User login

Atretic Cephalocele With Hypertrichosis

To the Editor:

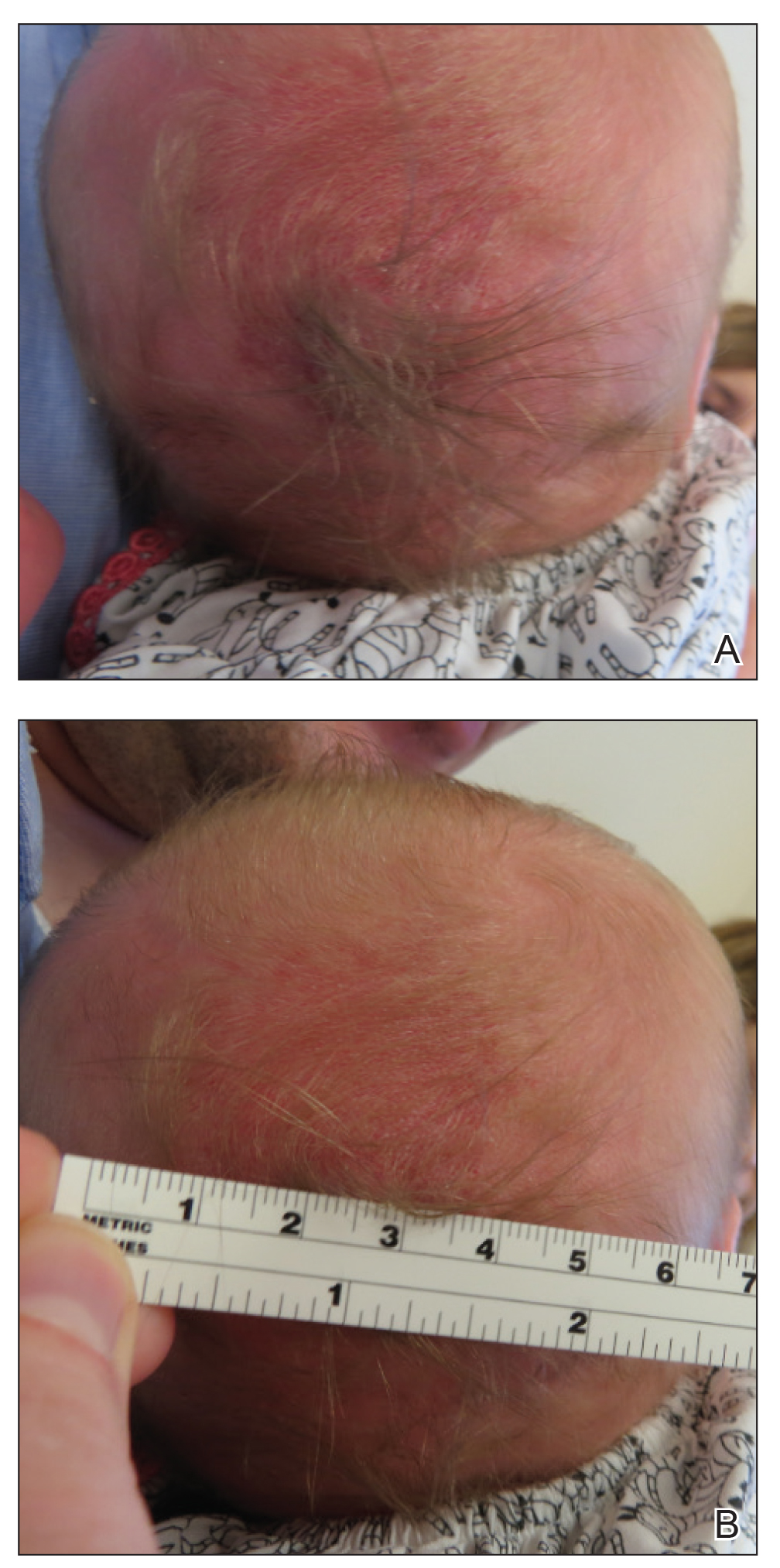

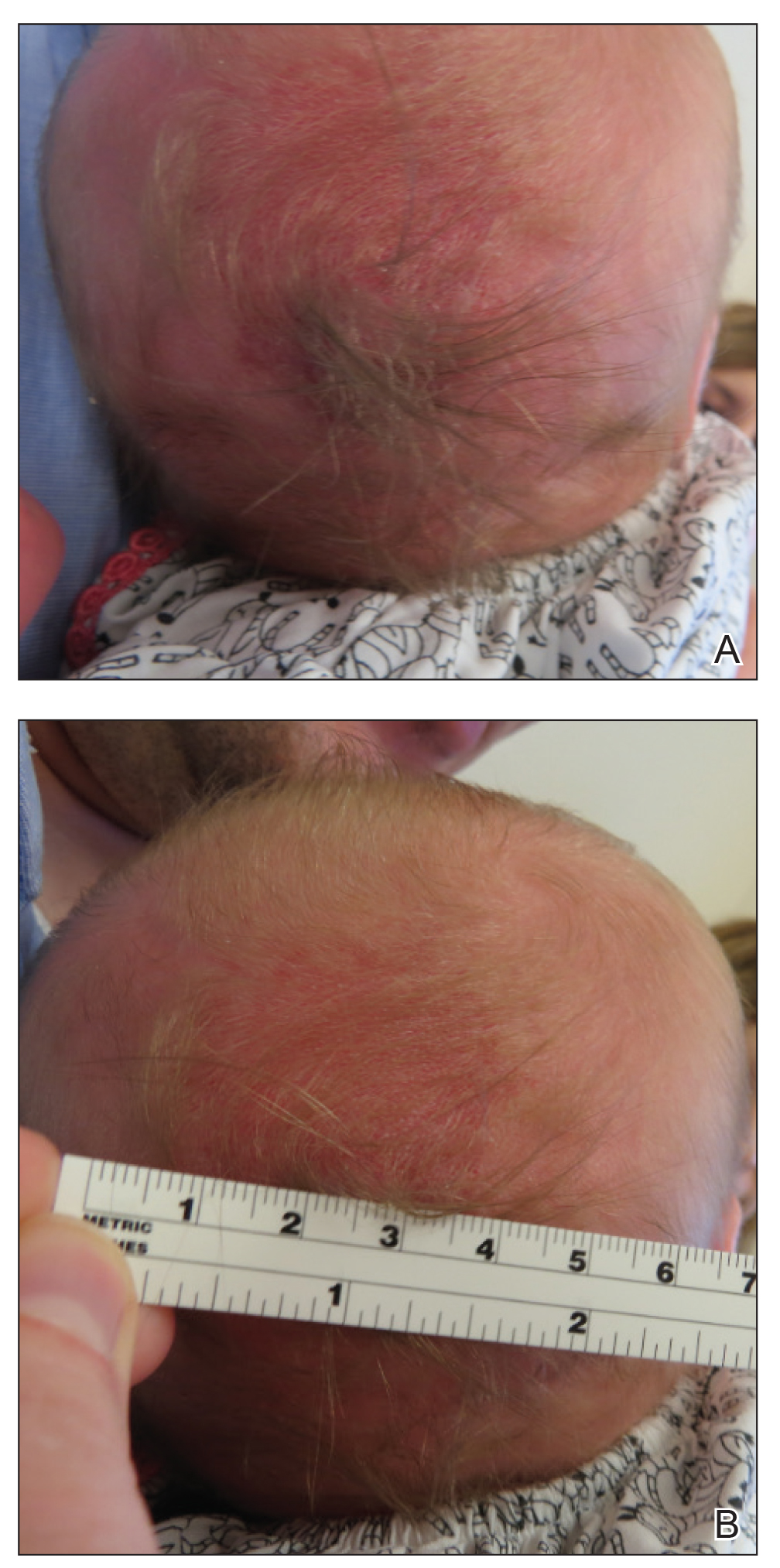

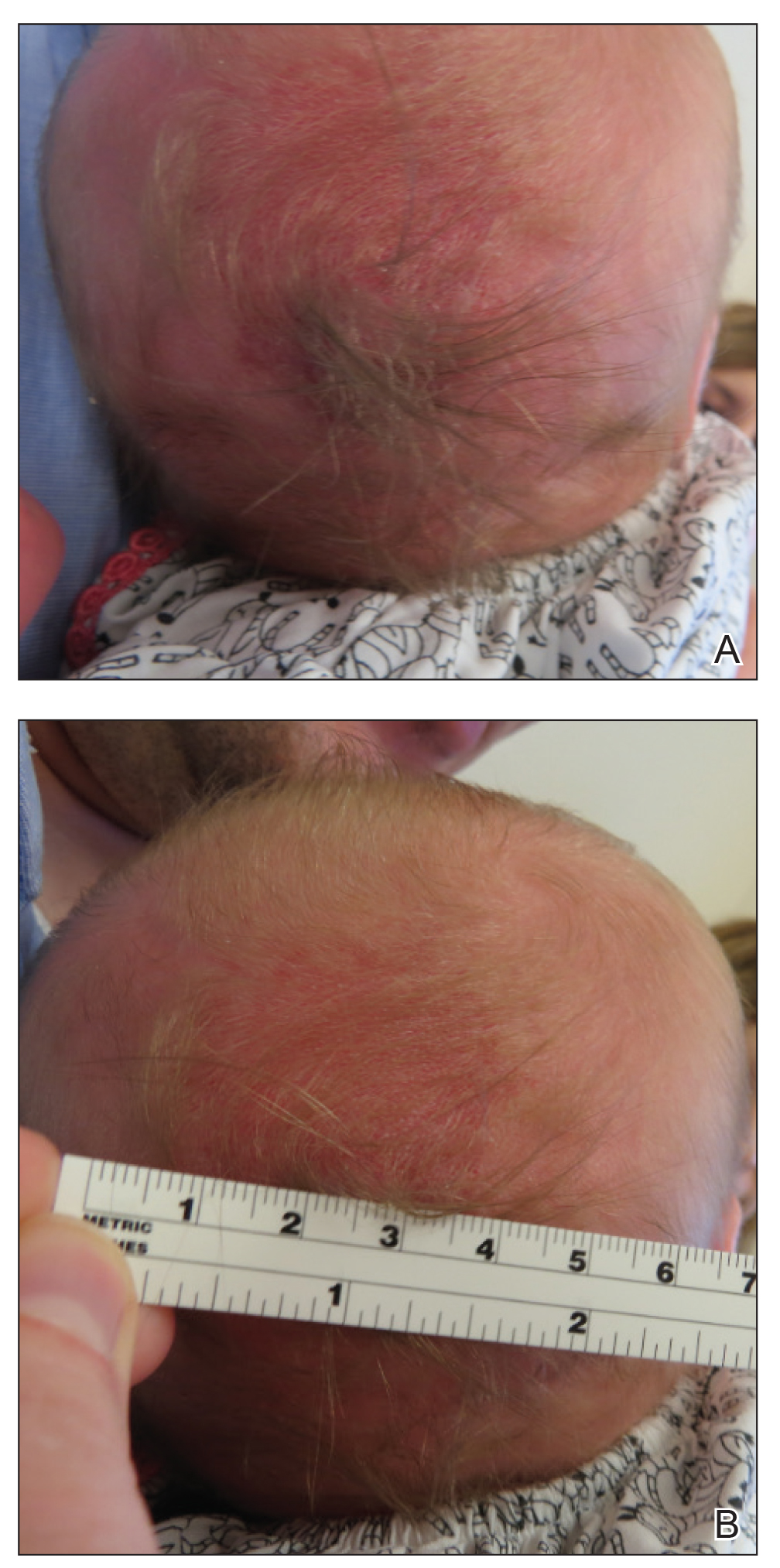

A 2-week-old female infant presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a 4.0×4.5-cm pink-red patch with a 1-cm central nodule and an overlying tuft of hair on the midline occipital region (Figure). The patient was born at 39 weeks’ gestation to nonconsanguineous parents via a normal spontaneous vaginal delivery and had an unremarkable prenatal course with no complications since birth. The red patch and tuft of hair were noted at birth, and the parents reported that the redness varied somewhat in size throughout the day and from day to day. An initial neurologic workup revealed no gross neurologic abnormalities. A head ultrasound revealed a soft-tissue hypervascular nodule that appeared separate from bony structures but showed evidence of a necklike extension from the nodule to the underlying soft tissues. The ultrasound could not definitively rule out intracranial extension; gross brain structures appeared normal. The initial differential diagnosis consisted of a congenital hemangioma (either a rapidly involuting or noninvoluting subtype), meningioma, or cephalocele.

Consultation with the pediatric neurosurgery service was sought, and magnetic resonance imaging of the head was performed, which demonstrated a cystic lesion within the subcutaneous soft tissue in the midline posterior scalp approximately 2 cm above the torcula. There also was a thin stalk extending from the cyst and going through an osseous defect within the occipital bone and attaching to the falx cerebri. There was no evidence of any venous communication with the cerebral sinus tracts or intraparenchymal extension. No intracranial abnormalities were noted. Given the radiographic evidence, a presumptive diagnosis of an atretic cephalocele was made with the plan for surgical repair.

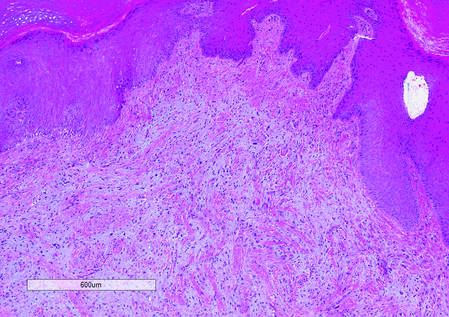

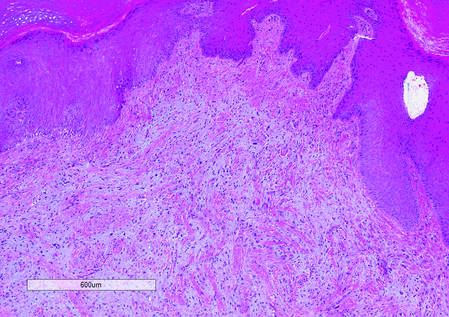

The patient was re-evaluated at 3 and 4 months of age; there were no changes in the size or appearance of the lesion, and she continued to meet all developmental milestones. At 9 months of age the patient underwent uncomplicated neurosurgery to repair the cephalocele. Histopathologic examination of the resected lesion was consistent with an atretic cephalocele and showed positive staining for epithelial membrane antigen, which further confirmed a meningothelial origin; no glial elements were identified. The postoperative course was uncomplicated, and the patient was healing well at a follow-up examination 2 weeks after the procedure.

This case highlights the importance of an extensive workup when a patient presents with a midline lesion and hypertrichosis. The patient’s red patch, excluding the hair tuft, was reminiscent of a vascular malformation or hemangioma precursor lesion given the hypervascularity, the history of the lesion being present since birth, the lack of neurologic symptomatology, and the history of meeting all developmental milestones. The differential diagnosis for this patient was extensive, as many neurologic conditions present with cutaneous findings. Having central nervous system (CNS) and cutaneous comorbidities coincide underscores their common neuroectodermal origin during embryogenesis.1,2

Atretic cephalocele is a rare diagnosis, with the prevalence of cephaloceles estimated to be 0.8 to 3.0 per 10,000 births.3 It typically occurs in either the parietal or occipital scalp as a skin nodule with a hair tuft or alopecic lesion with or without a hair collar. A cephalocele is defined as a skin-covered protrusion of intracranial contents through a bony defect. Central nervous system tissue, meninges, or cerebrospinal fluid can protrude outside the skull with this condition. An atretic cephalocele refers to a cephalocele that arrested in development and represents approximately 40% to 50% of all cephaloceles.4 Various hypotheses have explained the development of atretic cephaloceles: it represents a neural crest remnant, regression of a meningocele in utero, injury of multipotential mesenchymal cells, and either failure of the neural tube to close or reopening of the neural tube after closure.4-6 There is evidence of developmental defects in skin appendages including sweat and sebaceous glands, arrector pili muscles, and hair follicles in and around the skin overlying the cephalocele, suggesting that there is a developmental abnormality of not only the CNS but also the cutaneous tissue.5 Typical radiographic findings include a cystic lesion with underlying defect in the skull. A vertical positioning of the straight sinus also has been demonstrated to be a consistent finding that can aid in diagnosis.4

Imaging is of utmost importance when a patient presents with a tuft of hair on the scalp to rule out intracranial extension and associated abnormalities such as gray matter heterotopia, hypogenesis of the corpus callosum, hydrocephalus, and Dandy-Walker and Walker-Warburg syndromes, which have all been associated with atretic cephaloceles.4,7 The impact of location of the intracranial abnormality on prognosis has been contested, with some reporting a better prognosis with occipital cephalocele vs parietal cephalocele while others have found the opposite to be true.6,7

Cutaneous abnormalities presenting with hypertrichosis (ie, hair tuft, hair collar) and/or capillary malformations increase the likelihood of a cranial dysraphism, especially when these findings present together and occur in and around the midline. Clinical examination cannot rule out an underlying connection to the CNS; these findings require appropriate radiographic imaging assessment prior to any procedural intervention.

- Drolet BA, Clowry L, McTigue K, et al. The hair collar sign: marker for cranial dysraphism. Pediatrics. 1995;96(2, pt 1):309-313.

- Sewell MJ, Chiu YE, Drolet BA. Neural tube dysraphism: review of cutaneous markers and imaging. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:161-170.

- Carvalho DR, Giuliani LR, Simão GN, et al. Autosomal dominant atretic cephalocele with phenotype variability: report of a Brazilian family with six affected in four generation. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140:1458-1462.

- Bick DS, Brockland JJ, Scott AR. A scalp lesion with intracranial extension. atretic cephalocele. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;141:289-290.

- Fukuyama M, Tanese K, Yasuda F, et al. Two cases of atretic cephalocele, and histological evaluation of skin appendages in the surrounding skin. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:48-52.

- Martinez-Lage JF, Sola J, Casas C, et al. Atretic cephalocele: the tip of the iceberg. J Neurosurg. 1992;77:230-235.

- Yakota A, Kajiwara H, Kohchi M, et al. Parietal cephalocele: clinical importance of its atretic form and associated malformation. J Neurosurg. 1988;69:545-551.

To the Editor:

A 2-week-old female infant presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a 4.0×4.5-cm pink-red patch with a 1-cm central nodule and an overlying tuft of hair on the midline occipital region (Figure). The patient was born at 39 weeks’ gestation to nonconsanguineous parents via a normal spontaneous vaginal delivery and had an unremarkable prenatal course with no complications since birth. The red patch and tuft of hair were noted at birth, and the parents reported that the redness varied somewhat in size throughout the day and from day to day. An initial neurologic workup revealed no gross neurologic abnormalities. A head ultrasound revealed a soft-tissue hypervascular nodule that appeared separate from bony structures but showed evidence of a necklike extension from the nodule to the underlying soft tissues. The ultrasound could not definitively rule out intracranial extension; gross brain structures appeared normal. The initial differential diagnosis consisted of a congenital hemangioma (either a rapidly involuting or noninvoluting subtype), meningioma, or cephalocele.

Consultation with the pediatric neurosurgery service was sought, and magnetic resonance imaging of the head was performed, which demonstrated a cystic lesion within the subcutaneous soft tissue in the midline posterior scalp approximately 2 cm above the torcula. There also was a thin stalk extending from the cyst and going through an osseous defect within the occipital bone and attaching to the falx cerebri. There was no evidence of any venous communication with the cerebral sinus tracts or intraparenchymal extension. No intracranial abnormalities were noted. Given the radiographic evidence, a presumptive diagnosis of an atretic cephalocele was made with the plan for surgical repair.

The patient was re-evaluated at 3 and 4 months of age; there were no changes in the size or appearance of the lesion, and she continued to meet all developmental milestones. At 9 months of age the patient underwent uncomplicated neurosurgery to repair the cephalocele. Histopathologic examination of the resected lesion was consistent with an atretic cephalocele and showed positive staining for epithelial membrane antigen, which further confirmed a meningothelial origin; no glial elements were identified. The postoperative course was uncomplicated, and the patient was healing well at a follow-up examination 2 weeks after the procedure.

This case highlights the importance of an extensive workup when a patient presents with a midline lesion and hypertrichosis. The patient’s red patch, excluding the hair tuft, was reminiscent of a vascular malformation or hemangioma precursor lesion given the hypervascularity, the history of the lesion being present since birth, the lack of neurologic symptomatology, and the history of meeting all developmental milestones. The differential diagnosis for this patient was extensive, as many neurologic conditions present with cutaneous findings. Having central nervous system (CNS) and cutaneous comorbidities coincide underscores their common neuroectodermal origin during embryogenesis.1,2

Atretic cephalocele is a rare diagnosis, with the prevalence of cephaloceles estimated to be 0.8 to 3.0 per 10,000 births.3 It typically occurs in either the parietal or occipital scalp as a skin nodule with a hair tuft or alopecic lesion with or without a hair collar. A cephalocele is defined as a skin-covered protrusion of intracranial contents through a bony defect. Central nervous system tissue, meninges, or cerebrospinal fluid can protrude outside the skull with this condition. An atretic cephalocele refers to a cephalocele that arrested in development and represents approximately 40% to 50% of all cephaloceles.4 Various hypotheses have explained the development of atretic cephaloceles: it represents a neural crest remnant, regression of a meningocele in utero, injury of multipotential mesenchymal cells, and either failure of the neural tube to close or reopening of the neural tube after closure.4-6 There is evidence of developmental defects in skin appendages including sweat and sebaceous glands, arrector pili muscles, and hair follicles in and around the skin overlying the cephalocele, suggesting that there is a developmental abnormality of not only the CNS but also the cutaneous tissue.5 Typical radiographic findings include a cystic lesion with underlying defect in the skull. A vertical positioning of the straight sinus also has been demonstrated to be a consistent finding that can aid in diagnosis.4

Imaging is of utmost importance when a patient presents with a tuft of hair on the scalp to rule out intracranial extension and associated abnormalities such as gray matter heterotopia, hypogenesis of the corpus callosum, hydrocephalus, and Dandy-Walker and Walker-Warburg syndromes, which have all been associated with atretic cephaloceles.4,7 The impact of location of the intracranial abnormality on prognosis has been contested, with some reporting a better prognosis with occipital cephalocele vs parietal cephalocele while others have found the opposite to be true.6,7

Cutaneous abnormalities presenting with hypertrichosis (ie, hair tuft, hair collar) and/or capillary malformations increase the likelihood of a cranial dysraphism, especially when these findings present together and occur in and around the midline. Clinical examination cannot rule out an underlying connection to the CNS; these findings require appropriate radiographic imaging assessment prior to any procedural intervention.

To the Editor:

A 2-week-old female infant presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a 4.0×4.5-cm pink-red patch with a 1-cm central nodule and an overlying tuft of hair on the midline occipital region (Figure). The patient was born at 39 weeks’ gestation to nonconsanguineous parents via a normal spontaneous vaginal delivery and had an unremarkable prenatal course with no complications since birth. The red patch and tuft of hair were noted at birth, and the parents reported that the redness varied somewhat in size throughout the day and from day to day. An initial neurologic workup revealed no gross neurologic abnormalities. A head ultrasound revealed a soft-tissue hypervascular nodule that appeared separate from bony structures but showed evidence of a necklike extension from the nodule to the underlying soft tissues. The ultrasound could not definitively rule out intracranial extension; gross brain structures appeared normal. The initial differential diagnosis consisted of a congenital hemangioma (either a rapidly involuting or noninvoluting subtype), meningioma, or cephalocele.

Consultation with the pediatric neurosurgery service was sought, and magnetic resonance imaging of the head was performed, which demonstrated a cystic lesion within the subcutaneous soft tissue in the midline posterior scalp approximately 2 cm above the torcula. There also was a thin stalk extending from the cyst and going through an osseous defect within the occipital bone and attaching to the falx cerebri. There was no evidence of any venous communication with the cerebral sinus tracts or intraparenchymal extension. No intracranial abnormalities were noted. Given the radiographic evidence, a presumptive diagnosis of an atretic cephalocele was made with the plan for surgical repair.

The patient was re-evaluated at 3 and 4 months of age; there were no changes in the size or appearance of the lesion, and she continued to meet all developmental milestones. At 9 months of age the patient underwent uncomplicated neurosurgery to repair the cephalocele. Histopathologic examination of the resected lesion was consistent with an atretic cephalocele and showed positive staining for epithelial membrane antigen, which further confirmed a meningothelial origin; no glial elements were identified. The postoperative course was uncomplicated, and the patient was healing well at a follow-up examination 2 weeks after the procedure.

This case highlights the importance of an extensive workup when a patient presents with a midline lesion and hypertrichosis. The patient’s red patch, excluding the hair tuft, was reminiscent of a vascular malformation or hemangioma precursor lesion given the hypervascularity, the history of the lesion being present since birth, the lack of neurologic symptomatology, and the history of meeting all developmental milestones. The differential diagnosis for this patient was extensive, as many neurologic conditions present with cutaneous findings. Having central nervous system (CNS) and cutaneous comorbidities coincide underscores their common neuroectodermal origin during embryogenesis.1,2

Atretic cephalocele is a rare diagnosis, with the prevalence of cephaloceles estimated to be 0.8 to 3.0 per 10,000 births.3 It typically occurs in either the parietal or occipital scalp as a skin nodule with a hair tuft or alopecic lesion with or without a hair collar. A cephalocele is defined as a skin-covered protrusion of intracranial contents through a bony defect. Central nervous system tissue, meninges, or cerebrospinal fluid can protrude outside the skull with this condition. An atretic cephalocele refers to a cephalocele that arrested in development and represents approximately 40% to 50% of all cephaloceles.4 Various hypotheses have explained the development of atretic cephaloceles: it represents a neural crest remnant, regression of a meningocele in utero, injury of multipotential mesenchymal cells, and either failure of the neural tube to close or reopening of the neural tube after closure.4-6 There is evidence of developmental defects in skin appendages including sweat and sebaceous glands, arrector pili muscles, and hair follicles in and around the skin overlying the cephalocele, suggesting that there is a developmental abnormality of not only the CNS but also the cutaneous tissue.5 Typical radiographic findings include a cystic lesion with underlying defect in the skull. A vertical positioning of the straight sinus also has been demonstrated to be a consistent finding that can aid in diagnosis.4

Imaging is of utmost importance when a patient presents with a tuft of hair on the scalp to rule out intracranial extension and associated abnormalities such as gray matter heterotopia, hypogenesis of the corpus callosum, hydrocephalus, and Dandy-Walker and Walker-Warburg syndromes, which have all been associated with atretic cephaloceles.4,7 The impact of location of the intracranial abnormality on prognosis has been contested, with some reporting a better prognosis with occipital cephalocele vs parietal cephalocele while others have found the opposite to be true.6,7

Cutaneous abnormalities presenting with hypertrichosis (ie, hair tuft, hair collar) and/or capillary malformations increase the likelihood of a cranial dysraphism, especially when these findings present together and occur in and around the midline. Clinical examination cannot rule out an underlying connection to the CNS; these findings require appropriate radiographic imaging assessment prior to any procedural intervention.

- Drolet BA, Clowry L, McTigue K, et al. The hair collar sign: marker for cranial dysraphism. Pediatrics. 1995;96(2, pt 1):309-313.

- Sewell MJ, Chiu YE, Drolet BA. Neural tube dysraphism: review of cutaneous markers and imaging. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:161-170.

- Carvalho DR, Giuliani LR, Simão GN, et al. Autosomal dominant atretic cephalocele with phenotype variability: report of a Brazilian family with six affected in four generation. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140:1458-1462.

- Bick DS, Brockland JJ, Scott AR. A scalp lesion with intracranial extension. atretic cephalocele. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;141:289-290.

- Fukuyama M, Tanese K, Yasuda F, et al. Two cases of atretic cephalocele, and histological evaluation of skin appendages in the surrounding skin. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:48-52.

- Martinez-Lage JF, Sola J, Casas C, et al. Atretic cephalocele: the tip of the iceberg. J Neurosurg. 1992;77:230-235.

- Yakota A, Kajiwara H, Kohchi M, et al. Parietal cephalocele: clinical importance of its atretic form and associated malformation. J Neurosurg. 1988;69:545-551.

- Drolet BA, Clowry L, McTigue K, et al. The hair collar sign: marker for cranial dysraphism. Pediatrics. 1995;96(2, pt 1):309-313.

- Sewell MJ, Chiu YE, Drolet BA. Neural tube dysraphism: review of cutaneous markers and imaging. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:161-170.

- Carvalho DR, Giuliani LR, Simão GN, et al. Autosomal dominant atretic cephalocele with phenotype variability: report of a Brazilian family with six affected in four generation. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140:1458-1462.

- Bick DS, Brockland JJ, Scott AR. A scalp lesion with intracranial extension. atretic cephalocele. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;141:289-290.

- Fukuyama M, Tanese K, Yasuda F, et al. Two cases of atretic cephalocele, and histological evaluation of skin appendages in the surrounding skin. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:48-52.

- Martinez-Lage JF, Sola J, Casas C, et al. Atretic cephalocele: the tip of the iceberg. J Neurosurg. 1992;77:230-235.

- Yakota A, Kajiwara H, Kohchi M, et al. Parietal cephalocele: clinical importance of its atretic form and associated malformation. J Neurosurg. 1988;69:545-551.

Practice Points

- Atretic cephalocele is a rare diagnosis occurring on the scalp as a nodule with an overlying hair tuft or alopecia with or without a hair collar.

- Imaging is of utmost importance when presented with a tuft of hair on the midline to rule out intracranial extension and associated abnormalities.

Sunburn Purpura

To the Editor:

Chronic UV exposure has been linked to increased skin fragility and the development of purpuric lesions, a benign condition known as actinic purpura and commonly seen in elderly patients. Petechial skin changes acutely following intense sun exposure is a rare phenomenon referred to as sunburn purpura, photolocalized purpura, or solar purpura.

A 19-year-old woman presented with red and purple spots on the pretibial region of both legs extending to the thigh. One week prior to presentation she had a severe sunburn affecting most of the body, which resolved without blistering. Two days later, the spots appeared within the most severely sunburned areas of both legs. The patient reported that the lesions were mildly painful to palpation, but she was more concerned about the appearance. She denied any history of similar skin changes associated with sun exposure. The patient was otherwise healthy and denied any recent illnesses. She noted a history of mild bruising and bleeding with a resulting unremarkable workup by her primary care physician. The only medication taken was etonogestrel-ethinyl estradiol vaginal ring.

The scalp, face, arms, trunk, and legs were examined, and nonpalpable petechial changes were noted on the anterior aspect of the legs (Figure 1), with changes more prominent on the distal aspect of the legs. Mild superficial epidermal exfoliation was noted on both anterior thighs. The area of the lesions was not warm. The lesions were mildly tender to palpation. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable.

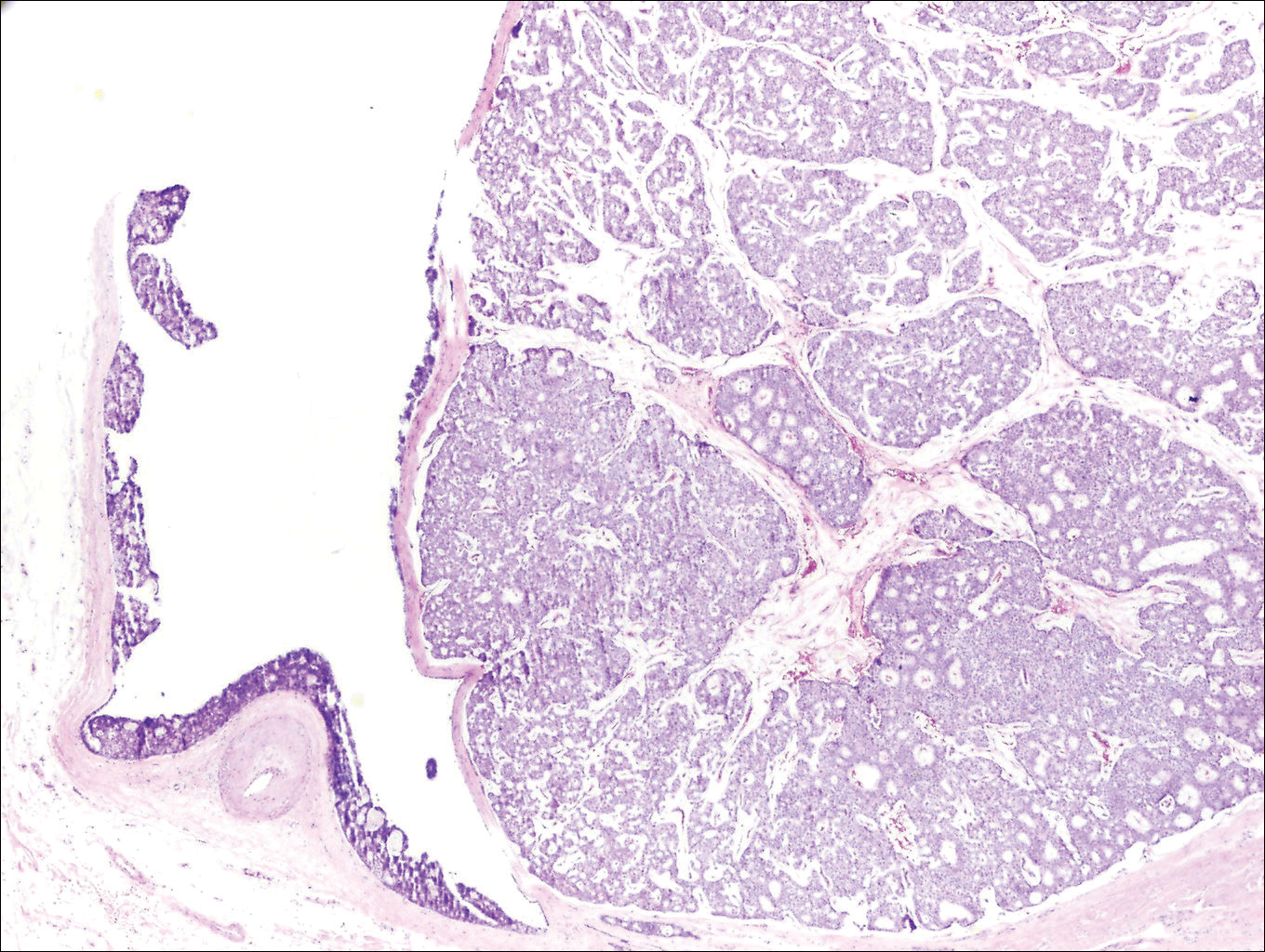

Given the timing of onset, preceding sun exposure, and the morphologic characteristics of the lesions, sunburn purpura was suspected. A punch biopsy of the anterior aspect of the left thigh was performed to rule out vasculitis. Microscopic examination revealed reactive epidermal changes with mild vascular ectasia and erythrocyte extravasation not associated with appreciable inflammation or evidence of vascular injury (Figure 2). Biopsy exposure to fluorescein-labeled antibodies directed against IgG, IgM, IgA, C3, and polyvalent immunoglobulins (IgG, IgM, and IgA) yielded no immunofluorescence. These biopsy results were consistent with sunburn purpura. Given the patient's normal platelet count, a diagnosis of idiopathic sunburn purpura was made. The patient was informed of the biopsy results and advised that the petechiae should resolve without treatment in 1 to 2 weeks, which occurred.

Sunburn purpura remains a rare phenomenon in which a petechial or purpuric rash develops acutely after intense sun exposure. We prefer the term sunburn purpura because it reflects the acuity of the phenomenon, as opposed to the previous labels solar purpura or photolocalized purpura, which also could suggest causality from chronic sun exposure. It has been proposed that sunburn purpura is a finding associated with a number of conditions rather than a unique entity.1 The following characteristics can be helpful in describing the development of sunburn purpura: delay following UV exposure, gross morphology, histologic findings, and possible associated medical conditions.1 Our case represents an important addition to the literature, as it differs from previously reported cases. Most importantly, the nonspecific biopsy findings and unremarkable laboratory findings associated with our case may represent primary or idiopathic sunburn purpura.

Previously reported cases of sunburn purpura have occurred in patients aged 10 to 66 years. It has been seen following UV exposure, vigorous exercise and high-dose aspirin, or concurrent fluoroquinolone therapy, or in the setting of erythropoietic protoporphyria, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, or polymorphous light eruption.2-8 When performed, histology has revealed capillaritis, solar elastosis, perivascular infiltrate, lymphocytic perivascular infiltrate with dermal edema, or leukocytoclastic vasculitis.1,2,7-9 Our patient did not have a history of erythropoietic protoporphyria, polymorphous light eruption, or idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. She had not recently exercised, was not thrombocytopenic, and was not taking antiplatelet medications. She had no recent history of fluoroquinolone use. On histologic examination, our patient's biopsy demonstrated nonspecific petechial changes without signs of chronic UV exposure, dermal edema, vasculitis, lymphocytic infiltrate, or capillaritis.

Idiopathic sunburn purpura should only be diagnosed after other conditions are excluded. When evaluating a patient who presents with new-onset petechial rash following sun exposure, it is important to rule out vasculitis or thrombocytopenia as the cause, which is best achieved through skin biopsy and a platelet count, respectively. If there are no associated symptoms or thrombocytopenia and biopsy shows nonspecific vascular ectasia and erythrocyte extravasation, the physician should consider the diagnosis of idiopathic sunburn (solar or photolocalized) purpura. Along with regular UV protection, the physician should advise that the rash typically resolves without treatment in 1 to 2 weeks.

- Waters AJ, Sandhu DR, Green CM, et al. Solar capillaritis as a cause of solar purpura. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:E821-E824.

- Latenser BA, Hempstead RW. Exercise-associated solar purpura in an atypical location. Cutis. 1985;35:365-366.

- Rubegni P, Feci L, Pellegrino M, et al. Photolocalized purpura during levofloxacin therapy. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:105-107.

- Urbina F, Barrios M, Sudy E. Photolocalized purpura during ciprofloxacin therapy. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2006;22:111-112.

- Torinuki W, Miura T. Erythropoietic protoporphyria showing solar purpura. Dermatologica. 1983;167:220-222.

- Leung AK. Purpura associated with exposure to sunlight. J R Soc Med. 1986;79:423-424.

- Kalivas J, Kalivas L. Solar purpura appearing in a patient with polymorphous light eruption. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 1995;11:31-32.

- Ros AM. Solar purpura--an unusual manifestation of polymorphous light eruption. Photodermatol. 1988;5:47-48.

- Guarrera M, Parodi A, Rebora A. Solar purpura is not related to polymorphous light eruption. Photodermatol. 1989;6:293-294.

To the Editor:

Chronic UV exposure has been linked to increased skin fragility and the development of purpuric lesions, a benign condition known as actinic purpura and commonly seen in elderly patients. Petechial skin changes acutely following intense sun exposure is a rare phenomenon referred to as sunburn purpura, photolocalized purpura, or solar purpura.

A 19-year-old woman presented with red and purple spots on the pretibial region of both legs extending to the thigh. One week prior to presentation she had a severe sunburn affecting most of the body, which resolved without blistering. Two days later, the spots appeared within the most severely sunburned areas of both legs. The patient reported that the lesions were mildly painful to palpation, but she was more concerned about the appearance. She denied any history of similar skin changes associated with sun exposure. The patient was otherwise healthy and denied any recent illnesses. She noted a history of mild bruising and bleeding with a resulting unremarkable workup by her primary care physician. The only medication taken was etonogestrel-ethinyl estradiol vaginal ring.

The scalp, face, arms, trunk, and legs were examined, and nonpalpable petechial changes were noted on the anterior aspect of the legs (Figure 1), with changes more prominent on the distal aspect of the legs. Mild superficial epidermal exfoliation was noted on both anterior thighs. The area of the lesions was not warm. The lesions were mildly tender to palpation. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable.

Given the timing of onset, preceding sun exposure, and the morphologic characteristics of the lesions, sunburn purpura was suspected. A punch biopsy of the anterior aspect of the left thigh was performed to rule out vasculitis. Microscopic examination revealed reactive epidermal changes with mild vascular ectasia and erythrocyte extravasation not associated with appreciable inflammation or evidence of vascular injury (Figure 2). Biopsy exposure to fluorescein-labeled antibodies directed against IgG, IgM, IgA, C3, and polyvalent immunoglobulins (IgG, IgM, and IgA) yielded no immunofluorescence. These biopsy results were consistent with sunburn purpura. Given the patient's normal platelet count, a diagnosis of idiopathic sunburn purpura was made. The patient was informed of the biopsy results and advised that the petechiae should resolve without treatment in 1 to 2 weeks, which occurred.

Sunburn purpura remains a rare phenomenon in which a petechial or purpuric rash develops acutely after intense sun exposure. We prefer the term sunburn purpura because it reflects the acuity of the phenomenon, as opposed to the previous labels solar purpura or photolocalized purpura, which also could suggest causality from chronic sun exposure. It has been proposed that sunburn purpura is a finding associated with a number of conditions rather than a unique entity.1 The following characteristics can be helpful in describing the development of sunburn purpura: delay following UV exposure, gross morphology, histologic findings, and possible associated medical conditions.1 Our case represents an important addition to the literature, as it differs from previously reported cases. Most importantly, the nonspecific biopsy findings and unremarkable laboratory findings associated with our case may represent primary or idiopathic sunburn purpura.

Previously reported cases of sunburn purpura have occurred in patients aged 10 to 66 years. It has been seen following UV exposure, vigorous exercise and high-dose aspirin, or concurrent fluoroquinolone therapy, or in the setting of erythropoietic protoporphyria, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, or polymorphous light eruption.2-8 When performed, histology has revealed capillaritis, solar elastosis, perivascular infiltrate, lymphocytic perivascular infiltrate with dermal edema, or leukocytoclastic vasculitis.1,2,7-9 Our patient did not have a history of erythropoietic protoporphyria, polymorphous light eruption, or idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. She had not recently exercised, was not thrombocytopenic, and was not taking antiplatelet medications. She had no recent history of fluoroquinolone use. On histologic examination, our patient's biopsy demonstrated nonspecific petechial changes without signs of chronic UV exposure, dermal edema, vasculitis, lymphocytic infiltrate, or capillaritis.

Idiopathic sunburn purpura should only be diagnosed after other conditions are excluded. When evaluating a patient who presents with new-onset petechial rash following sun exposure, it is important to rule out vasculitis or thrombocytopenia as the cause, which is best achieved through skin biopsy and a platelet count, respectively. If there are no associated symptoms or thrombocytopenia and biopsy shows nonspecific vascular ectasia and erythrocyte extravasation, the physician should consider the diagnosis of idiopathic sunburn (solar or photolocalized) purpura. Along with regular UV protection, the physician should advise that the rash typically resolves without treatment in 1 to 2 weeks.

To the Editor:

Chronic UV exposure has been linked to increased skin fragility and the development of purpuric lesions, a benign condition known as actinic purpura and commonly seen in elderly patients. Petechial skin changes acutely following intense sun exposure is a rare phenomenon referred to as sunburn purpura, photolocalized purpura, or solar purpura.

A 19-year-old woman presented with red and purple spots on the pretibial region of both legs extending to the thigh. One week prior to presentation she had a severe sunburn affecting most of the body, which resolved without blistering. Two days later, the spots appeared within the most severely sunburned areas of both legs. The patient reported that the lesions were mildly painful to palpation, but she was more concerned about the appearance. She denied any history of similar skin changes associated with sun exposure. The patient was otherwise healthy and denied any recent illnesses. She noted a history of mild bruising and bleeding with a resulting unremarkable workup by her primary care physician. The only medication taken was etonogestrel-ethinyl estradiol vaginal ring.

The scalp, face, arms, trunk, and legs were examined, and nonpalpable petechial changes were noted on the anterior aspect of the legs (Figure 1), with changes more prominent on the distal aspect of the legs. Mild superficial epidermal exfoliation was noted on both anterior thighs. The area of the lesions was not warm. The lesions were mildly tender to palpation. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable.

Given the timing of onset, preceding sun exposure, and the morphologic characteristics of the lesions, sunburn purpura was suspected. A punch biopsy of the anterior aspect of the left thigh was performed to rule out vasculitis. Microscopic examination revealed reactive epidermal changes with mild vascular ectasia and erythrocyte extravasation not associated with appreciable inflammation or evidence of vascular injury (Figure 2). Biopsy exposure to fluorescein-labeled antibodies directed against IgG, IgM, IgA, C3, and polyvalent immunoglobulins (IgG, IgM, and IgA) yielded no immunofluorescence. These biopsy results were consistent with sunburn purpura. Given the patient's normal platelet count, a diagnosis of idiopathic sunburn purpura was made. The patient was informed of the biopsy results and advised that the petechiae should resolve without treatment in 1 to 2 weeks, which occurred.

Sunburn purpura remains a rare phenomenon in which a petechial or purpuric rash develops acutely after intense sun exposure. We prefer the term sunburn purpura because it reflects the acuity of the phenomenon, as opposed to the previous labels solar purpura or photolocalized purpura, which also could suggest causality from chronic sun exposure. It has been proposed that sunburn purpura is a finding associated with a number of conditions rather than a unique entity.1 The following characteristics can be helpful in describing the development of sunburn purpura: delay following UV exposure, gross morphology, histologic findings, and possible associated medical conditions.1 Our case represents an important addition to the literature, as it differs from previously reported cases. Most importantly, the nonspecific biopsy findings and unremarkable laboratory findings associated with our case may represent primary or idiopathic sunburn purpura.

Previously reported cases of sunburn purpura have occurred in patients aged 10 to 66 years. It has been seen following UV exposure, vigorous exercise and high-dose aspirin, or concurrent fluoroquinolone therapy, or in the setting of erythropoietic protoporphyria, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, or polymorphous light eruption.2-8 When performed, histology has revealed capillaritis, solar elastosis, perivascular infiltrate, lymphocytic perivascular infiltrate with dermal edema, or leukocytoclastic vasculitis.1,2,7-9 Our patient did not have a history of erythropoietic protoporphyria, polymorphous light eruption, or idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. She had not recently exercised, was not thrombocytopenic, and was not taking antiplatelet medications. She had no recent history of fluoroquinolone use. On histologic examination, our patient's biopsy demonstrated nonspecific petechial changes without signs of chronic UV exposure, dermal edema, vasculitis, lymphocytic infiltrate, or capillaritis.

Idiopathic sunburn purpura should only be diagnosed after other conditions are excluded. When evaluating a patient who presents with new-onset petechial rash following sun exposure, it is important to rule out vasculitis or thrombocytopenia as the cause, which is best achieved through skin biopsy and a platelet count, respectively. If there are no associated symptoms or thrombocytopenia and biopsy shows nonspecific vascular ectasia and erythrocyte extravasation, the physician should consider the diagnosis of idiopathic sunburn (solar or photolocalized) purpura. Along with regular UV protection, the physician should advise that the rash typically resolves without treatment in 1 to 2 weeks.

- Waters AJ, Sandhu DR, Green CM, et al. Solar capillaritis as a cause of solar purpura. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:E821-E824.

- Latenser BA, Hempstead RW. Exercise-associated solar purpura in an atypical location. Cutis. 1985;35:365-366.

- Rubegni P, Feci L, Pellegrino M, et al. Photolocalized purpura during levofloxacin therapy. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:105-107.

- Urbina F, Barrios M, Sudy E. Photolocalized purpura during ciprofloxacin therapy. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2006;22:111-112.

- Torinuki W, Miura T. Erythropoietic protoporphyria showing solar purpura. Dermatologica. 1983;167:220-222.

- Leung AK. Purpura associated with exposure to sunlight. J R Soc Med. 1986;79:423-424.

- Kalivas J, Kalivas L. Solar purpura appearing in a patient with polymorphous light eruption. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 1995;11:31-32.

- Ros AM. Solar purpura--an unusual manifestation of polymorphous light eruption. Photodermatol. 1988;5:47-48.

- Guarrera M, Parodi A, Rebora A. Solar purpura is not related to polymorphous light eruption. Photodermatol. 1989;6:293-294.

- Waters AJ, Sandhu DR, Green CM, et al. Solar capillaritis as a cause of solar purpura. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:E821-E824.

- Latenser BA, Hempstead RW. Exercise-associated solar purpura in an atypical location. Cutis. 1985;35:365-366.

- Rubegni P, Feci L, Pellegrino M, et al. Photolocalized purpura during levofloxacin therapy. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:105-107.

- Urbina F, Barrios M, Sudy E. Photolocalized purpura during ciprofloxacin therapy. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2006;22:111-112.

- Torinuki W, Miura T. Erythropoietic protoporphyria showing solar purpura. Dermatologica. 1983;167:220-222.

- Leung AK. Purpura associated with exposure to sunlight. J R Soc Med. 1986;79:423-424.

- Kalivas J, Kalivas L. Solar purpura appearing in a patient with polymorphous light eruption. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 1995;11:31-32.

- Ros AM. Solar purpura--an unusual manifestation of polymorphous light eruption. Photodermatol. 1988;5:47-48.

- Guarrera M, Parodi A, Rebora A. Solar purpura is not related to polymorphous light eruption. Photodermatol. 1989;6:293-294.

Practice Points

- Petechial skin changes acutely following intense sun exposure is a rare phenomenon referred to as sunburn purpura, photolocalized purpura, or solar purpura.

- Idiopathic sunburn purpura should only be diagnosed after vasculitis and/or thrombocytopenia is ruled out, which is best achieved through skin biopsy and a platelet count, respectively.

- The rash typically resolves without treatment in 1 to 2 weeks; however, a variety of UV protection modalities and education should be offered to the patient.

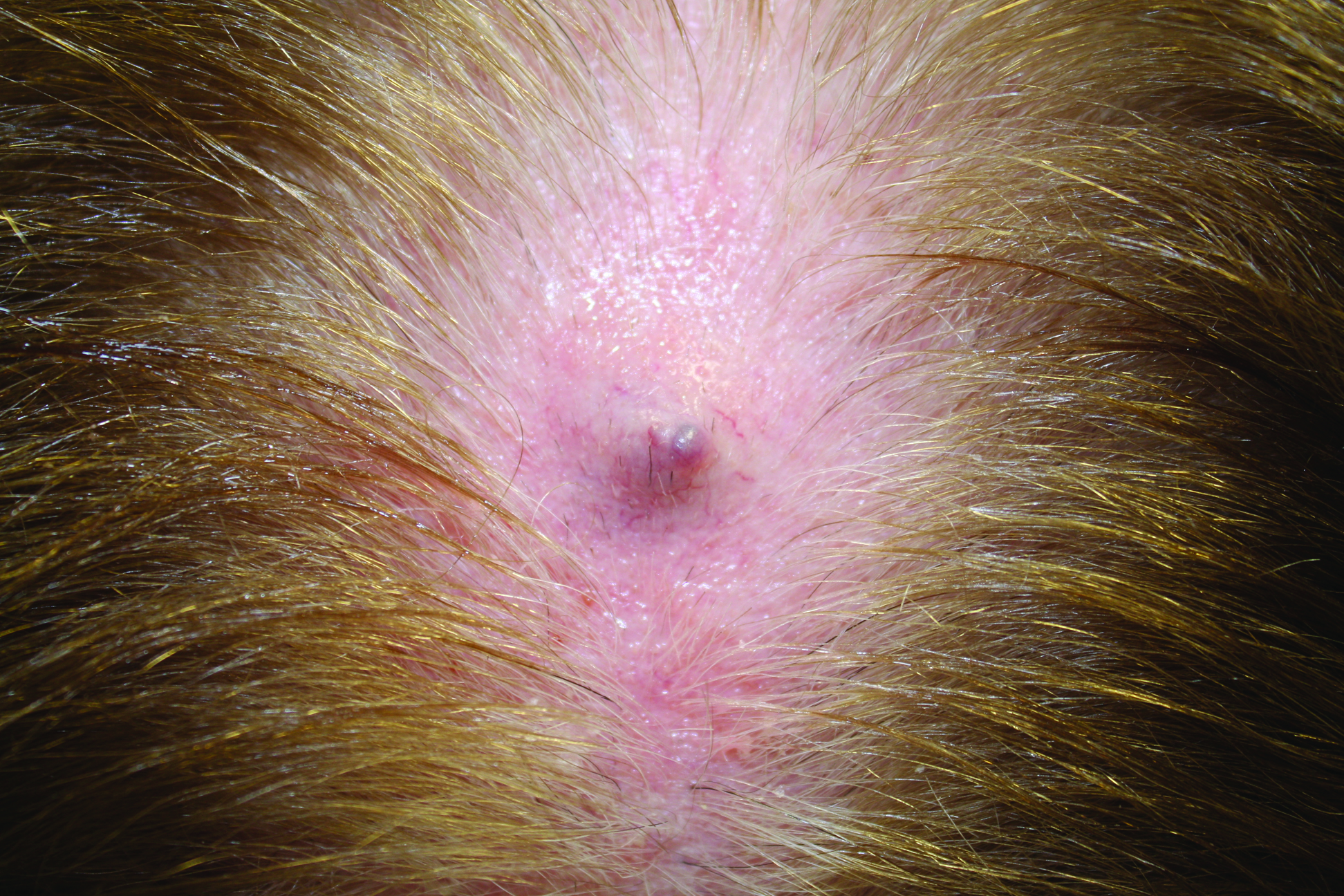

Firm Gray Nodule on the Scalp

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Mucinous Carcinoma

Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma is a rare tumor of the sweat glands that was first reported in 1952 by Lennox et al.1 These tumors are slow growing and have a predilection for the head and neck, with the eyelid being the most commonly reported location.2 In general, they present as erythematous asymptomatic nodules measuring less than 7 cm in diameter.2-4 Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma tends to have a good prognosis with complete resection, but cases of metastasis and recurrence have been reported.2 Although there is no standard of care, treatment typically consists of surgical management, as the tumors are nonresponsive to chemotherapy or radiation.4 Kamalpour et al2 compared outcomes for Mohs micrographic surgery versus standard excision, the former showing a lower percentage of poor outcomes. Of note, there were fewer cases treated with Mohs surgery in this study; only more recently reported cases have been treated with Mohs surgery.

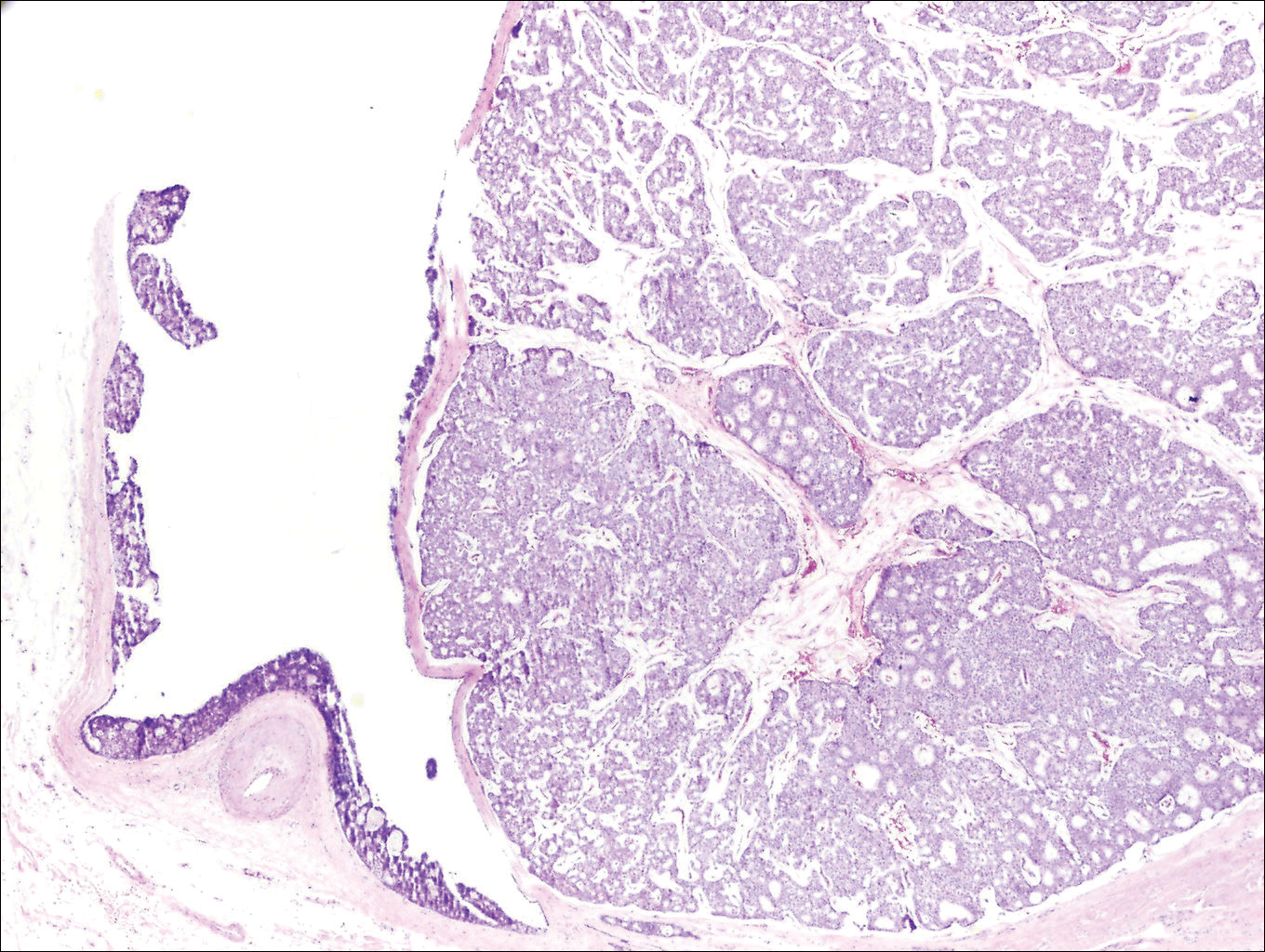

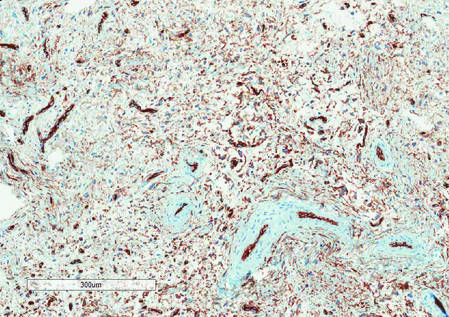

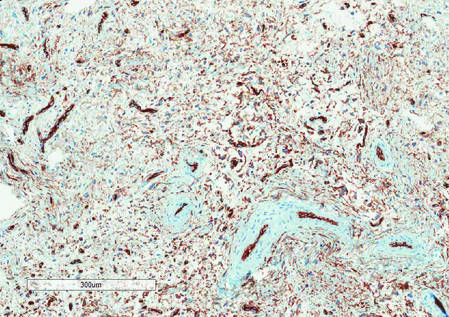

Histologically, primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma is composed of cords, tubules, and lobules of epithelial cells floating in large pools of basophilic mucin, separated by thin fibrovascular septa.5 It can be difficult to distinguish a primary tumor from a mucinous carcinoma metastasis with histology alone, especially on the breasts and in the gastrointestinal tract. Immunohistochemistry can be helpful in determining the origin of the tumor. A homologue of p53, p63 expressed in basal and myoepithelial cells of the skin can aid in the confirmation of a primary tumor when present.6,7 Negative staining for cytokeratin 20 and positive staining for cytokeratin 7 also are helpful in distinguishing a primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma from a gastrointestinal tract metastasis.4,8

In our patient, no other symptoms were present that raised concern for an internal malignancy. Findings that supported a primary versus metastatic tumor included the clinicopathologic findings (Figure) as well as positive p63, cytokeratin 7, and negative cytokeratin 20 staining. The initial standard excision had tumor cells within 1 mm of the specimen margin; thus, a subsequent wider reexcision was performed. Reexcision was negative for tumor cells. Close follow-up with a primary care physician was recommended, with emphasis on colon and breast cancer screening. A follow-up mammogram was negative for breast cancer.

- Lennox B, Pearse AG, Richards HG. Mucin-secreting tumours of the skin: with special reference to the so-called mixed-salivary tumour of the skin and its relation to hidradenoma. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1952;64:865-880.

- Kamalpour L, Brindise RT, Nodzenski M, et al. Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma a systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes after surgery. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:380-384.

- Papalas JA, Proia AD. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the eyelid: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 4 cases and an update on recurrence rates. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:1160-1165.

- Breiting L, Christensen L, Dahlstrom K, et al. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin: a population-based study. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:242-245.

- Walsh SN, Santa Cruz DJ. Adnexal carcinomas of the skin. In: Rigel DS, Robinson JK, Ross M, et al, eds. Cancer of the Skin. 2nd ed. Beijing, China: Elsevier Saunders; 2011:140-149.

- Jo VY, Fletcher CD. p63 Immunohistochemical staining is limited in soft tissue tumors. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;136:762-766.

- Ivan D, Nash JW, Prieto VG, et al. Use of p63 expression in distinguishing primary and metastatic cutaneous adnexal neoplasms from metastatic adenocarcinoma to skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;34:478-489.

- Kazakov DV, Suster S, LeBoit PE, et al. Mucinous carcinoma of the skin, primary, and secondary: a clinicopathologic study of 63 cases with emphasis on the morphologic spectrum of primary cutaneous forms: homologies with mucinous lesions in the breast. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:764-782.

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Mucinous Carcinoma

Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma is a rare tumor of the sweat glands that was first reported in 1952 by Lennox et al.1 These tumors are slow growing and have a predilection for the head and neck, with the eyelid being the most commonly reported location.2 In general, they present as erythematous asymptomatic nodules measuring less than 7 cm in diameter.2-4 Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma tends to have a good prognosis with complete resection, but cases of metastasis and recurrence have been reported.2 Although there is no standard of care, treatment typically consists of surgical management, as the tumors are nonresponsive to chemotherapy or radiation.4 Kamalpour et al2 compared outcomes for Mohs micrographic surgery versus standard excision, the former showing a lower percentage of poor outcomes. Of note, there were fewer cases treated with Mohs surgery in this study; only more recently reported cases have been treated with Mohs surgery.

Histologically, primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma is composed of cords, tubules, and lobules of epithelial cells floating in large pools of basophilic mucin, separated by thin fibrovascular septa.5 It can be difficult to distinguish a primary tumor from a mucinous carcinoma metastasis with histology alone, especially on the breasts and in the gastrointestinal tract. Immunohistochemistry can be helpful in determining the origin of the tumor. A homologue of p53, p63 expressed in basal and myoepithelial cells of the skin can aid in the confirmation of a primary tumor when present.6,7 Negative staining for cytokeratin 20 and positive staining for cytokeratin 7 also are helpful in distinguishing a primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma from a gastrointestinal tract metastasis.4,8

In our patient, no other symptoms were present that raised concern for an internal malignancy. Findings that supported a primary versus metastatic tumor included the clinicopathologic findings (Figure) as well as positive p63, cytokeratin 7, and negative cytokeratin 20 staining. The initial standard excision had tumor cells within 1 mm of the specimen margin; thus, a subsequent wider reexcision was performed. Reexcision was negative for tumor cells. Close follow-up with a primary care physician was recommended, with emphasis on colon and breast cancer screening. A follow-up mammogram was negative for breast cancer.

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Mucinous Carcinoma

Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma is a rare tumor of the sweat glands that was first reported in 1952 by Lennox et al.1 These tumors are slow growing and have a predilection for the head and neck, with the eyelid being the most commonly reported location.2 In general, they present as erythematous asymptomatic nodules measuring less than 7 cm in diameter.2-4 Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma tends to have a good prognosis with complete resection, but cases of metastasis and recurrence have been reported.2 Although there is no standard of care, treatment typically consists of surgical management, as the tumors are nonresponsive to chemotherapy or radiation.4 Kamalpour et al2 compared outcomes for Mohs micrographic surgery versus standard excision, the former showing a lower percentage of poor outcomes. Of note, there were fewer cases treated with Mohs surgery in this study; only more recently reported cases have been treated with Mohs surgery.

Histologically, primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma is composed of cords, tubules, and lobules of epithelial cells floating in large pools of basophilic mucin, separated by thin fibrovascular septa.5 It can be difficult to distinguish a primary tumor from a mucinous carcinoma metastasis with histology alone, especially on the breasts and in the gastrointestinal tract. Immunohistochemistry can be helpful in determining the origin of the tumor. A homologue of p53, p63 expressed in basal and myoepithelial cells of the skin can aid in the confirmation of a primary tumor when present.6,7 Negative staining for cytokeratin 20 and positive staining for cytokeratin 7 also are helpful in distinguishing a primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma from a gastrointestinal tract metastasis.4,8

In our patient, no other symptoms were present that raised concern for an internal malignancy. Findings that supported a primary versus metastatic tumor included the clinicopathologic findings (Figure) as well as positive p63, cytokeratin 7, and negative cytokeratin 20 staining. The initial standard excision had tumor cells within 1 mm of the specimen margin; thus, a subsequent wider reexcision was performed. Reexcision was negative for tumor cells. Close follow-up with a primary care physician was recommended, with emphasis on colon and breast cancer screening. A follow-up mammogram was negative for breast cancer.

- Lennox B, Pearse AG, Richards HG. Mucin-secreting tumours of the skin: with special reference to the so-called mixed-salivary tumour of the skin and its relation to hidradenoma. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1952;64:865-880.

- Kamalpour L, Brindise RT, Nodzenski M, et al. Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma a systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes after surgery. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:380-384.

- Papalas JA, Proia AD. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the eyelid: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 4 cases and an update on recurrence rates. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:1160-1165.

- Breiting L, Christensen L, Dahlstrom K, et al. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin: a population-based study. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:242-245.

- Walsh SN, Santa Cruz DJ. Adnexal carcinomas of the skin. In: Rigel DS, Robinson JK, Ross M, et al, eds. Cancer of the Skin. 2nd ed. Beijing, China: Elsevier Saunders; 2011:140-149.

- Jo VY, Fletcher CD. p63 Immunohistochemical staining is limited in soft tissue tumors. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;136:762-766.

- Ivan D, Nash JW, Prieto VG, et al. Use of p63 expression in distinguishing primary and metastatic cutaneous adnexal neoplasms from metastatic adenocarcinoma to skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;34:478-489.

- Kazakov DV, Suster S, LeBoit PE, et al. Mucinous carcinoma of the skin, primary, and secondary: a clinicopathologic study of 63 cases with emphasis on the morphologic spectrum of primary cutaneous forms: homologies with mucinous lesions in the breast. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:764-782.

- Lennox B, Pearse AG, Richards HG. Mucin-secreting tumours of the skin: with special reference to the so-called mixed-salivary tumour of the skin and its relation to hidradenoma. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1952;64:865-880.

- Kamalpour L, Brindise RT, Nodzenski M, et al. Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma a systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes after surgery. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:380-384.

- Papalas JA, Proia AD. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the eyelid: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 4 cases and an update on recurrence rates. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:1160-1165.

- Breiting L, Christensen L, Dahlstrom K, et al. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin: a population-based study. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:242-245.

- Walsh SN, Santa Cruz DJ. Adnexal carcinomas of the skin. In: Rigel DS, Robinson JK, Ross M, et al, eds. Cancer of the Skin. 2nd ed. Beijing, China: Elsevier Saunders; 2011:140-149.

- Jo VY, Fletcher CD. p63 Immunohistochemical staining is limited in soft tissue tumors. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;136:762-766.

- Ivan D, Nash JW, Prieto VG, et al. Use of p63 expression in distinguishing primary and metastatic cutaneous adnexal neoplasms from metastatic adenocarcinoma to skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;34:478-489.

- Kazakov DV, Suster S, LeBoit PE, et al. Mucinous carcinoma of the skin, primary, and secondary: a clinicopathologic study of 63 cases with emphasis on the morphologic spectrum of primary cutaneous forms: homologies with mucinous lesions in the breast. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:764-782.

Toe Nodule Obliterating the Nail Bed

The Diagnosis: Superficial Acral Fibromyxoma

Superficial acral fibromyxoma (SAF) was first described in 2001 by Fetsch et al.1 Subsequently, the term digital fibromyxoma was proposed in 2012 by Hollmann et al2 to describe a distinctive, slow-growing, soft-tissue tumor with a predilection for the periungual or subungual regions of the fingers and toes. The benign growth typically presents as a painless or tender nodule in middle-aged adults with a slight male predominance (1.3:1 ratio).1,2 In a case series (N=124) described by Hollmann et al,2 9 of 25 patients (36%) who had imaging studies showed bone involvement by an erosive or lytic lesion. Reports of SAF with bone involvement also have been described in the radiologic and orthopedic surgery literature.3,4 Radiographically, the soft-tissue invasion of the bone is demonstrated by scalloping on plain radiographs (Figure 1).3

Histologically, SAFs are moderately cellular with spindled or stellate fibroblastlike cells within a myxoid or collagenous matrix (Figure 2).1 The vasculature is mildly accentuated and an increase in mast cells usually is observed. The nuclei have a low degree of atypia with few mitotic figures, and the stellate cells exhibit positive immunohistochemical staining for CD34 (Figure 3), epithelial membrane antigen, and CD99.1 Hollmann et al2 found that 66 of 95 tumors (69.5%) infiltrated the dermal collagen, 26 (27.4%) infiltrated fat, and 3 (3.2%) invaded bone. Of the 47 cases that were evaluated on follow-up, 10 tumors (21.3%) recurred locally (all near the nail unit of the fingers or toes) after a mean interval of 27 months. Although invasion of underlying tissues and recurrence of the tumor has been demonstrated, this growth is considered benign. The histologic differential diagnosis includes neurofibroma, myxoma, fibroma, low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma, dermatofibroma, superficial angiomyxoma, and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans.2

The primary treatment of SAF is local excision. The incidence of local recurrence found in the case series by Hollmann et al2 was directly linked to positive margins after the first excision (10/47 [21.3%] recurrent lesions had positive margins). To date, there are no known reports of metastatic disease in SAF.2 Our case manifested with a late recurrence of the tumor and bone involvement requiring surgical excision, which illustrates the role of adjuvant imaging and close follow-up following excision of any soft-tissue tumors of the fingers and toes that have been histologically confirmed as SAF, particularly those of the periungual region.

|

|

|

|

1. Fetsch JF, Laskin WB, Miettinen M. Superficial acral fibromyxoma (a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 37 cases of a distinctive soft tissue tumor with a predilection for the fingers and toes.) Hum Pathol. 2001;32:704-714.

2. Hollmann TJ, Bovée JV, Fletcher CD. Digital fibromyxoma (superficial acral fibromyxoma): a detailed characterization of 124 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:789-798.

3. Varikatt W, Soper J, Simmon G, et al. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: a report of two cases with radiological findings. Skeletal Radiol. 2008;37:499-503.

4. Oteo-Alvaro A, Meizoso T, Scarpellini A, et al. Superficial acral fibromyxoma of the toe, with erosion of the distal phalanx. a clinical report. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2008;128:271-274.

The Diagnosis: Superficial Acral Fibromyxoma

Superficial acral fibromyxoma (SAF) was first described in 2001 by Fetsch et al.1 Subsequently, the term digital fibromyxoma was proposed in 2012 by Hollmann et al2 to describe a distinctive, slow-growing, soft-tissue tumor with a predilection for the periungual or subungual regions of the fingers and toes. The benign growth typically presents as a painless or tender nodule in middle-aged adults with a slight male predominance (1.3:1 ratio).1,2 In a case series (N=124) described by Hollmann et al,2 9 of 25 patients (36%) who had imaging studies showed bone involvement by an erosive or lytic lesion. Reports of SAF with bone involvement also have been described in the radiologic and orthopedic surgery literature.3,4 Radiographically, the soft-tissue invasion of the bone is demonstrated by scalloping on plain radiographs (Figure 1).3

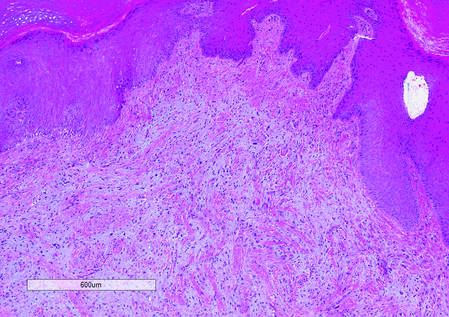

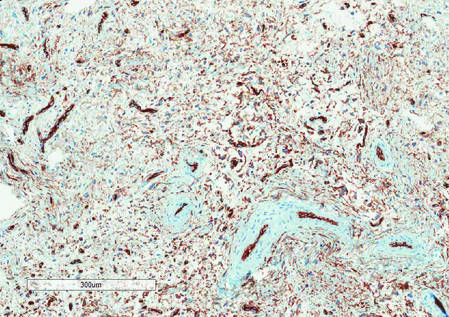

Histologically, SAFs are moderately cellular with spindled or stellate fibroblastlike cells within a myxoid or collagenous matrix (Figure 2).1 The vasculature is mildly accentuated and an increase in mast cells usually is observed. The nuclei have a low degree of atypia with few mitotic figures, and the stellate cells exhibit positive immunohistochemical staining for CD34 (Figure 3), epithelial membrane antigen, and CD99.1 Hollmann et al2 found that 66 of 95 tumors (69.5%) infiltrated the dermal collagen, 26 (27.4%) infiltrated fat, and 3 (3.2%) invaded bone. Of the 47 cases that were evaluated on follow-up, 10 tumors (21.3%) recurred locally (all near the nail unit of the fingers or toes) after a mean interval of 27 months. Although invasion of underlying tissues and recurrence of the tumor has been demonstrated, this growth is considered benign. The histologic differential diagnosis includes neurofibroma, myxoma, fibroma, low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma, dermatofibroma, superficial angiomyxoma, and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans.2

The primary treatment of SAF is local excision. The incidence of local recurrence found in the case series by Hollmann et al2 was directly linked to positive margins after the first excision (10/47 [21.3%] recurrent lesions had positive margins). To date, there are no known reports of metastatic disease in SAF.2 Our case manifested with a late recurrence of the tumor and bone involvement requiring surgical excision, which illustrates the role of adjuvant imaging and close follow-up following excision of any soft-tissue tumors of the fingers and toes that have been histologically confirmed as SAF, particularly those of the periungual region.

|

|

|

|

The Diagnosis: Superficial Acral Fibromyxoma

Superficial acral fibromyxoma (SAF) was first described in 2001 by Fetsch et al.1 Subsequently, the term digital fibromyxoma was proposed in 2012 by Hollmann et al2 to describe a distinctive, slow-growing, soft-tissue tumor with a predilection for the periungual or subungual regions of the fingers and toes. The benign growth typically presents as a painless or tender nodule in middle-aged adults with a slight male predominance (1.3:1 ratio).1,2 In a case series (N=124) described by Hollmann et al,2 9 of 25 patients (36%) who had imaging studies showed bone involvement by an erosive or lytic lesion. Reports of SAF with bone involvement also have been described in the radiologic and orthopedic surgery literature.3,4 Radiographically, the soft-tissue invasion of the bone is demonstrated by scalloping on plain radiographs (Figure 1).3

Histologically, SAFs are moderately cellular with spindled or stellate fibroblastlike cells within a myxoid or collagenous matrix (Figure 2).1 The vasculature is mildly accentuated and an increase in mast cells usually is observed. The nuclei have a low degree of atypia with few mitotic figures, and the stellate cells exhibit positive immunohistochemical staining for CD34 (Figure 3), epithelial membrane antigen, and CD99.1 Hollmann et al2 found that 66 of 95 tumors (69.5%) infiltrated the dermal collagen, 26 (27.4%) infiltrated fat, and 3 (3.2%) invaded bone. Of the 47 cases that were evaluated on follow-up, 10 tumors (21.3%) recurred locally (all near the nail unit of the fingers or toes) after a mean interval of 27 months. Although invasion of underlying tissues and recurrence of the tumor has been demonstrated, this growth is considered benign. The histologic differential diagnosis includes neurofibroma, myxoma, fibroma, low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma, dermatofibroma, superficial angiomyxoma, and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans.2

The primary treatment of SAF is local excision. The incidence of local recurrence found in the case series by Hollmann et al2 was directly linked to positive margins after the first excision (10/47 [21.3%] recurrent lesions had positive margins). To date, there are no known reports of metastatic disease in SAF.2 Our case manifested with a late recurrence of the tumor and bone involvement requiring surgical excision, which illustrates the role of adjuvant imaging and close follow-up following excision of any soft-tissue tumors of the fingers and toes that have been histologically confirmed as SAF, particularly those of the periungual region.

|

|

|

|

1. Fetsch JF, Laskin WB, Miettinen M. Superficial acral fibromyxoma (a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 37 cases of a distinctive soft tissue tumor with a predilection for the fingers and toes.) Hum Pathol. 2001;32:704-714.

2. Hollmann TJ, Bovée JV, Fletcher CD. Digital fibromyxoma (superficial acral fibromyxoma): a detailed characterization of 124 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:789-798.

3. Varikatt W, Soper J, Simmon G, et al. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: a report of two cases with radiological findings. Skeletal Radiol. 2008;37:499-503.

4. Oteo-Alvaro A, Meizoso T, Scarpellini A, et al. Superficial acral fibromyxoma of the toe, with erosion of the distal phalanx. a clinical report. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2008;128:271-274.

1. Fetsch JF, Laskin WB, Miettinen M. Superficial acral fibromyxoma (a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 37 cases of a distinctive soft tissue tumor with a predilection for the fingers and toes.) Hum Pathol. 2001;32:704-714.

2. Hollmann TJ, Bovée JV, Fletcher CD. Digital fibromyxoma (superficial acral fibromyxoma): a detailed characterization of 124 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:789-798.

3. Varikatt W, Soper J, Simmon G, et al. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: a report of two cases with radiological findings. Skeletal Radiol. 2008;37:499-503.

4. Oteo-Alvaro A, Meizoso T, Scarpellini A, et al. Superficial acral fibromyxoma of the toe, with erosion of the distal phalanx. a clinical report. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2008;128:271-274.

A generally healthy 30-year-old man presented with a 3-cm exophytic, yellowish red, subungual nodule of the left great toe of 1 year’s duration that was obliterating the nail plate. Ten years prior, a similar nodule in the same location was removed via laser by a podiatrist. Medical records were not retrievable, but the patient reported that he was told the excised lesion was a benign tumor. Plain radiographs were performed at the current presentation and demonstrated an inferior cortical lucency of the distal phalanx as well as a lucency over the nail bed region with extension of calcification to the soft tissues. Magnetic resonance imaging showed a mass with a proximal to distal maximum dimension of 2.1 cm that involved the dorsal surface of the proximal phalanx. Magnetic resonance imaging also demonstrated bone erosion from the overlying mass. A 4-mm incisional punch biopsy was performed prior to surgical excision.