User login

Cutaneous Sarcoidosis Presenting as a Cutaneous Horn

To the Editor:

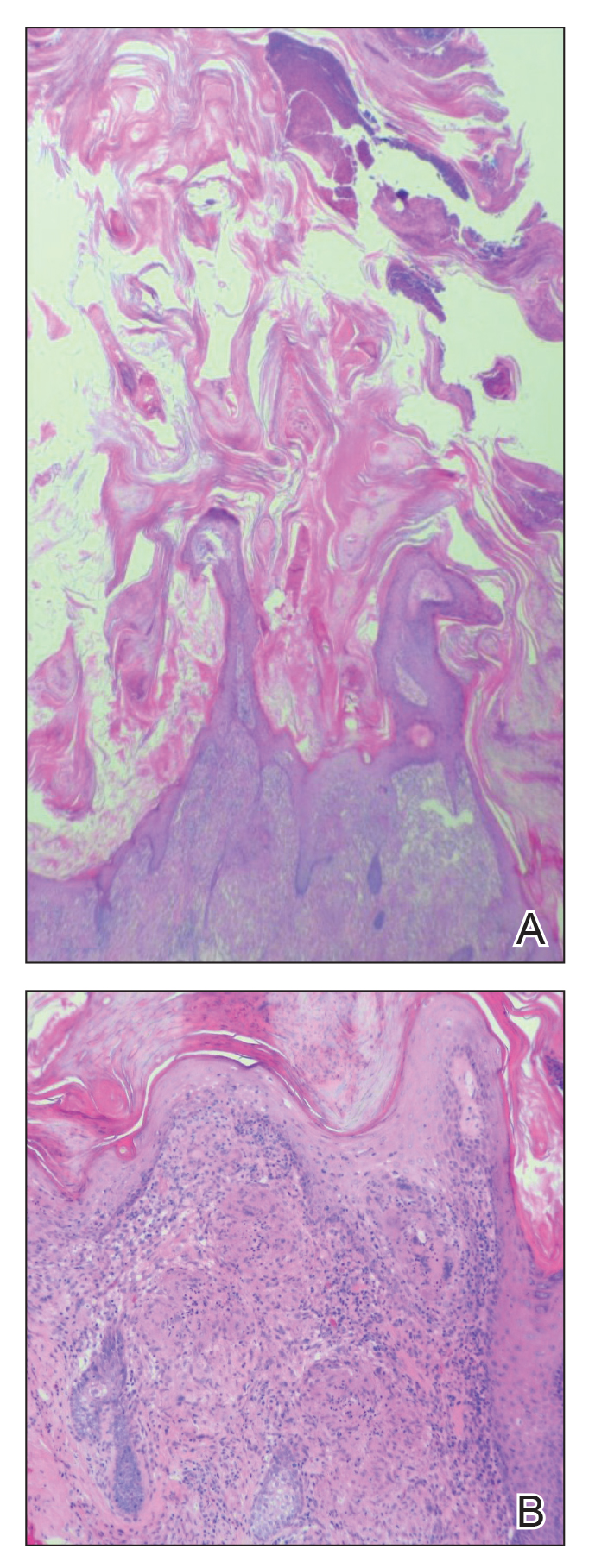

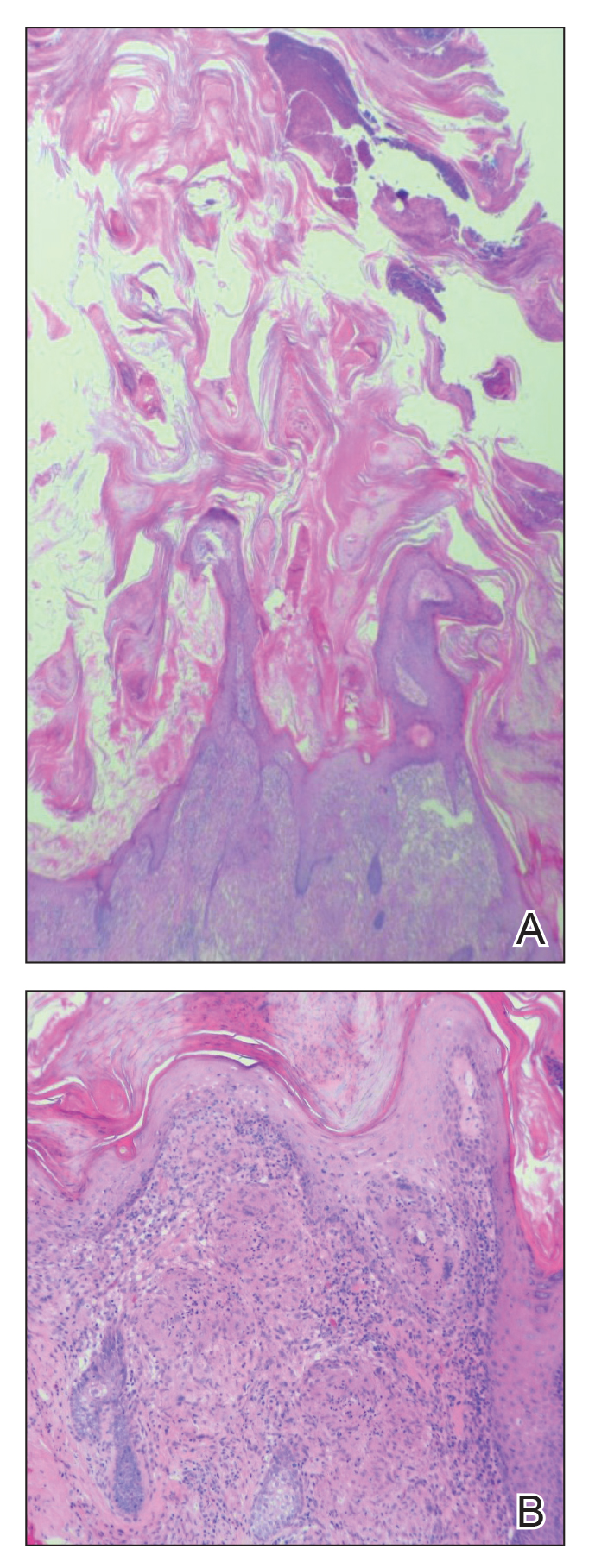

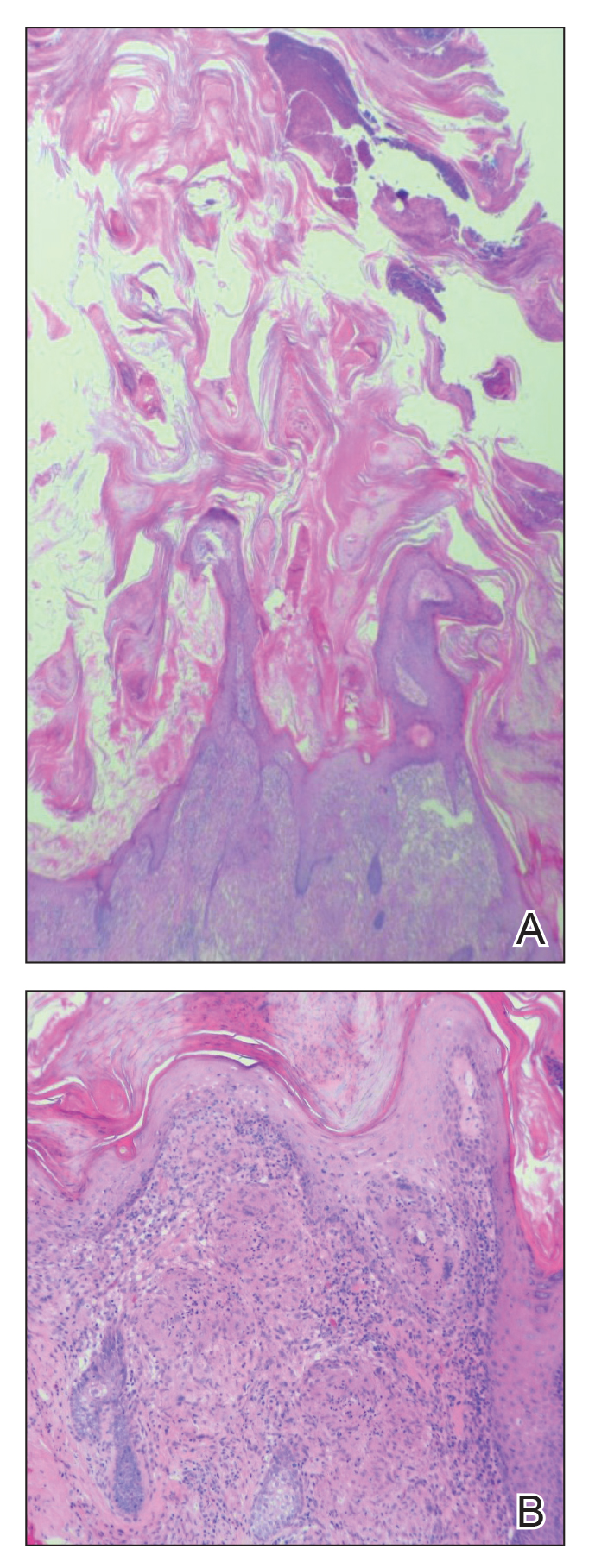

A 53-year-old woman presented to our dermatology clinic with a painful growth on the right ear of 2 months’ duration. A complete review of systems was negative except for an isolated episode of shortness of breath prior to presentation that resolved without intervention. During this episode, her primary care physician made a diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease based on a chest radiograph. The patient reported minimal tobacco use, specifically that she had smoked a few cigarettes daily for several years but had quit 6 months prior to the current presentation.

Cutaneous horn is a clinical term used to describe hyperkeratotic horn-shaped growths of highly variable shapes and sizes. Although the pathogenesis and incidence of cutaneous horns remain unknown, these lesions most often are the result of a neoplastic rather than an inflammatory process. The differential diagnosis typically includes entities characterized by marked hyperkeratosis, including hypertrophic actinic keratosis, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), seborrheic keratosis, and verruca vulgaris. The base of the horn must be biopsied to determine the underlying etiology, paying careful attention to avoid a superficial biopsy, as it may be nondiagnostic.

Studies analyzing the underlying diagnoses and clinical features of cutaneous horns are limited. In a large retrospective study of 643 cutaneous horns, 61% were benign, 23% were premalignant, and 16% were malignant. In this study, 4 features were associated with premalignant or malignant pathology: (1) older age (mid- 60s to 70s); (2) male sex; (3) location on the nose, pinnae, dorsal hands, scalp, forearms, or face; and (4) a wide base (4.4 mm or larger) and a lower height-to-base ratio than benign lesions.1 Two additional studies of more than 200 horns each showed higher rates of premalignant horns (42% and 38%, respectively) with malignancy found in 7% and 20% of horns, respectively.2,3 One prospective study sought to identify clinical and dermatoscopic features of SCCs underlying cutaneous horns, concluding that SCC diagnosis was more likely if a horn had (1) a height less than the diameter of its base, (2) a lack of terrace morphology (a dermatoscopic feature defined as horizontal parallel layers of keratin), (3) erythema at the base, and (4) the presence of pain.4

Our patient had a cutaneous horn on the pinna that was painful, wider than it was tall, and erythematous at the base, suggesting a malignant process; however, a complete cutaneous physical examination revealed other skin lesions that were concerning for sarcoidosis and raised suspicion that the horn also was a manifestation of the same inflammatory process.

Although unusual, cutaneous sarcoidosis presenting as a cutaneous horn is not unexpected. In a histopathologic study of 62 cases of cutaneous sarcoidosis, 79% (49/62) showed epidermal changes and 13% (8/62) demonstrated hyperkeratosis. Other epidermal changes included parakeratosis (16% [10/62]), acanthosis (10% [6/62]), and epidermal atrophy (57% [35/62]).5 The spectrum of epidermal pathology in cutaneous sarcoidosis is evident in its well-documented verrucous, psoriasiform, and ichthyosiform presentations. For completeness, cutaneous horn is added to the list of clinical morphologies for this “great imitator” of cutaneous diseases.

- Yu RC, Pryce DW, Macfarlane AW, et al. A histopathological study of 643 cutaneous horns. Br J Dermatol. 1991;124:449-452.

- Schosser RH, Hodge SJ, Gaba CR, et al. Cutaneous horns: a histopathologic study. South Med J. 1979;72:1129-1131.

- Mantese SA, Diogo PM, Rocha A, et al. Cutaneous horn: a retrospective histopathological study of 222 cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:157-163.

- Pyne J, Sapkota D, Wong JC. Cutaneous horns: clues to invasive squamous cell carcinoma being present in the horn base. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2013;3:3-7.

- Hiroyuki O. Epidermal changes in cutaneous lesions of sarcoidosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:229-233.

To the Editor:

A 53-year-old woman presented to our dermatology clinic with a painful growth on the right ear of 2 months’ duration. A complete review of systems was negative except for an isolated episode of shortness of breath prior to presentation that resolved without intervention. During this episode, her primary care physician made a diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease based on a chest radiograph. The patient reported minimal tobacco use, specifically that she had smoked a few cigarettes daily for several years but had quit 6 months prior to the current presentation.

Cutaneous horn is a clinical term used to describe hyperkeratotic horn-shaped growths of highly variable shapes and sizes. Although the pathogenesis and incidence of cutaneous horns remain unknown, these lesions most often are the result of a neoplastic rather than an inflammatory process. The differential diagnosis typically includes entities characterized by marked hyperkeratosis, including hypertrophic actinic keratosis, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), seborrheic keratosis, and verruca vulgaris. The base of the horn must be biopsied to determine the underlying etiology, paying careful attention to avoid a superficial biopsy, as it may be nondiagnostic.

Studies analyzing the underlying diagnoses and clinical features of cutaneous horns are limited. In a large retrospective study of 643 cutaneous horns, 61% were benign, 23% were premalignant, and 16% were malignant. In this study, 4 features were associated with premalignant or malignant pathology: (1) older age (mid- 60s to 70s); (2) male sex; (3) location on the nose, pinnae, dorsal hands, scalp, forearms, or face; and (4) a wide base (4.4 mm or larger) and a lower height-to-base ratio than benign lesions.1 Two additional studies of more than 200 horns each showed higher rates of premalignant horns (42% and 38%, respectively) with malignancy found in 7% and 20% of horns, respectively.2,3 One prospective study sought to identify clinical and dermatoscopic features of SCCs underlying cutaneous horns, concluding that SCC diagnosis was more likely if a horn had (1) a height less than the diameter of its base, (2) a lack of terrace morphology (a dermatoscopic feature defined as horizontal parallel layers of keratin), (3) erythema at the base, and (4) the presence of pain.4

Our patient had a cutaneous horn on the pinna that was painful, wider than it was tall, and erythematous at the base, suggesting a malignant process; however, a complete cutaneous physical examination revealed other skin lesions that were concerning for sarcoidosis and raised suspicion that the horn also was a manifestation of the same inflammatory process.

Although unusual, cutaneous sarcoidosis presenting as a cutaneous horn is not unexpected. In a histopathologic study of 62 cases of cutaneous sarcoidosis, 79% (49/62) showed epidermal changes and 13% (8/62) demonstrated hyperkeratosis. Other epidermal changes included parakeratosis (16% [10/62]), acanthosis (10% [6/62]), and epidermal atrophy (57% [35/62]).5 The spectrum of epidermal pathology in cutaneous sarcoidosis is evident in its well-documented verrucous, psoriasiform, and ichthyosiform presentations. For completeness, cutaneous horn is added to the list of clinical morphologies for this “great imitator” of cutaneous diseases.

To the Editor:

A 53-year-old woman presented to our dermatology clinic with a painful growth on the right ear of 2 months’ duration. A complete review of systems was negative except for an isolated episode of shortness of breath prior to presentation that resolved without intervention. During this episode, her primary care physician made a diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease based on a chest radiograph. The patient reported minimal tobacco use, specifically that she had smoked a few cigarettes daily for several years but had quit 6 months prior to the current presentation.

Cutaneous horn is a clinical term used to describe hyperkeratotic horn-shaped growths of highly variable shapes and sizes. Although the pathogenesis and incidence of cutaneous horns remain unknown, these lesions most often are the result of a neoplastic rather than an inflammatory process. The differential diagnosis typically includes entities characterized by marked hyperkeratosis, including hypertrophic actinic keratosis, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), seborrheic keratosis, and verruca vulgaris. The base of the horn must be biopsied to determine the underlying etiology, paying careful attention to avoid a superficial biopsy, as it may be nondiagnostic.

Studies analyzing the underlying diagnoses and clinical features of cutaneous horns are limited. In a large retrospective study of 643 cutaneous horns, 61% were benign, 23% were premalignant, and 16% were malignant. In this study, 4 features were associated with premalignant or malignant pathology: (1) older age (mid- 60s to 70s); (2) male sex; (3) location on the nose, pinnae, dorsal hands, scalp, forearms, or face; and (4) a wide base (4.4 mm or larger) and a lower height-to-base ratio than benign lesions.1 Two additional studies of more than 200 horns each showed higher rates of premalignant horns (42% and 38%, respectively) with malignancy found in 7% and 20% of horns, respectively.2,3 One prospective study sought to identify clinical and dermatoscopic features of SCCs underlying cutaneous horns, concluding that SCC diagnosis was more likely if a horn had (1) a height less than the diameter of its base, (2) a lack of terrace morphology (a dermatoscopic feature defined as horizontal parallel layers of keratin), (3) erythema at the base, and (4) the presence of pain.4

Our patient had a cutaneous horn on the pinna that was painful, wider than it was tall, and erythematous at the base, suggesting a malignant process; however, a complete cutaneous physical examination revealed other skin lesions that were concerning for sarcoidosis and raised suspicion that the horn also was a manifestation of the same inflammatory process.

Although unusual, cutaneous sarcoidosis presenting as a cutaneous horn is not unexpected. In a histopathologic study of 62 cases of cutaneous sarcoidosis, 79% (49/62) showed epidermal changes and 13% (8/62) demonstrated hyperkeratosis. Other epidermal changes included parakeratosis (16% [10/62]), acanthosis (10% [6/62]), and epidermal atrophy (57% [35/62]).5 The spectrum of epidermal pathology in cutaneous sarcoidosis is evident in its well-documented verrucous, psoriasiform, and ichthyosiform presentations. For completeness, cutaneous horn is added to the list of clinical morphologies for this “great imitator” of cutaneous diseases.

- Yu RC, Pryce DW, Macfarlane AW, et al. A histopathological study of 643 cutaneous horns. Br J Dermatol. 1991;124:449-452.

- Schosser RH, Hodge SJ, Gaba CR, et al. Cutaneous horns: a histopathologic study. South Med J. 1979;72:1129-1131.

- Mantese SA, Diogo PM, Rocha A, et al. Cutaneous horn: a retrospective histopathological study of 222 cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:157-163.

- Pyne J, Sapkota D, Wong JC. Cutaneous horns: clues to invasive squamous cell carcinoma being present in the horn base. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2013;3:3-7.

- Hiroyuki O. Epidermal changes in cutaneous lesions of sarcoidosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:229-233.

- Yu RC, Pryce DW, Macfarlane AW, et al. A histopathological study of 643 cutaneous horns. Br J Dermatol. 1991;124:449-452.

- Schosser RH, Hodge SJ, Gaba CR, et al. Cutaneous horns: a histopathologic study. South Med J. 1979;72:1129-1131.

- Mantese SA, Diogo PM, Rocha A, et al. Cutaneous horn: a retrospective histopathological study of 222 cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:157-163.

- Pyne J, Sapkota D, Wong JC. Cutaneous horns: clues to invasive squamous cell carcinoma being present in the horn base. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2013;3:3-7.

- Hiroyuki O. Epidermal changes in cutaneous lesions of sarcoidosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:229-233.

Practice Points

- Biopsy of a cutaneous horn should be deep enough to capture the neoplastic or inflammatory process at the base of the lesion.

- Cutaneous sarcoidosis can present with variable morphologies including the epidermal changes of a cutaneous horn.

Diffuse Nonscarring Alopecia

The Diagnosis: Trichotillomania

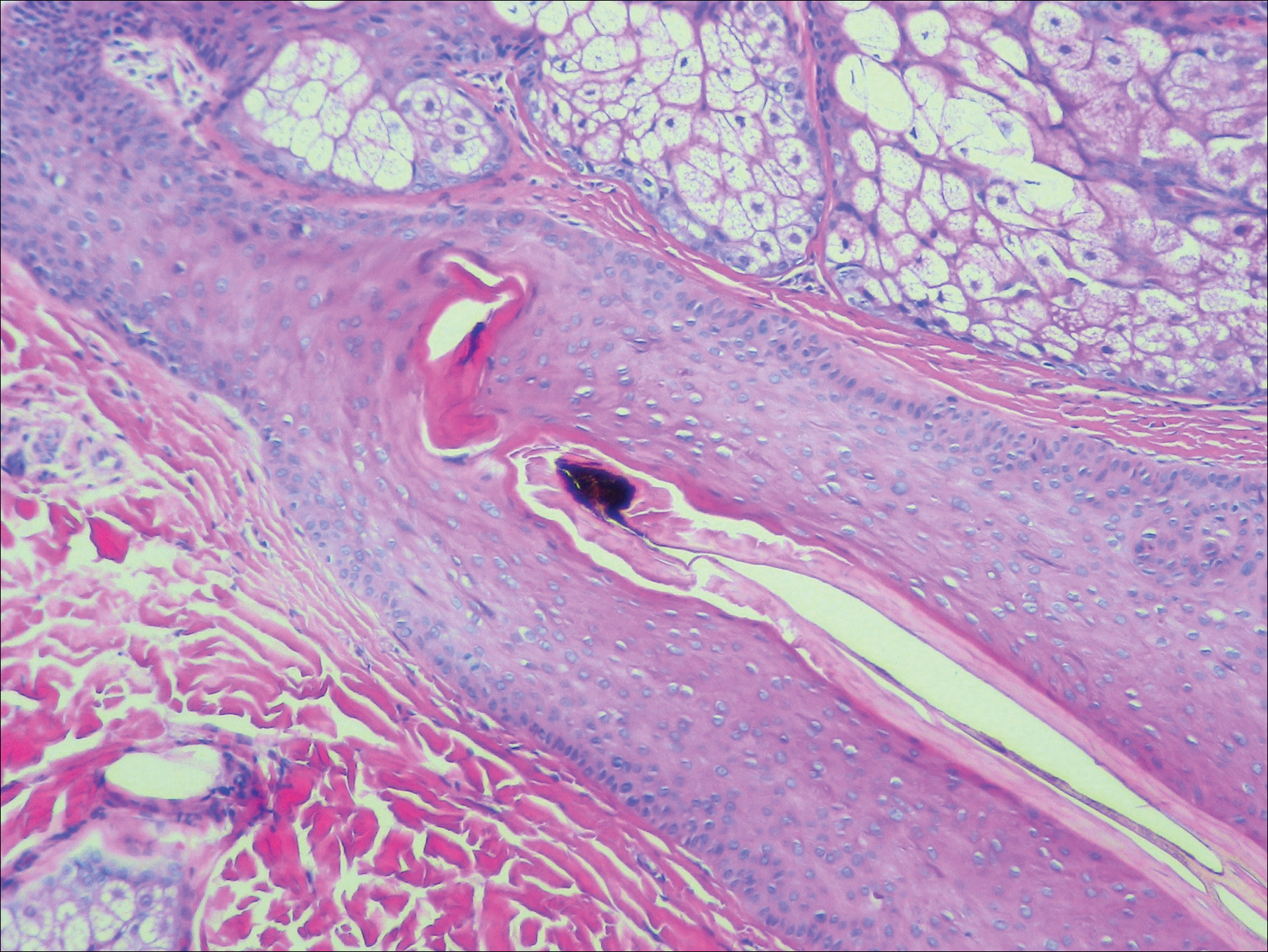

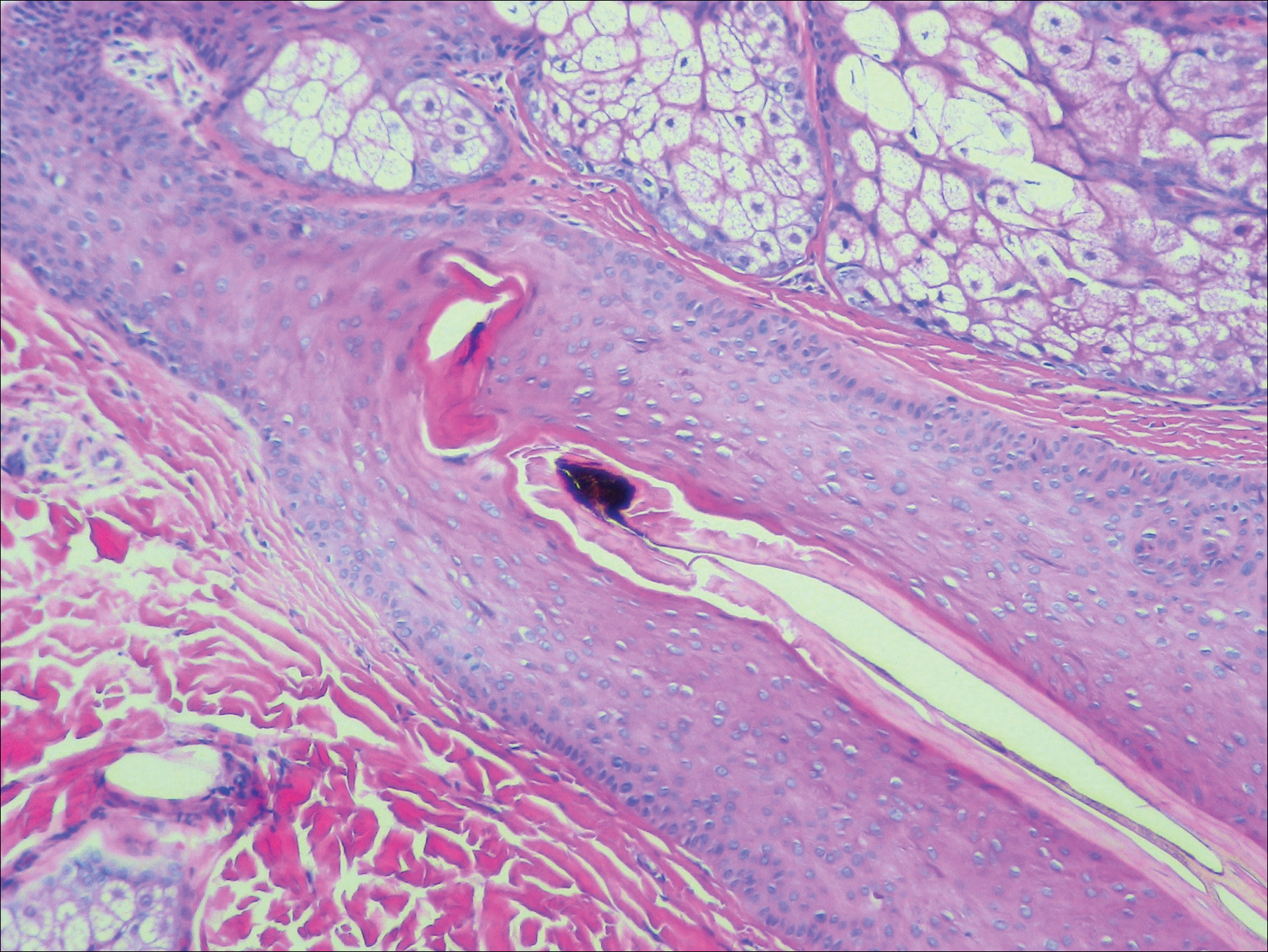

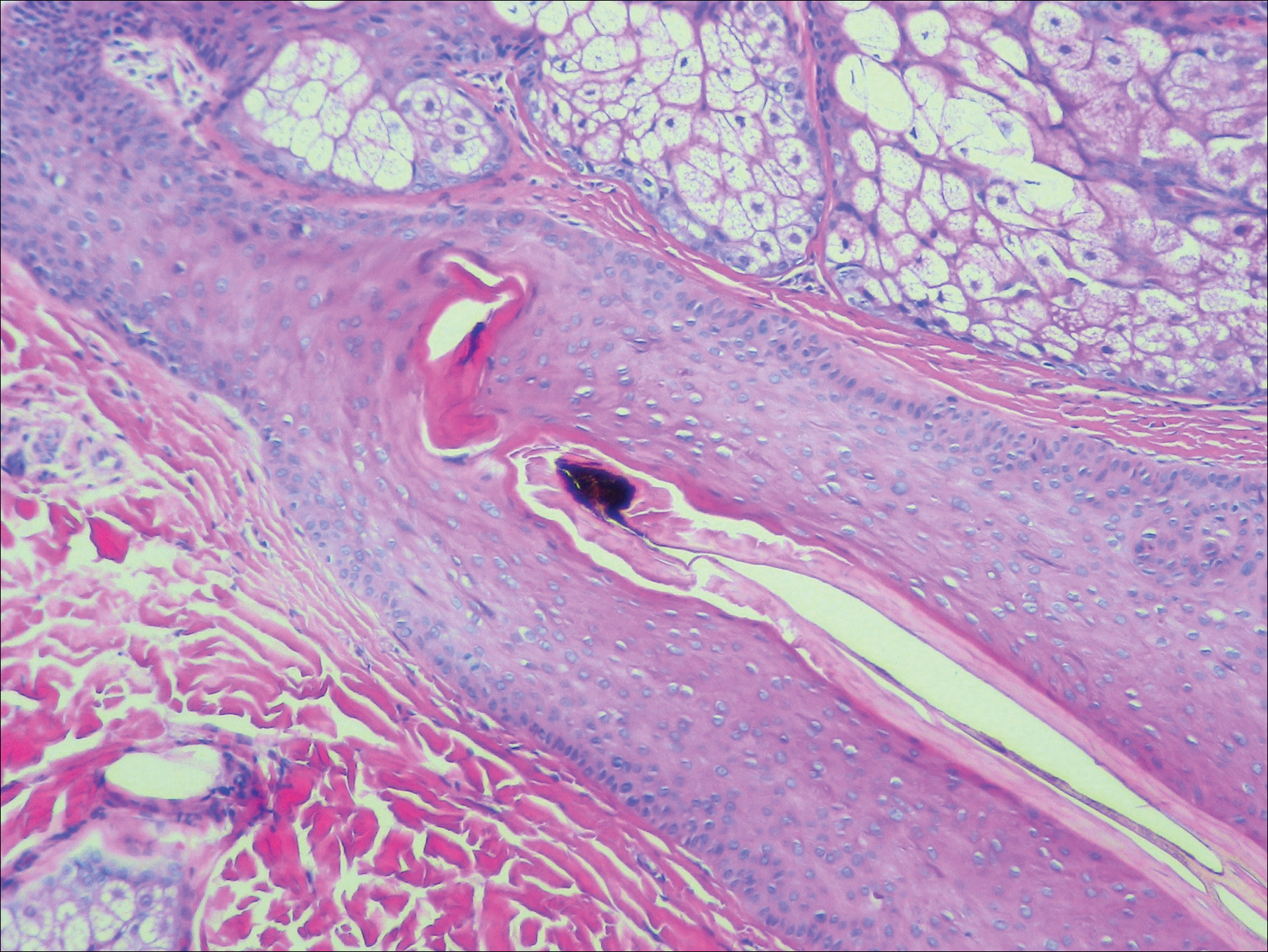

A scalp punch biopsy revealed pigmented hair casts, an increase in catagen and telogen follicles, and a lack of perifollicular inflammation (Figure). Based on the clinical and histopathological findings, a diagnosis of trichotillomania (TTM) was established.

Trichotillomania is a hairpulling disorder with notable dermatologic and psychiatric overlap. Although previously considered an impulse control disorder, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition) reclassified it within obsessive-compulsive and related disorders, which also include body dysmorphic disorder and excoriation (skin-picking) disorder. Diagnostic criteria for TTM include the following: the patient must have recurrent pulling out of his/her hair resulting in hair loss despite repeated attempts to stop; underlying medical conditions and other psychiatric diagnoses must be excluded; and the patient must experience distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other areas of functioning from the hairpulling.1 Trichotillomania mainly occurs in children and young adults, with a lifetime prevalence of approximately 1% to 2%.2 The coexistence of a mood or anxiety disorder is common, as seen in our patient.

The diagnosis of TTM requires strong clinical suspicion because patients and their parents/guardians usually deny hairpulling. The main clinical differential diagnosis often is alopecia areata (AA) because both conditions can present as well-defined patches of nonscarring hair loss. Trichoscopy provides an invaluable noninvasive diagnostic tool that can be particularly useful in pediatric patients who may be reluctant to have a scalp biopsy. There are many overlapping trichoscopic findings of TTM and AA, including yellow dots, black dots, broken hairs, coiled hairs, and exclamation mark hairs.3 More specific trichoscopy findings for TTM include flame hairs (wavy proximal hair residue), V-sign (2 shafts within 1 follicle broken at the same length), and tulip hairs (dark, tulip-shaped ends of broken hairs).4 Hair breakage of varying lengths and trichoptilosis (split ends) can be better visualized using trichoscopy and support a diagnosis of TTM over AA.

Androgenetic alopecia (female pattern hair loss) presents with gradual thinning around the part line of the frontal and parietal scalp with trichoscopy showing miniaturization of hairs and decreased follicle density. The moth-eaten-like appearance of alopecia due to secondary syphilis may mimic alopecia areata clinically, but serologic testing can confirm the diagnosis of syphilis. Telogen effluvium does not have the trichoscopic features that are seen in TTM and is clinically distinguished by hair shedding and a positive hair pull test.

Biopsy can provide objective yet nonspecific support for the diagnosis, demonstrating trichomalacia, pigmented hair casts, empty follicles, and an increase in catagen hairs with a lack of inflammation. Normal and damaged hair follicles may be seen in close proximity, and hemorrhage may be seen secondary to trauma. Pigmented hair casts are not specific to TTM and are present in other traumatic hair disorders, such as traction alopecia; therefore, clinical correlation is essential for diagnosis.

Habit reversal training is the most effective treatment of TTM and involves 3 major components: awareness training with self-monitoring, stimulus control, and competing response procedures.5 Although numerous pharmacotherapies have been reported as effective treatments for TTM, a 2013 Cochrane review of 8 randomized controlled trials concluded that no medication has demonstrated reliable efficacy. Reported therapies included selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, naltrexone, olanzapine, N-acetylcysteine, and clomipramine.6

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- Schumer MC, Panza KE, Mulqueen JM, et al. Long-term outcome in pediatric trichotillomania. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32:737-743.

- Lencastre A, Tosti A. Role of trichoscopy on children's scalp and hair disorders. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:674-682.

- Rakowska A, Slowinska M, Olszewska M, et al. New trichoscopy findings in trichotillomania: flame hairs, V-sign, hook hairs, hair powder, tulip hairs. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:303-306.

- Morris S, Zickgraf H, Dingfelder H, et al. Habit reversal training in trichotillomania: guide for the clinician. Expert Rev Neurother. 2013;13:1069-1177.

- Rothbart R, Amos T, Siegfried N, et al. Pharmacotherapy for trichotillomania. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;11:CD007662.

The Diagnosis: Trichotillomania

A scalp punch biopsy revealed pigmented hair casts, an increase in catagen and telogen follicles, and a lack of perifollicular inflammation (Figure). Based on the clinical and histopathological findings, a diagnosis of trichotillomania (TTM) was established.

Trichotillomania is a hairpulling disorder with notable dermatologic and psychiatric overlap. Although previously considered an impulse control disorder, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition) reclassified it within obsessive-compulsive and related disorders, which also include body dysmorphic disorder and excoriation (skin-picking) disorder. Diagnostic criteria for TTM include the following: the patient must have recurrent pulling out of his/her hair resulting in hair loss despite repeated attempts to stop; underlying medical conditions and other psychiatric diagnoses must be excluded; and the patient must experience distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other areas of functioning from the hairpulling.1 Trichotillomania mainly occurs in children and young adults, with a lifetime prevalence of approximately 1% to 2%.2 The coexistence of a mood or anxiety disorder is common, as seen in our patient.

The diagnosis of TTM requires strong clinical suspicion because patients and their parents/guardians usually deny hairpulling. The main clinical differential diagnosis often is alopecia areata (AA) because both conditions can present as well-defined patches of nonscarring hair loss. Trichoscopy provides an invaluable noninvasive diagnostic tool that can be particularly useful in pediatric patients who may be reluctant to have a scalp biopsy. There are many overlapping trichoscopic findings of TTM and AA, including yellow dots, black dots, broken hairs, coiled hairs, and exclamation mark hairs.3 More specific trichoscopy findings for TTM include flame hairs (wavy proximal hair residue), V-sign (2 shafts within 1 follicle broken at the same length), and tulip hairs (dark, tulip-shaped ends of broken hairs).4 Hair breakage of varying lengths and trichoptilosis (split ends) can be better visualized using trichoscopy and support a diagnosis of TTM over AA.

Androgenetic alopecia (female pattern hair loss) presents with gradual thinning around the part line of the frontal and parietal scalp with trichoscopy showing miniaturization of hairs and decreased follicle density. The moth-eaten-like appearance of alopecia due to secondary syphilis may mimic alopecia areata clinically, but serologic testing can confirm the diagnosis of syphilis. Telogen effluvium does not have the trichoscopic features that are seen in TTM and is clinically distinguished by hair shedding and a positive hair pull test.

Biopsy can provide objective yet nonspecific support for the diagnosis, demonstrating trichomalacia, pigmented hair casts, empty follicles, and an increase in catagen hairs with a lack of inflammation. Normal and damaged hair follicles may be seen in close proximity, and hemorrhage may be seen secondary to trauma. Pigmented hair casts are not specific to TTM and are present in other traumatic hair disorders, such as traction alopecia; therefore, clinical correlation is essential for diagnosis.

Habit reversal training is the most effective treatment of TTM and involves 3 major components: awareness training with self-monitoring, stimulus control, and competing response procedures.5 Although numerous pharmacotherapies have been reported as effective treatments for TTM, a 2013 Cochrane review of 8 randomized controlled trials concluded that no medication has demonstrated reliable efficacy. Reported therapies included selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, naltrexone, olanzapine, N-acetylcysteine, and clomipramine.6

The Diagnosis: Trichotillomania

A scalp punch biopsy revealed pigmented hair casts, an increase in catagen and telogen follicles, and a lack of perifollicular inflammation (Figure). Based on the clinical and histopathological findings, a diagnosis of trichotillomania (TTM) was established.

Trichotillomania is a hairpulling disorder with notable dermatologic and psychiatric overlap. Although previously considered an impulse control disorder, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition) reclassified it within obsessive-compulsive and related disorders, which also include body dysmorphic disorder and excoriation (skin-picking) disorder. Diagnostic criteria for TTM include the following: the patient must have recurrent pulling out of his/her hair resulting in hair loss despite repeated attempts to stop; underlying medical conditions and other psychiatric diagnoses must be excluded; and the patient must experience distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other areas of functioning from the hairpulling.1 Trichotillomania mainly occurs in children and young adults, with a lifetime prevalence of approximately 1% to 2%.2 The coexistence of a mood or anxiety disorder is common, as seen in our patient.

The diagnosis of TTM requires strong clinical suspicion because patients and their parents/guardians usually deny hairpulling. The main clinical differential diagnosis often is alopecia areata (AA) because both conditions can present as well-defined patches of nonscarring hair loss. Trichoscopy provides an invaluable noninvasive diagnostic tool that can be particularly useful in pediatric patients who may be reluctant to have a scalp biopsy. There are many overlapping trichoscopic findings of TTM and AA, including yellow dots, black dots, broken hairs, coiled hairs, and exclamation mark hairs.3 More specific trichoscopy findings for TTM include flame hairs (wavy proximal hair residue), V-sign (2 shafts within 1 follicle broken at the same length), and tulip hairs (dark, tulip-shaped ends of broken hairs).4 Hair breakage of varying lengths and trichoptilosis (split ends) can be better visualized using trichoscopy and support a diagnosis of TTM over AA.

Androgenetic alopecia (female pattern hair loss) presents with gradual thinning around the part line of the frontal and parietal scalp with trichoscopy showing miniaturization of hairs and decreased follicle density. The moth-eaten-like appearance of alopecia due to secondary syphilis may mimic alopecia areata clinically, but serologic testing can confirm the diagnosis of syphilis. Telogen effluvium does not have the trichoscopic features that are seen in TTM and is clinically distinguished by hair shedding and a positive hair pull test.

Biopsy can provide objective yet nonspecific support for the diagnosis, demonstrating trichomalacia, pigmented hair casts, empty follicles, and an increase in catagen hairs with a lack of inflammation. Normal and damaged hair follicles may be seen in close proximity, and hemorrhage may be seen secondary to trauma. Pigmented hair casts are not specific to TTM and are present in other traumatic hair disorders, such as traction alopecia; therefore, clinical correlation is essential for diagnosis.

Habit reversal training is the most effective treatment of TTM and involves 3 major components: awareness training with self-monitoring, stimulus control, and competing response procedures.5 Although numerous pharmacotherapies have been reported as effective treatments for TTM, a 2013 Cochrane review of 8 randomized controlled trials concluded that no medication has demonstrated reliable efficacy. Reported therapies included selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, naltrexone, olanzapine, N-acetylcysteine, and clomipramine.6

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- Schumer MC, Panza KE, Mulqueen JM, et al. Long-term outcome in pediatric trichotillomania. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32:737-743.

- Lencastre A, Tosti A. Role of trichoscopy on children's scalp and hair disorders. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:674-682.

- Rakowska A, Slowinska M, Olszewska M, et al. New trichoscopy findings in trichotillomania: flame hairs, V-sign, hook hairs, hair powder, tulip hairs. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:303-306.

- Morris S, Zickgraf H, Dingfelder H, et al. Habit reversal training in trichotillomania: guide for the clinician. Expert Rev Neurother. 2013;13:1069-1177.

- Rothbart R, Amos T, Siegfried N, et al. Pharmacotherapy for trichotillomania. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;11:CD007662.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- Schumer MC, Panza KE, Mulqueen JM, et al. Long-term outcome in pediatric trichotillomania. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32:737-743.

- Lencastre A, Tosti A. Role of trichoscopy on children's scalp and hair disorders. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:674-682.

- Rakowska A, Slowinska M, Olszewska M, et al. New trichoscopy findings in trichotillomania: flame hairs, V-sign, hook hairs, hair powder, tulip hairs. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:303-306.

- Morris S, Zickgraf H, Dingfelder H, et al. Habit reversal training in trichotillomania: guide for the clinician. Expert Rev Neurother. 2013;13:1069-1177.

- Rothbart R, Amos T, Siegfried N, et al. Pharmacotherapy for trichotillomania. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;11:CD007662.

A 19-year-old woman with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and an anxiety disorder presented with hair loss of 2 years' duration. She initially had small circular bald areas throughout the scalp that had progressed to diffuse hair loss of the entire scalp. She denied recent hairpulling but admitted to a remote prior history of eyelash and eyebrow pulling. She denied any voice changes, acne, or menstrual irregularities. Physical examination revealed short hairs of varying lengths throughout the scalp with no loss of follicles, erythema, scale, or exclamation point hairs. Eyebrows and eyelashes were normal. A hair-pull test was negative. Trichoscopy illuminated variation in hair shaft diameters, as well as short, irregularly broken hairs of different lengths (inset).