower extremities, though the examination is limited by lack of patient cooperation. She shows minimal grimace on noxious stimulation but does not withdraw extremities. Reflexes are present and mildly depressed symmetrically. Plantar reflexes are downgoing bilaterally.

INITIAL LABORATORY EVALUATION

On initial laboratory testing, the serum sodium is 132 mmol/L (reference range 136–144), stable since admission. Point-of-care glucose is 98 mg/dL. Aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase levels are mildly elevated at 59 U/L (13–35) and 51 U/L (7–38), respectively, but serum ammonia is undetectable. Vitamin B12, folate, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and free thyroxine are within the normal ranges. Leukocytosis is noted, with 14 × 109 cells/L (3.7–11.0), 86% neutrophils, and a mild left shift. Urinalysis is negative for leukocyte esterase, nitrites, and white blood cells.

APPROACH TO ALTERED MENTAL STATUS

1. Which of the following risk factors predisposes this patient to postoperative delirium?

- Hyponatremia

- Polypharmacy

- Family history of dementia

- Depression

Altered mental status, or encephalopathy, is one of the most common yet challenging conditions in medicine. When a consult is placed for altered mental status, it is important to determine the affected domain that has changed from the patient’s normal state. Changes can include alterations in consciousness, attention, behavior, cognition, language, speech, and praxis and can reflect varying degrees of cerebral dysfunction.

Electrolyte abnormalities

Disorders of sodium homeostasis are common in hospitalized patients and may contribute to the onset of delirium. Hyponatremia is especially frequent and often iatrogenic, with a prevalence significantly higher in women (2.1% vs 1.3%, P = .0044) and in the elderly.2

Neurologic manifestations are often the result of cerebral edema due to osmolar volume shifts.3–6 Acute hyponatremic encephalopathy is most likely to occur when sodium shifts are rapid, usually within 24 hours, and is often seen in postoperative patients requiring significant volume resuscitation with hypotonic fluids.6 Young premenopausal women appear to be at especially high risk of permanent brain damage secondary to hyponatremic encephalopathy,7 a finding that may reflect the limited compliance within the intracranial vault and lack of significant involutional parenchymal changes that occur with aging.8–11

Aging also has important effects on fluid balance, as restoration of body fluid homeostasis is slower in older patients.12

Hormonal effects of estrogen appear to play a synergistic role in the expression of arginine vasopressin in postmenopausal women, further contributing to hyponatremia.

Although our patient has mild hyponatremia, there has been no acute change in her sodium balance since admission to the hospital, and so it is unlikely to be the cause of her acute delirium. Her mild hyponatremia may in part be from hypo-osmolar maintenance fluids with dextrose 5% and 0.45% normal saline.

Mild chronic hyponatremia may affect balance and has been associated with increased mortality risk in certain chronic disease states, but this is unlikely to be the main cause of acute delirium.

Polypharmacy

Patients admitted to the hospital with polypharmacy are at high risk of drug-induced delirium. In approaching delirium, a patient’s medications should be evaluated for interactions, as well as for possible effects of newly prescribed drugs. New medications that affect cytochrome P450 enzymes warrant investigation, as do drugs with narrow therapeutic windows that the patient has been using long-term.

Consultation with a clinical pharmacist is often helpful. Macrolides, protease inhibitors, and nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers are common P450 inhibitors, while many anticonvulsants are known inducers of the P450 system. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and diuretics can lead to electrolyte imbalances such as hyponatremia, which may further predispose to bouts of delirium, as described above.

The patient’s extensive list of psychoactive medications makes polypharmacy a significant risk factor for delirium. Quetiapine and venlafaxine both cause sedation and increase the risk of serotonin syndrome. However, in this case, the patient does not have marked fever, rigidity, or hyperreflexia to corroborate that diagnosis.

Dementia

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), defines dementia as a disorder involving cognitive impairment in at least 1 cognitive domain, with a significant decline from a previous level of functioning.1 These impairments need not necessarily occur separately from bouts of delirium, but the time course for most forms of dementia tends to be progressive over a subacute to chronic duration.

Dementia increases the risk for acute confusion and delirium in hospitalized patients.13 This is partly reflected by pathophysiologic changes that leave elderly patients susceptible to the effects of anticholinergic drugs.14 Structural changes due to small-vessel ischemia may also predispose patients to seizures in the setting of metabolic derangement or critical illness. Diagnosing dementia thus remains a challenge, as dementia must be clearly distinguished from other disorders such as delirium and depression.

The acute change in this patient’s case makes the isolated diagnosis of dementia much less likely than other causes of altered mental status. Also, her previous level of function does not suggest a clinically significant personal history of impairment.

Mental illness

Several studies have examined the link between preoperative mental health disorders and postoperative delirium.15–17 Depression appears to be a risk factor for postoperative delirium in patients undergoing elective orthopedic surgery,15 and this includes elderly patients.16 While a clear etiologic link has yet to be determined, disruption of circadian rhythm and abnormal cerebral response to stress may play a role. Studies have also suggested an association between schizophrenia and delirium, though this may be related to perioperative suspension of medications.17

Bipolar disorder has not been well studied with regard to postoperative complications. However, this patient has had a previous episode of decompensated mania, therefore making bipolar disorder a plausible condition in the differential diagnosis.

CASE CONTINUED: ACUTE DETERIORATION

Without a clearly identifiable cause for our patient’s acute confusional state, neurology and medical consultants recommend neuroimaging.

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) without contrast are ordered and performed on postoperative day 11 and demonstrate chronic small-vessel ischemic disease, consistent with our patient’s age, as well as frontotemporal atrophy. There is no evidence of mass effect, bleeding, or acute ischemia.

Overnight, she becomes obtunded, and the rapid response team is called. Her vital signs appear stable, and she is afebrile. Basic laboratory studies, imaging, and electrocardiography are repeated, and the results are unchanged from recent tests. She is transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) for closer monitoring.

2. What is most likely cause of the patient’s declining mental status, and what is the next appropriate step?

- Acute stroke: repeat MRI with contrast

- Urinary tract infection: order blood and urine cultures, and start empiric antibiotics

- Neuroleptic malignant syndrome: start dantrolene

- Seizures: order electroencephalography (EEG)

Acute stroke

Acute stroke can affect mental status and consciousness through several pathways. Stroke syndromes can vary in presentation depending on the level of cortical and subcortical involvement, with clinical manifestations including confusion, aphasia, neglect, and inattention. Wakefulness and the ability to maintain consciousness is impaired, with disruption of the ascending reticular activating system, often seen in injuries to the brainstem. Large territorial or hemispheric infarcts, with subsequent cerebral edema, can also disrupt this system and lead to cerebral herniation and coma.

MRI without contrast is extremely sensitive for ischemia and can typically detect ischemia in acute stroke within 3 to 30 minutes.18–20 Repeating the study with contrast is unlikely to provide additional benefit.

In our patient’s case, the lack of localizing neurologic symptoms, in addition to her recent negative neuroimaging workup, makes the diagnosis of acute stroke unlikely.

Infection

The role of severe infection in patients with altered mental status is well documented and likely relates to diffuse cerebral dysfunction caused by an inflammatory cascade. Less well understood is the role of occult infection, especially urinary tract infection, in otherwise immunocompetent patients. Urinary tract infection has long been thought to cause delirium in otherwise asymptomatic elderly patients, but few studies have examined this relationship, and those studies have been shown to have significant methodologic errors.21 In the absence of better data, urinary tract infection as the cause of frank delirium in an otherwise well patient should be viewed with skepticism, and alternative causes should be sought.

Although the patient has a nonspecific leukocytosis, her benign urinalysis and lack of corroborating evidence makes urinary tract infection an unlikely cause of her frank delirium.

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome is defined as fever, rigidity, mental status changes, and autonomic instability after exposure to antidopaminergic drugs. It is classically seen after administration of typical antipsychotics, though atypical antipsychotics and antiemetic drugs may be implicated as well.

Patients often exhibit agitation and confusion, which when severe may progress to mutism and catatonia. Likewise, psychotropic drugs such as quetiapine and venlafaxine, used in combination, have the additional risk of serotonin syndrome.

Additional symptoms include hyperreflexia, ataxia, and myoclonus. Withdrawal of the causative agent and supportive care are the mainstays of therapy. Targeted therapies with agents such as dantrolene, bromocriptine, and amantadine have also been reported anecdotally, but their efficacy is unclear, with variable results.22

As noted earlier, the addition of quetiapine to the patient’s already lengthy medication list could conceivably cause neuroleptic malignant syndrome or serotonin syndrome and should be considered. However, additional neurologic findings to confirm this diagnosis are lacking.

Seizures

Nonconvulsive seizure, particularly nonconvulsive status epilepticus (NCSE), is not well recognized and is particularly challenging to diagnose without EEG. In several case series of patients presenting to the emergency room with altered mental status, NCSE was found in 16% to 28% of patients in whom EEG was performed after an initial evaluation failed to show an obvious cause for the delirium.23,24 Historical features are unreliable for ruling out NCSE as a cause of delirium, as up to 41% of patients in whom the condition is ultimately diagnosed have only confusion as the presenting clinical symptom.25

Likewise, alternating ictal and postictal periods may mimic the typical waxing and waning course classically associated with delirium of other causes. Physical findings such as nystagmus, anisocoria, and hippus may be helpful but are often overlooked or absent. EEG is thus an essential requirement for the diagnosis.26

Given the lack of a clear diagnosis, a workup with EEG should be considered in this patient.

CASE CONTINUED: ADDITIONAL SIGNS

In the ICU, our patient is evaluated by the intensivist team. Her vital signs are stable, and while she is now awakening, she is unable to follow commands and remains mute. She does not initiate movement spontaneously but offers slight resistance to passive movements, holding and maintaining postures her extremities are placed in. She keeps her eyes closed, but when opened by the examining physician, dysconjugate gaze and anisocoria are noted.

3. What clinical entity is most consistent with these physical findings, and what is the next step in management?

- Catatonia secondary to bipolar disorder type I: challenge with intravenous lorazepam 2 mg

- Oculomotor nerve palsy due to enlarging intracranial aneurysm: aggressive blood pressure lowering, elevation of the head of the bed

- Toxic leukoencephalopathy: supportive care and withdrawal of the causative agent

- NCSE: challenge with intravenous lorazepam 2 mg and order EEG

Catatonia

The DSM-5 defines catatonia as a behavioral syndrome complicating an underlying psychiatric or medical condition, as opposed to a distinct diagnosis. It is most commonly encountered in psychiatric illnesses including bipolar disorder, major depression, and schizophrenia. Akinesis, stupor, mutism, and “waxy” flexibility often dominate the clinical picture.

The pathophysiology is poorly defined, but likely involves neurotransmitter imbalances particularly with an increase in N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) activity and suppression of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) activity. This hypothesis is supported by the finding that benzodiazepines, electroconvulsive therapy, and NMDA antagonists such as amantadine are all effective in treating catatonia.27,28 Findings of focal neurologic abnormalities warrant further investigation. EEG may be necessary to differentiate catatonia from NCSE, as both may respond to a benzodiazepine challenge.

As pure catatonia is a diagnosis of exclusion, further workup, including EEG, is necessary to confirm the diagnosis.

Oculomotor nerve palsy

Anisocoria together with dysconjugate gaze should prompt consideration of a lesion involving the oculomotor nerve. Loss of tonic muscle activity from the lateral rectus and superior oblique cause a downward and outward gaze. Furthermore, loss of parasympathetic tone occurs with compressive palsies of the oculomotor nerve, clinically manifesting as a mydriatic and unreactive pupil with ptosis. Given its anatomic course and proximity to other vascular and parenchymal structures, the oculomotor nerve is vulnerable to compression from many sources, including aneurysmal dilation (especially of the posterior cerebral artery), uncal herniation, and inflammation of the cavernous sinus.

Noncontrast CT and lumbar puncture are very sensitive for making the diagnosis of sentinel bleeding within the first 24 hours,29 whereas computed tomographic angiography and magnetic resonance angiography can reliably detect unruptured aneurysms as small as 3 mm.30

Conditions that can lead to oculomotor palsy are unlikely to cause an acute gain in appendicular muscle tone, as noted by the catatonia this patient is demonstrating. Also, mass lesions or bleeding associated with oculomotor palsy is likely to cause acute loss of tone. Chronic upper-motor neuron lesions lead to spasticity rather than the waxy flexibility seen in this patient. In our patient, the findings of isolated anisocoria without further clinical evidence of oculomotor nerve compression make this diagnosis unlikely.

Toxic leukoencephalopathy

Toxic leukoencephalopathy—widespread destruction of myelin, particularly in the white matter tracts that support higher cortical functions—can be caused by antineoplastic agents, immunosuppressant agents, and industrial solvents, as well as by abuse of vaporized drugs such as heroin (“chasing the dragon”). In its mild forms it may cause behavioral disturbances or inattention. In severe forms, a neurobehavioral syndrome of akinetic mutism may be present and can mimic catatonia.31

The diagnosis is often based on the clinical history and neuroimaging, particularly MRI, which demonstrates hyperintensity of the white matter tracts in T2-weighted images.32

This patient does not have a clear history of exposure to an agent typically associated with toxic leukoencephalopathy and does not have the corroborating MRI findings to support this diagnosis.

CASE CONTINUED