User login

Night or Weekend Admission and Outcomes

The hospitalist movement and increasingly stringent resident work hour restrictions have led to the utilization of shift work in many hospitals.1 Use of nocturnist and night float systems, while often necessary, results in increased patient hand‐offs. Research suggests that hand‐offs in the inpatient setting can adversely affect patient outcomes as lack of continuity may increase the possibility of medical error.2, 3 In 2001, Bell et al.4 found that mortality was higher among patients admitted on weekends as compared to weekdays. Uneven staffing, lack of supervision, and fragmented care were cited as potential contributing factors.4 Similarly, Peberdy et al.5 in 2008 revealed that patients were less likely to survive a cardiac arrest if it occurred at night or on weekends, again attributed in part to fragmented patient care and understaffing.

The results of these studies raise concerns as to whether increased reliance on shift work and resulting handoffs compromises patient care.6, 7 The aim of this study was to evaluate the potential association between night admission and hospitalization‐relevant outcomes (length of stay [LOS], hospital charges, intensive care unit [ICU] transfer during hospitalization, repeat emergency department [ED] visit within 30 days of discharge, readmission within 30 days of discharge, and poor outcome [transfer to the ICU, cardiac arrest, or death] within the first 24 hours of admission) at an institution that exclusively uses nocturnists (night‐shift based hospitalists) and a resident night float system for patients admitted at night to the general medicine service. A secondary aim was to determine the potential association between weekend admission and hospitalization‐relevant outcomes.

Methods

Study Sample and Selection

We conducted a retrospective medical record review at a large urban academic hospital. Using an administrative hospital data set, we assembled a list of approximately 9000 admissions to the general medicine service from the ED between January 2008 and October 2008. We sampled consecutive admissions from 3 distinct periods beginning in January, April, and July to capture outcomes at various points in the academic year. We attempted to review approximately 10% of all charts equally distributed among the 3 sampling periods (ie, 900 charts total with one‐third from each period) based on time available to the reviewers. We excluded patients not admitted to the general medicine service and patients without complete demographic or outcome information. We also excluded patients not admitted from the ED given that the vast majority of admissions to our hospital during the night (96%) or weekend (93%) are from the ED. Patients admitted to the general medicine service are cared for either by a hospitalist or by a teaching team comprised of 1 attending (about 40% of whom are hospitalists), 1 resident, 1 to 2 interns, and 1 to 3 medical students. From 7 am to 6:59 pm patients are admitted to the care of 1 of the primary daytime admitting teams. From 7 pm to 6:59 am patients are admitted by nocturnists (hospitalist service) or night float residents (teaching service). These patients are handed off to day teams at 7 am. Hospitalist teams change service on a weekly to biweekly basis and resident teams switch on a monthly basis; there is no difference in physician staffing between the weekend and weekdays. The Northwestern University Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Data Acquisition and Medical Records Reviews

We obtained demographic data including gender, age, race and ethnicity, patient insurance, admission day (weekday vs. weekend), admission time (defined as the time that a patient receives a hospital bed, which at our institution is also the time that admitting teams receive report and assume care for the patient), and the International Classification of Disease codes required to determine the Major Diagnostic Category (MDC) and calculate the Charlson Comorbidity Index8, 9 as part of an administrative data set. We divided the admission time into night admission (defined as 7 pm to 6:59 am) and day admission (defined as 7:00 am to 6:59 pm). We created a chart abstraction tool to allow manual recording of the additional fields of admitting team (hospitalist vs. resident), 30 day repeat ED visit, 30 day readmission, and poor outcomes within the first 24 hours of admission, directly from the electronic record.

Study Outcomes

We evaluated each admission for the following 6 primary outcomes which were specified a priori: LOS (defined as discharge date and time minus admission date and time), hospital charges (defined as charges billed as recorded in the administrative data set), ICU transfer during hospitalization (defined as 1 ICU day in the administrative data set), 30 day repeat ED visit (defined as a visit to our ED within 30 days of discharge as assessed by chart abstraction), 30 day readmission (defined as any planned or unplanned admission to any inpatient service at our institution within 30 days of discharge as assessed by chart abstraction), and poor outcome within 24 hours of admission (defined as transfer to the ICU, cardiac arrest, or death as assessed by chart abstraction). Each of these outcomes has been used in prior work to assess the quality of inpatient care.10, 11

Statistical Analysis

Interrater reliability between the 3 physician reviewers was assessed for 20 randomly selected admissions across the 4 separate review measures using interclass correlation coefficients. Comparisons between night admissions and day admissions, and between weekend and weekday admissions, for the continuous primary outcomes (LOS, hospital charges) were assessed using 2‐tailed t‐tests as well as Wilcoxon rank sum test. In the multivariable modeling, these outcomes were assessed by linear regression controlling for age, gender, race and ethnicity, Medicaid or self‐pay insurance, admission to the hospitalist or teaching service, most common MDC categories, and Charlson Comorbidity Index. Because both outcomes were right‐skewed, we separately assessed each after log‐transformation controlling for the same variables.

All comparisons of the dichotomous primary outcomes (ICU transfer during hospitalization, 30 day repeat ED visit, 30 day readmission, and poor outcome within the first 24 hours after admission) were assessed at the univariate level by chi‐squared test, and in the multivariable models using logistic regression, controlling for the same variables as the linear models above. All adjustments were specified a priori. All data analyses were conducted using Stata (College Station, TX; Version 11).

Results

We reviewed 857 records. After excluding 33 records lacking administrative data regarding gender, race and ethnicity, and other demographic variables, there were 824 medical records available for analysis. We reviewed a similar number of records from each time period: 274 from January 2008, 265 from April 2008, and 285 from July 2008. A total of 345 (42%) patients were admitted during the day, and 479 (58%) at night; 641 (78%) were admitted on weekdays, and 183 (22%) on weekends. The 33 excluded charts were similar to the included charts for both time of admission and outcomes. Results for parametric testing and nonparametric testing, as well as for log‐transformation and non‐log‐transformation of the continuous outcomes were similar in both magnitude and statistical significance, so we present the parametric and nonlog‐transformed results below for ease of interpretation.

Interrater reliability among the 3 reviewers was very high. There were no disagreements among the 20 multiple reviews for either poor outcomes within 24 hours of admission or admitting service; the interclass correlation coefficients for 30 day repeat ED visit and 30 day readmission were 0.97 and 0.87, respectively.

Patients admitted at night or on the weekend were similar to patients admitted during the day and week across age, gender, insurance class, MDC, and Charlson Comorbidity Index (Table 1). For unadjusted outcomes, patients admitted at night has a similar LOS, hospital charges, 30 day repeat ED visits, 30 day readmissions, and poor outcome within 24 hours of admission as those patients admitted during the day. They had a potentially lower chance of any ICU transfer during hospitalization though this did not reach statistical significance at P < 0.05 (night admission 6%, day admission 3%, P = 0.06) (Table 2).

| Characteristics | Time of Day | Day of the Week | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day Admission (n = 345) | Night Admission (n = 479) | Weekday Admission (n = 641) | Weekend Admission (n = 183) | |

| ||||

| Age (years) | 60.8 | 59.7 | 60.6 | 58.7 |

| Gender (% male) | 47 | 43 | 45 | 46 |

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | ||||

| White, Asian, other | 61 | 54 | 57 | 55 |

| Black | 34 | 38 | 37 | 34 |

| Hispanic | 5 | 8 | 6 | 10 |

| Medicaid or self pay (%) | 9 | 10 | 10 | 11 |

| Major diagnostic category (%) | ||||

| Respiratory disease | 14 | 13 | 14 | 13 |

| Circulatory disease | 28 | 23 | 26 | 24 |

| Digestive disease | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| Other | 45 | 52 | 48 | 51 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 3.71 | 3.60 | 3.66 | 3.60 |

| Outcomes | Time of Day | Day of the Week | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day Admission (n = 345) | Night Admission (n = 479) | Weekday Admission (n = 641) | Weekend Admission (n = 183) | |

| ||||

| Length of stay | 4.3 | 4.1 | 4.3 | 3.8 |

| Hospital charges | $27,500 | $25,200 | $27,200* | $22,700* |

| ICU transfer during hospitalization (%) | 6 | 3 | 5* | 1* |

| Repeat ED visit at 30 days (%) | 20 | 22 | 22 | 21 |

| Readmission at 30 days (%) | 17 | 20 | 20 | 17 |

| Poor outcome at 24 hours (ICU transfer, cardiac arrest, or death)(%) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

Patients admitted to the hospital during the weekend were similar to patients admitted during the week for unadjusted LOS, 30 day repeat ED visit or readmission rate, and poor outcomes within 24 hours of admission as those admitted during the week; however, they had lower hospital charges (weekend admission $22,700, weekday admission $27,200; P = 0.02), and a lower chance of ICU transfer during hospitalization (weekend admission 1%, weekday admission 5%; P = 0.02) (Table 2).

In the multivariable linear and logistic regression models (Tables 3 and 4), we assessed the independent association between night admission or weekend admission and each hospitalization‐relevant outcome except for poor outcome within 24 hours of admission (poor outcome within 24 hours of admission was not modeled to avoid the risk of overfitting because there were only 13 total events). After adjustment for age, gender, race and ethnicity, admitting service (hospitalist or teaching), Medicaid or self‐pay insurance, MDC, and Charlson Comorbidity Index, there was no statistically significant association between night admission and worse outcomes for LOS, hospital charges, 30 day repeat ED visit, or 30 day readmission. Night admission was associated with a decreased chance of ICU transfer during hospitalization, but the difference was not statistically significant (odds ratio, 0.54; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.26‐1.11, P = 0.09). Weekend admission was not associated with worse outcomes for LOS or 30 day repeat ED visit or readmission; however, weekend admission was associated with a decrease in overall charges ($4400; 95% CI, $8300 to $600) and a decreased chance of ICU transfer during hospitalization (odds ratio, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.050.88).

| Predictors | Length of Stay (days), Coefficient (95% CI) | Hospital Charges (dollars), Coefficient (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Night admission | 0.23 (0.77 to 0.32) | 2100 (5400 to 1100) |

| Weekend admission | 0.42 (1.07 to 0.23) | 4400 (8300 to 600)* |

| Age | 0.01 (0.01 to 0.03) | 0 (100 to 100) |

| Male gender | 0.15 (0.70 to 0.39) | 400 (3700 to 2800) |

| Race, Black | 0.18 (0.41 to 0.78) | 200 (3700 to 3400) |

| Ethnicity, Hispanic | 0.62 (1.73 to 0.49) | 2300 (8900 to 4300) |

| Medicaid or self‐pay insurance | 1.87 (0.93 to 2.82)* | 8900 (3300 to 14600)* |

| Hospitalist service | 0.26 (0.29 to 0.81) | 600 (3900 to 2700) |

| MDC: respiratory | 0.36 (1.18 to 0.46) | 700 (4200 to 5600) |

| MDC: circulatory | 1.36 (2.04 to 0.68)* | 600 (4600 to 3400) |

| MDC: digestive | 1.22 (2.08 to 0.35)* | 6800 (12000 to 1700)* |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 0.35 (0.22 to 0.49)* | 2200 (1400 to 3000)* |

| Predictors | ICU Transfer during Hospitalization, Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Repeat ED Visit at 30 days, Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Readmission at 30 days, Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Night admission | 0.53 (0.26 to 1.11) | 1.13 (0.80 to 1.60) | 1.23 (0.86 to 1.78) |

| Weekend admission | 0.20 (0.05 to 0.88)* | 0.95 (0.63 to 1.44) | 0.80 (0.51 to 1.25) |

| Age | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.02) | 0.99 (0.98 to 1.002) | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.01) |

| Male gender | 0.98 (0.47 to 2.02) | 1.09 (0.78 to 1.54) | 0.91 (0.64 to 1.31) |

| Race, Black | 0.75 (0.33 to 1.70) | 1.48 (1.02 to 2.14)* | 1.12 (0.76 to 1.65) |

| Ethnicity, Hispanic | 0.76 (0.16 to 3.73) | 1.09 (0.55 to 2.17) | 1.11 (0.55 to 2.22) |

| Medicaid or self‐pay insurance | 0.75 (0.16 to 3.49) | 1.61 (0.95 to 2.72) | 2.14 (1.24 to 3.67)* |

| Hospitalist service | 0.68 (0.33 to 1.44) | 1.15 (0.81 to 1.63) | 0.99 (0.69 to 1.43) |

| MDC: respiratory | 1.18 (0.41 to 3.38) | 1.02 (0.61 to 1.69) | 1.16 (0.69 to 1.95) |

| MDC: circulatory | 1.22 (0.52 to 2.87) | 0.79 (0.51 to 1.22) | 0.80 (0.51 to 1.27) |

| MDC: digestive | 0.51 (0.11 to 2.32) | 0.83 (0.47 to 1.46) | 1.08 (0.62 to 1.91) |

| Charlson Comobrbidity Index | 1.25 (1.09 to 1.45)* | 1.09 (1.01 to 1.19)* | 1.11 (1.02 to 1.21)* |

Our multivariate models explained very little of the variance in patient outcomes. For LOS and hospital charges, adjusted R2 values were 0.06 and 0.05, respectively. For ICU transfer during hospitalization, 30 day repeat ED visit, and 30 day readmission, the areas under the receiver operator curves were 0.75, 0.51, and 0.61 respectively.

To assess the robustness of our conclusions regarding night admission, we redefined night to include only patients admitted between the hours of 8 pm and 5:59 am. This did not change our conclusions. We also tested for interaction between night admission and weekend admission for all outcomes to assess whether night admissions on the weekend were in fact at increased risk of worse outcomes; we found no evidence of interaction (P > 0.3 for the interaction terms in each model).

Discussion

Among patients admitted to the medicine services at our academic medical center, night or weekend admission was not associated with worse hospitalization‐relevant outcomes. In some cases, night or weekend admission was associated with better outcomes, particularly in terms of ICU transfer during hospitalization and hospital charges. Prior research indicates worse outcomes during off‐hours,5 but we did not replicate this finding in our study.

The finding that admission at night was not associated with worse outcomes, particularly proximal outcomes such as LOS or ICU transfer during hospitalization, was surprising, though reassuring in view of the fact that more than half of our patients are admitted at night. We believe a few factors may be responsible. First, our general medicine service is staffed during the night (7 pm to 7 am) by in‐house nocturnists and night float residents. Second, our staffing ratio, while lower at night than during the day, remains the same on weekends and may be higher than in other settings. In continuously well‐staffed settings such as the ED12 and ICU,13 night and weekend admissions are only inconsistently associated with worse outcomes, which may be the same phenomena we observed in the current study. Third, the hospital used as the site of this study has received Nursing Magnet recognition and numerous quality awards such as the National Research Corporation's Consumer Choice Award and recognition as a Distinguished Hospital for Clinical Excellence by HealthGrades. Fourth, our integrated electronic medical record, computerized physician order entry system, and automatically generated sign out serve as complements to the morning hand off. Fifth, hospitalists and teaching teams rotate on a weekly, biweekly, or every 4 week basis, which may protect against discontinuity associated with the weekend. We believe that all of these factors may facilitate alert, comprehensive care during the night and weekend as well as safe and efficient transfer of patients from the night to the day providers.

We were also surprised by the association between weekend admission and lower charges and a lower chance of ICU transfer during hospitalization. We believe many of the same factors noted above may have played a role in these findings. In terms of hospital charges, it is possible that some workups were completed outside of the hospital rather than during the hospitalization, and that some tests were not ordered at all due to unavailability on weekends. The decreased chance of ICU transfer is unexplained. We hypothesize that there may have been a more conservative admission strategy within the ED, such that patients with high baseline severity were admitted directly to the ICU on the weekend rather than being admitted first to the general medicine floor. This hypothesis requires further study.

Our study had important limitations. It was a retrospective study from a single academic hospital. The sample size lacked sufficient power to detect differences in the low frequency of certain outcomes such as poor outcomes within 24 hours of admission (2% vs. 1%), and also for more frequent outcomes such as 30 day readmission; it is possible that with a larger sample there would have been statistically significant differences. Further, we recognize that the Charlson Comorbidity Index, which was developed to predict 1‐year mortality for medicine service patients, does not adjust for severity of illness at presentation, particularly for outcomes such as readmission. If patients admitted at night and during the weekend were less acutely ill despite having similar comorbidities and MDCs at admission, true associations between time of admission and worse outcomes could have been masked. Furthermore, the multivariable modeling explained very little of the variance in patient outcomes such that significant unmeasured confounding may still be present, and consequently our results cannot be interpreted in a causal way. Data was collected from electronic records, so it is possible that some adverse events were not recorded. However, it seems unlikely that major events such as death and transfer to an ICU would have been missed.

Several aspects of the study strengthen our confidence in the findings, including a large sample size, relevance of the outcomes, the adjustment for confounders, and an assessment for robustness of the conclusions based on restricting the definition of night and also testing for interaction between night and weekend admission. Our patient demographics and insurance mix resemble that of other academic hospitals,10 and perhaps our results may be generalizable to these settings, if not to non‐urban or community hospitals. Furthermore, the Charlson Comorbidity Index was associated with all 5 of the modeled outcomes we chose for our study, reaffirming their utility in assessing the quality of hospital care. Future directions for investigation may include examining the association of night admission with hospitalization‐relevant outcomes in nonacademic, nonurban settings, and examining whether the lack of association between night and weekend admission and worse outcomes persists with adjustment for initial severity of illness.

In summary, at a large, well‐staffed urban academic hospital, day or time of admission were not associated with worse hospitalization‐relevant outcomes. The use of nocturnists and night float teams for night admissions and continuity across weekends appears to be a safe approach to handling the increased volume of patients admitted at night, and a viable alternative to overnight call in the era of work hour restrictions.

- ,,, et al.Three‐year results of mandated work hour restrictions: attending and resident perspectives and effects in a community hospital.Am Surg.2008;74(6):542–546; discussion 546–547.

- ,,, et al.Handoffs causing patient harm: a survey of medical and surgical house staff.Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf.2008;34(10):563–570.

- ,,,,.Does housestaff discontinuity of care increase the risk for preventable adverse events?Ann Intern Med.1994;121(11):866–872.

- ,.Mortality among patients admitted to hospitals on weekends as compared with weekdays.N Engl J Med.2001;345(9):663–668.

- ,,, et al.Survival from in‐hospital cardiac arrest during nights and weekends.JAMA.2008;299(7):785–792.

- ,,,.Continuity of care and intensive care unit use at the end of life.Arch Intern Med.2009;169(1):81–86.

- ,,,,,.Continuity of outpatient and inpatient care by primary care physicians for hospitalized older adults.JAMA.2009;301(16):1671–1680.

- ,,,.Why predictive indexes perform less well in validation studies: is it magic or methods?Arch Intern Med.1987;147:2155–2161.

- ,,.Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD‐9‐CM administrative databases.J Clin Epidemiol.1992;45(6):613–619.

- ,,, et al.Implementation of a physician assistant/hospitalist service in an academic medical center: impact on efficiency and patient outcomes.J Hosp Med.2008;3(5):361–368.

- ,,, et al.Use of an admission early warning score to predict patient morbidity and mortality and treatment success.Emerg Med J.2008;25(12):803–806.

- ,,.The impact of weekends on outcome for emergency patients.Clin Med.2005;5(6):621–625.

- ,,,,,.Off hour admission to an intensivist‐led ICU is not associated with increased mortality.Crit Care.2009;13(3):R84.

The hospitalist movement and increasingly stringent resident work hour restrictions have led to the utilization of shift work in many hospitals.1 Use of nocturnist and night float systems, while often necessary, results in increased patient hand‐offs. Research suggests that hand‐offs in the inpatient setting can adversely affect patient outcomes as lack of continuity may increase the possibility of medical error.2, 3 In 2001, Bell et al.4 found that mortality was higher among patients admitted on weekends as compared to weekdays. Uneven staffing, lack of supervision, and fragmented care were cited as potential contributing factors.4 Similarly, Peberdy et al.5 in 2008 revealed that patients were less likely to survive a cardiac arrest if it occurred at night or on weekends, again attributed in part to fragmented patient care and understaffing.

The results of these studies raise concerns as to whether increased reliance on shift work and resulting handoffs compromises patient care.6, 7 The aim of this study was to evaluate the potential association between night admission and hospitalization‐relevant outcomes (length of stay [LOS], hospital charges, intensive care unit [ICU] transfer during hospitalization, repeat emergency department [ED] visit within 30 days of discharge, readmission within 30 days of discharge, and poor outcome [transfer to the ICU, cardiac arrest, or death] within the first 24 hours of admission) at an institution that exclusively uses nocturnists (night‐shift based hospitalists) and a resident night float system for patients admitted at night to the general medicine service. A secondary aim was to determine the potential association between weekend admission and hospitalization‐relevant outcomes.

Methods

Study Sample and Selection

We conducted a retrospective medical record review at a large urban academic hospital. Using an administrative hospital data set, we assembled a list of approximately 9000 admissions to the general medicine service from the ED between January 2008 and October 2008. We sampled consecutive admissions from 3 distinct periods beginning in January, April, and July to capture outcomes at various points in the academic year. We attempted to review approximately 10% of all charts equally distributed among the 3 sampling periods (ie, 900 charts total with one‐third from each period) based on time available to the reviewers. We excluded patients not admitted to the general medicine service and patients without complete demographic or outcome information. We also excluded patients not admitted from the ED given that the vast majority of admissions to our hospital during the night (96%) or weekend (93%) are from the ED. Patients admitted to the general medicine service are cared for either by a hospitalist or by a teaching team comprised of 1 attending (about 40% of whom are hospitalists), 1 resident, 1 to 2 interns, and 1 to 3 medical students. From 7 am to 6:59 pm patients are admitted to the care of 1 of the primary daytime admitting teams. From 7 pm to 6:59 am patients are admitted by nocturnists (hospitalist service) or night float residents (teaching service). These patients are handed off to day teams at 7 am. Hospitalist teams change service on a weekly to biweekly basis and resident teams switch on a monthly basis; there is no difference in physician staffing between the weekend and weekdays. The Northwestern University Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Data Acquisition and Medical Records Reviews

We obtained demographic data including gender, age, race and ethnicity, patient insurance, admission day (weekday vs. weekend), admission time (defined as the time that a patient receives a hospital bed, which at our institution is also the time that admitting teams receive report and assume care for the patient), and the International Classification of Disease codes required to determine the Major Diagnostic Category (MDC) and calculate the Charlson Comorbidity Index8, 9 as part of an administrative data set. We divided the admission time into night admission (defined as 7 pm to 6:59 am) and day admission (defined as 7:00 am to 6:59 pm). We created a chart abstraction tool to allow manual recording of the additional fields of admitting team (hospitalist vs. resident), 30 day repeat ED visit, 30 day readmission, and poor outcomes within the first 24 hours of admission, directly from the electronic record.

Study Outcomes

We evaluated each admission for the following 6 primary outcomes which were specified a priori: LOS (defined as discharge date and time minus admission date and time), hospital charges (defined as charges billed as recorded in the administrative data set), ICU transfer during hospitalization (defined as 1 ICU day in the administrative data set), 30 day repeat ED visit (defined as a visit to our ED within 30 days of discharge as assessed by chart abstraction), 30 day readmission (defined as any planned or unplanned admission to any inpatient service at our institution within 30 days of discharge as assessed by chart abstraction), and poor outcome within 24 hours of admission (defined as transfer to the ICU, cardiac arrest, or death as assessed by chart abstraction). Each of these outcomes has been used in prior work to assess the quality of inpatient care.10, 11

Statistical Analysis

Interrater reliability between the 3 physician reviewers was assessed for 20 randomly selected admissions across the 4 separate review measures using interclass correlation coefficients. Comparisons between night admissions and day admissions, and between weekend and weekday admissions, for the continuous primary outcomes (LOS, hospital charges) were assessed using 2‐tailed t‐tests as well as Wilcoxon rank sum test. In the multivariable modeling, these outcomes were assessed by linear regression controlling for age, gender, race and ethnicity, Medicaid or self‐pay insurance, admission to the hospitalist or teaching service, most common MDC categories, and Charlson Comorbidity Index. Because both outcomes were right‐skewed, we separately assessed each after log‐transformation controlling for the same variables.

All comparisons of the dichotomous primary outcomes (ICU transfer during hospitalization, 30 day repeat ED visit, 30 day readmission, and poor outcome within the first 24 hours after admission) were assessed at the univariate level by chi‐squared test, and in the multivariable models using logistic regression, controlling for the same variables as the linear models above. All adjustments were specified a priori. All data analyses were conducted using Stata (College Station, TX; Version 11).

Results

We reviewed 857 records. After excluding 33 records lacking administrative data regarding gender, race and ethnicity, and other demographic variables, there were 824 medical records available for analysis. We reviewed a similar number of records from each time period: 274 from January 2008, 265 from April 2008, and 285 from July 2008. A total of 345 (42%) patients were admitted during the day, and 479 (58%) at night; 641 (78%) were admitted on weekdays, and 183 (22%) on weekends. The 33 excluded charts were similar to the included charts for both time of admission and outcomes. Results for parametric testing and nonparametric testing, as well as for log‐transformation and non‐log‐transformation of the continuous outcomes were similar in both magnitude and statistical significance, so we present the parametric and nonlog‐transformed results below for ease of interpretation.

Interrater reliability among the 3 reviewers was very high. There were no disagreements among the 20 multiple reviews for either poor outcomes within 24 hours of admission or admitting service; the interclass correlation coefficients for 30 day repeat ED visit and 30 day readmission were 0.97 and 0.87, respectively.

Patients admitted at night or on the weekend were similar to patients admitted during the day and week across age, gender, insurance class, MDC, and Charlson Comorbidity Index (Table 1). For unadjusted outcomes, patients admitted at night has a similar LOS, hospital charges, 30 day repeat ED visits, 30 day readmissions, and poor outcome within 24 hours of admission as those patients admitted during the day. They had a potentially lower chance of any ICU transfer during hospitalization though this did not reach statistical significance at P < 0.05 (night admission 6%, day admission 3%, P = 0.06) (Table 2).

| Characteristics | Time of Day | Day of the Week | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day Admission (n = 345) | Night Admission (n = 479) | Weekday Admission (n = 641) | Weekend Admission (n = 183) | |

| ||||

| Age (years) | 60.8 | 59.7 | 60.6 | 58.7 |

| Gender (% male) | 47 | 43 | 45 | 46 |

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | ||||

| White, Asian, other | 61 | 54 | 57 | 55 |

| Black | 34 | 38 | 37 | 34 |

| Hispanic | 5 | 8 | 6 | 10 |

| Medicaid or self pay (%) | 9 | 10 | 10 | 11 |

| Major diagnostic category (%) | ||||

| Respiratory disease | 14 | 13 | 14 | 13 |

| Circulatory disease | 28 | 23 | 26 | 24 |

| Digestive disease | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| Other | 45 | 52 | 48 | 51 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 3.71 | 3.60 | 3.66 | 3.60 |

| Outcomes | Time of Day | Day of the Week | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day Admission (n = 345) | Night Admission (n = 479) | Weekday Admission (n = 641) | Weekend Admission (n = 183) | |

| ||||

| Length of stay | 4.3 | 4.1 | 4.3 | 3.8 |

| Hospital charges | $27,500 | $25,200 | $27,200* | $22,700* |

| ICU transfer during hospitalization (%) | 6 | 3 | 5* | 1* |

| Repeat ED visit at 30 days (%) | 20 | 22 | 22 | 21 |

| Readmission at 30 days (%) | 17 | 20 | 20 | 17 |

| Poor outcome at 24 hours (ICU transfer, cardiac arrest, or death)(%) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

Patients admitted to the hospital during the weekend were similar to patients admitted during the week for unadjusted LOS, 30 day repeat ED visit or readmission rate, and poor outcomes within 24 hours of admission as those admitted during the week; however, they had lower hospital charges (weekend admission $22,700, weekday admission $27,200; P = 0.02), and a lower chance of ICU transfer during hospitalization (weekend admission 1%, weekday admission 5%; P = 0.02) (Table 2).

In the multivariable linear and logistic regression models (Tables 3 and 4), we assessed the independent association between night admission or weekend admission and each hospitalization‐relevant outcome except for poor outcome within 24 hours of admission (poor outcome within 24 hours of admission was not modeled to avoid the risk of overfitting because there were only 13 total events). After adjustment for age, gender, race and ethnicity, admitting service (hospitalist or teaching), Medicaid or self‐pay insurance, MDC, and Charlson Comorbidity Index, there was no statistically significant association between night admission and worse outcomes for LOS, hospital charges, 30 day repeat ED visit, or 30 day readmission. Night admission was associated with a decreased chance of ICU transfer during hospitalization, but the difference was not statistically significant (odds ratio, 0.54; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.26‐1.11, P = 0.09). Weekend admission was not associated with worse outcomes for LOS or 30 day repeat ED visit or readmission; however, weekend admission was associated with a decrease in overall charges ($4400; 95% CI, $8300 to $600) and a decreased chance of ICU transfer during hospitalization (odds ratio, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.050.88).

| Predictors | Length of Stay (days), Coefficient (95% CI) | Hospital Charges (dollars), Coefficient (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Night admission | 0.23 (0.77 to 0.32) | 2100 (5400 to 1100) |

| Weekend admission | 0.42 (1.07 to 0.23) | 4400 (8300 to 600)* |

| Age | 0.01 (0.01 to 0.03) | 0 (100 to 100) |

| Male gender | 0.15 (0.70 to 0.39) | 400 (3700 to 2800) |

| Race, Black | 0.18 (0.41 to 0.78) | 200 (3700 to 3400) |

| Ethnicity, Hispanic | 0.62 (1.73 to 0.49) | 2300 (8900 to 4300) |

| Medicaid or self‐pay insurance | 1.87 (0.93 to 2.82)* | 8900 (3300 to 14600)* |

| Hospitalist service | 0.26 (0.29 to 0.81) | 600 (3900 to 2700) |

| MDC: respiratory | 0.36 (1.18 to 0.46) | 700 (4200 to 5600) |

| MDC: circulatory | 1.36 (2.04 to 0.68)* | 600 (4600 to 3400) |

| MDC: digestive | 1.22 (2.08 to 0.35)* | 6800 (12000 to 1700)* |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 0.35 (0.22 to 0.49)* | 2200 (1400 to 3000)* |

| Predictors | ICU Transfer during Hospitalization, Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Repeat ED Visit at 30 days, Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Readmission at 30 days, Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Night admission | 0.53 (0.26 to 1.11) | 1.13 (0.80 to 1.60) | 1.23 (0.86 to 1.78) |

| Weekend admission | 0.20 (0.05 to 0.88)* | 0.95 (0.63 to 1.44) | 0.80 (0.51 to 1.25) |

| Age | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.02) | 0.99 (0.98 to 1.002) | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.01) |

| Male gender | 0.98 (0.47 to 2.02) | 1.09 (0.78 to 1.54) | 0.91 (0.64 to 1.31) |

| Race, Black | 0.75 (0.33 to 1.70) | 1.48 (1.02 to 2.14)* | 1.12 (0.76 to 1.65) |

| Ethnicity, Hispanic | 0.76 (0.16 to 3.73) | 1.09 (0.55 to 2.17) | 1.11 (0.55 to 2.22) |

| Medicaid or self‐pay insurance | 0.75 (0.16 to 3.49) | 1.61 (0.95 to 2.72) | 2.14 (1.24 to 3.67)* |

| Hospitalist service | 0.68 (0.33 to 1.44) | 1.15 (0.81 to 1.63) | 0.99 (0.69 to 1.43) |

| MDC: respiratory | 1.18 (0.41 to 3.38) | 1.02 (0.61 to 1.69) | 1.16 (0.69 to 1.95) |

| MDC: circulatory | 1.22 (0.52 to 2.87) | 0.79 (0.51 to 1.22) | 0.80 (0.51 to 1.27) |

| MDC: digestive | 0.51 (0.11 to 2.32) | 0.83 (0.47 to 1.46) | 1.08 (0.62 to 1.91) |

| Charlson Comobrbidity Index | 1.25 (1.09 to 1.45)* | 1.09 (1.01 to 1.19)* | 1.11 (1.02 to 1.21)* |

Our multivariate models explained very little of the variance in patient outcomes. For LOS and hospital charges, adjusted R2 values were 0.06 and 0.05, respectively. For ICU transfer during hospitalization, 30 day repeat ED visit, and 30 day readmission, the areas under the receiver operator curves were 0.75, 0.51, and 0.61 respectively.

To assess the robustness of our conclusions regarding night admission, we redefined night to include only patients admitted between the hours of 8 pm and 5:59 am. This did not change our conclusions. We also tested for interaction between night admission and weekend admission for all outcomes to assess whether night admissions on the weekend were in fact at increased risk of worse outcomes; we found no evidence of interaction (P > 0.3 for the interaction terms in each model).

Discussion

Among patients admitted to the medicine services at our academic medical center, night or weekend admission was not associated with worse hospitalization‐relevant outcomes. In some cases, night or weekend admission was associated with better outcomes, particularly in terms of ICU transfer during hospitalization and hospital charges. Prior research indicates worse outcomes during off‐hours,5 but we did not replicate this finding in our study.

The finding that admission at night was not associated with worse outcomes, particularly proximal outcomes such as LOS or ICU transfer during hospitalization, was surprising, though reassuring in view of the fact that more than half of our patients are admitted at night. We believe a few factors may be responsible. First, our general medicine service is staffed during the night (7 pm to 7 am) by in‐house nocturnists and night float residents. Second, our staffing ratio, while lower at night than during the day, remains the same on weekends and may be higher than in other settings. In continuously well‐staffed settings such as the ED12 and ICU,13 night and weekend admissions are only inconsistently associated with worse outcomes, which may be the same phenomena we observed in the current study. Third, the hospital used as the site of this study has received Nursing Magnet recognition and numerous quality awards such as the National Research Corporation's Consumer Choice Award and recognition as a Distinguished Hospital for Clinical Excellence by HealthGrades. Fourth, our integrated electronic medical record, computerized physician order entry system, and automatically generated sign out serve as complements to the morning hand off. Fifth, hospitalists and teaching teams rotate on a weekly, biweekly, or every 4 week basis, which may protect against discontinuity associated with the weekend. We believe that all of these factors may facilitate alert, comprehensive care during the night and weekend as well as safe and efficient transfer of patients from the night to the day providers.

We were also surprised by the association between weekend admission and lower charges and a lower chance of ICU transfer during hospitalization. We believe many of the same factors noted above may have played a role in these findings. In terms of hospital charges, it is possible that some workups were completed outside of the hospital rather than during the hospitalization, and that some tests were not ordered at all due to unavailability on weekends. The decreased chance of ICU transfer is unexplained. We hypothesize that there may have been a more conservative admission strategy within the ED, such that patients with high baseline severity were admitted directly to the ICU on the weekend rather than being admitted first to the general medicine floor. This hypothesis requires further study.

Our study had important limitations. It was a retrospective study from a single academic hospital. The sample size lacked sufficient power to detect differences in the low frequency of certain outcomes such as poor outcomes within 24 hours of admission (2% vs. 1%), and also for more frequent outcomes such as 30 day readmission; it is possible that with a larger sample there would have been statistically significant differences. Further, we recognize that the Charlson Comorbidity Index, which was developed to predict 1‐year mortality for medicine service patients, does not adjust for severity of illness at presentation, particularly for outcomes such as readmission. If patients admitted at night and during the weekend were less acutely ill despite having similar comorbidities and MDCs at admission, true associations between time of admission and worse outcomes could have been masked. Furthermore, the multivariable modeling explained very little of the variance in patient outcomes such that significant unmeasured confounding may still be present, and consequently our results cannot be interpreted in a causal way. Data was collected from electronic records, so it is possible that some adverse events were not recorded. However, it seems unlikely that major events such as death and transfer to an ICU would have been missed.

Several aspects of the study strengthen our confidence in the findings, including a large sample size, relevance of the outcomes, the adjustment for confounders, and an assessment for robustness of the conclusions based on restricting the definition of night and also testing for interaction between night and weekend admission. Our patient demographics and insurance mix resemble that of other academic hospitals,10 and perhaps our results may be generalizable to these settings, if not to non‐urban or community hospitals. Furthermore, the Charlson Comorbidity Index was associated with all 5 of the modeled outcomes we chose for our study, reaffirming their utility in assessing the quality of hospital care. Future directions for investigation may include examining the association of night admission with hospitalization‐relevant outcomes in nonacademic, nonurban settings, and examining whether the lack of association between night and weekend admission and worse outcomes persists with adjustment for initial severity of illness.

In summary, at a large, well‐staffed urban academic hospital, day or time of admission were not associated with worse hospitalization‐relevant outcomes. The use of nocturnists and night float teams for night admissions and continuity across weekends appears to be a safe approach to handling the increased volume of patients admitted at night, and a viable alternative to overnight call in the era of work hour restrictions.

The hospitalist movement and increasingly stringent resident work hour restrictions have led to the utilization of shift work in many hospitals.1 Use of nocturnist and night float systems, while often necessary, results in increased patient hand‐offs. Research suggests that hand‐offs in the inpatient setting can adversely affect patient outcomes as lack of continuity may increase the possibility of medical error.2, 3 In 2001, Bell et al.4 found that mortality was higher among patients admitted on weekends as compared to weekdays. Uneven staffing, lack of supervision, and fragmented care were cited as potential contributing factors.4 Similarly, Peberdy et al.5 in 2008 revealed that patients were less likely to survive a cardiac arrest if it occurred at night or on weekends, again attributed in part to fragmented patient care and understaffing.

The results of these studies raise concerns as to whether increased reliance on shift work and resulting handoffs compromises patient care.6, 7 The aim of this study was to evaluate the potential association between night admission and hospitalization‐relevant outcomes (length of stay [LOS], hospital charges, intensive care unit [ICU] transfer during hospitalization, repeat emergency department [ED] visit within 30 days of discharge, readmission within 30 days of discharge, and poor outcome [transfer to the ICU, cardiac arrest, or death] within the first 24 hours of admission) at an institution that exclusively uses nocturnists (night‐shift based hospitalists) and a resident night float system for patients admitted at night to the general medicine service. A secondary aim was to determine the potential association between weekend admission and hospitalization‐relevant outcomes.

Methods

Study Sample and Selection

We conducted a retrospective medical record review at a large urban academic hospital. Using an administrative hospital data set, we assembled a list of approximately 9000 admissions to the general medicine service from the ED between January 2008 and October 2008. We sampled consecutive admissions from 3 distinct periods beginning in January, April, and July to capture outcomes at various points in the academic year. We attempted to review approximately 10% of all charts equally distributed among the 3 sampling periods (ie, 900 charts total with one‐third from each period) based on time available to the reviewers. We excluded patients not admitted to the general medicine service and patients without complete demographic or outcome information. We also excluded patients not admitted from the ED given that the vast majority of admissions to our hospital during the night (96%) or weekend (93%) are from the ED. Patients admitted to the general medicine service are cared for either by a hospitalist or by a teaching team comprised of 1 attending (about 40% of whom are hospitalists), 1 resident, 1 to 2 interns, and 1 to 3 medical students. From 7 am to 6:59 pm patients are admitted to the care of 1 of the primary daytime admitting teams. From 7 pm to 6:59 am patients are admitted by nocturnists (hospitalist service) or night float residents (teaching service). These patients are handed off to day teams at 7 am. Hospitalist teams change service on a weekly to biweekly basis and resident teams switch on a monthly basis; there is no difference in physician staffing between the weekend and weekdays. The Northwestern University Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Data Acquisition and Medical Records Reviews

We obtained demographic data including gender, age, race and ethnicity, patient insurance, admission day (weekday vs. weekend), admission time (defined as the time that a patient receives a hospital bed, which at our institution is also the time that admitting teams receive report and assume care for the patient), and the International Classification of Disease codes required to determine the Major Diagnostic Category (MDC) and calculate the Charlson Comorbidity Index8, 9 as part of an administrative data set. We divided the admission time into night admission (defined as 7 pm to 6:59 am) and day admission (defined as 7:00 am to 6:59 pm). We created a chart abstraction tool to allow manual recording of the additional fields of admitting team (hospitalist vs. resident), 30 day repeat ED visit, 30 day readmission, and poor outcomes within the first 24 hours of admission, directly from the electronic record.

Study Outcomes

We evaluated each admission for the following 6 primary outcomes which were specified a priori: LOS (defined as discharge date and time minus admission date and time), hospital charges (defined as charges billed as recorded in the administrative data set), ICU transfer during hospitalization (defined as 1 ICU day in the administrative data set), 30 day repeat ED visit (defined as a visit to our ED within 30 days of discharge as assessed by chart abstraction), 30 day readmission (defined as any planned or unplanned admission to any inpatient service at our institution within 30 days of discharge as assessed by chart abstraction), and poor outcome within 24 hours of admission (defined as transfer to the ICU, cardiac arrest, or death as assessed by chart abstraction). Each of these outcomes has been used in prior work to assess the quality of inpatient care.10, 11

Statistical Analysis

Interrater reliability between the 3 physician reviewers was assessed for 20 randomly selected admissions across the 4 separate review measures using interclass correlation coefficients. Comparisons between night admissions and day admissions, and between weekend and weekday admissions, for the continuous primary outcomes (LOS, hospital charges) were assessed using 2‐tailed t‐tests as well as Wilcoxon rank sum test. In the multivariable modeling, these outcomes were assessed by linear regression controlling for age, gender, race and ethnicity, Medicaid or self‐pay insurance, admission to the hospitalist or teaching service, most common MDC categories, and Charlson Comorbidity Index. Because both outcomes were right‐skewed, we separately assessed each after log‐transformation controlling for the same variables.

All comparisons of the dichotomous primary outcomes (ICU transfer during hospitalization, 30 day repeat ED visit, 30 day readmission, and poor outcome within the first 24 hours after admission) were assessed at the univariate level by chi‐squared test, and in the multivariable models using logistic regression, controlling for the same variables as the linear models above. All adjustments were specified a priori. All data analyses were conducted using Stata (College Station, TX; Version 11).

Results

We reviewed 857 records. After excluding 33 records lacking administrative data regarding gender, race and ethnicity, and other demographic variables, there were 824 medical records available for analysis. We reviewed a similar number of records from each time period: 274 from January 2008, 265 from April 2008, and 285 from July 2008. A total of 345 (42%) patients were admitted during the day, and 479 (58%) at night; 641 (78%) were admitted on weekdays, and 183 (22%) on weekends. The 33 excluded charts were similar to the included charts for both time of admission and outcomes. Results for parametric testing and nonparametric testing, as well as for log‐transformation and non‐log‐transformation of the continuous outcomes were similar in both magnitude and statistical significance, so we present the parametric and nonlog‐transformed results below for ease of interpretation.

Interrater reliability among the 3 reviewers was very high. There were no disagreements among the 20 multiple reviews for either poor outcomes within 24 hours of admission or admitting service; the interclass correlation coefficients for 30 day repeat ED visit and 30 day readmission were 0.97 and 0.87, respectively.

Patients admitted at night or on the weekend were similar to patients admitted during the day and week across age, gender, insurance class, MDC, and Charlson Comorbidity Index (Table 1). For unadjusted outcomes, patients admitted at night has a similar LOS, hospital charges, 30 day repeat ED visits, 30 day readmissions, and poor outcome within 24 hours of admission as those patients admitted during the day. They had a potentially lower chance of any ICU transfer during hospitalization though this did not reach statistical significance at P < 0.05 (night admission 6%, day admission 3%, P = 0.06) (Table 2).

| Characteristics | Time of Day | Day of the Week | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day Admission (n = 345) | Night Admission (n = 479) | Weekday Admission (n = 641) | Weekend Admission (n = 183) | |

| ||||

| Age (years) | 60.8 | 59.7 | 60.6 | 58.7 |

| Gender (% male) | 47 | 43 | 45 | 46 |

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | ||||

| White, Asian, other | 61 | 54 | 57 | 55 |

| Black | 34 | 38 | 37 | 34 |

| Hispanic | 5 | 8 | 6 | 10 |

| Medicaid or self pay (%) | 9 | 10 | 10 | 11 |

| Major diagnostic category (%) | ||||

| Respiratory disease | 14 | 13 | 14 | 13 |

| Circulatory disease | 28 | 23 | 26 | 24 |

| Digestive disease | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| Other | 45 | 52 | 48 | 51 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 3.71 | 3.60 | 3.66 | 3.60 |

| Outcomes | Time of Day | Day of the Week | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day Admission (n = 345) | Night Admission (n = 479) | Weekday Admission (n = 641) | Weekend Admission (n = 183) | |

| ||||

| Length of stay | 4.3 | 4.1 | 4.3 | 3.8 |

| Hospital charges | $27,500 | $25,200 | $27,200* | $22,700* |

| ICU transfer during hospitalization (%) | 6 | 3 | 5* | 1* |

| Repeat ED visit at 30 days (%) | 20 | 22 | 22 | 21 |

| Readmission at 30 days (%) | 17 | 20 | 20 | 17 |

| Poor outcome at 24 hours (ICU transfer, cardiac arrest, or death)(%) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

Patients admitted to the hospital during the weekend were similar to patients admitted during the week for unadjusted LOS, 30 day repeat ED visit or readmission rate, and poor outcomes within 24 hours of admission as those admitted during the week; however, they had lower hospital charges (weekend admission $22,700, weekday admission $27,200; P = 0.02), and a lower chance of ICU transfer during hospitalization (weekend admission 1%, weekday admission 5%; P = 0.02) (Table 2).

In the multivariable linear and logistic regression models (Tables 3 and 4), we assessed the independent association between night admission or weekend admission and each hospitalization‐relevant outcome except for poor outcome within 24 hours of admission (poor outcome within 24 hours of admission was not modeled to avoid the risk of overfitting because there were only 13 total events). After adjustment for age, gender, race and ethnicity, admitting service (hospitalist or teaching), Medicaid or self‐pay insurance, MDC, and Charlson Comorbidity Index, there was no statistically significant association between night admission and worse outcomes for LOS, hospital charges, 30 day repeat ED visit, or 30 day readmission. Night admission was associated with a decreased chance of ICU transfer during hospitalization, but the difference was not statistically significant (odds ratio, 0.54; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.26‐1.11, P = 0.09). Weekend admission was not associated with worse outcomes for LOS or 30 day repeat ED visit or readmission; however, weekend admission was associated with a decrease in overall charges ($4400; 95% CI, $8300 to $600) and a decreased chance of ICU transfer during hospitalization (odds ratio, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.050.88).

| Predictors | Length of Stay (days), Coefficient (95% CI) | Hospital Charges (dollars), Coefficient (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Night admission | 0.23 (0.77 to 0.32) | 2100 (5400 to 1100) |

| Weekend admission | 0.42 (1.07 to 0.23) | 4400 (8300 to 600)* |

| Age | 0.01 (0.01 to 0.03) | 0 (100 to 100) |

| Male gender | 0.15 (0.70 to 0.39) | 400 (3700 to 2800) |

| Race, Black | 0.18 (0.41 to 0.78) | 200 (3700 to 3400) |

| Ethnicity, Hispanic | 0.62 (1.73 to 0.49) | 2300 (8900 to 4300) |

| Medicaid or self‐pay insurance | 1.87 (0.93 to 2.82)* | 8900 (3300 to 14600)* |

| Hospitalist service | 0.26 (0.29 to 0.81) | 600 (3900 to 2700) |

| MDC: respiratory | 0.36 (1.18 to 0.46) | 700 (4200 to 5600) |

| MDC: circulatory | 1.36 (2.04 to 0.68)* | 600 (4600 to 3400) |

| MDC: digestive | 1.22 (2.08 to 0.35)* | 6800 (12000 to 1700)* |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 0.35 (0.22 to 0.49)* | 2200 (1400 to 3000)* |

| Predictors | ICU Transfer during Hospitalization, Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Repeat ED Visit at 30 days, Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Readmission at 30 days, Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Night admission | 0.53 (0.26 to 1.11) | 1.13 (0.80 to 1.60) | 1.23 (0.86 to 1.78) |

| Weekend admission | 0.20 (0.05 to 0.88)* | 0.95 (0.63 to 1.44) | 0.80 (0.51 to 1.25) |

| Age | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.02) | 0.99 (0.98 to 1.002) | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.01) |

| Male gender | 0.98 (0.47 to 2.02) | 1.09 (0.78 to 1.54) | 0.91 (0.64 to 1.31) |

| Race, Black | 0.75 (0.33 to 1.70) | 1.48 (1.02 to 2.14)* | 1.12 (0.76 to 1.65) |

| Ethnicity, Hispanic | 0.76 (0.16 to 3.73) | 1.09 (0.55 to 2.17) | 1.11 (0.55 to 2.22) |

| Medicaid or self‐pay insurance | 0.75 (0.16 to 3.49) | 1.61 (0.95 to 2.72) | 2.14 (1.24 to 3.67)* |

| Hospitalist service | 0.68 (0.33 to 1.44) | 1.15 (0.81 to 1.63) | 0.99 (0.69 to 1.43) |

| MDC: respiratory | 1.18 (0.41 to 3.38) | 1.02 (0.61 to 1.69) | 1.16 (0.69 to 1.95) |

| MDC: circulatory | 1.22 (0.52 to 2.87) | 0.79 (0.51 to 1.22) | 0.80 (0.51 to 1.27) |

| MDC: digestive | 0.51 (0.11 to 2.32) | 0.83 (0.47 to 1.46) | 1.08 (0.62 to 1.91) |

| Charlson Comobrbidity Index | 1.25 (1.09 to 1.45)* | 1.09 (1.01 to 1.19)* | 1.11 (1.02 to 1.21)* |

Our multivariate models explained very little of the variance in patient outcomes. For LOS and hospital charges, adjusted R2 values were 0.06 and 0.05, respectively. For ICU transfer during hospitalization, 30 day repeat ED visit, and 30 day readmission, the areas under the receiver operator curves were 0.75, 0.51, and 0.61 respectively.

To assess the robustness of our conclusions regarding night admission, we redefined night to include only patients admitted between the hours of 8 pm and 5:59 am. This did not change our conclusions. We also tested for interaction between night admission and weekend admission for all outcomes to assess whether night admissions on the weekend were in fact at increased risk of worse outcomes; we found no evidence of interaction (P > 0.3 for the interaction terms in each model).

Discussion

Among patients admitted to the medicine services at our academic medical center, night or weekend admission was not associated with worse hospitalization‐relevant outcomes. In some cases, night or weekend admission was associated with better outcomes, particularly in terms of ICU transfer during hospitalization and hospital charges. Prior research indicates worse outcomes during off‐hours,5 but we did not replicate this finding in our study.

The finding that admission at night was not associated with worse outcomes, particularly proximal outcomes such as LOS or ICU transfer during hospitalization, was surprising, though reassuring in view of the fact that more than half of our patients are admitted at night. We believe a few factors may be responsible. First, our general medicine service is staffed during the night (7 pm to 7 am) by in‐house nocturnists and night float residents. Second, our staffing ratio, while lower at night than during the day, remains the same on weekends and may be higher than in other settings. In continuously well‐staffed settings such as the ED12 and ICU,13 night and weekend admissions are only inconsistently associated with worse outcomes, which may be the same phenomena we observed in the current study. Third, the hospital used as the site of this study has received Nursing Magnet recognition and numerous quality awards such as the National Research Corporation's Consumer Choice Award and recognition as a Distinguished Hospital for Clinical Excellence by HealthGrades. Fourth, our integrated electronic medical record, computerized physician order entry system, and automatically generated sign out serve as complements to the morning hand off. Fifth, hospitalists and teaching teams rotate on a weekly, biweekly, or every 4 week basis, which may protect against discontinuity associated with the weekend. We believe that all of these factors may facilitate alert, comprehensive care during the night and weekend as well as safe and efficient transfer of patients from the night to the day providers.

We were also surprised by the association between weekend admission and lower charges and a lower chance of ICU transfer during hospitalization. We believe many of the same factors noted above may have played a role in these findings. In terms of hospital charges, it is possible that some workups were completed outside of the hospital rather than during the hospitalization, and that some tests were not ordered at all due to unavailability on weekends. The decreased chance of ICU transfer is unexplained. We hypothesize that there may have been a more conservative admission strategy within the ED, such that patients with high baseline severity were admitted directly to the ICU on the weekend rather than being admitted first to the general medicine floor. This hypothesis requires further study.

Our study had important limitations. It was a retrospective study from a single academic hospital. The sample size lacked sufficient power to detect differences in the low frequency of certain outcomes such as poor outcomes within 24 hours of admission (2% vs. 1%), and also for more frequent outcomes such as 30 day readmission; it is possible that with a larger sample there would have been statistically significant differences. Further, we recognize that the Charlson Comorbidity Index, which was developed to predict 1‐year mortality for medicine service patients, does not adjust for severity of illness at presentation, particularly for outcomes such as readmission. If patients admitted at night and during the weekend were less acutely ill despite having similar comorbidities and MDCs at admission, true associations between time of admission and worse outcomes could have been masked. Furthermore, the multivariable modeling explained very little of the variance in patient outcomes such that significant unmeasured confounding may still be present, and consequently our results cannot be interpreted in a causal way. Data was collected from electronic records, so it is possible that some adverse events were not recorded. However, it seems unlikely that major events such as death and transfer to an ICU would have been missed.

Several aspects of the study strengthen our confidence in the findings, including a large sample size, relevance of the outcomes, the adjustment for confounders, and an assessment for robustness of the conclusions based on restricting the definition of night and also testing for interaction between night and weekend admission. Our patient demographics and insurance mix resemble that of other academic hospitals,10 and perhaps our results may be generalizable to these settings, if not to non‐urban or community hospitals. Furthermore, the Charlson Comorbidity Index was associated with all 5 of the modeled outcomes we chose for our study, reaffirming their utility in assessing the quality of hospital care. Future directions for investigation may include examining the association of night admission with hospitalization‐relevant outcomes in nonacademic, nonurban settings, and examining whether the lack of association between night and weekend admission and worse outcomes persists with adjustment for initial severity of illness.

In summary, at a large, well‐staffed urban academic hospital, day or time of admission were not associated with worse hospitalization‐relevant outcomes. The use of nocturnists and night float teams for night admissions and continuity across weekends appears to be a safe approach to handling the increased volume of patients admitted at night, and a viable alternative to overnight call in the era of work hour restrictions.

- ,,, et al.Three‐year results of mandated work hour restrictions: attending and resident perspectives and effects in a community hospital.Am Surg.2008;74(6):542–546; discussion 546–547.

- ,,, et al.Handoffs causing patient harm: a survey of medical and surgical house staff.Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf.2008;34(10):563–570.

- ,,,,.Does housestaff discontinuity of care increase the risk for preventable adverse events?Ann Intern Med.1994;121(11):866–872.

- ,.Mortality among patients admitted to hospitals on weekends as compared with weekdays.N Engl J Med.2001;345(9):663–668.

- ,,, et al.Survival from in‐hospital cardiac arrest during nights and weekends.JAMA.2008;299(7):785–792.

- ,,,.Continuity of care and intensive care unit use at the end of life.Arch Intern Med.2009;169(1):81–86.

- ,,,,,.Continuity of outpatient and inpatient care by primary care physicians for hospitalized older adults.JAMA.2009;301(16):1671–1680.

- ,,,.Why predictive indexes perform less well in validation studies: is it magic or methods?Arch Intern Med.1987;147:2155–2161.

- ,,.Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD‐9‐CM administrative databases.J Clin Epidemiol.1992;45(6):613–619.

- ,,, et al.Implementation of a physician assistant/hospitalist service in an academic medical center: impact on efficiency and patient outcomes.J Hosp Med.2008;3(5):361–368.

- ,,, et al.Use of an admission early warning score to predict patient morbidity and mortality and treatment success.Emerg Med J.2008;25(12):803–806.

- ,,.The impact of weekends on outcome for emergency patients.Clin Med.2005;5(6):621–625.

- ,,,,,.Off hour admission to an intensivist‐led ICU is not associated with increased mortality.Crit Care.2009;13(3):R84.

- ,,, et al.Three‐year results of mandated work hour restrictions: attending and resident perspectives and effects in a community hospital.Am Surg.2008;74(6):542–546; discussion 546–547.

- ,,, et al.Handoffs causing patient harm: a survey of medical and surgical house staff.Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf.2008;34(10):563–570.

- ,,,,.Does housestaff discontinuity of care increase the risk for preventable adverse events?Ann Intern Med.1994;121(11):866–872.

- ,.Mortality among patients admitted to hospitals on weekends as compared with weekdays.N Engl J Med.2001;345(9):663–668.

- ,,, et al.Survival from in‐hospital cardiac arrest during nights and weekends.JAMA.2008;299(7):785–792.

- ,,,.Continuity of care and intensive care unit use at the end of life.Arch Intern Med.2009;169(1):81–86.

- ,,,,,.Continuity of outpatient and inpatient care by primary care physicians for hospitalized older adults.JAMA.2009;301(16):1671–1680.

- ,,,.Why predictive indexes perform less well in validation studies: is it magic or methods?Arch Intern Med.1987;147:2155–2161.

- ,,.Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD‐9‐CM administrative databases.J Clin Epidemiol.1992;45(6):613–619.

- ,,, et al.Implementation of a physician assistant/hospitalist service in an academic medical center: impact on efficiency and patient outcomes.J Hosp Med.2008;3(5):361–368.

- ,,, et al.Use of an admission early warning score to predict patient morbidity and mortality and treatment success.Emerg Med J.2008;25(12):803–806.

- ,,.The impact of weekends on outcome for emergency patients.Clin Med.2005;5(6):621–625.

- ,,,,,.Off hour admission to an intensivist‐led ICU is not associated with increased mortality.Crit Care.2009;13(3):R84.

Copyright © 2010 Society of Hospital Medicine

What Are the Chances a Hospitalized Patient Will Survive In-Hospital Arrest?

Case

A 66-year-old woman with metastatic, non-small-cell carcinoma of the lung, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and hypertension presents with progressive shortness of breath and back pain. Her vital signs are normal, with the exception of tachypnea and an oxygen saturation of 84% on room air. A CT scan shows marked progression of her disease and new metastases to her spine. You begin a discussion about advance directives and code status. During the exchange, the patient asks for guidance regarding resuscitation. How can you best answer her questions about the likelihood of surviving an in-hospital arrest?

Background

Discussion regarding resuscitation status is a challenge for most hospitalists. The absence of an established relationship, limited time, patient emotion, and difficulty applying general scientific data to a single patient coalesce into a complex interaction. Further complicating matters, patients frequently have unrealistic expectations and overestimate their chance of survival.

Experience has shown that many patients pursue what physicians consider inappropriately aggressive resuscitation measures. Before you have an informed discussion about cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) outcomes, patients tend to overestimate their likelihood of survival.1 In 2009, Kaldjian and colleagues found that patients’ initial mean prediction of post-arrest survival was 60.4%, compared with the actual mean of approximately 17%.2,3 Furthermore, nearly half of the patients who initially expressed a desire to receive CPR in the event of cardiac arrest opted to change their code status after they were informed of the actual survival estimates.1,2

Patient autonomy and the law, as defined by the 1990 Patient Self-Determination Act, require that physicians share responsibility with patients in making prospective resuscitation decisions.4 Shared decision-making necessitates a basic discussion on admission within the context of the patient’s prognosis and previously expressed wishes. It might simply include an acknowledgment of a previously completed advance directive. A more complex discussion might require in-depth conversation to address patient performance status, prognosis of acute and chronic illnesses, and education about the typical resuscitation procedures. After listening to the patient’s perspective, the admitting physician can provide input and an interpretation of available data regarding the patient’s likelihood of surviving an in-hospital arrest.

Review of the Data

In the past 40 years, the overall survival rates for cardiac arrest have changed little. Despite numerous advances made in the delivery of medical care, on average, only 17% of all adult arrest patients survive to hospital discharge.3 A variety of factors influence this overall survival rate, both pre-arrest and intra-arrest. Clinical experience allows most physicians to sense what probability a patient has for survival and quality of life following a cardiac arrest. However, anecdotal evidence alone does not provide a patient and their family with the information necessary to make an informed decision regarding code status.

Numerous studies have investigated the patient factors that might influence how likely one is to survive a cardiac arrest. Researchers have paid particular attention to such factors as age, race, presence or absence of a cancer diagnosis, and associated comorbidities. Not surprisingly, older age has been shown to be significantly associated with a lower likelihood of survival to discharge following cardiac arrest.5,6

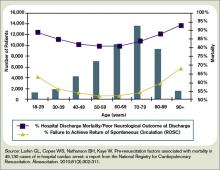

Ehlenbach and colleagues examined medical data from 433,985 Medicare patients 65 and older who underwent in-hospital CPR.5 Both older age and prior residence in a skilled nursing facility were found to be associated with poorer survival rates.5 Although neither study was able to define an upper-age cutoff for certain peri-arrest mortality, age affects overall survival likelihood in an inverse fashion, with those 85 and older having only a 6% chance of surviving to hospital discharge (see Figure 1, p. 18).1,5,6

The degree of comorbid illness can be used to help predict mortality following cardiac arrest. Review of data from the National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (NRCPR) identified particular comorbidities that portend poor post-arrest prognosis.6 In general, the more pre-existing comorbidities a patient has, the less likely they are to survive.6 The presence of hepatic insufficiency, acute stroke, immunodeficiency, renal failure, or dialysis were associated with lower survival rates (see Figure 2, right).6,7

Poor performance status on admission, defined as severe disability, coma, or vegetative state, was predictive of worse outcomes.6 Understandably, patients with hypotension and those who required vasopressors or mechanical ventilation also tended to have lower post-arrest survival rates.6

The presence of a cancer diagnosis is another prognostic factor of interest when considering the chances of surviving an arrest. Classically, CPR was thought to be a futile intervention in this patient population. Specific characteristics within this subset of patients have been shown to influence prognosis, and multiple studies have confirmed that cancer patients generally do worse after an arrest with an overall survival rate of only 6.2%.8 Survival rates tend to be lower in patients with metastatic disease, hematologic malignancies, a history of stem cell transplant, those who arrest within an ICU, and inpatients whose cardiac arrest was anticipated.8,9

In fact, cancer patients whose hospital course followed a path of gradual deterioration showed a 0% survival rate.9 In patients with metastatic disease, poor performance status prior to arrest appeared to account for their particularly poor survival odds (this supports the intuitive, rule-of-thumb that sicker cancer patients have worse outcomes).8

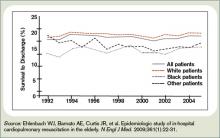

Growing evidence suggests the probability of post-arrest survival is not equal between racial groups. Specifically, black or nonwhite race is associated with higher utilization of CPR and lower survival rates (see Figure 3, right).10 Among Medicare patients, Ehlenbach and colleagues found that black and nonwhite patients were much more likely to undergo CPR, presumably as a result of being less likely to opt for DNR status.5,10 Although this could account for the differences seen in survival rates among these populations, these findings also raise concerns about the possibility of racial disparities in medical care. A subsequent cohort study also suggested that blacks and nonwhites were less likely to survive following cardiac arrest.10 However, adjusted analysis revealed that these differences were strongly associated with the medical center at which these patients received care. Therefore, although being nonwhite does portend worse outcomes following an arrest, the increased risk is likely attributed to the fact that many of these patients receive care at hospitals that have poorer overall CPR performance measures.5,10

Survival is not the only outcome measure patients need to take into account when deciding whether to undergo CPR. Quality of life following resuscitation also warrants consideration. Interestingly, research has shown that neurologic outcomes among the majority of cardiac arrest survivors are generally good.3

Approximately 86% of survivors with intact pre-arrest cerebral performance maintain it on discharge, and only a minority of survivors are eventually declared brain-dead.3 Still, there are certain peri-arrest factors that pose risk for poorer neurologic and functional outcomes. For arrest from a shockable rhythm, time to defibrillation is a key determinant.11 In patients for whom time to defibrillation is greater than two minutes, there is significantly higher risk of permanent disability following cardiac arrest.11

In the event of coma following resuscitation, particular clinical findings can be used to accurately predict poor outcome.12 The absence of pupillary reflexes, corneal reflexes, or absent or extensor motor responses three days after arrest are poor prognostic indicators.12 As a general rule, if a patient does not awaken within three days, neurologic and functional impairment can be expected.12 For those patients who do survive to hospital discharge, more than 50% ultimately will be able to be discharged home.3

However, nearly a quarter will need to be newly placed in a rehabilitation or skilled nursing facility.3

Back to the Case

The patient was admitted with hypoxia secondary to both progressive lung malignancy and COPD exacerbation. She had no advanced directives, so the admitting hospitalist, in collaboration with her oncologist, had a detailed discussion regarding her understanding of her disease progression, prognosis, and goals for her remaining time. Her questions regarding survivability of cardiac arrest were answered directly with an estimate of 5% to 10%, based on her age, comorbidities, and the presence of advanced malignancy.

After hearing this information, the patient responded, “I still want everything done.” The hospitalist acknowledged her feelings of wanting to fight on, but asked her to think about what “everything” meant to her. After taking some additional time to reflect with friends and family, the patient was clear that she wanted to continue disease-focused therapies, but did not want to be resuscitated in the event of cardiac or pulmonary arrest.

Eventually, her hypoxia improved with antibiotics, steroids, and bronchodilators. She was discharged home with follow-up in the oncology clinic for additional chemotherapy and palliative radiation.

Bottom Line

For hospitalized adults, the average survival rate to discharge after cardiac arrest is about 17%. Many factors lower a patient’s chance of survival, including advanced age, performance status, malignancy, and presence of multiple comorbidities. TH

Dr. Neagle and Dr. Wachsberg are hospitalists and instructors in the division of hospital medicine at Northwestern University Medical Center in Chicago.

References

- Murphy DJ, Burrows D, Santali S, et al. The influence of the probability of survival on patients’ preferences regarding cardiopulmonary resuscitation. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(8):545-549.

- Kaldjian LC, Erekson ZD, Haberle TH, et al. Code status discussions and goals of care among hospitalised adults. J Med Ethics. 2009;35(6):338-342.

- Peberdy MA, Kaye W, Ornato JP, et al. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation of adults in the hospital: a report of 14720 cardiac arrests from the National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2003;58(3):297-308.

- La Puma J, Orentlicher D, Moss RJ. Advance directives on admission. Clinical implications and analysis of the Patient Self-Determination Act of 1990. JAMA. 1991;266(3):402-405.

- Ehlenbach WJ, Barnato AE, Curtis JR, et al. Epidemiologic study of in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(1):22-31.

- Larkin GL, Copes WS, Nathanson BH, Kaye W. Pre-resuscitation factors associated with mortality in 49,130 cases of in-hospital cardiac arrest: a report from the National Registry for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2010;81(3):302-311.

- de Vos R, Koster RW, De Haan RJ, Oosting H, van der Wouw PA, Lampe-Schoenmaeckers AJ. In-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation: prearrest morbidity and outcome. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(8):845-850.

- Reisfield GM, Wallace SK, Munsell MF, Webb FJ, Alvarez ER, Wilson GR. Survival in cancer patients undergoing in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a meta-analysis. Resuscitation. 2006;71(2):152-160.

- Ewer MS, Kish SK, Martin CG, Price KJ, Feeley TW. Characteristics of cardiac arrest in cancer patients as a predictor of survival after cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Cancer. 2001;92(7):1905-1912.

- Chan PS, Nichol G, Krumholz HM, et al. Racial differences in survival after in-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA. 2009;302(11):1195-1201.

- Chan PS, Krumholz HM, Nichol G, Nallamothu BK. Delayed time to defibrillation after in-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(1):9-17.