User login

Iron Overload in Non-HFE Liver Disease: Not all Iron is Ready to Strike

Pathological iron overload with end-organ damage in hemochromatosis occurs in individuals who are homozygous for the major mutation C282Y. Phenotypic hemochromatosis occurs much less frequently in compound heterozygotes with one C282Y mutation and one H63D mutation. Iron overload can be confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging, which shows a loss of signal intensity in affected tissues and avoids the need for liver biopsy.

The serum ferritin level, an acute phase reactant, may be elevated for reasons other than iron overload, including infection and malignancy; in such cases, the iron saturation is usually normal. In patients with liver disease, iron overload is not restricted to patients with genetic hemochromatosis. In nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), up to one-third of patients have an elevated iron saturation (> 45%) and an elevated serum ferritin level. Iron accumulation in NAFLD can occur in hepatocytes, the reticuloendothelial system, or both. Deposition of iron in the reticuloendothelial system has been implicated in more severe liver disease (steatohepatitis and fibrosis) in NAFLD. Hepatic iron accumulation is also frequent in alcohol-associated liver disease. In chronic hepatitis B and C, accumulation of hepatic iron is also recognized.

Dr. Martin is chief of the division of digestive health and liver diseases at the Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami, where he is the Mandel Chair of Gastroenterology. Dr. Friedman is the Anton R. Fried, MD, Chair of the department of medicine at Newton-Wellesley Hospital in Newton, Massachusetts, and assistant chief of medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and Tufts University School of Medicine, all in Boston. The authors disclosed no conflicts. Previously published in Gastro Hep Advances. 2023 Oct 12. doi: 10.1016/j.gastha.2023.10.004.

Pathological iron overload with end-organ damage in hemochromatosis occurs in individuals who are homozygous for the major mutation C282Y. Phenotypic hemochromatosis occurs much less frequently in compound heterozygotes with one C282Y mutation and one H63D mutation. Iron overload can be confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging, which shows a loss of signal intensity in affected tissues and avoids the need for liver biopsy.

The serum ferritin level, an acute phase reactant, may be elevated for reasons other than iron overload, including infection and malignancy; in such cases, the iron saturation is usually normal. In patients with liver disease, iron overload is not restricted to patients with genetic hemochromatosis. In nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), up to one-third of patients have an elevated iron saturation (> 45%) and an elevated serum ferritin level. Iron accumulation in NAFLD can occur in hepatocytes, the reticuloendothelial system, or both. Deposition of iron in the reticuloendothelial system has been implicated in more severe liver disease (steatohepatitis and fibrosis) in NAFLD. Hepatic iron accumulation is also frequent in alcohol-associated liver disease. In chronic hepatitis B and C, accumulation of hepatic iron is also recognized.

Dr. Martin is chief of the division of digestive health and liver diseases at the Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami, where he is the Mandel Chair of Gastroenterology. Dr. Friedman is the Anton R. Fried, MD, Chair of the department of medicine at Newton-Wellesley Hospital in Newton, Massachusetts, and assistant chief of medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and Tufts University School of Medicine, all in Boston. The authors disclosed no conflicts. Previously published in Gastro Hep Advances. 2023 Oct 12. doi: 10.1016/j.gastha.2023.10.004.

Pathological iron overload with end-organ damage in hemochromatosis occurs in individuals who are homozygous for the major mutation C282Y. Phenotypic hemochromatosis occurs much less frequently in compound heterozygotes with one C282Y mutation and one H63D mutation. Iron overload can be confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging, which shows a loss of signal intensity in affected tissues and avoids the need for liver biopsy.

The serum ferritin level, an acute phase reactant, may be elevated for reasons other than iron overload, including infection and malignancy; in such cases, the iron saturation is usually normal. In patients with liver disease, iron overload is not restricted to patients with genetic hemochromatosis. In nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), up to one-third of patients have an elevated iron saturation (> 45%) and an elevated serum ferritin level. Iron accumulation in NAFLD can occur in hepatocytes, the reticuloendothelial system, or both. Deposition of iron in the reticuloendothelial system has been implicated in more severe liver disease (steatohepatitis and fibrosis) in NAFLD. Hepatic iron accumulation is also frequent in alcohol-associated liver disease. In chronic hepatitis B and C, accumulation of hepatic iron is also recognized.

Dr. Martin is chief of the division of digestive health and liver diseases at the Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami, where he is the Mandel Chair of Gastroenterology. Dr. Friedman is the Anton R. Fried, MD, Chair of the department of medicine at Newton-Wellesley Hospital in Newton, Massachusetts, and assistant chief of medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and Tufts University School of Medicine, all in Boston. The authors disclosed no conflicts. Previously published in Gastro Hep Advances. 2023 Oct 12. doi: 10.1016/j.gastha.2023.10.004.

Statins and the liver: Not harmful and perhaps beneficial

, including glucose intolerance and hyperlipidemia. A lingering concern about potential hepatotoxicity has resulted in widespread reluctance to prescribe statins to treat hyperlipidemia in patients with liver disease; however, their safety in this setting has been documented in the literature as well as in clinical practice. Therefore, statins should not be withheld in patients with liver disease when indicated — with a few caveats. Baseline liver chemistries should be obtained. After initiation of statin therapy, a modest rise in serum aminotransferase levels may occur but is not an indication to discontinue the drug. In fact, monitoring of liver biochemical tests more frequently than is appropriate for any patient with chronic liver disease is unnecessary. The role of statins in cirrhosis may even expand, as recent reports suggest that statin use in patients with cirrhosis may slow the progression of liver disease and reduce the frequency of complications, such as hepatocellular carcinoma. These observations, however, require confirmation before statins can be suggested for any indication other than treating hyperlipidemia in patients with chronic liver disease, and statins are generally not appropriate in patients with decompensated cirrhosis.

Pearls from the Pros was published in Gastro Hep Advances .

Dr. Friedman is the Anton R. Fried, MD, Chair of the Department of Medicine at Newton-Wellesley Hospital in Newton, Mass., and assistant chief of medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and Tufts University, Boston. Dr. Martin is chief of the division of digestive health and liver diseases at the University of Miami, where he is the Mandel Chair of Gastroenterology. The authors disclose no conflicts.

, including glucose intolerance and hyperlipidemia. A lingering concern about potential hepatotoxicity has resulted in widespread reluctance to prescribe statins to treat hyperlipidemia in patients with liver disease; however, their safety in this setting has been documented in the literature as well as in clinical practice. Therefore, statins should not be withheld in patients with liver disease when indicated — with a few caveats. Baseline liver chemistries should be obtained. After initiation of statin therapy, a modest rise in serum aminotransferase levels may occur but is not an indication to discontinue the drug. In fact, monitoring of liver biochemical tests more frequently than is appropriate for any patient with chronic liver disease is unnecessary. The role of statins in cirrhosis may even expand, as recent reports suggest that statin use in patients with cirrhosis may slow the progression of liver disease and reduce the frequency of complications, such as hepatocellular carcinoma. These observations, however, require confirmation before statins can be suggested for any indication other than treating hyperlipidemia in patients with chronic liver disease, and statins are generally not appropriate in patients with decompensated cirrhosis.

Pearls from the Pros was published in Gastro Hep Advances .

Dr. Friedman is the Anton R. Fried, MD, Chair of the Department of Medicine at Newton-Wellesley Hospital in Newton, Mass., and assistant chief of medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and Tufts University, Boston. Dr. Martin is chief of the division of digestive health and liver diseases at the University of Miami, where he is the Mandel Chair of Gastroenterology. The authors disclose no conflicts.

, including glucose intolerance and hyperlipidemia. A lingering concern about potential hepatotoxicity has resulted in widespread reluctance to prescribe statins to treat hyperlipidemia in patients with liver disease; however, their safety in this setting has been documented in the literature as well as in clinical practice. Therefore, statins should not be withheld in patients with liver disease when indicated — with a few caveats. Baseline liver chemistries should be obtained. After initiation of statin therapy, a modest rise in serum aminotransferase levels may occur but is not an indication to discontinue the drug. In fact, monitoring of liver biochemical tests more frequently than is appropriate for any patient with chronic liver disease is unnecessary. The role of statins in cirrhosis may even expand, as recent reports suggest that statin use in patients with cirrhosis may slow the progression of liver disease and reduce the frequency of complications, such as hepatocellular carcinoma. These observations, however, require confirmation before statins can be suggested for any indication other than treating hyperlipidemia in patients with chronic liver disease, and statins are generally not appropriate in patients with decompensated cirrhosis.

Pearls from the Pros was published in Gastro Hep Advances .

Dr. Friedman is the Anton R. Fried, MD, Chair of the Department of Medicine at Newton-Wellesley Hospital in Newton, Mass., and assistant chief of medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and Tufts University, Boston. Dr. Martin is chief of the division of digestive health and liver diseases at the University of Miami, where he is the Mandel Chair of Gastroenterology. The authors disclose no conflicts.

Hepatic presentations of celiac disease

Liver biopsy findings may include variable degrees of steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis.

In one case we have seen, the patient presented with unexplained ascites and features suggestive of Budd-Chiari syndrome. The serum ascites albumin gradient was 2.3 with a total protein of 0.8 g/dL, and albumin 0.5 g/dL, with an ascitic WBC count of 88/mm3.

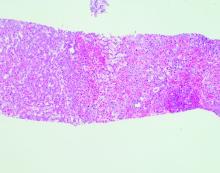

Echocardiography showed an ejection fraction of 80%. Transjugular liver biopsy revealed a normal hepatic venous pressure gradient but marked sinusoidal dilatation and congestion with hepatocyte atrophy and focal necrosis suggestive of vascular outlet obstruction (Figure 1).

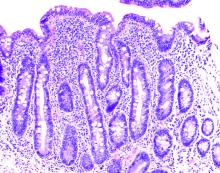

Hepatic venography, however, showed no evidence of Budd-Chiari syndrome. When seen in consultation, pertinent observations included Irish ancestry, a history of occasional diarrhea, short stature, osteoporosis, and an atrophic spleen on computed tomography. An IgA transglutaminase antibody was positive, and a small-bowel biopsy confirmed celiac disease (Figure 2).

On a gluten-free diet, the patient’s symptoms resolved, with clinical and laboratory abnormalities returning to normal. She lived another 20 years before dying of primary pulmonary hypertension. Recognition of an unusual hepatic manifestation of celiac disease led to effective management.

Dr. Friedman is the Anton R. Fried, MD, Chair of the department of medicine at Newton-Wellesley Hospital in Newton, Mass., and assistant chief of medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and Tufts University School of Medicine, all in Boston. Dr. Martin is chief of the division of digestive health and liver diseases at the Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami, where he is the Mandel Chair of Gastroenterology. The authors disclose no conflicts.

Previously published in Gastro Hep Advances. 2023. doi: 10.1016/j.gastha.2023.03.018.

Liver biopsy findings may include variable degrees of steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis.

In one case we have seen, the patient presented with unexplained ascites and features suggestive of Budd-Chiari syndrome. The serum ascites albumin gradient was 2.3 with a total protein of 0.8 g/dL, and albumin 0.5 g/dL, with an ascitic WBC count of 88/mm3.

Echocardiography showed an ejection fraction of 80%. Transjugular liver biopsy revealed a normal hepatic venous pressure gradient but marked sinusoidal dilatation and congestion with hepatocyte atrophy and focal necrosis suggestive of vascular outlet obstruction (Figure 1).

Hepatic venography, however, showed no evidence of Budd-Chiari syndrome. When seen in consultation, pertinent observations included Irish ancestry, a history of occasional diarrhea, short stature, osteoporosis, and an atrophic spleen on computed tomography. An IgA transglutaminase antibody was positive, and a small-bowel biopsy confirmed celiac disease (Figure 2).

On a gluten-free diet, the patient’s symptoms resolved, with clinical and laboratory abnormalities returning to normal. She lived another 20 years before dying of primary pulmonary hypertension. Recognition of an unusual hepatic manifestation of celiac disease led to effective management.

Dr. Friedman is the Anton R. Fried, MD, Chair of the department of medicine at Newton-Wellesley Hospital in Newton, Mass., and assistant chief of medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and Tufts University School of Medicine, all in Boston. Dr. Martin is chief of the division of digestive health and liver diseases at the Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami, where he is the Mandel Chair of Gastroenterology. The authors disclose no conflicts.

Previously published in Gastro Hep Advances. 2023. doi: 10.1016/j.gastha.2023.03.018.

Liver biopsy findings may include variable degrees of steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis.

In one case we have seen, the patient presented with unexplained ascites and features suggestive of Budd-Chiari syndrome. The serum ascites albumin gradient was 2.3 with a total protein of 0.8 g/dL, and albumin 0.5 g/dL, with an ascitic WBC count of 88/mm3.

Echocardiography showed an ejection fraction of 80%. Transjugular liver biopsy revealed a normal hepatic venous pressure gradient but marked sinusoidal dilatation and congestion with hepatocyte atrophy and focal necrosis suggestive of vascular outlet obstruction (Figure 1).

Hepatic venography, however, showed no evidence of Budd-Chiari syndrome. When seen in consultation, pertinent observations included Irish ancestry, a history of occasional diarrhea, short stature, osteoporosis, and an atrophic spleen on computed tomography. An IgA transglutaminase antibody was positive, and a small-bowel biopsy confirmed celiac disease (Figure 2).

On a gluten-free diet, the patient’s symptoms resolved, with clinical and laboratory abnormalities returning to normal. She lived another 20 years before dying of primary pulmonary hypertension. Recognition of an unusual hepatic manifestation of celiac disease led to effective management.

Dr. Friedman is the Anton R. Fried, MD, Chair of the department of medicine at Newton-Wellesley Hospital in Newton, Mass., and assistant chief of medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and Tufts University School of Medicine, all in Boston. Dr. Martin is chief of the division of digestive health and liver diseases at the Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami, where he is the Mandel Chair of Gastroenterology. The authors disclose no conflicts.

Previously published in Gastro Hep Advances. 2023. doi: 10.1016/j.gastha.2023.03.018.

Incidental hepatic steatosis

It is important to identify patients at risk of progressive fibrosis.

Calculation of the fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) score (based on age, alanine and aspartate aminotransferase [ALT and AST] levels, and platelet count by the primary care provider, using either an online calculator or the dot phrase “.fib4” in Epic) is a useful first step. If the value is low (with a high negative predictive value for advanced fibrosis), the patient does not need to be referred but can be managed for risk factors for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. If the value is high, suggesting advanced fibrosis, the patient requires further evaluation. If the value is indeterminate, options for assessing liver stiffness include vibration-controlled transient elastography (with a controlled attenuation parameter to assess the degree of steatosis) and ultrasound elastography. A low liver stiffness score argues against the need for subspecialty management. An indeterminate score may be followed by magnetic resonance elastography, if available. An alternative to elastography is the enhanced liver fibrosis (ELF) blood test, based on serum levels of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 1 (TIMP-1), amino-terminal propeptide of type III procollagen (PIIINP), and hyaluronic acid.

Dr. Friedman is the Anton R. Fried, MD, chair of the department of medicine at Newton-Wellesley Hospital in Newton, Mass., and assistant chief of medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and Tufts University, Boston. Dr. Martin is chief of the division of digestive health and liver diseases at the University of Miami, where he is the Mandel Chair of Gastroenterology. The authors disclose no conflicts.

Published previously in Gastro Hep Advances (doi: 10.1016/j.gastha.2023.03.008).

It is important to identify patients at risk of progressive fibrosis.

Calculation of the fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) score (based on age, alanine and aspartate aminotransferase [ALT and AST] levels, and platelet count by the primary care provider, using either an online calculator or the dot phrase “.fib4” in Epic) is a useful first step. If the value is low (with a high negative predictive value for advanced fibrosis), the patient does not need to be referred but can be managed for risk factors for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. If the value is high, suggesting advanced fibrosis, the patient requires further evaluation. If the value is indeterminate, options for assessing liver stiffness include vibration-controlled transient elastography (with a controlled attenuation parameter to assess the degree of steatosis) and ultrasound elastography. A low liver stiffness score argues against the need for subspecialty management. An indeterminate score may be followed by magnetic resonance elastography, if available. An alternative to elastography is the enhanced liver fibrosis (ELF) blood test, based on serum levels of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 1 (TIMP-1), amino-terminal propeptide of type III procollagen (PIIINP), and hyaluronic acid.

Dr. Friedman is the Anton R. Fried, MD, chair of the department of medicine at Newton-Wellesley Hospital in Newton, Mass., and assistant chief of medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and Tufts University, Boston. Dr. Martin is chief of the division of digestive health and liver diseases at the University of Miami, where he is the Mandel Chair of Gastroenterology. The authors disclose no conflicts.

Published previously in Gastro Hep Advances (doi: 10.1016/j.gastha.2023.03.008).

It is important to identify patients at risk of progressive fibrosis.

Calculation of the fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) score (based on age, alanine and aspartate aminotransferase [ALT and AST] levels, and platelet count by the primary care provider, using either an online calculator or the dot phrase “.fib4” in Epic) is a useful first step. If the value is low (with a high negative predictive value for advanced fibrosis), the patient does not need to be referred but can be managed for risk factors for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. If the value is high, suggesting advanced fibrosis, the patient requires further evaluation. If the value is indeterminate, options for assessing liver stiffness include vibration-controlled transient elastography (with a controlled attenuation parameter to assess the degree of steatosis) and ultrasound elastography. A low liver stiffness score argues against the need for subspecialty management. An indeterminate score may be followed by magnetic resonance elastography, if available. An alternative to elastography is the enhanced liver fibrosis (ELF) blood test, based on serum levels of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 1 (TIMP-1), amino-terminal propeptide of type III procollagen (PIIINP), and hyaluronic acid.

Dr. Friedman is the Anton R. Fried, MD, chair of the department of medicine at Newton-Wellesley Hospital in Newton, Mass., and assistant chief of medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and Tufts University, Boston. Dr. Martin is chief of the division of digestive health and liver diseases at the University of Miami, where he is the Mandel Chair of Gastroenterology. The authors disclose no conflicts.

Published previously in Gastro Hep Advances (doi: 10.1016/j.gastha.2023.03.008).

FROM GASTRO HEP ADVANCES

Introduction to Clinical Practice Update Committee articles

In this issue of Gastroenterology and in an upcoming issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, an important behind-the-scenes change is occurring. Specifically, both journals will continue to publish important and timely reviews and commentaries, but the formulation and design of some of these articles will now be driven by a new committee. The newly formed American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute Clinical Practice Updates Committee (CPUC) is charged with providing authoritative and balanced articles for the two journals that have the greatest impact on the clinical practice of gastroenterology and hepatology. Potential subjects for these articles will derive from several sources in coordination with the AGA Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee.

First, important topics that are proposed initially for an AGA guideline but do not meet rigid criteria for guideline grading will be sent to the CPUC for review and consideration. Second, ideas for topics will also be generated by the CPUC members and journal editors, as well as by other AGA committees and AGA members themselves. Third, summaries of important symposia such as the yearly Freston Conference will be included. Topics can be presented in the form of a comprehensive, narrative review or, for particularly timely issues in gastroenterology, hepatology, and health care in general, as a rapid commentary.

We believe that the vetting process of these articles is important. All prospective topics and selected authors will be approved by the CPUC with guidance from the AGA Institute Governing Board. At least 2 authors who are recognized authorities will be invited to write an article and will be chosen from different institutions. It is anticipated that the authors will often have differing opinions, to help ensure balance and achieve consensus. A member of the CPUC with expertise in the field will guide the writing to ensure the highest quality and greatest balance in the final product. Once an article is written, it will be submitted for evaluation by the Editors of Gastroenterology and Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, who will decide whether to accept the paper or send it for further review before acceptance.

With seasoned and motivated authors and the guidance of the CPUC, we expect outstanding reviews that will be published in a timely manner and provide AGA members and readers of the journals the most up-to-date and scholarly information across the spectrum of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition. We are excited about this new process as a means to enhance our already outstanding journals, which are dedicated to publishing the best research and practice information in our field. Because this is a new process, we welcome feedback and suggestions for improvement and look forward to providing content that helps your research and clinical practice.

Dr. Katzka is at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.; Dr. Friedman is at Newton-Wellesley Hospital, Newton, Mass.; Dr. Inadomi is at University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle; Dr. Kalloo is at Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore; Dr. Kim is at South Denver Gastroenterology, P.C., Littleton, Colo.; Dr. Koch is at Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle; Dr. Lieberman is at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland; Dr. Lichtenstein is at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Merion Station, Penn.: Dr. Lim is at Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn.; Dr. Pandolfino is at Northwestern University, Chicago; Dr. Shin is at Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis; and Dr. Siedler is Committee Liaison, American Gastroenterological Association.

In this issue of Gastroenterology and in an upcoming issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, an important behind-the-scenes change is occurring. Specifically, both journals will continue to publish important and timely reviews and commentaries, but the formulation and design of some of these articles will now be driven by a new committee. The newly formed American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute Clinical Practice Updates Committee (CPUC) is charged with providing authoritative and balanced articles for the two journals that have the greatest impact on the clinical practice of gastroenterology and hepatology. Potential subjects for these articles will derive from several sources in coordination with the AGA Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee.

First, important topics that are proposed initially for an AGA guideline but do not meet rigid criteria for guideline grading will be sent to the CPUC for review and consideration. Second, ideas for topics will also be generated by the CPUC members and journal editors, as well as by other AGA committees and AGA members themselves. Third, summaries of important symposia such as the yearly Freston Conference will be included. Topics can be presented in the form of a comprehensive, narrative review or, for particularly timely issues in gastroenterology, hepatology, and health care in general, as a rapid commentary.

We believe that the vetting process of these articles is important. All prospective topics and selected authors will be approved by the CPUC with guidance from the AGA Institute Governing Board. At least 2 authors who are recognized authorities will be invited to write an article and will be chosen from different institutions. It is anticipated that the authors will often have differing opinions, to help ensure balance and achieve consensus. A member of the CPUC with expertise in the field will guide the writing to ensure the highest quality and greatest balance in the final product. Once an article is written, it will be submitted for evaluation by the Editors of Gastroenterology and Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, who will decide whether to accept the paper or send it for further review before acceptance.

With seasoned and motivated authors and the guidance of the CPUC, we expect outstanding reviews that will be published in a timely manner and provide AGA members and readers of the journals the most up-to-date and scholarly information across the spectrum of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition. We are excited about this new process as a means to enhance our already outstanding journals, which are dedicated to publishing the best research and practice information in our field. Because this is a new process, we welcome feedback and suggestions for improvement and look forward to providing content that helps your research and clinical practice.

Dr. Katzka is at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.; Dr. Friedman is at Newton-Wellesley Hospital, Newton, Mass.; Dr. Inadomi is at University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle; Dr. Kalloo is at Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore; Dr. Kim is at South Denver Gastroenterology, P.C., Littleton, Colo.; Dr. Koch is at Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle; Dr. Lieberman is at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland; Dr. Lichtenstein is at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Merion Station, Penn.: Dr. Lim is at Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn.; Dr. Pandolfino is at Northwestern University, Chicago; Dr. Shin is at Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis; and Dr. Siedler is Committee Liaison, American Gastroenterological Association.

In this issue of Gastroenterology and in an upcoming issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, an important behind-the-scenes change is occurring. Specifically, both journals will continue to publish important and timely reviews and commentaries, but the formulation and design of some of these articles will now be driven by a new committee. The newly formed American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute Clinical Practice Updates Committee (CPUC) is charged with providing authoritative and balanced articles for the two journals that have the greatest impact on the clinical practice of gastroenterology and hepatology. Potential subjects for these articles will derive from several sources in coordination with the AGA Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee.

First, important topics that are proposed initially for an AGA guideline but do not meet rigid criteria for guideline grading will be sent to the CPUC for review and consideration. Second, ideas for topics will also be generated by the CPUC members and journal editors, as well as by other AGA committees and AGA members themselves. Third, summaries of important symposia such as the yearly Freston Conference will be included. Topics can be presented in the form of a comprehensive, narrative review or, for particularly timely issues in gastroenterology, hepatology, and health care in general, as a rapid commentary.

We believe that the vetting process of these articles is important. All prospective topics and selected authors will be approved by the CPUC with guidance from the AGA Institute Governing Board. At least 2 authors who are recognized authorities will be invited to write an article and will be chosen from different institutions. It is anticipated that the authors will often have differing opinions, to help ensure balance and achieve consensus. A member of the CPUC with expertise in the field will guide the writing to ensure the highest quality and greatest balance in the final product. Once an article is written, it will be submitted for evaluation by the Editors of Gastroenterology and Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, who will decide whether to accept the paper or send it for further review before acceptance.

With seasoned and motivated authors and the guidance of the CPUC, we expect outstanding reviews that will be published in a timely manner and provide AGA members and readers of the journals the most up-to-date and scholarly information across the spectrum of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition. We are excited about this new process as a means to enhance our already outstanding journals, which are dedicated to publishing the best research and practice information in our field. Because this is a new process, we welcome feedback and suggestions for improvement and look forward to providing content that helps your research and clinical practice.

Dr. Katzka is at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.; Dr. Friedman is at Newton-Wellesley Hospital, Newton, Mass.; Dr. Inadomi is at University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle; Dr. Kalloo is at Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore; Dr. Kim is at South Denver Gastroenterology, P.C., Littleton, Colo.; Dr. Koch is at Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle; Dr. Lieberman is at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland; Dr. Lichtenstein is at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Merion Station, Penn.: Dr. Lim is at Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn.; Dr. Pandolfino is at Northwestern University, Chicago; Dr. Shin is at Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis; and Dr. Siedler is Committee Liaison, American Gastroenterological Association.