User login

Maybelle Cowan-Lincoln began her career in healthcare communications with an internet start-up for which she created and wrote content for www.cysticfibrosis.com. She has worked in pharmaceutical advertising and penned disease treatment guidelines, monographs, and patient educational materials. Maybelle has written for The Hospitalist and other medical and scientific titles since 2011.

10 Things Obstetricians Want Hospitalists to Know

Many hospitalists feel an understandable wave of trepidation when confronted with treating a pregnant woman. They are unfamiliar with the special concerns of pregnancy and unacquainted with how pregnancy can affect preexisting conditions. Historically, most pregnant women have been young and have not yet experienced the typical health challenges that emerge as people age; however, expectant mothers still appear as patients in hospitals.1

With more women putting off pregnancy until their late 30s or early 40s, advances in reproductive medicine that allow pregnancies at more advanced ages, and a rise in obesity and related conditions, more and more pregnant women find themselves in the ED or admitted to the hospital.2

To increase the comfort level of practitioners nationwide, The Hospitalist spoke with several obstetricians (OBs) and hospitalists about what they thought were the most important things you should know when treating a mother-to-be. Here are their answers.

1 Involve an OB in the decision-making process as early as possible.

The most efficient and most comfortable way to proceed is to get input from an OB early in the process of treating a pregnant woman. The specialist can give expert opinions on what tests should be ordered and any special precautions to take to protect the fetus.3 Determining which medications can be prescribed safely is an area of particular discomfort for internal medicine hospitalists.

Edward Ma, MD, a hospitalist at the Coatesville VA Medical Center in Coatesville, Pa., explains the dilemma: “I am comfortable using Category A drugs and usually Category B medications, but because I do not [treat pregnant women] very often, I feel very uncomfortable giving a Category C medication unless I’ve spoken with an OB. This is where I really want guidance.”

In cases where the usual medication for a condition may not be indicated for pregnancy, an OB can help you balance the interests of the mother and child. Making these decisions is made much more comfortable when a physician who treats pregnancy on a daily basis can help.

2 Perform the tests you would perform if the patient were not pregnant.

An important axiom to remember when assessing a pregnant woman is that unless the mother is healthy, the baby cannot be healthy. Therefore, you must do what needs to be done to properly diagnose and treat the mother, and this includes the studies that would be performed if she were not pregnant.

Robert Olson, MD, an OB/GYN hospitalist at PeaceHealth St. Joseph Medical Center in Bellingham, Wash., and founding president of the Society of OB/GYN Hospitalists, cautions hospitalists to proceed as normal with testing. “Whether she’s pregnant or not,” he says, “she needs all the studies a nonpregnant woman would get. If an asthma patient needs a chest X-ray to rule out pneumonia, then do it, because if the mother is not getting enough oxygen, the baby is not getting enough oxygen.”

The tests should be performed as responsibly as possible, Dr. Olson adds. During that chest X-ray, for example, shield the abdomen with a lead apron.4

3 When analyzing test results, make sure you are familiar with what is “normal” for a pregnant woman.

The physiological changes in the body during pregnancy can be extreme, and as a result, the parameters of what is considered acceptable in test results may be dramatically different from those seen in nonpregnant patients. For example, early in pregnancy, progesterone causes respiratory alkalosis, so maternal carbon dioxide parameters that range between 28 and 30 are much lower than the nonpregnant normal of 40. A result of 40 from a blood gases test in pregnancy indicates that the woman is on the verge of respiratory failure.

A hospitalist unfamiliar with the correct parameters in pregnancy could make a significant and life-threatening misjudgment.5

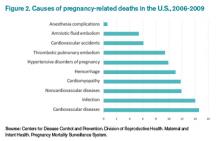

4 Thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism are some of the most common causes of maternal death.6

According to Carolyn M. Zelop, MD, board certified maternal-fetal medicine specialist and director of perinatal ultrasound and research at Valley Hospital in Ridgewood, N.J., “Thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism should always remain part of your differential, even if they are not at the top of the list of possible diagnoses.

“Tests required to exclude these diagnoses, even though they involve very small amounts of radiation, are important to perform,” says Dr. Zelop, a clinical professor at NYU School of Medicine in New York City.

Approaching these diagnostic tests with caution is justified, but it is trumped by the necessity of excluding a life-threatening condition.

5 Prior to 20 weeks, admit the patient to the physician treating her chief complaint.

“Whatever medical condition brings a patient to the hospital prior to 20 weeks, that is the physician that should do the admission,” Dr. Olson says. “If she is suffering from asthma, the internal medicine hospitalist or pulmonologist should admit. If it is appendicitis, the surgeon should do the admission.

“We need to take care of pregnant patients just as well as if they weren’t pregnant.”

During the first half of the pregnancy, care should be directed to the mother. Up until 20 weeks, what is best for the mother is what is best for the baby because the fetus is not viable. It cannot survive outside the mother, so the mother must be saved in order to save the fetus. That means you must give the mother all necessary care to return her to health.

6 After 20 weeks, make sure a pregnant woman is always tilted toward her left side—never supine.

Once an expectant mother reaches 20 weeks, the weight of her expanding uterus can compress the aorta and inferior vena cava, resulting in inadequate blood flow to the baby and to the mother’s brain. A supine position is detrimental not only because it can cause a pregnant woman to feel faint, but also because the interruption in normal blood flow can throw off test results during assessment. Shifting a woman to her left, even with a small tilt from an IV bag under her right hip, can return hemodynamics to homeostasis.

“Left lateral uterine displacement is particularly critical during surgery and while trying to resuscitate a pregnant woman who has coded,” Dr. Zelop says. “The supine position dramatically alters cardiac output. It is nearly impossible to revive someone when the blood flow is compromised by the compression of the uterus in the latter half of pregnancy.”

Click here to listen to Dr. Carolyn Zelop discuss cardiovascular emergencies in pregnant patients.

Remember, however, that the 20-week rule applies to single pregnancies—multiples create a heavier uterus earlier in the pregnancy, so base the timing of lateral uterine displacement on size, not gestational age.

7 Almost all medications can be used in pregnancy.

Despite the stated pregnancy category you read on Hippocrates and warnings pharmaceutical companies place on drug labels, almost all medications can be used in an acute crisis, and even in a subacute situation. As with the choice to perform the necessary tests to correctly diagnose a pregnant woman, the correct drugs to treat the mother must be used. Although there are medications to which you would not chronically expose a fetus, in an emergency situation, they may be acceptable.

This is an area where an OB consult can be especially helpful to balance the needs of mother and baby. If a particular drug is not the best choice for a fetus, an OB can help find the next best option. The specialist’s familiarity with the use of medications in pregnancy may also shed light on a drug labeled “unsafe”: it may be problematic only during certain gestational ages or in concert with a particular drug.

“Sometimes right medication use is not obvious,” says Brigid McCue, MD, chief of the department of OB/GYN at Jordan Hospital in Plymouth, Mass. “Most people would not assume a pregnant woman could undergo chemotherapy for breast cancer or leukemia, but there are options out there. Many patients have been treated for cancer during their pregnancy and have perfectly healthy babies.

“It is a challenge, and every decision is weighed carefully. There is usually some consequence to the baby—maybe it is delivered early or is smaller. But it’s so much nicer for the mom to survive her cancer and be there for the baby.”

8 You can determine gestational age by the position of the uterus relative to the umbilicus.

To make a correct judgment about which medications to use, as well as other treatment decisions, it is vital to ascertain the gestational age of the fetus, but in an acute emergency, there may not be time to do an ultrasound to determine gestational age.

A good way to determine gestational age is to use the umbilicus as a landmark during the physical exam. The rule of thumb is that the uterus touches the umbilicus at 20 weeks and travels one centimeter above it every week thereafter until week 36 or so. As with left lateral uterine displacement after 20 weeks, this rule applies to singleton pregnancies. Multiple fetuses cause a larger uterus earlier in the pregnancy.

9 Do not use lower extremities for vascular access in a pregnant woman.

Dr. Zelop points out that the weight of a pregnant uterus can “significantly compromise intravascular blood flow in the lower extremities.”

“Going below the waist for access can be problematic,” she adds. “Although there may be cases of trauma that make access in the upper limbs difficult or impossible, the lower extremities are not a viable choice.”

Some resuscitation protocols recommend intraosseous access; however, the lower extremities are still not recommended for access in a pregnant woman.

10 The pregnant airway must be treated with respect.

The pregnant airway differs from that of a nonpregnant woman in many important ways, so if intubation becomes necessary, make sure you are familiar with what you are facing. The airway is edematous, which varies the usual landmarks. Increased progesterone causes relaxation of the sphincters between the esophagus and the stomach, and this change predisposes pregnant women to aspiration and loss of consciousness.

In some studies, a failure rate as high as one in 250 is reported. If the patient’s airway needs to be secured, find the most experienced person available to do the intubation. Also, use a smaller tube than would be used for a nonpregnant intubation, usually one size down.

Always ask a woman in labor if she has had any complications during her pregnancy before doing a vaginal exam.

In most cases, deliveries go well for mother and baby; however, certain conditions not immediately apparent upon observation can cause severe problems. For example, a vaginal exam in a pregnant woman with placenta previa can result in a massive hemorrhage.

“In the third trimester, 500 cc of blood per minute flows to the uterus, so a tremendous amount of blood can be lost very quickly,” Dr. Zelop cautions. “Even in cases of women who appear healthy and normal, your radar must be up because an unknown complication can result in major bleeding.”

Maybelle Cowan-Lincoln is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Ma, Edward. Coatesville VA Medical Center, Coatesville, Pa. Telephone interview. October 31, 2013.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, et al. National Vital Statistics Reports: Volume 62, Number 1. June 28, 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr62/nvsr62_01.pdf. Accessed October 6, 2014.

- McCue, Brigid. Chief, department of OB/GYN, Jordan Hospital, Plymouth, Mass. Telephone interview. October 28, 2013.

- Olson, Robert. Founding president, Society of OB/GYN Hospitalists; OB/GYN hospitalist at PeaceHealth St. Joseph Medical Center, Bellingham, Wash. Telephone interview. October 31, 2013.

- Zelop, Carolyn M. Director, perinatal ultrasound and research, Valley Hospital, Ridgewood, N.J. Telephone interview. October 30, 2013.

- Callahan, William. Chief, Maternal and Infant Health Branch, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. E-mail interview. November 12, 2013.

Many hospitalists feel an understandable wave of trepidation when confronted with treating a pregnant woman. They are unfamiliar with the special concerns of pregnancy and unacquainted with how pregnancy can affect preexisting conditions. Historically, most pregnant women have been young and have not yet experienced the typical health challenges that emerge as people age; however, expectant mothers still appear as patients in hospitals.1

With more women putting off pregnancy until their late 30s or early 40s, advances in reproductive medicine that allow pregnancies at more advanced ages, and a rise in obesity and related conditions, more and more pregnant women find themselves in the ED or admitted to the hospital.2

To increase the comfort level of practitioners nationwide, The Hospitalist spoke with several obstetricians (OBs) and hospitalists about what they thought were the most important things you should know when treating a mother-to-be. Here are their answers.

1 Involve an OB in the decision-making process as early as possible.

The most efficient and most comfortable way to proceed is to get input from an OB early in the process of treating a pregnant woman. The specialist can give expert opinions on what tests should be ordered and any special precautions to take to protect the fetus.3 Determining which medications can be prescribed safely is an area of particular discomfort for internal medicine hospitalists.

Edward Ma, MD, a hospitalist at the Coatesville VA Medical Center in Coatesville, Pa., explains the dilemma: “I am comfortable using Category A drugs and usually Category B medications, but because I do not [treat pregnant women] very often, I feel very uncomfortable giving a Category C medication unless I’ve spoken with an OB. This is where I really want guidance.”

In cases where the usual medication for a condition may not be indicated for pregnancy, an OB can help you balance the interests of the mother and child. Making these decisions is made much more comfortable when a physician who treats pregnancy on a daily basis can help.

2 Perform the tests you would perform if the patient were not pregnant.

An important axiom to remember when assessing a pregnant woman is that unless the mother is healthy, the baby cannot be healthy. Therefore, you must do what needs to be done to properly diagnose and treat the mother, and this includes the studies that would be performed if she were not pregnant.

Robert Olson, MD, an OB/GYN hospitalist at PeaceHealth St. Joseph Medical Center in Bellingham, Wash., and founding president of the Society of OB/GYN Hospitalists, cautions hospitalists to proceed as normal with testing. “Whether she’s pregnant or not,” he says, “she needs all the studies a nonpregnant woman would get. If an asthma patient needs a chest X-ray to rule out pneumonia, then do it, because if the mother is not getting enough oxygen, the baby is not getting enough oxygen.”

The tests should be performed as responsibly as possible, Dr. Olson adds. During that chest X-ray, for example, shield the abdomen with a lead apron.4

3 When analyzing test results, make sure you are familiar with what is “normal” for a pregnant woman.

The physiological changes in the body during pregnancy can be extreme, and as a result, the parameters of what is considered acceptable in test results may be dramatically different from those seen in nonpregnant patients. For example, early in pregnancy, progesterone causes respiratory alkalosis, so maternal carbon dioxide parameters that range between 28 and 30 are much lower than the nonpregnant normal of 40. A result of 40 from a blood gases test in pregnancy indicates that the woman is on the verge of respiratory failure.

A hospitalist unfamiliar with the correct parameters in pregnancy could make a significant and life-threatening misjudgment.5

4 Thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism are some of the most common causes of maternal death.6

According to Carolyn M. Zelop, MD, board certified maternal-fetal medicine specialist and director of perinatal ultrasound and research at Valley Hospital in Ridgewood, N.J., “Thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism should always remain part of your differential, even if they are not at the top of the list of possible diagnoses.

“Tests required to exclude these diagnoses, even though they involve very small amounts of radiation, are important to perform,” says Dr. Zelop, a clinical professor at NYU School of Medicine in New York City.

Approaching these diagnostic tests with caution is justified, but it is trumped by the necessity of excluding a life-threatening condition.

5 Prior to 20 weeks, admit the patient to the physician treating her chief complaint.

“Whatever medical condition brings a patient to the hospital prior to 20 weeks, that is the physician that should do the admission,” Dr. Olson says. “If she is suffering from asthma, the internal medicine hospitalist or pulmonologist should admit. If it is appendicitis, the surgeon should do the admission.

“We need to take care of pregnant patients just as well as if they weren’t pregnant.”

During the first half of the pregnancy, care should be directed to the mother. Up until 20 weeks, what is best for the mother is what is best for the baby because the fetus is not viable. It cannot survive outside the mother, so the mother must be saved in order to save the fetus. That means you must give the mother all necessary care to return her to health.

6 After 20 weeks, make sure a pregnant woman is always tilted toward her left side—never supine.

Once an expectant mother reaches 20 weeks, the weight of her expanding uterus can compress the aorta and inferior vena cava, resulting in inadequate blood flow to the baby and to the mother’s brain. A supine position is detrimental not only because it can cause a pregnant woman to feel faint, but also because the interruption in normal blood flow can throw off test results during assessment. Shifting a woman to her left, even with a small tilt from an IV bag under her right hip, can return hemodynamics to homeostasis.

“Left lateral uterine displacement is particularly critical during surgery and while trying to resuscitate a pregnant woman who has coded,” Dr. Zelop says. “The supine position dramatically alters cardiac output. It is nearly impossible to revive someone when the blood flow is compromised by the compression of the uterus in the latter half of pregnancy.”

Click here to listen to Dr. Carolyn Zelop discuss cardiovascular emergencies in pregnant patients.

Remember, however, that the 20-week rule applies to single pregnancies—multiples create a heavier uterus earlier in the pregnancy, so base the timing of lateral uterine displacement on size, not gestational age.

7 Almost all medications can be used in pregnancy.

Despite the stated pregnancy category you read on Hippocrates and warnings pharmaceutical companies place on drug labels, almost all medications can be used in an acute crisis, and even in a subacute situation. As with the choice to perform the necessary tests to correctly diagnose a pregnant woman, the correct drugs to treat the mother must be used. Although there are medications to which you would not chronically expose a fetus, in an emergency situation, they may be acceptable.

This is an area where an OB consult can be especially helpful to balance the needs of mother and baby. If a particular drug is not the best choice for a fetus, an OB can help find the next best option. The specialist’s familiarity with the use of medications in pregnancy may also shed light on a drug labeled “unsafe”: it may be problematic only during certain gestational ages or in concert with a particular drug.

“Sometimes right medication use is not obvious,” says Brigid McCue, MD, chief of the department of OB/GYN at Jordan Hospital in Plymouth, Mass. “Most people would not assume a pregnant woman could undergo chemotherapy for breast cancer or leukemia, but there are options out there. Many patients have been treated for cancer during their pregnancy and have perfectly healthy babies.

“It is a challenge, and every decision is weighed carefully. There is usually some consequence to the baby—maybe it is delivered early or is smaller. But it’s so much nicer for the mom to survive her cancer and be there for the baby.”

8 You can determine gestational age by the position of the uterus relative to the umbilicus.

To make a correct judgment about which medications to use, as well as other treatment decisions, it is vital to ascertain the gestational age of the fetus, but in an acute emergency, there may not be time to do an ultrasound to determine gestational age.

A good way to determine gestational age is to use the umbilicus as a landmark during the physical exam. The rule of thumb is that the uterus touches the umbilicus at 20 weeks and travels one centimeter above it every week thereafter until week 36 or so. As with left lateral uterine displacement after 20 weeks, this rule applies to singleton pregnancies. Multiple fetuses cause a larger uterus earlier in the pregnancy.

9 Do not use lower extremities for vascular access in a pregnant woman.

Dr. Zelop points out that the weight of a pregnant uterus can “significantly compromise intravascular blood flow in the lower extremities.”

“Going below the waist for access can be problematic,” she adds. “Although there may be cases of trauma that make access in the upper limbs difficult or impossible, the lower extremities are not a viable choice.”

Some resuscitation protocols recommend intraosseous access; however, the lower extremities are still not recommended for access in a pregnant woman.

10 The pregnant airway must be treated with respect.

The pregnant airway differs from that of a nonpregnant woman in many important ways, so if intubation becomes necessary, make sure you are familiar with what you are facing. The airway is edematous, which varies the usual landmarks. Increased progesterone causes relaxation of the sphincters between the esophagus and the stomach, and this change predisposes pregnant women to aspiration and loss of consciousness.

In some studies, a failure rate as high as one in 250 is reported. If the patient’s airway needs to be secured, find the most experienced person available to do the intubation. Also, use a smaller tube than would be used for a nonpregnant intubation, usually one size down.

Always ask a woman in labor if she has had any complications during her pregnancy before doing a vaginal exam.

In most cases, deliveries go well for mother and baby; however, certain conditions not immediately apparent upon observation can cause severe problems. For example, a vaginal exam in a pregnant woman with placenta previa can result in a massive hemorrhage.

“In the third trimester, 500 cc of blood per minute flows to the uterus, so a tremendous amount of blood can be lost very quickly,” Dr. Zelop cautions. “Even in cases of women who appear healthy and normal, your radar must be up because an unknown complication can result in major bleeding.”

Maybelle Cowan-Lincoln is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Ma, Edward. Coatesville VA Medical Center, Coatesville, Pa. Telephone interview. October 31, 2013.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, et al. National Vital Statistics Reports: Volume 62, Number 1. June 28, 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr62/nvsr62_01.pdf. Accessed October 6, 2014.

- McCue, Brigid. Chief, department of OB/GYN, Jordan Hospital, Plymouth, Mass. Telephone interview. October 28, 2013.

- Olson, Robert. Founding president, Society of OB/GYN Hospitalists; OB/GYN hospitalist at PeaceHealth St. Joseph Medical Center, Bellingham, Wash. Telephone interview. October 31, 2013.

- Zelop, Carolyn M. Director, perinatal ultrasound and research, Valley Hospital, Ridgewood, N.J. Telephone interview. October 30, 2013.

- Callahan, William. Chief, Maternal and Infant Health Branch, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. E-mail interview. November 12, 2013.

Many hospitalists feel an understandable wave of trepidation when confronted with treating a pregnant woman. They are unfamiliar with the special concerns of pregnancy and unacquainted with how pregnancy can affect preexisting conditions. Historically, most pregnant women have been young and have not yet experienced the typical health challenges that emerge as people age; however, expectant mothers still appear as patients in hospitals.1

With more women putting off pregnancy until their late 30s or early 40s, advances in reproductive medicine that allow pregnancies at more advanced ages, and a rise in obesity and related conditions, more and more pregnant women find themselves in the ED or admitted to the hospital.2

To increase the comfort level of practitioners nationwide, The Hospitalist spoke with several obstetricians (OBs) and hospitalists about what they thought were the most important things you should know when treating a mother-to-be. Here are their answers.

1 Involve an OB in the decision-making process as early as possible.

The most efficient and most comfortable way to proceed is to get input from an OB early in the process of treating a pregnant woman. The specialist can give expert opinions on what tests should be ordered and any special precautions to take to protect the fetus.3 Determining which medications can be prescribed safely is an area of particular discomfort for internal medicine hospitalists.

Edward Ma, MD, a hospitalist at the Coatesville VA Medical Center in Coatesville, Pa., explains the dilemma: “I am comfortable using Category A drugs and usually Category B medications, but because I do not [treat pregnant women] very often, I feel very uncomfortable giving a Category C medication unless I’ve spoken with an OB. This is where I really want guidance.”

In cases where the usual medication for a condition may not be indicated for pregnancy, an OB can help you balance the interests of the mother and child. Making these decisions is made much more comfortable when a physician who treats pregnancy on a daily basis can help.

2 Perform the tests you would perform if the patient were not pregnant.

An important axiom to remember when assessing a pregnant woman is that unless the mother is healthy, the baby cannot be healthy. Therefore, you must do what needs to be done to properly diagnose and treat the mother, and this includes the studies that would be performed if she were not pregnant.

Robert Olson, MD, an OB/GYN hospitalist at PeaceHealth St. Joseph Medical Center in Bellingham, Wash., and founding president of the Society of OB/GYN Hospitalists, cautions hospitalists to proceed as normal with testing. “Whether she’s pregnant or not,” he says, “she needs all the studies a nonpregnant woman would get. If an asthma patient needs a chest X-ray to rule out pneumonia, then do it, because if the mother is not getting enough oxygen, the baby is not getting enough oxygen.”

The tests should be performed as responsibly as possible, Dr. Olson adds. During that chest X-ray, for example, shield the abdomen with a lead apron.4

3 When analyzing test results, make sure you are familiar with what is “normal” for a pregnant woman.

The physiological changes in the body during pregnancy can be extreme, and as a result, the parameters of what is considered acceptable in test results may be dramatically different from those seen in nonpregnant patients. For example, early in pregnancy, progesterone causes respiratory alkalosis, so maternal carbon dioxide parameters that range between 28 and 30 are much lower than the nonpregnant normal of 40. A result of 40 from a blood gases test in pregnancy indicates that the woman is on the verge of respiratory failure.

A hospitalist unfamiliar with the correct parameters in pregnancy could make a significant and life-threatening misjudgment.5

4 Thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism are some of the most common causes of maternal death.6

According to Carolyn M. Zelop, MD, board certified maternal-fetal medicine specialist and director of perinatal ultrasound and research at Valley Hospital in Ridgewood, N.J., “Thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism should always remain part of your differential, even if they are not at the top of the list of possible diagnoses.

“Tests required to exclude these diagnoses, even though they involve very small amounts of radiation, are important to perform,” says Dr. Zelop, a clinical professor at NYU School of Medicine in New York City.

Approaching these diagnostic tests with caution is justified, but it is trumped by the necessity of excluding a life-threatening condition.

5 Prior to 20 weeks, admit the patient to the physician treating her chief complaint.

“Whatever medical condition brings a patient to the hospital prior to 20 weeks, that is the physician that should do the admission,” Dr. Olson says. “If she is suffering from asthma, the internal medicine hospitalist or pulmonologist should admit. If it is appendicitis, the surgeon should do the admission.

“We need to take care of pregnant patients just as well as if they weren’t pregnant.”

During the first half of the pregnancy, care should be directed to the mother. Up until 20 weeks, what is best for the mother is what is best for the baby because the fetus is not viable. It cannot survive outside the mother, so the mother must be saved in order to save the fetus. That means you must give the mother all necessary care to return her to health.

6 After 20 weeks, make sure a pregnant woman is always tilted toward her left side—never supine.

Once an expectant mother reaches 20 weeks, the weight of her expanding uterus can compress the aorta and inferior vena cava, resulting in inadequate blood flow to the baby and to the mother’s brain. A supine position is detrimental not only because it can cause a pregnant woman to feel faint, but also because the interruption in normal blood flow can throw off test results during assessment. Shifting a woman to her left, even with a small tilt from an IV bag under her right hip, can return hemodynamics to homeostasis.

“Left lateral uterine displacement is particularly critical during surgery and while trying to resuscitate a pregnant woman who has coded,” Dr. Zelop says. “The supine position dramatically alters cardiac output. It is nearly impossible to revive someone when the blood flow is compromised by the compression of the uterus in the latter half of pregnancy.”

Click here to listen to Dr. Carolyn Zelop discuss cardiovascular emergencies in pregnant patients.

Remember, however, that the 20-week rule applies to single pregnancies—multiples create a heavier uterus earlier in the pregnancy, so base the timing of lateral uterine displacement on size, not gestational age.

7 Almost all medications can be used in pregnancy.

Despite the stated pregnancy category you read on Hippocrates and warnings pharmaceutical companies place on drug labels, almost all medications can be used in an acute crisis, and even in a subacute situation. As with the choice to perform the necessary tests to correctly diagnose a pregnant woman, the correct drugs to treat the mother must be used. Although there are medications to which you would not chronically expose a fetus, in an emergency situation, they may be acceptable.

This is an area where an OB consult can be especially helpful to balance the needs of mother and baby. If a particular drug is not the best choice for a fetus, an OB can help find the next best option. The specialist’s familiarity with the use of medications in pregnancy may also shed light on a drug labeled “unsafe”: it may be problematic only during certain gestational ages or in concert with a particular drug.

“Sometimes right medication use is not obvious,” says Brigid McCue, MD, chief of the department of OB/GYN at Jordan Hospital in Plymouth, Mass. “Most people would not assume a pregnant woman could undergo chemotherapy for breast cancer or leukemia, but there are options out there. Many patients have been treated for cancer during their pregnancy and have perfectly healthy babies.

“It is a challenge, and every decision is weighed carefully. There is usually some consequence to the baby—maybe it is delivered early or is smaller. But it’s so much nicer for the mom to survive her cancer and be there for the baby.”

8 You can determine gestational age by the position of the uterus relative to the umbilicus.

To make a correct judgment about which medications to use, as well as other treatment decisions, it is vital to ascertain the gestational age of the fetus, but in an acute emergency, there may not be time to do an ultrasound to determine gestational age.

A good way to determine gestational age is to use the umbilicus as a landmark during the physical exam. The rule of thumb is that the uterus touches the umbilicus at 20 weeks and travels one centimeter above it every week thereafter until week 36 or so. As with left lateral uterine displacement after 20 weeks, this rule applies to singleton pregnancies. Multiple fetuses cause a larger uterus earlier in the pregnancy.

9 Do not use lower extremities for vascular access in a pregnant woman.

Dr. Zelop points out that the weight of a pregnant uterus can “significantly compromise intravascular blood flow in the lower extremities.”

“Going below the waist for access can be problematic,” she adds. “Although there may be cases of trauma that make access in the upper limbs difficult or impossible, the lower extremities are not a viable choice.”

Some resuscitation protocols recommend intraosseous access; however, the lower extremities are still not recommended for access in a pregnant woman.

10 The pregnant airway must be treated with respect.

The pregnant airway differs from that of a nonpregnant woman in many important ways, so if intubation becomes necessary, make sure you are familiar with what you are facing. The airway is edematous, which varies the usual landmarks. Increased progesterone causes relaxation of the sphincters between the esophagus and the stomach, and this change predisposes pregnant women to aspiration and loss of consciousness.

In some studies, a failure rate as high as one in 250 is reported. If the patient’s airway needs to be secured, find the most experienced person available to do the intubation. Also, use a smaller tube than would be used for a nonpregnant intubation, usually one size down.

Always ask a woman in labor if she has had any complications during her pregnancy before doing a vaginal exam.

In most cases, deliveries go well for mother and baby; however, certain conditions not immediately apparent upon observation can cause severe problems. For example, a vaginal exam in a pregnant woman with placenta previa can result in a massive hemorrhage.

“In the third trimester, 500 cc of blood per minute flows to the uterus, so a tremendous amount of blood can be lost very quickly,” Dr. Zelop cautions. “Even in cases of women who appear healthy and normal, your radar must be up because an unknown complication can result in major bleeding.”

Maybelle Cowan-Lincoln is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Ma, Edward. Coatesville VA Medical Center, Coatesville, Pa. Telephone interview. October 31, 2013.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, et al. National Vital Statistics Reports: Volume 62, Number 1. June 28, 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr62/nvsr62_01.pdf. Accessed October 6, 2014.

- McCue, Brigid. Chief, department of OB/GYN, Jordan Hospital, Plymouth, Mass. Telephone interview. October 28, 2013.

- Olson, Robert. Founding president, Society of OB/GYN Hospitalists; OB/GYN hospitalist at PeaceHealth St. Joseph Medical Center, Bellingham, Wash. Telephone interview. October 31, 2013.

- Zelop, Carolyn M. Director, perinatal ultrasound and research, Valley Hospital, Ridgewood, N.J. Telephone interview. October 30, 2013.

- Callahan, William. Chief, Maternal and Infant Health Branch, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. E-mail interview. November 12, 2013.

Hospitalist Outlines Importance of Nutrition in Patient Care

Click here to listen to excerpts of Dr. Parkhurst's interview with The Hospitalist

Click here to listen to excerpts of Dr. Parkhurst's interview with The Hospitalist

Click here to listen to excerpts of Dr. Parkhurst's interview with The Hospitalist

Nutritional Intervention Can Improve Hospital Patients' Outcome, Reduce Costs

Health-care reform is on everyone’s mind these days, and SHM, along with numerous other groups, believes some reform goals can be achieved through the stomach.

Data show an effective program of nutritional intervention during a patient’s hospital stay can go a long way toward improving patient outcomes and reducing costs.1 Hospitalists, however, often have little formal nutrition training. A multidisciplinary approach to patient nutrition that brings together multiple stakeholders—hospitalists, nurses, and dietitians—might effectively address this need with a team tactic, according to Melissa Parkhurst, MD, medical director of the hospital medicine section at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City.1

Between 20% and 50% of inpatients suffer from malnutrition.2 Many patients, especially the elderly, are malnourished on admission. Many more become malnourished within a few days of their hospital stay due to NPO orders and the effects of disease on metabolism.2 Malnutrition has been associated with worsened discharge status, longer length of stay, higher costs, and greater mortality, as well as increased risk of:2

- Nosocomial infections;

- Falls;

- Pressure ulcers; and

- 30-day readmissions.

To address malnutrition prevalence and its detrimental effects, SHM and the Academy of Medical-Surgical Nurses (AMSN), the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND), the American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN), and Abbott Nutrition have formed the Alliance for Patient Nutrition. Kelly Tappenden, MD, PhD, professor of food science and human nutrition at the University of Illinois at Urbana, says the alliance aims to raise awareness of the impact nutrition can have on patient outcomes (see “Three Steps to Better Nutrition,” below).

The campaign is being initiated with the publication of a consensus paper in several peer-reviewed journals. A baseline survey will be conducted among professionals represented in the alliance to assess their familiarity with the prevalence of malnutrition in a hospital setting. The next step is to foster this change in patient care by providing resources on the alliance’s website (www.malnutrition.com), including malnutrition screening tools, a toolkit to facilitate multidisciplinary collaboration, and continuing medical education (CME) information.

As a founding member of the alliance, SHM is communicating this message to its members, encouraging hospitalists to lead the way in transforming hospital culture to recognize the critical role nutrition plays in patient care.

“Nutrition matters,” Dr. Parkhurst says. “You can be winning the battle and losing the war if you are not paying attention to patient nutrition.”

Team Approach

Beth Quatrara, DNP, RN, director of the nursing research program at the University of Virginia Health System in Charlottesville and nursing spokesperson for the alliance, says several shortcomings can be identified in the nutritional care U.S. hospitals provide from admission through discharge and beyond. For example, the Joint Commission requires that all patients be screened for malnutrition risk within 48 hours of admission. But screening is often as cursory as looking at the patient and deciding that he or she “looks fine.” Diets often are set for patients with no thought to taste, texture, or cultural preferences, or even to such practical matters as ascertaining whether the patient has dentures, Quatrara says. Meal trays are left when patients are out of their rooms for procedures and retrieved by dietary staff before patients return. And except for calorie count orders, accurate records often are not kept of actual food consumption.

The alliance, which is made possible with support from Abbott's nutrition business, recommends that physicians implement a three-step plan to improve patient outcomes. The approach begins with an evaluation of a patient’s nutritional status on admission using a simple, validated screening tool, such as the Malnutrition Screening Tool. When an at-risk status is determined, a more in-depth screening is performed. “When patients at risk for malnutrition can be identified faster, appropriate interventions can be put into place sooner,” Quatrara says.

The second step is nutrition intervention with a personalized nutritional care plan that takes into account the individual’s health conditions, caloric needs, physical limitations, tastes, and preferences. An interdisciplinary team approach can transform hospital nutrition, bringing together hospitalists, nurses, nursing assistants, registered dietitians, and the dietary staff to collaboratively develop a nutrition care plan that will be central to patient’s overall treatment, Dr. Tappenden says.

“There is a science behind nutrition and metabolic care,” Dr. Tappenden says. “Just like any other aspect of patient care, we can’t just throw out a blanket solution.”

But nutritional care cannot stop with developing this plan at the outset. Patients must be rescreened throughout their time at the hospital to measure any changes in nutritional status due to disease progression or treatment success.

For optimal impact, all members of the nutritional care team—nurses, nursing assistants, dietary support staff, and family members—should take responsibility for an essential component of the patient’s care: tracking and reporting consumption to the physician to open a dialogue about balancing an individual’s needs with tastes and preferences.

The hospitalist’s final step is developing a discharge plan that includes nutrition care and education so that patients, families, and caregivers can implement better nutrition at home.

“Nutrition makes sense,” Dr. Tappenden says. “Everything we are working toward in healthcare reform can be achieved by taking more care to make nutrition part of the solution.”

Maybelle Cowan-Lincoln is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Kirkland LL, Kashiwagi DT, Brantley S, Scheurer D, Varkey P. Nutrition in the hospitalized patient. J Hosp Med. 2013;8:52-58.

- Alliance for Patient Nutrition. Malnutrition Backgrounder.

- Banks M, Bauer J, Graves N, Ash S. Malnutrition and pressure ulcer risk in adults in Australian health care facilities. Clin Nutr. 2010;26:896-901.

- Fry DE, Pine M, Jones BL, Meimban RJ. Patient characteristics and the occurrence of never events. Arch Surg. 2010;145:148-151.

- Gariballa S, Forster S, Walters S, Powers H. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of nutritional supplementation during acute illness. Am J Med. 2006;119:693-699.

- Neelemaat F, Lips P, Bosmans J, Thijs A, Seidell JC, van Bokhorst-de van der Schuerer MA. Short-term oral nutritional intervention with protein and vitamin D decreases falls in malnourished older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:691-699.

- Brugler L, DiPrinzio MJ, Bernstein L. The five-year evolution of a malnutrition treatment program in a community hospital. J Qual Improv. 1999;25:191-206.

- Stratton PJ, et al. Enteral nutritional support in prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2005;4:422-450.

- Lawson RM, Doshi MK, Barton JR, Cobden I. The effect of unselected post-operative nutritional supplementation on nutritional status and clinical outcomes of elderly orthopaedic patients. Clin Nutr. 2003;22:39-46.

Health-care reform is on everyone’s mind these days, and SHM, along with numerous other groups, believes some reform goals can be achieved through the stomach.

Data show an effective program of nutritional intervention during a patient’s hospital stay can go a long way toward improving patient outcomes and reducing costs.1 Hospitalists, however, often have little formal nutrition training. A multidisciplinary approach to patient nutrition that brings together multiple stakeholders—hospitalists, nurses, and dietitians—might effectively address this need with a team tactic, according to Melissa Parkhurst, MD, medical director of the hospital medicine section at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City.1

Between 20% and 50% of inpatients suffer from malnutrition.2 Many patients, especially the elderly, are malnourished on admission. Many more become malnourished within a few days of their hospital stay due to NPO orders and the effects of disease on metabolism.2 Malnutrition has been associated with worsened discharge status, longer length of stay, higher costs, and greater mortality, as well as increased risk of:2

- Nosocomial infections;

- Falls;

- Pressure ulcers; and

- 30-day readmissions.

To address malnutrition prevalence and its detrimental effects, SHM and the Academy of Medical-Surgical Nurses (AMSN), the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND), the American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN), and Abbott Nutrition have formed the Alliance for Patient Nutrition. Kelly Tappenden, MD, PhD, professor of food science and human nutrition at the University of Illinois at Urbana, says the alliance aims to raise awareness of the impact nutrition can have on patient outcomes (see “Three Steps to Better Nutrition,” below).

The campaign is being initiated with the publication of a consensus paper in several peer-reviewed journals. A baseline survey will be conducted among professionals represented in the alliance to assess their familiarity with the prevalence of malnutrition in a hospital setting. The next step is to foster this change in patient care by providing resources on the alliance’s website (www.malnutrition.com), including malnutrition screening tools, a toolkit to facilitate multidisciplinary collaboration, and continuing medical education (CME) information.

As a founding member of the alliance, SHM is communicating this message to its members, encouraging hospitalists to lead the way in transforming hospital culture to recognize the critical role nutrition plays in patient care.

“Nutrition matters,” Dr. Parkhurst says. “You can be winning the battle and losing the war if you are not paying attention to patient nutrition.”

Team Approach

Beth Quatrara, DNP, RN, director of the nursing research program at the University of Virginia Health System in Charlottesville and nursing spokesperson for the alliance, says several shortcomings can be identified in the nutritional care U.S. hospitals provide from admission through discharge and beyond. For example, the Joint Commission requires that all patients be screened for malnutrition risk within 48 hours of admission. But screening is often as cursory as looking at the patient and deciding that he or she “looks fine.” Diets often are set for patients with no thought to taste, texture, or cultural preferences, or even to such practical matters as ascertaining whether the patient has dentures, Quatrara says. Meal trays are left when patients are out of their rooms for procedures and retrieved by dietary staff before patients return. And except for calorie count orders, accurate records often are not kept of actual food consumption.

The alliance, which is made possible with support from Abbott's nutrition business, recommends that physicians implement a three-step plan to improve patient outcomes. The approach begins with an evaluation of a patient’s nutritional status on admission using a simple, validated screening tool, such as the Malnutrition Screening Tool. When an at-risk status is determined, a more in-depth screening is performed. “When patients at risk for malnutrition can be identified faster, appropriate interventions can be put into place sooner,” Quatrara says.

The second step is nutrition intervention with a personalized nutritional care plan that takes into account the individual’s health conditions, caloric needs, physical limitations, tastes, and preferences. An interdisciplinary team approach can transform hospital nutrition, bringing together hospitalists, nurses, nursing assistants, registered dietitians, and the dietary staff to collaboratively develop a nutrition care plan that will be central to patient’s overall treatment, Dr. Tappenden says.

“There is a science behind nutrition and metabolic care,” Dr. Tappenden says. “Just like any other aspect of patient care, we can’t just throw out a blanket solution.”

But nutritional care cannot stop with developing this plan at the outset. Patients must be rescreened throughout their time at the hospital to measure any changes in nutritional status due to disease progression or treatment success.

For optimal impact, all members of the nutritional care team—nurses, nursing assistants, dietary support staff, and family members—should take responsibility for an essential component of the patient’s care: tracking and reporting consumption to the physician to open a dialogue about balancing an individual’s needs with tastes and preferences.

The hospitalist’s final step is developing a discharge plan that includes nutrition care and education so that patients, families, and caregivers can implement better nutrition at home.

“Nutrition makes sense,” Dr. Tappenden says. “Everything we are working toward in healthcare reform can be achieved by taking more care to make nutrition part of the solution.”

Maybelle Cowan-Lincoln is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Kirkland LL, Kashiwagi DT, Brantley S, Scheurer D, Varkey P. Nutrition in the hospitalized patient. J Hosp Med. 2013;8:52-58.

- Alliance for Patient Nutrition. Malnutrition Backgrounder.

- Banks M, Bauer J, Graves N, Ash S. Malnutrition and pressure ulcer risk in adults in Australian health care facilities. Clin Nutr. 2010;26:896-901.

- Fry DE, Pine M, Jones BL, Meimban RJ. Patient characteristics and the occurrence of never events. Arch Surg. 2010;145:148-151.

- Gariballa S, Forster S, Walters S, Powers H. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of nutritional supplementation during acute illness. Am J Med. 2006;119:693-699.

- Neelemaat F, Lips P, Bosmans J, Thijs A, Seidell JC, van Bokhorst-de van der Schuerer MA. Short-term oral nutritional intervention with protein and vitamin D decreases falls in malnourished older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:691-699.

- Brugler L, DiPrinzio MJ, Bernstein L. The five-year evolution of a malnutrition treatment program in a community hospital. J Qual Improv. 1999;25:191-206.

- Stratton PJ, et al. Enteral nutritional support in prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2005;4:422-450.

- Lawson RM, Doshi MK, Barton JR, Cobden I. The effect of unselected post-operative nutritional supplementation on nutritional status and clinical outcomes of elderly orthopaedic patients. Clin Nutr. 2003;22:39-46.

Health-care reform is on everyone’s mind these days, and SHM, along with numerous other groups, believes some reform goals can be achieved through the stomach.

Data show an effective program of nutritional intervention during a patient’s hospital stay can go a long way toward improving patient outcomes and reducing costs.1 Hospitalists, however, often have little formal nutrition training. A multidisciplinary approach to patient nutrition that brings together multiple stakeholders—hospitalists, nurses, and dietitians—might effectively address this need with a team tactic, according to Melissa Parkhurst, MD, medical director of the hospital medicine section at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City.1

Between 20% and 50% of inpatients suffer from malnutrition.2 Many patients, especially the elderly, are malnourished on admission. Many more become malnourished within a few days of their hospital stay due to NPO orders and the effects of disease on metabolism.2 Malnutrition has been associated with worsened discharge status, longer length of stay, higher costs, and greater mortality, as well as increased risk of:2

- Nosocomial infections;

- Falls;

- Pressure ulcers; and

- 30-day readmissions.

To address malnutrition prevalence and its detrimental effects, SHM and the Academy of Medical-Surgical Nurses (AMSN), the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND), the American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN), and Abbott Nutrition have formed the Alliance for Patient Nutrition. Kelly Tappenden, MD, PhD, professor of food science and human nutrition at the University of Illinois at Urbana, says the alliance aims to raise awareness of the impact nutrition can have on patient outcomes (see “Three Steps to Better Nutrition,” below).

The campaign is being initiated with the publication of a consensus paper in several peer-reviewed journals. A baseline survey will be conducted among professionals represented in the alliance to assess their familiarity with the prevalence of malnutrition in a hospital setting. The next step is to foster this change in patient care by providing resources on the alliance’s website (www.malnutrition.com), including malnutrition screening tools, a toolkit to facilitate multidisciplinary collaboration, and continuing medical education (CME) information.

As a founding member of the alliance, SHM is communicating this message to its members, encouraging hospitalists to lead the way in transforming hospital culture to recognize the critical role nutrition plays in patient care.

“Nutrition matters,” Dr. Parkhurst says. “You can be winning the battle and losing the war if you are not paying attention to patient nutrition.”

Team Approach

Beth Quatrara, DNP, RN, director of the nursing research program at the University of Virginia Health System in Charlottesville and nursing spokesperson for the alliance, says several shortcomings can be identified in the nutritional care U.S. hospitals provide from admission through discharge and beyond. For example, the Joint Commission requires that all patients be screened for malnutrition risk within 48 hours of admission. But screening is often as cursory as looking at the patient and deciding that he or she “looks fine.” Diets often are set for patients with no thought to taste, texture, or cultural preferences, or even to such practical matters as ascertaining whether the patient has dentures, Quatrara says. Meal trays are left when patients are out of their rooms for procedures and retrieved by dietary staff before patients return. And except for calorie count orders, accurate records often are not kept of actual food consumption.

The alliance, which is made possible with support from Abbott's nutrition business, recommends that physicians implement a three-step plan to improve patient outcomes. The approach begins with an evaluation of a patient’s nutritional status on admission using a simple, validated screening tool, such as the Malnutrition Screening Tool. When an at-risk status is determined, a more in-depth screening is performed. “When patients at risk for malnutrition can be identified faster, appropriate interventions can be put into place sooner,” Quatrara says.

The second step is nutrition intervention with a personalized nutritional care plan that takes into account the individual’s health conditions, caloric needs, physical limitations, tastes, and preferences. An interdisciplinary team approach can transform hospital nutrition, bringing together hospitalists, nurses, nursing assistants, registered dietitians, and the dietary staff to collaboratively develop a nutrition care plan that will be central to patient’s overall treatment, Dr. Tappenden says.

“There is a science behind nutrition and metabolic care,” Dr. Tappenden says. “Just like any other aspect of patient care, we can’t just throw out a blanket solution.”

But nutritional care cannot stop with developing this plan at the outset. Patients must be rescreened throughout their time at the hospital to measure any changes in nutritional status due to disease progression or treatment success.

For optimal impact, all members of the nutritional care team—nurses, nursing assistants, dietary support staff, and family members—should take responsibility for an essential component of the patient’s care: tracking and reporting consumption to the physician to open a dialogue about balancing an individual’s needs with tastes and preferences.

The hospitalist’s final step is developing a discharge plan that includes nutrition care and education so that patients, families, and caregivers can implement better nutrition at home.

“Nutrition makes sense,” Dr. Tappenden says. “Everything we are working toward in healthcare reform can be achieved by taking more care to make nutrition part of the solution.”

Maybelle Cowan-Lincoln is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Kirkland LL, Kashiwagi DT, Brantley S, Scheurer D, Varkey P. Nutrition in the hospitalized patient. J Hosp Med. 2013;8:52-58.

- Alliance for Patient Nutrition. Malnutrition Backgrounder.

- Banks M, Bauer J, Graves N, Ash S. Malnutrition and pressure ulcer risk in adults in Australian health care facilities. Clin Nutr. 2010;26:896-901.

- Fry DE, Pine M, Jones BL, Meimban RJ. Patient characteristics and the occurrence of never events. Arch Surg. 2010;145:148-151.

- Gariballa S, Forster S, Walters S, Powers H. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of nutritional supplementation during acute illness. Am J Med. 2006;119:693-699.

- Neelemaat F, Lips P, Bosmans J, Thijs A, Seidell JC, van Bokhorst-de van der Schuerer MA. Short-term oral nutritional intervention with protein and vitamin D decreases falls in malnourished older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:691-699.

- Brugler L, DiPrinzio MJ, Bernstein L. The five-year evolution of a malnutrition treatment program in a community hospital. J Qual Improv. 1999;25:191-206.

- Stratton PJ, et al. Enteral nutritional support in prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2005;4:422-450.

- Lawson RM, Doshi MK, Barton JR, Cobden I. The effect of unselected post-operative nutritional supplementation on nutritional status and clinical outcomes of elderly orthopaedic patients. Clin Nutr. 2003;22:39-46.

Guidelines Help Hospitalists Manage Acute Coronary Syndrome Patients

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) accounts for more than 1.4 million hospital admissions per year, and as many as 1 in 5 ACS patients die in the first six months after diagnosis, according to the American Academy of Family Physicians. With that in mind, Bruce Darrow, MD, PhD, presented the seminar “Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS): Keys to Treatment and New Advances” for more than 150 hospitalists at the seventh annual Mid-Atlantic Hospital Medicine Symposium in October at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York City.

“ACS patients are being admitted to a hospitalist’s care, although these physicians are not coronary service-line providers,” said Dr. Darrow, Mount Sinai’s director of telemetry services. “Often they work with cardiologists, but there are things hospitalists should be comfortable doing without consulting a specialist.”

Dr. Darrow spent the majority of his presentation reviewing the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association (ACCF/AHA) 2012 update of the 2007 guidelines for managing patients with myocardial infarction (MI).

Three Phases of Treatment

To achieve the comfort level he believes hospitalists require, Dr. Darrow explained three phases of ACS care: initial medical treatment, reperfusion therapy, and transitional management.1,2 Hospitalists who see patients within the first 24 hours of their hospital stay are providing

initial treatment.

Once the physician determines that the patient is experiencing an acute myocardial infarction, treatment should begin with:

- Aspirin;

- Low-molecular-weight heparin (or heparin if the patient will be heading to the cath lab); and

- Antiplatelet agents (clopidogrel or ticagrelor for this “upstream” portion of therapy).

—Bruce Darrow, MD, PhD, director of telemetry services, Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York

Other medications to consider are intravenous IIb/IIIa inhibitors, such as abciximab, that often were used for patients going to the cath lab. Beta-blockers, although no longer required, can be included in the arsenal. Similarly, anti-ischemics may be employed, despite a lack of evidence to support their use (e.g. oxygen can be a good idea, and morphine will certainly benefit someone in pain).

In cases with ST elevation, after initial treatment, the patient is generally sent to reperfusion therapy, unless it is contraindicated. Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is recommended in facilities with a 24/7 cath lab, or in cases for which the patient can be transferred to a hospital with an available cath lab within three hours. Otherwise, thrombolysis is the route to take, and all hospitals should be capable of that procedure, Dr. Darrow said.

After reperfusion or conservative management measures are taken, the patient is transitioned to post-MI care, which includes:

- Aspirin (except where contraindicated);

- Antiplatelet agents (clopidogrel, ticagrelor, and prasugruel, depending on patient risk factors; see Figure 1, right);

- Beta-blockers;

- Statins;

- ACE inhibitors (for patients with systolic dysfunction); and

- Eplerenone/spironolactone (for patients with systolic dysfunction and respiratory conditions).

Core Measures

Dr. Darrow also addressed the ACS Core Measures, performance measurement, and improvement initiatives set by The Joint Commission and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).3

Upon arrival, patients should be given:

- Aspirin (Joint Commission-required; voluntary according to CMS);

- Thrombolyis within 30 minutes (if applicable); and

- Primary PCI within 90 minutes (if applicable).

At discharge, patients should be given:

- Aspirin;

- Beta-blockers (Joint Commission-required; voluntary according to CMS);

- ACE/ARB for systolic heart failure (Joint Commission-required;

- voluntary according to CMS); and

- Statins.

Maybelle Cowan-Lincoln is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Jneid H, Anderson JL, Wright RS, et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA focused update of the guideline for the management of patients with unstable angina/non–ST-elevation myocardial infarction (updating the 2007 guideline and replacing the 2011 focused update). a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(7):645-681.

- Darrow B. Acute coronary syndrome (ACS): Keys to treatment and new advances. Paper presented at the seventh annual Mid-Atlantic Hospital Medicine Symposium; Oct. 19, 2012; New York, NY.

- Joint Commission and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Specifications Manual for National Hospital Inpatient Quality Measures. The Joint Commission website. Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/specifications_manual_for_national_hospital_inpatient_quality_measures.aspx. Accessed Oct. 22, 2012.

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) accounts for more than 1.4 million hospital admissions per year, and as many as 1 in 5 ACS patients die in the first six months after diagnosis, according to the American Academy of Family Physicians. With that in mind, Bruce Darrow, MD, PhD, presented the seminar “Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS): Keys to Treatment and New Advances” for more than 150 hospitalists at the seventh annual Mid-Atlantic Hospital Medicine Symposium in October at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York City.

“ACS patients are being admitted to a hospitalist’s care, although these physicians are not coronary service-line providers,” said Dr. Darrow, Mount Sinai’s director of telemetry services. “Often they work with cardiologists, but there are things hospitalists should be comfortable doing without consulting a specialist.”

Dr. Darrow spent the majority of his presentation reviewing the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association (ACCF/AHA) 2012 update of the 2007 guidelines for managing patients with myocardial infarction (MI).

Three Phases of Treatment

To achieve the comfort level he believes hospitalists require, Dr. Darrow explained three phases of ACS care: initial medical treatment, reperfusion therapy, and transitional management.1,2 Hospitalists who see patients within the first 24 hours of their hospital stay are providing

initial treatment.

Once the physician determines that the patient is experiencing an acute myocardial infarction, treatment should begin with:

- Aspirin;

- Low-molecular-weight heparin (or heparin if the patient will be heading to the cath lab); and

- Antiplatelet agents (clopidogrel or ticagrelor for this “upstream” portion of therapy).

—Bruce Darrow, MD, PhD, director of telemetry services, Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York

Other medications to consider are intravenous IIb/IIIa inhibitors, such as abciximab, that often were used for patients going to the cath lab. Beta-blockers, although no longer required, can be included in the arsenal. Similarly, anti-ischemics may be employed, despite a lack of evidence to support their use (e.g. oxygen can be a good idea, and morphine will certainly benefit someone in pain).

In cases with ST elevation, after initial treatment, the patient is generally sent to reperfusion therapy, unless it is contraindicated. Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is recommended in facilities with a 24/7 cath lab, or in cases for which the patient can be transferred to a hospital with an available cath lab within three hours. Otherwise, thrombolysis is the route to take, and all hospitals should be capable of that procedure, Dr. Darrow said.

After reperfusion or conservative management measures are taken, the patient is transitioned to post-MI care, which includes:

- Aspirin (except where contraindicated);

- Antiplatelet agents (clopidogrel, ticagrelor, and prasugruel, depending on patient risk factors; see Figure 1, right);

- Beta-blockers;

- Statins;

- ACE inhibitors (for patients with systolic dysfunction); and

- Eplerenone/spironolactone (for patients with systolic dysfunction and respiratory conditions).

Core Measures

Dr. Darrow also addressed the ACS Core Measures, performance measurement, and improvement initiatives set by The Joint Commission and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).3

Upon arrival, patients should be given:

- Aspirin (Joint Commission-required; voluntary according to CMS);

- Thrombolyis within 30 minutes (if applicable); and

- Primary PCI within 90 minutes (if applicable).

At discharge, patients should be given:

- Aspirin;

- Beta-blockers (Joint Commission-required; voluntary according to CMS);

- ACE/ARB for systolic heart failure (Joint Commission-required;

- voluntary according to CMS); and

- Statins.

Maybelle Cowan-Lincoln is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Jneid H, Anderson JL, Wright RS, et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA focused update of the guideline for the management of patients with unstable angina/non–ST-elevation myocardial infarction (updating the 2007 guideline and replacing the 2011 focused update). a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(7):645-681.

- Darrow B. Acute coronary syndrome (ACS): Keys to treatment and new advances. Paper presented at the seventh annual Mid-Atlantic Hospital Medicine Symposium; Oct. 19, 2012; New York, NY.

- Joint Commission and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Specifications Manual for National Hospital Inpatient Quality Measures. The Joint Commission website. Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/specifications_manual_for_national_hospital_inpatient_quality_measures.aspx. Accessed Oct. 22, 2012.

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) accounts for more than 1.4 million hospital admissions per year, and as many as 1 in 5 ACS patients die in the first six months after diagnosis, according to the American Academy of Family Physicians. With that in mind, Bruce Darrow, MD, PhD, presented the seminar “Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS): Keys to Treatment and New Advances” for more than 150 hospitalists at the seventh annual Mid-Atlantic Hospital Medicine Symposium in October at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York City.

“ACS patients are being admitted to a hospitalist’s care, although these physicians are not coronary service-line providers,” said Dr. Darrow, Mount Sinai’s director of telemetry services. “Often they work with cardiologists, but there are things hospitalists should be comfortable doing without consulting a specialist.”

Dr. Darrow spent the majority of his presentation reviewing the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association (ACCF/AHA) 2012 update of the 2007 guidelines for managing patients with myocardial infarction (MI).

Three Phases of Treatment

To achieve the comfort level he believes hospitalists require, Dr. Darrow explained three phases of ACS care: initial medical treatment, reperfusion therapy, and transitional management.1,2 Hospitalists who see patients within the first 24 hours of their hospital stay are providing

initial treatment.

Once the physician determines that the patient is experiencing an acute myocardial infarction, treatment should begin with:

- Aspirin;

- Low-molecular-weight heparin (or heparin if the patient will be heading to the cath lab); and

- Antiplatelet agents (clopidogrel or ticagrelor for this “upstream” portion of therapy).

—Bruce Darrow, MD, PhD, director of telemetry services, Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York

Other medications to consider are intravenous IIb/IIIa inhibitors, such as abciximab, that often were used for patients going to the cath lab. Beta-blockers, although no longer required, can be included in the arsenal. Similarly, anti-ischemics may be employed, despite a lack of evidence to support their use (e.g. oxygen can be a good idea, and morphine will certainly benefit someone in pain).

In cases with ST elevation, after initial treatment, the patient is generally sent to reperfusion therapy, unless it is contraindicated. Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is recommended in facilities with a 24/7 cath lab, or in cases for which the patient can be transferred to a hospital with an available cath lab within three hours. Otherwise, thrombolysis is the route to take, and all hospitals should be capable of that procedure, Dr. Darrow said.

After reperfusion or conservative management measures are taken, the patient is transitioned to post-MI care, which includes:

- Aspirin (except where contraindicated);

- Antiplatelet agents (clopidogrel, ticagrelor, and prasugruel, depending on patient risk factors; see Figure 1, right);

- Beta-blockers;

- Statins;

- ACE inhibitors (for patients with systolic dysfunction); and

- Eplerenone/spironolactone (for patients with systolic dysfunction and respiratory conditions).

Core Measures

Dr. Darrow also addressed the ACS Core Measures, performance measurement, and improvement initiatives set by The Joint Commission and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).3

Upon arrival, patients should be given:

- Aspirin (Joint Commission-required; voluntary according to CMS);

- Thrombolyis within 30 minutes (if applicable); and

- Primary PCI within 90 minutes (if applicable).

At discharge, patients should be given:

- Aspirin;

- Beta-blockers (Joint Commission-required; voluntary according to CMS);

- ACE/ARB for systolic heart failure (Joint Commission-required;

- voluntary according to CMS); and

- Statins.

Maybelle Cowan-Lincoln is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Jneid H, Anderson JL, Wright RS, et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA focused update of the guideline for the management of patients with unstable angina/non–ST-elevation myocardial infarction (updating the 2007 guideline and replacing the 2011 focused update). a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(7):645-681.

- Darrow B. Acute coronary syndrome (ACS): Keys to treatment and new advances. Paper presented at the seventh annual Mid-Atlantic Hospital Medicine Symposium; Oct. 19, 2012; New York, NY.

- Joint Commission and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Specifications Manual for National Hospital Inpatient Quality Measures. The Joint Commission website. Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/specifications_manual_for_national_hospital_inpatient_quality_measures.aspx. Accessed Oct. 22, 2012.