User login

Febrile Ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann Disease: A Rare Form of Pityriasis Lichenoides et Varioliformis Acuta

To the Editor:

Pityriasis lichenoides is a papulosquamous dermatologic disorder that is characterized by recurrent papules.1 There is a spectrum of disease in pityriasis lichenoides that includes pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA) at one end and pityriasis lichenoides chronica at the other. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta is more common in younger individuals and is characterized by erythematous papules that often crust; these lesions resolve over weeks. The lesions of pityriasis lichenoides chronica are characteristically scaly, pink to red-brown papules that tend to resolve over months.1

Histologically, PLEVA exhibits parakeratosis, interface dermatitis, and a wedge-shaped infiltrate.1 Necrotic keratinocytes and extravasated erythrocytes also are common features. Additionally, monoclonal T cells may be present in the infiltrate.1

Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease (FUMHD) is a rare and severe variant of PLEVA. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease is characterized by ulceronecrotic lesions, fever, and systemic symptoms.2 Herein, we present a case of FUMHD.

A 57-year-old man presented with an eruption of painful lesions involving the face, trunk, arms, legs, and genitalia of 1 month’s duration. The patient denied oral and ocular involvement. He had soreness and swelling of the arms and legs. A prior 12-day course of prednisone prescribed by a community dermatologist failed to improve the rash. A biopsy performed by a community dermatologist was nondiagnostic. The patient denied fever but did report chills. He had no preceding illness and was not taking new medications. On physical examination, the patient was afebrile and normotensive with innumerable deep-seated pustules and crusted ulcerations on the face, palms, soles, trunk, extremities, and penis (Figures 1 and 2). There was a background morbilliform eruption on the trunk. The ocular and oral mucosae were spared. The upper and lower extremities had pitting edema.

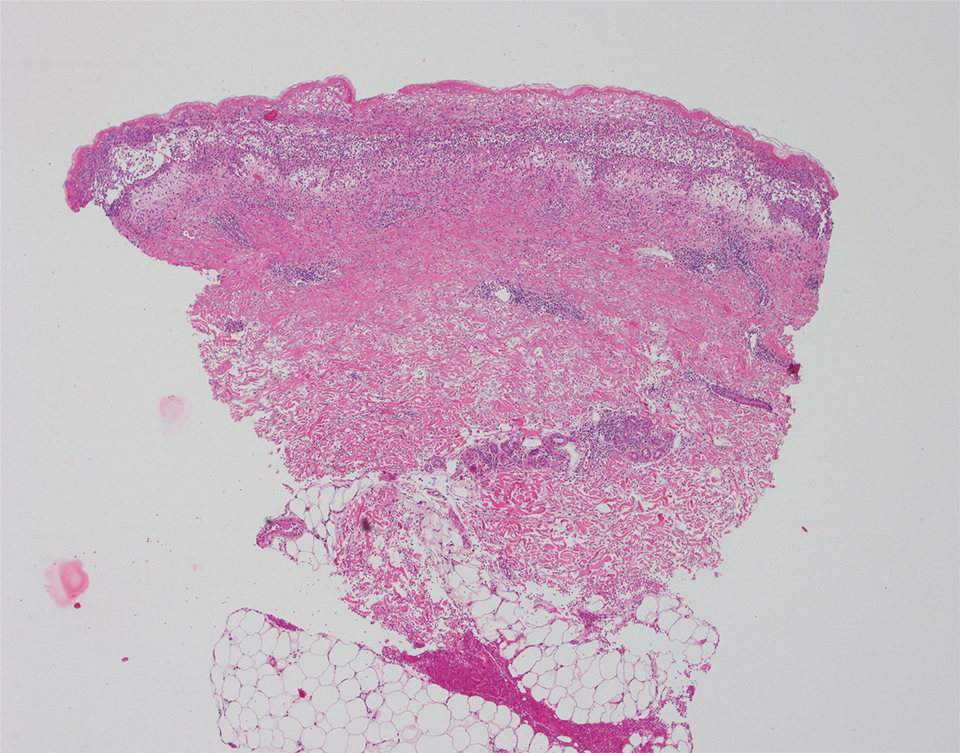

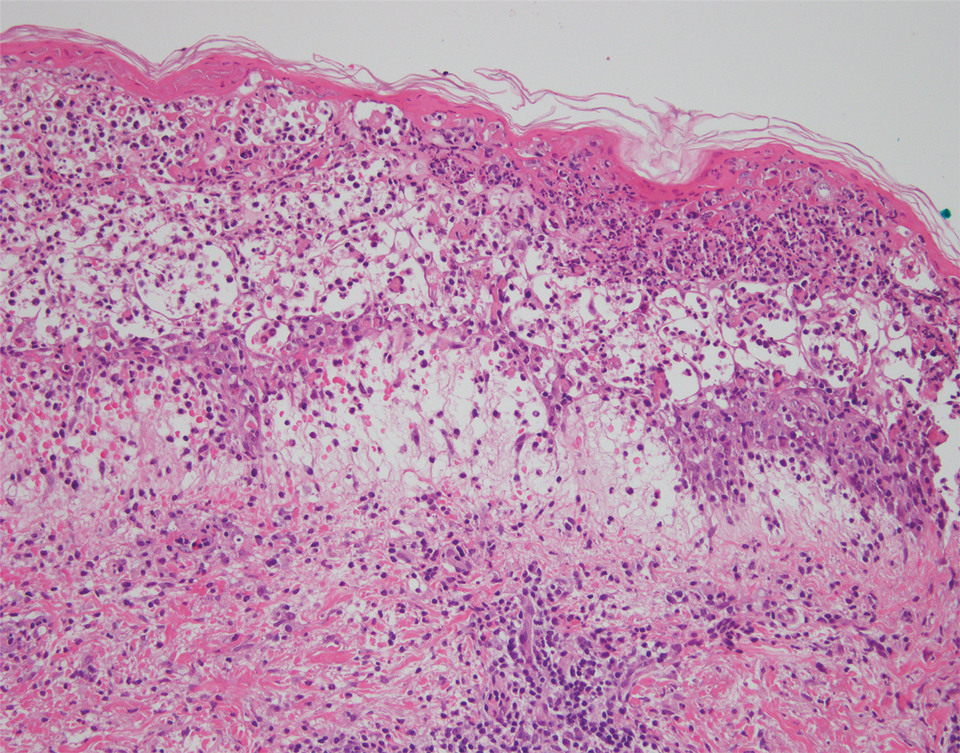

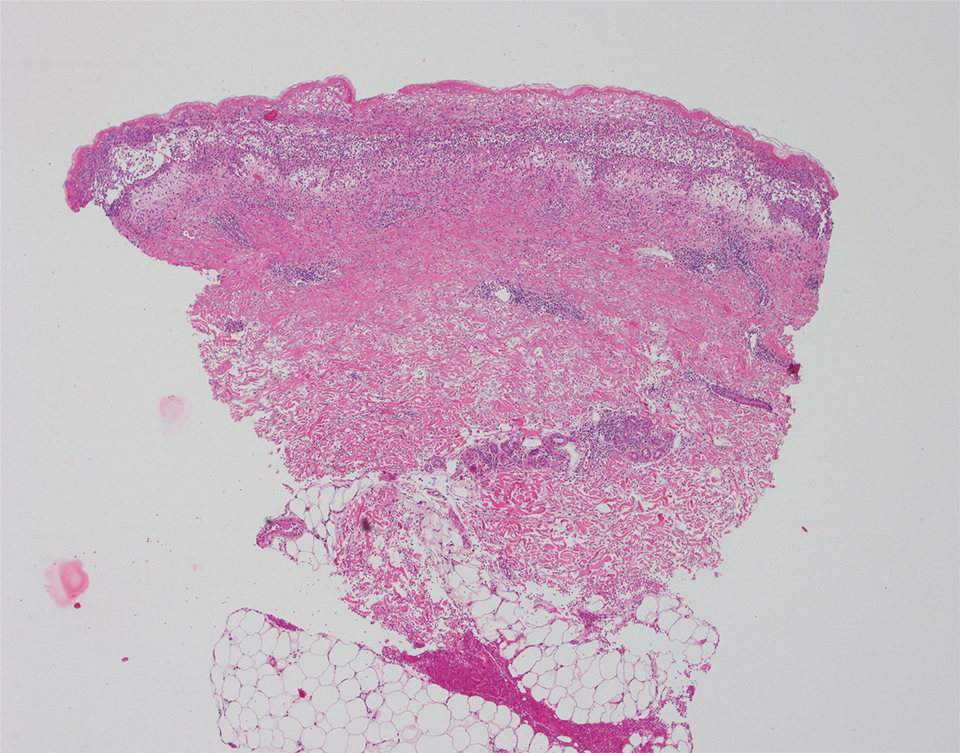

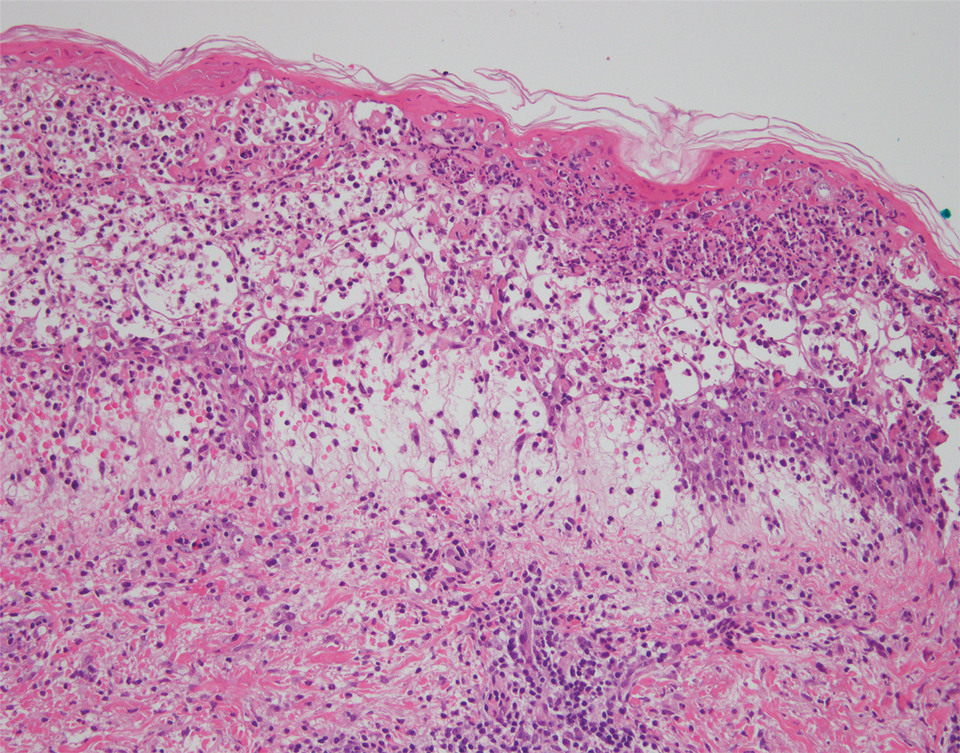

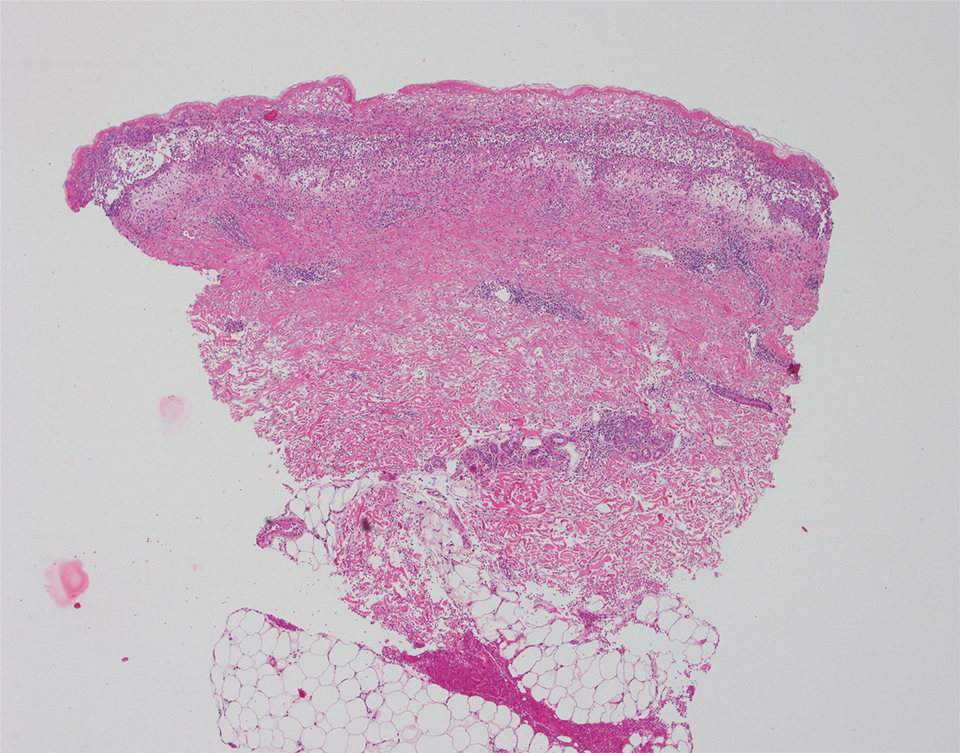

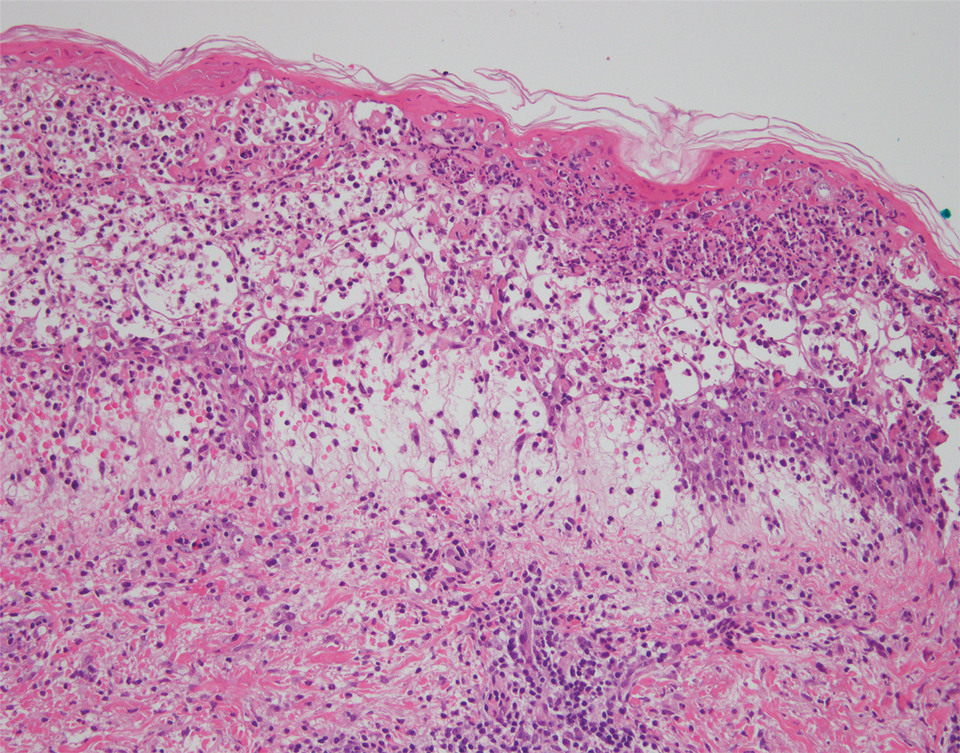

The patient’s alanine aminotransaminase and aspartate aminotransaminase levels were elevated at 55 and 51 U/L, respectively. His white blood cell count was within reference range; however, there was an elevated absolute neutrophil count (8.7×103/μL). No eosinophilia was noted. Laboratory evaluation showed a positive antimitochondrial antibody, and magnetic resonance imaging showed evidence of steatohepatitis. Punch biopsies from both the morbilliform eruption and a deep-seated pustule showed epidermal necrosis, parakeratosis, necrotic keratinocytes, and a lichenoid infiltrate of lymphocytes at the dermoepidermal interface. In the dermis, there was a wedge-shaped superficial and deep, perivascular infiltrate with extravasated erythrocytes (Figures 3 and 4). Tissue Gram stain was negative for bacteria. Varicella-zoster virus and herpes simplex virus immunostains were negative. Direct immunofluorescence showed colloid bodies, as can be seen in lichenoid dermatitis.

At the next clinic visit, the patient reported a fever of 39.4 °C. After reviewing the patient’s histopathology and clinical picture, along with the presence of fever, a final diagnosis of FUMHD was made. The patient was started on an oral regimen of prednisone 80 mg once daily, minocycline 100 mg twice daily, and methotrexate 15 mg weekly. Unna boots (specialized compression wraps) with triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% were placed weekly until the leg edema and ulcerations healed. He was maintained on methotrexate 15 mg weekly and 5 to 10 mg of prednisone once daily. The patient demonstrated residual scarring, with only rare new papulonodules that did not ulcerate when attempts were made to taper his medications. He was followed for nearly 3 years, with a recurrence of symptoms 2 years and 3 months after initial presentation to the academic dermatology clinic.

Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease is a rare and severe variant of PLEVA that can present with the rapid appearance of necrotic skin lesions, fever, and systemic manifestations, including pulmonary, gastrointestinal, central nervous system, cardiac, hematologic, and rheumatologic symptoms.2-4 The evolution from PLEVA to FUMHD ranges from days to weeks, and patientsrarely can have an initial presentation of FUMHD.2 The duration of illness has been reported to be 1 to 24 months5; however, the length of illness still remains unclear, as many studies of FUMHD are case reports with limited follow-up. Our patient had a disease duration of at least 27 months. The lesions of FUMHD usually are generalized with flexural prominence, and mucosal involvement occurs in approximately one-quarter of cases. Hypertrophic scarring may be seen after the ulcerated lesions heal.2 The incidence of FUMHD is higher in men than in women, and it is more common in younger individuals.2,6 There have been reported fatalities associated with FUMHD, mostly in adults.2,4

The clinical differential diagnosis for PLEVA includes disseminated herpes zoster, varicella-zoster virus or coxsackievirus infections, lymphomatoid papulosis, angiodestructive lymphoma such as extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma, drug eruption, arthropod bite, erythema multiforme, ecthyma, ecthyma gangrenosum, necrotic folliculitis, and cutaneous small vessel vasculitis. To differentiate between these diagnoses and PLEVA or FUMHD, it is important to take a strong clinical history. For example, for varicella-zoster virus and coxsackievirus infections, exposure history to the viruses and vaccination history for varicella-zoster virus can help elucidate the diagnosis.

Skin biopsy can help differentiate between these entities and PLEVA or FUMHD. The histopathology of a nonulcerated lesion of FUMHD shows parakeratosis, spongiosis, and lymphocyte exocytosis, as well as lymphocytic vasculitis—findings commonly seen in PLEVA. With the ulceronecrotic lesions of FUMHD, epidermal necrosis and ulceration can be seen microscopically.2 Although skin biopsy is not absolutely necessary for making the diagnosis of PLEVA, it can be helpful.3 However, given the dramatic and extreme clinical impression with an extensive differential diagnosis that includes disorders ranging from infectious to neoplastic, biopsy of FUMHD with clinicopathologic correlation often is required.

It is important to avoid biopsying ulcerated lesions of FUMHD, as the histopathologic findings are more likely to be nonspecific. Additionally, nonspecific features often are seen with immunohistochemistry; abnormal laboratory testing may be seen in FUMHD, but there is no specific test to diagnose FUMHD.2 Finally, a predominantly CD8+ cell infiltrate was seen in 4 of 6 cases of FUMHD, with 2 cases showing a mixed infiltrate of CD8+ and CD4+ cells.5,7-10

Although no unified diagnostic criterion exists for FUMHD, Nofal et al2 proposed criteria comprised of constant features, which are found in every case of FUMHD and can confirm the diagnosis alone, and variable features to help ensure that cases of FUMHD are not missed. The constant features include fever, acute onset of generalized ulceronecrotic papules and plaques, a course that is rapid and progressive (without a tendency for spontaneous resolution), and histopathology that is consistent with PLEVA. The variable features include history of PLEVA, involvement of mucous membranes, and systemic involvement.2

No single unifying treatment modality for all cases of FUMHD has been described. Immunosuppressive drugs (eg, systemic steroids, methotrexate), antibiotics, antivirals, phototherapy, intravenous immunoglobulin, and dapsone have been tried in patients with FUMHD.2 Combination therapy with an oral medication such as erythromycin or methotrexate and psoralen plus UVA may be effective for FUMHD.3 Additionally, some authors believe that patients with FUMHD should be treated similar to burn victims with intensive supportive care.2

The etiology of PLEVA is unknown, but it is presumed to be associated with an effector cytotoxic T-cell response to either an infectious agent or a drug.11

Four cases of FUMHD with monoclonality have been reported,4,7,8 and some researchers propose that FUMHD may be a subset of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.7 However, 2 other cases of FUMHD did not show monoclonality of T cells,5,18 suggesting that FUMHD may represent an inflammatory disorder, rather than a lymphoproliferative process of T cells.18 Given the controversy surrounding the clonality of FUMHD, T-cell gene rearrangement studies were not performed in our case.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al. Other papulosquamous disorders. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al, eds. Dermatology Essentials. Elsevier Saunders; 2014:68-69.

- Nofal A, Assaf M, Alakad R, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease: proposed diagnostic criteria and therapeutic evaluation. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:729-738.

- Milligan A, Johnston GA. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta. In: Lebwohl MG, Heymann WR, Berth-Jones J, et al, eds. Treatment of Skin Disease, Comprehensive Therapeutic Strategies. 4th ed. Saunders; 2013:580-582.

- Miyamoto T, Takayama N, Kitada S, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease: a case report and a review of the literature. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:795-797.

- Meziane L, Caudron A, Dhaille F, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease: treatment with infliximab and intravenous immunoglobulins and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2012;225:344-348.

- Robinson AB, Stein LD. Miscellaneous conditions associated with arthritis. In: Kliegman RM, Stanton BF, St. Geme JW III, et al, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 19th ed. W.B. Saunders Company; 2011:880.

- Cozzio A, Hafner J, Kempf W, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease with clonality: a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma entity? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:1014-1017.

- Tsianakas A, Hoeger PH. Transition of pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta to febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease is associated with elevated serum tumour necrosis factor-alpha. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:794-799.

- Yanaba K, Ito M, Sasaki H, et al. A case of febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease requiring debridement of necrotic skin and epidermal autograft. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:1249-1253.

- Lode HN, Döring P, Lauenstein P, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease following suspected hemorrhagic chickenpox infection in a 20-month-old boy. Infection. 2015;43:583-588.

- Tomasini D, Tomasini CF, Cerri A, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides: a cytotoxic T-cell-mediated skin disorder: evidence of human parvovirus B19 DNA in nine cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:531-538.

- Weiss LM, Wood GS, Ellisen LW, et al. Clonal T-cell populations in pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (Mucha-Habermann disease). Am J Pathol. 1987;126:417-421.

- Dereure O, Levi E, Kadin ME. T-cell clonality in pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta: a heteroduplex analysis of 20 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1483-1486.

- Weinberg JM, Kristal L, Chooback L, et al. The clonal nature of pityriasis lichenoides. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1063-1067.

- Fortson JS, Schroeter AL, Esterly NB. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (parapsoriasis en plaque): an association with pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta in young children. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:1449-1453.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al, eds. Dermatology Essentials. Elsevier Saunders; 2014:958.

- Kim JE, Yun WJ, Mun SK, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta and pityriasis lichenoides chronica: comparison of lesional T-cell subsets and investigation of viral associations. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:649-656.

- López-Estebaran´z JL, Vanaclocha F, Gil R, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29(5, pt 2):903-906.

To the Editor:

Pityriasis lichenoides is a papulosquamous dermatologic disorder that is characterized by recurrent papules.1 There is a spectrum of disease in pityriasis lichenoides that includes pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA) at one end and pityriasis lichenoides chronica at the other. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta is more common in younger individuals and is characterized by erythematous papules that often crust; these lesions resolve over weeks. The lesions of pityriasis lichenoides chronica are characteristically scaly, pink to red-brown papules that tend to resolve over months.1

Histologically, PLEVA exhibits parakeratosis, interface dermatitis, and a wedge-shaped infiltrate.1 Necrotic keratinocytes and extravasated erythrocytes also are common features. Additionally, monoclonal T cells may be present in the infiltrate.1

Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease (FUMHD) is a rare and severe variant of PLEVA. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease is characterized by ulceronecrotic lesions, fever, and systemic symptoms.2 Herein, we present a case of FUMHD.

A 57-year-old man presented with an eruption of painful lesions involving the face, trunk, arms, legs, and genitalia of 1 month’s duration. The patient denied oral and ocular involvement. He had soreness and swelling of the arms and legs. A prior 12-day course of prednisone prescribed by a community dermatologist failed to improve the rash. A biopsy performed by a community dermatologist was nondiagnostic. The patient denied fever but did report chills. He had no preceding illness and was not taking new medications. On physical examination, the patient was afebrile and normotensive with innumerable deep-seated pustules and crusted ulcerations on the face, palms, soles, trunk, extremities, and penis (Figures 1 and 2). There was a background morbilliform eruption on the trunk. The ocular and oral mucosae were spared. The upper and lower extremities had pitting edema.

The patient’s alanine aminotransaminase and aspartate aminotransaminase levels were elevated at 55 and 51 U/L, respectively. His white blood cell count was within reference range; however, there was an elevated absolute neutrophil count (8.7×103/μL). No eosinophilia was noted. Laboratory evaluation showed a positive antimitochondrial antibody, and magnetic resonance imaging showed evidence of steatohepatitis. Punch biopsies from both the morbilliform eruption and a deep-seated pustule showed epidermal necrosis, parakeratosis, necrotic keratinocytes, and a lichenoid infiltrate of lymphocytes at the dermoepidermal interface. In the dermis, there was a wedge-shaped superficial and deep, perivascular infiltrate with extravasated erythrocytes (Figures 3 and 4). Tissue Gram stain was negative for bacteria. Varicella-zoster virus and herpes simplex virus immunostains were negative. Direct immunofluorescence showed colloid bodies, as can be seen in lichenoid dermatitis.

At the next clinic visit, the patient reported a fever of 39.4 °C. After reviewing the patient’s histopathology and clinical picture, along with the presence of fever, a final diagnosis of FUMHD was made. The patient was started on an oral regimen of prednisone 80 mg once daily, minocycline 100 mg twice daily, and methotrexate 15 mg weekly. Unna boots (specialized compression wraps) with triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% were placed weekly until the leg edema and ulcerations healed. He was maintained on methotrexate 15 mg weekly and 5 to 10 mg of prednisone once daily. The patient demonstrated residual scarring, with only rare new papulonodules that did not ulcerate when attempts were made to taper his medications. He was followed for nearly 3 years, with a recurrence of symptoms 2 years and 3 months after initial presentation to the academic dermatology clinic.

Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease is a rare and severe variant of PLEVA that can present with the rapid appearance of necrotic skin lesions, fever, and systemic manifestations, including pulmonary, gastrointestinal, central nervous system, cardiac, hematologic, and rheumatologic symptoms.2-4 The evolution from PLEVA to FUMHD ranges from days to weeks, and patientsrarely can have an initial presentation of FUMHD.2 The duration of illness has been reported to be 1 to 24 months5; however, the length of illness still remains unclear, as many studies of FUMHD are case reports with limited follow-up. Our patient had a disease duration of at least 27 months. The lesions of FUMHD usually are generalized with flexural prominence, and mucosal involvement occurs in approximately one-quarter of cases. Hypertrophic scarring may be seen after the ulcerated lesions heal.2 The incidence of FUMHD is higher in men than in women, and it is more common in younger individuals.2,6 There have been reported fatalities associated with FUMHD, mostly in adults.2,4

The clinical differential diagnosis for PLEVA includes disseminated herpes zoster, varicella-zoster virus or coxsackievirus infections, lymphomatoid papulosis, angiodestructive lymphoma such as extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma, drug eruption, arthropod bite, erythema multiforme, ecthyma, ecthyma gangrenosum, necrotic folliculitis, and cutaneous small vessel vasculitis. To differentiate between these diagnoses and PLEVA or FUMHD, it is important to take a strong clinical history. For example, for varicella-zoster virus and coxsackievirus infections, exposure history to the viruses and vaccination history for varicella-zoster virus can help elucidate the diagnosis.

Skin biopsy can help differentiate between these entities and PLEVA or FUMHD. The histopathology of a nonulcerated lesion of FUMHD shows parakeratosis, spongiosis, and lymphocyte exocytosis, as well as lymphocytic vasculitis—findings commonly seen in PLEVA. With the ulceronecrotic lesions of FUMHD, epidermal necrosis and ulceration can be seen microscopically.2 Although skin biopsy is not absolutely necessary for making the diagnosis of PLEVA, it can be helpful.3 However, given the dramatic and extreme clinical impression with an extensive differential diagnosis that includes disorders ranging from infectious to neoplastic, biopsy of FUMHD with clinicopathologic correlation often is required.

It is important to avoid biopsying ulcerated lesions of FUMHD, as the histopathologic findings are more likely to be nonspecific. Additionally, nonspecific features often are seen with immunohistochemistry; abnormal laboratory testing may be seen in FUMHD, but there is no specific test to diagnose FUMHD.2 Finally, a predominantly CD8+ cell infiltrate was seen in 4 of 6 cases of FUMHD, with 2 cases showing a mixed infiltrate of CD8+ and CD4+ cells.5,7-10

Although no unified diagnostic criterion exists for FUMHD, Nofal et al2 proposed criteria comprised of constant features, which are found in every case of FUMHD and can confirm the diagnosis alone, and variable features to help ensure that cases of FUMHD are not missed. The constant features include fever, acute onset of generalized ulceronecrotic papules and plaques, a course that is rapid and progressive (without a tendency for spontaneous resolution), and histopathology that is consistent with PLEVA. The variable features include history of PLEVA, involvement of mucous membranes, and systemic involvement.2

No single unifying treatment modality for all cases of FUMHD has been described. Immunosuppressive drugs (eg, systemic steroids, methotrexate), antibiotics, antivirals, phototherapy, intravenous immunoglobulin, and dapsone have been tried in patients with FUMHD.2 Combination therapy with an oral medication such as erythromycin or methotrexate and psoralen plus UVA may be effective for FUMHD.3 Additionally, some authors believe that patients with FUMHD should be treated similar to burn victims with intensive supportive care.2

The etiology of PLEVA is unknown, but it is presumed to be associated with an effector cytotoxic T-cell response to either an infectious agent or a drug.11

Four cases of FUMHD with monoclonality have been reported,4,7,8 and some researchers propose that FUMHD may be a subset of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.7 However, 2 other cases of FUMHD did not show monoclonality of T cells,5,18 suggesting that FUMHD may represent an inflammatory disorder, rather than a lymphoproliferative process of T cells.18 Given the controversy surrounding the clonality of FUMHD, T-cell gene rearrangement studies were not performed in our case.

To the Editor:

Pityriasis lichenoides is a papulosquamous dermatologic disorder that is characterized by recurrent papules.1 There is a spectrum of disease in pityriasis lichenoides that includes pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA) at one end and pityriasis lichenoides chronica at the other. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta is more common in younger individuals and is characterized by erythematous papules that often crust; these lesions resolve over weeks. The lesions of pityriasis lichenoides chronica are characteristically scaly, pink to red-brown papules that tend to resolve over months.1

Histologically, PLEVA exhibits parakeratosis, interface dermatitis, and a wedge-shaped infiltrate.1 Necrotic keratinocytes and extravasated erythrocytes also are common features. Additionally, monoclonal T cells may be present in the infiltrate.1

Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease (FUMHD) is a rare and severe variant of PLEVA. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease is characterized by ulceronecrotic lesions, fever, and systemic symptoms.2 Herein, we present a case of FUMHD.

A 57-year-old man presented with an eruption of painful lesions involving the face, trunk, arms, legs, and genitalia of 1 month’s duration. The patient denied oral and ocular involvement. He had soreness and swelling of the arms and legs. A prior 12-day course of prednisone prescribed by a community dermatologist failed to improve the rash. A biopsy performed by a community dermatologist was nondiagnostic. The patient denied fever but did report chills. He had no preceding illness and was not taking new medications. On physical examination, the patient was afebrile and normotensive with innumerable deep-seated pustules and crusted ulcerations on the face, palms, soles, trunk, extremities, and penis (Figures 1 and 2). There was a background morbilliform eruption on the trunk. The ocular and oral mucosae were spared. The upper and lower extremities had pitting edema.

The patient’s alanine aminotransaminase and aspartate aminotransaminase levels were elevated at 55 and 51 U/L, respectively. His white blood cell count was within reference range; however, there was an elevated absolute neutrophil count (8.7×103/μL). No eosinophilia was noted. Laboratory evaluation showed a positive antimitochondrial antibody, and magnetic resonance imaging showed evidence of steatohepatitis. Punch biopsies from both the morbilliform eruption and a deep-seated pustule showed epidermal necrosis, parakeratosis, necrotic keratinocytes, and a lichenoid infiltrate of lymphocytes at the dermoepidermal interface. In the dermis, there was a wedge-shaped superficial and deep, perivascular infiltrate with extravasated erythrocytes (Figures 3 and 4). Tissue Gram stain was negative for bacteria. Varicella-zoster virus and herpes simplex virus immunostains were negative. Direct immunofluorescence showed colloid bodies, as can be seen in lichenoid dermatitis.

At the next clinic visit, the patient reported a fever of 39.4 °C. After reviewing the patient’s histopathology and clinical picture, along with the presence of fever, a final diagnosis of FUMHD was made. The patient was started on an oral regimen of prednisone 80 mg once daily, minocycline 100 mg twice daily, and methotrexate 15 mg weekly. Unna boots (specialized compression wraps) with triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% were placed weekly until the leg edema and ulcerations healed. He was maintained on methotrexate 15 mg weekly and 5 to 10 mg of prednisone once daily. The patient demonstrated residual scarring, with only rare new papulonodules that did not ulcerate when attempts were made to taper his medications. He was followed for nearly 3 years, with a recurrence of symptoms 2 years and 3 months after initial presentation to the academic dermatology clinic.

Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease is a rare and severe variant of PLEVA that can present with the rapid appearance of necrotic skin lesions, fever, and systemic manifestations, including pulmonary, gastrointestinal, central nervous system, cardiac, hematologic, and rheumatologic symptoms.2-4 The evolution from PLEVA to FUMHD ranges from days to weeks, and patientsrarely can have an initial presentation of FUMHD.2 The duration of illness has been reported to be 1 to 24 months5; however, the length of illness still remains unclear, as many studies of FUMHD are case reports with limited follow-up. Our patient had a disease duration of at least 27 months. The lesions of FUMHD usually are generalized with flexural prominence, and mucosal involvement occurs in approximately one-quarter of cases. Hypertrophic scarring may be seen after the ulcerated lesions heal.2 The incidence of FUMHD is higher in men than in women, and it is more common in younger individuals.2,6 There have been reported fatalities associated with FUMHD, mostly in adults.2,4

The clinical differential diagnosis for PLEVA includes disseminated herpes zoster, varicella-zoster virus or coxsackievirus infections, lymphomatoid papulosis, angiodestructive lymphoma such as extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma, drug eruption, arthropod bite, erythema multiforme, ecthyma, ecthyma gangrenosum, necrotic folliculitis, and cutaneous small vessel vasculitis. To differentiate between these diagnoses and PLEVA or FUMHD, it is important to take a strong clinical history. For example, for varicella-zoster virus and coxsackievirus infections, exposure history to the viruses and vaccination history for varicella-zoster virus can help elucidate the diagnosis.

Skin biopsy can help differentiate between these entities and PLEVA or FUMHD. The histopathology of a nonulcerated lesion of FUMHD shows parakeratosis, spongiosis, and lymphocyte exocytosis, as well as lymphocytic vasculitis—findings commonly seen in PLEVA. With the ulceronecrotic lesions of FUMHD, epidermal necrosis and ulceration can be seen microscopically.2 Although skin biopsy is not absolutely necessary for making the diagnosis of PLEVA, it can be helpful.3 However, given the dramatic and extreme clinical impression with an extensive differential diagnosis that includes disorders ranging from infectious to neoplastic, biopsy of FUMHD with clinicopathologic correlation often is required.

It is important to avoid biopsying ulcerated lesions of FUMHD, as the histopathologic findings are more likely to be nonspecific. Additionally, nonspecific features often are seen with immunohistochemistry; abnormal laboratory testing may be seen in FUMHD, but there is no specific test to diagnose FUMHD.2 Finally, a predominantly CD8+ cell infiltrate was seen in 4 of 6 cases of FUMHD, with 2 cases showing a mixed infiltrate of CD8+ and CD4+ cells.5,7-10

Although no unified diagnostic criterion exists for FUMHD, Nofal et al2 proposed criteria comprised of constant features, which are found in every case of FUMHD and can confirm the diagnosis alone, and variable features to help ensure that cases of FUMHD are not missed. The constant features include fever, acute onset of generalized ulceronecrotic papules and plaques, a course that is rapid and progressive (without a tendency for spontaneous resolution), and histopathology that is consistent with PLEVA. The variable features include history of PLEVA, involvement of mucous membranes, and systemic involvement.2

No single unifying treatment modality for all cases of FUMHD has been described. Immunosuppressive drugs (eg, systemic steroids, methotrexate), antibiotics, antivirals, phototherapy, intravenous immunoglobulin, and dapsone have been tried in patients with FUMHD.2 Combination therapy with an oral medication such as erythromycin or methotrexate and psoralen plus UVA may be effective for FUMHD.3 Additionally, some authors believe that patients with FUMHD should be treated similar to burn victims with intensive supportive care.2

The etiology of PLEVA is unknown, but it is presumed to be associated with an effector cytotoxic T-cell response to either an infectious agent or a drug.11

Four cases of FUMHD with monoclonality have been reported,4,7,8 and some researchers propose that FUMHD may be a subset of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.7 However, 2 other cases of FUMHD did not show monoclonality of T cells,5,18 suggesting that FUMHD may represent an inflammatory disorder, rather than a lymphoproliferative process of T cells.18 Given the controversy surrounding the clonality of FUMHD, T-cell gene rearrangement studies were not performed in our case.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al. Other papulosquamous disorders. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al, eds. Dermatology Essentials. Elsevier Saunders; 2014:68-69.

- Nofal A, Assaf M, Alakad R, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease: proposed diagnostic criteria and therapeutic evaluation. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:729-738.

- Milligan A, Johnston GA. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta. In: Lebwohl MG, Heymann WR, Berth-Jones J, et al, eds. Treatment of Skin Disease, Comprehensive Therapeutic Strategies. 4th ed. Saunders; 2013:580-582.

- Miyamoto T, Takayama N, Kitada S, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease: a case report and a review of the literature. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:795-797.

- Meziane L, Caudron A, Dhaille F, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease: treatment with infliximab and intravenous immunoglobulins and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2012;225:344-348.

- Robinson AB, Stein LD. Miscellaneous conditions associated with arthritis. In: Kliegman RM, Stanton BF, St. Geme JW III, et al, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 19th ed. W.B. Saunders Company; 2011:880.

- Cozzio A, Hafner J, Kempf W, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease with clonality: a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma entity? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:1014-1017.

- Tsianakas A, Hoeger PH. Transition of pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta to febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease is associated with elevated serum tumour necrosis factor-alpha. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:794-799.

- Yanaba K, Ito M, Sasaki H, et al. A case of febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease requiring debridement of necrotic skin and epidermal autograft. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:1249-1253.

- Lode HN, Döring P, Lauenstein P, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease following suspected hemorrhagic chickenpox infection in a 20-month-old boy. Infection. 2015;43:583-588.

- Tomasini D, Tomasini CF, Cerri A, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides: a cytotoxic T-cell-mediated skin disorder: evidence of human parvovirus B19 DNA in nine cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:531-538.

- Weiss LM, Wood GS, Ellisen LW, et al. Clonal T-cell populations in pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (Mucha-Habermann disease). Am J Pathol. 1987;126:417-421.

- Dereure O, Levi E, Kadin ME. T-cell clonality in pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta: a heteroduplex analysis of 20 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1483-1486.

- Weinberg JM, Kristal L, Chooback L, et al. The clonal nature of pityriasis lichenoides. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1063-1067.

- Fortson JS, Schroeter AL, Esterly NB. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (parapsoriasis en plaque): an association with pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta in young children. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:1449-1453.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al, eds. Dermatology Essentials. Elsevier Saunders; 2014:958.

- Kim JE, Yun WJ, Mun SK, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta and pityriasis lichenoides chronica: comparison of lesional T-cell subsets and investigation of viral associations. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:649-656.

- López-Estebaran´z JL, Vanaclocha F, Gil R, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29(5, pt 2):903-906.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al. Other papulosquamous disorders. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al, eds. Dermatology Essentials. Elsevier Saunders; 2014:68-69.

- Nofal A, Assaf M, Alakad R, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease: proposed diagnostic criteria and therapeutic evaluation. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:729-738.

- Milligan A, Johnston GA. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta. In: Lebwohl MG, Heymann WR, Berth-Jones J, et al, eds. Treatment of Skin Disease, Comprehensive Therapeutic Strategies. 4th ed. Saunders; 2013:580-582.

- Miyamoto T, Takayama N, Kitada S, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease: a case report and a review of the literature. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:795-797.

- Meziane L, Caudron A, Dhaille F, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease: treatment with infliximab and intravenous immunoglobulins and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2012;225:344-348.

- Robinson AB, Stein LD. Miscellaneous conditions associated with arthritis. In: Kliegman RM, Stanton BF, St. Geme JW III, et al, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 19th ed. W.B. Saunders Company; 2011:880.

- Cozzio A, Hafner J, Kempf W, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease with clonality: a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma entity? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:1014-1017.

- Tsianakas A, Hoeger PH. Transition of pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta to febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease is associated with elevated serum tumour necrosis factor-alpha. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:794-799.

- Yanaba K, Ito M, Sasaki H, et al. A case of febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease requiring debridement of necrotic skin and epidermal autograft. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:1249-1253.

- Lode HN, Döring P, Lauenstein P, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease following suspected hemorrhagic chickenpox infection in a 20-month-old boy. Infection. 2015;43:583-588.

- Tomasini D, Tomasini CF, Cerri A, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides: a cytotoxic T-cell-mediated skin disorder: evidence of human parvovirus B19 DNA in nine cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:531-538.

- Weiss LM, Wood GS, Ellisen LW, et al. Clonal T-cell populations in pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (Mucha-Habermann disease). Am J Pathol. 1987;126:417-421.

- Dereure O, Levi E, Kadin ME. T-cell clonality in pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta: a heteroduplex analysis of 20 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1483-1486.

- Weinberg JM, Kristal L, Chooback L, et al. The clonal nature of pityriasis lichenoides. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1063-1067.

- Fortson JS, Schroeter AL, Esterly NB. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (parapsoriasis en plaque): an association with pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta in young children. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:1449-1453.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al, eds. Dermatology Essentials. Elsevier Saunders; 2014:958.

- Kim JE, Yun WJ, Mun SK, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta and pityriasis lichenoides chronica: comparison of lesional T-cell subsets and investigation of viral associations. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:649-656.

- López-Estebaran´z JL, Vanaclocha F, Gil R, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29(5, pt 2):903-906.

Practice Points

- Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease (FUMHD) is a rare variant of pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta, characterized by ulceronecrotic lesions, fever, and systemic symptoms.

- A variety of treatments including immunosuppressive drugs (eg, systemic steroids, methotrexate), antibiotics, antivirals, phototherapy, intravenous immunoglobulin, and dapsone have been used in patients with FUMHD.

Tender White Lesions on the Groin

The Diagnosis: Candidal Intertrigo

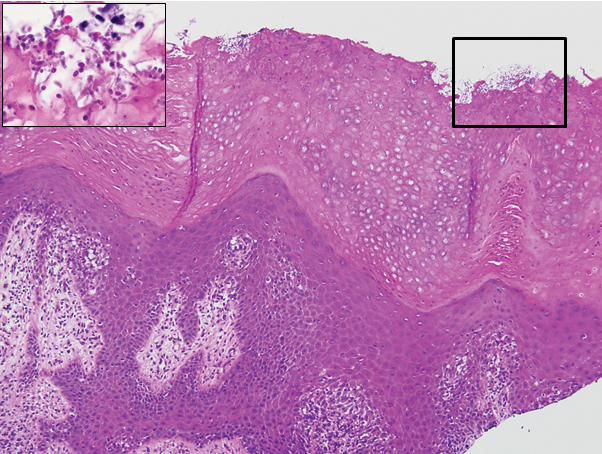

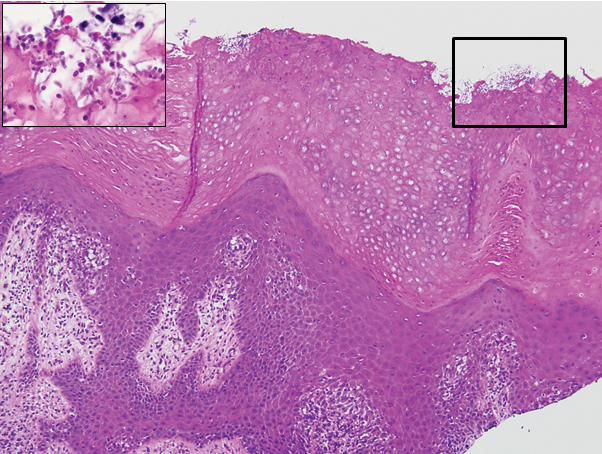

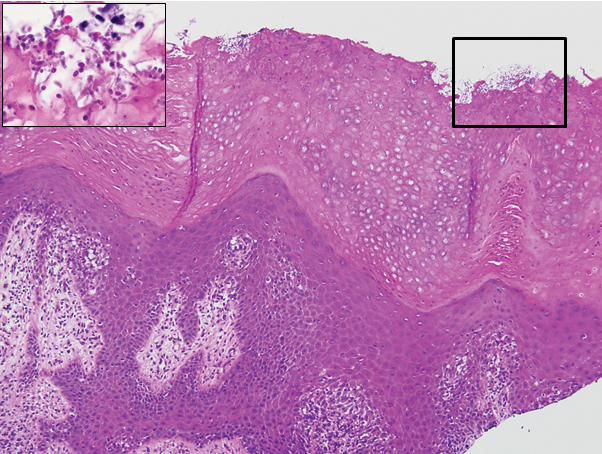

The biopsy confirmed a diagnosis of severe hyperkeratotic candidal intertrigo with no evidence of Hailey-Hailey disease. Hematoxylin and eosin- stained sections demonstrated irregular acanthosis and variable spongiosis. The stratum corneum was predominantly orthokeratotic with overlying psuedohyphae and yeast fungal elements (Figure 1).

Hyperimmunoglobulinemia E syndrome (HIES), also known as hyper-IgE syndrome or Job syndrome, is a rare immunodeficiency disorder characterized by an eczematous dermatitis-like rash, recurrent skin and lung abscesses, eosinophilia, and elevated serum IgE. Facial asymmetry, prominent forehead, deep-set eyes, broad nose, and roughened facial skin with large pores are characteristic of the sporadic and autosomal-recessive forms. Other common findings include retained primary teeth, hyperextensible joints, and recurrent mucocutaneous candidiasis.1

Although autosomal-dominant and autosomal-recessive inheritance patterns exist, sporadic mutations are the most common cause of HIES.2 Several genes have been implicated depending on the inheritance pattern. The majority of autosomal-dominant cases are associated with inactivating STAT3 (signal transducer and activator of transcription 3) mutations, whereas the majority of autosomal-recessive cases are associated with inactivating DOCK8 (dedicator of cytokinesis 8) mutations.1 Ultimately, all of these mutations lead to an impaired helper T cell (TH17) response, which is crucial for clearing fungal and extracellular bacterial infections.3

Skin eruptions typically are the first manifestation of HIES; they appear within the first week to month of life as papulopustular eruptions on the face and scalp and rapidly generalize to the rest of the body, favoring the shoulders, arms, chest, and buttocks. The pustules then coalesce into crusted plaques that resemble atopic dermatitis, frequently with superimposed Staphylococcus aureus infection. On microscopy, the pustules are folliculocentric and often contain eosinophils, whereas the plaques may contain intraepidermal collections of eosinophils.1

Mucocutaneous candidiasis is seen in approximately 60% of HIES cases and is closely linked to STAT3 inactivating mutations.3 Histologically, there is marked acanthosis with neutrophil exocytosis and abundant yeast and pseudohyphal forms within the stratum corneum (Figure 2).4 Cutaneous candidal infections typically require both oral and topical antifungal agents to clear the infection.3 Most cases of mucocutaneous candidiasis are caused by Candida albicans; however, other known culprits include Candida glabrata, Candida tropicalis, Candida parapsilosis, and Candida krusei.5,6 Of note, species identification and antifungal susceptibility studies may be useful in refractory cases, especially with C glabrata, which is known to acquire resistance to azoles, such as fluconazole, with emerging resistance to echinocandins.6

The differential diagnosis of this groin eruption included Hailey-Hailey disease; pemphigus vegetans, Hallopeau type; tinea cruris; and inverse psoriasis. Hailey-Hailey disease can be complicated by a superimposed candidal infection with similar clinical features, and biopsy may be required for definitive diagnosis. Hailey-Hailey disease typically presents with macerated fissured plaques that resemble macerated tissue paper with red fissures (Figure 3). Biopsy confirms full-thickness acantholysis resembling a dilapidated brick wall with minimal dyskeratosis.1 Pemphigus vegetans is a localized variant of pemphigus vulgaris with a predilection for flexural surfaces. The lesions progress to vegetating erosive plaques.4 The Hallopeau type often is studded with pustules and typically remains more localized than the Neumann type. Direct immunofluorescence demonstrates intercellular deposition of IgG and C3, and routine sections characteristically show pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal eosinophilic microabscesses.1,4 Tinea cruris is characterized by erythematous annular lesions with raised scaly borders spreading down the inner thighs.7 The epidermis is variably spongiotic with parakeratosis, and neutrophils often present in a layered stratum corneum with basketweave keratin above a layer of more compact and eosinophilic keratin. Fungal stains, such as periodic acid-Schiff, will highlight the fungal hyphae within the stratum corneum. The inguinal folds are a typical location for inverse psoriasis, which generally appears as thin, sharply demarcated, shiny red plaques with less scale than plaque psoriasis.1 Psoriasiform hyperplasia with a diminished granular layer and tortuous papillary dermal vessels would be expected histologically.1

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016.

- Schwartz RA, Tarlow MM. Dermatologic manifestations of Job syndrome. Medscape website. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1050852-overview. Updated April 22, 2019. Accessed March 28, 2020.

- Minegishi Y, Saito M. Cutaneous manifestations of hyper IgE syndrome. Allergol Int. 2012;61:191-196.

- Patterson JW. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2016.

- Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, et al. Executive summary: clinical practice guideline for the management of candidiasis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:409-417.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Antifungal resistance. https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/antifungal-resistance.html. Updated March 17, 2020. Accessed April 20, 2020.

- Tinea cruris. DermNet NZ website. https://www.dermnetnz.org/topics/tinea-cruris/. Published 2003. Accessed March 28, 2020.

The Diagnosis: Candidal Intertrigo

The biopsy confirmed a diagnosis of severe hyperkeratotic candidal intertrigo with no evidence of Hailey-Hailey disease. Hematoxylin and eosin- stained sections demonstrated irregular acanthosis and variable spongiosis. The stratum corneum was predominantly orthokeratotic with overlying psuedohyphae and yeast fungal elements (Figure 1).

Hyperimmunoglobulinemia E syndrome (HIES), also known as hyper-IgE syndrome or Job syndrome, is a rare immunodeficiency disorder characterized by an eczematous dermatitis-like rash, recurrent skin and lung abscesses, eosinophilia, and elevated serum IgE. Facial asymmetry, prominent forehead, deep-set eyes, broad nose, and roughened facial skin with large pores are characteristic of the sporadic and autosomal-recessive forms. Other common findings include retained primary teeth, hyperextensible joints, and recurrent mucocutaneous candidiasis.1

Although autosomal-dominant and autosomal-recessive inheritance patterns exist, sporadic mutations are the most common cause of HIES.2 Several genes have been implicated depending on the inheritance pattern. The majority of autosomal-dominant cases are associated with inactivating STAT3 (signal transducer and activator of transcription 3) mutations, whereas the majority of autosomal-recessive cases are associated with inactivating DOCK8 (dedicator of cytokinesis 8) mutations.1 Ultimately, all of these mutations lead to an impaired helper T cell (TH17) response, which is crucial for clearing fungal and extracellular bacterial infections.3

Skin eruptions typically are the first manifestation of HIES; they appear within the first week to month of life as papulopustular eruptions on the face and scalp and rapidly generalize to the rest of the body, favoring the shoulders, arms, chest, and buttocks. The pustules then coalesce into crusted plaques that resemble atopic dermatitis, frequently with superimposed Staphylococcus aureus infection. On microscopy, the pustules are folliculocentric and often contain eosinophils, whereas the plaques may contain intraepidermal collections of eosinophils.1

Mucocutaneous candidiasis is seen in approximately 60% of HIES cases and is closely linked to STAT3 inactivating mutations.3 Histologically, there is marked acanthosis with neutrophil exocytosis and abundant yeast and pseudohyphal forms within the stratum corneum (Figure 2).4 Cutaneous candidal infections typically require both oral and topical antifungal agents to clear the infection.3 Most cases of mucocutaneous candidiasis are caused by Candida albicans; however, other known culprits include Candida glabrata, Candida tropicalis, Candida parapsilosis, and Candida krusei.5,6 Of note, species identification and antifungal susceptibility studies may be useful in refractory cases, especially with C glabrata, which is known to acquire resistance to azoles, such as fluconazole, with emerging resistance to echinocandins.6

The differential diagnosis of this groin eruption included Hailey-Hailey disease; pemphigus vegetans, Hallopeau type; tinea cruris; and inverse psoriasis. Hailey-Hailey disease can be complicated by a superimposed candidal infection with similar clinical features, and biopsy may be required for definitive diagnosis. Hailey-Hailey disease typically presents with macerated fissured plaques that resemble macerated tissue paper with red fissures (Figure 3). Biopsy confirms full-thickness acantholysis resembling a dilapidated brick wall with minimal dyskeratosis.1 Pemphigus vegetans is a localized variant of pemphigus vulgaris with a predilection for flexural surfaces. The lesions progress to vegetating erosive plaques.4 The Hallopeau type often is studded with pustules and typically remains more localized than the Neumann type. Direct immunofluorescence demonstrates intercellular deposition of IgG and C3, and routine sections characteristically show pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal eosinophilic microabscesses.1,4 Tinea cruris is characterized by erythematous annular lesions with raised scaly borders spreading down the inner thighs.7 The epidermis is variably spongiotic with parakeratosis, and neutrophils often present in a layered stratum corneum with basketweave keratin above a layer of more compact and eosinophilic keratin. Fungal stains, such as periodic acid-Schiff, will highlight the fungal hyphae within the stratum corneum. The inguinal folds are a typical location for inverse psoriasis, which generally appears as thin, sharply demarcated, shiny red plaques with less scale than plaque psoriasis.1 Psoriasiform hyperplasia with a diminished granular layer and tortuous papillary dermal vessels would be expected histologically.1

The Diagnosis: Candidal Intertrigo

The biopsy confirmed a diagnosis of severe hyperkeratotic candidal intertrigo with no evidence of Hailey-Hailey disease. Hematoxylin and eosin- stained sections demonstrated irregular acanthosis and variable spongiosis. The stratum corneum was predominantly orthokeratotic with overlying psuedohyphae and yeast fungal elements (Figure 1).

Hyperimmunoglobulinemia E syndrome (HIES), also known as hyper-IgE syndrome or Job syndrome, is a rare immunodeficiency disorder characterized by an eczematous dermatitis-like rash, recurrent skin and lung abscesses, eosinophilia, and elevated serum IgE. Facial asymmetry, prominent forehead, deep-set eyes, broad nose, and roughened facial skin with large pores are characteristic of the sporadic and autosomal-recessive forms. Other common findings include retained primary teeth, hyperextensible joints, and recurrent mucocutaneous candidiasis.1

Although autosomal-dominant and autosomal-recessive inheritance patterns exist, sporadic mutations are the most common cause of HIES.2 Several genes have been implicated depending on the inheritance pattern. The majority of autosomal-dominant cases are associated with inactivating STAT3 (signal transducer and activator of transcription 3) mutations, whereas the majority of autosomal-recessive cases are associated with inactivating DOCK8 (dedicator of cytokinesis 8) mutations.1 Ultimately, all of these mutations lead to an impaired helper T cell (TH17) response, which is crucial for clearing fungal and extracellular bacterial infections.3

Skin eruptions typically are the first manifestation of HIES; they appear within the first week to month of life as papulopustular eruptions on the face and scalp and rapidly generalize to the rest of the body, favoring the shoulders, arms, chest, and buttocks. The pustules then coalesce into crusted plaques that resemble atopic dermatitis, frequently with superimposed Staphylococcus aureus infection. On microscopy, the pustules are folliculocentric and often contain eosinophils, whereas the plaques may contain intraepidermal collections of eosinophils.1

Mucocutaneous candidiasis is seen in approximately 60% of HIES cases and is closely linked to STAT3 inactivating mutations.3 Histologically, there is marked acanthosis with neutrophil exocytosis and abundant yeast and pseudohyphal forms within the stratum corneum (Figure 2).4 Cutaneous candidal infections typically require both oral and topical antifungal agents to clear the infection.3 Most cases of mucocutaneous candidiasis are caused by Candida albicans; however, other known culprits include Candida glabrata, Candida tropicalis, Candida parapsilosis, and Candida krusei.5,6 Of note, species identification and antifungal susceptibility studies may be useful in refractory cases, especially with C glabrata, which is known to acquire resistance to azoles, such as fluconazole, with emerging resistance to echinocandins.6

The differential diagnosis of this groin eruption included Hailey-Hailey disease; pemphigus vegetans, Hallopeau type; tinea cruris; and inverse psoriasis. Hailey-Hailey disease can be complicated by a superimposed candidal infection with similar clinical features, and biopsy may be required for definitive diagnosis. Hailey-Hailey disease typically presents with macerated fissured plaques that resemble macerated tissue paper with red fissures (Figure 3). Biopsy confirms full-thickness acantholysis resembling a dilapidated brick wall with minimal dyskeratosis.1 Pemphigus vegetans is a localized variant of pemphigus vulgaris with a predilection for flexural surfaces. The lesions progress to vegetating erosive plaques.4 The Hallopeau type often is studded with pustules and typically remains more localized than the Neumann type. Direct immunofluorescence demonstrates intercellular deposition of IgG and C3, and routine sections characteristically show pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal eosinophilic microabscesses.1,4 Tinea cruris is characterized by erythematous annular lesions with raised scaly borders spreading down the inner thighs.7 The epidermis is variably spongiotic with parakeratosis, and neutrophils often present in a layered stratum corneum with basketweave keratin above a layer of more compact and eosinophilic keratin. Fungal stains, such as periodic acid-Schiff, will highlight the fungal hyphae within the stratum corneum. The inguinal folds are a typical location for inverse psoriasis, which generally appears as thin, sharply demarcated, shiny red plaques with less scale than plaque psoriasis.1 Psoriasiform hyperplasia with a diminished granular layer and tortuous papillary dermal vessels would be expected histologically.1

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016.

- Schwartz RA, Tarlow MM. Dermatologic manifestations of Job syndrome. Medscape website. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1050852-overview. Updated April 22, 2019. Accessed March 28, 2020.

- Minegishi Y, Saito M. Cutaneous manifestations of hyper IgE syndrome. Allergol Int. 2012;61:191-196.

- Patterson JW. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2016.

- Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, et al. Executive summary: clinical practice guideline for the management of candidiasis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:409-417.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Antifungal resistance. https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/antifungal-resistance.html. Updated March 17, 2020. Accessed April 20, 2020.

- Tinea cruris. DermNet NZ website. https://www.dermnetnz.org/topics/tinea-cruris/. Published 2003. Accessed March 28, 2020.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016.

- Schwartz RA, Tarlow MM. Dermatologic manifestations of Job syndrome. Medscape website. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1050852-overview. Updated April 22, 2019. Accessed March 28, 2020.

- Minegishi Y, Saito M. Cutaneous manifestations of hyper IgE syndrome. Allergol Int. 2012;61:191-196.

- Patterson JW. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2016.

- Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, et al. Executive summary: clinical practice guideline for the management of candidiasis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:409-417.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Antifungal resistance. https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/antifungal-resistance.html. Updated March 17, 2020. Accessed April 20, 2020.

- Tinea cruris. DermNet NZ website. https://www.dermnetnz.org/topics/tinea-cruris/. Published 2003. Accessed March 28, 2020.

A 28-year-old man with a history of hyperimmunoglobulinemia E syndrome (previously known as Job syndrome), coarse facial features, and multiple skin and soft tissue infections presented to the university dermatology clinic with persistent white, macerated, fissured groin plaques that were present for months. The lesions were tender and pruritic with a burning sensation. Treatment with topical terbinafine and oral fluconazole was attempted without resolution of the eruption. A biopsy of the groin lesion was performed.