User login

Patient and Care Team Perspectives of Telemedicine in Critical Access Hospitals

Healthcare delivery in rural America faces unique, growing challenges related to health and emergency care access.1 Telemedicine approaches have the potential to increase rural hospitals’ ability to deliver efficient emergency care and reduce clinician shortages.2 While initial evidence of telemedicine success exists, more quality research is needed to understand telemedicine patient and care team experiences,3 especially with real-time, clinician-initiated video conferencing in critical access hospital (CAH) emergency departments (ED). Some experience studies exist,4 but results are primarily quantitative5 and lack the nuanced qualitative depth needed to understand topics such as satisfaction and communication.6 Additionally, few explore combined patient and care team perspectives.5 The lack of breadth and depth makes it difficult to provide actionable recommendations for improvements and affects the feasibility of continuing this work and improving telemedicine care quality. To address these gaps, we evaluated a real-time, clinician-initiated video conferencing program with overnight clinicians servicing ED patients in three Midwestern care system CAHs. This evaluation assessed patient and care team (nurse and clinician) experience with telemedicine using quantitative and qualitative survey data analysis.

METHODS

Because this evaluation was designed to measure and improve program quality in a single healthcare system, it was deemed non-human subjects research by the organization’s institutional review board. This brief report follows telemedicine reporting guidelines.7

Setting and Telemedicine Program

This program, designed to reduce the need for on-call hospitalist clinicians to be onsite at CAHs overnight, was implemented in a large Midwestern nonprofit integrated healthcare system with three rural CAHs (combined capacity for 75 inpatient admissions, with full-time onsite ED clinicians and nurses, as well as on-call hospitalist clinicians) and a large metropolitan tertiary-care hospital. All adult patients presenting to CAH EDs between 6

Following a pilot period, the full-scale program was implemented in September 2017 and included 14 remote clinicians and 60 onsite nurses.

Survey Administration and Design

A postimplementation survey was designed to explore patient and care team experience with telemedicine. Patients who received a telemedicine visit between September 2017 and April 2018 were mailed a paper survey. Nonresponders were called by professional interviewers affiliated with the healthcare system. All participating clinicians (N = 14, all MDs) and nurses (N = 60, all RNs) were emailed an online care team survey with phone-in option. Care team nonresponders were sent up to two reminder emails.

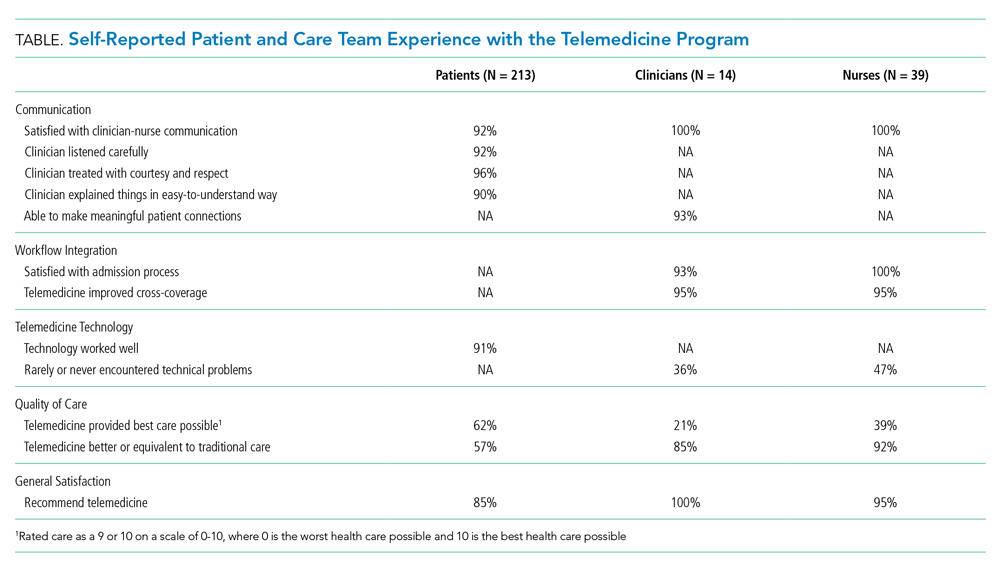

Surveys captured the following five constructs: communication, workflow integration, telemedicine technology, quality of care, and general satisfaction. Existing questionnaires were used where possible; additional items were designed with clinical experts following survey design best practices.8 Patient-perceived communication was assessed via three Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems Outpatient and Ambulatory Surgery Survey items.9 Five additional program-developed patient survey items included satisfaction with clinician-nurse communication, satisfaction with technology, telemedicine quality of care overall and in comparison with traditional care, and whether or not patients would recommend telemedicine (Table). Four open-ended questions asked patients about improvement opportunities and general satisfaction.

Care team surveys included two items regarding ability to effectively communicate, two about satisfaction with workflow integration, one about technical problems, two about quality of care, and one about general satisfaction. Open-ended questions gathered further information and recommendations to improve communication, workflow integration, technology issues, and general satisfaction.

Analysis

Closed-ended items were dichotomized (satisfied yes/no); descriptive statistics (frequencies/percents) are presented to quantify patient and care team experience. Quantitative analyses were conducted in SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). Open-ended responses were coded separately for patient and care team experience, following qualitative content analysis best practices.10 A lead coder read all responses, created a coding framework of identified themes, and coded individual responses. A second coder independently coded responses using the same framework. Interrater reliability was calculated for each major theme using percent agreement and prevalence- and bias-adjusted

RESULTS

Of eligible patients mailed a survey (N = 408), 3% self-reported as ineligible, and 54% completed the survey. This is a maximum response rate (response rate 6) according to the American Association for Public Opinion Research.12 Patients were 67 years old on average (SD = 15), they were primarily white (97%), and 54% were female. All clinicians and 63% of nurses completed the survey.12 Clinicians and nurses were 29% and 95% female, respectively.

Quantitative results (Table) show generally positive experience across patient and care team respondents. Over 90% were satisfied with all measures of communication. Care teams had high satisfaction with admissions processes and reported telemedicine improved cross-coverage. Patient-reported technology experience was positive but was less positive from the care team perspective. Care teams reported lower absolute quality of care than did patients but were more likely to perceive telemedicine as high quality, compared with traditional care. Most patients, clinicians, and nurses would recommend telemedicine.

Qualitatively, four major themes were identified in open-ended responses with high interrater reliability (PABAK ranging from 0.92 to 0.98 in patient responses and 0.88 to 0.95 in care team responses) and aligned with the quantitative survey constructs: clinician-nurse communication, clinician-patient communication, workflow integration, and telemedicine technology. Patients reported satisfaction with communication with remote clinicians:

“[The clinician] was extremely attentive to me and what was going on. She was articulate and clear. I understood what was going to happen.” –Patient

Care teams suggested concrete improvement opportunities:

“I’d prefer to have some time with nursing staff both before and (sometimes) after the patient encounter.” –Clinician

“Since we cannot hear what [the clinicians] are hearing with the stethoscope, it’s nice when they tell us when to move it to the next spot.” –Nurse

Clinicians and nurses gave favorable responses regarding workflow integration, though time (both admissions wait time and session duration) was a reported opportunity:

“It would be helpful if we could speed up the time from admit request to screen time.” –Clinician

“When the [clinicians] get swamped, they’re hard to get a hold of, and admissions can take a long time. They may have too much on their plates dealing with several locations.” –Nurse

Technology issues—internet connection, stethoscope, sound, and screen or camera—were mentioned by patients and care teams, though technology was reviewed favorably overall by most patients:

“I was fascinated by the technology. Visiting someone over a television was impressive. ... The picture, the sound clarity, and the connection itself was flawless.” –Patient

Some patients commented that telemedicine was the best option given the situation, but still preferred an in-person doctor:

“If a doctor wasn’t available, telemedicine is better than nothing.” –Patient

Nurses who would not recommend telemedicine noted the need for personal connection:

“[I] still prefer [an] in-person MD for more personal contact. The older patients often state they wish the doctor would come and see them.” –Nurse

Patients who would not recommend telemedicine also desired personal connection:

“I would sooner talk to a person than a machine.” –Patient

A few clinicians noted the connection with patients would be improved if they knew about others in the room:

“It’d be nice if everyone in the room was introduced. Sometimes people are sitting out of view of the camera and I don’t realize they’re there until later.” –Clinician

CONCLUSION

These results make important contributions to understanding and improving the telemedicine experience in rural emergency hospital medicine. While the predominantly white patient respondent population limits generalizability, these demographics are representative of the overall population of the participating hospitals. A strength of this evaluation is its contemporaneous consideration of patient and care team experience with both quantitative and rich, qualitative analysis. Patients and care teams alike thought overnight telemedicine was better than the status quo. While our quality of care findings align with some previous literature,13 care teams in the current analysis overwhelmingly would recommend telemedicine, whereas some clinicians in prior work would not recommend telemedicine.14

In terms of communication, in line with existing literature, some patients still preferred in-person visits,15 a view also shared by some care team members. Workflow and technology barriers were raised, corroborating existing work,13 but actionable solutions (eg, adding care team–only time before visits or verbalizing when to move stethoscopes) were also identified.

Embedding patient and care team experience surveys and sharing results is critical in advancing telemedicine. Findings from this evaluation strengthen the case for payer reimbursement of telemedicine in rural acute care. Continued work to improve, test, and publish findings on patient and care team experience with telemedicine is critical to providing quality services in often-underserved communities.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Ann Werner in identifying the patient survey sample, Brian Barklind in identifying source data for the analysis, and both Brian Barklind and Rachael Rivard for conducting the analyses and summarizing results. We would also like to thank Kelly Logue for her involvement in conceptualizing the telemedicine evaluation described here, as well as Larisa Polynskaya for her help preparing the manuscript for publication, and the care teams and patients who provided valuable input.

1. Nelson R. Will rural community hospitals survive? Am J Nurs. 2017;117(9):18-19. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000524538.11040.7f.

2. Ward MM, Merchant KAS, Carter KD, et al. Use of telemedicine for ED physician coverage in critical access hospitals increased after CMS policy clarification. Health Aff. 2018;37(12):2037-2044. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05103.

3. AlDossary S, Martin-Khan MG, Bradford NK, Smith AC. A systematic review of the methodologies used to evaluate telemedicine service initiatives in hospital facilities. Int J Med Inf. 2017;97:171-194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2016.10.012.

4. Kuperman EF, Linson EL, Klefstad K, Perry E, Glenn K. The virtual hospitalist: a single-site implementation bringing hospitalist coverage to critical access hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(11):759-763. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3061.

5. Garcia R, Adelakun OA. A review of patient and provider satisfaction with telemedicine. Paper presented at: Twenty-third Americas Conference on Information Systems; 2017; Boston, Massachusetts.

6. Mair F, Whitten P. Systematic review of studies of patient satisfaction with telemedicine. BMJ. 2000;320(7248):1517-1520. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7248.1517.

7. Khanal S, Burgon J, Leonard S, Griffiths M, Eddowes LA. Recommendations for the improved effectiveness and reporting of telemedicine programs in developing countries: results of a systematic literature review. Telemed E Health. 2015;21(11):903-915. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2014.0194.

8. Fowler Jr FJ. Improving survey questions: Design and evaluation. Vol 38. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, Inc.; 1995.

9. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. CAHPS Outpatient and Ambulatory Surgery Survey. https://www.ahrq.gov/cahps/surveys-guidance/oas/index.html. Accessed August 1, 2017.

10. Ulin PR, Robinson ET, Tolley EE. Qualitative methods in public health: A field guide for applied research. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 2005.

11. Corden A, Sainsbury R. Using verbatim quotations in reporting qualitative social research: researches’ views. York, United Kingdom: University of York; 2006.

12. American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. 2016. https://www.aapor.org/AAPOR_Main/media/publications/Standard-Definitions20169theditionfinal.pdf. Accessed August 1, 2019.

13. Mueller KJ, Potter AJ, MacKinney AC, Ward MM. Lessons from tele-emergency: improving care quality and health outcomes by expanding support for rural care systems. Health Aff. 2014;33(2):228-234. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1016.

14. Fairchild R, Kuo SFF, Laws S, O’Brien A, Rahmouni H. Perceptions of rural emergency department providers regarding telehealth-based care: perceived competency, satisfaction with care and Tele-ED patient disposition. Open J Nurs. 2017;7(07):721. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojn.2017.77054.

15. Weatherburn G, Dowie R, Mistry H, Young T. An assessment of parental satisfaction with mode of delivery of specialist advice for paediatric cardiology: face-to-face versus videoconference. J Telemed Telecare. 2006;12(suppl 1):57-59. https://doi.org/10.1258/135763306777978560.

Healthcare delivery in rural America faces unique, growing challenges related to health and emergency care access.1 Telemedicine approaches have the potential to increase rural hospitals’ ability to deliver efficient emergency care and reduce clinician shortages.2 While initial evidence of telemedicine success exists, more quality research is needed to understand telemedicine patient and care team experiences,3 especially with real-time, clinician-initiated video conferencing in critical access hospital (CAH) emergency departments (ED). Some experience studies exist,4 but results are primarily quantitative5 and lack the nuanced qualitative depth needed to understand topics such as satisfaction and communication.6 Additionally, few explore combined patient and care team perspectives.5 The lack of breadth and depth makes it difficult to provide actionable recommendations for improvements and affects the feasibility of continuing this work and improving telemedicine care quality. To address these gaps, we evaluated a real-time, clinician-initiated video conferencing program with overnight clinicians servicing ED patients in three Midwestern care system CAHs. This evaluation assessed patient and care team (nurse and clinician) experience with telemedicine using quantitative and qualitative survey data analysis.

METHODS

Because this evaluation was designed to measure and improve program quality in a single healthcare system, it was deemed non-human subjects research by the organization’s institutional review board. This brief report follows telemedicine reporting guidelines.7

Setting and Telemedicine Program

This program, designed to reduce the need for on-call hospitalist clinicians to be onsite at CAHs overnight, was implemented in a large Midwestern nonprofit integrated healthcare system with three rural CAHs (combined capacity for 75 inpatient admissions, with full-time onsite ED clinicians and nurses, as well as on-call hospitalist clinicians) and a large metropolitan tertiary-care hospital. All adult patients presenting to CAH EDs between 6

Following a pilot period, the full-scale program was implemented in September 2017 and included 14 remote clinicians and 60 onsite nurses.

Survey Administration and Design

A postimplementation survey was designed to explore patient and care team experience with telemedicine. Patients who received a telemedicine visit between September 2017 and April 2018 were mailed a paper survey. Nonresponders were called by professional interviewers affiliated with the healthcare system. All participating clinicians (N = 14, all MDs) and nurses (N = 60, all RNs) were emailed an online care team survey with phone-in option. Care team nonresponders were sent up to two reminder emails.

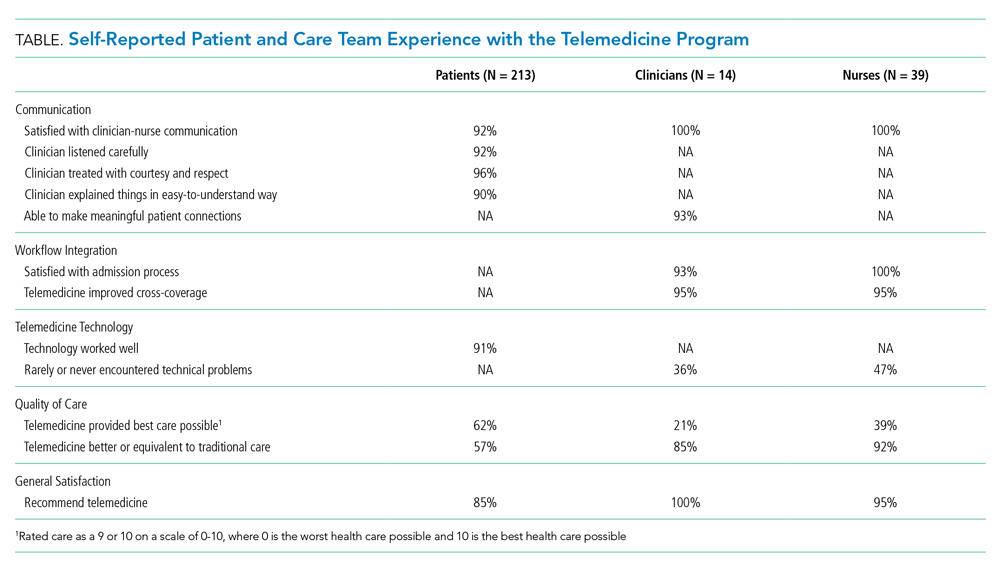

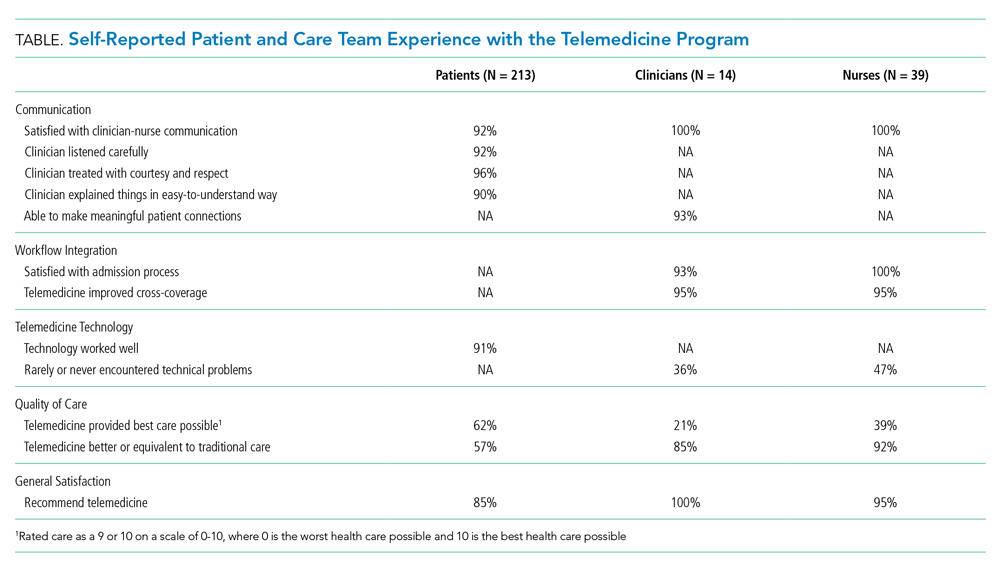

Surveys captured the following five constructs: communication, workflow integration, telemedicine technology, quality of care, and general satisfaction. Existing questionnaires were used where possible; additional items were designed with clinical experts following survey design best practices.8 Patient-perceived communication was assessed via three Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems Outpatient and Ambulatory Surgery Survey items.9 Five additional program-developed patient survey items included satisfaction with clinician-nurse communication, satisfaction with technology, telemedicine quality of care overall and in comparison with traditional care, and whether or not patients would recommend telemedicine (Table). Four open-ended questions asked patients about improvement opportunities and general satisfaction.

Care team surveys included two items regarding ability to effectively communicate, two about satisfaction with workflow integration, one about technical problems, two about quality of care, and one about general satisfaction. Open-ended questions gathered further information and recommendations to improve communication, workflow integration, technology issues, and general satisfaction.

Analysis

Closed-ended items were dichotomized (satisfied yes/no); descriptive statistics (frequencies/percents) are presented to quantify patient and care team experience. Quantitative analyses were conducted in SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). Open-ended responses were coded separately for patient and care team experience, following qualitative content analysis best practices.10 A lead coder read all responses, created a coding framework of identified themes, and coded individual responses. A second coder independently coded responses using the same framework. Interrater reliability was calculated for each major theme using percent agreement and prevalence- and bias-adjusted

RESULTS

Of eligible patients mailed a survey (N = 408), 3% self-reported as ineligible, and 54% completed the survey. This is a maximum response rate (response rate 6) according to the American Association for Public Opinion Research.12 Patients were 67 years old on average (SD = 15), they were primarily white (97%), and 54% were female. All clinicians and 63% of nurses completed the survey.12 Clinicians and nurses were 29% and 95% female, respectively.

Quantitative results (Table) show generally positive experience across patient and care team respondents. Over 90% were satisfied with all measures of communication. Care teams had high satisfaction with admissions processes and reported telemedicine improved cross-coverage. Patient-reported technology experience was positive but was less positive from the care team perspective. Care teams reported lower absolute quality of care than did patients but were more likely to perceive telemedicine as high quality, compared with traditional care. Most patients, clinicians, and nurses would recommend telemedicine.

Qualitatively, four major themes were identified in open-ended responses with high interrater reliability (PABAK ranging from 0.92 to 0.98 in patient responses and 0.88 to 0.95 in care team responses) and aligned with the quantitative survey constructs: clinician-nurse communication, clinician-patient communication, workflow integration, and telemedicine technology. Patients reported satisfaction with communication with remote clinicians:

“[The clinician] was extremely attentive to me and what was going on. She was articulate and clear. I understood what was going to happen.” –Patient

Care teams suggested concrete improvement opportunities:

“I’d prefer to have some time with nursing staff both before and (sometimes) after the patient encounter.” –Clinician

“Since we cannot hear what [the clinicians] are hearing with the stethoscope, it’s nice when they tell us when to move it to the next spot.” –Nurse

Clinicians and nurses gave favorable responses regarding workflow integration, though time (both admissions wait time and session duration) was a reported opportunity:

“It would be helpful if we could speed up the time from admit request to screen time.” –Clinician

“When the [clinicians] get swamped, they’re hard to get a hold of, and admissions can take a long time. They may have too much on their plates dealing with several locations.” –Nurse

Technology issues—internet connection, stethoscope, sound, and screen or camera—were mentioned by patients and care teams, though technology was reviewed favorably overall by most patients:

“I was fascinated by the technology. Visiting someone over a television was impressive. ... The picture, the sound clarity, and the connection itself was flawless.” –Patient

Some patients commented that telemedicine was the best option given the situation, but still preferred an in-person doctor:

“If a doctor wasn’t available, telemedicine is better than nothing.” –Patient

Nurses who would not recommend telemedicine noted the need for personal connection:

“[I] still prefer [an] in-person MD for more personal contact. The older patients often state they wish the doctor would come and see them.” –Nurse

Patients who would not recommend telemedicine also desired personal connection:

“I would sooner talk to a person than a machine.” –Patient

A few clinicians noted the connection with patients would be improved if they knew about others in the room:

“It’d be nice if everyone in the room was introduced. Sometimes people are sitting out of view of the camera and I don’t realize they’re there until later.” –Clinician

CONCLUSION

These results make important contributions to understanding and improving the telemedicine experience in rural emergency hospital medicine. While the predominantly white patient respondent population limits generalizability, these demographics are representative of the overall population of the participating hospitals. A strength of this evaluation is its contemporaneous consideration of patient and care team experience with both quantitative and rich, qualitative analysis. Patients and care teams alike thought overnight telemedicine was better than the status quo. While our quality of care findings align with some previous literature,13 care teams in the current analysis overwhelmingly would recommend telemedicine, whereas some clinicians in prior work would not recommend telemedicine.14

In terms of communication, in line with existing literature, some patients still preferred in-person visits,15 a view also shared by some care team members. Workflow and technology barriers were raised, corroborating existing work,13 but actionable solutions (eg, adding care team–only time before visits or verbalizing when to move stethoscopes) were also identified.

Embedding patient and care team experience surveys and sharing results is critical in advancing telemedicine. Findings from this evaluation strengthen the case for payer reimbursement of telemedicine in rural acute care. Continued work to improve, test, and publish findings on patient and care team experience with telemedicine is critical to providing quality services in often-underserved communities.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Ann Werner in identifying the patient survey sample, Brian Barklind in identifying source data for the analysis, and both Brian Barklind and Rachael Rivard for conducting the analyses and summarizing results. We would also like to thank Kelly Logue for her involvement in conceptualizing the telemedicine evaluation described here, as well as Larisa Polynskaya for her help preparing the manuscript for publication, and the care teams and patients who provided valuable input.

Healthcare delivery in rural America faces unique, growing challenges related to health and emergency care access.1 Telemedicine approaches have the potential to increase rural hospitals’ ability to deliver efficient emergency care and reduce clinician shortages.2 While initial evidence of telemedicine success exists, more quality research is needed to understand telemedicine patient and care team experiences,3 especially with real-time, clinician-initiated video conferencing in critical access hospital (CAH) emergency departments (ED). Some experience studies exist,4 but results are primarily quantitative5 and lack the nuanced qualitative depth needed to understand topics such as satisfaction and communication.6 Additionally, few explore combined patient and care team perspectives.5 The lack of breadth and depth makes it difficult to provide actionable recommendations for improvements and affects the feasibility of continuing this work and improving telemedicine care quality. To address these gaps, we evaluated a real-time, clinician-initiated video conferencing program with overnight clinicians servicing ED patients in three Midwestern care system CAHs. This evaluation assessed patient and care team (nurse and clinician) experience with telemedicine using quantitative and qualitative survey data analysis.

METHODS

Because this evaluation was designed to measure and improve program quality in a single healthcare system, it was deemed non-human subjects research by the organization’s institutional review board. This brief report follows telemedicine reporting guidelines.7

Setting and Telemedicine Program

This program, designed to reduce the need for on-call hospitalist clinicians to be onsite at CAHs overnight, was implemented in a large Midwestern nonprofit integrated healthcare system with three rural CAHs (combined capacity for 75 inpatient admissions, with full-time onsite ED clinicians and nurses, as well as on-call hospitalist clinicians) and a large metropolitan tertiary-care hospital. All adult patients presenting to CAH EDs between 6

Following a pilot period, the full-scale program was implemented in September 2017 and included 14 remote clinicians and 60 onsite nurses.

Survey Administration and Design

A postimplementation survey was designed to explore patient and care team experience with telemedicine. Patients who received a telemedicine visit between September 2017 and April 2018 were mailed a paper survey. Nonresponders were called by professional interviewers affiliated with the healthcare system. All participating clinicians (N = 14, all MDs) and nurses (N = 60, all RNs) were emailed an online care team survey with phone-in option. Care team nonresponders were sent up to two reminder emails.

Surveys captured the following five constructs: communication, workflow integration, telemedicine technology, quality of care, and general satisfaction. Existing questionnaires were used where possible; additional items were designed with clinical experts following survey design best practices.8 Patient-perceived communication was assessed via three Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems Outpatient and Ambulatory Surgery Survey items.9 Five additional program-developed patient survey items included satisfaction with clinician-nurse communication, satisfaction with technology, telemedicine quality of care overall and in comparison with traditional care, and whether or not patients would recommend telemedicine (Table). Four open-ended questions asked patients about improvement opportunities and general satisfaction.

Care team surveys included two items regarding ability to effectively communicate, two about satisfaction with workflow integration, one about technical problems, two about quality of care, and one about general satisfaction. Open-ended questions gathered further information and recommendations to improve communication, workflow integration, technology issues, and general satisfaction.

Analysis

Closed-ended items were dichotomized (satisfied yes/no); descriptive statistics (frequencies/percents) are presented to quantify patient and care team experience. Quantitative analyses were conducted in SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). Open-ended responses were coded separately for patient and care team experience, following qualitative content analysis best practices.10 A lead coder read all responses, created a coding framework of identified themes, and coded individual responses. A second coder independently coded responses using the same framework. Interrater reliability was calculated for each major theme using percent agreement and prevalence- and bias-adjusted

RESULTS

Of eligible patients mailed a survey (N = 408), 3% self-reported as ineligible, and 54% completed the survey. This is a maximum response rate (response rate 6) according to the American Association for Public Opinion Research.12 Patients were 67 years old on average (SD = 15), they were primarily white (97%), and 54% were female. All clinicians and 63% of nurses completed the survey.12 Clinicians and nurses were 29% and 95% female, respectively.

Quantitative results (Table) show generally positive experience across patient and care team respondents. Over 90% were satisfied with all measures of communication. Care teams had high satisfaction with admissions processes and reported telemedicine improved cross-coverage. Patient-reported technology experience was positive but was less positive from the care team perspective. Care teams reported lower absolute quality of care than did patients but were more likely to perceive telemedicine as high quality, compared with traditional care. Most patients, clinicians, and nurses would recommend telemedicine.

Qualitatively, four major themes were identified in open-ended responses with high interrater reliability (PABAK ranging from 0.92 to 0.98 in patient responses and 0.88 to 0.95 in care team responses) and aligned with the quantitative survey constructs: clinician-nurse communication, clinician-patient communication, workflow integration, and telemedicine technology. Patients reported satisfaction with communication with remote clinicians:

“[The clinician] was extremely attentive to me and what was going on. She was articulate and clear. I understood what was going to happen.” –Patient

Care teams suggested concrete improvement opportunities:

“I’d prefer to have some time with nursing staff both before and (sometimes) after the patient encounter.” –Clinician

“Since we cannot hear what [the clinicians] are hearing with the stethoscope, it’s nice when they tell us when to move it to the next spot.” –Nurse

Clinicians and nurses gave favorable responses regarding workflow integration, though time (both admissions wait time and session duration) was a reported opportunity:

“It would be helpful if we could speed up the time from admit request to screen time.” –Clinician

“When the [clinicians] get swamped, they’re hard to get a hold of, and admissions can take a long time. They may have too much on their plates dealing with several locations.” –Nurse

Technology issues—internet connection, stethoscope, sound, and screen or camera—were mentioned by patients and care teams, though technology was reviewed favorably overall by most patients:

“I was fascinated by the technology. Visiting someone over a television was impressive. ... The picture, the sound clarity, and the connection itself was flawless.” –Patient

Some patients commented that telemedicine was the best option given the situation, but still preferred an in-person doctor:

“If a doctor wasn’t available, telemedicine is better than nothing.” –Patient

Nurses who would not recommend telemedicine noted the need for personal connection:

“[I] still prefer [an] in-person MD for more personal contact. The older patients often state they wish the doctor would come and see them.” –Nurse

Patients who would not recommend telemedicine also desired personal connection:

“I would sooner talk to a person than a machine.” –Patient

A few clinicians noted the connection with patients would be improved if they knew about others in the room:

“It’d be nice if everyone in the room was introduced. Sometimes people are sitting out of view of the camera and I don’t realize they’re there until later.” –Clinician

CONCLUSION

These results make important contributions to understanding and improving the telemedicine experience in rural emergency hospital medicine. While the predominantly white patient respondent population limits generalizability, these demographics are representative of the overall population of the participating hospitals. A strength of this evaluation is its contemporaneous consideration of patient and care team experience with both quantitative and rich, qualitative analysis. Patients and care teams alike thought overnight telemedicine was better than the status quo. While our quality of care findings align with some previous literature,13 care teams in the current analysis overwhelmingly would recommend telemedicine, whereas some clinicians in prior work would not recommend telemedicine.14

In terms of communication, in line with existing literature, some patients still preferred in-person visits,15 a view also shared by some care team members. Workflow and technology barriers were raised, corroborating existing work,13 but actionable solutions (eg, adding care team–only time before visits or verbalizing when to move stethoscopes) were also identified.

Embedding patient and care team experience surveys and sharing results is critical in advancing telemedicine. Findings from this evaluation strengthen the case for payer reimbursement of telemedicine in rural acute care. Continued work to improve, test, and publish findings on patient and care team experience with telemedicine is critical to providing quality services in often-underserved communities.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Ann Werner in identifying the patient survey sample, Brian Barklind in identifying source data for the analysis, and both Brian Barklind and Rachael Rivard for conducting the analyses and summarizing results. We would also like to thank Kelly Logue for her involvement in conceptualizing the telemedicine evaluation described here, as well as Larisa Polynskaya for her help preparing the manuscript for publication, and the care teams and patients who provided valuable input.

1. Nelson R. Will rural community hospitals survive? Am J Nurs. 2017;117(9):18-19. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000524538.11040.7f.

2. Ward MM, Merchant KAS, Carter KD, et al. Use of telemedicine for ED physician coverage in critical access hospitals increased after CMS policy clarification. Health Aff. 2018;37(12):2037-2044. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05103.

3. AlDossary S, Martin-Khan MG, Bradford NK, Smith AC. A systematic review of the methodologies used to evaluate telemedicine service initiatives in hospital facilities. Int J Med Inf. 2017;97:171-194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2016.10.012.

4. Kuperman EF, Linson EL, Klefstad K, Perry E, Glenn K. The virtual hospitalist: a single-site implementation bringing hospitalist coverage to critical access hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(11):759-763. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3061.

5. Garcia R, Adelakun OA. A review of patient and provider satisfaction with telemedicine. Paper presented at: Twenty-third Americas Conference on Information Systems; 2017; Boston, Massachusetts.

6. Mair F, Whitten P. Systematic review of studies of patient satisfaction with telemedicine. BMJ. 2000;320(7248):1517-1520. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7248.1517.

7. Khanal S, Burgon J, Leonard S, Griffiths M, Eddowes LA. Recommendations for the improved effectiveness and reporting of telemedicine programs in developing countries: results of a systematic literature review. Telemed E Health. 2015;21(11):903-915. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2014.0194.

8. Fowler Jr FJ. Improving survey questions: Design and evaluation. Vol 38. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, Inc.; 1995.

9. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. CAHPS Outpatient and Ambulatory Surgery Survey. https://www.ahrq.gov/cahps/surveys-guidance/oas/index.html. Accessed August 1, 2017.

10. Ulin PR, Robinson ET, Tolley EE. Qualitative methods in public health: A field guide for applied research. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 2005.

11. Corden A, Sainsbury R. Using verbatim quotations in reporting qualitative social research: researches’ views. York, United Kingdom: University of York; 2006.

12. American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. 2016. https://www.aapor.org/AAPOR_Main/media/publications/Standard-Definitions20169theditionfinal.pdf. Accessed August 1, 2019.

13. Mueller KJ, Potter AJ, MacKinney AC, Ward MM. Lessons from tele-emergency: improving care quality and health outcomes by expanding support for rural care systems. Health Aff. 2014;33(2):228-234. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1016.

14. Fairchild R, Kuo SFF, Laws S, O’Brien A, Rahmouni H. Perceptions of rural emergency department providers regarding telehealth-based care: perceived competency, satisfaction with care and Tele-ED patient disposition. Open J Nurs. 2017;7(07):721. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojn.2017.77054.

15. Weatherburn G, Dowie R, Mistry H, Young T. An assessment of parental satisfaction with mode of delivery of specialist advice for paediatric cardiology: face-to-face versus videoconference. J Telemed Telecare. 2006;12(suppl 1):57-59. https://doi.org/10.1258/135763306777978560.

1. Nelson R. Will rural community hospitals survive? Am J Nurs. 2017;117(9):18-19. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000524538.11040.7f.

2. Ward MM, Merchant KAS, Carter KD, et al. Use of telemedicine for ED physician coverage in critical access hospitals increased after CMS policy clarification. Health Aff. 2018;37(12):2037-2044. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05103.

3. AlDossary S, Martin-Khan MG, Bradford NK, Smith AC. A systematic review of the methodologies used to evaluate telemedicine service initiatives in hospital facilities. Int J Med Inf. 2017;97:171-194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2016.10.012.

4. Kuperman EF, Linson EL, Klefstad K, Perry E, Glenn K. The virtual hospitalist: a single-site implementation bringing hospitalist coverage to critical access hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(11):759-763. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3061.

5. Garcia R, Adelakun OA. A review of patient and provider satisfaction with telemedicine. Paper presented at: Twenty-third Americas Conference on Information Systems; 2017; Boston, Massachusetts.

6. Mair F, Whitten P. Systematic review of studies of patient satisfaction with telemedicine. BMJ. 2000;320(7248):1517-1520. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7248.1517.

7. Khanal S, Burgon J, Leonard S, Griffiths M, Eddowes LA. Recommendations for the improved effectiveness and reporting of telemedicine programs in developing countries: results of a systematic literature review. Telemed E Health. 2015;21(11):903-915. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2014.0194.

8. Fowler Jr FJ. Improving survey questions: Design and evaluation. Vol 38. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, Inc.; 1995.

9. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. CAHPS Outpatient and Ambulatory Surgery Survey. https://www.ahrq.gov/cahps/surveys-guidance/oas/index.html. Accessed August 1, 2017.

10. Ulin PR, Robinson ET, Tolley EE. Qualitative methods in public health: A field guide for applied research. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 2005.

11. Corden A, Sainsbury R. Using verbatim quotations in reporting qualitative social research: researches’ views. York, United Kingdom: University of York; 2006.

12. American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. 2016. https://www.aapor.org/AAPOR_Main/media/publications/Standard-Definitions20169theditionfinal.pdf. Accessed August 1, 2019.

13. Mueller KJ, Potter AJ, MacKinney AC, Ward MM. Lessons from tele-emergency: improving care quality and health outcomes by expanding support for rural care systems. Health Aff. 2014;33(2):228-234. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1016.

14. Fairchild R, Kuo SFF, Laws S, O’Brien A, Rahmouni H. Perceptions of rural emergency department providers regarding telehealth-based care: perceived competency, satisfaction with care and Tele-ED patient disposition. Open J Nurs. 2017;7(07):721. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojn.2017.77054.

15. Weatherburn G, Dowie R, Mistry H, Young T. An assessment of parental satisfaction with mode of delivery of specialist advice for paediatric cardiology: face-to-face versus videoconference. J Telemed Telecare. 2006;12(suppl 1):57-59. https://doi.org/10.1258/135763306777978560.

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Keep Calm and Log On: Telemedicine for COVID-19 Pandemic Response

The field of telemedicine, in which clinicians use remote evaluation and monitoring to diagnose and treat patients, has grown substantially over the past decade. Its roles in acute care medicine settings are diverse, including virtual intensive care unit (ICU) care, after-hours medical admissions, cross coverage, and, most aptly, disaster management.1

At HealthPartners, a large integrated healthcare delivery and financing system based in the Twin Cities region of Minnesota, we have used provider-initiated telemedicine in hospital medicine for more than 2 years, providing evening and nighttime hospitalist coverage to our rural hospitals. We additionally provide a 24/7 nurse practitioner-staffed virtual clinic called Virtuwell.2 Because we are now immersed in a global pandemic, we have taken steps to bolster our telemedicine infrastructure to meet increasing needs.

SARS-CoV-2, the causative agent of COVID-19, is a novel coronavirus with the capability to cause severe illness in roughly 14% of those infected.3 According to some estimates, the virus may infect up to 60% of the US population in the next year.4 As the pandemic looms over the country and the healthcare community, telemedicine can offer tools to help respond to this crisis. Healthcare systems leveraging telemedicine for patient care will gain several advantages, including workforce sustainability, reduction of provider burnout, limitation of provider exposure, and reduction of personal protective equipment (PPE) waste (Table). Telemedicine can also facilitate staffing of both large and small facilities that find themselves overwhelmed with pandemic-related patient overload (PRPO). Although telemedicine holds promise for pandemic response, this technology has limitations. It requires robust IT infrastructure, training of both nurses and physicians, and modifications to integrate within hospital workflows. In this article, we summarize key clinical needs that telemedicine can meet, implementation challenges, and important business considerations.

BACKGROUND

Our organization currently uses telemedicine to provide after-hours hospital medicine coverage from 6

APPLICATIONS

Patient Triage

Limiting exposure in the community and in the acute care setting is key to “flattening the curve” in pandemics.5 Triaging patients by telephone and online surveys is an important method to prevent high-risk patients from exposing others to infection. For example, since March 9, 2020, over 20,000 patients have called in weekly for COVID-19 screening. Although our organization introduced drive-up testing to reduce exposure, patients are still presenting to our clinics and emergency rooms in need of screening and testing. In several of our clinics, patients have been roomed alone to facilitate screening in the room by use of Google Duo, a free video chat product. Rooms with telemedicine capabilities allow patients with potentially communicable infections to be evaluated and observed while avoiding the risk of viral transmission. Additional considerations could include self-administered nasal swabs; although this has comparable efficacy to staff-administered swabs,6 it has not yet been implemented in our clinics.

Direct Care

Virtual care, specifically synchronous video and audio provider-initiated services, is a well-established modality to provide direct care to patients in acute care and ambulatory settings.7 Telemedicine can be deployed to care for hospitalized patients in most locations as long as they meet the operational requirements described below. With a bedside nurse or other facilitator, patients can be interviewed and examined using a high definition camera and digital peripherals, including stethoscopes, otoscopes, ophthalmoscopes, and dermatoscopes. COVID-19 patients or patients under investigation may be seen in this manner. In-person visits should remain part of patients’ care as an important part of the provider-patient relationship8; however, telemedicine could still be deployed to provide direct care and monitoring to these patients while minimizing exposure to healthcare personnel. Additionally, telemedicine can be used for specialist consultations that are likely in high demand with COVID-19, including infectious disease, cardiology, and pulmonology.

Exposure Reduction and Resource Allocation

Currently in the United States there are concerns for shortages of PPE including surgical masks and N95 respirators. Telemedicine can reduce provider exposure, increase provider efficiency, and curtail PPE utilization by minimizing the number and frequency of in-room visits while still allowing virtual visits for direct patient care. For instance, our nursing staff is currently using telemedicine to conduct hourly rounding and limit unnecessary in-room visits.

We recommend keeping telemedicine equipment within individual isolation rooms intended for COVID-19 patients in order to eliminate the need for repeated cleaning. For other patients, a mobile cart could be used. Most commercial video software can autoanswer calls to allow for staff-free history taking. For a thorough physical exam, a bedside facilitator is need for use of digital stethoscopes and similar peripherals.

Provider Shortages and Reducing Burnout

Because SARS-CoV-2 is a highly contagious pathogen that can spread prior to symptom presentation, current CDC guidelines recommend self-monitoring at home for health care workers who have a healthcare-related exposure to a COVID-19 patient.9 This can leave significant gaps in coverage for healthcare systems. For example, in Vacaville, California, one positive case resulted in over 200 health care workers unable to work on site.10

Large volumes of acutely ill patients, coupled with the risk of ill or quarantined providers, means provider shortages due to PRPO are likely to occur and threaten hospitals’ ability to care for patients with or without COVID-19. Furthermore, given increased patient loads, frontline staff are at exceptionally high risk of burnout in pandemic situations. Hospital medicine teams will need contingency plans to meet the needs. Using telemedicine to protect the workforce and maintain staffing levels will reduce that risk.

Telehospitalists can see and examine patients, write orders, and maintain patient service lines much like in-person providers. Recently, we have used it when providers are ill or self-monitoring. In multisite systems, telehospitalists who are privileged in multiple hospitals can be efficiently deployed to meet patient care needs and relieve overburdened providers across hundreds of miles or more.

Enabling patient rooms for telemedicine allows telehospitalists and other providers to see hospitalized patients. Furthermore, quarantined hospitalists can continue to work and support in-person clinical services during PRPO. Providers in high-risk groups (eg, older, immunosuppressed, pregnant) can also continue caring for patients with telemedicine while maintaining safety. As schools close, telemedicine can help providers navigate the challenge between patient care and childcare responsibilities.

OPERATIONAL REQUIREMENTS

The basic element of telemedicine involves a computer or monitor with an internet-connected camera and a HIPAA-compliant video application, but implementation can vary.

Recent changes have allowed the use of popular video chat software such as FaceTime, Skype, or Google Duo for patient interactions; with a tablet attached to a stand, organizations can easily create a mobile telemedicine workstation. Larger monitors or mounted screens can be used in patient areas where portability is not required. A strong network infrastructure and robust IT support are also necessary; as of 2016, 24 million Americans did not have broadband access, and even areas that do can struggle with wireless connectivity in hospitals with thick concrete walls and lack of wi-fi extenders.11

With the addition of a digital stethoscope, hospitalists can perform a thorough history and physical with the aid of bedside staff. This requires dedicated training for all members of the care team in order to optimize the virtual hospitalist’s “telepresence” and create a seamless patient experience. Provider education is imperative: Creating a virtual telepresence is essential in building a strong provider-patient relationship. We have used simulation training to prepare new telehospitalists.

An overlooked, but important, operational requirement is patient education and awareness. In the absence of introduction and onboarding, telemedicine can be viewed by patients as impersonal; however, with proper implementation, high patient satisfaction has been demonstrated in other virtual care experiences.12

FINANCIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Though several health systems offer “tele-ICU” services, the number of hospital medicine programs is more limited. The cost of building a program can be significant, with outlays for equipment, IT support, provider salaries, and training. While all 50 states and the District of Columbia cover some form of fee-for-service live video with Medicaid, only 40, along with DC, have parity laws with commercial payors. Medicare has historically had more restrictions, limiting covered services to specific types of originating sites in certain geographic areas. Furthermore, growth of telehospitalist programs has been hampered by the lack of reimbursement for “primary care services.”13

With passage of the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act of 2020, geographic and site restrictions have been waived for Medicare reimbursement.14 Providers must still demonstrate a prior relationship with patients, which requires at least one encounter with the patient in the past 3 years by the same provider or one with a similar tax identification number (TIN). All hospitalists within our group are identified with a common TIN, which helps to meet this requirement for patient with recent admissions. However, clear guidance on reimbursement for primary care services by acute care providers is still lacking. As the utility of telemedicine is demonstrated in the hospital setting, we hope further changes may be enacted.

Organizations must properly credential and privilege telehospitalists. Telemedicine services may fall under either core or “delegated” privileges depending on the individual hospital. Additionally, while malpractice insurance does typically cover telemedicine services, each organization should verify this with their particular carrier.

SUMMARY

The COVID-19 pandemic has created a systemic challenge for healthcare systems across the nation. As hospitalists continue to be on the front lines, organizations can leverage telemedicine to support their patients, protect their clinicians, and conserve scarce resources. Building out a virtual care program is intricate and requires significant operational support. Laying the groundwork now can prepare institutions to provide necessary care for patients, not just in the current pandemic, but in numerous emergency health care situations in the future.

1. Lurie N, Carr BG. The role of telehealth in the medical response to disasters. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(6):745-74. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.1314.

2. Virtuwell. HealthPartners. 2020. https://www.virtuwell.com.

3. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72,314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.2648.

4. Powell A. Coronavirus screening may miss two-thirds of infected travelers entering U.S. The Harvard Gazette. 2020. https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2020/03/hundreds-of-u-s-coronavirus-cases-may-have-slipped-through-screenings/. Accessed March 13, 2020.

5. Hatchett RJ, Mecher CE, Lipsitch M. Public health interventions and epidemic intensity during the 1918 influenza pandemic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007:104(18);7582-7587. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0610941104.

6. Akmatov MK, Gatzemeier A, Schughart, K, Pessler F. Equivalence of self- and staff-collected nasal swabs for the detection of viral respiratory pathogens. PLoS One. 2012:7(11);e48508. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0048508.

7. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Telehealth Services. 2019. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/Downloads/Telehealth Srvcsfctsht.pdf. Accessed March 14, 2020.

8. Daniel H, Sulmasy LS. Policy recommendations to guide the use of telemedicine in primary care settings: an American College of Physicians position paper. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(10):787-789. https://doi.org/10.7326/M15-0498.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthcare Personnel with Potential Exposure to COVID-19. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-risk-assesment-hcp.html. Accessed March 13, 2020.

10. Gold J. Surging Health Care Worker Quarantines Raise Concerns as Coronavirus Spreads. Kaiser Health News. 2020. https://khn.org/news/surging-health-care-worker-quarantines-raise-concerns-as-coronavirus-spreads/. Accessed March 12, 2020.

11. Federal Communications Commission. 2018 Broadband Deployment Report. 2018. https://www.fcc.gov/reports-research/reports/broadband-progress-reports/2018-broadband-deployment-report. Accessed March 13, 2020.

12. Martinez KA, Rood M, Jhangiani N, et al. Patterns of use and correlates of patient satisfaction with a large nationwide direct to consumer telemedicine service. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(10):1768-1773. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4621-5.

13. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. List of Telehealth Services. 2019. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-General-Information/Telehealth/Telehealth-Codes. Accessed March 13, 2020.

14. Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2020, H.R. 6074, 116th Cong. 2020. https://congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/6074/. Accessed March 13, 2020.

The field of telemedicine, in which clinicians use remote evaluation and monitoring to diagnose and treat patients, has grown substantially over the past decade. Its roles in acute care medicine settings are diverse, including virtual intensive care unit (ICU) care, after-hours medical admissions, cross coverage, and, most aptly, disaster management.1

At HealthPartners, a large integrated healthcare delivery and financing system based in the Twin Cities region of Minnesota, we have used provider-initiated telemedicine in hospital medicine for more than 2 years, providing evening and nighttime hospitalist coverage to our rural hospitals. We additionally provide a 24/7 nurse practitioner-staffed virtual clinic called Virtuwell.2 Because we are now immersed in a global pandemic, we have taken steps to bolster our telemedicine infrastructure to meet increasing needs.

SARS-CoV-2, the causative agent of COVID-19, is a novel coronavirus with the capability to cause severe illness in roughly 14% of those infected.3 According to some estimates, the virus may infect up to 60% of the US population in the next year.4 As the pandemic looms over the country and the healthcare community, telemedicine can offer tools to help respond to this crisis. Healthcare systems leveraging telemedicine for patient care will gain several advantages, including workforce sustainability, reduction of provider burnout, limitation of provider exposure, and reduction of personal protective equipment (PPE) waste (Table). Telemedicine can also facilitate staffing of both large and small facilities that find themselves overwhelmed with pandemic-related patient overload (PRPO). Although telemedicine holds promise for pandemic response, this technology has limitations. It requires robust IT infrastructure, training of both nurses and physicians, and modifications to integrate within hospital workflows. In this article, we summarize key clinical needs that telemedicine can meet, implementation challenges, and important business considerations.

BACKGROUND

Our organization currently uses telemedicine to provide after-hours hospital medicine coverage from 6

APPLICATIONS

Patient Triage

Limiting exposure in the community and in the acute care setting is key to “flattening the curve” in pandemics.5 Triaging patients by telephone and online surveys is an important method to prevent high-risk patients from exposing others to infection. For example, since March 9, 2020, over 20,000 patients have called in weekly for COVID-19 screening. Although our organization introduced drive-up testing to reduce exposure, patients are still presenting to our clinics and emergency rooms in need of screening and testing. In several of our clinics, patients have been roomed alone to facilitate screening in the room by use of Google Duo, a free video chat product. Rooms with telemedicine capabilities allow patients with potentially communicable infections to be evaluated and observed while avoiding the risk of viral transmission. Additional considerations could include self-administered nasal swabs; although this has comparable efficacy to staff-administered swabs,6 it has not yet been implemented in our clinics.

Direct Care

Virtual care, specifically synchronous video and audio provider-initiated services, is a well-established modality to provide direct care to patients in acute care and ambulatory settings.7 Telemedicine can be deployed to care for hospitalized patients in most locations as long as they meet the operational requirements described below. With a bedside nurse or other facilitator, patients can be interviewed and examined using a high definition camera and digital peripherals, including stethoscopes, otoscopes, ophthalmoscopes, and dermatoscopes. COVID-19 patients or patients under investigation may be seen in this manner. In-person visits should remain part of patients’ care as an important part of the provider-patient relationship8; however, telemedicine could still be deployed to provide direct care and monitoring to these patients while minimizing exposure to healthcare personnel. Additionally, telemedicine can be used for specialist consultations that are likely in high demand with COVID-19, including infectious disease, cardiology, and pulmonology.

Exposure Reduction and Resource Allocation

Currently in the United States there are concerns for shortages of PPE including surgical masks and N95 respirators. Telemedicine can reduce provider exposure, increase provider efficiency, and curtail PPE utilization by minimizing the number and frequency of in-room visits while still allowing virtual visits for direct patient care. For instance, our nursing staff is currently using telemedicine to conduct hourly rounding and limit unnecessary in-room visits.

We recommend keeping telemedicine equipment within individual isolation rooms intended for COVID-19 patients in order to eliminate the need for repeated cleaning. For other patients, a mobile cart could be used. Most commercial video software can autoanswer calls to allow for staff-free history taking. For a thorough physical exam, a bedside facilitator is need for use of digital stethoscopes and similar peripherals.

Provider Shortages and Reducing Burnout

Because SARS-CoV-2 is a highly contagious pathogen that can spread prior to symptom presentation, current CDC guidelines recommend self-monitoring at home for health care workers who have a healthcare-related exposure to a COVID-19 patient.9 This can leave significant gaps in coverage for healthcare systems. For example, in Vacaville, California, one positive case resulted in over 200 health care workers unable to work on site.10

Large volumes of acutely ill patients, coupled with the risk of ill or quarantined providers, means provider shortages due to PRPO are likely to occur and threaten hospitals’ ability to care for patients with or without COVID-19. Furthermore, given increased patient loads, frontline staff are at exceptionally high risk of burnout in pandemic situations. Hospital medicine teams will need contingency plans to meet the needs. Using telemedicine to protect the workforce and maintain staffing levels will reduce that risk.

Telehospitalists can see and examine patients, write orders, and maintain patient service lines much like in-person providers. Recently, we have used it when providers are ill or self-monitoring. In multisite systems, telehospitalists who are privileged in multiple hospitals can be efficiently deployed to meet patient care needs and relieve overburdened providers across hundreds of miles or more.

Enabling patient rooms for telemedicine allows telehospitalists and other providers to see hospitalized patients. Furthermore, quarantined hospitalists can continue to work and support in-person clinical services during PRPO. Providers in high-risk groups (eg, older, immunosuppressed, pregnant) can also continue caring for patients with telemedicine while maintaining safety. As schools close, telemedicine can help providers navigate the challenge between patient care and childcare responsibilities.

OPERATIONAL REQUIREMENTS

The basic element of telemedicine involves a computer or monitor with an internet-connected camera and a HIPAA-compliant video application, but implementation can vary.

Recent changes have allowed the use of popular video chat software such as FaceTime, Skype, or Google Duo for patient interactions; with a tablet attached to a stand, organizations can easily create a mobile telemedicine workstation. Larger monitors or mounted screens can be used in patient areas where portability is not required. A strong network infrastructure and robust IT support are also necessary; as of 2016, 24 million Americans did not have broadband access, and even areas that do can struggle with wireless connectivity in hospitals with thick concrete walls and lack of wi-fi extenders.11

With the addition of a digital stethoscope, hospitalists can perform a thorough history and physical with the aid of bedside staff. This requires dedicated training for all members of the care team in order to optimize the virtual hospitalist’s “telepresence” and create a seamless patient experience. Provider education is imperative: Creating a virtual telepresence is essential in building a strong provider-patient relationship. We have used simulation training to prepare new telehospitalists.

An overlooked, but important, operational requirement is patient education and awareness. In the absence of introduction and onboarding, telemedicine can be viewed by patients as impersonal; however, with proper implementation, high patient satisfaction has been demonstrated in other virtual care experiences.12

FINANCIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Though several health systems offer “tele-ICU” services, the number of hospital medicine programs is more limited. The cost of building a program can be significant, with outlays for equipment, IT support, provider salaries, and training. While all 50 states and the District of Columbia cover some form of fee-for-service live video with Medicaid, only 40, along with DC, have parity laws with commercial payors. Medicare has historically had more restrictions, limiting covered services to specific types of originating sites in certain geographic areas. Furthermore, growth of telehospitalist programs has been hampered by the lack of reimbursement for “primary care services.”13

With passage of the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act of 2020, geographic and site restrictions have been waived for Medicare reimbursement.14 Providers must still demonstrate a prior relationship with patients, which requires at least one encounter with the patient in the past 3 years by the same provider or one with a similar tax identification number (TIN). All hospitalists within our group are identified with a common TIN, which helps to meet this requirement for patient with recent admissions. However, clear guidance on reimbursement for primary care services by acute care providers is still lacking. As the utility of telemedicine is demonstrated in the hospital setting, we hope further changes may be enacted.

Organizations must properly credential and privilege telehospitalists. Telemedicine services may fall under either core or “delegated” privileges depending on the individual hospital. Additionally, while malpractice insurance does typically cover telemedicine services, each organization should verify this with their particular carrier.

SUMMARY

The COVID-19 pandemic has created a systemic challenge for healthcare systems across the nation. As hospitalists continue to be on the front lines, organizations can leverage telemedicine to support their patients, protect their clinicians, and conserve scarce resources. Building out a virtual care program is intricate and requires significant operational support. Laying the groundwork now can prepare institutions to provide necessary care for patients, not just in the current pandemic, but in numerous emergency health care situations in the future.

The field of telemedicine, in which clinicians use remote evaluation and monitoring to diagnose and treat patients, has grown substantially over the past decade. Its roles in acute care medicine settings are diverse, including virtual intensive care unit (ICU) care, after-hours medical admissions, cross coverage, and, most aptly, disaster management.1

At HealthPartners, a large integrated healthcare delivery and financing system based in the Twin Cities region of Minnesota, we have used provider-initiated telemedicine in hospital medicine for more than 2 years, providing evening and nighttime hospitalist coverage to our rural hospitals. We additionally provide a 24/7 nurse practitioner-staffed virtual clinic called Virtuwell.2 Because we are now immersed in a global pandemic, we have taken steps to bolster our telemedicine infrastructure to meet increasing needs.

SARS-CoV-2, the causative agent of COVID-19, is a novel coronavirus with the capability to cause severe illness in roughly 14% of those infected.3 According to some estimates, the virus may infect up to 60% of the US population in the next year.4 As the pandemic looms over the country and the healthcare community, telemedicine can offer tools to help respond to this crisis. Healthcare systems leveraging telemedicine for patient care will gain several advantages, including workforce sustainability, reduction of provider burnout, limitation of provider exposure, and reduction of personal protective equipment (PPE) waste (Table). Telemedicine can also facilitate staffing of both large and small facilities that find themselves overwhelmed with pandemic-related patient overload (PRPO). Although telemedicine holds promise for pandemic response, this technology has limitations. It requires robust IT infrastructure, training of both nurses and physicians, and modifications to integrate within hospital workflows. In this article, we summarize key clinical needs that telemedicine can meet, implementation challenges, and important business considerations.

BACKGROUND

Our organization currently uses telemedicine to provide after-hours hospital medicine coverage from 6

APPLICATIONS

Patient Triage

Limiting exposure in the community and in the acute care setting is key to “flattening the curve” in pandemics.5 Triaging patients by telephone and online surveys is an important method to prevent high-risk patients from exposing others to infection. For example, since March 9, 2020, over 20,000 patients have called in weekly for COVID-19 screening. Although our organization introduced drive-up testing to reduce exposure, patients are still presenting to our clinics and emergency rooms in need of screening and testing. In several of our clinics, patients have been roomed alone to facilitate screening in the room by use of Google Duo, a free video chat product. Rooms with telemedicine capabilities allow patients with potentially communicable infections to be evaluated and observed while avoiding the risk of viral transmission. Additional considerations could include self-administered nasal swabs; although this has comparable efficacy to staff-administered swabs,6 it has not yet been implemented in our clinics.

Direct Care

Virtual care, specifically synchronous video and audio provider-initiated services, is a well-established modality to provide direct care to patients in acute care and ambulatory settings.7 Telemedicine can be deployed to care for hospitalized patients in most locations as long as they meet the operational requirements described below. With a bedside nurse or other facilitator, patients can be interviewed and examined using a high definition camera and digital peripherals, including stethoscopes, otoscopes, ophthalmoscopes, and dermatoscopes. COVID-19 patients or patients under investigation may be seen in this manner. In-person visits should remain part of patients’ care as an important part of the provider-patient relationship8; however, telemedicine could still be deployed to provide direct care and monitoring to these patients while minimizing exposure to healthcare personnel. Additionally, telemedicine can be used for specialist consultations that are likely in high demand with COVID-19, including infectious disease, cardiology, and pulmonology.

Exposure Reduction and Resource Allocation

Currently in the United States there are concerns for shortages of PPE including surgical masks and N95 respirators. Telemedicine can reduce provider exposure, increase provider efficiency, and curtail PPE utilization by minimizing the number and frequency of in-room visits while still allowing virtual visits for direct patient care. For instance, our nursing staff is currently using telemedicine to conduct hourly rounding and limit unnecessary in-room visits.

We recommend keeping telemedicine equipment within individual isolation rooms intended for COVID-19 patients in order to eliminate the need for repeated cleaning. For other patients, a mobile cart could be used. Most commercial video software can autoanswer calls to allow for staff-free history taking. For a thorough physical exam, a bedside facilitator is need for use of digital stethoscopes and similar peripherals.

Provider Shortages and Reducing Burnout

Because SARS-CoV-2 is a highly contagious pathogen that can spread prior to symptom presentation, current CDC guidelines recommend self-monitoring at home for health care workers who have a healthcare-related exposure to a COVID-19 patient.9 This can leave significant gaps in coverage for healthcare systems. For example, in Vacaville, California, one positive case resulted in over 200 health care workers unable to work on site.10

Large volumes of acutely ill patients, coupled with the risk of ill or quarantined providers, means provider shortages due to PRPO are likely to occur and threaten hospitals’ ability to care for patients with or without COVID-19. Furthermore, given increased patient loads, frontline staff are at exceptionally high risk of burnout in pandemic situations. Hospital medicine teams will need contingency plans to meet the needs. Using telemedicine to protect the workforce and maintain staffing levels will reduce that risk.

Telehospitalists can see and examine patients, write orders, and maintain patient service lines much like in-person providers. Recently, we have used it when providers are ill or self-monitoring. In multisite systems, telehospitalists who are privileged in multiple hospitals can be efficiently deployed to meet patient care needs and relieve overburdened providers across hundreds of miles or more.

Enabling patient rooms for telemedicine allows telehospitalists and other providers to see hospitalized patients. Furthermore, quarantined hospitalists can continue to work and support in-person clinical services during PRPO. Providers in high-risk groups (eg, older, immunosuppressed, pregnant) can also continue caring for patients with telemedicine while maintaining safety. As schools close, telemedicine can help providers navigate the challenge between patient care and childcare responsibilities.

OPERATIONAL REQUIREMENTS

The basic element of telemedicine involves a computer or monitor with an internet-connected camera and a HIPAA-compliant video application, but implementation can vary.

Recent changes have allowed the use of popular video chat software such as FaceTime, Skype, or Google Duo for patient interactions; with a tablet attached to a stand, organizations can easily create a mobile telemedicine workstation. Larger monitors or mounted screens can be used in patient areas where portability is not required. A strong network infrastructure and robust IT support are also necessary; as of 2016, 24 million Americans did not have broadband access, and even areas that do can struggle with wireless connectivity in hospitals with thick concrete walls and lack of wi-fi extenders.11

With the addition of a digital stethoscope, hospitalists can perform a thorough history and physical with the aid of bedside staff. This requires dedicated training for all members of the care team in order to optimize the virtual hospitalist’s “telepresence” and create a seamless patient experience. Provider education is imperative: Creating a virtual telepresence is essential in building a strong provider-patient relationship. We have used simulation training to prepare new telehospitalists.

An overlooked, but important, operational requirement is patient education and awareness. In the absence of introduction and onboarding, telemedicine can be viewed by patients as impersonal; however, with proper implementation, high patient satisfaction has been demonstrated in other virtual care experiences.12

FINANCIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Though several health systems offer “tele-ICU” services, the number of hospital medicine programs is more limited. The cost of building a program can be significant, with outlays for equipment, IT support, provider salaries, and training. While all 50 states and the District of Columbia cover some form of fee-for-service live video with Medicaid, only 40, along with DC, have parity laws with commercial payors. Medicare has historically had more restrictions, limiting covered services to specific types of originating sites in certain geographic areas. Furthermore, growth of telehospitalist programs has been hampered by the lack of reimbursement for “primary care services.”13

With passage of the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act of 2020, geographic and site restrictions have been waived for Medicare reimbursement.14 Providers must still demonstrate a prior relationship with patients, which requires at least one encounter with the patient in the past 3 years by the same provider or one with a similar tax identification number (TIN). All hospitalists within our group are identified with a common TIN, which helps to meet this requirement for patient with recent admissions. However, clear guidance on reimbursement for primary care services by acute care providers is still lacking. As the utility of telemedicine is demonstrated in the hospital setting, we hope further changes may be enacted.

Organizations must properly credential and privilege telehospitalists. Telemedicine services may fall under either core or “delegated” privileges depending on the individual hospital. Additionally, while malpractice insurance does typically cover telemedicine services, each organization should verify this with their particular carrier.

SUMMARY

The COVID-19 pandemic has created a systemic challenge for healthcare systems across the nation. As hospitalists continue to be on the front lines, organizations can leverage telemedicine to support their patients, protect their clinicians, and conserve scarce resources. Building out a virtual care program is intricate and requires significant operational support. Laying the groundwork now can prepare institutions to provide necessary care for patients, not just in the current pandemic, but in numerous emergency health care situations in the future.

1. Lurie N, Carr BG. The role of telehealth in the medical response to disasters. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(6):745-74. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.1314.

2. Virtuwell. HealthPartners. 2020. https://www.virtuwell.com.

3. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72,314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.2648.

4. Powell A. Coronavirus screening may miss two-thirds of infected travelers entering U.S. The Harvard Gazette. 2020. https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2020/03/hundreds-of-u-s-coronavirus-cases-may-have-slipped-through-screenings/. Accessed March 13, 2020.