User login

Autoimmune Progesterone Dermatitis

To the Editor:

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis (APD) is a rare dermatologic condition that can be challenging to diagnose. The associated skin lesions are not only variable in physical presentation but also in the timing of the outbreak. The skin disorder stems from an internal reaction to elevated levels of progesterone during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis can be difficult to detect; although the typical menstrual cycle is 28 days, many women have longer or shorter hormonal phases, leading to cyclical irregularity that can cause the lesions to appear sporadic in nature when in fact they are not.1

A 34-year-old woman with a history of endometriosis, psoriasis, and malignant melanoma presented to our dermatology clinic 2 days after a brief hospitalization during which she was diagnosed with a hypersensitivity reaction. Two days prior to her hospital admission, the patient developed a rash on the lower back with associated myalgia. The rash progressively worsened, spreading laterally to the flanks, which prompted her to seek medical attention. Blood work included a complete blood cell count with differential, complete metabolic panel, antinuclear antibody test, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, which all were within reference range. A 4-mm punch biopsy from the left lateral flank was performed and was consistent with a neutrophilic dermatosis. The patient’s symptoms diminished and she was discharged the next day with instructions to follow up with a dermatologist.

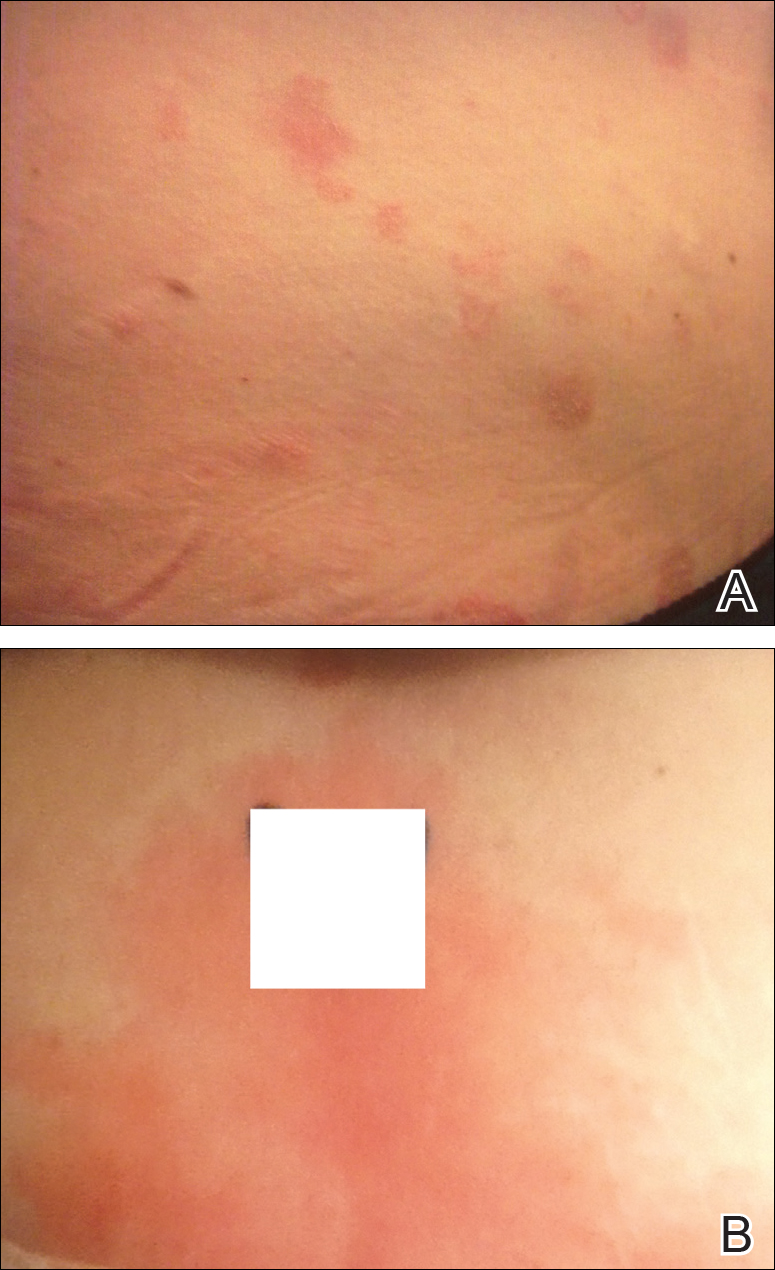

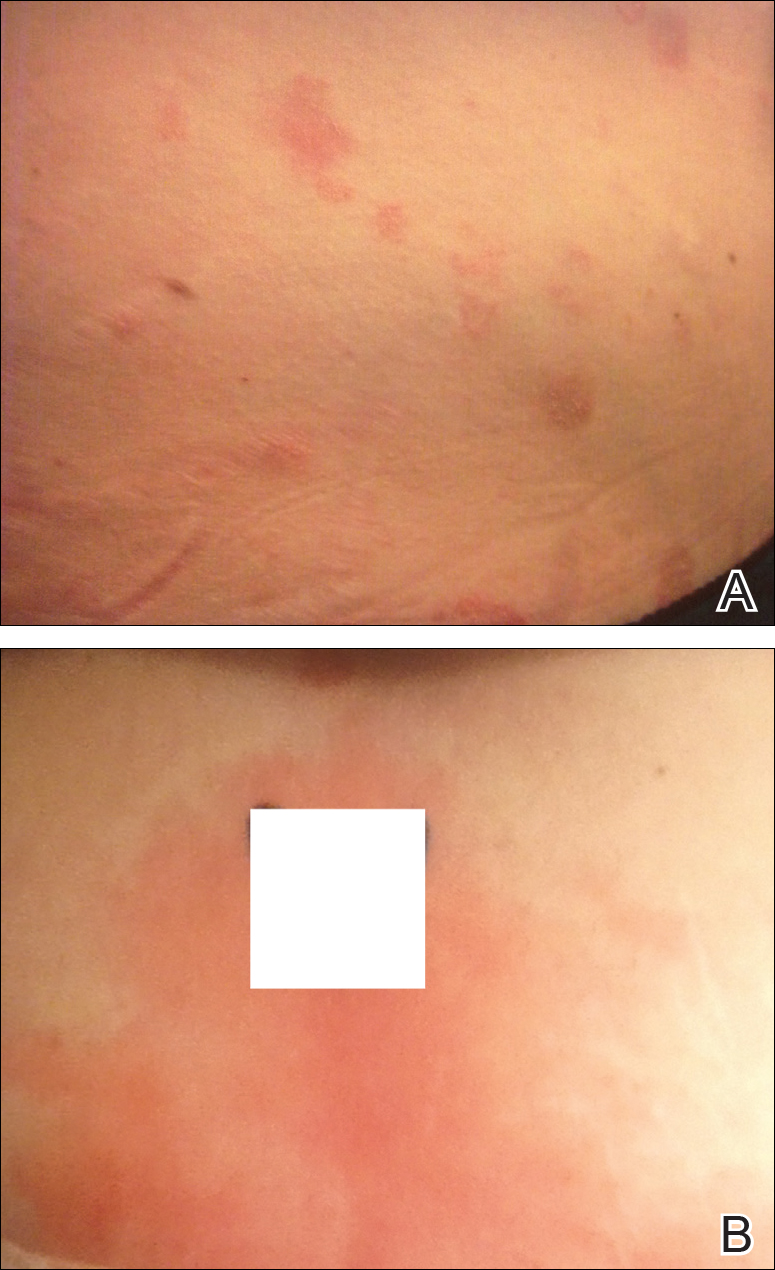

Physical examination at our clinic revealed multiple minimally indurated, erythematous plaques with superficial scaling along the left lower back and upper buttock (Figure 1). No other skin lesions were present, and palpation of the cervical, axillary, and inguinal lymph nodes was unremarkable. A repeat 6-mm punch biopsy was performed and she was sent for fasting blood work.

Histologic examination of the punch biopsy revealed a superficial and deep perivascular and interstitial dermatitis with scattered neutrophils and eosinophils. Findings were described as nonspecific, possibly representing a dermal hypersensitivity or urticarial reaction.

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase testing was within reference range, and therapy was initiated with oral dapsone 50 mg once daily as well as fexofenadine 180 mg once daily. The patient initially responded well to the oral therapy, but she experienced recurrence of the skin eruption at infrequent intervals over the next few months, requiring escalating doses of dapsone to control the symptoms. After further questioning at a subsequent visit a few months later, it was discovered that the eruption occurred near the onset of the patient’s irregular menstrual cycle.

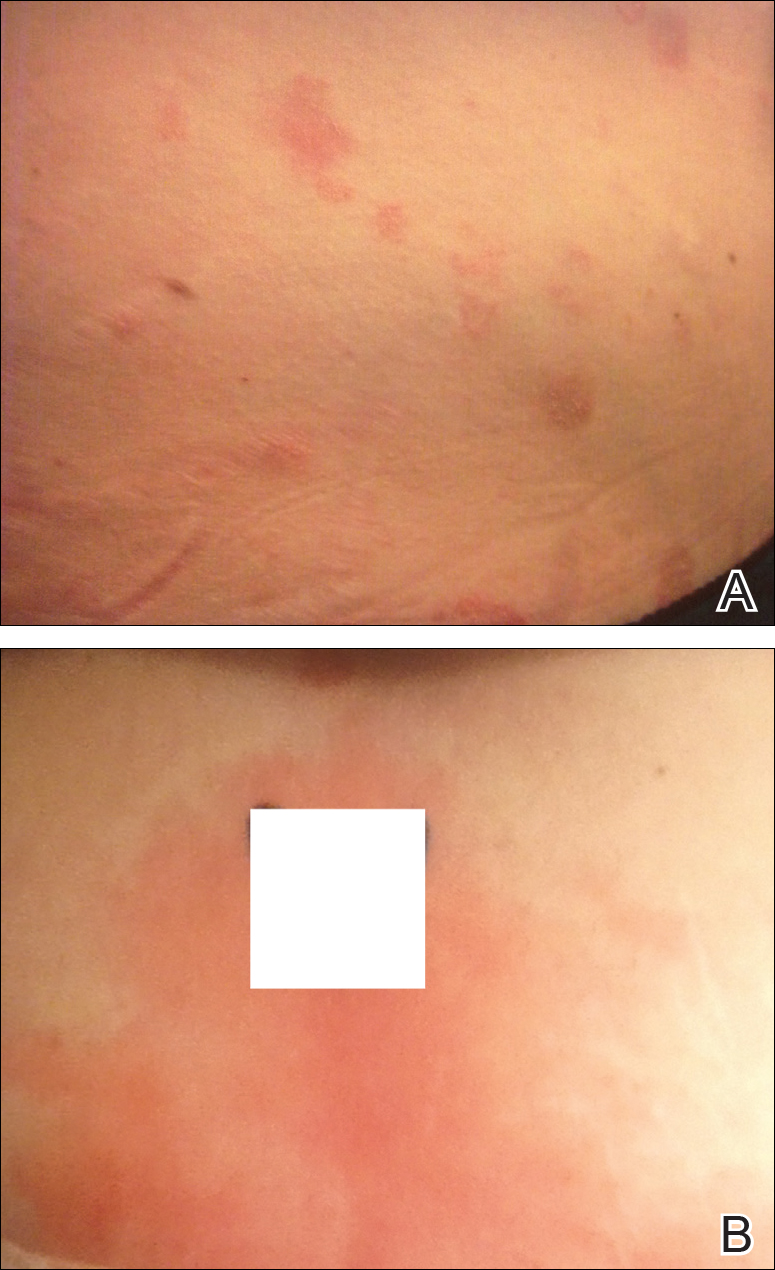

Approximately 1 year after her initial presentation, the patient returned for intradermal hormone injections to test for hormonally induced hypersensitivities. An injection of0.1 mL of a 50-mg/mL progesterone solution was administered in the right forearm as well as 0.1 mL of a 5-mg/mL estradiol solution and 0.1 mL of saline in the left forearm as a control. One hour after the injections, a strong positive reaction consisting of a 15-mm indurated plaque with surrounding wheal was noted at the site of the progesterone injection. The estradiol and saline control sites were clear of any dermal reaction (Figure 2). A diagnosis of APD was established, and the patient was referred to her gynecologist for treatment.

Due to the aggressive nature of her endometriosis, the gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist leuprolide acetate was the first-line treatment prescribed by her gynecologist; however, after 8 months of therapy with leuprolide acetate, she was still experiencing breakthrough myalgia with her menstrual cycle and opted for a hysterectomy with a bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Within weeks of surgery, the myalgia ceased and the patient was completely asymptomatic.

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis was first described in 1921.2 In affected women, the body reacts to the progesterone hormone surge during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Symptoms begin approximately 3 to 4 days prior to menses and resolve 2 to 3 days after onset of flow. These progesterone hypersensitivity reactions can present within a spectrum of morphologies and severities. The lesions can appear eczematous, urticarial, as an angioedemalike reaction, as an erythema multiforme–like reaction with targetoid lesions, or in other nonspecific ways.1,3 Some patients experience a very mild, almost asymptomatic reaction, while others have a profound reaction progressing to anaphylaxis. Originally it was thought that exogenous exposure to progesterone led to a cross-reaction or hypersensitivity to the hormone; however, there have been cases reported in females as young as 12 years of age with no prior exposure.3,4 Reactions also can vary during pregnancy. There have been reports of spontaneous abortion in some affected females, but symptoms may dissipate in others, possibly due to a slow rise in progesterone causing a desensitization reaction.3,5

According to Bandino et al,6 there are 3 criteria for diagnosis of APD: (1) skin lesions related to the menstrual cycle, (2) positive response to intradermal testing with progesterone, and (3) symptomatic improvement after inhibiting progesterone secretions by suppressing ovulation.Areas checked with intradermal testing need to be evaluated 24 and 48 hours later for possible immediate or delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions. Biopsy typically is not helpful in this diagnosis because results usually are nonspecific.

Treatment of APD is targeted toward suppressing the internal hormonal surge. By suppressing the progesterone hormone, the symptoms are alleviated. The discomfort from the skin reaction typically is unresponsive to steroids or antihistamines. Oral contraceptives are first line in most cases because they suppress ovulation. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues and tamoxifen also have been successful. For patients with severe disease that is recalcitrant to standard therapy or those who are postmenopausal, an oophorectemy is a curative option.2,4,5,7

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis is a rare cyclical dermatologic condition in which the body responds to a surge of the patient’s own progesterone hormone. The disorder is difficult to diagnose because it can present with differing morphologies and biopsy is nonspecific. It also can be increasingly difficult to diagnose in women who do not have a typical 28-day menstrual cycle. In our patient, her irregular menstrual cycle may have caused a delay in diagnosis. Although the condition is rare, APD should be included in the differential diagnosis in females with a recurrent, cyclical, or recalcitrant cutaneous eruption.

- Wojnarowska F, Greaves MW, Peachey RD, et al. Progesterone-induced erythema multiforme. J R Soc Med. 1985;78:407-408.

- Lee MK, Lee WY, Yong SJ, et al. A case of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis misdiagnosed as allergic contact dermatitis [published online February 9, 2011]. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2011;3:141-144.

- Baptist AP, Baldwin JL. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis in a patient with endometriosis: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Mol Allergy. 2004;2:10.

- Baççıoğlu A, Kocak M, Bozdag O, et al. An unusual form of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis (ADP): the role of diagnostic challenge test. World Allergy Organ J. 2007;10:S52.

- George R, Badawy SZ. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: a case report [published online August 9, 2012]. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1155/2012/757854.

- Bandino JP, Thoppil J, Kennedy JS, et al. Iatrogenic autoimmune progesterone dermatitis causes by 17α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate for preterm labor prevention. Cutis. 2011;88:241-243.

- Magen E, Feldman V. Autoimmune progesterone anaphylaxis in a 24-year-old woman. Isr Med Assoc J. 2012;14:518-519.

To the Editor:

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis (APD) is a rare dermatologic condition that can be challenging to diagnose. The associated skin lesions are not only variable in physical presentation but also in the timing of the outbreak. The skin disorder stems from an internal reaction to elevated levels of progesterone during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis can be difficult to detect; although the typical menstrual cycle is 28 days, many women have longer or shorter hormonal phases, leading to cyclical irregularity that can cause the lesions to appear sporadic in nature when in fact they are not.1

A 34-year-old woman with a history of endometriosis, psoriasis, and malignant melanoma presented to our dermatology clinic 2 days after a brief hospitalization during which she was diagnosed with a hypersensitivity reaction. Two days prior to her hospital admission, the patient developed a rash on the lower back with associated myalgia. The rash progressively worsened, spreading laterally to the flanks, which prompted her to seek medical attention. Blood work included a complete blood cell count with differential, complete metabolic panel, antinuclear antibody test, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, which all were within reference range. A 4-mm punch biopsy from the left lateral flank was performed and was consistent with a neutrophilic dermatosis. The patient’s symptoms diminished and she was discharged the next day with instructions to follow up with a dermatologist.

Physical examination at our clinic revealed multiple minimally indurated, erythematous plaques with superficial scaling along the left lower back and upper buttock (Figure 1). No other skin lesions were present, and palpation of the cervical, axillary, and inguinal lymph nodes was unremarkable. A repeat 6-mm punch biopsy was performed and she was sent for fasting blood work.

Histologic examination of the punch biopsy revealed a superficial and deep perivascular and interstitial dermatitis with scattered neutrophils and eosinophils. Findings were described as nonspecific, possibly representing a dermal hypersensitivity or urticarial reaction.

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase testing was within reference range, and therapy was initiated with oral dapsone 50 mg once daily as well as fexofenadine 180 mg once daily. The patient initially responded well to the oral therapy, but she experienced recurrence of the skin eruption at infrequent intervals over the next few months, requiring escalating doses of dapsone to control the symptoms. After further questioning at a subsequent visit a few months later, it was discovered that the eruption occurred near the onset of the patient’s irregular menstrual cycle.

Approximately 1 year after her initial presentation, the patient returned for intradermal hormone injections to test for hormonally induced hypersensitivities. An injection of0.1 mL of a 50-mg/mL progesterone solution was administered in the right forearm as well as 0.1 mL of a 5-mg/mL estradiol solution and 0.1 mL of saline in the left forearm as a control. One hour after the injections, a strong positive reaction consisting of a 15-mm indurated plaque with surrounding wheal was noted at the site of the progesterone injection. The estradiol and saline control sites were clear of any dermal reaction (Figure 2). A diagnosis of APD was established, and the patient was referred to her gynecologist for treatment.

Due to the aggressive nature of her endometriosis, the gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist leuprolide acetate was the first-line treatment prescribed by her gynecologist; however, after 8 months of therapy with leuprolide acetate, she was still experiencing breakthrough myalgia with her menstrual cycle and opted for a hysterectomy with a bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Within weeks of surgery, the myalgia ceased and the patient was completely asymptomatic.

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis was first described in 1921.2 In affected women, the body reacts to the progesterone hormone surge during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Symptoms begin approximately 3 to 4 days prior to menses and resolve 2 to 3 days after onset of flow. These progesterone hypersensitivity reactions can present within a spectrum of morphologies and severities. The lesions can appear eczematous, urticarial, as an angioedemalike reaction, as an erythema multiforme–like reaction with targetoid lesions, or in other nonspecific ways.1,3 Some patients experience a very mild, almost asymptomatic reaction, while others have a profound reaction progressing to anaphylaxis. Originally it was thought that exogenous exposure to progesterone led to a cross-reaction or hypersensitivity to the hormone; however, there have been cases reported in females as young as 12 years of age with no prior exposure.3,4 Reactions also can vary during pregnancy. There have been reports of spontaneous abortion in some affected females, but symptoms may dissipate in others, possibly due to a slow rise in progesterone causing a desensitization reaction.3,5

According to Bandino et al,6 there are 3 criteria for diagnosis of APD: (1) skin lesions related to the menstrual cycle, (2) positive response to intradermal testing with progesterone, and (3) symptomatic improvement after inhibiting progesterone secretions by suppressing ovulation.Areas checked with intradermal testing need to be evaluated 24 and 48 hours later for possible immediate or delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions. Biopsy typically is not helpful in this diagnosis because results usually are nonspecific.

Treatment of APD is targeted toward suppressing the internal hormonal surge. By suppressing the progesterone hormone, the symptoms are alleviated. The discomfort from the skin reaction typically is unresponsive to steroids or antihistamines. Oral contraceptives are first line in most cases because they suppress ovulation. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues and tamoxifen also have been successful. For patients with severe disease that is recalcitrant to standard therapy or those who are postmenopausal, an oophorectemy is a curative option.2,4,5,7

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis is a rare cyclical dermatologic condition in which the body responds to a surge of the patient’s own progesterone hormone. The disorder is difficult to diagnose because it can present with differing morphologies and biopsy is nonspecific. It also can be increasingly difficult to diagnose in women who do not have a typical 28-day menstrual cycle. In our patient, her irregular menstrual cycle may have caused a delay in diagnosis. Although the condition is rare, APD should be included in the differential diagnosis in females with a recurrent, cyclical, or recalcitrant cutaneous eruption.

To the Editor:

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis (APD) is a rare dermatologic condition that can be challenging to diagnose. The associated skin lesions are not only variable in physical presentation but also in the timing of the outbreak. The skin disorder stems from an internal reaction to elevated levels of progesterone during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis can be difficult to detect; although the typical menstrual cycle is 28 days, many women have longer or shorter hormonal phases, leading to cyclical irregularity that can cause the lesions to appear sporadic in nature when in fact they are not.1

A 34-year-old woman with a history of endometriosis, psoriasis, and malignant melanoma presented to our dermatology clinic 2 days after a brief hospitalization during which she was diagnosed with a hypersensitivity reaction. Two days prior to her hospital admission, the patient developed a rash on the lower back with associated myalgia. The rash progressively worsened, spreading laterally to the flanks, which prompted her to seek medical attention. Blood work included a complete blood cell count with differential, complete metabolic panel, antinuclear antibody test, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, which all were within reference range. A 4-mm punch biopsy from the left lateral flank was performed and was consistent with a neutrophilic dermatosis. The patient’s symptoms diminished and she was discharged the next day with instructions to follow up with a dermatologist.

Physical examination at our clinic revealed multiple minimally indurated, erythematous plaques with superficial scaling along the left lower back and upper buttock (Figure 1). No other skin lesions were present, and palpation of the cervical, axillary, and inguinal lymph nodes was unremarkable. A repeat 6-mm punch biopsy was performed and she was sent for fasting blood work.

Histologic examination of the punch biopsy revealed a superficial and deep perivascular and interstitial dermatitis with scattered neutrophils and eosinophils. Findings were described as nonspecific, possibly representing a dermal hypersensitivity or urticarial reaction.

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase testing was within reference range, and therapy was initiated with oral dapsone 50 mg once daily as well as fexofenadine 180 mg once daily. The patient initially responded well to the oral therapy, but she experienced recurrence of the skin eruption at infrequent intervals over the next few months, requiring escalating doses of dapsone to control the symptoms. After further questioning at a subsequent visit a few months later, it was discovered that the eruption occurred near the onset of the patient’s irregular menstrual cycle.

Approximately 1 year after her initial presentation, the patient returned for intradermal hormone injections to test for hormonally induced hypersensitivities. An injection of0.1 mL of a 50-mg/mL progesterone solution was administered in the right forearm as well as 0.1 mL of a 5-mg/mL estradiol solution and 0.1 mL of saline in the left forearm as a control. One hour after the injections, a strong positive reaction consisting of a 15-mm indurated plaque with surrounding wheal was noted at the site of the progesterone injection. The estradiol and saline control sites were clear of any dermal reaction (Figure 2). A diagnosis of APD was established, and the patient was referred to her gynecologist for treatment.

Due to the aggressive nature of her endometriosis, the gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist leuprolide acetate was the first-line treatment prescribed by her gynecologist; however, after 8 months of therapy with leuprolide acetate, she was still experiencing breakthrough myalgia with her menstrual cycle and opted for a hysterectomy with a bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Within weeks of surgery, the myalgia ceased and the patient was completely asymptomatic.

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis was first described in 1921.2 In affected women, the body reacts to the progesterone hormone surge during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Symptoms begin approximately 3 to 4 days prior to menses and resolve 2 to 3 days after onset of flow. These progesterone hypersensitivity reactions can present within a spectrum of morphologies and severities. The lesions can appear eczematous, urticarial, as an angioedemalike reaction, as an erythema multiforme–like reaction with targetoid lesions, or in other nonspecific ways.1,3 Some patients experience a very mild, almost asymptomatic reaction, while others have a profound reaction progressing to anaphylaxis. Originally it was thought that exogenous exposure to progesterone led to a cross-reaction or hypersensitivity to the hormone; however, there have been cases reported in females as young as 12 years of age with no prior exposure.3,4 Reactions also can vary during pregnancy. There have been reports of spontaneous abortion in some affected females, but symptoms may dissipate in others, possibly due to a slow rise in progesterone causing a desensitization reaction.3,5

According to Bandino et al,6 there are 3 criteria for diagnosis of APD: (1) skin lesions related to the menstrual cycle, (2) positive response to intradermal testing with progesterone, and (3) symptomatic improvement after inhibiting progesterone secretions by suppressing ovulation.Areas checked with intradermal testing need to be evaluated 24 and 48 hours later for possible immediate or delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions. Biopsy typically is not helpful in this diagnosis because results usually are nonspecific.

Treatment of APD is targeted toward suppressing the internal hormonal surge. By suppressing the progesterone hormone, the symptoms are alleviated. The discomfort from the skin reaction typically is unresponsive to steroids or antihistamines. Oral contraceptives are first line in most cases because they suppress ovulation. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues and tamoxifen also have been successful. For patients with severe disease that is recalcitrant to standard therapy or those who are postmenopausal, an oophorectemy is a curative option.2,4,5,7

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis is a rare cyclical dermatologic condition in which the body responds to a surge of the patient’s own progesterone hormone. The disorder is difficult to diagnose because it can present with differing morphologies and biopsy is nonspecific. It also can be increasingly difficult to diagnose in women who do not have a typical 28-day menstrual cycle. In our patient, her irregular menstrual cycle may have caused a delay in diagnosis. Although the condition is rare, APD should be included in the differential diagnosis in females with a recurrent, cyclical, or recalcitrant cutaneous eruption.

- Wojnarowska F, Greaves MW, Peachey RD, et al. Progesterone-induced erythema multiforme. J R Soc Med. 1985;78:407-408.

- Lee MK, Lee WY, Yong SJ, et al. A case of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis misdiagnosed as allergic contact dermatitis [published online February 9, 2011]. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2011;3:141-144.

- Baptist AP, Baldwin JL. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis in a patient with endometriosis: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Mol Allergy. 2004;2:10.

- Baççıoğlu A, Kocak M, Bozdag O, et al. An unusual form of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis (ADP): the role of diagnostic challenge test. World Allergy Organ J. 2007;10:S52.

- George R, Badawy SZ. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: a case report [published online August 9, 2012]. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1155/2012/757854.

- Bandino JP, Thoppil J, Kennedy JS, et al. Iatrogenic autoimmune progesterone dermatitis causes by 17α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate for preterm labor prevention. Cutis. 2011;88:241-243.

- Magen E, Feldman V. Autoimmune progesterone anaphylaxis in a 24-year-old woman. Isr Med Assoc J. 2012;14:518-519.

- Wojnarowska F, Greaves MW, Peachey RD, et al. Progesterone-induced erythema multiforme. J R Soc Med. 1985;78:407-408.

- Lee MK, Lee WY, Yong SJ, et al. A case of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis misdiagnosed as allergic contact dermatitis [published online February 9, 2011]. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2011;3:141-144.

- Baptist AP, Baldwin JL. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis in a patient with endometriosis: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Mol Allergy. 2004;2:10.

- Baççıoğlu A, Kocak M, Bozdag O, et al. An unusual form of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis (ADP): the role of diagnostic challenge test. World Allergy Organ J. 2007;10:S52.

- George R, Badawy SZ. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: a case report [published online August 9, 2012]. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1155/2012/757854.

- Bandino JP, Thoppil J, Kennedy JS, et al. Iatrogenic autoimmune progesterone dermatitis causes by 17α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate for preterm labor prevention. Cutis. 2011;88:241-243.

- Magen E, Feldman V. Autoimmune progesterone anaphylaxis in a 24-year-old woman. Isr Med Assoc J. 2012;14:518-519.

Practice Points

- Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis (APD) is a hypersensitivity reaction to the progesterone surge during a woman’s menstrual cycle.

- Patients with APD often are misdiagnosed for years due to the variability of each woman’s menstrual cycle, making the correlation difficult.

- It is important to keep APD in mind for any recalcitrant or recurrent rash in females. A thorough history is critical when formulating a diagnosis.

Erythematous patches on the hands

A 49-year-old Caucasian man sought care at our clinic for erythematous patches on the dorsal surface of his hands. The patient indicated that these lesions had appeared approximately 2 to 3 years earlier and that they had become increasingly painful when exposed to sunlight. The patient’s mother also recalled multiple sunburns that he’d suffered in the past.

The patient had a mild mental impairment and struggled with obsessive-compulsive disorder. He admitted to washing his hands 10 to 15 times a day, and was previously given a diagnosis of dyshidrosis secondary to excessive hand washing. The patient was treated with moisturizing creams, but his symptoms did not improve.

Examination of the dorsal surface of his hands revealed multiple erythematous patches, blisters, and calluses, as well as ulcerations on the proximal and distal interphalangeal joints (FIGURE 1). There were also scarred and linear plaques on the bilateral proximal and distal interphalangeal joints. The patient had no other lesions on his body.

FIGURE 1

Erythematous patches, blisters, calluses, and ulcerations

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythropoietic protoporphyria

Erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP) is a metabolic disease that is caused by a deficiency in ferrochelatase enzyme activity.1,2 Ferrochelatase is the last enzyme in the heme biosynthetic pathway, which is responsible for the incorporation of iron onto protoporphyrin IX.1 Ferrochelatase activity in patients with EPP is typically 10% to 25% of normal, resulting in an accumulation of protoporphyrin IX in the skin, erythrocytes, liver, and plasma.1,3 There are both autosomal dominant and recessive forms of EPP, and it is the most common porphyria found in children.1,3

A characteristic that distinguishes EPP from other porphyrias is the rapid onset of photosensitivity associated with pruritus and a stinging or burning sensation on the sun-exposed areas of the body—typically, the cheeks, nose, and dorsal surface of the hands.4 These symptoms are commonly followed by edema, erythema, and in more severe cases, petechiae.3,4 With repeated sun exposure, the affected skin may develop a waxy thickening with shallow linear or elliptical scars, making the patient’s skin appear much older than it actually is.3,4 Although blisters, erosions, and crusting are not always present, they can manifest with prolonged sun exposure.1

What you may also see

Hepatobiliary disease is present in about 25% of patients, and may be the only manifestation of the disease.1 The deleterious effects of protoporphyrin are concentration dependent, so a wide variation in the severity of hepatobiliary disease exists. Cholelithiasis and micro-cytic hypochromic anemia are common on the mild end of the spectrum, but life-threatening complications such as hepatic failure have been reported in about 2% to 5% of cases.1,5

When it’s diagnosed. EPP usually manifests by 2 to 5 years of age, but it may not be diagnosed until adulthood.3 Such a delay may occur because of a lack of cutaneous lesions, mild symptoms, or a late onset of symptoms.1

Consider these conditions in the differential

Contact dermatitis. This inflammatory skin condition can occur when a foreign substance irritates the skin (irritant contact dermatitis) or result from a delayed hypersensitivity reaction that’s evoked by reexposure to a substance (allergic contact dermatitis). Acute lesions are typically well defined and confined to the site of exposure. They are characterized by erythema, vesicles or bullae, erosions, and crusts. In chronic cases, the lesions are ill-defined and involve plaques, fissures, scaling, and/or crusts.4,6

Porphyria cutanea tarda. This most common form of porphyria is characterized by increased sensitivity and fragility of the skin.3 (For more information, see “Genetic blood disorders: Questions you need to ask,” J Fam Pract. 2012;61:30-37.) Vesicles and bullae will form after minimal trauma, typically on the dorsal surface of the hands, extensor surfaces of the forearms, and the face. These lesions will eventually form erosions and heal slowly to form atrophic scars. Excessive hair growth on the face, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, scarring alopecia, and scleroderma-like changes with yellowish-white plaques have also been described in porphyria cutanea tarda. Wood’s lamp examination of urine will reveal a coral-red fluorescence.4,7

Dyshidrotic eczema. This disease is characterized by the sudden onset of pruritic, clear vesicles on the fingers, palms, and soles. The vesicles are deep-seated and are typically devoid of surrounding erythema. Each episode will spontaneously regress in 2 to 3 weeks, but this disease can be disabling due to the recurring nature of the outbreaks.4,8

Solar urticaria. Within minutes of sun exposure, erythematous patches with or without wheals will appear. The lesions typically last less than 24 hours, and are most commonly found on the chest and upper arms. Pruritus and a burning sensation frequently accompany flares of solar urticaria, and pain may be present but is not a common symptom. In severe cases, an anaphylactoid reaction can occur, with light-headedness, nausea, bronchospasm, and syncope.4,9

Hydroa vacciniforme. Within hours of sun exposure, erythematous macules will appear. They will progress to papules and vesicles, and may become hemorrhagic. These lesions are typically found on the face, ears, and dorsa of the hands in a symmetric, clustered pattern. Pruritus and a stinging sensation may accompany the lesions, as well as general malaise or fever. Over the course of a few days, the lesions will become necrotic, form a hemorrhagic crust, and heal with ”pox-like” vacciniform scars.4,9

Confirm your suspicions with testing

There should be a high degree of suspicion for EPP when any child or adult presents with photosensitivity.10,11 The absence or delayed onset of visible lesions can make the diagnosis difficult and cause the patient considerable suffering.12

If EPP is suspected, order lab work for confirmation. The most diagnostically useful test is the erythrocyte protoporphyrin level, which will be increased in patients with EPP. These levels can range from several hundred to several thousand μg/100 mL of packed red blood cells (normal= <35 μg/100 mL).3 In addition, elevated levels of protoporphyrin are found in the feces. However, unlike other porphyrias, the level of urine porphyrins is normal (because protoporphyrin IX is water-soluble).1,3

Due to the incidence of hepatobiliary disease in EPP, liver enzymes should be drawn and the proper imaging performed if abnormal values are obtained. Biopsy of the involved skin, with histologic review, will also aid in the diagnosis if other testing is inconclusive.1,4

Treatment: Protection from sun is key

While complete sun exposure avoidance would prevent most sequelae in EPP, this is not always a feasible option. Covering the skin with sun-protective clothing and using sunscreen that contains titanium oxide or zinc oxide are acceptable alternatives to overt avoidance1,3,10,13 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A). Beta-carotene at doses of 60 to 180 mg/d for adults or 30 to 90 mg/d for children to achieve a serum level of 600 mcg/dL has also been shown to be effective in reducing photosensitivity in some cases 1,2,5 (SOR: B). Cysteine, antihistamines, phototherapy, pyroxidine, and vitamin C have also been used to treat EPP, but have demonstrated limited efficacy1,3,10 (SOR: B).

Hepatobiliary complications. Treating hepatobiliary complications is dependent upon the degree of dysfunction. Cholestyramine can be used to increase the fecal excretion of protoporphyrins in liver dysfunction1,3,10 (SOR: A). In severe liver dysfunction, blood transfusions can be utilized until a liver transplant can be performed1,3,10 (SOR: A). Liver transplantation, however, does not correct the metabolic error, and damage to the transplanted liver can occur.1

Sun block and supplements for our patient

After discussing the risks and benefits of treatment, our patient elected to use an over-the-counter zinc oxide sun block, as well as begin beta-carotene supplementation at 60 mg/d. We slowly increased the beta-carotene to therapeutic levels, and reevaluated for efficacy. To treat the lesions on his hands, we started the patient on tacrolimus (Protopic) 0.1% ointment once daily (to avoid using a topical steroid due to his skin fragility) and a skin protectant/moisturizer (Theraseal) 2 to 3 times daily to reduce irritation.

After treatment and minimal sun exposure for several months, our patient saw a dramatic improvement in his disease, with no blistering or ulcerations noted (FIGURE 2).

FIGURE 2

A dramatic improvement

After minimizing his exposure to the sun, using tacrolimus 0.1% ointment and a skin moisturizer, and taking a beta-carotene supplement, the appearance of our patient’s hands improved. His hands were less erythematous and there were no ulcerations. Callus formation persisted.

CORRESPONDENCE David A. Kasper, DO, MBA, Skin Cancer Institute, 1003 South Broad Street, Lansdale, PA 19006; davidkas@pcom.edu

1. Michaels BD, Del Rosso JQ, Mobini N, et al. Erythropoietic protoporphyria: a case report and literature review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:44-48.

2. Wahlin S, Floderus Y, Stål P, et al. Erythropoietic protoporphyria in Sweden: demographic, clinical, biochemical and genetic characteristics. J Intern Med. 2011;269:278-288.

3. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Errors in metabolism. In: James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier; 2011:511–515.

4. Murphy GM. Porphyria. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini R, eds. Dermatology. 1st ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier; 2003:679–686.

5. Herrero C, To-Figueras J, Badenas C, et al. Clinical, biochemical, and genetic study of 11 patients with erythropoietic protoporphyria including one with homozygous disease. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1125-1129.

6. Usatine RP, Riojas M. Diagnosis and management of contact dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:249-255.

7. Yeh SW, Ahmed B, Sami N, et al. Blistering disorders: diagnosis and treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2003;16:214-223.

8. Kedrowski DA, Warshaw EM. Hand dermatitis: a review of clinical features, diagnosis, and management. Dermatol Nurs. 2008;20:17-25.

9. Gambichler T, Al-Muhammadi R, Boms S. Immunologically mediated photodermatoses: diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:169-180.

10. Murphy GM. Diagnosis and management of the erythropoietic porphyrias. Dermatol Ther. 2003;16:57-64.

11. Lecluse AL, Kuck-Koot VC, van Weelden H, et al. Erythropoietic protoporphyria without skin symptoms–you do not always see what they feel. Eur J Pediatr. 2008;167:703-706.

12. Holme SA, Anstey AV, Finlay AY, et al. Erythropoietic protoporphyria in the U.K.: clinical features and effect on quality of life. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:574-581.

13. Sies C, Florkowski C, George P, et al. Clinical indications for the investigation of porphyria: case examples and evolving laboratory approaches to its diagnosis in New Zealand. NZ Med J. 2005;118:U1658.-

A 49-year-old Caucasian man sought care at our clinic for erythematous patches on the dorsal surface of his hands. The patient indicated that these lesions had appeared approximately 2 to 3 years earlier and that they had become increasingly painful when exposed to sunlight. The patient’s mother also recalled multiple sunburns that he’d suffered in the past.

The patient had a mild mental impairment and struggled with obsessive-compulsive disorder. He admitted to washing his hands 10 to 15 times a day, and was previously given a diagnosis of dyshidrosis secondary to excessive hand washing. The patient was treated with moisturizing creams, but his symptoms did not improve.

Examination of the dorsal surface of his hands revealed multiple erythematous patches, blisters, and calluses, as well as ulcerations on the proximal and distal interphalangeal joints (FIGURE 1). There were also scarred and linear plaques on the bilateral proximal and distal interphalangeal joints. The patient had no other lesions on his body.

FIGURE 1

Erythematous patches, blisters, calluses, and ulcerations

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythropoietic protoporphyria

Erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP) is a metabolic disease that is caused by a deficiency in ferrochelatase enzyme activity.1,2 Ferrochelatase is the last enzyme in the heme biosynthetic pathway, which is responsible for the incorporation of iron onto protoporphyrin IX.1 Ferrochelatase activity in patients with EPP is typically 10% to 25% of normal, resulting in an accumulation of protoporphyrin IX in the skin, erythrocytes, liver, and plasma.1,3 There are both autosomal dominant and recessive forms of EPP, and it is the most common porphyria found in children.1,3

A characteristic that distinguishes EPP from other porphyrias is the rapid onset of photosensitivity associated with pruritus and a stinging or burning sensation on the sun-exposed areas of the body—typically, the cheeks, nose, and dorsal surface of the hands.4 These symptoms are commonly followed by edema, erythema, and in more severe cases, petechiae.3,4 With repeated sun exposure, the affected skin may develop a waxy thickening with shallow linear or elliptical scars, making the patient’s skin appear much older than it actually is.3,4 Although blisters, erosions, and crusting are not always present, they can manifest with prolonged sun exposure.1

What you may also see

Hepatobiliary disease is present in about 25% of patients, and may be the only manifestation of the disease.1 The deleterious effects of protoporphyrin are concentration dependent, so a wide variation in the severity of hepatobiliary disease exists. Cholelithiasis and micro-cytic hypochromic anemia are common on the mild end of the spectrum, but life-threatening complications such as hepatic failure have been reported in about 2% to 5% of cases.1,5

When it’s diagnosed. EPP usually manifests by 2 to 5 years of age, but it may not be diagnosed until adulthood.3 Such a delay may occur because of a lack of cutaneous lesions, mild symptoms, or a late onset of symptoms.1

Consider these conditions in the differential

Contact dermatitis. This inflammatory skin condition can occur when a foreign substance irritates the skin (irritant contact dermatitis) or result from a delayed hypersensitivity reaction that’s evoked by reexposure to a substance (allergic contact dermatitis). Acute lesions are typically well defined and confined to the site of exposure. They are characterized by erythema, vesicles or bullae, erosions, and crusts. In chronic cases, the lesions are ill-defined and involve plaques, fissures, scaling, and/or crusts.4,6

Porphyria cutanea tarda. This most common form of porphyria is characterized by increased sensitivity and fragility of the skin.3 (For more information, see “Genetic blood disorders: Questions you need to ask,” J Fam Pract. 2012;61:30-37.) Vesicles and bullae will form after minimal trauma, typically on the dorsal surface of the hands, extensor surfaces of the forearms, and the face. These lesions will eventually form erosions and heal slowly to form atrophic scars. Excessive hair growth on the face, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, scarring alopecia, and scleroderma-like changes with yellowish-white plaques have also been described in porphyria cutanea tarda. Wood’s lamp examination of urine will reveal a coral-red fluorescence.4,7

Dyshidrotic eczema. This disease is characterized by the sudden onset of pruritic, clear vesicles on the fingers, palms, and soles. The vesicles are deep-seated and are typically devoid of surrounding erythema. Each episode will spontaneously regress in 2 to 3 weeks, but this disease can be disabling due to the recurring nature of the outbreaks.4,8

Solar urticaria. Within minutes of sun exposure, erythematous patches with or without wheals will appear. The lesions typically last less than 24 hours, and are most commonly found on the chest and upper arms. Pruritus and a burning sensation frequently accompany flares of solar urticaria, and pain may be present but is not a common symptom. In severe cases, an anaphylactoid reaction can occur, with light-headedness, nausea, bronchospasm, and syncope.4,9

Hydroa vacciniforme. Within hours of sun exposure, erythematous macules will appear. They will progress to papules and vesicles, and may become hemorrhagic. These lesions are typically found on the face, ears, and dorsa of the hands in a symmetric, clustered pattern. Pruritus and a stinging sensation may accompany the lesions, as well as general malaise or fever. Over the course of a few days, the lesions will become necrotic, form a hemorrhagic crust, and heal with ”pox-like” vacciniform scars.4,9

Confirm your suspicions with testing

There should be a high degree of suspicion for EPP when any child or adult presents with photosensitivity.10,11 The absence or delayed onset of visible lesions can make the diagnosis difficult and cause the patient considerable suffering.12

If EPP is suspected, order lab work for confirmation. The most diagnostically useful test is the erythrocyte protoporphyrin level, which will be increased in patients with EPP. These levels can range from several hundred to several thousand μg/100 mL of packed red blood cells (normal= <35 μg/100 mL).3 In addition, elevated levels of protoporphyrin are found in the feces. However, unlike other porphyrias, the level of urine porphyrins is normal (because protoporphyrin IX is water-soluble).1,3

Due to the incidence of hepatobiliary disease in EPP, liver enzymes should be drawn and the proper imaging performed if abnormal values are obtained. Biopsy of the involved skin, with histologic review, will also aid in the diagnosis if other testing is inconclusive.1,4

Treatment: Protection from sun is key

While complete sun exposure avoidance would prevent most sequelae in EPP, this is not always a feasible option. Covering the skin with sun-protective clothing and using sunscreen that contains titanium oxide or zinc oxide are acceptable alternatives to overt avoidance1,3,10,13 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A). Beta-carotene at doses of 60 to 180 mg/d for adults or 30 to 90 mg/d for children to achieve a serum level of 600 mcg/dL has also been shown to be effective in reducing photosensitivity in some cases 1,2,5 (SOR: B). Cysteine, antihistamines, phototherapy, pyroxidine, and vitamin C have also been used to treat EPP, but have demonstrated limited efficacy1,3,10 (SOR: B).

Hepatobiliary complications. Treating hepatobiliary complications is dependent upon the degree of dysfunction. Cholestyramine can be used to increase the fecal excretion of protoporphyrins in liver dysfunction1,3,10 (SOR: A). In severe liver dysfunction, blood transfusions can be utilized until a liver transplant can be performed1,3,10 (SOR: A). Liver transplantation, however, does not correct the metabolic error, and damage to the transplanted liver can occur.1

Sun block and supplements for our patient

After discussing the risks and benefits of treatment, our patient elected to use an over-the-counter zinc oxide sun block, as well as begin beta-carotene supplementation at 60 mg/d. We slowly increased the beta-carotene to therapeutic levels, and reevaluated for efficacy. To treat the lesions on his hands, we started the patient on tacrolimus (Protopic) 0.1% ointment once daily (to avoid using a topical steroid due to his skin fragility) and a skin protectant/moisturizer (Theraseal) 2 to 3 times daily to reduce irritation.

After treatment and minimal sun exposure for several months, our patient saw a dramatic improvement in his disease, with no blistering or ulcerations noted (FIGURE 2).

FIGURE 2

A dramatic improvement

After minimizing his exposure to the sun, using tacrolimus 0.1% ointment and a skin moisturizer, and taking a beta-carotene supplement, the appearance of our patient’s hands improved. His hands were less erythematous and there were no ulcerations. Callus formation persisted.

CORRESPONDENCE David A. Kasper, DO, MBA, Skin Cancer Institute, 1003 South Broad Street, Lansdale, PA 19006; davidkas@pcom.edu

A 49-year-old Caucasian man sought care at our clinic for erythematous patches on the dorsal surface of his hands. The patient indicated that these lesions had appeared approximately 2 to 3 years earlier and that they had become increasingly painful when exposed to sunlight. The patient’s mother also recalled multiple sunburns that he’d suffered in the past.

The patient had a mild mental impairment and struggled with obsessive-compulsive disorder. He admitted to washing his hands 10 to 15 times a day, and was previously given a diagnosis of dyshidrosis secondary to excessive hand washing. The patient was treated with moisturizing creams, but his symptoms did not improve.

Examination of the dorsal surface of his hands revealed multiple erythematous patches, blisters, and calluses, as well as ulcerations on the proximal and distal interphalangeal joints (FIGURE 1). There were also scarred and linear plaques on the bilateral proximal and distal interphalangeal joints. The patient had no other lesions on his body.

FIGURE 1

Erythematous patches, blisters, calluses, and ulcerations

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythropoietic protoporphyria

Erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP) is a metabolic disease that is caused by a deficiency in ferrochelatase enzyme activity.1,2 Ferrochelatase is the last enzyme in the heme biosynthetic pathway, which is responsible for the incorporation of iron onto protoporphyrin IX.1 Ferrochelatase activity in patients with EPP is typically 10% to 25% of normal, resulting in an accumulation of protoporphyrin IX in the skin, erythrocytes, liver, and plasma.1,3 There are both autosomal dominant and recessive forms of EPP, and it is the most common porphyria found in children.1,3

A characteristic that distinguishes EPP from other porphyrias is the rapid onset of photosensitivity associated with pruritus and a stinging or burning sensation on the sun-exposed areas of the body—typically, the cheeks, nose, and dorsal surface of the hands.4 These symptoms are commonly followed by edema, erythema, and in more severe cases, petechiae.3,4 With repeated sun exposure, the affected skin may develop a waxy thickening with shallow linear or elliptical scars, making the patient’s skin appear much older than it actually is.3,4 Although blisters, erosions, and crusting are not always present, they can manifest with prolonged sun exposure.1

What you may also see

Hepatobiliary disease is present in about 25% of patients, and may be the only manifestation of the disease.1 The deleterious effects of protoporphyrin are concentration dependent, so a wide variation in the severity of hepatobiliary disease exists. Cholelithiasis and micro-cytic hypochromic anemia are common on the mild end of the spectrum, but life-threatening complications such as hepatic failure have been reported in about 2% to 5% of cases.1,5

When it’s diagnosed. EPP usually manifests by 2 to 5 years of age, but it may not be diagnosed until adulthood.3 Such a delay may occur because of a lack of cutaneous lesions, mild symptoms, or a late onset of symptoms.1

Consider these conditions in the differential

Contact dermatitis. This inflammatory skin condition can occur when a foreign substance irritates the skin (irritant contact dermatitis) or result from a delayed hypersensitivity reaction that’s evoked by reexposure to a substance (allergic contact dermatitis). Acute lesions are typically well defined and confined to the site of exposure. They are characterized by erythema, vesicles or bullae, erosions, and crusts. In chronic cases, the lesions are ill-defined and involve plaques, fissures, scaling, and/or crusts.4,6

Porphyria cutanea tarda. This most common form of porphyria is characterized by increased sensitivity and fragility of the skin.3 (For more information, see “Genetic blood disorders: Questions you need to ask,” J Fam Pract. 2012;61:30-37.) Vesicles and bullae will form after minimal trauma, typically on the dorsal surface of the hands, extensor surfaces of the forearms, and the face. These lesions will eventually form erosions and heal slowly to form atrophic scars. Excessive hair growth on the face, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, scarring alopecia, and scleroderma-like changes with yellowish-white plaques have also been described in porphyria cutanea tarda. Wood’s lamp examination of urine will reveal a coral-red fluorescence.4,7

Dyshidrotic eczema. This disease is characterized by the sudden onset of pruritic, clear vesicles on the fingers, palms, and soles. The vesicles are deep-seated and are typically devoid of surrounding erythema. Each episode will spontaneously regress in 2 to 3 weeks, but this disease can be disabling due to the recurring nature of the outbreaks.4,8

Solar urticaria. Within minutes of sun exposure, erythematous patches with or without wheals will appear. The lesions typically last less than 24 hours, and are most commonly found on the chest and upper arms. Pruritus and a burning sensation frequently accompany flares of solar urticaria, and pain may be present but is not a common symptom. In severe cases, an anaphylactoid reaction can occur, with light-headedness, nausea, bronchospasm, and syncope.4,9

Hydroa vacciniforme. Within hours of sun exposure, erythematous macules will appear. They will progress to papules and vesicles, and may become hemorrhagic. These lesions are typically found on the face, ears, and dorsa of the hands in a symmetric, clustered pattern. Pruritus and a stinging sensation may accompany the lesions, as well as general malaise or fever. Over the course of a few days, the lesions will become necrotic, form a hemorrhagic crust, and heal with ”pox-like” vacciniform scars.4,9

Confirm your suspicions with testing

There should be a high degree of suspicion for EPP when any child or adult presents with photosensitivity.10,11 The absence or delayed onset of visible lesions can make the diagnosis difficult and cause the patient considerable suffering.12

If EPP is suspected, order lab work for confirmation. The most diagnostically useful test is the erythrocyte protoporphyrin level, which will be increased in patients with EPP. These levels can range from several hundred to several thousand μg/100 mL of packed red blood cells (normal= <35 μg/100 mL).3 In addition, elevated levels of protoporphyrin are found in the feces. However, unlike other porphyrias, the level of urine porphyrins is normal (because protoporphyrin IX is water-soluble).1,3

Due to the incidence of hepatobiliary disease in EPP, liver enzymes should be drawn and the proper imaging performed if abnormal values are obtained. Biopsy of the involved skin, with histologic review, will also aid in the diagnosis if other testing is inconclusive.1,4

Treatment: Protection from sun is key

While complete sun exposure avoidance would prevent most sequelae in EPP, this is not always a feasible option. Covering the skin with sun-protective clothing and using sunscreen that contains titanium oxide or zinc oxide are acceptable alternatives to overt avoidance1,3,10,13 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A). Beta-carotene at doses of 60 to 180 mg/d for adults or 30 to 90 mg/d for children to achieve a serum level of 600 mcg/dL has also been shown to be effective in reducing photosensitivity in some cases 1,2,5 (SOR: B). Cysteine, antihistamines, phototherapy, pyroxidine, and vitamin C have also been used to treat EPP, but have demonstrated limited efficacy1,3,10 (SOR: B).

Hepatobiliary complications. Treating hepatobiliary complications is dependent upon the degree of dysfunction. Cholestyramine can be used to increase the fecal excretion of protoporphyrins in liver dysfunction1,3,10 (SOR: A). In severe liver dysfunction, blood transfusions can be utilized until a liver transplant can be performed1,3,10 (SOR: A). Liver transplantation, however, does not correct the metabolic error, and damage to the transplanted liver can occur.1

Sun block and supplements for our patient

After discussing the risks and benefits of treatment, our patient elected to use an over-the-counter zinc oxide sun block, as well as begin beta-carotene supplementation at 60 mg/d. We slowly increased the beta-carotene to therapeutic levels, and reevaluated for efficacy. To treat the lesions on his hands, we started the patient on tacrolimus (Protopic) 0.1% ointment once daily (to avoid using a topical steroid due to his skin fragility) and a skin protectant/moisturizer (Theraseal) 2 to 3 times daily to reduce irritation.

After treatment and minimal sun exposure for several months, our patient saw a dramatic improvement in his disease, with no blistering or ulcerations noted (FIGURE 2).

FIGURE 2

A dramatic improvement

After minimizing his exposure to the sun, using tacrolimus 0.1% ointment and a skin moisturizer, and taking a beta-carotene supplement, the appearance of our patient’s hands improved. His hands were less erythematous and there were no ulcerations. Callus formation persisted.

CORRESPONDENCE David A. Kasper, DO, MBA, Skin Cancer Institute, 1003 South Broad Street, Lansdale, PA 19006; davidkas@pcom.edu

1. Michaels BD, Del Rosso JQ, Mobini N, et al. Erythropoietic protoporphyria: a case report and literature review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:44-48.

2. Wahlin S, Floderus Y, Stål P, et al. Erythropoietic protoporphyria in Sweden: demographic, clinical, biochemical and genetic characteristics. J Intern Med. 2011;269:278-288.

3. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Errors in metabolism. In: James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier; 2011:511–515.

4. Murphy GM. Porphyria. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini R, eds. Dermatology. 1st ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier; 2003:679–686.

5. Herrero C, To-Figueras J, Badenas C, et al. Clinical, biochemical, and genetic study of 11 patients with erythropoietic protoporphyria including one with homozygous disease. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1125-1129.

6. Usatine RP, Riojas M. Diagnosis and management of contact dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:249-255.

7. Yeh SW, Ahmed B, Sami N, et al. Blistering disorders: diagnosis and treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2003;16:214-223.

8. Kedrowski DA, Warshaw EM. Hand dermatitis: a review of clinical features, diagnosis, and management. Dermatol Nurs. 2008;20:17-25.

9. Gambichler T, Al-Muhammadi R, Boms S. Immunologically mediated photodermatoses: diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:169-180.

10. Murphy GM. Diagnosis and management of the erythropoietic porphyrias. Dermatol Ther. 2003;16:57-64.

11. Lecluse AL, Kuck-Koot VC, van Weelden H, et al. Erythropoietic protoporphyria without skin symptoms–you do not always see what they feel. Eur J Pediatr. 2008;167:703-706.

12. Holme SA, Anstey AV, Finlay AY, et al. Erythropoietic protoporphyria in the U.K.: clinical features and effect on quality of life. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:574-581.

13. Sies C, Florkowski C, George P, et al. Clinical indications for the investigation of porphyria: case examples and evolving laboratory approaches to its diagnosis in New Zealand. NZ Med J. 2005;118:U1658.-

1. Michaels BD, Del Rosso JQ, Mobini N, et al. Erythropoietic protoporphyria: a case report and literature review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:44-48.

2. Wahlin S, Floderus Y, Stål P, et al. Erythropoietic protoporphyria in Sweden: demographic, clinical, biochemical and genetic characteristics. J Intern Med. 2011;269:278-288.

3. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Errors in metabolism. In: James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier; 2011:511–515.

4. Murphy GM. Porphyria. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini R, eds. Dermatology. 1st ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier; 2003:679–686.

5. Herrero C, To-Figueras J, Badenas C, et al. Clinical, biochemical, and genetic study of 11 patients with erythropoietic protoporphyria including one with homozygous disease. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1125-1129.

6. Usatine RP, Riojas M. Diagnosis and management of contact dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:249-255.

7. Yeh SW, Ahmed B, Sami N, et al. Blistering disorders: diagnosis and treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2003;16:214-223.

8. Kedrowski DA, Warshaw EM. Hand dermatitis: a review of clinical features, diagnosis, and management. Dermatol Nurs. 2008;20:17-25.

9. Gambichler T, Al-Muhammadi R, Boms S. Immunologically mediated photodermatoses: diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:169-180.

10. Murphy GM. Diagnosis and management of the erythropoietic porphyrias. Dermatol Ther. 2003;16:57-64.

11. Lecluse AL, Kuck-Koot VC, van Weelden H, et al. Erythropoietic protoporphyria without skin symptoms–you do not always see what they feel. Eur J Pediatr. 2008;167:703-706.

12. Holme SA, Anstey AV, Finlay AY, et al. Erythropoietic protoporphyria in the U.K.: clinical features and effect on quality of life. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:574-581.

13. Sies C, Florkowski C, George P, et al. Clinical indications for the investigation of porphyria: case examples and evolving laboratory approaches to its diagnosis in New Zealand. NZ Med J. 2005;118:U1658.-