User login

Vaginal anomalies and their surgical correction

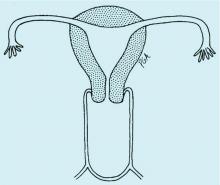

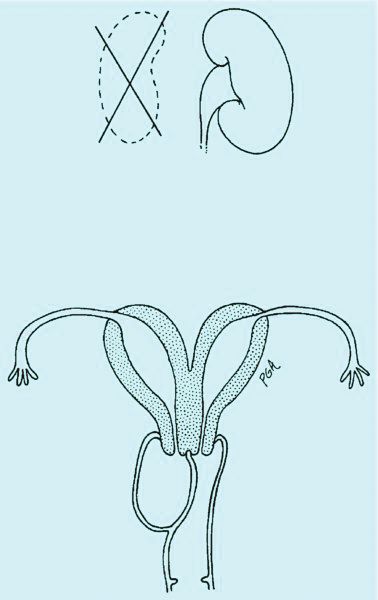

Congenital obstructive anomalies of the vagina are unusual and can be challenging to diagnose and manage. Two of the most challenging are obstructive hemivagina with ipsilateral renal agenesis (Figure 1a) and agenesis of the lower vagina (Figure 1b), the latter of which must be differentiated most commonly from imperforate hymen (Figure 1c). Evaluation and treatment of these anomalies is dependent upon the age of the patient, as well as the symptoms, and the timing of treatment should be individualized.

Agenesis of the lower vagina

Agenesis of the lower vagina and imperforate hymen may present either in the newborn period as a bulging introitus caused by mucocolpos from vaginal secretions stimulated by maternal estradiol or during adolescence at the time of menarche. In neonates, it often is best not to intervene when obstructive anomalies are suspected as long as there is no fever; pain; or compromise of respiration, urinary and bowel function, and other functionality. It will be easier to differentiate agenesis of the lower vagina and imperforate hymen – the latter of which is one of the most common obstructive lesions of the female genital tract – later on. And if the hymen remains imperforate, the mucus will be reabsorbed and the patient usually will remain asymptomatic until menarche.

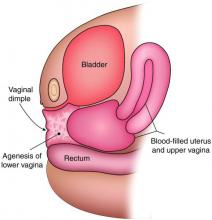

In the adolescent time period, both anomalies often are identified when the patient presents with pelvic pain – usually cyclic pelvic pain with primary amenorrhea. Because the onset of menses typically occurs 2-3 years after the onset of estrogenization and breast development, evaluating breast development can help us to determine the timing of expected menarche. An obstructive anomaly should be suspected in an adolescent who presents with pain during this time period, after evaluation for an acute abdomen (Figure 2a).

When a vaginal orifice is visualized upon evaluation of the external genitalia and separation of the labia, a higher anomaly such as a transverse vaginal septum should be suspected. When an introitus cannot be visualized, evaluation for an imperforate hymen or agenesis of the lower vagina is necessary (Figure 1b and 1c).

The simplest way to differentiate imperforate hymen from agenesis of the lower vagina is with visualization of the obstructing tissue on exam and usage of transperitoneal ultrasound. With the transducer placed on the vulva, we can evaluate the distance from the normal location of an introitus to the level of the obstruction. If the distance is in millimeters, then typically there is an imperforate hymen. If the distance is larger – more than several millimeters – then the differential diagnosis typically is agenesis of the lower vagina, an anomaly that results from abnormal development of the sinovaginal bulbs and vaginal plate.

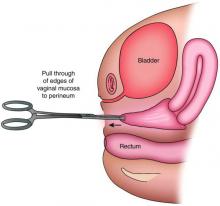

The distance as measured by transperitoneal ultrasound also will indicate whether or not pull-through vaginoplasty (Figure 2b) – our standard treatment for lower vaginal agenesis – is possible using native vaginal mucosa from the upper vagina. Most commonly, the distance is less than 5 cm and we are able to make a transverse incision where the hymenal ring should be located, carry the dissection to the upper vagina, drain the obstruction, and mobilize the upper vaginal mucosa, suturing it to the newly created introitus to formulate a patent vaginal tract.

A rectoabdominal examination similarly can be helpful in making the diagnosis of lower vaginal agenesis and in determining whether there is enough tissue available for a pull-through procedure (Figures 2a and 2b). Because patients with this anomaly generally have normal cyclic pituitary-ovarian-endometrial function at menarche, the upper vagina will distend with blood products and secretions that can be palpated on the rectoabdominal exam. If the obstructed vaginal tissue is not felt with the rectal finger at midline, the obstructed agenesis of the vagina probably is too high for a straightforward pull-through procedure. Alternatively, the patient may have a unicornuate system with agenesis of the lower vagina; in this case, the obstructed upper vaginal tissue will not be in the midline but off to one side. MRI also may be helpful for defining the pelvic anatomy.

The optimal timing for a pull-through vaginoplasty (Figure 2b) is when a large hematocolpos (Figure 2a) is present, as the blood acts as a natural expander of the native vaginal tissue, increasing the amount of tissue available for a primary reanastomosis. This emphasizes the importance of an accurate initial diagnosis. Too often, obstructions that are actually lower vaginal agenesis are presumed to be imperforate hymen, and the hematocolpos is subsequently evacuated after a transverse incision and dissection of excess tissue, causing the upper vagina to retract and shrink. This mistake can result in the formation of a fistulous tract from the previously obstructed upper vagina to the level of the introitus.

The vaginoplasty is carried out with the patient in the dorsal lithotomy position. A Foley catheter is placed into the bladder to avoid an inadvertent anterior entry into the posterior wall of the bladder, and the labia are grasped and pulled down and out.

The hymenal tissue should be visible. A transverse incision is made, with electrocautery, where the introitus should be located, and a dissection is carried out to reach the obstructed upper vaginal tissue. Care is needed to keep the dissection in the midline and avoid the bladder above and the rectum below. In cases in which it is difficult to identify the area of obstruction, intraoperative ultrasound can be helpful. A spinal needle with a 10-cc syringe also can be used to identify a track through which to access the fluid.

The linear incision then is made with electrocautery and the obstructed hemivagina is entered. Allis clamps are used to grasp the vaginal mucosa from the previously obstructed upper vagina to help identify the tissue that needs to be mobilized. The tissue then is further dissected to free the upper vagina, and the edges are pulled down to the level of the introitus with Allis clamps. “Relaxing” incisions are made at 1, 5,7, and 11 o’clock to avoid a circumferential scar. The upper vaginal mucosa is sewn to the newly created introitus with a 2-0 vicryl suture on a UR6 (a smaller curved urology needle).

When the distance from normal introitus location to obstruction is greater than 5 cm, we sometimes use vaginal dilators to lessen the distance and reach the obstruction for a pull-through procedure. Alternatively, the upper vagina may be mobilized from above either robotically or laparoscopically so that the upper vaginal mucosa may be pulled down without entering the bladder. Occasionally, with greater distances over 5 cm, the vaginoplasty may require utilization of a buccal mucosal graft or a bowel segment.

Intraoperative ultrasound can be especially helpful for locating the obstructed vagina in women with a unicornuate system because the upper vagina will not be in the midline and ultrasound can help determine the appropriate angle for dissection.

Prophylactic antibiotics initiated postoperatively are important with pull-through vaginoplasty, because the uterus and fallopian tubes may contain blood (an excellent growth media) and because there is a risk of bacteria ascending into what becomes an open system.

Postoperatively, we guide patients on the use of flexible Milex dilators (CooperSurgical) to ensure that the vagina heals without restenosis. The length of postoperative dilation therapy can vary from 2-12 months, depending on healing. The dilator is worn 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, and is removed only for urination, defecation, and cleaning. With adequate postoperative dilation, patients will have normal sexual and reproductive function, and vaginal delivery should be possible.

Obstructed hemivagina

An obstructed hemivagina, an uncommon Müllerian duct anomaly, occurs most often with ipsilateral renal agenesis and is commonly referred to as OHVIRA. Because the formation of the reproductive system is closely associated with the development of the urinary system, it is not unusual for renal anomalies to occur alongside Müllerian anomalies and vaginal anomalies. There should be a high index of suspicion for a reproductive tract anomaly in any patient known to have a horseshoe kidney, duplex collecting system, unilateral renal agenesis, or other renal anomaly.

Patients with obstructed hemivagina typically present in adolescence with pelvic pain or dysmenorrhea, and commonly are misdiagnosed as having endometriomas or vaginal cysts. On vaginal examination, the obstructed hemivagina may be visualized as a bulge coming from the lateral vaginal sidewall. While only one cervix is appreciated on a vaginal exam, an ultrasound examination often will show two uteri and two cervices. MRI also is helpful for diagnosis.

Obstructed hemivagina requires surgical correction to open the obstruction, excise the excess vaginal tissue, and create one vagina with access to the second cervix. Great care must be taken to avoid not only the bladder and rectum but the cervices. It is not unusual for the two cervices to be at different levels, with one cervix sharing medial aspects of the vaginal wall of the second vagina (Figure 1a). The tissue between the two cervices should be left in place to avoid compromising their blood supply.

We manage this anomaly primarily through a single-stage vaginoplasty. For the nonobstructed side to be visualized, a longitudinal incision into the obstructed hemivagina should be made at the point at which it is most easily palpated. As with agenesis of the lower vagina, the fluid to be drained tends to be old menstrual blood that is thick and dark brown. It is useful to set up two suction units at the time of surgery because tubing can become clogged.

The use of vaginal side wall retractors helps with visualization. Alternatively, I tend to use malleable abdominal wall retractors vaginally, as they can be bent to conform to the angle needed and come in different widths. When it is difficult to identify the area of obstruction, a spinal needle with a 10-cc syringe again can be used to identify a track for accessing the fluid. The linear incision then is made with electrocautery, and the obstructed hemivagina is entered.

Allis clamps are used to grasp the vaginal mucosa from the previously obstructed hemivagina to help identify the tissue that needs to be excised. Once the fluid is evacuated, a finger also can be placed into the obstructed vagina is help identify excess tissue. This three-dimensional elliptical area is similar to a septum but becomes the obstructed hemivagina as it attaches to the vaginal wall (Figure 1a).

Retrograde menses and endometriosis occur commonly with obstructive anomalies like obstructed hemivagina and agenesis of the lower vagina, but laparoscopy with the goal of treating endometriosis is not indicated. We discourage its use at the time of repair because there is evidence that almost all endometriosis will completely resorb on its own once the anomalies are corrected.1,2

As with repair of lower vagina agenesis, antibiotics to prevent an ascending infection should be taken after surgical correction of obstructed hemivagina. Patients with obstructed hemivagina can have a vaginal delivery if there are no other contraindications. Women with obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal anomaly have essentially two unicornuate systems and thus are at risk of breech presentation and preterm delivery.

Dr. Laufer is chief of the division of gynecology, codirector of the Center for Young Women’s Health, and director of the Boston Center for Endometriosis, all at Boston Children’s Hospital. He also is professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

References

1. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1986;154:39.

2. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2010;23(2):e89.

Congenital obstructive anomalies of the vagina are unusual and can be challenging to diagnose and manage. Two of the most challenging are obstructive hemivagina with ipsilateral renal agenesis (Figure 1a) and agenesis of the lower vagina (Figure 1b), the latter of which must be differentiated most commonly from imperforate hymen (Figure 1c). Evaluation and treatment of these anomalies is dependent upon the age of the patient, as well as the symptoms, and the timing of treatment should be individualized.

Agenesis of the lower vagina

Agenesis of the lower vagina and imperforate hymen may present either in the newborn period as a bulging introitus caused by mucocolpos from vaginal secretions stimulated by maternal estradiol or during adolescence at the time of menarche. In neonates, it often is best not to intervene when obstructive anomalies are suspected as long as there is no fever; pain; or compromise of respiration, urinary and bowel function, and other functionality. It will be easier to differentiate agenesis of the lower vagina and imperforate hymen – the latter of which is one of the most common obstructive lesions of the female genital tract – later on. And if the hymen remains imperforate, the mucus will be reabsorbed and the patient usually will remain asymptomatic until menarche.

In the adolescent time period, both anomalies often are identified when the patient presents with pelvic pain – usually cyclic pelvic pain with primary amenorrhea. Because the onset of menses typically occurs 2-3 years after the onset of estrogenization and breast development, evaluating breast development can help us to determine the timing of expected menarche. An obstructive anomaly should be suspected in an adolescent who presents with pain during this time period, after evaluation for an acute abdomen (Figure 2a).

When a vaginal orifice is visualized upon evaluation of the external genitalia and separation of the labia, a higher anomaly such as a transverse vaginal septum should be suspected. When an introitus cannot be visualized, evaluation for an imperforate hymen or agenesis of the lower vagina is necessary (Figure 1b and 1c).

The simplest way to differentiate imperforate hymen from agenesis of the lower vagina is with visualization of the obstructing tissue on exam and usage of transperitoneal ultrasound. With the transducer placed on the vulva, we can evaluate the distance from the normal location of an introitus to the level of the obstruction. If the distance is in millimeters, then typically there is an imperforate hymen. If the distance is larger – more than several millimeters – then the differential diagnosis typically is agenesis of the lower vagina, an anomaly that results from abnormal development of the sinovaginal bulbs and vaginal plate.

The distance as measured by transperitoneal ultrasound also will indicate whether or not pull-through vaginoplasty (Figure 2b) – our standard treatment for lower vaginal agenesis – is possible using native vaginal mucosa from the upper vagina. Most commonly, the distance is less than 5 cm and we are able to make a transverse incision where the hymenal ring should be located, carry the dissection to the upper vagina, drain the obstruction, and mobilize the upper vaginal mucosa, suturing it to the newly created introitus to formulate a patent vaginal tract.

A rectoabdominal examination similarly can be helpful in making the diagnosis of lower vaginal agenesis and in determining whether there is enough tissue available for a pull-through procedure (Figures 2a and 2b). Because patients with this anomaly generally have normal cyclic pituitary-ovarian-endometrial function at menarche, the upper vagina will distend with blood products and secretions that can be palpated on the rectoabdominal exam. If the obstructed vaginal tissue is not felt with the rectal finger at midline, the obstructed agenesis of the vagina probably is too high for a straightforward pull-through procedure. Alternatively, the patient may have a unicornuate system with agenesis of the lower vagina; in this case, the obstructed upper vaginal tissue will not be in the midline but off to one side. MRI also may be helpful for defining the pelvic anatomy.

The optimal timing for a pull-through vaginoplasty (Figure 2b) is when a large hematocolpos (Figure 2a) is present, as the blood acts as a natural expander of the native vaginal tissue, increasing the amount of tissue available for a primary reanastomosis. This emphasizes the importance of an accurate initial diagnosis. Too often, obstructions that are actually lower vaginal agenesis are presumed to be imperforate hymen, and the hematocolpos is subsequently evacuated after a transverse incision and dissection of excess tissue, causing the upper vagina to retract and shrink. This mistake can result in the formation of a fistulous tract from the previously obstructed upper vagina to the level of the introitus.

The vaginoplasty is carried out with the patient in the dorsal lithotomy position. A Foley catheter is placed into the bladder to avoid an inadvertent anterior entry into the posterior wall of the bladder, and the labia are grasped and pulled down and out.

The hymenal tissue should be visible. A transverse incision is made, with electrocautery, where the introitus should be located, and a dissection is carried out to reach the obstructed upper vaginal tissue. Care is needed to keep the dissection in the midline and avoid the bladder above and the rectum below. In cases in which it is difficult to identify the area of obstruction, intraoperative ultrasound can be helpful. A spinal needle with a 10-cc syringe also can be used to identify a track through which to access the fluid.

The linear incision then is made with electrocautery and the obstructed hemivagina is entered. Allis clamps are used to grasp the vaginal mucosa from the previously obstructed upper vagina to help identify the tissue that needs to be mobilized. The tissue then is further dissected to free the upper vagina, and the edges are pulled down to the level of the introitus with Allis clamps. “Relaxing” incisions are made at 1, 5,7, and 11 o’clock to avoid a circumferential scar. The upper vaginal mucosa is sewn to the newly created introitus with a 2-0 vicryl suture on a UR6 (a smaller curved urology needle).

When the distance from normal introitus location to obstruction is greater than 5 cm, we sometimes use vaginal dilators to lessen the distance and reach the obstruction for a pull-through procedure. Alternatively, the upper vagina may be mobilized from above either robotically or laparoscopically so that the upper vaginal mucosa may be pulled down without entering the bladder. Occasionally, with greater distances over 5 cm, the vaginoplasty may require utilization of a buccal mucosal graft or a bowel segment.

Intraoperative ultrasound can be especially helpful for locating the obstructed vagina in women with a unicornuate system because the upper vagina will not be in the midline and ultrasound can help determine the appropriate angle for dissection.

Prophylactic antibiotics initiated postoperatively are important with pull-through vaginoplasty, because the uterus and fallopian tubes may contain blood (an excellent growth media) and because there is a risk of bacteria ascending into what becomes an open system.

Postoperatively, we guide patients on the use of flexible Milex dilators (CooperSurgical) to ensure that the vagina heals without restenosis. The length of postoperative dilation therapy can vary from 2-12 months, depending on healing. The dilator is worn 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, and is removed only for urination, defecation, and cleaning. With adequate postoperative dilation, patients will have normal sexual and reproductive function, and vaginal delivery should be possible.

Obstructed hemivagina

An obstructed hemivagina, an uncommon Müllerian duct anomaly, occurs most often with ipsilateral renal agenesis and is commonly referred to as OHVIRA. Because the formation of the reproductive system is closely associated with the development of the urinary system, it is not unusual for renal anomalies to occur alongside Müllerian anomalies and vaginal anomalies. There should be a high index of suspicion for a reproductive tract anomaly in any patient known to have a horseshoe kidney, duplex collecting system, unilateral renal agenesis, or other renal anomaly.

Patients with obstructed hemivagina typically present in adolescence with pelvic pain or dysmenorrhea, and commonly are misdiagnosed as having endometriomas or vaginal cysts. On vaginal examination, the obstructed hemivagina may be visualized as a bulge coming from the lateral vaginal sidewall. While only one cervix is appreciated on a vaginal exam, an ultrasound examination often will show two uteri and two cervices. MRI also is helpful for diagnosis.

Obstructed hemivagina requires surgical correction to open the obstruction, excise the excess vaginal tissue, and create one vagina with access to the second cervix. Great care must be taken to avoid not only the bladder and rectum but the cervices. It is not unusual for the two cervices to be at different levels, with one cervix sharing medial aspects of the vaginal wall of the second vagina (Figure 1a). The tissue between the two cervices should be left in place to avoid compromising their blood supply.

We manage this anomaly primarily through a single-stage vaginoplasty. For the nonobstructed side to be visualized, a longitudinal incision into the obstructed hemivagina should be made at the point at which it is most easily palpated. As with agenesis of the lower vagina, the fluid to be drained tends to be old menstrual blood that is thick and dark brown. It is useful to set up two suction units at the time of surgery because tubing can become clogged.

The use of vaginal side wall retractors helps with visualization. Alternatively, I tend to use malleable abdominal wall retractors vaginally, as they can be bent to conform to the angle needed and come in different widths. When it is difficult to identify the area of obstruction, a spinal needle with a 10-cc syringe again can be used to identify a track for accessing the fluid. The linear incision then is made with electrocautery, and the obstructed hemivagina is entered.

Allis clamps are used to grasp the vaginal mucosa from the previously obstructed hemivagina to help identify the tissue that needs to be excised. Once the fluid is evacuated, a finger also can be placed into the obstructed vagina is help identify excess tissue. This three-dimensional elliptical area is similar to a septum but becomes the obstructed hemivagina as it attaches to the vaginal wall (Figure 1a).

Retrograde menses and endometriosis occur commonly with obstructive anomalies like obstructed hemivagina and agenesis of the lower vagina, but laparoscopy with the goal of treating endometriosis is not indicated. We discourage its use at the time of repair because there is evidence that almost all endometriosis will completely resorb on its own once the anomalies are corrected.1,2

As with repair of lower vagina agenesis, antibiotics to prevent an ascending infection should be taken after surgical correction of obstructed hemivagina. Patients with obstructed hemivagina can have a vaginal delivery if there are no other contraindications. Women with obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal anomaly have essentially two unicornuate systems and thus are at risk of breech presentation and preterm delivery.

Dr. Laufer is chief of the division of gynecology, codirector of the Center for Young Women’s Health, and director of the Boston Center for Endometriosis, all at Boston Children’s Hospital. He also is professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

References

1. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1986;154:39.

2. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2010;23(2):e89.

Congenital obstructive anomalies of the vagina are unusual and can be challenging to diagnose and manage. Two of the most challenging are obstructive hemivagina with ipsilateral renal agenesis (Figure 1a) and agenesis of the lower vagina (Figure 1b), the latter of which must be differentiated most commonly from imperforate hymen (Figure 1c). Evaluation and treatment of these anomalies is dependent upon the age of the patient, as well as the symptoms, and the timing of treatment should be individualized.

Agenesis of the lower vagina

Agenesis of the lower vagina and imperforate hymen may present either in the newborn period as a bulging introitus caused by mucocolpos from vaginal secretions stimulated by maternal estradiol or during adolescence at the time of menarche. In neonates, it often is best not to intervene when obstructive anomalies are suspected as long as there is no fever; pain; or compromise of respiration, urinary and bowel function, and other functionality. It will be easier to differentiate agenesis of the lower vagina and imperforate hymen – the latter of which is one of the most common obstructive lesions of the female genital tract – later on. And if the hymen remains imperforate, the mucus will be reabsorbed and the patient usually will remain asymptomatic until menarche.

In the adolescent time period, both anomalies often are identified when the patient presents with pelvic pain – usually cyclic pelvic pain with primary amenorrhea. Because the onset of menses typically occurs 2-3 years after the onset of estrogenization and breast development, evaluating breast development can help us to determine the timing of expected menarche. An obstructive anomaly should be suspected in an adolescent who presents with pain during this time period, after evaluation for an acute abdomen (Figure 2a).

When a vaginal orifice is visualized upon evaluation of the external genitalia and separation of the labia, a higher anomaly such as a transverse vaginal septum should be suspected. When an introitus cannot be visualized, evaluation for an imperforate hymen or agenesis of the lower vagina is necessary (Figure 1b and 1c).

The simplest way to differentiate imperforate hymen from agenesis of the lower vagina is with visualization of the obstructing tissue on exam and usage of transperitoneal ultrasound. With the transducer placed on the vulva, we can evaluate the distance from the normal location of an introitus to the level of the obstruction. If the distance is in millimeters, then typically there is an imperforate hymen. If the distance is larger – more than several millimeters – then the differential diagnosis typically is agenesis of the lower vagina, an anomaly that results from abnormal development of the sinovaginal bulbs and vaginal plate.

The distance as measured by transperitoneal ultrasound also will indicate whether or not pull-through vaginoplasty (Figure 2b) – our standard treatment for lower vaginal agenesis – is possible using native vaginal mucosa from the upper vagina. Most commonly, the distance is less than 5 cm and we are able to make a transverse incision where the hymenal ring should be located, carry the dissection to the upper vagina, drain the obstruction, and mobilize the upper vaginal mucosa, suturing it to the newly created introitus to formulate a patent vaginal tract.

A rectoabdominal examination similarly can be helpful in making the diagnosis of lower vaginal agenesis and in determining whether there is enough tissue available for a pull-through procedure (Figures 2a and 2b). Because patients with this anomaly generally have normal cyclic pituitary-ovarian-endometrial function at menarche, the upper vagina will distend with blood products and secretions that can be palpated on the rectoabdominal exam. If the obstructed vaginal tissue is not felt with the rectal finger at midline, the obstructed agenesis of the vagina probably is too high for a straightforward pull-through procedure. Alternatively, the patient may have a unicornuate system with agenesis of the lower vagina; in this case, the obstructed upper vaginal tissue will not be in the midline but off to one side. MRI also may be helpful for defining the pelvic anatomy.

The optimal timing for a pull-through vaginoplasty (Figure 2b) is when a large hematocolpos (Figure 2a) is present, as the blood acts as a natural expander of the native vaginal tissue, increasing the amount of tissue available for a primary reanastomosis. This emphasizes the importance of an accurate initial diagnosis. Too often, obstructions that are actually lower vaginal agenesis are presumed to be imperforate hymen, and the hematocolpos is subsequently evacuated after a transverse incision and dissection of excess tissue, causing the upper vagina to retract and shrink. This mistake can result in the formation of a fistulous tract from the previously obstructed upper vagina to the level of the introitus.

The vaginoplasty is carried out with the patient in the dorsal lithotomy position. A Foley catheter is placed into the bladder to avoid an inadvertent anterior entry into the posterior wall of the bladder, and the labia are grasped and pulled down and out.

The hymenal tissue should be visible. A transverse incision is made, with electrocautery, where the introitus should be located, and a dissection is carried out to reach the obstructed upper vaginal tissue. Care is needed to keep the dissection in the midline and avoid the bladder above and the rectum below. In cases in which it is difficult to identify the area of obstruction, intraoperative ultrasound can be helpful. A spinal needle with a 10-cc syringe also can be used to identify a track through which to access the fluid.

The linear incision then is made with electrocautery and the obstructed hemivagina is entered. Allis clamps are used to grasp the vaginal mucosa from the previously obstructed upper vagina to help identify the tissue that needs to be mobilized. The tissue then is further dissected to free the upper vagina, and the edges are pulled down to the level of the introitus with Allis clamps. “Relaxing” incisions are made at 1, 5,7, and 11 o’clock to avoid a circumferential scar. The upper vaginal mucosa is sewn to the newly created introitus with a 2-0 vicryl suture on a UR6 (a smaller curved urology needle).

When the distance from normal introitus location to obstruction is greater than 5 cm, we sometimes use vaginal dilators to lessen the distance and reach the obstruction for a pull-through procedure. Alternatively, the upper vagina may be mobilized from above either robotically or laparoscopically so that the upper vaginal mucosa may be pulled down without entering the bladder. Occasionally, with greater distances over 5 cm, the vaginoplasty may require utilization of a buccal mucosal graft or a bowel segment.

Intraoperative ultrasound can be especially helpful for locating the obstructed vagina in women with a unicornuate system because the upper vagina will not be in the midline and ultrasound can help determine the appropriate angle for dissection.

Prophylactic antibiotics initiated postoperatively are important with pull-through vaginoplasty, because the uterus and fallopian tubes may contain blood (an excellent growth media) and because there is a risk of bacteria ascending into what becomes an open system.

Postoperatively, we guide patients on the use of flexible Milex dilators (CooperSurgical) to ensure that the vagina heals without restenosis. The length of postoperative dilation therapy can vary from 2-12 months, depending on healing. The dilator is worn 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, and is removed only for urination, defecation, and cleaning. With adequate postoperative dilation, patients will have normal sexual and reproductive function, and vaginal delivery should be possible.

Obstructed hemivagina

An obstructed hemivagina, an uncommon Müllerian duct anomaly, occurs most often with ipsilateral renal agenesis and is commonly referred to as OHVIRA. Because the formation of the reproductive system is closely associated with the development of the urinary system, it is not unusual for renal anomalies to occur alongside Müllerian anomalies and vaginal anomalies. There should be a high index of suspicion for a reproductive tract anomaly in any patient known to have a horseshoe kidney, duplex collecting system, unilateral renal agenesis, or other renal anomaly.

Patients with obstructed hemivagina typically present in adolescence with pelvic pain or dysmenorrhea, and commonly are misdiagnosed as having endometriomas or vaginal cysts. On vaginal examination, the obstructed hemivagina may be visualized as a bulge coming from the lateral vaginal sidewall. While only one cervix is appreciated on a vaginal exam, an ultrasound examination often will show two uteri and two cervices. MRI also is helpful for diagnosis.

Obstructed hemivagina requires surgical correction to open the obstruction, excise the excess vaginal tissue, and create one vagina with access to the second cervix. Great care must be taken to avoid not only the bladder and rectum but the cervices. It is not unusual for the two cervices to be at different levels, with one cervix sharing medial aspects of the vaginal wall of the second vagina (Figure 1a). The tissue between the two cervices should be left in place to avoid compromising their blood supply.

We manage this anomaly primarily through a single-stage vaginoplasty. For the nonobstructed side to be visualized, a longitudinal incision into the obstructed hemivagina should be made at the point at which it is most easily palpated. As with agenesis of the lower vagina, the fluid to be drained tends to be old menstrual blood that is thick and dark brown. It is useful to set up two suction units at the time of surgery because tubing can become clogged.

The use of vaginal side wall retractors helps with visualization. Alternatively, I tend to use malleable abdominal wall retractors vaginally, as they can be bent to conform to the angle needed and come in different widths. When it is difficult to identify the area of obstruction, a spinal needle with a 10-cc syringe again can be used to identify a track for accessing the fluid. The linear incision then is made with electrocautery, and the obstructed hemivagina is entered.

Allis clamps are used to grasp the vaginal mucosa from the previously obstructed hemivagina to help identify the tissue that needs to be excised. Once the fluid is evacuated, a finger also can be placed into the obstructed vagina is help identify excess tissue. This three-dimensional elliptical area is similar to a septum but becomes the obstructed hemivagina as it attaches to the vaginal wall (Figure 1a).

Retrograde menses and endometriosis occur commonly with obstructive anomalies like obstructed hemivagina and agenesis of the lower vagina, but laparoscopy with the goal of treating endometriosis is not indicated. We discourage its use at the time of repair because there is evidence that almost all endometriosis will completely resorb on its own once the anomalies are corrected.1,2

As with repair of lower vagina agenesis, antibiotics to prevent an ascending infection should be taken after surgical correction of obstructed hemivagina. Patients with obstructed hemivagina can have a vaginal delivery if there are no other contraindications. Women with obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal anomaly have essentially two unicornuate systems and thus are at risk of breech presentation and preterm delivery.

Dr. Laufer is chief of the division of gynecology, codirector of the Center for Young Women’s Health, and director of the Boston Center for Endometriosis, all at Boston Children’s Hospital. He also is professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

References

1. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1986;154:39.

2. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2010;23(2):e89.