User login

Moment vs Movement: Mission-Based Tweeting for Physician Advocacy

“We, the members of the world community of physicians, solemnly commit ourselves to . . . advocate for social, economic, educational and political changes that ameliorate suffering and contribute to human well-being.”

— American Medical Association Oath of Professional Responsibility. 1

As individuals and groups spread misinformation on social media platforms, there is a greater need for physician health advocacy.2 We have learned through the COVID-19 pandemic that rapidly evolving information requires public-facing health experts to address misinformation and explain why healthcare providers and experts make certain recommendations.2 Physicians recognize the potential for benefit from crowdsourcing education, positive publicity, and increasing their reach to a larger platform.3

However, despite social media’s need for such expertise and these recognized benefits, many physicians are hesitant to engage on social media, citing lack of time, interest, or the proper skill set to use it effectively.3 Additional barriers may include uncertainty about employer policies, fear of saying something inaccurate or unprofessional, or inadvertently breaching patient privacy.3 While these are valid concerns, a strategic approach to curating a social media presence focuses less on the moments created by provocative tweets and more on the movement the author wishes to amplify. Here, we propose a framework for effective physician advocacy using a strategy we term Mission-Based Tweeting (MBT).

MISSION-BASED TWEETING

Physicians can use Twitter to engage large audiences.4 MBT focuses an individual’s central message by providing a framework upon which to build such engagement.5 The conceptual framework for a meaningful social media strategy through MBT is anchored on the principle that the impact of our Twitter content is more valuable than the number of followers.6 Using this framework, users begin by creating and defining their identity while engaging in meaningful online interactions. Over time, these interactions will lead to generating influence related to their established identity, which can ultimately impact the social micro-society.6 While an individual’s social media impact can be determined and reinforced through MBT, it remains important to know that MBT is not exemplified in one specific tweet, but rather in the body of work shared by an individual that continuously reinforces the mission.

TWEETING FOR THE MOMENT VS FOR THE MOVEMENT: USING MBT FOR ADVOCACY

Advocacy typically involves using one’s voice to publicly support a specific interest. With that in mind, health advocacy can be divided into two categories: (1) agency, which involves advancing the health of individual patients within a system, and (2) activism, which acts to advance the health of communities or populations or change the structure of the healthcare system.7 While many physicians accept agency as part of their day-to-day job, activism is often more difficult. For example, physicians hoping to engage in health advocacy may be unable to travel to their state or federal legislature buildings, or their employers may restrict their ability to interact with elected officials. The emergence of social media and digital technology has lowered these barriers and created more accessible opportunities for physicians to engage in advocacy efforts.

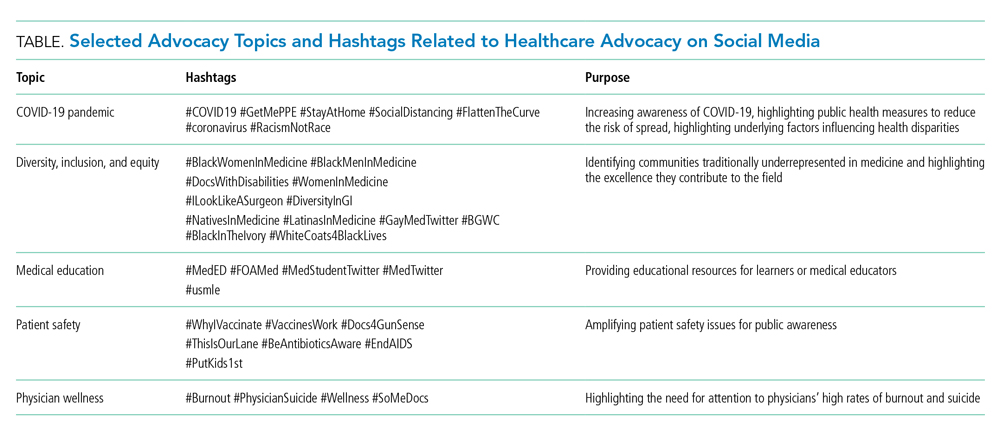

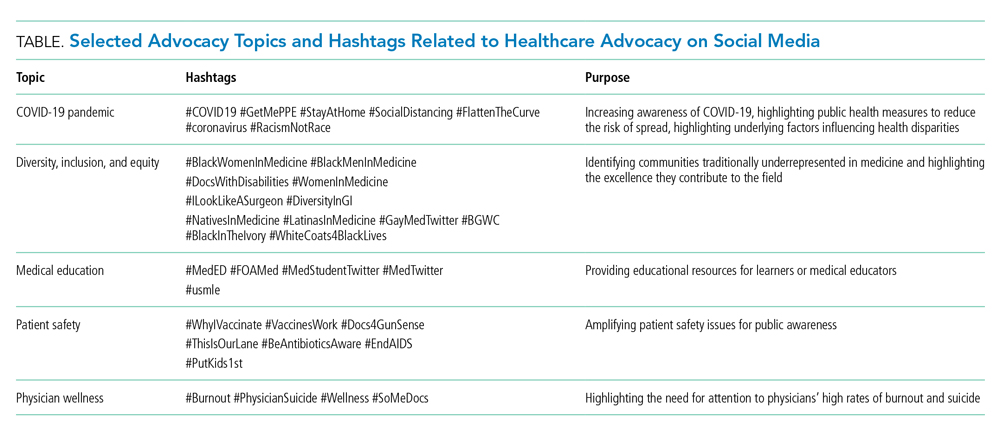

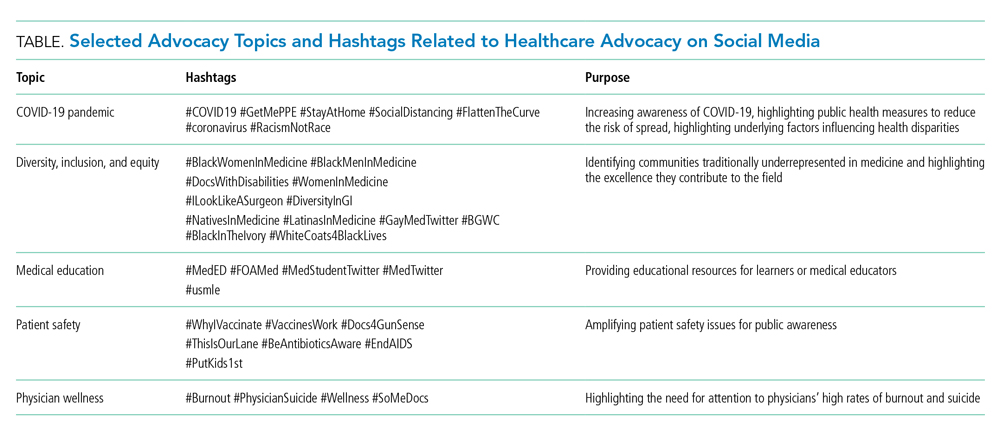

Social media can provide an opportunity for clinicians to engage with other healthcare professionals, creating movements that have far-reaching effects across the healthcare spectrum. These movements, often driven by common hashtags, have expanded greatly beyond their originators’ intent, thus demonstrating the power of social media for healthcare activism (Table).4 Physician advocacy can provide accurate information about medical conditions and treatments, dispel myths that may affect patient care, and draw attention to conditions that impact their ability to provide that care. For instance, physicians and medical students recently used Twitter during the COVID-19 pandemic to focus on the real consequences of lack of access to personal protective equipment during the pandemic (Table).8,9 In the past year, physicians have used Twitter to highlight how structural racism perpetuates racial disparities in COVID-19 and to call for action against police brutality and the killing of unarmed Black citizens. Such activism has led to media appearances and even congressional testimony—which has, in turn, provided even larger audiences for clinicians’ advocacy efforts.10 Physicians can also use MBT to advocate for the medical profession. Strategic, mission-based, social media campaigns have focused on including women; Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC); doctors with disabilities; and LGBTQ+ physicians in the narrative of what a doctor looks like (Table).11,12

When physicians consider their personal mission statement as it applies to their social media presence, it allows them to connect to something bigger than themselves, while helping guide them away from engagements that do not align with their personal or professional values. In this manner, MBT harnesses an individual’s authenticity and helps build their personal branding, which may ultimately result in more opportunities to advance their mission. In our experience, the constant delivery of mission-based content can even accelerate one’s professional work, help amplify others’ successes and voices, and ultimately lead to more meaningful engagement and activism.

However, it is important to note that there are potential downsides to engaging on social media, particularly for women and BIPOC users. For example, in a recent online survey, almost a quarter of physicians who responded reported personal attacks on social media, with one in six female physicians reporting sexual harassment.13 This risk may increase as an individual’s visibility and reach increase.

DEVELOP YOUR MISSION STATEMENT

To aid in MBT, we have found it useful to define your personal mission statement, which should succinctly describe your core values, the specific population or cause you serve, and your overarching goals or ideals. For example, someone interested in advocating for health justice might have the following mission statement: “To create and support a healthcare workforce and graduate medical education environment that strives for excellence and values Inclusion, Diversity, Access, and Equity as not only important, but necessary, for excellence.”14 Developing a personal mission statement permits more focus in all activities, including clinical, educational, administrative, or scholarship, and allows one to succinctly communicate important values with others.15 Communicating your personal mission statement concisely can improve the quality of your interactions with others and allows you to more precisely define the qualitative and quantitative impact of your social media engagement.

ENGAGING TO AMPLIFY YOUR MISSION

There are several options for creating and delivering effective mission-driven content on Twitter.16 We propose the Five A’s of MBT (Authenticity is key, Amplify other voices, Accelerate your work, Avoid arguments, Always be professional) to provide a general guide to ensuring that your tweets honor your mission (Figure). While each factor is important, we consider authenticity the most important as it guides consistency of the message, addresses your mission, and invites discussion. In this manner, even when physicians tweet about lived experiences or scientific data that may make some individuals uncomfortable, authenticity can still lead to meaningful engagement.17

There is synergy between amplifying other voices and accelerating your own work, as both provide an opportunity to highlight your specific advocacy interest. In the earlier example, the physician advocating for health justice may create a thread highlighting inequities in COVID-19 vaccination, including their own data and that of other health justice scholars, and in doing so, provide an invaluable repository of references or speakers for a future project.

We caution that not everyone will agree with your mission, so avoiding arguments and remaining professional in these interactions is paramount. Furthermore, it is also possible that a physician’s mission and opinions may not align with those of their employer, so it is important for social media users to review and clarify their employer’s social media policies to avoid violations and related repercussions. Physicians should tweet as if they were speaking into a microphone on the record, and authenticity should ground them into projecting the same personality online as they would offline.

CONCLUSION

We believe that, by the very nature of their chosen careers, physicians should step into the tension of advocacy. We acknowledge that physicians who are otherwise vocal advocates in other areas of life may be reluctant to engage on social media. However, if the measure of “success” on Twitter is meaningful interaction, sharing knowledge, and amplifying other voices according to a specific personal mission, MBT can be a useful framework. This is a call to action for hesitant physicians to take a leap and explore this platform, and for those already using social media to reevaluate their use and reflect on their mission. Physicians have been gifted a megaphone that can be used to combat misinformation, advocate for patients and the healthcare community, and advance needed discussions to benefit those in society who cannot speak for themselves. We advocate for physicians to look beyond the moment of a tweet and consider how your voice can contribute to a movement.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Vineet Arora for her contribution to early concept development for this manuscript and the JHM editorial staff for their productive feedback and editorial comments.

1. Riddick FA Jr. The code of medical ethics of the American Medical Association. Ochsner J. 2003;5(2):6-10. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2702.203139

2. Vraga EK, Bode L. Addressing COVID-19 misinformation on social media preemptively and responsively. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27(2):396-403. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2702.203139

3. Campbell L, Evans Y, Pumper M, Moreno MA. Social media use by physicians: a qualitative study of the new frontier of medicine. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2016;16:91. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-016-0327-y

4. Wetsman N. How Twitter is changing medical research. Nat Med. 2020;26(1):11-13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-019-0697-7

5. Shapiro M. Episode 107: Vinny Arora & Charlie Wray on Social Media & CVs. Explore The Space Podcast. https://www.explorethespaceshow.com/podcasting/vinny-arora-charlie-wray-on-cvs-social-media/

6. Varghese T. i4 (i to the 4th) is a strategy for #SoMe. Accessed April 22, 2021. https://twitter.com/TomVargheseJr/status/1027181443712081920?s=20

7. Dobson S, Voyer S, Regehr G. Perspective: agency and activism: rethinking health advocacy in the medical profession. Acad Med. 2012;87(9):1161-1164. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182621c25

8. #GetMePPE. Accessed April 22, 2021. https://twitter.com/hashtag/getmeppe?f=live

9. Ouyang H. At the front lines of coronavirus, turning to social media. The New York Times. March 18, 2020. Accessed April 22, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/18/well/live/coronavirus-doctors-facebook-twitter-social-media-covid.html

10. Blackstock U. Combining social media advocacy with health policy advocacy. Accessed April 22, 2021. https://twitter.com/uche_blackstock/status/1270413367761666048?s=20

11. Meeks LM, Liao P, Kim N. Using Twitter to promote awareness of disabilities in medicine. Med Educ. 2019;53(5):525-526. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13836

12. Nolen L. To all the little brown girls out there “you can’t be what you can’t see but I hope you see me now and that you see yourself in me.” Accessed April 22, 2021. https://twitter.com/LashNolen/status/1160901502266777600?s=20.

13. Pendergrast TR, Jain S, Trueger NS, Gottlieb M, Woitowich NC, Arora VM. Prevalence of personal attacks and sexual harassment of physicians on social media. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(4):550-552. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.7235

14. Marcelin JR. Personal mission statement. Accessed July 6, 2021. https://www.unmc.edu/intmed/residencies-fellowships/residency/diverse-taskforce/index.html.

15. Li S-TT, Frohna JG, Bostwick SB. Using your personal mission statement to INSPIRE and achieve success. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17(2):107-109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2016.11.010

16. Alton L. 7 tips for creating engaging content every day. Accessed April 22, 2021. https://business.twitter.com/en/blog/7-tips-creating-engaging-content-every-day.html

17. Boyd R. Is everyone reading this??! Accessed April 22, 2021. https://twitter.com/RheaBoydMD/status/1273006362679578625?s=20

“We, the members of the world community of physicians, solemnly commit ourselves to . . . advocate for social, economic, educational and political changes that ameliorate suffering and contribute to human well-being.”

— American Medical Association Oath of Professional Responsibility. 1

As individuals and groups spread misinformation on social media platforms, there is a greater need for physician health advocacy.2 We have learned through the COVID-19 pandemic that rapidly evolving information requires public-facing health experts to address misinformation and explain why healthcare providers and experts make certain recommendations.2 Physicians recognize the potential for benefit from crowdsourcing education, positive publicity, and increasing their reach to a larger platform.3

However, despite social media’s need for such expertise and these recognized benefits, many physicians are hesitant to engage on social media, citing lack of time, interest, or the proper skill set to use it effectively.3 Additional barriers may include uncertainty about employer policies, fear of saying something inaccurate or unprofessional, or inadvertently breaching patient privacy.3 While these are valid concerns, a strategic approach to curating a social media presence focuses less on the moments created by provocative tweets and more on the movement the author wishes to amplify. Here, we propose a framework for effective physician advocacy using a strategy we term Mission-Based Tweeting (MBT).

MISSION-BASED TWEETING

Physicians can use Twitter to engage large audiences.4 MBT focuses an individual’s central message by providing a framework upon which to build such engagement.5 The conceptual framework for a meaningful social media strategy through MBT is anchored on the principle that the impact of our Twitter content is more valuable than the number of followers.6 Using this framework, users begin by creating and defining their identity while engaging in meaningful online interactions. Over time, these interactions will lead to generating influence related to their established identity, which can ultimately impact the social micro-society.6 While an individual’s social media impact can be determined and reinforced through MBT, it remains important to know that MBT is not exemplified in one specific tweet, but rather in the body of work shared by an individual that continuously reinforces the mission.

TWEETING FOR THE MOMENT VS FOR THE MOVEMENT: USING MBT FOR ADVOCACY

Advocacy typically involves using one’s voice to publicly support a specific interest. With that in mind, health advocacy can be divided into two categories: (1) agency, which involves advancing the health of individual patients within a system, and (2) activism, which acts to advance the health of communities or populations or change the structure of the healthcare system.7 While many physicians accept agency as part of their day-to-day job, activism is often more difficult. For example, physicians hoping to engage in health advocacy may be unable to travel to their state or federal legislature buildings, or their employers may restrict their ability to interact with elected officials. The emergence of social media and digital technology has lowered these barriers and created more accessible opportunities for physicians to engage in advocacy efforts.

Social media can provide an opportunity for clinicians to engage with other healthcare professionals, creating movements that have far-reaching effects across the healthcare spectrum. These movements, often driven by common hashtags, have expanded greatly beyond their originators’ intent, thus demonstrating the power of social media for healthcare activism (Table).4 Physician advocacy can provide accurate information about medical conditions and treatments, dispel myths that may affect patient care, and draw attention to conditions that impact their ability to provide that care. For instance, physicians and medical students recently used Twitter during the COVID-19 pandemic to focus on the real consequences of lack of access to personal protective equipment during the pandemic (Table).8,9 In the past year, physicians have used Twitter to highlight how structural racism perpetuates racial disparities in COVID-19 and to call for action against police brutality and the killing of unarmed Black citizens. Such activism has led to media appearances and even congressional testimony—which has, in turn, provided even larger audiences for clinicians’ advocacy efforts.10 Physicians can also use MBT to advocate for the medical profession. Strategic, mission-based, social media campaigns have focused on including women; Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC); doctors with disabilities; and LGBTQ+ physicians in the narrative of what a doctor looks like (Table).11,12

When physicians consider their personal mission statement as it applies to their social media presence, it allows them to connect to something bigger than themselves, while helping guide them away from engagements that do not align with their personal or professional values. In this manner, MBT harnesses an individual’s authenticity and helps build their personal branding, which may ultimately result in more opportunities to advance their mission. In our experience, the constant delivery of mission-based content can even accelerate one’s professional work, help amplify others’ successes and voices, and ultimately lead to more meaningful engagement and activism.

However, it is important to note that there are potential downsides to engaging on social media, particularly for women and BIPOC users. For example, in a recent online survey, almost a quarter of physicians who responded reported personal attacks on social media, with one in six female physicians reporting sexual harassment.13 This risk may increase as an individual’s visibility and reach increase.

DEVELOP YOUR MISSION STATEMENT

To aid in MBT, we have found it useful to define your personal mission statement, which should succinctly describe your core values, the specific population or cause you serve, and your overarching goals or ideals. For example, someone interested in advocating for health justice might have the following mission statement: “To create and support a healthcare workforce and graduate medical education environment that strives for excellence and values Inclusion, Diversity, Access, and Equity as not only important, but necessary, for excellence.”14 Developing a personal mission statement permits more focus in all activities, including clinical, educational, administrative, or scholarship, and allows one to succinctly communicate important values with others.15 Communicating your personal mission statement concisely can improve the quality of your interactions with others and allows you to more precisely define the qualitative and quantitative impact of your social media engagement.

ENGAGING TO AMPLIFY YOUR MISSION

There are several options for creating and delivering effective mission-driven content on Twitter.16 We propose the Five A’s of MBT (Authenticity is key, Amplify other voices, Accelerate your work, Avoid arguments, Always be professional) to provide a general guide to ensuring that your tweets honor your mission (Figure). While each factor is important, we consider authenticity the most important as it guides consistency of the message, addresses your mission, and invites discussion. In this manner, even when physicians tweet about lived experiences or scientific data that may make some individuals uncomfortable, authenticity can still lead to meaningful engagement.17

There is synergy between amplifying other voices and accelerating your own work, as both provide an opportunity to highlight your specific advocacy interest. In the earlier example, the physician advocating for health justice may create a thread highlighting inequities in COVID-19 vaccination, including their own data and that of other health justice scholars, and in doing so, provide an invaluable repository of references or speakers for a future project.

We caution that not everyone will agree with your mission, so avoiding arguments and remaining professional in these interactions is paramount. Furthermore, it is also possible that a physician’s mission and opinions may not align with those of their employer, so it is important for social media users to review and clarify their employer’s social media policies to avoid violations and related repercussions. Physicians should tweet as if they were speaking into a microphone on the record, and authenticity should ground them into projecting the same personality online as they would offline.

CONCLUSION

We believe that, by the very nature of their chosen careers, physicians should step into the tension of advocacy. We acknowledge that physicians who are otherwise vocal advocates in other areas of life may be reluctant to engage on social media. However, if the measure of “success” on Twitter is meaningful interaction, sharing knowledge, and amplifying other voices according to a specific personal mission, MBT can be a useful framework. This is a call to action for hesitant physicians to take a leap and explore this platform, and for those already using social media to reevaluate their use and reflect on their mission. Physicians have been gifted a megaphone that can be used to combat misinformation, advocate for patients and the healthcare community, and advance needed discussions to benefit those in society who cannot speak for themselves. We advocate for physicians to look beyond the moment of a tweet and consider how your voice can contribute to a movement.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Vineet Arora for her contribution to early concept development for this manuscript and the JHM editorial staff for their productive feedback and editorial comments.

“We, the members of the world community of physicians, solemnly commit ourselves to . . . advocate for social, economic, educational and political changes that ameliorate suffering and contribute to human well-being.”

— American Medical Association Oath of Professional Responsibility. 1

As individuals and groups spread misinformation on social media platforms, there is a greater need for physician health advocacy.2 We have learned through the COVID-19 pandemic that rapidly evolving information requires public-facing health experts to address misinformation and explain why healthcare providers and experts make certain recommendations.2 Physicians recognize the potential for benefit from crowdsourcing education, positive publicity, and increasing their reach to a larger platform.3

However, despite social media’s need for such expertise and these recognized benefits, many physicians are hesitant to engage on social media, citing lack of time, interest, or the proper skill set to use it effectively.3 Additional barriers may include uncertainty about employer policies, fear of saying something inaccurate or unprofessional, or inadvertently breaching patient privacy.3 While these are valid concerns, a strategic approach to curating a social media presence focuses less on the moments created by provocative tweets and more on the movement the author wishes to amplify. Here, we propose a framework for effective physician advocacy using a strategy we term Mission-Based Tweeting (MBT).

MISSION-BASED TWEETING

Physicians can use Twitter to engage large audiences.4 MBT focuses an individual’s central message by providing a framework upon which to build such engagement.5 The conceptual framework for a meaningful social media strategy through MBT is anchored on the principle that the impact of our Twitter content is more valuable than the number of followers.6 Using this framework, users begin by creating and defining their identity while engaging in meaningful online interactions. Over time, these interactions will lead to generating influence related to their established identity, which can ultimately impact the social micro-society.6 While an individual’s social media impact can be determined and reinforced through MBT, it remains important to know that MBT is not exemplified in one specific tweet, but rather in the body of work shared by an individual that continuously reinforces the mission.

TWEETING FOR THE MOMENT VS FOR THE MOVEMENT: USING MBT FOR ADVOCACY

Advocacy typically involves using one’s voice to publicly support a specific interest. With that in mind, health advocacy can be divided into two categories: (1) agency, which involves advancing the health of individual patients within a system, and (2) activism, which acts to advance the health of communities or populations or change the structure of the healthcare system.7 While many physicians accept agency as part of their day-to-day job, activism is often more difficult. For example, physicians hoping to engage in health advocacy may be unable to travel to their state or federal legislature buildings, or their employers may restrict their ability to interact with elected officials. The emergence of social media and digital technology has lowered these barriers and created more accessible opportunities for physicians to engage in advocacy efforts.

Social media can provide an opportunity for clinicians to engage with other healthcare professionals, creating movements that have far-reaching effects across the healthcare spectrum. These movements, often driven by common hashtags, have expanded greatly beyond their originators’ intent, thus demonstrating the power of social media for healthcare activism (Table).4 Physician advocacy can provide accurate information about medical conditions and treatments, dispel myths that may affect patient care, and draw attention to conditions that impact their ability to provide that care. For instance, physicians and medical students recently used Twitter during the COVID-19 pandemic to focus on the real consequences of lack of access to personal protective equipment during the pandemic (Table).8,9 In the past year, physicians have used Twitter to highlight how structural racism perpetuates racial disparities in COVID-19 and to call for action against police brutality and the killing of unarmed Black citizens. Such activism has led to media appearances and even congressional testimony—which has, in turn, provided even larger audiences for clinicians’ advocacy efforts.10 Physicians can also use MBT to advocate for the medical profession. Strategic, mission-based, social media campaigns have focused on including women; Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC); doctors with disabilities; and LGBTQ+ physicians in the narrative of what a doctor looks like (Table).11,12

When physicians consider their personal mission statement as it applies to their social media presence, it allows them to connect to something bigger than themselves, while helping guide them away from engagements that do not align with their personal or professional values. In this manner, MBT harnesses an individual’s authenticity and helps build their personal branding, which may ultimately result in more opportunities to advance their mission. In our experience, the constant delivery of mission-based content can even accelerate one’s professional work, help amplify others’ successes and voices, and ultimately lead to more meaningful engagement and activism.

However, it is important to note that there are potential downsides to engaging on social media, particularly for women and BIPOC users. For example, in a recent online survey, almost a quarter of physicians who responded reported personal attacks on social media, with one in six female physicians reporting sexual harassment.13 This risk may increase as an individual’s visibility and reach increase.

DEVELOP YOUR MISSION STATEMENT

To aid in MBT, we have found it useful to define your personal mission statement, which should succinctly describe your core values, the specific population or cause you serve, and your overarching goals or ideals. For example, someone interested in advocating for health justice might have the following mission statement: “To create and support a healthcare workforce and graduate medical education environment that strives for excellence and values Inclusion, Diversity, Access, and Equity as not only important, but necessary, for excellence.”14 Developing a personal mission statement permits more focus in all activities, including clinical, educational, administrative, or scholarship, and allows one to succinctly communicate important values with others.15 Communicating your personal mission statement concisely can improve the quality of your interactions with others and allows you to more precisely define the qualitative and quantitative impact of your social media engagement.

ENGAGING TO AMPLIFY YOUR MISSION

There are several options for creating and delivering effective mission-driven content on Twitter.16 We propose the Five A’s of MBT (Authenticity is key, Amplify other voices, Accelerate your work, Avoid arguments, Always be professional) to provide a general guide to ensuring that your tweets honor your mission (Figure). While each factor is important, we consider authenticity the most important as it guides consistency of the message, addresses your mission, and invites discussion. In this manner, even when physicians tweet about lived experiences or scientific data that may make some individuals uncomfortable, authenticity can still lead to meaningful engagement.17

There is synergy between amplifying other voices and accelerating your own work, as both provide an opportunity to highlight your specific advocacy interest. In the earlier example, the physician advocating for health justice may create a thread highlighting inequities in COVID-19 vaccination, including their own data and that of other health justice scholars, and in doing so, provide an invaluable repository of references or speakers for a future project.

We caution that not everyone will agree with your mission, so avoiding arguments and remaining professional in these interactions is paramount. Furthermore, it is also possible that a physician’s mission and opinions may not align with those of their employer, so it is important for social media users to review and clarify their employer’s social media policies to avoid violations and related repercussions. Physicians should tweet as if they were speaking into a microphone on the record, and authenticity should ground them into projecting the same personality online as they would offline.

CONCLUSION

We believe that, by the very nature of their chosen careers, physicians should step into the tension of advocacy. We acknowledge that physicians who are otherwise vocal advocates in other areas of life may be reluctant to engage on social media. However, if the measure of “success” on Twitter is meaningful interaction, sharing knowledge, and amplifying other voices according to a specific personal mission, MBT can be a useful framework. This is a call to action for hesitant physicians to take a leap and explore this platform, and for those already using social media to reevaluate their use and reflect on their mission. Physicians have been gifted a megaphone that can be used to combat misinformation, advocate for patients and the healthcare community, and advance needed discussions to benefit those in society who cannot speak for themselves. We advocate for physicians to look beyond the moment of a tweet and consider how your voice can contribute to a movement.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Vineet Arora for her contribution to early concept development for this manuscript and the JHM editorial staff for their productive feedback and editorial comments.

1. Riddick FA Jr. The code of medical ethics of the American Medical Association. Ochsner J. 2003;5(2):6-10. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2702.203139

2. Vraga EK, Bode L. Addressing COVID-19 misinformation on social media preemptively and responsively. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27(2):396-403. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2702.203139

3. Campbell L, Evans Y, Pumper M, Moreno MA. Social media use by physicians: a qualitative study of the new frontier of medicine. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2016;16:91. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-016-0327-y

4. Wetsman N. How Twitter is changing medical research. Nat Med. 2020;26(1):11-13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-019-0697-7

5. Shapiro M. Episode 107: Vinny Arora & Charlie Wray on Social Media & CVs. Explore The Space Podcast. https://www.explorethespaceshow.com/podcasting/vinny-arora-charlie-wray-on-cvs-social-media/

6. Varghese T. i4 (i to the 4th) is a strategy for #SoMe. Accessed April 22, 2021. https://twitter.com/TomVargheseJr/status/1027181443712081920?s=20

7. Dobson S, Voyer S, Regehr G. Perspective: agency and activism: rethinking health advocacy in the medical profession. Acad Med. 2012;87(9):1161-1164. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182621c25

8. #GetMePPE. Accessed April 22, 2021. https://twitter.com/hashtag/getmeppe?f=live

9. Ouyang H. At the front lines of coronavirus, turning to social media. The New York Times. March 18, 2020. Accessed April 22, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/18/well/live/coronavirus-doctors-facebook-twitter-social-media-covid.html

10. Blackstock U. Combining social media advocacy with health policy advocacy. Accessed April 22, 2021. https://twitter.com/uche_blackstock/status/1270413367761666048?s=20

11. Meeks LM, Liao P, Kim N. Using Twitter to promote awareness of disabilities in medicine. Med Educ. 2019;53(5):525-526. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13836

12. Nolen L. To all the little brown girls out there “you can’t be what you can’t see but I hope you see me now and that you see yourself in me.” Accessed April 22, 2021. https://twitter.com/LashNolen/status/1160901502266777600?s=20.

13. Pendergrast TR, Jain S, Trueger NS, Gottlieb M, Woitowich NC, Arora VM. Prevalence of personal attacks and sexual harassment of physicians on social media. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(4):550-552. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.7235

14. Marcelin JR. Personal mission statement. Accessed July 6, 2021. https://www.unmc.edu/intmed/residencies-fellowships/residency/diverse-taskforce/index.html.

15. Li S-TT, Frohna JG, Bostwick SB. Using your personal mission statement to INSPIRE and achieve success. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17(2):107-109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2016.11.010

16. Alton L. 7 tips for creating engaging content every day. Accessed April 22, 2021. https://business.twitter.com/en/blog/7-tips-creating-engaging-content-every-day.html

17. Boyd R. Is everyone reading this??! Accessed April 22, 2021. https://twitter.com/RheaBoydMD/status/1273006362679578625?s=20

1. Riddick FA Jr. The code of medical ethics of the American Medical Association. Ochsner J. 2003;5(2):6-10. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2702.203139

2. Vraga EK, Bode L. Addressing COVID-19 misinformation on social media preemptively and responsively. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27(2):396-403. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2702.203139

3. Campbell L, Evans Y, Pumper M, Moreno MA. Social media use by physicians: a qualitative study of the new frontier of medicine. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2016;16:91. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-016-0327-y

4. Wetsman N. How Twitter is changing medical research. Nat Med. 2020;26(1):11-13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-019-0697-7

5. Shapiro M. Episode 107: Vinny Arora & Charlie Wray on Social Media & CVs. Explore The Space Podcast. https://www.explorethespaceshow.com/podcasting/vinny-arora-charlie-wray-on-cvs-social-media/

6. Varghese T. i4 (i to the 4th) is a strategy for #SoMe. Accessed April 22, 2021. https://twitter.com/TomVargheseJr/status/1027181443712081920?s=20

7. Dobson S, Voyer S, Regehr G. Perspective: agency and activism: rethinking health advocacy in the medical profession. Acad Med. 2012;87(9):1161-1164. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182621c25

8. #GetMePPE. Accessed April 22, 2021. https://twitter.com/hashtag/getmeppe?f=live

9. Ouyang H. At the front lines of coronavirus, turning to social media. The New York Times. March 18, 2020. Accessed April 22, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/18/well/live/coronavirus-doctors-facebook-twitter-social-media-covid.html

10. Blackstock U. Combining social media advocacy with health policy advocacy. Accessed April 22, 2021. https://twitter.com/uche_blackstock/status/1270413367761666048?s=20

11. Meeks LM, Liao P, Kim N. Using Twitter to promote awareness of disabilities in medicine. Med Educ. 2019;53(5):525-526. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13836

12. Nolen L. To all the little brown girls out there “you can’t be what you can’t see but I hope you see me now and that you see yourself in me.” Accessed April 22, 2021. https://twitter.com/LashNolen/status/1160901502266777600?s=20.

13. Pendergrast TR, Jain S, Trueger NS, Gottlieb M, Woitowich NC, Arora VM. Prevalence of personal attacks and sexual harassment of physicians on social media. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(4):550-552. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.7235

14. Marcelin JR. Personal mission statement. Accessed July 6, 2021. https://www.unmc.edu/intmed/residencies-fellowships/residency/diverse-taskforce/index.html.

15. Li S-TT, Frohna JG, Bostwick SB. Using your personal mission statement to INSPIRE and achieve success. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17(2):107-109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2016.11.010

16. Alton L. 7 tips for creating engaging content every day. Accessed April 22, 2021. https://business.twitter.com/en/blog/7-tips-creating-engaging-content-every-day.html

17. Boyd R. Is everyone reading this??! Accessed April 22, 2021. https://twitter.com/RheaBoydMD/status/1273006362679578625?s=20

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Leveling the Playing Field: Accounting for Academic Productivity During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Professional upheavals caused by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic have affected the academic productivity of many physicians. This is due in part to rapid changes in clinical care and medical education: physician-researchers have been redeployed to frontline clinical care; clinician-educators have been forced to rapidly transition in-person curricula to virtual platforms; and primary care physicians and subspecialists have been forced to transition to telehealth-based practices. In addition to these changes in clinical and educational responsibilities, the COVID-19 pandemic has substantially altered the personal lives of physicians. During the height of the pandemic, clinicians simultaneously wrestled with a lack of available childcare, unexpected home-schooling responsibilities, decreased income, and many other COVID-19-related stresses.1 Additionally, the ever-present “second pandemic” of structural racism, persistent health disparities, and racial inequity has further increased the personal and professional demands facing academic faculty.2

In particular, the pandemic has placed personal and professional pressure on female and minority faculty members. In spite of these pressures, however, the academic promotions process still requires rigid accounting of scholarly productivity. As the focus of academic practices has shifted to support clinical care during the pandemic, scholarly productivity has suffered for clinicians on the frontline. As a result, academic clinical faculty have expressed significant stress and concerns about failing to meet benchmarks for promotion (eg, publications, curricula development, national presentations). To counter these shifts (and the inherent inequity that they create for female clinicians and for men and women who are Black, Indigenous, and/or of color), academic institutions should not only recognize the effects the COVID-19 pandemic has had on faculty, but also adopt immediate solutions to more equitably account for such disruptions to academic portfolios. In this paper, we explore populations whose career trajectories are most at-risk and propose a framework to capture novel and nontraditional contributions while also acknowledging the rapid changes the COVID-19 pandemic has brought to academic medicine.

POPULATIONS AT RISK FOR CAREER DISRUPTION

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, physician mothers, underrepresented racial/ethnic minority groups, and junior faculty were most at-risk for career disruptions. The closure of daycare facilities and schools and shift to online learning resulting from the pandemic, along with the common challenges of parenting, have taken a significant toll on the lives of working parents. Because women tend to carry a disproportionate share of childcare and household responsibilities, these changes have inequitably leveraged themselves as a “mommy tax” on working women.3,4

As underrepresented medicine faculty (particularly Black, Hispanic, Latino, and Native American clinicians) comprise only 8% of the academic medical workforce,they currently face a variety of personal and professional challenges.5 This is especially true for Black and Latinx physicians who have been experiencing an increased COVID-19 burden in their communities, while concurrently fighting entrenched structural racism and police violence. In academia, these challenges have worsened because of the “minority tax”—the toll of often uncompensated extra responsibilities (time or money) placed on minority faculty in the name of achieving diversity. The unintended consequences of these responsibilities result in having fewer mentors,6 caring for underserved populations,7 and performing more clinical care8 than non-underrepresented minority faculty. Because minority faculty are unlikely to be in leadership positions, it is reasonable to conclude they have been shouldering heavier clinical obligations and facing greater career disruption of scholarly work due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Junior faculty (eg, instructors and assistant professors) also remain professionally vulnerable during the COVID-19 pandemic. Because junior faculty are often more clinically focused and less likely to hold leadership positions than senior faculty, they are more likely to have assumed frontline clinical positions, which come at the expense of academic work. Junior faculty are also at a critical building phase in their academic career—a time when they benefit from the opportunity to share their scholarly work and network at conferences. Unfortunately, many conferences have been canceled or moved to a virtual platform. Given that some institutions may be freezing academic funding for conferences due to budgetary shortfalls from the pandemic, junior faculty may be particularly at risk if they are not able to present their work. In addition, junior faculty often face disproportionate struggles at home, trying to balance demands of work and caring for young children. Considering the unique needs of each of these groups, it is especially important to consider intersectionality, or the compounded issues for individuals who exist in multiple disproportionately affected groups (eg, a Black female junior faculty member who is also a mother).

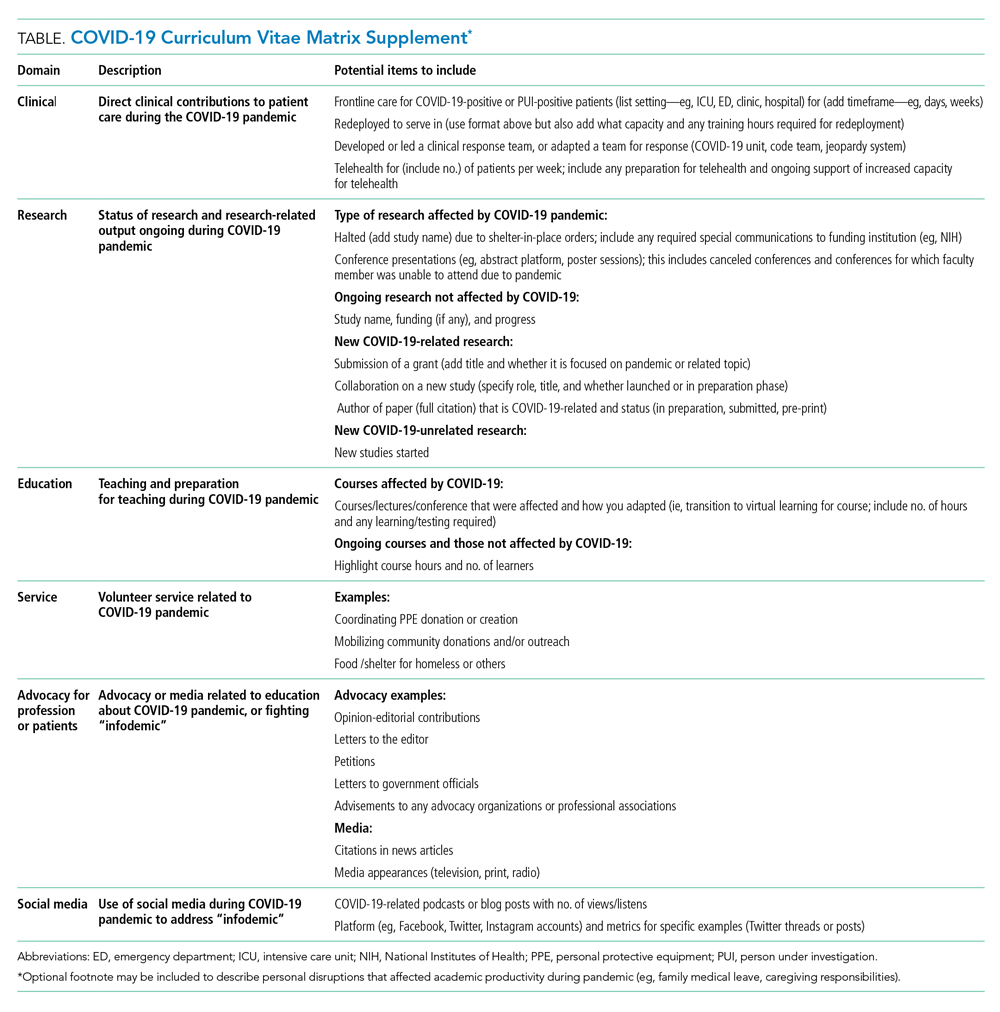

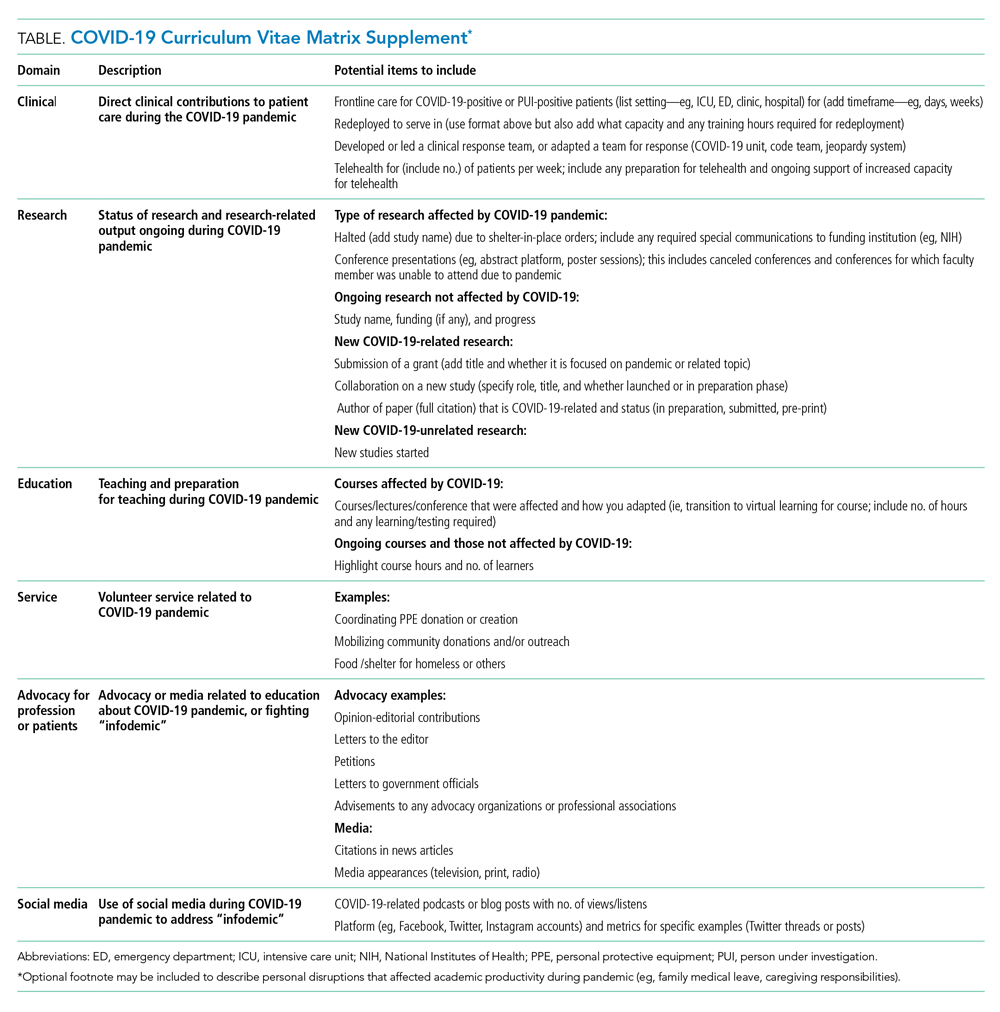

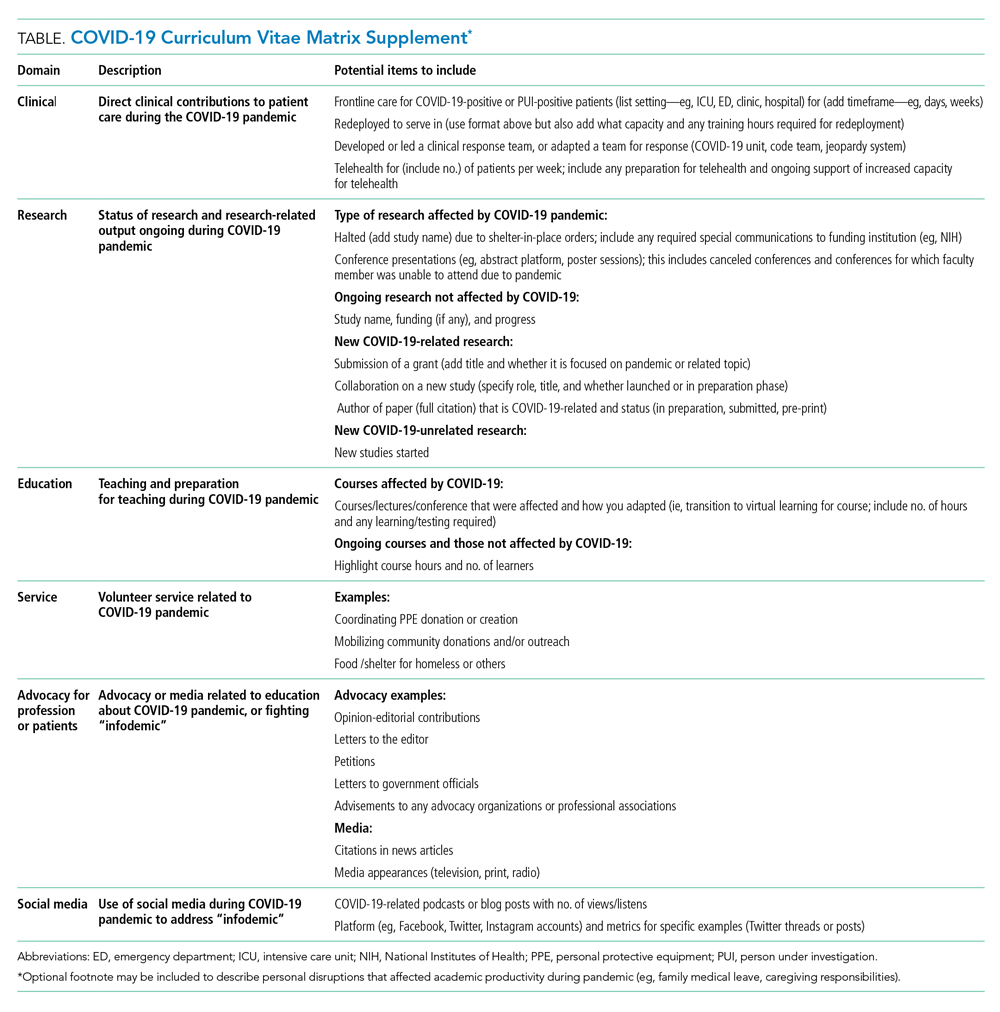

THE COVID-19-CURRICULUM VITAE MATRIX

The typical format of a professional curriculum vitae (CV) at most academic institutions does not allow one to document potential disruptions or novel contributions, including those that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic. As a group of academic clinicians, educators, and researchers whose careers have been affected by the pandemic, we created a COVID-19 CV matrix, a potential framework to serve as a supplement for faculty. In this matrix, faculty members may document their contributions, disruptions that affected their work, and caregiving responsibilities during this time period, while also providing a rubric for promotions and tenure committees to equitably evaluate the pandemic period on an academic CV. Our COVID-19 CV matrix consists of six domains: (1) clinical care, (2) research, (3) education, (4) service, (5) advocacy/media, and (6) social media. These domains encompass traditional and nontraditional contributions made by healthcare professionals during the pandemic (Table). This matrix broadens the ability of both faculty and institutions to determine the actual impact of individuals during the pandemic.

ACCOUNT FOR YOUR (NEW) IMPACT

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, academic faculty have been innovative, contributing in novel ways not routinely captured by promotions committees—eg, the digital health researcher who now directs the telemedicine response for their institution and the health disparities researcher who now leads daily webinar sessions on structural racism to medical students. Other novel contributions include advancing COVID-19 innovations and engaging in media and community advocacy (eg, organizing large-scale donations of equipment and funds to support organizations in need). While such nontraditional contributions may not have been readily captured or thought “CV worthy” in the past, faculty should now account for them. More importantly, promotions committees need to recognize that these pivots or alterations in career paths are not signals of professional failure, but rather evidence of a shifting landscape and the respective response of the individual. Furthermore, because these pivots often help fulfill an institutional mission, they are impactful.

ACKNOWLEDGE THE DISRUPTION

It is important for promotions and tenure committees to recognize the impact and disruption COVID-19 has had on traditional academic work, acknowledging the time and energy required for a faculty member to make needed work adjustments. This enables a leader to better assess how a faculty member’s academic portfolio has been affected. For example, researchers have had to halt studies, medical educators have had to redevelop and transition curricula to virtual platforms, and physicians have had to discontinue clinician quality improvement initiatives due to competing hospital priorities. Faculty members who document such unintentional alterations in their academic career path can explain to their institution how they have continued to positively influence their field and the community during the pandemic. This approach is analogous to the current model of accounting for clinical time when judging faculty members’ contributions in scholarly achievement.

The COVID-19 CV matrix has the potential to be annotated to explain the burden of one’s personal situation, which is often “invisible” in the professional environment. For example, many physicians have had to assume additional childcare responsibilities, tend to sick family members, friends, and even themselves. It is also possible that a faculty member has a partner who is also an essential worker, one who had to self-isolate due to COVID-19 exposure or illness, or who has been working overtime due to high patient volumes.

INSTITUTIONAL RESPONSE

How can institutions respond to the altered academic landscape caused by the COVID-19 pandemic? Promotions committees typically have two main tools at their disposal: adjusting the tenure clock or the benchmarks. Extending the period of time available to qualify for tenure is commonplace in the “publish-or-perish” academic tracks of university research professors. Clock adjustments are typically granted to faculty following the birth of a child or for other specific family- or health-related hardships, in accordance with the Family and Medical Leave Act. Unfortunately, tenure-clock extensions for female faculty members can exacerbate gender inequity: Data on tenure-clock extensions show a higher rate of tenure granted to male faculty compared to female faculty.9 For this reason, it is also important to explore adjustments or modifications to benchmark criteria. This could be accomplished by broadening the criteria for promotion, recognizing that impact occurs in many forms, thereby enabling meeting a benchmark. It can also occur by examining the trajectory of an individual within a promotion pathway before it was disrupted to determine impact. To avoid exacerbating social and gender inequities within academia, institutions should use these professional levers and create new ones to provide parity and equality across the promotional playing field. While the CV matrix openly acknowledges the disruptions and tangents the COVID-19 pandemic has had on academic careers, it remains important for academic institutions to recognize these disruptions and innovate the manner in which they acknowledge scholarly contributions.

Conclusion

While academic rigidity and known social taxes (minority and mommy taxes) are particularly problematic in the current climate, these issues have always been at play in evaluating academic success. Improved documentation of novel contributions, disruptions, caregiving, and other challenges can enable more holistic and timely professional advancement for all faculty, regardless of their sex, race, ethnicity, or social background. Ultimately, we hope this framework initiates further conversations among academic institutions on how to define productivity in an age where journal impact factor or number of publications is not the fullest measure of one’s impact in their field.

1. Jones Y, Durand V, Morton K, et al; ADVANCE PHM Steering Committee. Collateral damage: how covid-19 is adversely impacting women physicians. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(8):507-509. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3470

2. Manning KD. When grief and crises intersect: perspectives of a black physician in the time of two pandemics. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(9):566-567. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3481

3. Cohen P, Hsu T. Pandemic could scar a generation of working mothers. New York Times. Published June 3, 2020. Updated June 30, 2020. Accessed November 11, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/03/business/economy/coronavirus-working-women.html

4. Cain Miller C. Nearly half of men say they do most of the home schooling. 3 percent of women agree. Published May 6, 2020. Updated May 8, 2020. Accessed November 11, 2020. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/06/upshot/pandemic-chores-homeschooling-gender.html

5. Rodríguez JE, Campbell KM, Pololi LH. Addressing disparities in academic medicine: what of the minority tax? BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-015-0290-9

6. Lewellen-Williams C, Johnson VA, Deloney LA, Thomas BR, Goyol A, Henry-Tillman R. The POD: a new model for mentoring underrepresented minority faculty. Acad Med. 2006;81(3):275-279. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200603000-00020

7. Pololi LH, Evans AT, Gibbs BK, Krupat E, Brennan RT, Civian JT. The experience of minority faculty who are underrepresented in medicine, at 26 representative U.S. medical schools. Acad Med. 2013;88(9):1308-1314. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0b013e31829eefff

8. Richert A, Campbell K, Rodríguez J, Borowsky IW, Parikh R, Colwell A. ACU workforce column: expanding and supporting the health care workforce. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24(4):1423-1431. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2013.0162

9. Woitowich NC, Jain S, Arora VM, Joffe H. COVID-19 threatens progress toward gender equity within academic medicine. Acad Med. 2020;29:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003782. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000003782

Professional upheavals caused by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic have affected the academic productivity of many physicians. This is due in part to rapid changes in clinical care and medical education: physician-researchers have been redeployed to frontline clinical care; clinician-educators have been forced to rapidly transition in-person curricula to virtual platforms; and primary care physicians and subspecialists have been forced to transition to telehealth-based practices. In addition to these changes in clinical and educational responsibilities, the COVID-19 pandemic has substantially altered the personal lives of physicians. During the height of the pandemic, clinicians simultaneously wrestled with a lack of available childcare, unexpected home-schooling responsibilities, decreased income, and many other COVID-19-related stresses.1 Additionally, the ever-present “second pandemic” of structural racism, persistent health disparities, and racial inequity has further increased the personal and professional demands facing academic faculty.2

In particular, the pandemic has placed personal and professional pressure on female and minority faculty members. In spite of these pressures, however, the academic promotions process still requires rigid accounting of scholarly productivity. As the focus of academic practices has shifted to support clinical care during the pandemic, scholarly productivity has suffered for clinicians on the frontline. As a result, academic clinical faculty have expressed significant stress and concerns about failing to meet benchmarks for promotion (eg, publications, curricula development, national presentations). To counter these shifts (and the inherent inequity that they create for female clinicians and for men and women who are Black, Indigenous, and/or of color), academic institutions should not only recognize the effects the COVID-19 pandemic has had on faculty, but also adopt immediate solutions to more equitably account for such disruptions to academic portfolios. In this paper, we explore populations whose career trajectories are most at-risk and propose a framework to capture novel and nontraditional contributions while also acknowledging the rapid changes the COVID-19 pandemic has brought to academic medicine.

POPULATIONS AT RISK FOR CAREER DISRUPTION

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, physician mothers, underrepresented racial/ethnic minority groups, and junior faculty were most at-risk for career disruptions. The closure of daycare facilities and schools and shift to online learning resulting from the pandemic, along with the common challenges of parenting, have taken a significant toll on the lives of working parents. Because women tend to carry a disproportionate share of childcare and household responsibilities, these changes have inequitably leveraged themselves as a “mommy tax” on working women.3,4

As underrepresented medicine faculty (particularly Black, Hispanic, Latino, and Native American clinicians) comprise only 8% of the academic medical workforce,they currently face a variety of personal and professional challenges.5 This is especially true for Black and Latinx physicians who have been experiencing an increased COVID-19 burden in their communities, while concurrently fighting entrenched structural racism and police violence. In academia, these challenges have worsened because of the “minority tax”—the toll of often uncompensated extra responsibilities (time or money) placed on minority faculty in the name of achieving diversity. The unintended consequences of these responsibilities result in having fewer mentors,6 caring for underserved populations,7 and performing more clinical care8 than non-underrepresented minority faculty. Because minority faculty are unlikely to be in leadership positions, it is reasonable to conclude they have been shouldering heavier clinical obligations and facing greater career disruption of scholarly work due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Junior faculty (eg, instructors and assistant professors) also remain professionally vulnerable during the COVID-19 pandemic. Because junior faculty are often more clinically focused and less likely to hold leadership positions than senior faculty, they are more likely to have assumed frontline clinical positions, which come at the expense of academic work. Junior faculty are also at a critical building phase in their academic career—a time when they benefit from the opportunity to share their scholarly work and network at conferences. Unfortunately, many conferences have been canceled or moved to a virtual platform. Given that some institutions may be freezing academic funding for conferences due to budgetary shortfalls from the pandemic, junior faculty may be particularly at risk if they are not able to present their work. In addition, junior faculty often face disproportionate struggles at home, trying to balance demands of work and caring for young children. Considering the unique needs of each of these groups, it is especially important to consider intersectionality, or the compounded issues for individuals who exist in multiple disproportionately affected groups (eg, a Black female junior faculty member who is also a mother).

THE COVID-19-CURRICULUM VITAE MATRIX

The typical format of a professional curriculum vitae (CV) at most academic institutions does not allow one to document potential disruptions or novel contributions, including those that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic. As a group of academic clinicians, educators, and researchers whose careers have been affected by the pandemic, we created a COVID-19 CV matrix, a potential framework to serve as a supplement for faculty. In this matrix, faculty members may document their contributions, disruptions that affected their work, and caregiving responsibilities during this time period, while also providing a rubric for promotions and tenure committees to equitably evaluate the pandemic period on an academic CV. Our COVID-19 CV matrix consists of six domains: (1) clinical care, (2) research, (3) education, (4) service, (5) advocacy/media, and (6) social media. These domains encompass traditional and nontraditional contributions made by healthcare professionals during the pandemic (Table). This matrix broadens the ability of both faculty and institutions to determine the actual impact of individuals during the pandemic.

ACCOUNT FOR YOUR (NEW) IMPACT

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, academic faculty have been innovative, contributing in novel ways not routinely captured by promotions committees—eg, the digital health researcher who now directs the telemedicine response for their institution and the health disparities researcher who now leads daily webinar sessions on structural racism to medical students. Other novel contributions include advancing COVID-19 innovations and engaging in media and community advocacy (eg, organizing large-scale donations of equipment and funds to support organizations in need). While such nontraditional contributions may not have been readily captured or thought “CV worthy” in the past, faculty should now account for them. More importantly, promotions committees need to recognize that these pivots or alterations in career paths are not signals of professional failure, but rather evidence of a shifting landscape and the respective response of the individual. Furthermore, because these pivots often help fulfill an institutional mission, they are impactful.

ACKNOWLEDGE THE DISRUPTION

It is important for promotions and tenure committees to recognize the impact and disruption COVID-19 has had on traditional academic work, acknowledging the time and energy required for a faculty member to make needed work adjustments. This enables a leader to better assess how a faculty member’s academic portfolio has been affected. For example, researchers have had to halt studies, medical educators have had to redevelop and transition curricula to virtual platforms, and physicians have had to discontinue clinician quality improvement initiatives due to competing hospital priorities. Faculty members who document such unintentional alterations in their academic career path can explain to their institution how they have continued to positively influence their field and the community during the pandemic. This approach is analogous to the current model of accounting for clinical time when judging faculty members’ contributions in scholarly achievement.

The COVID-19 CV matrix has the potential to be annotated to explain the burden of one’s personal situation, which is often “invisible” in the professional environment. For example, many physicians have had to assume additional childcare responsibilities, tend to sick family members, friends, and even themselves. It is also possible that a faculty member has a partner who is also an essential worker, one who had to self-isolate due to COVID-19 exposure or illness, or who has been working overtime due to high patient volumes.

INSTITUTIONAL RESPONSE

How can institutions respond to the altered academic landscape caused by the COVID-19 pandemic? Promotions committees typically have two main tools at their disposal: adjusting the tenure clock or the benchmarks. Extending the period of time available to qualify for tenure is commonplace in the “publish-or-perish” academic tracks of university research professors. Clock adjustments are typically granted to faculty following the birth of a child or for other specific family- or health-related hardships, in accordance with the Family and Medical Leave Act. Unfortunately, tenure-clock extensions for female faculty members can exacerbate gender inequity: Data on tenure-clock extensions show a higher rate of tenure granted to male faculty compared to female faculty.9 For this reason, it is also important to explore adjustments or modifications to benchmark criteria. This could be accomplished by broadening the criteria for promotion, recognizing that impact occurs in many forms, thereby enabling meeting a benchmark. It can also occur by examining the trajectory of an individual within a promotion pathway before it was disrupted to determine impact. To avoid exacerbating social and gender inequities within academia, institutions should use these professional levers and create new ones to provide parity and equality across the promotional playing field. While the CV matrix openly acknowledges the disruptions and tangents the COVID-19 pandemic has had on academic careers, it remains important for academic institutions to recognize these disruptions and innovate the manner in which they acknowledge scholarly contributions.

Conclusion

While academic rigidity and known social taxes (minority and mommy taxes) are particularly problematic in the current climate, these issues have always been at play in evaluating academic success. Improved documentation of novel contributions, disruptions, caregiving, and other challenges can enable more holistic and timely professional advancement for all faculty, regardless of their sex, race, ethnicity, or social background. Ultimately, we hope this framework initiates further conversations among academic institutions on how to define productivity in an age where journal impact factor or number of publications is not the fullest measure of one’s impact in their field.

Professional upheavals caused by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic have affected the academic productivity of many physicians. This is due in part to rapid changes in clinical care and medical education: physician-researchers have been redeployed to frontline clinical care; clinician-educators have been forced to rapidly transition in-person curricula to virtual platforms; and primary care physicians and subspecialists have been forced to transition to telehealth-based practices. In addition to these changes in clinical and educational responsibilities, the COVID-19 pandemic has substantially altered the personal lives of physicians. During the height of the pandemic, clinicians simultaneously wrestled with a lack of available childcare, unexpected home-schooling responsibilities, decreased income, and many other COVID-19-related stresses.1 Additionally, the ever-present “second pandemic” of structural racism, persistent health disparities, and racial inequity has further increased the personal and professional demands facing academic faculty.2

In particular, the pandemic has placed personal and professional pressure on female and minority faculty members. In spite of these pressures, however, the academic promotions process still requires rigid accounting of scholarly productivity. As the focus of academic practices has shifted to support clinical care during the pandemic, scholarly productivity has suffered for clinicians on the frontline. As a result, academic clinical faculty have expressed significant stress and concerns about failing to meet benchmarks for promotion (eg, publications, curricula development, national presentations). To counter these shifts (and the inherent inequity that they create for female clinicians and for men and women who are Black, Indigenous, and/or of color), academic institutions should not only recognize the effects the COVID-19 pandemic has had on faculty, but also adopt immediate solutions to more equitably account for such disruptions to academic portfolios. In this paper, we explore populations whose career trajectories are most at-risk and propose a framework to capture novel and nontraditional contributions while also acknowledging the rapid changes the COVID-19 pandemic has brought to academic medicine.

POPULATIONS AT RISK FOR CAREER DISRUPTION

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, physician mothers, underrepresented racial/ethnic minority groups, and junior faculty were most at-risk for career disruptions. The closure of daycare facilities and schools and shift to online learning resulting from the pandemic, along with the common challenges of parenting, have taken a significant toll on the lives of working parents. Because women tend to carry a disproportionate share of childcare and household responsibilities, these changes have inequitably leveraged themselves as a “mommy tax” on working women.3,4

As underrepresented medicine faculty (particularly Black, Hispanic, Latino, and Native American clinicians) comprise only 8% of the academic medical workforce,they currently face a variety of personal and professional challenges.5 This is especially true for Black and Latinx physicians who have been experiencing an increased COVID-19 burden in their communities, while concurrently fighting entrenched structural racism and police violence. In academia, these challenges have worsened because of the “minority tax”—the toll of often uncompensated extra responsibilities (time or money) placed on minority faculty in the name of achieving diversity. The unintended consequences of these responsibilities result in having fewer mentors,6 caring for underserved populations,7 and performing more clinical care8 than non-underrepresented minority faculty. Because minority faculty are unlikely to be in leadership positions, it is reasonable to conclude they have been shouldering heavier clinical obligations and facing greater career disruption of scholarly work due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Junior faculty (eg, instructors and assistant professors) also remain professionally vulnerable during the COVID-19 pandemic. Because junior faculty are often more clinically focused and less likely to hold leadership positions than senior faculty, they are more likely to have assumed frontline clinical positions, which come at the expense of academic work. Junior faculty are also at a critical building phase in their academic career—a time when they benefit from the opportunity to share their scholarly work and network at conferences. Unfortunately, many conferences have been canceled or moved to a virtual platform. Given that some institutions may be freezing academic funding for conferences due to budgetary shortfalls from the pandemic, junior faculty may be particularly at risk if they are not able to present their work. In addition, junior faculty often face disproportionate struggles at home, trying to balance demands of work and caring for young children. Considering the unique needs of each of these groups, it is especially important to consider intersectionality, or the compounded issues for individuals who exist in multiple disproportionately affected groups (eg, a Black female junior faculty member who is also a mother).

THE COVID-19-CURRICULUM VITAE MATRIX

The typical format of a professional curriculum vitae (CV) at most academic institutions does not allow one to document potential disruptions or novel contributions, including those that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic. As a group of academic clinicians, educators, and researchers whose careers have been affected by the pandemic, we created a COVID-19 CV matrix, a potential framework to serve as a supplement for faculty. In this matrix, faculty members may document their contributions, disruptions that affected their work, and caregiving responsibilities during this time period, while also providing a rubric for promotions and tenure committees to equitably evaluate the pandemic period on an academic CV. Our COVID-19 CV matrix consists of six domains: (1) clinical care, (2) research, (3) education, (4) service, (5) advocacy/media, and (6) social media. These domains encompass traditional and nontraditional contributions made by healthcare professionals during the pandemic (Table). This matrix broadens the ability of both faculty and institutions to determine the actual impact of individuals during the pandemic.

ACCOUNT FOR YOUR (NEW) IMPACT

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, academic faculty have been innovative, contributing in novel ways not routinely captured by promotions committees—eg, the digital health researcher who now directs the telemedicine response for their institution and the health disparities researcher who now leads daily webinar sessions on structural racism to medical students. Other novel contributions include advancing COVID-19 innovations and engaging in media and community advocacy (eg, organizing large-scale donations of equipment and funds to support organizations in need). While such nontraditional contributions may not have been readily captured or thought “CV worthy” in the past, faculty should now account for them. More importantly, promotions committees need to recognize that these pivots or alterations in career paths are not signals of professional failure, but rather evidence of a shifting landscape and the respective response of the individual. Furthermore, because these pivots often help fulfill an institutional mission, they are impactful.

ACKNOWLEDGE THE DISRUPTION

It is important for promotions and tenure committees to recognize the impact and disruption COVID-19 has had on traditional academic work, acknowledging the time and energy required for a faculty member to make needed work adjustments. This enables a leader to better assess how a faculty member’s academic portfolio has been affected. For example, researchers have had to halt studies, medical educators have had to redevelop and transition curricula to virtual platforms, and physicians have had to discontinue clinician quality improvement initiatives due to competing hospital priorities. Faculty members who document such unintentional alterations in their academic career path can explain to their institution how they have continued to positively influence their field and the community during the pandemic. This approach is analogous to the current model of accounting for clinical time when judging faculty members’ contributions in scholarly achievement.

The COVID-19 CV matrix has the potential to be annotated to explain the burden of one’s personal situation, which is often “invisible” in the professional environment. For example, many physicians have had to assume additional childcare responsibilities, tend to sick family members, friends, and even themselves. It is also possible that a faculty member has a partner who is also an essential worker, one who had to self-isolate due to COVID-19 exposure or illness, or who has been working overtime due to high patient volumes.

INSTITUTIONAL RESPONSE

How can institutions respond to the altered academic landscape caused by the COVID-19 pandemic? Promotions committees typically have two main tools at their disposal: adjusting the tenure clock or the benchmarks. Extending the period of time available to qualify for tenure is commonplace in the “publish-or-perish” academic tracks of university research professors. Clock adjustments are typically granted to faculty following the birth of a child or for other specific family- or health-related hardships, in accordance with the Family and Medical Leave Act. Unfortunately, tenure-clock extensions for female faculty members can exacerbate gender inequity: Data on tenure-clock extensions show a higher rate of tenure granted to male faculty compared to female faculty.9 For this reason, it is also important to explore adjustments or modifications to benchmark criteria. This could be accomplished by broadening the criteria for promotion, recognizing that impact occurs in many forms, thereby enabling meeting a benchmark. It can also occur by examining the trajectory of an individual within a promotion pathway before it was disrupted to determine impact. To avoid exacerbating social and gender inequities within academia, institutions should use these professional levers and create new ones to provide parity and equality across the promotional playing field. While the CV matrix openly acknowledges the disruptions and tangents the COVID-19 pandemic has had on academic careers, it remains important for academic institutions to recognize these disruptions and innovate the manner in which they acknowledge scholarly contributions.

Conclusion

While academic rigidity and known social taxes (minority and mommy taxes) are particularly problematic in the current climate, these issues have always been at play in evaluating academic success. Improved documentation of novel contributions, disruptions, caregiving, and other challenges can enable more holistic and timely professional advancement for all faculty, regardless of their sex, race, ethnicity, or social background. Ultimately, we hope this framework initiates further conversations among academic institutions on how to define productivity in an age where journal impact factor or number of publications is not the fullest measure of one’s impact in their field.

1. Jones Y, Durand V, Morton K, et al; ADVANCE PHM Steering Committee. Collateral damage: how covid-19 is adversely impacting women physicians. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(8):507-509. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3470

2. Manning KD. When grief and crises intersect: perspectives of a black physician in the time of two pandemics. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(9):566-567. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3481

3. Cohen P, Hsu T. Pandemic could scar a generation of working mothers. New York Times. Published June 3, 2020. Updated June 30, 2020. Accessed November 11, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/03/business/economy/coronavirus-working-women.html

4. Cain Miller C. Nearly half of men say they do most of the home schooling. 3 percent of women agree. Published May 6, 2020. Updated May 8, 2020. Accessed November 11, 2020. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/06/upshot/pandemic-chores-homeschooling-gender.html

5. Rodríguez JE, Campbell KM, Pololi LH. Addressing disparities in academic medicine: what of the minority tax? BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-015-0290-9

6. Lewellen-Williams C, Johnson VA, Deloney LA, Thomas BR, Goyol A, Henry-Tillman R. The POD: a new model for mentoring underrepresented minority faculty. Acad Med. 2006;81(3):275-279. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200603000-00020

7. Pololi LH, Evans AT, Gibbs BK, Krupat E, Brennan RT, Civian JT. The experience of minority faculty who are underrepresented in medicine, at 26 representative U.S. medical schools. Acad Med. 2013;88(9):1308-1314. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0b013e31829eefff

8. Richert A, Campbell K, Rodríguez J, Borowsky IW, Parikh R, Colwell A. ACU workforce column: expanding and supporting the health care workforce. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24(4):1423-1431. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2013.0162

9. Woitowich NC, Jain S, Arora VM, Joffe H. COVID-19 threatens progress toward gender equity within academic medicine. Acad Med. 2020;29:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003782. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000003782

1. Jones Y, Durand V, Morton K, et al; ADVANCE PHM Steering Committee. Collateral damage: how covid-19 is adversely impacting women physicians. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(8):507-509. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3470

2. Manning KD. When grief and crises intersect: perspectives of a black physician in the time of two pandemics. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(9):566-567. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3481

3. Cohen P, Hsu T. Pandemic could scar a generation of working mothers. New York Times. Published June 3, 2020. Updated June 30, 2020. Accessed November 11, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/03/business/economy/coronavirus-working-women.html

4. Cain Miller C. Nearly half of men say they do most of the home schooling. 3 percent of women agree. Published May 6, 2020. Updated May 8, 2020. Accessed November 11, 2020. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/06/upshot/pandemic-chores-homeschooling-gender.html

5. Rodríguez JE, Campbell KM, Pololi LH. Addressing disparities in academic medicine: what of the minority tax? BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-015-0290-9

6. Lewellen-Williams C, Johnson VA, Deloney LA, Thomas BR, Goyol A, Henry-Tillman R. The POD: a new model for mentoring underrepresented minority faculty. Acad Med. 2006;81(3):275-279. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200603000-00020

7. Pololi LH, Evans AT, Gibbs BK, Krupat E, Brennan RT, Civian JT. The experience of minority faculty who are underrepresented in medicine, at 26 representative U.S. medical schools. Acad Med. 2013;88(9):1308-1314. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0b013e31829eefff

8. Richert A, Campbell K, Rodríguez J, Borowsky IW, Parikh R, Colwell A. ACU workforce column: expanding and supporting the health care workforce. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24(4):1423-1431. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2013.0162