User login

Frequently Hospitalized Patients’ Perceptions of Factors Contributing to High Hospital Use

In recent years, hospitals have made considerable efforts to improve transitions of care, in part due to financial incentives from the Medicare Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP).1 Initially focusing on three medical conditions, the HRRP has been associated with significant reductions in readmission rates.2 Importantly, a small proportion of patients accounts for a very large proportion of hospital readmissions and hospital use.3,4 Frequently hospitalized patients often have multiple chronic conditions and unique needs which may not be met by conventional approaches to healthcare delivery, including those influenced by the HRRP.4-6 In light of this challenge, some hospitals have developed programs specifically focused on frequently hospitalized patients. A recent systematic review of these programs found relatively few studies of high quality, providing only limited insight in designing interventions to support this population.7 Moreover, no studies appear to have incorporated the patients’ perspectives into the design or adaptation of the model. Members of our research team developed and implemented the Complex High Admission Management Program (CHAMP) in January 2016 to address the needs of frequently hospitalized patients in our hospital. To enhance CHAMP and inform the design of programs serving similar populations in other health systems, we sought to identify factors associated with the onset and continuation of high hospital use. Our research question was, from the patients’ perspective, what factors contribute to patients’ becoming and continuing to be high users of hospital care.

METHODS

Setting, Study Design, and Participants

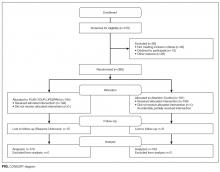

This qualitative study took place at Northwestern Memorial Hospital (NMH), an 894-bed urban academic hospital located in Chicago, Illinois. Between December 2016 and September 2017, we recruited adult patients admitted to the general medicine services. Eligible participants were identified with the assistance of a daily Northwestern Medicine Electronic Data Warehouse (EDW) search and included patients with two unplanned 30-day inpatient readmissions to NMH within the prior 12 months, in addition to one or more of the following criteria: (1) at least one readmission in the last six months; (2) a referral from one of the patient’s medical providers; or (3) at least three observation visits. We excluded patients whose preferred language was not English and those disoriented to person, place, or time. Considering NMH data showing that approximately one-third of high-utilizer patients have sickle cell disease, we used purposive sampling with the goal to compare findings within and between two groups of participants; those with and those without sickle cell disease. Our study was deemed exempt by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board.

Participant Enrollment and Data Collection

We created an interview guide based on the research team’s experience with this population, a literature review, and our research question (See Appendix).8,9 A research coordinator approached eligible participants during their hospital stay. The coordinator explained the study to eligible participants and obtained verbal consent for participation. The research coordinator then conducted one-on-one semi-structured interviews. Interviews were audio recorded for subsequent transcription and coding. Each interview lasted approximately 45 minutes. Participants were compensated with a $20 gift card for their time.

Analysis

Digital audio recordings from interviews were transcribed verbatim, deidentified, and analyzed using an iterative inductive team-based approach to coding.10 In our first cycle coding, all coders (KJO, SF, MMC, LO, KAC) independently reviewed and coded three transcripts using descriptive coding and subcoding to generate a preliminary codebook with code definitions.10,11 Following the meetings to compare and compile our initial coding, each researcher then independently recoded the three transcripts with the developed codebook. The researchers met again to triangulate perspectives and reach a consensus on the final codebook. Using multiple coders is a standard process to control for subjective bias that one coder could bring to the coding process.12 Following this meeting, the coders split into two teams of two (KJO, SF, and MMC, LO) to complete the coding of the remaining transcripts. Each team member independently coded the assigned transcripts and reconciled their codes with their counterpart; any discrepancies were resolved through discussion. Using this strategy, every transcript was coded by at least two team members. Our second coding cycle utilized pattern coding and involved identifying consistency both within and between transcripts; discovering associations between codes.10,11,13 Constant comparison was used to compare responses among all participants, as well as between sickle-cell and nonsickle-cell participants.13,14 Following team coding and reconciling, the analyses were presented to a broader research team for additional feedback and critique. All analyses were conducted using Dedoose version 8.0.35 (Los Angeles, California). Participant recruitment, interviews, and analysis of the transcripts continued until no new codes emerged and thematic saturation was achieved.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Overall, we invited 34 patients to be interviewed; 26 consented and completed interviews (76.5%). Six (17.6%) patients declined participation, one (2.9%) was unable to complete the interview before hospital discharge, and one (2.9%) was excluded due to disorientation. Demographic characteristics of the 26 participants are shown in Table 1.

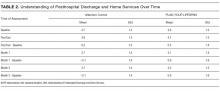

Four main themes emerged from our analysis. Table 2 summarizes these themes, subthemes, and provides representative quotes.

Major Medical Problem(s) are Universal, but High Hospital Use Varies in Onset

Not surprisingly, all participants described having at least one major medical problem. Some participants, such as those with genetic disorders, had experienced periods of high hospital use throughout their entire lifetime, while other participants experienced an onset of high hospital use as an adult after being previously healthy. Though most participants with genetic disorders had sickle cell anemia; one had a rare genetic disorder which caused chronic gastrointestinal symptoms. Participants typically described having a significant medical condition as well as other medical problems or complications from past surgery. Some participants described having a major medical problem which did not require frequent hospitalization until a complication or other medical problem arose, suggesting these new issues pushed them over a threshold beyond which self-management at home was less successful.

Course Fluctuates over Time and is Related to Psychological, Social, and Economic Factors

Participants identified psychological stress, social support, and financial constraints as factors which influence the course of their illness over time. Deaths in the family, breakups, and concerns about other family members were mentioned as specific forms of psychological stress and directly linked by participants to worsening of symptoms. Social support was present for most, but not all, participants, with no appreciable difference based on whether the participant had sickle cell disease. Social support was generally perceived as helpful, and several participants indicated a benefit to their own health when providing social support to others. Financial pressures also served as stressors and often impeded care due to lack of access to medications, other treatments, and housing.

Onset and Progression of Episodes Vary, but Generally Seem Uncontrollable

Regarding the onset of illness episodes, some participants described the sudden, unpredictable onset of symptoms, others described a more gradual onset which allowed them to attempt self-management. Regardless of the timing, episodes of illness were often perceived as spontaneous or triggered by factors outside of the participant’s control. Several participants, especially those with sickle cell disease, mentioned a relationship between their symptoms and the weather. Participants also noted the inconsistency in factors which may trigger an episode (ie, sometimes the factor exacerbated symptoms, while other times it did not). Participants also described having a high symptom burden with significant limitations in activities of daily living during episodes of illness. Pain was a very common component of symptoms regardless of whether or not the participant had sickle cell disease.

Individuals Seek Care after Self-Management Fails and Prefer to Avoid Hospitalization

Participants tried to control their symptoms with medications and typically sought care only when it was clear that this approach was not working, or they ran out of medications. This finding was consistent across both groups of participants (ie, those with and those without sickle cell disease). Many participants described very strong preferences not to come to the hospital; no participant described being in the hospital as a favorable or positive experience. Some participants mentioned that they had spent major holidays in the hospital and that they missed their family. No participant had a desire to come to the hospital.

DISCUSSION

In this study of frequently hospitalized patients, we found four major themes that illuminate patient perspectives about factors that contribute to high hospital use. While some of our findings corroborate those of previous studies, other emerging patterns were novel. Herein, we summarize key findings, provide context, and describe implications for the design of models of care for frequently hospitalized patients.

Similar to the findings of previous quantitative research, participants in our study described having a significant medical condition and typically had multiple medical conditions or complications.4-6 Importantly, some participants described having a major medical problem which did not require frequent hospitalization until another medical problem or complication arose. This finding suggests that there may be an opportunity to identify patients with significant medical problems who are at elevated risk before the onset of high hospital use. Early identification of these high-risk patients could allow for the provision of additional support to prevent potential complications or address other factors which may contribute to the need for frequent hospitalization.

Participants in our study directly linked psychological stress to fluctuations in their course of illness. Previous research by Mautner and colleagues queried participants about childhood experiences and early life stressors and reported that early life instabilities and traumas were prevalent among patients with high levels of emergency and hospital-based healthcare utilization.15 Our participants identified more recent traumatic events (eg, the death of a loved one and breakups) when reflecting on factors contributing to illness exacerbations; early life trauma did not emerge as an identified contributor. Of note, unlike Mautner et al., we did not ask participants to reflect on childhood determinants of disease and illness specifically. Our findings suggest that psychological stress contributes to illness exacerbation, even for those patients without other significant psychiatric conditions (eg, depressive disorder, schizophrenia). Incorporating mental health professionals into programs for this patient population may improve health by teaching specific coping strategies, including cognitive-behavioral therapy for an acute stress disorder.16,17

Social support was also a factor related to illness fluctuations over time. Notably, several participants indicated a benefit to their own health when providing social support to others, suggesting a role for peer support that may be reciprocally beneficial. This approach is supported by the literature. Williams and colleagues found that patients with sickle cell anemia experienced symptom improvement with peer support;18 while Johnson and colleagues recently reported a reduction in readmissions to acute care with the use of peer support for patients with severe mental illness.19

Financial constraints impeded care for some patients and served as a barrier to accessing medications, other treatments, and housing. Similar to the findings of prior quantitative research, our frequently hospitalized patients had a high proportion of patients with Medicaid and low proportion with private insurance, suggesting low socioeconomic status.9,20 We did not formally collect data on income or economic status. Interestingly, prior qualitative studies have not identified financial constraints as a major theme, though this may be explained by differences in study populations and the overall objectives of the studies.15,21 Importantly, the overwhelming majority of programs for frequently hospitalized patients identified in a recent systematic review included social workers.7 Our findings support the need to address financial constraints and the use of social workers in models of care for frequently hospitalized patients.

Many participants in our study felt that the factors contributing to exacerbations of illness were either inconsistent in their effect or out of their control. These findings have similarities to those from a qualitative study by Liu and colleagues in which they interviewed 20 “hospital-dependent” patients over 65 years of age.21 Though not explicitly focused on factors contributing to exacerbations, participants in their study felt that hospitalizations were generally inevitable. In our study, participants with sickle cell disease often identified changes in the weather as contributing to illness exacerbations. The relationship between weather and sickle cell disease remains incompletely understood, with an inconsistent association found in prior studies.22

Participants in our study strongly desired to avoid hospitalization and typically sought hospital care when symptoms could not be controlled at home. This finding is in contrast to that from the study by Liu and colleagues where they found that hospital-dependent patients over 65 years had favorable perspectives of hospitalization because they felt safer and more secure in the hospital.21 Our participants were younger than those from the study by Liu and colleagues, had a high symptom burden, and may have been more concerned about control of those symptoms than the risk for clinical deterioration. Programs should aim to strengthen their support of patients’ self-management efforts early in the episode of illness and potentially offer home visits or a day hospital to avoid hospitalization. A recent systematic review found evidence that alternatives to inpatient care (eg, hospital-at-home) for low risk medical patients can achieve comparable outcomes at lower costs.23 Similarly, some health systems have implemented day hospitals to treat low risk patients with uncomplicated sickle cell pain.24,25

The heavy symptom burden experienced by participants in our study is notable. Pain was especially common. Programs may wish to partner with palliative care and addiction specialists to balance symptom relief with the simultaneous need to address comorbid substance and opioid use disorders when they are present.4,9

Our study has several limitations. First, participants were recruited from the medicine service at a single academic hospital using criteria we developed to identify frequently hospitalized patients. Populations differ across hospitals and definitions of frequently hospitalized patients vary, limiting the generalizability of our findings. Second, we excluded patients whose preferred language was not English, as well as those disoriented to person, place, or time. It is possible that factors contributing to high hospital use differ for non-English speaking patients and those with cognitive deficits.

CONCLUSION

In this qualitative study, we identified factors associated with the onset and continuation of high hospital use. Emergent themes pointed to factors which influence patients’ onset of high hospital use, fluctuations in their illness over time, and triggers to seek care during an illness episode. These findings represent an important contribution to the literature because they allow patients’ perspectives to be incorporated into the design and adaptation of programs serving similar populations in other health systems. Programs that integrate patients’ perspectives into their design are likely to be better prepared to address patients’ needs and improve patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants for their time and willingness to share their stories. The authors also thank Claire A. Knoten PhD and Erin Lambers PhD, former research team members who helped in the initial stages of the study.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This project was funded by Northwestern Memorial Hospital and the Northwestern Medical Group.

1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Readmissions Reduction Program. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program.html. Accessed September 17, 2018.

2. Wasfy JH, Zigler CM, Choirat C, Wang Y, Dominici F, Yeh RW. Readmission rates after passage of the hospital readmissions reduction program: a pre-post analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2016;166(5):324-331. https://doi.org/10.7326/m16-0185.

3. Blumenthal D, Chernof B, Fulmer T, Lumpkin J, Selberg J. Caring for high-need, high-cost patients-an urgent priority. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(10):909-911. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp1608511.

4. Szekendi MK, Williams MV, Carrier D, Hensley L, Thomas S, Cerese J. The characteristics of patients frequently admitted to academic medical centers in the United States. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(9):563-568. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2375.

5. Dastidar JG, Jiang M. Characterization, categorization, and 5-year mortality of medicine high utilizer inpatients. J Palliat Care. 2018;33(3):167-174. https://doi.org/10.1177/0825859718769095.

6. Mudge AM, Kasper K, Clair A, et al. Recurrent readmissions in medical patients: a prospective study. J Hosp Med. 2010;6(2):61-67. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.811.

7. Goodwin A, Henschen BL, Odwyer LC, Nichols N, Oleary KJ. Interventions for frequently hospitalized patients and their effect on outcomes: a systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(12):853-859. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3090.

8. Gelberg L, Andersen RM, Leake BD. The behavioral model for vulnerable populations: application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Serv Res. 2000;34(6):1273-1302. PubMed

9. Rinehart DJ, Oronce C, Durfee MJ, et al. Identifying subgroups of adult superutilizers in an urban safety-net system using latent class analysis. Med Care. 2018;56(1):e1-e9. https://doi.org/10.1097/mlr.0000000000000628.

10. Miles MB, Huberman M, Saldana J. Qualitative Data Analysis. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications; 2014.

11. Saldana J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE publications; 2013.

12. Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. 1 ed. Beverly Hills, California: SAGE Publications; 1985.

13. Kolb SM. Grounded theory and the constant comparative method: valid research strategies for educators. J Emerging Trends Educ Res Policy Stud. 2012;3(1):83-86.

14. Glasser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. New York: Taylor and Francis Group; 2017.

15. Mautner DB, Pang H, Brenner JC, et al. Generating hypotheses about care needs of high utilizers: lessons from patient interviews. Popul Health Manag. 2013;16(Suppl 1):S26-S33. https://doi.org/10.1089/pop.2013.0033.

16. Carpenter JK, Andrews LA, Witcraft SM, Powers MB, Smits JAJ, Hofmann SG. Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and related disorders: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Depres Anxiety. 2018;35(6):502-514. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22728.

17. Roberts NP, Kitchiner NJ, Kenardy J, Bisson JI. Systematic review and meta-analysis of multiple-session early interventions following traumatic events. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(3):293-301. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08040590.

18. Williams H, Tanabe P. Sickle cell disease: a review of nonpharmacological approaches for pain. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2016;51(2):163-177. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.10.017.

19. Johnson S, Lamb D, Marston L, et al. Peer-supported self-management for people discharged from a mental health crisis team: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;392(10145):409-418.https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)31470-3.

20. Mercer T, Bae J, Kipnes J, Velazquez M, Thomas S, Setji N. The highest utilizers of care: individualized care plans to coordinate care, improve healthcare service utilization, and reduce costs at an academic tertiary care center. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(7):419-424. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2351.

21. Liu T, Kiwak E, Tinetti ME. Perceptions of hospital-dependent patients on their needs for hospitalization. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(6):450-453. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2756.

22. Piel FB, Steinberg MH, Rees DC. Sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(16):1561-1573. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmra1510865.

23. Conley J, O’Brien CW, Leff BA, Bolen S, Zulman D. Alternative strategies to inpatient hospitalization for acute medical conditions: a systematic review. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(11):1693-1702. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5974.

24. Adewoye AH, Nolan V, McMahon L, Ma Q, Steinberg MH. Effectiveness of a dedicated day hospital for management of acute sickle cell pain. Haematologica. 2007;92(6):854-855. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.10757.

25. Benjamin LJ, Swinson GI, Nagel RL. Sickle cell anemia day hospital: an approach for the management of uncomplicated painful crises. Blood. 2000;95(4):1130-1136. PubMed

In recent years, hospitals have made considerable efforts to improve transitions of care, in part due to financial incentives from the Medicare Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP).1 Initially focusing on three medical conditions, the HRRP has been associated with significant reductions in readmission rates.2 Importantly, a small proportion of patients accounts for a very large proportion of hospital readmissions and hospital use.3,4 Frequently hospitalized patients often have multiple chronic conditions and unique needs which may not be met by conventional approaches to healthcare delivery, including those influenced by the HRRP.4-6 In light of this challenge, some hospitals have developed programs specifically focused on frequently hospitalized patients. A recent systematic review of these programs found relatively few studies of high quality, providing only limited insight in designing interventions to support this population.7 Moreover, no studies appear to have incorporated the patients’ perspectives into the design or adaptation of the model. Members of our research team developed and implemented the Complex High Admission Management Program (CHAMP) in January 2016 to address the needs of frequently hospitalized patients in our hospital. To enhance CHAMP and inform the design of programs serving similar populations in other health systems, we sought to identify factors associated with the onset and continuation of high hospital use. Our research question was, from the patients’ perspective, what factors contribute to patients’ becoming and continuing to be high users of hospital care.

METHODS

Setting, Study Design, and Participants

This qualitative study took place at Northwestern Memorial Hospital (NMH), an 894-bed urban academic hospital located in Chicago, Illinois. Between December 2016 and September 2017, we recruited adult patients admitted to the general medicine services. Eligible participants were identified with the assistance of a daily Northwestern Medicine Electronic Data Warehouse (EDW) search and included patients with two unplanned 30-day inpatient readmissions to NMH within the prior 12 months, in addition to one or more of the following criteria: (1) at least one readmission in the last six months; (2) a referral from one of the patient’s medical providers; or (3) at least three observation visits. We excluded patients whose preferred language was not English and those disoriented to person, place, or time. Considering NMH data showing that approximately one-third of high-utilizer patients have sickle cell disease, we used purposive sampling with the goal to compare findings within and between two groups of participants; those with and those without sickle cell disease. Our study was deemed exempt by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board.

Participant Enrollment and Data Collection

We created an interview guide based on the research team’s experience with this population, a literature review, and our research question (See Appendix).8,9 A research coordinator approached eligible participants during their hospital stay. The coordinator explained the study to eligible participants and obtained verbal consent for participation. The research coordinator then conducted one-on-one semi-structured interviews. Interviews were audio recorded for subsequent transcription and coding. Each interview lasted approximately 45 minutes. Participants were compensated with a $20 gift card for their time.

Analysis

Digital audio recordings from interviews were transcribed verbatim, deidentified, and analyzed using an iterative inductive team-based approach to coding.10 In our first cycle coding, all coders (KJO, SF, MMC, LO, KAC) independently reviewed and coded three transcripts using descriptive coding and subcoding to generate a preliminary codebook with code definitions.10,11 Following the meetings to compare and compile our initial coding, each researcher then independently recoded the three transcripts with the developed codebook. The researchers met again to triangulate perspectives and reach a consensus on the final codebook. Using multiple coders is a standard process to control for subjective bias that one coder could bring to the coding process.12 Following this meeting, the coders split into two teams of two (KJO, SF, and MMC, LO) to complete the coding of the remaining transcripts. Each team member independently coded the assigned transcripts and reconciled their codes with their counterpart; any discrepancies were resolved through discussion. Using this strategy, every transcript was coded by at least two team members. Our second coding cycle utilized pattern coding and involved identifying consistency both within and between transcripts; discovering associations between codes.10,11,13 Constant comparison was used to compare responses among all participants, as well as between sickle-cell and nonsickle-cell participants.13,14 Following team coding and reconciling, the analyses were presented to a broader research team for additional feedback and critique. All analyses were conducted using Dedoose version 8.0.35 (Los Angeles, California). Participant recruitment, interviews, and analysis of the transcripts continued until no new codes emerged and thematic saturation was achieved.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Overall, we invited 34 patients to be interviewed; 26 consented and completed interviews (76.5%). Six (17.6%) patients declined participation, one (2.9%) was unable to complete the interview before hospital discharge, and one (2.9%) was excluded due to disorientation. Demographic characteristics of the 26 participants are shown in Table 1.

Four main themes emerged from our analysis. Table 2 summarizes these themes, subthemes, and provides representative quotes.

Major Medical Problem(s) are Universal, but High Hospital Use Varies in Onset

Not surprisingly, all participants described having at least one major medical problem. Some participants, such as those with genetic disorders, had experienced periods of high hospital use throughout their entire lifetime, while other participants experienced an onset of high hospital use as an adult after being previously healthy. Though most participants with genetic disorders had sickle cell anemia; one had a rare genetic disorder which caused chronic gastrointestinal symptoms. Participants typically described having a significant medical condition as well as other medical problems or complications from past surgery. Some participants described having a major medical problem which did not require frequent hospitalization until a complication or other medical problem arose, suggesting these new issues pushed them over a threshold beyond which self-management at home was less successful.

Course Fluctuates over Time and is Related to Psychological, Social, and Economic Factors

Participants identified psychological stress, social support, and financial constraints as factors which influence the course of their illness over time. Deaths in the family, breakups, and concerns about other family members were mentioned as specific forms of psychological stress and directly linked by participants to worsening of symptoms. Social support was present for most, but not all, participants, with no appreciable difference based on whether the participant had sickle cell disease. Social support was generally perceived as helpful, and several participants indicated a benefit to their own health when providing social support to others. Financial pressures also served as stressors and often impeded care due to lack of access to medications, other treatments, and housing.

Onset and Progression of Episodes Vary, but Generally Seem Uncontrollable

Regarding the onset of illness episodes, some participants described the sudden, unpredictable onset of symptoms, others described a more gradual onset which allowed them to attempt self-management. Regardless of the timing, episodes of illness were often perceived as spontaneous or triggered by factors outside of the participant’s control. Several participants, especially those with sickle cell disease, mentioned a relationship between their symptoms and the weather. Participants also noted the inconsistency in factors which may trigger an episode (ie, sometimes the factor exacerbated symptoms, while other times it did not). Participants also described having a high symptom burden with significant limitations in activities of daily living during episodes of illness. Pain was a very common component of symptoms regardless of whether or not the participant had sickle cell disease.

Individuals Seek Care after Self-Management Fails and Prefer to Avoid Hospitalization

Participants tried to control their symptoms with medications and typically sought care only when it was clear that this approach was not working, or they ran out of medications. This finding was consistent across both groups of participants (ie, those with and those without sickle cell disease). Many participants described very strong preferences not to come to the hospital; no participant described being in the hospital as a favorable or positive experience. Some participants mentioned that they had spent major holidays in the hospital and that they missed their family. No participant had a desire to come to the hospital.

DISCUSSION

In this study of frequently hospitalized patients, we found four major themes that illuminate patient perspectives about factors that contribute to high hospital use. While some of our findings corroborate those of previous studies, other emerging patterns were novel. Herein, we summarize key findings, provide context, and describe implications for the design of models of care for frequently hospitalized patients.

Similar to the findings of previous quantitative research, participants in our study described having a significant medical condition and typically had multiple medical conditions or complications.4-6 Importantly, some participants described having a major medical problem which did not require frequent hospitalization until another medical problem or complication arose. This finding suggests that there may be an opportunity to identify patients with significant medical problems who are at elevated risk before the onset of high hospital use. Early identification of these high-risk patients could allow for the provision of additional support to prevent potential complications or address other factors which may contribute to the need for frequent hospitalization.

Participants in our study directly linked psychological stress to fluctuations in their course of illness. Previous research by Mautner and colleagues queried participants about childhood experiences and early life stressors and reported that early life instabilities and traumas were prevalent among patients with high levels of emergency and hospital-based healthcare utilization.15 Our participants identified more recent traumatic events (eg, the death of a loved one and breakups) when reflecting on factors contributing to illness exacerbations; early life trauma did not emerge as an identified contributor. Of note, unlike Mautner et al., we did not ask participants to reflect on childhood determinants of disease and illness specifically. Our findings suggest that psychological stress contributes to illness exacerbation, even for those patients without other significant psychiatric conditions (eg, depressive disorder, schizophrenia). Incorporating mental health professionals into programs for this patient population may improve health by teaching specific coping strategies, including cognitive-behavioral therapy for an acute stress disorder.16,17

Social support was also a factor related to illness fluctuations over time. Notably, several participants indicated a benefit to their own health when providing social support to others, suggesting a role for peer support that may be reciprocally beneficial. This approach is supported by the literature. Williams and colleagues found that patients with sickle cell anemia experienced symptom improvement with peer support;18 while Johnson and colleagues recently reported a reduction in readmissions to acute care with the use of peer support for patients with severe mental illness.19

Financial constraints impeded care for some patients and served as a barrier to accessing medications, other treatments, and housing. Similar to the findings of prior quantitative research, our frequently hospitalized patients had a high proportion of patients with Medicaid and low proportion with private insurance, suggesting low socioeconomic status.9,20 We did not formally collect data on income or economic status. Interestingly, prior qualitative studies have not identified financial constraints as a major theme, though this may be explained by differences in study populations and the overall objectives of the studies.15,21 Importantly, the overwhelming majority of programs for frequently hospitalized patients identified in a recent systematic review included social workers.7 Our findings support the need to address financial constraints and the use of social workers in models of care for frequently hospitalized patients.

Many participants in our study felt that the factors contributing to exacerbations of illness were either inconsistent in their effect or out of their control. These findings have similarities to those from a qualitative study by Liu and colleagues in which they interviewed 20 “hospital-dependent” patients over 65 years of age.21 Though not explicitly focused on factors contributing to exacerbations, participants in their study felt that hospitalizations were generally inevitable. In our study, participants with sickle cell disease often identified changes in the weather as contributing to illness exacerbations. The relationship between weather and sickle cell disease remains incompletely understood, with an inconsistent association found in prior studies.22

Participants in our study strongly desired to avoid hospitalization and typically sought hospital care when symptoms could not be controlled at home. This finding is in contrast to that from the study by Liu and colleagues where they found that hospital-dependent patients over 65 years had favorable perspectives of hospitalization because they felt safer and more secure in the hospital.21 Our participants were younger than those from the study by Liu and colleagues, had a high symptom burden, and may have been more concerned about control of those symptoms than the risk for clinical deterioration. Programs should aim to strengthen their support of patients’ self-management efforts early in the episode of illness and potentially offer home visits or a day hospital to avoid hospitalization. A recent systematic review found evidence that alternatives to inpatient care (eg, hospital-at-home) for low risk medical patients can achieve comparable outcomes at lower costs.23 Similarly, some health systems have implemented day hospitals to treat low risk patients with uncomplicated sickle cell pain.24,25

The heavy symptom burden experienced by participants in our study is notable. Pain was especially common. Programs may wish to partner with palliative care and addiction specialists to balance symptom relief with the simultaneous need to address comorbid substance and opioid use disorders when they are present.4,9

Our study has several limitations. First, participants were recruited from the medicine service at a single academic hospital using criteria we developed to identify frequently hospitalized patients. Populations differ across hospitals and definitions of frequently hospitalized patients vary, limiting the generalizability of our findings. Second, we excluded patients whose preferred language was not English, as well as those disoriented to person, place, or time. It is possible that factors contributing to high hospital use differ for non-English speaking patients and those with cognitive deficits.

CONCLUSION

In this qualitative study, we identified factors associated with the onset and continuation of high hospital use. Emergent themes pointed to factors which influence patients’ onset of high hospital use, fluctuations in their illness over time, and triggers to seek care during an illness episode. These findings represent an important contribution to the literature because they allow patients’ perspectives to be incorporated into the design and adaptation of programs serving similar populations in other health systems. Programs that integrate patients’ perspectives into their design are likely to be better prepared to address patients’ needs and improve patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants for their time and willingness to share their stories. The authors also thank Claire A. Knoten PhD and Erin Lambers PhD, former research team members who helped in the initial stages of the study.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This project was funded by Northwestern Memorial Hospital and the Northwestern Medical Group.

In recent years, hospitals have made considerable efforts to improve transitions of care, in part due to financial incentives from the Medicare Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP).1 Initially focusing on three medical conditions, the HRRP has been associated with significant reductions in readmission rates.2 Importantly, a small proportion of patients accounts for a very large proportion of hospital readmissions and hospital use.3,4 Frequently hospitalized patients often have multiple chronic conditions and unique needs which may not be met by conventional approaches to healthcare delivery, including those influenced by the HRRP.4-6 In light of this challenge, some hospitals have developed programs specifically focused on frequently hospitalized patients. A recent systematic review of these programs found relatively few studies of high quality, providing only limited insight in designing interventions to support this population.7 Moreover, no studies appear to have incorporated the patients’ perspectives into the design or adaptation of the model. Members of our research team developed and implemented the Complex High Admission Management Program (CHAMP) in January 2016 to address the needs of frequently hospitalized patients in our hospital. To enhance CHAMP and inform the design of programs serving similar populations in other health systems, we sought to identify factors associated with the onset and continuation of high hospital use. Our research question was, from the patients’ perspective, what factors contribute to patients’ becoming and continuing to be high users of hospital care.

METHODS

Setting, Study Design, and Participants

This qualitative study took place at Northwestern Memorial Hospital (NMH), an 894-bed urban academic hospital located in Chicago, Illinois. Between December 2016 and September 2017, we recruited adult patients admitted to the general medicine services. Eligible participants were identified with the assistance of a daily Northwestern Medicine Electronic Data Warehouse (EDW) search and included patients with two unplanned 30-day inpatient readmissions to NMH within the prior 12 months, in addition to one or more of the following criteria: (1) at least one readmission in the last six months; (2) a referral from one of the patient’s medical providers; or (3) at least three observation visits. We excluded patients whose preferred language was not English and those disoriented to person, place, or time. Considering NMH data showing that approximately one-third of high-utilizer patients have sickle cell disease, we used purposive sampling with the goal to compare findings within and between two groups of participants; those with and those without sickle cell disease. Our study was deemed exempt by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board.

Participant Enrollment and Data Collection

We created an interview guide based on the research team’s experience with this population, a literature review, and our research question (See Appendix).8,9 A research coordinator approached eligible participants during their hospital stay. The coordinator explained the study to eligible participants and obtained verbal consent for participation. The research coordinator then conducted one-on-one semi-structured interviews. Interviews were audio recorded for subsequent transcription and coding. Each interview lasted approximately 45 minutes. Participants were compensated with a $20 gift card for their time.

Analysis

Digital audio recordings from interviews were transcribed verbatim, deidentified, and analyzed using an iterative inductive team-based approach to coding.10 In our first cycle coding, all coders (KJO, SF, MMC, LO, KAC) independently reviewed and coded three transcripts using descriptive coding and subcoding to generate a preliminary codebook with code definitions.10,11 Following the meetings to compare and compile our initial coding, each researcher then independently recoded the three transcripts with the developed codebook. The researchers met again to triangulate perspectives and reach a consensus on the final codebook. Using multiple coders is a standard process to control for subjective bias that one coder could bring to the coding process.12 Following this meeting, the coders split into two teams of two (KJO, SF, and MMC, LO) to complete the coding of the remaining transcripts. Each team member independently coded the assigned transcripts and reconciled their codes with their counterpart; any discrepancies were resolved through discussion. Using this strategy, every transcript was coded by at least two team members. Our second coding cycle utilized pattern coding and involved identifying consistency both within and between transcripts; discovering associations between codes.10,11,13 Constant comparison was used to compare responses among all participants, as well as between sickle-cell and nonsickle-cell participants.13,14 Following team coding and reconciling, the analyses were presented to a broader research team for additional feedback and critique. All analyses were conducted using Dedoose version 8.0.35 (Los Angeles, California). Participant recruitment, interviews, and analysis of the transcripts continued until no new codes emerged and thematic saturation was achieved.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Overall, we invited 34 patients to be interviewed; 26 consented and completed interviews (76.5%). Six (17.6%) patients declined participation, one (2.9%) was unable to complete the interview before hospital discharge, and one (2.9%) was excluded due to disorientation. Demographic characteristics of the 26 participants are shown in Table 1.

Four main themes emerged from our analysis. Table 2 summarizes these themes, subthemes, and provides representative quotes.

Major Medical Problem(s) are Universal, but High Hospital Use Varies in Onset

Not surprisingly, all participants described having at least one major medical problem. Some participants, such as those with genetic disorders, had experienced periods of high hospital use throughout their entire lifetime, while other participants experienced an onset of high hospital use as an adult after being previously healthy. Though most participants with genetic disorders had sickle cell anemia; one had a rare genetic disorder which caused chronic gastrointestinal symptoms. Participants typically described having a significant medical condition as well as other medical problems or complications from past surgery. Some participants described having a major medical problem which did not require frequent hospitalization until a complication or other medical problem arose, suggesting these new issues pushed them over a threshold beyond which self-management at home was less successful.

Course Fluctuates over Time and is Related to Psychological, Social, and Economic Factors

Participants identified psychological stress, social support, and financial constraints as factors which influence the course of their illness over time. Deaths in the family, breakups, and concerns about other family members were mentioned as specific forms of psychological stress and directly linked by participants to worsening of symptoms. Social support was present for most, but not all, participants, with no appreciable difference based on whether the participant had sickle cell disease. Social support was generally perceived as helpful, and several participants indicated a benefit to their own health when providing social support to others. Financial pressures also served as stressors and often impeded care due to lack of access to medications, other treatments, and housing.

Onset and Progression of Episodes Vary, but Generally Seem Uncontrollable

Regarding the onset of illness episodes, some participants described the sudden, unpredictable onset of symptoms, others described a more gradual onset which allowed them to attempt self-management. Regardless of the timing, episodes of illness were often perceived as spontaneous or triggered by factors outside of the participant’s control. Several participants, especially those with sickle cell disease, mentioned a relationship between their symptoms and the weather. Participants also noted the inconsistency in factors which may trigger an episode (ie, sometimes the factor exacerbated symptoms, while other times it did not). Participants also described having a high symptom burden with significant limitations in activities of daily living during episodes of illness. Pain was a very common component of symptoms regardless of whether or not the participant had sickle cell disease.

Individuals Seek Care after Self-Management Fails and Prefer to Avoid Hospitalization

Participants tried to control their symptoms with medications and typically sought care only when it was clear that this approach was not working, or they ran out of medications. This finding was consistent across both groups of participants (ie, those with and those without sickle cell disease). Many participants described very strong preferences not to come to the hospital; no participant described being in the hospital as a favorable or positive experience. Some participants mentioned that they had spent major holidays in the hospital and that they missed their family. No participant had a desire to come to the hospital.

DISCUSSION

In this study of frequently hospitalized patients, we found four major themes that illuminate patient perspectives about factors that contribute to high hospital use. While some of our findings corroborate those of previous studies, other emerging patterns were novel. Herein, we summarize key findings, provide context, and describe implications for the design of models of care for frequently hospitalized patients.

Similar to the findings of previous quantitative research, participants in our study described having a significant medical condition and typically had multiple medical conditions or complications.4-6 Importantly, some participants described having a major medical problem which did not require frequent hospitalization until another medical problem or complication arose. This finding suggests that there may be an opportunity to identify patients with significant medical problems who are at elevated risk before the onset of high hospital use. Early identification of these high-risk patients could allow for the provision of additional support to prevent potential complications or address other factors which may contribute to the need for frequent hospitalization.

Participants in our study directly linked psychological stress to fluctuations in their course of illness. Previous research by Mautner and colleagues queried participants about childhood experiences and early life stressors and reported that early life instabilities and traumas were prevalent among patients with high levels of emergency and hospital-based healthcare utilization.15 Our participants identified more recent traumatic events (eg, the death of a loved one and breakups) when reflecting on factors contributing to illness exacerbations; early life trauma did not emerge as an identified contributor. Of note, unlike Mautner et al., we did not ask participants to reflect on childhood determinants of disease and illness specifically. Our findings suggest that psychological stress contributes to illness exacerbation, even for those patients without other significant psychiatric conditions (eg, depressive disorder, schizophrenia). Incorporating mental health professionals into programs for this patient population may improve health by teaching specific coping strategies, including cognitive-behavioral therapy for an acute stress disorder.16,17

Social support was also a factor related to illness fluctuations over time. Notably, several participants indicated a benefit to their own health when providing social support to others, suggesting a role for peer support that may be reciprocally beneficial. This approach is supported by the literature. Williams and colleagues found that patients with sickle cell anemia experienced symptom improvement with peer support;18 while Johnson and colleagues recently reported a reduction in readmissions to acute care with the use of peer support for patients with severe mental illness.19

Financial constraints impeded care for some patients and served as a barrier to accessing medications, other treatments, and housing. Similar to the findings of prior quantitative research, our frequently hospitalized patients had a high proportion of patients with Medicaid and low proportion with private insurance, suggesting low socioeconomic status.9,20 We did not formally collect data on income or economic status. Interestingly, prior qualitative studies have not identified financial constraints as a major theme, though this may be explained by differences in study populations and the overall objectives of the studies.15,21 Importantly, the overwhelming majority of programs for frequently hospitalized patients identified in a recent systematic review included social workers.7 Our findings support the need to address financial constraints and the use of social workers in models of care for frequently hospitalized patients.

Many participants in our study felt that the factors contributing to exacerbations of illness were either inconsistent in their effect or out of their control. These findings have similarities to those from a qualitative study by Liu and colleagues in which they interviewed 20 “hospital-dependent” patients over 65 years of age.21 Though not explicitly focused on factors contributing to exacerbations, participants in their study felt that hospitalizations were generally inevitable. In our study, participants with sickle cell disease often identified changes in the weather as contributing to illness exacerbations. The relationship between weather and sickle cell disease remains incompletely understood, with an inconsistent association found in prior studies.22

Participants in our study strongly desired to avoid hospitalization and typically sought hospital care when symptoms could not be controlled at home. This finding is in contrast to that from the study by Liu and colleagues where they found that hospital-dependent patients over 65 years had favorable perspectives of hospitalization because they felt safer and more secure in the hospital.21 Our participants were younger than those from the study by Liu and colleagues, had a high symptom burden, and may have been more concerned about control of those symptoms than the risk for clinical deterioration. Programs should aim to strengthen their support of patients’ self-management efforts early in the episode of illness and potentially offer home visits or a day hospital to avoid hospitalization. A recent systematic review found evidence that alternatives to inpatient care (eg, hospital-at-home) for low risk medical patients can achieve comparable outcomes at lower costs.23 Similarly, some health systems have implemented day hospitals to treat low risk patients with uncomplicated sickle cell pain.24,25

The heavy symptom burden experienced by participants in our study is notable. Pain was especially common. Programs may wish to partner with palliative care and addiction specialists to balance symptom relief with the simultaneous need to address comorbid substance and opioid use disorders when they are present.4,9

Our study has several limitations. First, participants were recruited from the medicine service at a single academic hospital using criteria we developed to identify frequently hospitalized patients. Populations differ across hospitals and definitions of frequently hospitalized patients vary, limiting the generalizability of our findings. Second, we excluded patients whose preferred language was not English, as well as those disoriented to person, place, or time. It is possible that factors contributing to high hospital use differ for non-English speaking patients and those with cognitive deficits.

CONCLUSION

In this qualitative study, we identified factors associated with the onset and continuation of high hospital use. Emergent themes pointed to factors which influence patients’ onset of high hospital use, fluctuations in their illness over time, and triggers to seek care during an illness episode. These findings represent an important contribution to the literature because they allow patients’ perspectives to be incorporated into the design and adaptation of programs serving similar populations in other health systems. Programs that integrate patients’ perspectives into their design are likely to be better prepared to address patients’ needs and improve patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants for their time and willingness to share their stories. The authors also thank Claire A. Knoten PhD and Erin Lambers PhD, former research team members who helped in the initial stages of the study.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This project was funded by Northwestern Memorial Hospital and the Northwestern Medical Group.

1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Readmissions Reduction Program. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program.html. Accessed September 17, 2018.

2. Wasfy JH, Zigler CM, Choirat C, Wang Y, Dominici F, Yeh RW. Readmission rates after passage of the hospital readmissions reduction program: a pre-post analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2016;166(5):324-331. https://doi.org/10.7326/m16-0185.

3. Blumenthal D, Chernof B, Fulmer T, Lumpkin J, Selberg J. Caring for high-need, high-cost patients-an urgent priority. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(10):909-911. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp1608511.

4. Szekendi MK, Williams MV, Carrier D, Hensley L, Thomas S, Cerese J. The characteristics of patients frequently admitted to academic medical centers in the United States. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(9):563-568. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2375.

5. Dastidar JG, Jiang M. Characterization, categorization, and 5-year mortality of medicine high utilizer inpatients. J Palliat Care. 2018;33(3):167-174. https://doi.org/10.1177/0825859718769095.

6. Mudge AM, Kasper K, Clair A, et al. Recurrent readmissions in medical patients: a prospective study. J Hosp Med. 2010;6(2):61-67. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.811.

7. Goodwin A, Henschen BL, Odwyer LC, Nichols N, Oleary KJ. Interventions for frequently hospitalized patients and their effect on outcomes: a systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(12):853-859. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3090.

8. Gelberg L, Andersen RM, Leake BD. The behavioral model for vulnerable populations: application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Serv Res. 2000;34(6):1273-1302. PubMed

9. Rinehart DJ, Oronce C, Durfee MJ, et al. Identifying subgroups of adult superutilizers in an urban safety-net system using latent class analysis. Med Care. 2018;56(1):e1-e9. https://doi.org/10.1097/mlr.0000000000000628.

10. Miles MB, Huberman M, Saldana J. Qualitative Data Analysis. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications; 2014.

11. Saldana J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE publications; 2013.

12. Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. 1 ed. Beverly Hills, California: SAGE Publications; 1985.

13. Kolb SM. Grounded theory and the constant comparative method: valid research strategies for educators. J Emerging Trends Educ Res Policy Stud. 2012;3(1):83-86.

14. Glasser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. New York: Taylor and Francis Group; 2017.

15. Mautner DB, Pang H, Brenner JC, et al. Generating hypotheses about care needs of high utilizers: lessons from patient interviews. Popul Health Manag. 2013;16(Suppl 1):S26-S33. https://doi.org/10.1089/pop.2013.0033.

16. Carpenter JK, Andrews LA, Witcraft SM, Powers MB, Smits JAJ, Hofmann SG. Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and related disorders: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Depres Anxiety. 2018;35(6):502-514. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22728.

17. Roberts NP, Kitchiner NJ, Kenardy J, Bisson JI. Systematic review and meta-analysis of multiple-session early interventions following traumatic events. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(3):293-301. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08040590.

18. Williams H, Tanabe P. Sickle cell disease: a review of nonpharmacological approaches for pain. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2016;51(2):163-177. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.10.017.

19. Johnson S, Lamb D, Marston L, et al. Peer-supported self-management for people discharged from a mental health crisis team: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;392(10145):409-418.https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)31470-3.

20. Mercer T, Bae J, Kipnes J, Velazquez M, Thomas S, Setji N. The highest utilizers of care: individualized care plans to coordinate care, improve healthcare service utilization, and reduce costs at an academic tertiary care center. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(7):419-424. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2351.

21. Liu T, Kiwak E, Tinetti ME. Perceptions of hospital-dependent patients on their needs for hospitalization. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(6):450-453. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2756.

22. Piel FB, Steinberg MH, Rees DC. Sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(16):1561-1573. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmra1510865.

23. Conley J, O’Brien CW, Leff BA, Bolen S, Zulman D. Alternative strategies to inpatient hospitalization for acute medical conditions: a systematic review. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(11):1693-1702. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5974.

24. Adewoye AH, Nolan V, McMahon L, Ma Q, Steinberg MH. Effectiveness of a dedicated day hospital for management of acute sickle cell pain. Haematologica. 2007;92(6):854-855. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.10757.

25. Benjamin LJ, Swinson GI, Nagel RL. Sickle cell anemia day hospital: an approach for the management of uncomplicated painful crises. Blood. 2000;95(4):1130-1136. PubMed

1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Readmissions Reduction Program. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program.html. Accessed September 17, 2018.

2. Wasfy JH, Zigler CM, Choirat C, Wang Y, Dominici F, Yeh RW. Readmission rates after passage of the hospital readmissions reduction program: a pre-post analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2016;166(5):324-331. https://doi.org/10.7326/m16-0185.

3. Blumenthal D, Chernof B, Fulmer T, Lumpkin J, Selberg J. Caring for high-need, high-cost patients-an urgent priority. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(10):909-911. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp1608511.

4. Szekendi MK, Williams MV, Carrier D, Hensley L, Thomas S, Cerese J. The characteristics of patients frequently admitted to academic medical centers in the United States. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(9):563-568. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2375.

5. Dastidar JG, Jiang M. Characterization, categorization, and 5-year mortality of medicine high utilizer inpatients. J Palliat Care. 2018;33(3):167-174. https://doi.org/10.1177/0825859718769095.

6. Mudge AM, Kasper K, Clair A, et al. Recurrent readmissions in medical patients: a prospective study. J Hosp Med. 2010;6(2):61-67. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.811.

7. Goodwin A, Henschen BL, Odwyer LC, Nichols N, Oleary KJ. Interventions for frequently hospitalized patients and their effect on outcomes: a systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(12):853-859. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3090.

8. Gelberg L, Andersen RM, Leake BD. The behavioral model for vulnerable populations: application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Serv Res. 2000;34(6):1273-1302. PubMed

9. Rinehart DJ, Oronce C, Durfee MJ, et al. Identifying subgroups of adult superutilizers in an urban safety-net system using latent class analysis. Med Care. 2018;56(1):e1-e9. https://doi.org/10.1097/mlr.0000000000000628.

10. Miles MB, Huberman M, Saldana J. Qualitative Data Analysis. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications; 2014.

11. Saldana J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE publications; 2013.

12. Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. 1 ed. Beverly Hills, California: SAGE Publications; 1985.

13. Kolb SM. Grounded theory and the constant comparative method: valid research strategies for educators. J Emerging Trends Educ Res Policy Stud. 2012;3(1):83-86.

14. Glasser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. New York: Taylor and Francis Group; 2017.

15. Mautner DB, Pang H, Brenner JC, et al. Generating hypotheses about care needs of high utilizers: lessons from patient interviews. Popul Health Manag. 2013;16(Suppl 1):S26-S33. https://doi.org/10.1089/pop.2013.0033.

16. Carpenter JK, Andrews LA, Witcraft SM, Powers MB, Smits JAJ, Hofmann SG. Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and related disorders: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Depres Anxiety. 2018;35(6):502-514. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22728.

17. Roberts NP, Kitchiner NJ, Kenardy J, Bisson JI. Systematic review and meta-analysis of multiple-session early interventions following traumatic events. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(3):293-301. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08040590.

18. Williams H, Tanabe P. Sickle cell disease: a review of nonpharmacological approaches for pain. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2016;51(2):163-177. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.10.017.

19. Johnson S, Lamb D, Marston L, et al. Peer-supported self-management for people discharged from a mental health crisis team: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;392(10145):409-418.https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)31470-3.

20. Mercer T, Bae J, Kipnes J, Velazquez M, Thomas S, Setji N. The highest utilizers of care: individualized care plans to coordinate care, improve healthcare service utilization, and reduce costs at an academic tertiary care center. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(7):419-424. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2351.

21. Liu T, Kiwak E, Tinetti ME. Perceptions of hospital-dependent patients on their needs for hospitalization. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(6):450-453. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2756.

22. Piel FB, Steinberg MH, Rees DC. Sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(16):1561-1573. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmra1510865.

23. Conley J, O’Brien CW, Leff BA, Bolen S, Zulman D. Alternative strategies to inpatient hospitalization for acute medical conditions: a systematic review. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(11):1693-1702. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5974.

24. Adewoye AH, Nolan V, McMahon L, Ma Q, Steinberg MH. Effectiveness of a dedicated day hospital for management of acute sickle cell pain. Haematologica. 2007;92(6):854-855. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.10757.

25. Benjamin LJ, Swinson GI, Nagel RL. Sickle cell anemia day hospital: an approach for the management of uncomplicated painful crises. Blood. 2000;95(4):1130-1136. PubMed

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Helping Seniors Plan for Posthospital Discharge Needs Before a Hospitalization Occurs: Results from the Randomized Control Trial of PlanYourLifespan.org

When seniors are discharged from the hospital, many will require additional support and therapy to regain their independence and return safely home.1,2 Most seniors do not understand what their support needs will entail or the differences between therapy choices.3 To complicate the issue, seniors are often incapacitated and unable to make discharge selections for themselves.

Consequently, discharge planners and social workers often explain options to family members and loved ones, who frequently feel overwhelmed.4,5 While often balancing jobs, loved ones are divided between wanting to stay with the senior in the hospital and driving to area skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) for consideration. Discharges are delayed waiting for families to make visits and choose an SNF. Longer lengths of stay are detrimental to seniors due to the increased risks of infection, functional loss, and cognitive decline.6

Although seniors comprised only 12% of the US population in 2003,7 they accounted for one-third of all hospitalizations, over 13.2 million hospital stays.8 Hospital stays for seniors resulted in hospital charges totaling nearly $329 billion, or 43.6% of national hospital bills in 2003.7 Seniors are also high consumers of postacute care services. By 2050, the number of individuals using long-term care services in any setting (eg, at home, assisted living, or SNFs) will be close to 27 million.9-11 With the knowledge that many seniors will be hospitalized and subsequently require services thereafter, we sought to assist seniors in planning for their hospital discharge needs before they were hospitalized.

Our team developed PlanYourLifespan.org (PYL) to facilitate this planning for postdischarge needs and fill the knowledge gap in understanding postdischarge options. With funding from the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute, we aimed to test the effectiveness of PYL on improving knowledge of hospital discharge resources among seniors.

METHODS

PlanYourLifespan.org

PlanYourLifespan.org (PYL) educates users on the health crises that often occur with age and connects them to posthospital and home-based resources available locally and nationally. PYL is personalized, dynamic, and adaptable in that all the information can be changed per the senior’s wishes or changing health needs.

Content of PYL

Previously, we conducted focus groups with seniors about current and perceived home needs and aging-in-place. Major themes of what advanced life events (ALEs) would impact aging-in-place were identified as follows: hospitalizations, falls, and Alzheimer’s.12 We organized PYL around these health-related ALEs. Our multidisciplinary team of researchers, seniors, social workers, caregiver agencies, and Area Agencies on Aging representatives then determined what information and resources should be included.

Each section of PYL starts with a video of a senior discussing their real-life personal experiences, with subsections providing interactive information on what seniors can expect, types of resources available to support home needs, and choices to be made. Descriptions of types of settings for therapy, options available, and links to national/local resources (eg, quality indicators for SNFs) are also included. For example, by entering their zip code, users can identify their neighborhood SNFs, closest Area Agency on Aging, and what home caregiver agencies exist in their area.

Users can save their preferences and revisit their choices at any time. To support communication between seniors and their loved ones, a summary of their choices can be printed or e-mailed to relevant parties. For example, a senior uses PYL and can e-mail these choices to family members, which can stimulate a conversation about future posthospital care expectations.

As inadequate health literacy and cognitive impairment are prevalent among seniors, PYL presents information understandable at all levels of health literacy and sensitive to cognitive load.9 There is simplified, large-font, no mouse scrolling and audio available for the visually impaired.

Study Design and Randomization

To test PYL, a 2-armed (attention control [AC] and PYL intervention), parallel, randomized controlled trial was conducted. Participants were randomly assigned to 1 of the 2 conditions via a pregenerated central randomization list using equal (1:1) allocation and random permuted block design to ensure relatively equal allocation throughout the study. The AC condition exposed participants to the National Institute on Aging-sponsored website, Go4Life.nia.nih.gov, an educational website on physical activity for seniors. This website has comparable design and layout to PYL but does not include information about advanced planning. The AC condition controlled for the possibility that regular contact with the study team may improve outcomes in participants randomized to the intervention website.

The trial was conducted from October 2014 to September 2015 in Chicago, Illinois; Fort Wayne, Indiana; and Houston, Texas. Inclusion criteria were as follows: age 65 and older, English-speaking, scoring ≥4 questions correctly on the Brief Cognitive Screen,14 and current self-reported use of a computer or smartphone with internet. Participants were excluded if they had previously participated in the focus groups or beta testing of the PYL website. Community-based patient partners/stakeholders drove subject recruitment in their communities through word of mouth, e-mail bursts, newsletters, and flyers. At the Area Agency on Aging and community centers where services such as food vouchers and case management are provided, participants were recruited on-site and given study information. At the clinical sites, staff referred potential participants. Study materials such as flyers and information sheets were also located in the clinic waiting rooms. The Villages, nonprofit, grassroots, membership organizations that are redefining aging by being a key resource to community members wishing to age in place, heavily relied on electronic recruitment using their regular e-newsletters and e-mail lists to recruit potential participants. Potential subjects were also recruited by distributing flyers at local senior centers and senior housing buildings. Interested seniors contacted research staff who explained the study and assessed their eligibility. If eligible, subjects were scheduled for a face-to-face interview.

At the face-to-face encounter, all study subjects completed a written consent, answered baseline questions, and were randomized to either arm. Next, research staff introduced all study subjects to the website to which they were randomized and provided instructions on its use. Staff were present to assist with questions as needed on navigation but did not assist with decision making for either website. A minimum of 15 minutes and a maximum of 45 minutes was allotted for navigating either website. After navigating their website, participants were administered an immediate in-person posttest survey. One month and 3 months after the face-to-face encounter, research staff contacted all study participants over the phone to complete a follow-up survey. Staff attempted to reach participants up to 3 times by phone. Data were entered into Research Electronic Data Capture survey software.15 This study was approved by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board.

Understanding of Posthospital Discharge and Home Services

As part of the larger trial, which included behavioural outcomes that will be reported elsewhere, we sought to explore the effects of PYL on participants’ knowledge and understanding of posthospital discharge and home services (UHS). Participants were asked to respond to 6 questions at baseline, immediate posttest, and at the 1- and 3-month follow-up time points. Knowledge items were developed by the study team in conjunction with the patient/partner stakeholders. UHS scores were calculated as the sum of the 6 questions (each scored 0 if incorrect and 1 if correct) with a possible range of 0-6.

Covariates

Demographic information, self-reported health, importance of religion, and existence of a power of attorney, living will, advanced directive (eg, Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment) were obtained via self-report. Participants were asked about their general and social self-efficacy using the validated Self-efficacy Scale16 and their social support using the Lubben Social Network Scale–6.17 Health literacy was assessed using the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine–Short Form.18 To measure burden of disease, participant comorbidities were measured using a nonvalidated 9-item dichotomous response condition list, which included some items adapted from the Charlson Comorbidity Index and the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis included all available data in the intention-to-treat dataset. As UHS was collected at multiple time points up to 3 months postintervention, we employed linear- mixed modeling with random participant effect and fixed arm, time, and time-by-arm interaction terms. The time-by-arm interaction allows for comparison of UHS slopes (or trajectories) across arms. Analyses explored multiple potential covariates, including current utilization of services, physical function, comorbidities, social support, health literacy, self-efficacy, and sociodemographics. Those covariates found to have a significant association (P < 0.05) with outcome were considered for inclusion in the overall model selection process. Ultimately, we developed a final parsimonious, adjusted longitudinal model with primary predictors of time, arm, and their interaction, controlling for only significant baseline variables following a manual backward selection method. All analyses were conducted in SAS software (version 9.4, copyright 2012, The SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

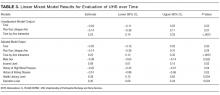

RESULTS

Table 3 illustrates linear mixed model results both failing to adjust and adjusting for potentially influential baseline covariates. In both instances, the interaction term (arm-by-time) was highly significant (P < 0.0001) in predicting UHS score, suggesting that, when compared to the AC arm, the intervention arm exhibited a large mean slope in UHS score over time. That is, understanding home services score tended to increase at a faster rate for those in the active arm. Higher levels of income (P = 0.0191), literacy (P = 0.0036), and education (P = 0.0042) were associated with increased UHS scores; however, male sex (P = 0.0023) and history of high blood pressure (P = 0.0409) or kidney disease (P = 0.0278) were negatively associated with UHS scores.

CONCLUSION/DISCUSSION

The results of our study show that among seniors, PYL improved their understanding of home-based services and the services that may be required following a hospitalization. Educating seniors about what to expect regarding the transition home from a hospital before a hospitalization even occurs may enable seniors and their families to plan ahead instead of reacting to a hospitalization. PYL, a national, publicly available tool with links to local resources may potentially help in advancing transitional discharge care to prior to a hospitalization.

To our knowledge, this is one of the first websites and trials devoted to planning for seniors’ health trajectory as they age into their 70s, 80s, 90s, and 100s. Clinicians regularly discuss code status and powers of attorney during their end-of-life discussions with patients. We encourage clinicians to ask patients, “What about the 10 to 20 years before you die? Have you considered what you will do if you get sick or need help at home?” While not replacing a social worker, the ability of PYL to connect seniors to local resources makes it somewhat of a “virtual social worker.” With many physician practices unable to afford social workers, PYL provides a free-of-charge means of connecting seniors to area resources.