User login

Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis

Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis of Gougerot and Carteaud, also known as Gougerot-Carteaud syndrome, is an uncommon skin disorder of young individuals characterized by hyperkeratotic or verrucous brown papules or plaques that coalesce centrally and by a reticulated pattern peripherally. It was first described by two French dermatologists, Gougerot and Carteaud, in 1927.1 Initially, the distinct entity of CARP was contested, with some dermatologists believing it to be a variant of acanthosis nigricans. However, CARP is now recognized as a distinct, though rare, dermatosis.

Histopathology reveals findings similar to those that may be found in acanthosis nigricans and epidermal nevi. Classic characteristics of CARP include hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, increased basal melanin pigmentation, and mild acanthosis. Occasionally, there may be perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates in the superficial dermis.3,4

The etiology of CARP is unknown. CARP’s resolution in response to antibiotics and the isolation of two bacterial actinomycetes, Rhodococcus and Dietzia papillomatosis, from skin scrapings of CARP patients have led some to believe that its etiology is bacterial. However, no bacterial species have been consistently isolated from CARP patients. The prevailing theory of the past was that CARP was an abnormal host response to the fungus Malassezia furfur. Inconsistent detection of the fungus in skin scrapings, as well as persistence of the skin lesions after fungal clearance with antifungal therapy, has debunked this theory. An underlying disorder of keratinization resulting in hyperproliferation also has been suggested given reports of familial CARP and electron microscopy studies demonstrating focal-enhanced expression of keratin-16 in the stratum granulosom.5 Other theories include a cutaneous response to underlying endocrinopathies, ultraviolet light, and localized amyloidosis.1

Diagnosis and differential

CARP is poorly recognized by clinicians and frequently initially misdiagnosed due to its similar appearance to other disorders, most commonly tinea versicolor and acanthosis nigricans. Davis et al. proposed criteria for diagnosis of CARP requiring 1) presence of scaly, reticulated and papillomatous brown macules and patches; 2) distribution over the upper trunk and neck; 3) negative fungal staining of scales; 4) no improvement following antifungal treatment; and 5) improvement following minocycline.2

Tinea versicolor may appear similar to CARP, but unlike CARP, will respond to antifungal treatment and may demonstrate hyphae and yeast on KOH preparation. Acanthosis nigricans and CARP both may present with velvety, hyperpigmented plaques in individuals of obese habitus or with insulin resistance, but peripheral reticulation will be absent in acanthosis nigricans. However, acanthosis nigricans and CARP may coexist, and this coexistence is not uncommonly seen in individuals with obesity and/or insulin resistance. Darier’s disease may look similar to cases of CARP without pigmentary change, but it often will have accompanying nail changes. Macular or lichen amyloidosis may present with pruritic brown macules or papules, but skin biopsy will have positive amyloid staining. The use of 70% alcohol swabbing to diagnose terra firma-forme dermatosis, with lesions disappearing with swabbing, is classic and used to differentiate it from CARP. Other conditions to consider include seborrheic dermatitis, epidermal nevi, verruca plana, epidermodysplasia verruciformis, and acne vulgaris.1,2,4

Treatment

Minocycline is the first-line treatment for CARP: 80% of patients may have complete resolution with minocycline, while the remainder experience at least 50% clearance of skin lesions.2 However, recurrence after stopping minocycline treatment is not uncommon. The mechanism by which minocycline works is unknown. Second-line treatment for those who cannot tolerate minocycline are macrolide antibiotics.6 Other treatment options with reported success include oral isotretinoin and topical retinoids, including tretinoin gel and tazarotene cream.3,7 Appropriate strength topical corticosteroids may be used for pruritus.

Ms. Han is a medical student at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego, as well as the vice chair of the department of dermatology and a professor of dermatology and pediatrics at UC San Diego. They report having no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures. Email them at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

References

1. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2016 Aug 25;9:217-23.

2. Br J Dermatol. 2006 Feb;154(2):287-93.

3. Arch Dermatol. 2012 Apr;148(4):505-8.

4. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003 Dec;49(6):1182-4.

5. Arch Dermatol. 2002 Feb;138(2):276-7.

6. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44(4):652-5.

7. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7(5):305-13.

Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis of Gougerot and Carteaud, also known as Gougerot-Carteaud syndrome, is an uncommon skin disorder of young individuals characterized by hyperkeratotic or verrucous brown papules or plaques that coalesce centrally and by a reticulated pattern peripherally. It was first described by two French dermatologists, Gougerot and Carteaud, in 1927.1 Initially, the distinct entity of CARP was contested, with some dermatologists believing it to be a variant of acanthosis nigricans. However, CARP is now recognized as a distinct, though rare, dermatosis.

Histopathology reveals findings similar to those that may be found in acanthosis nigricans and epidermal nevi. Classic characteristics of CARP include hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, increased basal melanin pigmentation, and mild acanthosis. Occasionally, there may be perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates in the superficial dermis.3,4

The etiology of CARP is unknown. CARP’s resolution in response to antibiotics and the isolation of two bacterial actinomycetes, Rhodococcus and Dietzia papillomatosis, from skin scrapings of CARP patients have led some to believe that its etiology is bacterial. However, no bacterial species have been consistently isolated from CARP patients. The prevailing theory of the past was that CARP was an abnormal host response to the fungus Malassezia furfur. Inconsistent detection of the fungus in skin scrapings, as well as persistence of the skin lesions after fungal clearance with antifungal therapy, has debunked this theory. An underlying disorder of keratinization resulting in hyperproliferation also has been suggested given reports of familial CARP and electron microscopy studies demonstrating focal-enhanced expression of keratin-16 in the stratum granulosom.5 Other theories include a cutaneous response to underlying endocrinopathies, ultraviolet light, and localized amyloidosis.1

Diagnosis and differential

CARP is poorly recognized by clinicians and frequently initially misdiagnosed due to its similar appearance to other disorders, most commonly tinea versicolor and acanthosis nigricans. Davis et al. proposed criteria for diagnosis of CARP requiring 1) presence of scaly, reticulated and papillomatous brown macules and patches; 2) distribution over the upper trunk and neck; 3) negative fungal staining of scales; 4) no improvement following antifungal treatment; and 5) improvement following minocycline.2

Tinea versicolor may appear similar to CARP, but unlike CARP, will respond to antifungal treatment and may demonstrate hyphae and yeast on KOH preparation. Acanthosis nigricans and CARP both may present with velvety, hyperpigmented plaques in individuals of obese habitus or with insulin resistance, but peripheral reticulation will be absent in acanthosis nigricans. However, acanthosis nigricans and CARP may coexist, and this coexistence is not uncommonly seen in individuals with obesity and/or insulin resistance. Darier’s disease may look similar to cases of CARP without pigmentary change, but it often will have accompanying nail changes. Macular or lichen amyloidosis may present with pruritic brown macules or papules, but skin biopsy will have positive amyloid staining. The use of 70% alcohol swabbing to diagnose terra firma-forme dermatosis, with lesions disappearing with swabbing, is classic and used to differentiate it from CARP. Other conditions to consider include seborrheic dermatitis, epidermal nevi, verruca plana, epidermodysplasia verruciformis, and acne vulgaris.1,2,4

Treatment

Minocycline is the first-line treatment for CARP: 80% of patients may have complete resolution with minocycline, while the remainder experience at least 50% clearance of skin lesions.2 However, recurrence after stopping minocycline treatment is not uncommon. The mechanism by which minocycline works is unknown. Second-line treatment for those who cannot tolerate minocycline are macrolide antibiotics.6 Other treatment options with reported success include oral isotretinoin and topical retinoids, including tretinoin gel and tazarotene cream.3,7 Appropriate strength topical corticosteroids may be used for pruritus.

Ms. Han is a medical student at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego, as well as the vice chair of the department of dermatology and a professor of dermatology and pediatrics at UC San Diego. They report having no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures. Email them at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

References

1. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2016 Aug 25;9:217-23.

2. Br J Dermatol. 2006 Feb;154(2):287-93.

3. Arch Dermatol. 2012 Apr;148(4):505-8.

4. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003 Dec;49(6):1182-4.

5. Arch Dermatol. 2002 Feb;138(2):276-7.

6. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44(4):652-5.

7. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7(5):305-13.

Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis of Gougerot and Carteaud, also known as Gougerot-Carteaud syndrome, is an uncommon skin disorder of young individuals characterized by hyperkeratotic or verrucous brown papules or plaques that coalesce centrally and by a reticulated pattern peripherally. It was first described by two French dermatologists, Gougerot and Carteaud, in 1927.1 Initially, the distinct entity of CARP was contested, with some dermatologists believing it to be a variant of acanthosis nigricans. However, CARP is now recognized as a distinct, though rare, dermatosis.

Histopathology reveals findings similar to those that may be found in acanthosis nigricans and epidermal nevi. Classic characteristics of CARP include hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, increased basal melanin pigmentation, and mild acanthosis. Occasionally, there may be perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates in the superficial dermis.3,4

The etiology of CARP is unknown. CARP’s resolution in response to antibiotics and the isolation of two bacterial actinomycetes, Rhodococcus and Dietzia papillomatosis, from skin scrapings of CARP patients have led some to believe that its etiology is bacterial. However, no bacterial species have been consistently isolated from CARP patients. The prevailing theory of the past was that CARP was an abnormal host response to the fungus Malassezia furfur. Inconsistent detection of the fungus in skin scrapings, as well as persistence of the skin lesions after fungal clearance with antifungal therapy, has debunked this theory. An underlying disorder of keratinization resulting in hyperproliferation also has been suggested given reports of familial CARP and electron microscopy studies demonstrating focal-enhanced expression of keratin-16 in the stratum granulosom.5 Other theories include a cutaneous response to underlying endocrinopathies, ultraviolet light, and localized amyloidosis.1

Diagnosis and differential

CARP is poorly recognized by clinicians and frequently initially misdiagnosed due to its similar appearance to other disorders, most commonly tinea versicolor and acanthosis nigricans. Davis et al. proposed criteria for diagnosis of CARP requiring 1) presence of scaly, reticulated and papillomatous brown macules and patches; 2) distribution over the upper trunk and neck; 3) negative fungal staining of scales; 4) no improvement following antifungal treatment; and 5) improvement following minocycline.2

Tinea versicolor may appear similar to CARP, but unlike CARP, will respond to antifungal treatment and may demonstrate hyphae and yeast on KOH preparation. Acanthosis nigricans and CARP both may present with velvety, hyperpigmented plaques in individuals of obese habitus or with insulin resistance, but peripheral reticulation will be absent in acanthosis nigricans. However, acanthosis nigricans and CARP may coexist, and this coexistence is not uncommonly seen in individuals with obesity and/or insulin resistance. Darier’s disease may look similar to cases of CARP without pigmentary change, but it often will have accompanying nail changes. Macular or lichen amyloidosis may present with pruritic brown macules or papules, but skin biopsy will have positive amyloid staining. The use of 70% alcohol swabbing to diagnose terra firma-forme dermatosis, with lesions disappearing with swabbing, is classic and used to differentiate it from CARP. Other conditions to consider include seborrheic dermatitis, epidermal nevi, verruca plana, epidermodysplasia verruciformis, and acne vulgaris.1,2,4

Treatment

Minocycline is the first-line treatment for CARP: 80% of patients may have complete resolution with minocycline, while the remainder experience at least 50% clearance of skin lesions.2 However, recurrence after stopping minocycline treatment is not uncommon. The mechanism by which minocycline works is unknown. Second-line treatment for those who cannot tolerate minocycline are macrolide antibiotics.6 Other treatment options with reported success include oral isotretinoin and topical retinoids, including tretinoin gel and tazarotene cream.3,7 Appropriate strength topical corticosteroids may be used for pruritus.

Ms. Han is a medical student at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego, as well as the vice chair of the department of dermatology and a professor of dermatology and pediatrics at UC San Diego. They report having no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures. Email them at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

References

1. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2016 Aug 25;9:217-23.

2. Br J Dermatol. 2006 Feb;154(2):287-93.

3. Arch Dermatol. 2012 Apr;148(4):505-8.

4. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003 Dec;49(6):1182-4.

5. Arch Dermatol. 2002 Feb;138(2):276-7.

6. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44(4):652-5.

7. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7(5):305-13.

A 17-year-old male presents to the dermatology clinic for brown lesions on his central chest and back that have been present for about a year. The brown areas gradually have become scaly over time. They are asymptomatic. His pediatrician had given him hydrocortisone ointment to apply to the lesions, but there was no improvement. Review of systems was otherwise negative.

50 years of pediatric dermatology

The world in pediatric dermatology has changed in incredible ways since 1967. In fact, pediatric dermatology was not an organized specialty until years later! This article will look back at some of the history of pediatric dermatology, exploring how different the field was 50 years ago, and how it has evolved into the vibrant field that it is. By looking at some disease states, and differences in practice in relation to the care of dermatologic conditions in children both by pediatricians and dermatologists, we can see the tremendous evolution in our understanding and management of pediatric skin conditions, and perhaps gain insight into the future.

Pediatric dermatology was fairly “neonatal” 50 years ago, with only a few practitioners in the field. Recognizing that up to 30% of pediatric primary care visits include a skin-related problem, and that there was limited training about skin diseases among primary care practitioners and inconsistent training amongst dermatologists, there was a clinical need for establishing the subspecialty of pediatric dermatology. The first international symposium was held in Mexico City in October 1972, and with this meeting the International Society of Pediatric Dermatology was founded. The Society for Pediatric Dermatology (SPD) began in 1973, with Alvin Jacobs, MD, Samuel Weinberg, MD, Nancy Esterly, MD, Sidney Hurwitz, MD, William Weston, MD, and Coleman Jacobson, MD, as some of the initial “founding mothers and fathers.” The journal Pediatric Dermatology released its first issue in 1982 (35 years ago), and the American Academy of Pediatrics did not have a section of dermatology until 1986.

Pediatrics and dermatology: The interface

Many of the first generation of pediatric dermatologists trained as pediatricians prior to pursuing their dermatology work, with some being “assigned” dermatology as pediatric experts, while others did formal residencies in dermatology. This history is important, as pediatric dermatology was, and remains, integrated with pediatrics, even while training in dermatology residencies became standard practice. An important part of the development of the field has been the education of pediatricians and dermatologists by pediatric dermatologists, with a strong sensibility that improved training for both generalists and specialists about pediatric skin disease would yield better care for patients and families.

Initially, there were very few pediatric or dermatology programs in the United States that had pediatric dermatologists. Over the succeeding decades, this is now less common, although even now there are still dermatology and pediatric residency programs that do not have a pediatric dermatologist for either training or to serve their patients. The founding leaders of the SPD set a tone of collaboration nationally and internationally, reaching out to pediatric colleagues and dermatology associates from around the world, and establishing superb educational programs for the exchange of ideas, presentation of challenging cases, and promoting state of the art knowledge of the field. Through annual meetings of the SPD, conferences immediately preceding the American Academy of Dermatology annual meetings, the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology, and other regional and international meetings, the field developed as the number of practitioners grew, and as the specialized published literature reflected new knowledge in diagnosis and therapy.

Building upon the history of collaboration and reflecting the maturation of the field with a desire to influence the breadth and quantity of research in pediatric dermatology, the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance (PeDRA) was formed in 2012. This organization was formed to promote and facilitate high quality collaborative clinical, translational, educational, and basic science research in pediatric dermatology with a vision to create sustainable, collaborative networks to better understand, prevent, treat, and cure dermatologic diseases in children. This network is now composed of over 230 members representing over 68 institutions from the United States and Canada, but including involvement globally from Mexico, Europe, and the Middle East.

Examples of changing perspectives: hemangiomas

A good way to look at evolution of the field is take a look at some of the similarities and differences in clinical practice in relation to common and uncommon disease states.

A great example is hemangiomas. Some of the first natural history studies on hemangiomas were done in the early 1960s, establishing that many lesions had a typical clinical course of fairly rapid growth, plateau, and involution over time. Of course, the identification of hemangiomas of infancy (or “HOI” in the trade), was confused with vascular malformations, and no one had recognized variant tumors that were distinct, such as rapidly involuting and noninvoluting congenital hemangiomas (RICHs or NICHs), tufted angiomas, and hemangioendotheliomas. PHACE syndrome (posterior fossa brain malformations) had yet to be described (that was done in 1996 by Ilona Frieden and her colleagues). For a time period, hemangiomas were treated with X-rays, before the negative impact of such radiation was acknowledged. For many years after that, even deforming and functionally significant lesions were “followed clinically” for natural involution, presumably a backlash from the radiation therapy interventions.

This story also reflects how organized research efforts helped with the evolution of knowledge and clinical care. The Hemangioma of Infancy Group was formed to take a collaborative approach to characterize and study hemangiomas and related tumors. Beginning with energetic, insightful pediatric dermatologists, and little funding, they changed our knowledge base of how hemangiomas present, the risk factors for their development and the characteristics and multiple organ findings associated with PHACE and other syndromic hemangiomas.

Procedural pediatric dermatology: Tremendous revolution in surgery and laser

The first generation of pediatric dermatologists were considered medical dermatologist specialists. And how important this specialty work was! Acne, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, diaper and seborrheic dermatitis, and rare genetic syndromes, these conditions were a major part of the work of early pediatric dermatologists (and remain so now). What was not common was for pediatric dermatologists to have procedural or surgical practices, while this now is routinely part of the work of specialists in the field. How did this shift occur?

The fundamental shift began to occur with the introduction of the pulsed dye laser in 1989 and the publication of a seminal article in the New England Journal of Medicine (1989 Feb 16;320[7]:416-21) on its utility in treating port-wine stains in children with minimal scarring. Vascular lesions including port-wine stains were common, and pediatric dermatologists managed these patients for both diagnosis and medical management. Also, dermatology residencies at this time offered training in cutaneous surgery, excisions (including Mohs surgery) and repairs, and trainees in pediatric dermatology were “trained up” to high levels of expertise. As lasers were incorporated into dermatology residency work and practices, pediatric dermatologists had the exposure and skill to do this work. An added advantage was having the pediatric knowledge of how to handle children and adolescents in an age appropriate manner, and consideration of methods to minimize the pain and anxiety of procedures. Within a few years, pediatric dermatologists were at the forefront of the use of topical anesthetics (EMLA and liposomal lidocaine) and had general anesthesia privileges for laser and excisional surgery.

So while pediatric dermatologists still do “small procedures” every hour in most practices (cryotherapy for warts, cantharidin for molluscum, shave and punch biopsies), a subset now have extensive procedural practices, which in recent years has extended to pigment lesion lasers (to treat nevus of Ota), hair lasers (to treat perineal areas to prevent pilonidal cyst recurrence or to treat hirsutism), and combinations of lasers to treat hypertrophic, constrictive, and/or deforming scars).

Inflammatory skin disorders: Bread and butter ... and peanut butter?

The care of pediatric inflammatory skin disorders has evolved, but more slowly for some diseases than others. Acne vulgaris now is recognized as much more common under age 12 years than previously, presumably reflecting earlier pubertal changes in our preteens. Over the past 30 years, therapy has evolved with the use of topical retinoids (still underused by pediatricians, considered a “practice gap”), hormonal therapy with combined oral contraceptives, and oral isotretinoin, a powerful but highly effective systemic agent for severe and refractory acne. Specific pediatric guidelines came much later. Pediatric acne expert recommendations were formulated by the American Acne and Rosacea Society and endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics in 2013 (Pediatrics. 2013;131:S163-86). Over the past few years, there is a push by experts for more judicious use of antibiotics for acne (oral and topical) to minimize the emergence of bacterial resistance.

Psoriasis has been a condition that has been “behind the revolution,” in that no biologic agent was approved for pediatric psoriasis in the United States until several months ago, lagging behind Europe and elsewhere in the world by almost a decade. Adult psoriasis has been recognized to be associated with a broad set of comorbidities, including obesity and early heart disease, and there is now research on how children are at risk as well, and new recommendations on how to screen children with psoriasis. Moderate to severe psoriasis in adults is now tremendously controllable with biologic agents targeting TNF-alpha, IL 12/23, and IL-17. Etanercept has been approved for children with psoriasis aged 4 years and older, and other biologic agents are under study.

Atopic dermatitis now is ready for its revolution! AD has increased in prevalence from around 5% of the pediatric population 30-plus years ago to 10%-15%. Treatment of most individuals has remained the same over the decades: Good skin care, frequent moisturizers, topical corticosteroids for flares, management of infection if noted. The topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs) broadened the therapeutic approach when introduced in 2000 and 2001, but the boxed warning resulted in some practitioners minimizing their utilization of these useful agents.

It has been recognized for years that children with AD have higher risk of developing food allergies than children without AD. A changing understanding of how early food exposure may induce tolerance is changing the world of allergy and influencing the care of children with AD. This is where the peanut butter (or other processed peanut, such as “Bamba”) may be life saving. New guidelines have come from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases recommending that infants with severe eczema (or egg allergy, or both) have introduction of age-appropriate peanut-containing food as early as 4-6 months of age to reduce the risk of development of peanut allergy. It is recommended that these infants undergo early evaluation for possible sensitization to peanut protein, with referral to allergists for skin prick tests or serum IgE screens (though if positive, referral to allergists is appropriate), and assess the safety of going ahead with early feeding. It is hoped that following these new guidelines can minimize the development of peanut allergy.

The future

Where will pediatric skin disease, or more importantly, skin health over a lifetime be in 50 years? Can we cure or prevent the consequences of our lethal and life altering genetic diseases such as epidermolysis bullosa or our neurocutaneous disorders? Will our new insights into birthmarks (they are mostly somatic mutations) allow us to form specific, personalized therapies to minimize their impact? Will we be using computers equipped with imaging devices and algorithms to assess our patients’ moles, papules, and nodules? Will our vaccines have wiped out warts, molluscum, and perhaps, acne? Will we have cured our inflammatory skin disorders, or perhaps prevented them by interventions in the neonatal period? No predictions will be offered here, other than that we can look forward to incredible changes for our future generations of health care practitioners, patients, and families.

Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield has served as a consultant for Anacor/Pfizer and Regeneron/Sanofi. Email him at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

The world in pediatric dermatology has changed in incredible ways since 1967. In fact, pediatric dermatology was not an organized specialty until years later! This article will look back at some of the history of pediatric dermatology, exploring how different the field was 50 years ago, and how it has evolved into the vibrant field that it is. By looking at some disease states, and differences in practice in relation to the care of dermatologic conditions in children both by pediatricians and dermatologists, we can see the tremendous evolution in our understanding and management of pediatric skin conditions, and perhaps gain insight into the future.

Pediatric dermatology was fairly “neonatal” 50 years ago, with only a few practitioners in the field. Recognizing that up to 30% of pediatric primary care visits include a skin-related problem, and that there was limited training about skin diseases among primary care practitioners and inconsistent training amongst dermatologists, there was a clinical need for establishing the subspecialty of pediatric dermatology. The first international symposium was held in Mexico City in October 1972, and with this meeting the International Society of Pediatric Dermatology was founded. The Society for Pediatric Dermatology (SPD) began in 1973, with Alvin Jacobs, MD, Samuel Weinberg, MD, Nancy Esterly, MD, Sidney Hurwitz, MD, William Weston, MD, and Coleman Jacobson, MD, as some of the initial “founding mothers and fathers.” The journal Pediatric Dermatology released its first issue in 1982 (35 years ago), and the American Academy of Pediatrics did not have a section of dermatology until 1986.

Pediatrics and dermatology: The interface

Many of the first generation of pediatric dermatologists trained as pediatricians prior to pursuing their dermatology work, with some being “assigned” dermatology as pediatric experts, while others did formal residencies in dermatology. This history is important, as pediatric dermatology was, and remains, integrated with pediatrics, even while training in dermatology residencies became standard practice. An important part of the development of the field has been the education of pediatricians and dermatologists by pediatric dermatologists, with a strong sensibility that improved training for both generalists and specialists about pediatric skin disease would yield better care for patients and families.

Initially, there were very few pediatric or dermatology programs in the United States that had pediatric dermatologists. Over the succeeding decades, this is now less common, although even now there are still dermatology and pediatric residency programs that do not have a pediatric dermatologist for either training or to serve their patients. The founding leaders of the SPD set a tone of collaboration nationally and internationally, reaching out to pediatric colleagues and dermatology associates from around the world, and establishing superb educational programs for the exchange of ideas, presentation of challenging cases, and promoting state of the art knowledge of the field. Through annual meetings of the SPD, conferences immediately preceding the American Academy of Dermatology annual meetings, the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology, and other regional and international meetings, the field developed as the number of practitioners grew, and as the specialized published literature reflected new knowledge in diagnosis and therapy.

Building upon the history of collaboration and reflecting the maturation of the field with a desire to influence the breadth and quantity of research in pediatric dermatology, the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance (PeDRA) was formed in 2012. This organization was formed to promote and facilitate high quality collaborative clinical, translational, educational, and basic science research in pediatric dermatology with a vision to create sustainable, collaborative networks to better understand, prevent, treat, and cure dermatologic diseases in children. This network is now composed of over 230 members representing over 68 institutions from the United States and Canada, but including involvement globally from Mexico, Europe, and the Middle East.

Examples of changing perspectives: hemangiomas

A good way to look at evolution of the field is take a look at some of the similarities and differences in clinical practice in relation to common and uncommon disease states.

A great example is hemangiomas. Some of the first natural history studies on hemangiomas were done in the early 1960s, establishing that many lesions had a typical clinical course of fairly rapid growth, plateau, and involution over time. Of course, the identification of hemangiomas of infancy (or “HOI” in the trade), was confused with vascular malformations, and no one had recognized variant tumors that were distinct, such as rapidly involuting and noninvoluting congenital hemangiomas (RICHs or NICHs), tufted angiomas, and hemangioendotheliomas. PHACE syndrome (posterior fossa brain malformations) had yet to be described (that was done in 1996 by Ilona Frieden and her colleagues). For a time period, hemangiomas were treated with X-rays, before the negative impact of such radiation was acknowledged. For many years after that, even deforming and functionally significant lesions were “followed clinically” for natural involution, presumably a backlash from the radiation therapy interventions.

This story also reflects how organized research efforts helped with the evolution of knowledge and clinical care. The Hemangioma of Infancy Group was formed to take a collaborative approach to characterize and study hemangiomas and related tumors. Beginning with energetic, insightful pediatric dermatologists, and little funding, they changed our knowledge base of how hemangiomas present, the risk factors for their development and the characteristics and multiple organ findings associated with PHACE and other syndromic hemangiomas.

Procedural pediatric dermatology: Tremendous revolution in surgery and laser

The first generation of pediatric dermatologists were considered medical dermatologist specialists. And how important this specialty work was! Acne, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, diaper and seborrheic dermatitis, and rare genetic syndromes, these conditions were a major part of the work of early pediatric dermatologists (and remain so now). What was not common was for pediatric dermatologists to have procedural or surgical practices, while this now is routinely part of the work of specialists in the field. How did this shift occur?

The fundamental shift began to occur with the introduction of the pulsed dye laser in 1989 and the publication of a seminal article in the New England Journal of Medicine (1989 Feb 16;320[7]:416-21) on its utility in treating port-wine stains in children with minimal scarring. Vascular lesions including port-wine stains were common, and pediatric dermatologists managed these patients for both diagnosis and medical management. Also, dermatology residencies at this time offered training in cutaneous surgery, excisions (including Mohs surgery) and repairs, and trainees in pediatric dermatology were “trained up” to high levels of expertise. As lasers were incorporated into dermatology residency work and practices, pediatric dermatologists had the exposure and skill to do this work. An added advantage was having the pediatric knowledge of how to handle children and adolescents in an age appropriate manner, and consideration of methods to minimize the pain and anxiety of procedures. Within a few years, pediatric dermatologists were at the forefront of the use of topical anesthetics (EMLA and liposomal lidocaine) and had general anesthesia privileges for laser and excisional surgery.

So while pediatric dermatologists still do “small procedures” every hour in most practices (cryotherapy for warts, cantharidin for molluscum, shave and punch biopsies), a subset now have extensive procedural practices, which in recent years has extended to pigment lesion lasers (to treat nevus of Ota), hair lasers (to treat perineal areas to prevent pilonidal cyst recurrence or to treat hirsutism), and combinations of lasers to treat hypertrophic, constrictive, and/or deforming scars).

Inflammatory skin disorders: Bread and butter ... and peanut butter?

The care of pediatric inflammatory skin disorders has evolved, but more slowly for some diseases than others. Acne vulgaris now is recognized as much more common under age 12 years than previously, presumably reflecting earlier pubertal changes in our preteens. Over the past 30 years, therapy has evolved with the use of topical retinoids (still underused by pediatricians, considered a “practice gap”), hormonal therapy with combined oral contraceptives, and oral isotretinoin, a powerful but highly effective systemic agent for severe and refractory acne. Specific pediatric guidelines came much later. Pediatric acne expert recommendations were formulated by the American Acne and Rosacea Society and endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics in 2013 (Pediatrics. 2013;131:S163-86). Over the past few years, there is a push by experts for more judicious use of antibiotics for acne (oral and topical) to minimize the emergence of bacterial resistance.

Psoriasis has been a condition that has been “behind the revolution,” in that no biologic agent was approved for pediatric psoriasis in the United States until several months ago, lagging behind Europe and elsewhere in the world by almost a decade. Adult psoriasis has been recognized to be associated with a broad set of comorbidities, including obesity and early heart disease, and there is now research on how children are at risk as well, and new recommendations on how to screen children with psoriasis. Moderate to severe psoriasis in adults is now tremendously controllable with biologic agents targeting TNF-alpha, IL 12/23, and IL-17. Etanercept has been approved for children with psoriasis aged 4 years and older, and other biologic agents are under study.

Atopic dermatitis now is ready for its revolution! AD has increased in prevalence from around 5% of the pediatric population 30-plus years ago to 10%-15%. Treatment of most individuals has remained the same over the decades: Good skin care, frequent moisturizers, topical corticosteroids for flares, management of infection if noted. The topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs) broadened the therapeutic approach when introduced in 2000 and 2001, but the boxed warning resulted in some practitioners minimizing their utilization of these useful agents.

It has been recognized for years that children with AD have higher risk of developing food allergies than children without AD. A changing understanding of how early food exposure may induce tolerance is changing the world of allergy and influencing the care of children with AD. This is where the peanut butter (or other processed peanut, such as “Bamba”) may be life saving. New guidelines have come from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases recommending that infants with severe eczema (or egg allergy, or both) have introduction of age-appropriate peanut-containing food as early as 4-6 months of age to reduce the risk of development of peanut allergy. It is recommended that these infants undergo early evaluation for possible sensitization to peanut protein, with referral to allergists for skin prick tests or serum IgE screens (though if positive, referral to allergists is appropriate), and assess the safety of going ahead with early feeding. It is hoped that following these new guidelines can minimize the development of peanut allergy.

The future

Where will pediatric skin disease, or more importantly, skin health over a lifetime be in 50 years? Can we cure or prevent the consequences of our lethal and life altering genetic diseases such as epidermolysis bullosa or our neurocutaneous disorders? Will our new insights into birthmarks (they are mostly somatic mutations) allow us to form specific, personalized therapies to minimize their impact? Will we be using computers equipped with imaging devices and algorithms to assess our patients’ moles, papules, and nodules? Will our vaccines have wiped out warts, molluscum, and perhaps, acne? Will we have cured our inflammatory skin disorders, or perhaps prevented them by interventions in the neonatal period? No predictions will be offered here, other than that we can look forward to incredible changes for our future generations of health care practitioners, patients, and families.

Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield has served as a consultant for Anacor/Pfizer and Regeneron/Sanofi. Email him at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

The world in pediatric dermatology has changed in incredible ways since 1967. In fact, pediatric dermatology was not an organized specialty until years later! This article will look back at some of the history of pediatric dermatology, exploring how different the field was 50 years ago, and how it has evolved into the vibrant field that it is. By looking at some disease states, and differences in practice in relation to the care of dermatologic conditions in children both by pediatricians and dermatologists, we can see the tremendous evolution in our understanding and management of pediatric skin conditions, and perhaps gain insight into the future.

Pediatric dermatology was fairly “neonatal” 50 years ago, with only a few practitioners in the field. Recognizing that up to 30% of pediatric primary care visits include a skin-related problem, and that there was limited training about skin diseases among primary care practitioners and inconsistent training amongst dermatologists, there was a clinical need for establishing the subspecialty of pediatric dermatology. The first international symposium was held in Mexico City in October 1972, and with this meeting the International Society of Pediatric Dermatology was founded. The Society for Pediatric Dermatology (SPD) began in 1973, with Alvin Jacobs, MD, Samuel Weinberg, MD, Nancy Esterly, MD, Sidney Hurwitz, MD, William Weston, MD, and Coleman Jacobson, MD, as some of the initial “founding mothers and fathers.” The journal Pediatric Dermatology released its first issue in 1982 (35 years ago), and the American Academy of Pediatrics did not have a section of dermatology until 1986.

Pediatrics and dermatology: The interface

Many of the first generation of pediatric dermatologists trained as pediatricians prior to pursuing their dermatology work, with some being “assigned” dermatology as pediatric experts, while others did formal residencies in dermatology. This history is important, as pediatric dermatology was, and remains, integrated with pediatrics, even while training in dermatology residencies became standard practice. An important part of the development of the field has been the education of pediatricians and dermatologists by pediatric dermatologists, with a strong sensibility that improved training for both generalists and specialists about pediatric skin disease would yield better care for patients and families.

Initially, there were very few pediatric or dermatology programs in the United States that had pediatric dermatologists. Over the succeeding decades, this is now less common, although even now there are still dermatology and pediatric residency programs that do not have a pediatric dermatologist for either training or to serve their patients. The founding leaders of the SPD set a tone of collaboration nationally and internationally, reaching out to pediatric colleagues and dermatology associates from around the world, and establishing superb educational programs for the exchange of ideas, presentation of challenging cases, and promoting state of the art knowledge of the field. Through annual meetings of the SPD, conferences immediately preceding the American Academy of Dermatology annual meetings, the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology, and other regional and international meetings, the field developed as the number of practitioners grew, and as the specialized published literature reflected new knowledge in diagnosis and therapy.

Building upon the history of collaboration and reflecting the maturation of the field with a desire to influence the breadth and quantity of research in pediatric dermatology, the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance (PeDRA) was formed in 2012. This organization was formed to promote and facilitate high quality collaborative clinical, translational, educational, and basic science research in pediatric dermatology with a vision to create sustainable, collaborative networks to better understand, prevent, treat, and cure dermatologic diseases in children. This network is now composed of over 230 members representing over 68 institutions from the United States and Canada, but including involvement globally from Mexico, Europe, and the Middle East.

Examples of changing perspectives: hemangiomas

A good way to look at evolution of the field is take a look at some of the similarities and differences in clinical practice in relation to common and uncommon disease states.

A great example is hemangiomas. Some of the first natural history studies on hemangiomas were done in the early 1960s, establishing that many lesions had a typical clinical course of fairly rapid growth, plateau, and involution over time. Of course, the identification of hemangiomas of infancy (or “HOI” in the trade), was confused with vascular malformations, and no one had recognized variant tumors that were distinct, such as rapidly involuting and noninvoluting congenital hemangiomas (RICHs or NICHs), tufted angiomas, and hemangioendotheliomas. PHACE syndrome (posterior fossa brain malformations) had yet to be described (that was done in 1996 by Ilona Frieden and her colleagues). For a time period, hemangiomas were treated with X-rays, before the negative impact of such radiation was acknowledged. For many years after that, even deforming and functionally significant lesions were “followed clinically” for natural involution, presumably a backlash from the radiation therapy interventions.

This story also reflects how organized research efforts helped with the evolution of knowledge and clinical care. The Hemangioma of Infancy Group was formed to take a collaborative approach to characterize and study hemangiomas and related tumors. Beginning with energetic, insightful pediatric dermatologists, and little funding, they changed our knowledge base of how hemangiomas present, the risk factors for their development and the characteristics and multiple organ findings associated with PHACE and other syndromic hemangiomas.

Procedural pediatric dermatology: Tremendous revolution in surgery and laser

The first generation of pediatric dermatologists were considered medical dermatologist specialists. And how important this specialty work was! Acne, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, diaper and seborrheic dermatitis, and rare genetic syndromes, these conditions were a major part of the work of early pediatric dermatologists (and remain so now). What was not common was for pediatric dermatologists to have procedural or surgical practices, while this now is routinely part of the work of specialists in the field. How did this shift occur?

The fundamental shift began to occur with the introduction of the pulsed dye laser in 1989 and the publication of a seminal article in the New England Journal of Medicine (1989 Feb 16;320[7]:416-21) on its utility in treating port-wine stains in children with minimal scarring. Vascular lesions including port-wine stains were common, and pediatric dermatologists managed these patients for both diagnosis and medical management. Also, dermatology residencies at this time offered training in cutaneous surgery, excisions (including Mohs surgery) and repairs, and trainees in pediatric dermatology were “trained up” to high levels of expertise. As lasers were incorporated into dermatology residency work and practices, pediatric dermatologists had the exposure and skill to do this work. An added advantage was having the pediatric knowledge of how to handle children and adolescents in an age appropriate manner, and consideration of methods to minimize the pain and anxiety of procedures. Within a few years, pediatric dermatologists were at the forefront of the use of topical anesthetics (EMLA and liposomal lidocaine) and had general anesthesia privileges for laser and excisional surgery.

So while pediatric dermatologists still do “small procedures” every hour in most practices (cryotherapy for warts, cantharidin for molluscum, shave and punch biopsies), a subset now have extensive procedural practices, which in recent years has extended to pigment lesion lasers (to treat nevus of Ota), hair lasers (to treat perineal areas to prevent pilonidal cyst recurrence or to treat hirsutism), and combinations of lasers to treat hypertrophic, constrictive, and/or deforming scars).

Inflammatory skin disorders: Bread and butter ... and peanut butter?

The care of pediatric inflammatory skin disorders has evolved, but more slowly for some diseases than others. Acne vulgaris now is recognized as much more common under age 12 years than previously, presumably reflecting earlier pubertal changes in our preteens. Over the past 30 years, therapy has evolved with the use of topical retinoids (still underused by pediatricians, considered a “practice gap”), hormonal therapy with combined oral contraceptives, and oral isotretinoin, a powerful but highly effective systemic agent for severe and refractory acne. Specific pediatric guidelines came much later. Pediatric acne expert recommendations were formulated by the American Acne and Rosacea Society and endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics in 2013 (Pediatrics. 2013;131:S163-86). Over the past few years, there is a push by experts for more judicious use of antibiotics for acne (oral and topical) to minimize the emergence of bacterial resistance.

Psoriasis has been a condition that has been “behind the revolution,” in that no biologic agent was approved for pediatric psoriasis in the United States until several months ago, lagging behind Europe and elsewhere in the world by almost a decade. Adult psoriasis has been recognized to be associated with a broad set of comorbidities, including obesity and early heart disease, and there is now research on how children are at risk as well, and new recommendations on how to screen children with psoriasis. Moderate to severe psoriasis in adults is now tremendously controllable with biologic agents targeting TNF-alpha, IL 12/23, and IL-17. Etanercept has been approved for children with psoriasis aged 4 years and older, and other biologic agents are under study.

Atopic dermatitis now is ready for its revolution! AD has increased in prevalence from around 5% of the pediatric population 30-plus years ago to 10%-15%. Treatment of most individuals has remained the same over the decades: Good skin care, frequent moisturizers, topical corticosteroids for flares, management of infection if noted. The topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs) broadened the therapeutic approach when introduced in 2000 and 2001, but the boxed warning resulted in some practitioners minimizing their utilization of these useful agents.

It has been recognized for years that children with AD have higher risk of developing food allergies than children without AD. A changing understanding of how early food exposure may induce tolerance is changing the world of allergy and influencing the care of children with AD. This is where the peanut butter (or other processed peanut, such as “Bamba”) may be life saving. New guidelines have come from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases recommending that infants with severe eczema (or egg allergy, or both) have introduction of age-appropriate peanut-containing food as early as 4-6 months of age to reduce the risk of development of peanut allergy. It is recommended that these infants undergo early evaluation for possible sensitization to peanut protein, with referral to allergists for skin prick tests or serum IgE screens (though if positive, referral to allergists is appropriate), and assess the safety of going ahead with early feeding. It is hoped that following these new guidelines can minimize the development of peanut allergy.

The future

Where will pediatric skin disease, or more importantly, skin health over a lifetime be in 50 years? Can we cure or prevent the consequences of our lethal and life altering genetic diseases such as epidermolysis bullosa or our neurocutaneous disorders? Will our new insights into birthmarks (they are mostly somatic mutations) allow us to form specific, personalized therapies to minimize their impact? Will we be using computers equipped with imaging devices and algorithms to assess our patients’ moles, papules, and nodules? Will our vaccines have wiped out warts, molluscum, and perhaps, acne? Will we have cured our inflammatory skin disorders, or perhaps prevented them by interventions in the neonatal period? No predictions will be offered here, other than that we can look forward to incredible changes for our future generations of health care practitioners, patients, and families.

Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield has served as a consultant for Anacor/Pfizer and Regeneron/Sanofi. Email him at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Status Report From the American Acne & Rosacea Society on Medical Management of Acne in Adult Women, Part 3: Oral Therapies

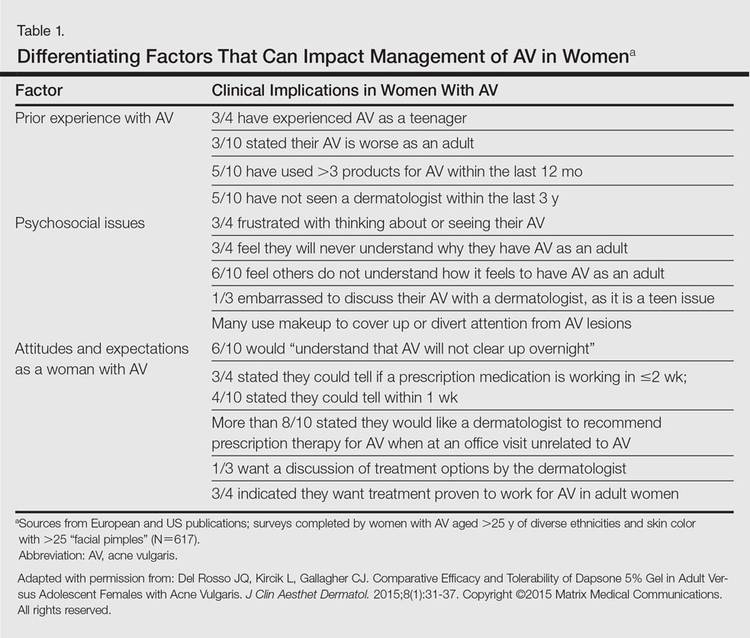

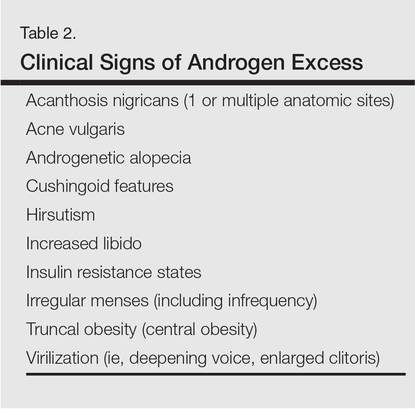

Selection of oral agents for treatment of AV in adult women is dependent on multiple factors including the patient’s age, medication history, child-bearing potential, clinical presentation, and treatment preference following a discussion of the anticipated benefits versus potential risks.1,2 In patients with the mixed inflammatory and comedonal clinical pattern of AV, oral antibiotics can be used concurrently with topical therapies when moderate to severe inflammatory lesions are noted.3,4 However, many adult women who had AV as teenagers have already utilized oral antibiotic therapies in the past and often are interested in alternative options, express concerns regarding antibiotic resistance, report a history of antibiotic-associated yeast infections or other side effects, and/or encounter issues related to drug-drug interactions.3,5-8 Oral hormonal therapies such as combination oral contraceptives (COCs) or spironolactone often are utilized to treat adult women with AV, sometimes in combination with each other or other agents. Combination oral contraceptives appear to be especially effective in the management of the U-shaped clinical pattern or predominantly inflammatory, late-onset AV.1,5,9,10 Potential warnings, contraindications, adverse effects, and drug-drug interactions are important to keep in mind when considering the use of oral hormonal therapies.8-10 Oral isotretinoin, which should be prescribed with strict adherence to the iPLEDGE™ program (https://www.ipledgeprogram.com/), remains a viable option for cases of severe nodular AV and selected cases of refractory inflammatory AV, especially when scarring and/or marked psychosocial distress are noted.1,2,5,11 Although it is recognized that adult women with AV typically present with either a mixed inflammatory and comedonal or U-shaped clinical pattern predominantly involving the lower face and anterolateral neck, the available data do not adequately differentiate the relative responsiveness of these clinical patterns to specific therapeutic agents.

Combination Oral Contraceptives

Combination oral contraceptives are commonly used to treat AV in adult women, including those without and those with measurable androgen excess (eg, polycystic ovary syndrome [PCOS]). Combination oral contraceptives contain ethinyl estradiol and a progestational agent (eg, progestin); the latter varies in terms of its nonselective receptor interactions and the relative magnitude or absence of androgenic effects.10,12,13 Although some COCs are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for AV, there is little data available to determine the comparative efficacy among these and other COCs.10,14 When choosing a COC for treatment of AV, it is best to select an agent whose effectiveness is supported by evidence from clinical studies.10,15

Mechanisms of Action

The reported mechanisms of action for COCs include inhibition of ovarian androgen production and ovulation through gonadotropin suppression; upregulated synthesis of sex hormone–binding globulin, which decreases free testosterone levels through receptor binding; and inhibition of 5α-reductase (by some progestins), which reduces conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone, the active derivative that induces androgenic effects at peripheral target tissues.10,13,16,17

Therapeutic Benefits

Use of COCs to treat AV in adult women who do not have measurable androgen excess is most rational in patients who also desire a method of contraception. Multiple monotherapy studies have demonstrated the efficacy of COCs in the treatment of AV on the face and trunk.4,10,12,15,17,18 It may take a minimum of 3 monthly cycles of use before acne lesion counts begin to appreciably decrease.12,15,19-21 Initiating COC therapy during menstruation ensures the absence of pregnancy. Combination oral contraceptives may be used with other topical and oral therapies for AV.2,3,9,10 Potential ancillary benefits of COCs include normalization of the menstrual cycle; reduced premenstrual dysphoric disorder symptoms; and reduced risk of endometrial cancer (approximately 50%), ovarian cancer (approximately 40%), and colorectal cancer.22-24

Risks and Contraindications

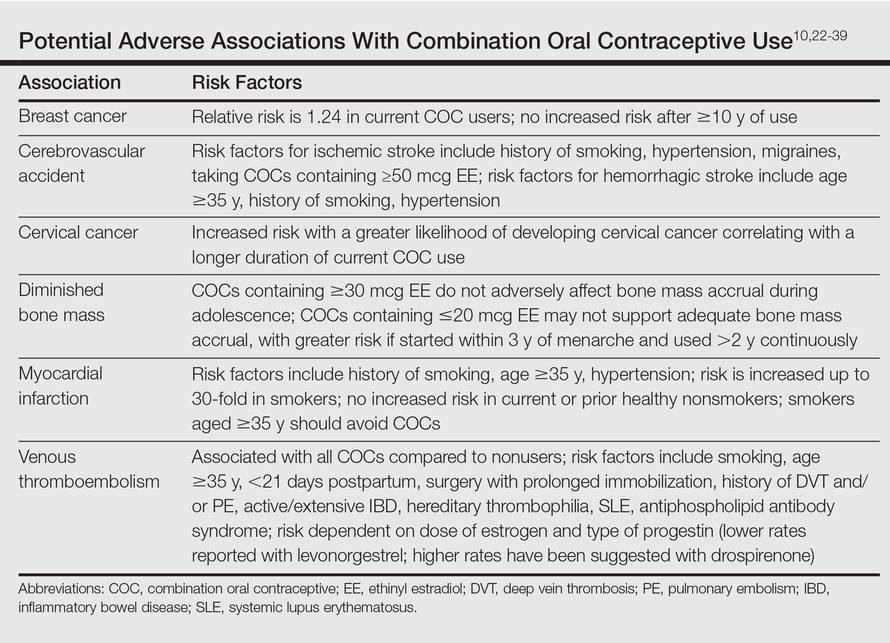

It is important to consider the potential risks associated with the use of COCs, especially in women with AV who are not seeking a method of contraception. Side effects of COCs can include nausea, breast tenderness, breakthrough bleeding, and weight gain.25,26 Potential adverse associations of COCs are described in the Table. The major potential vascular associations include venous thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, and cerebrovascular accident, all of which are influenced by concurrent factors such as a history of smoking, age (≥35 years), and hypertension.27-32 It is recommended that blood pressure be measured before initiating COC therapy as part of the general examination.33

The potential increase in breast cancer risk appears to be low, while the cervical cancer risk is reported to increase relative to the duration of use.34-37 This latter observation may be due to the greater likelihood of unprotected sex in women using a COC and exposure to multiple sexual partners in some cases, which may increase the likelihood of oncogenic human papillomavirus infection of the cervix. If a dermatologist elects to prescribe a COC to treat AV, it has been suggested that the patient also consult with her general practitioner or gynecologist to undergo pelvic and breast examinations and a Papanicolaou test.33 The recommendation for initial screening for cervical cancer is within 3 years of initiation of sexual intercourse or by 21 years of age, whichever is first.33,38,39

Combination oral contraceptives are not ideal for all adult women with AV. Absolute contraindications are pregnancy and history of thromboembolic, cardiac, or hepatic disease; in women aged 35 years and older who smoke, relative contraindications include hypertension, diabetes, migraines, breastfeeding, and current breast or liver cancer.33 In adult women with AV who have relative contra-indications but are likely to benefit from the use of a COC when other options are limited or not viable, consultation with a gynecologist is prudent. Other than rifamycin antibiotics (eg, rifampin) and griseofulvin, there is no definitive evidence that oral antibiotics (eg, tetracycline) or oral antifungal agents reduce the contraceptive efficacy of COCs, although cautions remain in print within some approved package inserts.8

Spironolactone

Available since 1957, spironolactone is an oral aldos-terone antagonist and potassium-sparing diuretic used to treat hypertension and congestive heart failure.9 Recognition of its antiandrogenic effects led to its use in dermatology to treat certain dermatologic disorders in women (eg, hirsutism, alopecia, AV).1,4,5,9,10 Spironolactone is not approved for AV by the FDA; therefore, available data from multiple independent studies and retrospective analyses that have been collectively reviewed support its efficacy when used as both monotherapy or in combination with other agents in adult women with AV, especially those with a U-shaped pattern and/or late-onset AV.9,40-43

Mechanism of Action

Spironolactone inhibits sebaceous gland activity through peripheral androgen receptor blockade, inhibition of 5α-reductase, decrease in androgen production, and increase in sex hormone–binding globulin.9,10,40

Therapeutic Benefits

Good to excellent improvement of AV in women, many of whom are postadolescent, has ranged from 66% to 100% in published reports9,40-43; however, inclusion and exclusion criteria, dosing regimens, and concomitant therapies were not usually controlled. Spironolactone has been used to treat AV in adult women as monotherapy or in combination with topical agents, oral antibiotics, and COCs.9,40-42 Additionally, dose-ranging studies have not been completed with spironolactone for AV.9,40 The suggested dose range is 50 mg to 200 mg daily; however, it usually is best to start at 50 mg daily and increase to 100 mg daily if clinical response is not adequate after 2 to 3 months. The gastrointestinal (GI) absorption of spironolactone is increased when ingested with a high-fat meal.9,10

Once effective control of AV is achieved, it is optimal to use the lowest dose needed to continue reasonable suppression of new AV lesions. There is no defined end point for spironolactone use in AV, with or without concurrent PCOS, as many adult women usually continue treatment with low-dose therapy because they experience marked flaring shortly after the drug is stopped.9

Risks and Contraindications

Side effects associated with spironolactone are dose related and include increased diuresis, migraines, menstrual irregularities, breast tenderness, gynecomastia, fatigue, and dizziness.9,10,40-44 Side effects (particularly menstrual irregularities and breast tenderness) are more common at doses higher than 100 mg daily, especially when used as monotherapy without concurrent use of a COC.9,40

Spironolactone-associated hyperkalemia is most clinically relevant in patients on higher doses (eg, 100–200 mg daily), in those with renal impairment and/or congestive heart failure, and when used concurrently with certain other medications. In any patient on spironolactone, the risk of clinically relevant hyperkalemia may be increased by coingestion of potassium supplements, potassium-based salt substitutes, potassium-sparing diuretics (eg, amiloride, triamterene); aldosterone antagonists and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (eg, lisinopril, benazepril); angiotensin II receptor blockers (eg, losartan, valsartan); and tri-methoprim (with or without sulfamethoxazole).8,9,40,45 Spironolactone may also increase serum levels of lithium or digoxin.9,40,45,46 For management of AV, it is best that spironolactone be avoided in patients taking any of these medications.9

In healthy adult women with AV who are not on medications or supplements that interact adversely with spironolactone, there is no definitive recommendation regarding monitoring of serum potassium levels during treatment with spironolactone, and it has been suggested that monitoring serum potassium levels in this subgroup is not necessary.47 However, each clinician is advised to choose whether or not they wish to obtain baseline and/or periodic serum potassium levels when prescribing spironolactone for AV based on their degree of comfort and the patient’s history. Baseline and periodic blood testing to evaluate serum electrolytes and renal function are reasonable, especially as adult women with AV are usually treated with spironolactone over a prolonged period of time.9

The FDA black box warning for spironolactone states that it is tumorigenic in chronic toxicity studies in rats and refers to exposures 25- to 100-fold higher than those administered to humans.9,48 Although continued vigilance is warranted, evaluation of large populations of women treated with spironolactone do not suggest an association with increased risk of breast cancer.49,50

Spironolactone is a category C drug and thus should be avoided during pregnancy, primarily due to animal data suggesting risks of hypospadias and feminization in male fetuses.9 Importantly, there is an absence of reports linking exposure during pregnancy with congenital defects in humans, including in 2 known cases of high-dose exposures for maternal Bartter syndrome.9

The active metabolite, canrenone, is known to be present in breast milk at 0.2% of the maternal daily dose, but breastfeeding is generally believed to be safe with spironolactone based on evidence to date.9

Oral Antibiotics

Oral antibiotic therapy may be used in combination with a topical regimen to treat AV in adult women, keeping in mind some important caveats.1-7 For instance, monotherapy with oral antibiotics should be avoided, and concomitant use of benzoyl peroxide is suggested to reduce emergence of antibiotic-resistant Propionibacterium acnes strains.3,4 A therapeutic exit plan also is suggested when prescribing oral antibiotics to limit treatment to 3 to 4 months, if possible, to help mitigate the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria (eg, staphylococci and streptococci).3-5,51

Tetracyclines, especially doxycycline and minocycline, are the most commonly prescribed agents. Doxycycline use warrants patient education on measures to limit the risks of esophageal and GI side effects and phototoxicity; enteric-coated and small tablet formulations have been shown to reduce GI side effects, especially when administered with food.3,52-55 In addition to vestibular side effects and hyperpigmentation, minocycline may be associated with rare but potentially severe adverse reactions such as drug hypersensitivity syndrome, autoimmune hepatitis, and lupus-like syndrome, which are reported more commonly in women.5,52,54 Vestibular side effects have been shown to decrease with use of extended-release tablets with weight-based dosing.53

Oral Isotretinoin

Oral isotretinoin is well established as highly effective for treatment of severe, recalcitrant AV, including nodular acne on the face and trunk.4,56 Currently available oral isotretinoins are branded generic formulations based on the pharmacokinetic profile of the original brand (Accutane [Roche Pharmaceuticals]) and with the use of Lidose Technology (Absorica [Cipher Pharmaceuticals]), which substantially increases GI absorption of isotretinoin in the absence of ingestion with a high-calorie, high-fat meal.57 The short- and long-term efficacy, dosing regimens, safety considerations, and serious teratogenic risks for oral isotretinoin are well published.4,56-58 Importantly, oral isotretinoin must be prescribed with strict adherence to the federally mandated iPLEDGE risk management program.

Low-dose oral isotretinoin therapy (<0.5 mg/kg–1 mg/kg daily) administered over several months longer than conventional regimens (ie, 16–20 weeks) has been suggested with demonstrated efficacy.57 However, this approach is not optimal due to the lack of established sustained clearance of AV after discontinuation of therapy and the greater potential for exposure to isotretinoin during pregnancy. Recurrences of AV do occur after completion of isotretinoin therapy, especially if cumulative systemic exposure to the drug during the initial course of treatment was inadequate.56,57

Oral isotretinoin has been shown to be effective in AV in adult women with or without PCOS with 0.5 mg/kg to 1 mg/kg daily and a total cumulative exposure of 120 mg/kg to 150 mg/kg.59 In one study, the presence of PCOS and greater number of nodules at baseline were predictive of a higher risk of relapse during the second year posttreatment.59

Conclusion

All oral therapies that are used to treat AV in adult women warrant individual consideration of possible benefits versus risks. Careful attention to possible side effects, patient-related risk factors, and potential drug-drug interactions is important. End points of therapy are not well established, with the exception of oral isotretinoin therapy. Clinicians must use their judgment in each case along with obtaining feedback from patients regarding the selection of therapy after a discussion of the available options.

- Holzmann R, Shakery K. Postadolescent acne in females. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2014;27(suppl 1):3-8.

- Villasenor J, Berson DS, Kroshinsky D. Treatment guidelines in adult women. In: Shalita AR, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, eds. Acne Vulgaris. London, United Kingdom: Informa Healthcare; 2011:198-207.

- Del Rosso JQ, Kim G. Optimizing use of oral antibiotics in acne vulgaris. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:33-42.

- Gollnick H, Cunliffe W, Berson D, et al. Management of acne: report from a Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(suppl 1):S1-S37.

- Fisk WA, Lev-Tov HA, Sivamani RK. Epidemiology and management of acne in adult women. Curr Derm Rep. 2014;3:29-39.

- Del Rosso JQ, Leyden JJ. Status report on antibiotic resistance: implications for the dermatologist. Dermatol Clin. 2007;25:127-132.

- Bowe WP, Leyden JJ. Clinical implications of antibiotic resistance: risk of systemic infection from Staphylococcus and Streptococcus. In: Shalita AR, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, eds. Acne Vulgaris. London, United Kingdom: Informa Healthcare; 2011:125-133.

- Del Rosso JQ. Oral antibiotic drug interactions of clinical significance to dermatologists. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:91-94.

- Kim GK, Del Rosso JQ. Oral spironolactone in post-teenage female patients with acne vulgaris: practical considerations for the clinician based on current data and clinical experience. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:37-50.

- Keri J, Berson DS, Thiboutot DM. Hormonal treatment of acne in women. In: Shalita AR, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF, eds. Acne Vulgaris. London, United Kingdom: Informa Healthcare; 2011:146-155.

- American Academy of Dermatology. Position statement on isotretinoin. AAD Web site. https://www.aad.org /Forms/Policies/Uploads/PS/PS-Isotretinoin.pdf. Updated November 13, 2010. Accessed October 28, 2015.

- Arowojolu AO, Gallo MF, Lopez LM, et al. Combined oral contraceptive pills for treatment of acne. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. June 2012;7:CD004425.

- Sitruk-Ware R. Pharmacology of different progestogens: the special case of drospirenone. Climacteric. 2005;8 (suppl 3):4-12.

- Arowojolu AO, Gallo MF, Lopez LM, et al. Combined oral contraceptive pills for the treatment of acne. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. July 2012;7:CD004425.

- Thiboutot D, Archer DF, Lemay A, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of a low-dose contraceptive containing 20 microg of ethinyl estradiol and 100 microg of levonogestrel for acne treatment. Fertil Steril. 2001;76:461-468.

- Koulianos GT. Treatment of acne with oral contraceptives: criteria for pill selection. Cutis. 2000;66:281-286.

- Rabe T, Kowald A, Ortmann J, et al. Inhibition of skin 5-alpha reductase by oral contraceptive progestins in vitro. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2000;14:223-230.

- Palli MB, Reyes-Habito CM, Lima XT, et al. A single-center, randomized double-blind, parallel-group study to examine the safety and efficacy of 3mg drospirenone/0.02mg ethinyl estradiol compared with placebo in the treatment of moderate truncal acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:633-637.

- Koltun W, Maloney JM, Marr J, et al. Treatment of moderate acne vulgaris using a combined oral contraceptive containing ethinylestradiol 20 μg plus drospirenone 3 mg administered in a 24/4 regimen: a pooled analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;155:171-175.

- Maloney JM, Dietze P, Watson D, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a low-dose combined oral contraceptive containing 3 mg drospirenone plus 20 μg ethinylestradiol in the treatment of acne vulgaris: lesion counts, investigator ratings and subject self-assessment. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:837-844.

- Lucky AW, Koltun W, Thiboutot D, et al. A combined oral contraceptive containing 3-mg drospirenone/20-μg ethinyl estradiol in the treatment of acne vulgaris: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study evaluating lesion counts and participant self-assessment. Cutis. 2008;82:143-150.

- Burkman R, Schlesselman JJ, Zieman M. Safety concerns and health benefits associated with oral contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(suppl 4):S5-S22.

- Maguire K, Westhoff C. The state of hormonal contraception today: established and emerging noncontraceptive health benefits. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205 (suppl 4):S4-S8.

- Weiss NS, Sayvetz TA. Incidence of endometrial cancer in relation to the use of oral contraceptives. N Engl J Med. 1980;302:551-554.

- Tyler KH, Zirwas MJ. Contraception and the dermatologist. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:1022-1029.

- Gallo MF, Lopez LM, Grimes DA, et al. Combination contraceptives: effects on weight. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;4:CD003987.

- de Bastos M, Stegeman BH, Rosendaal FR, et al. Combined oral contraceptives: venous thrombosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;3:CD010813.

- Raymond EG, Burke AE, Espey E. Combined hormonal contraceptives and venous thromboembolism: putting the risks into perspective. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:1039-1044.

- Jick SS, Hernandez RK. Risk of non-fatal venous thromboembolism in women using oral contraceptives containing drospirenone compared with women using oral contraceptives containing levonorgestrel: case-control study using United States claims data. BMJ. 2011;342:d2151.

- US Food and Drug Administration Office of Surveillance and Epidemiology. Combined hormonal contraceptives (CHCs) and the risk of cardiovascular disease endpoints. US Food and Drug Administration Web site. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs /Drug Safety/UCM277384.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2015.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Gynecologic Practice. Risk of venous thromboembolism among users of drospirenone-containing oral contraceptive pills. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:1239-1242.

- World Health Organization. Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception: Report of a WHO Scientific Group. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1998. Technical Report Series 877.

- Frangos JE, Alavian CN, Kimball AB. Acne and oral contraceptives: update on women’s health screening guidelines. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:781-786.

- Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Breast cancer and hormonal contraceptives: collaborative reanalysis of individual data on 53 297 women with breast cancer and 100 239 women without breast cancer from 54 epidemiological studies. Lancet. 1996;347:1713-1727.

- Gierisch JM, Coeytaux RR, Urrutia RP, et al. Oral contraceptive use and risk of breast, cervical, colorectal, and endometrial cancers: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:1931-1943.

- International Collaboration of Epidemiological Studies of Cervical Cancer. Cervical cancer and hormonal contraceptives: collaborative reanalysis of individual data for 16 573 women with cervical cancer and 35 509 women without cervical cancer from 24 epidemiological studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1609-1621.

- Agostino H, Di Meglio G. Low-dose oral contraceptives in adolescents: how low can you go? J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2010;23:195-201.

- Buzney E, Sheu J, Buzney C, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome: a review for dermatologists: part II. Treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:859.e1-859.e15.

- Stewart FH, Harper CC, Ellertson CE, et al. Clinical breast and pelvic examination requirements for hormonal contraception: current practice vs evidence. JAMA. 2001;285:2232-2239.

- Sawaya ME, Somani N. Antiandrogens and androgen inhibitors. In: Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. Philadelpha, PA: Saunders; 2013:361-374.

- Muhlemann MF, Carter GD, Cream JJ, et al. Oral spironolactone: an effective treatment for acne vulgaris in women. Br J Dermatol. 1986;115:227-232.

- Shaw JC. Low-dose adjunctive spironolactone in the treatment of acne in women: a retrospective analysis of 85 consecutively treated patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:498-502.

- Sato K, Matsumoto D, Iizuka F, et al. Anti-androgenic therapy using oral spironolactone for acne vulgaris in Asians. Aesth Plast Surg. 2006;30:689-694.

- Shaw JC, White LE. Long-term safety of spironolactone in acne: results of an 8-year follow-up study. J Cutan Med Surg. 2002;6:541-545.

- Stockley I. Antihypertensive drug interactions. In: Stockley I, ed. Drug Interactions. 5th ed. London, United Kingdom: Pharmaceutical Press; 1999:335-347.

- Antoniou T, Gomes T, Mamdani MM, et al. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole induced hyperkalaemia in elderly patients receiving spironolactone: nested case-control study. BMJ. 2011;343:d5228.

- Plovanich M, Weng QY, Mostaghimi A. Low usefulness of potassium monitoring among healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:941-944.

- Aldactone [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer Inc; 2008.

- Biggar RJ, Andersen EW, Wohlfahrt J, et al. Spironolactone use and the risk of breast and gynecologic cancers. Cancer Epidemiol. 2013;37:870-875.

- Mackenzie IS, Macdonald TM, Thompson A, et al. Spironolactone and risk of incident breast cancer in women older than 55 years: retrospective, matched cohort study. BMJ. 2012;345:e4447.

- Dreno B, Thiboutot D, Gollnick H, et al. Antibiotic stewardship in dermatology: limiting antibiotic use in acne. Eur J Dermatol. 2014;24:330-334.

- Kim S, Michaels BD, Kim GK, et al. Systemic antibacterial agents. In: Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. Philadelpha, PA: Saunders; 2013:61-97.