User login

Bleeding Hand Mass in an Older Man

The Diagnosis: Epithelioid Angiosarcoma

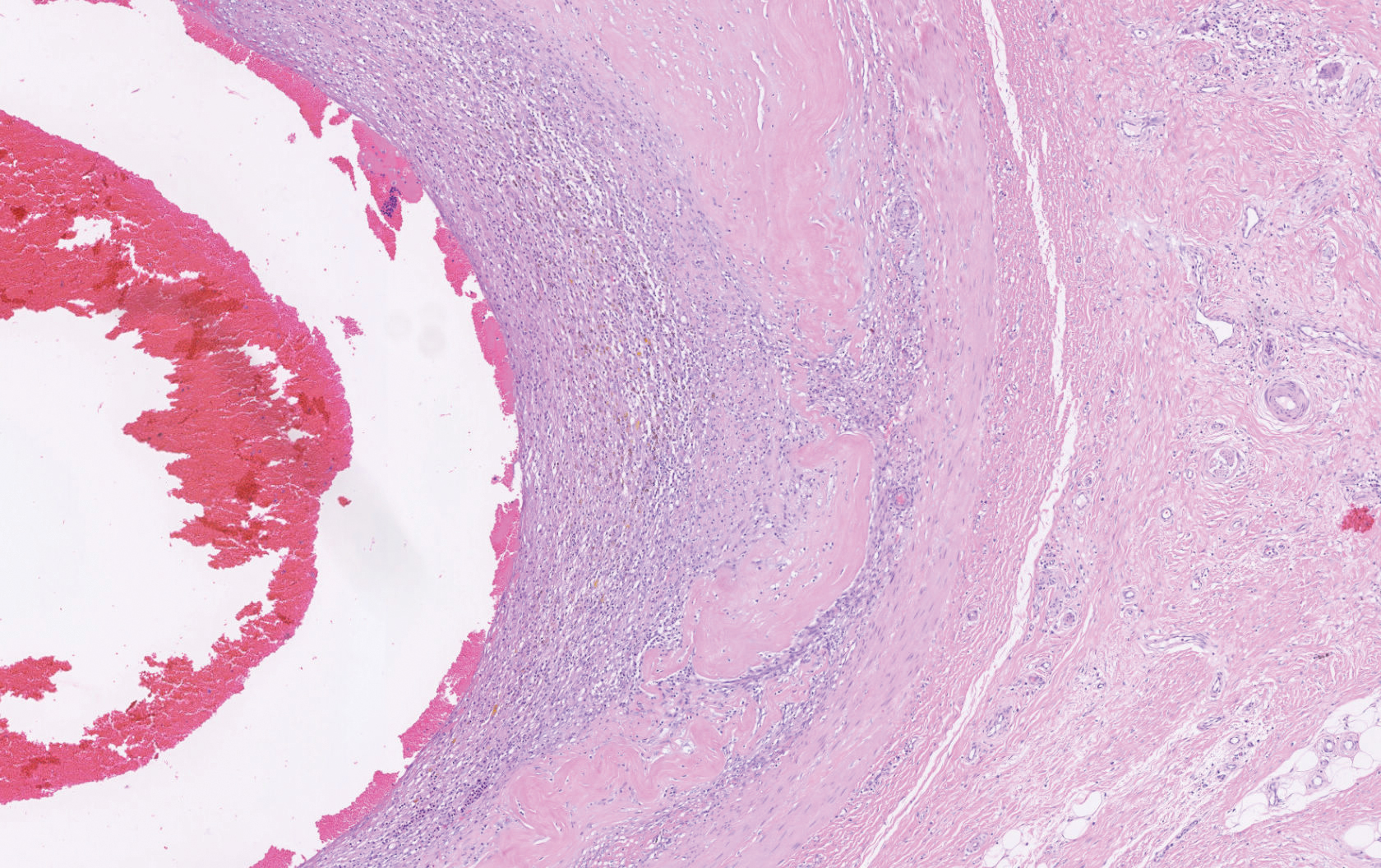

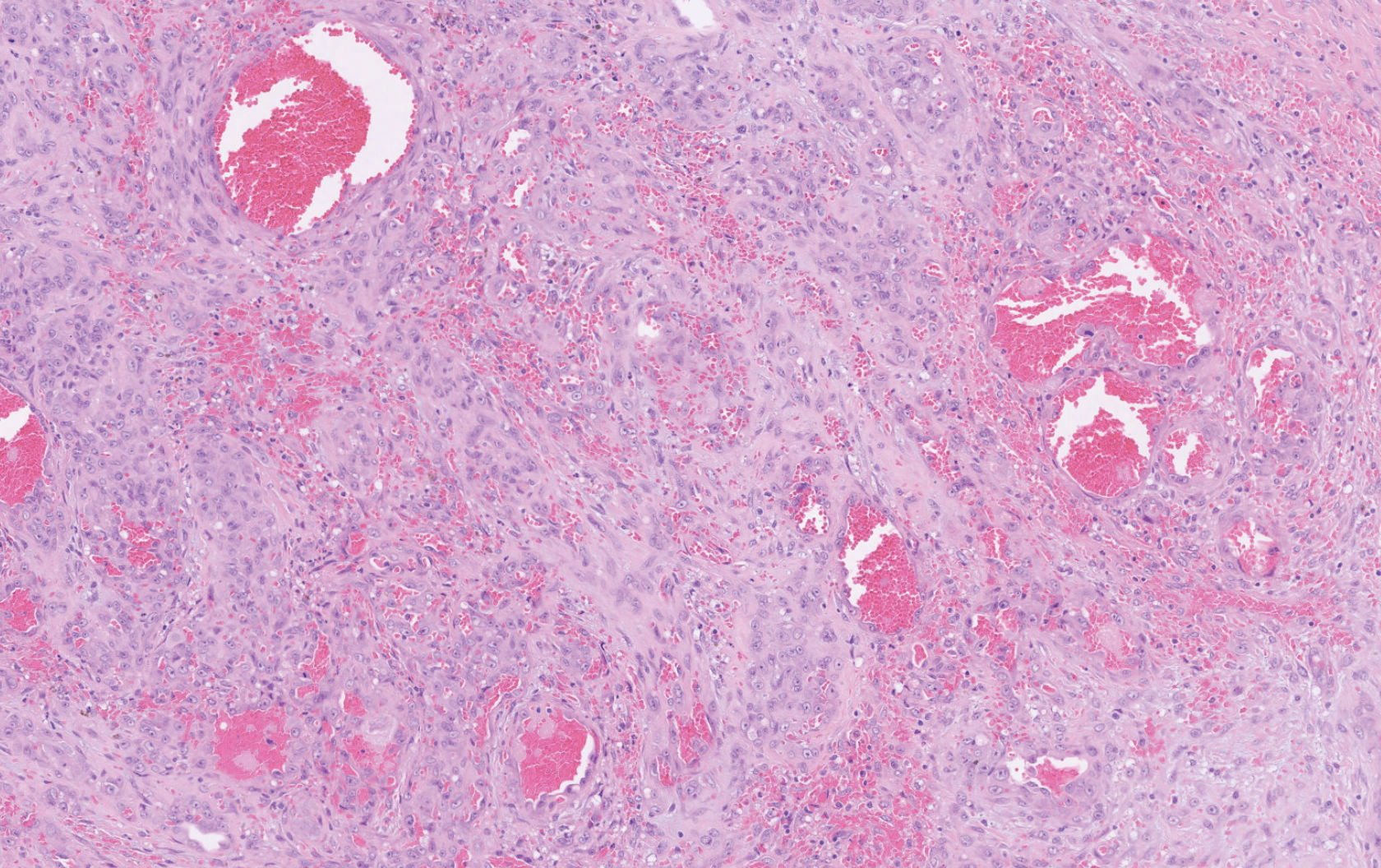

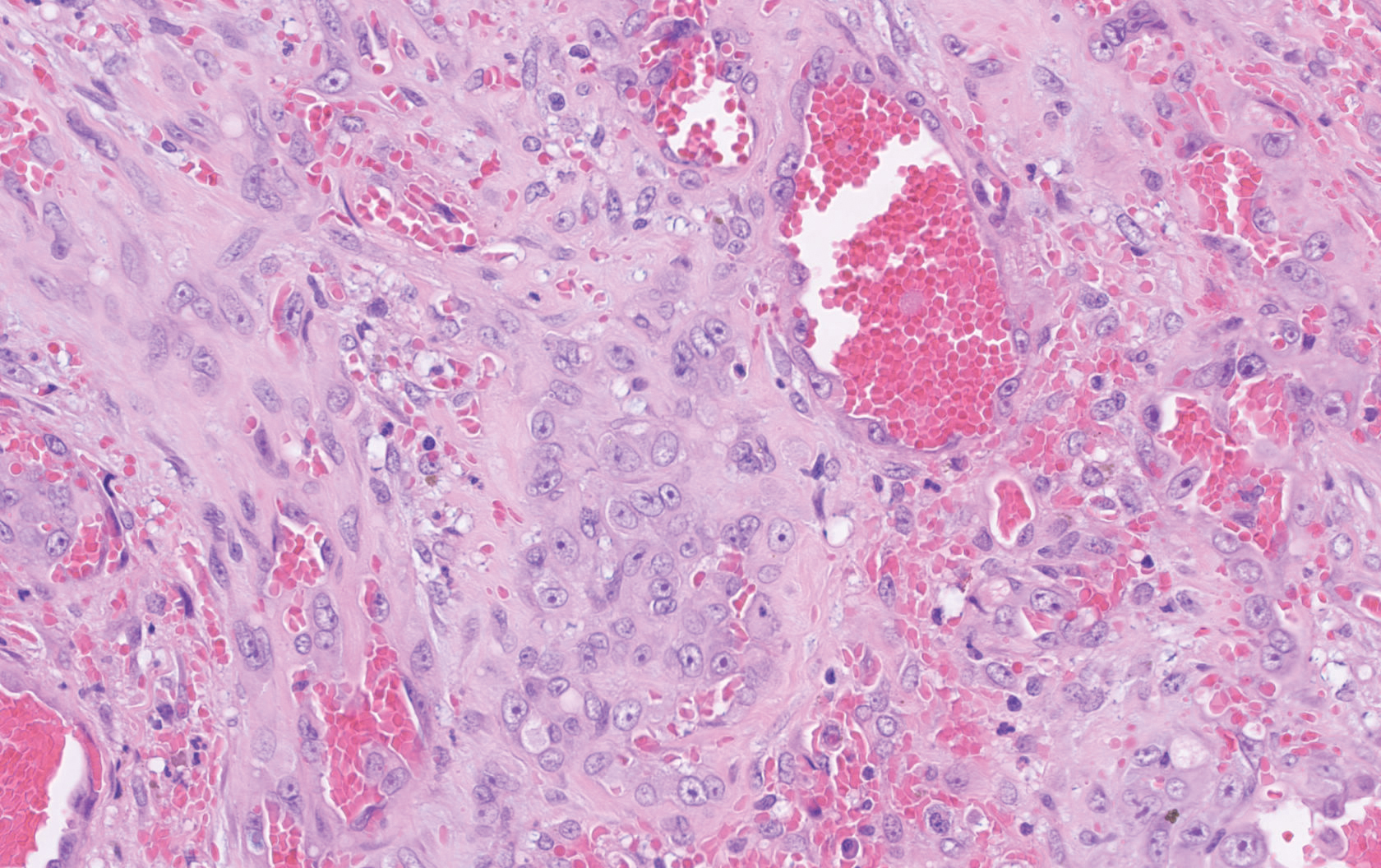

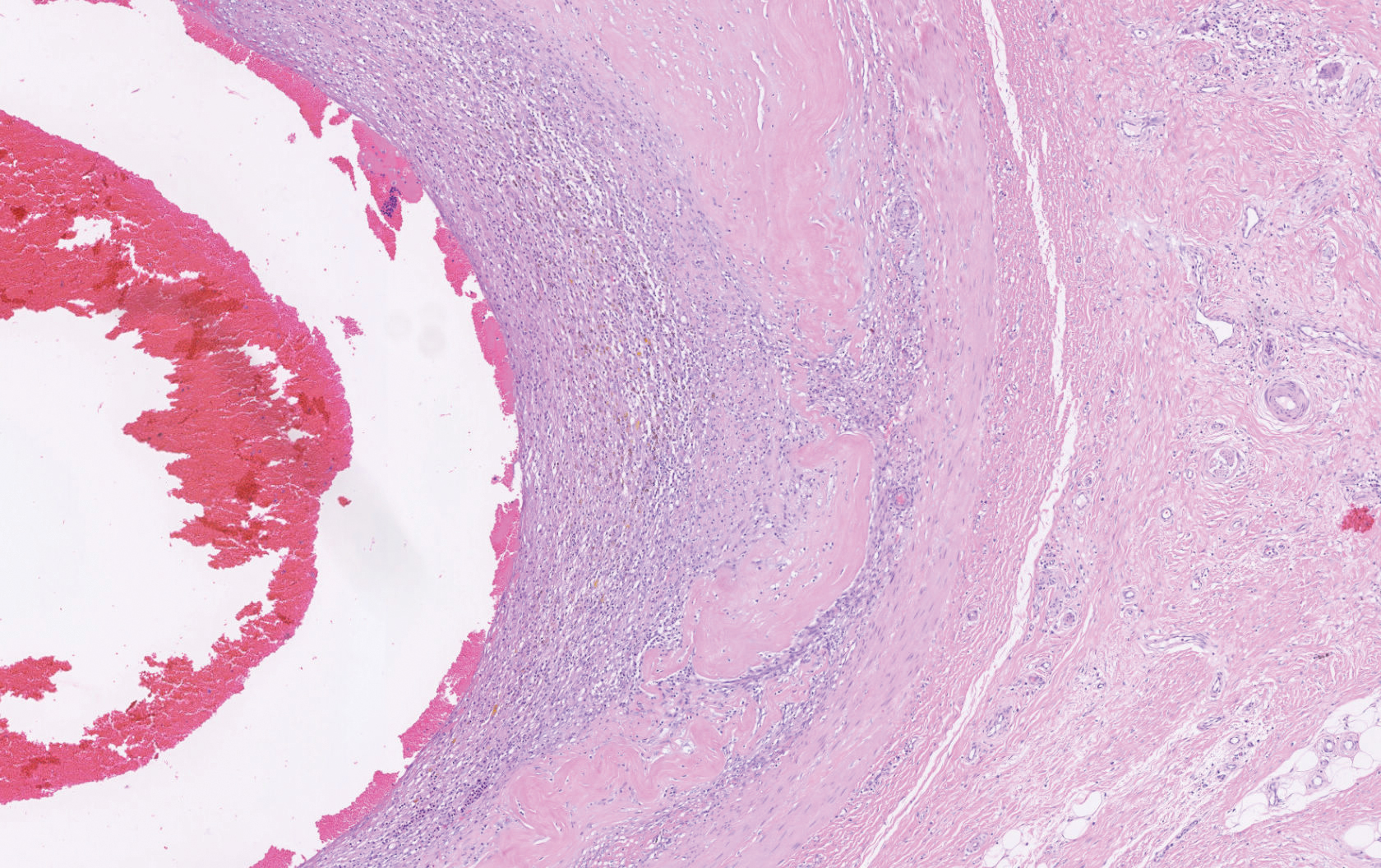

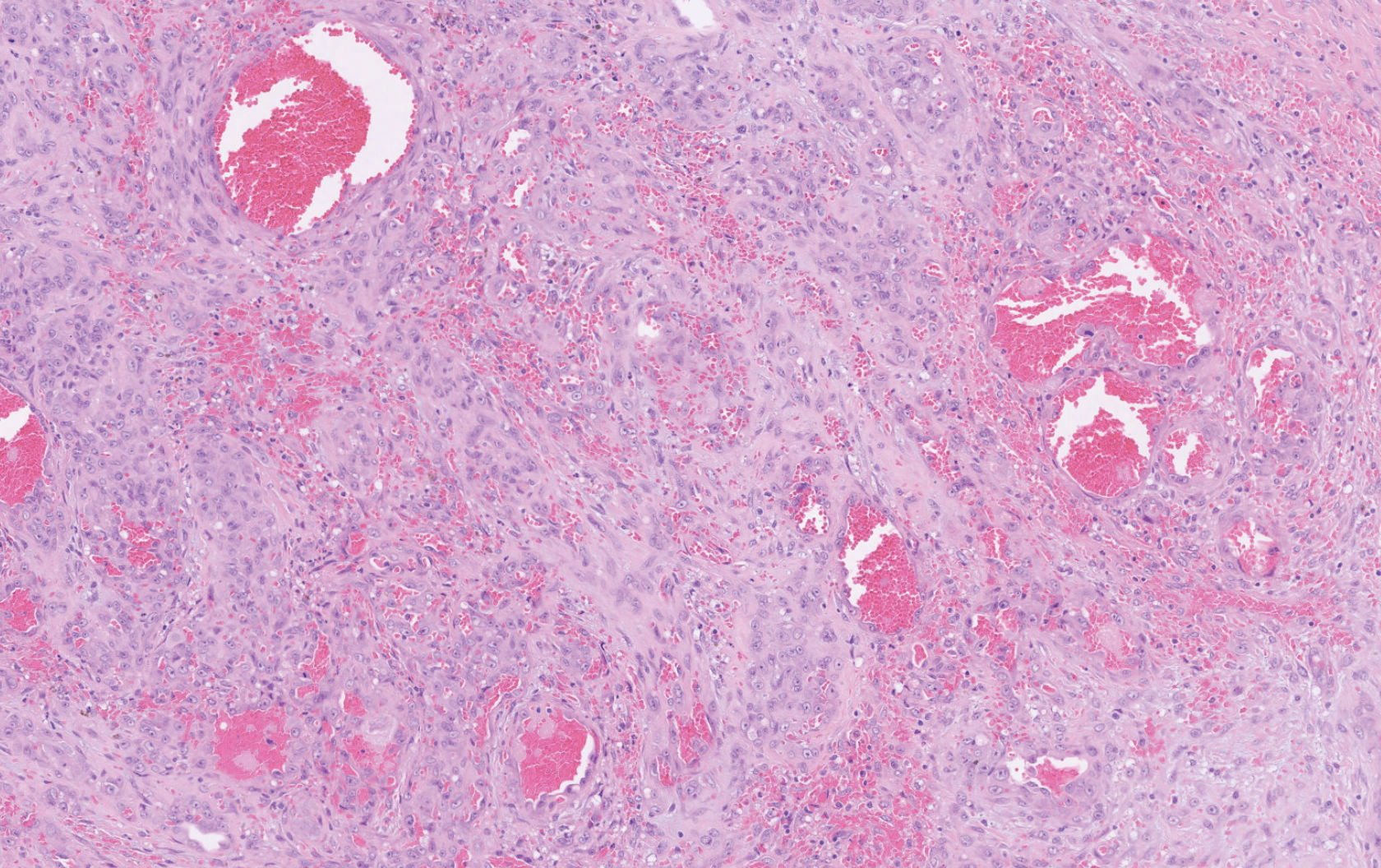

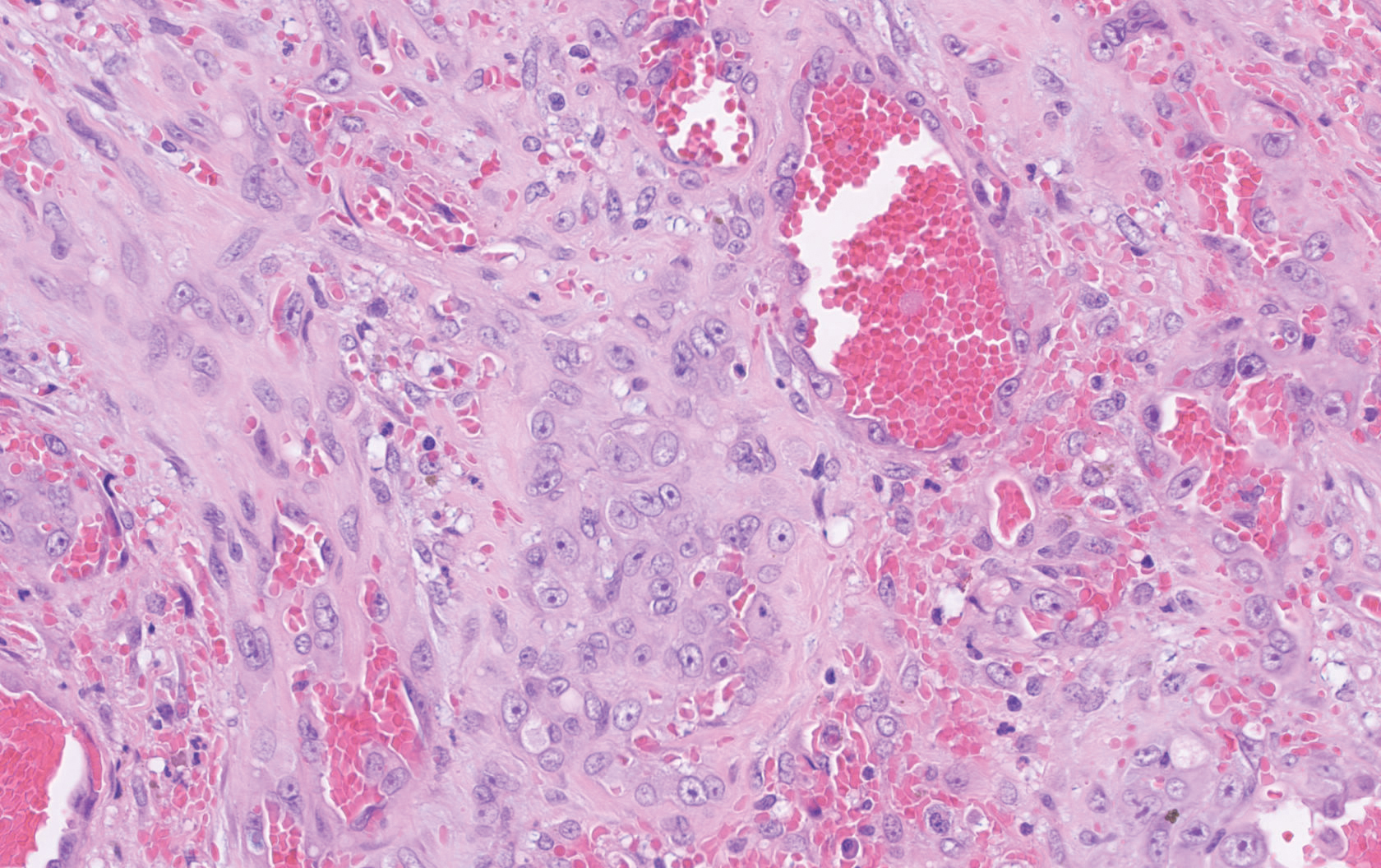

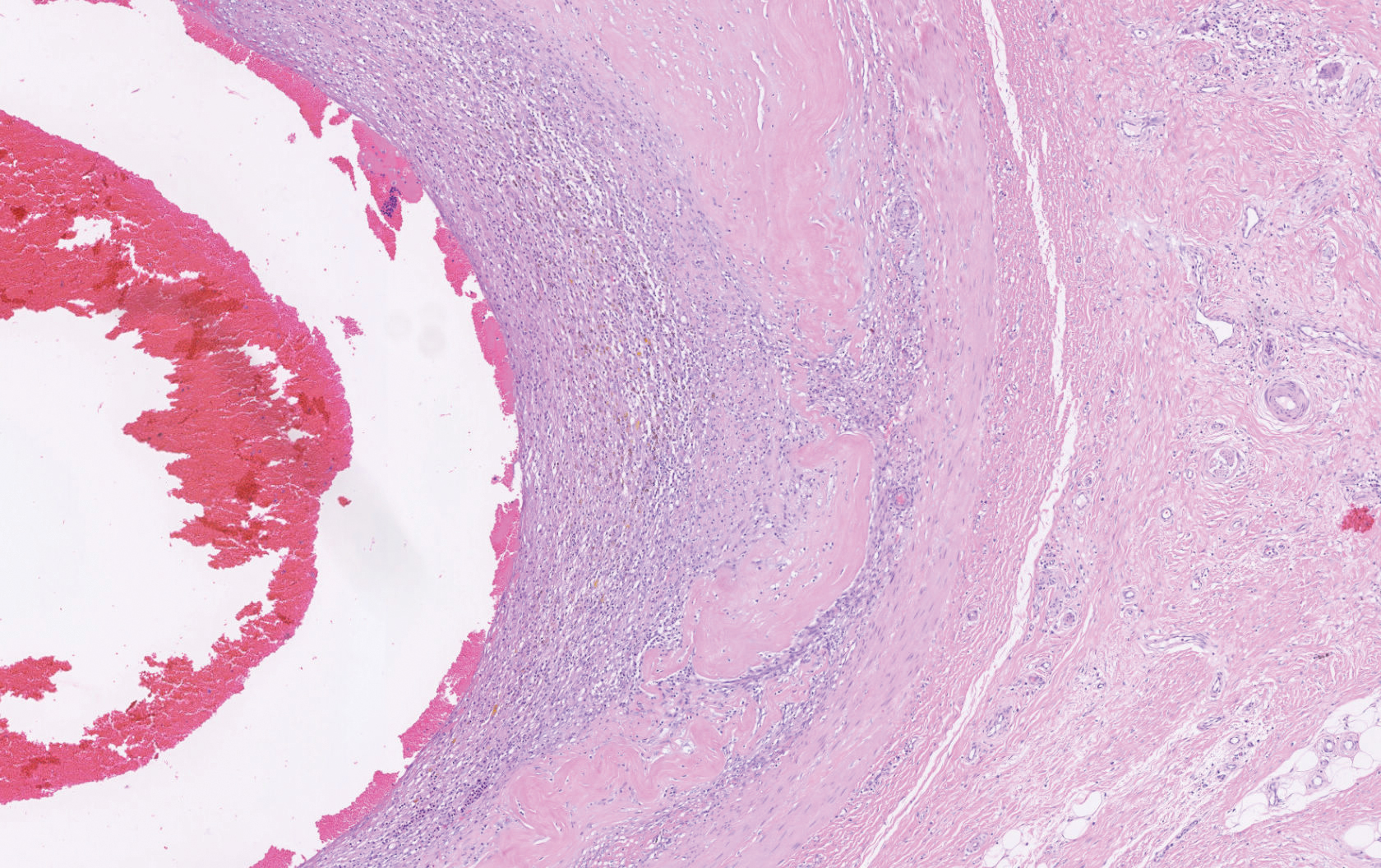

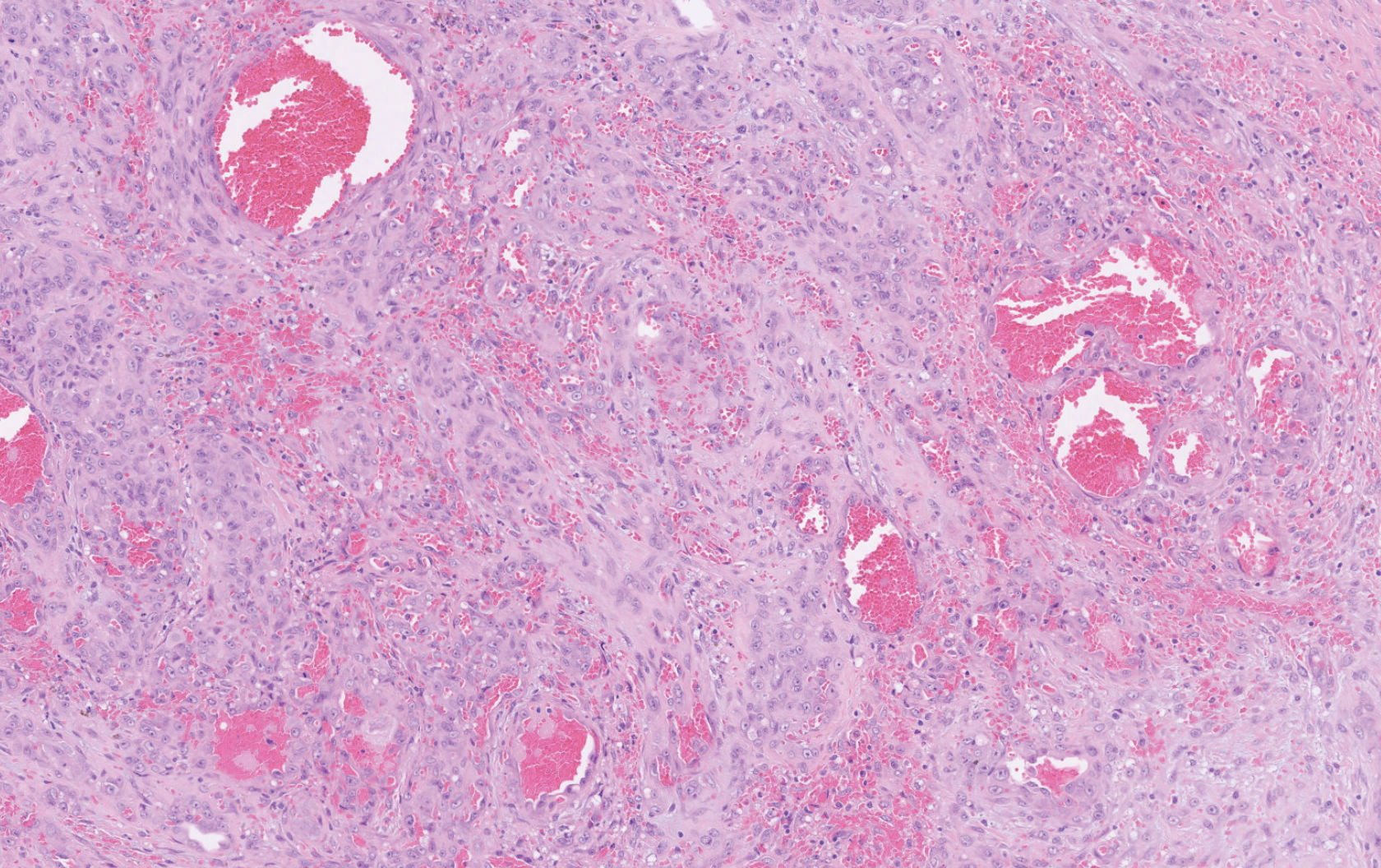

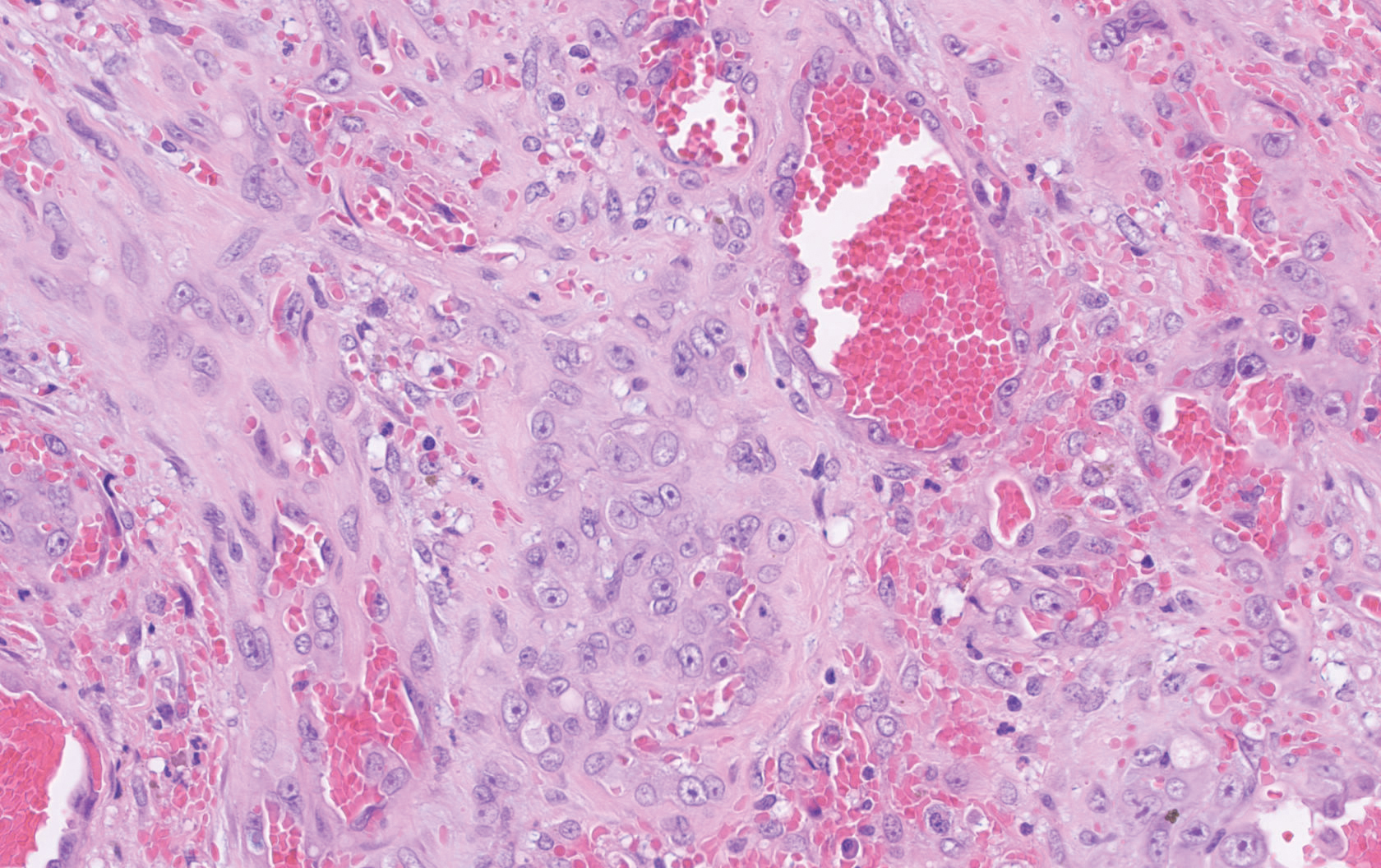

Histopathology showed a large soft-tissue neoplasm with extensive hemorrhage (Figure 1). The epithelioid angiosarcoma (EA) consisted mostly of irregular slit-shaped vessels lined by sheets of atypical endothelial cells (Figure 2). At higher-power magnification, the cellular atypia was prominent and diffuse (Figure 3). Immunostaining of the tumor cells showed positive uptake for CD31, confirming vascular origin (Figure 4). Other vascular markers, including CD34 and factor VIII, as well as nuclear positivity for the erythroblast transformation-specific transcription factor gene, ERG, can be demonstrated by EA. Irregular, smooth muscle actin-positive spindle cells are distributed around some of the vessels. The human herpesvirus 8 stain is negative.

Compared to classic angiosarcomas, EAs have a predilection for the extremities rather than the head and scalp. Histopathologically, the cells are epithelioid and are strongly positive for vimentin and CD31, in addition to factor VIII, friend leukemia integration 1 transcription factor, and CD34.1,2 In contrast, epithelioid sarcomas more typically are seen in younger adults and less likely to be CD31 positive.3 An epithelioid hemangioendothelioma is more focal in cellular atypia and forms small nests and trabeculae rather than sheets of atypical cells. Melanoma cells stain positive for human melanoma black 45, Melan-A, and S-100 but not for CD31.3 Glomangiosarcomas typically stain positive for smooth muscle actin and muscle-specific actin.4

Epithelioid angiosarcomas are rare and aggressive malignancies of endothelial origin.3 They are more prevalent in men and have a peak incidence in the seventh decade of life. They most commonly occur in the deep soft tissues of the extremities but have been reported to form in a variety of primary sites, including the skin, bones, thyroid, and adrenal glands.3

Tumors tend to be highly aggressive and demonstrate early nodal and solid organ metastases.3 Our case demonstrated the aggressive nature of this high-grade malignancy by showing neoplastic invasion through a vascular wall. Within 2 to 3 years of diagnosis, 50% of patients die of the disease, and the 5-year survival rate is estimated to be 12% to 20%.3,5 The etiology remains unknown, but EA has been linked to prior exposure to toxic chemicals, irradiation, or Thorotrast contrast media, and it may arise in the setting of arteriovenous fistulae and chronic lymphedema.6

Although radiation therapy often is utilized, surgery is the primary treatment modality.5 Even with wide excision, local recurrence is common. Tumor size is one of the most important prognostic features, with a worse prognosis for tumors larger than 5 cm. Evidence suggests that paclitaxel-based chemotherapeutic regimens may improve survival, and a combination of paclitaxel and sorafenib has been reported to induce remission in metastatic angiosarcoma of parietal EA.5 Currently, no standardized treatment regimen for this condition exists.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Amanda Marsch, MD (Chicago, Illinois), for obtaining outside pathology consultation.

- Suchak R, Thway K, Zelger B, et al. Primary cutaneous epithelioid angiosarcoma: a clinicopathologic study of 13 cases of a rare neoplasm occurring outside the setting of conventional angiosarcomas and with predilection for the limbs. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:60-69.

- Prescott RJ, Banerjee SS, Eyden BP, et al. Cutaneous epithelioid angiosarcoma: a clinicopathological study of four cases. Histopathology. 1994;25:421-429.

- Hart J, Mandavilli S. Epithelioid angiosarcoma: a brief diagnostic review and differential diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:268-272.

- Maselli AM, Jambhekar AV, Hunter JG. Glomangiosarcoma arising from a prior biopsy site. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2017;5:e1219.

- Donghi D, Dummer R, Cozzio A. Complete remission in a patient with multifocal metastatic cutaneous angiosarcoma with a combination of paclitaxel and sorafenib. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:697-699.

- Wu J, Li X, Liu X. Epithelioid angiosarcoma: a clinicopathological study of 16 Chinese cases. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:3901-3909.

The Diagnosis: Epithelioid Angiosarcoma

Histopathology showed a large soft-tissue neoplasm with extensive hemorrhage (Figure 1). The epithelioid angiosarcoma (EA) consisted mostly of irregular slit-shaped vessels lined by sheets of atypical endothelial cells (Figure 2). At higher-power magnification, the cellular atypia was prominent and diffuse (Figure 3). Immunostaining of the tumor cells showed positive uptake for CD31, confirming vascular origin (Figure 4). Other vascular markers, including CD34 and factor VIII, as well as nuclear positivity for the erythroblast transformation-specific transcription factor gene, ERG, can be demonstrated by EA. Irregular, smooth muscle actin-positive spindle cells are distributed around some of the vessels. The human herpesvirus 8 stain is negative.

Compared to classic angiosarcomas, EAs have a predilection for the extremities rather than the head and scalp. Histopathologically, the cells are epithelioid and are strongly positive for vimentin and CD31, in addition to factor VIII, friend leukemia integration 1 transcription factor, and CD34.1,2 In contrast, epithelioid sarcomas more typically are seen in younger adults and less likely to be CD31 positive.3 An epithelioid hemangioendothelioma is more focal in cellular atypia and forms small nests and trabeculae rather than sheets of atypical cells. Melanoma cells stain positive for human melanoma black 45, Melan-A, and S-100 but not for CD31.3 Glomangiosarcomas typically stain positive for smooth muscle actin and muscle-specific actin.4

Epithelioid angiosarcomas are rare and aggressive malignancies of endothelial origin.3 They are more prevalent in men and have a peak incidence in the seventh decade of life. They most commonly occur in the deep soft tissues of the extremities but have been reported to form in a variety of primary sites, including the skin, bones, thyroid, and adrenal glands.3

Tumors tend to be highly aggressive and demonstrate early nodal and solid organ metastases.3 Our case demonstrated the aggressive nature of this high-grade malignancy by showing neoplastic invasion through a vascular wall. Within 2 to 3 years of diagnosis, 50% of patients die of the disease, and the 5-year survival rate is estimated to be 12% to 20%.3,5 The etiology remains unknown, but EA has been linked to prior exposure to toxic chemicals, irradiation, or Thorotrast contrast media, and it may arise in the setting of arteriovenous fistulae and chronic lymphedema.6

Although radiation therapy often is utilized, surgery is the primary treatment modality.5 Even with wide excision, local recurrence is common. Tumor size is one of the most important prognostic features, with a worse prognosis for tumors larger than 5 cm. Evidence suggests that paclitaxel-based chemotherapeutic regimens may improve survival, and a combination of paclitaxel and sorafenib has been reported to induce remission in metastatic angiosarcoma of parietal EA.5 Currently, no standardized treatment regimen for this condition exists.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Amanda Marsch, MD (Chicago, Illinois), for obtaining outside pathology consultation.

The Diagnosis: Epithelioid Angiosarcoma

Histopathology showed a large soft-tissue neoplasm with extensive hemorrhage (Figure 1). The epithelioid angiosarcoma (EA) consisted mostly of irregular slit-shaped vessels lined by sheets of atypical endothelial cells (Figure 2). At higher-power magnification, the cellular atypia was prominent and diffuse (Figure 3). Immunostaining of the tumor cells showed positive uptake for CD31, confirming vascular origin (Figure 4). Other vascular markers, including CD34 and factor VIII, as well as nuclear positivity for the erythroblast transformation-specific transcription factor gene, ERG, can be demonstrated by EA. Irregular, smooth muscle actin-positive spindle cells are distributed around some of the vessels. The human herpesvirus 8 stain is negative.

Compared to classic angiosarcomas, EAs have a predilection for the extremities rather than the head and scalp. Histopathologically, the cells are epithelioid and are strongly positive for vimentin and CD31, in addition to factor VIII, friend leukemia integration 1 transcription factor, and CD34.1,2 In contrast, epithelioid sarcomas more typically are seen in younger adults and less likely to be CD31 positive.3 An epithelioid hemangioendothelioma is more focal in cellular atypia and forms small nests and trabeculae rather than sheets of atypical cells. Melanoma cells stain positive for human melanoma black 45, Melan-A, and S-100 but not for CD31.3 Glomangiosarcomas typically stain positive for smooth muscle actin and muscle-specific actin.4

Epithelioid angiosarcomas are rare and aggressive malignancies of endothelial origin.3 They are more prevalent in men and have a peak incidence in the seventh decade of life. They most commonly occur in the deep soft tissues of the extremities but have been reported to form in a variety of primary sites, including the skin, bones, thyroid, and adrenal glands.3

Tumors tend to be highly aggressive and demonstrate early nodal and solid organ metastases.3 Our case demonstrated the aggressive nature of this high-grade malignancy by showing neoplastic invasion through a vascular wall. Within 2 to 3 years of diagnosis, 50% of patients die of the disease, and the 5-year survival rate is estimated to be 12% to 20%.3,5 The etiology remains unknown, but EA has been linked to prior exposure to toxic chemicals, irradiation, or Thorotrast contrast media, and it may arise in the setting of arteriovenous fistulae and chronic lymphedema.6

Although radiation therapy often is utilized, surgery is the primary treatment modality.5 Even with wide excision, local recurrence is common. Tumor size is one of the most important prognostic features, with a worse prognosis for tumors larger than 5 cm. Evidence suggests that paclitaxel-based chemotherapeutic regimens may improve survival, and a combination of paclitaxel and sorafenib has been reported to induce remission in metastatic angiosarcoma of parietal EA.5 Currently, no standardized treatment regimen for this condition exists.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Amanda Marsch, MD (Chicago, Illinois), for obtaining outside pathology consultation.

- Suchak R, Thway K, Zelger B, et al. Primary cutaneous epithelioid angiosarcoma: a clinicopathologic study of 13 cases of a rare neoplasm occurring outside the setting of conventional angiosarcomas and with predilection for the limbs. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:60-69.

- Prescott RJ, Banerjee SS, Eyden BP, et al. Cutaneous epithelioid angiosarcoma: a clinicopathological study of four cases. Histopathology. 1994;25:421-429.

- Hart J, Mandavilli S. Epithelioid angiosarcoma: a brief diagnostic review and differential diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:268-272.

- Maselli AM, Jambhekar AV, Hunter JG. Glomangiosarcoma arising from a prior biopsy site. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2017;5:e1219.

- Donghi D, Dummer R, Cozzio A. Complete remission in a patient with multifocal metastatic cutaneous angiosarcoma with a combination of paclitaxel and sorafenib. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:697-699.

- Wu J, Li X, Liu X. Epithelioid angiosarcoma: a clinicopathological study of 16 Chinese cases. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:3901-3909.

- Suchak R, Thway K, Zelger B, et al. Primary cutaneous epithelioid angiosarcoma: a clinicopathologic study of 13 cases of a rare neoplasm occurring outside the setting of conventional angiosarcomas and with predilection for the limbs. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:60-69.

- Prescott RJ, Banerjee SS, Eyden BP, et al. Cutaneous epithelioid angiosarcoma: a clinicopathological study of four cases. Histopathology. 1994;25:421-429.

- Hart J, Mandavilli S. Epithelioid angiosarcoma: a brief diagnostic review and differential diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:268-272.

- Maselli AM, Jambhekar AV, Hunter JG. Glomangiosarcoma arising from a prior biopsy site. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2017;5:e1219.

- Donghi D, Dummer R, Cozzio A. Complete remission in a patient with multifocal metastatic cutaneous angiosarcoma with a combination of paclitaxel and sorafenib. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:697-699.

- Wu J, Li X, Liu X. Epithelioid angiosarcoma: a clinicopathological study of 16 Chinese cases. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:3901-3909.

A 72-year-old man presented for evaluation of a mass on the left hand that continued to grow over the last few months and eventually bled. The patient first noticed a small firm lump on the palm approximately 1 year prior to presentation, and it was originally diagnosed as a Dupuytren contracture by his primary care physician. Months later, the lesion grew and began to bleed. Magnetic resonance imaging showed large hematomas of the hand with areas of nodular enhancement. The mass was located between the third and fourth proximal phalanges and abutted the extensor tendon. Complete excision yielded a definitive diagnosis.

Reticular Hyperpigmented Patches With Indurated Subcutaneous Plaques

The Diagnosis: Superficial Migratory Thrombophlebitis

On initial presentation, the differential diagnosis included livedoid vasculopathy, cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa, erythema ab igne, cholesterol embolism, and livedo reticularis. Laboratory investigation included antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS), antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, serum protein electrophoresis, and coagulation tests. Pertinent findings included transient low total complement activity but normal complement protein C2, C3, and C5 levels and negative cryoglobulins. Additional laboratory testing revealed elevated antiphosphatidylserine IgG, which remained elevated 12 weeks later.

New lesions continued to appear over the next several months as painful, erythematous, linear, pruritic nodules that resolved as hyperpigmented linear patches, which intersected to form a livedo reticularis-like pattern that covered the lower legs. Biopsy of an erythematous nodule on the right leg revealed fibrin occlusion of a medium-sized vein in the subcutaneous fat. Direct immunofluorescence was not specific. Venous duplex ultrasonography demonstrated chronic superficial thrombophlebitis and was crucial to the diagnosis. Ultimately, the patient's history, clinical presentation, laboratory results, venous studies, and histopathologic analysis were consistent with a diagnosis of superficial migratory thrombophlebitis (SMT) with resultant postinflammatory hyperpigmentation presenting in a reticular pattern that mimicked livedoid vasculopathy, livedo reticularis, or erythema ab igne.

Superficial migratory thrombophlebitis, also known as thrombophlebitis migrans, is defined as the recurrent formation of thrombi within superficial veins.1 The presence of a thrombus in a superficial vein evokes an inflammatory response, resulting in swelling, tenderness, erythema, and warmth in the affected area. Superficial migratory thrombophlebitis has been associated with several etiologies, including pregnancy, oral contraceptive use, APS, vasculitic disorders, and malignancies (eg, pancreas, lung, breast), as well as infections such as secondary syphilis.1

When SMT is associated with an occult malignancy, it is known as Trousseau syndrome. Common malignancies found in association with Trousseau syndrome include pancreatic, lung, and breast cancers.2 A systematic review from 2008 evaluated the utility of extensive cancer screening strategies in patients with newly diagnosed, unprovoked venous thromboembolic events.3 Using a wide screening strategy that included computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis, the investigators detected a considerable number of formerly undiagnosed cancers, increasing detection rates from 49.4% to 69.7%. After the diagnosis of SMT was made in our patient, computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was performed, but the findings were unremarkable.

Because occult malignancy was excluded in our patient, the likely etiology of SMT was APS, an acquired autoimmune condition diagnosed based on the presence of a vascular thrombosis and/or pregnancy failure in women as well as elevation of at least one antiphospholipid antibody laboratory marker (eg, lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibody, and anti-β2 glycoprotein I antibody) on 2 or more occasions at least 12 weeks apart.4 Other antibodies such as those directed against negatively charged phospholipids (eg, antiphosphatidylserine [which was elevated in our patient], phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidic acid) have been reported in patients with APS, although their diagnostic use is controversial.5 For example, the presence of antiphosphatidylserine antibodies has been considered common but not specific in patients with APS.4 However, a recent observational study demonstrated that antiphosphatidylserine antibodies are highly specific (87%) and useful in diagnosing clinical APS cases in the presence of other negative markers.6

In our patient, diagnosis of SMT with resultant postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in a reticular pattern was based on the patient's medical history, clinical examination, and histopathologic findings, as well as laboratory results and venous studies. However, it is important to note that a livedo reticularis-like pattern also is a very common finding in APS and must be included in the differential diagnosis of a reticular network on the skin.7 Moreover, differentiating livedo reticularis from SMT has prognostic importance since SMT may be associated with underlying malignancies while livedo reticularis may be associated with Sneddon syndrome, a disorder in which neurologic vascular events (eg, cerebrovascular accidents) are present.8 While this distinction is important, there are no pathognomonic histologic findings seen in livedo reticularis, and consideration of the clinical picture and additional testing is critical.4,8

Livedo vasculopathy was excluded in our patient due to the lack of diagnostic histopathologic findings, such as fibrin deposition and thrombus formation involving the upper- and mid-dermal capillaries.9 Furthermore, characteristic direct immunofluorescence findings of a homogenous or granular deposition in the vessel wall consisting of immune complexes, complement, and fibrin were absent in our patient.9 Our patient also lacked common clinical findings found in livedo vasculopathy such as small ulcerations or atrophic, porcelain-white scars on the lower legs. Erythema ab igne also was excluded in our patient due to the absence of heat exposure and presence of fibrin occlusion in the superficial leg veins. Physiologic livedo reticularis, defined as a livedoid pattern due to physiologic changes in the skin in response to cold exposure,10 also was excluded, as our patient's cutaneous changes included an alteration in pigmentation with a brown reticular pattern and no blanching, erythematous or violaceous hue, warmth, or tenderness.

In conclusion, SMT is a disorder with multiple associations that may clinically mimic livedo reticularis and livedoid vasculopathy when postinflammatory hyperpigmentation has a lacelike or livedoid pattern. While nontraditional antibodies may be useful in diagnosis in patients suspected of having APS with otherwise negative markers, standardized assays and further studies are needed to determine the specificity and value of these antibodies, particularly when used in isolation. Our patient's elevated antiphosphatidylserine IgG may have been the cause of her hypercoagulable state causing the SMT. A livedoid pattern is a common finding in APS and also was seen in our patient with SMT, but the differentiation of the brown pigmentary change and more active erythema was critical to the appropriate clinical workup of our patient.

- Samlaska CP, James WD. Superficial thrombophlebitis. II. secondary hypercoagulable states. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23:1-18.

- Rigdon EE. Trousseau's syndrome and acute arterial thrombosis. Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;8:214-218.

- Carrier M, Le Gal G, Wells PS, et al. Systematic review: the Trousseau syndrome revisited: should we screen extensively for cancer in patients with venous thromboembolism? Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:323-333.

- Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, et al. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:295-306.

- Bertolaccini ML, Amengual O, Atsumi T, et al. 'Non-criteria' aPL tests: report of a task force and preconference workshop at the 13th International Congress on Antiphospholipid Antibodies, Galveston, TX, USA, April 2010. Lupus. 2011;20:191-205.

- Khogeer H, Alfattani A, Al Kaff M, et al. Antiphosphatidylserine antibodies as diagnostic indicators of antiphospholipid syndrome. Lupus. 2015;24:186-190.

- Gibson GE, Su WP, Pittelkow MR. Antiphospholipid syndrome and the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36(6 pt 1):970-982.

- Francès C, Papo T, Wechsler B, et al. Sneddon syndrome with or without antiphospholipid antibodies. a comparative study in 46 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1999;78:209-219.

- Vasudevan B, Neema S, Verma R. Livedoid vasculopathy: a review of pathogenesis and principles of management. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:478-488.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews' Diseases Of The Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2006.

The Diagnosis: Superficial Migratory Thrombophlebitis

On initial presentation, the differential diagnosis included livedoid vasculopathy, cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa, erythema ab igne, cholesterol embolism, and livedo reticularis. Laboratory investigation included antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS), antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, serum protein electrophoresis, and coagulation tests. Pertinent findings included transient low total complement activity but normal complement protein C2, C3, and C5 levels and negative cryoglobulins. Additional laboratory testing revealed elevated antiphosphatidylserine IgG, which remained elevated 12 weeks later.

New lesions continued to appear over the next several months as painful, erythematous, linear, pruritic nodules that resolved as hyperpigmented linear patches, which intersected to form a livedo reticularis-like pattern that covered the lower legs. Biopsy of an erythematous nodule on the right leg revealed fibrin occlusion of a medium-sized vein in the subcutaneous fat. Direct immunofluorescence was not specific. Venous duplex ultrasonography demonstrated chronic superficial thrombophlebitis and was crucial to the diagnosis. Ultimately, the patient's history, clinical presentation, laboratory results, venous studies, and histopathologic analysis were consistent with a diagnosis of superficial migratory thrombophlebitis (SMT) with resultant postinflammatory hyperpigmentation presenting in a reticular pattern that mimicked livedoid vasculopathy, livedo reticularis, or erythema ab igne.

Superficial migratory thrombophlebitis, also known as thrombophlebitis migrans, is defined as the recurrent formation of thrombi within superficial veins.1 The presence of a thrombus in a superficial vein evokes an inflammatory response, resulting in swelling, tenderness, erythema, and warmth in the affected area. Superficial migratory thrombophlebitis has been associated with several etiologies, including pregnancy, oral contraceptive use, APS, vasculitic disorders, and malignancies (eg, pancreas, lung, breast), as well as infections such as secondary syphilis.1

When SMT is associated with an occult malignancy, it is known as Trousseau syndrome. Common malignancies found in association with Trousseau syndrome include pancreatic, lung, and breast cancers.2 A systematic review from 2008 evaluated the utility of extensive cancer screening strategies in patients with newly diagnosed, unprovoked venous thromboembolic events.3 Using a wide screening strategy that included computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis, the investigators detected a considerable number of formerly undiagnosed cancers, increasing detection rates from 49.4% to 69.7%. After the diagnosis of SMT was made in our patient, computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was performed, but the findings were unremarkable.

Because occult malignancy was excluded in our patient, the likely etiology of SMT was APS, an acquired autoimmune condition diagnosed based on the presence of a vascular thrombosis and/or pregnancy failure in women as well as elevation of at least one antiphospholipid antibody laboratory marker (eg, lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibody, and anti-β2 glycoprotein I antibody) on 2 or more occasions at least 12 weeks apart.4 Other antibodies such as those directed against negatively charged phospholipids (eg, antiphosphatidylserine [which was elevated in our patient], phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidic acid) have been reported in patients with APS, although their diagnostic use is controversial.5 For example, the presence of antiphosphatidylserine antibodies has been considered common but not specific in patients with APS.4 However, a recent observational study demonstrated that antiphosphatidylserine antibodies are highly specific (87%) and useful in diagnosing clinical APS cases in the presence of other negative markers.6

In our patient, diagnosis of SMT with resultant postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in a reticular pattern was based on the patient's medical history, clinical examination, and histopathologic findings, as well as laboratory results and venous studies. However, it is important to note that a livedo reticularis-like pattern also is a very common finding in APS and must be included in the differential diagnosis of a reticular network on the skin.7 Moreover, differentiating livedo reticularis from SMT has prognostic importance since SMT may be associated with underlying malignancies while livedo reticularis may be associated with Sneddon syndrome, a disorder in which neurologic vascular events (eg, cerebrovascular accidents) are present.8 While this distinction is important, there are no pathognomonic histologic findings seen in livedo reticularis, and consideration of the clinical picture and additional testing is critical.4,8

Livedo vasculopathy was excluded in our patient due to the lack of diagnostic histopathologic findings, such as fibrin deposition and thrombus formation involving the upper- and mid-dermal capillaries.9 Furthermore, characteristic direct immunofluorescence findings of a homogenous or granular deposition in the vessel wall consisting of immune complexes, complement, and fibrin were absent in our patient.9 Our patient also lacked common clinical findings found in livedo vasculopathy such as small ulcerations or atrophic, porcelain-white scars on the lower legs. Erythema ab igne also was excluded in our patient due to the absence of heat exposure and presence of fibrin occlusion in the superficial leg veins. Physiologic livedo reticularis, defined as a livedoid pattern due to physiologic changes in the skin in response to cold exposure,10 also was excluded, as our patient's cutaneous changes included an alteration in pigmentation with a brown reticular pattern and no blanching, erythematous or violaceous hue, warmth, or tenderness.

In conclusion, SMT is a disorder with multiple associations that may clinically mimic livedo reticularis and livedoid vasculopathy when postinflammatory hyperpigmentation has a lacelike or livedoid pattern. While nontraditional antibodies may be useful in diagnosis in patients suspected of having APS with otherwise negative markers, standardized assays and further studies are needed to determine the specificity and value of these antibodies, particularly when used in isolation. Our patient's elevated antiphosphatidylserine IgG may have been the cause of her hypercoagulable state causing the SMT. A livedoid pattern is a common finding in APS and also was seen in our patient with SMT, but the differentiation of the brown pigmentary change and more active erythema was critical to the appropriate clinical workup of our patient.

The Diagnosis: Superficial Migratory Thrombophlebitis

On initial presentation, the differential diagnosis included livedoid vasculopathy, cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa, erythema ab igne, cholesterol embolism, and livedo reticularis. Laboratory investigation included antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS), antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, serum protein electrophoresis, and coagulation tests. Pertinent findings included transient low total complement activity but normal complement protein C2, C3, and C5 levels and negative cryoglobulins. Additional laboratory testing revealed elevated antiphosphatidylserine IgG, which remained elevated 12 weeks later.

New lesions continued to appear over the next several months as painful, erythematous, linear, pruritic nodules that resolved as hyperpigmented linear patches, which intersected to form a livedo reticularis-like pattern that covered the lower legs. Biopsy of an erythematous nodule on the right leg revealed fibrin occlusion of a medium-sized vein in the subcutaneous fat. Direct immunofluorescence was not specific. Venous duplex ultrasonography demonstrated chronic superficial thrombophlebitis and was crucial to the diagnosis. Ultimately, the patient's history, clinical presentation, laboratory results, venous studies, and histopathologic analysis were consistent with a diagnosis of superficial migratory thrombophlebitis (SMT) with resultant postinflammatory hyperpigmentation presenting in a reticular pattern that mimicked livedoid vasculopathy, livedo reticularis, or erythema ab igne.

Superficial migratory thrombophlebitis, also known as thrombophlebitis migrans, is defined as the recurrent formation of thrombi within superficial veins.1 The presence of a thrombus in a superficial vein evokes an inflammatory response, resulting in swelling, tenderness, erythema, and warmth in the affected area. Superficial migratory thrombophlebitis has been associated with several etiologies, including pregnancy, oral contraceptive use, APS, vasculitic disorders, and malignancies (eg, pancreas, lung, breast), as well as infections such as secondary syphilis.1

When SMT is associated with an occult malignancy, it is known as Trousseau syndrome. Common malignancies found in association with Trousseau syndrome include pancreatic, lung, and breast cancers.2 A systematic review from 2008 evaluated the utility of extensive cancer screening strategies in patients with newly diagnosed, unprovoked venous thromboembolic events.3 Using a wide screening strategy that included computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis, the investigators detected a considerable number of formerly undiagnosed cancers, increasing detection rates from 49.4% to 69.7%. After the diagnosis of SMT was made in our patient, computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was performed, but the findings were unremarkable.

Because occult malignancy was excluded in our patient, the likely etiology of SMT was APS, an acquired autoimmune condition diagnosed based on the presence of a vascular thrombosis and/or pregnancy failure in women as well as elevation of at least one antiphospholipid antibody laboratory marker (eg, lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibody, and anti-β2 glycoprotein I antibody) on 2 or more occasions at least 12 weeks apart.4 Other antibodies such as those directed against negatively charged phospholipids (eg, antiphosphatidylserine [which was elevated in our patient], phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidic acid) have been reported in patients with APS, although their diagnostic use is controversial.5 For example, the presence of antiphosphatidylserine antibodies has been considered common but not specific in patients with APS.4 However, a recent observational study demonstrated that antiphosphatidylserine antibodies are highly specific (87%) and useful in diagnosing clinical APS cases in the presence of other negative markers.6

In our patient, diagnosis of SMT with resultant postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in a reticular pattern was based on the patient's medical history, clinical examination, and histopathologic findings, as well as laboratory results and venous studies. However, it is important to note that a livedo reticularis-like pattern also is a very common finding in APS and must be included in the differential diagnosis of a reticular network on the skin.7 Moreover, differentiating livedo reticularis from SMT has prognostic importance since SMT may be associated with underlying malignancies while livedo reticularis may be associated with Sneddon syndrome, a disorder in which neurologic vascular events (eg, cerebrovascular accidents) are present.8 While this distinction is important, there are no pathognomonic histologic findings seen in livedo reticularis, and consideration of the clinical picture and additional testing is critical.4,8

Livedo vasculopathy was excluded in our patient due to the lack of diagnostic histopathologic findings, such as fibrin deposition and thrombus formation involving the upper- and mid-dermal capillaries.9 Furthermore, characteristic direct immunofluorescence findings of a homogenous or granular deposition in the vessel wall consisting of immune complexes, complement, and fibrin were absent in our patient.9 Our patient also lacked common clinical findings found in livedo vasculopathy such as small ulcerations or atrophic, porcelain-white scars on the lower legs. Erythema ab igne also was excluded in our patient due to the absence of heat exposure and presence of fibrin occlusion in the superficial leg veins. Physiologic livedo reticularis, defined as a livedoid pattern due to physiologic changes in the skin in response to cold exposure,10 also was excluded, as our patient's cutaneous changes included an alteration in pigmentation with a brown reticular pattern and no blanching, erythematous or violaceous hue, warmth, or tenderness.

In conclusion, SMT is a disorder with multiple associations that may clinically mimic livedo reticularis and livedoid vasculopathy when postinflammatory hyperpigmentation has a lacelike or livedoid pattern. While nontraditional antibodies may be useful in diagnosis in patients suspected of having APS with otherwise negative markers, standardized assays and further studies are needed to determine the specificity and value of these antibodies, particularly when used in isolation. Our patient's elevated antiphosphatidylserine IgG may have been the cause of her hypercoagulable state causing the SMT. A livedoid pattern is a common finding in APS and also was seen in our patient with SMT, but the differentiation of the brown pigmentary change and more active erythema was critical to the appropriate clinical workup of our patient.

- Samlaska CP, James WD. Superficial thrombophlebitis. II. secondary hypercoagulable states. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23:1-18.

- Rigdon EE. Trousseau's syndrome and acute arterial thrombosis. Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;8:214-218.

- Carrier M, Le Gal G, Wells PS, et al. Systematic review: the Trousseau syndrome revisited: should we screen extensively for cancer in patients with venous thromboembolism? Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:323-333.

- Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, et al. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:295-306.

- Bertolaccini ML, Amengual O, Atsumi T, et al. 'Non-criteria' aPL tests: report of a task force and preconference workshop at the 13th International Congress on Antiphospholipid Antibodies, Galveston, TX, USA, April 2010. Lupus. 2011;20:191-205.

- Khogeer H, Alfattani A, Al Kaff M, et al. Antiphosphatidylserine antibodies as diagnostic indicators of antiphospholipid syndrome. Lupus. 2015;24:186-190.

- Gibson GE, Su WP, Pittelkow MR. Antiphospholipid syndrome and the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36(6 pt 1):970-982.

- Francès C, Papo T, Wechsler B, et al. Sneddon syndrome with or without antiphospholipid antibodies. a comparative study in 46 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1999;78:209-219.

- Vasudevan B, Neema S, Verma R. Livedoid vasculopathy: a review of pathogenesis and principles of management. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:478-488.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews' Diseases Of The Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2006.

- Samlaska CP, James WD. Superficial thrombophlebitis. II. secondary hypercoagulable states. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23:1-18.

- Rigdon EE. Trousseau's syndrome and acute arterial thrombosis. Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;8:214-218.

- Carrier M, Le Gal G, Wells PS, et al. Systematic review: the Trousseau syndrome revisited: should we screen extensively for cancer in patients with venous thromboembolism? Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:323-333.

- Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, et al. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:295-306.

- Bertolaccini ML, Amengual O, Atsumi T, et al. 'Non-criteria' aPL tests: report of a task force and preconference workshop at the 13th International Congress on Antiphospholipid Antibodies, Galveston, TX, USA, April 2010. Lupus. 2011;20:191-205.

- Khogeer H, Alfattani A, Al Kaff M, et al. Antiphosphatidylserine antibodies as diagnostic indicators of antiphospholipid syndrome. Lupus. 2015;24:186-190.

- Gibson GE, Su WP, Pittelkow MR. Antiphospholipid syndrome and the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36(6 pt 1):970-982.

- Francès C, Papo T, Wechsler B, et al. Sneddon syndrome with or without antiphospholipid antibodies. a comparative study in 46 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1999;78:209-219.

- Vasudevan B, Neema S, Verma R. Livedoid vasculopathy: a review of pathogenesis and principles of management. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:478-488.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews' Diseases Of The Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2006.

A 32-year-old woman presented for evaluation of small, tender, erythematous nodules on the lower legs of 1 year's duration that had started to spread to the thighs over several months prior to presentation. The patient reported no history of ulceration or other cutaneous findings. On physical examination, a hyperpigmented, linear to reticular pattern was noted on the lower legs with a few 1-cm, erythematous, mildly indurated and tender subcutaneous nodules. The patient denied any recent medical procedures, history of malignancy or cardiovascular disease, use of tobacco or illicit drugs, prolonged contact with a heat source, recent unintentional weight loss, fevers, or night sweats. Her medical history was notable for asthma and migraines, which were treated with albuterol, fluticasone, and topiramate.