User login

Primary Cutaneous Epstein-Barr Virus–Positive Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma: A Rare and Aggressive Cutaneous Lymphoma

Cutaneous B-cell lymphomas represent a group of lymphomas derived from B lymphocytes in various stages of differentiation. The skin can be the site of primary or secondary involvement of any of the B-cell lymphomas. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas present in the skin without evidence of extracutaneous disease at the time of diagnosis.1 The World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues recognizes 5 distinct primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma subtypes: primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma; primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma; primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), leg type; DLBCL, not otherwise specified; and intravascular DLBCL.1-3 The DLBCL, not otherwise specified, category includes less common provisional entities with insufficient evidence to be recognized as distinct diseases. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–positive DLBCL is a rare subtype in this group.4

This article reviews the different clinicopathologic subtypes of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. It also serves to help dermatologists recognize primary cutaneous EBV-positive DLBCL as a rare and aggressive form of this disease.

Case Report

An 84-year-old white man presented with a pruritic eruption on the arms, legs, back, neck, and face of 5 months’ duration. His medical history was notable for prostate cancer that was successfully treated with radiation therapy 6 years prior. The patient denied any constitutional symptoms such as fever, chills, night sweats, or weight loss, and review of systems was negative. The patient was taking prednisone, which alleviated the pruritus, but the lesions persisted.

Physical examination revealed multiple pink to erythematous papules and subcutaneous nodules involving the face, neck, back, arms, and legs (Figure 1). No scale, crust, or ulceration was present. Palpation of the cervical, supraclavicular, axillary, and inguinal lymph nodes was negative for lymphadenopathy.

Punch biopsies of representative lesions on the upper back and right arm revealed diffuse and nodular infiltrates of large atypical lymphoid cells with scattered centroblasts and immunoblasts (Figures 2 and 3). Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated CD79, MUM-1, and EBV-encoded RNA positivity among the neoplastic cells. The Ki-67 proliferative index was greater than 90%. The neoplastic cells were negative for CD5, CD10, CD20, CD21, CD30, CD56, CD123, CD138, PAX5, C-MYC, BCL-2, BCL-6, cyclin D1, TCL-1A, and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase

A peripheral blood smear did not show evidence of a B-cell lymphoproliferative process. A bone marrow biopsy was performed and did not show evidence of B-cell lymphoid neoplasia but did show reactive lymphoid aggregates composed of CD4+ and CD10+ T cells. Peripheral blood T-cell rearrangement and JAK2 were negative.

Based on clinical and histologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with primary cutaneous EBV-positive DLBCL. The patient was started on CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) chemotherapy for treatment of this aggressive cutaneous lymphoma, which initially resulted in clinical improvement of the lesions and complete involution of the subcutaneous nodules. After the sixth cycle of CHOP, he developed faintly erythematous indurated papules on the upper arms, chest, and back. Biopsy confirmed recurrence of the EBV-positive cutaneous lymphoma, and he started salvage chemotherapy with gemcitabine, oxaliplatin, and rituximab every 2 weeks; however, 4 months later (9 months after the initial presentation) he died from complications of the disease.

Comment

Etiology

Epstein-Barr virus–positive DLBCL, also called EBV-positive DLBCL of the elderly, was initially described in 2003 by Oyama et al5 and was included as a provisional entity in the 2008 World Health Organization classification system as a rare subtype of the DLBCL, not otherwise specified, category.2 It is defined as an EBV-positive monoclonal large B-cell proliferation that occurs in immunocompetent patients older than 50 years.6 Epstein-Barr virus is a human herpesvirus that demonstrates tropism for lymphocytes and survives in human hosts by establishing latency in B cells. Under normal immune conditions, the proliferation of EBV-infected B cells is prevented by cytotoxic T cells.7 It is important to recognize that patients with EBV-positive DLBCL do not have a known immunodeficiency state; therefore, it has been postulated that EBV-positive DLBCL might be caused by age-related senescence of the immune system.4,8

Epidemiology and Clinical Features

Epstein-Barr virus–positive DLBCL is more common in Asian countries than in Western countries, and there is a slight male predominance.6 A majority of patients present with extranodal disease at the time of diagnosis, and the skin is the most common extranodal site of involvement.6,9 Rare cases of primary cutaneous involvement also have been described.7,9,10 Cutaneous manifestations include erythematous papules and subcutaneous nodules. Other sites of extranodal involvement include the lungs, oral cavity, pharynx, gastrointestinal tract, and bone marrow.8,9 However, EBV-positive DLBCL is an aggressive lymphoma and prognosis is poor irrespective of the primary site of involvement.

Histopathology

Two morphologic subtypes can be seen on histology. The polymorphic pattern is characterized by a broad range of B-cell maturation with admixed reactive cells (eg, lymphocytes, histiocytes, plasma cells). The monomorphic or large-cell pattern is characterized by monotonous sheets of large transformed B cells.4,11 Many cases show both histologic patterns, and these morphologic variants do not impart any clinical or prognostic significance. Regardless of the histologic subtype, the neoplastic cells express pan B-cell antigens (eg, CD19, CD20, CD79a, PAX5), as well as MUM-1, BCL-2, and EBV-encoded RNA.4 Cases with plasmablastic features, as in our patient, may show weak or absent CD20 staining.12 Detection of EBV by in situ hybridization is required for the diagnosis.

Diagnosis

Workup for a suspected cutaneous lymphoma should include a complete history and physical examination; laboratory studies; and relevant imaging evaluation such as computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis with or without whole-body positron emission tomography. A bone marrow biopsy and aspirate also should be performed in all cutaneous lymphomas with intermediate to aggressive clinical behavior. Accurate staging evaluation is integral to confirm the absence of extracutaneous involvement and to provide prognostic and anatomic information for the appropriate selection of treatment.13

Prognosis and Management

Primary cutaneous lymphomas tend to have different clinical behaviors and prognoses compared to histologically similar systemic lymphomas; therefore, different therapeutic strategies are warranted.14 Epstein-Barr virus–positive DLBCL has an aggressive clinical course with a median survival of 2 years.8 Patients with EBV-positive DLBCL have a poorer overall survival and treatment response when compared to patients with EBV-negative DLBCLs.4 Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas with indolent behavior, such as primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma and primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma, can be treated with surgical excision, radiation therapy, or observation.15 No standard treatment exists for EBV-positive DLBCL, but R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone), which is the standard treatment of primary cutaneous DLBCL, leg type, may provide a survival benefit.13,15 Further studies are required to determine optimal treatment strategies.

Conclusion

Although rare, EBV-positive DLBCL is an important entity to consider when evaluating a patient with a suspected primary cutaneous lymphoma. Workup to rule out an underlying systemic lymphoma with relevant laboratory evaluation, imaging studies, and bone marrow biopsy is critical. Prognosis is poor and treatment is difficult, as standard treatment protocols have yet to be determined.

- Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

- Nakmura S, Jaffe ES, Swerdlow SH. EBV positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the elderly. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. 4th ed. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC); 2008:243-244.

- Kempf W, Sander CA. Classification of cutaneous lymphomas—an update. Histopathology. 2010;56:57-70.

- Castillo JJ, Beltran BE, Miranda RN, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the elderly: what we know so far. Oncologist. 2011;16:87-96.

- Oyama T, Ichimura K, Suzuki R, et al. Senile EBV+ B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders: a clinicopathologic study of 22 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:16-26.

- Ok CY, Papathomas TG, Medeiros LJ, et al. EBV-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the elderly. Blood. 2013;122:328-340.

- Tokuda Y, Fukushima M, Nakazawa K, et al. A case of primary Epstein-Barr virus-associated cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma unassociated with iatrogenic or endogenous immune dysregulation. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:666-671.

- Oyama T, Yamamoto K, Asano N, et al. Age-related EBV-associated B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders constitute a distinct clinicopathologic group: a study of 96 patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5124-5132.

- Eminger LA, Hall LD, Hesterman KS, et al. Epstein-Barr virus: dermatologic associations and implications. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:21-34.

- Martin B, Whittaker S, Morris S, et al. A case of primary cutaneous senile EBV-related diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:190-193.

- Gibson SE, Hsi ED. Epstein-Barr virus-positive B-cell lymphoma of the elderly at a United States tertiary medical center: an uncommon aggressive lymphoma with a nongerminal center B-cell phenotype. Hum Pathol. 2009;40:653-661.

- Castillo JJ, Bibas M, Miranda RN. The biology and treatment of plasmablastic lymphoma. Blood. 2015;125:2323-2330.

- Kim YH, Willemze R, Pimpinelli N, et al. TNM classification system for primary cutaneous lymphomas other than mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: a proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Blood. 2007;110:479-484.

- Suárez AL, Pulitzer M, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: part I. clinical features, diagnosis, and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:329.e1-329.e13; quiz 341-342.

- Suárez AL, Querfeld C, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: part II. therapy and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:343.e1-343.e11; quiz 355-356.

Cutaneous B-cell lymphomas represent a group of lymphomas derived from B lymphocytes in various stages of differentiation. The skin can be the site of primary or secondary involvement of any of the B-cell lymphomas. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas present in the skin without evidence of extracutaneous disease at the time of diagnosis.1 The World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues recognizes 5 distinct primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma subtypes: primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma; primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma; primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), leg type; DLBCL, not otherwise specified; and intravascular DLBCL.1-3 The DLBCL, not otherwise specified, category includes less common provisional entities with insufficient evidence to be recognized as distinct diseases. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–positive DLBCL is a rare subtype in this group.4

This article reviews the different clinicopathologic subtypes of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. It also serves to help dermatologists recognize primary cutaneous EBV-positive DLBCL as a rare and aggressive form of this disease.

Case Report

An 84-year-old white man presented with a pruritic eruption on the arms, legs, back, neck, and face of 5 months’ duration. His medical history was notable for prostate cancer that was successfully treated with radiation therapy 6 years prior. The patient denied any constitutional symptoms such as fever, chills, night sweats, or weight loss, and review of systems was negative. The patient was taking prednisone, which alleviated the pruritus, but the lesions persisted.

Physical examination revealed multiple pink to erythematous papules and subcutaneous nodules involving the face, neck, back, arms, and legs (Figure 1). No scale, crust, or ulceration was present. Palpation of the cervical, supraclavicular, axillary, and inguinal lymph nodes was negative for lymphadenopathy.

Punch biopsies of representative lesions on the upper back and right arm revealed diffuse and nodular infiltrates of large atypical lymphoid cells with scattered centroblasts and immunoblasts (Figures 2 and 3). Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated CD79, MUM-1, and EBV-encoded RNA positivity among the neoplastic cells. The Ki-67 proliferative index was greater than 90%. The neoplastic cells were negative for CD5, CD10, CD20, CD21, CD30, CD56, CD123, CD138, PAX5, C-MYC, BCL-2, BCL-6, cyclin D1, TCL-1A, and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase

A peripheral blood smear did not show evidence of a B-cell lymphoproliferative process. A bone marrow biopsy was performed and did not show evidence of B-cell lymphoid neoplasia but did show reactive lymphoid aggregates composed of CD4+ and CD10+ T cells. Peripheral blood T-cell rearrangement and JAK2 were negative.

Based on clinical and histologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with primary cutaneous EBV-positive DLBCL. The patient was started on CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) chemotherapy for treatment of this aggressive cutaneous lymphoma, which initially resulted in clinical improvement of the lesions and complete involution of the subcutaneous nodules. After the sixth cycle of CHOP, he developed faintly erythematous indurated papules on the upper arms, chest, and back. Biopsy confirmed recurrence of the EBV-positive cutaneous lymphoma, and he started salvage chemotherapy with gemcitabine, oxaliplatin, and rituximab every 2 weeks; however, 4 months later (9 months after the initial presentation) he died from complications of the disease.

Comment

Etiology

Epstein-Barr virus–positive DLBCL, also called EBV-positive DLBCL of the elderly, was initially described in 2003 by Oyama et al5 and was included as a provisional entity in the 2008 World Health Organization classification system as a rare subtype of the DLBCL, not otherwise specified, category.2 It is defined as an EBV-positive monoclonal large B-cell proliferation that occurs in immunocompetent patients older than 50 years.6 Epstein-Barr virus is a human herpesvirus that demonstrates tropism for lymphocytes and survives in human hosts by establishing latency in B cells. Under normal immune conditions, the proliferation of EBV-infected B cells is prevented by cytotoxic T cells.7 It is important to recognize that patients with EBV-positive DLBCL do not have a known immunodeficiency state; therefore, it has been postulated that EBV-positive DLBCL might be caused by age-related senescence of the immune system.4,8

Epidemiology and Clinical Features

Epstein-Barr virus–positive DLBCL is more common in Asian countries than in Western countries, and there is a slight male predominance.6 A majority of patients present with extranodal disease at the time of diagnosis, and the skin is the most common extranodal site of involvement.6,9 Rare cases of primary cutaneous involvement also have been described.7,9,10 Cutaneous manifestations include erythematous papules and subcutaneous nodules. Other sites of extranodal involvement include the lungs, oral cavity, pharynx, gastrointestinal tract, and bone marrow.8,9 However, EBV-positive DLBCL is an aggressive lymphoma and prognosis is poor irrespective of the primary site of involvement.

Histopathology

Two morphologic subtypes can be seen on histology. The polymorphic pattern is characterized by a broad range of B-cell maturation with admixed reactive cells (eg, lymphocytes, histiocytes, plasma cells). The monomorphic or large-cell pattern is characterized by monotonous sheets of large transformed B cells.4,11 Many cases show both histologic patterns, and these morphologic variants do not impart any clinical or prognostic significance. Regardless of the histologic subtype, the neoplastic cells express pan B-cell antigens (eg, CD19, CD20, CD79a, PAX5), as well as MUM-1, BCL-2, and EBV-encoded RNA.4 Cases with plasmablastic features, as in our patient, may show weak or absent CD20 staining.12 Detection of EBV by in situ hybridization is required for the diagnosis.

Diagnosis

Workup for a suspected cutaneous lymphoma should include a complete history and physical examination; laboratory studies; and relevant imaging evaluation such as computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis with or without whole-body positron emission tomography. A bone marrow biopsy and aspirate also should be performed in all cutaneous lymphomas with intermediate to aggressive clinical behavior. Accurate staging evaluation is integral to confirm the absence of extracutaneous involvement and to provide prognostic and anatomic information for the appropriate selection of treatment.13

Prognosis and Management

Primary cutaneous lymphomas tend to have different clinical behaviors and prognoses compared to histologically similar systemic lymphomas; therefore, different therapeutic strategies are warranted.14 Epstein-Barr virus–positive DLBCL has an aggressive clinical course with a median survival of 2 years.8 Patients with EBV-positive DLBCL have a poorer overall survival and treatment response when compared to patients with EBV-negative DLBCLs.4 Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas with indolent behavior, such as primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma and primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma, can be treated with surgical excision, radiation therapy, or observation.15 No standard treatment exists for EBV-positive DLBCL, but R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone), which is the standard treatment of primary cutaneous DLBCL, leg type, may provide a survival benefit.13,15 Further studies are required to determine optimal treatment strategies.

Conclusion

Although rare, EBV-positive DLBCL is an important entity to consider when evaluating a patient with a suspected primary cutaneous lymphoma. Workup to rule out an underlying systemic lymphoma with relevant laboratory evaluation, imaging studies, and bone marrow biopsy is critical. Prognosis is poor and treatment is difficult, as standard treatment protocols have yet to be determined.

Cutaneous B-cell lymphomas represent a group of lymphomas derived from B lymphocytes in various stages of differentiation. The skin can be the site of primary or secondary involvement of any of the B-cell lymphomas. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas present in the skin without evidence of extracutaneous disease at the time of diagnosis.1 The World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues recognizes 5 distinct primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma subtypes: primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma; primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma; primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), leg type; DLBCL, not otherwise specified; and intravascular DLBCL.1-3 The DLBCL, not otherwise specified, category includes less common provisional entities with insufficient evidence to be recognized as distinct diseases. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–positive DLBCL is a rare subtype in this group.4

This article reviews the different clinicopathologic subtypes of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. It also serves to help dermatologists recognize primary cutaneous EBV-positive DLBCL as a rare and aggressive form of this disease.

Case Report

An 84-year-old white man presented with a pruritic eruption on the arms, legs, back, neck, and face of 5 months’ duration. His medical history was notable for prostate cancer that was successfully treated with radiation therapy 6 years prior. The patient denied any constitutional symptoms such as fever, chills, night sweats, or weight loss, and review of systems was negative. The patient was taking prednisone, which alleviated the pruritus, but the lesions persisted.

Physical examination revealed multiple pink to erythematous papules and subcutaneous nodules involving the face, neck, back, arms, and legs (Figure 1). No scale, crust, or ulceration was present. Palpation of the cervical, supraclavicular, axillary, and inguinal lymph nodes was negative for lymphadenopathy.

Punch biopsies of representative lesions on the upper back and right arm revealed diffuse and nodular infiltrates of large atypical lymphoid cells with scattered centroblasts and immunoblasts (Figures 2 and 3). Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated CD79, MUM-1, and EBV-encoded RNA positivity among the neoplastic cells. The Ki-67 proliferative index was greater than 90%. The neoplastic cells were negative for CD5, CD10, CD20, CD21, CD30, CD56, CD123, CD138, PAX5, C-MYC, BCL-2, BCL-6, cyclin D1, TCL-1A, and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase

A peripheral blood smear did not show evidence of a B-cell lymphoproliferative process. A bone marrow biopsy was performed and did not show evidence of B-cell lymphoid neoplasia but did show reactive lymphoid aggregates composed of CD4+ and CD10+ T cells. Peripheral blood T-cell rearrangement and JAK2 were negative.

Based on clinical and histologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with primary cutaneous EBV-positive DLBCL. The patient was started on CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) chemotherapy for treatment of this aggressive cutaneous lymphoma, which initially resulted in clinical improvement of the lesions and complete involution of the subcutaneous nodules. After the sixth cycle of CHOP, he developed faintly erythematous indurated papules on the upper arms, chest, and back. Biopsy confirmed recurrence of the EBV-positive cutaneous lymphoma, and he started salvage chemotherapy with gemcitabine, oxaliplatin, and rituximab every 2 weeks; however, 4 months later (9 months after the initial presentation) he died from complications of the disease.

Comment

Etiology

Epstein-Barr virus–positive DLBCL, also called EBV-positive DLBCL of the elderly, was initially described in 2003 by Oyama et al5 and was included as a provisional entity in the 2008 World Health Organization classification system as a rare subtype of the DLBCL, not otherwise specified, category.2 It is defined as an EBV-positive monoclonal large B-cell proliferation that occurs in immunocompetent patients older than 50 years.6 Epstein-Barr virus is a human herpesvirus that demonstrates tropism for lymphocytes and survives in human hosts by establishing latency in B cells. Under normal immune conditions, the proliferation of EBV-infected B cells is prevented by cytotoxic T cells.7 It is important to recognize that patients with EBV-positive DLBCL do not have a known immunodeficiency state; therefore, it has been postulated that EBV-positive DLBCL might be caused by age-related senescence of the immune system.4,8

Epidemiology and Clinical Features

Epstein-Barr virus–positive DLBCL is more common in Asian countries than in Western countries, and there is a slight male predominance.6 A majority of patients present with extranodal disease at the time of diagnosis, and the skin is the most common extranodal site of involvement.6,9 Rare cases of primary cutaneous involvement also have been described.7,9,10 Cutaneous manifestations include erythematous papules and subcutaneous nodules. Other sites of extranodal involvement include the lungs, oral cavity, pharynx, gastrointestinal tract, and bone marrow.8,9 However, EBV-positive DLBCL is an aggressive lymphoma and prognosis is poor irrespective of the primary site of involvement.

Histopathology

Two morphologic subtypes can be seen on histology. The polymorphic pattern is characterized by a broad range of B-cell maturation with admixed reactive cells (eg, lymphocytes, histiocytes, plasma cells). The monomorphic or large-cell pattern is characterized by monotonous sheets of large transformed B cells.4,11 Many cases show both histologic patterns, and these morphologic variants do not impart any clinical or prognostic significance. Regardless of the histologic subtype, the neoplastic cells express pan B-cell antigens (eg, CD19, CD20, CD79a, PAX5), as well as MUM-1, BCL-2, and EBV-encoded RNA.4 Cases with plasmablastic features, as in our patient, may show weak or absent CD20 staining.12 Detection of EBV by in situ hybridization is required for the diagnosis.

Diagnosis

Workup for a suspected cutaneous lymphoma should include a complete history and physical examination; laboratory studies; and relevant imaging evaluation such as computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis with or without whole-body positron emission tomography. A bone marrow biopsy and aspirate also should be performed in all cutaneous lymphomas with intermediate to aggressive clinical behavior. Accurate staging evaluation is integral to confirm the absence of extracutaneous involvement and to provide prognostic and anatomic information for the appropriate selection of treatment.13

Prognosis and Management

Primary cutaneous lymphomas tend to have different clinical behaviors and prognoses compared to histologically similar systemic lymphomas; therefore, different therapeutic strategies are warranted.14 Epstein-Barr virus–positive DLBCL has an aggressive clinical course with a median survival of 2 years.8 Patients with EBV-positive DLBCL have a poorer overall survival and treatment response when compared to patients with EBV-negative DLBCLs.4 Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas with indolent behavior, such as primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma and primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma, can be treated with surgical excision, radiation therapy, or observation.15 No standard treatment exists for EBV-positive DLBCL, but R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone), which is the standard treatment of primary cutaneous DLBCL, leg type, may provide a survival benefit.13,15 Further studies are required to determine optimal treatment strategies.

Conclusion

Although rare, EBV-positive DLBCL is an important entity to consider when evaluating a patient with a suspected primary cutaneous lymphoma. Workup to rule out an underlying systemic lymphoma with relevant laboratory evaluation, imaging studies, and bone marrow biopsy is critical. Prognosis is poor and treatment is difficult, as standard treatment protocols have yet to be determined.

- Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

- Nakmura S, Jaffe ES, Swerdlow SH. EBV positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the elderly. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. 4th ed. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC); 2008:243-244.

- Kempf W, Sander CA. Classification of cutaneous lymphomas—an update. Histopathology. 2010;56:57-70.

- Castillo JJ, Beltran BE, Miranda RN, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the elderly: what we know so far. Oncologist. 2011;16:87-96.

- Oyama T, Ichimura K, Suzuki R, et al. Senile EBV+ B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders: a clinicopathologic study of 22 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:16-26.

- Ok CY, Papathomas TG, Medeiros LJ, et al. EBV-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the elderly. Blood. 2013;122:328-340.

- Tokuda Y, Fukushima M, Nakazawa K, et al. A case of primary Epstein-Barr virus-associated cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma unassociated with iatrogenic or endogenous immune dysregulation. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:666-671.

- Oyama T, Yamamoto K, Asano N, et al. Age-related EBV-associated B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders constitute a distinct clinicopathologic group: a study of 96 patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5124-5132.

- Eminger LA, Hall LD, Hesterman KS, et al. Epstein-Barr virus: dermatologic associations and implications. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:21-34.

- Martin B, Whittaker S, Morris S, et al. A case of primary cutaneous senile EBV-related diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:190-193.

- Gibson SE, Hsi ED. Epstein-Barr virus-positive B-cell lymphoma of the elderly at a United States tertiary medical center: an uncommon aggressive lymphoma with a nongerminal center B-cell phenotype. Hum Pathol. 2009;40:653-661.

- Castillo JJ, Bibas M, Miranda RN. The biology and treatment of plasmablastic lymphoma. Blood. 2015;125:2323-2330.

- Kim YH, Willemze R, Pimpinelli N, et al. TNM classification system for primary cutaneous lymphomas other than mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: a proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Blood. 2007;110:479-484.

- Suárez AL, Pulitzer M, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: part I. clinical features, diagnosis, and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:329.e1-329.e13; quiz 341-342.

- Suárez AL, Querfeld C, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: part II. therapy and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:343.e1-343.e11; quiz 355-356.

- Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

- Nakmura S, Jaffe ES, Swerdlow SH. EBV positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the elderly. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. 4th ed. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC); 2008:243-244.

- Kempf W, Sander CA. Classification of cutaneous lymphomas—an update. Histopathology. 2010;56:57-70.

- Castillo JJ, Beltran BE, Miranda RN, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the elderly: what we know so far. Oncologist. 2011;16:87-96.

- Oyama T, Ichimura K, Suzuki R, et al. Senile EBV+ B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders: a clinicopathologic study of 22 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:16-26.

- Ok CY, Papathomas TG, Medeiros LJ, et al. EBV-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the elderly. Blood. 2013;122:328-340.

- Tokuda Y, Fukushima M, Nakazawa K, et al. A case of primary Epstein-Barr virus-associated cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma unassociated with iatrogenic or endogenous immune dysregulation. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:666-671.

- Oyama T, Yamamoto K, Asano N, et al. Age-related EBV-associated B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders constitute a distinct clinicopathologic group: a study of 96 patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5124-5132.

- Eminger LA, Hall LD, Hesterman KS, et al. Epstein-Barr virus: dermatologic associations and implications. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:21-34.

- Martin B, Whittaker S, Morris S, et al. A case of primary cutaneous senile EBV-related diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:190-193.

- Gibson SE, Hsi ED. Epstein-Barr virus-positive B-cell lymphoma of the elderly at a United States tertiary medical center: an uncommon aggressive lymphoma with a nongerminal center B-cell phenotype. Hum Pathol. 2009;40:653-661.

- Castillo JJ, Bibas M, Miranda RN. The biology and treatment of plasmablastic lymphoma. Blood. 2015;125:2323-2330.

- Kim YH, Willemze R, Pimpinelli N, et al. TNM classification system for primary cutaneous lymphomas other than mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: a proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Blood. 2007;110:479-484.

- Suárez AL, Pulitzer M, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: part I. clinical features, diagnosis, and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:329.e1-329.e13; quiz 341-342.

- Suárez AL, Querfeld C, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: part II. therapy and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:343.e1-343.e11; quiz 355-356.

Practice Points

- Primary cutaneous lymphomas are malignant lymphomas confined to the skin.

- Complete staging workup is necessary to rule out secondary involvement of the skin from a nodal lymphoma.

- Epstein-Barr virus-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is a rare and aggressive primary cutaneous lymphoma.

Angioimmunoblastic T-Cell Lymphoma Mimicking Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL) is a rare, often aggressive type of peripheral T-cell lymphoma. It comprises 18% of peripheral T-cell lymphomas and 1% to 2% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas.1 The incidence of AITL in the United States is estimated to be 0.05 cases per 100,000 person-years,2 and there is a slight male predominance.1,3,4 It typically presents in the seventh decade of life; however, cases have been reported in adults ranging from 20 to 91 years of age.3

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma presents with lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, and systemic B symptoms (eg, fever, night sweats, weight loss, generalized pruritus).4-6 There are cutaneous manifestations in up to 50% of cases4,5,7 and frequently signs of autoimmune disorder.4,5 The diagnosis often is made by excisional lymph node biopsy. Lymph node specimens characteristically have a mixed inflammatory infiltrate that includes numerous B cells often infected with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and a relatively small population of atypical T lymphocytes.8 Identification of this neoplastic population of CD4+CD8− T lymphocytes expressing normal follicular helper T-cell markers CD10, chemokine CXCL13, programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), and B-cell lymphoma 6 (BCL-6) confirms the diagnosis of AITL.9,10 These malignant cells can be identified in skin specimens in cases of cutaneous metastatic disease.11,12 We present a case originally misdiagnosed as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma that was later identified as AITL on skin biopsy.

Case Report

A 72-year-old woman presented with a pruritic erythematous eruption around the neck of 3 weeks’ duration (Figure 1). Her medical history was notable for diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma diagnosed 3 months prior based on results from a right cervical lymph node biopsy. She was treated with bendamustine and rituximab. On physical examination there were erythematous edematous papules coalescing into indurated plaques around the neck. The differential diagnosis included drug hypersensitivity reaction, herpes zoster, urticaria, and cutaneous metastasis. Two punch biopsies were taken for hematoxylin and eosin and tissue culture.

Tissue cultures and viral polymerase chain reaction were negative. Histopathologic examination revealed a scant atypical lymphoid infiltrate focally involving the deep dermis. The cells were medium to large in size and contained hyperchromatic pleomorphic nuclei (Figure 2). They were positive for CD3 and CD4, which was concerning for T-cell lymphoma. The histologic report of the excisional lymph node biopsy done 3 months prior described an atypical lymphoid neoplasm with extensive necrosis and extranodal spread that stained positively for CD20 (Figure 3).

Further staining of this cervical lymph node specimen revealed large atypical lymphoid cells positive for CD3, CD10, B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2), BCL-6, and PD-1. There were intermixed mature B lymphocytes positive for CD20 and BCL-2. Chromogenic in situ hybridization with probes for EBV showed numerous positive cells throughout the infiltrate. Polymerase chain reaction demonstrated a T-cell population with clonally rearranged T-cell receptor genes. Primers for immunoglobulin heavy and light chains showed no evidence of a clonal B-cell population.

Additional staining of the atypical cutaneous lymphocytes revealed positivity for CD3, CD10, and PD-1. The morphologic and immunophenotypic findings of both specimens supported the diagnosis of AITL.

The patient declined further treatment and chose hospice care.

Comment

Etiology

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma was originally named angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy with dysproteinemia. It was initially thought to be a benign hyperreactive immune process driven by B cells, and patients often died of infectious complications not long after the diagnosis was made.13 As more cases were reported with clonal rearrangements and signs of progressive lymphoma, AITL was recognized as a malignancy.

Presentation

Patients with AITL often present with advanced stage III or IV disease with extranodal and bone marrow involvement.3-6 Cutaneous disease occurs in up to half of patients and portends a poor prognosis.7 The rash often is a nonspecific erythematous macular and papular eruption mimicking a morbilliform viral exanthem or drug reaction. Urticarial, nodular, petechial, purpuric, eczematous, erythrodermic, and vesiculobullous presentations have been described.4,11,12 In up to one-third of cases, the eruption occurs in association with a new medication, often leading to an initial misdiagnosis of drug hypersensitivity reaction.4,11 In a review conducted by Balaraman et al,14 84% of patients with AITL reported having pruritus.

There is an association of autoimmune phenomena in patients with AITL, which is likely a result of immune dysregulation associated with poorly functioning follicular helper T cells. Patients may present with arthralgia, hemolytic anemia, or thrombocytopenic purpura. Hypergammaglobulinemia has been reported in 30% to 50% of AITL patients.4,6 Other pertinent immunologic findings include positive Coombs test, cold agglutinins, cryoglobulinemia, hypocomplementemia, and positive antinuclear antibodies.4-7

Gene Analysis

Affected lymph nodes have a characteristically effaced architecture with proliferative arborizing venules; a hyperplastic population of follicular dendritic cells; and a mixed inflammatory infiltrate that is comprised of atypical lymphocytes and variable numbers of reactive lymphocytes, histiocytes, eosinophils, and plasma cells. The malignant T lymphocytes often account for only a small portion of the infiltrate.8 T-cell gene rearrangement studies identify clonal cells with β and γ rearrangements in the majority of cases.4 These cells are predominantly CD4+CD8− and express normal follicular helper T-cell markers CD10, CXCL13, BCL-6,5,9 and PD-1.10 Numerous B cells are seen intermixed with follicular dendritic cells. They are frequently infected with EBV and can have an atypical Reed-Sternberg cell–like appearance.4,5,15 In the evaluation of AITL, polymerase chain reaction studies with primers for immunoglobulin heavy and light chain should be performed to look for clonal B-cell populations and rule out a possible secondary B-cell lymphoma.

Histology

Five histologic patterns have been described with cutaneous AITL: (1) superficial perivascular infiltrate of eosinophils and lymphocytes that lack atypia, (2) sparse perivascular infiltrate with atypical lymphocytes, (3) dense dermal infiltrate of pleomorphic lymphocytes, (4) leukocytoclastic vasculitis without atypical lymphocytes,11 and (5) necrotizing vasculitis.12 The finding of vascular hyperplasia, perivascular infiltrate, or vasculitis has been reported in 91% of cases in the literature. Although these findings are nonspecific, an analysis of cutaneous cases reported in the literature found that 87% demonstrated T-cell receptor gene rearrangements.14 Lymphoid cells are positive for CD10 and PD-1, as was demonstrated in our case, and are CXCL13 positive in the majority of cases.12 Atypical and EBV-infected B cells also can be found in the skin.11,12

Differential Diagnosis

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma can mimic infectious, autoimmune, or allergic etiologies, and misdiagnosis of another type of lymphoma is not uncommon, as occurred in our case. Patients who have a delay in the correct diagnosis have similar outcomes to those correctly diagnosed at first presentation.4

Treatment

There are no effective therapies for AITL. Poor prognostic factors include age (>60 years), stages III to IV disease, male gender, elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase level,3,5,10 and cutaneous involvement.7 Corticosteroids, anthracycline-based chemotherapy, and autologous stem cell transplant are currently the mainstays of therapy. Initial response to chemotherapy is promising, but duration of response is poor overall and there is no increased survival.5,15 A large population-based study of 1207 cases by Xu and Liu3 showed the overall survival rate at 2 and 10 years was 46.8% and 21.9%, respectively. Ten-year disease-specific survival was 35.9%, and there was no demonstrable improvement in survival over the last 2 decades.3 Case reports have demonstrated that thalidomide,16 lenalidomide,17 and cyclosporine plus dexamethasone18 have been successfully used to achieve remission for up to 3 years.

Conclusion

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma is difficult to diagnose due to nonspecific clinical and histologic findings. Cutaneous manifestations are seen in AITL in up to half of cases that may occur early or in advanced disease. Similar to all cutaneous metastases, the appearance of the lesions can greatly vary. Our case demonstrates that dermatologists and dermatopathologists can make this diagnosis in the appropriate clinicopathologic context utilizing appropriate immunohistochemical staining and gene rearrangement studies.

- Rudiger T, Weisenburger DD, Anderson JR, et al. Peripheral T-cell lymphoma (excluding anaplastic large-cell lymphoma): results from the Non-Hodgkins Lymphoma Classification Project. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:140-149.

- Morton LM, Wang SS, Devesa SS, et al. Lymphoma incidence patterns by WHO subtype in the United States, 1992-2001. Blood. 2006;107:265-276.

- Xu B, Liu P. No survival improvement for patients with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma over the past two decades: a population-based study of 1207 cases. PLoS One. 2014;9:e92585.

- Lachenal F, Berger F, Ghesquieres H, et al. Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: clinical and laboratory features at diagnosis in 77 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2007;86:282-292.

- Mourad N, Mounier N, Briére J, et al. Clinical, biologic, and pathologic features in 157 patients with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma treated within the Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes de l’Adulte (GELA) trials. Blood. 2008;111:4463-4470.

- Frederico M, Rudiger T, Bellei M, et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: analysis of the International Peripheral T-cell Lymphoma Project. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:240-246.

- Siegert W, Nerl C, Agthe A, et al. Angioimmunoblastic lym-phadenopathy (AILD)-type T-cell lymphoma: prognostic impact of clinical observations and laboratory findings at presentation. The Kiel Lymphoma Study Group. Ann Oncol. 1995;6:659-664.

- Attygalle AD, Chuang SS, Diss TC, et al. Distinguishing angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma from peripheral T-cell lymphoma, unspecified, using morphology, immunophenotype, and molecular genetics. Histopathology. 2007;50:498-508.

- Dupuis J, Boye K, Martin N, et al. Expression of CXCL13 by neoplastic cells in angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL): a new diagnostic marker providing evidence that AITL derives from follicular helper cells. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:490-494.

- Odejide O, Weigert O, Lane AA, et al. A targeted mutational landscape of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2014;123:1293-1296.

- Martel P, Laroche L, Courville P, et al. Cutaneous involvementin patients with angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy with dysproteinemia: a clinical, immunohistological, and molecular analysis. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:881-886.

- Ortonne N, Dupuis J, Plonquet A, et al. Characterization of CXCL13+ neoplastic t cells in cutaneous lesions of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL). Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1068-1076.

- Frizzera G, Moran E, Rappaport H. Angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy with dysproteinemia. Lancet. 1974;1:1070-1073.

- Balaraman B, Conley JA, Sheinbein DM. Evaluation of cutaneous angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma [published online May 6, 2011]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:855-862.

- Tokunaga T, Shimada K, Yamamoto K, et al. Retrospective analysis of prognostic factors for angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: a multicenter cooperative study in Japan. Blood. 2012;119:2837-2843.

- Dogan A, Ngu LSP, Ng SH, et al. Pathology and clinical features of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma after successful treatment with thalidomide. Leukemia. 2005;19:873-875.

- Fabbri A, Cencini E, Pietrini A, et al. Impressive activity of lenalidomide monotherapy in refractory angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: report of a case with long-term follow-up. Hematol Oncol. 2013;31:213-217.

- Kobayashi T, Kuroda J, Uchiyama H, et al. Successful treatment of chemotherapy-refractory angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma with cyclosporin A. Acta Haematol. 2012;127:10-15.

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL) is a rare, often aggressive type of peripheral T-cell lymphoma. It comprises 18% of peripheral T-cell lymphomas and 1% to 2% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas.1 The incidence of AITL in the United States is estimated to be 0.05 cases per 100,000 person-years,2 and there is a slight male predominance.1,3,4 It typically presents in the seventh decade of life; however, cases have been reported in adults ranging from 20 to 91 years of age.3

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma presents with lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, and systemic B symptoms (eg, fever, night sweats, weight loss, generalized pruritus).4-6 There are cutaneous manifestations in up to 50% of cases4,5,7 and frequently signs of autoimmune disorder.4,5 The diagnosis often is made by excisional lymph node biopsy. Lymph node specimens characteristically have a mixed inflammatory infiltrate that includes numerous B cells often infected with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and a relatively small population of atypical T lymphocytes.8 Identification of this neoplastic population of CD4+CD8− T lymphocytes expressing normal follicular helper T-cell markers CD10, chemokine CXCL13, programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), and B-cell lymphoma 6 (BCL-6) confirms the diagnosis of AITL.9,10 These malignant cells can be identified in skin specimens in cases of cutaneous metastatic disease.11,12 We present a case originally misdiagnosed as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma that was later identified as AITL on skin biopsy.

Case Report

A 72-year-old woman presented with a pruritic erythematous eruption around the neck of 3 weeks’ duration (Figure 1). Her medical history was notable for diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma diagnosed 3 months prior based on results from a right cervical lymph node biopsy. She was treated with bendamustine and rituximab. On physical examination there were erythematous edematous papules coalescing into indurated plaques around the neck. The differential diagnosis included drug hypersensitivity reaction, herpes zoster, urticaria, and cutaneous metastasis. Two punch biopsies were taken for hematoxylin and eosin and tissue culture.

Tissue cultures and viral polymerase chain reaction were negative. Histopathologic examination revealed a scant atypical lymphoid infiltrate focally involving the deep dermis. The cells were medium to large in size and contained hyperchromatic pleomorphic nuclei (Figure 2). They were positive for CD3 and CD4, which was concerning for T-cell lymphoma. The histologic report of the excisional lymph node biopsy done 3 months prior described an atypical lymphoid neoplasm with extensive necrosis and extranodal spread that stained positively for CD20 (Figure 3).

Further staining of this cervical lymph node specimen revealed large atypical lymphoid cells positive for CD3, CD10, B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2), BCL-6, and PD-1. There were intermixed mature B lymphocytes positive for CD20 and BCL-2. Chromogenic in situ hybridization with probes for EBV showed numerous positive cells throughout the infiltrate. Polymerase chain reaction demonstrated a T-cell population with clonally rearranged T-cell receptor genes. Primers for immunoglobulin heavy and light chains showed no evidence of a clonal B-cell population.

Additional staining of the atypical cutaneous lymphocytes revealed positivity for CD3, CD10, and PD-1. The morphologic and immunophenotypic findings of both specimens supported the diagnosis of AITL.

The patient declined further treatment and chose hospice care.

Comment

Etiology

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma was originally named angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy with dysproteinemia. It was initially thought to be a benign hyperreactive immune process driven by B cells, and patients often died of infectious complications not long after the diagnosis was made.13 As more cases were reported with clonal rearrangements and signs of progressive lymphoma, AITL was recognized as a malignancy.

Presentation

Patients with AITL often present with advanced stage III or IV disease with extranodal and bone marrow involvement.3-6 Cutaneous disease occurs in up to half of patients and portends a poor prognosis.7 The rash often is a nonspecific erythematous macular and papular eruption mimicking a morbilliform viral exanthem or drug reaction. Urticarial, nodular, petechial, purpuric, eczematous, erythrodermic, and vesiculobullous presentations have been described.4,11,12 In up to one-third of cases, the eruption occurs in association with a new medication, often leading to an initial misdiagnosis of drug hypersensitivity reaction.4,11 In a review conducted by Balaraman et al,14 84% of patients with AITL reported having pruritus.

There is an association of autoimmune phenomena in patients with AITL, which is likely a result of immune dysregulation associated with poorly functioning follicular helper T cells. Patients may present with arthralgia, hemolytic anemia, or thrombocytopenic purpura. Hypergammaglobulinemia has been reported in 30% to 50% of AITL patients.4,6 Other pertinent immunologic findings include positive Coombs test, cold agglutinins, cryoglobulinemia, hypocomplementemia, and positive antinuclear antibodies.4-7

Gene Analysis

Affected lymph nodes have a characteristically effaced architecture with proliferative arborizing venules; a hyperplastic population of follicular dendritic cells; and a mixed inflammatory infiltrate that is comprised of atypical lymphocytes and variable numbers of reactive lymphocytes, histiocytes, eosinophils, and plasma cells. The malignant T lymphocytes often account for only a small portion of the infiltrate.8 T-cell gene rearrangement studies identify clonal cells with β and γ rearrangements in the majority of cases.4 These cells are predominantly CD4+CD8− and express normal follicular helper T-cell markers CD10, CXCL13, BCL-6,5,9 and PD-1.10 Numerous B cells are seen intermixed with follicular dendritic cells. They are frequently infected with EBV and can have an atypical Reed-Sternberg cell–like appearance.4,5,15 In the evaluation of AITL, polymerase chain reaction studies with primers for immunoglobulin heavy and light chain should be performed to look for clonal B-cell populations and rule out a possible secondary B-cell lymphoma.

Histology

Five histologic patterns have been described with cutaneous AITL: (1) superficial perivascular infiltrate of eosinophils and lymphocytes that lack atypia, (2) sparse perivascular infiltrate with atypical lymphocytes, (3) dense dermal infiltrate of pleomorphic lymphocytes, (4) leukocytoclastic vasculitis without atypical lymphocytes,11 and (5) necrotizing vasculitis.12 The finding of vascular hyperplasia, perivascular infiltrate, or vasculitis has been reported in 91% of cases in the literature. Although these findings are nonspecific, an analysis of cutaneous cases reported in the literature found that 87% demonstrated T-cell receptor gene rearrangements.14 Lymphoid cells are positive for CD10 and PD-1, as was demonstrated in our case, and are CXCL13 positive in the majority of cases.12 Atypical and EBV-infected B cells also can be found in the skin.11,12

Differential Diagnosis

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma can mimic infectious, autoimmune, or allergic etiologies, and misdiagnosis of another type of lymphoma is not uncommon, as occurred in our case. Patients who have a delay in the correct diagnosis have similar outcomes to those correctly diagnosed at first presentation.4

Treatment

There are no effective therapies for AITL. Poor prognostic factors include age (>60 years), stages III to IV disease, male gender, elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase level,3,5,10 and cutaneous involvement.7 Corticosteroids, anthracycline-based chemotherapy, and autologous stem cell transplant are currently the mainstays of therapy. Initial response to chemotherapy is promising, but duration of response is poor overall and there is no increased survival.5,15 A large population-based study of 1207 cases by Xu and Liu3 showed the overall survival rate at 2 and 10 years was 46.8% and 21.9%, respectively. Ten-year disease-specific survival was 35.9%, and there was no demonstrable improvement in survival over the last 2 decades.3 Case reports have demonstrated that thalidomide,16 lenalidomide,17 and cyclosporine plus dexamethasone18 have been successfully used to achieve remission for up to 3 years.

Conclusion

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma is difficult to diagnose due to nonspecific clinical and histologic findings. Cutaneous manifestations are seen in AITL in up to half of cases that may occur early or in advanced disease. Similar to all cutaneous metastases, the appearance of the lesions can greatly vary. Our case demonstrates that dermatologists and dermatopathologists can make this diagnosis in the appropriate clinicopathologic context utilizing appropriate immunohistochemical staining and gene rearrangement studies.

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL) is a rare, often aggressive type of peripheral T-cell lymphoma. It comprises 18% of peripheral T-cell lymphomas and 1% to 2% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas.1 The incidence of AITL in the United States is estimated to be 0.05 cases per 100,000 person-years,2 and there is a slight male predominance.1,3,4 It typically presents in the seventh decade of life; however, cases have been reported in adults ranging from 20 to 91 years of age.3

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma presents with lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, and systemic B symptoms (eg, fever, night sweats, weight loss, generalized pruritus).4-6 There are cutaneous manifestations in up to 50% of cases4,5,7 and frequently signs of autoimmune disorder.4,5 The diagnosis often is made by excisional lymph node biopsy. Lymph node specimens characteristically have a mixed inflammatory infiltrate that includes numerous B cells often infected with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and a relatively small population of atypical T lymphocytes.8 Identification of this neoplastic population of CD4+CD8− T lymphocytes expressing normal follicular helper T-cell markers CD10, chemokine CXCL13, programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), and B-cell lymphoma 6 (BCL-6) confirms the diagnosis of AITL.9,10 These malignant cells can be identified in skin specimens in cases of cutaneous metastatic disease.11,12 We present a case originally misdiagnosed as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma that was later identified as AITL on skin biopsy.

Case Report

A 72-year-old woman presented with a pruritic erythematous eruption around the neck of 3 weeks’ duration (Figure 1). Her medical history was notable for diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma diagnosed 3 months prior based on results from a right cervical lymph node biopsy. She was treated with bendamustine and rituximab. On physical examination there were erythematous edematous papules coalescing into indurated plaques around the neck. The differential diagnosis included drug hypersensitivity reaction, herpes zoster, urticaria, and cutaneous metastasis. Two punch biopsies were taken for hematoxylin and eosin and tissue culture.

Tissue cultures and viral polymerase chain reaction were negative. Histopathologic examination revealed a scant atypical lymphoid infiltrate focally involving the deep dermis. The cells were medium to large in size and contained hyperchromatic pleomorphic nuclei (Figure 2). They were positive for CD3 and CD4, which was concerning for T-cell lymphoma. The histologic report of the excisional lymph node biopsy done 3 months prior described an atypical lymphoid neoplasm with extensive necrosis and extranodal spread that stained positively for CD20 (Figure 3).

Further staining of this cervical lymph node specimen revealed large atypical lymphoid cells positive for CD3, CD10, B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2), BCL-6, and PD-1. There were intermixed mature B lymphocytes positive for CD20 and BCL-2. Chromogenic in situ hybridization with probes for EBV showed numerous positive cells throughout the infiltrate. Polymerase chain reaction demonstrated a T-cell population with clonally rearranged T-cell receptor genes. Primers for immunoglobulin heavy and light chains showed no evidence of a clonal B-cell population.

Additional staining of the atypical cutaneous lymphocytes revealed positivity for CD3, CD10, and PD-1. The morphologic and immunophenotypic findings of both specimens supported the diagnosis of AITL.

The patient declined further treatment and chose hospice care.

Comment

Etiology

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma was originally named angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy with dysproteinemia. It was initially thought to be a benign hyperreactive immune process driven by B cells, and patients often died of infectious complications not long after the diagnosis was made.13 As more cases were reported with clonal rearrangements and signs of progressive lymphoma, AITL was recognized as a malignancy.

Presentation

Patients with AITL often present with advanced stage III or IV disease with extranodal and bone marrow involvement.3-6 Cutaneous disease occurs in up to half of patients and portends a poor prognosis.7 The rash often is a nonspecific erythematous macular and papular eruption mimicking a morbilliform viral exanthem or drug reaction. Urticarial, nodular, petechial, purpuric, eczematous, erythrodermic, and vesiculobullous presentations have been described.4,11,12 In up to one-third of cases, the eruption occurs in association with a new medication, often leading to an initial misdiagnosis of drug hypersensitivity reaction.4,11 In a review conducted by Balaraman et al,14 84% of patients with AITL reported having pruritus.

There is an association of autoimmune phenomena in patients with AITL, which is likely a result of immune dysregulation associated with poorly functioning follicular helper T cells. Patients may present with arthralgia, hemolytic anemia, or thrombocytopenic purpura. Hypergammaglobulinemia has been reported in 30% to 50% of AITL patients.4,6 Other pertinent immunologic findings include positive Coombs test, cold agglutinins, cryoglobulinemia, hypocomplementemia, and positive antinuclear antibodies.4-7

Gene Analysis

Affected lymph nodes have a characteristically effaced architecture with proliferative arborizing venules; a hyperplastic population of follicular dendritic cells; and a mixed inflammatory infiltrate that is comprised of atypical lymphocytes and variable numbers of reactive lymphocytes, histiocytes, eosinophils, and plasma cells. The malignant T lymphocytes often account for only a small portion of the infiltrate.8 T-cell gene rearrangement studies identify clonal cells with β and γ rearrangements in the majority of cases.4 These cells are predominantly CD4+CD8− and express normal follicular helper T-cell markers CD10, CXCL13, BCL-6,5,9 and PD-1.10 Numerous B cells are seen intermixed with follicular dendritic cells. They are frequently infected with EBV and can have an atypical Reed-Sternberg cell–like appearance.4,5,15 In the evaluation of AITL, polymerase chain reaction studies with primers for immunoglobulin heavy and light chain should be performed to look for clonal B-cell populations and rule out a possible secondary B-cell lymphoma.

Histology

Five histologic patterns have been described with cutaneous AITL: (1) superficial perivascular infiltrate of eosinophils and lymphocytes that lack atypia, (2) sparse perivascular infiltrate with atypical lymphocytes, (3) dense dermal infiltrate of pleomorphic lymphocytes, (4) leukocytoclastic vasculitis without atypical lymphocytes,11 and (5) necrotizing vasculitis.12 The finding of vascular hyperplasia, perivascular infiltrate, or vasculitis has been reported in 91% of cases in the literature. Although these findings are nonspecific, an analysis of cutaneous cases reported in the literature found that 87% demonstrated T-cell receptor gene rearrangements.14 Lymphoid cells are positive for CD10 and PD-1, as was demonstrated in our case, and are CXCL13 positive in the majority of cases.12 Atypical and EBV-infected B cells also can be found in the skin.11,12

Differential Diagnosis

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma can mimic infectious, autoimmune, or allergic etiologies, and misdiagnosis of another type of lymphoma is not uncommon, as occurred in our case. Patients who have a delay in the correct diagnosis have similar outcomes to those correctly diagnosed at first presentation.4

Treatment

There are no effective therapies for AITL. Poor prognostic factors include age (>60 years), stages III to IV disease, male gender, elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase level,3,5,10 and cutaneous involvement.7 Corticosteroids, anthracycline-based chemotherapy, and autologous stem cell transplant are currently the mainstays of therapy. Initial response to chemotherapy is promising, but duration of response is poor overall and there is no increased survival.5,15 A large population-based study of 1207 cases by Xu and Liu3 showed the overall survival rate at 2 and 10 years was 46.8% and 21.9%, respectively. Ten-year disease-specific survival was 35.9%, and there was no demonstrable improvement in survival over the last 2 decades.3 Case reports have demonstrated that thalidomide,16 lenalidomide,17 and cyclosporine plus dexamethasone18 have been successfully used to achieve remission for up to 3 years.

Conclusion

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma is difficult to diagnose due to nonspecific clinical and histologic findings. Cutaneous manifestations are seen in AITL in up to half of cases that may occur early or in advanced disease. Similar to all cutaneous metastases, the appearance of the lesions can greatly vary. Our case demonstrates that dermatologists and dermatopathologists can make this diagnosis in the appropriate clinicopathologic context utilizing appropriate immunohistochemical staining and gene rearrangement studies.

- Rudiger T, Weisenburger DD, Anderson JR, et al. Peripheral T-cell lymphoma (excluding anaplastic large-cell lymphoma): results from the Non-Hodgkins Lymphoma Classification Project. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:140-149.

- Morton LM, Wang SS, Devesa SS, et al. Lymphoma incidence patterns by WHO subtype in the United States, 1992-2001. Blood. 2006;107:265-276.

- Xu B, Liu P. No survival improvement for patients with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma over the past two decades: a population-based study of 1207 cases. PLoS One. 2014;9:e92585.

- Lachenal F, Berger F, Ghesquieres H, et al. Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: clinical and laboratory features at diagnosis in 77 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2007;86:282-292.

- Mourad N, Mounier N, Briére J, et al. Clinical, biologic, and pathologic features in 157 patients with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma treated within the Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes de l’Adulte (GELA) trials. Blood. 2008;111:4463-4470.

- Frederico M, Rudiger T, Bellei M, et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: analysis of the International Peripheral T-cell Lymphoma Project. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:240-246.

- Siegert W, Nerl C, Agthe A, et al. Angioimmunoblastic lym-phadenopathy (AILD)-type T-cell lymphoma: prognostic impact of clinical observations and laboratory findings at presentation. The Kiel Lymphoma Study Group. Ann Oncol. 1995;6:659-664.

- Attygalle AD, Chuang SS, Diss TC, et al. Distinguishing angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma from peripheral T-cell lymphoma, unspecified, using morphology, immunophenotype, and molecular genetics. Histopathology. 2007;50:498-508.

- Dupuis J, Boye K, Martin N, et al. Expression of CXCL13 by neoplastic cells in angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL): a new diagnostic marker providing evidence that AITL derives from follicular helper cells. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:490-494.

- Odejide O, Weigert O, Lane AA, et al. A targeted mutational landscape of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2014;123:1293-1296.

- Martel P, Laroche L, Courville P, et al. Cutaneous involvementin patients with angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy with dysproteinemia: a clinical, immunohistological, and molecular analysis. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:881-886.

- Ortonne N, Dupuis J, Plonquet A, et al. Characterization of CXCL13+ neoplastic t cells in cutaneous lesions of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL). Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1068-1076.

- Frizzera G, Moran E, Rappaport H. Angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy with dysproteinemia. Lancet. 1974;1:1070-1073.

- Balaraman B, Conley JA, Sheinbein DM. Evaluation of cutaneous angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma [published online May 6, 2011]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:855-862.

- Tokunaga T, Shimada K, Yamamoto K, et al. Retrospective analysis of prognostic factors for angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: a multicenter cooperative study in Japan. Blood. 2012;119:2837-2843.

- Dogan A, Ngu LSP, Ng SH, et al. Pathology and clinical features of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma after successful treatment with thalidomide. Leukemia. 2005;19:873-875.

- Fabbri A, Cencini E, Pietrini A, et al. Impressive activity of lenalidomide monotherapy in refractory angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: report of a case with long-term follow-up. Hematol Oncol. 2013;31:213-217.

- Kobayashi T, Kuroda J, Uchiyama H, et al. Successful treatment of chemotherapy-refractory angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma with cyclosporin A. Acta Haematol. 2012;127:10-15.

- Rudiger T, Weisenburger DD, Anderson JR, et al. Peripheral T-cell lymphoma (excluding anaplastic large-cell lymphoma): results from the Non-Hodgkins Lymphoma Classification Project. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:140-149.

- Morton LM, Wang SS, Devesa SS, et al. Lymphoma incidence patterns by WHO subtype in the United States, 1992-2001. Blood. 2006;107:265-276.

- Xu B, Liu P. No survival improvement for patients with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma over the past two decades: a population-based study of 1207 cases. PLoS One. 2014;9:e92585.

- Lachenal F, Berger F, Ghesquieres H, et al. Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: clinical and laboratory features at diagnosis in 77 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2007;86:282-292.

- Mourad N, Mounier N, Briére J, et al. Clinical, biologic, and pathologic features in 157 patients with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma treated within the Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes de l’Adulte (GELA) trials. Blood. 2008;111:4463-4470.

- Frederico M, Rudiger T, Bellei M, et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: analysis of the International Peripheral T-cell Lymphoma Project. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:240-246.

- Siegert W, Nerl C, Agthe A, et al. Angioimmunoblastic lym-phadenopathy (AILD)-type T-cell lymphoma: prognostic impact of clinical observations and laboratory findings at presentation. The Kiel Lymphoma Study Group. Ann Oncol. 1995;6:659-664.

- Attygalle AD, Chuang SS, Diss TC, et al. Distinguishing angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma from peripheral T-cell lymphoma, unspecified, using morphology, immunophenotype, and molecular genetics. Histopathology. 2007;50:498-508.

- Dupuis J, Boye K, Martin N, et al. Expression of CXCL13 by neoplastic cells in angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL): a new diagnostic marker providing evidence that AITL derives from follicular helper cells. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:490-494.

- Odejide O, Weigert O, Lane AA, et al. A targeted mutational landscape of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2014;123:1293-1296.

- Martel P, Laroche L, Courville P, et al. Cutaneous involvementin patients with angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy with dysproteinemia: a clinical, immunohistological, and molecular analysis. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:881-886.

- Ortonne N, Dupuis J, Plonquet A, et al. Characterization of CXCL13+ neoplastic t cells in cutaneous lesions of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL). Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1068-1076.

- Frizzera G, Moran E, Rappaport H. Angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy with dysproteinemia. Lancet. 1974;1:1070-1073.

- Balaraman B, Conley JA, Sheinbein DM. Evaluation of cutaneous angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma [published online May 6, 2011]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:855-862.

- Tokunaga T, Shimada K, Yamamoto K, et al. Retrospective analysis of prognostic factors for angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: a multicenter cooperative study in Japan. Blood. 2012;119:2837-2843.

- Dogan A, Ngu LSP, Ng SH, et al. Pathology and clinical features of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma after successful treatment with thalidomide. Leukemia. 2005;19:873-875.

- Fabbri A, Cencini E, Pietrini A, et al. Impressive activity of lenalidomide monotherapy in refractory angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: report of a case with long-term follow-up. Hematol Oncol. 2013;31:213-217.

- Kobayashi T, Kuroda J, Uchiyama H, et al. Successful treatment of chemotherapy-refractory angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma with cyclosporin A. Acta Haematol. 2012;127:10-15.

Practice Points

- Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL) is a rare, often aggressive type of peripheral T-cell lymphoma.

- Cutaneous manifestations have been seen in up to 50% of cases.

- Immunohistochemical markers for normal follicular helper T cells—CD-10, chemokine CXCL-13, and programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)—can be used to differentiate AITL from other types of lymphoma.

- The prognosis of AITL is poor.

Slow-growing, Asymptomatic, Annular Plaques on the Bilateral Palms

The Diagnosis: Circumscribed Palmar Hypokeratosis

Circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is a rare, benign, acquired dermatosis that was first described by Pérez et al1 in 2002 and is characterized by annular plaques with an atrophic center and hyperkeratotic edges. Classically, the lesions present on the thenar and hypothenar eminences of the palms.2 The condition predominantly affects women (4:1 ratio), with a mean age of onset of 65 years.3

Although the pathogenesis of circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is unknown, local trauma generally is considered to be the causative factor. Other hypotheses include human papillomaviruses 4 and 6 infection and primary abnormal keratinization in the epidermis.3 Immunohistochemical studies have demonstrated increased expression of keratin 16 and Ki-67 in cutaneous lesions, which is postulated to be responsible for keratinocyte fragility associated with epidermal hyperproliferation. Other reported cases have shown diminished keratin 9, keratin 2e, and connexin 26 expression, which normally are abundant in the acral epidermis. Abnormal expression of antigens associated with epidermal proliferation and differentiation also have been reported,3 suggesting that there is an altered regulation of the cutaneous desquamation process.

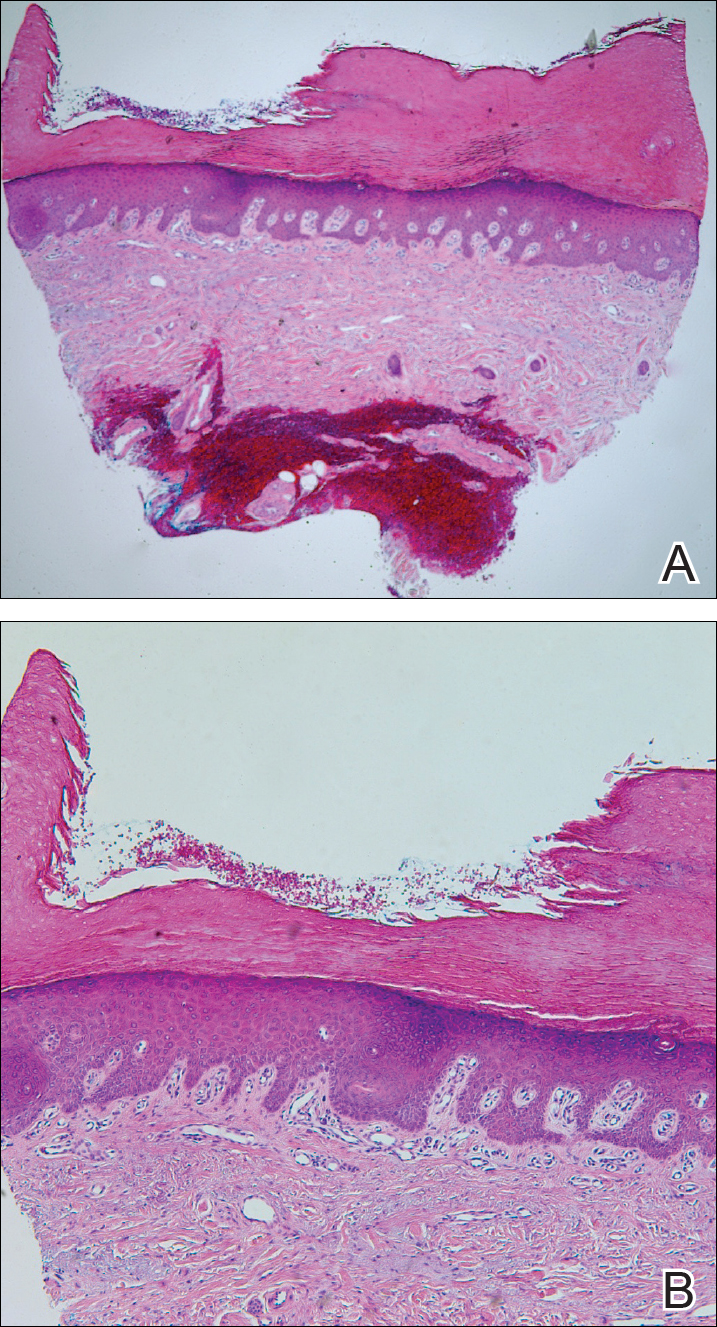

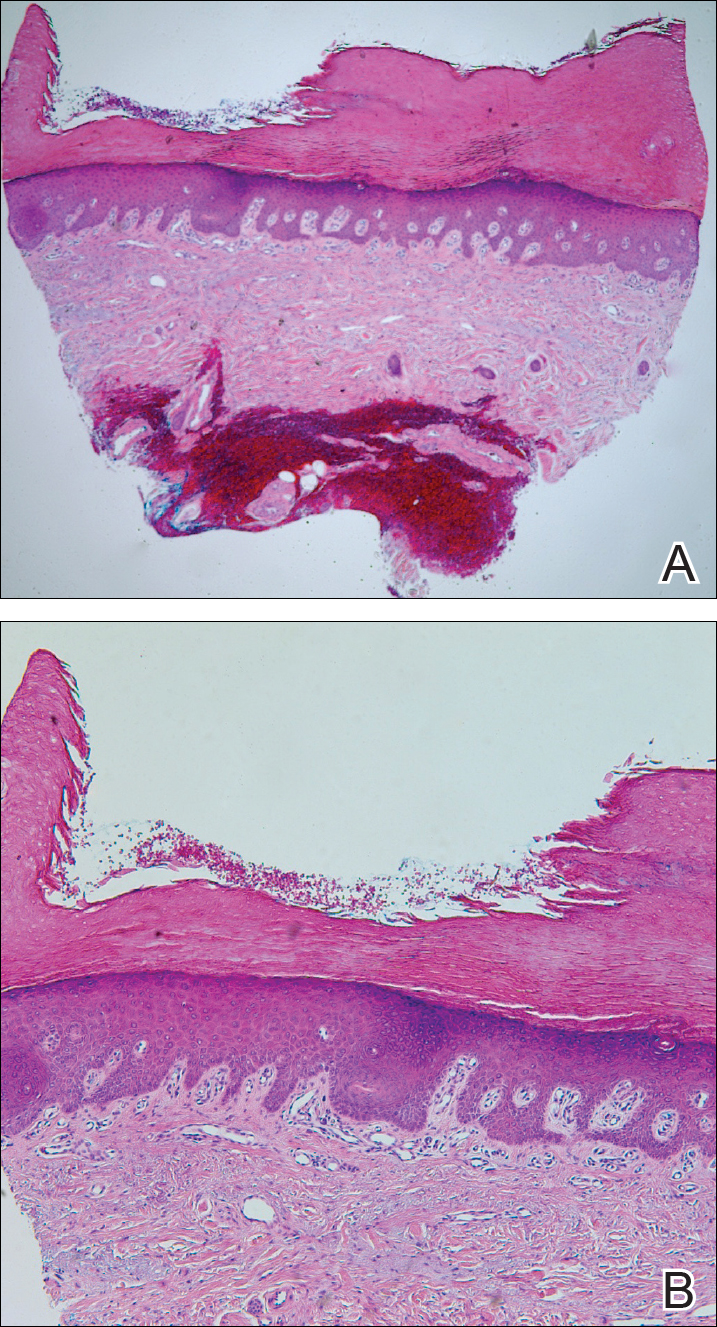

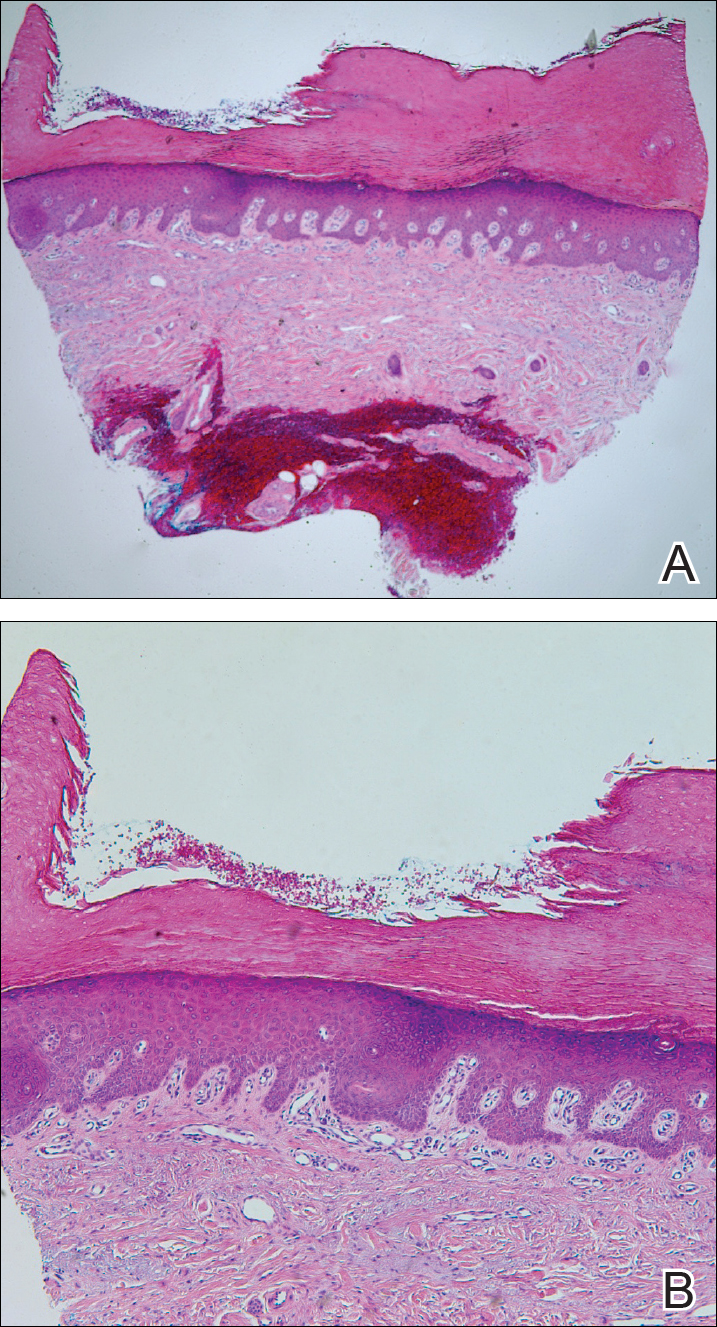

Histologically, circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is characterized by an abrupt reduction in the stratum corneum (Figure), forming a step between the lesion and the perilesional normal skin.2,3 The clinical appearance of erythema is due to visualization of dermal blood circulation in the area of corneal thinning and is not a result of vasodilation. The dermis is uninvolved, and inflammation is absent. The differential diagnosis includes psoriasis, Bowen disease, porokeratosis, and dermatophytosis.3

Circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is a chronic condition, and there are no known reports of development of malignancy. Treatment is not required but may include cryotherapy; topical therapy with corticosteroids, retinoids, urea, and calcipotriene; and photodynamic therapy. Circumscribed hypokeratosis should be included in the differential diagnosis of palmar lesions.

- Pérez A, Rütten A, Gold R, et al. Circumscribed palmar or plantar hypokeratosis: a distinctive epidermal malformation of the palms or soles. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:21-27.

- Mitkov M, Balagula Y, Lockshin B. Case report: circumscribed plantar hypokeratosis. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:E203-E205.

- Rocha L, Nico M. Circumscribed palmoplantar hypokeratosis: report of two Brazilian cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:623-626.

The Diagnosis: Circumscribed Palmar Hypokeratosis

Circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is a rare, benign, acquired dermatosis that was first described by Pérez et al1 in 2002 and is characterized by annular plaques with an atrophic center and hyperkeratotic edges. Classically, the lesions present on the thenar and hypothenar eminences of the palms.2 The condition predominantly affects women (4:1 ratio), with a mean age of onset of 65 years.3

Although the pathogenesis of circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is unknown, local trauma generally is considered to be the causative factor. Other hypotheses include human papillomaviruses 4 and 6 infection and primary abnormal keratinization in the epidermis.3 Immunohistochemical studies have demonstrated increased expression of keratin 16 and Ki-67 in cutaneous lesions, which is postulated to be responsible for keratinocyte fragility associated with epidermal hyperproliferation. Other reported cases have shown diminished keratin 9, keratin 2e, and connexin 26 expression, which normally are abundant in the acral epidermis. Abnormal expression of antigens associated with epidermal proliferation and differentiation also have been reported,3 suggesting that there is an altered regulation of the cutaneous desquamation process.

Histologically, circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is characterized by an abrupt reduction in the stratum corneum (Figure), forming a step between the lesion and the perilesional normal skin.2,3 The clinical appearance of erythema is due to visualization of dermal blood circulation in the area of corneal thinning and is not a result of vasodilation. The dermis is uninvolved, and inflammation is absent. The differential diagnosis includes psoriasis, Bowen disease, porokeratosis, and dermatophytosis.3

Circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is a chronic condition, and there are no known reports of development of malignancy. Treatment is not required but may include cryotherapy; topical therapy with corticosteroids, retinoids, urea, and calcipotriene; and photodynamic therapy. Circumscribed hypokeratosis should be included in the differential diagnosis of palmar lesions.

The Diagnosis: Circumscribed Palmar Hypokeratosis

Circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is a rare, benign, acquired dermatosis that was first described by Pérez et al1 in 2002 and is characterized by annular plaques with an atrophic center and hyperkeratotic edges. Classically, the lesions present on the thenar and hypothenar eminences of the palms.2 The condition predominantly affects women (4:1 ratio), with a mean age of onset of 65 years.3

Although the pathogenesis of circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is unknown, local trauma generally is considered to be the causative factor. Other hypotheses include human papillomaviruses 4 and 6 infection and primary abnormal keratinization in the epidermis.3 Immunohistochemical studies have demonstrated increased expression of keratin 16 and Ki-67 in cutaneous lesions, which is postulated to be responsible for keratinocyte fragility associated with epidermal hyperproliferation. Other reported cases have shown diminished keratin 9, keratin 2e, and connexin 26 expression, which normally are abundant in the acral epidermis. Abnormal expression of antigens associated with epidermal proliferation and differentiation also have been reported,3 suggesting that there is an altered regulation of the cutaneous desquamation process.

Histologically, circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is characterized by an abrupt reduction in the stratum corneum (Figure), forming a step between the lesion and the perilesional normal skin.2,3 The clinical appearance of erythema is due to visualization of dermal blood circulation in the area of corneal thinning and is not a result of vasodilation. The dermis is uninvolved, and inflammation is absent. The differential diagnosis includes psoriasis, Bowen disease, porokeratosis, and dermatophytosis.3

Circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is a chronic condition, and there are no known reports of development of malignancy. Treatment is not required but may include cryotherapy; topical therapy with corticosteroids, retinoids, urea, and calcipotriene; and photodynamic therapy. Circumscribed hypokeratosis should be included in the differential diagnosis of palmar lesions.

- Pérez A, Rütten A, Gold R, et al. Circumscribed palmar or plantar hypokeratosis: a distinctive epidermal malformation of the palms or soles. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:21-27.

- Mitkov M, Balagula Y, Lockshin B. Case report: circumscribed plantar hypokeratosis. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:E203-E205.

- Rocha L, Nico M. Circumscribed palmoplantar hypokeratosis: report of two Brazilian cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:623-626.