User login

Atopic Dermatitis: Evolution and Revolution in Therapy

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is an incredibly common chronic skin disease, affecting up to 25% of children and 7% of adults in the United States.1,2 Despite the prevalence of this disease and its impact on patient quality of life, research and scholarly work in AD has been limited until recent years. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term atopic dermatitis showed that there were fewer than 500 articles published in 2000 and 965 in 2010; with our more recent acceleration in research, there were 2168 articles published in 2020 and more than 1300 published in just the first half of 2021 (through June). This new research includes insights into the pathogenesis of AD and study of the disease impact and comorbidities as well as an extensive amount of drug development and clinical trial work for new topical and systemic therapies.

New Agents to Treat AD

The 2016 approval of crisaborole,3 a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, followed by the approval of dupilumab, an IL-4 and IL-13 pathway inhibitor and the first biologic agent approved for AD,4 ushered in a new age of therapy. We currently are awaiting the incorporation of a new set of topical nonsteroidal agents, oral Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, and new biologic agents for AD, several of which have completed phase 3 trials and extended safety evaluations. How these new drugs will impact our standard treatment across the spectrum of care for AD is not yet known.

The emergence of new systemic therapies is timely, as the most used systemic medications previously were oral corticosteroids, despite their use being advised against in standard practice guidelines. Other agents such as methotrexate, cyclosporine, azathioprine, and mycophenolate are discussed in the literature and AD treatment guidelines as being potentially useful, though absence of US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval and the need for frequent laboratory monitoring, as well as drug-specific side effects and an increased risk of infection, limit their use in the United States, especially in pediatric and adolescent populations.5

The approval of dupilumab as a systemic therapy—initially for adults and subsequently for teenagers (12–17 years of age) and then children (6–11 years of age)—has markedly influenced the standard of care for moderate to severe AD. This agent has been shown to have a considerable impact on disease severity and quality of life, with a good safety profile and the added benefit of not requiring continuous (or any) laboratory monitoring.6-8 Ongoing studies of dupilumab in children (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers NCT02612454, NCT03346434), including those younger than 1 year,9 raise the question of how commonly this medication might be incorporated into care across the entire age spectrum of patients with AD. What standards will there be for assessment of severity, disease impact, and persistence to warrant use in younger ages? Will early treatment with novel systemic agents change the overall course of the disease and minimize the development of comorbidities? The answers to these questions remain to be seen.

JAK Inhibitors for AD

Additional novel therapeutics currently are undergoing studies for treatment of AD, most notably the oral JAK inhibitors upadacitinib,10 baricitinib,11 and abrocitinib.12 Each of these agents has completed phase 3 trials for AD. Two of these agents—upadacitinib and baricitinib—have prior FDA approval for use in other disease states. Of note, baricitinib is already approved for treatment of moderate to severe AD in adults in more than 40 countries13; however, the use of these agents in other diseases brings about concerns of malignancy, severe infection, and thrombosis. In the clinical trials for AD, many of these events have not been seen, but the number of patients treated is limited, and longer-term safety assessment is important.10,11

How will the oral JAK inhibitors be incorporated into care compared to biologic agents such as dupilumab? Tolerance and more serious potential adverse events are concerns, with nausea, headaches, and acneform eruptions being associated with some of the medications, in addition to potential issues with herpes simplex and zoster infections. However, oral JAK inhibitors have the benefit of not requiring injections, something that many patients may prefer, and data show that these drugs generally are associated with a rapid reduction in pruritus and, depending on the drug, very quick and profound effects on objective signs of AD.10-12 Two head-to-head studies have been completed comparing dupilumab to oral JAK inhibitors in adults: the JADE COMPARE trial examining dupilumab vs abrocitinib12 and the Heads UP trial comparing dupilumab vs upadacitinib.14 Compared to dupilumab, higher-dose abrocitinib showed more rapid responses, superiority in itch response, and similarity or superiority in other outcomes depending on the time point of the evaluation. Adverse event profiles differed; for example, abrocitinib was associated with more nausea, acneform eruptions, and herpes zoster, while dupilumab had higher rates of conjunctivitis.12 Upadacitinib, which was only studied at higher dosing (30 mg daily), showed superiority to dupilumab in itch response and in improvement in AD severity in multiple outcome measures; however, there were increases in serious infections, eczema herpeticum, herpes zoster, and laboratory-related adverse events.14 Dupilumab has the advantage of studies of extended use along with real-world experience, generally with excellent safety and tolerance other than injection-site reactions and conjunctivitis.8 Biologics targeting IL-13—tralokinumab and lebrikizumab—also are to be added to our armamentarium.15,16 The addition of these agents and JAK inhibitors as new systemic treatment options points to the quickly evolving future of AD treatment for patients with extensive disease.

New topical therapies in development provide even more treatment options. New nonsteroidal topicals include topical JAK inhibitors such as ruxolitinib17; tapinarof,18 an aryl hydrocarbon receptor modulator; and phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors. These agents may be useful either as monotherapy, as studied, potentially without the regional limitations associated with stronger topical corticosteroids, but also should be useful in clinical practice as part of therapeutic regimens with other topical steroid and nonsteroidal agents.

The Microbiome and AD

In addition, research looking at topical microbes as specific interventions that may mediate the microbiome and inflammation of AD are intriguing. A recent phase 1 trial from the University of California San Diego19 indicated that topical bacteriotherapy directed at decreasing Staphylococcus aureus may provide an impact in AD. Observations by Kong et al20 showed that gram-negative microbiome differences are seen in AD patients compared to unaffected individuals, which has fueled studies showing that Roseomonas mucosa, a gram-negative skin commensal, when applied as a topical live biotherapeutic agent has improved disease severity in children and adults with AD.21 Although further studies are underway, these initial data suggest a role for microbiome-modifying therapies as AD treatment.

Chronic Hand Eczema

Chronic hand eczema (CHE), which has considerable overlap with AD in many patients, especially children and adolescents,22-24 is another area of interesting research. This high-prevalence condition is associated with allergic and irritant contact dermatitis24-26—conditions that are both considered alternative diagnoses for and exacerbators of AD27—and is a disease process currently being targeted for new therapies. Delgocitinib (NCT04872101, NCT04871711), the novel JAK inhibitor ARQ-252 (NCT04378569), among other topical agents, as well as systemic therapeutics such as gusacitinib (NCT03728504), are in active trials for CHE. Given CHE’s impact on quality of life28 and its overlap with AD, investigation into this disorder can help drive future AD research as well as lead to better knowledge and treatment of CHE.

Final Thoughts

Despite the promising results of these myriad new therapies in AD, there are many factors that influence how and when we use these drugs, including their approval status, FDA labeling, and the ability of patients to access and afford treatment. Additionally, continued study is needed to evaluate the long-term safety and extended efficacy of newer drugs, such as the oral JAK inhibitors. Despite these hurdles, the current landscape of research and development is rapidly evolving. Compared to the many years when only one main group of therapies was a reasonable option for patients, the future of AD treatment looks bright.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Chamlin SL, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 1. diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:338-351. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.10.010

- Chiesa Fuxench ZC, Block JK, Boguniewicz M, et al. Atopic dermatitis in America study: a cross-sectional study examining the prevalence and disease burden of atopic dermatitis in the US adult population. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:583-590. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2018.08.028

- FDA approves Eucrisa for eczema. News release. US Food and Drug Administration; December 14, 2016. Accessed August 16, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-eucrisa-eczema

- Gooderham MJ, Hong HC, Eshtiaghi P, et al. Dupilumab: a review of its use in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(3 suppl 1):S28-S36. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.12.022

- Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 3. management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:327-349. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.030

- Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Thaçi D, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab with concomitant topical corticosteroids in children 6 to 11 years old with severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1282-1293. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.054

- Simpson EL, Paller AS, Siegfried EC, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adolescents with uncontrolled moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:44-56. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3336

- Deleuran M, Thaçi D, Beck LA, et al. Dupilumab shows long-term safety and efficacy in patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis enrolled in a phase 3 open-label extension study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:377-388. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.07.074

- Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Simpson EL, et al. A phase 2, open-label study of single-dose dupilumab in children aged 6 months to <6 years with severe uncontrolled atopic dermatitis: pharmacokinetics, safety and efficacy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:464-475. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16928

- Reich K, Teixeira HD, de Bruin-Weller M, et al. Safety and efficacy of upadacitinib in combination with topical corticosteroids in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD Up): results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;397:2169-2181. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00589-4

- Simpson EL, Forman S, Silverberg JI, et al. Baricitinib in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from a randomized monotherapy phase 3 trial in the United States and Canada (BREEZE-AD5). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:62-70. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.02.028

- Bieber T, Simpson EL, Silverberg JI, et al. Abrocitinib versus placebo or dupilumab for atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1101-1112. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2019380

- Lilly and Incyte provide update on supplemental New Drug Application for baricitinib for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. News release. Eli Lilly and Company; July 16, 2021. Accessed August 16, 2021. https://investor.lilly.com/news-releases/news-release-details/lilly-and-incyte-provide-update-supplemental new-drug

- Blauvelt A, Teixeira HD, Simpson EL, et al. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib vs dupilumab in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized clinical trial [published online August 4, 2021]. JAMA Dermatol. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.3023

- Guttman-Yassky E, Blauvelt A, Eichenfield LF, et al. Efficacy and safety of lebrikizumab, a high-affinity interleukin 13 inhibitor, in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 2b randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:411-420. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0079

- Silverberg JI, Toth D, Bieber T, et al. Tralokinumab plus topical corticosteroids for the treatment of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from the double-blind, randomized, multicentre,placebo-controlled phase III ECZTRA 3 trial. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184:450-463. doi:10.1111/bjd.19573

- Papp K, Szepietowski JC, Kircik L, et al. Efficacy and safety of ruxolitinib cream for the treatment of atopic dermatitis: results from 2 phase 3, randomized, double-blind studies [published online May 4, 2021]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.04.085

- Paller AS, Stein Gold L, Soung J, et al. Efficacy and patient-reported outcomes from a phase 2b, randomized clinical trial of tapinarof cream for the treatment of adolescents and adults with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:632-638. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.135

- Nakatsuji, T, Hata TR, Tong Y, et al. Development of a human skin commensal microbe for bacteriotherapy of atopic dermatitis and use in a phase 1 randomized clinical trial [published online February 22, 2021]. Nat Med. 2021;27:700-709. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01256-2

- Kong HH, Oh J, Deming C, et al. Temporal shifts in the skin microbiome associated with disease flares and treatment in children with atopic dermatitis. Genome Res. 2012;22:850-859. doi:10.1101/gr.131029.111

- Myles IA, Castillo CR, Barbian KD, et al. Therapeutic responses to Roseomonas mucosa in atopic dermatitis may involve lipid-mediated TNF-related epithelial repair. Sci Transl Med. 2020;12:eaaz8631. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aaz8631

- Mortz CG, Lauritsen JM, Bindslev-Jensen C, et al. Prevalence of atopic dermatitis, asthma, allergic rhinitis, and hand and contact dermatitis in adolescents. The Odense Adolescence Cohort Study on Atopic Diseases and Dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:523-532. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04078.x

- Grönhagen C, Lidén C, Wahlgren CF, et al. Hand eczema and atopic dermatitis in adolescents: a prospective cohort study from the BAMSE project. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:1175-1182. doi:10.1111/bjd.14019

- Mortz CG, Lauritsen JM, Bindslev-Jensen C, et al. Contact allergy and allergic contact dermatitis in adolescents: prevalence measures and associations. The Odense Adolescence Cohort Study on Atopic Diseases and Dermatitis (TOACS). Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:352-358. doi:10.1080/000155502320624087

- Isaksson M, Olhardt S, Rådehed J, et al. Children with atopic dermatitis should always be patch-tested if they have hand or foot dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:583-586. doi:10.2340/00015555-1995

- Silverberg JI, Warshaw EM, Maibach HI, et al. Hand eczema in children referred for patch testing: North American Contact Dermatitis Group Data, 2000-2016. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:185-194. doi:10.1111/bjd.19818

- Agner T, Elsner P. Hand eczema: epidemiology, prognosis and prevention. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(suppl 1):4-12. doi:10.1111/jdv.16061

- Cazzaniga S, Ballmer-Weber BK, Gräni N, et al. Medical, psychological and socio-economic implications of chronic hand eczema: a cross-sectional study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:628-637. doi:10.1111/jdv.13479

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is an incredibly common chronic skin disease, affecting up to 25% of children and 7% of adults in the United States.1,2 Despite the prevalence of this disease and its impact on patient quality of life, research and scholarly work in AD has been limited until recent years. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term atopic dermatitis showed that there were fewer than 500 articles published in 2000 and 965 in 2010; with our more recent acceleration in research, there were 2168 articles published in 2020 and more than 1300 published in just the first half of 2021 (through June). This new research includes insights into the pathogenesis of AD and study of the disease impact and comorbidities as well as an extensive amount of drug development and clinical trial work for new topical and systemic therapies.

New Agents to Treat AD

The 2016 approval of crisaborole,3 a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, followed by the approval of dupilumab, an IL-4 and IL-13 pathway inhibitor and the first biologic agent approved for AD,4 ushered in a new age of therapy. We currently are awaiting the incorporation of a new set of topical nonsteroidal agents, oral Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, and new biologic agents for AD, several of which have completed phase 3 trials and extended safety evaluations. How these new drugs will impact our standard treatment across the spectrum of care for AD is not yet known.

The emergence of new systemic therapies is timely, as the most used systemic medications previously were oral corticosteroids, despite their use being advised against in standard practice guidelines. Other agents such as methotrexate, cyclosporine, azathioprine, and mycophenolate are discussed in the literature and AD treatment guidelines as being potentially useful, though absence of US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval and the need for frequent laboratory monitoring, as well as drug-specific side effects and an increased risk of infection, limit their use in the United States, especially in pediatric and adolescent populations.5

The approval of dupilumab as a systemic therapy—initially for adults and subsequently for teenagers (12–17 years of age) and then children (6–11 years of age)—has markedly influenced the standard of care for moderate to severe AD. This agent has been shown to have a considerable impact on disease severity and quality of life, with a good safety profile and the added benefit of not requiring continuous (or any) laboratory monitoring.6-8 Ongoing studies of dupilumab in children (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers NCT02612454, NCT03346434), including those younger than 1 year,9 raise the question of how commonly this medication might be incorporated into care across the entire age spectrum of patients with AD. What standards will there be for assessment of severity, disease impact, and persistence to warrant use in younger ages? Will early treatment with novel systemic agents change the overall course of the disease and minimize the development of comorbidities? The answers to these questions remain to be seen.

JAK Inhibitors for AD

Additional novel therapeutics currently are undergoing studies for treatment of AD, most notably the oral JAK inhibitors upadacitinib,10 baricitinib,11 and abrocitinib.12 Each of these agents has completed phase 3 trials for AD. Two of these agents—upadacitinib and baricitinib—have prior FDA approval for use in other disease states. Of note, baricitinib is already approved for treatment of moderate to severe AD in adults in more than 40 countries13; however, the use of these agents in other diseases brings about concerns of malignancy, severe infection, and thrombosis. In the clinical trials for AD, many of these events have not been seen, but the number of patients treated is limited, and longer-term safety assessment is important.10,11

How will the oral JAK inhibitors be incorporated into care compared to biologic agents such as dupilumab? Tolerance and more serious potential adverse events are concerns, with nausea, headaches, and acneform eruptions being associated with some of the medications, in addition to potential issues with herpes simplex and zoster infections. However, oral JAK inhibitors have the benefit of not requiring injections, something that many patients may prefer, and data show that these drugs generally are associated with a rapid reduction in pruritus and, depending on the drug, very quick and profound effects on objective signs of AD.10-12 Two head-to-head studies have been completed comparing dupilumab to oral JAK inhibitors in adults: the JADE COMPARE trial examining dupilumab vs abrocitinib12 and the Heads UP trial comparing dupilumab vs upadacitinib.14 Compared to dupilumab, higher-dose abrocitinib showed more rapid responses, superiority in itch response, and similarity or superiority in other outcomes depending on the time point of the evaluation. Adverse event profiles differed; for example, abrocitinib was associated with more nausea, acneform eruptions, and herpes zoster, while dupilumab had higher rates of conjunctivitis.12 Upadacitinib, which was only studied at higher dosing (30 mg daily), showed superiority to dupilumab in itch response and in improvement in AD severity in multiple outcome measures; however, there were increases in serious infections, eczema herpeticum, herpes zoster, and laboratory-related adverse events.14 Dupilumab has the advantage of studies of extended use along with real-world experience, generally with excellent safety and tolerance other than injection-site reactions and conjunctivitis.8 Biologics targeting IL-13—tralokinumab and lebrikizumab—also are to be added to our armamentarium.15,16 The addition of these agents and JAK inhibitors as new systemic treatment options points to the quickly evolving future of AD treatment for patients with extensive disease.

New topical therapies in development provide even more treatment options. New nonsteroidal topicals include topical JAK inhibitors such as ruxolitinib17; tapinarof,18 an aryl hydrocarbon receptor modulator; and phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors. These agents may be useful either as monotherapy, as studied, potentially without the regional limitations associated with stronger topical corticosteroids, but also should be useful in clinical practice as part of therapeutic regimens with other topical steroid and nonsteroidal agents.

The Microbiome and AD

In addition, research looking at topical microbes as specific interventions that may mediate the microbiome and inflammation of AD are intriguing. A recent phase 1 trial from the University of California San Diego19 indicated that topical bacteriotherapy directed at decreasing Staphylococcus aureus may provide an impact in AD. Observations by Kong et al20 showed that gram-negative microbiome differences are seen in AD patients compared to unaffected individuals, which has fueled studies showing that Roseomonas mucosa, a gram-negative skin commensal, when applied as a topical live biotherapeutic agent has improved disease severity in children and adults with AD.21 Although further studies are underway, these initial data suggest a role for microbiome-modifying therapies as AD treatment.

Chronic Hand Eczema

Chronic hand eczema (CHE), which has considerable overlap with AD in many patients, especially children and adolescents,22-24 is another area of interesting research. This high-prevalence condition is associated with allergic and irritant contact dermatitis24-26—conditions that are both considered alternative diagnoses for and exacerbators of AD27—and is a disease process currently being targeted for new therapies. Delgocitinib (NCT04872101, NCT04871711), the novel JAK inhibitor ARQ-252 (NCT04378569), among other topical agents, as well as systemic therapeutics such as gusacitinib (NCT03728504), are in active trials for CHE. Given CHE’s impact on quality of life28 and its overlap with AD, investigation into this disorder can help drive future AD research as well as lead to better knowledge and treatment of CHE.

Final Thoughts

Despite the promising results of these myriad new therapies in AD, there are many factors that influence how and when we use these drugs, including their approval status, FDA labeling, and the ability of patients to access and afford treatment. Additionally, continued study is needed to evaluate the long-term safety and extended efficacy of newer drugs, such as the oral JAK inhibitors. Despite these hurdles, the current landscape of research and development is rapidly evolving. Compared to the many years when only one main group of therapies was a reasonable option for patients, the future of AD treatment looks bright.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is an incredibly common chronic skin disease, affecting up to 25% of children and 7% of adults in the United States.1,2 Despite the prevalence of this disease and its impact on patient quality of life, research and scholarly work in AD has been limited until recent years. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term atopic dermatitis showed that there were fewer than 500 articles published in 2000 and 965 in 2010; with our more recent acceleration in research, there were 2168 articles published in 2020 and more than 1300 published in just the first half of 2021 (through June). This new research includes insights into the pathogenesis of AD and study of the disease impact and comorbidities as well as an extensive amount of drug development and clinical trial work for new topical and systemic therapies.

New Agents to Treat AD

The 2016 approval of crisaborole,3 a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, followed by the approval of dupilumab, an IL-4 and IL-13 pathway inhibitor and the first biologic agent approved for AD,4 ushered in a new age of therapy. We currently are awaiting the incorporation of a new set of topical nonsteroidal agents, oral Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, and new biologic agents for AD, several of which have completed phase 3 trials and extended safety evaluations. How these new drugs will impact our standard treatment across the spectrum of care for AD is not yet known.

The emergence of new systemic therapies is timely, as the most used systemic medications previously were oral corticosteroids, despite their use being advised against in standard practice guidelines. Other agents such as methotrexate, cyclosporine, azathioprine, and mycophenolate are discussed in the literature and AD treatment guidelines as being potentially useful, though absence of US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval and the need for frequent laboratory monitoring, as well as drug-specific side effects and an increased risk of infection, limit their use in the United States, especially in pediatric and adolescent populations.5

The approval of dupilumab as a systemic therapy—initially for adults and subsequently for teenagers (12–17 years of age) and then children (6–11 years of age)—has markedly influenced the standard of care for moderate to severe AD. This agent has been shown to have a considerable impact on disease severity and quality of life, with a good safety profile and the added benefit of not requiring continuous (or any) laboratory monitoring.6-8 Ongoing studies of dupilumab in children (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers NCT02612454, NCT03346434), including those younger than 1 year,9 raise the question of how commonly this medication might be incorporated into care across the entire age spectrum of patients with AD. What standards will there be for assessment of severity, disease impact, and persistence to warrant use in younger ages? Will early treatment with novel systemic agents change the overall course of the disease and minimize the development of comorbidities? The answers to these questions remain to be seen.

JAK Inhibitors for AD

Additional novel therapeutics currently are undergoing studies for treatment of AD, most notably the oral JAK inhibitors upadacitinib,10 baricitinib,11 and abrocitinib.12 Each of these agents has completed phase 3 trials for AD. Two of these agents—upadacitinib and baricitinib—have prior FDA approval for use in other disease states. Of note, baricitinib is already approved for treatment of moderate to severe AD in adults in more than 40 countries13; however, the use of these agents in other diseases brings about concerns of malignancy, severe infection, and thrombosis. In the clinical trials for AD, many of these events have not been seen, but the number of patients treated is limited, and longer-term safety assessment is important.10,11

How will the oral JAK inhibitors be incorporated into care compared to biologic agents such as dupilumab? Tolerance and more serious potential adverse events are concerns, with nausea, headaches, and acneform eruptions being associated with some of the medications, in addition to potential issues with herpes simplex and zoster infections. However, oral JAK inhibitors have the benefit of not requiring injections, something that many patients may prefer, and data show that these drugs generally are associated with a rapid reduction in pruritus and, depending on the drug, very quick and profound effects on objective signs of AD.10-12 Two head-to-head studies have been completed comparing dupilumab to oral JAK inhibitors in adults: the JADE COMPARE trial examining dupilumab vs abrocitinib12 and the Heads UP trial comparing dupilumab vs upadacitinib.14 Compared to dupilumab, higher-dose abrocitinib showed more rapid responses, superiority in itch response, and similarity or superiority in other outcomes depending on the time point of the evaluation. Adverse event profiles differed; for example, abrocitinib was associated with more nausea, acneform eruptions, and herpes zoster, while dupilumab had higher rates of conjunctivitis.12 Upadacitinib, which was only studied at higher dosing (30 mg daily), showed superiority to dupilumab in itch response and in improvement in AD severity in multiple outcome measures; however, there were increases in serious infections, eczema herpeticum, herpes zoster, and laboratory-related adverse events.14 Dupilumab has the advantage of studies of extended use along with real-world experience, generally with excellent safety and tolerance other than injection-site reactions and conjunctivitis.8 Biologics targeting IL-13—tralokinumab and lebrikizumab—also are to be added to our armamentarium.15,16 The addition of these agents and JAK inhibitors as new systemic treatment options points to the quickly evolving future of AD treatment for patients with extensive disease.

New topical therapies in development provide even more treatment options. New nonsteroidal topicals include topical JAK inhibitors such as ruxolitinib17; tapinarof,18 an aryl hydrocarbon receptor modulator; and phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors. These agents may be useful either as monotherapy, as studied, potentially without the regional limitations associated with stronger topical corticosteroids, but also should be useful in clinical practice as part of therapeutic regimens with other topical steroid and nonsteroidal agents.

The Microbiome and AD

In addition, research looking at topical microbes as specific interventions that may mediate the microbiome and inflammation of AD are intriguing. A recent phase 1 trial from the University of California San Diego19 indicated that topical bacteriotherapy directed at decreasing Staphylococcus aureus may provide an impact in AD. Observations by Kong et al20 showed that gram-negative microbiome differences are seen in AD patients compared to unaffected individuals, which has fueled studies showing that Roseomonas mucosa, a gram-negative skin commensal, when applied as a topical live biotherapeutic agent has improved disease severity in children and adults with AD.21 Although further studies are underway, these initial data suggest a role for microbiome-modifying therapies as AD treatment.

Chronic Hand Eczema

Chronic hand eczema (CHE), which has considerable overlap with AD in many patients, especially children and adolescents,22-24 is another area of interesting research. This high-prevalence condition is associated with allergic and irritant contact dermatitis24-26—conditions that are both considered alternative diagnoses for and exacerbators of AD27—and is a disease process currently being targeted for new therapies. Delgocitinib (NCT04872101, NCT04871711), the novel JAK inhibitor ARQ-252 (NCT04378569), among other topical agents, as well as systemic therapeutics such as gusacitinib (NCT03728504), are in active trials for CHE. Given CHE’s impact on quality of life28 and its overlap with AD, investigation into this disorder can help drive future AD research as well as lead to better knowledge and treatment of CHE.

Final Thoughts

Despite the promising results of these myriad new therapies in AD, there are many factors that influence how and when we use these drugs, including their approval status, FDA labeling, and the ability of patients to access and afford treatment. Additionally, continued study is needed to evaluate the long-term safety and extended efficacy of newer drugs, such as the oral JAK inhibitors. Despite these hurdles, the current landscape of research and development is rapidly evolving. Compared to the many years when only one main group of therapies was a reasonable option for patients, the future of AD treatment looks bright.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Chamlin SL, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 1. diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:338-351. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.10.010

- Chiesa Fuxench ZC, Block JK, Boguniewicz M, et al. Atopic dermatitis in America study: a cross-sectional study examining the prevalence and disease burden of atopic dermatitis in the US adult population. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:583-590. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2018.08.028

- FDA approves Eucrisa for eczema. News release. US Food and Drug Administration; December 14, 2016. Accessed August 16, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-eucrisa-eczema

- Gooderham MJ, Hong HC, Eshtiaghi P, et al. Dupilumab: a review of its use in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(3 suppl 1):S28-S36. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.12.022

- Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 3. management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:327-349. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.030

- Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Thaçi D, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab with concomitant topical corticosteroids in children 6 to 11 years old with severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1282-1293. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.054

- Simpson EL, Paller AS, Siegfried EC, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adolescents with uncontrolled moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:44-56. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3336

- Deleuran M, Thaçi D, Beck LA, et al. Dupilumab shows long-term safety and efficacy in patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis enrolled in a phase 3 open-label extension study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:377-388. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.07.074

- Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Simpson EL, et al. A phase 2, open-label study of single-dose dupilumab in children aged 6 months to <6 years with severe uncontrolled atopic dermatitis: pharmacokinetics, safety and efficacy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:464-475. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16928

- Reich K, Teixeira HD, de Bruin-Weller M, et al. Safety and efficacy of upadacitinib in combination with topical corticosteroids in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD Up): results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;397:2169-2181. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00589-4

- Simpson EL, Forman S, Silverberg JI, et al. Baricitinib in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from a randomized monotherapy phase 3 trial in the United States and Canada (BREEZE-AD5). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:62-70. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.02.028

- Bieber T, Simpson EL, Silverberg JI, et al. Abrocitinib versus placebo or dupilumab for atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1101-1112. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2019380

- Lilly and Incyte provide update on supplemental New Drug Application for baricitinib for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. News release. Eli Lilly and Company; July 16, 2021. Accessed August 16, 2021. https://investor.lilly.com/news-releases/news-release-details/lilly-and-incyte-provide-update-supplemental new-drug

- Blauvelt A, Teixeira HD, Simpson EL, et al. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib vs dupilumab in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized clinical trial [published online August 4, 2021]. JAMA Dermatol. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.3023

- Guttman-Yassky E, Blauvelt A, Eichenfield LF, et al. Efficacy and safety of lebrikizumab, a high-affinity interleukin 13 inhibitor, in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 2b randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:411-420. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0079

- Silverberg JI, Toth D, Bieber T, et al. Tralokinumab plus topical corticosteroids for the treatment of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from the double-blind, randomized, multicentre,placebo-controlled phase III ECZTRA 3 trial. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184:450-463. doi:10.1111/bjd.19573

- Papp K, Szepietowski JC, Kircik L, et al. Efficacy and safety of ruxolitinib cream for the treatment of atopic dermatitis: results from 2 phase 3, randomized, double-blind studies [published online May 4, 2021]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.04.085

- Paller AS, Stein Gold L, Soung J, et al. Efficacy and patient-reported outcomes from a phase 2b, randomized clinical trial of tapinarof cream for the treatment of adolescents and adults with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:632-638. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.135

- Nakatsuji, T, Hata TR, Tong Y, et al. Development of a human skin commensal microbe for bacteriotherapy of atopic dermatitis and use in a phase 1 randomized clinical trial [published online February 22, 2021]. Nat Med. 2021;27:700-709. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01256-2

- Kong HH, Oh J, Deming C, et al. Temporal shifts in the skin microbiome associated with disease flares and treatment in children with atopic dermatitis. Genome Res. 2012;22:850-859. doi:10.1101/gr.131029.111

- Myles IA, Castillo CR, Barbian KD, et al. Therapeutic responses to Roseomonas mucosa in atopic dermatitis may involve lipid-mediated TNF-related epithelial repair. Sci Transl Med. 2020;12:eaaz8631. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aaz8631

- Mortz CG, Lauritsen JM, Bindslev-Jensen C, et al. Prevalence of atopic dermatitis, asthma, allergic rhinitis, and hand and contact dermatitis in adolescents. The Odense Adolescence Cohort Study on Atopic Diseases and Dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:523-532. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04078.x

- Grönhagen C, Lidén C, Wahlgren CF, et al. Hand eczema and atopic dermatitis in adolescents: a prospective cohort study from the BAMSE project. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:1175-1182. doi:10.1111/bjd.14019

- Mortz CG, Lauritsen JM, Bindslev-Jensen C, et al. Contact allergy and allergic contact dermatitis in adolescents: prevalence measures and associations. The Odense Adolescence Cohort Study on Atopic Diseases and Dermatitis (TOACS). Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:352-358. doi:10.1080/000155502320624087

- Isaksson M, Olhardt S, Rådehed J, et al. Children with atopic dermatitis should always be patch-tested if they have hand or foot dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:583-586. doi:10.2340/00015555-1995

- Silverberg JI, Warshaw EM, Maibach HI, et al. Hand eczema in children referred for patch testing: North American Contact Dermatitis Group Data, 2000-2016. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:185-194. doi:10.1111/bjd.19818

- Agner T, Elsner P. Hand eczema: epidemiology, prognosis and prevention. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(suppl 1):4-12. doi:10.1111/jdv.16061

- Cazzaniga S, Ballmer-Weber BK, Gräni N, et al. Medical, psychological and socio-economic implications of chronic hand eczema: a cross-sectional study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:628-637. doi:10.1111/jdv.13479

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Chamlin SL, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 1. diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:338-351. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.10.010

- Chiesa Fuxench ZC, Block JK, Boguniewicz M, et al. Atopic dermatitis in America study: a cross-sectional study examining the prevalence and disease burden of atopic dermatitis in the US adult population. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:583-590. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2018.08.028

- FDA approves Eucrisa for eczema. News release. US Food and Drug Administration; December 14, 2016. Accessed August 16, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-eucrisa-eczema

- Gooderham MJ, Hong HC, Eshtiaghi P, et al. Dupilumab: a review of its use in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(3 suppl 1):S28-S36. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.12.022

- Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 3. management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:327-349. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.030

- Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Thaçi D, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab with concomitant topical corticosteroids in children 6 to 11 years old with severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1282-1293. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.054

- Simpson EL, Paller AS, Siegfried EC, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adolescents with uncontrolled moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:44-56. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3336

- Deleuran M, Thaçi D, Beck LA, et al. Dupilumab shows long-term safety and efficacy in patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis enrolled in a phase 3 open-label extension study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:377-388. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.07.074

- Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Simpson EL, et al. A phase 2, open-label study of single-dose dupilumab in children aged 6 months to <6 years with severe uncontrolled atopic dermatitis: pharmacokinetics, safety and efficacy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:464-475. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16928

- Reich K, Teixeira HD, de Bruin-Weller M, et al. Safety and efficacy of upadacitinib in combination with topical corticosteroids in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD Up): results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;397:2169-2181. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00589-4

- Simpson EL, Forman S, Silverberg JI, et al. Baricitinib in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from a randomized monotherapy phase 3 trial in the United States and Canada (BREEZE-AD5). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:62-70. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.02.028

- Bieber T, Simpson EL, Silverberg JI, et al. Abrocitinib versus placebo or dupilumab for atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1101-1112. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2019380

- Lilly and Incyte provide update on supplemental New Drug Application for baricitinib for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. News release. Eli Lilly and Company; July 16, 2021. Accessed August 16, 2021. https://investor.lilly.com/news-releases/news-release-details/lilly-and-incyte-provide-update-supplemental new-drug

- Blauvelt A, Teixeira HD, Simpson EL, et al. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib vs dupilumab in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized clinical trial [published online August 4, 2021]. JAMA Dermatol. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.3023

- Guttman-Yassky E, Blauvelt A, Eichenfield LF, et al. Efficacy and safety of lebrikizumab, a high-affinity interleukin 13 inhibitor, in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 2b randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:411-420. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0079

- Silverberg JI, Toth D, Bieber T, et al. Tralokinumab plus topical corticosteroids for the treatment of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from the double-blind, randomized, multicentre,placebo-controlled phase III ECZTRA 3 trial. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184:450-463. doi:10.1111/bjd.19573

- Papp K, Szepietowski JC, Kircik L, et al. Efficacy and safety of ruxolitinib cream for the treatment of atopic dermatitis: results from 2 phase 3, randomized, double-blind studies [published online May 4, 2021]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.04.085

- Paller AS, Stein Gold L, Soung J, et al. Efficacy and patient-reported outcomes from a phase 2b, randomized clinical trial of tapinarof cream for the treatment of adolescents and adults with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:632-638. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.135

- Nakatsuji, T, Hata TR, Tong Y, et al. Development of a human skin commensal microbe for bacteriotherapy of atopic dermatitis and use in a phase 1 randomized clinical trial [published online February 22, 2021]. Nat Med. 2021;27:700-709. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01256-2

- Kong HH, Oh J, Deming C, et al. Temporal shifts in the skin microbiome associated with disease flares and treatment in children with atopic dermatitis. Genome Res. 2012;22:850-859. doi:10.1101/gr.131029.111

- Myles IA, Castillo CR, Barbian KD, et al. Therapeutic responses to Roseomonas mucosa in atopic dermatitis may involve lipid-mediated TNF-related epithelial repair. Sci Transl Med. 2020;12:eaaz8631. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aaz8631

- Mortz CG, Lauritsen JM, Bindslev-Jensen C, et al. Prevalence of atopic dermatitis, asthma, allergic rhinitis, and hand and contact dermatitis in adolescents. The Odense Adolescence Cohort Study on Atopic Diseases and Dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:523-532. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04078.x

- Grönhagen C, Lidén C, Wahlgren CF, et al. Hand eczema and atopic dermatitis in adolescents: a prospective cohort study from the BAMSE project. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:1175-1182. doi:10.1111/bjd.14019

- Mortz CG, Lauritsen JM, Bindslev-Jensen C, et al. Contact allergy and allergic contact dermatitis in adolescents: prevalence measures and associations. The Odense Adolescence Cohort Study on Atopic Diseases and Dermatitis (TOACS). Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:352-358. doi:10.1080/000155502320624087

- Isaksson M, Olhardt S, Rådehed J, et al. Children with atopic dermatitis should always be patch-tested if they have hand or foot dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:583-586. doi:10.2340/00015555-1995

- Silverberg JI, Warshaw EM, Maibach HI, et al. Hand eczema in children referred for patch testing: North American Contact Dermatitis Group Data, 2000-2016. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:185-194. doi:10.1111/bjd.19818

- Agner T, Elsner P. Hand eczema: epidemiology, prognosis and prevention. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(suppl 1):4-12. doi:10.1111/jdv.16061

- Cazzaniga S, Ballmer-Weber BK, Gräni N, et al. Medical, psychological and socio-economic implications of chronic hand eczema: a cross-sectional study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:628-637. doi:10.1111/jdv.13479

Treatment Options for Atopic Dermatitis in Children

Until recently, atopic dermatitis was considered a childhood disease that was self-limited over a few years. Emerging studies have shown that the burden of atopic dermatitis includes potential cardiac disease in adulthood, comorbidities including allergy and psychological disorders, and possible superinfection complications.

Dr Lawrence F. Eichenfield, chief of the department of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children's Hospital, reports on biological, systemic, and topical treatments either currently in use or being studied for children suffering from atopic dermatitis. These studies include both steroid and steroid-sparing topical agents, a novel AhR modulating agent, as well as JAK inhibitors that are under active investigation.

--

Lawrence F. Eichenfield, MD, Distinguished Professor; Vice Chair, Department of Dermatology and Pediatrics, University of California, San Diego; Chief, Department of Pediatric and Adolescent Dermatology, Rady Children's Hospital, San Diego, California.

Lawrence F. Eichenfield, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: AbbVie; Dermavant; Dermira; Forte Biosciences; Galderma Laboratories; Incyte; Leo Pharma; Eli Lilly and Company; Otsuka; Novartis; Pfizer. Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Regeneron; Sanofi-Genzyme; Pfizer. Received research grant from: AbbVie; Regeneron; Sanofi Genzyme; Ortho Dermatology. Serve(d) on the data safety monitoring board for: Asana; Glenmark/Ichnos.

Until recently, atopic dermatitis was considered a childhood disease that was self-limited over a few years. Emerging studies have shown that the burden of atopic dermatitis includes potential cardiac disease in adulthood, comorbidities including allergy and psychological disorders, and possible superinfection complications.

Dr Lawrence F. Eichenfield, chief of the department of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children's Hospital, reports on biological, systemic, and topical treatments either currently in use or being studied for children suffering from atopic dermatitis. These studies include both steroid and steroid-sparing topical agents, a novel AhR modulating agent, as well as JAK inhibitors that are under active investigation.

--

Lawrence F. Eichenfield, MD, Distinguished Professor; Vice Chair, Department of Dermatology and Pediatrics, University of California, San Diego; Chief, Department of Pediatric and Adolescent Dermatology, Rady Children's Hospital, San Diego, California.

Lawrence F. Eichenfield, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: AbbVie; Dermavant; Dermira; Forte Biosciences; Galderma Laboratories; Incyte; Leo Pharma; Eli Lilly and Company; Otsuka; Novartis; Pfizer. Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Regeneron; Sanofi-Genzyme; Pfizer. Received research grant from: AbbVie; Regeneron; Sanofi Genzyme; Ortho Dermatology. Serve(d) on the data safety monitoring board for: Asana; Glenmark/Ichnos.

Until recently, atopic dermatitis was considered a childhood disease that was self-limited over a few years. Emerging studies have shown that the burden of atopic dermatitis includes potential cardiac disease in adulthood, comorbidities including allergy and psychological disorders, and possible superinfection complications.

Dr Lawrence F. Eichenfield, chief of the department of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children's Hospital, reports on biological, systemic, and topical treatments either currently in use or being studied for children suffering from atopic dermatitis. These studies include both steroid and steroid-sparing topical agents, a novel AhR modulating agent, as well as JAK inhibitors that are under active investigation.

--

Lawrence F. Eichenfield, MD, Distinguished Professor; Vice Chair, Department of Dermatology and Pediatrics, University of California, San Diego; Chief, Department of Pediatric and Adolescent Dermatology, Rady Children's Hospital, San Diego, California.

Lawrence F. Eichenfield, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: AbbVie; Dermavant; Dermira; Forte Biosciences; Galderma Laboratories; Incyte; Leo Pharma; Eli Lilly and Company; Otsuka; Novartis; Pfizer. Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Regeneron; Sanofi-Genzyme; Pfizer. Received research grant from: AbbVie; Regeneron; Sanofi Genzyme; Ortho Dermatology. Serve(d) on the data safety monitoring board for: Asana; Glenmark/Ichnos.

What's the diagnosis?

Nipple eczema is a dermatitis of the nipple and areola with clinical features such as erythema, fissures, scaling, pruritus, and crusting.1,2 It is classically associated with atopic dermatitis (AD), though it may occur as an isolated condition less commonly. While it may affect female adolescents, nipple eczema has also been reported in boys and breastfeeding women.3,4 The overall risk of incidence of nipple dermatitis has also been shown to increase with age.5 Nipple eczema is considered a cutaneous finding of AD, and is listed as a minor diagnostic criteria for AD in the Hanifin-Rajka criteria.6 The patient had not related his history of AD, which was elicited after finding typical antecubital eczematous dermatitis, and he had not been actively treating it.

Diagnosis and differential

Nipple eczema may be a challenging diagnosis for various reasons. For example, a unilateral presentation and the changes in the eczematous lesions overlying the nipple and areola’s varying textures and colors can make it difficult for clinicians to identify.3 Many children and adolescents, including our patient, are initially diagnosed as having impetigo and treated with antibiotics. The diagnosis of nipple eczema is made clinically, and management straightforward (see below). However, additional testing may be appropriate including patch testing for allergic contact dermatitis or bacterial cultures if bacterial infection or superinfection is considered.7,8 The differential diagnosis for nipple eczema includes impetigo, gynecomastia, scabies, and allergic contact dermatitis.

Impetigo typically presents with honey-colored crusts or pustules caused by infection with Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus. Patients with AD have higher rates of colonization with S. aureus and impetiginized eczema in common. Impetigo of the nipple and areola is more common in breastfeeding women as skin cracking from lactation can lead to exposure to bacteria from the infant’s mouth.9 Treatments involve topical or oral antibiotics.

Gynecomastia is the development of male breast tissue with most cases hypothesized to be caused by an imbalance between androgens and estrogens.10 Some other causes include direct skin contact with topical estrogen sprays and recreational use of marijuana and heroin.11 It is usually a benign exam finding in adolescent boys. However, clinical findings such as overlying skin changes, rapidly enlarging masses, and constitutional symptoms are concerning in the setting of gynecomastia and warrant further evaluation.

Scabies, which is caused by the infestation of scabies mites, is a common infectious skin disease. The classic presentation includes a rash that is intensely itchy, especially at night. Crusted scabies of the nipples may be difficult to distinguish from nipple eczema. Areas of frequent involvement of scabies include palms, between fingers, armpits, groin, between toes, and feet. Treatments include treating all household members with permethrin cream and washing all clothes and bedding in contact with a scabies-infected patient in high heat, or oral ivermectin in certain circumstances.12

Allergic contact dermatitis is a common cause of breast and nipple dermatitis and should be considered within the differential diagnosis of nipple eczema with atopic dermatitis, or as an exacerbator.7,9 Patients in particular who present with bilateral involvement extending to the periareolar skin, or unusual bilateral focal patterns suggestive for contact allergy should be considered for allergic contact dermatitis evaluation with patch tests. A common causative agent for allergic contact dermatitis of the breast and nipple includes Cl+Me-isothiazolinone, commonly found in detergents and fabric softeners.7 Primary treatment includes avoidance of the offending agents.

Treatment

Topical corticosteroids are first-line treatment for treating nipple eczema. Low-potency topical steroids can be used for maintenance and mild eczema while more potent steroids are useful for more severe cases. In addition to topical medication therapy, frequent emollient use to protect the skin barrier and the elimination of any irritants are essential to a successful treatment course. Unilateral nipple eczema can also be secondary to inadequate treatment of AD, demonstrating the importance of addressing the underlying AD with therapy.3

Our patient was diagnosed with nipple eczema based on clinical presentation of an eczematous left nipple in the setting of active atopic dermatitis and minimal improvement on topical antibiotic. He was started on a 3-week course of fluocinonide 0.05% topical ointment (a potent topical corticosteroid) twice daily for 2 weeks with plans to transition to triamcinolone 0.1% topical ointment several times a week.

Ms. Park is a pediatric dermatology research associate in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology, University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital. Neither Ms. Park nor Dr. Eichenfield have any relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22(1):64-6.

2. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37(4):284-8.

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32(5):718-22.

4. J Cutan Med Surg. 2004;8(2):126-30.

5. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29(5):580-3.

6. Dermatologica. 1988;177(6):360-4.

7. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26(3):413-4.

8. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13(8).

9. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(6):1483-94.

10. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2017;14(4):371-7.

11. JAMA. 2010;304(9):953.

12. JAMA. 2018;320(6):612.

Nipple eczema is a dermatitis of the nipple and areola with clinical features such as erythema, fissures, scaling, pruritus, and crusting.1,2 It is classically associated with atopic dermatitis (AD), though it may occur as an isolated condition less commonly. While it may affect female adolescents, nipple eczema has also been reported in boys and breastfeeding women.3,4 The overall risk of incidence of nipple dermatitis has also been shown to increase with age.5 Nipple eczema is considered a cutaneous finding of AD, and is listed as a minor diagnostic criteria for AD in the Hanifin-Rajka criteria.6 The patient had not related his history of AD, which was elicited after finding typical antecubital eczematous dermatitis, and he had not been actively treating it.

Diagnosis and differential

Nipple eczema may be a challenging diagnosis for various reasons. For example, a unilateral presentation and the changes in the eczematous lesions overlying the nipple and areola’s varying textures and colors can make it difficult for clinicians to identify.3 Many children and adolescents, including our patient, are initially diagnosed as having impetigo and treated with antibiotics. The diagnosis of nipple eczema is made clinically, and management straightforward (see below). However, additional testing may be appropriate including patch testing for allergic contact dermatitis or bacterial cultures if bacterial infection or superinfection is considered.7,8 The differential diagnosis for nipple eczema includes impetigo, gynecomastia, scabies, and allergic contact dermatitis.

Impetigo typically presents with honey-colored crusts or pustules caused by infection with Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus. Patients with AD have higher rates of colonization with S. aureus and impetiginized eczema in common. Impetigo of the nipple and areola is more common in breastfeeding women as skin cracking from lactation can lead to exposure to bacteria from the infant’s mouth.9 Treatments involve topical or oral antibiotics.

Gynecomastia is the development of male breast tissue with most cases hypothesized to be caused by an imbalance between androgens and estrogens.10 Some other causes include direct skin contact with topical estrogen sprays and recreational use of marijuana and heroin.11 It is usually a benign exam finding in adolescent boys. However, clinical findings such as overlying skin changes, rapidly enlarging masses, and constitutional symptoms are concerning in the setting of gynecomastia and warrant further evaluation.

Scabies, which is caused by the infestation of scabies mites, is a common infectious skin disease. The classic presentation includes a rash that is intensely itchy, especially at night. Crusted scabies of the nipples may be difficult to distinguish from nipple eczema. Areas of frequent involvement of scabies include palms, between fingers, armpits, groin, between toes, and feet. Treatments include treating all household members with permethrin cream and washing all clothes and bedding in contact with a scabies-infected patient in high heat, or oral ivermectin in certain circumstances.12

Allergic contact dermatitis is a common cause of breast and nipple dermatitis and should be considered within the differential diagnosis of nipple eczema with atopic dermatitis, or as an exacerbator.7,9 Patients in particular who present with bilateral involvement extending to the periareolar skin, or unusual bilateral focal patterns suggestive for contact allergy should be considered for allergic contact dermatitis evaluation with patch tests. A common causative agent for allergic contact dermatitis of the breast and nipple includes Cl+Me-isothiazolinone, commonly found in detergents and fabric softeners.7 Primary treatment includes avoidance of the offending agents.

Treatment

Topical corticosteroids are first-line treatment for treating nipple eczema. Low-potency topical steroids can be used for maintenance and mild eczema while more potent steroids are useful for more severe cases. In addition to topical medication therapy, frequent emollient use to protect the skin barrier and the elimination of any irritants are essential to a successful treatment course. Unilateral nipple eczema can also be secondary to inadequate treatment of AD, demonstrating the importance of addressing the underlying AD with therapy.3

Our patient was diagnosed with nipple eczema based on clinical presentation of an eczematous left nipple in the setting of active atopic dermatitis and minimal improvement on topical antibiotic. He was started on a 3-week course of fluocinonide 0.05% topical ointment (a potent topical corticosteroid) twice daily for 2 weeks with plans to transition to triamcinolone 0.1% topical ointment several times a week.

Ms. Park is a pediatric dermatology research associate in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology, University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital. Neither Ms. Park nor Dr. Eichenfield have any relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22(1):64-6.

2. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37(4):284-8.

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32(5):718-22.

4. J Cutan Med Surg. 2004;8(2):126-30.

5. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29(5):580-3.

6. Dermatologica. 1988;177(6):360-4.

7. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26(3):413-4.

8. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13(8).

9. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(6):1483-94.

10. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2017;14(4):371-7.

11. JAMA. 2010;304(9):953.

12. JAMA. 2018;320(6):612.

Nipple eczema is a dermatitis of the nipple and areola with clinical features such as erythema, fissures, scaling, pruritus, and crusting.1,2 It is classically associated with atopic dermatitis (AD), though it may occur as an isolated condition less commonly. While it may affect female adolescents, nipple eczema has also been reported in boys and breastfeeding women.3,4 The overall risk of incidence of nipple dermatitis has also been shown to increase with age.5 Nipple eczema is considered a cutaneous finding of AD, and is listed as a minor diagnostic criteria for AD in the Hanifin-Rajka criteria.6 The patient had not related his history of AD, which was elicited after finding typical antecubital eczematous dermatitis, and he had not been actively treating it.

Diagnosis and differential

Nipple eczema may be a challenging diagnosis for various reasons. For example, a unilateral presentation and the changes in the eczematous lesions overlying the nipple and areola’s varying textures and colors can make it difficult for clinicians to identify.3 Many children and adolescents, including our patient, are initially diagnosed as having impetigo and treated with antibiotics. The diagnosis of nipple eczema is made clinically, and management straightforward (see below). However, additional testing may be appropriate including patch testing for allergic contact dermatitis or bacterial cultures if bacterial infection or superinfection is considered.7,8 The differential diagnosis for nipple eczema includes impetigo, gynecomastia, scabies, and allergic contact dermatitis.

Impetigo typically presents with honey-colored crusts or pustules caused by infection with Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus. Patients with AD have higher rates of colonization with S. aureus and impetiginized eczema in common. Impetigo of the nipple and areola is more common in breastfeeding women as skin cracking from lactation can lead to exposure to bacteria from the infant’s mouth.9 Treatments involve topical or oral antibiotics.

Gynecomastia is the development of male breast tissue with most cases hypothesized to be caused by an imbalance between androgens and estrogens.10 Some other causes include direct skin contact with topical estrogen sprays and recreational use of marijuana and heroin.11 It is usually a benign exam finding in adolescent boys. However, clinical findings such as overlying skin changes, rapidly enlarging masses, and constitutional symptoms are concerning in the setting of gynecomastia and warrant further evaluation.

Scabies, which is caused by the infestation of scabies mites, is a common infectious skin disease. The classic presentation includes a rash that is intensely itchy, especially at night. Crusted scabies of the nipples may be difficult to distinguish from nipple eczema. Areas of frequent involvement of scabies include palms, between fingers, armpits, groin, between toes, and feet. Treatments include treating all household members with permethrin cream and washing all clothes and bedding in contact with a scabies-infected patient in high heat, or oral ivermectin in certain circumstances.12

Allergic contact dermatitis is a common cause of breast and nipple dermatitis and should be considered within the differential diagnosis of nipple eczema with atopic dermatitis, or as an exacerbator.7,9 Patients in particular who present with bilateral involvement extending to the periareolar skin, or unusual bilateral focal patterns suggestive for contact allergy should be considered for allergic contact dermatitis evaluation with patch tests. A common causative agent for allergic contact dermatitis of the breast and nipple includes Cl+Me-isothiazolinone, commonly found in detergents and fabric softeners.7 Primary treatment includes avoidance of the offending agents.

Treatment

Topical corticosteroids are first-line treatment for treating nipple eczema. Low-potency topical steroids can be used for maintenance and mild eczema while more potent steroids are useful for more severe cases. In addition to topical medication therapy, frequent emollient use to protect the skin barrier and the elimination of any irritants are essential to a successful treatment course. Unilateral nipple eczema can also be secondary to inadequate treatment of AD, demonstrating the importance of addressing the underlying AD with therapy.3

Our patient was diagnosed with nipple eczema based on clinical presentation of an eczematous left nipple in the setting of active atopic dermatitis and minimal improvement on topical antibiotic. He was started on a 3-week course of fluocinonide 0.05% topical ointment (a potent topical corticosteroid) twice daily for 2 weeks with plans to transition to triamcinolone 0.1% topical ointment several times a week.

Ms. Park is a pediatric dermatology research associate in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology, University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital. Neither Ms. Park nor Dr. Eichenfield have any relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22(1):64-6.

2. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37(4):284-8.

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32(5):718-22.

4. J Cutan Med Surg. 2004;8(2):126-30.

5. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29(5):580-3.

6. Dermatologica. 1988;177(6):360-4.

7. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26(3):413-4.

8. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13(8).

9. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(6):1483-94.

10. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2017;14(4):371-7.

11. JAMA. 2010;304(9):953.

12. JAMA. 2018;320(6):612.

A 12-year-old boy presents to the dermatology clinic with a 1-month history of crusting and watery sticky drainage from the left nipple. Given concern for a possible skin infection, the patient was initially treated with mupirocin ointment for several weeks but without improvement. The affected area is sometimes itchy but not painful. He reports no prior history of similar problems.

On physical exam, he is noted to have an eczematous left nipple with edema, xerosis, and scaling overlying the entire areola. There is no evidence of visible discharge, pustules, or honey-colored crusts in the area. The extensor surfaces of his arms bilaterally have skin-colored follicular papules, and his antecubital fossa display erythematous scaling plaques with mild lichenification and excoriations.

Pediatric dermatology: Reflecting on 50 years

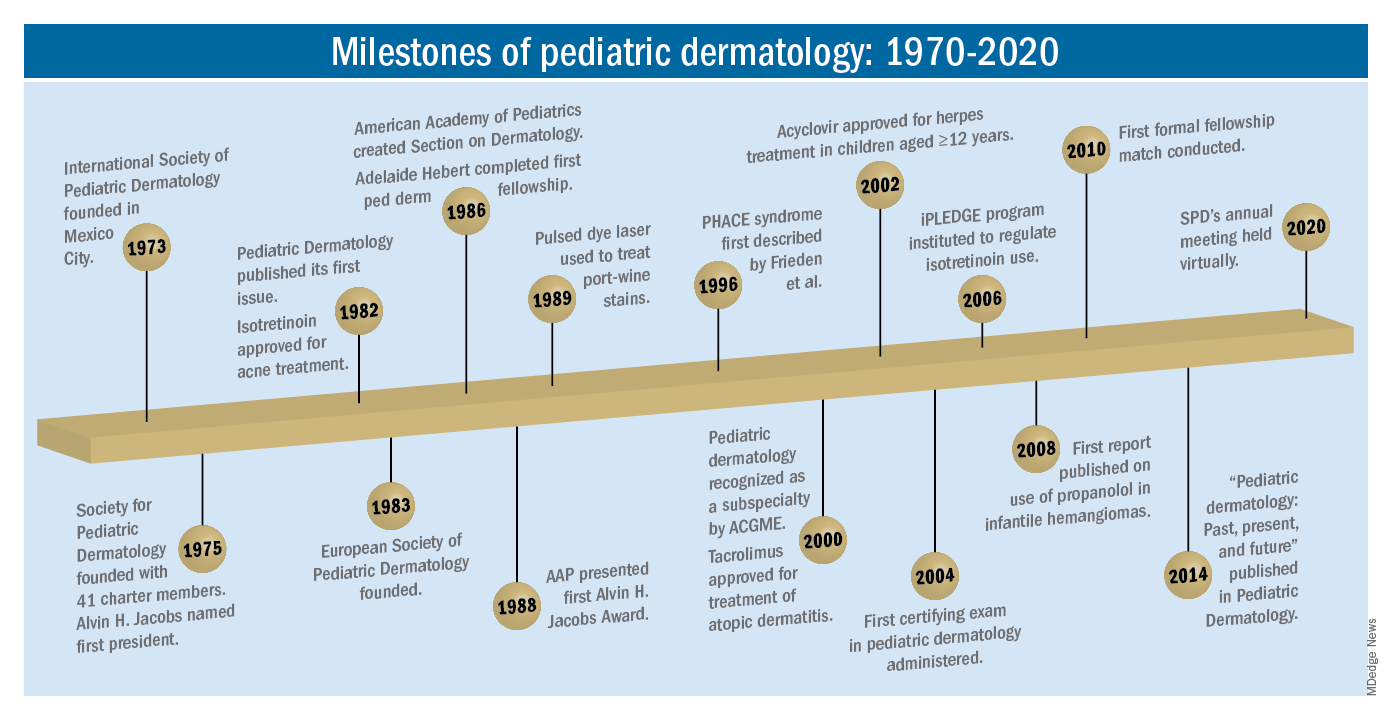

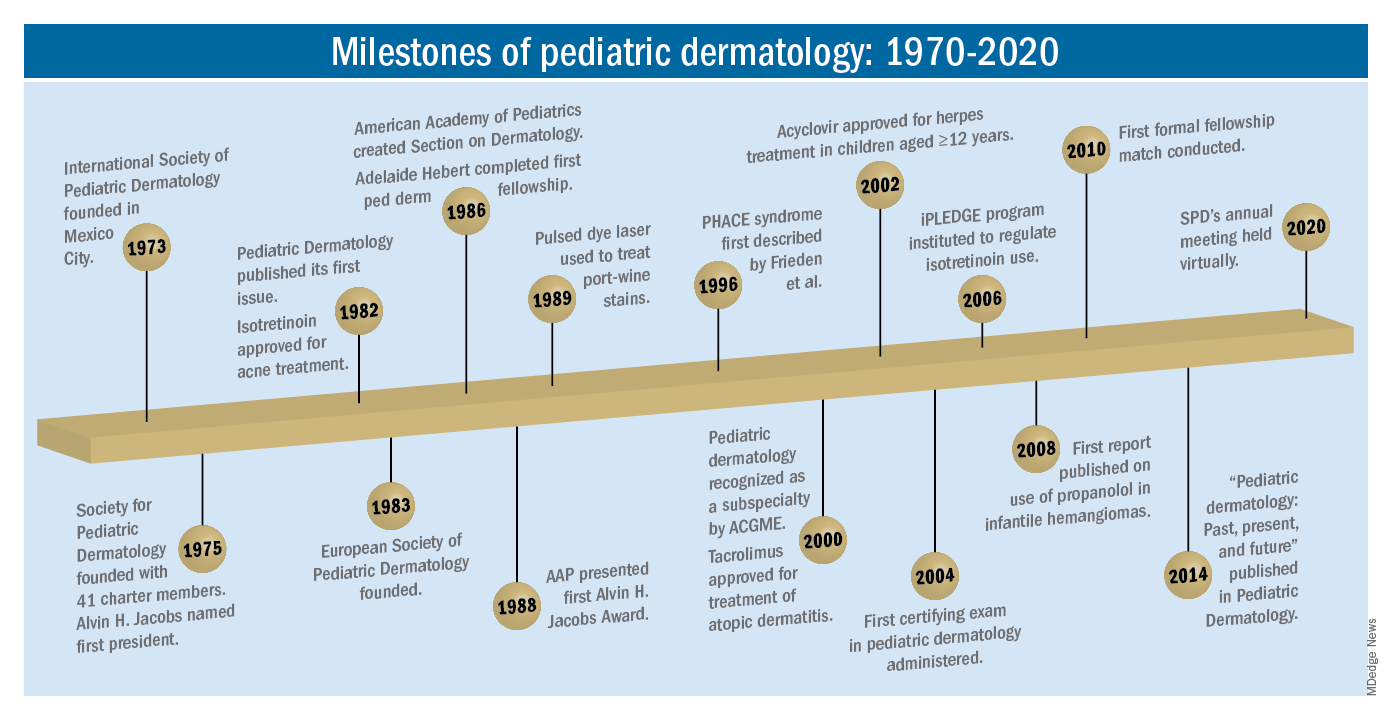

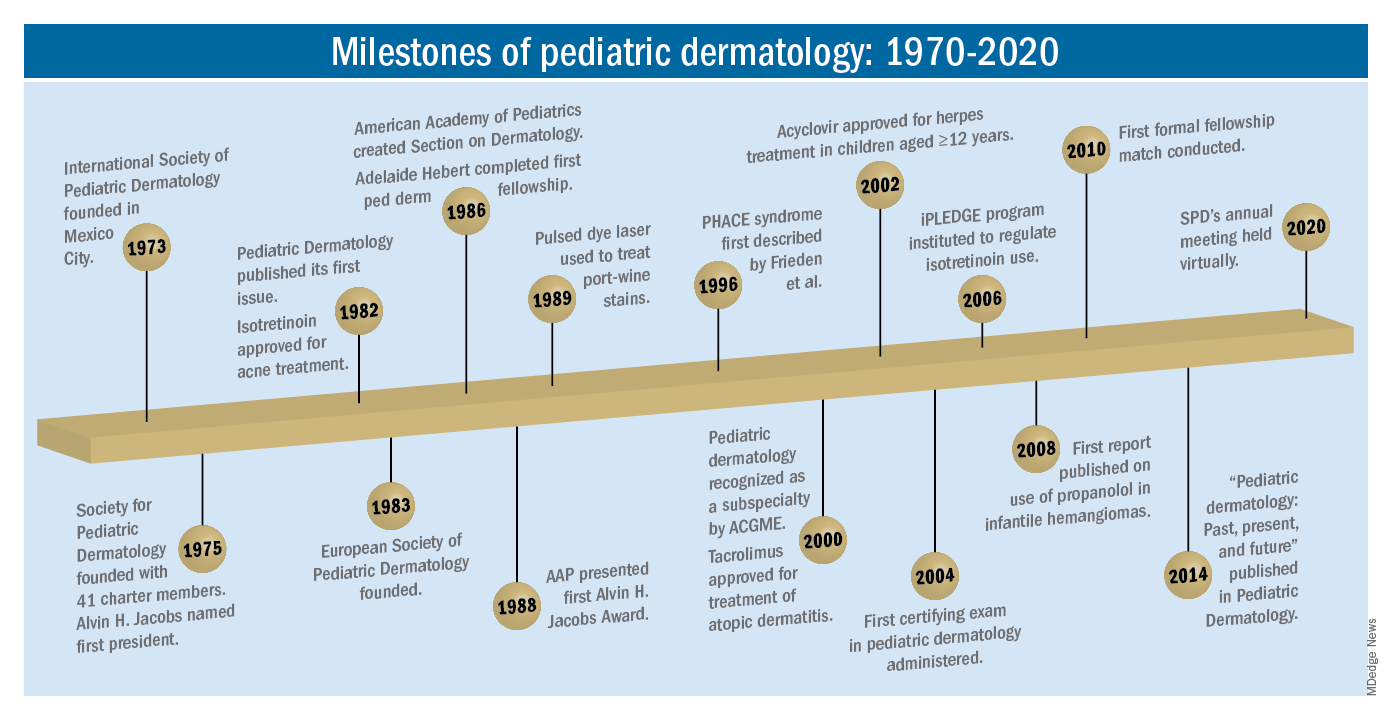

As part of the 50th anniversary of Dermatology News, it is intriguing to think about where a time machine journey 5 decades back would find the field of pediatric dermatology, and to assess the changes in the specialty during the time that Dermatology News (operating then as “Skin & Allergy News”) has been reporting on innovations and changes in the practice of dermatology.

So, starting . It was not until 3 years later, in October 1973 in Mexico City, that the first international symposium on Pediatric Dermatology was held, and the International Society for Pediatric Dermatology was founded. I reached out to Andrew Margileth, MD, 100 years old this past July, and still active voluntary faculty in pediatric dermatology at the University of Miami, to help me “reach back” to those days. Dr. Margileth commented on how the first symposium was “brilliantly orchestrated by Ramon Ruiz-Maldonado,” from the National Institute of Paediatrics in Mexico, and that it was his “Aha moment for future practice!” That meeting spurred discussions on the development of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology the next year, with Alvin Jacobs, MD; Samuel Weinberg, MD; Nancy Esterly, MD; Sidney Hurwitz, MD; William Weston, MD; and Coleman Jacobson, MD, as some of the initial “founding mothers and fathers,” and the society was officially established in 1975.

The field of pediatric dermatology was fairly “infantile” 50 years ago, with few practitioners. But the early leaders in the field recognized that up to 30% of pediatric primary care visits included skin problems, and that there was limited training for dermatologists, as well as pediatricians, about skin diseases in children. There were clearly clinical and educational needs to establish a subspecialty of pediatric dermatology, and over the next 1-2 decades, the field expanded. The journal Pediatric Dermatology was established (in 1982), the Section on Dermatology was established by the American Academy of Pediatrics (in 1986), and fellowship programs were launched at select academic centers. And it was 30 years into our timeline before the formal subspecialty of pediatric dermatology was established through the American Board of Dermatology (2000).

The field of pediatric dermatology has evolved and matured rapidly. Standard reference textbooks have been developed in the United States and around the world (and of course, online). Pediatric dermatology is an essential part of the core curriculum for dermatologist trainees. Organizations promoting pediatric research have developed to influence basic, translational, and clinical research in conditions in neonates through adolescents, such as the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance (PeDRA). And meetings throughout the world now feature pediatric dermatology sessions and help to spread the advances in the diagnosis and management of pediatric skin disorders.

The practice of pediatric dermatology: How has it changed?

It is beyond the scope of this article to try to comprehensively review all of the changes in pediatric dermatology practice. But review of the evolution of a few disease states (choices influenced by my discussions with my 100-year old history guide, Dr. Margileth) displays examples of where we have been, and where we are going in our next 5, 10, or 50 years.

Hemangiomas and vascular malformations

Some of the first natural history studies on hemangiomas were done in the early 1960s, establishing that standard cutaneous hemangiomas had a typical clinical course of fairly rapid growth, plateau, and involution over time. Of interest, the hallmark article’s first author was Dr. Margileth, published in 1965 in JAMA!.This was still at a time when the identification of hemangiomas of infancy (or “HOI” as we say in the trade) was confused with vascular malformations, and no one had recognized the distinct variant tumors such as rapidly involuting and noninvoluting congenital hemangiomas (RICHs or NICHs), tufted angiomas, or hemangioendotheliomas. PHACE syndrome was not yet described (that was done in 1996 by Ilona Frieden, MD, and colleagues). And for a time, hemangiomas were treated with x-rays, before the negative impact of such radiation was acknowledged. It seems that, as a consequence of the use of x-ray therapy and as a backlash from the radiation therapy side effects and potential toxicities, even deforming and functionally significant lesions were “followed clinically” for natural involution, with a sensibility that doing nothing might be better than doing the wrong thing.

Over the next 15 years, the recognition of functionally significant hemangiomas, deformation associated with their proliferation, and the recognition of PHACE syndrome made hemangiomas of infancy an area of concern, with systemic steroids and occasionally chemotherapeutic agents (such as vincristine) being used for problematic lesions.

It has now been 12 years since the work of Christine Léauté-Labrèze, MD, et al., from the University of Bordeaux (France), led to the breakthrough of propranolol for hemangioma treatment, profoundly changing hemangioma management to an incredibly effective medical therapy extensively studied, tested in formal clinical trials, and approved by regulatory authorities. And how intriguing that this was pursued after the chance (but skilled) observation that a child who developed hypertension as a side effect of systemic steroids for nasal hemangioma treatment was prescribed propranolol for the hypertension and had his nasal hemangioma rapidly shrink, with a response superior and much quicker than that to corticosteroids.

The evolution of management of hemangiomas has another story within it, that of collaborative research. The Hemangioma Investigator Group was formed to take a collaborative approach to characterize and study hemangiomas and related tumors. Beginning with energetic, insightful pediatric dermatologists and little funding, they changed our knowledge base of how hemangiomas present, the risk factors for their development, and the characteristics and multiple organ findings associated with PHACE and other syndromic hemangiomas. Our knowledge of these lesions is now evidence based and broad, and the impact on care tremendous! The HIG has also influenced the practice of pediatricians and other specialists, including otorhinolaryngologists, hematologist/oncologists, and surgeons, is partnering with advocacy groups to support patients and families, and is helping guide patients and families to contribute to ongoing research.

Vascular malformations (VM) reflect an incredible change in our understanding of the developmental pathways and pathophysiology of blood vessel tumors, and, in fact, birthmarks other than vascular lesions! First, important work separated out hemangiomas of infancy and hemangiomalike tumors from vascular malformations, with the thought being that hemangiomas had a rapid growth phase, often arising from lesions that were minimally evident or not evident at birth, unlike malformations, which were “programing errors,” all present at birth and expected to be fairly static with proportionate growth over a lifetime. Approaches to vascular malformations were limited to sclerotherapy, laser, and/or surgery. While this general schema of classification is still useful, our sense of the “why and how” of vascular malformations is remarkably different. Vascular malformations – still usefully subdivided into capillary, lymphatic, venous arteriovenous, or mixed malformations – are mostly associated with inherited or somatic mutations. Mutations are most commonly found in two signal pathways: RAS/MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways, with specific sets of mutations seen in both localized and multifocal lesions, with or without overgrowth or other systemic anomalies. The discovery of specific mutations has led to the possibility of small-molecule inhibitors, many already existing as anticancer drugs, being utilized as targeted therapies for VM.

And similar advances in understanding of other birthmarks, with or without syndromic features, are being made steadily. The mutations in congenital melanocytic nevi, epidermal nevi, acquired tumors (pilomatricomas), and other lesions, along with steady epidemiologic, translational, and clinical work, evolves our knowledge and potential therapies.