User login

Using SNRIs to prevent migraines in patients with depression

Ms. D, age 45, has major depressive disorder (MDD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), migraines, and hypertension. At a follow-up visit, she says she has been under a lot of stress at work in the past several months and feels her antidepressant is not working well for her depression or anxiety. Ms. D notes that lately she has had more frequent migraines, occurring approximately 4 times per month during the past 3 months. She describes a severe throbbing frontal pain that occurs primarily on the left side of her head, but sometimes on the right side. Ms. D says she experiences nausea, vomiting, and photophobia during these migraine episodes. The migraines last up to 12 hours, but often resolve with sumatriptan 50 mg as needed.

Ms. D takes fluoxetine 60 mg/d for depression and anxiety, lisinopril 20 mg/d for hypertension, as well as a women’s multivitamin and vitamin D3 daily. She has not tried other antidepressants and misses doses of her medications about once every other week. Her blood pressure is 125/80 mm Hg; heart rate is 80 beats per minute; and temperature is 37° C. Ms. D’s treatment team is considering switching her to a medication that can act as preventative therapy for migraines while also treating her depression and anxiety.

Migraine is a chronic, disabling neurovascular disorder that affects approximately 15% of the United States population.1 It is the second-leading disabling condition worldwide and may negatively affect social, family, personal, academic, and occupational domains.2 Migraine is often characterized by throbbing pain, is frequently unilateral, and may last 24 to 72 hours.3 It may occur with or without aura and can be associated with nausea, vomiting, or sensitivity to light.3 Episodic migraines occur <15 days a month, while chronic migraines occur ≥15 days a month.4

Many psychiatric, neurologic, vascular, and cardiac comorbidities are more prevalent in individuals who experience migraine headaches compared to the general population. Common psychiatric comorbidities found in patients with migraines are depression, bipolar disorder, GAD, panic disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder5; MDD is the most common.4 A person who experiences migraine headaches is 2 to 4 times more likely to develop MDD than one who does not experience migraine headaches.4

First-line treatments for preventing migraine including divalproex, topiramate, metoprolol, propranolol, and timolol.6 However, for some patients with migraines and comorbid depression or anxiety, an antidepressant may be an option. This article briefly reviews the evidence for using antidepressants that have been studied for their ability to decrease migraine frequency.

Antidepressants that can prevent migraine

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are second- or third-line options for migraine prevention.6 While TCAs have proven to be effective for preventing migraines, many patients are unable to tolerate their adverse effects (ie, anticholinergic effects, sedation).7 TCAs may be more appealing for younger patients, who may be less bothered by anticholinergic burden, or those who have difficulty sleeping.

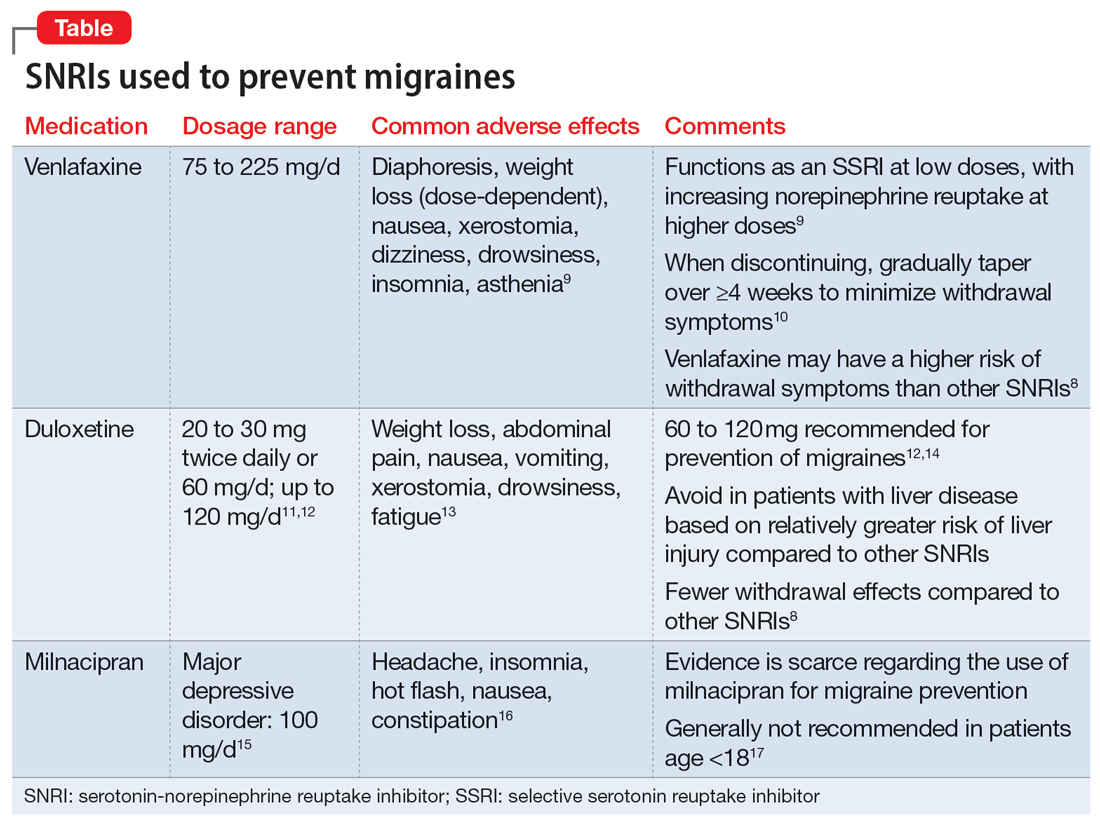

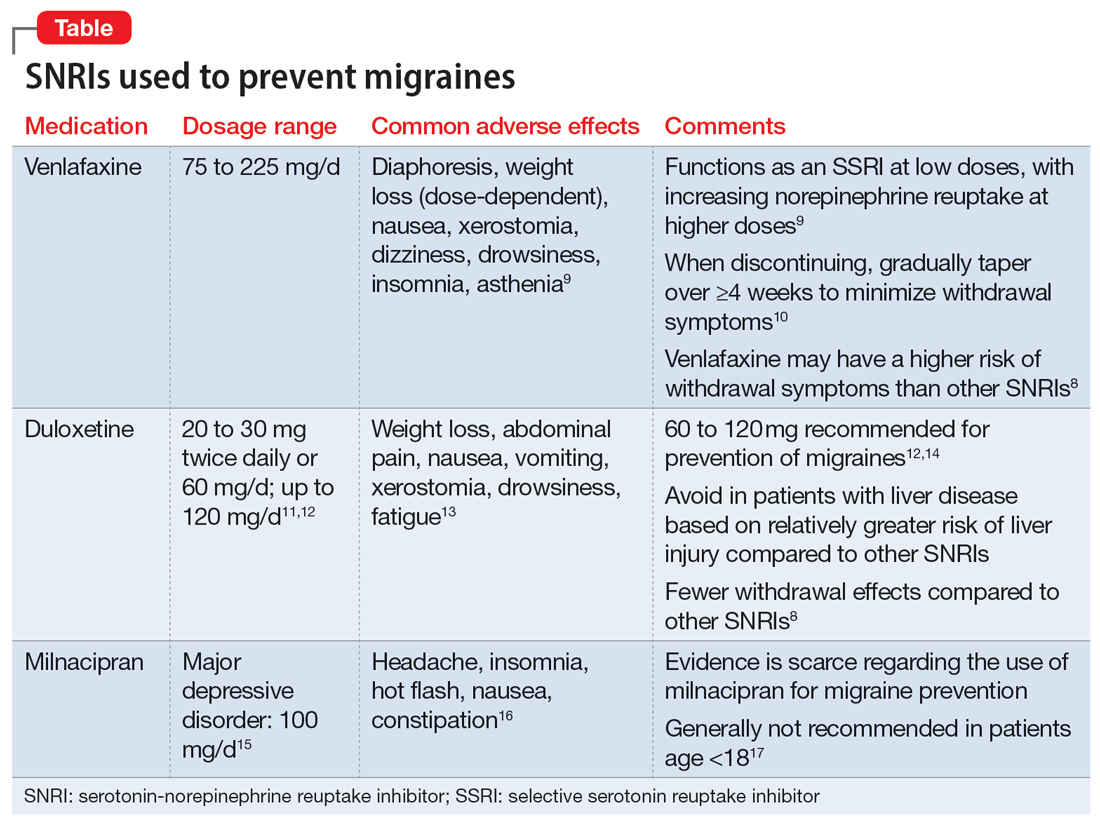

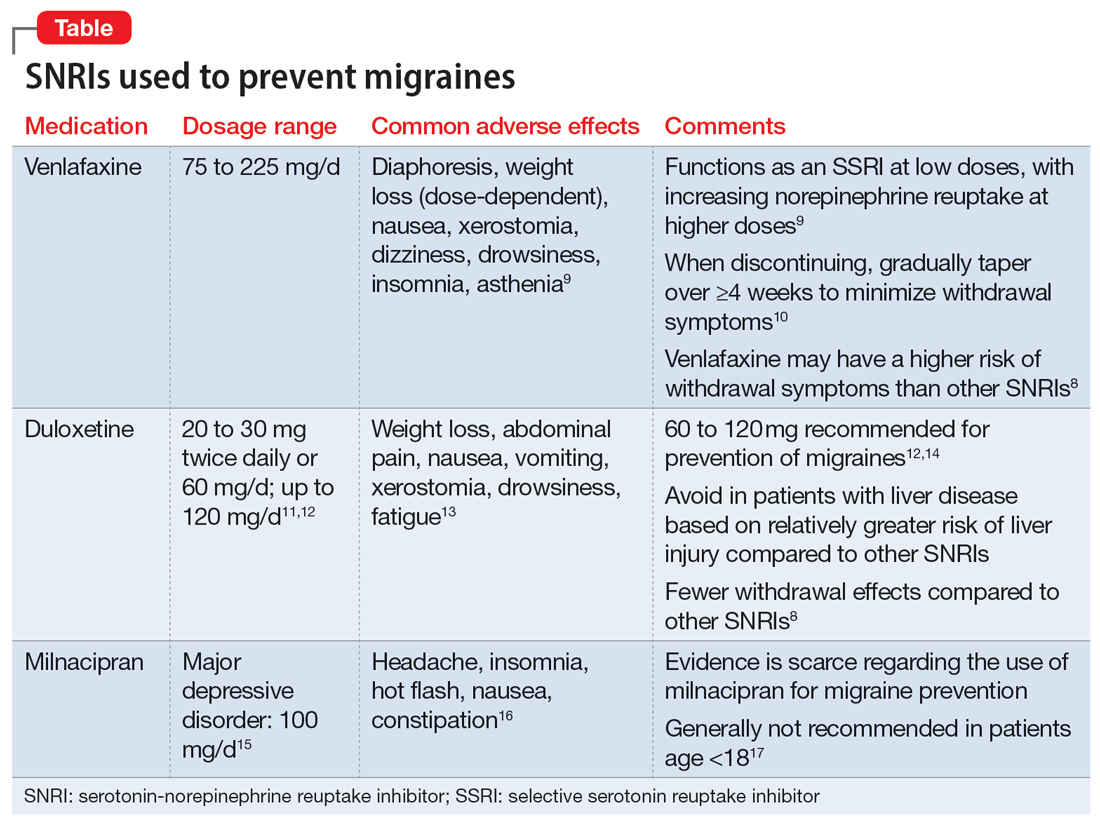

Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). There has been growing interest in understanding the potential utility of SNRIs as a preventative treatment for migraines. Research has found that SNRIs are as effective as TCAs for preventing migraines and also more tolerable in terms of adverse effects.7 SNRIs such as venlafaxine and duloxetine are currently prescribed off-label to prevent migraines despite a lack of FDA approval for this indication.8

Continue to: Understanding the safety and efficacy...

Understanding the safety and efficacy of SNRIs as preventative treatment for episodic migraines is useful, particularly for patients with comorbid depression. The Table8-17 details clinical information related to SNRI use.

Duloxetine has demonstrated efficacy in preventing migraines in patients with comorbid depression.8 In a 2019 study, Kisler et al14 found that duloxetine 60 mg/d for 7 weeks was more effective for migraine prophylaxis than placebo as measured by the percentage of self-estimated migraine improvement by each patient compared to pretreatment levels (duloxetine: 52.3% ± 30.4%; placebo: 26.0% ± 27.3%; P = .001).

Venlafaxine has also demonstrated efficacy for preventing migraines in patients with comorbid depression.8 One study demonstrated a significant decrease in headaches per month with the use of venlafaxine 150 mg/d compared to placebo.18 Adelman et al19 found a reduction in migraine headaches per month (16.1 to 11.1, P < .0001) in patients who took venlafaxine for an average of 6 months with a mean dose of 150 mg/d. In a study of patients who did not have a mood disorder, Tarlaci20 found that venlafaxine reduced migraine headache independent of its antidepressant action.

Though milnacipran has not been studied as extensively as other SNRIs, evidence suggests it reduces the incidence of headaches and migraines, especially among episodic migraine patients. Although it has an equipotent effect on both serotonin and norepinephrine (NE) reuptake, milnacipran has a greater NE effect compared to other SNRIs approved for treating mood disorders. A prospective, single-arm study by Engel et al21 found a significant (P < .005) reduction from baseline in all headache and migraine days per month with the use of milnacipran 100 mg/d over the course of 3 months. The number of headache days per month was reduced by 4.2 compared to baseline. This same study reported improved functionality and reduced use of acute and symptomatic medications overall due to the decrease in headaches and migraines.21

In addition to demonstrating that certain SNRIs can effectively prevent migraine, some evidence suggests certain patients may benefit from the opportunity to decrease pill burden by using a single medication to treat both depression and migraine.22 Duloxetine may be preferred for patients who struggle with adherence (such as Ms. D) due to its relatively lower incidence of withdrawal symptoms compared to venlafaxine.8

CASE CONTINUED

Ms. D’s psychiatrist concludes she would be an appropriate candidate for treatment with an SNRI due to her history of MDD and chronic migraines. Because Ms. D expresses some difficulty remembering to take her medications, the psychiatrist recommends duloxetine because it is less likely to produce withdrawal symptoms compared to venlafaxine. To decrease pill burden, fluoxetine 60 mg is stopped with no taper due to its long half-life, and duloxetine is started at 30 mg/d, with a planned increase to 60 mg/d after 1 to 2 weeks as tolerated to target both mood and migraine prophylaxis. Duloxetine will not interact with Ms. D’s current medication regimen, including lisinopril, women’s multivitamin, or vitamin D3. The psychiatrist discusses the importance of medication adherence to improve her conditions effectively and safely. Ms. D’s heart rate and blood pressure will continue to be monitored.

Related Resources

- Leo RJ, Khalid K. Antidepressants for chronic pain. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(2):8-16,21-22.

- Williams AM, Knox ED. When to prescribe antidepressants to treat comorbid depression and pain disorders. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(1):55-58.

Drug Brand Names

Divalproex • Depakote

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Lisinopril • Zestril, Prinivil

Milnacipran • Savella

Sumatriptan • Imitrex

Topiramate • Topamax

Venlafaxine • Effexor

1. Burch R, Rizzoli P, Loder E. The prevalence and impact of migraine and severe headache in the United States: figures and trends from government health studies. Headache. 2018;58(4):496-505. doi:10.1111/head.13281

2. GBD 2016 Headache Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of migraine and tension-type headache, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(11):954-976. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30322-3

3. Goadsby PJ, Lipton RB, Ferrari MD. Migraine--current understanding and treatment. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(4):257-270. doi:10.1056/NEJMra010917

4. Amoozegar F. Depression comorbidity in migraine. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2017;29(5):504-515. doi:10.1080/09540261.2017.1326882

5. Burch RC, Buse DC, Lipton RB. Migraine: epidemiology, burden, and comorbidity. Neurol Clin. 2019;37(4):631-649. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2019.06.001

6. Ha H, Gonzalez A. Migraine headache prophylaxis. Am Fam Physician. 2019;99(1):17-24.

7. Xu XM, Liu Y, Dong MX, et al. Tricyclic antidepressants for preventing migraine in adults. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(22):e6989. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000006989

8. Burch R. Antidepressants for preventive treatment of migraine. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2019;21(4):18. doi:10.1007/s11940-019-0557-2

9. Venlafaxine. Lexicomp. 2021. http://online.lexi.com/

10. Ogle NR, Akkerman SR. Guidance for the discontinuation or switching of antidepressant therapies in adults. J Pharm Pract. 2013;26(4):389-396. doi:10.1177/0897190012467210

11. Duloxetine [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly and Company; 2004.

12. Young WB, Bradley KC, Anjum MW, et al. Duloxetine prophylaxis for episodic migraine in persons without depression: a prospective study. Headache. 2013;53(9):1430-1437.

13. Duloxetine. Lexicomp. 2021. http://online.lexi.com/

14. Kisler LB, Weissman-Fogel I, Coghill RC, et al. Individualization of migraine prevention: a randomized controlled trial of psychophysical-based prediction of duloxetine efficacy. Clin J Pain. 2019;35(9):753-765.

15. Mansuy L. Antidepressant therapy with milnacipran and venlafaxine. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2010;6 (Suppl I):17-22.

16. Milnacipran. Lexicomp. 2021. http://online.lexi.com/

17. Milnacipran. MedlinePlus. Updated January 22, 2022. Accessed August 19, 2022. https://medlineplus.gov/druginfo/meds/a609016.html

18. Ozyalcin SN, Talu GK, Kiziltan E, et al. The efficacy and safety of venlafaxine in the prophylaxis of migraine. Headache. 2005;45(2):144-152. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.05029.x

19. Adelman LC, Adelman JU, Von Seggern R, et al. Venlafaxine extended release (XR) for the prophylaxis of migraine and tension-type headache: a retrospective study in a clinical setting. Headache. 2000;40(7):572-580. doi:10.1046/j.1526-4610.2000.00089.x

20. Tarlaci S. Escitalopram and venlafaxine for the prophylaxis of migraine headache without mood disorders. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2009;32(5):254-258. doi:10.1097/WNF.0b013e3181a8c84f

21. Engel ER, Kudrow D, Rapoport AM. A prospective, open-label study of milnacipran in the prevention of headache in patients with episodic or chronic migraine. Neurol Sci. 2014;35(3):429-435. doi:10.1007/s10072-013-1536-0

22. Baumgartner A, Drame K, Geutjens S, et al. Does the polypill improve patient adherence compared to its individual formulations? A systematic review. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12(2):190.

Ms. D, age 45, has major depressive disorder (MDD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), migraines, and hypertension. At a follow-up visit, she says she has been under a lot of stress at work in the past several months and feels her antidepressant is not working well for her depression or anxiety. Ms. D notes that lately she has had more frequent migraines, occurring approximately 4 times per month during the past 3 months. She describes a severe throbbing frontal pain that occurs primarily on the left side of her head, but sometimes on the right side. Ms. D says she experiences nausea, vomiting, and photophobia during these migraine episodes. The migraines last up to 12 hours, but often resolve with sumatriptan 50 mg as needed.

Ms. D takes fluoxetine 60 mg/d for depression and anxiety, lisinopril 20 mg/d for hypertension, as well as a women’s multivitamin and vitamin D3 daily. She has not tried other antidepressants and misses doses of her medications about once every other week. Her blood pressure is 125/80 mm Hg; heart rate is 80 beats per minute; and temperature is 37° C. Ms. D’s treatment team is considering switching her to a medication that can act as preventative therapy for migraines while also treating her depression and anxiety.

Migraine is a chronic, disabling neurovascular disorder that affects approximately 15% of the United States population.1 It is the second-leading disabling condition worldwide and may negatively affect social, family, personal, academic, and occupational domains.2 Migraine is often characterized by throbbing pain, is frequently unilateral, and may last 24 to 72 hours.3 It may occur with or without aura and can be associated with nausea, vomiting, or sensitivity to light.3 Episodic migraines occur <15 days a month, while chronic migraines occur ≥15 days a month.4

Many psychiatric, neurologic, vascular, and cardiac comorbidities are more prevalent in individuals who experience migraine headaches compared to the general population. Common psychiatric comorbidities found in patients with migraines are depression, bipolar disorder, GAD, panic disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder5; MDD is the most common.4 A person who experiences migraine headaches is 2 to 4 times more likely to develop MDD than one who does not experience migraine headaches.4

First-line treatments for preventing migraine including divalproex, topiramate, metoprolol, propranolol, and timolol.6 However, for some patients with migraines and comorbid depression or anxiety, an antidepressant may be an option. This article briefly reviews the evidence for using antidepressants that have been studied for their ability to decrease migraine frequency.

Antidepressants that can prevent migraine

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are second- or third-line options for migraine prevention.6 While TCAs have proven to be effective for preventing migraines, many patients are unable to tolerate their adverse effects (ie, anticholinergic effects, sedation).7 TCAs may be more appealing for younger patients, who may be less bothered by anticholinergic burden, or those who have difficulty sleeping.

Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). There has been growing interest in understanding the potential utility of SNRIs as a preventative treatment for migraines. Research has found that SNRIs are as effective as TCAs for preventing migraines and also more tolerable in terms of adverse effects.7 SNRIs such as venlafaxine and duloxetine are currently prescribed off-label to prevent migraines despite a lack of FDA approval for this indication.8

Continue to: Understanding the safety and efficacy...

Understanding the safety and efficacy of SNRIs as preventative treatment for episodic migraines is useful, particularly for patients with comorbid depression. The Table8-17 details clinical information related to SNRI use.

Duloxetine has demonstrated efficacy in preventing migraines in patients with comorbid depression.8 In a 2019 study, Kisler et al14 found that duloxetine 60 mg/d for 7 weeks was more effective for migraine prophylaxis than placebo as measured by the percentage of self-estimated migraine improvement by each patient compared to pretreatment levels (duloxetine: 52.3% ± 30.4%; placebo: 26.0% ± 27.3%; P = .001).

Venlafaxine has also demonstrated efficacy for preventing migraines in patients with comorbid depression.8 One study demonstrated a significant decrease in headaches per month with the use of venlafaxine 150 mg/d compared to placebo.18 Adelman et al19 found a reduction in migraine headaches per month (16.1 to 11.1, P < .0001) in patients who took venlafaxine for an average of 6 months with a mean dose of 150 mg/d. In a study of patients who did not have a mood disorder, Tarlaci20 found that venlafaxine reduced migraine headache independent of its antidepressant action.

Though milnacipran has not been studied as extensively as other SNRIs, evidence suggests it reduces the incidence of headaches and migraines, especially among episodic migraine patients. Although it has an equipotent effect on both serotonin and norepinephrine (NE) reuptake, milnacipran has a greater NE effect compared to other SNRIs approved for treating mood disorders. A prospective, single-arm study by Engel et al21 found a significant (P < .005) reduction from baseline in all headache and migraine days per month with the use of milnacipran 100 mg/d over the course of 3 months. The number of headache days per month was reduced by 4.2 compared to baseline. This same study reported improved functionality and reduced use of acute and symptomatic medications overall due to the decrease in headaches and migraines.21

In addition to demonstrating that certain SNRIs can effectively prevent migraine, some evidence suggests certain patients may benefit from the opportunity to decrease pill burden by using a single medication to treat both depression and migraine.22 Duloxetine may be preferred for patients who struggle with adherence (such as Ms. D) due to its relatively lower incidence of withdrawal symptoms compared to venlafaxine.8

CASE CONTINUED

Ms. D’s psychiatrist concludes she would be an appropriate candidate for treatment with an SNRI due to her history of MDD and chronic migraines. Because Ms. D expresses some difficulty remembering to take her medications, the psychiatrist recommends duloxetine because it is less likely to produce withdrawal symptoms compared to venlafaxine. To decrease pill burden, fluoxetine 60 mg is stopped with no taper due to its long half-life, and duloxetine is started at 30 mg/d, with a planned increase to 60 mg/d after 1 to 2 weeks as tolerated to target both mood and migraine prophylaxis. Duloxetine will not interact with Ms. D’s current medication regimen, including lisinopril, women’s multivitamin, or vitamin D3. The psychiatrist discusses the importance of medication adherence to improve her conditions effectively and safely. Ms. D’s heart rate and blood pressure will continue to be monitored.

Related Resources

- Leo RJ, Khalid K. Antidepressants for chronic pain. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(2):8-16,21-22.

- Williams AM, Knox ED. When to prescribe antidepressants to treat comorbid depression and pain disorders. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(1):55-58.

Drug Brand Names

Divalproex • Depakote

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Lisinopril • Zestril, Prinivil

Milnacipran • Savella

Sumatriptan • Imitrex

Topiramate • Topamax

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Ms. D, age 45, has major depressive disorder (MDD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), migraines, and hypertension. At a follow-up visit, she says she has been under a lot of stress at work in the past several months and feels her antidepressant is not working well for her depression or anxiety. Ms. D notes that lately she has had more frequent migraines, occurring approximately 4 times per month during the past 3 months. She describes a severe throbbing frontal pain that occurs primarily on the left side of her head, but sometimes on the right side. Ms. D says she experiences nausea, vomiting, and photophobia during these migraine episodes. The migraines last up to 12 hours, but often resolve with sumatriptan 50 mg as needed.

Ms. D takes fluoxetine 60 mg/d for depression and anxiety, lisinopril 20 mg/d for hypertension, as well as a women’s multivitamin and vitamin D3 daily. She has not tried other antidepressants and misses doses of her medications about once every other week. Her blood pressure is 125/80 mm Hg; heart rate is 80 beats per minute; and temperature is 37° C. Ms. D’s treatment team is considering switching her to a medication that can act as preventative therapy for migraines while also treating her depression and anxiety.

Migraine is a chronic, disabling neurovascular disorder that affects approximately 15% of the United States population.1 It is the second-leading disabling condition worldwide and may negatively affect social, family, personal, academic, and occupational domains.2 Migraine is often characterized by throbbing pain, is frequently unilateral, and may last 24 to 72 hours.3 It may occur with or without aura and can be associated with nausea, vomiting, or sensitivity to light.3 Episodic migraines occur <15 days a month, while chronic migraines occur ≥15 days a month.4

Many psychiatric, neurologic, vascular, and cardiac comorbidities are more prevalent in individuals who experience migraine headaches compared to the general population. Common psychiatric comorbidities found in patients with migraines are depression, bipolar disorder, GAD, panic disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder5; MDD is the most common.4 A person who experiences migraine headaches is 2 to 4 times more likely to develop MDD than one who does not experience migraine headaches.4

First-line treatments for preventing migraine including divalproex, topiramate, metoprolol, propranolol, and timolol.6 However, for some patients with migraines and comorbid depression or anxiety, an antidepressant may be an option. This article briefly reviews the evidence for using antidepressants that have been studied for their ability to decrease migraine frequency.

Antidepressants that can prevent migraine

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are second- or third-line options for migraine prevention.6 While TCAs have proven to be effective for preventing migraines, many patients are unable to tolerate their adverse effects (ie, anticholinergic effects, sedation).7 TCAs may be more appealing for younger patients, who may be less bothered by anticholinergic burden, or those who have difficulty sleeping.

Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). There has been growing interest in understanding the potential utility of SNRIs as a preventative treatment for migraines. Research has found that SNRIs are as effective as TCAs for preventing migraines and also more tolerable in terms of adverse effects.7 SNRIs such as venlafaxine and duloxetine are currently prescribed off-label to prevent migraines despite a lack of FDA approval for this indication.8

Continue to: Understanding the safety and efficacy...

Understanding the safety and efficacy of SNRIs as preventative treatment for episodic migraines is useful, particularly for patients with comorbid depression. The Table8-17 details clinical information related to SNRI use.

Duloxetine has demonstrated efficacy in preventing migraines in patients with comorbid depression.8 In a 2019 study, Kisler et al14 found that duloxetine 60 mg/d for 7 weeks was more effective for migraine prophylaxis than placebo as measured by the percentage of self-estimated migraine improvement by each patient compared to pretreatment levels (duloxetine: 52.3% ± 30.4%; placebo: 26.0% ± 27.3%; P = .001).

Venlafaxine has also demonstrated efficacy for preventing migraines in patients with comorbid depression.8 One study demonstrated a significant decrease in headaches per month with the use of venlafaxine 150 mg/d compared to placebo.18 Adelman et al19 found a reduction in migraine headaches per month (16.1 to 11.1, P < .0001) in patients who took venlafaxine for an average of 6 months with a mean dose of 150 mg/d. In a study of patients who did not have a mood disorder, Tarlaci20 found that venlafaxine reduced migraine headache independent of its antidepressant action.

Though milnacipran has not been studied as extensively as other SNRIs, evidence suggests it reduces the incidence of headaches and migraines, especially among episodic migraine patients. Although it has an equipotent effect on both serotonin and norepinephrine (NE) reuptake, milnacipran has a greater NE effect compared to other SNRIs approved for treating mood disorders. A prospective, single-arm study by Engel et al21 found a significant (P < .005) reduction from baseline in all headache and migraine days per month with the use of milnacipran 100 mg/d over the course of 3 months. The number of headache days per month was reduced by 4.2 compared to baseline. This same study reported improved functionality and reduced use of acute and symptomatic medications overall due to the decrease in headaches and migraines.21

In addition to demonstrating that certain SNRIs can effectively prevent migraine, some evidence suggests certain patients may benefit from the opportunity to decrease pill burden by using a single medication to treat both depression and migraine.22 Duloxetine may be preferred for patients who struggle with adherence (such as Ms. D) due to its relatively lower incidence of withdrawal symptoms compared to venlafaxine.8

CASE CONTINUED

Ms. D’s psychiatrist concludes she would be an appropriate candidate for treatment with an SNRI due to her history of MDD and chronic migraines. Because Ms. D expresses some difficulty remembering to take her medications, the psychiatrist recommends duloxetine because it is less likely to produce withdrawal symptoms compared to venlafaxine. To decrease pill burden, fluoxetine 60 mg is stopped with no taper due to its long half-life, and duloxetine is started at 30 mg/d, with a planned increase to 60 mg/d after 1 to 2 weeks as tolerated to target both mood and migraine prophylaxis. Duloxetine will not interact with Ms. D’s current medication regimen, including lisinopril, women’s multivitamin, or vitamin D3. The psychiatrist discusses the importance of medication adherence to improve her conditions effectively and safely. Ms. D’s heart rate and blood pressure will continue to be monitored.

Related Resources

- Leo RJ, Khalid K. Antidepressants for chronic pain. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(2):8-16,21-22.

- Williams AM, Knox ED. When to prescribe antidepressants to treat comorbid depression and pain disorders. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(1):55-58.

Drug Brand Names

Divalproex • Depakote

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Lisinopril • Zestril, Prinivil

Milnacipran • Savella

Sumatriptan • Imitrex

Topiramate • Topamax

Venlafaxine • Effexor

1. Burch R, Rizzoli P, Loder E. The prevalence and impact of migraine and severe headache in the United States: figures and trends from government health studies. Headache. 2018;58(4):496-505. doi:10.1111/head.13281

2. GBD 2016 Headache Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of migraine and tension-type headache, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(11):954-976. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30322-3

3. Goadsby PJ, Lipton RB, Ferrari MD. Migraine--current understanding and treatment. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(4):257-270. doi:10.1056/NEJMra010917

4. Amoozegar F. Depression comorbidity in migraine. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2017;29(5):504-515. doi:10.1080/09540261.2017.1326882

5. Burch RC, Buse DC, Lipton RB. Migraine: epidemiology, burden, and comorbidity. Neurol Clin. 2019;37(4):631-649. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2019.06.001

6. Ha H, Gonzalez A. Migraine headache prophylaxis. Am Fam Physician. 2019;99(1):17-24.

7. Xu XM, Liu Y, Dong MX, et al. Tricyclic antidepressants for preventing migraine in adults. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(22):e6989. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000006989

8. Burch R. Antidepressants for preventive treatment of migraine. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2019;21(4):18. doi:10.1007/s11940-019-0557-2

9. Venlafaxine. Lexicomp. 2021. http://online.lexi.com/

10. Ogle NR, Akkerman SR. Guidance for the discontinuation or switching of antidepressant therapies in adults. J Pharm Pract. 2013;26(4):389-396. doi:10.1177/0897190012467210

11. Duloxetine [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly and Company; 2004.

12. Young WB, Bradley KC, Anjum MW, et al. Duloxetine prophylaxis for episodic migraine in persons without depression: a prospective study. Headache. 2013;53(9):1430-1437.

13. Duloxetine. Lexicomp. 2021. http://online.lexi.com/

14. Kisler LB, Weissman-Fogel I, Coghill RC, et al. Individualization of migraine prevention: a randomized controlled trial of psychophysical-based prediction of duloxetine efficacy. Clin J Pain. 2019;35(9):753-765.

15. Mansuy L. Antidepressant therapy with milnacipran and venlafaxine. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2010;6 (Suppl I):17-22.

16. Milnacipran. Lexicomp. 2021. http://online.lexi.com/

17. Milnacipran. MedlinePlus. Updated January 22, 2022. Accessed August 19, 2022. https://medlineplus.gov/druginfo/meds/a609016.html

18. Ozyalcin SN, Talu GK, Kiziltan E, et al. The efficacy and safety of venlafaxine in the prophylaxis of migraine. Headache. 2005;45(2):144-152. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.05029.x

19. Adelman LC, Adelman JU, Von Seggern R, et al. Venlafaxine extended release (XR) for the prophylaxis of migraine and tension-type headache: a retrospective study in a clinical setting. Headache. 2000;40(7):572-580. doi:10.1046/j.1526-4610.2000.00089.x

20. Tarlaci S. Escitalopram and venlafaxine for the prophylaxis of migraine headache without mood disorders. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2009;32(5):254-258. doi:10.1097/WNF.0b013e3181a8c84f

21. Engel ER, Kudrow D, Rapoport AM. A prospective, open-label study of milnacipran in the prevention of headache in patients with episodic or chronic migraine. Neurol Sci. 2014;35(3):429-435. doi:10.1007/s10072-013-1536-0

22. Baumgartner A, Drame K, Geutjens S, et al. Does the polypill improve patient adherence compared to its individual formulations? A systematic review. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12(2):190.

1. Burch R, Rizzoli P, Loder E. The prevalence and impact of migraine and severe headache in the United States: figures and trends from government health studies. Headache. 2018;58(4):496-505. doi:10.1111/head.13281

2. GBD 2016 Headache Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of migraine and tension-type headache, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(11):954-976. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30322-3

3. Goadsby PJ, Lipton RB, Ferrari MD. Migraine--current understanding and treatment. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(4):257-270. doi:10.1056/NEJMra010917

4. Amoozegar F. Depression comorbidity in migraine. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2017;29(5):504-515. doi:10.1080/09540261.2017.1326882

5. Burch RC, Buse DC, Lipton RB. Migraine: epidemiology, burden, and comorbidity. Neurol Clin. 2019;37(4):631-649. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2019.06.001

6. Ha H, Gonzalez A. Migraine headache prophylaxis. Am Fam Physician. 2019;99(1):17-24.

7. Xu XM, Liu Y, Dong MX, et al. Tricyclic antidepressants for preventing migraine in adults. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(22):e6989. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000006989

8. Burch R. Antidepressants for preventive treatment of migraine. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2019;21(4):18. doi:10.1007/s11940-019-0557-2

9. Venlafaxine. Lexicomp. 2021. http://online.lexi.com/

10. Ogle NR, Akkerman SR. Guidance for the discontinuation or switching of antidepressant therapies in adults. J Pharm Pract. 2013;26(4):389-396. doi:10.1177/0897190012467210

11. Duloxetine [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly and Company; 2004.

12. Young WB, Bradley KC, Anjum MW, et al. Duloxetine prophylaxis for episodic migraine in persons without depression: a prospective study. Headache. 2013;53(9):1430-1437.

13. Duloxetine. Lexicomp. 2021. http://online.lexi.com/

14. Kisler LB, Weissman-Fogel I, Coghill RC, et al. Individualization of migraine prevention: a randomized controlled trial of psychophysical-based prediction of duloxetine efficacy. Clin J Pain. 2019;35(9):753-765.

15. Mansuy L. Antidepressant therapy with milnacipran and venlafaxine. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2010;6 (Suppl I):17-22.

16. Milnacipran. Lexicomp. 2021. http://online.lexi.com/

17. Milnacipran. MedlinePlus. Updated January 22, 2022. Accessed August 19, 2022. https://medlineplus.gov/druginfo/meds/a609016.html

18. Ozyalcin SN, Talu GK, Kiziltan E, et al. The efficacy and safety of venlafaxine in the prophylaxis of migraine. Headache. 2005;45(2):144-152. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.05029.x

19. Adelman LC, Adelman JU, Von Seggern R, et al. Venlafaxine extended release (XR) for the prophylaxis of migraine and tension-type headache: a retrospective study in a clinical setting. Headache. 2000;40(7):572-580. doi:10.1046/j.1526-4610.2000.00089.x

20. Tarlaci S. Escitalopram and venlafaxine for the prophylaxis of migraine headache without mood disorders. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2009;32(5):254-258. doi:10.1097/WNF.0b013e3181a8c84f

21. Engel ER, Kudrow D, Rapoport AM. A prospective, open-label study of milnacipran in the prevention of headache in patients with episodic or chronic migraine. Neurol Sci. 2014;35(3):429-435. doi:10.1007/s10072-013-1536-0

22. Baumgartner A, Drame K, Geutjens S, et al. Does the polypill improve patient adherence compared to its individual formulations? A systematic review. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12(2):190.

How bariatric surgery affects psychotropic drug absorption

Ms. B, age 60, presents to the clinic with high blood pressure, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus, depression, and anxiety. Her blood pressure is 138/82 mm Hg and pulse is 70 beats per minute. Her body mass index (BMI) is 41, which indicates she is obese. She has always struggled with her weight and has tried diet and lifestyle modifications, as well as medications, for the past 5 years with no success. Her current medication regimen includes lisinopril 40 mg daily, amlodipine 5 mg daily, atorvastatin 40 mg daily, metformin 500 mg twice daily, dulaglutide 0.75 mg weekly, lithium 600 mg daily, venlafaxine extended-release (XR) 150 mg daily, and alprazolam 0.5 mg as needed up to twice daily. Due to Ms. B’s BMI and because she has ≥1 comorbid health condition, her primary care physician refers her to a gastroenterologist to discuss gastric bypass surgery options.

Ms. B is scheduled for Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. You need to determine if any changes should be made to her psychotropic medications after she undergoes this surgery.

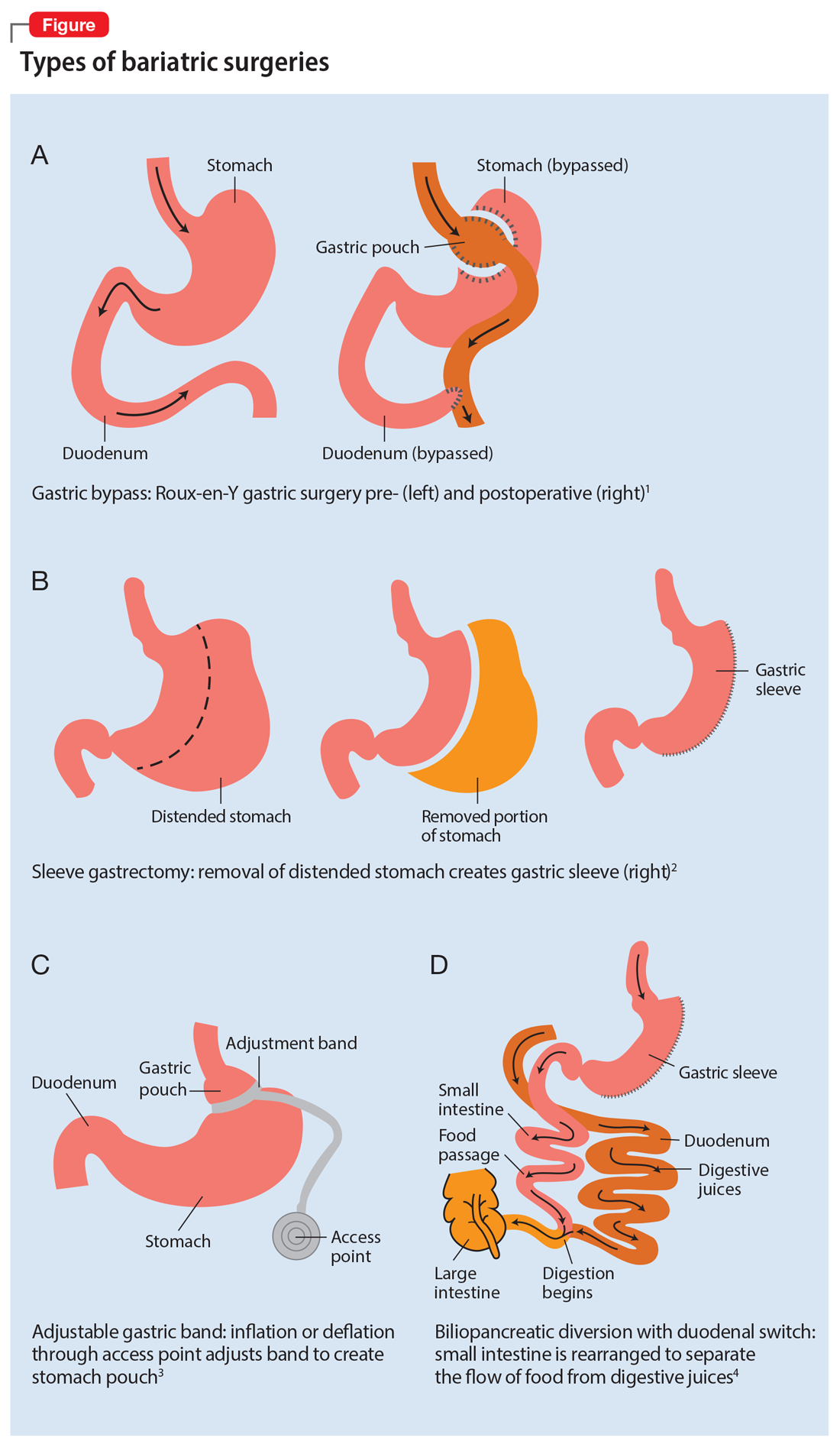

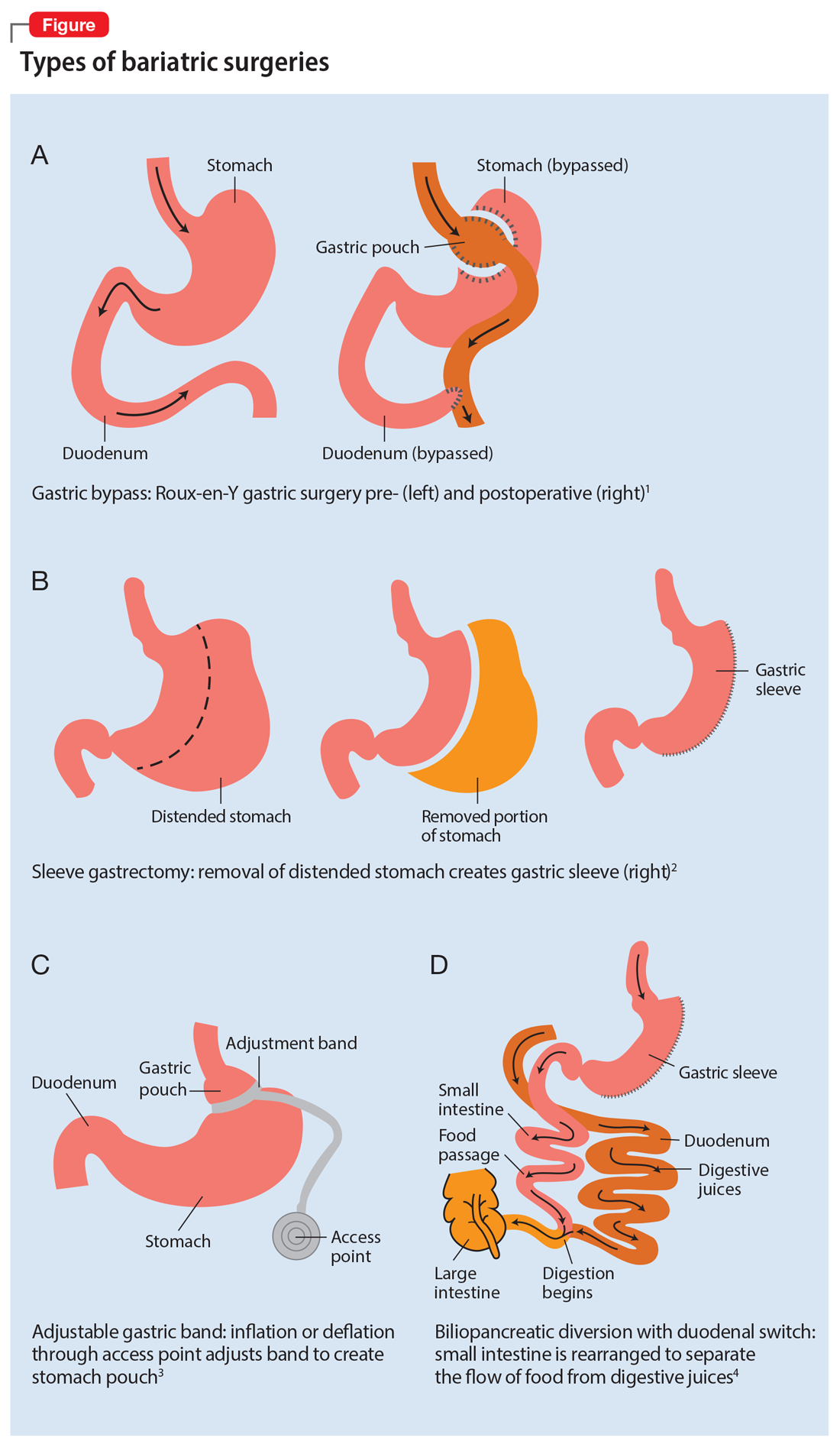

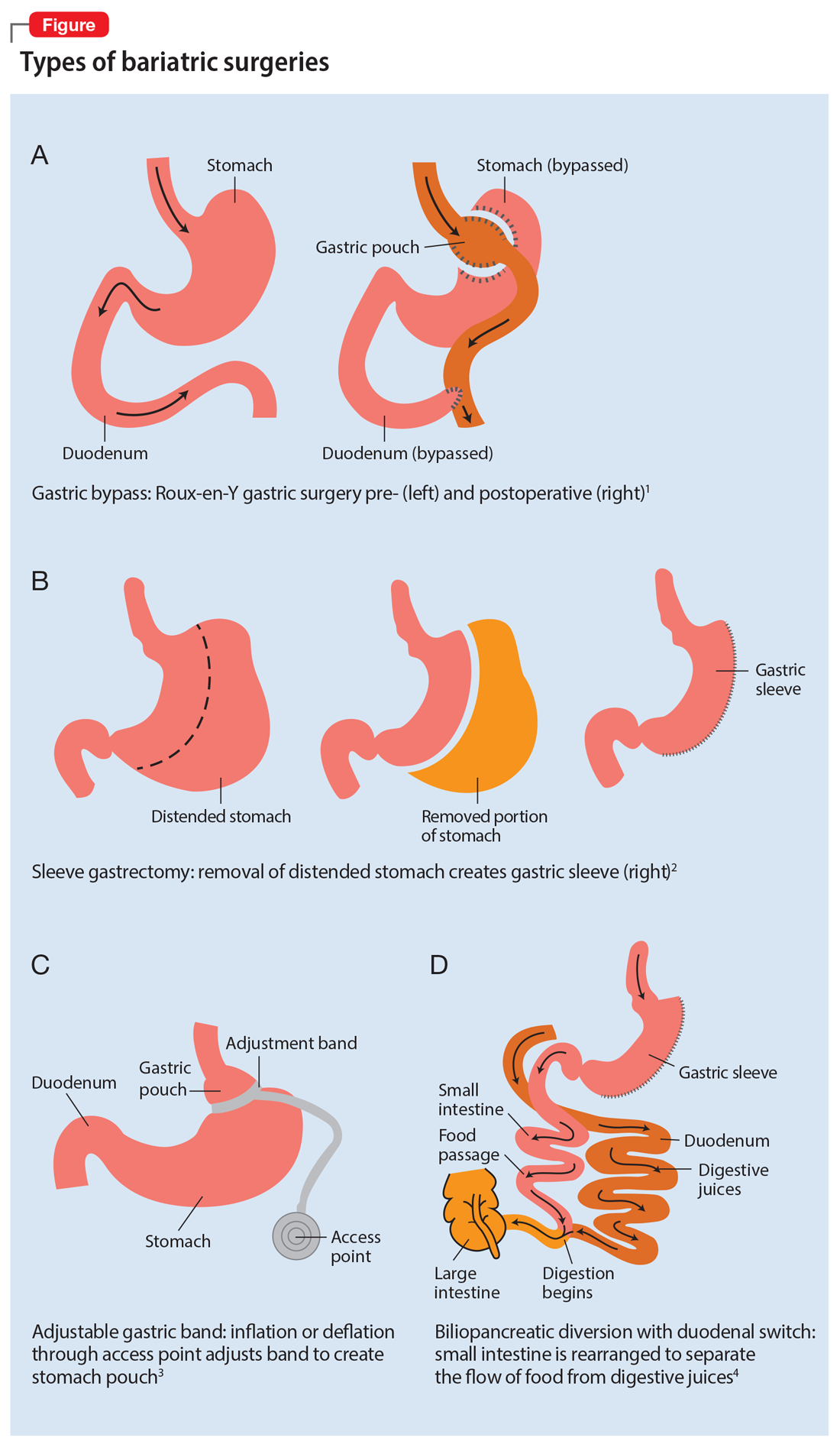

There are multiple types of bariatric surgeries, including Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, laparoscopic adjustable gastric band, and biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD/DS) (Figure1-4). These procedures all restrict the stomach’s capacity to hold food. In most cases, they also bypass areas of absorption in the intestine and cause increased secretion of hormones in the gut, including (but not limited to) peptide-YY (PYY) and glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1). These hormonal changes impact several factors, including satiety, hunger, and blood sugar levels.5

Roux-en-Y is commonly referred to as the gold standard of weight loss surgery. It divides the top of the stomach into a smaller stomach pouch that connects directly to the small intestine to facilitate smaller meals and alters the release of gut hormones. Additionally, a segment of the small intestine that normally absorbs nutrients and medications is completely bypassed. In contrast, the sleeve gastrectomy removes approximately 80% of the stomach, consequently reducing the amount of food that can be consumed. The greatest impact of the sleeve gastrectomy procedure appears to result from changes in gut hormones. The adjustable gastric band procedure works by placing a band around the upper portion of the stomach to create a small pouch above the band to satisfy hunger with a smaller amount of food. Lastly, BPD/DS is a procedure that creates a tubular stomach pouch and bypasses a large portion of the small intestine. Like the gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy, BPD/DS affects gut hormones impacting hunger, satiety, and blood sugar control.

How bariatric surgery can affect drug absorption

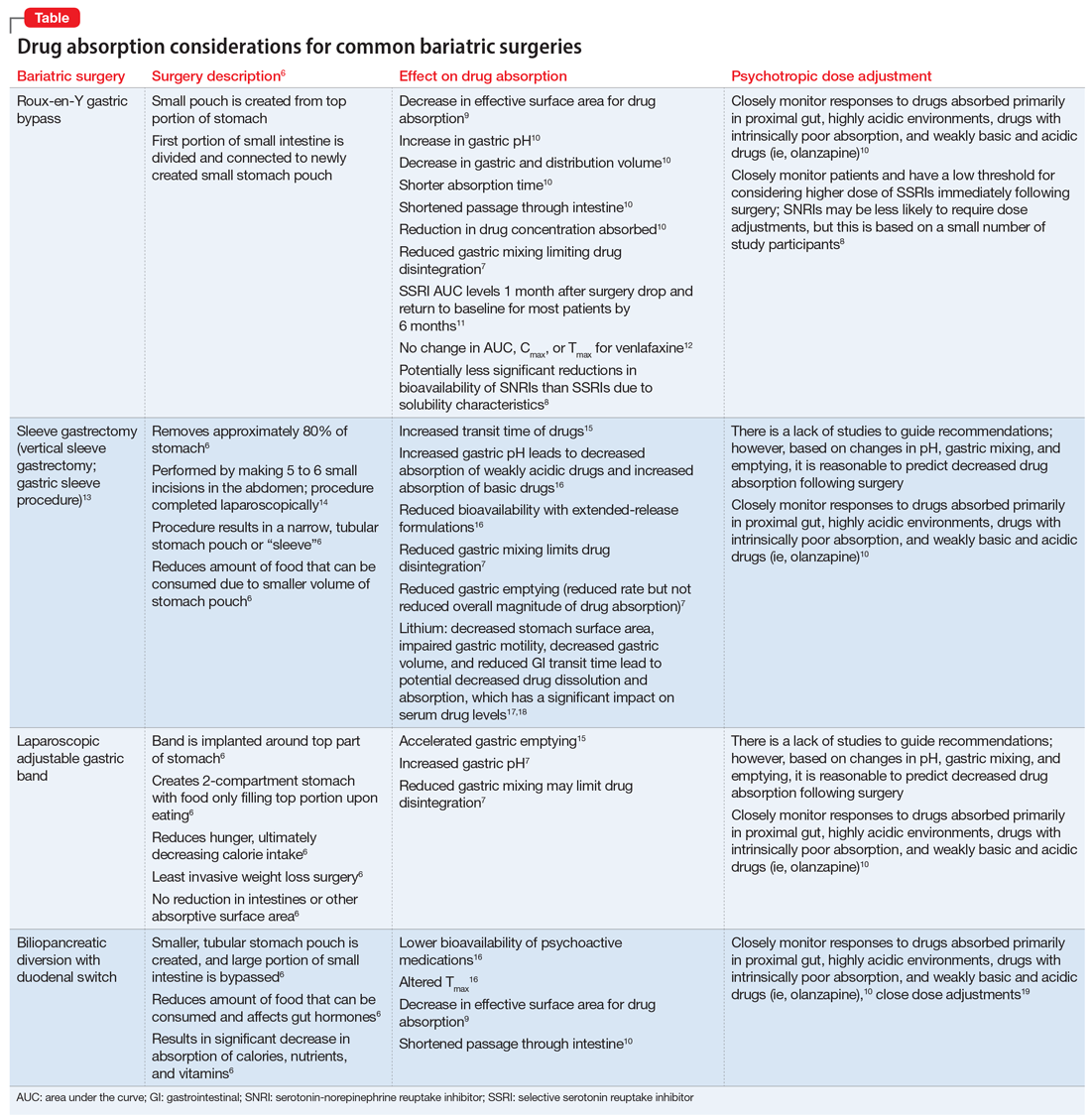

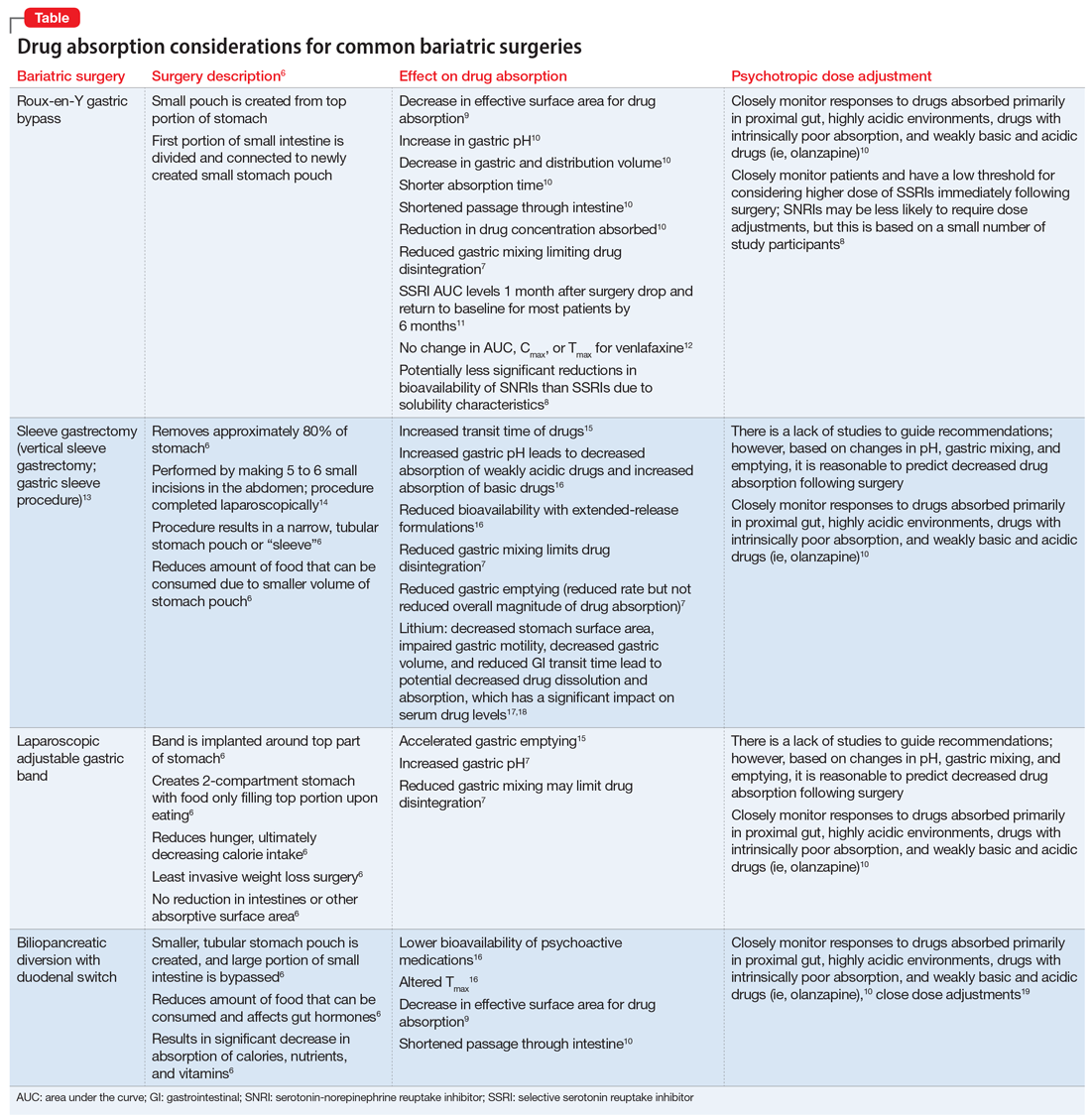

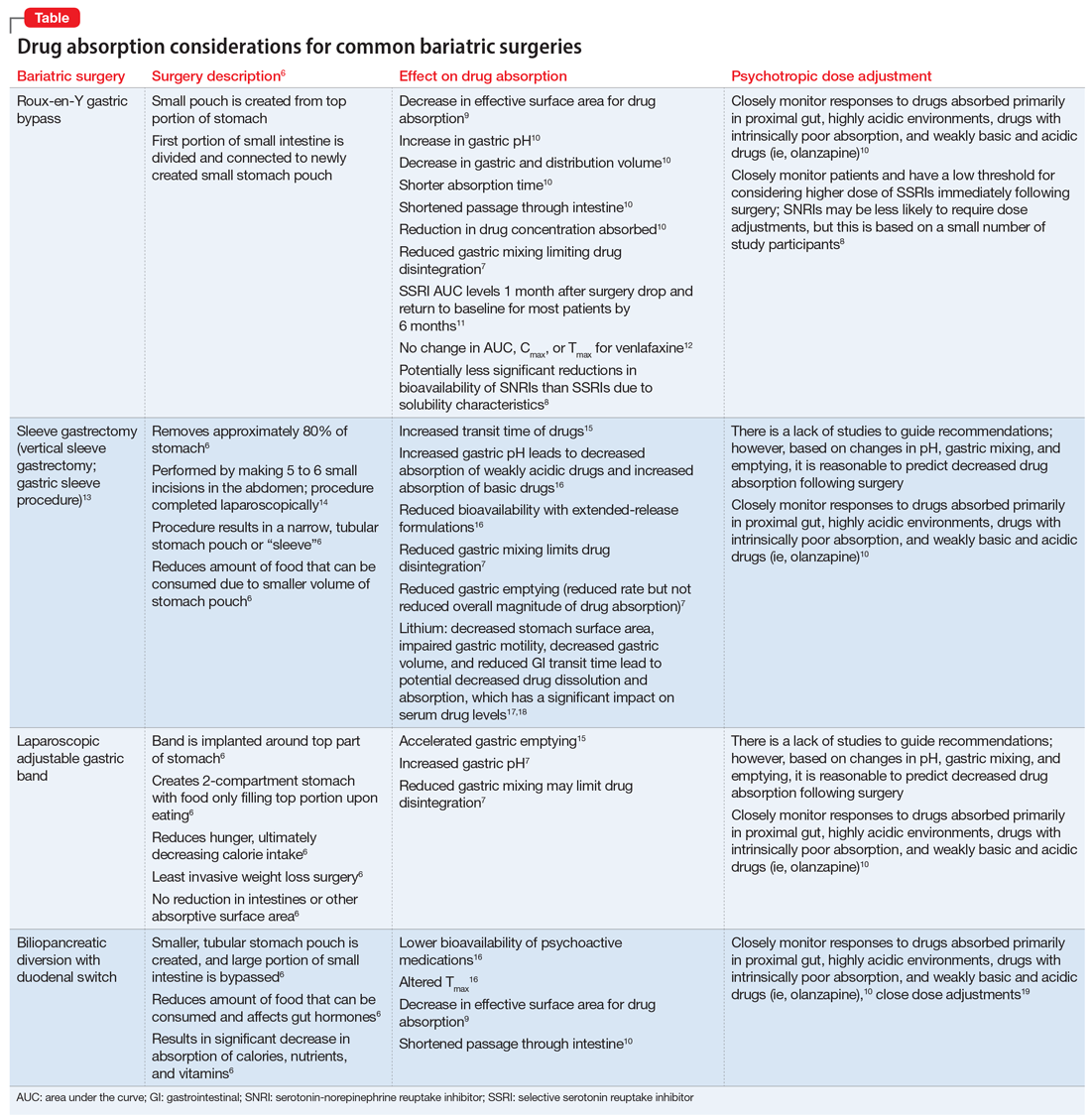

As illustrated in the Table,6-19 each type of bariatric surgery may impact drug absorption differently depending on the mechanism by which the stomach is restricted.

Drug malabsorption is a concern for clinicians with patients who have undergone bariatric surgery. There is limited research measuring changes in psychotropic exposure and outcomes following bariatric surgery. A 2009 literature review by Padwal et al7 found that one-third of the 26 studies evaluated provided evidence of decreased absorption following bariatric surgery in patients taking medications that had intrinsic poor absorption, high lipophilicity, and/or undergo enterohepatic recirculation. In a review that included a small study of patients taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or venlafaxine, Godini et al8 demonstrated that although there was a notable decrease in drug absorption closely following the surgery, drug absorption recovered for some patients 1 month after Roux-en-Y surgery. These reviews suggest patients who have undergone any form of bariatric surgery must be observed closely because drug absorption may vary based on the individual, the medication administered, and the amount of time postprocedure.

Until more research becomes available, current evidence supports recommendations to assist patients who have a decreased ability to absorb medications after gastric bypass surgery by switching from an extended-release formulation to an immediate-release or solution formulation. This allows patients to rely less on gastric mixing and unpredictable changes in drug release from extended- or controlled-release formulations.

Continue to: Aside from altered...

Aside from altered pharmacokinetics after bariatric surgery, many patients experience an increased risk of self-harm and suicide.20 Therefore, a continued emphasis on and reinforcement of proper antidepressant use and adjustment in these patients is important. This can be facilitated through frequent follow-up visits, either in-person or via telehealth.

Understanding the effect of bariatric surgery on drug absorption is critical to identifying a potential need to adjust a medication dose or formulation after the surgery. Available evidence and data suggest it is reasonable to switch from an extended- or sustained-release formulation to an immediate-release formulation, and to monitor patients more frequently immediately following the surgery.

CASE CONTINUED

Related Resources

- Colvin C, Tsia W, Silverman AL, et al. Nothing up his sleeve: decompensation after bariatric surgery. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(4):15-19. doi:10.12788/cp.010

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax

Amlodipine • Norvasc

Atorvastatin • Lipitor

Dulaglutide • Trulicity

Lisinopril • Zestril, Prinivil

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Metformin • Glucophage

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Venlafaxine • Effexor

1. Obesity Treatments: Gastric Bypass Surgery. UCLA Health. Accessed April 4, 2021. http://surgery.ucla.edu/bariatrics-gastric-bypass

2. Thomas L. Gastric bypass more likely to require further treatment than gastric sleeve. News Medical. January 15, 2020. Accessed April 4, 2021. https://www.news-medical.net/news/20200115/Gastric-bypass-more-likely-to-require-further-treatment-than-gastric-sleeve.aspx

3. Lap Adjustable Gastric Banding. Laser Stone Surgery & Endoscopy Centre. September 5, 2016. Accessed April 4, 2021. http://www.laserstonesurgery.org/project/lap-adjustable-gastric-banding/

4. BPD/DS Weight-Loss Surgery. Johns Hopkins Medicine. Accessed April 4, 2021. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/treatment-tests-and-therapies/bpdds-weightloss-surgery

5. Holst JJ, Madsbad S, Bojsen-Møller KN, et al. Mechanisms in bariatric surgery: gut hormones, diabetes resolution, and weight loss. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14(5):708-714. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2018.03.003

6. Public Education Committee. Bariatric Surgery Procedures. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. Updated May 2021. Accessed September 4, 2021. https://asmbs.org/patients/bariatric-surgery-procedures

7. Padwal R, Brocks D, Sharma AM. A systematic review of drug absorption following bariatric surgery and its theoretical implications. Obes Rev. 2010;11(1):41-50. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789x.2009.00614.x

8. Godini L, Castellini G, Facchiano E, et al. Mood disorders and bariatric surgery patients: pre- and post- surgery clinical course- an overview. J Obes Weight Loss Medicat. 2016;2(1). doi:10.23937/2572-4010.1510012

9. Smith A, Henriksen B, Cohen A. Pharmacokinetic considerations in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass patients. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2011;68(23):2241-2247. doi:10.2146/ajhp100630

10. Brocks DR, Ben-Eltriki M, Gabr RQ, et al. The effects of gastric bypass surgery on drug absorption and pharmacokinetics. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2012;8(12):1505-1519. doi:10.1517/17425255.2012.722757

11. Hamad GG, Helsel JC, Perel JM, et al. The effect of gastric bypass on the pharmacokinetics of serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(3):256-263. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11050719

12. Angeles PC, Robertsen I, Seeberg LT, et al. The influence of bariatric surgery on oral drug bioavailability in patients with obesity: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2019;20(9):1299-1311. doi:10.1111/obr.12869

13. Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy. University of California San Francisco Department of Surgery. Accessed April 1, 2021. https://surgery.ucsf.edu/conditions--procedures/laparoscopic-sleeve-gastrectomy.aspx

14. Brethauer S, Schauer P. Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy: A Newcomer to Bariatric Surgery. Obesity Action Coalition. 2007. Accessed May 15, 2021. https://www.obesityaction.org/community/article-library/laparoscopic-sleeve-gastrectomy-a-newcomer-to-bariatric-surgery/

15. Roerig JL, Steffen K. Psychopharmacology and bariatric surgery. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2015;23(6):463-469. doi:10.1002/erv.2396

16. Bland CM, Quidley AM, Love BL, et al. Long-term pharmacotherapy considerations in the bariatric surgery patient. A J Health Syst Pharm. 2016;73(16):1230-1242. doi:10.2146/ajhp151062

17. Lin YH, Liu SW, Wu HL, et al. Lithium toxicity with prolonged neurologic sequelae following sleeve gastrectomy: a case report and review of literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(28):e21122. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000021122

18. Lorico S, Colton B. Medication management and pharmacokinetic changes after bariatric surgery. Can Fam Physician. 2020;66(6):409-416.

19. Homan J, Schijns W, Aarts EO, et al. Treatment of vitamin and mineral deficiencies after biliopancreatic diversion with or without duodenal switch: a major challenge. Obes Surg. 2018;28(1):234-241. doi:10.1007/s11695-017-2841-0

20. Neovius M, Bruze G, Jacobson P, et al. Risk of suicide and non-fatal self-harm after bariatric surgery: results from two matched cohort studies. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6(3):197-207. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30437-0

Ms. B, age 60, presents to the clinic with high blood pressure, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus, depression, and anxiety. Her blood pressure is 138/82 mm Hg and pulse is 70 beats per minute. Her body mass index (BMI) is 41, which indicates she is obese. She has always struggled with her weight and has tried diet and lifestyle modifications, as well as medications, for the past 5 years with no success. Her current medication regimen includes lisinopril 40 mg daily, amlodipine 5 mg daily, atorvastatin 40 mg daily, metformin 500 mg twice daily, dulaglutide 0.75 mg weekly, lithium 600 mg daily, venlafaxine extended-release (XR) 150 mg daily, and alprazolam 0.5 mg as needed up to twice daily. Due to Ms. B’s BMI and because she has ≥1 comorbid health condition, her primary care physician refers her to a gastroenterologist to discuss gastric bypass surgery options.

Ms. B is scheduled for Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. You need to determine if any changes should be made to her psychotropic medications after she undergoes this surgery.

There are multiple types of bariatric surgeries, including Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, laparoscopic adjustable gastric band, and biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD/DS) (Figure1-4). These procedures all restrict the stomach’s capacity to hold food. In most cases, they also bypass areas of absorption in the intestine and cause increased secretion of hormones in the gut, including (but not limited to) peptide-YY (PYY) and glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1). These hormonal changes impact several factors, including satiety, hunger, and blood sugar levels.5

Roux-en-Y is commonly referred to as the gold standard of weight loss surgery. It divides the top of the stomach into a smaller stomach pouch that connects directly to the small intestine to facilitate smaller meals and alters the release of gut hormones. Additionally, a segment of the small intestine that normally absorbs nutrients and medications is completely bypassed. In contrast, the sleeve gastrectomy removes approximately 80% of the stomach, consequently reducing the amount of food that can be consumed. The greatest impact of the sleeve gastrectomy procedure appears to result from changes in gut hormones. The adjustable gastric band procedure works by placing a band around the upper portion of the stomach to create a small pouch above the band to satisfy hunger with a smaller amount of food. Lastly, BPD/DS is a procedure that creates a tubular stomach pouch and bypasses a large portion of the small intestine. Like the gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy, BPD/DS affects gut hormones impacting hunger, satiety, and blood sugar control.

How bariatric surgery can affect drug absorption

As illustrated in the Table,6-19 each type of bariatric surgery may impact drug absorption differently depending on the mechanism by which the stomach is restricted.

Drug malabsorption is a concern for clinicians with patients who have undergone bariatric surgery. There is limited research measuring changes in psychotropic exposure and outcomes following bariatric surgery. A 2009 literature review by Padwal et al7 found that one-third of the 26 studies evaluated provided evidence of decreased absorption following bariatric surgery in patients taking medications that had intrinsic poor absorption, high lipophilicity, and/or undergo enterohepatic recirculation. In a review that included a small study of patients taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or venlafaxine, Godini et al8 demonstrated that although there was a notable decrease in drug absorption closely following the surgery, drug absorption recovered for some patients 1 month after Roux-en-Y surgery. These reviews suggest patients who have undergone any form of bariatric surgery must be observed closely because drug absorption may vary based on the individual, the medication administered, and the amount of time postprocedure.

Until more research becomes available, current evidence supports recommendations to assist patients who have a decreased ability to absorb medications after gastric bypass surgery by switching from an extended-release formulation to an immediate-release or solution formulation. This allows patients to rely less on gastric mixing and unpredictable changes in drug release from extended- or controlled-release formulations.

Continue to: Aside from altered...

Aside from altered pharmacokinetics after bariatric surgery, many patients experience an increased risk of self-harm and suicide.20 Therefore, a continued emphasis on and reinforcement of proper antidepressant use and adjustment in these patients is important. This can be facilitated through frequent follow-up visits, either in-person or via telehealth.

Understanding the effect of bariatric surgery on drug absorption is critical to identifying a potential need to adjust a medication dose or formulation after the surgery. Available evidence and data suggest it is reasonable to switch from an extended- or sustained-release formulation to an immediate-release formulation, and to monitor patients more frequently immediately following the surgery.

CASE CONTINUED

Related Resources

- Colvin C, Tsia W, Silverman AL, et al. Nothing up his sleeve: decompensation after bariatric surgery. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(4):15-19. doi:10.12788/cp.010

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax

Amlodipine • Norvasc

Atorvastatin • Lipitor

Dulaglutide • Trulicity

Lisinopril • Zestril, Prinivil

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Metformin • Glucophage

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Ms. B, age 60, presents to the clinic with high blood pressure, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus, depression, and anxiety. Her blood pressure is 138/82 mm Hg and pulse is 70 beats per minute. Her body mass index (BMI) is 41, which indicates she is obese. She has always struggled with her weight and has tried diet and lifestyle modifications, as well as medications, for the past 5 years with no success. Her current medication regimen includes lisinopril 40 mg daily, amlodipine 5 mg daily, atorvastatin 40 mg daily, metformin 500 mg twice daily, dulaglutide 0.75 mg weekly, lithium 600 mg daily, venlafaxine extended-release (XR) 150 mg daily, and alprazolam 0.5 mg as needed up to twice daily. Due to Ms. B’s BMI and because she has ≥1 comorbid health condition, her primary care physician refers her to a gastroenterologist to discuss gastric bypass surgery options.

Ms. B is scheduled for Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. You need to determine if any changes should be made to her psychotropic medications after she undergoes this surgery.

There are multiple types of bariatric surgeries, including Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, laparoscopic adjustable gastric band, and biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD/DS) (Figure1-4). These procedures all restrict the stomach’s capacity to hold food. In most cases, they also bypass areas of absorption in the intestine and cause increased secretion of hormones in the gut, including (but not limited to) peptide-YY (PYY) and glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1). These hormonal changes impact several factors, including satiety, hunger, and blood sugar levels.5

Roux-en-Y is commonly referred to as the gold standard of weight loss surgery. It divides the top of the stomach into a smaller stomach pouch that connects directly to the small intestine to facilitate smaller meals and alters the release of gut hormones. Additionally, a segment of the small intestine that normally absorbs nutrients and medications is completely bypassed. In contrast, the sleeve gastrectomy removes approximately 80% of the stomach, consequently reducing the amount of food that can be consumed. The greatest impact of the sleeve gastrectomy procedure appears to result from changes in gut hormones. The adjustable gastric band procedure works by placing a band around the upper portion of the stomach to create a small pouch above the band to satisfy hunger with a smaller amount of food. Lastly, BPD/DS is a procedure that creates a tubular stomach pouch and bypasses a large portion of the small intestine. Like the gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy, BPD/DS affects gut hormones impacting hunger, satiety, and blood sugar control.

How bariatric surgery can affect drug absorption

As illustrated in the Table,6-19 each type of bariatric surgery may impact drug absorption differently depending on the mechanism by which the stomach is restricted.

Drug malabsorption is a concern for clinicians with patients who have undergone bariatric surgery. There is limited research measuring changes in psychotropic exposure and outcomes following bariatric surgery. A 2009 literature review by Padwal et al7 found that one-third of the 26 studies evaluated provided evidence of decreased absorption following bariatric surgery in patients taking medications that had intrinsic poor absorption, high lipophilicity, and/or undergo enterohepatic recirculation. In a review that included a small study of patients taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or venlafaxine, Godini et al8 demonstrated that although there was a notable decrease in drug absorption closely following the surgery, drug absorption recovered for some patients 1 month after Roux-en-Y surgery. These reviews suggest patients who have undergone any form of bariatric surgery must be observed closely because drug absorption may vary based on the individual, the medication administered, and the amount of time postprocedure.

Until more research becomes available, current evidence supports recommendations to assist patients who have a decreased ability to absorb medications after gastric bypass surgery by switching from an extended-release formulation to an immediate-release or solution formulation. This allows patients to rely less on gastric mixing and unpredictable changes in drug release from extended- or controlled-release formulations.

Continue to: Aside from altered...

Aside from altered pharmacokinetics after bariatric surgery, many patients experience an increased risk of self-harm and suicide.20 Therefore, a continued emphasis on and reinforcement of proper antidepressant use and adjustment in these patients is important. This can be facilitated through frequent follow-up visits, either in-person or via telehealth.

Understanding the effect of bariatric surgery on drug absorption is critical to identifying a potential need to adjust a medication dose or formulation after the surgery. Available evidence and data suggest it is reasonable to switch from an extended- or sustained-release formulation to an immediate-release formulation, and to monitor patients more frequently immediately following the surgery.

CASE CONTINUED

Related Resources

- Colvin C, Tsia W, Silverman AL, et al. Nothing up his sleeve: decompensation after bariatric surgery. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(4):15-19. doi:10.12788/cp.010

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax

Amlodipine • Norvasc

Atorvastatin • Lipitor

Dulaglutide • Trulicity

Lisinopril • Zestril, Prinivil

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Metformin • Glucophage

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Venlafaxine • Effexor

1. Obesity Treatments: Gastric Bypass Surgery. UCLA Health. Accessed April 4, 2021. http://surgery.ucla.edu/bariatrics-gastric-bypass

2. Thomas L. Gastric bypass more likely to require further treatment than gastric sleeve. News Medical. January 15, 2020. Accessed April 4, 2021. https://www.news-medical.net/news/20200115/Gastric-bypass-more-likely-to-require-further-treatment-than-gastric-sleeve.aspx

3. Lap Adjustable Gastric Banding. Laser Stone Surgery & Endoscopy Centre. September 5, 2016. Accessed April 4, 2021. http://www.laserstonesurgery.org/project/lap-adjustable-gastric-banding/

4. BPD/DS Weight-Loss Surgery. Johns Hopkins Medicine. Accessed April 4, 2021. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/treatment-tests-and-therapies/bpdds-weightloss-surgery

5. Holst JJ, Madsbad S, Bojsen-Møller KN, et al. Mechanisms in bariatric surgery: gut hormones, diabetes resolution, and weight loss. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14(5):708-714. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2018.03.003

6. Public Education Committee. Bariatric Surgery Procedures. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. Updated May 2021. Accessed September 4, 2021. https://asmbs.org/patients/bariatric-surgery-procedures

7. Padwal R, Brocks D, Sharma AM. A systematic review of drug absorption following bariatric surgery and its theoretical implications. Obes Rev. 2010;11(1):41-50. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789x.2009.00614.x

8. Godini L, Castellini G, Facchiano E, et al. Mood disorders and bariatric surgery patients: pre- and post- surgery clinical course- an overview. J Obes Weight Loss Medicat. 2016;2(1). doi:10.23937/2572-4010.1510012

9. Smith A, Henriksen B, Cohen A. Pharmacokinetic considerations in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass patients. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2011;68(23):2241-2247. doi:10.2146/ajhp100630

10. Brocks DR, Ben-Eltriki M, Gabr RQ, et al. The effects of gastric bypass surgery on drug absorption and pharmacokinetics. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2012;8(12):1505-1519. doi:10.1517/17425255.2012.722757

11. Hamad GG, Helsel JC, Perel JM, et al. The effect of gastric bypass on the pharmacokinetics of serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(3):256-263. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11050719

12. Angeles PC, Robertsen I, Seeberg LT, et al. The influence of bariatric surgery on oral drug bioavailability in patients with obesity: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2019;20(9):1299-1311. doi:10.1111/obr.12869

13. Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy. University of California San Francisco Department of Surgery. Accessed April 1, 2021. https://surgery.ucsf.edu/conditions--procedures/laparoscopic-sleeve-gastrectomy.aspx

14. Brethauer S, Schauer P. Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy: A Newcomer to Bariatric Surgery. Obesity Action Coalition. 2007. Accessed May 15, 2021. https://www.obesityaction.org/community/article-library/laparoscopic-sleeve-gastrectomy-a-newcomer-to-bariatric-surgery/

15. Roerig JL, Steffen K. Psychopharmacology and bariatric surgery. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2015;23(6):463-469. doi:10.1002/erv.2396

16. Bland CM, Quidley AM, Love BL, et al. Long-term pharmacotherapy considerations in the bariatric surgery patient. A J Health Syst Pharm. 2016;73(16):1230-1242. doi:10.2146/ajhp151062

17. Lin YH, Liu SW, Wu HL, et al. Lithium toxicity with prolonged neurologic sequelae following sleeve gastrectomy: a case report and review of literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(28):e21122. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000021122

18. Lorico S, Colton B. Medication management and pharmacokinetic changes after bariatric surgery. Can Fam Physician. 2020;66(6):409-416.

19. Homan J, Schijns W, Aarts EO, et al. Treatment of vitamin and mineral deficiencies after biliopancreatic diversion with or without duodenal switch: a major challenge. Obes Surg. 2018;28(1):234-241. doi:10.1007/s11695-017-2841-0

20. Neovius M, Bruze G, Jacobson P, et al. Risk of suicide and non-fatal self-harm after bariatric surgery: results from two matched cohort studies. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6(3):197-207. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30437-0

1. Obesity Treatments: Gastric Bypass Surgery. UCLA Health. Accessed April 4, 2021. http://surgery.ucla.edu/bariatrics-gastric-bypass

2. Thomas L. Gastric bypass more likely to require further treatment than gastric sleeve. News Medical. January 15, 2020. Accessed April 4, 2021. https://www.news-medical.net/news/20200115/Gastric-bypass-more-likely-to-require-further-treatment-than-gastric-sleeve.aspx

3. Lap Adjustable Gastric Banding. Laser Stone Surgery & Endoscopy Centre. September 5, 2016. Accessed April 4, 2021. http://www.laserstonesurgery.org/project/lap-adjustable-gastric-banding/

4. BPD/DS Weight-Loss Surgery. Johns Hopkins Medicine. Accessed April 4, 2021. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/treatment-tests-and-therapies/bpdds-weightloss-surgery

5. Holst JJ, Madsbad S, Bojsen-Møller KN, et al. Mechanisms in bariatric surgery: gut hormones, diabetes resolution, and weight loss. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14(5):708-714. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2018.03.003

6. Public Education Committee. Bariatric Surgery Procedures. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. Updated May 2021. Accessed September 4, 2021. https://asmbs.org/patients/bariatric-surgery-procedures

7. Padwal R, Brocks D, Sharma AM. A systematic review of drug absorption following bariatric surgery and its theoretical implications. Obes Rev. 2010;11(1):41-50. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789x.2009.00614.x

8. Godini L, Castellini G, Facchiano E, et al. Mood disorders and bariatric surgery patients: pre- and post- surgery clinical course- an overview. J Obes Weight Loss Medicat. 2016;2(1). doi:10.23937/2572-4010.1510012

9. Smith A, Henriksen B, Cohen A. Pharmacokinetic considerations in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass patients. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2011;68(23):2241-2247. doi:10.2146/ajhp100630

10. Brocks DR, Ben-Eltriki M, Gabr RQ, et al. The effects of gastric bypass surgery on drug absorption and pharmacokinetics. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2012;8(12):1505-1519. doi:10.1517/17425255.2012.722757

11. Hamad GG, Helsel JC, Perel JM, et al. The effect of gastric bypass on the pharmacokinetics of serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(3):256-263. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11050719

12. Angeles PC, Robertsen I, Seeberg LT, et al. The influence of bariatric surgery on oral drug bioavailability in patients with obesity: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2019;20(9):1299-1311. doi:10.1111/obr.12869

13. Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy. University of California San Francisco Department of Surgery. Accessed April 1, 2021. https://surgery.ucsf.edu/conditions--procedures/laparoscopic-sleeve-gastrectomy.aspx

14. Brethauer S, Schauer P. Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy: A Newcomer to Bariatric Surgery. Obesity Action Coalition. 2007. Accessed May 15, 2021. https://www.obesityaction.org/community/article-library/laparoscopic-sleeve-gastrectomy-a-newcomer-to-bariatric-surgery/

15. Roerig JL, Steffen K. Psychopharmacology and bariatric surgery. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2015;23(6):463-469. doi:10.1002/erv.2396

16. Bland CM, Quidley AM, Love BL, et al. Long-term pharmacotherapy considerations in the bariatric surgery patient. A J Health Syst Pharm. 2016;73(16):1230-1242. doi:10.2146/ajhp151062

17. Lin YH, Liu SW, Wu HL, et al. Lithium toxicity with prolonged neurologic sequelae following sleeve gastrectomy: a case report and review of literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(28):e21122. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000021122

18. Lorico S, Colton B. Medication management and pharmacokinetic changes after bariatric surgery. Can Fam Physician. 2020;66(6):409-416.

19. Homan J, Schijns W, Aarts EO, et al. Treatment of vitamin and mineral deficiencies after biliopancreatic diversion with or without duodenal switch: a major challenge. Obes Surg. 2018;28(1):234-241. doi:10.1007/s11695-017-2841-0

20. Neovius M, Bruze G, Jacobson P, et al. Risk of suicide and non-fatal self-harm after bariatric surgery: results from two matched cohort studies. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6(3):197-207. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30437-0