User login

Obesity: When to consider surgery

Patients with overweight and obesity are at increased risk of multiple morbidities, including cardiovascular disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes (T2D), osteoarthritis, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and all-cause mortality.1 Even modest weight loss—5% to 10%—can lead to a clinically relevant reduction in this risk of disease.2,3 The American Academy of Family Physicians recognizes obesity as a disease, and recommends screening of all adults for obesity and referral for those with body mass index (BMI)* ≥30 to intensive, multicomponent behavioral interventions.4,5

For some patients, diet, exercise, and behavioral modifications are sufficient; for the great majority, however, weight loss achieved by lifestyle modification is counteracted by metabolic adaptations that promote weight regain.6 For patients with obesity who are unable to achieve or maintain sufficient weight loss to improve health outcomes with lifestyle modification alone, options include pharmacotherapy, devices, endoscopic bariatric therapies, and bariatric surgery.

Bariatric surgery is the most effective of these treatments, due to its association with significant and sustained weight loss, reduction in obesity-related comorbidities, and improved quality of life.1,7 Furthermore, compared with usual care, bariatric surgery is associated with a reduced number of cardiovascular deaths, a lower incidence of cardiovascular events in adults with obesity, and a long-term reduction in overall mortality.8-10

What are the options? Who is a candidate?

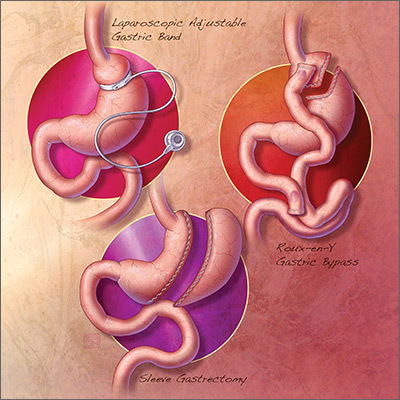

The 3 most common bariatric procedures in the United States are sleeve gastrectomy (SG), Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), and laparoscopic adjustable gastric band (LAGB).11 SG and RYGB are performed more often than the LAGB, consequent to greater efficacy and fewer complications.12 Weight loss is maximal at 1 to 2 years, and is estimated to be 15% of total body weight for LAGB; 25% for SG; and 35% for RYGB.13,14

Not all patients are candidates for bariatric surgery. Contraindications include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or respiratory dysfunction, poor cardiac reserve, nonadherence to medical treatment, and severe psychological disorders.15 Because some patients have difficulty maintaining weight loss following bariatric surgery and, on average, patients regain at least some weight, patients must understand that long-term lifestyle changes and follow-up are critical to the success of bariatric surgery.16

When should bariatric surgery be considered?

American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/The Obesity Society guidelines16 conceptualize 2 indications for bariatric surgery:

- adults with BMI ≥40

- adults with BMI ≥35 who have obesity-related comorbid conditions and are motivated to lose weight but have not responded to behavioral treatment, with or without pharmacotherapy, to achieve sufficient weight loss for target health goals.

American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists guidelines17 conceptualize 3 indications for bariatric surgery:

- adults with BMI ≥40

- adults with BMI ≥35 with 1 or more severe obesity-related complications

- adults with BMI 30-34.9 with diabetes or metabolic syndrome (evidence for this recommendation is limited).

Continue to: The 3 illustrative vignettes presented...

The 3 illustrative vignettes presented in this article offer examples of patients with obesity who could benefit from bariatric surgery. Each has been unable to achieve or maintain sufficient weight loss to improve health outcomes with nonsurgical interventions alone.

CASE 1

Sleep apnea persists despite weight loss

Robin W, a 50-year-old woman with class-II obesity (5’8”; 250 lb; BMI, 38 ), OSA requiring continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and iron-deficiency anemia secondary to menorrhagia, and taking an iron supplement, presents for weight management. She has lost 50 lb, reducing her BMI from 45.6 with behavioral modifications and pharmacotherapy, but she has been unsuccessful at achieving further weight loss despite a reduced-calorie diet and at least 30 minutes of physical activity most days.

Ms. W is frustrated that she has reached a weight plateau; she is motivated to lose more weight. Her goal is to improve her weight-related comorbid conditions and reduce her medication requirement. Despite the initial weight loss, she continues to require CPAP therapy for OSA and remains on 3 medications for hypertension. She does not have cardiac or respiratory disease, psychiatric diagnoses, or a history of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

Is bariatric surgery a reasonable option for Ms. W? If so, which procedure would you recommend?

Good option for Ms. W: Sleeve gastrectomy

It is reasonable to consider bariatric surgery—in particular, SG—for this patient with class-II obesity and multiple weight-related comorbid conditions because she has been unable to achieve further weight loss with more conservative measures.

Continue to: How does the procedure work?

How does the procedure work? SG removes a large portion of the stomach along the greater curvature, reducing the organ to approximately 15% to 25% of its original size.18 The procedure leaves the pyloric valve intact and does not involve removal or bypass of the intestines.

How appealing and successful is it? The majority of patients who undergo SG experience significant weight loss; studies report approximately 25% total body weight loss after 1 to 2 years.14 Furthermore, most patients with T2D experience resolution of, or improvement in, disease markers.19 Because SG leaves the pylorus intact, there are fewer restrictions on what a patient can eat after surgery, compared with RYGB. With further weight loss, Ms. W may experience improvement in, or resolution of, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and OSA.

The SG procedure itself is simpler than some other bariatric procedures and presents less risk of malabsorption because the intestines are left intact. Patients who undergo SG report feeling less hungry because the fundus of the stomach, which secretes ghrelin (the so-called hunger hormone), is removed.18,20

What are special considerations, including candidacy? Patients with GERD are not ideal candidates for this procedure because exacerbation of the disease is a potential associated adverse event. SG is a reasonable surgical option for Ms. W because the procedure is less likely to exacerbate her nutritional deficiency (iron-deficiency anemia), compared to RYGB, and she does not have a history of GERD.

What are the complications? Complications of SG occur at a lower rate than they do with RYGB, which is associated with a greater risk of nutritional deficiency.18 Common early complications of SG include leaking, bleeding, stenosis, GERD, and vomiting due to excessive eating. Late complications include stomach expansion by 12 months, leading to decreased restriction.15 Unlike RYGB and LAGB, SG is not reversible.

Continue to: CASE 2

CASE 2

Severe obesity, polypharmacy for type 2 diabetes

Anne P, a 42-year-old woman with class-III obesity (5’6”; 290 lb; BMI, 46.8 kg/m2), presents to discuss bariatric surgery. Comorbidities include T2D, for which she takes metformin, a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, and a sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitor; GERD; hypertension, for which she takes an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and a calcium-channel blocker; hyperlipidemia, for which she takes a statin; and osteoarthritis.

Ms. P lost 30 pounds—reducing her BMI from 51.6—when the sulfonylurea and thiazolidinedione she was taking were switched to the GLP-1 receptor agonist and the SGLT2 inhibitor. She also made behavioral modifications, including 30 minutes a day of physical activity and a reduced-calorie meal plan under the guidance of a dietitian.

However, Ms. P has been unable to lose more weight or reduce her hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level below 8%. Her goal is to avoid the need to take insulin (which several members of her family take), lower her HbA1c level, and decrease her medication requirement.

Ms. P does not have cardiac or respiratory disease or psychiatric diagnoses. Which surgical intervention would you recommend for her?

Good option for Ms. P: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

RYGB is a reasonable option for a patient with class-III obesity and multiple comorbidities, including poorly controlled T2D and GERD, who has failed conservative measures but wants to lose more weight, reduce her HbA1c, reduce her medication requirement, and avoid the need for insulin.

Continue to: How does the procedure work?

How does the procedure work? RYGB constructs a small pouch from the proximal portion of the stomach and attaches it directly to the jejunum, thus bypassing part of the stomach and duodenum. The procedure is effective for weight loss because it is both restrictive and malabsorptive: patients not only eat smaller portions, but cannot absorb all they eat. Other mechanisms attributed to RYGB that are hypothesized to promote weight loss include21:

- alteration of endogenous gut hormones, which promotes postprandial satiety

- increased levels of bile acids, which promotes alteration of the gut microbiome

- intestinal hypertrophy.

How successful is it? RYGB is associated with significant total body weight loss of approximately 35% at 2 years.9 The procedure has been shown to produce superior outcomes in reducing comorbid disease compared to other bariatric procedures or medical therapy alone. Of the procedures discussed in this article, RYGB is associated with the greatest reduction in triglycerides, HbA1c, and use of diabetes medications, including insulin.22

What are special considerations, including candidacy? For patients with mild or moderate T2D (calculated using the Individualized Metabolic Surgery Score [http://riskcalc.org/Metabolic_Surgery_Score/], which categorizes patients by number of diabetes medications, insulin use, duration of diabetes before surgery, and HbA1c), RYGB is recommended over SG because it leads to greater long-term remission of T2D.

RYGB is associated with a lower rate of GERD than SG and can even alleviate GERD in patients who have the disease. Furthermore, for patients with limited pancreatic beta cell reserve, RYBG and SG have similarly low efficacy for T2D remission; SG is therefore recommended over RYGB in this specific circumstance, given its slightly lower risk profile.23

What are the complications? Patients who undergo any bariatric surgical procedure require long-term follow-up and vitamin supplementation, but those who undergo RYGB require stricter dietary adherence after the procedure; lifelong vitamin (D, B12, folic acid, and thiamine), iron, and calcium supplementation; and long-term follow-up to reduce the risk and severity of complications and to monitor for nutritional deficiencies.7 As such, patients who have shown poor adherence to medical treatment are not good candidates for the procedure.

Continue to: Early complications include...

Early complications include leak, stricture, obstruction, and failure of the staple partition of the upper stomach. Late complications include nutritional deficiencies, as noted, and ulceration of the anastomosis. Dumping syndrome (overly rapid transit of food from the stomach into the small intestine) can develop early or late; early dumping leads to osmotic diarrhea and abdominal cramping, and late dumping leads to reactive hypoglycemia.15

Technically, RYGB is a reversible procedure, although generally it is reversed only in extreme circumstances.

CASE 3

Fatty liver disease, hesitation to undergo surgery

Walt Z, a 35 year-old-man with class-II obesity (5’10”; 265 lb; BMI, 38 kg/m2), T2D, and hepatic steatosis, presents for weight management. He has been able to lose modest weight over the years with behavioral modifications, but has been unsuccessful in maintaining that loss. He requests referral to a bariatric surgeon but is concerned about the permanence and invasiveness of most bariatric procedures.

Which surgical intervention would you recommend for this patient?

Good option for Mr. Z: Laparoscopic adjustable gastric band

Given that Mr. Z is a candidate for a surgical intervention but does not want a permanent or invasive procedure, LAGB is a reasonable option.

Continue to: How does the procedure work?

How does the procedure work? LAGB is a reversible procedure in which an inflatable band is placed around the fundus of the stomach to create a small pouch. The band can be adjusted to regulate food intake by adding or removing saline through a subcutaneous access port.

How appealing and successful is it? LAGB results in approximately 15% total body weight loss at 2 years.13 Because the procedure is purely restrictive, it carries a reduced risk of nutritional deficiency associated more commonly with malabsorptive procedures.

What are special considerations, including candidacy? As noted, Mr. Z expressed concern about the permanence and invasiveness of most bariatric procedures, and therefore wants to undergo a reversible procedure; LAGB can be a reasonable option for such a patient. Patients who want a reversible or minimally invasive procedure should also be made aware that endoscopic bariatric therapies and other devices are being developed to fill the treatment gap in the management of obesity.

What are the complications? Although LAGB is the least invasive procedure discussed here, it is associated with the highest rate of complications—most commonly, complications associated with the band itself (eg, nausea, vomiting, obstruction, band erosion or migration, esophageal dysmotility leading to acid reflux) and failure to lose weight.7 LAGB also requires more postoperative visits than other procedures, to optimize band tightness. A high number of bands are removed eventually because of complications or inadequate weight loss, or both.13,24

Shared decision-making and dialogue are essential to overcome obstacles

Despite the known benefits of bariatric surgery, including greater reduction in the risk and severity of obesity-related comorbid conditions than seen with other interventions and a long-term reduction in overall mortality when compared with usual care, fewer than 1% of eligible patients undergo a weight-loss procedure.25 Likely, this is due to:

- limited patient knowledge of the health benefits of surgery

- limited provider comfort recommending surgery

- inadequate insurance coverage, which might, in part, be due to a lack of prospective studies comparing various bariatric procedures.18

Continue to: Ultimately, the decision whether to undergo a bariatric procedure...

Ultimately, the decision whether to undergo a bariatric procedure, and which one(s) to consider, should be the product of a thorough conversation between patient and provider.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sarah R. Barenbaum, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, New York–Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical College, 530 East 70th Street, M-507, New York, NY 10021; srb9023@nyp.org

1. Must A, Spadano J, Coakley EH, et al. The disease burden associated with overweight and obesity. JAMA. 1999;282:1523-1529.

2. Wing RR, Lang W, Wadden TA, et al. Benefits of modest weight loss in improving cardiovascular risk factors in overweight and obese individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1481-1486.

3. Magkos F, Fraterrigo G, Yoshino J, et al. Effects of moderate and subsequent progressive weight loss on metabolic function and adipose tissue biology in humans with obesity. Cell Metab. 2016;23:591-601.

4. American Academy of Family Physicians. Clinical preventive service recommendation: Obesity. www.aafp.org/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/all/obesity.html. Accessed August 22, 2018.

5. American Academy of Family Physicians: USPSTF draft recommendation: Intensive behavioral interventions recommended for obesity. www.aafp.org/news/health-of-the-public/20180221uspstfobesity.html. Published February 21, 2018. Accessed August 22, 2018.

6. Saunders KH, Shukla AP, Igel LI, Aronne LJ. Obesity: When to consider medication. J Fam Pract. 2017;66:608-616.

7. Roux CW, Heneghan HM. Bariatric surgery for obesity. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102:165-182.

8. Sjöström L, Peltonen M, Jacobson P, et al. Bariatric surgery and long-term cardiovascular events. JAMA. 2012;307:56-65.

9. Sjöström L. Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial - a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Intern Med. 2013;273:219-234.

10. Reges O, Greenland P, Dicker D, et al. Association of bariatric surgery using laparoscopic banding, Roux-en-Y, gastric bypass, or laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy vs usual care obesity management with all-cause mortality. JAMA. 2018;319:279-290.

11. Lee JH, Nguyen QN, Le QA. Comparative effectiveness of 3 bariatric surgery procedures: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, laparoscopic adjustable gastric band, and sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12:997-1002.

12. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. Estimate of bariatric surgery numbers, 2011-2017. https://asmbs.org/resources/estimate-of-bariatric-surgery-numbers. Published June 2018. Accessed August 22, 2018.

13. Courcoulas AP, King WC, Belle SH, et al. Seven-year weight trajectories and health outcomes in the Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS) Study. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:427-434.

14. Heymsfield SB, Wadden TA. Mechanisms, pathophysiology, and management of obesity. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:254-266.

15. Colquitt JL, Pickett K, Loveman E, Frampton GK. Surgery for weight loss in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(8):CD003641.

16. Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; Obesity Society. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation. 2014;129:S102-S138.

17. Garvey WT, Mechanick JI, Brett EM, et al; Reviewers of the AACE/ACE Obesity Clinical Practice Guidelines. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology clinical practice guidelines for comprehensive medical care of patients with obesity. Endocr Pract. 2016;22 Suppl 3:1-203.

18. Carlin Am, Zeni Tm, English WJ, et al; Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative. The comparative effectiveness of sleeve gastrectomy, gastric bypass, and adjustable gastric banding procedures for the treatment of morbid obesity. Ann Surg. 2013;257:791-797.

19. Gill RS, Birch DW, Shi X, et al. Sleeve gastrectomy and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2010;6:707-713.

20. Karamanakos SN, Vagenas K, Kalfarentzos F, et al. Weight loss, appetite suppression, and changes in fasting and postprandial ghrelin and peptide-YY levels after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy. Ann Surg. 2008;247:401-407.

21. Abdeen G, le Roux CW. Mechanism underlying the weight loss and complications of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2016;26:410-421.

22. Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP et al; STAMPEDE Investigators. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes - 5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:641-651.

23. Aminian A, Brethauer SA, Andalib A, et al. Individualized metabolic surgery score: procedure selection based on diabetes severity. Ann Surg. 2017;266:4:650-657.

24. Smetana GW, Jones DB, Wee CC. Beyond the guidelines: Should this patient have weight loss surgery? Grand rounds discussion from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:808-817.

25. Wolfe BM, Morton JM. Weighing in on bariatric surgery: procedure use, readmission rates, and mortality [editorial]. JAMA. 2005;294:1960-1963.

Patients with overweight and obesity are at increased risk of multiple morbidities, including cardiovascular disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes (T2D), osteoarthritis, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and all-cause mortality.1 Even modest weight loss—5% to 10%—can lead to a clinically relevant reduction in this risk of disease.2,3 The American Academy of Family Physicians recognizes obesity as a disease, and recommends screening of all adults for obesity and referral for those with body mass index (BMI)* ≥30 to intensive, multicomponent behavioral interventions.4,5

For some patients, diet, exercise, and behavioral modifications are sufficient; for the great majority, however, weight loss achieved by lifestyle modification is counteracted by metabolic adaptations that promote weight regain.6 For patients with obesity who are unable to achieve or maintain sufficient weight loss to improve health outcomes with lifestyle modification alone, options include pharmacotherapy, devices, endoscopic bariatric therapies, and bariatric surgery.

Bariatric surgery is the most effective of these treatments, due to its association with significant and sustained weight loss, reduction in obesity-related comorbidities, and improved quality of life.1,7 Furthermore, compared with usual care, bariatric surgery is associated with a reduced number of cardiovascular deaths, a lower incidence of cardiovascular events in adults with obesity, and a long-term reduction in overall mortality.8-10

What are the options? Who is a candidate?

The 3 most common bariatric procedures in the United States are sleeve gastrectomy (SG), Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), and laparoscopic adjustable gastric band (LAGB).11 SG and RYGB are performed more often than the LAGB, consequent to greater efficacy and fewer complications.12 Weight loss is maximal at 1 to 2 years, and is estimated to be 15% of total body weight for LAGB; 25% for SG; and 35% for RYGB.13,14

Not all patients are candidates for bariatric surgery. Contraindications include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or respiratory dysfunction, poor cardiac reserve, nonadherence to medical treatment, and severe psychological disorders.15 Because some patients have difficulty maintaining weight loss following bariatric surgery and, on average, patients regain at least some weight, patients must understand that long-term lifestyle changes and follow-up are critical to the success of bariatric surgery.16

When should bariatric surgery be considered?

American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/The Obesity Society guidelines16 conceptualize 2 indications for bariatric surgery:

- adults with BMI ≥40

- adults with BMI ≥35 who have obesity-related comorbid conditions and are motivated to lose weight but have not responded to behavioral treatment, with or without pharmacotherapy, to achieve sufficient weight loss for target health goals.

American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists guidelines17 conceptualize 3 indications for bariatric surgery:

- adults with BMI ≥40

- adults with BMI ≥35 with 1 or more severe obesity-related complications

- adults with BMI 30-34.9 with diabetes or metabolic syndrome (evidence for this recommendation is limited).

Continue to: The 3 illustrative vignettes presented...

The 3 illustrative vignettes presented in this article offer examples of patients with obesity who could benefit from bariatric surgery. Each has been unable to achieve or maintain sufficient weight loss to improve health outcomes with nonsurgical interventions alone.

CASE 1

Sleep apnea persists despite weight loss

Robin W, a 50-year-old woman with class-II obesity (5’8”; 250 lb; BMI, 38 ), OSA requiring continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and iron-deficiency anemia secondary to menorrhagia, and taking an iron supplement, presents for weight management. She has lost 50 lb, reducing her BMI from 45.6 with behavioral modifications and pharmacotherapy, but she has been unsuccessful at achieving further weight loss despite a reduced-calorie diet and at least 30 minutes of physical activity most days.

Ms. W is frustrated that she has reached a weight plateau; she is motivated to lose more weight. Her goal is to improve her weight-related comorbid conditions and reduce her medication requirement. Despite the initial weight loss, she continues to require CPAP therapy for OSA and remains on 3 medications for hypertension. She does not have cardiac or respiratory disease, psychiatric diagnoses, or a history of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

Is bariatric surgery a reasonable option for Ms. W? If so, which procedure would you recommend?

Good option for Ms. W: Sleeve gastrectomy

It is reasonable to consider bariatric surgery—in particular, SG—for this patient with class-II obesity and multiple weight-related comorbid conditions because she has been unable to achieve further weight loss with more conservative measures.

Continue to: How does the procedure work?

How does the procedure work? SG removes a large portion of the stomach along the greater curvature, reducing the organ to approximately 15% to 25% of its original size.18 The procedure leaves the pyloric valve intact and does not involve removal or bypass of the intestines.

How appealing and successful is it? The majority of patients who undergo SG experience significant weight loss; studies report approximately 25% total body weight loss after 1 to 2 years.14 Furthermore, most patients with T2D experience resolution of, or improvement in, disease markers.19 Because SG leaves the pylorus intact, there are fewer restrictions on what a patient can eat after surgery, compared with RYGB. With further weight loss, Ms. W may experience improvement in, or resolution of, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and OSA.

The SG procedure itself is simpler than some other bariatric procedures and presents less risk of malabsorption because the intestines are left intact. Patients who undergo SG report feeling less hungry because the fundus of the stomach, which secretes ghrelin (the so-called hunger hormone), is removed.18,20

What are special considerations, including candidacy? Patients with GERD are not ideal candidates for this procedure because exacerbation of the disease is a potential associated adverse event. SG is a reasonable surgical option for Ms. W because the procedure is less likely to exacerbate her nutritional deficiency (iron-deficiency anemia), compared to RYGB, and she does not have a history of GERD.

What are the complications? Complications of SG occur at a lower rate than they do with RYGB, which is associated with a greater risk of nutritional deficiency.18 Common early complications of SG include leaking, bleeding, stenosis, GERD, and vomiting due to excessive eating. Late complications include stomach expansion by 12 months, leading to decreased restriction.15 Unlike RYGB and LAGB, SG is not reversible.

Continue to: CASE 2

CASE 2

Severe obesity, polypharmacy for type 2 diabetes

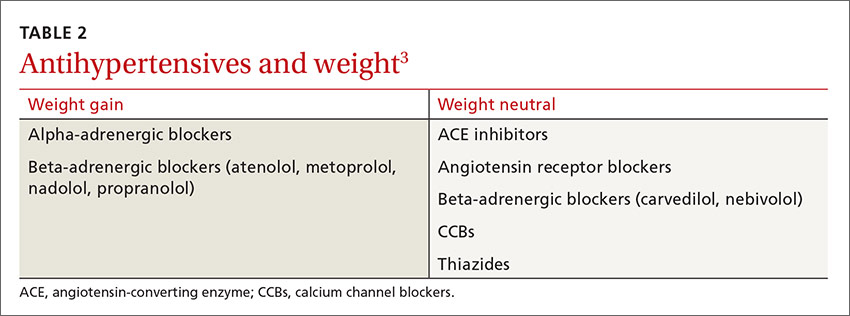

Anne P, a 42-year-old woman with class-III obesity (5’6”; 290 lb; BMI, 46.8 kg/m2), presents to discuss bariatric surgery. Comorbidities include T2D, for which she takes metformin, a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, and a sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitor; GERD; hypertension, for which she takes an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and a calcium-channel blocker; hyperlipidemia, for which she takes a statin; and osteoarthritis.

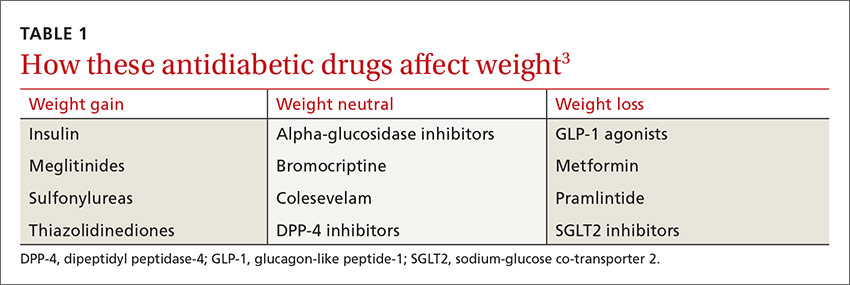

Ms. P lost 30 pounds—reducing her BMI from 51.6—when the sulfonylurea and thiazolidinedione she was taking were switched to the GLP-1 receptor agonist and the SGLT2 inhibitor. She also made behavioral modifications, including 30 minutes a day of physical activity and a reduced-calorie meal plan under the guidance of a dietitian.

However, Ms. P has been unable to lose more weight or reduce her hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level below 8%. Her goal is to avoid the need to take insulin (which several members of her family take), lower her HbA1c level, and decrease her medication requirement.

Ms. P does not have cardiac or respiratory disease or psychiatric diagnoses. Which surgical intervention would you recommend for her?

Good option for Ms. P: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

RYGB is a reasonable option for a patient with class-III obesity and multiple comorbidities, including poorly controlled T2D and GERD, who has failed conservative measures but wants to lose more weight, reduce her HbA1c, reduce her medication requirement, and avoid the need for insulin.

Continue to: How does the procedure work?

How does the procedure work? RYGB constructs a small pouch from the proximal portion of the stomach and attaches it directly to the jejunum, thus bypassing part of the stomach and duodenum. The procedure is effective for weight loss because it is both restrictive and malabsorptive: patients not only eat smaller portions, but cannot absorb all they eat. Other mechanisms attributed to RYGB that are hypothesized to promote weight loss include21:

- alteration of endogenous gut hormones, which promotes postprandial satiety

- increased levels of bile acids, which promotes alteration of the gut microbiome

- intestinal hypertrophy.

How successful is it? RYGB is associated with significant total body weight loss of approximately 35% at 2 years.9 The procedure has been shown to produce superior outcomes in reducing comorbid disease compared to other bariatric procedures or medical therapy alone. Of the procedures discussed in this article, RYGB is associated with the greatest reduction in triglycerides, HbA1c, and use of diabetes medications, including insulin.22

What are special considerations, including candidacy? For patients with mild or moderate T2D (calculated using the Individualized Metabolic Surgery Score [http://riskcalc.org/Metabolic_Surgery_Score/], which categorizes patients by number of diabetes medications, insulin use, duration of diabetes before surgery, and HbA1c), RYGB is recommended over SG because it leads to greater long-term remission of T2D.

RYGB is associated with a lower rate of GERD than SG and can even alleviate GERD in patients who have the disease. Furthermore, for patients with limited pancreatic beta cell reserve, RYBG and SG have similarly low efficacy for T2D remission; SG is therefore recommended over RYGB in this specific circumstance, given its slightly lower risk profile.23

What are the complications? Patients who undergo any bariatric surgical procedure require long-term follow-up and vitamin supplementation, but those who undergo RYGB require stricter dietary adherence after the procedure; lifelong vitamin (D, B12, folic acid, and thiamine), iron, and calcium supplementation; and long-term follow-up to reduce the risk and severity of complications and to monitor for nutritional deficiencies.7 As such, patients who have shown poor adherence to medical treatment are not good candidates for the procedure.

Continue to: Early complications include...

Early complications include leak, stricture, obstruction, and failure of the staple partition of the upper stomach. Late complications include nutritional deficiencies, as noted, and ulceration of the anastomosis. Dumping syndrome (overly rapid transit of food from the stomach into the small intestine) can develop early or late; early dumping leads to osmotic diarrhea and abdominal cramping, and late dumping leads to reactive hypoglycemia.15

Technically, RYGB is a reversible procedure, although generally it is reversed only in extreme circumstances.

CASE 3

Fatty liver disease, hesitation to undergo surgery

Walt Z, a 35 year-old-man with class-II obesity (5’10”; 265 lb; BMI, 38 kg/m2), T2D, and hepatic steatosis, presents for weight management. He has been able to lose modest weight over the years with behavioral modifications, but has been unsuccessful in maintaining that loss. He requests referral to a bariatric surgeon but is concerned about the permanence and invasiveness of most bariatric procedures.

Which surgical intervention would you recommend for this patient?

Good option for Mr. Z: Laparoscopic adjustable gastric band

Given that Mr. Z is a candidate for a surgical intervention but does not want a permanent or invasive procedure, LAGB is a reasonable option.

Continue to: How does the procedure work?

How does the procedure work? LAGB is a reversible procedure in which an inflatable band is placed around the fundus of the stomach to create a small pouch. The band can be adjusted to regulate food intake by adding or removing saline through a subcutaneous access port.

How appealing and successful is it? LAGB results in approximately 15% total body weight loss at 2 years.13 Because the procedure is purely restrictive, it carries a reduced risk of nutritional deficiency associated more commonly with malabsorptive procedures.

What are special considerations, including candidacy? As noted, Mr. Z expressed concern about the permanence and invasiveness of most bariatric procedures, and therefore wants to undergo a reversible procedure; LAGB can be a reasonable option for such a patient. Patients who want a reversible or minimally invasive procedure should also be made aware that endoscopic bariatric therapies and other devices are being developed to fill the treatment gap in the management of obesity.

What are the complications? Although LAGB is the least invasive procedure discussed here, it is associated with the highest rate of complications—most commonly, complications associated with the band itself (eg, nausea, vomiting, obstruction, band erosion or migration, esophageal dysmotility leading to acid reflux) and failure to lose weight.7 LAGB also requires more postoperative visits than other procedures, to optimize band tightness. A high number of bands are removed eventually because of complications or inadequate weight loss, or both.13,24

Shared decision-making and dialogue are essential to overcome obstacles

Despite the known benefits of bariatric surgery, including greater reduction in the risk and severity of obesity-related comorbid conditions than seen with other interventions and a long-term reduction in overall mortality when compared with usual care, fewer than 1% of eligible patients undergo a weight-loss procedure.25 Likely, this is due to:

- limited patient knowledge of the health benefits of surgery

- limited provider comfort recommending surgery

- inadequate insurance coverage, which might, in part, be due to a lack of prospective studies comparing various bariatric procedures.18

Continue to: Ultimately, the decision whether to undergo a bariatric procedure...

Ultimately, the decision whether to undergo a bariatric procedure, and which one(s) to consider, should be the product of a thorough conversation between patient and provider.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sarah R. Barenbaum, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, New York–Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical College, 530 East 70th Street, M-507, New York, NY 10021; srb9023@nyp.org

Patients with overweight and obesity are at increased risk of multiple morbidities, including cardiovascular disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes (T2D), osteoarthritis, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and all-cause mortality.1 Even modest weight loss—5% to 10%—can lead to a clinically relevant reduction in this risk of disease.2,3 The American Academy of Family Physicians recognizes obesity as a disease, and recommends screening of all adults for obesity and referral for those with body mass index (BMI)* ≥30 to intensive, multicomponent behavioral interventions.4,5

For some patients, diet, exercise, and behavioral modifications are sufficient; for the great majority, however, weight loss achieved by lifestyle modification is counteracted by metabolic adaptations that promote weight regain.6 For patients with obesity who are unable to achieve or maintain sufficient weight loss to improve health outcomes with lifestyle modification alone, options include pharmacotherapy, devices, endoscopic bariatric therapies, and bariatric surgery.

Bariatric surgery is the most effective of these treatments, due to its association with significant and sustained weight loss, reduction in obesity-related comorbidities, and improved quality of life.1,7 Furthermore, compared with usual care, bariatric surgery is associated with a reduced number of cardiovascular deaths, a lower incidence of cardiovascular events in adults with obesity, and a long-term reduction in overall mortality.8-10

What are the options? Who is a candidate?

The 3 most common bariatric procedures in the United States are sleeve gastrectomy (SG), Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), and laparoscopic adjustable gastric band (LAGB).11 SG and RYGB are performed more often than the LAGB, consequent to greater efficacy and fewer complications.12 Weight loss is maximal at 1 to 2 years, and is estimated to be 15% of total body weight for LAGB; 25% for SG; and 35% for RYGB.13,14

Not all patients are candidates for bariatric surgery. Contraindications include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or respiratory dysfunction, poor cardiac reserve, nonadherence to medical treatment, and severe psychological disorders.15 Because some patients have difficulty maintaining weight loss following bariatric surgery and, on average, patients regain at least some weight, patients must understand that long-term lifestyle changes and follow-up are critical to the success of bariatric surgery.16

When should bariatric surgery be considered?

American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/The Obesity Society guidelines16 conceptualize 2 indications for bariatric surgery:

- adults with BMI ≥40

- adults with BMI ≥35 who have obesity-related comorbid conditions and are motivated to lose weight but have not responded to behavioral treatment, with or without pharmacotherapy, to achieve sufficient weight loss for target health goals.

American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists guidelines17 conceptualize 3 indications for bariatric surgery:

- adults with BMI ≥40

- adults with BMI ≥35 with 1 or more severe obesity-related complications

- adults with BMI 30-34.9 with diabetes or metabolic syndrome (evidence for this recommendation is limited).

Continue to: The 3 illustrative vignettes presented...

The 3 illustrative vignettes presented in this article offer examples of patients with obesity who could benefit from bariatric surgery. Each has been unable to achieve or maintain sufficient weight loss to improve health outcomes with nonsurgical interventions alone.

CASE 1

Sleep apnea persists despite weight loss

Robin W, a 50-year-old woman with class-II obesity (5’8”; 250 lb; BMI, 38 ), OSA requiring continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and iron-deficiency anemia secondary to menorrhagia, and taking an iron supplement, presents for weight management. She has lost 50 lb, reducing her BMI from 45.6 with behavioral modifications and pharmacotherapy, but she has been unsuccessful at achieving further weight loss despite a reduced-calorie diet and at least 30 minutes of physical activity most days.

Ms. W is frustrated that she has reached a weight plateau; she is motivated to lose more weight. Her goal is to improve her weight-related comorbid conditions and reduce her medication requirement. Despite the initial weight loss, she continues to require CPAP therapy for OSA and remains on 3 medications for hypertension. She does not have cardiac or respiratory disease, psychiatric diagnoses, or a history of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

Is bariatric surgery a reasonable option for Ms. W? If so, which procedure would you recommend?

Good option for Ms. W: Sleeve gastrectomy

It is reasonable to consider bariatric surgery—in particular, SG—for this patient with class-II obesity and multiple weight-related comorbid conditions because she has been unable to achieve further weight loss with more conservative measures.

Continue to: How does the procedure work?

How does the procedure work? SG removes a large portion of the stomach along the greater curvature, reducing the organ to approximately 15% to 25% of its original size.18 The procedure leaves the pyloric valve intact and does not involve removal or bypass of the intestines.

How appealing and successful is it? The majority of patients who undergo SG experience significant weight loss; studies report approximately 25% total body weight loss after 1 to 2 years.14 Furthermore, most patients with T2D experience resolution of, or improvement in, disease markers.19 Because SG leaves the pylorus intact, there are fewer restrictions on what a patient can eat after surgery, compared with RYGB. With further weight loss, Ms. W may experience improvement in, or resolution of, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and OSA.

The SG procedure itself is simpler than some other bariatric procedures and presents less risk of malabsorption because the intestines are left intact. Patients who undergo SG report feeling less hungry because the fundus of the stomach, which secretes ghrelin (the so-called hunger hormone), is removed.18,20

What are special considerations, including candidacy? Patients with GERD are not ideal candidates for this procedure because exacerbation of the disease is a potential associated adverse event. SG is a reasonable surgical option for Ms. W because the procedure is less likely to exacerbate her nutritional deficiency (iron-deficiency anemia), compared to RYGB, and she does not have a history of GERD.

What are the complications? Complications of SG occur at a lower rate than they do with RYGB, which is associated with a greater risk of nutritional deficiency.18 Common early complications of SG include leaking, bleeding, stenosis, GERD, and vomiting due to excessive eating. Late complications include stomach expansion by 12 months, leading to decreased restriction.15 Unlike RYGB and LAGB, SG is not reversible.

Continue to: CASE 2

CASE 2

Severe obesity, polypharmacy for type 2 diabetes

Anne P, a 42-year-old woman with class-III obesity (5’6”; 290 lb; BMI, 46.8 kg/m2), presents to discuss bariatric surgery. Comorbidities include T2D, for which she takes metformin, a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, and a sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitor; GERD; hypertension, for which she takes an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and a calcium-channel blocker; hyperlipidemia, for which she takes a statin; and osteoarthritis.

Ms. P lost 30 pounds—reducing her BMI from 51.6—when the sulfonylurea and thiazolidinedione she was taking were switched to the GLP-1 receptor agonist and the SGLT2 inhibitor. She also made behavioral modifications, including 30 minutes a day of physical activity and a reduced-calorie meal plan under the guidance of a dietitian.

However, Ms. P has been unable to lose more weight or reduce her hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level below 8%. Her goal is to avoid the need to take insulin (which several members of her family take), lower her HbA1c level, and decrease her medication requirement.

Ms. P does not have cardiac or respiratory disease or psychiatric diagnoses. Which surgical intervention would you recommend for her?

Good option for Ms. P: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

RYGB is a reasonable option for a patient with class-III obesity and multiple comorbidities, including poorly controlled T2D and GERD, who has failed conservative measures but wants to lose more weight, reduce her HbA1c, reduce her medication requirement, and avoid the need for insulin.

Continue to: How does the procedure work?

How does the procedure work? RYGB constructs a small pouch from the proximal portion of the stomach and attaches it directly to the jejunum, thus bypassing part of the stomach and duodenum. The procedure is effective for weight loss because it is both restrictive and malabsorptive: patients not only eat smaller portions, but cannot absorb all they eat. Other mechanisms attributed to RYGB that are hypothesized to promote weight loss include21:

- alteration of endogenous gut hormones, which promotes postprandial satiety

- increased levels of bile acids, which promotes alteration of the gut microbiome

- intestinal hypertrophy.

How successful is it? RYGB is associated with significant total body weight loss of approximately 35% at 2 years.9 The procedure has been shown to produce superior outcomes in reducing comorbid disease compared to other bariatric procedures or medical therapy alone. Of the procedures discussed in this article, RYGB is associated with the greatest reduction in triglycerides, HbA1c, and use of diabetes medications, including insulin.22

What are special considerations, including candidacy? For patients with mild or moderate T2D (calculated using the Individualized Metabolic Surgery Score [http://riskcalc.org/Metabolic_Surgery_Score/], which categorizes patients by number of diabetes medications, insulin use, duration of diabetes before surgery, and HbA1c), RYGB is recommended over SG because it leads to greater long-term remission of T2D.

RYGB is associated with a lower rate of GERD than SG and can even alleviate GERD in patients who have the disease. Furthermore, for patients with limited pancreatic beta cell reserve, RYBG and SG have similarly low efficacy for T2D remission; SG is therefore recommended over RYGB in this specific circumstance, given its slightly lower risk profile.23

What are the complications? Patients who undergo any bariatric surgical procedure require long-term follow-up and vitamin supplementation, but those who undergo RYGB require stricter dietary adherence after the procedure; lifelong vitamin (D, B12, folic acid, and thiamine), iron, and calcium supplementation; and long-term follow-up to reduce the risk and severity of complications and to monitor for nutritional deficiencies.7 As such, patients who have shown poor adherence to medical treatment are not good candidates for the procedure.

Continue to: Early complications include...

Early complications include leak, stricture, obstruction, and failure of the staple partition of the upper stomach. Late complications include nutritional deficiencies, as noted, and ulceration of the anastomosis. Dumping syndrome (overly rapid transit of food from the stomach into the small intestine) can develop early or late; early dumping leads to osmotic diarrhea and abdominal cramping, and late dumping leads to reactive hypoglycemia.15

Technically, RYGB is a reversible procedure, although generally it is reversed only in extreme circumstances.

CASE 3

Fatty liver disease, hesitation to undergo surgery

Walt Z, a 35 year-old-man with class-II obesity (5’10”; 265 lb; BMI, 38 kg/m2), T2D, and hepatic steatosis, presents for weight management. He has been able to lose modest weight over the years with behavioral modifications, but has been unsuccessful in maintaining that loss. He requests referral to a bariatric surgeon but is concerned about the permanence and invasiveness of most bariatric procedures.

Which surgical intervention would you recommend for this patient?

Good option for Mr. Z: Laparoscopic adjustable gastric band

Given that Mr. Z is a candidate for a surgical intervention but does not want a permanent or invasive procedure, LAGB is a reasonable option.

Continue to: How does the procedure work?

How does the procedure work? LAGB is a reversible procedure in which an inflatable band is placed around the fundus of the stomach to create a small pouch. The band can be adjusted to regulate food intake by adding or removing saline through a subcutaneous access port.

How appealing and successful is it? LAGB results in approximately 15% total body weight loss at 2 years.13 Because the procedure is purely restrictive, it carries a reduced risk of nutritional deficiency associated more commonly with malabsorptive procedures.

What are special considerations, including candidacy? As noted, Mr. Z expressed concern about the permanence and invasiveness of most bariatric procedures, and therefore wants to undergo a reversible procedure; LAGB can be a reasonable option for such a patient. Patients who want a reversible or minimally invasive procedure should also be made aware that endoscopic bariatric therapies and other devices are being developed to fill the treatment gap in the management of obesity.

What are the complications? Although LAGB is the least invasive procedure discussed here, it is associated with the highest rate of complications—most commonly, complications associated with the band itself (eg, nausea, vomiting, obstruction, band erosion or migration, esophageal dysmotility leading to acid reflux) and failure to lose weight.7 LAGB also requires more postoperative visits than other procedures, to optimize band tightness. A high number of bands are removed eventually because of complications or inadequate weight loss, or both.13,24

Shared decision-making and dialogue are essential to overcome obstacles

Despite the known benefits of bariatric surgery, including greater reduction in the risk and severity of obesity-related comorbid conditions than seen with other interventions and a long-term reduction in overall mortality when compared with usual care, fewer than 1% of eligible patients undergo a weight-loss procedure.25 Likely, this is due to:

- limited patient knowledge of the health benefits of surgery

- limited provider comfort recommending surgery

- inadequate insurance coverage, which might, in part, be due to a lack of prospective studies comparing various bariatric procedures.18

Continue to: Ultimately, the decision whether to undergo a bariatric procedure...

Ultimately, the decision whether to undergo a bariatric procedure, and which one(s) to consider, should be the product of a thorough conversation between patient and provider.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sarah R. Barenbaum, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, New York–Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical College, 530 East 70th Street, M-507, New York, NY 10021; srb9023@nyp.org

1. Must A, Spadano J, Coakley EH, et al. The disease burden associated with overweight and obesity. JAMA. 1999;282:1523-1529.

2. Wing RR, Lang W, Wadden TA, et al. Benefits of modest weight loss in improving cardiovascular risk factors in overweight and obese individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1481-1486.

3. Magkos F, Fraterrigo G, Yoshino J, et al. Effects of moderate and subsequent progressive weight loss on metabolic function and adipose tissue biology in humans with obesity. Cell Metab. 2016;23:591-601.

4. American Academy of Family Physicians. Clinical preventive service recommendation: Obesity. www.aafp.org/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/all/obesity.html. Accessed August 22, 2018.

5. American Academy of Family Physicians: USPSTF draft recommendation: Intensive behavioral interventions recommended for obesity. www.aafp.org/news/health-of-the-public/20180221uspstfobesity.html. Published February 21, 2018. Accessed August 22, 2018.

6. Saunders KH, Shukla AP, Igel LI, Aronne LJ. Obesity: When to consider medication. J Fam Pract. 2017;66:608-616.

7. Roux CW, Heneghan HM. Bariatric surgery for obesity. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102:165-182.

8. Sjöström L, Peltonen M, Jacobson P, et al. Bariatric surgery and long-term cardiovascular events. JAMA. 2012;307:56-65.

9. Sjöström L. Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial - a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Intern Med. 2013;273:219-234.

10. Reges O, Greenland P, Dicker D, et al. Association of bariatric surgery using laparoscopic banding, Roux-en-Y, gastric bypass, or laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy vs usual care obesity management with all-cause mortality. JAMA. 2018;319:279-290.

11. Lee JH, Nguyen QN, Le QA. Comparative effectiveness of 3 bariatric surgery procedures: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, laparoscopic adjustable gastric band, and sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12:997-1002.

12. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. Estimate of bariatric surgery numbers, 2011-2017. https://asmbs.org/resources/estimate-of-bariatric-surgery-numbers. Published June 2018. Accessed August 22, 2018.

13. Courcoulas AP, King WC, Belle SH, et al. Seven-year weight trajectories and health outcomes in the Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS) Study. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:427-434.

14. Heymsfield SB, Wadden TA. Mechanisms, pathophysiology, and management of obesity. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:254-266.

15. Colquitt JL, Pickett K, Loveman E, Frampton GK. Surgery for weight loss in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(8):CD003641.

16. Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; Obesity Society. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation. 2014;129:S102-S138.

17. Garvey WT, Mechanick JI, Brett EM, et al; Reviewers of the AACE/ACE Obesity Clinical Practice Guidelines. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology clinical practice guidelines for comprehensive medical care of patients with obesity. Endocr Pract. 2016;22 Suppl 3:1-203.

18. Carlin Am, Zeni Tm, English WJ, et al; Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative. The comparative effectiveness of sleeve gastrectomy, gastric bypass, and adjustable gastric banding procedures for the treatment of morbid obesity. Ann Surg. 2013;257:791-797.

19. Gill RS, Birch DW, Shi X, et al. Sleeve gastrectomy and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2010;6:707-713.

20. Karamanakos SN, Vagenas K, Kalfarentzos F, et al. Weight loss, appetite suppression, and changes in fasting and postprandial ghrelin and peptide-YY levels after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy. Ann Surg. 2008;247:401-407.

21. Abdeen G, le Roux CW. Mechanism underlying the weight loss and complications of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2016;26:410-421.

22. Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP et al; STAMPEDE Investigators. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes - 5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:641-651.

23. Aminian A, Brethauer SA, Andalib A, et al. Individualized metabolic surgery score: procedure selection based on diabetes severity. Ann Surg. 2017;266:4:650-657.

24. Smetana GW, Jones DB, Wee CC. Beyond the guidelines: Should this patient have weight loss surgery? Grand rounds discussion from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:808-817.

25. Wolfe BM, Morton JM. Weighing in on bariatric surgery: procedure use, readmission rates, and mortality [editorial]. JAMA. 2005;294:1960-1963.

1. Must A, Spadano J, Coakley EH, et al. The disease burden associated with overweight and obesity. JAMA. 1999;282:1523-1529.

2. Wing RR, Lang W, Wadden TA, et al. Benefits of modest weight loss in improving cardiovascular risk factors in overweight and obese individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1481-1486.

3. Magkos F, Fraterrigo G, Yoshino J, et al. Effects of moderate and subsequent progressive weight loss on metabolic function and adipose tissue biology in humans with obesity. Cell Metab. 2016;23:591-601.

4. American Academy of Family Physicians. Clinical preventive service recommendation: Obesity. www.aafp.org/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/all/obesity.html. Accessed August 22, 2018.

5. American Academy of Family Physicians: USPSTF draft recommendation: Intensive behavioral interventions recommended for obesity. www.aafp.org/news/health-of-the-public/20180221uspstfobesity.html. Published February 21, 2018. Accessed August 22, 2018.

6. Saunders KH, Shukla AP, Igel LI, Aronne LJ. Obesity: When to consider medication. J Fam Pract. 2017;66:608-616.

7. Roux CW, Heneghan HM. Bariatric surgery for obesity. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102:165-182.

8. Sjöström L, Peltonen M, Jacobson P, et al. Bariatric surgery and long-term cardiovascular events. JAMA. 2012;307:56-65.

9. Sjöström L. Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial - a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Intern Med. 2013;273:219-234.

10. Reges O, Greenland P, Dicker D, et al. Association of bariatric surgery using laparoscopic banding, Roux-en-Y, gastric bypass, or laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy vs usual care obesity management with all-cause mortality. JAMA. 2018;319:279-290.

11. Lee JH, Nguyen QN, Le QA. Comparative effectiveness of 3 bariatric surgery procedures: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, laparoscopic adjustable gastric band, and sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12:997-1002.

12. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. Estimate of bariatric surgery numbers, 2011-2017. https://asmbs.org/resources/estimate-of-bariatric-surgery-numbers. Published June 2018. Accessed August 22, 2018.

13. Courcoulas AP, King WC, Belle SH, et al. Seven-year weight trajectories and health outcomes in the Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS) Study. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:427-434.

14. Heymsfield SB, Wadden TA. Mechanisms, pathophysiology, and management of obesity. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:254-266.

15. Colquitt JL, Pickett K, Loveman E, Frampton GK. Surgery for weight loss in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(8):CD003641.

16. Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; Obesity Society. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation. 2014;129:S102-S138.

17. Garvey WT, Mechanick JI, Brett EM, et al; Reviewers of the AACE/ACE Obesity Clinical Practice Guidelines. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology clinical practice guidelines for comprehensive medical care of patients with obesity. Endocr Pract. 2016;22 Suppl 3:1-203.

18. Carlin Am, Zeni Tm, English WJ, et al; Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative. The comparative effectiveness of sleeve gastrectomy, gastric bypass, and adjustable gastric banding procedures for the treatment of morbid obesity. Ann Surg. 2013;257:791-797.

19. Gill RS, Birch DW, Shi X, et al. Sleeve gastrectomy and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2010;6:707-713.

20. Karamanakos SN, Vagenas K, Kalfarentzos F, et al. Weight loss, appetite suppression, and changes in fasting and postprandial ghrelin and peptide-YY levels after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy. Ann Surg. 2008;247:401-407.

21. Abdeen G, le Roux CW. Mechanism underlying the weight loss and complications of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2016;26:410-421.

22. Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP et al; STAMPEDE Investigators. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes - 5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:641-651.

23. Aminian A, Brethauer SA, Andalib A, et al. Individualized metabolic surgery score: procedure selection based on diabetes severity. Ann Surg. 2017;266:4:650-657.

24. Smetana GW, Jones DB, Wee CC. Beyond the guidelines: Should this patient have weight loss surgery? Grand rounds discussion from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:808-817.

25. Wolfe BM, Morton JM. Weighing in on bariatric surgery: procedure use, readmission rates, and mortality [editorial]. JAMA. 2005;294:1960-1963.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

Among adult patients with body mass index* ≥40, or ≥35 with obesity-related comorbid conditions:

› Consider bariatric surgery in those who are motivated to lose weight but who have not responded to lifestyle modification with or without pharmacotherapy in order to achieve sufficient and sustained weight loss. A

› Consider bariatric surgery to help patients achieve target health goals and reduce/improve obesity-related comorbidities. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

*Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Obesity: When to consider medication

Modest weight loss of 5% to 10% among patients who are overweight or obese can result in a clinically relevant reduction in cardiovascular (CV) disease risk.1 This amount of weight loss can increase insulin sensitivity in adipose tissue, liver, and muscle, and have a positive impact on blood sugar, blood pressure, triglycerides, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.1,2

All patients who are obese or overweight with increased CV risk should be counseled on diet, exercise, and other behavioral interventions.3 Weight loss secondary to lifestyle modification alone, however, leads to adaptive physiologic responses, which increase appetite and reduce energy expenditure.4-6

Pharmacotherapy can counteract this metabolic adaptation and lead to sustained weight loss. Antiobesity medication can be considered if a patient has a body mass index (BMI) ≥30 kg/m2 or ≥27 kg/m2 with obesity-related comorbidities such as hypertension, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, or obstructive sleep apnea.3,7

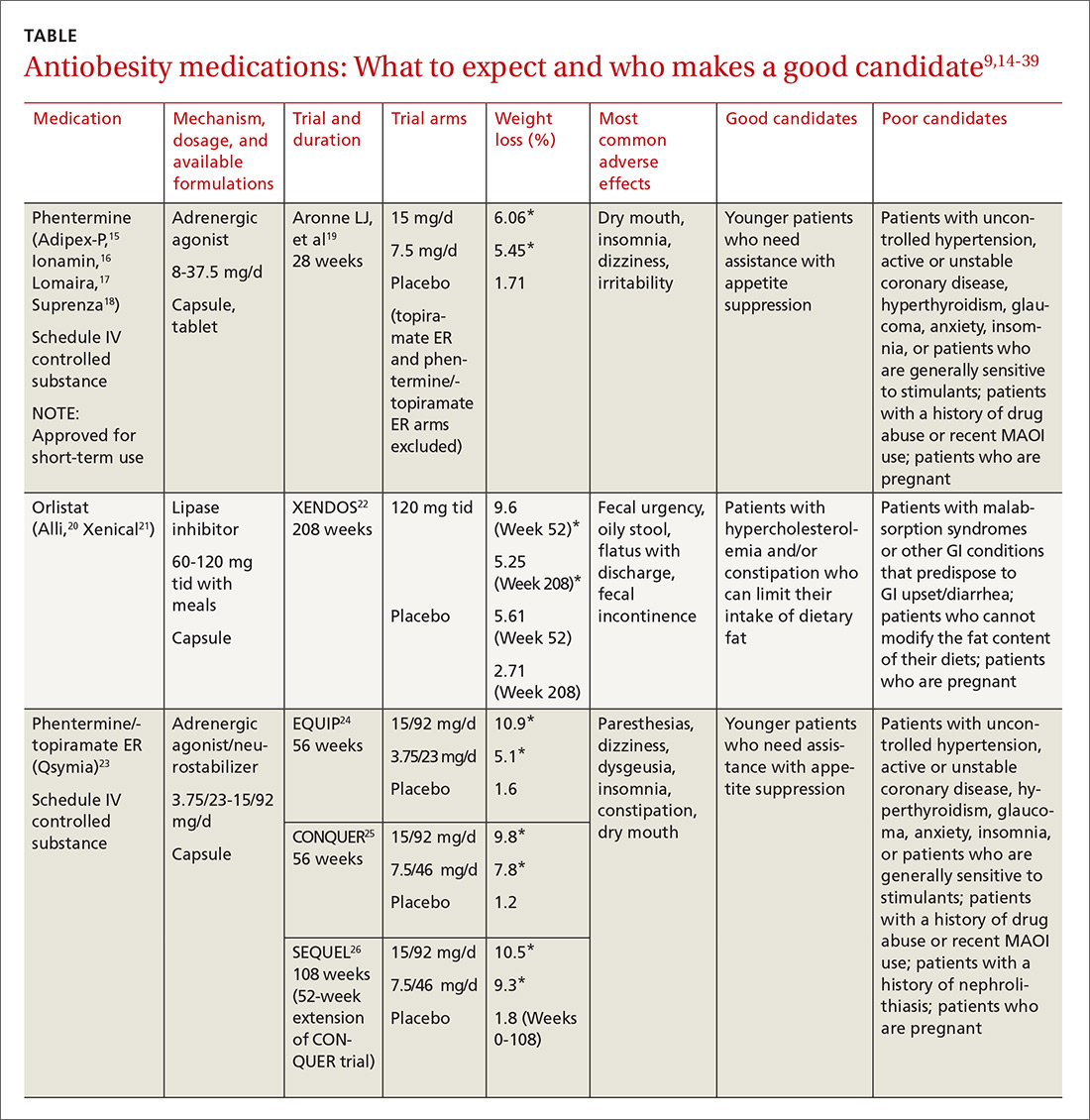

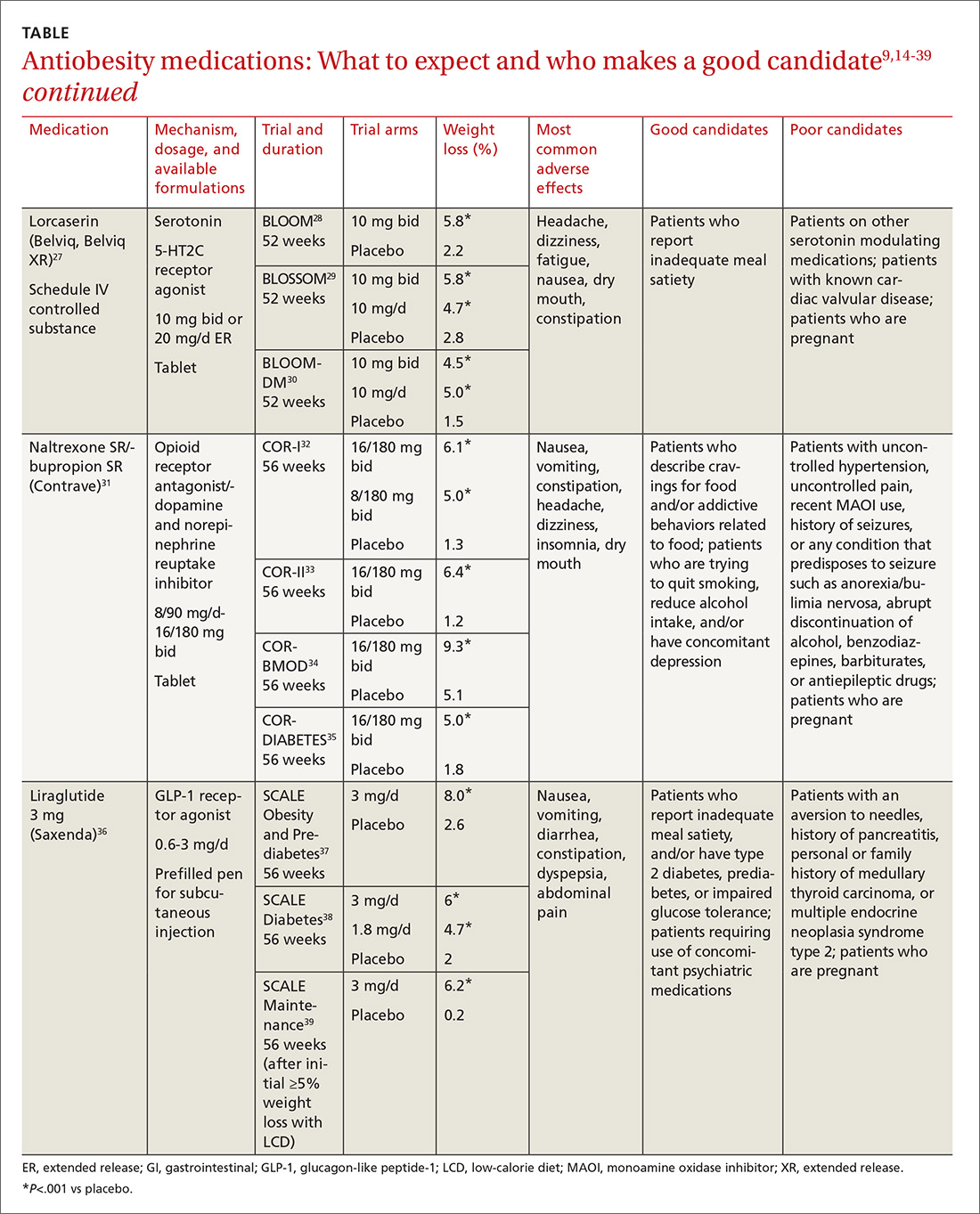

Until recently, there were few pharmacologic options approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the management of obesity. The mainstays of treatment were phentermine (Adipex-P, Ionamin, Suprenza) and orlistat (Alli, Xenical). Since 2012, however, 4 agents have been approved as adjuncts to a reduced-calorie diet and increased physical activity for long-term weight management.8,9 Phentermine/topiramate extended-release (ER) (Qsymia) and lorcaserin (Belviq) were approved in 2012,10,11 and naltrexone sustained release (SR)/bupropion SR (Contrave) and liraglutide 3 mg (Saxenda) were approved in 201412,13 (TABLE9,14-39). These medications have the potential to not only limit weight gain, but also promote weight loss and, thus, improve blood pressure, cholesterol, glucose, and insulin.40

Despite the growing obesity epidemic and the availability of several additional medications for chronic weight management, use of antiobesity pharmacotherapy has been limited. Barriers to use include inadequate training of health care professionals, poor insurance coverage for new agents, and low reimbursement for office visits to address weight.41

In addition, the number of obesity medicine specialists, while increasing, is still not sufficient. Therefore, it is imperative for other health care professionals—namely family practitioners—to be aware of the treatment options available to patients who are overweight or obese and to be adept at using them.

In this review, we present 4 cases that depict patients who could benefit from the addition of antiobesity pharmacotherapy to a comprehensive treatment plan that includes diet, physical activity, and behavioral modification.

[polldaddy:9840472]

CASE 1 Melissa C, a 27-year-old woman with obesity (BMI 33 kg/m2), hyperlipidemia, and migraine headaches, presents for weight management. Despite a calorie-reduced diet and 200 minutes per week of exercise for the past 6 months, she has been unable to lose weight. The only medications she’s taking are oral contraceptive pills and sumatriptan, as needed. She suffers from migraines 3 times a month and has no anxiety. Laboratory test results are normal with the exception of an elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) level.

Which medication is an appropriate next step for Ms. C?

Discussion

When considering an antiobesity agent for any patient, there are 2 important questions to ask:

- Are there contraindications, drug-drug interactions, or undesirable adverse effects associated with this medication that could be problematic for the patient?

- Can this medication improve other symptoms or conditions the patient has?

In addition, see “Before prescribing antiobesity medication . . .”

SIDEBAR

Before prescribing antiobesity medication . . .Have a frank discussion with the patient and be sure to cover the following points:

- The rationale for pharmacologic treatment is to counteract adaptive physiologic responses, which increase appetite and reduce energy expenditure, in response to diet-induced weight loss.

- Antiobesity medication is only one component of a comprehensive treatment plan, which also includes diet, physical activity, and behavior modification.

- Antiobesity agents are intended for long-term use, as obesity is a chronic disease. If/when you stop the medication, there may be some weight regain, similar to an increase in blood pressure after discontinuing an antihypertensive agent.

- Because antiobesity medications improve many parameters including glucose/hemoglobin A1c, lipids, blood pressure, and waist circumference, it is possible that the addition of one antiobesity medication can reduce, or even eliminate, the need for several other medications.

Remember that many patients who present for obesity management have experienced weight bias. It is important to not be judgmental, but rather explain why obesity is a chronic disease. If patients understand the physiology of their condition, they will understand that their limited success with weight loss in the past is not just a matter of willpower. Lifestyle change and weight loss are extremely difficult, so it is important to provide encouragement and support for ongoing behavioral modification.

Phentermine/topiramate ER is a good first choice for this young patient with class I (BMI 30-34.9 kg/m2) obesity and migraines, as she can likely tolerate a stimulant and her migraines might improve with topiramate. Before starting the medication, ask about insomnia and nephrolithiasis in addition to anxiety and other contraindications (ie, glaucoma, hyperthyroidism, recent monoamine oxidase inhibitor use, or a known hypersensitivity or idiosyncrasy to sympathomimetic amines).23 The most common adverse events reported in phase III trials were dry mouth, paresthesia, and constipation.24-26

Not for pregnant women. Women of childbearing age must have a negative pregnancy test before starting phentermine/topiramate ER and every month while taking the medication. The FDA requires a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) to inform prescribers and patients about the increased risk of congenital malformation, specifically orofacial clefts, in infants exposed to topiramate during the first trimester of pregnancy.42 REMS focuses on the importance of pregnancy prevention, the consistent use of birth control, and the need to discontinue phentermine/topiramate ER immediately if pregnancy occurs.

Flexible dosing. Phentermine/topiramate ER is available in 4 dosages: phentermine 3.75 mg/topiramate 23 mg ER; phentermine 7.5 mg/topiramate 46 mg ER; phentermine 11.25 mg/topiramate 69 mg ER; and phentermine 15 mg/topiramate 92 mg ER. Gradual dose escalation minimizes risks and adverse events.23

Monitor patients frequently to evaluate for adverse effects and ensure adherence to diet, exercise, and lifestyle modifications. If weight loss is slower or less robust than expected, check for dietary indiscretion, as medications have limited efficacy without appropriate behavioral changes.

Discontinue phentermine/topiramate ER if the patient does not achieve 5% weight loss after 12 weeks on the maximum dose, as it is unlikely that she will achieve and sustain clinically meaningful weight loss with continued treatment.23 In this case, consider another agent with a different mechanism of action. Any of the other antiobesity medications could be appropriate for this patient.

CASE 2 Norman S, a 52-year-old overweight man (BMI 29 kg/m2) with type 2 diabetes, hyperlipidemia, osteoarthritis, and glaucoma, has recently hit a plateau with his weight loss. He lost 45 pounds secondary to diet and exercise, but hasn’t been able to lose any more. He also struggles with constant hunger. His medications include metformin 1000 mg bid, atorvastatin 10 mg/d, and occasional acetaminophen/oxycodone for knee pain until he undergoes a left knee replacement. Laboratory values are normal except for a hemoglobin A1c of 7.2%.

Mr. S is afraid of needles and cannot tolerate stimulants due to anxiety. Which medication is an appropriate next step for this patient?

Discussion

Lorcaserin is a good choice for this patient who is overweight and has several weight-related comorbidities. He has worked hard to lose a significant number of pounds, and is now at high risk of regaining them. That’s because his appetite has increased with his new exercise regimen, but his energy expenditure has decreased secondary to metabolic adaptation.

Narrowing the field. Naltrexone SR/bupropion SR cannot be used because of his opioid use. Phentermine/topiramate ER is contraindicated for patients with glaucoma, and liraglutide 3 mg is not appropriate given the patient’s fear of needles.

He could try orlistat, especially if he struggles with constipation, but the gastrointestinal adverse effects are difficult for many patients to tolerate. While not an antiobesity medication, a sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor could be prescribed for his diabetes and may also promote weight loss.43

An appealing choice. The glucose-lowering effect of lorcaserin could provide an added benefit for the patient. The BLOOM-DM (Behavioral modification and lorcaserin for overweight and obesity management in diabetes mellitus) study reported a mean reduction in hemoglobin A1c of 0.9% in the treatment group compared with a 0.4% reduction in the placebo group,30 and the effect of lorcaserin on A1c appeared to be independent of weight loss.

Mechanism of action: Cause for concern? Although lorcaserin selectively binds to serotonin 5-HT2C receptors, the theoretical risk of cardiac valvulopathy was evaluated in phase III studies, as fenfluramine, a 5-HT2B-receptor agonist, was withdrawn from the US market in 1997 for this reason.44 Both the BLOOM (Behavioral modification and lorcaserin for overweight and obesity management) and BLOSSOM (Behavioral modification and lorcaserin second study for obesity management) studies found that lorcaserin did not increase the incidence of FDA-defined cardiac valvulopathy.28,29

Formulations/adverse effects. Lorcaserin is available in 2 formulations: 10-mg tablets, which are taken twice daily, or 20-mg XR tablets, which are taken once daily. Both are generally well tolerated.27,45 The most common adverse event reported in phase III trials was headache.28,30,43 Discontinue lorcaserin if the patient does not lose 5% of his initial weight after 12 weeks, as weight loss at this stage is a good predictor of longer-term success.46

Some patients don’t respond. Interestingly, a subset of patients do not respond to lorcaserin. The most likely explanation for different responses to the medication is that there are many causes of obesity, only some of which respond to 5-HT2C agonism. Currently, we do not perform pharmacogenomic testing before prescribing lorcaserin, but perhaps an inexpensive test to identify responders will be available in the future.

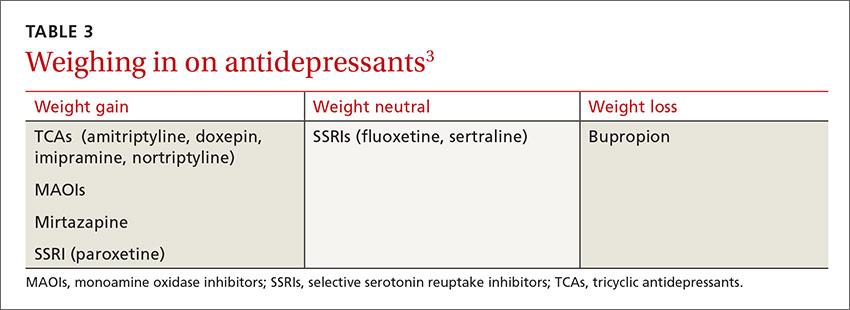

CASE 3 Kathryn M, a 38-year-old woman with obesity (BMI 42 kg/m2), obstructive sleep apnea, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and depression, is eager to get better control over her weight. Her medications include lansoprazole 30 mg/d and a multivitamin. She reports constantly thinking about food and not being able to control her impulses to buy large quantities of unhealthy snacks. She is so preoccupied by thoughts of food that she has difficulty concentrating at work.

Ms. M smokes a quarter of a pack of cigarettes daily, but she is ready to quit. She views bariatric surgery as a “last resort” and has no anxiety, pain, or history of seizures. Which medication is appropriate for this patient?

Discussion

This patient with class III obesity (BMI ≥40 kg/m2) is eligible for bariatric surgery; however, she is not interested in pursuing it at this time. It is important to discuss all of her options before deciding on a treatment plan. For patients like Ms. M, who would benefit from more than modest weight loss, consider a multidisciplinary approach including lifestyle modifications, pharmacotherapy, devices (eg, an intragastric balloon), and/or surgery. You would need to make clear to Ms. M that she may still be eligible for insurance coverage for surgery if she changes her mind after pursuing other treatments as long as her BMI remains ≥35 kg/m2 with obesity-related comorbidities.

Naltrexone SR/bupropion SR is a good choice for Ms. M because she describes debilitating cravings and addictive behavior surrounding food. Patients taking naltrexone SR/bupropion SR in the Contrave Obesity Research (COR)-I and COR-II phase III trials experienced a reduced frequency of food cravings, reduced difficulty in resisting food cravings, and an increased ability to control eating compared with those assigned to placebo.32,33

Added benefits. Bupropion could also help Ms. M quit smoking and improve her mood, as it is FDA-approved for smoking cessation and depression. She denies anxiety and seizures, so bupropion is not contraindicated. Even if a patient denies a history of seizure, ask about any conditions that predispose to seizures, such as anorexia nervosa or bulimia or the abrupt discontinuation of alcohol, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, or antiepileptic drugs.

Opioid use. Although the patient denies pain, ask about potential opioid use, as naltrexone is an opioid receptor antagonist. Patients should be informed that opioids may be ineffective if they are required unexpectedly (eg, for trauma) and that naltrexone SR/bupropion SR should be withheld for any planned surgical procedure potentially requiring opioid use.

Other options. While naltrexone SR/bupropion SR is the most appropriate choice for this patient because it addresses Ms. M’s problematic eating behaviors while potentially improving mood and assisting with smoking cessation, phentermine/topiramate ER, lorcaserin, and liraglutide 3 mg could also be used and should certainly be tried if naltrexone SR/bupropion SR does not produce the desired weight loss.

Adverse effects. Titrate naltrexone SR/bupropion SR slowly to the treatment dose to minimize risks and adverse events.31 The most common adverse effects reported in phase III trials were nausea, constipation, and headache.34,35,45,46 Discontinue naltrexone SR/bupropion SR if the patient does not achieve 5% weight loss at 16 weeks (after 12 weeks at the maintenance dose).31

CASE 4 William P, a 65-year-old man with obesity (BMI 39 kg/m2) who underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery and who has type 2 diabetes, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia, remains concerned about his weight. He lost 100 lbs following surgery and maintained his weight for 3 years, but then regained 30 lbs. He comes in for an office visit because he’s concerned about his increasing blood sugar and wants to prevent further weight gain. His medications include metformin 1000 mg bid, lisinopril 5 mg/d, carvedilol 12.5 mg bid, simvastatin 20 mg/d, and aspirin 81 mg/d. Laboratory test results are normal except for a hemoglobin A1c of 8%. He denies pancreatitis and a personal or family history of thyroid cancer.

Which medication is an appropriate next step for Mr. P?

Discussion

Pharmacotherapy is a great option for this patient, who is regaining weight following bariatric surgery. Phentermine/topiramate ER is the only medication that would be contraindicated because of his heart disease. Lorcaserin and naltrexone SR/bupropion SR could be considered, but liraglutide 3 mg is the most appropriate option, given his need for further glucose control.

Furthermore, the recent LEADER (Liraglutide effect and action in diabetes: evaluation of CV outcome results) trial reported a significant mortality benefit with liraglutide 1.8 mg/d among patients with type 2 diabetes and high CV risk.47 The study found that liraglutide was superior to placebo in reducing CV events.

Contraindications. Ask patients about a history of pancreatitis before starting liraglutide 3 mg given the possible increased risk. In addition, liraglutide is contraindicated in patients with a personal or family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma or in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2. Thyroid C-cell tumors have been found in rodents given supratherapeutic doses of liraglutide;48 however, there is no evidence of liraglutide causing C-cell tumors in humans.

For patients taking a medication that can cause hypoglycemia, such as insulin or a sulfonylurea, monitor blood sugar and consider reducing the dose of that medication when starting liraglutide.

Administration and titration. Liraglutide is injected subcutaneously once daily. The dose is titrated up weekly to reduce gastrointestinal symptoms.36 The most common adverse effects reported in phase III trials were nausea, diarrhea, and constipation.37-39 Discontinue liraglutide 3 mg if the patient does not lose at least 4% of baseline body weight after 16 weeks.49

CORRESPONDENCE

Katherine H. Saunders, MD, DABOM, Comprehensive Weight Control Center, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism, Weill Cornell Medicine, 1165 York Avenue, New York, NY 10065; kph2001@med.cornell.edu.

1. Wing RR, Lang W, Wadden TA, et al. Benefits of modest weight loss in improving cardiovascular risk factors in overweight and obese individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1481-1486.

2. Magkos F, Fraterrigo G, Yoshino J. Effects of moderate and subsequent progressive weight loss on metabolic function and adipose tissue biology in humans with obesity. Cell Metab. 2016;23:591-601.