User login

Projected 2023 Cost Reduction From Tumor Necrosis Factor α Inhibitor Biosimilars in Dermatology: A National Medicare Analysis

To the Editor:

Although biologics provide major therapeutic benefits for dermatologic conditions, they also come with a substantial cost, making them among the most expensive medications available. Medicare and Medicaid spending on biologics for dermatologic conditions increased by 320% from 2012 to 2018, reaching a staggering $10.6 billion in 2018 alone.1 Biosimilars show promise in reducing health care spending for dermatologic conditions; however, their utilization has been limited due to multiple factors, including delayed market entry from patent thickets, exclusionary formulary contracts, and prescriber skepticism regarding their safety and efficacy.2 For instance, a national survey of 1201 US physicians in specialties that are high prescribers of biologics reported that 55% doubted the safety and appropriateness of biosimilars.3

US Food and Drug Administration approval of biosimilars for adalimumab and etanercept offers the potential to reduce health care spending for dermatologic conditions. However, this cost reduction is dependent on utilization rates among dermatologists. In this national cross-sectional review of Medicare data, we predicted the impact of these biosimilars on dermatologic Medicare costs and demonstrated how differing utilization rates among dermatologists can influence potential savings.

To model 2023 utilization and cost reduction from biosimilars, we analyzed Medicare Part D data from 2020 on existing biosimilars, including granulocyte colony–stimulating factors, erythropoiesis-stimulating agents, and tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors.4 Methods in line with a 2021 report from the US Department of Health and Human Services5 as well as those of Yazdany et al6 were used. For each class, we calculated the 2020 distribution of biosimilar and originator drug claims as well as biosimilar cost reduction per 30-day claim. We utilized 2018-2021 annual growth rates for branded adalimumab and etanercept to estimate 30-day claims for 2023 and the cost of these branded agents in the absence of biosimilars. The hypothetical 2023 cost reduction from adalimumab and etanercept biosimilars was estimated by assuming 2020 biosimilar utilization rates and mean cost reduction per claim. This study utilized publicly available or aggregate summary data (not attributable to specific patients) and did not qualify as human subject research; therefore, institutional review board approval was not required.

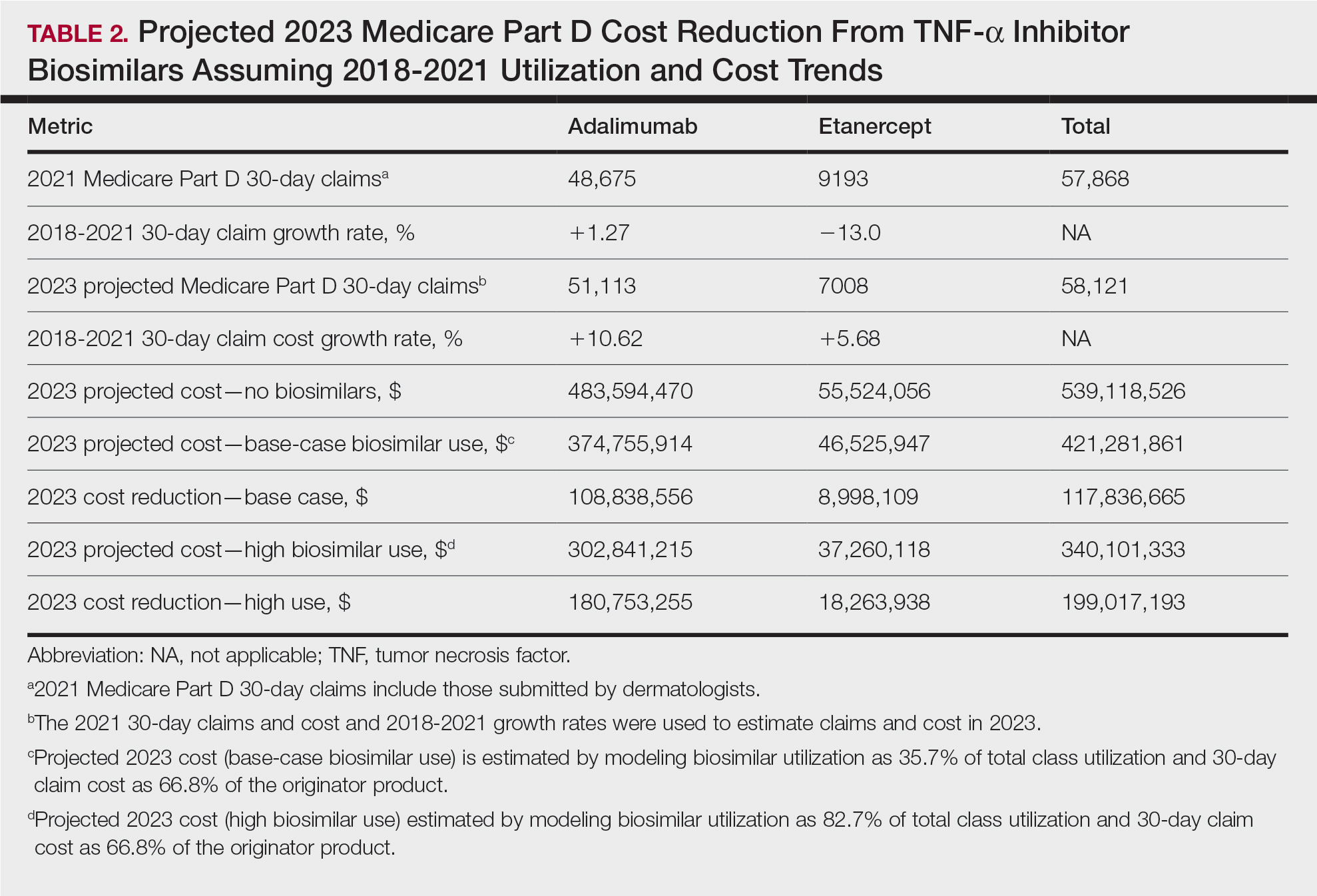

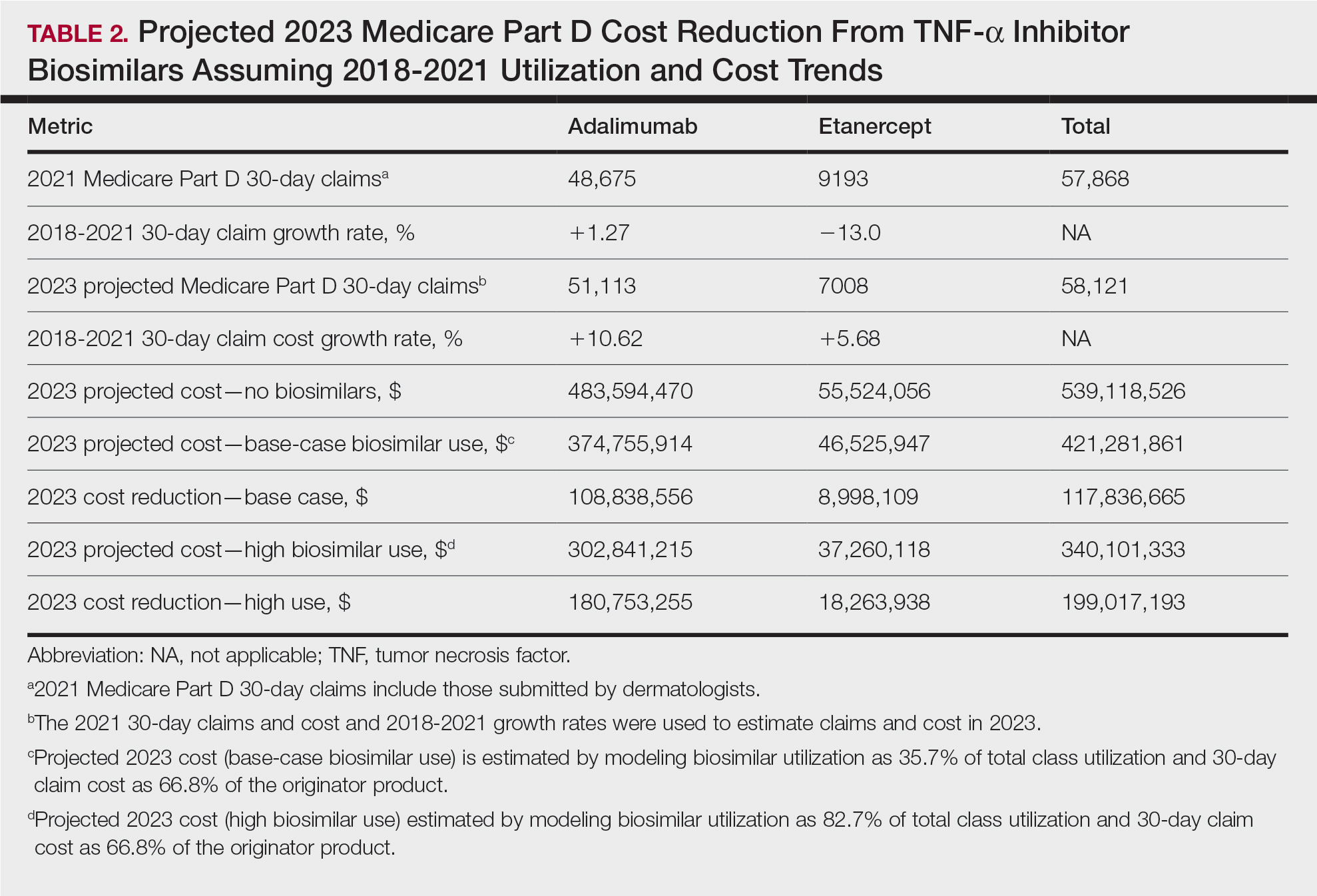

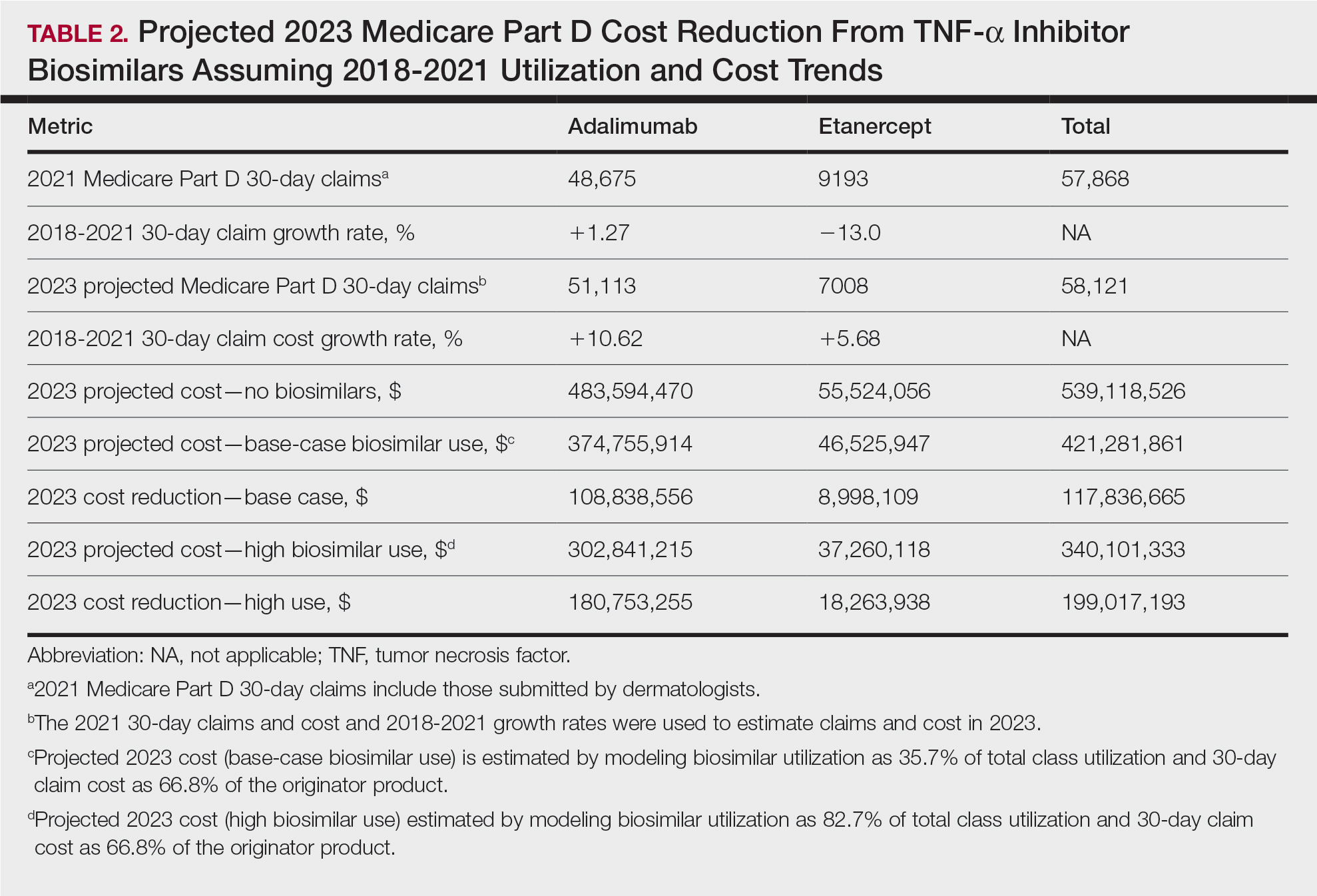

In 2020, biosimilar utilization proportions ranged from 6.4% (tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors) to 82.7% (granulocyte colony–stimulating factors), with a mean across all classes of 35.7%. On average, the cost per 30-day claim of biosimilars was 66.8% of originator agents (Table 1). In 2021, we identified 57,868 30-day claims for branded adalimumab and etanercept submitted by dermatologists. From 2018 to 2021, 30-day branded adalimumab claims increased by 1.27% annually (cost + 10.62% annually), while claims for branded etanercept decreased by 13.0% annually (cost + 5.68% annually). Assuming these trends, the cost of branded adalimumab and etanercept was estimated to be $539 million in 2023. Applying the aforementioned 35.7% utilization, the introduction of biosimilars in dermatology would yield a cost reduction of approximately $118 million (21.9%). A high utilization rate (82.7%) of biosimilars among dermatologists would increase cost savings to $199 million (36.9%)(Table 2).

Our study demonstrates that the introduction of 2 biosimilars into dermatology may result in a notable reduction in Medicare expenditures. The savings observed are likely to translate to substantial cost savings for patients. A cross-sectional analysis of 2020 Medicare data indicated that coverage for psoriasis medications was 10.0% to 99.8% across different products and Medicare Part D plans. Consequently, patients faced considerable out-of-pocket expenses, amounting to $5653 and $5714 per year for adalimumab and etanercept, respectively.7

We found that the extent of savings from biosimilars was dependent on the utilization rates among dermatologists, with the highest utilization rate almost doubling the total savings of average utilization rates. Given the impact of high utilization and the wide variation observed, understanding the factors that have influenced uptake of biosimilars is important to increasing utilization as these medications become integrated into dermatology. For instance, limited uptake of infliximab initially may have been influenced by concerns about efficacy and increased adverse events.8,9 In contrast, the high utilization of filgrastim biosimilars (82.7%) may be attributed to its longevity in the market and familiarity to prescribers, as filgrastim was the first biosimilar to be approved in the United States.10

Promoting reasonable utilization of biosimilars may require prescriber education on their safety and approval processes, which could foster increased utilization and reduce skepticism.4 Under the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act, the US Food and Drug Administration approves biosimilars only when they exhibit “high similarity” and show no “clinically meaningful differences” compared to the reference biologic, with no added safety risks or reduced efficacy.11 Moreover, a 2023 systematic review of 17 studies found no major difference in efficacy and safety between biosimilars and originators of etanercept, infliximab, and other biologics.12 Understanding these findings may reassure dermatologists and patients about the reliability and safety of biosimilars.

A limitation of our study is that it solely assesses Medicare data and estimates derived from existing (separate) biologic classes. It also does not account for potential expenditure shifts to newer biologic agents (eg, IL-12/17/23 inhibitors) or changes in manufacturer behavior or promotions. Nevertheless, it indicates notable financial savings from new biosimilar agents in dermatology; along with their compelling efficacy and safety profiles, this could represent a substantial benefit to patients and the health care system.

- Price KN, Atluri S, Hsiao JL, et al. Medicare and medicaid spending trends for immunomodulators prescribed for dermatologic conditions. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;33:575-579.

- Zhai MZ, Sarpatwari A, Kesselheim AS. Why are biosimilars not living up to their promise in the US? AMA J Ethics. 2019;21:E668-E678. doi:10.1001/amajethics.2019.668

- Cohen H, Beydoun D, Chien D, et al. Awareness, knowledge, and perceptions of biosimilars among specialty physicians. Adv Ther. 2017;33:2160-2172.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Part D prescribers— by provider and drug. Accessed September 11, 2024. https://data.cms.gov/provider-summary-by-type-of-service/medicare-part-d-prescribers/medicare-part-d-prescribers-by-provider-and-drug/data

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Inspector General. Medicare Part D and beneficiaries could realize significant spending reductions with increased biosimilar use. Accessed September 11, 2024. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/OEI-05-20-00480.pdf

- Yazdany J, Dudley RA, Lin GA, et al. Out-of-pocket costs for infliximab and its biosimilar for rheumatoid arthritis under Medicare Part D. JAMA. 2018;320:931-933. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.7316

- Pourali SP, Nshuti L, Dusetzina SB. Out-of-pocket costs of specialty medications for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis treatment in the medicare population. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1239-1241. doi:10.1001/ jamadermatol.2021.3616

- Lebwohl M. Biosimilars in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2021; 157:641-642. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0219

- Westerkam LL, Tackett KJ, Sayed CJ. Comparing the effectiveness and safety associated with infliximab vs infliximab-abda therapy for patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:708-711. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0220

- Awad M, Singh P, Hilas O. Zarxio (Filgrastim-sndz): the first biosimilar approved by the FDA. P T. 2017;42:19-23.

- Development of therapeutic protein biosimilars: comparative analytical assessment and other quality-related considerations guidance for industry. US Department of Health and Human Services website. Updated June 15, 2022. Accessed October 21, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/development-therapeutic-protein-biosimilars-comparative-analyticalassessment-and-other-quality

- Phan DB, Elyoussfi S, Stevenson M, et al. Biosimilars for the treatment of psoriasis: a systematic review of clinical trials and observational studies. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:763-771. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.1338

To the Editor:

Although biologics provide major therapeutic benefits for dermatologic conditions, they also come with a substantial cost, making them among the most expensive medications available. Medicare and Medicaid spending on biologics for dermatologic conditions increased by 320% from 2012 to 2018, reaching a staggering $10.6 billion in 2018 alone.1 Biosimilars show promise in reducing health care spending for dermatologic conditions; however, their utilization has been limited due to multiple factors, including delayed market entry from patent thickets, exclusionary formulary contracts, and prescriber skepticism regarding their safety and efficacy.2 For instance, a national survey of 1201 US physicians in specialties that are high prescribers of biologics reported that 55% doubted the safety and appropriateness of biosimilars.3

US Food and Drug Administration approval of biosimilars for adalimumab and etanercept offers the potential to reduce health care spending for dermatologic conditions. However, this cost reduction is dependent on utilization rates among dermatologists. In this national cross-sectional review of Medicare data, we predicted the impact of these biosimilars on dermatologic Medicare costs and demonstrated how differing utilization rates among dermatologists can influence potential savings.

To model 2023 utilization and cost reduction from biosimilars, we analyzed Medicare Part D data from 2020 on existing biosimilars, including granulocyte colony–stimulating factors, erythropoiesis-stimulating agents, and tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors.4 Methods in line with a 2021 report from the US Department of Health and Human Services5 as well as those of Yazdany et al6 were used. For each class, we calculated the 2020 distribution of biosimilar and originator drug claims as well as biosimilar cost reduction per 30-day claim. We utilized 2018-2021 annual growth rates for branded adalimumab and etanercept to estimate 30-day claims for 2023 and the cost of these branded agents in the absence of biosimilars. The hypothetical 2023 cost reduction from adalimumab and etanercept biosimilars was estimated by assuming 2020 biosimilar utilization rates and mean cost reduction per claim. This study utilized publicly available or aggregate summary data (not attributable to specific patients) and did not qualify as human subject research; therefore, institutional review board approval was not required.

In 2020, biosimilar utilization proportions ranged from 6.4% (tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors) to 82.7% (granulocyte colony–stimulating factors), with a mean across all classes of 35.7%. On average, the cost per 30-day claim of biosimilars was 66.8% of originator agents (Table 1). In 2021, we identified 57,868 30-day claims for branded adalimumab and etanercept submitted by dermatologists. From 2018 to 2021, 30-day branded adalimumab claims increased by 1.27% annually (cost + 10.62% annually), while claims for branded etanercept decreased by 13.0% annually (cost + 5.68% annually). Assuming these trends, the cost of branded adalimumab and etanercept was estimated to be $539 million in 2023. Applying the aforementioned 35.7% utilization, the introduction of biosimilars in dermatology would yield a cost reduction of approximately $118 million (21.9%). A high utilization rate (82.7%) of biosimilars among dermatologists would increase cost savings to $199 million (36.9%)(Table 2).

Our study demonstrates that the introduction of 2 biosimilars into dermatology may result in a notable reduction in Medicare expenditures. The savings observed are likely to translate to substantial cost savings for patients. A cross-sectional analysis of 2020 Medicare data indicated that coverage for psoriasis medications was 10.0% to 99.8% across different products and Medicare Part D plans. Consequently, patients faced considerable out-of-pocket expenses, amounting to $5653 and $5714 per year for adalimumab and etanercept, respectively.7

We found that the extent of savings from biosimilars was dependent on the utilization rates among dermatologists, with the highest utilization rate almost doubling the total savings of average utilization rates. Given the impact of high utilization and the wide variation observed, understanding the factors that have influenced uptake of biosimilars is important to increasing utilization as these medications become integrated into dermatology. For instance, limited uptake of infliximab initially may have been influenced by concerns about efficacy and increased adverse events.8,9 In contrast, the high utilization of filgrastim biosimilars (82.7%) may be attributed to its longevity in the market and familiarity to prescribers, as filgrastim was the first biosimilar to be approved in the United States.10

Promoting reasonable utilization of biosimilars may require prescriber education on their safety and approval processes, which could foster increased utilization and reduce skepticism.4 Under the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act, the US Food and Drug Administration approves biosimilars only when they exhibit “high similarity” and show no “clinically meaningful differences” compared to the reference biologic, with no added safety risks or reduced efficacy.11 Moreover, a 2023 systematic review of 17 studies found no major difference in efficacy and safety between biosimilars and originators of etanercept, infliximab, and other biologics.12 Understanding these findings may reassure dermatologists and patients about the reliability and safety of biosimilars.

A limitation of our study is that it solely assesses Medicare data and estimates derived from existing (separate) biologic classes. It also does not account for potential expenditure shifts to newer biologic agents (eg, IL-12/17/23 inhibitors) or changes in manufacturer behavior or promotions. Nevertheless, it indicates notable financial savings from new biosimilar agents in dermatology; along with their compelling efficacy and safety profiles, this could represent a substantial benefit to patients and the health care system.

To the Editor:

Although biologics provide major therapeutic benefits for dermatologic conditions, they also come with a substantial cost, making them among the most expensive medications available. Medicare and Medicaid spending on biologics for dermatologic conditions increased by 320% from 2012 to 2018, reaching a staggering $10.6 billion in 2018 alone.1 Biosimilars show promise in reducing health care spending for dermatologic conditions; however, their utilization has been limited due to multiple factors, including delayed market entry from patent thickets, exclusionary formulary contracts, and prescriber skepticism regarding their safety and efficacy.2 For instance, a national survey of 1201 US physicians in specialties that are high prescribers of biologics reported that 55% doubted the safety and appropriateness of biosimilars.3

US Food and Drug Administration approval of biosimilars for adalimumab and etanercept offers the potential to reduce health care spending for dermatologic conditions. However, this cost reduction is dependent on utilization rates among dermatologists. In this national cross-sectional review of Medicare data, we predicted the impact of these biosimilars on dermatologic Medicare costs and demonstrated how differing utilization rates among dermatologists can influence potential savings.

To model 2023 utilization and cost reduction from biosimilars, we analyzed Medicare Part D data from 2020 on existing biosimilars, including granulocyte colony–stimulating factors, erythropoiesis-stimulating agents, and tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors.4 Methods in line with a 2021 report from the US Department of Health and Human Services5 as well as those of Yazdany et al6 were used. For each class, we calculated the 2020 distribution of biosimilar and originator drug claims as well as biosimilar cost reduction per 30-day claim. We utilized 2018-2021 annual growth rates for branded adalimumab and etanercept to estimate 30-day claims for 2023 and the cost of these branded agents in the absence of biosimilars. The hypothetical 2023 cost reduction from adalimumab and etanercept biosimilars was estimated by assuming 2020 biosimilar utilization rates and mean cost reduction per claim. This study utilized publicly available or aggregate summary data (not attributable to specific patients) and did not qualify as human subject research; therefore, institutional review board approval was not required.

In 2020, biosimilar utilization proportions ranged from 6.4% (tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors) to 82.7% (granulocyte colony–stimulating factors), with a mean across all classes of 35.7%. On average, the cost per 30-day claim of biosimilars was 66.8% of originator agents (Table 1). In 2021, we identified 57,868 30-day claims for branded adalimumab and etanercept submitted by dermatologists. From 2018 to 2021, 30-day branded adalimumab claims increased by 1.27% annually (cost + 10.62% annually), while claims for branded etanercept decreased by 13.0% annually (cost + 5.68% annually). Assuming these trends, the cost of branded adalimumab and etanercept was estimated to be $539 million in 2023. Applying the aforementioned 35.7% utilization, the introduction of biosimilars in dermatology would yield a cost reduction of approximately $118 million (21.9%). A high utilization rate (82.7%) of biosimilars among dermatologists would increase cost savings to $199 million (36.9%)(Table 2).

Our study demonstrates that the introduction of 2 biosimilars into dermatology may result in a notable reduction in Medicare expenditures. The savings observed are likely to translate to substantial cost savings for patients. A cross-sectional analysis of 2020 Medicare data indicated that coverage for psoriasis medications was 10.0% to 99.8% across different products and Medicare Part D plans. Consequently, patients faced considerable out-of-pocket expenses, amounting to $5653 and $5714 per year for adalimumab and etanercept, respectively.7

We found that the extent of savings from biosimilars was dependent on the utilization rates among dermatologists, with the highest utilization rate almost doubling the total savings of average utilization rates. Given the impact of high utilization and the wide variation observed, understanding the factors that have influenced uptake of biosimilars is important to increasing utilization as these medications become integrated into dermatology. For instance, limited uptake of infliximab initially may have been influenced by concerns about efficacy and increased adverse events.8,9 In contrast, the high utilization of filgrastim biosimilars (82.7%) may be attributed to its longevity in the market and familiarity to prescribers, as filgrastim was the first biosimilar to be approved in the United States.10

Promoting reasonable utilization of biosimilars may require prescriber education on their safety and approval processes, which could foster increased utilization and reduce skepticism.4 Under the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act, the US Food and Drug Administration approves biosimilars only when they exhibit “high similarity” and show no “clinically meaningful differences” compared to the reference biologic, with no added safety risks or reduced efficacy.11 Moreover, a 2023 systematic review of 17 studies found no major difference in efficacy and safety between biosimilars and originators of etanercept, infliximab, and other biologics.12 Understanding these findings may reassure dermatologists and patients about the reliability and safety of biosimilars.

A limitation of our study is that it solely assesses Medicare data and estimates derived from existing (separate) biologic classes. It also does not account for potential expenditure shifts to newer biologic agents (eg, IL-12/17/23 inhibitors) or changes in manufacturer behavior or promotions. Nevertheless, it indicates notable financial savings from new biosimilar agents in dermatology; along with their compelling efficacy and safety profiles, this could represent a substantial benefit to patients and the health care system.

- Price KN, Atluri S, Hsiao JL, et al. Medicare and medicaid spending trends for immunomodulators prescribed for dermatologic conditions. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;33:575-579.

- Zhai MZ, Sarpatwari A, Kesselheim AS. Why are biosimilars not living up to their promise in the US? AMA J Ethics. 2019;21:E668-E678. doi:10.1001/amajethics.2019.668

- Cohen H, Beydoun D, Chien D, et al. Awareness, knowledge, and perceptions of biosimilars among specialty physicians. Adv Ther. 2017;33:2160-2172.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Part D prescribers— by provider and drug. Accessed September 11, 2024. https://data.cms.gov/provider-summary-by-type-of-service/medicare-part-d-prescribers/medicare-part-d-prescribers-by-provider-and-drug/data

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Inspector General. Medicare Part D and beneficiaries could realize significant spending reductions with increased biosimilar use. Accessed September 11, 2024. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/OEI-05-20-00480.pdf

- Yazdany J, Dudley RA, Lin GA, et al. Out-of-pocket costs for infliximab and its biosimilar for rheumatoid arthritis under Medicare Part D. JAMA. 2018;320:931-933. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.7316

- Pourali SP, Nshuti L, Dusetzina SB. Out-of-pocket costs of specialty medications for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis treatment in the medicare population. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1239-1241. doi:10.1001/ jamadermatol.2021.3616

- Lebwohl M. Biosimilars in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2021; 157:641-642. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0219

- Westerkam LL, Tackett KJ, Sayed CJ. Comparing the effectiveness and safety associated with infliximab vs infliximab-abda therapy for patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:708-711. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0220

- Awad M, Singh P, Hilas O. Zarxio (Filgrastim-sndz): the first biosimilar approved by the FDA. P T. 2017;42:19-23.

- Development of therapeutic protein biosimilars: comparative analytical assessment and other quality-related considerations guidance for industry. US Department of Health and Human Services website. Updated June 15, 2022. Accessed October 21, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/development-therapeutic-protein-biosimilars-comparative-analyticalassessment-and-other-quality

- Phan DB, Elyoussfi S, Stevenson M, et al. Biosimilars for the treatment of psoriasis: a systematic review of clinical trials and observational studies. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:763-771. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.1338

- Price KN, Atluri S, Hsiao JL, et al. Medicare and medicaid spending trends for immunomodulators prescribed for dermatologic conditions. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;33:575-579.

- Zhai MZ, Sarpatwari A, Kesselheim AS. Why are biosimilars not living up to their promise in the US? AMA J Ethics. 2019;21:E668-E678. doi:10.1001/amajethics.2019.668

- Cohen H, Beydoun D, Chien D, et al. Awareness, knowledge, and perceptions of biosimilars among specialty physicians. Adv Ther. 2017;33:2160-2172.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Part D prescribers— by provider and drug. Accessed September 11, 2024. https://data.cms.gov/provider-summary-by-type-of-service/medicare-part-d-prescribers/medicare-part-d-prescribers-by-provider-and-drug/data

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Inspector General. Medicare Part D and beneficiaries could realize significant spending reductions with increased biosimilar use. Accessed September 11, 2024. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/OEI-05-20-00480.pdf

- Yazdany J, Dudley RA, Lin GA, et al. Out-of-pocket costs for infliximab and its biosimilar for rheumatoid arthritis under Medicare Part D. JAMA. 2018;320:931-933. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.7316

- Pourali SP, Nshuti L, Dusetzina SB. Out-of-pocket costs of specialty medications for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis treatment in the medicare population. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1239-1241. doi:10.1001/ jamadermatol.2021.3616

- Lebwohl M. Biosimilars in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2021; 157:641-642. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0219

- Westerkam LL, Tackett KJ, Sayed CJ. Comparing the effectiveness and safety associated with infliximab vs infliximab-abda therapy for patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:708-711. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0220

- Awad M, Singh P, Hilas O. Zarxio (Filgrastim-sndz): the first biosimilar approved by the FDA. P T. 2017;42:19-23.

- Development of therapeutic protein biosimilars: comparative analytical assessment and other quality-related considerations guidance for industry. US Department of Health and Human Services website. Updated June 15, 2022. Accessed October 21, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/development-therapeutic-protein-biosimilars-comparative-analyticalassessment-and-other-quality

- Phan DB, Elyoussfi S, Stevenson M, et al. Biosimilars for the treatment of psoriasis: a systematic review of clinical trials and observational studies. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:763-771. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.1338

Practice Points

- Biosimilars for adalimumab and etanercept are safe and effective alternatives with the potential to reduce health care costs in dermatology by approximately $118 million.

- A high utilization rate of biosimilars by dermatologists would increase cost savings even further.

Concordance Between Dermatologist Self-reported and Industry-Reported Interactions at a National Dermatology Conference

Interactions between industry and physicians, including dermatologists, are widely prevalent.1-3 Proper reporting of industry relationships is essential for transparency, objectivity, and management of potential biases and conflicts of interest. There has been increasing public scrutiny regarding these interactions.

The Physician Payments Sunshine Act established Open Payments (OP), a publicly available database that collects and displays industry-reported physician-industry interactions.4,5 For the medical community and public, the OP database may be used to assess transparency by comparing the data with physician self-disclosures. There is a paucity of studies in the literature examining the concordance of industry-reported disclosures and physician self-reported data, with even fewer studies utilizing OP as a source of industry disclosures, and none exists for dermatology.6-12 It also is not clear to what extent the OP database captures all possible dermatologist-industry interactions, as the Sunshine Act only mandates reporting by applicable US-based manufacturers and group purchasing organizations that produce or purchase drugs or devices that require a prescription and are reimbursable by a government-run health care program.5 As a result, certain companies, such as cosmeceuticals, may not be represented.

In this study we aimed to evaluate the concordance of dermatologist self-disclosure of industry relationships and those reported on OP. Specifically, we focused on interactions disclosed by presenters at the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) 73rd Annual Meeting in San Francisco, California (March 20–24, 2015), and those by industry in the 2014 OP database.

Methods

In this retrospective cohort study, we compared publicly available data from the OP database to presenter disclosures found in the publicly available AAD 73rd Annual Meeting program (AADMP). The AAD required speakers to disclose financial relationships with industry within the 12 months preceding the presentation, as outlined in the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education guidelines.13 All AAD presenters who were dermatologists practicing in the United States were included in the analysis, whereas residents, fellows, nonphysicians, nondermatologist physicians, and international dermatologists were excluded.

We examined general, research, and associated research payments to specific dermatologists using the 2014 OP data, which contained industry payments made between January 1 and December 31, 2014. Open Payments defined research payments as direct payment to the physician for different types of research activities and associated research payments as indirect payments made to a research institution or entity where the physician was named the principal investigator.5 We chose the 2014 database because it most closely matched the period of required disclosures defined by the AAD for the 2015 meeting. Our review of the OP data occurred after the June 2016 update and thus included the most accurate and up-to-date financial interactions.

We conducted our analysis in 2 major steps. First, we determined whether each industry interaction reported in the OP database was present in the AADMP, which provided an assessment of interaction-level concordance. Second, we determined whether all the industry interactions for any given dermatologist listed in the OP also were present in AADMP, which provided an assessment of dermatologist-level concordance.

First, to establish interaction-level concordance for each industry interaction, the company name and the type of interaction (eg, consultant, speaker, investigator) listed in the AADMP were compared with the data in OP to verify a match. Each interaction was assigned into one of the categories of concordant disclosure (a match of both the company name and type of interaction details in OP and the AADMP), overdisclosure (the presence of an AADMP interaction not found in OP, such as an additional type of interaction or company), or underdisclosure (a company name or type of interaction found in OP but not reported in the AADMP). For underdisclosure, we further classified into company present or company absent based on whether the dermatologist disclosed any relationship with a particular company in the AADMP. We considered the type of interaction to be matching if they were identical or similar in nature (eg, consulting in OP and advisory board in the AADMP), as the types of interactions are reported differently in OP and the AADMP. Otherwise, if they were not similar enough (eg, education in OP and stockholder in the AADMP), it was classified as underdisclosure. Some types of interactions reported in OP were not available on the AAD disclosure form. For example, food and beverage as well as travel and lodging were types of interactions in OP that did not exist in the AADMP. These 2 types of interactions comprised a large majority of OP payment entries but only accounted for a small percentage of the payment amount. Analysis was performed both including and excluding interactions for food, beverage, travel, and lodging (f/b/t/l) to best account for differences in interaction categories between OP and the AADMP.

Second, each dermatologist was assigned to an overall disclosure category of dermatologist-level concordance based on the status for all his/her interactions. Categories included no disclosure (no industry interactions in OP and the AADMP), concordant (all industry interactions reported in OP and the AADMP match), overdisclosure only (no industry interactions on OP but self-reported interactions present in the AADMP), and discordant (not all OP interactions were disclosed in the AADMP). The discordant category was further divided into with overdisclosure and without overdisclosure, depending on the presence or absence of industry relationships listed in the AADMP but not in OP, respectively.

To ensure uniformity, one individual (A.F.S.) reviewed and collected the data from OP and the AADMP. Information on gender and academic affiliation of study participants was obtained from information listed in the AADMP and Google searches. Data management was performed with Microsoft Excel software (Microsoft Excel 2010, Version 14.0, Microsoft Corporation). The New York University School of Medicine’s (New York, New York) institutional review board exempted this study.

Results

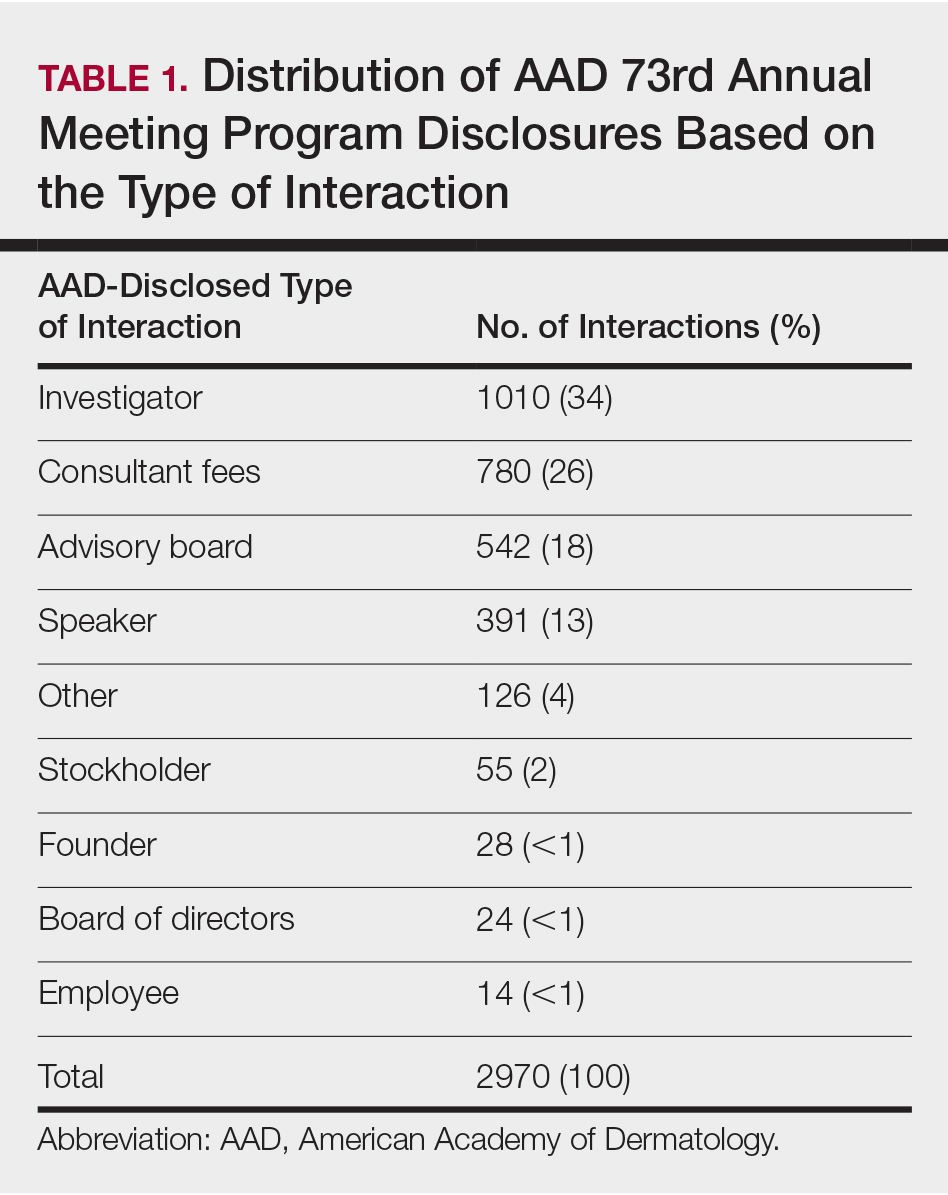

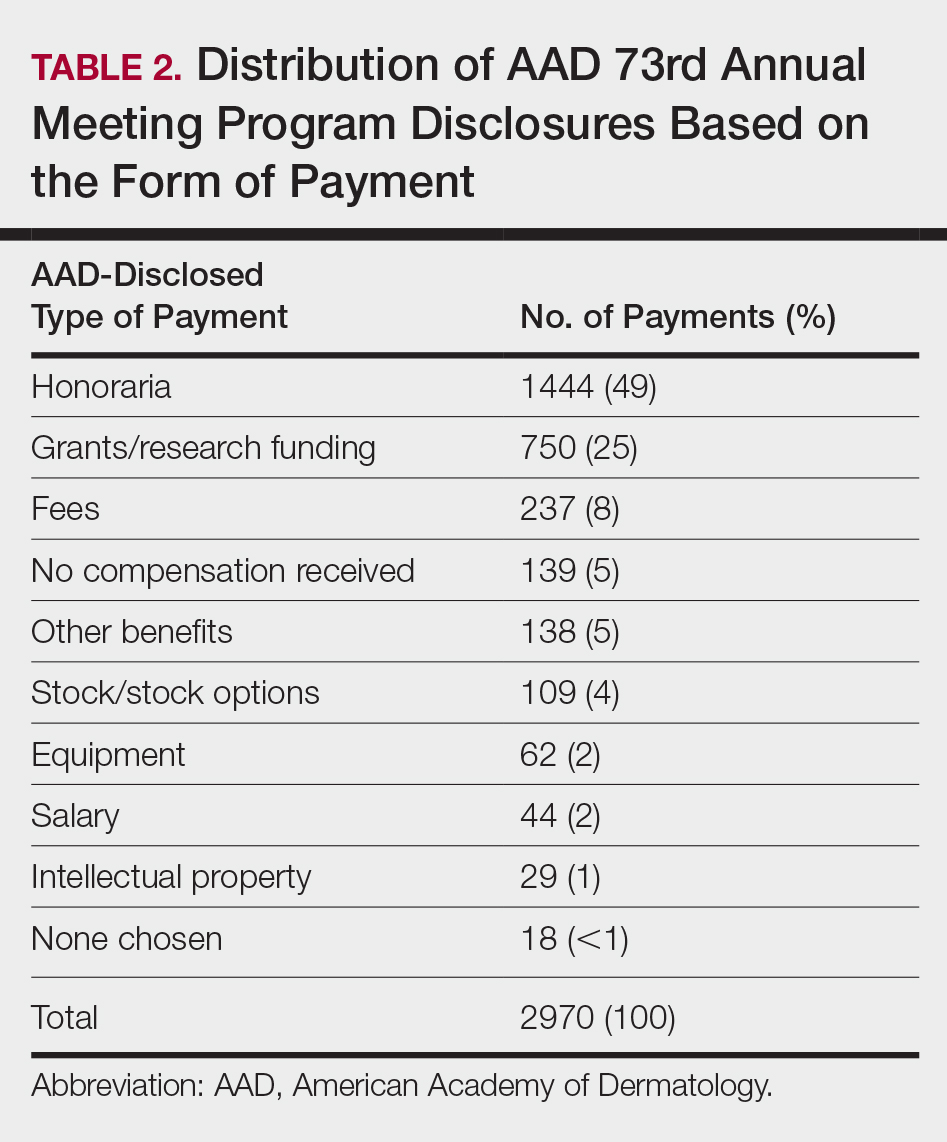

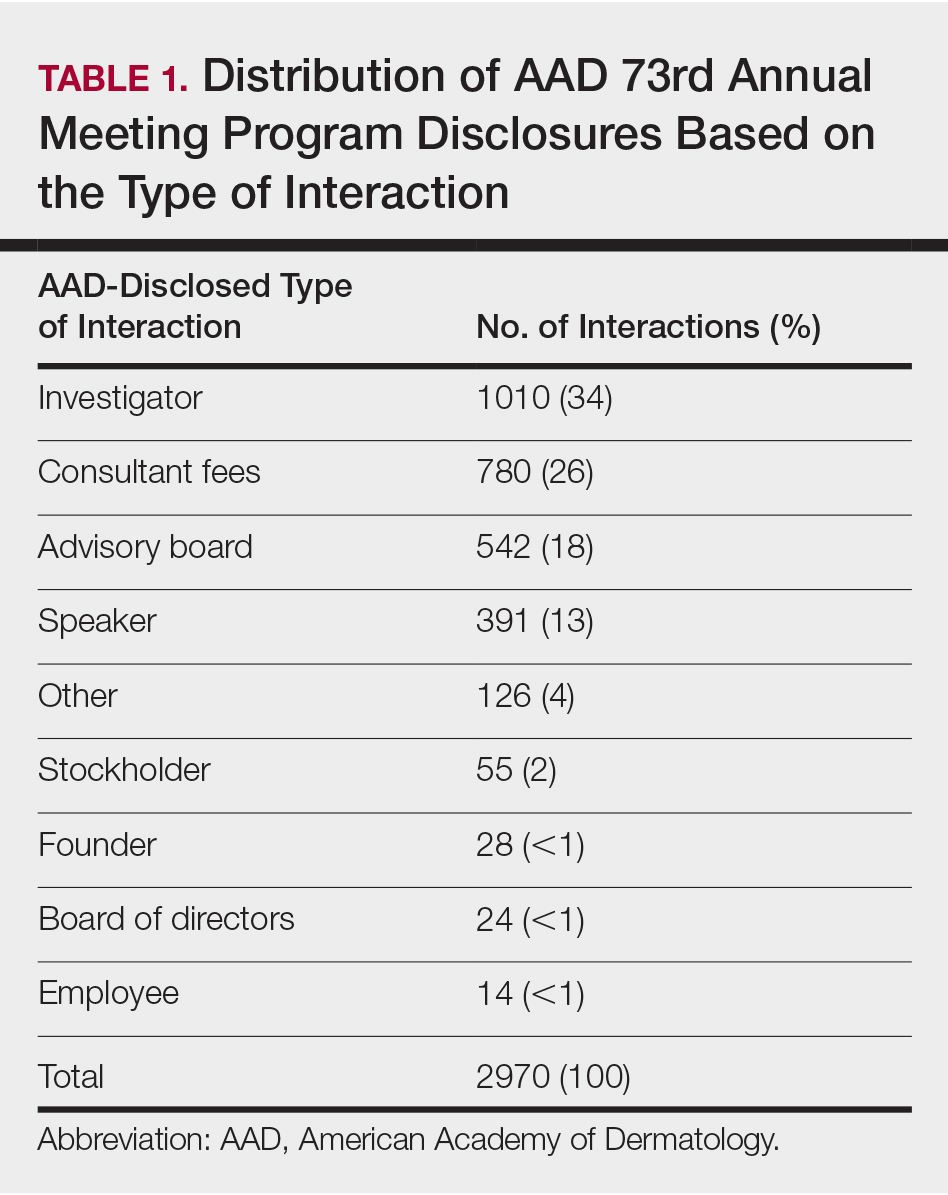

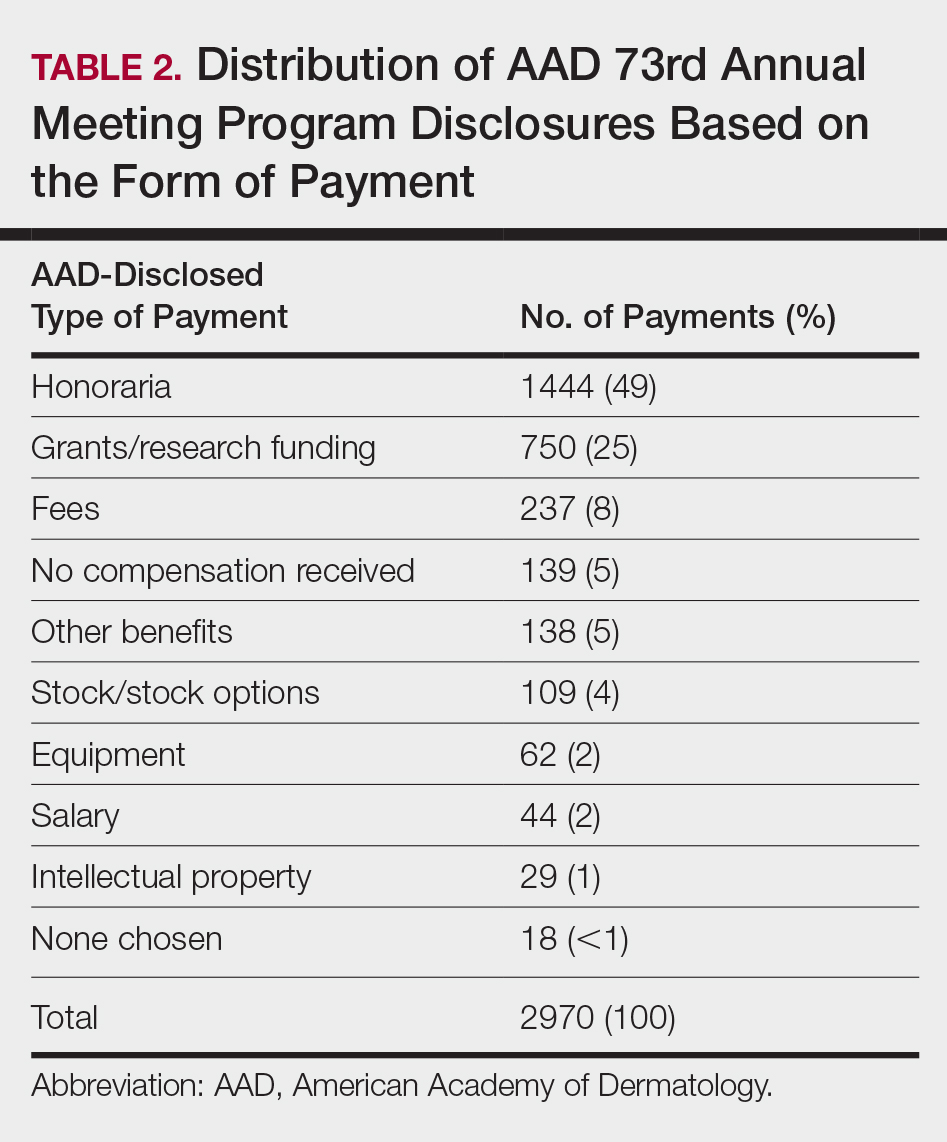

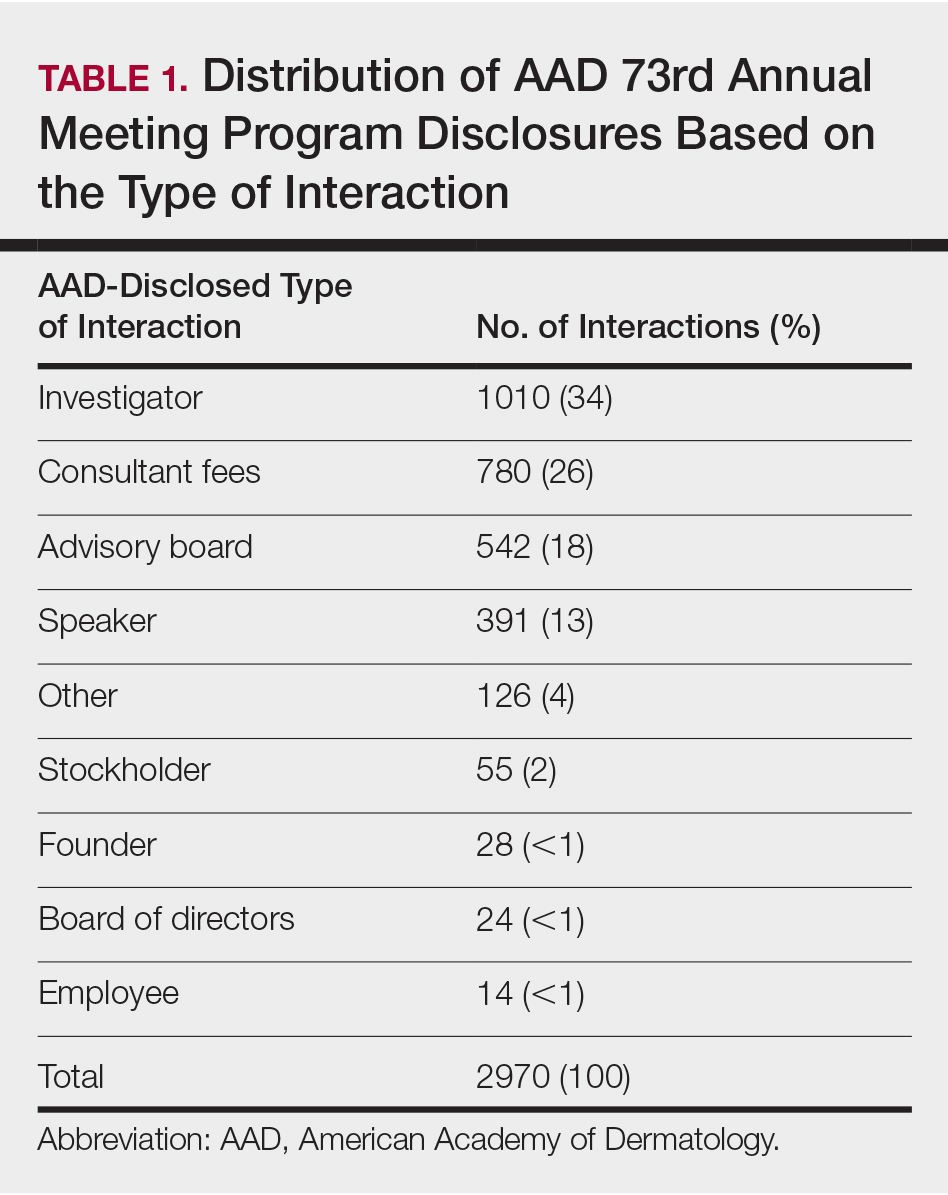

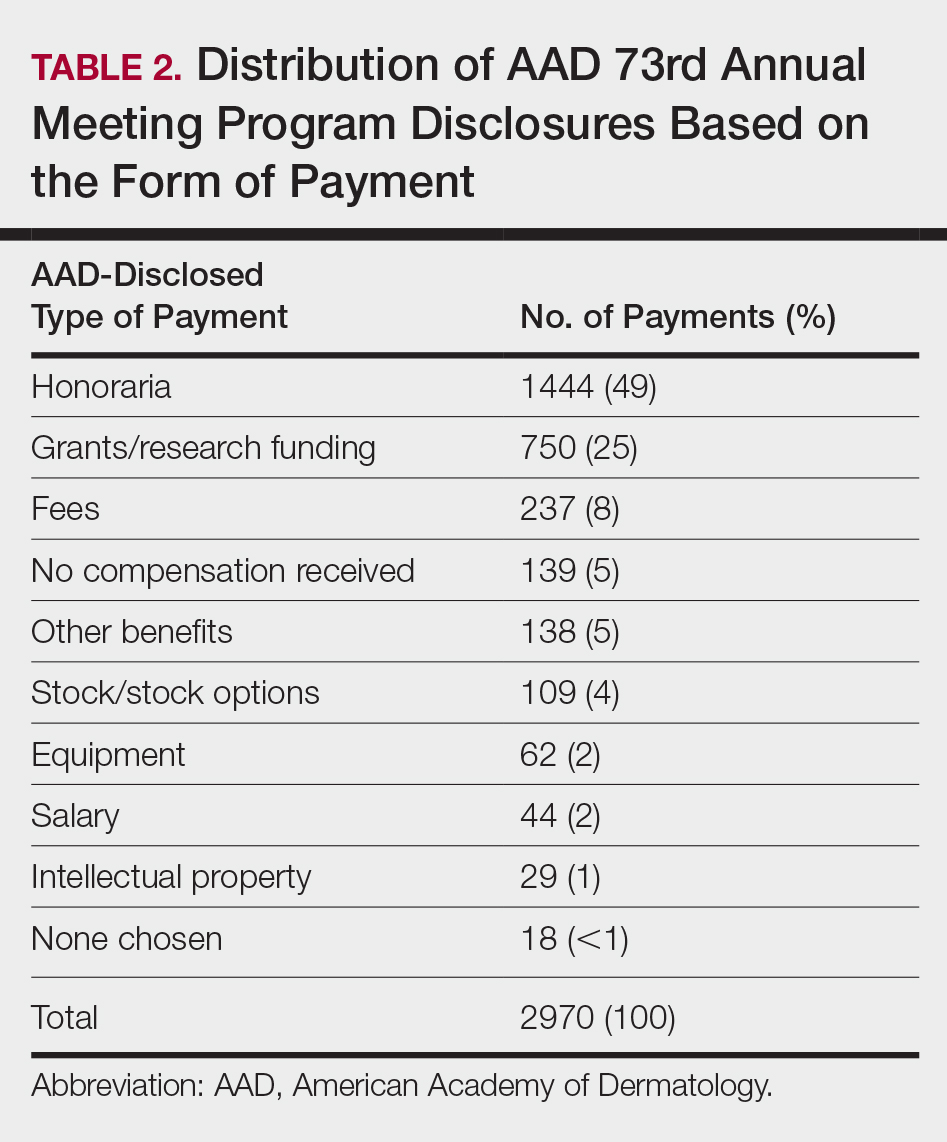

Of the 938 presenters listed in the AADMP, 768 individuals met the inclusion criteria. The most commonly cited type of relationship with industry listed in the AADMP was serving as an investigator, consultant, or advisory board member, comprising 34%, 26%, and 18%, respectively (Table 1). The forms of payment most frequently reported in the AADMP were honoraria and grants/research funding, comprising 49% and 25%, respectively (Table 2).

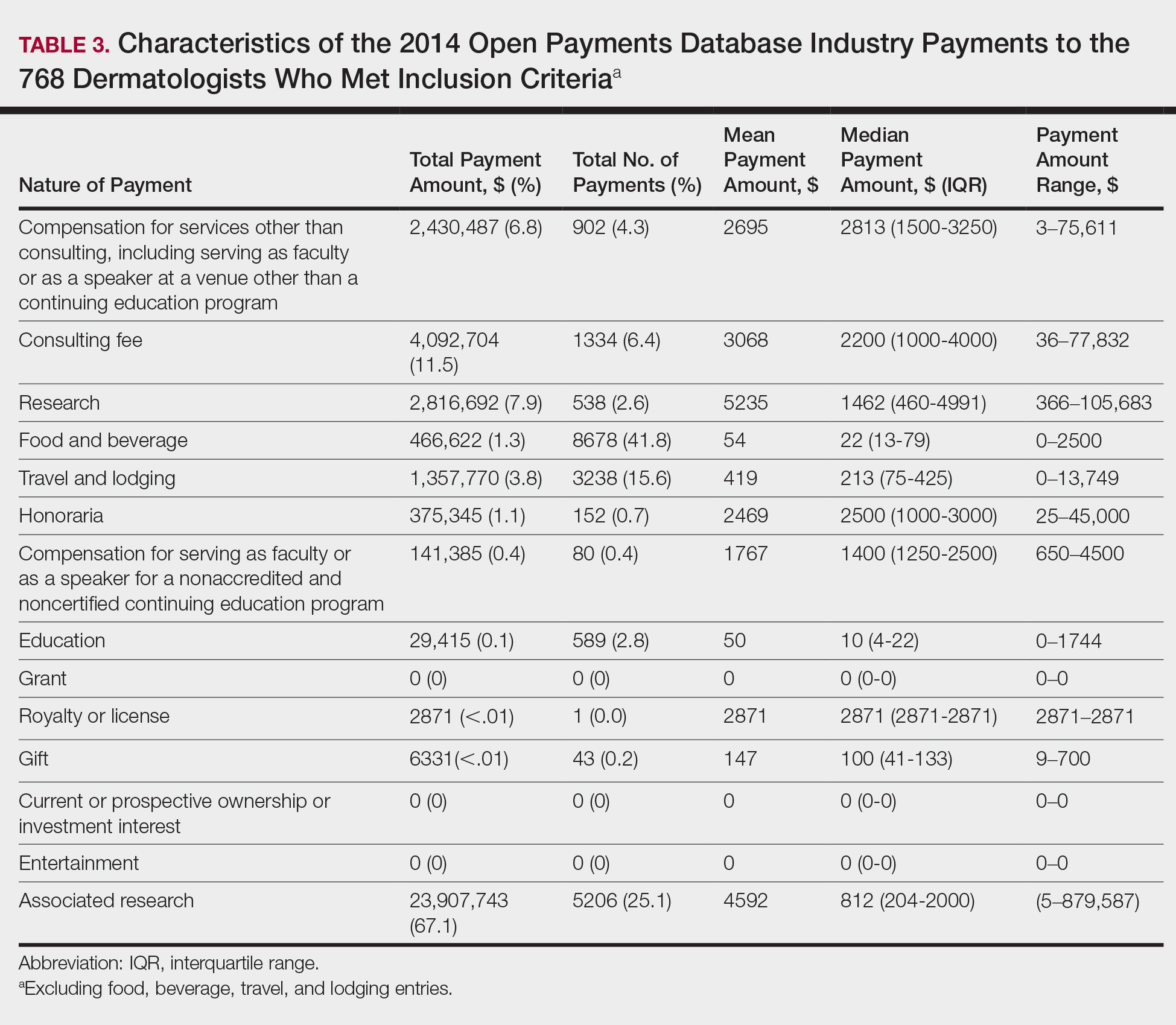

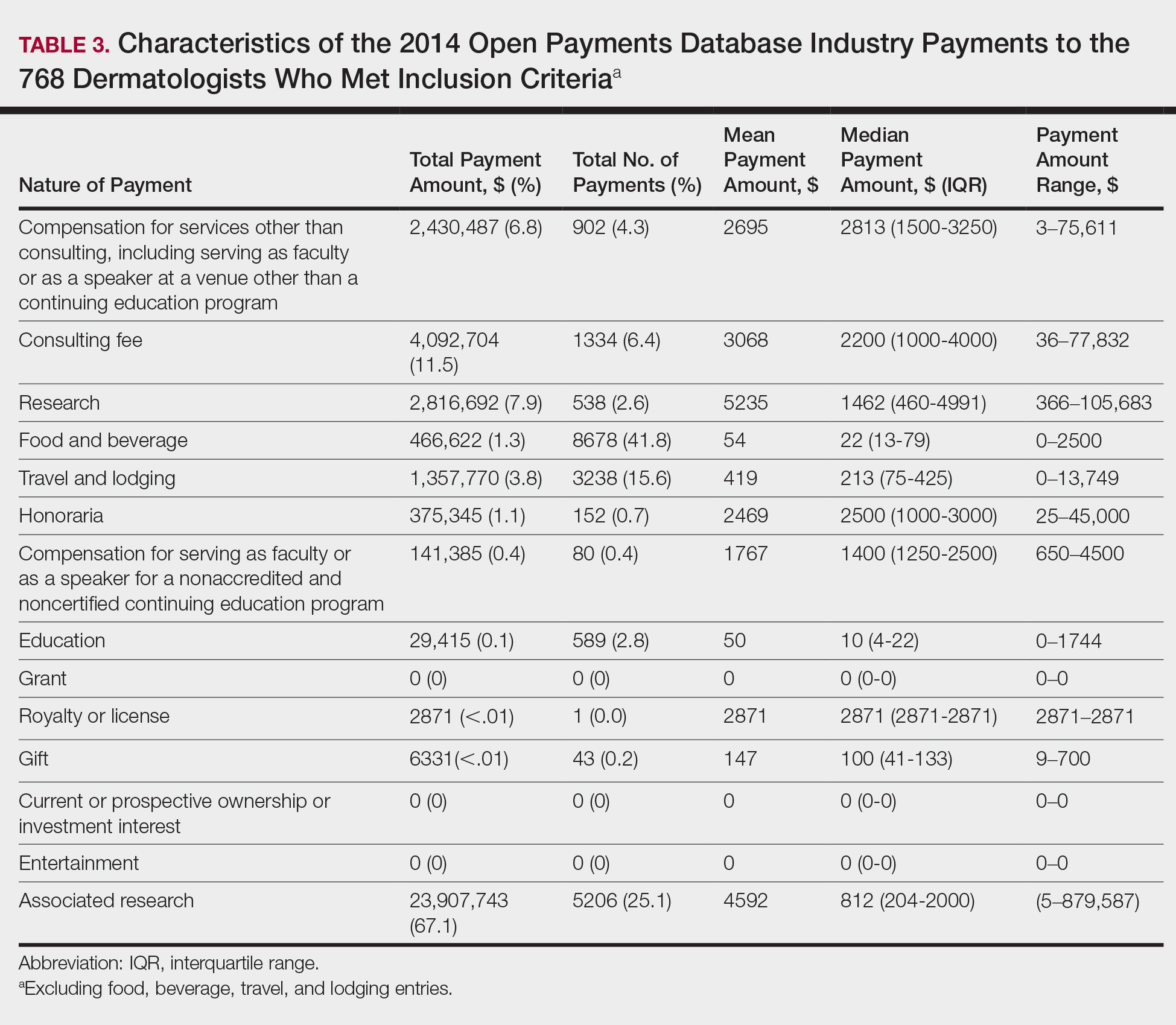

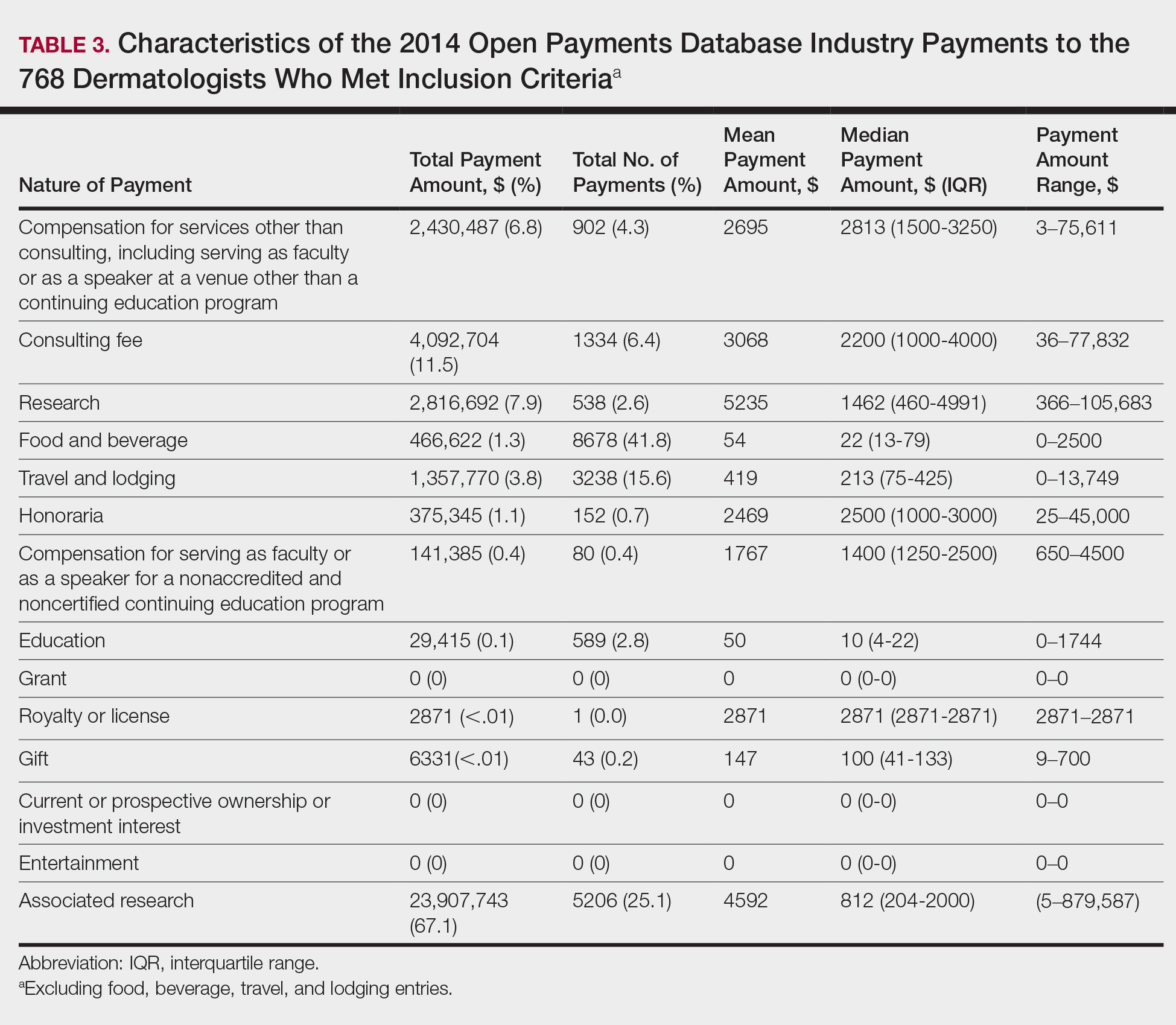

In 2014, there were a total of 20,761 industry payments totaling $35,627,365 for general, research, and associated research payments in the OP database related to the dermatologists who met inclusion criteria. There were 8678 payments totaling $466,622 for food and beverage and 3238 payments totaling $1,357,770 for travel and lodging. After excluding payments for f/b/t/l, there were 8845 payments totaling $33,802,973, with highest percentages of payment amounts for associated research (67.1%), consulting fees (11.5%), research (7.9%), and speaker fees (7.2%)(Table 3). For presenters with industry payments, the range of disbursements excluding f/b/t/l was $6.52 to $1,933,705, with a mean (standard deviation) of $107,997 ($249,941), a median of $18,247, and an interquartile range of $3422 to $97,375 (data not shown).

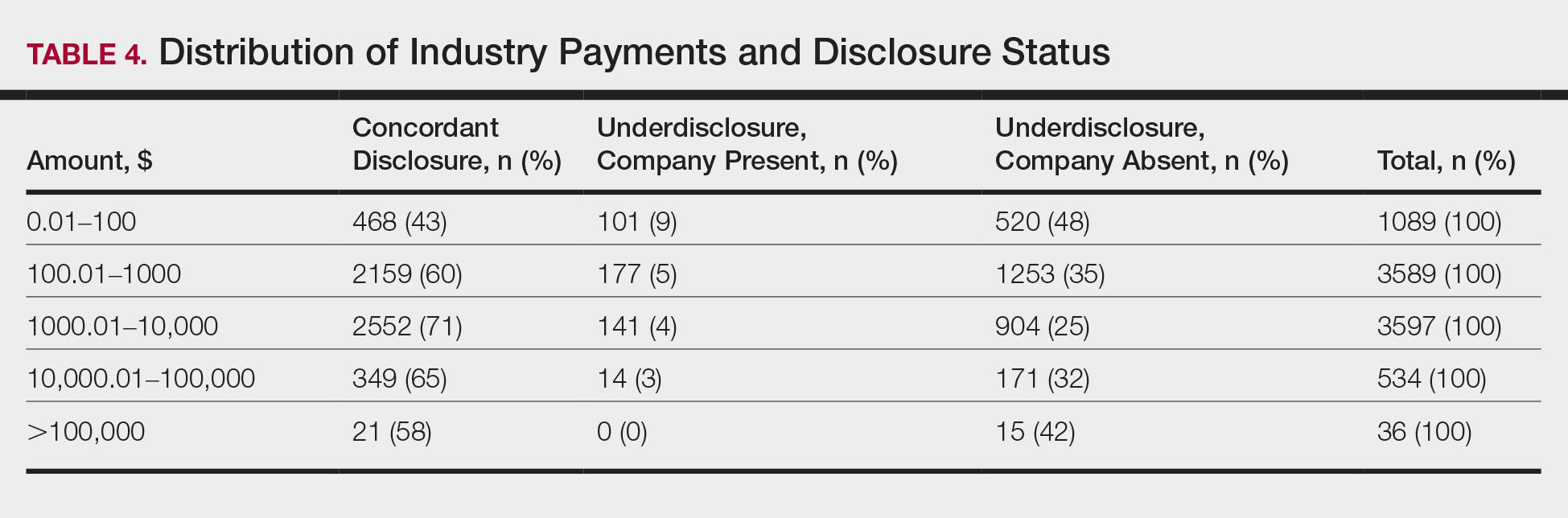

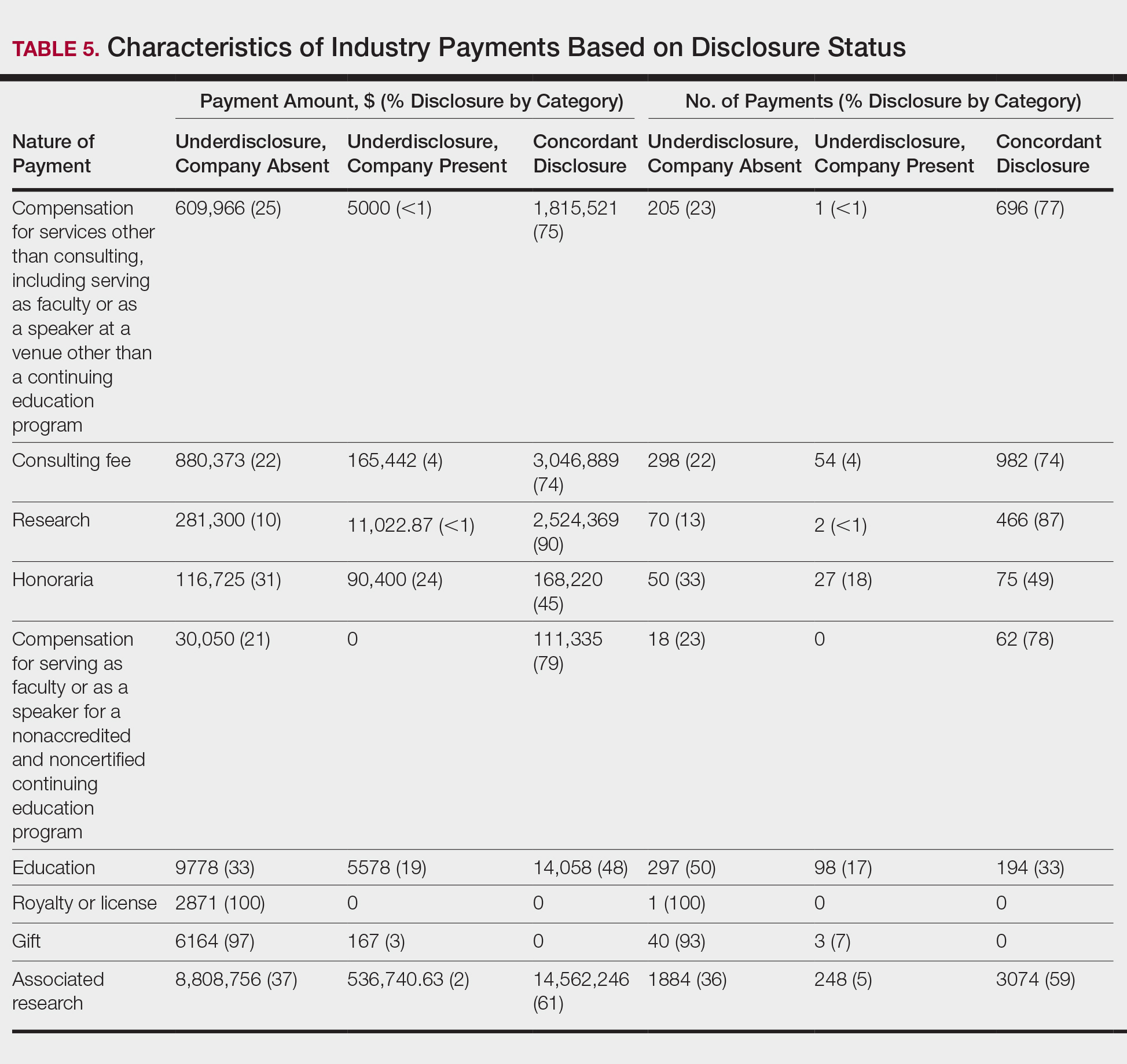

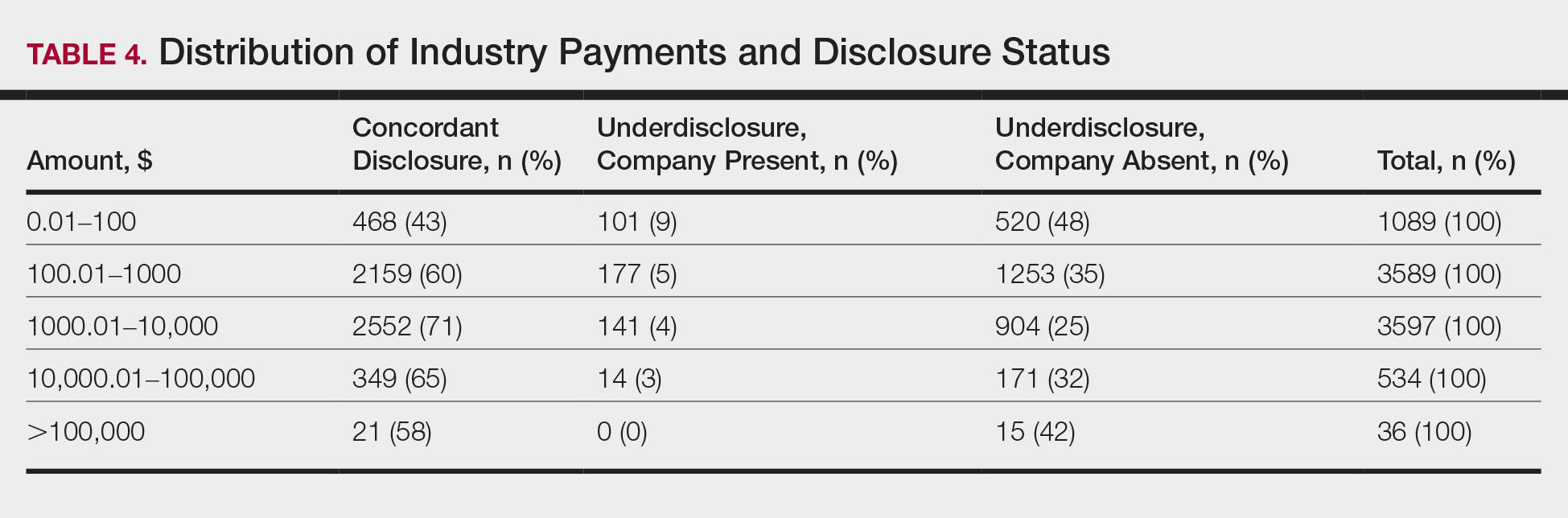

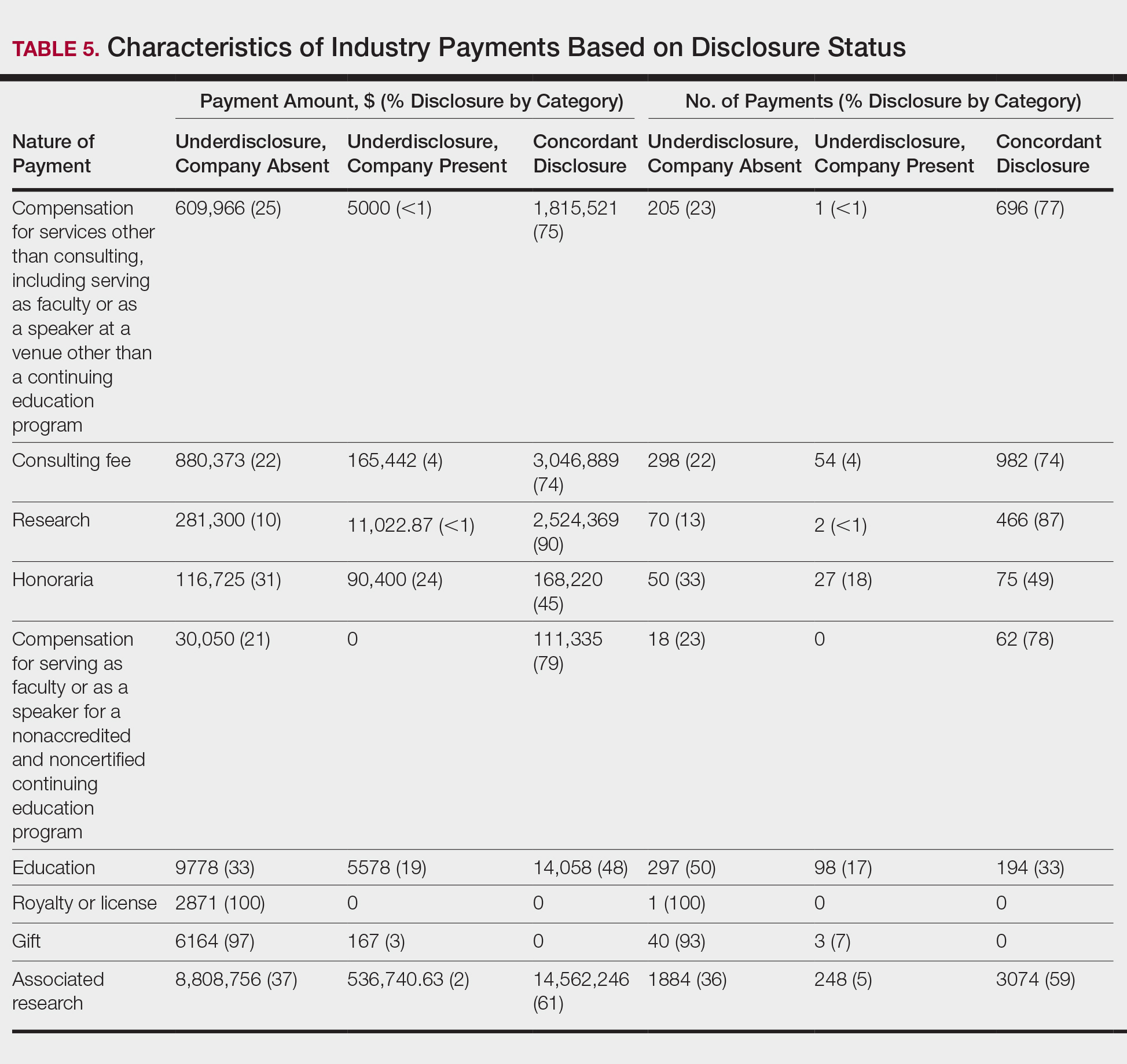

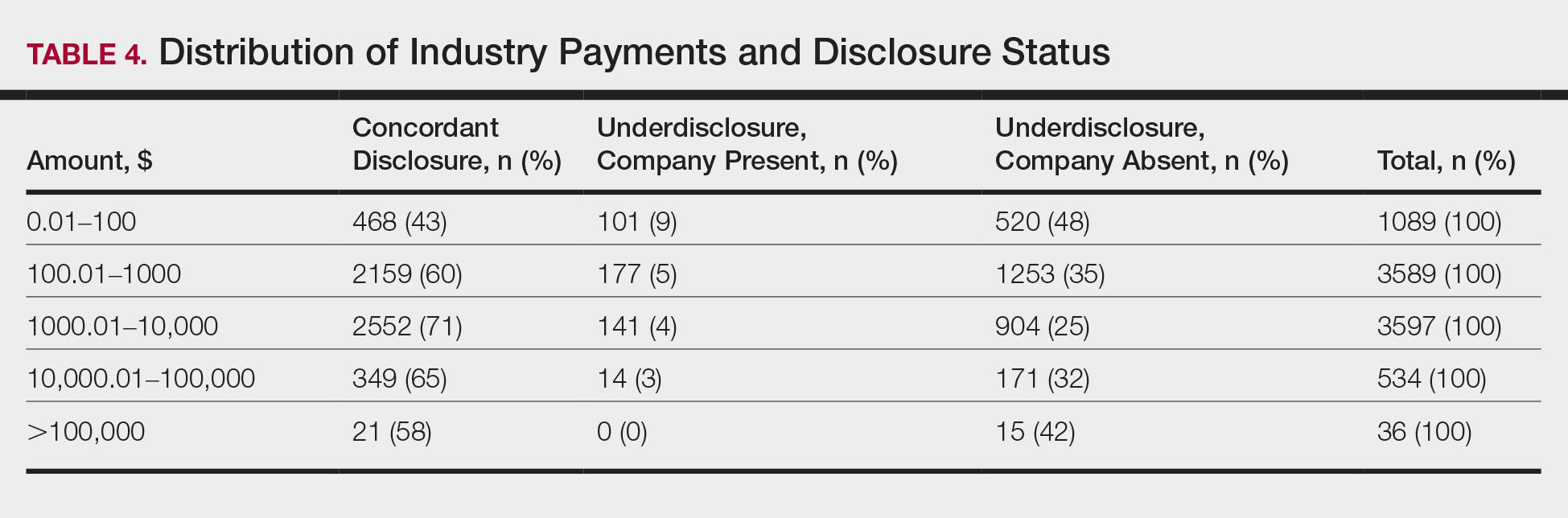

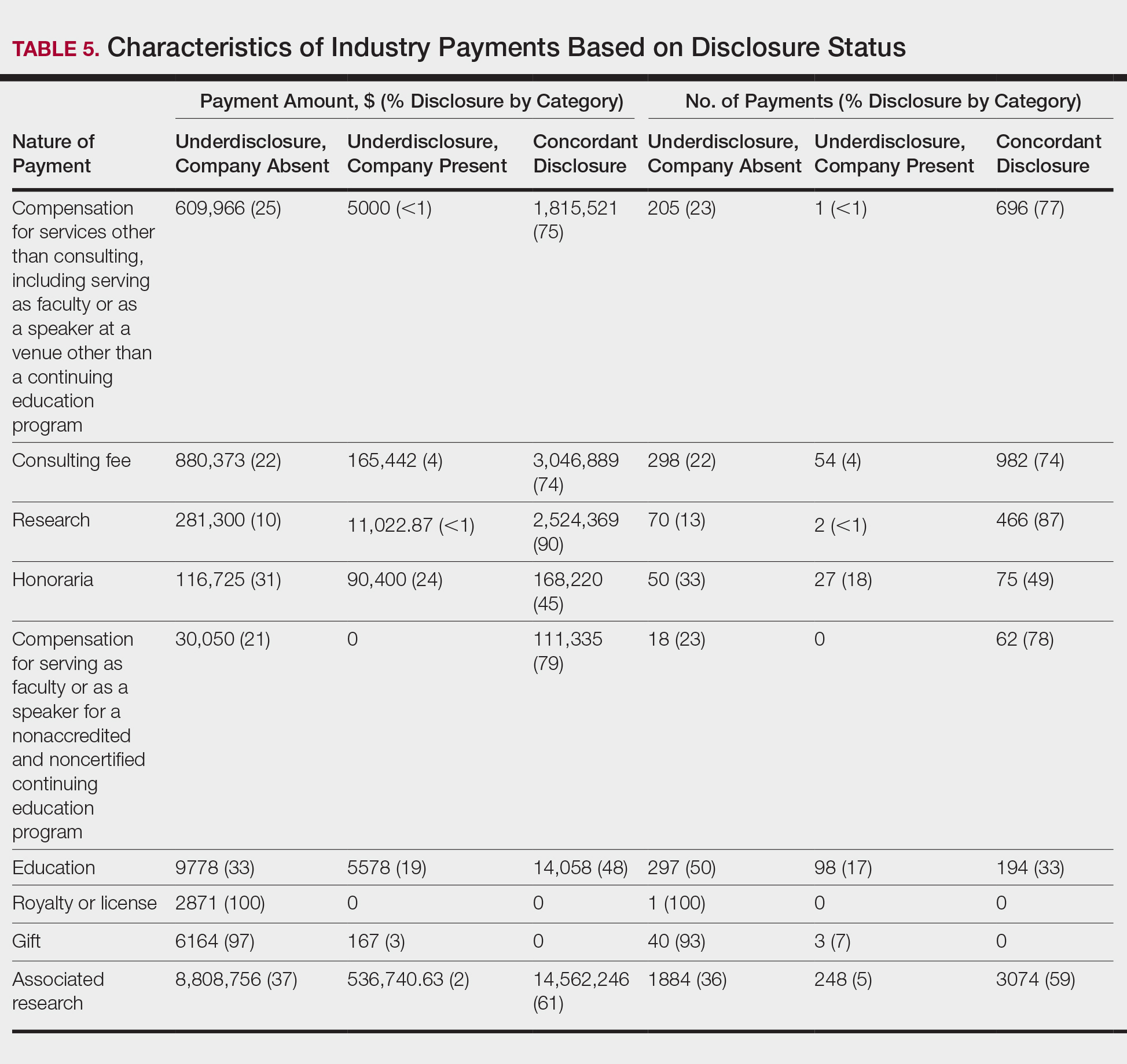

In assessing interaction-level concordance, 63% of all payment amounts in OP were classified as concordant disclosures. Regarding the number of OP payments, 27% were concordant disclosures, 34% were underdisclosures due to f/b/t/l payments, and 39% were underdisclosures due to non–f/b/t/l payments. When f/b/t/l payment entries in OP were excluded, the status of concordant disclosure for the amount and number of OP payments increased to 66% ($22,242,638) and 63% (5549), respectively. The percentage of payment entries with concordant disclosure status ranged from 43% to 71% depending on the payment amount. Payment entries at both ends of the spectrum had the lowest concordant disclosure rates, with 43% for payment entries between $0.01 and $100 and 58% for entries greater than $100,000 (Table 4). The concordance status also differed by the type of interactions. None of the OP payments for gift and royalty or license were disclosed in the AADMP, as there were no suitable corresponding categories. The proportion of payments with concordant disclosure for honoraria (45%), education (48%), and associated research (61%) was lower than the proportion of payments with concordant disclosure for research (90%), speaker fees (75%–79%), and consulting fees (74%)(Table 5).

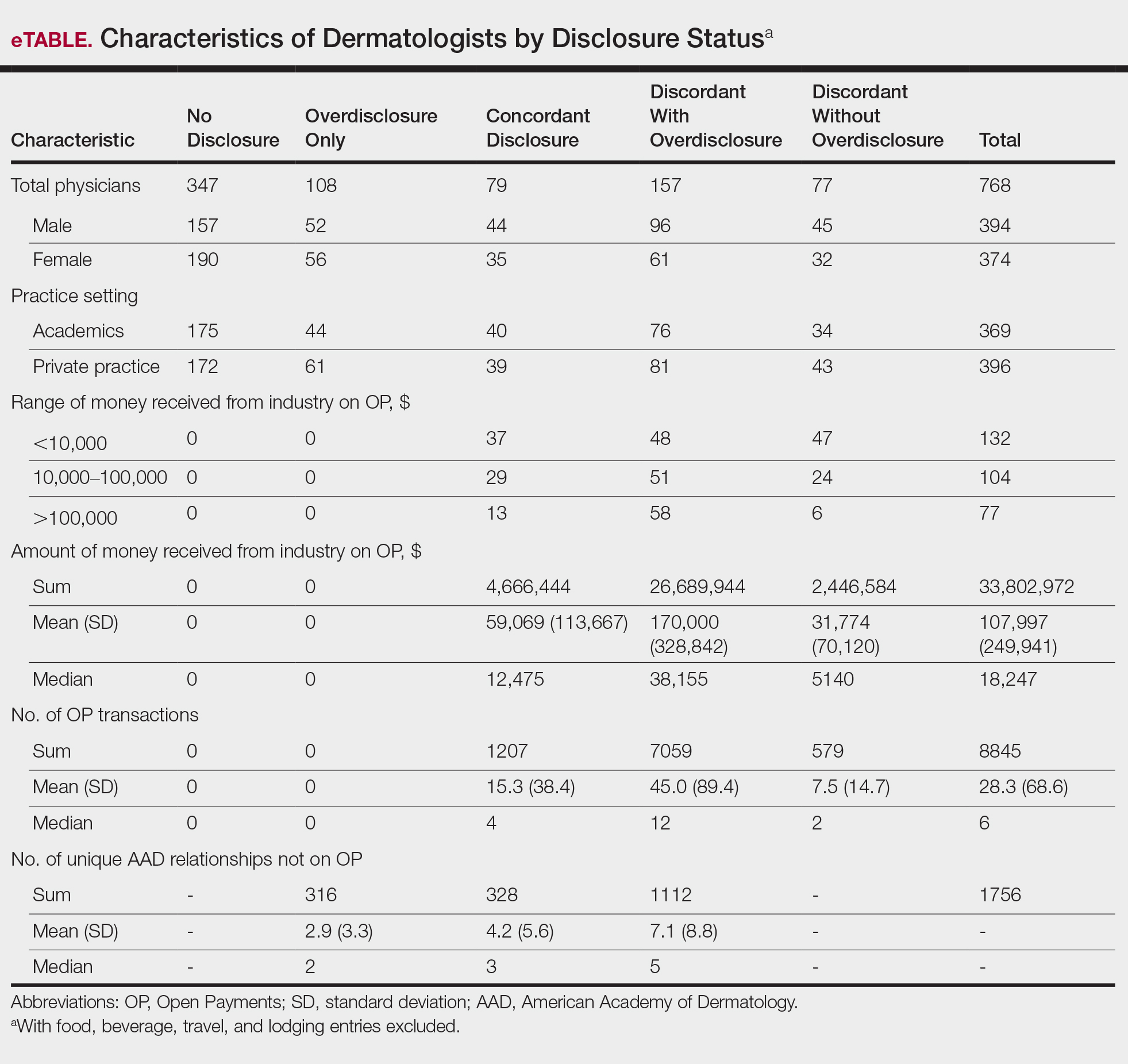

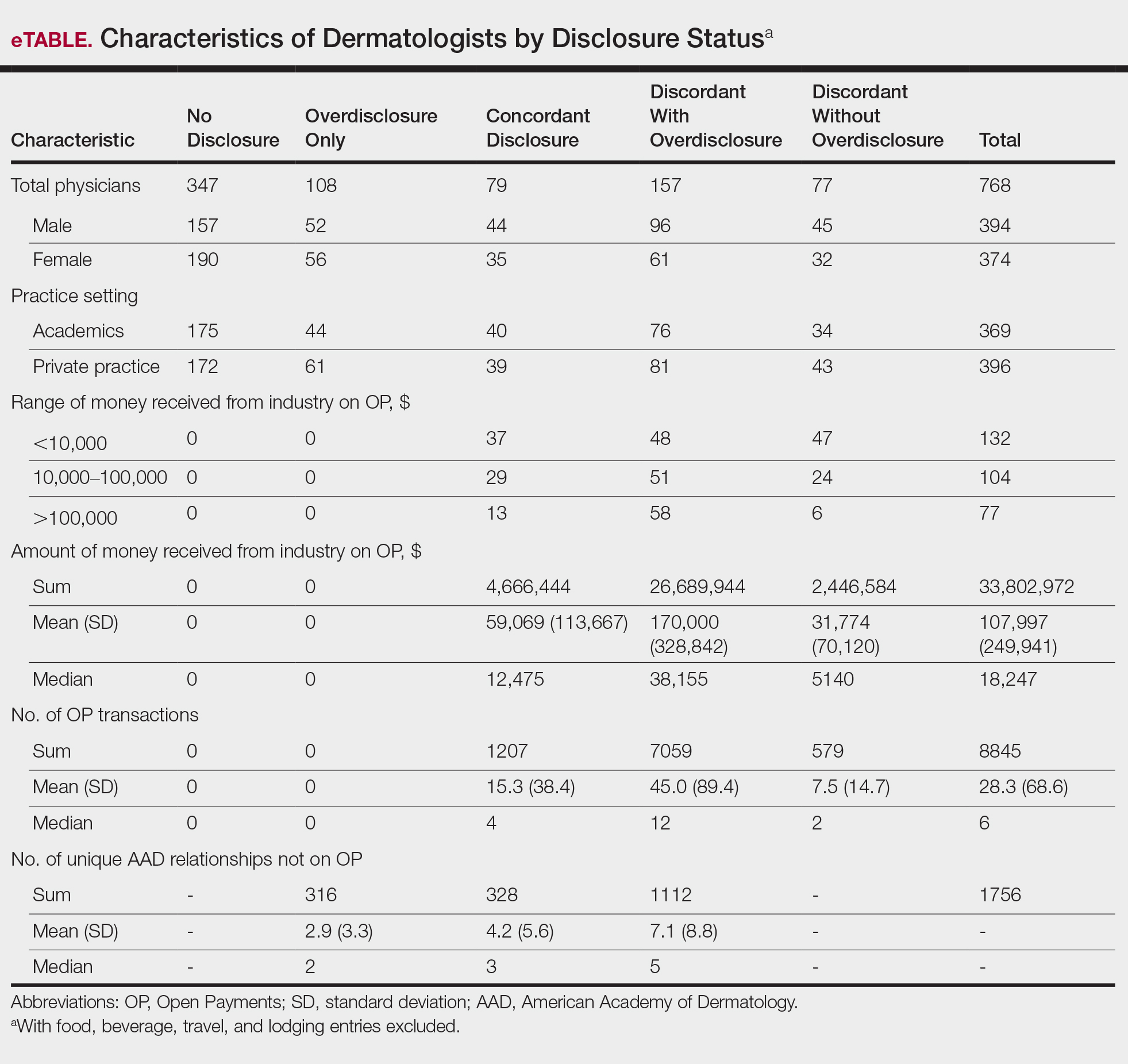

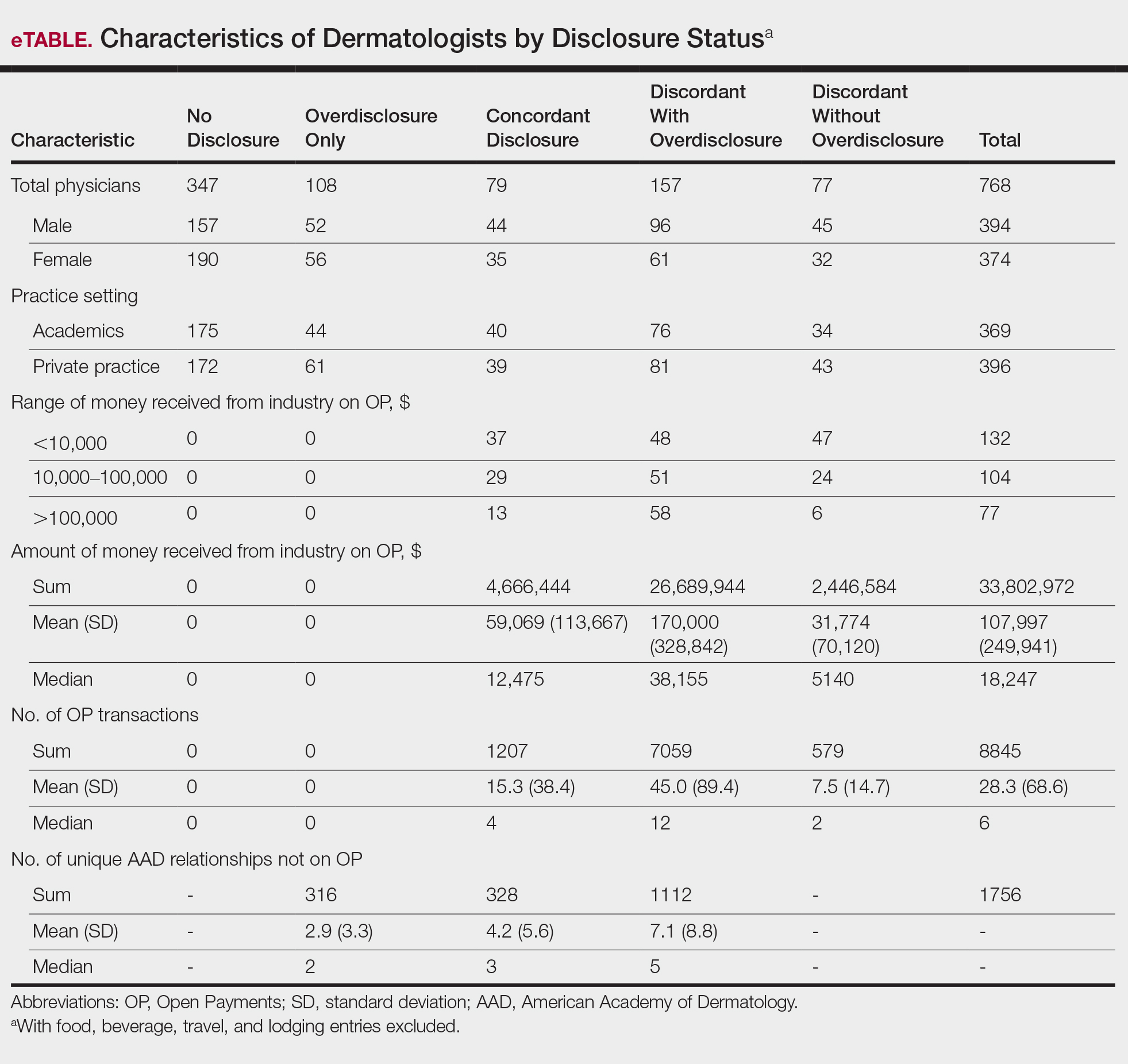

In assessing dermatologist-level concordance including all OP entries, the number of dermatologists with no disclosure, overdisclosure only, concordant disclosure, discordant with overdisclosure, and discordant without overdisclosure statuses were 234 (30%), 70 (9%), 9 (1%), 251 (33%), and 204 (27%), respectively. When f/b/t/l entries were excluded, those figures changed to 347 (45%), 108 (14%), 79 (10%), 157 (20%), and 77 (10%), respectively. The characteristics of these dermatologists and their associated industry interactions by disclosure status are shown in the eTable. Dermatologists in the discordant with overdisclosure group had the highest median number and amount of OP payments, followed by those in the concordant disclosure and discordant without overdisclosure groups. Additionally, discordant with overdisclosure dermatologists also had the highest median and mean number of unique industry interactions not on OP, followed by those in the overdisclosure only and no disclosure groups. Academic and private practice settings did not impact dermatologists’ disclosure status. The percentage of female and male dermatologists in the discordant group was 25% and 36%, respectively.

Dermatologists reported a total of 1756 unique industry relationships in the AADMP that were not found on OP. Of these, 1440 (82%) relationships were from 236 dermatologists who had industry payments on OP. The remaining 316 relationships were from 108 dermatologists who had no payments on OP. Although 114 companies reported payments to dermatologists on OP, dermatologists in the AADMP reported interactions with an additional 430 companies.

Comment

In this study, we demonstrated discordance between dermatologist self-reported financial interactions in the AADMP compared with those reported by industry via OP. After excluding f/b/t/l entries, approximately two-thirds of the total amount and number of payments in OP were disclosed, while 31% of dermatologists had discordant disclosure status.

Prior investigations in other medical fields showed high discrepancy rates between industry-reported and physician-reported relationships ranging from 23% to 62%, with studies utilizing various methodologies.6-9,11,12,14,15 Only a few studies have utilized the OP database.8,12,15 Thompson et al12 compared OP payment data with physician financial disclosure at an annual gynecology scientific meeting and found although 209 of 335 (62%) physicians had interactions listed in the OP database, only 24 (7%) listed at least 1 company in the meeting financial disclosure section. Of these 24 physicians, only 5 (21%) accurately disclosed financial relationships with all of the companies listed in OP. The investigators found 129 (38.5%) physicians and 33.7% of the $1.99 million OP payments had concordant disclosure status. When they excluded physicians who received less than $100, 53% of individuals had concordant disclosure.12 Hannon et al8 reported on inconsistencies between disclosures in the OP database and the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons Annual Meeting and found 259 (23%) of 1113 physicians meeting inclusion criteria had financial interactions listed in the OP database that were not reported in the meeting disclosures. Yee et al15 also utilized the OP database and compared it with author disclosures in 3 major ophthalmology journals.Of 670 authors, 367 (54.8%) had complete concordance, with 68 (10.1%) more reporting additional overdisclosures, leading to a discordant with underdisclosure rate of 35.1%. Additionally, $1.46 million (44.6%) of the $3.27 million OP payments had concordant disclosure status.15 Other studies compared individual companies’ online reports of physician payments with physician self-disclosures in annual meeting programs, clinical guidelines, and peer-reviewed publications.6,7,9,11,14

Our study demonstrated variation in disclosure status. Compared with other groups, dermatologists in the discordant with overdisclosure group on average had more interactions with and received higher payments from industry, which is consistent with studies in the orthopedic surgery literature.8,9 Male dermatologists had 11% more discordant disclosures than their female counterparts, which may be influenced by men having more industry interactions than women.3 Although small industry payments possessed the lowest concordant rate in our study, which has been observed,12 payments greater than $100,000 had the second-lowest concordance rate at 58%, which may be skewed by the small sample size. Rates of concordant disclosure differed among types of interactions, such as between research and associated research payments. This particular difference may be attributed to the incorrect listing of dermatologists as principal investigators or reduced awareness of payments, as associated research payments were made to the institution and not the individual.

Reasons for discrepancies between industry-reported and dermatologist-reported disclosures may include reporting time differences, lack of physician awareness of OP, industry reporting inaccuracies, dearth of contextual information associated with individual payment entries, and misunderstandings. Prior research demonstrated that the most common reasons for physician nondisclosure included misunderstanding disclosure requirements, unintentional omission of payment, and a lack of relationship between the industry payment and presentation topic.9,12 These factors likely contributed to the disclosure inconsistencies in our study. Similarly high rates of inconsistencies across different specialties suggest systemic concerns.

We found a substantial number of dermatologist-industry interactions listed in the AADMP that were not captured by OP, with 108 dermatologists (35%) having overdisclosures even when excluding f/b/t/l entries. The number of companies in these overdisclosures approximated 4 times the number of companies on OP. Other studies have also observed physician-industry interactions not displayed on OP.8,12,15 Because the Sunshine Act requires reporting only by certain companies, interactions surrounding products such as over-the-counter merchandise, cosmetics, lasers, novel devices, and new medications are generally not included. Further, OP may not capture nonmonetary industry relationships.

There were several limitations to this study. The most notable limitation was the differences in the categorizations of industry relationships by OP and the AADMP. These differences can overemphasize some types of interactions at the expense of other types, such as f/b/t/l. As such, analyses were repeated after excluding f/b/t/l. Another limitation was the inexact overlap of time frames for OP and the AADMP, which may have led to discrepancies. However, we used the best available data and expect the vast majority of interactions to have occurred by the AAD disclosure deadline. It is possible that the presenters may have had a more updated conflict-of-interest disclosure slide at the time of the meeting presentation. The most important limitation was that we were unable to determine whether discrepancies resulted from underreporting by dermatologists or inaccurate reporting by industry. It was unlikely that OP or the AADMP alone completely represented all dermatologist-industry financial relationships.

Conclusion

With a growing emphasis on physician-industry transparency, we identified rates of differences in dermatology consistent with those in other medical fields when comparing the publicly available OP database with disclosures at national conferences. Although the differences in the categorization and requirements for disclosure between the OP database and the AADMP may account for some of the discordance, dermatologists should be aware of potentially negative public perceptions regarding the transparency and prevalence of physician-industry interactions.

Acknowledgment

The first two authors contributed equally to this research/article

- Campbell EG, Gruen RL, Mountford J, et al. A national survey of physician-industry relationships. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1742-1750.

- Marshall DC, Jackson ME, Hattangadi-Gluth JA. Disclosure of industry payments to physicians: an epidemiologic analysis of early data from the open payments program. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:84-96.

- Feng H, Wu P, Leger M. Exploring the industry-dermatologist financial relationship: insight from the open payment data. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1307-1313.

- Kirschner NM, Sulmasy LS, Kesselheim AS. Health policy basics: the physician payment Sunshine Act and the open payments program. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:519-521.

- Search Open Payment. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov. Accessed October 21, 2019.

- Buerba RA, Fu MC, Grauer JN. Discrepancies in spine surgeon conflict of interest disclosures between a national meeting and physician payment listings on device manufacturer web sites. Spine J. 2013;13:1780-1788.

- Chimonas S, Frosch Z, Rothman DJ. From disclosure to transparency: the use of company payment data. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:81-86.

- Hannon CP, Chalmers PN, Carpiniello MF, et al. Inconsistencies between physician-reported disclosures at the AAOS annual meeting and industry-reported financial disclosures in the open payments database. J Bone Joint Surg. 2016;98:E90.

- Okike K, Kocher MS, Wei EX, et al. Accuracy of conflict-of-interest disclosures reported by physicians. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1466-1474.

- Ramm O, Brubaker L. Conflicts-of-interest disclosures at the 2010 AUGS Scientific Meeting. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2012;18:79-81.

- Tanzer D, Smith K, Tanzer M. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons disclosure policy fails to accurately inform its members of potential conflicts of interest. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2015;44:E207-E210.

- Thompson JC, Volpe KA, Bridgewater LK, et al. Sunshine Act: shedding light on inaccurate disclosures at a gynecologic annual meeting. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:661.

- Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. American Academy of Dermatology and AAD Association Web site. https://aad.org/Forms/Policies/Uploads/AR/

AR%20Disclosure%20of%20Potential%20Conflicts%

20of%20Interest-2.pdf. Accessed October 21, 2019. - Hockenberry JM, Weigel P, Auerbach A, et al. Financial payments by orthopedic device makers to orthopedic surgeons. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1759-1765.

- Yee C, Greenberg PB, Margo CE, et al. Financial disclosures in academic publications and the Sunshine Act: a concordance dtudy. Br J Med Med Res. 2015;10:1-6.

Interactions between industry and physicians, including dermatologists, are widely prevalent.1-3 Proper reporting of industry relationships is essential for transparency, objectivity, and management of potential biases and conflicts of interest. There has been increasing public scrutiny regarding these interactions.

The Physician Payments Sunshine Act established Open Payments (OP), a publicly available database that collects and displays industry-reported physician-industry interactions.4,5 For the medical community and public, the OP database may be used to assess transparency by comparing the data with physician self-disclosures. There is a paucity of studies in the literature examining the concordance of industry-reported disclosures and physician self-reported data, with even fewer studies utilizing OP as a source of industry disclosures, and none exists for dermatology.6-12 It also is not clear to what extent the OP database captures all possible dermatologist-industry interactions, as the Sunshine Act only mandates reporting by applicable US-based manufacturers and group purchasing organizations that produce or purchase drugs or devices that require a prescription and are reimbursable by a government-run health care program.5 As a result, certain companies, such as cosmeceuticals, may not be represented.

In this study we aimed to evaluate the concordance of dermatologist self-disclosure of industry relationships and those reported on OP. Specifically, we focused on interactions disclosed by presenters at the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) 73rd Annual Meeting in San Francisco, California (March 20–24, 2015), and those by industry in the 2014 OP database.

Methods

In this retrospective cohort study, we compared publicly available data from the OP database to presenter disclosures found in the publicly available AAD 73rd Annual Meeting program (AADMP). The AAD required speakers to disclose financial relationships with industry within the 12 months preceding the presentation, as outlined in the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education guidelines.13 All AAD presenters who were dermatologists practicing in the United States were included in the analysis, whereas residents, fellows, nonphysicians, nondermatologist physicians, and international dermatologists were excluded.

We examined general, research, and associated research payments to specific dermatologists using the 2014 OP data, which contained industry payments made between January 1 and December 31, 2014. Open Payments defined research payments as direct payment to the physician for different types of research activities and associated research payments as indirect payments made to a research institution or entity where the physician was named the principal investigator.5 We chose the 2014 database because it most closely matched the period of required disclosures defined by the AAD for the 2015 meeting. Our review of the OP data occurred after the June 2016 update and thus included the most accurate and up-to-date financial interactions.

We conducted our analysis in 2 major steps. First, we determined whether each industry interaction reported in the OP database was present in the AADMP, which provided an assessment of interaction-level concordance. Second, we determined whether all the industry interactions for any given dermatologist listed in the OP also were present in AADMP, which provided an assessment of dermatologist-level concordance.

First, to establish interaction-level concordance for each industry interaction, the company name and the type of interaction (eg, consultant, speaker, investigator) listed in the AADMP were compared with the data in OP to verify a match. Each interaction was assigned into one of the categories of concordant disclosure (a match of both the company name and type of interaction details in OP and the AADMP), overdisclosure (the presence of an AADMP interaction not found in OP, such as an additional type of interaction or company), or underdisclosure (a company name or type of interaction found in OP but not reported in the AADMP). For underdisclosure, we further classified into company present or company absent based on whether the dermatologist disclosed any relationship with a particular company in the AADMP. We considered the type of interaction to be matching if they were identical or similar in nature (eg, consulting in OP and advisory board in the AADMP), as the types of interactions are reported differently in OP and the AADMP. Otherwise, if they were not similar enough (eg, education in OP and stockholder in the AADMP), it was classified as underdisclosure. Some types of interactions reported in OP were not available on the AAD disclosure form. For example, food and beverage as well as travel and lodging were types of interactions in OP that did not exist in the AADMP. These 2 types of interactions comprised a large majority of OP payment entries but only accounted for a small percentage of the payment amount. Analysis was performed both including and excluding interactions for food, beverage, travel, and lodging (f/b/t/l) to best account for differences in interaction categories between OP and the AADMP.

Second, each dermatologist was assigned to an overall disclosure category of dermatologist-level concordance based on the status for all his/her interactions. Categories included no disclosure (no industry interactions in OP and the AADMP), concordant (all industry interactions reported in OP and the AADMP match), overdisclosure only (no industry interactions on OP but self-reported interactions present in the AADMP), and discordant (not all OP interactions were disclosed in the AADMP). The discordant category was further divided into with overdisclosure and without overdisclosure, depending on the presence or absence of industry relationships listed in the AADMP but not in OP, respectively.

To ensure uniformity, one individual (A.F.S.) reviewed and collected the data from OP and the AADMP. Information on gender and academic affiliation of study participants was obtained from information listed in the AADMP and Google searches. Data management was performed with Microsoft Excel software (Microsoft Excel 2010, Version 14.0, Microsoft Corporation). The New York University School of Medicine’s (New York, New York) institutional review board exempted this study.

Results

Of the 938 presenters listed in the AADMP, 768 individuals met the inclusion criteria. The most commonly cited type of relationship with industry listed in the AADMP was serving as an investigator, consultant, or advisory board member, comprising 34%, 26%, and 18%, respectively (Table 1). The forms of payment most frequently reported in the AADMP were honoraria and grants/research funding, comprising 49% and 25%, respectively (Table 2).

In 2014, there were a total of 20,761 industry payments totaling $35,627,365 for general, research, and associated research payments in the OP database related to the dermatologists who met inclusion criteria. There were 8678 payments totaling $466,622 for food and beverage and 3238 payments totaling $1,357,770 for travel and lodging. After excluding payments for f/b/t/l, there were 8845 payments totaling $33,802,973, with highest percentages of payment amounts for associated research (67.1%), consulting fees (11.5%), research (7.9%), and speaker fees (7.2%)(Table 3). For presenters with industry payments, the range of disbursements excluding f/b/t/l was $6.52 to $1,933,705, with a mean (standard deviation) of $107,997 ($249,941), a median of $18,247, and an interquartile range of $3422 to $97,375 (data not shown).

In assessing interaction-level concordance, 63% of all payment amounts in OP were classified as concordant disclosures. Regarding the number of OP payments, 27% were concordant disclosures, 34% were underdisclosures due to f/b/t/l payments, and 39% were underdisclosures due to non–f/b/t/l payments. When f/b/t/l payment entries in OP were excluded, the status of concordant disclosure for the amount and number of OP payments increased to 66% ($22,242,638) and 63% (5549), respectively. The percentage of payment entries with concordant disclosure status ranged from 43% to 71% depending on the payment amount. Payment entries at both ends of the spectrum had the lowest concordant disclosure rates, with 43% for payment entries between $0.01 and $100 and 58% for entries greater than $100,000 (Table 4). The concordance status also differed by the type of interactions. None of the OP payments for gift and royalty or license were disclosed in the AADMP, as there were no suitable corresponding categories. The proportion of payments with concordant disclosure for honoraria (45%), education (48%), and associated research (61%) was lower than the proportion of payments with concordant disclosure for research (90%), speaker fees (75%–79%), and consulting fees (74%)(Table 5).

In assessing dermatologist-level concordance including all OP entries, the number of dermatologists with no disclosure, overdisclosure only, concordant disclosure, discordant with overdisclosure, and discordant without overdisclosure statuses were 234 (30%), 70 (9%), 9 (1%), 251 (33%), and 204 (27%), respectively. When f/b/t/l entries were excluded, those figures changed to 347 (45%), 108 (14%), 79 (10%), 157 (20%), and 77 (10%), respectively. The characteristics of these dermatologists and their associated industry interactions by disclosure status are shown in the eTable. Dermatologists in the discordant with overdisclosure group had the highest median number and amount of OP payments, followed by those in the concordant disclosure and discordant without overdisclosure groups. Additionally, discordant with overdisclosure dermatologists also had the highest median and mean number of unique industry interactions not on OP, followed by those in the overdisclosure only and no disclosure groups. Academic and private practice settings did not impact dermatologists’ disclosure status. The percentage of female and male dermatologists in the discordant group was 25% and 36%, respectively.

Dermatologists reported a total of 1756 unique industry relationships in the AADMP that were not found on OP. Of these, 1440 (82%) relationships were from 236 dermatologists who had industry payments on OP. The remaining 316 relationships were from 108 dermatologists who had no payments on OP. Although 114 companies reported payments to dermatologists on OP, dermatologists in the AADMP reported interactions with an additional 430 companies.

Comment

In this study, we demonstrated discordance between dermatologist self-reported financial interactions in the AADMP compared with those reported by industry via OP. After excluding f/b/t/l entries, approximately two-thirds of the total amount and number of payments in OP were disclosed, while 31% of dermatologists had discordant disclosure status.

Prior investigations in other medical fields showed high discrepancy rates between industry-reported and physician-reported relationships ranging from 23% to 62%, with studies utilizing various methodologies.6-9,11,12,14,15 Only a few studies have utilized the OP database.8,12,15 Thompson et al12 compared OP payment data with physician financial disclosure at an annual gynecology scientific meeting and found although 209 of 335 (62%) physicians had interactions listed in the OP database, only 24 (7%) listed at least 1 company in the meeting financial disclosure section. Of these 24 physicians, only 5 (21%) accurately disclosed financial relationships with all of the companies listed in OP. The investigators found 129 (38.5%) physicians and 33.7% of the $1.99 million OP payments had concordant disclosure status. When they excluded physicians who received less than $100, 53% of individuals had concordant disclosure.12 Hannon et al8 reported on inconsistencies between disclosures in the OP database and the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons Annual Meeting and found 259 (23%) of 1113 physicians meeting inclusion criteria had financial interactions listed in the OP database that were not reported in the meeting disclosures. Yee et al15 also utilized the OP database and compared it with author disclosures in 3 major ophthalmology journals.Of 670 authors, 367 (54.8%) had complete concordance, with 68 (10.1%) more reporting additional overdisclosures, leading to a discordant with underdisclosure rate of 35.1%. Additionally, $1.46 million (44.6%) of the $3.27 million OP payments had concordant disclosure status.15 Other studies compared individual companies’ online reports of physician payments with physician self-disclosures in annual meeting programs, clinical guidelines, and peer-reviewed publications.6,7,9,11,14

Our study demonstrated variation in disclosure status. Compared with other groups, dermatologists in the discordant with overdisclosure group on average had more interactions with and received higher payments from industry, which is consistent with studies in the orthopedic surgery literature.8,9 Male dermatologists had 11% more discordant disclosures than their female counterparts, which may be influenced by men having more industry interactions than women.3 Although small industry payments possessed the lowest concordant rate in our study, which has been observed,12 payments greater than $100,000 had the second-lowest concordance rate at 58%, which may be skewed by the small sample size. Rates of concordant disclosure differed among types of interactions, such as between research and associated research payments. This particular difference may be attributed to the incorrect listing of dermatologists as principal investigators or reduced awareness of payments, as associated research payments were made to the institution and not the individual.

Reasons for discrepancies between industry-reported and dermatologist-reported disclosures may include reporting time differences, lack of physician awareness of OP, industry reporting inaccuracies, dearth of contextual information associated with individual payment entries, and misunderstandings. Prior research demonstrated that the most common reasons for physician nondisclosure included misunderstanding disclosure requirements, unintentional omission of payment, and a lack of relationship between the industry payment and presentation topic.9,12 These factors likely contributed to the disclosure inconsistencies in our study. Similarly high rates of inconsistencies across different specialties suggest systemic concerns.

We found a substantial number of dermatologist-industry interactions listed in the AADMP that were not captured by OP, with 108 dermatologists (35%) having overdisclosures even when excluding f/b/t/l entries. The number of companies in these overdisclosures approximated 4 times the number of companies on OP. Other studies have also observed physician-industry interactions not displayed on OP.8,12,15 Because the Sunshine Act requires reporting only by certain companies, interactions surrounding products such as over-the-counter merchandise, cosmetics, lasers, novel devices, and new medications are generally not included. Further, OP may not capture nonmonetary industry relationships.

There were several limitations to this study. The most notable limitation was the differences in the categorizations of industry relationships by OP and the AADMP. These differences can overemphasize some types of interactions at the expense of other types, such as f/b/t/l. As such, analyses were repeated after excluding f/b/t/l. Another limitation was the inexact overlap of time frames for OP and the AADMP, which may have led to discrepancies. However, we used the best available data and expect the vast majority of interactions to have occurred by the AAD disclosure deadline. It is possible that the presenters may have had a more updated conflict-of-interest disclosure slide at the time of the meeting presentation. The most important limitation was that we were unable to determine whether discrepancies resulted from underreporting by dermatologists or inaccurate reporting by industry. It was unlikely that OP or the AADMP alone completely represented all dermatologist-industry financial relationships.

Conclusion

With a growing emphasis on physician-industry transparency, we identified rates of differences in dermatology consistent with those in other medical fields when comparing the publicly available OP database with disclosures at national conferences. Although the differences in the categorization and requirements for disclosure between the OP database and the AADMP may account for some of the discordance, dermatologists should be aware of potentially negative public perceptions regarding the transparency and prevalence of physician-industry interactions.

Acknowledgment

The first two authors contributed equally to this research/article

Interactions between industry and physicians, including dermatologists, are widely prevalent.1-3 Proper reporting of industry relationships is essential for transparency, objectivity, and management of potential biases and conflicts of interest. There has been increasing public scrutiny regarding these interactions.

The Physician Payments Sunshine Act established Open Payments (OP), a publicly available database that collects and displays industry-reported physician-industry interactions.4,5 For the medical community and public, the OP database may be used to assess transparency by comparing the data with physician self-disclosures. There is a paucity of studies in the literature examining the concordance of industry-reported disclosures and physician self-reported data, with even fewer studies utilizing OP as a source of industry disclosures, and none exists for dermatology.6-12 It also is not clear to what extent the OP database captures all possible dermatologist-industry interactions, as the Sunshine Act only mandates reporting by applicable US-based manufacturers and group purchasing organizations that produce or purchase drugs or devices that require a prescription and are reimbursable by a government-run health care program.5 As a result, certain companies, such as cosmeceuticals, may not be represented.

In this study we aimed to evaluate the concordance of dermatologist self-disclosure of industry relationships and those reported on OP. Specifically, we focused on interactions disclosed by presenters at the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) 73rd Annual Meeting in San Francisco, California (March 20–24, 2015), and those by industry in the 2014 OP database.

Methods

In this retrospective cohort study, we compared publicly available data from the OP database to presenter disclosures found in the publicly available AAD 73rd Annual Meeting program (AADMP). The AAD required speakers to disclose financial relationships with industry within the 12 months preceding the presentation, as outlined in the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education guidelines.13 All AAD presenters who were dermatologists practicing in the United States were included in the analysis, whereas residents, fellows, nonphysicians, nondermatologist physicians, and international dermatologists were excluded.

We examined general, research, and associated research payments to specific dermatologists using the 2014 OP data, which contained industry payments made between January 1 and December 31, 2014. Open Payments defined research payments as direct payment to the physician for different types of research activities and associated research payments as indirect payments made to a research institution or entity where the physician was named the principal investigator.5 We chose the 2014 database because it most closely matched the period of required disclosures defined by the AAD for the 2015 meeting. Our review of the OP data occurred after the June 2016 update and thus included the most accurate and up-to-date financial interactions.

We conducted our analysis in 2 major steps. First, we determined whether each industry interaction reported in the OP database was present in the AADMP, which provided an assessment of interaction-level concordance. Second, we determined whether all the industry interactions for any given dermatologist listed in the OP also were present in AADMP, which provided an assessment of dermatologist-level concordance.

First, to establish interaction-level concordance for each industry interaction, the company name and the type of interaction (eg, consultant, speaker, investigator) listed in the AADMP were compared with the data in OP to verify a match. Each interaction was assigned into one of the categories of concordant disclosure (a match of both the company name and type of interaction details in OP and the AADMP), overdisclosure (the presence of an AADMP interaction not found in OP, such as an additional type of interaction or company), or underdisclosure (a company name or type of interaction found in OP but not reported in the AADMP). For underdisclosure, we further classified into company present or company absent based on whether the dermatologist disclosed any relationship with a particular company in the AADMP. We considered the type of interaction to be matching if they were identical or similar in nature (eg, consulting in OP and advisory board in the AADMP), as the types of interactions are reported differently in OP and the AADMP. Otherwise, if they were not similar enough (eg, education in OP and stockholder in the AADMP), it was classified as underdisclosure. Some types of interactions reported in OP were not available on the AAD disclosure form. For example, food and beverage as well as travel and lodging were types of interactions in OP that did not exist in the AADMP. These 2 types of interactions comprised a large majority of OP payment entries but only accounted for a small percentage of the payment amount. Analysis was performed both including and excluding interactions for food, beverage, travel, and lodging (f/b/t/l) to best account for differences in interaction categories between OP and the AADMP.

Second, each dermatologist was assigned to an overall disclosure category of dermatologist-level concordance based on the status for all his/her interactions. Categories included no disclosure (no industry interactions in OP and the AADMP), concordant (all industry interactions reported in OP and the AADMP match), overdisclosure only (no industry interactions on OP but self-reported interactions present in the AADMP), and discordant (not all OP interactions were disclosed in the AADMP). The discordant category was further divided into with overdisclosure and without overdisclosure, depending on the presence or absence of industry relationships listed in the AADMP but not in OP, respectively.

To ensure uniformity, one individual (A.F.S.) reviewed and collected the data from OP and the AADMP. Information on gender and academic affiliation of study participants was obtained from information listed in the AADMP and Google searches. Data management was performed with Microsoft Excel software (Microsoft Excel 2010, Version 14.0, Microsoft Corporation). The New York University School of Medicine’s (New York, New York) institutional review board exempted this study.

Results

Of the 938 presenters listed in the AADMP, 768 individuals met the inclusion criteria. The most commonly cited type of relationship with industry listed in the AADMP was serving as an investigator, consultant, or advisory board member, comprising 34%, 26%, and 18%, respectively (Table 1). The forms of payment most frequently reported in the AADMP were honoraria and grants/research funding, comprising 49% and 25%, respectively (Table 2).

In 2014, there were a total of 20,761 industry payments totaling $35,627,365 for general, research, and associated research payments in the OP database related to the dermatologists who met inclusion criteria. There were 8678 payments totaling $466,622 for food and beverage and 3238 payments totaling $1,357,770 for travel and lodging. After excluding payments for f/b/t/l, there were 8845 payments totaling $33,802,973, with highest percentages of payment amounts for associated research (67.1%), consulting fees (11.5%), research (7.9%), and speaker fees (7.2%)(Table 3). For presenters with industry payments, the range of disbursements excluding f/b/t/l was $6.52 to $1,933,705, with a mean (standard deviation) of $107,997 ($249,941), a median of $18,247, and an interquartile range of $3422 to $97,375 (data not shown).

In assessing interaction-level concordance, 63% of all payment amounts in OP were classified as concordant disclosures. Regarding the number of OP payments, 27% were concordant disclosures, 34% were underdisclosures due to f/b/t/l payments, and 39% were underdisclosures due to non–f/b/t/l payments. When f/b/t/l payment entries in OP were excluded, the status of concordant disclosure for the amount and number of OP payments increased to 66% ($22,242,638) and 63% (5549), respectively. The percentage of payment entries with concordant disclosure status ranged from 43% to 71% depending on the payment amount. Payment entries at both ends of the spectrum had the lowest concordant disclosure rates, with 43% for payment entries between $0.01 and $100 and 58% for entries greater than $100,000 (Table 4). The concordance status also differed by the type of interactions. None of the OP payments for gift and royalty or license were disclosed in the AADMP, as there were no suitable corresponding categories. The proportion of payments with concordant disclosure for honoraria (45%), education (48%), and associated research (61%) was lower than the proportion of payments with concordant disclosure for research (90%), speaker fees (75%–79%), and consulting fees (74%)(Table 5).

In assessing dermatologist-level concordance including all OP entries, the number of dermatologists with no disclosure, overdisclosure only, concordant disclosure, discordant with overdisclosure, and discordant without overdisclosure statuses were 234 (30%), 70 (9%), 9 (1%), 251 (33%), and 204 (27%), respectively. When f/b/t/l entries were excluded, those figures changed to 347 (45%), 108 (14%), 79 (10%), 157 (20%), and 77 (10%), respectively. The characteristics of these dermatologists and their associated industry interactions by disclosure status are shown in the eTable. Dermatologists in the discordant with overdisclosure group had the highest median number and amount of OP payments, followed by those in the concordant disclosure and discordant without overdisclosure groups. Additionally, discordant with overdisclosure dermatologists also had the highest median and mean number of unique industry interactions not on OP, followed by those in the overdisclosure only and no disclosure groups. Academic and private practice settings did not impact dermatologists’ disclosure status. The percentage of female and male dermatologists in the discordant group was 25% and 36%, respectively.

Dermatologists reported a total of 1756 unique industry relationships in the AADMP that were not found on OP. Of these, 1440 (82%) relationships were from 236 dermatologists who had industry payments on OP. The remaining 316 relationships were from 108 dermatologists who had no payments on OP. Although 114 companies reported payments to dermatologists on OP, dermatologists in the AADMP reported interactions with an additional 430 companies.

Comment

In this study, we demonstrated discordance between dermatologist self-reported financial interactions in the AADMP compared with those reported by industry via OP. After excluding f/b/t/l entries, approximately two-thirds of the total amount and number of payments in OP were disclosed, while 31% of dermatologists had discordant disclosure status.

Prior investigations in other medical fields showed high discrepancy rates between industry-reported and physician-reported relationships ranging from 23% to 62%, with studies utilizing various methodologies.6-9,11,12,14,15 Only a few studies have utilized the OP database.8,12,15 Thompson et al12 compared OP payment data with physician financial disclosure at an annual gynecology scientific meeting and found although 209 of 335 (62%) physicians had interactions listed in the OP database, only 24 (7%) listed at least 1 company in the meeting financial disclosure section. Of these 24 physicians, only 5 (21%) accurately disclosed financial relationships with all of the companies listed in OP. The investigators found 129 (38.5%) physicians and 33.7% of the $1.99 million OP payments had concordant disclosure status. When they excluded physicians who received less than $100, 53% of individuals had concordant disclosure.12 Hannon et al8 reported on inconsistencies between disclosures in the OP database and the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons Annual Meeting and found 259 (23%) of 1113 physicians meeting inclusion criteria had financial interactions listed in the OP database that were not reported in the meeting disclosures. Yee et al15 also utilized the OP database and compared it with author disclosures in 3 major ophthalmology journals.Of 670 authors, 367 (54.8%) had complete concordance, with 68 (10.1%) more reporting additional overdisclosures, leading to a discordant with underdisclosure rate of 35.1%. Additionally, $1.46 million (44.6%) of the $3.27 million OP payments had concordant disclosure status.15 Other studies compared individual companies’ online reports of physician payments with physician self-disclosures in annual meeting programs, clinical guidelines, and peer-reviewed publications.6,7,9,11,14

Our study demonstrated variation in disclosure status. Compared with other groups, dermatologists in the discordant with overdisclosure group on average had more interactions with and received higher payments from industry, which is consistent with studies in the orthopedic surgery literature.8,9 Male dermatologists had 11% more discordant disclosures than their female counterparts, which may be influenced by men having more industry interactions than women.3 Although small industry payments possessed the lowest concordant rate in our study, which has been observed,12 payments greater than $100,000 had the second-lowest concordance rate at 58%, which may be skewed by the small sample size. Rates of concordant disclosure differed among types of interactions, such as between research and associated research payments. This particular difference may be attributed to the incorrect listing of dermatologists as principal investigators or reduced awareness of payments, as associated research payments were made to the institution and not the individual.

Reasons for discrepancies between industry-reported and dermatologist-reported disclosures may include reporting time differences, lack of physician awareness of OP, industry reporting inaccuracies, dearth of contextual information associated with individual payment entries, and misunderstandings. Prior research demonstrated that the most common reasons for physician nondisclosure included misunderstanding disclosure requirements, unintentional omission of payment, and a lack of relationship between the industry payment and presentation topic.9,12 These factors likely contributed to the disclosure inconsistencies in our study. Similarly high rates of inconsistencies across different specialties suggest systemic concerns.

We found a substantial number of dermatologist-industry interactions listed in the AADMP that were not captured by OP, with 108 dermatologists (35%) having overdisclosures even when excluding f/b/t/l entries. The number of companies in these overdisclosures approximated 4 times the number of companies on OP. Other studies have also observed physician-industry interactions not displayed on OP.8,12,15 Because the Sunshine Act requires reporting only by certain companies, interactions surrounding products such as over-the-counter merchandise, cosmetics, lasers, novel devices, and new medications are generally not included. Further, OP may not capture nonmonetary industry relationships.