User login

Maybelle Cowan-Lincoln began her career in healthcare communications with an internet start-up for which she created and wrote content for www.cysticfibrosis.com. She has worked in pharmaceutical advertising and penned disease treatment guidelines, monographs, and patient educational materials. Maybelle has written for The Hospitalist and other medical and scientific titles since 2011.

6 Tips for Community Hospitalists Initiating QI Projects

The Society of Hospital Medicine asserts that one of the key principles of an effective hospital medicine group is demonstrating a commitment to continuous quality improvement (QI) and actively participating in initiatives directed at quality and patient safety.1 Large hospitalist groups expect their physicians to contribute to the QI initiatives of the hospitals they staff. But as any hospitalist practicing in a community setting can tell you, QI is much easier said than done.

Acknowledge, Overcome the Obstacles

One of the first hurdles hospitalists must overcome when initiating a QI program is finding the time in their schedule as well as obtaining the time commitment from group leadership and fellow clinicians.

“If a hospitalist has no dedicated time and is working clinically, it is difficult to find time to organize a study,” says Kenneth Epstein, MD, chief medical officer of Hospitalist Consultants, the hospitalist management division of ECI Healthcare Partners, in Traverse City, Mich.

However, many national hospitalist management groups, including ECI and IPC Healthcare of North Hollywood, Calif., expect their clinicians to be continuously engaged in QI projects relative to their facility.

Beyond time, an even tougher obstacle to surmount is a lack of training, according to Kerry Weiner, MD, IPC chief medical officer. He says that each of IPC’s clinical practice leaders must participate in a one-year training program that includes a QI project conducted within their facility and mentored by University of California, San Francisco faculty.

David Nash, MD, founding dean of Jefferson College of Population Health in Philadelphia, says The Joint Commission, as part of its accreditation process, requires hospitals to robustly review errors and “have a performance improvement system in place.” He believes the only way community hospitals can successfully undertake this effort is to make sure hospitalists have adequate training in quality and safety.

Training is available from SHM via its Quality and Safety Educators Academy as well as the American Association for Physician Leadership and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement. However, Dr. Nash recommends graduate-level programs in quality and safety available at several schools including Jefferson, Northwestern University in Chicago, and George Washington University in Washington, D.C.

Yet another hurdle is access to data. Many community hospitals have limited financial and human resources to collect accurate data to use for choosing an area to focus on and measuring improvement.

“Despite all the money invested in electronic medical records, finding timely and accurate data is still challenging,” says Jasen Gundersen, MD, president of Knoxville, Tenn.–based TeamHealth Acute Care Services. “The data may exist, but a community hospital may be limited when it comes to finding people to mine, configure, and analyze the data. Community hospitals tend to be focused on publically reported, whole-hospital data.

“If your project is not related to these metrics, you may have trouble getting quality department support.”

Dr. Weiner echoes that sentiment, noting most community hospitals “react to bad metrics, such as low HCAHPS scores. To get the most support possible,” he says, “design a QI program that people see as a genuine problem that needs to be fixed using their resources.”

Get Involved

Experience is another barrier to community-based QI projects. Dr. Gundersen believes that hospitalists who want to get involved in quality should first join a QI committee.

“One of the best ways to effect change in a hospital is to get to know the players—who’s who, who does what, and who is willing to help,” he says.

Arnu Mohan, MD, chief medical officer of hospital medicine at ApolloMD in Atlanta, agrees with gaining experience before setting out on your own.

“Joining a QI committee is almost never a bad idea,” Dr. Mohan says. “You’ll meet people who can support your work, get insight into the needs of the institution, be exposed to other work being done, and better understand the resources available.”

Choose Your Project Carefully

Dr. Gundersen recommends that before settling on a QI project, hospitalists should first consider what their career goals are.

“Ask yourself why you want to do it,” he says. “Do you have the ambition to become a medical director or chief quality officer? In that case, you need a few QI projects under your belt, and you want to choose a system-wide project. Or is there just something in your everyday life that frustrates you so much you must fix it?”

If the project that compels the clinician is not aligned with the needs of the hospital, “it is worthy of a discussion to make sure you are working on the right project,” he adds. “Is the hospitalist off base, or does the administration need to pay more attention to what is happening on the floor?”

Obtain Buy-in

A QI project has a greater chance at being successful if the participants have a high level of interest in the initiative and there is visible support from the administration: high-level people making public statements, making appearances at QI team meetings, and diverting resources such as information technology and process mapping support to sustain the project. This will only happen if community-based hospitalists are successful at selling their project to the C-suite.

“When you approach senior management, you have only 15 minutes to get their attention about your project,” Dr. Weiner says. “You need to show them that you are bringing part of the solution and your idea will affect their bottom line.”

Jeff Brady, MD, director of the Center for Quality Improvement and Patient Safety, says organization commitment is key to any patient safety initiative.

“In addition to the active engagement of leaders who focus on safety and quality, an organization’s culture is another factor that can either enable or thwart progress toward improving the care they deliver,” he says. “AHRQ [the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality] developed a collection of instruments—AHRQ Surveys on Patient Safety Culture—to help organizations assess and better understand facilitators and barriers their organizations may encounter as they work to improve safety and quality.”2

Politics also can be a factor. Dr. Gundersen points out that smaller hospitals typically are used to “doing things one way.”

“They may not be receptive to changes a QI program would initiate,” he says. “You have to figure out a way to enlist people to move the project forward. Your ability to drive and influence change may be your most important quality as a physician leader.”

Dr. Mohan believes that the best approach is to find a mentor who has worked on QI initiatives before and can champion your efforts.

“You will need the support of the hospital to access required data, change processes, and implement new tools,” he says. “Many hospitals will have a chief medical officer, chief quality officer, or director of QI who can serve as an important ally to mobilize resources on your behalf.”

Go Beyond Hospital Medicine

Even with administrative support, it is better to assemble a team than attempt to go it alone. Successful QI projects, Dr. Mohan says, tend to be team efforts.

“Finding a community of people who will support your work is critical,” he adds. “A multidisciplinary team, including areas such as nursing, therapy, and administration, that engages people who will complement one another increases the likelihood of success.

“That said, multidisciplinary teams have their challenges. They can be unwieldy to lead and without clear roles and responsibilities. I would recommend a group of two to five people who are passionate about the issue you are trying to solve. And be clear from the beginning what each person’s role is within the group.”

Support can also be found in areas outside of the medical staff.

“Key people in other hospital departments can assist with supplying data, financial solutions, and institutional support,” Dr. Mohan says. “These people may be in various departments, such as quality improvement and case management.

“In the current era of value-based purchasing, where Medicare reimbursement is tied to quality metrics, it’s advantageous to show potential financial impact of the QI initiative on hospital revenue, so assistance by the CFO or others in finance may be helpful.”

Dr. Gundersen suggests hospitalists seek out a “lateral mentor,” someone in a department outside the medical staff who is looking for change and can offer resources.

“For example, physicians are looking for quality improvement, and those in the finance department are looking for good economic return. Physicians can explain medical reasons things need to be done, and the finance people can explain the impact of these choices,” he says. “Working together, they can improve both quality and the bottom line.”

Lateral mentoring also is an effective way to meet the challenge of obtaining accurate data, as it opens up the potential to mine data from various departments.

“At different institutions, data may reside in different departments,” Dr. Epstein says. “For example, patient satisfaction may reside with the CMO, core measures or readmissions may reside with the quality management department, and length of stay may be the purview of the finance department.”

Connections in other departments could be the source of your best data, according to Dr. Epstein.

Consider Incentives, Penalties

In addition to buy-in from administration and professionals in other departments, hospitalists also need the commitment of fellow clinicians. Dr. Weiner believes the only way to do this is through financial incentives.

“In a community setting, start with a meaningful reward for improvement. It must be enough that the hospitalist makes the QI project a priority,” he says.

Dr. Weiner also recommends a small penalty for non-participation.

“Most providers realize QI is just good practice, but for some individuals, you need a consequence. It must be part of the system so it isn’t personal,” Dr. Weiner says. “One way is to mandate that if you do not participate, not only do you not get any of the incentive pay, you might lose some of a productivity bonus. You need to be creative when thinking about how to promote QI.”

In the community hospital setting, Dr. Weiner says, practicality ultimately rules.

“The community hospital has real problems to deal with, so don’t make your project pie-in-the-sky,” he says. “Tie it to the bottom line of the hospital if you can. That’s where you start.” TH

Maybelle Cowan-Lincoln is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Cawley P, Deitelzweig S, Flores L. The key principles and characteristics of an effective hospital medicine group: as assessment guide for hospitals and hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2014;9:123-128.

- Surveys on patient safety culture. AHRQ website. Accessed October 12, 2015.

- AHRQ Quality Indicators Toolkit for Hospitals: fact sheet. AHRQ website. Accessed October 10, 2015.

- Practice facilitation handbook. AHRQ website. Accessed on September 25, 2015.

- 5. SHM signature programs. SHM website. Accessed October 10, 2015.

The Society of Hospital Medicine asserts that one of the key principles of an effective hospital medicine group is demonstrating a commitment to continuous quality improvement (QI) and actively participating in initiatives directed at quality and patient safety.1 Large hospitalist groups expect their physicians to contribute to the QI initiatives of the hospitals they staff. But as any hospitalist practicing in a community setting can tell you, QI is much easier said than done.

Acknowledge, Overcome the Obstacles

One of the first hurdles hospitalists must overcome when initiating a QI program is finding the time in their schedule as well as obtaining the time commitment from group leadership and fellow clinicians.

“If a hospitalist has no dedicated time and is working clinically, it is difficult to find time to organize a study,” says Kenneth Epstein, MD, chief medical officer of Hospitalist Consultants, the hospitalist management division of ECI Healthcare Partners, in Traverse City, Mich.

However, many national hospitalist management groups, including ECI and IPC Healthcare of North Hollywood, Calif., expect their clinicians to be continuously engaged in QI projects relative to their facility.

Beyond time, an even tougher obstacle to surmount is a lack of training, according to Kerry Weiner, MD, IPC chief medical officer. He says that each of IPC’s clinical practice leaders must participate in a one-year training program that includes a QI project conducted within their facility and mentored by University of California, San Francisco faculty.

David Nash, MD, founding dean of Jefferson College of Population Health in Philadelphia, says The Joint Commission, as part of its accreditation process, requires hospitals to robustly review errors and “have a performance improvement system in place.” He believes the only way community hospitals can successfully undertake this effort is to make sure hospitalists have adequate training in quality and safety.

Training is available from SHM via its Quality and Safety Educators Academy as well as the American Association for Physician Leadership and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement. However, Dr. Nash recommends graduate-level programs in quality and safety available at several schools including Jefferson, Northwestern University in Chicago, and George Washington University in Washington, D.C.

Yet another hurdle is access to data. Many community hospitals have limited financial and human resources to collect accurate data to use for choosing an area to focus on and measuring improvement.

“Despite all the money invested in electronic medical records, finding timely and accurate data is still challenging,” says Jasen Gundersen, MD, president of Knoxville, Tenn.–based TeamHealth Acute Care Services. “The data may exist, but a community hospital may be limited when it comes to finding people to mine, configure, and analyze the data. Community hospitals tend to be focused on publically reported, whole-hospital data.

“If your project is not related to these metrics, you may have trouble getting quality department support.”

Dr. Weiner echoes that sentiment, noting most community hospitals “react to bad metrics, such as low HCAHPS scores. To get the most support possible,” he says, “design a QI program that people see as a genuine problem that needs to be fixed using their resources.”

Get Involved

Experience is another barrier to community-based QI projects. Dr. Gundersen believes that hospitalists who want to get involved in quality should first join a QI committee.

“One of the best ways to effect change in a hospital is to get to know the players—who’s who, who does what, and who is willing to help,” he says.

Arnu Mohan, MD, chief medical officer of hospital medicine at ApolloMD in Atlanta, agrees with gaining experience before setting out on your own.

“Joining a QI committee is almost never a bad idea,” Dr. Mohan says. “You’ll meet people who can support your work, get insight into the needs of the institution, be exposed to other work being done, and better understand the resources available.”

Choose Your Project Carefully

Dr. Gundersen recommends that before settling on a QI project, hospitalists should first consider what their career goals are.

“Ask yourself why you want to do it,” he says. “Do you have the ambition to become a medical director or chief quality officer? In that case, you need a few QI projects under your belt, and you want to choose a system-wide project. Or is there just something in your everyday life that frustrates you so much you must fix it?”

If the project that compels the clinician is not aligned with the needs of the hospital, “it is worthy of a discussion to make sure you are working on the right project,” he adds. “Is the hospitalist off base, or does the administration need to pay more attention to what is happening on the floor?”

Obtain Buy-in

A QI project has a greater chance at being successful if the participants have a high level of interest in the initiative and there is visible support from the administration: high-level people making public statements, making appearances at QI team meetings, and diverting resources such as information technology and process mapping support to sustain the project. This will only happen if community-based hospitalists are successful at selling their project to the C-suite.

“When you approach senior management, you have only 15 minutes to get their attention about your project,” Dr. Weiner says. “You need to show them that you are bringing part of the solution and your idea will affect their bottom line.”

Jeff Brady, MD, director of the Center for Quality Improvement and Patient Safety, says organization commitment is key to any patient safety initiative.

“In addition to the active engagement of leaders who focus on safety and quality, an organization’s culture is another factor that can either enable or thwart progress toward improving the care they deliver,” he says. “AHRQ [the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality] developed a collection of instruments—AHRQ Surveys on Patient Safety Culture—to help organizations assess and better understand facilitators and barriers their organizations may encounter as they work to improve safety and quality.”2

Politics also can be a factor. Dr. Gundersen points out that smaller hospitals typically are used to “doing things one way.”

“They may not be receptive to changes a QI program would initiate,” he says. “You have to figure out a way to enlist people to move the project forward. Your ability to drive and influence change may be your most important quality as a physician leader.”

Dr. Mohan believes that the best approach is to find a mentor who has worked on QI initiatives before and can champion your efforts.

“You will need the support of the hospital to access required data, change processes, and implement new tools,” he says. “Many hospitals will have a chief medical officer, chief quality officer, or director of QI who can serve as an important ally to mobilize resources on your behalf.”

Go Beyond Hospital Medicine

Even with administrative support, it is better to assemble a team than attempt to go it alone. Successful QI projects, Dr. Mohan says, tend to be team efforts.

“Finding a community of people who will support your work is critical,” he adds. “A multidisciplinary team, including areas such as nursing, therapy, and administration, that engages people who will complement one another increases the likelihood of success.

“That said, multidisciplinary teams have their challenges. They can be unwieldy to lead and without clear roles and responsibilities. I would recommend a group of two to five people who are passionate about the issue you are trying to solve. And be clear from the beginning what each person’s role is within the group.”

Support can also be found in areas outside of the medical staff.

“Key people in other hospital departments can assist with supplying data, financial solutions, and institutional support,” Dr. Mohan says. “These people may be in various departments, such as quality improvement and case management.

“In the current era of value-based purchasing, where Medicare reimbursement is tied to quality metrics, it’s advantageous to show potential financial impact of the QI initiative on hospital revenue, so assistance by the CFO or others in finance may be helpful.”

Dr. Gundersen suggests hospitalists seek out a “lateral mentor,” someone in a department outside the medical staff who is looking for change and can offer resources.

“For example, physicians are looking for quality improvement, and those in the finance department are looking for good economic return. Physicians can explain medical reasons things need to be done, and the finance people can explain the impact of these choices,” he says. “Working together, they can improve both quality and the bottom line.”

Lateral mentoring also is an effective way to meet the challenge of obtaining accurate data, as it opens up the potential to mine data from various departments.

“At different institutions, data may reside in different departments,” Dr. Epstein says. “For example, patient satisfaction may reside with the CMO, core measures or readmissions may reside with the quality management department, and length of stay may be the purview of the finance department.”

Connections in other departments could be the source of your best data, according to Dr. Epstein.

Consider Incentives, Penalties

In addition to buy-in from administration and professionals in other departments, hospitalists also need the commitment of fellow clinicians. Dr. Weiner believes the only way to do this is through financial incentives.

“In a community setting, start with a meaningful reward for improvement. It must be enough that the hospitalist makes the QI project a priority,” he says.

Dr. Weiner also recommends a small penalty for non-participation.

“Most providers realize QI is just good practice, but for some individuals, you need a consequence. It must be part of the system so it isn’t personal,” Dr. Weiner says. “One way is to mandate that if you do not participate, not only do you not get any of the incentive pay, you might lose some of a productivity bonus. You need to be creative when thinking about how to promote QI.”

In the community hospital setting, Dr. Weiner says, practicality ultimately rules.

“The community hospital has real problems to deal with, so don’t make your project pie-in-the-sky,” he says. “Tie it to the bottom line of the hospital if you can. That’s where you start.” TH

Maybelle Cowan-Lincoln is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Cawley P, Deitelzweig S, Flores L. The key principles and characteristics of an effective hospital medicine group: as assessment guide for hospitals and hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2014;9:123-128.

- Surveys on patient safety culture. AHRQ website. Accessed October 12, 2015.

- AHRQ Quality Indicators Toolkit for Hospitals: fact sheet. AHRQ website. Accessed October 10, 2015.

- Practice facilitation handbook. AHRQ website. Accessed on September 25, 2015.

- 5. SHM signature programs. SHM website. Accessed October 10, 2015.

The Society of Hospital Medicine asserts that one of the key principles of an effective hospital medicine group is demonstrating a commitment to continuous quality improvement (QI) and actively participating in initiatives directed at quality and patient safety.1 Large hospitalist groups expect their physicians to contribute to the QI initiatives of the hospitals they staff. But as any hospitalist practicing in a community setting can tell you, QI is much easier said than done.

Acknowledge, Overcome the Obstacles

One of the first hurdles hospitalists must overcome when initiating a QI program is finding the time in their schedule as well as obtaining the time commitment from group leadership and fellow clinicians.

“If a hospitalist has no dedicated time and is working clinically, it is difficult to find time to organize a study,” says Kenneth Epstein, MD, chief medical officer of Hospitalist Consultants, the hospitalist management division of ECI Healthcare Partners, in Traverse City, Mich.

However, many national hospitalist management groups, including ECI and IPC Healthcare of North Hollywood, Calif., expect their clinicians to be continuously engaged in QI projects relative to their facility.

Beyond time, an even tougher obstacle to surmount is a lack of training, according to Kerry Weiner, MD, IPC chief medical officer. He says that each of IPC’s clinical practice leaders must participate in a one-year training program that includes a QI project conducted within their facility and mentored by University of California, San Francisco faculty.

David Nash, MD, founding dean of Jefferson College of Population Health in Philadelphia, says The Joint Commission, as part of its accreditation process, requires hospitals to robustly review errors and “have a performance improvement system in place.” He believes the only way community hospitals can successfully undertake this effort is to make sure hospitalists have adequate training in quality and safety.

Training is available from SHM via its Quality and Safety Educators Academy as well as the American Association for Physician Leadership and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement. However, Dr. Nash recommends graduate-level programs in quality and safety available at several schools including Jefferson, Northwestern University in Chicago, and George Washington University in Washington, D.C.

Yet another hurdle is access to data. Many community hospitals have limited financial and human resources to collect accurate data to use for choosing an area to focus on and measuring improvement.

“Despite all the money invested in electronic medical records, finding timely and accurate data is still challenging,” says Jasen Gundersen, MD, president of Knoxville, Tenn.–based TeamHealth Acute Care Services. “The data may exist, but a community hospital may be limited when it comes to finding people to mine, configure, and analyze the data. Community hospitals tend to be focused on publically reported, whole-hospital data.

“If your project is not related to these metrics, you may have trouble getting quality department support.”

Dr. Weiner echoes that sentiment, noting most community hospitals “react to bad metrics, such as low HCAHPS scores. To get the most support possible,” he says, “design a QI program that people see as a genuine problem that needs to be fixed using their resources.”

Get Involved

Experience is another barrier to community-based QI projects. Dr. Gundersen believes that hospitalists who want to get involved in quality should first join a QI committee.

“One of the best ways to effect change in a hospital is to get to know the players—who’s who, who does what, and who is willing to help,” he says.

Arnu Mohan, MD, chief medical officer of hospital medicine at ApolloMD in Atlanta, agrees with gaining experience before setting out on your own.

“Joining a QI committee is almost never a bad idea,” Dr. Mohan says. “You’ll meet people who can support your work, get insight into the needs of the institution, be exposed to other work being done, and better understand the resources available.”

Choose Your Project Carefully

Dr. Gundersen recommends that before settling on a QI project, hospitalists should first consider what their career goals are.

“Ask yourself why you want to do it,” he says. “Do you have the ambition to become a medical director or chief quality officer? In that case, you need a few QI projects under your belt, and you want to choose a system-wide project. Or is there just something in your everyday life that frustrates you so much you must fix it?”

If the project that compels the clinician is not aligned with the needs of the hospital, “it is worthy of a discussion to make sure you are working on the right project,” he adds. “Is the hospitalist off base, or does the administration need to pay more attention to what is happening on the floor?”

Obtain Buy-in

A QI project has a greater chance at being successful if the participants have a high level of interest in the initiative and there is visible support from the administration: high-level people making public statements, making appearances at QI team meetings, and diverting resources such as information technology and process mapping support to sustain the project. This will only happen if community-based hospitalists are successful at selling their project to the C-suite.

“When you approach senior management, you have only 15 minutes to get their attention about your project,” Dr. Weiner says. “You need to show them that you are bringing part of the solution and your idea will affect their bottom line.”

Jeff Brady, MD, director of the Center for Quality Improvement and Patient Safety, says organization commitment is key to any patient safety initiative.

“In addition to the active engagement of leaders who focus on safety and quality, an organization’s culture is another factor that can either enable or thwart progress toward improving the care they deliver,” he says. “AHRQ [the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality] developed a collection of instruments—AHRQ Surveys on Patient Safety Culture—to help organizations assess and better understand facilitators and barriers their organizations may encounter as they work to improve safety and quality.”2

Politics also can be a factor. Dr. Gundersen points out that smaller hospitals typically are used to “doing things one way.”

“They may not be receptive to changes a QI program would initiate,” he says. “You have to figure out a way to enlist people to move the project forward. Your ability to drive and influence change may be your most important quality as a physician leader.”

Dr. Mohan believes that the best approach is to find a mentor who has worked on QI initiatives before and can champion your efforts.

“You will need the support of the hospital to access required data, change processes, and implement new tools,” he says. “Many hospitals will have a chief medical officer, chief quality officer, or director of QI who can serve as an important ally to mobilize resources on your behalf.”

Go Beyond Hospital Medicine

Even with administrative support, it is better to assemble a team than attempt to go it alone. Successful QI projects, Dr. Mohan says, tend to be team efforts.

“Finding a community of people who will support your work is critical,” he adds. “A multidisciplinary team, including areas such as nursing, therapy, and administration, that engages people who will complement one another increases the likelihood of success.

“That said, multidisciplinary teams have their challenges. They can be unwieldy to lead and without clear roles and responsibilities. I would recommend a group of two to five people who are passionate about the issue you are trying to solve. And be clear from the beginning what each person’s role is within the group.”

Support can also be found in areas outside of the medical staff.

“Key people in other hospital departments can assist with supplying data, financial solutions, and institutional support,” Dr. Mohan says. “These people may be in various departments, such as quality improvement and case management.

“In the current era of value-based purchasing, where Medicare reimbursement is tied to quality metrics, it’s advantageous to show potential financial impact of the QI initiative on hospital revenue, so assistance by the CFO or others in finance may be helpful.”

Dr. Gundersen suggests hospitalists seek out a “lateral mentor,” someone in a department outside the medical staff who is looking for change and can offer resources.

“For example, physicians are looking for quality improvement, and those in the finance department are looking for good economic return. Physicians can explain medical reasons things need to be done, and the finance people can explain the impact of these choices,” he says. “Working together, they can improve both quality and the bottom line.”

Lateral mentoring also is an effective way to meet the challenge of obtaining accurate data, as it opens up the potential to mine data from various departments.

“At different institutions, data may reside in different departments,” Dr. Epstein says. “For example, patient satisfaction may reside with the CMO, core measures or readmissions may reside with the quality management department, and length of stay may be the purview of the finance department.”

Connections in other departments could be the source of your best data, according to Dr. Epstein.

Consider Incentives, Penalties

In addition to buy-in from administration and professionals in other departments, hospitalists also need the commitment of fellow clinicians. Dr. Weiner believes the only way to do this is through financial incentives.

“In a community setting, start with a meaningful reward for improvement. It must be enough that the hospitalist makes the QI project a priority,” he says.

Dr. Weiner also recommends a small penalty for non-participation.

“Most providers realize QI is just good practice, but for some individuals, you need a consequence. It must be part of the system so it isn’t personal,” Dr. Weiner says. “One way is to mandate that if you do not participate, not only do you not get any of the incentive pay, you might lose some of a productivity bonus. You need to be creative when thinking about how to promote QI.”

In the community hospital setting, Dr. Weiner says, practicality ultimately rules.

“The community hospital has real problems to deal with, so don’t make your project pie-in-the-sky,” he says. “Tie it to the bottom line of the hospital if you can. That’s where you start.” TH

Maybelle Cowan-Lincoln is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Cawley P, Deitelzweig S, Flores L. The key principles and characteristics of an effective hospital medicine group: as assessment guide for hospitals and hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2014;9:123-128.

- Surveys on patient safety culture. AHRQ website. Accessed October 12, 2015.

- AHRQ Quality Indicators Toolkit for Hospitals: fact sheet. AHRQ website. Accessed October 10, 2015.

- Practice facilitation handbook. AHRQ website. Accessed on September 25, 2015.

- 5. SHM signature programs. SHM website. Accessed October 10, 2015.

Communication Crossroads: Managing Patient Interactions, Online Personas on Social Media

The pitfalls that can complicate the intersection of social media and patient privacy often come as no surprise when they arise, but digital communications, and social media sites in particular, also have made many positive contributions to the medical profession.

“Social media allows physicians to communicate with each other, to publicize items of interest, to solicit input from colleagues—even people that we don’t know—on a variety of topics,” says Brian Clay, MD, SFHM, interim chief medical informatics officer and associate program director of the internal medicine residency-training program at the University of California at San Diego.

But there is a dark side of social media, too, and some physicians have made significant missteps in social media use. Ryan Greysen, MD, MHS, FHM, assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California at San Francisco, has authored multiple studies on physician violations of online professionalism. In a report published in the March 2012 issue of JAMA, Dr. Greysen and co-authors note that 92% of the executive directors at state medical and osteopathic boards surveyed reported encountering at least one violation of online professionalism.3 Another report in the January 2013 issue of the Annals of Internal Medicine co-authored by Dr. Greysen notes that 71% of state medical boards have investigated physicians for violations of professionalism online.4 The consequences of these errors in judgment can be dire: Should your employer come across it or a colleague report it, you could lose your position and even lose your license.

Professional Guidelines

To avoid these significant and potentially career-ending blunders, the American College of Physicians (ACP)—in conjunction with the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB)—published recommendations offering ethical guidance in preserving the patient-physician relationship in context of social media.5 Similarly, the American Medical Association (AMA) published an opinion on professionalism in the use of social media.6 Their guidelines can be summarized in five succinct points.

- Maintain standards of professional ethics in online communications, including respect for patient privacy.

Katherine Chretien, MD, associate professor of medicine at George Washington University in Washington, D.C., a clinical associate professor in medicine at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Md., and chief of the hospitalist section at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center also in Washington, D.C., warns physicians to use the utmost caution to maintain patient anonymity when publishing case stories online. When publishing clinical vignettes, physician blogs, and other forms of online media, all details that can identify a patient must be completely removed, including all forms of the date (references to “yesterday” or “last week,” for example, can identify the date). Check anything you intend to publish against the HIPPA list of 18 identifiers.7 (See “HIPPA Identifiers” below)

“The safest way to proceed when publishing patient narratives online is to get consent,” Dr. Chretien says. “If consent is not possible, as in cases of incidents that occurred several years ago, change the personal details, such as location, and clearly disclose that you have. Or make the example very general.” For example, instead of discussing how frustrated you became with a patient with asthma who you saw at a particular hospital in a certain year (a clear violation of patient privacy), paint the illustration in broad strokes. Dr. Chretien suggests you might phrase your observations in this way: “One of the frustrations I find when treating asthma patients is …”

It would also be wise to seek advice from colleagues before posting patient information, she notes.

- Do not blur the boundaries between your professional and social spheres.

In a 2011 study, Gabriel Bosslet, MD, assistant professor of clinical medicine and associate director of the fellowship in pulmonary and critical care medicine at Indiana University–Purdue University at Indianapolis, noted that 34% of participating physicians reported receiving a Facebook friend request from a patient or patient’s family member. As Dr. Chretien points out, this is less of a problem for hospitalists than private-practice physicians because the relationship with patients is transitory. The AMA, as well as the ACP and FSMB, note that physicians should not “friend” patients, accept friend requests, or contact patients through social media. Physicians are advised to keep their public and professional online personas separate, even to the point of creating distinct online identities for their personal and professional lives.

- Maintain professionalism in your online persona, and continually monitor your online image to ensure it reflects positively on yourself and the medical profession.

Some physicians fall into the trap of placing questionable postings on their personal pages, including posting content that can be inappropriate for public consumption or venting about patients and employers. Stories or incidents that medical professionals find intriguing or exciting may be disturbing to those outside their community, and medical humor can be offensive.

“[Physicians] assume [their social media page] is their personal space, so they can post whatever they want,” adds Dr. Chretien. “Part of their error is that they believe they are addressing a small group of close friends, but they forget that postings go out to the larger, peripheral audience of all Facebook friends and can often be accessed by the general public.” An ill-considered anecdote can damage not only your own reputation but also the overall perception of the profession. Physicians are always viewed in their professional role, even in social interactions.

- Use email and other forms of electronic communication only in cases of an established physician-patient relationship and only with informed patient consent. Documentation of these communications should be kept in the patient’s medical record.

Any request a physician receives for medical advice through a social media site or email must be handled with caution. The ACP and FSMB state that email and text communications with established patients can be beneficial but should occur only after both parties discuss privacy risks, the appropriate types of information that will be exchanged electronically, and how long patients should expect to wait for a physician response. Patient preference should guide the use of electronic communication with physicians, especially text messaging, says Dr. Greysen.

- Be aware that any postings on the Internet, because of its significant and unprecedented reach, can have future career ramifications. Consequently, physicians are advised to frequently monitor their online presence to control their image.

Dr. Greysen points out that presenting a positive image of physicians in the media is not a new challenge. “Physicians have been publishing books about their experiences for decades. But posting online without oversight, or in the moment without reflection, can be devastating to a physician’s career because the reach of the Internet is exponentially vaster than that of any printed material,” Dr. Greysen says.

Deliver Better Healthcare through Social Media

Perhaps one of the most dramatic ways in which social media is positively impacting healthcare is the FOAM movement, or free open access medical education. Jeanne Farnan, MD, associate professor of medicine at the University of Chicago Department of Medicine and lead author of the ACP and FSMB social media position paper, points to the dynamic collection of resources and tools for ongoing medical education as well as the community that participates in openly sharing knowledge as examples. FOAM resources are predominantly social media based and include blogs, podcasts, tweets, online videos, graphics, web-based applications, text documents, and photographs, many of which are available by following the Twitter feed @FOAMed (see “FOAM Links” below). This FOAM community is dedicated to the belief that high-quality medical education resources and interactions should be free and accessible to all who care for patients and especially to those who educate future physicians.8

Social media also affords physicians the opportunity to be a force in public health policies. “There is an active group of physician and medical student social media users in the blogosphere and on Twitter who use their social media presence for activism, and this presence is intimately tied to how they see themselves as a medical professional,” Dr. Farnan says. “They blog and tweet about medical education issues and other public topics such as access to care and care disparity.”

Michelle Vangel, director of insight services with Cision, a Chicago-based public relations company specializing in social media communications, praises the power of social media for raising awareness of public health issues.

“In terms of public health, social media is valuable to better understand how health-related news resonates with the public,” Vangel says. “Two salient examples of major health crises reactions tracked on social media were the Ebola outbreak in Africa and the measles outbreak at Disneyland in California. At times, there was near hysteria over Ebola and vaccine debates, with misinformation spreading quickly. However, many hospitals and physicians tried to get ahead of the hysteria by providing concise, accurate information on different social media platforms, with Facebook often a popular channel to post information.”

Social media sites can also help by making emotional support available at disease-specific sites. These communities address the patient experience of the disease that goes beyond purely medical disease information. Vangel points to several online communities that “host pivotal conversations for patients,” she says. “There are Facebook community pages dedicated to a host of conditions, including diabetes, hypertension, and cystic fibrosis, where patients discuss the challenges of medication compliance, side effects, and even dissatisfaction with healthcare professionals. BabyCenter.com provides message boards about a wide array of topics for people trying to conceive, pregnant women with health conditions, and parents of babies with health issues. CancerForums.net and the health and wellness boards at DelphiForums.com provide support to specific disease populations.”

Vangel encourages physicians to monitor online patient-support sites to better understand the difficulties patients experience while under treatment. These sites can also help physicians recognize and address the gaps in patient understanding about various diseases and explore programs geared toward the populations suffering from a wide range of conditions. TH

Maybelle Cowan-Lincoln is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Photos of drinking, grinning aid mission doctors cause uproar. CNN website. Accessed December 2, 2015.

- Terhune C. Hospital violated patient confidentiality, state says. Los Angeles Times website. Accessed December 3, 2015.

- Greysen SR, Chretien KC, Kind T, Young A, Gross CP. Physician violations of online professionalism and disciplinary actions: a national survey of state medical boards. JAMA. 2012;(307):1141-1142.

- Greysen SR, Johnson D, Kind T, et al. Online professional investigations by state medical boards: first, do no harm. Ann Intern Med. 2013;(158):124-130.

- New recommendations offer physicians ethical guidance for preserving trust in patient-physician relationships and the profession when using social media. American College of Physicians website. Accessed July 3, 2015.

- Opinion 9.124—professionalism in the use of social media. American Medical Association website. Accessed July 3, 2015.

- HIPPA PHI: list of 18 identifiers and definition of PHI. The Committee for Protection of Human Subjects website. Accessed July 10, 2015.

- FOAM. Life in the Fastlane website. Accessed September 6, 2015.

The pitfalls that can complicate the intersection of social media and patient privacy often come as no surprise when they arise, but digital communications, and social media sites in particular, also have made many positive contributions to the medical profession.

“Social media allows physicians to communicate with each other, to publicize items of interest, to solicit input from colleagues—even people that we don’t know—on a variety of topics,” says Brian Clay, MD, SFHM, interim chief medical informatics officer and associate program director of the internal medicine residency-training program at the University of California at San Diego.

But there is a dark side of social media, too, and some physicians have made significant missteps in social media use. Ryan Greysen, MD, MHS, FHM, assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California at San Francisco, has authored multiple studies on physician violations of online professionalism. In a report published in the March 2012 issue of JAMA, Dr. Greysen and co-authors note that 92% of the executive directors at state medical and osteopathic boards surveyed reported encountering at least one violation of online professionalism.3 Another report in the January 2013 issue of the Annals of Internal Medicine co-authored by Dr. Greysen notes that 71% of state medical boards have investigated physicians for violations of professionalism online.4 The consequences of these errors in judgment can be dire: Should your employer come across it or a colleague report it, you could lose your position and even lose your license.

Professional Guidelines

To avoid these significant and potentially career-ending blunders, the American College of Physicians (ACP)—in conjunction with the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB)—published recommendations offering ethical guidance in preserving the patient-physician relationship in context of social media.5 Similarly, the American Medical Association (AMA) published an opinion on professionalism in the use of social media.6 Their guidelines can be summarized in five succinct points.

- Maintain standards of professional ethics in online communications, including respect for patient privacy.

Katherine Chretien, MD, associate professor of medicine at George Washington University in Washington, D.C., a clinical associate professor in medicine at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Md., and chief of the hospitalist section at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center also in Washington, D.C., warns physicians to use the utmost caution to maintain patient anonymity when publishing case stories online. When publishing clinical vignettes, physician blogs, and other forms of online media, all details that can identify a patient must be completely removed, including all forms of the date (references to “yesterday” or “last week,” for example, can identify the date). Check anything you intend to publish against the HIPPA list of 18 identifiers.7 (See “HIPPA Identifiers” below)

“The safest way to proceed when publishing patient narratives online is to get consent,” Dr. Chretien says. “If consent is not possible, as in cases of incidents that occurred several years ago, change the personal details, such as location, and clearly disclose that you have. Or make the example very general.” For example, instead of discussing how frustrated you became with a patient with asthma who you saw at a particular hospital in a certain year (a clear violation of patient privacy), paint the illustration in broad strokes. Dr. Chretien suggests you might phrase your observations in this way: “One of the frustrations I find when treating asthma patients is …”

It would also be wise to seek advice from colleagues before posting patient information, she notes.

- Do not blur the boundaries between your professional and social spheres.

In a 2011 study, Gabriel Bosslet, MD, assistant professor of clinical medicine and associate director of the fellowship in pulmonary and critical care medicine at Indiana University–Purdue University at Indianapolis, noted that 34% of participating physicians reported receiving a Facebook friend request from a patient or patient’s family member. As Dr. Chretien points out, this is less of a problem for hospitalists than private-practice physicians because the relationship with patients is transitory. The AMA, as well as the ACP and FSMB, note that physicians should not “friend” patients, accept friend requests, or contact patients through social media. Physicians are advised to keep their public and professional online personas separate, even to the point of creating distinct online identities for their personal and professional lives.

- Maintain professionalism in your online persona, and continually monitor your online image to ensure it reflects positively on yourself and the medical profession.

Some physicians fall into the trap of placing questionable postings on their personal pages, including posting content that can be inappropriate for public consumption or venting about patients and employers. Stories or incidents that medical professionals find intriguing or exciting may be disturbing to those outside their community, and medical humor can be offensive.

“[Physicians] assume [their social media page] is their personal space, so they can post whatever they want,” adds Dr. Chretien. “Part of their error is that they believe they are addressing a small group of close friends, but they forget that postings go out to the larger, peripheral audience of all Facebook friends and can often be accessed by the general public.” An ill-considered anecdote can damage not only your own reputation but also the overall perception of the profession. Physicians are always viewed in their professional role, even in social interactions.

- Use email and other forms of electronic communication only in cases of an established physician-patient relationship and only with informed patient consent. Documentation of these communications should be kept in the patient’s medical record.

Any request a physician receives for medical advice through a social media site or email must be handled with caution. The ACP and FSMB state that email and text communications with established patients can be beneficial but should occur only after both parties discuss privacy risks, the appropriate types of information that will be exchanged electronically, and how long patients should expect to wait for a physician response. Patient preference should guide the use of electronic communication with physicians, especially text messaging, says Dr. Greysen.

- Be aware that any postings on the Internet, because of its significant and unprecedented reach, can have future career ramifications. Consequently, physicians are advised to frequently monitor their online presence to control their image.

Dr. Greysen points out that presenting a positive image of physicians in the media is not a new challenge. “Physicians have been publishing books about their experiences for decades. But posting online without oversight, or in the moment without reflection, can be devastating to a physician’s career because the reach of the Internet is exponentially vaster than that of any printed material,” Dr. Greysen says.

Deliver Better Healthcare through Social Media

Perhaps one of the most dramatic ways in which social media is positively impacting healthcare is the FOAM movement, or free open access medical education. Jeanne Farnan, MD, associate professor of medicine at the University of Chicago Department of Medicine and lead author of the ACP and FSMB social media position paper, points to the dynamic collection of resources and tools for ongoing medical education as well as the community that participates in openly sharing knowledge as examples. FOAM resources are predominantly social media based and include blogs, podcasts, tweets, online videos, graphics, web-based applications, text documents, and photographs, many of which are available by following the Twitter feed @FOAMed (see “FOAM Links” below). This FOAM community is dedicated to the belief that high-quality medical education resources and interactions should be free and accessible to all who care for patients and especially to those who educate future physicians.8

Social media also affords physicians the opportunity to be a force in public health policies. “There is an active group of physician and medical student social media users in the blogosphere and on Twitter who use their social media presence for activism, and this presence is intimately tied to how they see themselves as a medical professional,” Dr. Farnan says. “They blog and tweet about medical education issues and other public topics such as access to care and care disparity.”

Michelle Vangel, director of insight services with Cision, a Chicago-based public relations company specializing in social media communications, praises the power of social media for raising awareness of public health issues.

“In terms of public health, social media is valuable to better understand how health-related news resonates with the public,” Vangel says. “Two salient examples of major health crises reactions tracked on social media were the Ebola outbreak in Africa and the measles outbreak at Disneyland in California. At times, there was near hysteria over Ebola and vaccine debates, with misinformation spreading quickly. However, many hospitals and physicians tried to get ahead of the hysteria by providing concise, accurate information on different social media platforms, with Facebook often a popular channel to post information.”

Social media sites can also help by making emotional support available at disease-specific sites. These communities address the patient experience of the disease that goes beyond purely medical disease information. Vangel points to several online communities that “host pivotal conversations for patients,” she says. “There are Facebook community pages dedicated to a host of conditions, including diabetes, hypertension, and cystic fibrosis, where patients discuss the challenges of medication compliance, side effects, and even dissatisfaction with healthcare professionals. BabyCenter.com provides message boards about a wide array of topics for people trying to conceive, pregnant women with health conditions, and parents of babies with health issues. CancerForums.net and the health and wellness boards at DelphiForums.com provide support to specific disease populations.”

Vangel encourages physicians to monitor online patient-support sites to better understand the difficulties patients experience while under treatment. These sites can also help physicians recognize and address the gaps in patient understanding about various diseases and explore programs geared toward the populations suffering from a wide range of conditions. TH

Maybelle Cowan-Lincoln is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Photos of drinking, grinning aid mission doctors cause uproar. CNN website. Accessed December 2, 2015.

- Terhune C. Hospital violated patient confidentiality, state says. Los Angeles Times website. Accessed December 3, 2015.

- Greysen SR, Chretien KC, Kind T, Young A, Gross CP. Physician violations of online professionalism and disciplinary actions: a national survey of state medical boards. JAMA. 2012;(307):1141-1142.

- Greysen SR, Johnson D, Kind T, et al. Online professional investigations by state medical boards: first, do no harm. Ann Intern Med. 2013;(158):124-130.

- New recommendations offer physicians ethical guidance for preserving trust in patient-physician relationships and the profession when using social media. American College of Physicians website. Accessed July 3, 2015.

- Opinion 9.124—professionalism in the use of social media. American Medical Association website. Accessed July 3, 2015.

- HIPPA PHI: list of 18 identifiers and definition of PHI. The Committee for Protection of Human Subjects website. Accessed July 10, 2015.

- FOAM. Life in the Fastlane website. Accessed September 6, 2015.

The pitfalls that can complicate the intersection of social media and patient privacy often come as no surprise when they arise, but digital communications, and social media sites in particular, also have made many positive contributions to the medical profession.

“Social media allows physicians to communicate with each other, to publicize items of interest, to solicit input from colleagues—even people that we don’t know—on a variety of topics,” says Brian Clay, MD, SFHM, interim chief medical informatics officer and associate program director of the internal medicine residency-training program at the University of California at San Diego.

But there is a dark side of social media, too, and some physicians have made significant missteps in social media use. Ryan Greysen, MD, MHS, FHM, assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California at San Francisco, has authored multiple studies on physician violations of online professionalism. In a report published in the March 2012 issue of JAMA, Dr. Greysen and co-authors note that 92% of the executive directors at state medical and osteopathic boards surveyed reported encountering at least one violation of online professionalism.3 Another report in the January 2013 issue of the Annals of Internal Medicine co-authored by Dr. Greysen notes that 71% of state medical boards have investigated physicians for violations of professionalism online.4 The consequences of these errors in judgment can be dire: Should your employer come across it or a colleague report it, you could lose your position and even lose your license.

Professional Guidelines

To avoid these significant and potentially career-ending blunders, the American College of Physicians (ACP)—in conjunction with the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB)—published recommendations offering ethical guidance in preserving the patient-physician relationship in context of social media.5 Similarly, the American Medical Association (AMA) published an opinion on professionalism in the use of social media.6 Their guidelines can be summarized in five succinct points.

- Maintain standards of professional ethics in online communications, including respect for patient privacy.

Katherine Chretien, MD, associate professor of medicine at George Washington University in Washington, D.C., a clinical associate professor in medicine at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Md., and chief of the hospitalist section at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center also in Washington, D.C., warns physicians to use the utmost caution to maintain patient anonymity when publishing case stories online. When publishing clinical vignettes, physician blogs, and other forms of online media, all details that can identify a patient must be completely removed, including all forms of the date (references to “yesterday” or “last week,” for example, can identify the date). Check anything you intend to publish against the HIPPA list of 18 identifiers.7 (See “HIPPA Identifiers” below)

“The safest way to proceed when publishing patient narratives online is to get consent,” Dr. Chretien says. “If consent is not possible, as in cases of incidents that occurred several years ago, change the personal details, such as location, and clearly disclose that you have. Or make the example very general.” For example, instead of discussing how frustrated you became with a patient with asthma who you saw at a particular hospital in a certain year (a clear violation of patient privacy), paint the illustration in broad strokes. Dr. Chretien suggests you might phrase your observations in this way: “One of the frustrations I find when treating asthma patients is …”

It would also be wise to seek advice from colleagues before posting patient information, she notes.

- Do not blur the boundaries between your professional and social spheres.

In a 2011 study, Gabriel Bosslet, MD, assistant professor of clinical medicine and associate director of the fellowship in pulmonary and critical care medicine at Indiana University–Purdue University at Indianapolis, noted that 34% of participating physicians reported receiving a Facebook friend request from a patient or patient’s family member. As Dr. Chretien points out, this is less of a problem for hospitalists than private-practice physicians because the relationship with patients is transitory. The AMA, as well as the ACP and FSMB, note that physicians should not “friend” patients, accept friend requests, or contact patients through social media. Physicians are advised to keep their public and professional online personas separate, even to the point of creating distinct online identities for their personal and professional lives.

- Maintain professionalism in your online persona, and continually monitor your online image to ensure it reflects positively on yourself and the medical profession.

Some physicians fall into the trap of placing questionable postings on their personal pages, including posting content that can be inappropriate for public consumption or venting about patients and employers. Stories or incidents that medical professionals find intriguing or exciting may be disturbing to those outside their community, and medical humor can be offensive.

“[Physicians] assume [their social media page] is their personal space, so they can post whatever they want,” adds Dr. Chretien. “Part of their error is that they believe they are addressing a small group of close friends, but they forget that postings go out to the larger, peripheral audience of all Facebook friends and can often be accessed by the general public.” An ill-considered anecdote can damage not only your own reputation but also the overall perception of the profession. Physicians are always viewed in their professional role, even in social interactions.

- Use email and other forms of electronic communication only in cases of an established physician-patient relationship and only with informed patient consent. Documentation of these communications should be kept in the patient’s medical record.

Any request a physician receives for medical advice through a social media site or email must be handled with caution. The ACP and FSMB state that email and text communications with established patients can be beneficial but should occur only after both parties discuss privacy risks, the appropriate types of information that will be exchanged electronically, and how long patients should expect to wait for a physician response. Patient preference should guide the use of electronic communication with physicians, especially text messaging, says Dr. Greysen.

- Be aware that any postings on the Internet, because of its significant and unprecedented reach, can have future career ramifications. Consequently, physicians are advised to frequently monitor their online presence to control their image.

Dr. Greysen points out that presenting a positive image of physicians in the media is not a new challenge. “Physicians have been publishing books about their experiences for decades. But posting online without oversight, or in the moment without reflection, can be devastating to a physician’s career because the reach of the Internet is exponentially vaster than that of any printed material,” Dr. Greysen says.

Deliver Better Healthcare through Social Media

Perhaps one of the most dramatic ways in which social media is positively impacting healthcare is the FOAM movement, or free open access medical education. Jeanne Farnan, MD, associate professor of medicine at the University of Chicago Department of Medicine and lead author of the ACP and FSMB social media position paper, points to the dynamic collection of resources and tools for ongoing medical education as well as the community that participates in openly sharing knowledge as examples. FOAM resources are predominantly social media based and include blogs, podcasts, tweets, online videos, graphics, web-based applications, text documents, and photographs, many of which are available by following the Twitter feed @FOAMed (see “FOAM Links” below). This FOAM community is dedicated to the belief that high-quality medical education resources and interactions should be free and accessible to all who care for patients and especially to those who educate future physicians.8

Social media also affords physicians the opportunity to be a force in public health policies. “There is an active group of physician and medical student social media users in the blogosphere and on Twitter who use their social media presence for activism, and this presence is intimately tied to how they see themselves as a medical professional,” Dr. Farnan says. “They blog and tweet about medical education issues and other public topics such as access to care and care disparity.”

Michelle Vangel, director of insight services with Cision, a Chicago-based public relations company specializing in social media communications, praises the power of social media for raising awareness of public health issues.

“In terms of public health, social media is valuable to better understand how health-related news resonates with the public,” Vangel says. “Two salient examples of major health crises reactions tracked on social media were the Ebola outbreak in Africa and the measles outbreak at Disneyland in California. At times, there was near hysteria over Ebola and vaccine debates, with misinformation spreading quickly. However, many hospitals and physicians tried to get ahead of the hysteria by providing concise, accurate information on different social media platforms, with Facebook often a popular channel to post information.”

Social media sites can also help by making emotional support available at disease-specific sites. These communities address the patient experience of the disease that goes beyond purely medical disease information. Vangel points to several online communities that “host pivotal conversations for patients,” she says. “There are Facebook community pages dedicated to a host of conditions, including diabetes, hypertension, and cystic fibrosis, where patients discuss the challenges of medication compliance, side effects, and even dissatisfaction with healthcare professionals. BabyCenter.com provides message boards about a wide array of topics for people trying to conceive, pregnant women with health conditions, and parents of babies with health issues. CancerForums.net and the health and wellness boards at DelphiForums.com provide support to specific disease populations.”

Vangel encourages physicians to monitor online patient-support sites to better understand the difficulties patients experience while under treatment. These sites can also help physicians recognize and address the gaps in patient understanding about various diseases and explore programs geared toward the populations suffering from a wide range of conditions. TH

Maybelle Cowan-Lincoln is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Photos of drinking, grinning aid mission doctors cause uproar. CNN website. Accessed December 2, 2015.

- Terhune C. Hospital violated patient confidentiality, state says. Los Angeles Times website. Accessed December 3, 2015.

- Greysen SR, Chretien KC, Kind T, Young A, Gross CP. Physician violations of online professionalism and disciplinary actions: a national survey of state medical boards. JAMA. 2012;(307):1141-1142.

- Greysen SR, Johnson D, Kind T, et al. Online professional investigations by state medical boards: first, do no harm. Ann Intern Med. 2013;(158):124-130.

- New recommendations offer physicians ethical guidance for preserving trust in patient-physician relationships and the profession when using social media. American College of Physicians website. Accessed July 3, 2015.

- Opinion 9.124—professionalism in the use of social media. American Medical Association website. Accessed July 3, 2015.

- HIPPA PHI: list of 18 identifiers and definition of PHI. The Committee for Protection of Human Subjects website. Accessed July 10, 2015.

- FOAM. Life in the Fastlane website. Accessed September 6, 2015.

10 Things Geriatricians Want Hospitalists to Know

How many octogenarians do you treat in a year? Nonagenarians? Centenarians? How much have their numbers increased over the last two decades? In the wake of the fabled “silver tsunami,” more than 40% of adult inpatients are aged 65 years or older. By 2030, more than 70 million Americans will have joined the ranks of senior citizens.

Members of this group often have multiple chronic conditions that may require hospitalization as many as 10 times per year.1 Others appear in the ED after falls or suffering from cardiovascular conditions or infection.2

The Hospitalist surveyed seasoned geriatricians for their advice on treating this highly specialized and rapidly growing population, and compiled a list of 10 things these specialists believe hospitalists should know.

1 All physicians should be educated in the basics of geriatric care.

Wayne McCormick, MD, MPH, a geriatrician on the Inpatient Palliative and Supportive Care Consultation Team at Harborview Medical Center, Seattle, notes that with the explosion of the aging population in the U.S., it is impossible to train enough geriatricians to care for every elderly hospital inpatient, so hospitalists need to increase their knowledge base of geriatric issues.

“To ensure that elderly patients receive good care suited to their specific needs, there need to be 10 times as many geriatrics-savvy internal medicine physicians as board-certified geriatricians,”Dr. McCormick says. “That way, elderly patients can find good primary, if not specialized, geriatric care.”

Dr. McCormick recommends the resources of the American Geriatrics Society, which includes fellowships on geriatric issues, conferences, and educational material on its website.

2 Sometimes the disease is not the most important focus—maintaining the patient’s function is.

Kenneth Covinsky, MD, MPH, division of geriatrics, University of California, San Francisco, says that, many times, geriatric patients are “admitted for pneumonia or heart failure, and, during their stay, the condition improves; however, the person who came in walking and able to perform activities of daily living on their own leaves unable to function.”

It is easy to see how hospital stays work against maintaining function in the elderly. An important part of maintaining function is encouraging mobility, but, according to Melissa Mattison, MD, SFHM, FACP, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard University and associate chief of hospital medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, this does not happen enough.

“Most older adults spend the majority of their days in the hospital in bed, even when they are able to walk independently,” she says. “This is a major risk factor for functional decline.”

Ethan Cumbler, MD, FACP, a hospitalist and director of the Acute Care for the Elderly Service of The University of Colorado Hospital in Denver, explains that his institution has addressed this issue using a dedicated order set for geriatric patients admitted anywhere in the hospital. The order set guides clinicians toward encouraging mobility.

“The order set defaults to ambulation three times a day with nursing supervision,” he says. “In fact, it does not include an option for bed rest. Therefore, a physician would have to manually enter a bed rest order, making supervised exercise the path of least resistance.”

3 Follow the Choosing Wisely guidelines set forth by the American Geriatrics Society.

Susan Parks, MD, associate professor and director, division of geriatric medicine and palliative care, Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, Philadelphia, points to the 10 recommendations developed by the American Geriatrics Society for the care of geriatric patients as an excellent reference for hospitalists treating the elderly.

“Taking care when prescribing medications for the elderly, guarding against the dangers of polypharmacy, and avoiding restraints in cases of delirium not only prevent costly overtreatment but can help maintain the patient’s level of function,” Dr. Parks says.

4 An interdisciplinary approach is most effective for geriatric patients.

Dr. Parks also advocates for team-based care, with hospitalists working collaboratively to bring multiple perspectives to treating the patient.

“The team not only works together to develop a treatment plan but leverages their diverse perspectives to align their treatment plan with the patient’s and family’s needs and individual goals for care,” she says. “This becomes increasingly important as geriatric patients approach the end of life.”

5 Guard against delirium.

Delirium is one of the most common occurrences among geriatric patients.

“While more and more frontline providers are familiar with delirium, most hospital units and the systems of care delivery are not designed to prevent delirium or treat it once it has developed,” Dr. Mattison says. “For instance, while we know the importance of proper sleep and ensuring patients are allowed uninterrupted sleep at night, we still frequently wake patients multiple times per night. Multiple clinical providers have different jobs to do during the night—the aide will wake the patient to check vital signs, the nurse will later wake the patient to dispense a necessary medication, the phlebotomist will wake the patient to draw blood.”

These practices, common in hospitals, are contributing to the prevalence of delirium among geriatric patients.

Dr. Parks warns that dementia patients are at an “especially high risk for delirium and must be observed more closely.

“Because of its transitory nature, delirium is easy for a physician to miss,” she adds. “In fact, another benefit of the team-based approach is that the more physicians [there are] who evaluate a geriatric patient, the greater the chances [are] that delirium will be caught.”

6 Beware the dangers of polypharmacy and medications that pose risks to older adults.

Polypharmacy in the elderly has been associated with significant negative consequences, including increases in healthcare costs, adverse events, and falls, and decreases in nutrition and overall functional status.3

According to Dr. Parks, polypharmacy is a major contributor to delirium; to avoid it, medication lists should be pared down when possible, and the Beers Criteria list should always be consulted when prescribing a new medication. Beyond lists, electronic medical records can provide interventions that can offer embedded medication decision support.

Dr. Mattison says her hospitalist team is fortunate, because the systems Beth Israel Deaconess has in place help improve medication safety for the elderly.

“[We] have a proprietary system that has allowed us to customize alerts and embed decision support,” she explains. “We have selected drug warnings drawn from lists of potentially inappropriate medications for elders [and] embedded decision support screens to guide ordering providers, making it easier to ensure the right drug in the right dose is ordered for the right patient at the right time.”

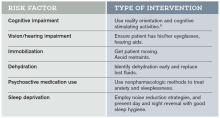

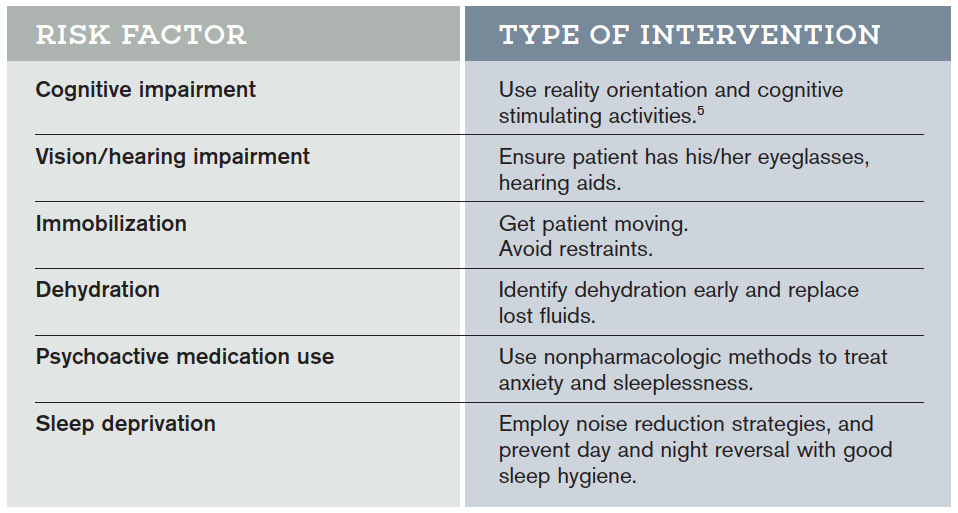

Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP) Interventions

Hospital Elder Life Programs (HELP) are integrated units of care designed to prevent delirium by employing clinically proven interventions in the presence of specific delirium risk factors.5

7 Think in terms of syndromes, rather than independent causes.