User login

From sweet to belligerent in the blink of an eye

CASE Combative and agitated

Ms. P, age 87, presents to the emergency department (ED) with her caregiver, who says Ms. P has new-onset altered mental status, agitation, and combativeness.

Ms. P resides at a long-term care (LTC) facility, where according to the nurses she normally is pleasant, well-oriented, and cooperative. Ms. P’s medical history includes major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, hypertension, chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage III, peptic ulcer disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease, coronary artery disease with 2 past myocardial infarctions requiring stents, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hyperlipidemia, bradycardia requiring a pacemaker, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, asthma, aortic stenosis, peripheral vascular disease, esophageal stricture requiring dilation, deep vein thrombosis, and migraines.

Mr. P’s medication list includes acetaminophen, 650 mg every 6 hours; ipratropium/albuterol nebulized solution, 3 mL 4 times a day; aspirin, 81 mg/d; atorvastatin, 40 mg/d; calcitonin, 1 spray nasally at bedtime; clopidogrel, 75 mg/d; ezetimibe, 10 mg/d; fluoxetine, 20 mg/d; furosemide, 20 mg/d; isosorbide dinitrate, 120 mg/d; lisinopril, 15 mg/d; risperidone, 0.5 mg/d; magnesium oxide, 800 mg/d; pantoprazole, 40 mg/d; polyethylene glycol, 17 g/d; sotalol, 160 mg/d; olanzapine, 5 mg IM every 6 hours as needed for agitation; and tramadol, 50 mg every 8 hours as needed for headache.

Seven days before coming to the ED, Ms. P was started on ceftriaxone, 1 g/d, for suspected community-acquired pneumonia. At that time, the nursing staff noticed behavioral changes. Soon after, Ms. P began refusing all her medications. Two days before presenting to the ED, Ms. P was started on nitrofurantoin, 200 mg/d, for a suspected urinary tract infection, but it was discontinued because of an allergy.

Her caregiver reports that while at the LTC facility, Ms. P’s behavioral changes worsened. Ms. P claimed to be Jesus Christ and said she was talking to the devil; she chased other residents around the facility and slapped medications away from the nursing staff. According to caregivers, this behavior was out of character.

Shortly after arriving in the ED, Ms. P is admitted to the psychiatric unit.

[polldaddy:10332748]

The authors’ observations

Delirium is a complex, acute alteration in a patient’s mental status compared with his/her baseline functioning1 (Table 12). The onset of delirium is quick, happening within hours to days, with fluctuations in mental function. Patients might present with hyperactive, hypoactive, or mixed delirium.3 Patients with hyperactive delirium often have delusions and hallucinations; these patients might be agitated and could become violent with family and caregivers.3 Patients with hypoactive delirium are less likely to experience hallucinations and more likely to show symptoms of sedation.3 Patients with hypoactive delirium can be difficult to diagnose because it is challenging to interview them and understand what might be the cause of their sedated state. Patients also can exhibit a mixed delirium in which they fluctuate between periods of hyperactivity and hypoactivity.3

Continue to: Suspected delirium...

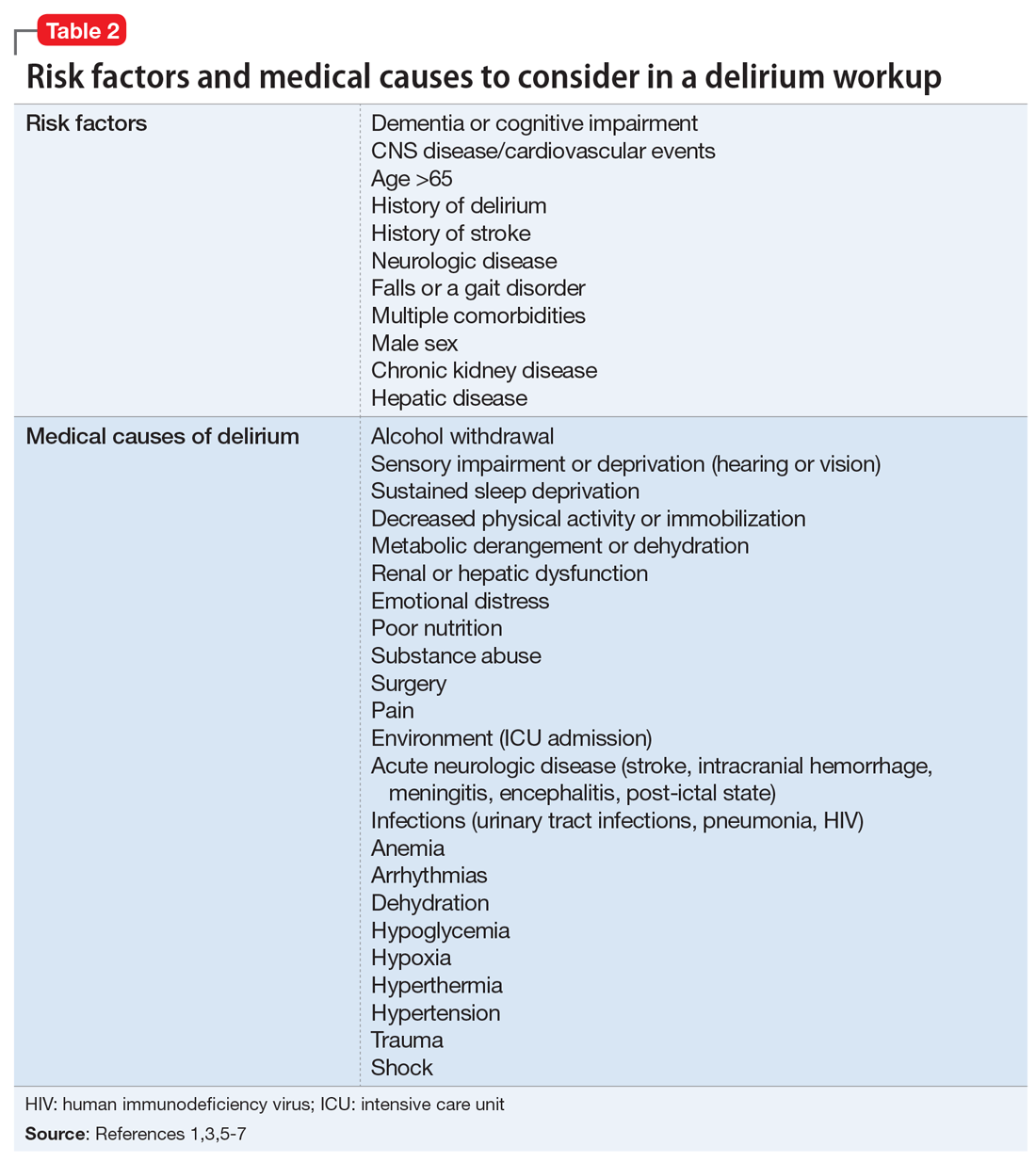

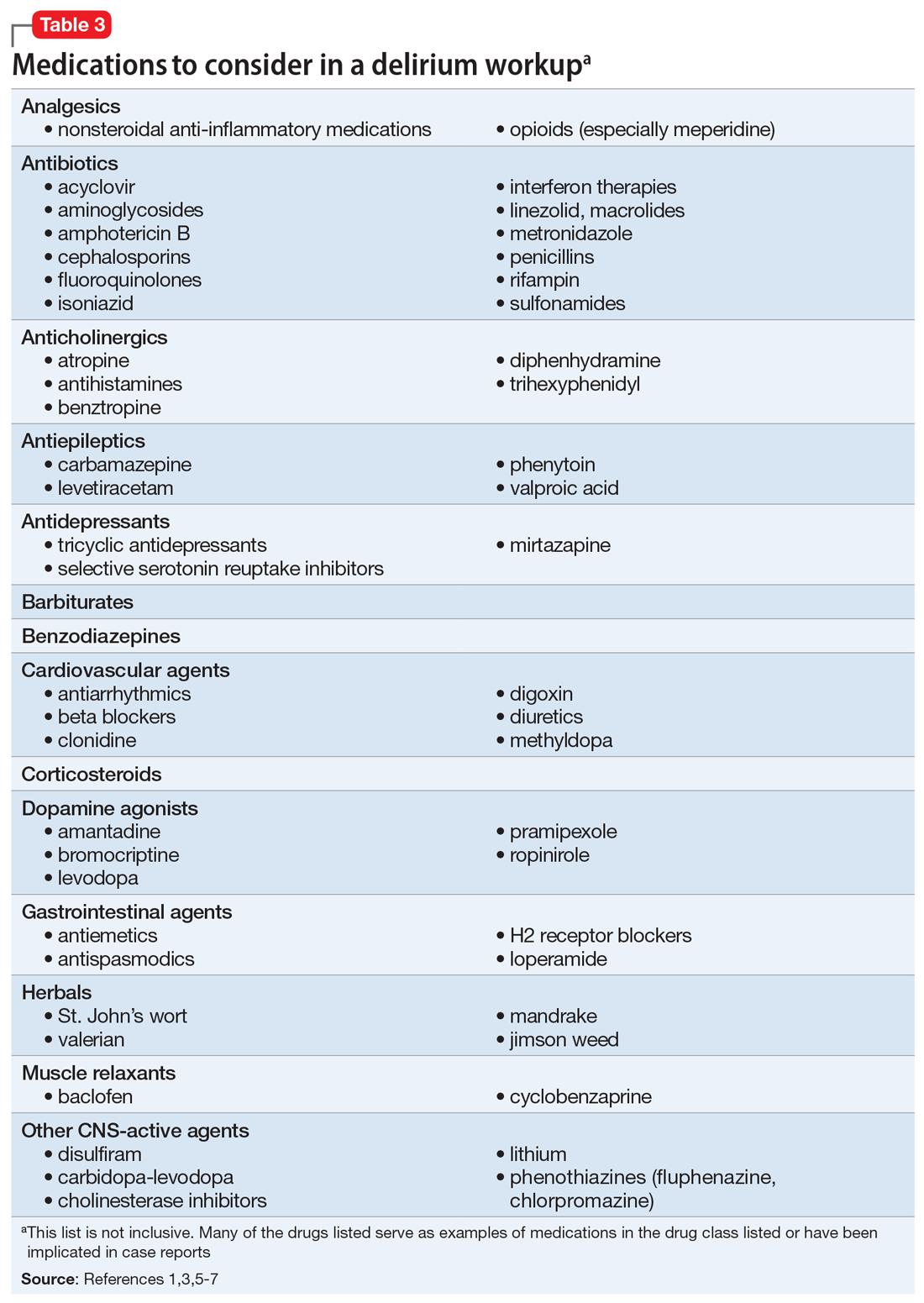

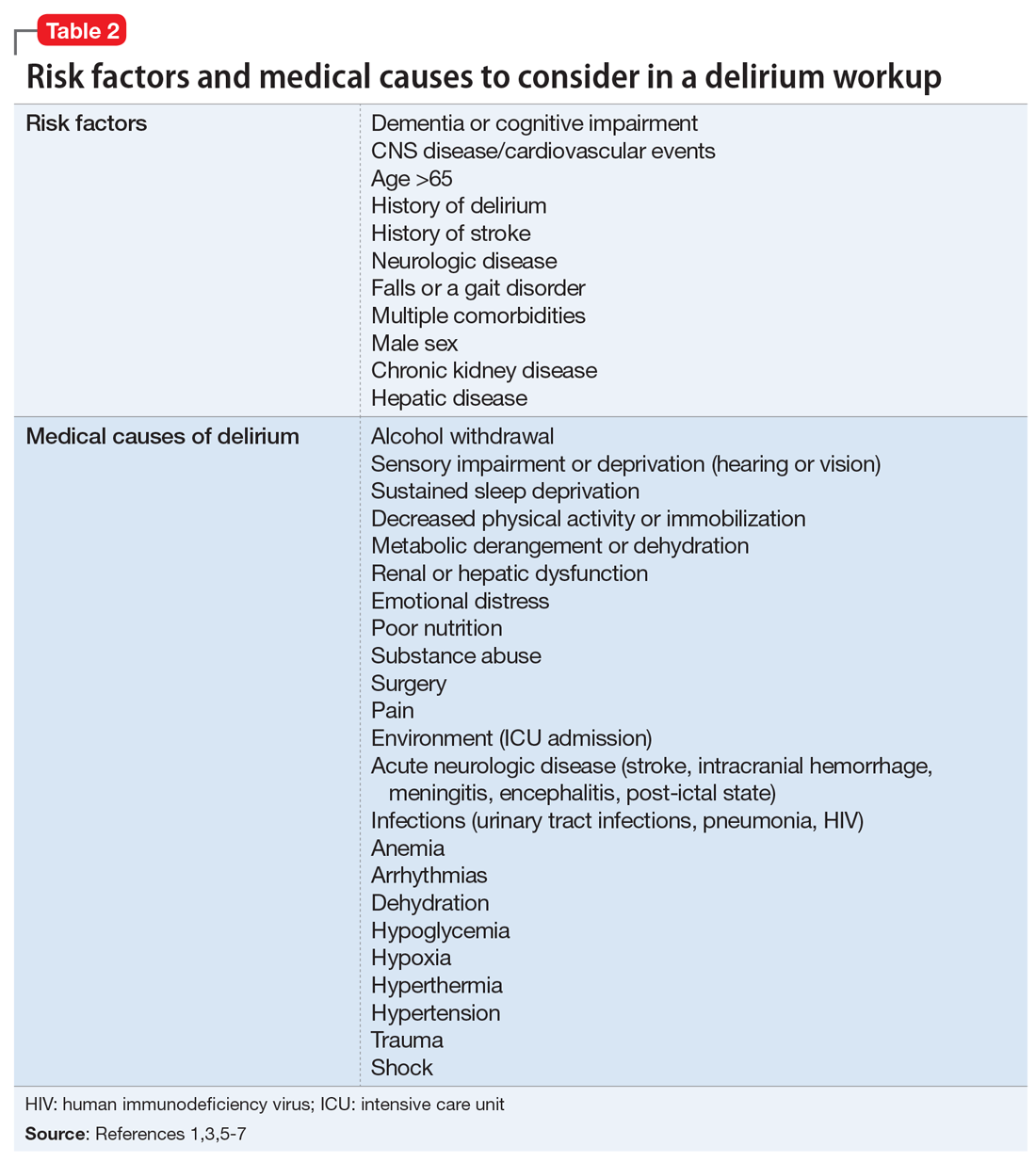

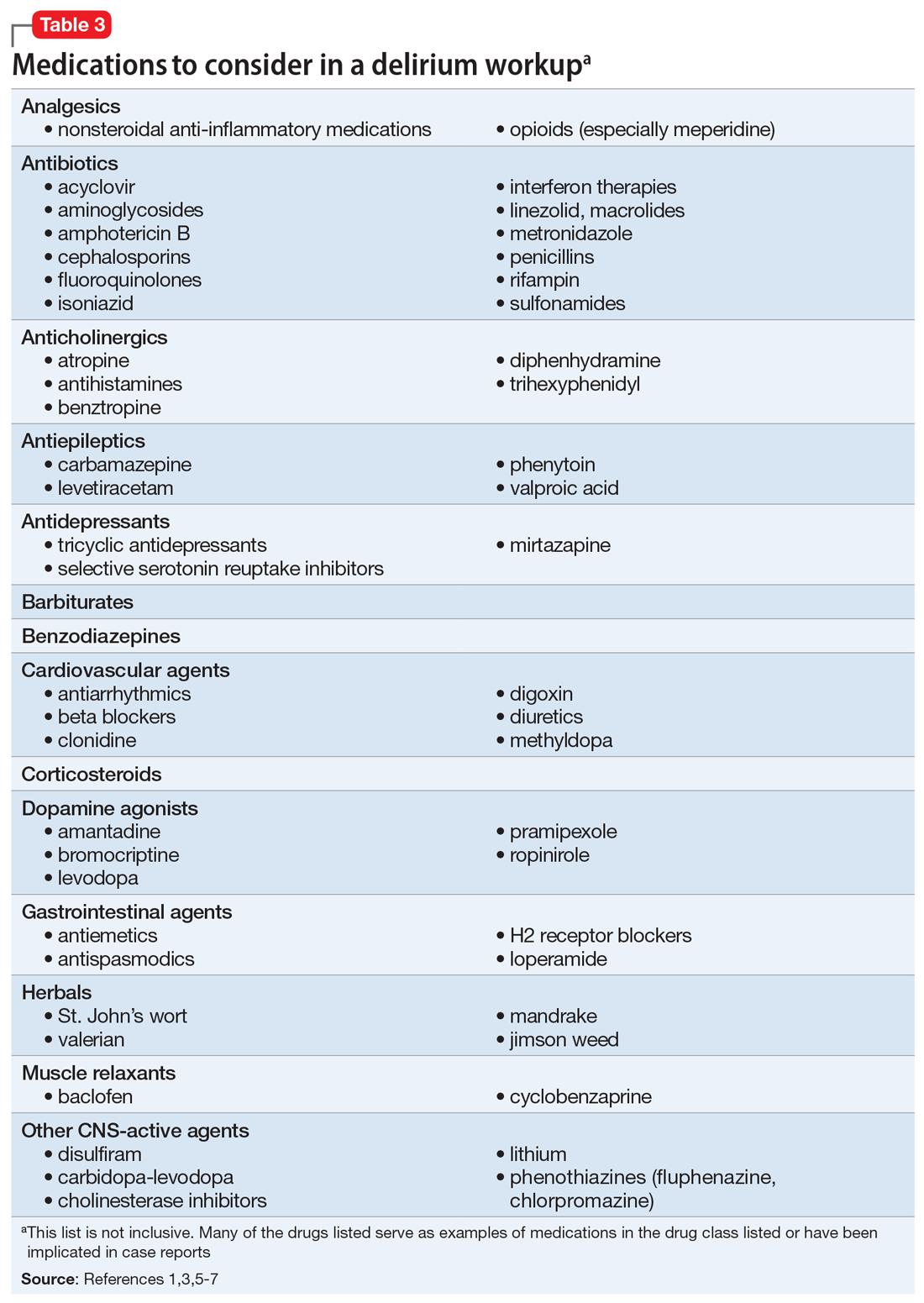

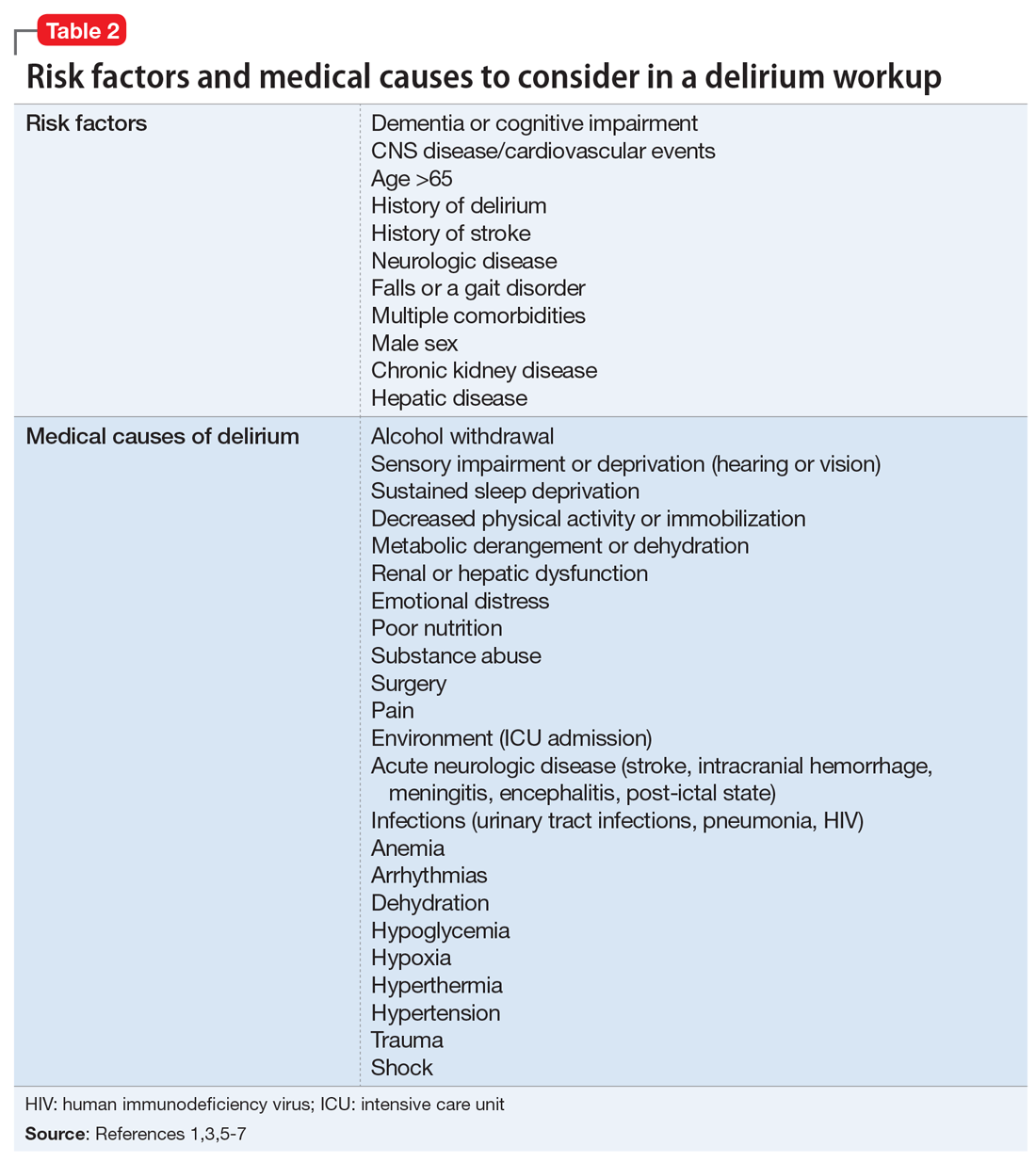

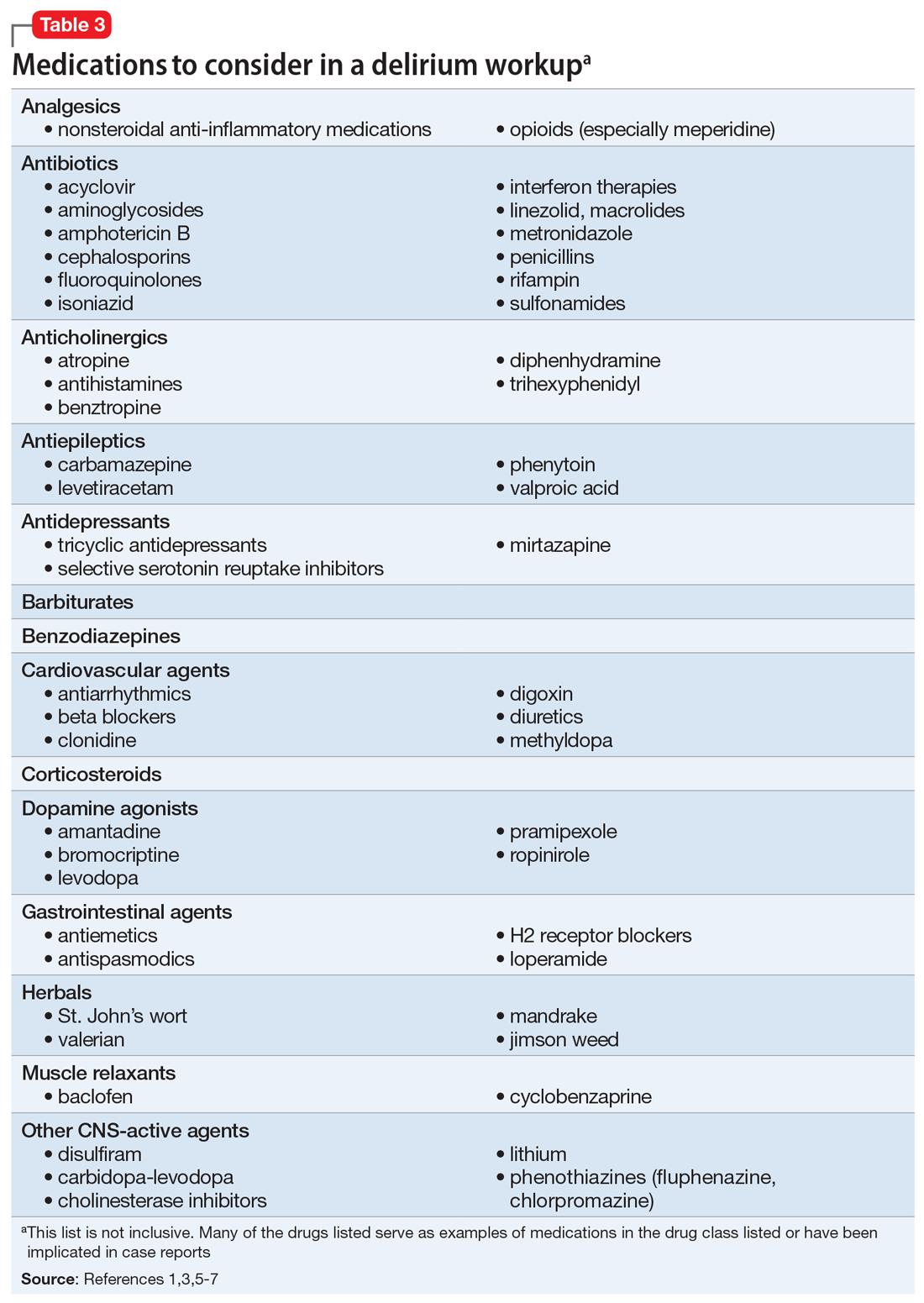

Suspected delirium should be considered a medical emergency because the outcome could be fatal.1 It is important to uncover and treat the underlying cause(s) of delirium rather than solely administering antipsychotics, which might mask the presenting symptoms. In an older study, Francis and Kapoor4 reported that 56% of geriatric patients with delirium had a single definite or probable etiology, while the other 44% had about 2.8 etiologies per patient on average. Delirium risk factors, causes, and factors to consider during patient evaluation are listed in Table 21,3,5-7 and Table 3.1,3,5-7

A synergistic relationship between comorbidities, environment, and medications can induce delirium.5 Identifying irreversible and reversible causes is the key to treating delirium. After the cause has been identified, it can be addressed and the patient could return to his/her previous level of functioning. If the delirium is the result of multiple irreversible causes, it could become chronic.

[polldaddy:10332749]

EVALUATION Cardiac dysfunction

Ms. P undergoes laboratory testing. The results include: white blood cell count, 5.9/µL; hemoglobin, 13.6 g/dL; hematocrit, 42.6%; platelets, 304 × 103/µL; sodium,143 mEq/L; potassium, 3.2 mEq/L; chloride, 96 mEq/L; carbon dioxide, 23 mEq/L; blood glucose, 87 mg/dL; creatinine, 1.2 mg/dL; estimated creatinine clearance (eCrCl) level of 33 mL/min/1.73 m2; calcium, 9.5 mg/dL; albumin, 3.6 g/dL; liver enzymes within normal limits; thyroid-stimulating hormone, 0.78 mIU/L; vitamin B12, 995 pg/mL; folic acid, 16.6 ng/mL; vitamin D, 31 pg/mL; and rapid plasma reagin: nonreactive. Urinalysis is unremarkable, and no culture is performed. Urine drug screening/toxicology is positive for the benzodiazepines that she received in the ED (oral alprazolam 0.25 mg given once and oral lorazepam 0.5 mg given once).

Electrocardiogram (ECG) shows atrial flutter/tachycardia with rapid ventricular response, marked left axis deviation, nonspecific ST- and T-wave abnormality, QT/QTC of 301/387 ms, and ventricular rate 151 beats per minute. A CT scan of the head and brain without contrast shows mild atrophy and chronic white matter changes and no acute intracranial abnormality. A two-view chest radiography shows no acute cardiopulmonary findings. Her temperature is 98.4°F; heart rate is 122 beats per minute; respiratory rate is 20 breaths per minute; blood pressure is 161/98 mm Hg; and oxygen saturation is 86% on room air.

Based on this data, Ms. P’s cardiac condition seems to be worsening, which is thought to be caused by her refusal of furosemide, lisinopril, isosorbide, sotalol, clopidogrel, and aspirin. The treatment team plans to work on compliance to resolve these cardiac issues and places Ms. P on 1:1 observation with a sitter and music in attempt to calm her.

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Many factors can contribute to behavioral or cognitive changes in geriatric patients. Often, a major change noted in an older patient can be attributed to new-onset dementia, dementia with behavioral disturbances, delirium, depression, or acute psychosis. These potential causes should be considered and ruled out in a step-by-step progression. Because patients are unreliable historians during acute distress, a complete history from family or caregivers and exhaustive workup is paramount.

TREATMENT Medication adjustments

In an attempt to resolve Ms. P’s disruptive behaviors, her risperidone dosage is changed to 0.5 mg twice daily. Ms. P is encouraged to use the provided oxygen to raise her saturation level.

On hospital Day 3, a loose stool prompts a Clostridium difficile test as a possible source of delirium; however, the results are negative.

On hospital Day 4, Ms. P is confused and irritable overnight, yelling profanities at staff, refusing care, inappropriately disrobing, and having difficulty falling asleep and staying asleep. Risperidone is discontinued because it appears to have had little or no effect on Ms. P’s disruptive behaviors. Olanzapine, 10 mg/d, is initiated with mirtazapine, 7.5 mg/d, to help with mood, appetite, and sleep. Fluoxetine is also discontinued because of a possible interaction with clopidogrel.

On hospital Days 6 to 8, Ms. P remains upset and unable to follow instructions. Melatonin is initiated to improve her sleep cycle. On Day 9, she continues to decline and is cursing at hospital staff; haloperidol is initiated at 5 mg every morning, 10 mg at bedtime, and 5 mg IM as needed for agitation. Her sleep improves with melatonin and mirtazapine. IV hydration also is initiated. Ms. P has a slight improvement in medication compliance. On Day 11, haloperidol is increased to 5 mg in the morning, 5 mg in the afternoon, and 10 mg at bedtime. On Day 12, haloperidol is changed to 7.5 mg twice daily; a slight improvement in Ms. P’s behavior is noted.

Continue to: On hospital Day 13...

On hospital Day 13, Ms. P’s behavior declines again. She screams profanities at staff and does not recognize the clinicians who have been providing care to her. The physician initiates valproic acid, 125 mg, 3 times a day, to target Ms. P’s behavioral disturbances. A pharmacist notes that the patient’s sotalol could be contributing to Ms. P’s psychiatric presentation, and that based on her eCrCl level of 33 mL/min/1.73 m2, a dosage adjustment or medication change might be warranted.

On Day 14, Ms. P displays erratic behavior and intermittent tachycardia. A cardiac consultation is ordered. A repeat ECG reveals atrial fibrillation with rapid rate and a QT/QTc of 409/432 ms. Ms. P is transferred to the telemetry unit, where the cardiologist discontinues sotalol because the dosage is not properly renally adjusted. Sotalol hydrochloride has been associated with life-threatening ventricular tachycardia.8 Diltiazem, 30 mg every 6 hours is initiated to replace sotalol.

By Day 16, the treatment team notes improved cognition and behavior. On Day 17, the cardiologist reports that Ms. P’s atrial fibrillation is controlled. An ECG reveals mild left ventricular hypertrophy, an ejection fraction of 50% to 55%, no stenosis in the mitral or tricuspid valves, no valvular pulmonic stenosis, and moderate aortic sclerosis. Cardiac markers also are evaluated (creatinine phosphokinase: 105 U/L; creatinine kinase–MB fraction: 2.6 ng/mL; troponin: 0.01 ng/mL; pro-B-type natriuretic peptide: 2,073 pg/mL); and myocardial infarction is ruled out.

On Day 19, Ms. P’s diltiazem is consolidated to a controlled-delivery formulation, 180 mg/d, along with the addition of metoprolol, 12.5 mg twice daily. Ms. P is transferred back to the psychiatric unit.

OUTCOME Gradual improvement

On Days 20 to 23, Ms. P shows remarkable progress, and her mental status, cognition, and behavior slowly return to baseline. Haloperidol and valproic acid are tapered and discontinued. Ms. P is observed to be healthy and oriented to person, place, and time.

Continue to: On Day 25...

On Day 25, she is discharged from the hospital, and returns to the LTC facility.

The authors’ observations

Ms. P’s delirium was a combination of her older age, non-renally adjusted sotalol, and CKD. At admission, the hospital treatment team first thought that pneumonia or antibiotic use could have caused delirium. However, Ms. P’s condition did not improve after antibiotics were stopped. In addition, several chest radiographs found no evidence of pneumonia. It is important to check for any source of infection because infection is a common source of delirium in older patients.1 Urine samples revealed no pathogens, a C. difficile test was negative, and the patient’s white blood cell counts remained within normal limits. Physicians began looking elsewhere for potential causes of Ms. P’s delirium.

Ms. P’s vital signs ruled out a temperature irregularity or hypertension as the cause of her delirium. She has a slightly low oxygen saturation when she first presented, but this quickly returned to normal with administration of oxygen, which ruled out hypoxemia. Laboratory results concluded that Ms. P’s glucose levels were within a normal range and she had no electrolyte imbalances. A head CT scan showed slight atrophy of white matter that is consistent with Ms. P’s age. The head CT scan also showed that Ms. P had no acute condition or head trauma.

In terms of organ function, Ms. P was in relatively healthy condition other than paroxysmal atrial fibrillation and CKD. Chronic kidney disease can interrupt the normal pharmacokinetics of medications. Reviewing Ms. P’s medication list, several agents could have induced delirium, including antidepressants, antipsychotics, cardiovascular medications (beta blocker/antiarrhythmic [sotalol]), and opioid analgesics such as tramadol.5 Ms. P’s condition did not improve after discontinuing fluoxetine, risperidone, or olanzapine, although haloperidol was started in their place. Ms. P scored an 8 on the Naranjo Adverse Drug Reaction Probability Scale, indicating this event was a probable adverse drug reaction.9

Identifying a cause

This was a unique case where sotalol was identified as the culprit for inducing Ms. P’s delirium, because her age and CKD are irreversible. It is important to note that antiarrhythmics can induce arrhythmias when present in high concentrations or administered without appropriate renal dose adjustments. Although Ms. P’s serum levels of sotalol were not evaluated, because of her renal impairment, it is possible that toxic levels of sotalol accumulated and lead to arrhythmias and delirium. Of note, a cardiologist was consulted to safely change Ms. P to a calcium channel blocker so she could undergo cardiac monitoring. With the addition of diltiazem and metoprolol, the patient’s delirium subsided and her arrhythmia was controlled. Once the source of Ms. P’s delirium had been identified, antipsychotics were no longer needed.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Delirium is a complex disorder that often has multiple causes, both reversible and irreversible. A “process of elimination” approach should be used to accurately identify and manage delirium. If a patient with delirium has little to no response to antipsychotic medications, the underlying cause or causes likely has not yet been addressed, and the evaluation should continue.

Related Resources

- Marcantonio ER. Delirium in hospitalized older adults. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1456-1466.

- Inouye SK, Westendorp RGJ, Saczynski JS. Delirium in elderly people. Lancet. 2014;383(9920):911-922.

Drug Brand Names

Acyclovir • Zovirax

Alprazolam • Niravam, Xanax

Amantadine • Symmetrel

Amphotericin B • Abelcet

Atorvastatin • Lipitor

Atropine • Atropen

Baclofen • EnovaRX-Baclofen

Benztropine • Cogentin

Bromocriptine • Cycloset

Calcitonin • Miacalcin

Carbamazepine • Tegretol

Carbidopa-levodopa • Duopa

Ceftriaxone • Rocephin

Chlorpromazine • Thorazine

Clonidine • Catapres

Clopidogrel • Plavix

Cyclobenzaprine • Amrix

Digoxin • Lanoxin

Diltiazem • Cardizem

Disulfiram • Antabuse

Ezetimibe • Zetia

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluphenazine • Prolixin

Furosemide • Lasix

Haloperidol • Haldol

Ipratropium/albuterol nebulized solution • Combivent Respimat

Isoniazid • Isotamine

Isosorbide nitrate • Dilatrate

Levetiracetam • Keppra

Levodopa • Stalevo

Linezolid • Zyvox

Lisinopril • Zestril

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lorazepam • Ativan

Magnesium Oxide • Mag-200

Meperidine • Demerol

Methyldopa • Aldomet

Metoprolol • Lopressor

Metronidazole • Flagyl

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Nitrofurantoin • Macrobid

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Pantoprazole • Protonix

Phenytoin • Dilantin

Pramipexole • Mirapex

Rifampin • Rifadin

Risperidone • Risperdal

Ropinirole • Requip

Sotalol hydrochloride • Betapace AF

Tramadol • Ultram

Trihexyphenidyl • Trihexane

Valproic acid • Depakote

1. Fong TG, Tulebaev SR, Inouye SK. Delirium in elderly adults: diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5(4):210-220.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

3. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with delirium. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(suppl 5):1-20.

4. Francis J, Kapoor WN. Delirium in hospitalized elderly. J Gen Intern Med. 1990;5(1):65-79.

5. Alagiakrishnan K, Wiens CA. An approach to drug induced delirium in the elderly. Postgrad Med J. 2004;80(945):388-393.

6. Cook IA. Guideline watch: practice guideline for the treatment of patients with delirium. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2004.

7. Bourgeois J, Ategan A, Losier B. Delirium in the hospital: emphasis on the management of geriatric patients. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(8):29,36-42.

8. Betapace AF [package insert]. Zug, Switzerland: Covis Pharma; 2016.

9. Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30(2):239-245.

CASE Combative and agitated

Ms. P, age 87, presents to the emergency department (ED) with her caregiver, who says Ms. P has new-onset altered mental status, agitation, and combativeness.

Ms. P resides at a long-term care (LTC) facility, where according to the nurses she normally is pleasant, well-oriented, and cooperative. Ms. P’s medical history includes major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, hypertension, chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage III, peptic ulcer disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease, coronary artery disease with 2 past myocardial infarctions requiring stents, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hyperlipidemia, bradycardia requiring a pacemaker, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, asthma, aortic stenosis, peripheral vascular disease, esophageal stricture requiring dilation, deep vein thrombosis, and migraines.

Mr. P’s medication list includes acetaminophen, 650 mg every 6 hours; ipratropium/albuterol nebulized solution, 3 mL 4 times a day; aspirin, 81 mg/d; atorvastatin, 40 mg/d; calcitonin, 1 spray nasally at bedtime; clopidogrel, 75 mg/d; ezetimibe, 10 mg/d; fluoxetine, 20 mg/d; furosemide, 20 mg/d; isosorbide dinitrate, 120 mg/d; lisinopril, 15 mg/d; risperidone, 0.5 mg/d; magnesium oxide, 800 mg/d; pantoprazole, 40 mg/d; polyethylene glycol, 17 g/d; sotalol, 160 mg/d; olanzapine, 5 mg IM every 6 hours as needed for agitation; and tramadol, 50 mg every 8 hours as needed for headache.

Seven days before coming to the ED, Ms. P was started on ceftriaxone, 1 g/d, for suspected community-acquired pneumonia. At that time, the nursing staff noticed behavioral changes. Soon after, Ms. P began refusing all her medications. Two days before presenting to the ED, Ms. P was started on nitrofurantoin, 200 mg/d, for a suspected urinary tract infection, but it was discontinued because of an allergy.

Her caregiver reports that while at the LTC facility, Ms. P’s behavioral changes worsened. Ms. P claimed to be Jesus Christ and said she was talking to the devil; she chased other residents around the facility and slapped medications away from the nursing staff. According to caregivers, this behavior was out of character.

Shortly after arriving in the ED, Ms. P is admitted to the psychiatric unit.

[polldaddy:10332748]

The authors’ observations

Delirium is a complex, acute alteration in a patient’s mental status compared with his/her baseline functioning1 (Table 12). The onset of delirium is quick, happening within hours to days, with fluctuations in mental function. Patients might present with hyperactive, hypoactive, or mixed delirium.3 Patients with hyperactive delirium often have delusions and hallucinations; these patients might be agitated and could become violent with family and caregivers.3 Patients with hypoactive delirium are less likely to experience hallucinations and more likely to show symptoms of sedation.3 Patients with hypoactive delirium can be difficult to diagnose because it is challenging to interview them and understand what might be the cause of their sedated state. Patients also can exhibit a mixed delirium in which they fluctuate between periods of hyperactivity and hypoactivity.3

Continue to: Suspected delirium...

Suspected delirium should be considered a medical emergency because the outcome could be fatal.1 It is important to uncover and treat the underlying cause(s) of delirium rather than solely administering antipsychotics, which might mask the presenting symptoms. In an older study, Francis and Kapoor4 reported that 56% of geriatric patients with delirium had a single definite or probable etiology, while the other 44% had about 2.8 etiologies per patient on average. Delirium risk factors, causes, and factors to consider during patient evaluation are listed in Table 21,3,5-7 and Table 3.1,3,5-7

A synergistic relationship between comorbidities, environment, and medications can induce delirium.5 Identifying irreversible and reversible causes is the key to treating delirium. After the cause has been identified, it can be addressed and the patient could return to his/her previous level of functioning. If the delirium is the result of multiple irreversible causes, it could become chronic.

[polldaddy:10332749]

EVALUATION Cardiac dysfunction

Ms. P undergoes laboratory testing. The results include: white blood cell count, 5.9/µL; hemoglobin, 13.6 g/dL; hematocrit, 42.6%; platelets, 304 × 103/µL; sodium,143 mEq/L; potassium, 3.2 mEq/L; chloride, 96 mEq/L; carbon dioxide, 23 mEq/L; blood glucose, 87 mg/dL; creatinine, 1.2 mg/dL; estimated creatinine clearance (eCrCl) level of 33 mL/min/1.73 m2; calcium, 9.5 mg/dL; albumin, 3.6 g/dL; liver enzymes within normal limits; thyroid-stimulating hormone, 0.78 mIU/L; vitamin B12, 995 pg/mL; folic acid, 16.6 ng/mL; vitamin D, 31 pg/mL; and rapid plasma reagin: nonreactive. Urinalysis is unremarkable, and no culture is performed. Urine drug screening/toxicology is positive for the benzodiazepines that she received in the ED (oral alprazolam 0.25 mg given once and oral lorazepam 0.5 mg given once).

Electrocardiogram (ECG) shows atrial flutter/tachycardia with rapid ventricular response, marked left axis deviation, nonspecific ST- and T-wave abnormality, QT/QTC of 301/387 ms, and ventricular rate 151 beats per minute. A CT scan of the head and brain without contrast shows mild atrophy and chronic white matter changes and no acute intracranial abnormality. A two-view chest radiography shows no acute cardiopulmonary findings. Her temperature is 98.4°F; heart rate is 122 beats per minute; respiratory rate is 20 breaths per minute; blood pressure is 161/98 mm Hg; and oxygen saturation is 86% on room air.

Based on this data, Ms. P’s cardiac condition seems to be worsening, which is thought to be caused by her refusal of furosemide, lisinopril, isosorbide, sotalol, clopidogrel, and aspirin. The treatment team plans to work on compliance to resolve these cardiac issues and places Ms. P on 1:1 observation with a sitter and music in attempt to calm her.

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Many factors can contribute to behavioral or cognitive changes in geriatric patients. Often, a major change noted in an older patient can be attributed to new-onset dementia, dementia with behavioral disturbances, delirium, depression, or acute psychosis. These potential causes should be considered and ruled out in a step-by-step progression. Because patients are unreliable historians during acute distress, a complete history from family or caregivers and exhaustive workup is paramount.

TREATMENT Medication adjustments

In an attempt to resolve Ms. P’s disruptive behaviors, her risperidone dosage is changed to 0.5 mg twice daily. Ms. P is encouraged to use the provided oxygen to raise her saturation level.

On hospital Day 3, a loose stool prompts a Clostridium difficile test as a possible source of delirium; however, the results are negative.

On hospital Day 4, Ms. P is confused and irritable overnight, yelling profanities at staff, refusing care, inappropriately disrobing, and having difficulty falling asleep and staying asleep. Risperidone is discontinued because it appears to have had little or no effect on Ms. P’s disruptive behaviors. Olanzapine, 10 mg/d, is initiated with mirtazapine, 7.5 mg/d, to help with mood, appetite, and sleep. Fluoxetine is also discontinued because of a possible interaction with clopidogrel.

On hospital Days 6 to 8, Ms. P remains upset and unable to follow instructions. Melatonin is initiated to improve her sleep cycle. On Day 9, she continues to decline and is cursing at hospital staff; haloperidol is initiated at 5 mg every morning, 10 mg at bedtime, and 5 mg IM as needed for agitation. Her sleep improves with melatonin and mirtazapine. IV hydration also is initiated. Ms. P has a slight improvement in medication compliance. On Day 11, haloperidol is increased to 5 mg in the morning, 5 mg in the afternoon, and 10 mg at bedtime. On Day 12, haloperidol is changed to 7.5 mg twice daily; a slight improvement in Ms. P’s behavior is noted.

Continue to: On hospital Day 13...

On hospital Day 13, Ms. P’s behavior declines again. She screams profanities at staff and does not recognize the clinicians who have been providing care to her. The physician initiates valproic acid, 125 mg, 3 times a day, to target Ms. P’s behavioral disturbances. A pharmacist notes that the patient’s sotalol could be contributing to Ms. P’s psychiatric presentation, and that based on her eCrCl level of 33 mL/min/1.73 m2, a dosage adjustment or medication change might be warranted.

On Day 14, Ms. P displays erratic behavior and intermittent tachycardia. A cardiac consultation is ordered. A repeat ECG reveals atrial fibrillation with rapid rate and a QT/QTc of 409/432 ms. Ms. P is transferred to the telemetry unit, where the cardiologist discontinues sotalol because the dosage is not properly renally adjusted. Sotalol hydrochloride has been associated with life-threatening ventricular tachycardia.8 Diltiazem, 30 mg every 6 hours is initiated to replace sotalol.

By Day 16, the treatment team notes improved cognition and behavior. On Day 17, the cardiologist reports that Ms. P’s atrial fibrillation is controlled. An ECG reveals mild left ventricular hypertrophy, an ejection fraction of 50% to 55%, no stenosis in the mitral or tricuspid valves, no valvular pulmonic stenosis, and moderate aortic sclerosis. Cardiac markers also are evaluated (creatinine phosphokinase: 105 U/L; creatinine kinase–MB fraction: 2.6 ng/mL; troponin: 0.01 ng/mL; pro-B-type natriuretic peptide: 2,073 pg/mL); and myocardial infarction is ruled out.

On Day 19, Ms. P’s diltiazem is consolidated to a controlled-delivery formulation, 180 mg/d, along with the addition of metoprolol, 12.5 mg twice daily. Ms. P is transferred back to the psychiatric unit.

OUTCOME Gradual improvement

On Days 20 to 23, Ms. P shows remarkable progress, and her mental status, cognition, and behavior slowly return to baseline. Haloperidol and valproic acid are tapered and discontinued. Ms. P is observed to be healthy and oriented to person, place, and time.

Continue to: On Day 25...

On Day 25, she is discharged from the hospital, and returns to the LTC facility.

The authors’ observations

Ms. P’s delirium was a combination of her older age, non-renally adjusted sotalol, and CKD. At admission, the hospital treatment team first thought that pneumonia or antibiotic use could have caused delirium. However, Ms. P’s condition did not improve after antibiotics were stopped. In addition, several chest radiographs found no evidence of pneumonia. It is important to check for any source of infection because infection is a common source of delirium in older patients.1 Urine samples revealed no pathogens, a C. difficile test was negative, and the patient’s white blood cell counts remained within normal limits. Physicians began looking elsewhere for potential causes of Ms. P’s delirium.

Ms. P’s vital signs ruled out a temperature irregularity or hypertension as the cause of her delirium. She has a slightly low oxygen saturation when she first presented, but this quickly returned to normal with administration of oxygen, which ruled out hypoxemia. Laboratory results concluded that Ms. P’s glucose levels were within a normal range and she had no electrolyte imbalances. A head CT scan showed slight atrophy of white matter that is consistent with Ms. P’s age. The head CT scan also showed that Ms. P had no acute condition or head trauma.

In terms of organ function, Ms. P was in relatively healthy condition other than paroxysmal atrial fibrillation and CKD. Chronic kidney disease can interrupt the normal pharmacokinetics of medications. Reviewing Ms. P’s medication list, several agents could have induced delirium, including antidepressants, antipsychotics, cardiovascular medications (beta blocker/antiarrhythmic [sotalol]), and opioid analgesics such as tramadol.5 Ms. P’s condition did not improve after discontinuing fluoxetine, risperidone, or olanzapine, although haloperidol was started in their place. Ms. P scored an 8 on the Naranjo Adverse Drug Reaction Probability Scale, indicating this event was a probable adverse drug reaction.9

Identifying a cause

This was a unique case where sotalol was identified as the culprit for inducing Ms. P’s delirium, because her age and CKD are irreversible. It is important to note that antiarrhythmics can induce arrhythmias when present in high concentrations or administered without appropriate renal dose adjustments. Although Ms. P’s serum levels of sotalol were not evaluated, because of her renal impairment, it is possible that toxic levels of sotalol accumulated and lead to arrhythmias and delirium. Of note, a cardiologist was consulted to safely change Ms. P to a calcium channel blocker so she could undergo cardiac monitoring. With the addition of diltiazem and metoprolol, the patient’s delirium subsided and her arrhythmia was controlled. Once the source of Ms. P’s delirium had been identified, antipsychotics were no longer needed.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Delirium is a complex disorder that often has multiple causes, both reversible and irreversible. A “process of elimination” approach should be used to accurately identify and manage delirium. If a patient with delirium has little to no response to antipsychotic medications, the underlying cause or causes likely has not yet been addressed, and the evaluation should continue.

Related Resources

- Marcantonio ER. Delirium in hospitalized older adults. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1456-1466.

- Inouye SK, Westendorp RGJ, Saczynski JS. Delirium in elderly people. Lancet. 2014;383(9920):911-922.

Drug Brand Names

Acyclovir • Zovirax

Alprazolam • Niravam, Xanax

Amantadine • Symmetrel

Amphotericin B • Abelcet

Atorvastatin • Lipitor

Atropine • Atropen

Baclofen • EnovaRX-Baclofen

Benztropine • Cogentin

Bromocriptine • Cycloset

Calcitonin • Miacalcin

Carbamazepine • Tegretol

Carbidopa-levodopa • Duopa

Ceftriaxone • Rocephin

Chlorpromazine • Thorazine

Clonidine • Catapres

Clopidogrel • Plavix

Cyclobenzaprine • Amrix

Digoxin • Lanoxin

Diltiazem • Cardizem

Disulfiram • Antabuse

Ezetimibe • Zetia

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluphenazine • Prolixin

Furosemide • Lasix

Haloperidol • Haldol

Ipratropium/albuterol nebulized solution • Combivent Respimat

Isoniazid • Isotamine

Isosorbide nitrate • Dilatrate

Levetiracetam • Keppra

Levodopa • Stalevo

Linezolid • Zyvox

Lisinopril • Zestril

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lorazepam • Ativan

Magnesium Oxide • Mag-200

Meperidine • Demerol

Methyldopa • Aldomet

Metoprolol • Lopressor

Metronidazole • Flagyl

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Nitrofurantoin • Macrobid

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Pantoprazole • Protonix

Phenytoin • Dilantin

Pramipexole • Mirapex

Rifampin • Rifadin

Risperidone • Risperdal

Ropinirole • Requip

Sotalol hydrochloride • Betapace AF

Tramadol • Ultram

Trihexyphenidyl • Trihexane

Valproic acid • Depakote

CASE Combative and agitated

Ms. P, age 87, presents to the emergency department (ED) with her caregiver, who says Ms. P has new-onset altered mental status, agitation, and combativeness.

Ms. P resides at a long-term care (LTC) facility, where according to the nurses she normally is pleasant, well-oriented, and cooperative. Ms. P’s medical history includes major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, hypertension, chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage III, peptic ulcer disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease, coronary artery disease with 2 past myocardial infarctions requiring stents, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hyperlipidemia, bradycardia requiring a pacemaker, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, asthma, aortic stenosis, peripheral vascular disease, esophageal stricture requiring dilation, deep vein thrombosis, and migraines.

Mr. P’s medication list includes acetaminophen, 650 mg every 6 hours; ipratropium/albuterol nebulized solution, 3 mL 4 times a day; aspirin, 81 mg/d; atorvastatin, 40 mg/d; calcitonin, 1 spray nasally at bedtime; clopidogrel, 75 mg/d; ezetimibe, 10 mg/d; fluoxetine, 20 mg/d; furosemide, 20 mg/d; isosorbide dinitrate, 120 mg/d; lisinopril, 15 mg/d; risperidone, 0.5 mg/d; magnesium oxide, 800 mg/d; pantoprazole, 40 mg/d; polyethylene glycol, 17 g/d; sotalol, 160 mg/d; olanzapine, 5 mg IM every 6 hours as needed for agitation; and tramadol, 50 mg every 8 hours as needed for headache.

Seven days before coming to the ED, Ms. P was started on ceftriaxone, 1 g/d, for suspected community-acquired pneumonia. At that time, the nursing staff noticed behavioral changes. Soon after, Ms. P began refusing all her medications. Two days before presenting to the ED, Ms. P was started on nitrofurantoin, 200 mg/d, for a suspected urinary tract infection, but it was discontinued because of an allergy.

Her caregiver reports that while at the LTC facility, Ms. P’s behavioral changes worsened. Ms. P claimed to be Jesus Christ and said she was talking to the devil; she chased other residents around the facility and slapped medications away from the nursing staff. According to caregivers, this behavior was out of character.

Shortly after arriving in the ED, Ms. P is admitted to the psychiatric unit.

[polldaddy:10332748]

The authors’ observations

Delirium is a complex, acute alteration in a patient’s mental status compared with his/her baseline functioning1 (Table 12). The onset of delirium is quick, happening within hours to days, with fluctuations in mental function. Patients might present with hyperactive, hypoactive, or mixed delirium.3 Patients with hyperactive delirium often have delusions and hallucinations; these patients might be agitated and could become violent with family and caregivers.3 Patients with hypoactive delirium are less likely to experience hallucinations and more likely to show symptoms of sedation.3 Patients with hypoactive delirium can be difficult to diagnose because it is challenging to interview them and understand what might be the cause of their sedated state. Patients also can exhibit a mixed delirium in which they fluctuate between periods of hyperactivity and hypoactivity.3

Continue to: Suspected delirium...

Suspected delirium should be considered a medical emergency because the outcome could be fatal.1 It is important to uncover and treat the underlying cause(s) of delirium rather than solely administering antipsychotics, which might mask the presenting symptoms. In an older study, Francis and Kapoor4 reported that 56% of geriatric patients with delirium had a single definite or probable etiology, while the other 44% had about 2.8 etiologies per patient on average. Delirium risk factors, causes, and factors to consider during patient evaluation are listed in Table 21,3,5-7 and Table 3.1,3,5-7

A synergistic relationship between comorbidities, environment, and medications can induce delirium.5 Identifying irreversible and reversible causes is the key to treating delirium. After the cause has been identified, it can be addressed and the patient could return to his/her previous level of functioning. If the delirium is the result of multiple irreversible causes, it could become chronic.

[polldaddy:10332749]

EVALUATION Cardiac dysfunction

Ms. P undergoes laboratory testing. The results include: white blood cell count, 5.9/µL; hemoglobin, 13.6 g/dL; hematocrit, 42.6%; platelets, 304 × 103/µL; sodium,143 mEq/L; potassium, 3.2 mEq/L; chloride, 96 mEq/L; carbon dioxide, 23 mEq/L; blood glucose, 87 mg/dL; creatinine, 1.2 mg/dL; estimated creatinine clearance (eCrCl) level of 33 mL/min/1.73 m2; calcium, 9.5 mg/dL; albumin, 3.6 g/dL; liver enzymes within normal limits; thyroid-stimulating hormone, 0.78 mIU/L; vitamin B12, 995 pg/mL; folic acid, 16.6 ng/mL; vitamin D, 31 pg/mL; and rapid plasma reagin: nonreactive. Urinalysis is unremarkable, and no culture is performed. Urine drug screening/toxicology is positive for the benzodiazepines that she received in the ED (oral alprazolam 0.25 mg given once and oral lorazepam 0.5 mg given once).

Electrocardiogram (ECG) shows atrial flutter/tachycardia with rapid ventricular response, marked left axis deviation, nonspecific ST- and T-wave abnormality, QT/QTC of 301/387 ms, and ventricular rate 151 beats per minute. A CT scan of the head and brain without contrast shows mild atrophy and chronic white matter changes and no acute intracranial abnormality. A two-view chest radiography shows no acute cardiopulmonary findings. Her temperature is 98.4°F; heart rate is 122 beats per minute; respiratory rate is 20 breaths per minute; blood pressure is 161/98 mm Hg; and oxygen saturation is 86% on room air.

Based on this data, Ms. P’s cardiac condition seems to be worsening, which is thought to be caused by her refusal of furosemide, lisinopril, isosorbide, sotalol, clopidogrel, and aspirin. The treatment team plans to work on compliance to resolve these cardiac issues and places Ms. P on 1:1 observation with a sitter and music in attempt to calm her.

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Many factors can contribute to behavioral or cognitive changes in geriatric patients. Often, a major change noted in an older patient can be attributed to new-onset dementia, dementia with behavioral disturbances, delirium, depression, or acute psychosis. These potential causes should be considered and ruled out in a step-by-step progression. Because patients are unreliable historians during acute distress, a complete history from family or caregivers and exhaustive workup is paramount.

TREATMENT Medication adjustments

In an attempt to resolve Ms. P’s disruptive behaviors, her risperidone dosage is changed to 0.5 mg twice daily. Ms. P is encouraged to use the provided oxygen to raise her saturation level.

On hospital Day 3, a loose stool prompts a Clostridium difficile test as a possible source of delirium; however, the results are negative.

On hospital Day 4, Ms. P is confused and irritable overnight, yelling profanities at staff, refusing care, inappropriately disrobing, and having difficulty falling asleep and staying asleep. Risperidone is discontinued because it appears to have had little or no effect on Ms. P’s disruptive behaviors. Olanzapine, 10 mg/d, is initiated with mirtazapine, 7.5 mg/d, to help with mood, appetite, and sleep. Fluoxetine is also discontinued because of a possible interaction with clopidogrel.

On hospital Days 6 to 8, Ms. P remains upset and unable to follow instructions. Melatonin is initiated to improve her sleep cycle. On Day 9, she continues to decline and is cursing at hospital staff; haloperidol is initiated at 5 mg every morning, 10 mg at bedtime, and 5 mg IM as needed for agitation. Her sleep improves with melatonin and mirtazapine. IV hydration also is initiated. Ms. P has a slight improvement in medication compliance. On Day 11, haloperidol is increased to 5 mg in the morning, 5 mg in the afternoon, and 10 mg at bedtime. On Day 12, haloperidol is changed to 7.5 mg twice daily; a slight improvement in Ms. P’s behavior is noted.

Continue to: On hospital Day 13...

On hospital Day 13, Ms. P’s behavior declines again. She screams profanities at staff and does not recognize the clinicians who have been providing care to her. The physician initiates valproic acid, 125 mg, 3 times a day, to target Ms. P’s behavioral disturbances. A pharmacist notes that the patient’s sotalol could be contributing to Ms. P’s psychiatric presentation, and that based on her eCrCl level of 33 mL/min/1.73 m2, a dosage adjustment or medication change might be warranted.

On Day 14, Ms. P displays erratic behavior and intermittent tachycardia. A cardiac consultation is ordered. A repeat ECG reveals atrial fibrillation with rapid rate and a QT/QTc of 409/432 ms. Ms. P is transferred to the telemetry unit, where the cardiologist discontinues sotalol because the dosage is not properly renally adjusted. Sotalol hydrochloride has been associated with life-threatening ventricular tachycardia.8 Diltiazem, 30 mg every 6 hours is initiated to replace sotalol.

By Day 16, the treatment team notes improved cognition and behavior. On Day 17, the cardiologist reports that Ms. P’s atrial fibrillation is controlled. An ECG reveals mild left ventricular hypertrophy, an ejection fraction of 50% to 55%, no stenosis in the mitral or tricuspid valves, no valvular pulmonic stenosis, and moderate aortic sclerosis. Cardiac markers also are evaluated (creatinine phosphokinase: 105 U/L; creatinine kinase–MB fraction: 2.6 ng/mL; troponin: 0.01 ng/mL; pro-B-type natriuretic peptide: 2,073 pg/mL); and myocardial infarction is ruled out.

On Day 19, Ms. P’s diltiazem is consolidated to a controlled-delivery formulation, 180 mg/d, along with the addition of metoprolol, 12.5 mg twice daily. Ms. P is transferred back to the psychiatric unit.

OUTCOME Gradual improvement

On Days 20 to 23, Ms. P shows remarkable progress, and her mental status, cognition, and behavior slowly return to baseline. Haloperidol and valproic acid are tapered and discontinued. Ms. P is observed to be healthy and oriented to person, place, and time.

Continue to: On Day 25...

On Day 25, she is discharged from the hospital, and returns to the LTC facility.

The authors’ observations

Ms. P’s delirium was a combination of her older age, non-renally adjusted sotalol, and CKD. At admission, the hospital treatment team first thought that pneumonia or antibiotic use could have caused delirium. However, Ms. P’s condition did not improve after antibiotics were stopped. In addition, several chest radiographs found no evidence of pneumonia. It is important to check for any source of infection because infection is a common source of delirium in older patients.1 Urine samples revealed no pathogens, a C. difficile test was negative, and the patient’s white blood cell counts remained within normal limits. Physicians began looking elsewhere for potential causes of Ms. P’s delirium.

Ms. P’s vital signs ruled out a temperature irregularity or hypertension as the cause of her delirium. She has a slightly low oxygen saturation when she first presented, but this quickly returned to normal with administration of oxygen, which ruled out hypoxemia. Laboratory results concluded that Ms. P’s glucose levels were within a normal range and she had no electrolyte imbalances. A head CT scan showed slight atrophy of white matter that is consistent with Ms. P’s age. The head CT scan also showed that Ms. P had no acute condition or head trauma.

In terms of organ function, Ms. P was in relatively healthy condition other than paroxysmal atrial fibrillation and CKD. Chronic kidney disease can interrupt the normal pharmacokinetics of medications. Reviewing Ms. P’s medication list, several agents could have induced delirium, including antidepressants, antipsychotics, cardiovascular medications (beta blocker/antiarrhythmic [sotalol]), and opioid analgesics such as tramadol.5 Ms. P’s condition did not improve after discontinuing fluoxetine, risperidone, or olanzapine, although haloperidol was started in their place. Ms. P scored an 8 on the Naranjo Adverse Drug Reaction Probability Scale, indicating this event was a probable adverse drug reaction.9

Identifying a cause

This was a unique case where sotalol was identified as the culprit for inducing Ms. P’s delirium, because her age and CKD are irreversible. It is important to note that antiarrhythmics can induce arrhythmias when present in high concentrations or administered without appropriate renal dose adjustments. Although Ms. P’s serum levels of sotalol were not evaluated, because of her renal impairment, it is possible that toxic levels of sotalol accumulated and lead to arrhythmias and delirium. Of note, a cardiologist was consulted to safely change Ms. P to a calcium channel blocker so she could undergo cardiac monitoring. With the addition of diltiazem and metoprolol, the patient’s delirium subsided and her arrhythmia was controlled. Once the source of Ms. P’s delirium had been identified, antipsychotics were no longer needed.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Delirium is a complex disorder that often has multiple causes, both reversible and irreversible. A “process of elimination” approach should be used to accurately identify and manage delirium. If a patient with delirium has little to no response to antipsychotic medications, the underlying cause or causes likely has not yet been addressed, and the evaluation should continue.

Related Resources

- Marcantonio ER. Delirium in hospitalized older adults. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1456-1466.

- Inouye SK, Westendorp RGJ, Saczynski JS. Delirium in elderly people. Lancet. 2014;383(9920):911-922.

Drug Brand Names

Acyclovir • Zovirax

Alprazolam • Niravam, Xanax

Amantadine • Symmetrel

Amphotericin B • Abelcet

Atorvastatin • Lipitor

Atropine • Atropen

Baclofen • EnovaRX-Baclofen

Benztropine • Cogentin

Bromocriptine • Cycloset

Calcitonin • Miacalcin

Carbamazepine • Tegretol

Carbidopa-levodopa • Duopa

Ceftriaxone • Rocephin

Chlorpromazine • Thorazine

Clonidine • Catapres

Clopidogrel • Plavix

Cyclobenzaprine • Amrix

Digoxin • Lanoxin

Diltiazem • Cardizem

Disulfiram • Antabuse

Ezetimibe • Zetia

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluphenazine • Prolixin

Furosemide • Lasix

Haloperidol • Haldol

Ipratropium/albuterol nebulized solution • Combivent Respimat

Isoniazid • Isotamine

Isosorbide nitrate • Dilatrate

Levetiracetam • Keppra

Levodopa • Stalevo

Linezolid • Zyvox

Lisinopril • Zestril

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lorazepam • Ativan

Magnesium Oxide • Mag-200

Meperidine • Demerol

Methyldopa • Aldomet

Metoprolol • Lopressor

Metronidazole • Flagyl

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Nitrofurantoin • Macrobid

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Pantoprazole • Protonix

Phenytoin • Dilantin

Pramipexole • Mirapex

Rifampin • Rifadin

Risperidone • Risperdal

Ropinirole • Requip

Sotalol hydrochloride • Betapace AF

Tramadol • Ultram

Trihexyphenidyl • Trihexane

Valproic acid • Depakote

1. Fong TG, Tulebaev SR, Inouye SK. Delirium in elderly adults: diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5(4):210-220.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

3. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with delirium. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(suppl 5):1-20.

4. Francis J, Kapoor WN. Delirium in hospitalized elderly. J Gen Intern Med. 1990;5(1):65-79.

5. Alagiakrishnan K, Wiens CA. An approach to drug induced delirium in the elderly. Postgrad Med J. 2004;80(945):388-393.

6. Cook IA. Guideline watch: practice guideline for the treatment of patients with delirium. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2004.

7. Bourgeois J, Ategan A, Losier B. Delirium in the hospital: emphasis on the management of geriatric patients. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(8):29,36-42.

8. Betapace AF [package insert]. Zug, Switzerland: Covis Pharma; 2016.

9. Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30(2):239-245.

1. Fong TG, Tulebaev SR, Inouye SK. Delirium in elderly adults: diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5(4):210-220.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

3. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with delirium. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(suppl 5):1-20.

4. Francis J, Kapoor WN. Delirium in hospitalized elderly. J Gen Intern Med. 1990;5(1):65-79.

5. Alagiakrishnan K, Wiens CA. An approach to drug induced delirium in the elderly. Postgrad Med J. 2004;80(945):388-393.

6. Cook IA. Guideline watch: practice guideline for the treatment of patients with delirium. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2004.

7. Bourgeois J, Ategan A, Losier B. Delirium in the hospital: emphasis on the management of geriatric patients. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(8):29,36-42.

8. Betapace AF [package insert]. Zug, Switzerland: Covis Pharma; 2016.

9. Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30(2):239-245.