User login

PHM20 Virtual: Impact of racism in medicine

Presenters

Michael Bryant, MD – Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles

Kimberly Manning, MD – Emory University, Atlanta

Kimberly Reynolds, MD – University of Miami

Samir Shah, MD, MSCE, MHM – Cincinnati Children’s Hospital

Ndidi Unaka, MD, MEd – Cincinnati Children’s Hospital

Moderator

Erin Shaughnessy, MD – Phoenix Children’s Hospital

Session summary

This session was devoted to a discussion about how pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) as a field can address racism in medicine. The structural inequity rooted in poverty, housing problems, and differential education represents the essential social determinant of health. No longer can pediatric hospitalists neglect or be in denial of the crucial role that race plays in propagating further inequalities in our society and at our workplace. Historically Black people were exploited in research and still are disproportionately affected when it comes to infant prematurity and mortality, asthma, pain treatments, and so on. The pediatric hospitalist must explore and understand the reasons behind nonadherence and noncompliance among Black patients and always seek to understand before criticizing.

Within learning environments, we must improve how to “autocorrect” and proactively work on our own biases. Dr. Bryant pointed out that each institution has the responsibility to build on the civil rights movement and seize the moment to create a robust response to the inequities manifested during the COVID-19 epidemic, as well as the events following the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmoud Arbery, and many others. Dr. Shah called on the PHM community to take on that obligation by “stepping into the tension,” as Mark Shapiro, MD, has suggested in a conversation/podcast with Dr. Unaka.

As pediatric hospitalists, we will have to show up both individually and as constituents of institutions to address racism by specific projects looking at all data relevant for racism rather than race in quality and safety – thereby amplifying the voices of our Black patients and families, remarked Dr. Unaka. There was a brief reflection on the use of the word “allies” by Dr. Manning and Dr. Reynolds to remind the more than 200 session participants that a bidirectional framework of this process is crucial and that there is a clear need for a partnership to a common goal that should start by “a laydown of privilege of those who have it” to establish equal playing fields once and for all.

Dr. Bryant encouraged a deliberate and early thoughtful process to identify those with opportunities and help young Black people explore journeys in medicine and increase diversity among PHM faculty. Dr. Manning reminded the audience of the power that relationships have and hold in our lives, and not only those of mentors and mentees, but also relationships among all of us as humans. As with those simple situations in which we mess up and have to be able to admit it, apologize for it, and learn to move on, this requires also showing up as a mentee, articulating one’s needs, and learning to break the habits rooted in biases. Dr. Unaka warned against stereotypes and reminded us to look deeper and understand better all of our learners and their blind spots, as well as our own.

Key takeaways

- The field of PHM must recognize the role that race plays in propagating inequalities.

- Learning and mentorship environments have to be assessed for the safety of all learners and adjusted to correct (and autocorrect) as many biases as possible.

- Institutions must assume responsibilities to establish a conscious, robust response to injustice and racism in a timely and specific manner.

- Further research efforts must be made to address racism, rather than race.

- The PHM community must show up to create a new, healthy, and deliberate bidirectional framework to endorse and support diversity.

Dr. Giordano is assistant professor of pediatrics at Columbia University and a pediatric hospitalist at NewYork–Presbyterian Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital, both in New York, with an interest in surgical comanagement. She serves on the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Pediatric Special Interest Group Executive Committee and is the chair of the Education Subcommittee. She is also an advisory board member for the New York/Westchester SHM Chapter.

Presenters

Michael Bryant, MD – Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles

Kimberly Manning, MD – Emory University, Atlanta

Kimberly Reynolds, MD – University of Miami

Samir Shah, MD, MSCE, MHM – Cincinnati Children’s Hospital

Ndidi Unaka, MD, MEd – Cincinnati Children’s Hospital

Moderator

Erin Shaughnessy, MD – Phoenix Children’s Hospital

Session summary

This session was devoted to a discussion about how pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) as a field can address racism in medicine. The structural inequity rooted in poverty, housing problems, and differential education represents the essential social determinant of health. No longer can pediatric hospitalists neglect or be in denial of the crucial role that race plays in propagating further inequalities in our society and at our workplace. Historically Black people were exploited in research and still are disproportionately affected when it comes to infant prematurity and mortality, asthma, pain treatments, and so on. The pediatric hospitalist must explore and understand the reasons behind nonadherence and noncompliance among Black patients and always seek to understand before criticizing.

Within learning environments, we must improve how to “autocorrect” and proactively work on our own biases. Dr. Bryant pointed out that each institution has the responsibility to build on the civil rights movement and seize the moment to create a robust response to the inequities manifested during the COVID-19 epidemic, as well as the events following the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmoud Arbery, and many others. Dr. Shah called on the PHM community to take on that obligation by “stepping into the tension,” as Mark Shapiro, MD, has suggested in a conversation/podcast with Dr. Unaka.

As pediatric hospitalists, we will have to show up both individually and as constituents of institutions to address racism by specific projects looking at all data relevant for racism rather than race in quality and safety – thereby amplifying the voices of our Black patients and families, remarked Dr. Unaka. There was a brief reflection on the use of the word “allies” by Dr. Manning and Dr. Reynolds to remind the more than 200 session participants that a bidirectional framework of this process is crucial and that there is a clear need for a partnership to a common goal that should start by “a laydown of privilege of those who have it” to establish equal playing fields once and for all.

Dr. Bryant encouraged a deliberate and early thoughtful process to identify those with opportunities and help young Black people explore journeys in medicine and increase diversity among PHM faculty. Dr. Manning reminded the audience of the power that relationships have and hold in our lives, and not only those of mentors and mentees, but also relationships among all of us as humans. As with those simple situations in which we mess up and have to be able to admit it, apologize for it, and learn to move on, this requires also showing up as a mentee, articulating one’s needs, and learning to break the habits rooted in biases. Dr. Unaka warned against stereotypes and reminded us to look deeper and understand better all of our learners and their blind spots, as well as our own.

Key takeaways

- The field of PHM must recognize the role that race plays in propagating inequalities.

- Learning and mentorship environments have to be assessed for the safety of all learners and adjusted to correct (and autocorrect) as many biases as possible.

- Institutions must assume responsibilities to establish a conscious, robust response to injustice and racism in a timely and specific manner.

- Further research efforts must be made to address racism, rather than race.

- The PHM community must show up to create a new, healthy, and deliberate bidirectional framework to endorse and support diversity.

Dr. Giordano is assistant professor of pediatrics at Columbia University and a pediatric hospitalist at NewYork–Presbyterian Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital, both in New York, with an interest in surgical comanagement. She serves on the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Pediatric Special Interest Group Executive Committee and is the chair of the Education Subcommittee. She is also an advisory board member for the New York/Westchester SHM Chapter.

Presenters

Michael Bryant, MD – Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles

Kimberly Manning, MD – Emory University, Atlanta

Kimberly Reynolds, MD – University of Miami

Samir Shah, MD, MSCE, MHM – Cincinnati Children’s Hospital

Ndidi Unaka, MD, MEd – Cincinnati Children’s Hospital

Moderator

Erin Shaughnessy, MD – Phoenix Children’s Hospital

Session summary

This session was devoted to a discussion about how pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) as a field can address racism in medicine. The structural inequity rooted in poverty, housing problems, and differential education represents the essential social determinant of health. No longer can pediatric hospitalists neglect or be in denial of the crucial role that race plays in propagating further inequalities in our society and at our workplace. Historically Black people were exploited in research and still are disproportionately affected when it comes to infant prematurity and mortality, asthma, pain treatments, and so on. The pediatric hospitalist must explore and understand the reasons behind nonadherence and noncompliance among Black patients and always seek to understand before criticizing.

Within learning environments, we must improve how to “autocorrect” and proactively work on our own biases. Dr. Bryant pointed out that each institution has the responsibility to build on the civil rights movement and seize the moment to create a robust response to the inequities manifested during the COVID-19 epidemic, as well as the events following the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmoud Arbery, and many others. Dr. Shah called on the PHM community to take on that obligation by “stepping into the tension,” as Mark Shapiro, MD, has suggested in a conversation/podcast with Dr. Unaka.

As pediatric hospitalists, we will have to show up both individually and as constituents of institutions to address racism by specific projects looking at all data relevant for racism rather than race in quality and safety – thereby amplifying the voices of our Black patients and families, remarked Dr. Unaka. There was a brief reflection on the use of the word “allies” by Dr. Manning and Dr. Reynolds to remind the more than 200 session participants that a bidirectional framework of this process is crucial and that there is a clear need for a partnership to a common goal that should start by “a laydown of privilege of those who have it” to establish equal playing fields once and for all.

Dr. Bryant encouraged a deliberate and early thoughtful process to identify those with opportunities and help young Black people explore journeys in medicine and increase diversity among PHM faculty. Dr. Manning reminded the audience of the power that relationships have and hold in our lives, and not only those of mentors and mentees, but also relationships among all of us as humans. As with those simple situations in which we mess up and have to be able to admit it, apologize for it, and learn to move on, this requires also showing up as a mentee, articulating one’s needs, and learning to break the habits rooted in biases. Dr. Unaka warned against stereotypes and reminded us to look deeper and understand better all of our learners and their blind spots, as well as our own.

Key takeaways

- The field of PHM must recognize the role that race plays in propagating inequalities.

- Learning and mentorship environments have to be assessed for the safety of all learners and adjusted to correct (and autocorrect) as many biases as possible.

- Institutions must assume responsibilities to establish a conscious, robust response to injustice and racism in a timely and specific manner.

- Further research efforts must be made to address racism, rather than race.

- The PHM community must show up to create a new, healthy, and deliberate bidirectional framework to endorse and support diversity.

Dr. Giordano is assistant professor of pediatrics at Columbia University and a pediatric hospitalist at NewYork–Presbyterian Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital, both in New York, with an interest in surgical comanagement. She serves on the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Pediatric Special Interest Group Executive Committee and is the chair of the Education Subcommittee. She is also an advisory board member for the New York/Westchester SHM Chapter.

Clinical Progress Note: Perioperative Pain Control in Hospitalized Pediatric Patients

Pediatric hospitalists play an increasingly significant role in perioperative pain management.1 Advances in pediatric surgical comanagement may improve quality of care and reduce the length of hospitalization.2 This review is based on queries of the PubMed and Cochrane databases between January 1, 2014, and July 15, 2019, using the search terms “perioperative pain management,” “postoperative pain,” “pediatric,” and “children.” In addition, the authors reviewed key position statements from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the American Pain Society (APS), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) regarding pain management.3 This update is intended to be relevant for practicing pediatric hospitalists, with a focus on recently expanded options for pain management and judicious opioid use in hospitalized children.

PERIOPERATIVE PAIN MANAGEMENT

Postoperative pain management begins preoperatively according to the concept of the perioperative surgical home (PSH).4 The preoperative history should identify the patient’s previous positive (eg, good pain control) and negative (eg, adverse reactions) experiences with pain medications. Family and patient expectations should be discussed regarding types and sources of pain, pain duration, exacerbating/alleviating factors, and modalities available for realistic pain control because preoperative information can limit anxiety and improve outcomes. Pain specialists can perform risk assessments preoperatively and develop plans to address pharmacologic tolerance, withdrawal, and opioid-induced hyperalgesia after surgery.5 Children with chronic pain and on preoperative opioids may require more analgesia for a longer duration postoperatively. Early recognition of variability of patient’s pain perception and differences in responses to pain need to be clearly communicated across the disciplines in a collaborative model of care.

Children with medical complexity and/or cognitive, emotional, or behavioral impairments may benefit from preoperative psychosocial treatments and utilization of pain self-management training and strategies that could further reduce anxiety and optimize postoperative care because patient and parental preoperative anxiety may be associated with adverse outcomes. Validated pain assessment tools like Revised FLACC (Face, Leg, Activity, Cry, and Consolability) Scale and Individualized Numeric Rating Scale could be particularly useful in children with limitations in communication or altered pain perception; therefore, medical teams and family members should discuss their utilization preoperatively.

MULTIMODAL ANALGESIA

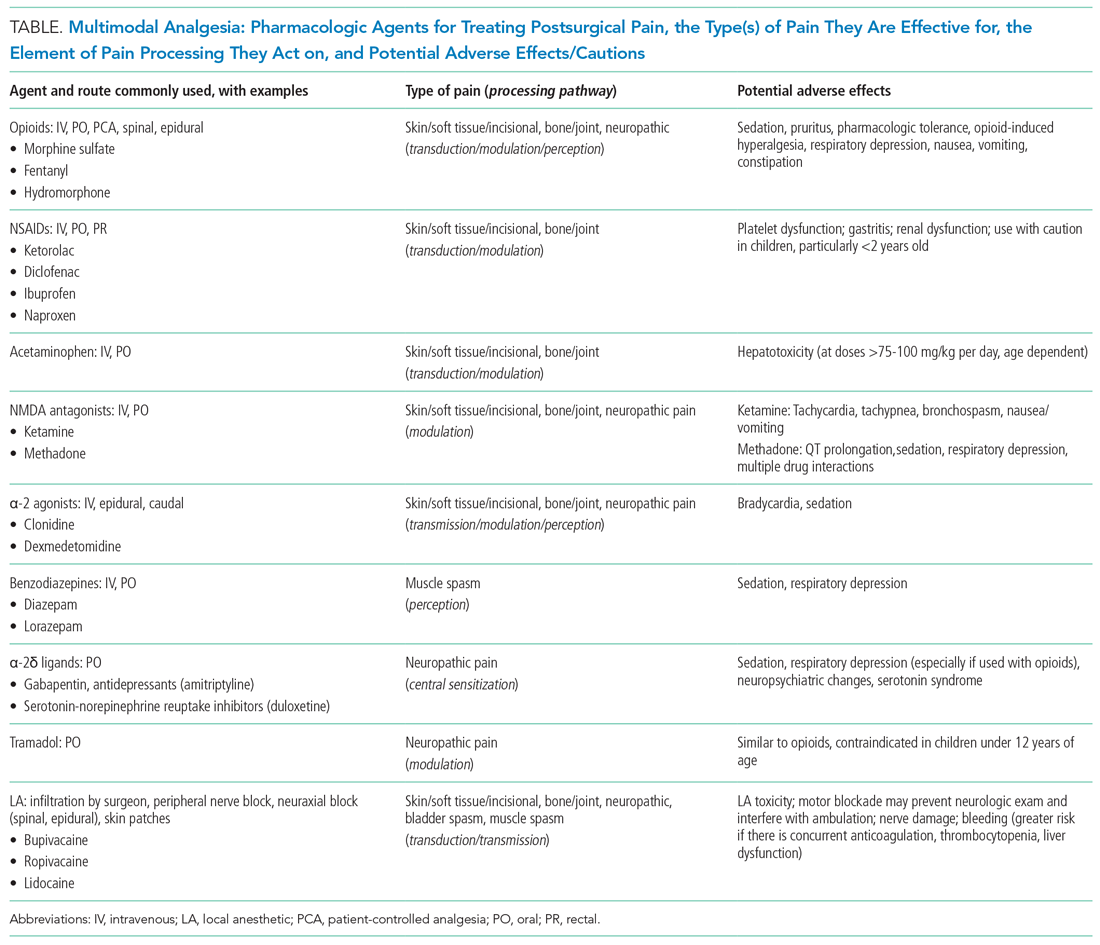

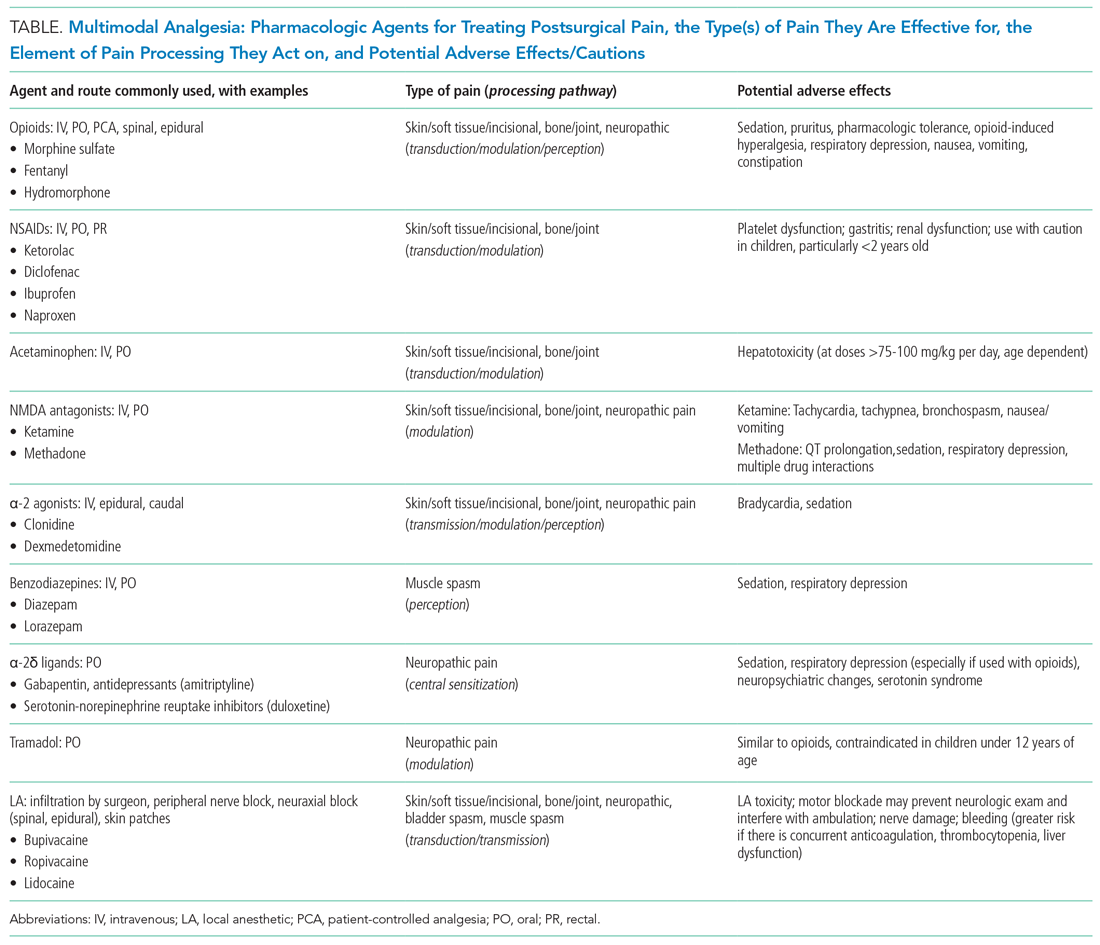

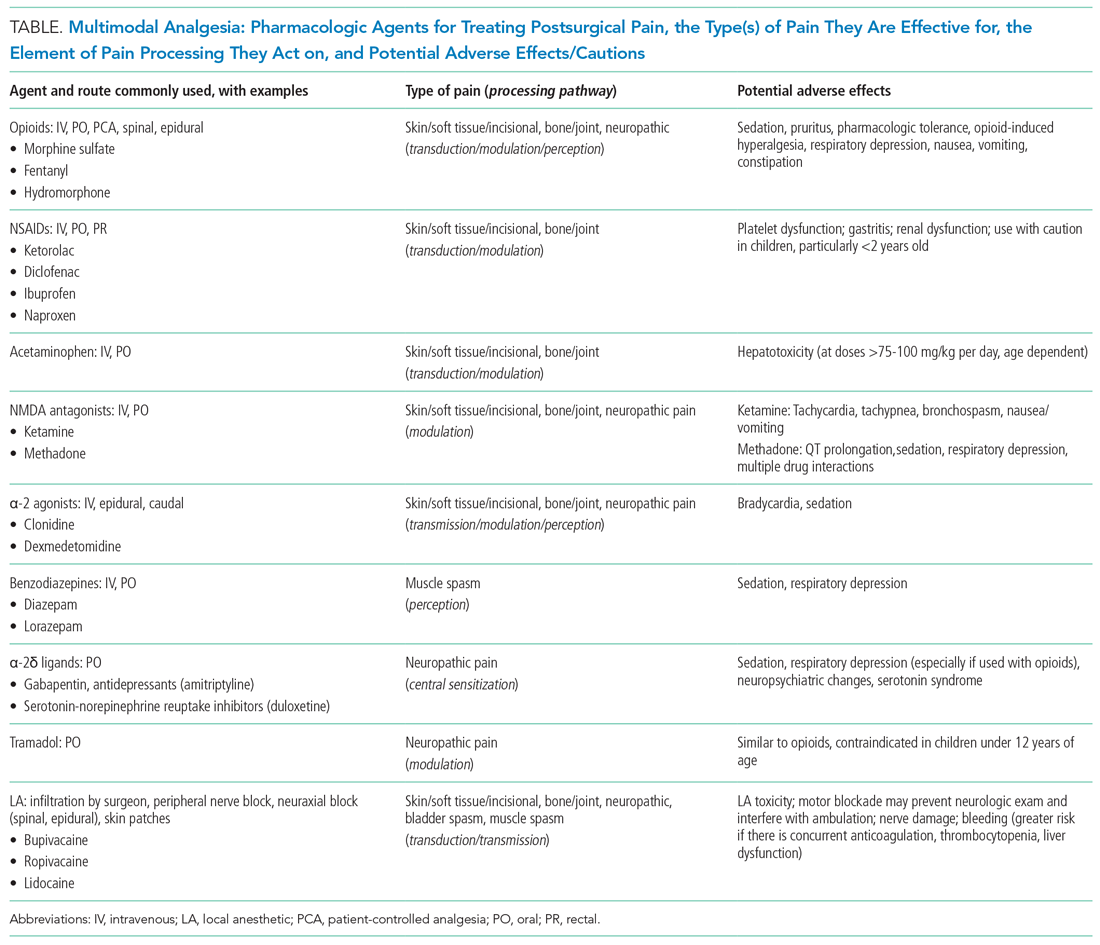

Multimodal analgesia (MMA) is a strategy that synergistically uses pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic modalities to target pain at multiple points of the pain processing pathway (Table).6 MMA can optimize pain control by addressing different types of pain (eg, incisional pain, muscle spasm, or neuropathic pain), expedite recovery, reduce potential pharmacologic side effects, and decrease opioid consumption. Patients taking opioids are at an increased risk of developing opioid-related side effects such as respiratory depression, medication tolerance, and anxiety, with resultant longer hospital stay, increased readmissions, and higher costs of care.7 Treatment for postoperative pain should prioritize appropriately dosed and precisely scheduled MMA before opioid-focused analgesia with the goals of decreasing opioid-related adverse effects, intentional misuse, diversion, and accidental ingestions. The AAP, APS, CDC, and SHM endorse the use of MMA and recommend nonpharmacologic measures and regional anesthesia.8,9 The most used modalities in MMA are discussed below.

Acetaminophen

Acetaminophen has central-acting analgesic and antipyretic properties and readily crosses the blood brain barrier, which makes it particularly useful in spine and neurological surgeries. Oral administration is preferred when feasible. The AAP recommends refraining from rectal administration of acetaminophen as analgesia in children because of concerns about toxic effects and erratic, variable absorption.10 A systematic review of six studies found no benefit in pain control between intravenous (IV) and oral (PO) administration of acetaminophen in adults.11 There is a paucity of studies in children comparing PO with IV acetaminophen perioperative efficacy. Children may benefit from IV formulations in the early postoperative period, in cases with frequent nausea and vomiting, and in those with oral medication intolerance. Since infants have greater risk of respiratory depression from opioids, IV acetaminophen may have utility in this age group. Because of the cost associated with IV formulation, some institutions restrict IV acetaminophen. However, rapidly well-controlled pain and minimization of opioid-related side effects with shorter hospital stays may lower healthcare costs despite the cost of acetaminophen itself.

NSAIDs

NSAIDs possess anti-inflammatory properties through the inhibition of cyclooxygenase and blockade of prostaglandin production. NSAID risks include bleeding, renal and gastrointestinal toxicities, and potentially delayed wound and bone healing. Ketorolac is an NSAID that continues to be widely used with demonstrated opioid-sparing effects. Many retrospective studies including large numbers of pediatric patients have not demonstrated increased risks of bleeding nor poor wound healing with short postoperative use. A Cochrane review, however, concluded that there is insufficient data to either support or reject the efficacy or safety of ketorolac for postoperative pain treatment in children, mostly because of the very low quality of evidence.12

Regional Anesthesia

Regional anesthesia, which includes central (spinal/epidural/caudal) and peripheral blocks, decreases postoperative pain and opioid-associated side effects. Blocks typically consist of local anesthetic with or without the addition of adjuncts (eg, clonidine, dexamethasone). Regional anesthesia may also improve pulmonary function, compared with that of nonregional MMA use, in patients who have thoracic or upper abdominal surgeries. While having broad applications, the utility of regional anesthesia is greatest in preterm infants/neonates and in those with underlying respiratory pathology. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials demonstrated that regional anesthesia decreased opioid consumption and minimized postoperative pain with no significant complications attributed to its use.13 Additional studies are needed to better delineate specific surgical procedures and subpopulations of pediatric patients in which regional anesthesia may provide the most benefit.

Gabapentinoids

Children receiving gabapentinoids perioperatively have been shown to have fewer adverse reactions, decreased opioid consumption, and less anxiety, as well as improved pain scores. Gabapentin is increasingly being utilized for children with idiopathic scoliosis undergoing posterior spinal fusion, and there is some evidence for improving pain control and reducing opioid use. However, a recent systematic review found a paucity of data supporting its clinical use.14 Both gabapentin and pregabalin may further increase risks of respiratory depression, especially in synergy with opioids and benzodiazepines.

Opioids

Opioids should be used with caution in pediatric patients and are reserved primarily for the management of severe acute pain. The shortest duration of the lowest effective dose of opioids should be encouraged. Patient-controlled opioid analgesia (PCA) offers benefits when parenteral postoperative analgesia is indicated: It maximizes pain relief, minimizes risk of overdose, and improves psychological well-being through self-administration of pain medicines. Basal-infusion PCA should not be routinely used because it is associated with nausea, vomiting, and respiratory depression without having superior analgesia compared with demand use only. Monitoring of side stream end-tidal capnography can readily detect respiratory depression, especially if opioids, benzodiazepines, gabapentinoids, and diphenhydramine are used concomitantly. Patient education regarding opioid use, side effects, safe storage, and disposal practices is imperative because significant amounts of opioids remain in households after completion of treatment for pain and because opioid diversion and accidental ingestions account for significant morbidity. Providers need to balance efficient pain management with opioid stewardship, complying with state and federal policies to limit harm related to opioid diversion.15

Nonpharmacological Modalities

The use of nonpharmacologic therapies, along with pharmacologic modalities, for perioperative pain management has been shown to decrease opioid use and opioid-related side effects. Trials of acupressure have demonstrated improvement in nausea and vomiting, sleep quality, and pain and anxiety scores. Nonpharmacologic treatments currently serve as a complementary approach for pain and anxiety management in the perioperative setting including acupuncture, acupressure, osteopathic manipulative treatment, massage, meditation, biofeedback, hypnotherapy, and physical/occupational, relaxation, cognitive-behavioral, chiropractic, music, and art therapies. The Joint Commission suggests consideration of such modalities by hospitals.

FUTURE CONSIDERATIONS

Pediatric hospitalists have been traditionally involved in research and patient care improvements and should continue to actively contribute to establishing evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of acute postoperative pain in hospitalized children and adolescents. The sparsity of high-quality evidence prompts the need for more research. A standardized approach to perioperative pain management in the form of checklists, pathways, and protocols for specific procedures may be useful to educate providers and patients, while also standardizing available evidence-based interventions (eg, pediatric Enhanced Recovery After Surgery [ERAS] protocols).

CONCLUSION

Combining multimodal pharmacologic and integrative nonpharmacologic modalities can decrease opioid use and related side effects and improve the perioperative care of hospitalized children. Pediatric hospitalists have an opportunity to optimize care preoperatively, practice multimodal analgesia, and contribute to reducing risk of opioid diversion post operatively.

1. Society of Hospital Medicine Co-Management Advisory Panel. A white paper on a guide to hospitalist/orthopedic surgery co-management. http://tools.hospitalmedicine.org/Implementation/Co-ManagementWhitePaper-final_5-10-10.pdf. Accessed October 11, 2019.

2. Rappaport DI, Rosenberg RE, Shaughnessy EE, et al. Pediatric hospitalist comanagement of surgical patients: Structural, quality, and financial considerations. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(11):737-742. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2266.

3. Evidence-Based Nonpharmacologic Strategies for Comprehensive Pain Care: The Consortium Pain Task Force White Paper. http://www.nonpharmpaincare.org. Accessed on October 11, 2019.

4. Vetter TR, Kain ZN. Role of perioperative surgical home in optimizing the perioperative use of opioids. Anesth Analg. 2017;125(5):1653-1657. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000002280.

5. Edwards DA, Hedrick TL, Jayaram J, et al. American Society for Enhanced Recovery and Perioperative Quality Initiative joint consensus statement on perioperative management of patients on preoperative opioid therapy. Anesth Analg. 2019;129(2):553-566. http://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000004018.

6. Micromedex (electronic version). IBM Watson Health. Greenwood Village, Colorado, USA. https://www.micromedexsolutions.com. Accessed October 10, 2019.

7. Chou R, Gordon DB, de Leon-Casasola OA, et al. Management of postoperative pain: A clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Committee on Regional Anesthesia, Executive Committee, and Administrative Council. J Pain. 2016;17(2):131-157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2015.12.008.

8. Herzig SJ, Mosher HJ, Calcaterra SL, Jena AB, Nuckols TK. Improving the safety of opioid use for acute noncancer pain in hospitalized adults: A consensus statement from the Society of Hospital Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2018;3(4):263-266. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2980.

9. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain – United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1624-1645. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.1464.

10. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Drugs. Acetaminophen toxicity in children. Pediatrics. 2001;108 (4):1020-1024. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.108.4.1020.

11. Jibril F, Sharaby S, Mohamed A, Wilby, KJ. Intravenous versus oral acetaminophen for pain: Systemic review of current evidence to support clinical decision-making. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2015;68(3):238-247. https://doi.org/10.4212/cjhp.v68i3.1458.

12. McNicol ED, Rowe E, Cooper TE. Ketorolac for postoperative pain in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;7(7). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012294.pub2.

13. Kendall MC, Castro Alves LJ, Suh EI, McCormick ZL, De Oliveira GS. Regional anesthesia to ameliorate postoperative analgesia outcomes in pediatric surgical patients: an updated systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Local Reg Anesth. 2018;11:91-109. https://doi.org/10.2147/LRA.S185554.

14. Egunsola 0, Wylie CE, Chitty KM, et al. Systematic review of the efficacy and safety of gabapentin and pregabalin for pain in children and adolescents. Anesth Analg. 2019;128(4):811-819. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000003936.

15. Harbaugh C, Gadepalli SK. Pediatric postoperative opioid prescribing and the opioid crisis. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2019;31(3):377-385. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0000000000000768.

Pediatric hospitalists play an increasingly significant role in perioperative pain management.1 Advances in pediatric surgical comanagement may improve quality of care and reduce the length of hospitalization.2 This review is based on queries of the PubMed and Cochrane databases between January 1, 2014, and July 15, 2019, using the search terms “perioperative pain management,” “postoperative pain,” “pediatric,” and “children.” In addition, the authors reviewed key position statements from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the American Pain Society (APS), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) regarding pain management.3 This update is intended to be relevant for practicing pediatric hospitalists, with a focus on recently expanded options for pain management and judicious opioid use in hospitalized children.

PERIOPERATIVE PAIN MANAGEMENT

Postoperative pain management begins preoperatively according to the concept of the perioperative surgical home (PSH).4 The preoperative history should identify the patient’s previous positive (eg, good pain control) and negative (eg, adverse reactions) experiences with pain medications. Family and patient expectations should be discussed regarding types and sources of pain, pain duration, exacerbating/alleviating factors, and modalities available for realistic pain control because preoperative information can limit anxiety and improve outcomes. Pain specialists can perform risk assessments preoperatively and develop plans to address pharmacologic tolerance, withdrawal, and opioid-induced hyperalgesia after surgery.5 Children with chronic pain and on preoperative opioids may require more analgesia for a longer duration postoperatively. Early recognition of variability of patient’s pain perception and differences in responses to pain need to be clearly communicated across the disciplines in a collaborative model of care.

Children with medical complexity and/or cognitive, emotional, or behavioral impairments may benefit from preoperative psychosocial treatments and utilization of pain self-management training and strategies that could further reduce anxiety and optimize postoperative care because patient and parental preoperative anxiety may be associated with adverse outcomes. Validated pain assessment tools like Revised FLACC (Face, Leg, Activity, Cry, and Consolability) Scale and Individualized Numeric Rating Scale could be particularly useful in children with limitations in communication or altered pain perception; therefore, medical teams and family members should discuss their utilization preoperatively.

MULTIMODAL ANALGESIA

Multimodal analgesia (MMA) is a strategy that synergistically uses pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic modalities to target pain at multiple points of the pain processing pathway (Table).6 MMA can optimize pain control by addressing different types of pain (eg, incisional pain, muscle spasm, or neuropathic pain), expedite recovery, reduce potential pharmacologic side effects, and decrease opioid consumption. Patients taking opioids are at an increased risk of developing opioid-related side effects such as respiratory depression, medication tolerance, and anxiety, with resultant longer hospital stay, increased readmissions, and higher costs of care.7 Treatment for postoperative pain should prioritize appropriately dosed and precisely scheduled MMA before opioid-focused analgesia with the goals of decreasing opioid-related adverse effects, intentional misuse, diversion, and accidental ingestions. The AAP, APS, CDC, and SHM endorse the use of MMA and recommend nonpharmacologic measures and regional anesthesia.8,9 The most used modalities in MMA are discussed below.

Acetaminophen

Acetaminophen has central-acting analgesic and antipyretic properties and readily crosses the blood brain barrier, which makes it particularly useful in spine and neurological surgeries. Oral administration is preferred when feasible. The AAP recommends refraining from rectal administration of acetaminophen as analgesia in children because of concerns about toxic effects and erratic, variable absorption.10 A systematic review of six studies found no benefit in pain control between intravenous (IV) and oral (PO) administration of acetaminophen in adults.11 There is a paucity of studies in children comparing PO with IV acetaminophen perioperative efficacy. Children may benefit from IV formulations in the early postoperative period, in cases with frequent nausea and vomiting, and in those with oral medication intolerance. Since infants have greater risk of respiratory depression from opioids, IV acetaminophen may have utility in this age group. Because of the cost associated with IV formulation, some institutions restrict IV acetaminophen. However, rapidly well-controlled pain and minimization of opioid-related side effects with shorter hospital stays may lower healthcare costs despite the cost of acetaminophen itself.

NSAIDs

NSAIDs possess anti-inflammatory properties through the inhibition of cyclooxygenase and blockade of prostaglandin production. NSAID risks include bleeding, renal and gastrointestinal toxicities, and potentially delayed wound and bone healing. Ketorolac is an NSAID that continues to be widely used with demonstrated opioid-sparing effects. Many retrospective studies including large numbers of pediatric patients have not demonstrated increased risks of bleeding nor poor wound healing with short postoperative use. A Cochrane review, however, concluded that there is insufficient data to either support or reject the efficacy or safety of ketorolac for postoperative pain treatment in children, mostly because of the very low quality of evidence.12

Regional Anesthesia

Regional anesthesia, which includes central (spinal/epidural/caudal) and peripheral blocks, decreases postoperative pain and opioid-associated side effects. Blocks typically consist of local anesthetic with or without the addition of adjuncts (eg, clonidine, dexamethasone). Regional anesthesia may also improve pulmonary function, compared with that of nonregional MMA use, in patients who have thoracic or upper abdominal surgeries. While having broad applications, the utility of regional anesthesia is greatest in preterm infants/neonates and in those with underlying respiratory pathology. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials demonstrated that regional anesthesia decreased opioid consumption and minimized postoperative pain with no significant complications attributed to its use.13 Additional studies are needed to better delineate specific surgical procedures and subpopulations of pediatric patients in which regional anesthesia may provide the most benefit.

Gabapentinoids

Children receiving gabapentinoids perioperatively have been shown to have fewer adverse reactions, decreased opioid consumption, and less anxiety, as well as improved pain scores. Gabapentin is increasingly being utilized for children with idiopathic scoliosis undergoing posterior spinal fusion, and there is some evidence for improving pain control and reducing opioid use. However, a recent systematic review found a paucity of data supporting its clinical use.14 Both gabapentin and pregabalin may further increase risks of respiratory depression, especially in synergy with opioids and benzodiazepines.

Opioids

Opioids should be used with caution in pediatric patients and are reserved primarily for the management of severe acute pain. The shortest duration of the lowest effective dose of opioids should be encouraged. Patient-controlled opioid analgesia (PCA) offers benefits when parenteral postoperative analgesia is indicated: It maximizes pain relief, minimizes risk of overdose, and improves psychological well-being through self-administration of pain medicines. Basal-infusion PCA should not be routinely used because it is associated with nausea, vomiting, and respiratory depression without having superior analgesia compared with demand use only. Monitoring of side stream end-tidal capnography can readily detect respiratory depression, especially if opioids, benzodiazepines, gabapentinoids, and diphenhydramine are used concomitantly. Patient education regarding opioid use, side effects, safe storage, and disposal practices is imperative because significant amounts of opioids remain in households after completion of treatment for pain and because opioid diversion and accidental ingestions account for significant morbidity. Providers need to balance efficient pain management with opioid stewardship, complying with state and federal policies to limit harm related to opioid diversion.15

Nonpharmacological Modalities

The use of nonpharmacologic therapies, along with pharmacologic modalities, for perioperative pain management has been shown to decrease opioid use and opioid-related side effects. Trials of acupressure have demonstrated improvement in nausea and vomiting, sleep quality, and pain and anxiety scores. Nonpharmacologic treatments currently serve as a complementary approach for pain and anxiety management in the perioperative setting including acupuncture, acupressure, osteopathic manipulative treatment, massage, meditation, biofeedback, hypnotherapy, and physical/occupational, relaxation, cognitive-behavioral, chiropractic, music, and art therapies. The Joint Commission suggests consideration of such modalities by hospitals.

FUTURE CONSIDERATIONS

Pediatric hospitalists have been traditionally involved in research and patient care improvements and should continue to actively contribute to establishing evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of acute postoperative pain in hospitalized children and adolescents. The sparsity of high-quality evidence prompts the need for more research. A standardized approach to perioperative pain management in the form of checklists, pathways, and protocols for specific procedures may be useful to educate providers and patients, while also standardizing available evidence-based interventions (eg, pediatric Enhanced Recovery After Surgery [ERAS] protocols).

CONCLUSION

Combining multimodal pharmacologic and integrative nonpharmacologic modalities can decrease opioid use and related side effects and improve the perioperative care of hospitalized children. Pediatric hospitalists have an opportunity to optimize care preoperatively, practice multimodal analgesia, and contribute to reducing risk of opioid diversion post operatively.

Pediatric hospitalists play an increasingly significant role in perioperative pain management.1 Advances in pediatric surgical comanagement may improve quality of care and reduce the length of hospitalization.2 This review is based on queries of the PubMed and Cochrane databases between January 1, 2014, and July 15, 2019, using the search terms “perioperative pain management,” “postoperative pain,” “pediatric,” and “children.” In addition, the authors reviewed key position statements from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the American Pain Society (APS), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) regarding pain management.3 This update is intended to be relevant for practicing pediatric hospitalists, with a focus on recently expanded options for pain management and judicious opioid use in hospitalized children.

PERIOPERATIVE PAIN MANAGEMENT

Postoperative pain management begins preoperatively according to the concept of the perioperative surgical home (PSH).4 The preoperative history should identify the patient’s previous positive (eg, good pain control) and negative (eg, adverse reactions) experiences with pain medications. Family and patient expectations should be discussed regarding types and sources of pain, pain duration, exacerbating/alleviating factors, and modalities available for realistic pain control because preoperative information can limit anxiety and improve outcomes. Pain specialists can perform risk assessments preoperatively and develop plans to address pharmacologic tolerance, withdrawal, and opioid-induced hyperalgesia after surgery.5 Children with chronic pain and on preoperative opioids may require more analgesia for a longer duration postoperatively. Early recognition of variability of patient’s pain perception and differences in responses to pain need to be clearly communicated across the disciplines in a collaborative model of care.

Children with medical complexity and/or cognitive, emotional, or behavioral impairments may benefit from preoperative psychosocial treatments and utilization of pain self-management training and strategies that could further reduce anxiety and optimize postoperative care because patient and parental preoperative anxiety may be associated with adverse outcomes. Validated pain assessment tools like Revised FLACC (Face, Leg, Activity, Cry, and Consolability) Scale and Individualized Numeric Rating Scale could be particularly useful in children with limitations in communication or altered pain perception; therefore, medical teams and family members should discuss their utilization preoperatively.

MULTIMODAL ANALGESIA

Multimodal analgesia (MMA) is a strategy that synergistically uses pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic modalities to target pain at multiple points of the pain processing pathway (Table).6 MMA can optimize pain control by addressing different types of pain (eg, incisional pain, muscle spasm, or neuropathic pain), expedite recovery, reduce potential pharmacologic side effects, and decrease opioid consumption. Patients taking opioids are at an increased risk of developing opioid-related side effects such as respiratory depression, medication tolerance, and anxiety, with resultant longer hospital stay, increased readmissions, and higher costs of care.7 Treatment for postoperative pain should prioritize appropriately dosed and precisely scheduled MMA before opioid-focused analgesia with the goals of decreasing opioid-related adverse effects, intentional misuse, diversion, and accidental ingestions. The AAP, APS, CDC, and SHM endorse the use of MMA and recommend nonpharmacologic measures and regional anesthesia.8,9 The most used modalities in MMA are discussed below.

Acetaminophen

Acetaminophen has central-acting analgesic and antipyretic properties and readily crosses the blood brain barrier, which makes it particularly useful in spine and neurological surgeries. Oral administration is preferred when feasible. The AAP recommends refraining from rectal administration of acetaminophen as analgesia in children because of concerns about toxic effects and erratic, variable absorption.10 A systematic review of six studies found no benefit in pain control between intravenous (IV) and oral (PO) administration of acetaminophen in adults.11 There is a paucity of studies in children comparing PO with IV acetaminophen perioperative efficacy. Children may benefit from IV formulations in the early postoperative period, in cases with frequent nausea and vomiting, and in those with oral medication intolerance. Since infants have greater risk of respiratory depression from opioids, IV acetaminophen may have utility in this age group. Because of the cost associated with IV formulation, some institutions restrict IV acetaminophen. However, rapidly well-controlled pain and minimization of opioid-related side effects with shorter hospital stays may lower healthcare costs despite the cost of acetaminophen itself.

NSAIDs

NSAIDs possess anti-inflammatory properties through the inhibition of cyclooxygenase and blockade of prostaglandin production. NSAID risks include bleeding, renal and gastrointestinal toxicities, and potentially delayed wound and bone healing. Ketorolac is an NSAID that continues to be widely used with demonstrated opioid-sparing effects. Many retrospective studies including large numbers of pediatric patients have not demonstrated increased risks of bleeding nor poor wound healing with short postoperative use. A Cochrane review, however, concluded that there is insufficient data to either support or reject the efficacy or safety of ketorolac for postoperative pain treatment in children, mostly because of the very low quality of evidence.12

Regional Anesthesia

Regional anesthesia, which includes central (spinal/epidural/caudal) and peripheral blocks, decreases postoperative pain and opioid-associated side effects. Blocks typically consist of local anesthetic with or without the addition of adjuncts (eg, clonidine, dexamethasone). Regional anesthesia may also improve pulmonary function, compared with that of nonregional MMA use, in patients who have thoracic or upper abdominal surgeries. While having broad applications, the utility of regional anesthesia is greatest in preterm infants/neonates and in those with underlying respiratory pathology. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials demonstrated that regional anesthesia decreased opioid consumption and minimized postoperative pain with no significant complications attributed to its use.13 Additional studies are needed to better delineate specific surgical procedures and subpopulations of pediatric patients in which regional anesthesia may provide the most benefit.

Gabapentinoids

Children receiving gabapentinoids perioperatively have been shown to have fewer adverse reactions, decreased opioid consumption, and less anxiety, as well as improved pain scores. Gabapentin is increasingly being utilized for children with idiopathic scoliosis undergoing posterior spinal fusion, and there is some evidence for improving pain control and reducing opioid use. However, a recent systematic review found a paucity of data supporting its clinical use.14 Both gabapentin and pregabalin may further increase risks of respiratory depression, especially in synergy with opioids and benzodiazepines.

Opioids

Opioids should be used with caution in pediatric patients and are reserved primarily for the management of severe acute pain. The shortest duration of the lowest effective dose of opioids should be encouraged. Patient-controlled opioid analgesia (PCA) offers benefits when parenteral postoperative analgesia is indicated: It maximizes pain relief, minimizes risk of overdose, and improves psychological well-being through self-administration of pain medicines. Basal-infusion PCA should not be routinely used because it is associated with nausea, vomiting, and respiratory depression without having superior analgesia compared with demand use only. Monitoring of side stream end-tidal capnography can readily detect respiratory depression, especially if opioids, benzodiazepines, gabapentinoids, and diphenhydramine are used concomitantly. Patient education regarding opioid use, side effects, safe storage, and disposal practices is imperative because significant amounts of opioids remain in households after completion of treatment for pain and because opioid diversion and accidental ingestions account for significant morbidity. Providers need to balance efficient pain management with opioid stewardship, complying with state and federal policies to limit harm related to opioid diversion.15

Nonpharmacological Modalities

The use of nonpharmacologic therapies, along with pharmacologic modalities, for perioperative pain management has been shown to decrease opioid use and opioid-related side effects. Trials of acupressure have demonstrated improvement in nausea and vomiting, sleep quality, and pain and anxiety scores. Nonpharmacologic treatments currently serve as a complementary approach for pain and anxiety management in the perioperative setting including acupuncture, acupressure, osteopathic manipulative treatment, massage, meditation, biofeedback, hypnotherapy, and physical/occupational, relaxation, cognitive-behavioral, chiropractic, music, and art therapies. The Joint Commission suggests consideration of such modalities by hospitals.

FUTURE CONSIDERATIONS

Pediatric hospitalists have been traditionally involved in research and patient care improvements and should continue to actively contribute to establishing evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of acute postoperative pain in hospitalized children and adolescents. The sparsity of high-quality evidence prompts the need for more research. A standardized approach to perioperative pain management in the form of checklists, pathways, and protocols for specific procedures may be useful to educate providers and patients, while also standardizing available evidence-based interventions (eg, pediatric Enhanced Recovery After Surgery [ERAS] protocols).

CONCLUSION

Combining multimodal pharmacologic and integrative nonpharmacologic modalities can decrease opioid use and related side effects and improve the perioperative care of hospitalized children. Pediatric hospitalists have an opportunity to optimize care preoperatively, practice multimodal analgesia, and contribute to reducing risk of opioid diversion post operatively.

1. Society of Hospital Medicine Co-Management Advisory Panel. A white paper on a guide to hospitalist/orthopedic surgery co-management. http://tools.hospitalmedicine.org/Implementation/Co-ManagementWhitePaper-final_5-10-10.pdf. Accessed October 11, 2019.

2. Rappaport DI, Rosenberg RE, Shaughnessy EE, et al. Pediatric hospitalist comanagement of surgical patients: Structural, quality, and financial considerations. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(11):737-742. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2266.

3. Evidence-Based Nonpharmacologic Strategies for Comprehensive Pain Care: The Consortium Pain Task Force White Paper. http://www.nonpharmpaincare.org. Accessed on October 11, 2019.

4. Vetter TR, Kain ZN. Role of perioperative surgical home in optimizing the perioperative use of opioids. Anesth Analg. 2017;125(5):1653-1657. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000002280.

5. Edwards DA, Hedrick TL, Jayaram J, et al. American Society for Enhanced Recovery and Perioperative Quality Initiative joint consensus statement on perioperative management of patients on preoperative opioid therapy. Anesth Analg. 2019;129(2):553-566. http://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000004018.

6. Micromedex (electronic version). IBM Watson Health. Greenwood Village, Colorado, USA. https://www.micromedexsolutions.com. Accessed October 10, 2019.

7. Chou R, Gordon DB, de Leon-Casasola OA, et al. Management of postoperative pain: A clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Committee on Regional Anesthesia, Executive Committee, and Administrative Council. J Pain. 2016;17(2):131-157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2015.12.008.

8. Herzig SJ, Mosher HJ, Calcaterra SL, Jena AB, Nuckols TK. Improving the safety of opioid use for acute noncancer pain in hospitalized adults: A consensus statement from the Society of Hospital Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2018;3(4):263-266. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2980.

9. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain – United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1624-1645. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.1464.

10. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Drugs. Acetaminophen toxicity in children. Pediatrics. 2001;108 (4):1020-1024. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.108.4.1020.

11. Jibril F, Sharaby S, Mohamed A, Wilby, KJ. Intravenous versus oral acetaminophen for pain: Systemic review of current evidence to support clinical decision-making. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2015;68(3):238-247. https://doi.org/10.4212/cjhp.v68i3.1458.

12. McNicol ED, Rowe E, Cooper TE. Ketorolac for postoperative pain in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;7(7). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012294.pub2.

13. Kendall MC, Castro Alves LJ, Suh EI, McCormick ZL, De Oliveira GS. Regional anesthesia to ameliorate postoperative analgesia outcomes in pediatric surgical patients: an updated systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Local Reg Anesth. 2018;11:91-109. https://doi.org/10.2147/LRA.S185554.

14. Egunsola 0, Wylie CE, Chitty KM, et al. Systematic review of the efficacy and safety of gabapentin and pregabalin for pain in children and adolescents. Anesth Analg. 2019;128(4):811-819. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000003936.

15. Harbaugh C, Gadepalli SK. Pediatric postoperative opioid prescribing and the opioid crisis. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2019;31(3):377-385. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0000000000000768.

1. Society of Hospital Medicine Co-Management Advisory Panel. A white paper on a guide to hospitalist/orthopedic surgery co-management. http://tools.hospitalmedicine.org/Implementation/Co-ManagementWhitePaper-final_5-10-10.pdf. Accessed October 11, 2019.

2. Rappaport DI, Rosenberg RE, Shaughnessy EE, et al. Pediatric hospitalist comanagement of surgical patients: Structural, quality, and financial considerations. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(11):737-742. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2266.

3. Evidence-Based Nonpharmacologic Strategies for Comprehensive Pain Care: The Consortium Pain Task Force White Paper. http://www.nonpharmpaincare.org. Accessed on October 11, 2019.

4. Vetter TR, Kain ZN. Role of perioperative surgical home in optimizing the perioperative use of opioids. Anesth Analg. 2017;125(5):1653-1657. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000002280.

5. Edwards DA, Hedrick TL, Jayaram J, et al. American Society for Enhanced Recovery and Perioperative Quality Initiative joint consensus statement on perioperative management of patients on preoperative opioid therapy. Anesth Analg. 2019;129(2):553-566. http://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000004018.

6. Micromedex (electronic version). IBM Watson Health. Greenwood Village, Colorado, USA. https://www.micromedexsolutions.com. Accessed October 10, 2019.

7. Chou R, Gordon DB, de Leon-Casasola OA, et al. Management of postoperative pain: A clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Committee on Regional Anesthesia, Executive Committee, and Administrative Council. J Pain. 2016;17(2):131-157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2015.12.008.

8. Herzig SJ, Mosher HJ, Calcaterra SL, Jena AB, Nuckols TK. Improving the safety of opioid use for acute noncancer pain in hospitalized adults: A consensus statement from the Society of Hospital Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2018;3(4):263-266. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2980.

9. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain – United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1624-1645. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.1464.

10. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Drugs. Acetaminophen toxicity in children. Pediatrics. 2001;108 (4):1020-1024. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.108.4.1020.

11. Jibril F, Sharaby S, Mohamed A, Wilby, KJ. Intravenous versus oral acetaminophen for pain: Systemic review of current evidence to support clinical decision-making. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2015;68(3):238-247. https://doi.org/10.4212/cjhp.v68i3.1458.

12. McNicol ED, Rowe E, Cooper TE. Ketorolac for postoperative pain in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;7(7). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012294.pub2.

13. Kendall MC, Castro Alves LJ, Suh EI, McCormick ZL, De Oliveira GS. Regional anesthesia to ameliorate postoperative analgesia outcomes in pediatric surgical patients: an updated systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Local Reg Anesth. 2018;11:91-109. https://doi.org/10.2147/LRA.S185554.

14. Egunsola 0, Wylie CE, Chitty KM, et al. Systematic review of the efficacy and safety of gabapentin and pregabalin for pain in children and adolescents. Anesth Analg. 2019;128(4):811-819. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000003936.

15. Harbaugh C, Gadepalli SK. Pediatric postoperative opioid prescribing and the opioid crisis. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2019;31(3):377-385. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0000000000000768.

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

PHM 19: PREP yourself for the PHM boards

Get ready for the first-ever ABP PHM exam

Presenters

Jared Austin, MD, FAAP

Ryan Bode, MD, FAAP

Jeremy Kern, MD, FAAP

Mary Ottolini, MD, MPH, MEd, FAAP

Stacy Pierson, MD, FAAP

Mary Rocha, MD, MPH, FAAP

Susan Walley, MD, CTTS, FAAP

Session summary

Professional development sessions at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2019 conference intended to further educate pediatric hospitalists and advance their careers. In November 2019, many pediatric hospitalists will be taking subspecialty PHM boards for the very first time. This PHM19 session had clear objectives: to describe the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) PHM board content areas, to analyze common knowledge gaps in PREP PHM, and to examine different approaches to clinical management of PHM patients.

The session opened with a brief history of a vision of PHM and the story of its realization. In 2016, a group of eight stalwart writers, four new writers, and three editors created PREP 2018 and 2019 questions that were released in full prior to November 2019. The ABP will offer the board exam in 2019, 2021, and 2023

The exam content domains include the following:

- Medical conditions.

- Behavioral and mental health conditions.

- Newborn care.

- Children with medical complexity.

- Medical procedures.

- Patient and family centered care.

- Transitions of care.

- Quality improvement, patient safety and system based improvement.

- Evidence-based, high-value care.

- Advocacy and leadership.

- Ethics, legal issues, and human rights.

- Teaching and education.

- Core knowledge in scholarly activities.

Each question consists of a case vignette, question, response choices, critiques, PREP PEARLs, and references. There are also additional PREP Ponder Points that intend to prompt reflection on practice change.

For the remainder of the session presenters reviewed the PHM PREP questions that were most frequently answered incorrectly. Some of the topics included: asthma vs. anaphylaxis, venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in surgical patients, postoperative feeding regimens, transmission-based precautions, febrile neonates, Ebola, medical child abuse, absolute indications for intubation, toxic megacolon, palivizumab prophylaxis guidelines, key driver diagrams, and infantile hemangiomas.

Key takeaway

Pediatric hospitalists all over the United States will for the first time ever take PHM boards in November 2019. The exam content domains were demonstrated in detail, and several often incorrectly answered PREP questions were presented and discussed.

Dr. Giordano is assistant professor in pediatrics at Columbia University Medical Center, New York.

Get ready for the first-ever ABP PHM exam

Get ready for the first-ever ABP PHM exam

Presenters

Jared Austin, MD, FAAP

Ryan Bode, MD, FAAP

Jeremy Kern, MD, FAAP

Mary Ottolini, MD, MPH, MEd, FAAP

Stacy Pierson, MD, FAAP

Mary Rocha, MD, MPH, FAAP

Susan Walley, MD, CTTS, FAAP

Session summary

Professional development sessions at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2019 conference intended to further educate pediatric hospitalists and advance their careers. In November 2019, many pediatric hospitalists will be taking subspecialty PHM boards for the very first time. This PHM19 session had clear objectives: to describe the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) PHM board content areas, to analyze common knowledge gaps in PREP PHM, and to examine different approaches to clinical management of PHM patients.

The session opened with a brief history of a vision of PHM and the story of its realization. In 2016, a group of eight stalwart writers, four new writers, and three editors created PREP 2018 and 2019 questions that were released in full prior to November 2019. The ABP will offer the board exam in 2019, 2021, and 2023

The exam content domains include the following:

- Medical conditions.

- Behavioral and mental health conditions.

- Newborn care.

- Children with medical complexity.

- Medical procedures.

- Patient and family centered care.

- Transitions of care.

- Quality improvement, patient safety and system based improvement.

- Evidence-based, high-value care.

- Advocacy and leadership.

- Ethics, legal issues, and human rights.

- Teaching and education.

- Core knowledge in scholarly activities.

Each question consists of a case vignette, question, response choices, critiques, PREP PEARLs, and references. There are also additional PREP Ponder Points that intend to prompt reflection on practice change.

For the remainder of the session presenters reviewed the PHM PREP questions that were most frequently answered incorrectly. Some of the topics included: asthma vs. anaphylaxis, venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in surgical patients, postoperative feeding regimens, transmission-based precautions, febrile neonates, Ebola, medical child abuse, absolute indications for intubation, toxic megacolon, palivizumab prophylaxis guidelines, key driver diagrams, and infantile hemangiomas.

Key takeaway

Pediatric hospitalists all over the United States will for the first time ever take PHM boards in November 2019. The exam content domains were demonstrated in detail, and several often incorrectly answered PREP questions were presented and discussed.

Dr. Giordano is assistant professor in pediatrics at Columbia University Medical Center, New York.

Presenters

Jared Austin, MD, FAAP

Ryan Bode, MD, FAAP

Jeremy Kern, MD, FAAP

Mary Ottolini, MD, MPH, MEd, FAAP

Stacy Pierson, MD, FAAP

Mary Rocha, MD, MPH, FAAP

Susan Walley, MD, CTTS, FAAP

Session summary

Professional development sessions at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2019 conference intended to further educate pediatric hospitalists and advance their careers. In November 2019, many pediatric hospitalists will be taking subspecialty PHM boards for the very first time. This PHM19 session had clear objectives: to describe the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) PHM board content areas, to analyze common knowledge gaps in PREP PHM, and to examine different approaches to clinical management of PHM patients.

The session opened with a brief history of a vision of PHM and the story of its realization. In 2016, a group of eight stalwart writers, four new writers, and three editors created PREP 2018 and 2019 questions that were released in full prior to November 2019. The ABP will offer the board exam in 2019, 2021, and 2023

The exam content domains include the following:

- Medical conditions.

- Behavioral and mental health conditions.

- Newborn care.

- Children with medical complexity.

- Medical procedures.

- Patient and family centered care.

- Transitions of care.

- Quality improvement, patient safety and system based improvement.

- Evidence-based, high-value care.

- Advocacy and leadership.

- Ethics, legal issues, and human rights.

- Teaching and education.

- Core knowledge in scholarly activities.

Each question consists of a case vignette, question, response choices, critiques, PREP PEARLs, and references. There are also additional PREP Ponder Points that intend to prompt reflection on practice change.

For the remainder of the session presenters reviewed the PHM PREP questions that were most frequently answered incorrectly. Some of the topics included: asthma vs. anaphylaxis, venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in surgical patients, postoperative feeding regimens, transmission-based precautions, febrile neonates, Ebola, medical child abuse, absolute indications for intubation, toxic megacolon, palivizumab prophylaxis guidelines, key driver diagrams, and infantile hemangiomas.

Key takeaway

Pediatric hospitalists all over the United States will for the first time ever take PHM boards in November 2019. The exam content domains were demonstrated in detail, and several often incorrectly answered PREP questions were presented and discussed.

Dr. Giordano is assistant professor in pediatrics at Columbia University Medical Center, New York.