User login

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: A complex disease

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a complex disease. Most people who carry the mutations that cause it are never affected at any point in their life, but some are affected at a young age. And in rare but tragic cases, some die suddenly while competing in sports. With such a wide range of phenotypic expressions, a single therapy does not fit all.

HCM is more common than once thought. Since the discovery of its genetic predisposition in 1960, it has come to be recognized as the most common heritable cardiovascular disease.1 Although earlier epidemiologic studies had estimated a prevalence of 1 in 500 (0.2%) of the general population, genetic testing and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) now show that up to 1 in 200 (0.5%) of all people may be affected.1,2 Its prevalence is significant in all ethnic groups.

This review outlines our expanding knowledge of the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and clinical management of HCM.

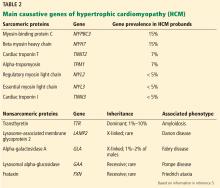

A PLETHORA OF MUTATIONS IN CARDIAC SARCOMERIC GENES

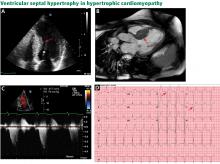

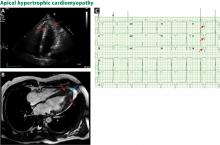

The genetic differences within HCM result in varying degrees and locations of left ventricular hypertrophy. Any segment of the ventricle can be involved, although HCM is classically asymmetric and mainly involves the septum (Figure 1). A variant form of HCM involves the apex of the heart (Figure 2).

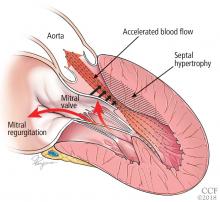

LEFT VENTRICULAR OUTFLOW TRACT OBSTRUCTION

Only in the last decade has the significance of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in HCM been truly appreciated. The degree of obstruction in HCM is dynamic, as opposed to the fixed obstruction in patients with aortic stenosis or congenital subvalvular membranes. Therefore, in HCM, exercise or drugs (eg, dobutamine) that increase cardiac contractility increase the obstruction, as do maneuvers or drugs (the Valsalva maneuver, nitrates) that reduce filling of the left ventricle.

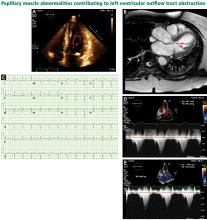

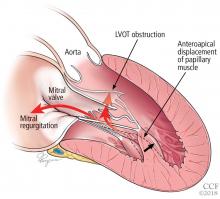

A less common source of dynamic obstruction is the papillary muscles (Figure 4). Hypertrophy of the papillary muscles can result in obstruction by these muscles themselves, which is visible on echocardiography. Anatomic variations include anteroapical displacement or bifid papillary muscles, and these variants can be associated with dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, even with no evidence of septal thickening (Figure 5).7,8 Recognizing this patient subset has important implications for management, as discussed below.

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

The clinical presentation varies

Even if patients harbor the same genetic variant, the clinical presentation can differ widely. Although the most feared presentation is sudden cardiac death, particularly in young athletes, most patients have no symptoms and can anticipate a normal life expectancy. The annual incidence of sudden cardiac death in all HCM patients is estimated at less than 1%.10 Sudden cardiac death in HCM patients is most often due to ventricular tachyarrhythmias and most often occurs in asymptomatic patients under age 35.

Physical findings are nonspecific

It can be difficult to distinguish the murmur of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in HCM from a murmur related to aortic stenosis by auscultation alone. The simplest clinical method for telling them apart involves the Valsalva maneuver: bearing down creates a positive intrathoracic pressure and limits venous return, thus decreasing intracardiac filling pressure. This in turn results in less separation between the mitral valve and the ventricular septum in HCM, which increases obstruction and therefore makes the murmur louder. In contrast, in patients with fixed obstruction due to aortic stenosis, the murmur will decrease in intensity owing to the reduced flow associated with reduced preload.

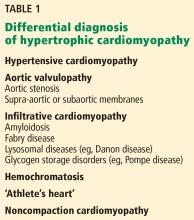

Laboratory testing for phenocopies of HCM

A metabolic panel will show derangements in liver function and glucose levels in patients with glycogen storage disorders such as Pompe disease.

Serum creatinine. Renal dysfunction will be seen in patients with Fabry disease or amyloidosis.

Creatine kinase may be elevated in patients with Danon disease.

Electrocardiographic findings are common

More than 90% of HCM patients have electrocardiographic abnormalities. Although the findings can vary widely, common manifestations include:

- Left ventricular hypertrophy

- A pseudoinfarct pattern with Q waves in the anterolateral leads

- Repolarization changes such as T-wave inversions and horizontal or down-sloping ST segments.

Apical HCM, seen mainly in Asian populations, often presents with giant T-wave inversion (> 10 mm) in the anterolateral leads, most prominent in V4, V5, and V6.

Notably, the degree of electrocardiographic abnormalities does not correlate with the severity or pattern of hypertrophy.9 Electrocardiography lacks specificity for definitive diagnosis, and further diagnostic testing should therefore be pursued.

Echocardiography: Initial imaging test

Transthoracic echocardiography is the initial imaging test in patients with suspected HCM, allowing for cost-effective quantitative and qualitative assessment of left ventricular morphology and function. Left ventricular hypertrophy is considered pathologic if wall thickness is 15 mm or greater without a known cause. Transthoracic echocardiography also allows for evaluation of left atrial volume and mitral valve anatomy and function.

Speckle tracking imaging is an advanced echocardiographic technique that measures strain. Its major advantage is in identifying early abnormalities in genotype-positive, phenotype-negative HCM patients, ie, people who harbor mutations but who have no clinical symptoms or signs of HCM, potentially allowing for modification of the natural history of HCM.12 Strain imaging can also differentiate between physiologic hypertrophy (“athlete’s heart”) and hypertension and HCM.13,14

The utility of echocardiography in HCM is heavily influenced by the sonographer’s experience in obtaining adequate acoustic windows. This may be more difficult in obese patients, patients with advanced obstructive lung disease or pleural effusions, and women with breast implants.

Magnetic resonance imaging

MRI has an emerging role in both diagnosing and predicting risk in HCM, and is routinely done as an adjunct to transthoracic echocardiography on initial diagnosis in our tertiary referral center. It is particularly useful in patients suspected of having apical hypertrophy (Figure 2), in whom the diagnosis may be missed in up to 10% on transthoracic echocardiography alone.15 MRI can also enhance the assessment of left ventricular hypertrophy and has been shown to improve the diagnostic classification of HCM.16 It is the best way to assess myocardial tissue abnormalities, and late gadolinium enhancement to detect interstitial fibrosis can be used for further prognostication. While historically the primary role of MRI in HCM has been in phenotype classification, there is currently much interest in its role in risk stratification of HCM patients for ICD implantation.

MRI with late gadolinium enhancement provides insight into the location, pattern, and extent of myocardial fibrosis; the extent of fibrosis has been shown to be a strong independent predictor of poor outcomes, including sudden cardiac death.17–20 However, late gadolinium enhancement can be technically challenging, as variations in the timing of postcontrast imaging, sequences for measuring late gadolinium enhancement, or detection thresholds can result in widely variable image quality. Cardiac MRI should therefore be performed at an experienced center with standardized imaging protocols in place.

Current guidelines recommend considering cardiac MRI if a patient’s risk of sudden cardiac death remains inconclusive after conventional risk stratification, as discussed below.9,21

Stress testing for risk stratification

Exercise stress electrocardiography. Treadmill exercise stress testing with electrocardiography and hemodynamic monitoring was one of the first tools used for risk stratification in HCM.

Although systolic blood pressure normally increases by at least 20 mm Hg with exercise, one-quarter of HCM patients have either a blunted response (failure of systolic blood pressure to increase by at least 20 mm Hg) or a hypotensive response (a drop in systolic blood pressure of 20 mm Hg or more, either continuously or after an initial increase). Studies have shown that HCM patients who have abnormal blood pressure responses during exercise have a higher risk of sudden cardiac death.22–24

Exercise stress echocardiography can be useful to evaluate for provoked increases in the left ventricular outflow tract gradient, which may contribute to a patient’s symptoms even if the resting left ventricular outflow tract gradient is normal. Exercise testing is preferred over pharmacologic stimulation because it can provide functional assessment of whether a patient’s clinical symptoms are truly related to hemodynamic changes due to the hypertrophied ventricle, or whether alternative mechanisms should be explored.

Cardiopulmonary stress testing can readily add prognostic value with additional measurements of functional capacity. HCM patients who cannot achieve their predicted maximal exercise value such as peak rate of oxygen consumption, ventilation efficiency, or anaerobic threshold have higher rates of morbidity and mortality.25,26 Stress testing can also be useful for risk stratification in asymptomatic patients, with one study showing that those who achieve more than 100% of their age- and sex-predicted metabolic equivalents have a low event rate.27

Ambulatory electrocardiographic monitoring in all patients at diagnosis

Ambulatory electrocardiographic monitoring for 24 to 48 hours is recommended for all HCM patients at the time of diagnosis, even if they have no symptoms. Any evidence of nonsustained ventricular tachycardia suggests a substantially higher risk of sudden cardiac death.28,29

In patients with no symptoms or history of arrhythmia, current guidelines suggest ambulatory electrocardiographic monitoring every 1 to 2 years.9,21

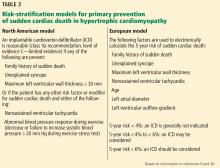

Two risk-stratification models

The North American model was the first risk-stratification tool and considers 5 risk factors.9 However, if this algorithm were strictly followed, up to 60% of HCM patients would be candidates for cardioverter-defibrillator implantation.

The European model. This concern led to the development of the HCM Risk-SCD (sudden cardiac death), a risk-stratification tool introduced in the 2014 European Society of Cardiology HCM guidelines.30 This web-based calculator estimates a patient’s 5-year risk of sudden cardiac death using a complex calculation based on 7 clinical risk factors. If a patient’s calculated 5-year risk of sudden cardiac death is 6% or higher, cardioverter-defibrillator implantation is recommended for primary prevention.

The HCM Risk-SCD calculator was validated and compared with classic risk factors alone in a retrospective cohort study in 48 HCM patients.30 Compared with the North American model, the European model results in a lower rate of cardioverter-defibrillator implantation (20% to 26%).31,32

Despite the better specificity of the European model, a large retrospective cohort analysis showed that a significant number of patients stratified as being at low risk for sudden cardiac death were ultimately found to be at high risk in clinical practice.31 Further research is needed to find the optimal risk-stratification approach in HCM patients at low to intermediate risk.

GENETIC TESTING, COUNSELING, AND FAMILY SCREENING

Genetic testing is becoming more widely available and has rapidly expanded in clinical practice. Genetic counseling must be performed alongside genetic testing and requires professionals trained to handle the clinical and social implications of genetic testing. With this in mind, genetic testing can provide a definitive means of identifying family members at risk of HCM.

Given the autosomal dominant nature of HCM, screening for HCM is recommended in all first-degree relatives of an affected patient. Genetic testing may be a means to achieve this if a pathogenic mutation has been identified in the affected patient. However, serial electrocardiographic and transthoracic echocardiographic monitoring is an acceptable alternative in those without a clear genetic mutation association or in those who do not want to undergo genetic testing. If these first-degree relatives who do not undergo genetic testing are adult athletes or adolescents, they should undergo surveillance monitoring, with echocardiography and electrocardiography, whereas adults not participating in athletics should be monitored every 5 years.9,21

As genetic counseling and testing become more widely available, more patients are being found who harbor a mutation but have no phenotypic manifestations of HCM on initial presentation. Clinical expression varies, so continued monitoring of these patients is important. Expert guidelines again recommend serial electrocardiography, transthoracic echocardiography, and clinical assessment every 5 years for adults.9

Recent data suggest that up to 40% of HCM cases are nonfamilial, ie, their inheritance is sporadic with no known family history and no sarcomeric gene mutation evident on screening.33,34 The clinical course in this subgroup seems to be more benign, with later clinical presentations (age > 40) and lower risk of major adverse cardiovascular events.

MANAGEMENT

Conservative management

Asymptomatic HCM can usually be managed with lifestyle modifications.

Avoiding high-risk physical activities is the most important modification. All HCM patients should be counseled on the risk of sudden cardiac death and advised against participating in competitive sports or intense physical activity.35 Aerobic exercise is preferable to isometric exercises such as weightlifting, which may prompt the Valsalva maneuver with worsening of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction leading to syncope. A recent study showed that moderate-intensity aerobic exercise can safely improve exercise capacity, which may ultimately improve functional status and quality of life.36

Avoiding dehydration and excessive alcohol intake are also important in maintaining adequate preload to prevent an increasing left ventricular outflow tract gradient, given the dynamic nature of the left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in HCM.

Medical management: Beta-blockers, then calcium channel blockers

Beta-blockers are the first-line therapy for symptomatic HCM related to left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. Their negative inotropic effect reduces the contractile force of the ventricle, effectively reducing the pressure gradient across the outflow tract. Reduced contractility also means that the overall myocardial workload is less, which ultimately translates to a reduced oxygen demand. With their negative chronotropic effect, beta-blockers lower the heart rate and thereby lengthen the diastolic filling phase, allowing for optimization of preload conditions to help prevent increasing the left ventricular outflow tract gradient.37,38

Beta-blockers can be titrated according to the patient’s symptoms and tolerance. Fatigue and loss of libido are among the most common side effects.

Nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers can be a second-line therapy in patients who cannot tolerate beta-blockers. Several studies have shown improvement in surrogate outcomes such as estimated left ventricular mass and QRS amplitude on electrocardiography, but currently no available data show that these drugs improve symptoms.28,39,40 They should be avoided in those with severe left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (gradient ≥ 100 mm Hg), as they can lead to critical outflow tract obstruction owing to their peripheral vasodilatory effect.

Dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers should be avoided altogether, as they produce even more peripheral vasodilation and afterload reduction than nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers.

Disopyramide, a class IA antiarrhythmic, has been shown to effectively reduce outflow gradients and relieve symptoms. However, in view of its adverse effects, it is a third-line therapy, given to those for whom beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers have failed. Its most worrisome adverse effect is QT prolongation, and the QT interval should therefore be closely monitored at the start of treatment. Anticholinergic effects are common and include dry eyes and mouth, urinary retention, and drowsiness.

Disopyramide is usually used in combination with beta-blockers for symptom control as a bridge to a planned invasive intervention.41

Use with caution

Any medication that causes afterload reduction, peripheral vasodilation, intravascular volume depletion, or positive inotropy can worsen the dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in a patient with HCM and should be avoided.

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), and nitrates must be used with extreme caution in these patients.

Diuretics. Even restrained use of diuretics can cause significant hemodynamic compromise in patients with obstructive physiology. Therefore, diuretics should be used sparingly in these patients.

Digoxin should not be used for managing atrial fibrillation in these patients, as its positive inotropic effect increases contractility and increases the left ventricular outflow tract gradient.

Norepinephrine and inotropic agents such as dobutamine and dopamine should be avoided for the same reason as digoxin. In patients with circulatory shock requiring vasopressor support, pure alpha-agonists such as phenylephrine are preferred, as they increase peripheral resistance without an inotropic effect.

Anticoagulation for atrial tachyarrhythmias

The risk of systemic thromboembolic events is significantly increased in HCM patients with atrial fibrillation or flutter, regardless of their estimated risk using conventional risk-stratification tools such as the CHADS2 score.42–44 In accordance with current American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology guidelines, we recommend anticoagulation therapy for all HCM patients with a history of atrial fibrillation or flutter. Warfarin is the preferred anticoagulant; direct oral anticoagulants can be considered, but there are currently no data on their use in HCM.9

Standard heart failure treatments

End-stage systolic heart failure is a consequence of HCM but affects only 3% to 4% of patients.45 While most randomized controlled trials of heart failure treatment have excluded HCM patients, current guidelines recommend the same evidence-based medical therapies used in other patients who have heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. This includes ACE inhibitors, ARBs, beta-blockers, and aldosterone antagonists if indicated.9,21

Heart transplant should be considered in patients with class III or IV New York Heart Association functional status despite optimization of their HCM treatment regimen. Heart transplant outcomes for HCM patients are comparable to outcomes for patients who receive a transplant for non-HCM cardiovascular disease.45,46

Septal reduction therapy

If medical therapy fails or is not tolerated in patients with severe symptoms, surgery can be considered for obstructive HCM.

Ventricular septal myectomy has been the long-standing gold standard of invasive therapy. Multiple studies have demonstrated long-term survival after myectomy to be equivalent to that in the general population and better than that of HCM patients who do not undergo this surgery.47–50 Factors that may be associated with better surgical outcomes include age younger than 50, left atrial size less than 46 mm, and resolution of atrial fibrillation during follow-up.51

Septal reduction therapy may also be considered in patients at high risk of sudden cardiac death based on a history of recurrent ventricular tachycardia or risk-stratification models as described above. Retrospective analyses have shown that surgical myectomy can markedly reduce the incidence of appropriate implantable cardioverter-defibrillator discharges and the risk of sudden cardiac death.52

Alcohol septal ablation is an alternative. This percutaneous procedure, first described in the mid-1990s, consists of injecting a small amount of alcohol into the artery supplying the septum to induce myocardial necrosis, ultimately leading to scarring and widening of the left ventricular outflow tract.53

Up to 50% of patients develop right bundle branch block after alcohol septal ablation, and the risk of complete heart block is highest in those with preexisting left bundle branch block. Nevertheless, studies have shown significant symptomatic improvement after alcohol septal ablation, with long-term survival comparable to that in the general population.53–56

Several meta-analyses compared alcohol septal ablation and septal myectomy and found that the rates of functional improvement and long-term mortality were similar.57–59 However, the less-invasive approach with alcohol septal ablation comes at the cost of a higher incidence of conduction abnormalities and higher left ventricular outflow tract gradients afterward. One meta-analysis found that alcohol septal ablation patients may have 5 times the risk of needing additional septal reduction therapy compared with their myectomy counterparts.

Current US guidelines recommend septal myectomy, performed at an experienced center, as the first-line interventional treatment, leaving alcohol septal ablation to be considered in those who have contraindications to myectomy.9 The treatment strategy should ultimately be individualized based on a patient’s comorbidities and personal preferences following informed consent.

A nationwide database study recently suggested that postmyectomy mortality rates may be as high as 5.9%,60 although earlier studies at high-volume centers showed much lower mortality rates (< 1%).50–52,61 This discrepancy highlights the critical role of expert centers in optimizing surgical management of these patients. Regardless of the approach, interventional therapies for HCM should be performed by a multidisciplinary team at a medical center able to handle the complexity of these cases.

Additional surgical procedures

A handful of other procedures may benefit specific patient subgroups.

Apical myectomy has been shown to improve functional status in patients with isolated apical hypertrophy by reducing left ventricular end-diastolic pressure and thereby allowing for improved diastolic filling.63

Mitral valve surgery may need to be considered at the time of myectomy in patients with degenerative valve disease. As in the general population, mitral valve repair is preferred to replacement if possible.

- Maron BJ. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: an important global disease. Am J Med 2004; 116(1):63–65. pmid:14706671

- Semsarian C, Ingles J, Maron MS, Maron BJ. New perspectives on the prevalence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015; 65(12):1249–1254. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.01.019

- Maron BJ, Maron MS, Semsarian C. Genetics of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy after 20 years: clinical perspectives. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012; 60(8):705–715. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2012.02.068

- Shirani J, Pick R, Roberts WC, Maron BJ. Morphology and significance of the left ventricular collagen network in young patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and sudden cardiac death. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000; 35(1):36–44. pmid:10636256

- Sherrid MV, Chu CK, Delia E, Mogtader A, Dwyer EM Jr. An echocardiographic study of the fluid mechanics of obstruction in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 1993; 22(3):816–825. pmid:8354817

- Ro R, Halpern D, Sahn DJ, et al. Vector flow mapping in obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy to assess the relationship of early systolic left ventricular flow and the mitral valve. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 64(19):1984–1995. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2014.04.090

- Kwon DH, Setser RM, Thamilarasan M, et al. Abnormal papillary muscle morphology is independently associated with increased left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Heart 2008; 94(10):1295–1301. doi:10.1136/hrt.2007.118018

- Patel P, Dhillon A, Popovic ZB, et al. Left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients without severe septal hypertrophy: implications of mitral valve and papillary muscle abnormalities assessed using cardiac magnetic resonance and echocardiography. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2015; 8(7):e003132. doi:10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.115.003132

- Gersh BJ, Maron BJ, Bonow RO, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2011; 142(6):e153-e203. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.10.020

- Elliott PM, Gimeno JR, Thaman R, et al. Historical trends in reported survival rates in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Heart 2006; 92(6):785–791. doi:10.1136/hrt.2005.068577

- Maron MS, Olivotto I, Zenovich AG, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is predominantly a disease of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. Circulation 2006; 114(21):2232–2239. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.644682

- Ho CY, Carlsen C, Thune JJ, et al. Echocardiographic strain imaging to assess early and late consequences of sarcomere mutations in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2009; 2(4):314–321. doi:10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.862128

- Wasfy MM, Weiner RB. Differentiating the athlete’s heart from hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Curr Opin Cardiol 2015; 30(5):500–505. doi:10.1097/HCO.0000000000000203

- Palka P, Lange A, Fleming AD, et al. Differences in myocardial velocity gradient measured throughout the cardiac cycle in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, athletes and patients with left ventricular hypertrophy due to hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997; 30(3):760–768. pmid:9283537

- Eriksson MJ, Sonnenberg B, Woo A, et al. Long-term outcome in patients with apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 39(4):638–645. pmid:11849863

- Rickers C, Wilke NM, Jerosch-Herold M, et al. Utility of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2005; 112(6):855–861. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.507723

- Kwon DH, Setser RM, Popovic ZB, et al. Association of myocardial fibrosis, electrocardiography and ventricular tachyarrhythmia in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a delayed contrast enhanced MRI study. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2008; 24(6):617–625. doi:10.1007/s10554-008-9292-6

- Rubinshtein R, Glockner JF, Ommen SR, et al. Characteristics and clinical significance of late gadolinium enhancement by contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Heart Fail 2010; 3(1):51–58. doi:10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.854026

- O’Hanlon R, Grasso A, Roughton M, et al. Prognostic significance of myocardial fibrosis in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010; 56(11):867–874. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.010

- Bruder O, Wagner A, Jensen CJ, et al. Myocardial scar visualized by cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging predicts major adverse events in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010; 56(11):875–887. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.007

- Authors/Task Force members, Elliott PM, Anastasakis A, Borger MA, et al. 2014 ESC guidelines on diagnosis and management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2014; 35(39):2733–2779. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehu284

- Olivotto I, Maron BJ, Montereggi A, Mazzuoli F, Dolara A, Cecchi F. Prognostic value of systemic blood pressure response during exercise in a community-based patient population with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999; 33(7):2044–2051. pmid:10362212

- Sadoul N, Prasad K, Elliott PM, Bannerjee S, Frenneaux MP, McKenna WJ. Prospective prognostic assessment of blood pressure response during exercise in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 1997; 96(9):2987–2991. pmid:9386166

- Elliott PM, Poloniecki J, Dickie S, et al. Sudden death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: identification of high risk patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000; 36(7):2212–2218. pmid:11127463

- Masri A, Pierson LM, Smedira NG, et al. Predictors of long-term outcomes in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy undergoing cardiopulmonary stress testing and echocardiography. Am Heart J 2015; 169(5):684–692.e1. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2015.02.006

- Coats CJ, Rantell K, Bartnik A, et al. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing and prognosis in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Heart Fail 2015; 8(6):1022–1031. doi:10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.002248

- Desai MY, Bhonsale A, Patel P, et al. Exercise echocardiography in asymptomatic HCM: exercise capacity, and not LV outflow tract gradient predicts long-term outcomes. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2014; 7(1):26–36. doi:10.1016/j.jcmg.2013.08.010

- Spirito P, Seidman CE, McKenna WJ, Maron BJ. The management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 1997; 336(11):775–785. doi:10.1056/NEJM199703133361107

- Wang W, Lian Z, Rowin EJ, Maron BJ, Maron MS, Link MS. Prognostic implications of nonsustained ventricular tachycardia in high-risk patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2017; 10(3)e004604. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.116.004604

- O’Mahony C, Jichi F, Pavlou M, et al. A novel clinical risk prediction model for sudden cardiac death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM risk-SCD). Eur Heart J 2014; 35(30):2010–2020. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/eht439

- Maron BJ, Casey SA, Chan RH, Garberich RF, Rowin EJ, Maron MS. Independent assessment of the European Society of Cardiology sudden death risk model for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 2015; 116(5):757–764. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.05.047

- Jahnlová D, Tomašov P, Zemánek D, Veselka J. Transatlantic differences in assessment of risk of sudden cardiac death in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol 2015; 186:3–4. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.03.207

- Ingles J, Burns C, Bagnall RD, et al. Nonfamilial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: prevalence, natural history, and clinical implications. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2017; 10(2)e001620. doi:10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.116.001620

- Ko C, Arscott P, Concannon M, et al. Genetic testing impacts the utility of prospective familial screening in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy through identification of a nonfamilial subgroup. Genet Med 2017; 20(1):69–75. doi:10.1038/gim.2017.79

- Maron BJ, Chaitman BR, Ackerman MJ, et al. Recommendations for physical activity and recreational sports participation for young patients with genetic cardiovascular diseases. Circulation 2004; 109(22):2807–2816. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000128363.85581.E1

- Saberi S, Wheeler M, Bragg-Gresham J, et al. Effect of moderate-intensity exercise training on peak oxygen consumption in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017; 317(13):1349–1357. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.2503

- Bourmayan C, Razavi A, Fournier C, et al. Effect of propranolol on left ventricular relaxation in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: an echographic study. Am Heart J 1985; 109(6):1311–1316. pmid:4039882

- Spoladore R, Maron MS, D’Amato R, Camici PG, Olivotto I. Pharmacological treatment options for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: high time for evidence. Eur Heart J 2012; 33(14):1724–1733. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehs150

- Choudhury L, Elliott P, Rimoldi O, et al. Transmural myocardial blood flow distribution in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and effect of treatment. Basic Res Cardiol 1999; 94(1):49–59. pmid:10097830

- Kaltenbach M, Hopf R, Kober G, Bussmann WD, Keller M, Petersen Y. Treatment of hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy with verapamil. Br Heart J 1979; 42(1):35–42. doi:10.1136/hrt.42.1.35

- Sherrid MV, Shetty A, Winson G, et al. Treatment of obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy symptoms and gradient resistant to first-line therapy with beta-blockade or verapamil. Circ Heart Fail 2013; 6(4):694–702. doi:10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.000122

- Guttmann OP, Rahman MS, O’Mahony C, Anastasakis A, Elliott PM. Atrial fibrillation and thromboembolism in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: systematic review. Heart 2014; 100(6):465–472. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2013-304276

- Olivotto I, Cecchi F, Casey SA, Dolara A, Traverse JH, Maron BJ. Impact of atrial fibrillation on the clinical course of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2001; 104(21):2517–2524. pmid:11714644

- Maron BJ, Olivotto I, Spirito P, et al. Epidemiology of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy-related death: revisited in a large non-referral-based patient population. Circulation 2000; 102(8):858–864. pmid:10952953

- Harris KM, Spirito P, Maron MS, et al. Prevalence, clinical profile, and significance of left ventricular remodeling in the end-stage phase of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2006; 114(3):216-225. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.583500

- Maron MS, Kalsmith BM, Udelson JE, Li W, DeNofrio D. Survival after cardiac transplantation in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Heart Fail 2010; 3(5):574–579. doi:10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.922872

- Smedira NG, Lytle BW, Lever HM, et al. Current effectiveness and risks of isolated septal myectomy for hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Ann Thorac Surg 2008; 85(1):127–133. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.07.063

- Robbins RC, Stinson EB. Long-term results of left ventricular myotomy and myectomy for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1996; 111(3):586–594. pmid:8601973

- Heric B, Lytle BW, Miller DP, Rosenkranz ER, Lever HM, Cosgrove DM. Surgical management of hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Early and late results. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1995; 110(1):195–208. pmid:7609544

- Ommen SR, Maron BJ, Olivotto I, et al. Long-term effects of surgical septal myectomy on survival in patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005; 46(3):470–476. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.090

- Desai MY, Bhonsale A, Smedira NG, et al. Predictors of long-term outcomes in symptomatic hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy patients undergoing surgical relief of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. Circulation 2013; 128(3):209–216. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000849

- McLeod CJ, Ommen SR, Ackerman MJ, et al. Surgical septal myectomy decreases the risk for appropriate implantable cardioverter defibrillator discharge in obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J 2007; 28(21):2583–2588. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehm117

- Veselka J, Tomasov P, Zemanek D. Long-term effects of varying alcohol dosing in percutaneous septal ablation for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a randomized study with a follow-up up to 11 years. Can J Cardiol 2011; 27(6):763–767. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2011.09.001

- Veselka J, Jensen MK, Liebregts M, et al. Low procedure-related mortality achieved with alcohol septal ablation in European patients. Int J Cardiol 2016; 209:194–195. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.02.077

- Veselka J, Krejci J, Tomašov P, Zemánek D. Long-term survival after alcohol septal ablation for hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy: a comparison with general population. Eur Heart J 2014; 35(30):2040–2045. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/eht495

- Sorajja P, Ommen SR, Holmes DR Jr, et al. Survival after alcohol septal ablation for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2012; 126(20):2374–2380. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.076257

- Agarwal S, Tuzcu EM, Desai MY, et al. Updated meta-analysis of septal alcohol ablation versus myectomy for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010; 55(8):823–834. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2009.09.047

- Leonardi RA, Kransdorf EP, Simel DL, Wang A. Meta-analyses of septal reduction therapies for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: comparative rates of overall mortality and sudden cardiac death after treatment. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2010; 3(2):97–104. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.109.916676

- Liebregts M, Vriesendorp PA, Mahmoodi BK, Schinkel AF, Michels M, ten Berg JM. A systematic review and meta-analysis of long-term outcomes after septal reduction therapy in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. JACC Heart Fail 2015; 3(11):896–905. doi:10.1016/j.jchf.2015.06.011

- Panaich SS, Badheka AO, Chothani A, et al. Results of ventricular septal myectomy and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (from Nationwide Inpatient Sample [1998-2010]). Am J Cardiol 2014; 114(9):1390–1395. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.07.075

- Maron BJ, Dearani JA, Ommen SR, et al. Low operative mortality achieved with surgical septal myectomy: role of dedicated hypertrophic cardiomyopathy centers in the management of dynamic subaortic obstruction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015; 66(11):1307–1308. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.06.1333

- Kwon DH, Smedira NG, Thamilarasan M, Lytle BW, Lever H, Desai MY. Characteristics and surgical outcomes of symptomatic patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with abnormal papillary muscle morphology undergoing papillary muscle reorientation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2010; 140(2):317–324. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.10.045

- Schaff HV, Brown ML, Dearani JA, et al. Apical myectomy: a new surgical technique for management of severely symptomatic patients with apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2010; 139(3):634–640. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.07.079

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a complex disease. Most people who carry the mutations that cause it are never affected at any point in their life, but some are affected at a young age. And in rare but tragic cases, some die suddenly while competing in sports. With such a wide range of phenotypic expressions, a single therapy does not fit all.

HCM is more common than once thought. Since the discovery of its genetic predisposition in 1960, it has come to be recognized as the most common heritable cardiovascular disease.1 Although earlier epidemiologic studies had estimated a prevalence of 1 in 500 (0.2%) of the general population, genetic testing and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) now show that up to 1 in 200 (0.5%) of all people may be affected.1,2 Its prevalence is significant in all ethnic groups.

This review outlines our expanding knowledge of the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and clinical management of HCM.

A PLETHORA OF MUTATIONS IN CARDIAC SARCOMERIC GENES

The genetic differences within HCM result in varying degrees and locations of left ventricular hypertrophy. Any segment of the ventricle can be involved, although HCM is classically asymmetric and mainly involves the septum (Figure 1). A variant form of HCM involves the apex of the heart (Figure 2).

LEFT VENTRICULAR OUTFLOW TRACT OBSTRUCTION

Only in the last decade has the significance of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in HCM been truly appreciated. The degree of obstruction in HCM is dynamic, as opposed to the fixed obstruction in patients with aortic stenosis or congenital subvalvular membranes. Therefore, in HCM, exercise or drugs (eg, dobutamine) that increase cardiac contractility increase the obstruction, as do maneuvers or drugs (the Valsalva maneuver, nitrates) that reduce filling of the left ventricle.

A less common source of dynamic obstruction is the papillary muscles (Figure 4). Hypertrophy of the papillary muscles can result in obstruction by these muscles themselves, which is visible on echocardiography. Anatomic variations include anteroapical displacement or bifid papillary muscles, and these variants can be associated with dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, even with no evidence of septal thickening (Figure 5).7,8 Recognizing this patient subset has important implications for management, as discussed below.

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

The clinical presentation varies

Even if patients harbor the same genetic variant, the clinical presentation can differ widely. Although the most feared presentation is sudden cardiac death, particularly in young athletes, most patients have no symptoms and can anticipate a normal life expectancy. The annual incidence of sudden cardiac death in all HCM patients is estimated at less than 1%.10 Sudden cardiac death in HCM patients is most often due to ventricular tachyarrhythmias and most often occurs in asymptomatic patients under age 35.

Physical findings are nonspecific

It can be difficult to distinguish the murmur of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in HCM from a murmur related to aortic stenosis by auscultation alone. The simplest clinical method for telling them apart involves the Valsalva maneuver: bearing down creates a positive intrathoracic pressure and limits venous return, thus decreasing intracardiac filling pressure. This in turn results in less separation between the mitral valve and the ventricular septum in HCM, which increases obstruction and therefore makes the murmur louder. In contrast, in patients with fixed obstruction due to aortic stenosis, the murmur will decrease in intensity owing to the reduced flow associated with reduced preload.

Laboratory testing for phenocopies of HCM

A metabolic panel will show derangements in liver function and glucose levels in patients with glycogen storage disorders such as Pompe disease.

Serum creatinine. Renal dysfunction will be seen in patients with Fabry disease or amyloidosis.

Creatine kinase may be elevated in patients with Danon disease.

Electrocardiographic findings are common

More than 90% of HCM patients have electrocardiographic abnormalities. Although the findings can vary widely, common manifestations include:

- Left ventricular hypertrophy

- A pseudoinfarct pattern with Q waves in the anterolateral leads

- Repolarization changes such as T-wave inversions and horizontal or down-sloping ST segments.

Apical HCM, seen mainly in Asian populations, often presents with giant T-wave inversion (> 10 mm) in the anterolateral leads, most prominent in V4, V5, and V6.

Notably, the degree of electrocardiographic abnormalities does not correlate with the severity or pattern of hypertrophy.9 Electrocardiography lacks specificity for definitive diagnosis, and further diagnostic testing should therefore be pursued.

Echocardiography: Initial imaging test

Transthoracic echocardiography is the initial imaging test in patients with suspected HCM, allowing for cost-effective quantitative and qualitative assessment of left ventricular morphology and function. Left ventricular hypertrophy is considered pathologic if wall thickness is 15 mm or greater without a known cause. Transthoracic echocardiography also allows for evaluation of left atrial volume and mitral valve anatomy and function.

Speckle tracking imaging is an advanced echocardiographic technique that measures strain. Its major advantage is in identifying early abnormalities in genotype-positive, phenotype-negative HCM patients, ie, people who harbor mutations but who have no clinical symptoms or signs of HCM, potentially allowing for modification of the natural history of HCM.12 Strain imaging can also differentiate between physiologic hypertrophy (“athlete’s heart”) and hypertension and HCM.13,14

The utility of echocardiography in HCM is heavily influenced by the sonographer’s experience in obtaining adequate acoustic windows. This may be more difficult in obese patients, patients with advanced obstructive lung disease or pleural effusions, and women with breast implants.

Magnetic resonance imaging

MRI has an emerging role in both diagnosing and predicting risk in HCM, and is routinely done as an adjunct to transthoracic echocardiography on initial diagnosis in our tertiary referral center. It is particularly useful in patients suspected of having apical hypertrophy (Figure 2), in whom the diagnosis may be missed in up to 10% on transthoracic echocardiography alone.15 MRI can also enhance the assessment of left ventricular hypertrophy and has been shown to improve the diagnostic classification of HCM.16 It is the best way to assess myocardial tissue abnormalities, and late gadolinium enhancement to detect interstitial fibrosis can be used for further prognostication. While historically the primary role of MRI in HCM has been in phenotype classification, there is currently much interest in its role in risk stratification of HCM patients for ICD implantation.

MRI with late gadolinium enhancement provides insight into the location, pattern, and extent of myocardial fibrosis; the extent of fibrosis has been shown to be a strong independent predictor of poor outcomes, including sudden cardiac death.17–20 However, late gadolinium enhancement can be technically challenging, as variations in the timing of postcontrast imaging, sequences for measuring late gadolinium enhancement, or detection thresholds can result in widely variable image quality. Cardiac MRI should therefore be performed at an experienced center with standardized imaging protocols in place.

Current guidelines recommend considering cardiac MRI if a patient’s risk of sudden cardiac death remains inconclusive after conventional risk stratification, as discussed below.9,21

Stress testing for risk stratification

Exercise stress electrocardiography. Treadmill exercise stress testing with electrocardiography and hemodynamic monitoring was one of the first tools used for risk stratification in HCM.

Although systolic blood pressure normally increases by at least 20 mm Hg with exercise, one-quarter of HCM patients have either a blunted response (failure of systolic blood pressure to increase by at least 20 mm Hg) or a hypotensive response (a drop in systolic blood pressure of 20 mm Hg or more, either continuously or after an initial increase). Studies have shown that HCM patients who have abnormal blood pressure responses during exercise have a higher risk of sudden cardiac death.22–24

Exercise stress echocardiography can be useful to evaluate for provoked increases in the left ventricular outflow tract gradient, which may contribute to a patient’s symptoms even if the resting left ventricular outflow tract gradient is normal. Exercise testing is preferred over pharmacologic stimulation because it can provide functional assessment of whether a patient’s clinical symptoms are truly related to hemodynamic changes due to the hypertrophied ventricle, or whether alternative mechanisms should be explored.

Cardiopulmonary stress testing can readily add prognostic value with additional measurements of functional capacity. HCM patients who cannot achieve their predicted maximal exercise value such as peak rate of oxygen consumption, ventilation efficiency, or anaerobic threshold have higher rates of morbidity and mortality.25,26 Stress testing can also be useful for risk stratification in asymptomatic patients, with one study showing that those who achieve more than 100% of their age- and sex-predicted metabolic equivalents have a low event rate.27

Ambulatory electrocardiographic monitoring in all patients at diagnosis

Ambulatory electrocardiographic monitoring for 24 to 48 hours is recommended for all HCM patients at the time of diagnosis, even if they have no symptoms. Any evidence of nonsustained ventricular tachycardia suggests a substantially higher risk of sudden cardiac death.28,29

In patients with no symptoms or history of arrhythmia, current guidelines suggest ambulatory electrocardiographic monitoring every 1 to 2 years.9,21

Two risk-stratification models

The North American model was the first risk-stratification tool and considers 5 risk factors.9 However, if this algorithm were strictly followed, up to 60% of HCM patients would be candidates for cardioverter-defibrillator implantation.

The European model. This concern led to the development of the HCM Risk-SCD (sudden cardiac death), a risk-stratification tool introduced in the 2014 European Society of Cardiology HCM guidelines.30 This web-based calculator estimates a patient’s 5-year risk of sudden cardiac death using a complex calculation based on 7 clinical risk factors. If a patient’s calculated 5-year risk of sudden cardiac death is 6% or higher, cardioverter-defibrillator implantation is recommended for primary prevention.

The HCM Risk-SCD calculator was validated and compared with classic risk factors alone in a retrospective cohort study in 48 HCM patients.30 Compared with the North American model, the European model results in a lower rate of cardioverter-defibrillator implantation (20% to 26%).31,32

Despite the better specificity of the European model, a large retrospective cohort analysis showed that a significant number of patients stratified as being at low risk for sudden cardiac death were ultimately found to be at high risk in clinical practice.31 Further research is needed to find the optimal risk-stratification approach in HCM patients at low to intermediate risk.

GENETIC TESTING, COUNSELING, AND FAMILY SCREENING

Genetic testing is becoming more widely available and has rapidly expanded in clinical practice. Genetic counseling must be performed alongside genetic testing and requires professionals trained to handle the clinical and social implications of genetic testing. With this in mind, genetic testing can provide a definitive means of identifying family members at risk of HCM.

Given the autosomal dominant nature of HCM, screening for HCM is recommended in all first-degree relatives of an affected patient. Genetic testing may be a means to achieve this if a pathogenic mutation has been identified in the affected patient. However, serial electrocardiographic and transthoracic echocardiographic monitoring is an acceptable alternative in those without a clear genetic mutation association or in those who do not want to undergo genetic testing. If these first-degree relatives who do not undergo genetic testing are adult athletes or adolescents, they should undergo surveillance monitoring, with echocardiography and electrocardiography, whereas adults not participating in athletics should be monitored every 5 years.9,21

As genetic counseling and testing become more widely available, more patients are being found who harbor a mutation but have no phenotypic manifestations of HCM on initial presentation. Clinical expression varies, so continued monitoring of these patients is important. Expert guidelines again recommend serial electrocardiography, transthoracic echocardiography, and clinical assessment every 5 years for adults.9

Recent data suggest that up to 40% of HCM cases are nonfamilial, ie, their inheritance is sporadic with no known family history and no sarcomeric gene mutation evident on screening.33,34 The clinical course in this subgroup seems to be more benign, with later clinical presentations (age > 40) and lower risk of major adverse cardiovascular events.

MANAGEMENT

Conservative management

Asymptomatic HCM can usually be managed with lifestyle modifications.

Avoiding high-risk physical activities is the most important modification. All HCM patients should be counseled on the risk of sudden cardiac death and advised against participating in competitive sports or intense physical activity.35 Aerobic exercise is preferable to isometric exercises such as weightlifting, which may prompt the Valsalva maneuver with worsening of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction leading to syncope. A recent study showed that moderate-intensity aerobic exercise can safely improve exercise capacity, which may ultimately improve functional status and quality of life.36

Avoiding dehydration and excessive alcohol intake are also important in maintaining adequate preload to prevent an increasing left ventricular outflow tract gradient, given the dynamic nature of the left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in HCM.

Medical management: Beta-blockers, then calcium channel blockers

Beta-blockers are the first-line therapy for symptomatic HCM related to left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. Their negative inotropic effect reduces the contractile force of the ventricle, effectively reducing the pressure gradient across the outflow tract. Reduced contractility also means that the overall myocardial workload is less, which ultimately translates to a reduced oxygen demand. With their negative chronotropic effect, beta-blockers lower the heart rate and thereby lengthen the diastolic filling phase, allowing for optimization of preload conditions to help prevent increasing the left ventricular outflow tract gradient.37,38

Beta-blockers can be titrated according to the patient’s symptoms and tolerance. Fatigue and loss of libido are among the most common side effects.

Nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers can be a second-line therapy in patients who cannot tolerate beta-blockers. Several studies have shown improvement in surrogate outcomes such as estimated left ventricular mass and QRS amplitude on electrocardiography, but currently no available data show that these drugs improve symptoms.28,39,40 They should be avoided in those with severe left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (gradient ≥ 100 mm Hg), as they can lead to critical outflow tract obstruction owing to their peripheral vasodilatory effect.

Dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers should be avoided altogether, as they produce even more peripheral vasodilation and afterload reduction than nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers.

Disopyramide, a class IA antiarrhythmic, has been shown to effectively reduce outflow gradients and relieve symptoms. However, in view of its adverse effects, it is a third-line therapy, given to those for whom beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers have failed. Its most worrisome adverse effect is QT prolongation, and the QT interval should therefore be closely monitored at the start of treatment. Anticholinergic effects are common and include dry eyes and mouth, urinary retention, and drowsiness.

Disopyramide is usually used in combination with beta-blockers for symptom control as a bridge to a planned invasive intervention.41

Use with caution

Any medication that causes afterload reduction, peripheral vasodilation, intravascular volume depletion, or positive inotropy can worsen the dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in a patient with HCM and should be avoided.

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), and nitrates must be used with extreme caution in these patients.

Diuretics. Even restrained use of diuretics can cause significant hemodynamic compromise in patients with obstructive physiology. Therefore, diuretics should be used sparingly in these patients.

Digoxin should not be used for managing atrial fibrillation in these patients, as its positive inotropic effect increases contractility and increases the left ventricular outflow tract gradient.

Norepinephrine and inotropic agents such as dobutamine and dopamine should be avoided for the same reason as digoxin. In patients with circulatory shock requiring vasopressor support, pure alpha-agonists such as phenylephrine are preferred, as they increase peripheral resistance without an inotropic effect.

Anticoagulation for atrial tachyarrhythmias

The risk of systemic thromboembolic events is significantly increased in HCM patients with atrial fibrillation or flutter, regardless of their estimated risk using conventional risk-stratification tools such as the CHADS2 score.42–44 In accordance with current American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology guidelines, we recommend anticoagulation therapy for all HCM patients with a history of atrial fibrillation or flutter. Warfarin is the preferred anticoagulant; direct oral anticoagulants can be considered, but there are currently no data on their use in HCM.9

Standard heart failure treatments

End-stage systolic heart failure is a consequence of HCM but affects only 3% to 4% of patients.45 While most randomized controlled trials of heart failure treatment have excluded HCM patients, current guidelines recommend the same evidence-based medical therapies used in other patients who have heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. This includes ACE inhibitors, ARBs, beta-blockers, and aldosterone antagonists if indicated.9,21

Heart transplant should be considered in patients with class III or IV New York Heart Association functional status despite optimization of their HCM treatment regimen. Heart transplant outcomes for HCM patients are comparable to outcomes for patients who receive a transplant for non-HCM cardiovascular disease.45,46

Septal reduction therapy

If medical therapy fails or is not tolerated in patients with severe symptoms, surgery can be considered for obstructive HCM.

Ventricular septal myectomy has been the long-standing gold standard of invasive therapy. Multiple studies have demonstrated long-term survival after myectomy to be equivalent to that in the general population and better than that of HCM patients who do not undergo this surgery.47–50 Factors that may be associated with better surgical outcomes include age younger than 50, left atrial size less than 46 mm, and resolution of atrial fibrillation during follow-up.51

Septal reduction therapy may also be considered in patients at high risk of sudden cardiac death based on a history of recurrent ventricular tachycardia or risk-stratification models as described above. Retrospective analyses have shown that surgical myectomy can markedly reduce the incidence of appropriate implantable cardioverter-defibrillator discharges and the risk of sudden cardiac death.52

Alcohol septal ablation is an alternative. This percutaneous procedure, first described in the mid-1990s, consists of injecting a small amount of alcohol into the artery supplying the septum to induce myocardial necrosis, ultimately leading to scarring and widening of the left ventricular outflow tract.53

Up to 50% of patients develop right bundle branch block after alcohol septal ablation, and the risk of complete heart block is highest in those with preexisting left bundle branch block. Nevertheless, studies have shown significant symptomatic improvement after alcohol septal ablation, with long-term survival comparable to that in the general population.53–56

Several meta-analyses compared alcohol septal ablation and septal myectomy and found that the rates of functional improvement and long-term mortality were similar.57–59 However, the less-invasive approach with alcohol septal ablation comes at the cost of a higher incidence of conduction abnormalities and higher left ventricular outflow tract gradients afterward. One meta-analysis found that alcohol septal ablation patients may have 5 times the risk of needing additional septal reduction therapy compared with their myectomy counterparts.

Current US guidelines recommend septal myectomy, performed at an experienced center, as the first-line interventional treatment, leaving alcohol septal ablation to be considered in those who have contraindications to myectomy.9 The treatment strategy should ultimately be individualized based on a patient’s comorbidities and personal preferences following informed consent.

A nationwide database study recently suggested that postmyectomy mortality rates may be as high as 5.9%,60 although earlier studies at high-volume centers showed much lower mortality rates (< 1%).50–52,61 This discrepancy highlights the critical role of expert centers in optimizing surgical management of these patients. Regardless of the approach, interventional therapies for HCM should be performed by a multidisciplinary team at a medical center able to handle the complexity of these cases.

Additional surgical procedures

A handful of other procedures may benefit specific patient subgroups.

Apical myectomy has been shown to improve functional status in patients with isolated apical hypertrophy by reducing left ventricular end-diastolic pressure and thereby allowing for improved diastolic filling.63

Mitral valve surgery may need to be considered at the time of myectomy in patients with degenerative valve disease. As in the general population, mitral valve repair is preferred to replacement if possible.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a complex disease. Most people who carry the mutations that cause it are never affected at any point in their life, but some are affected at a young age. And in rare but tragic cases, some die suddenly while competing in sports. With such a wide range of phenotypic expressions, a single therapy does not fit all.

HCM is more common than once thought. Since the discovery of its genetic predisposition in 1960, it has come to be recognized as the most common heritable cardiovascular disease.1 Although earlier epidemiologic studies had estimated a prevalence of 1 in 500 (0.2%) of the general population, genetic testing and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) now show that up to 1 in 200 (0.5%) of all people may be affected.1,2 Its prevalence is significant in all ethnic groups.

This review outlines our expanding knowledge of the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and clinical management of HCM.

A PLETHORA OF MUTATIONS IN CARDIAC SARCOMERIC GENES

The genetic differences within HCM result in varying degrees and locations of left ventricular hypertrophy. Any segment of the ventricle can be involved, although HCM is classically asymmetric and mainly involves the septum (Figure 1). A variant form of HCM involves the apex of the heart (Figure 2).

LEFT VENTRICULAR OUTFLOW TRACT OBSTRUCTION

Only in the last decade has the significance of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in HCM been truly appreciated. The degree of obstruction in HCM is dynamic, as opposed to the fixed obstruction in patients with aortic stenosis or congenital subvalvular membranes. Therefore, in HCM, exercise or drugs (eg, dobutamine) that increase cardiac contractility increase the obstruction, as do maneuvers or drugs (the Valsalva maneuver, nitrates) that reduce filling of the left ventricle.

A less common source of dynamic obstruction is the papillary muscles (Figure 4). Hypertrophy of the papillary muscles can result in obstruction by these muscles themselves, which is visible on echocardiography. Anatomic variations include anteroapical displacement or bifid papillary muscles, and these variants can be associated with dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, even with no evidence of septal thickening (Figure 5).7,8 Recognizing this patient subset has important implications for management, as discussed below.

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

The clinical presentation varies

Even if patients harbor the same genetic variant, the clinical presentation can differ widely. Although the most feared presentation is sudden cardiac death, particularly in young athletes, most patients have no symptoms and can anticipate a normal life expectancy. The annual incidence of sudden cardiac death in all HCM patients is estimated at less than 1%.10 Sudden cardiac death in HCM patients is most often due to ventricular tachyarrhythmias and most often occurs in asymptomatic patients under age 35.

Physical findings are nonspecific

It can be difficult to distinguish the murmur of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in HCM from a murmur related to aortic stenosis by auscultation alone. The simplest clinical method for telling them apart involves the Valsalva maneuver: bearing down creates a positive intrathoracic pressure and limits venous return, thus decreasing intracardiac filling pressure. This in turn results in less separation between the mitral valve and the ventricular septum in HCM, which increases obstruction and therefore makes the murmur louder. In contrast, in patients with fixed obstruction due to aortic stenosis, the murmur will decrease in intensity owing to the reduced flow associated with reduced preload.

Laboratory testing for phenocopies of HCM

A metabolic panel will show derangements in liver function and glucose levels in patients with glycogen storage disorders such as Pompe disease.

Serum creatinine. Renal dysfunction will be seen in patients with Fabry disease or amyloidosis.

Creatine kinase may be elevated in patients with Danon disease.

Electrocardiographic findings are common

More than 90% of HCM patients have electrocardiographic abnormalities. Although the findings can vary widely, common manifestations include:

- Left ventricular hypertrophy

- A pseudoinfarct pattern with Q waves in the anterolateral leads

- Repolarization changes such as T-wave inversions and horizontal or down-sloping ST segments.

Apical HCM, seen mainly in Asian populations, often presents with giant T-wave inversion (> 10 mm) in the anterolateral leads, most prominent in V4, V5, and V6.

Notably, the degree of electrocardiographic abnormalities does not correlate with the severity or pattern of hypertrophy.9 Electrocardiography lacks specificity for definitive diagnosis, and further diagnostic testing should therefore be pursued.

Echocardiography: Initial imaging test

Transthoracic echocardiography is the initial imaging test in patients with suspected HCM, allowing for cost-effective quantitative and qualitative assessment of left ventricular morphology and function. Left ventricular hypertrophy is considered pathologic if wall thickness is 15 mm or greater without a known cause. Transthoracic echocardiography also allows for evaluation of left atrial volume and mitral valve anatomy and function.

Speckle tracking imaging is an advanced echocardiographic technique that measures strain. Its major advantage is in identifying early abnormalities in genotype-positive, phenotype-negative HCM patients, ie, people who harbor mutations but who have no clinical symptoms or signs of HCM, potentially allowing for modification of the natural history of HCM.12 Strain imaging can also differentiate between physiologic hypertrophy (“athlete’s heart”) and hypertension and HCM.13,14

The utility of echocardiography in HCM is heavily influenced by the sonographer’s experience in obtaining adequate acoustic windows. This may be more difficult in obese patients, patients with advanced obstructive lung disease or pleural effusions, and women with breast implants.

Magnetic resonance imaging

MRI has an emerging role in both diagnosing and predicting risk in HCM, and is routinely done as an adjunct to transthoracic echocardiography on initial diagnosis in our tertiary referral center. It is particularly useful in patients suspected of having apical hypertrophy (Figure 2), in whom the diagnosis may be missed in up to 10% on transthoracic echocardiography alone.15 MRI can also enhance the assessment of left ventricular hypertrophy and has been shown to improve the diagnostic classification of HCM.16 It is the best way to assess myocardial tissue abnormalities, and late gadolinium enhancement to detect interstitial fibrosis can be used for further prognostication. While historically the primary role of MRI in HCM has been in phenotype classification, there is currently much interest in its role in risk stratification of HCM patients for ICD implantation.

MRI with late gadolinium enhancement provides insight into the location, pattern, and extent of myocardial fibrosis; the extent of fibrosis has been shown to be a strong independent predictor of poor outcomes, including sudden cardiac death.17–20 However, late gadolinium enhancement can be technically challenging, as variations in the timing of postcontrast imaging, sequences for measuring late gadolinium enhancement, or detection thresholds can result in widely variable image quality. Cardiac MRI should therefore be performed at an experienced center with standardized imaging protocols in place.

Current guidelines recommend considering cardiac MRI if a patient’s risk of sudden cardiac death remains inconclusive after conventional risk stratification, as discussed below.9,21

Stress testing for risk stratification

Exercise stress electrocardiography. Treadmill exercise stress testing with electrocardiography and hemodynamic monitoring was one of the first tools used for risk stratification in HCM.

Although systolic blood pressure normally increases by at least 20 mm Hg with exercise, one-quarter of HCM patients have either a blunted response (failure of systolic blood pressure to increase by at least 20 mm Hg) or a hypotensive response (a drop in systolic blood pressure of 20 mm Hg or more, either continuously or after an initial increase). Studies have shown that HCM patients who have abnormal blood pressure responses during exercise have a higher risk of sudden cardiac death.22–24

Exercise stress echocardiography can be useful to evaluate for provoked increases in the left ventricular outflow tract gradient, which may contribute to a patient’s symptoms even if the resting left ventricular outflow tract gradient is normal. Exercise testing is preferred over pharmacologic stimulation because it can provide functional assessment of whether a patient’s clinical symptoms are truly related to hemodynamic changes due to the hypertrophied ventricle, or whether alternative mechanisms should be explored.

Cardiopulmonary stress testing can readily add prognostic value with additional measurements of functional capacity. HCM patients who cannot achieve their predicted maximal exercise value such as peak rate of oxygen consumption, ventilation efficiency, or anaerobic threshold have higher rates of morbidity and mortality.25,26 Stress testing can also be useful for risk stratification in asymptomatic patients, with one study showing that those who achieve more than 100% of their age- and sex-predicted metabolic equivalents have a low event rate.27

Ambulatory electrocardiographic monitoring in all patients at diagnosis

Ambulatory electrocardiographic monitoring for 24 to 48 hours is recommended for all HCM patients at the time of diagnosis, even if they have no symptoms. Any evidence of nonsustained ventricular tachycardia suggests a substantially higher risk of sudden cardiac death.28,29

In patients with no symptoms or history of arrhythmia, current guidelines suggest ambulatory electrocardiographic monitoring every 1 to 2 years.9,21

Two risk-stratification models

The North American model was the first risk-stratification tool and considers 5 risk factors.9 However, if this algorithm were strictly followed, up to 60% of HCM patients would be candidates for cardioverter-defibrillator implantation.

The European model. This concern led to the development of the HCM Risk-SCD (sudden cardiac death), a risk-stratification tool introduced in the 2014 European Society of Cardiology HCM guidelines.30 This web-based calculator estimates a patient’s 5-year risk of sudden cardiac death using a complex calculation based on 7 clinical risk factors. If a patient’s calculated 5-year risk of sudden cardiac death is 6% or higher, cardioverter-defibrillator implantation is recommended for primary prevention.

The HCM Risk-SCD calculator was validated and compared with classic risk factors alone in a retrospective cohort study in 48 HCM patients.30 Compared with the North American model, the European model results in a lower rate of cardioverter-defibrillator implantation (20% to 26%).31,32

Despite the better specificity of the European model, a large retrospective cohort analysis showed that a significant number of patients stratified as being at low risk for sudden cardiac death were ultimately found to be at high risk in clinical practice.31 Further research is needed to find the optimal risk-stratification approach in HCM patients at low to intermediate risk.

GENETIC TESTING, COUNSELING, AND FAMILY SCREENING

Genetic testing is becoming more widely available and has rapidly expanded in clinical practice. Genetic counseling must be performed alongside genetic testing and requires professionals trained to handle the clinical and social implications of genetic testing. With this in mind, genetic testing can provide a definitive means of identifying family members at risk of HCM.

Given the autosomal dominant nature of HCM, screening for HCM is recommended in all first-degree relatives of an affected patient. Genetic testing may be a means to achieve this if a pathogenic mutation has been identified in the affected patient. However, serial electrocardiographic and transthoracic echocardiographic monitoring is an acceptable alternative in those without a clear genetic mutation association or in those who do not want to undergo genetic testing. If these first-degree relatives who do not undergo genetic testing are adult athletes or adolescents, they should undergo surveillance monitoring, with echocardiography and electrocardiography, whereas adults not participating in athletics should be monitored every 5 years.9,21

As genetic counseling and testing become more widely available, more patients are being found who harbor a mutation but have no phenotypic manifestations of HCM on initial presentation. Clinical expression varies, so continued monitoring of these patients is important. Expert guidelines again recommend serial electrocardiography, transthoracic echocardiography, and clinical assessment every 5 years for adults.9

Recent data suggest that up to 40% of HCM cases are nonfamilial, ie, their inheritance is sporadic with no known family history and no sarcomeric gene mutation evident on screening.33,34 The clinical course in this subgroup seems to be more benign, with later clinical presentations (age > 40) and lower risk of major adverse cardiovascular events.

MANAGEMENT

Conservative management

Asymptomatic HCM can usually be managed with lifestyle modifications.

Avoiding high-risk physical activities is the most important modification. All HCM patients should be counseled on the risk of sudden cardiac death and advised against participating in competitive sports or intense physical activity.35 Aerobic exercise is preferable to isometric exercises such as weightlifting, which may prompt the Valsalva maneuver with worsening of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction leading to syncope. A recent study showed that moderate-intensity aerobic exercise can safely improve exercise capacity, which may ultimately improve functional status and quality of life.36

Avoiding dehydration and excessive alcohol intake are also important in maintaining adequate preload to prevent an increasing left ventricular outflow tract gradient, given the dynamic nature of the left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in HCM.

Medical management: Beta-blockers, then calcium channel blockers

Beta-blockers are the first-line therapy for symptomatic HCM related to left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. Their negative inotropic effect reduces the contractile force of the ventricle, effectively reducing the pressure gradient across the outflow tract. Reduced contractility also means that the overall myocardial workload is less, which ultimately translates to a reduced oxygen demand. With their negative chronotropic effect, beta-blockers lower the heart rate and thereby lengthen the diastolic filling phase, allowing for optimization of preload conditions to help prevent increasing the left ventricular outflow tract gradient.37,38

Beta-blockers can be titrated according to the patient’s symptoms and tolerance. Fatigue and loss of libido are among the most common side effects.

Nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers can be a second-line therapy in patients who cannot tolerate beta-blockers. Several studies have shown improvement in surrogate outcomes such as estimated left ventricular mass and QRS amplitude on electrocardiography, but currently no available data show that these drugs improve symptoms.28,39,40 They should be avoided in those with severe left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (gradient ≥ 100 mm Hg), as they can lead to critical outflow tract obstruction owing to their peripheral vasodilatory effect.

Dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers should be avoided altogether, as they produce even more peripheral vasodilation and afterload reduction than nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers.

Disopyramide, a class IA antiarrhythmic, has been shown to effectively reduce outflow gradients and relieve symptoms. However, in view of its adverse effects, it is a third-line therapy, given to those for whom beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers have failed. Its most worrisome adverse effect is QT prolongation, and the QT interval should therefore be closely monitored at the start of treatment. Anticholinergic effects are common and include dry eyes and mouth, urinary retention, and drowsiness.

Disopyramide is usually used in combination with beta-blockers for symptom control as a bridge to a planned invasive intervention.41

Use with caution

Any medication that causes afterload reduction, peripheral vasodilation, intravascular volume depletion, or positive inotropy can worsen the dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in a patient with HCM and should be avoided.

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), and nitrates must be used with extreme caution in these patients.

Diuretics. Even restrained use of diuretics can cause significant hemodynamic compromise in patients with obstructive physiology. Therefore, diuretics should be used sparingly in these patients.

Digoxin should not be used for managing atrial fibrillation in these patients, as its positive inotropic effect increases contractility and increases the left ventricular outflow tract gradient.

Norepinephrine and inotropic agents such as dobutamine and dopamine should be avoided for the same reason as digoxin. In patients with circulatory shock requiring vasopressor support, pure alpha-agonists such as phenylephrine are preferred, as they increase peripheral resistance without an inotropic effect.

Anticoagulation for atrial tachyarrhythmias