User login

Pediatric Melanoma Outcomes by Race and Socioeconomic Factors

To the Editor:

Skin cancers are extremely common worldwide. Malignant melanomas comprise approximately 1 in 5 of these cancers. Exposure to UV radiation is postulated to be responsible for a global rise in melanoma cases over the past 50 years.1 Pediatric melanoma is a particularly rare condition that affects approximately 6 in every 1 million children.2 Melanoma incidence in children ranges by age, increasing by approximately 10-fold from age 1 to 4 years to age 15 to 19 years. Tumor ulceration is a feature more commonly seen among children younger than 10 years and is associated with worse outcomes. Tumor thickness and ulceration strongly predict sentinel lymph node metastases among children, which also is associated with a poor prognosis.3

A recent study evaluating stage IV melanoma survival rates in adolescents and young adults (AYAs) vs older adults found that survival is much worse among AYAs. Thicker tumors and public health insurance also were associated with worse survival rates for AYAs, while early detection was associated with better survival rates.4

Health disparities and their role in the prognosis of pediatric melanoma is another important factor. One study analyzed this relationship at the state level using Texas Cancer Registry data (1995-2009).5 Patients’ socioeconomic status (SES) and driving distance to the nearest pediatric cancer care center were included in the analysis. Hispanic children were found to be 3 times more likely to present with advanced disease than non-Hispanic White children. Although SES and distance to the nearest treatment center were not found to affect the melanoma stage at presentation, Hispanic ethnicity or being in the lowest SES quartile were correlated with a higher mortality risk.5

When considering specific subtypes of melanoma, acral lentiginous melanoma (ALM) is known to develop in patients with skin of color. A 2023 study by Holman et al6 reported that the percentage of melanomas that were ALMs ranged from 0.8% in non-Hispanic White individuals to 19.1% in Hispanic Black, American Indian/Alaska Native, and Asian/Pacific Islander individuals. However, ALM is rare in children. In a pooled cohort study with patient information retrieved from the nationwide Dutch Pathology Registry, only 1 child and 1 adolescent were found to have ALM across a total of 514 patients.7 We sought to analyze pediatric melanoma outcomes based on race and other barriers to appropriate care.

We conducted a search of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database from January 1995 to December 2016 for patients aged 21 years and younger with a primary melanoma diagnosis. The primary outcome was the 5-year survival rate. County-level SES variables were used to calculate a prosperity index. Kaplan-Meier analysis and Cox proportional hazards model were used to compare 5-year survival rates among the different racial/ethnic groups.

A sample of 2742 patients was identified during the study period and followed for 5 years. Eighty-two percent were White, 6% Hispanic, 2% Asian, 1% Black, and 5% classified as other/unknown race (data were missing for 4%). The cohort was predominantly female (61%). White patients were more likely to present with localized disease than any other race/ethnicity (83% vs 65% in Hispanic, 60% in Asian/Pacific Islander, and 45% in Black patients [P<.05]).

Black and Hispanic patients had the worst 5-year survival rates on bivariate analysis. On multivariate analysis, this finding remained significant for Hispanic patients when compared with White patients (hazard ratio, 2.37 [P<.05]). Increasing age, male sex, advanced stage at diagnosis, and failure to receive surgery were associated with increased odds of mortality.

Patients with regionalized and disseminated disease had increased odds of mortality (6.16 and 64.45, respectively; P<.05) compared with patients with localized disease. Socioeconomic status and urbanization were not found to influence 5-year survival rates.

Pediatric melanoma often presents a clinical challenge with special considerations. Pediatric-specific predisposing risk factors for melanoma and an atypical clinical presentation are some of the major concerns that necessitate a tailored approach to this malignancy, especially among different age groups, skin types, and racial and socioeconomic groups.5

Standard ABCDE criteria often are inadequate for accurate detection of pediatric melanomas. Initial lesions often manifest as raised, red, amelanotic lesions mimicking pyogenic granulomas. Lesions tend to be very small (<6 mm in diameter) and can be uniform in color, thereby making the melanoma more difficult to detect compared to the characteristic findings in adults.5 Bleeding or ulceration often can be a warning sign during physical examination.

With regard to incidence, pediatric melanoma is relatively rare. Since the 1970s, the incidence of pediatric melanoma has been increasing; however, a recent analysis of the SEER database showed a decreasing trend from 2000 to 2010.4

Our analysis of the SEER data showed an increased risk for pediatric melanoma in older adolescents. In addition, the incidence of pediatric melanoma was higher in females of all racial groups except Asian/Pacific Islander individuals. However, SES was not found to significantly influence the 5-year survival rate in pediatric melanoma.

White pediatric patients were more likely to present with localized disease compared with other races. Pediatric melanoma patients with regional disease had a 6-fold increase in mortality rate vs those with localized disease; those with disseminated disease had a 65-fold higher risk. Consistent with this, Black and Hispanic patients had the worst 5-year survival rates on bivariate analysis.

These findings suggest a relationship between race, melanoma spread, and disease severity. Patient education programs need to be directed specifically to minority groups to improve their knowledge on evolving skin lesions and sun protection practices. Physicians also need to have heightened suspicion and better knowledge of the unique traits of pediatric melanoma.5

Given the considerable influence these disparities can have on melanoma outcomes, further research is needed to characterize outcomes based on race and determine obstacles to appropriate care. Improved public outreach initiatives that accommodate specific cultural barriers (eg, language, traditional patterns of behavior) also are required to improve current circumstances.

- Arnold M, Singh D, Laversanne M, et al. Global burden of cutaneous melanoma in 2020 and projections to 2040. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:495-503.

- McCormack L, Hawryluk EB. Pediatric melanoma update. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2018;153:707-715.

- Saiyed FK, Hamilton EC, Austin MT. Pediatric melanoma: incidence, treatment, and prognosis. Pediatric Health Med Ther. 2017;8:39-45.

- Wojcik KY, Hawkins M, Anderson-Mellies A, et al. Melanoma survival by age group: population-based disparities for adolescent and young adult patients by stage, tumor thickness, and insurance type. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:831-840.

- Hamilton EC, Nguyen HT, Chang YC, et al. Health disparities influence childhood melanoma stage at diagnosis and outcome. J Pediatr. 2016;175:182-187.

- Holman DM, King JB, White A, et al. Acral lentiginous melanoma incidence by sex, race, ethnicity, and stage in the United States, 2010-2019. Prev Med. 2023;175:107692. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2023.107692

- El Sharouni MA, Rawson RV, Potter AJ, et al. Melanomas in children and adolescents: clinicopathologic features and survival outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:609-616. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.08.067

To the Editor:

Skin cancers are extremely common worldwide. Malignant melanomas comprise approximately 1 in 5 of these cancers. Exposure to UV radiation is postulated to be responsible for a global rise in melanoma cases over the past 50 years.1 Pediatric melanoma is a particularly rare condition that affects approximately 6 in every 1 million children.2 Melanoma incidence in children ranges by age, increasing by approximately 10-fold from age 1 to 4 years to age 15 to 19 years. Tumor ulceration is a feature more commonly seen among children younger than 10 years and is associated with worse outcomes. Tumor thickness and ulceration strongly predict sentinel lymph node metastases among children, which also is associated with a poor prognosis.3

A recent study evaluating stage IV melanoma survival rates in adolescents and young adults (AYAs) vs older adults found that survival is much worse among AYAs. Thicker tumors and public health insurance also were associated with worse survival rates for AYAs, while early detection was associated with better survival rates.4

Health disparities and their role in the prognosis of pediatric melanoma is another important factor. One study analyzed this relationship at the state level using Texas Cancer Registry data (1995-2009).5 Patients’ socioeconomic status (SES) and driving distance to the nearest pediatric cancer care center were included in the analysis. Hispanic children were found to be 3 times more likely to present with advanced disease than non-Hispanic White children. Although SES and distance to the nearest treatment center were not found to affect the melanoma stage at presentation, Hispanic ethnicity or being in the lowest SES quartile were correlated with a higher mortality risk.5

When considering specific subtypes of melanoma, acral lentiginous melanoma (ALM) is known to develop in patients with skin of color. A 2023 study by Holman et al6 reported that the percentage of melanomas that were ALMs ranged from 0.8% in non-Hispanic White individuals to 19.1% in Hispanic Black, American Indian/Alaska Native, and Asian/Pacific Islander individuals. However, ALM is rare in children. In a pooled cohort study with patient information retrieved from the nationwide Dutch Pathology Registry, only 1 child and 1 adolescent were found to have ALM across a total of 514 patients.7 We sought to analyze pediatric melanoma outcomes based on race and other barriers to appropriate care.

We conducted a search of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database from January 1995 to December 2016 for patients aged 21 years and younger with a primary melanoma diagnosis. The primary outcome was the 5-year survival rate. County-level SES variables were used to calculate a prosperity index. Kaplan-Meier analysis and Cox proportional hazards model were used to compare 5-year survival rates among the different racial/ethnic groups.

A sample of 2742 patients was identified during the study period and followed for 5 years. Eighty-two percent were White, 6% Hispanic, 2% Asian, 1% Black, and 5% classified as other/unknown race (data were missing for 4%). The cohort was predominantly female (61%). White patients were more likely to present with localized disease than any other race/ethnicity (83% vs 65% in Hispanic, 60% in Asian/Pacific Islander, and 45% in Black patients [P<.05]).

Black and Hispanic patients had the worst 5-year survival rates on bivariate analysis. On multivariate analysis, this finding remained significant for Hispanic patients when compared with White patients (hazard ratio, 2.37 [P<.05]). Increasing age, male sex, advanced stage at diagnosis, and failure to receive surgery were associated with increased odds of mortality.

Patients with regionalized and disseminated disease had increased odds of mortality (6.16 and 64.45, respectively; P<.05) compared with patients with localized disease. Socioeconomic status and urbanization were not found to influence 5-year survival rates.

Pediatric melanoma often presents a clinical challenge with special considerations. Pediatric-specific predisposing risk factors for melanoma and an atypical clinical presentation are some of the major concerns that necessitate a tailored approach to this malignancy, especially among different age groups, skin types, and racial and socioeconomic groups.5

Standard ABCDE criteria often are inadequate for accurate detection of pediatric melanomas. Initial lesions often manifest as raised, red, amelanotic lesions mimicking pyogenic granulomas. Lesions tend to be very small (<6 mm in diameter) and can be uniform in color, thereby making the melanoma more difficult to detect compared to the characteristic findings in adults.5 Bleeding or ulceration often can be a warning sign during physical examination.

With regard to incidence, pediatric melanoma is relatively rare. Since the 1970s, the incidence of pediatric melanoma has been increasing; however, a recent analysis of the SEER database showed a decreasing trend from 2000 to 2010.4

Our analysis of the SEER data showed an increased risk for pediatric melanoma in older adolescents. In addition, the incidence of pediatric melanoma was higher in females of all racial groups except Asian/Pacific Islander individuals. However, SES was not found to significantly influence the 5-year survival rate in pediatric melanoma.

White pediatric patients were more likely to present with localized disease compared with other races. Pediatric melanoma patients with regional disease had a 6-fold increase in mortality rate vs those with localized disease; those with disseminated disease had a 65-fold higher risk. Consistent with this, Black and Hispanic patients had the worst 5-year survival rates on bivariate analysis.

These findings suggest a relationship between race, melanoma spread, and disease severity. Patient education programs need to be directed specifically to minority groups to improve their knowledge on evolving skin lesions and sun protection practices. Physicians also need to have heightened suspicion and better knowledge of the unique traits of pediatric melanoma.5

Given the considerable influence these disparities can have on melanoma outcomes, further research is needed to characterize outcomes based on race and determine obstacles to appropriate care. Improved public outreach initiatives that accommodate specific cultural barriers (eg, language, traditional patterns of behavior) also are required to improve current circumstances.

To the Editor:

Skin cancers are extremely common worldwide. Malignant melanomas comprise approximately 1 in 5 of these cancers. Exposure to UV radiation is postulated to be responsible for a global rise in melanoma cases over the past 50 years.1 Pediatric melanoma is a particularly rare condition that affects approximately 6 in every 1 million children.2 Melanoma incidence in children ranges by age, increasing by approximately 10-fold from age 1 to 4 years to age 15 to 19 years. Tumor ulceration is a feature more commonly seen among children younger than 10 years and is associated with worse outcomes. Tumor thickness and ulceration strongly predict sentinel lymph node metastases among children, which also is associated with a poor prognosis.3

A recent study evaluating stage IV melanoma survival rates in adolescents and young adults (AYAs) vs older adults found that survival is much worse among AYAs. Thicker tumors and public health insurance also were associated with worse survival rates for AYAs, while early detection was associated with better survival rates.4

Health disparities and their role in the prognosis of pediatric melanoma is another important factor. One study analyzed this relationship at the state level using Texas Cancer Registry data (1995-2009).5 Patients’ socioeconomic status (SES) and driving distance to the nearest pediatric cancer care center were included in the analysis. Hispanic children were found to be 3 times more likely to present with advanced disease than non-Hispanic White children. Although SES and distance to the nearest treatment center were not found to affect the melanoma stage at presentation, Hispanic ethnicity or being in the lowest SES quartile were correlated with a higher mortality risk.5

When considering specific subtypes of melanoma, acral lentiginous melanoma (ALM) is known to develop in patients with skin of color. A 2023 study by Holman et al6 reported that the percentage of melanomas that were ALMs ranged from 0.8% in non-Hispanic White individuals to 19.1% in Hispanic Black, American Indian/Alaska Native, and Asian/Pacific Islander individuals. However, ALM is rare in children. In a pooled cohort study with patient information retrieved from the nationwide Dutch Pathology Registry, only 1 child and 1 adolescent were found to have ALM across a total of 514 patients.7 We sought to analyze pediatric melanoma outcomes based on race and other barriers to appropriate care.

We conducted a search of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database from January 1995 to December 2016 for patients aged 21 years and younger with a primary melanoma diagnosis. The primary outcome was the 5-year survival rate. County-level SES variables were used to calculate a prosperity index. Kaplan-Meier analysis and Cox proportional hazards model were used to compare 5-year survival rates among the different racial/ethnic groups.

A sample of 2742 patients was identified during the study period and followed for 5 years. Eighty-two percent were White, 6% Hispanic, 2% Asian, 1% Black, and 5% classified as other/unknown race (data were missing for 4%). The cohort was predominantly female (61%). White patients were more likely to present with localized disease than any other race/ethnicity (83% vs 65% in Hispanic, 60% in Asian/Pacific Islander, and 45% in Black patients [P<.05]).

Black and Hispanic patients had the worst 5-year survival rates on bivariate analysis. On multivariate analysis, this finding remained significant for Hispanic patients when compared with White patients (hazard ratio, 2.37 [P<.05]). Increasing age, male sex, advanced stage at diagnosis, and failure to receive surgery were associated with increased odds of mortality.

Patients with regionalized and disseminated disease had increased odds of mortality (6.16 and 64.45, respectively; P<.05) compared with patients with localized disease. Socioeconomic status and urbanization were not found to influence 5-year survival rates.

Pediatric melanoma often presents a clinical challenge with special considerations. Pediatric-specific predisposing risk factors for melanoma and an atypical clinical presentation are some of the major concerns that necessitate a tailored approach to this malignancy, especially among different age groups, skin types, and racial and socioeconomic groups.5

Standard ABCDE criteria often are inadequate for accurate detection of pediatric melanomas. Initial lesions often manifest as raised, red, amelanotic lesions mimicking pyogenic granulomas. Lesions tend to be very small (<6 mm in diameter) and can be uniform in color, thereby making the melanoma more difficult to detect compared to the characteristic findings in adults.5 Bleeding or ulceration often can be a warning sign during physical examination.

With regard to incidence, pediatric melanoma is relatively rare. Since the 1970s, the incidence of pediatric melanoma has been increasing; however, a recent analysis of the SEER database showed a decreasing trend from 2000 to 2010.4

Our analysis of the SEER data showed an increased risk for pediatric melanoma in older adolescents. In addition, the incidence of pediatric melanoma was higher in females of all racial groups except Asian/Pacific Islander individuals. However, SES was not found to significantly influence the 5-year survival rate in pediatric melanoma.

White pediatric patients were more likely to present with localized disease compared with other races. Pediatric melanoma patients with regional disease had a 6-fold increase in mortality rate vs those with localized disease; those with disseminated disease had a 65-fold higher risk. Consistent with this, Black and Hispanic patients had the worst 5-year survival rates on bivariate analysis.

These findings suggest a relationship between race, melanoma spread, and disease severity. Patient education programs need to be directed specifically to minority groups to improve their knowledge on evolving skin lesions and sun protection practices. Physicians also need to have heightened suspicion and better knowledge of the unique traits of pediatric melanoma.5

Given the considerable influence these disparities can have on melanoma outcomes, further research is needed to characterize outcomes based on race and determine obstacles to appropriate care. Improved public outreach initiatives that accommodate specific cultural barriers (eg, language, traditional patterns of behavior) also are required to improve current circumstances.

- Arnold M, Singh D, Laversanne M, et al. Global burden of cutaneous melanoma in 2020 and projections to 2040. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:495-503.

- McCormack L, Hawryluk EB. Pediatric melanoma update. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2018;153:707-715.

- Saiyed FK, Hamilton EC, Austin MT. Pediatric melanoma: incidence, treatment, and prognosis. Pediatric Health Med Ther. 2017;8:39-45.

- Wojcik KY, Hawkins M, Anderson-Mellies A, et al. Melanoma survival by age group: population-based disparities for adolescent and young adult patients by stage, tumor thickness, and insurance type. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:831-840.

- Hamilton EC, Nguyen HT, Chang YC, et al. Health disparities influence childhood melanoma stage at diagnosis and outcome. J Pediatr. 2016;175:182-187.

- Holman DM, King JB, White A, et al. Acral lentiginous melanoma incidence by sex, race, ethnicity, and stage in the United States, 2010-2019. Prev Med. 2023;175:107692. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2023.107692

- El Sharouni MA, Rawson RV, Potter AJ, et al. Melanomas in children and adolescents: clinicopathologic features and survival outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:609-616. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.08.067

- Arnold M, Singh D, Laversanne M, et al. Global burden of cutaneous melanoma in 2020 and projections to 2040. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:495-503.

- McCormack L, Hawryluk EB. Pediatric melanoma update. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2018;153:707-715.

- Saiyed FK, Hamilton EC, Austin MT. Pediatric melanoma: incidence, treatment, and prognosis. Pediatric Health Med Ther. 2017;8:39-45.

- Wojcik KY, Hawkins M, Anderson-Mellies A, et al. Melanoma survival by age group: population-based disparities for adolescent and young adult patients by stage, tumor thickness, and insurance type. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:831-840.

- Hamilton EC, Nguyen HT, Chang YC, et al. Health disparities influence childhood melanoma stage at diagnosis and outcome. J Pediatr. 2016;175:182-187.

- Holman DM, King JB, White A, et al. Acral lentiginous melanoma incidence by sex, race, ethnicity, and stage in the United States, 2010-2019. Prev Med. 2023;175:107692. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2023.107692

- El Sharouni MA, Rawson RV, Potter AJ, et al. Melanomas in children and adolescents: clinicopathologic features and survival outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:609-616. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.08.067

Practice Points

- Pediatric melanoma is a unique clinical entity with a different clinical presentation than in adults.

- Thicker tumors and disseminated disease are associated with a worse prognosis, and these factors are more commonly seen in Black and Hispanic patients.

Premedical Student Interest in and Exposure to Dermatology at Howard University

Diversity of health care professionals improves medical outcomes and quality of life in patients. 1 There is a lack of diversity in dermatology, with only 4.2% of dermatologists identifying as Hispanic and 3% identifying as African American, 2 possibly due to a lack of early exposure to dermatology among high school and undergraduate students, a low number of underrepresented students in medical school, a lack of formal mentorship programs geared to underrepresented students, and implicit biases. 1-4 Furthermore, the field is competitive, with many more applicants than available positions. In 2022, there were 851 applicants competing for 492 residency positions in dermatology. 5 Thus, it is important to educate young students about dermatology and understand root causes as to why the number of u nderrepresented in medicine (UiM) dermatologists remains stagnant.

According to Pritchett et al,4 it is crucial for dermatologists to interact with high school and college students to foster an early interest in dermatology. Many racial minority students do not progress from high school to college and then from college to medical school, which leaves a substantially reduced number of eligible UiM applicants who can progress into dermatology.6 Increasing the amount of UiM students going to medical school requires early mediation. Collaborating with pre-existing premedical school organizations through presentations and workshops is another way to promote an early interest in dermatology.4 Special consideration should be given to students who are UiM.

Among the general medical school curriculum, requirements for exposure to dermatology are not high. In one study, the median number of clinical and preclinical hours required was 10. Furthermore, 20% of 33 medical schools did not require preclinical dermatology hours (hours done before medical school rotations begin and in an academic setting), 36% required no clinical hours (rotational hours), 8% required no dermatology hours whatsoever, and only 10% required clinical dermatology rotation.3 Based on these findings, it is clear that dermatology is not well incorporated into medical school curricula. Furthermore, curricula have historically neglected to display adequate representation of skin of color.7 As a result, medical students generally have limited exposure to dermatology3 and are exposed even less to presentations of dermatologic issues in historically marginalized populations.7

Given the paucity of research on UiM students’ perceptions of dermatology prior to medical school, our cross-sectional survey study sought to evaluate the level of interest in dermatology of UiM premedical undergraduates. This survey specifically evaluated exposure to dermatology, preconceived notions about the field, and mentorship opportunities. By understanding these factors, dermatologists and dermatology residency programs can use this information to create mentorship opportunities and better adjust existing programs to meet students’ needs.

Methods

A 19-question multiple-choice survey was administered electronically (SurveyMonkey) in May 2020 to premedical students at Howard University (Washington, DC). One screening question was used: “What is your major?” Those who considered themselves a science major and/or with premedical interest were allowed to complete the survey. All students surveyed were members of the Health Professions Society at Howard University. Students who were interested in pursuing medical school were invited to respond. Approval for this study was obtained from the Howard University institutional review board (FWA00000891).

The survey was divided into 3 sections: Demographics, Exposure to Medicine and Dermatology, and Perceptions of Dermatology. The Demographics section addressed gender, age, and race/ethnicity. The Exposure to Medicine and Dermatology section addressed interest in attending medical school, shadowing experience, exposure to dermatology, and mentoring. The Perceptions of Dermatology section addressed preconceived notions about the field (eg, “dermatology is interesting and exciting”).

Statistical Analysis—The data represented are percentages based on the number of respondents who answered each question. Answers in response to “Please enter any comments” were organized into themes, and the number of respondents who discussed each theme was quantified into a table.

Results

A total of 271 survey invitations were sent to premedical students at Howard University. Students were informed of the study protocol and asked to consent before proceeding to have their responses anonymously collected. Based on the screening question, 152 participants qualified for the survey, and 152 participants completed it (response rate, 56%; completion rate, 100%). Participants were asked to complete the survey only once.

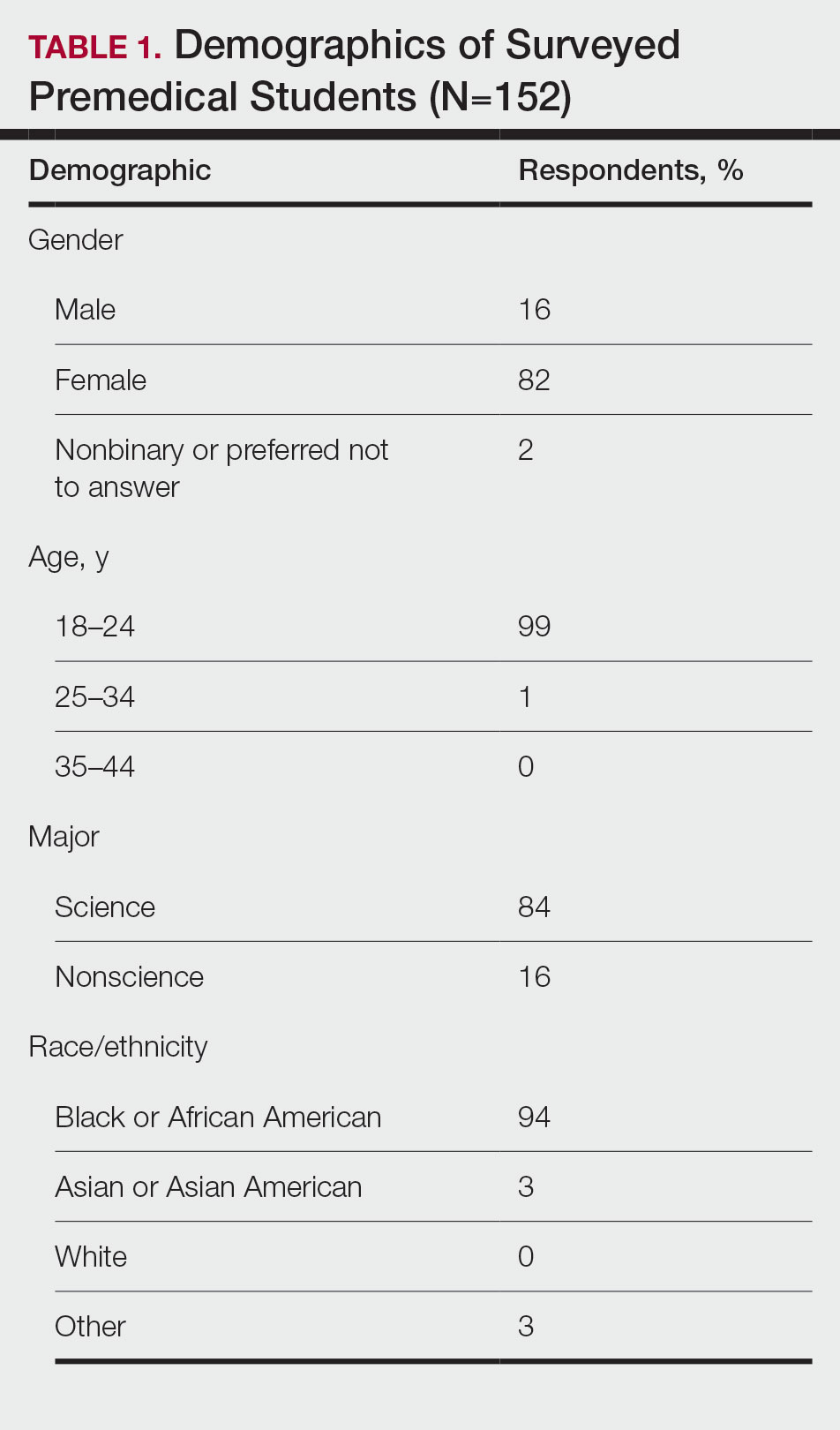

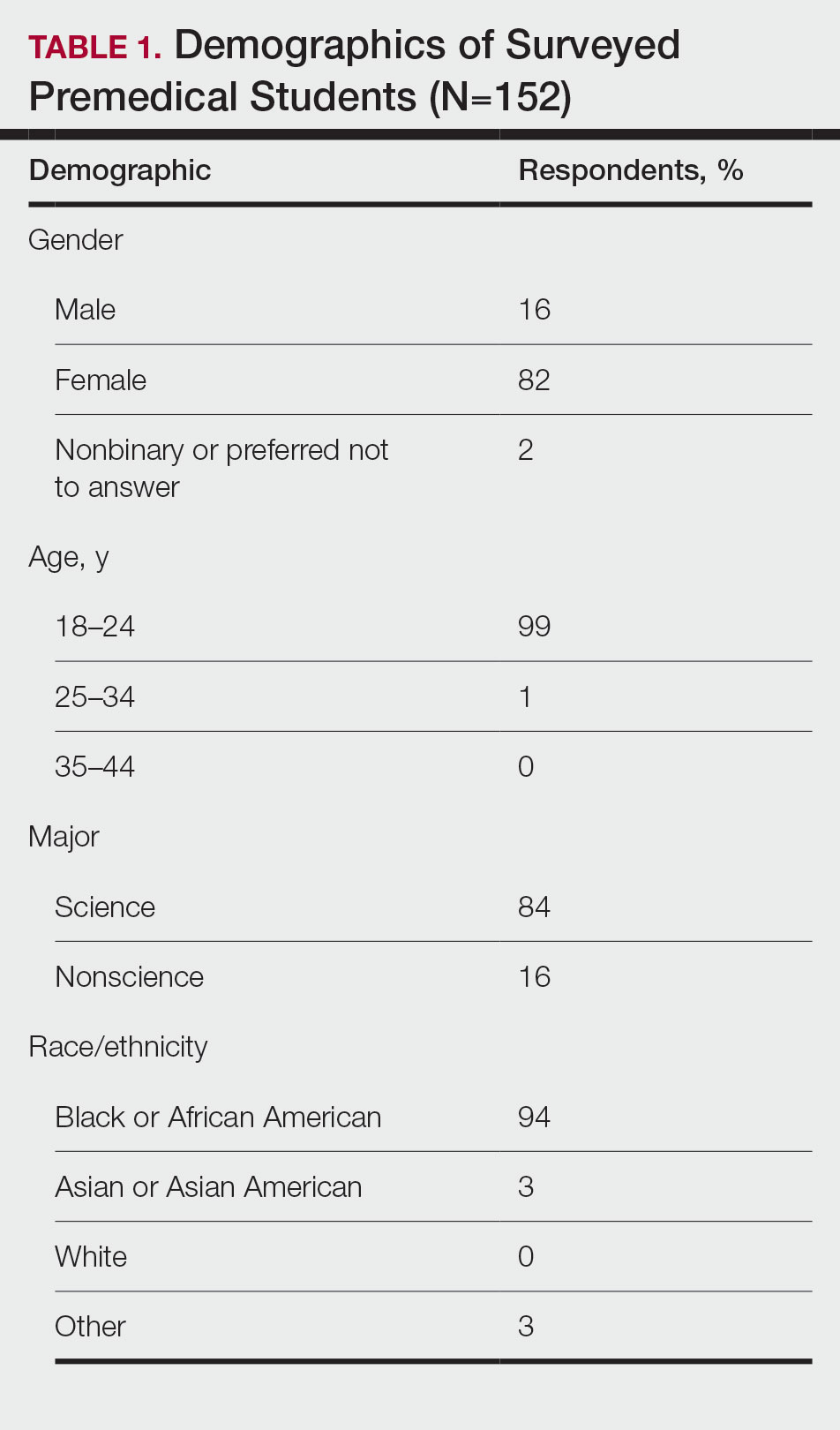

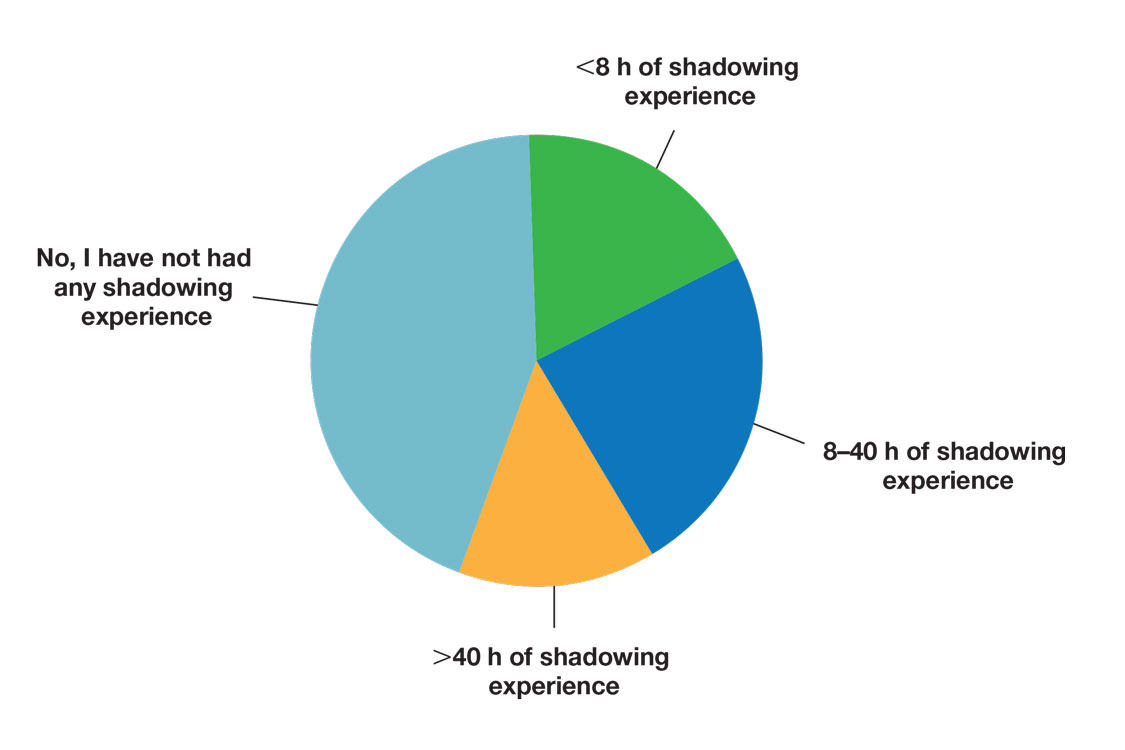

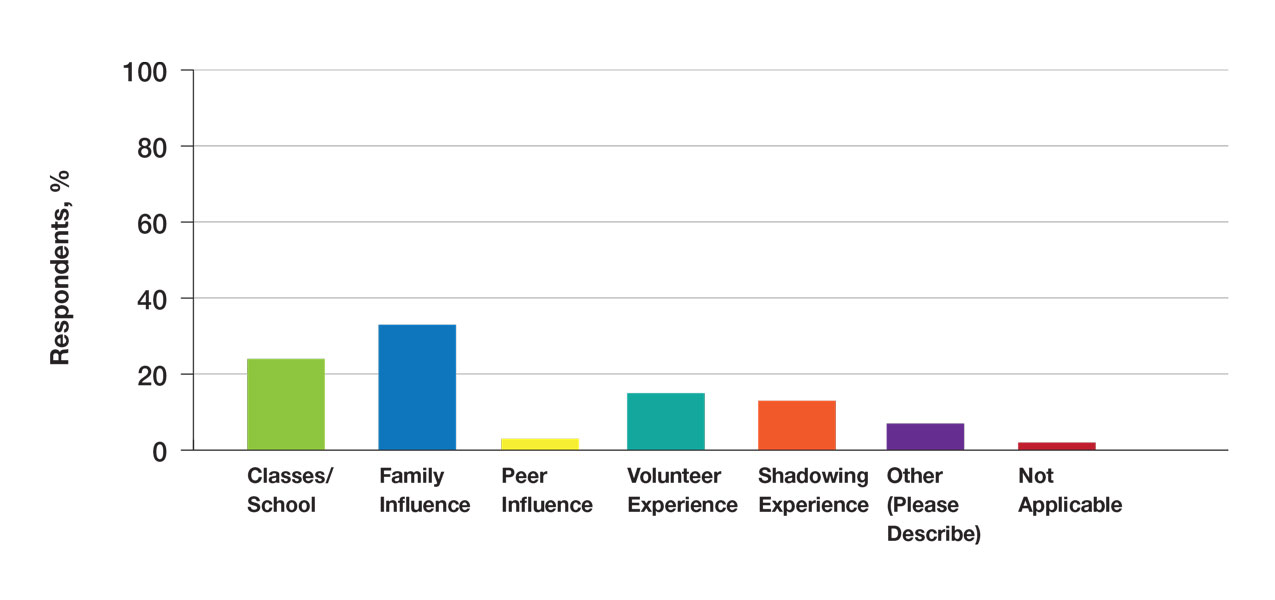

Demographics—Eighty-four percent of respondents identified as science majors, and the remaining 16% identified as nonscience premedical. Ninety-four percent of participants identified as Black or African American; 3% as Asian or Asian American; and the remaining 3% as Other. Most respondents were female (82%), 16% were male, and 2% were either nonbinary or preferred not to answer. Ninety-nine percent were aged 18 to 24 years, and 1% were aged 25 to 34 years (Table 1).

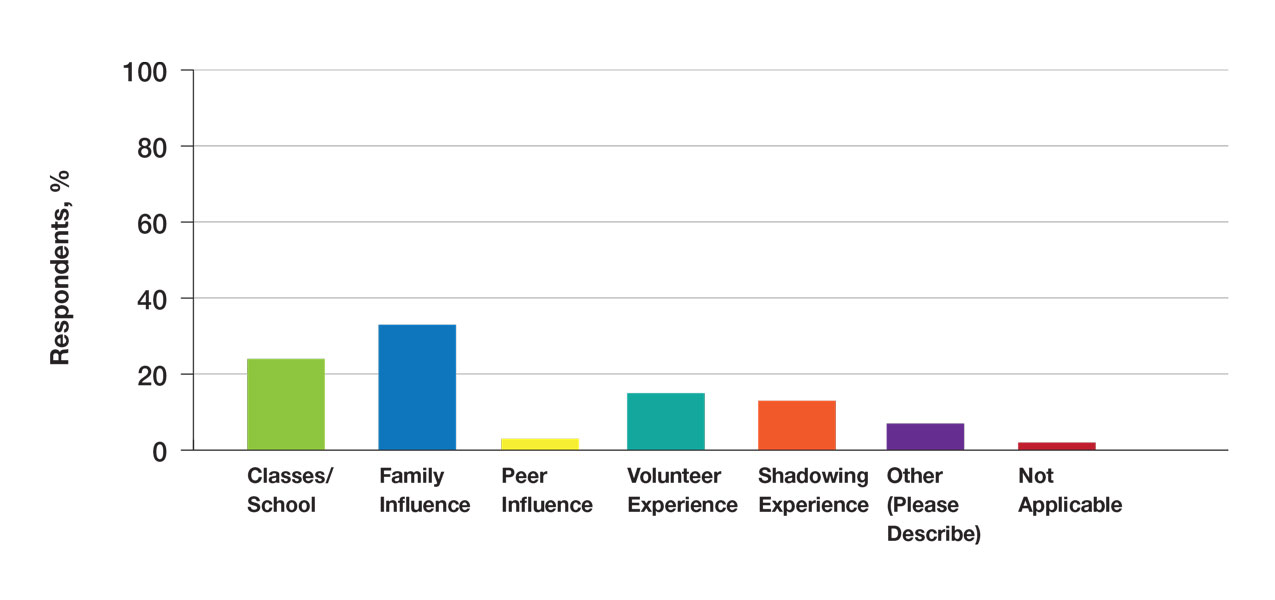

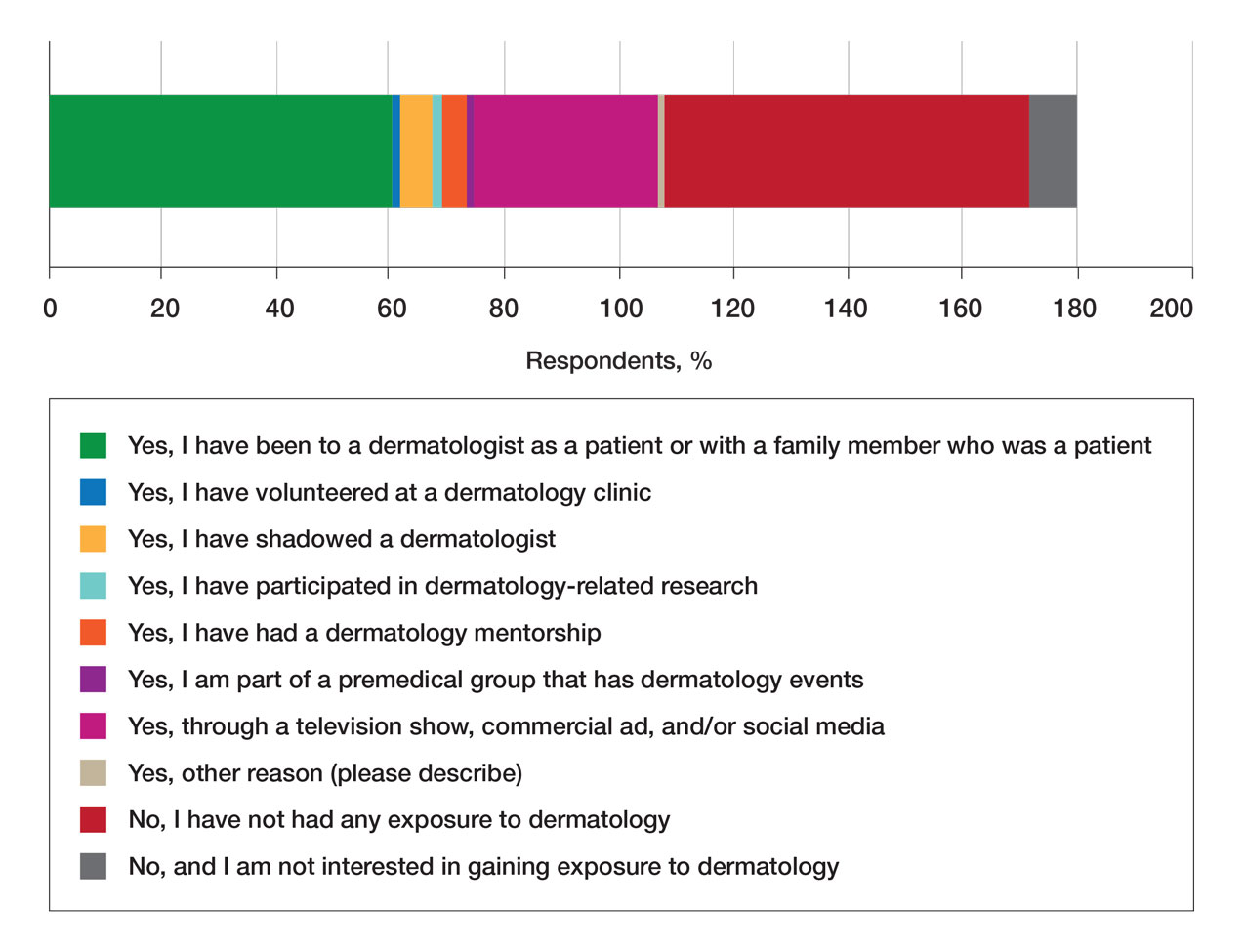

Exposure to Medicine and Dermatology—Ninety-three percent of participants planned on attending medical school, and most students developed an interest in medicine from an early age. Ninety-six percent cited that they became interested in medicine prior to beginning their undergraduate education, and 4% developed an interest as freshmen or sophomores. When asked what led to their interest in medicine, family influence had the single greatest impact on students’ decision to pursue medicine (33%). Classes/school were the second most influential factor (24%), followed by volunteering (15%), shadowing (13%), other (7%), and peer influence (3%)(Figure 1).

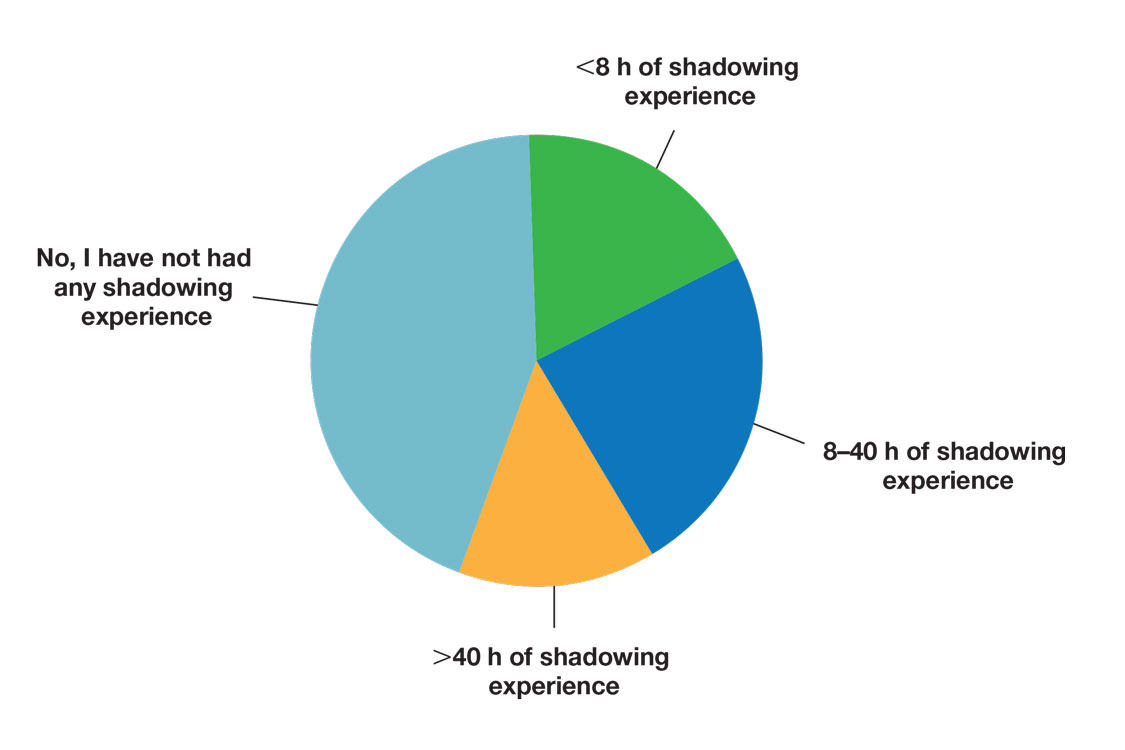

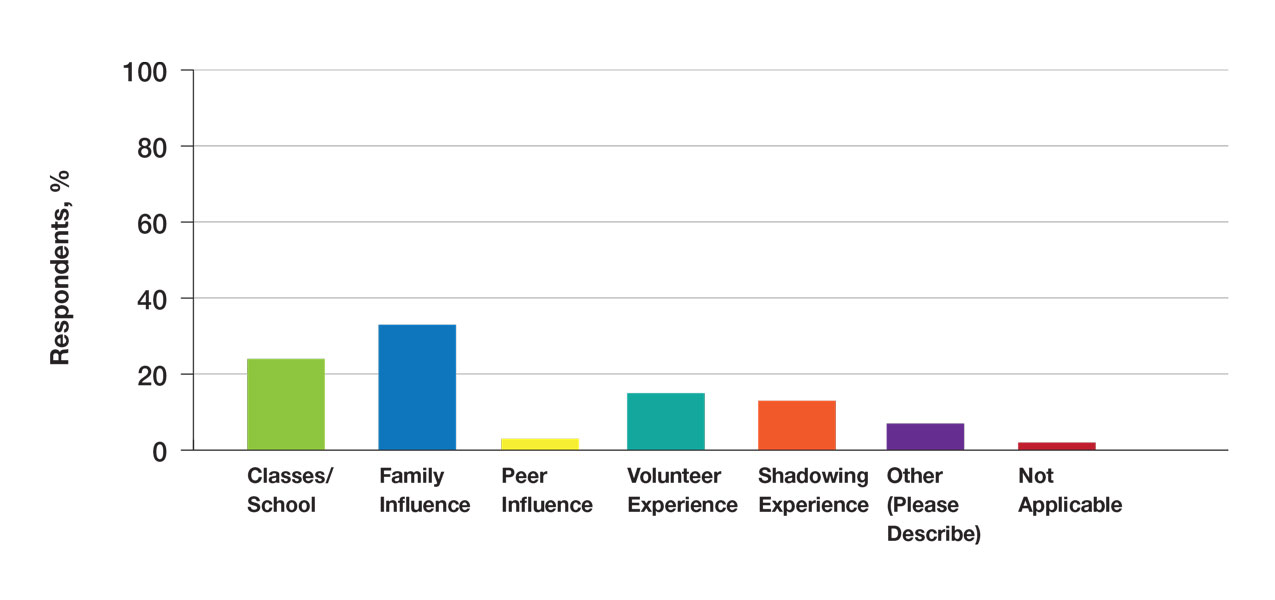

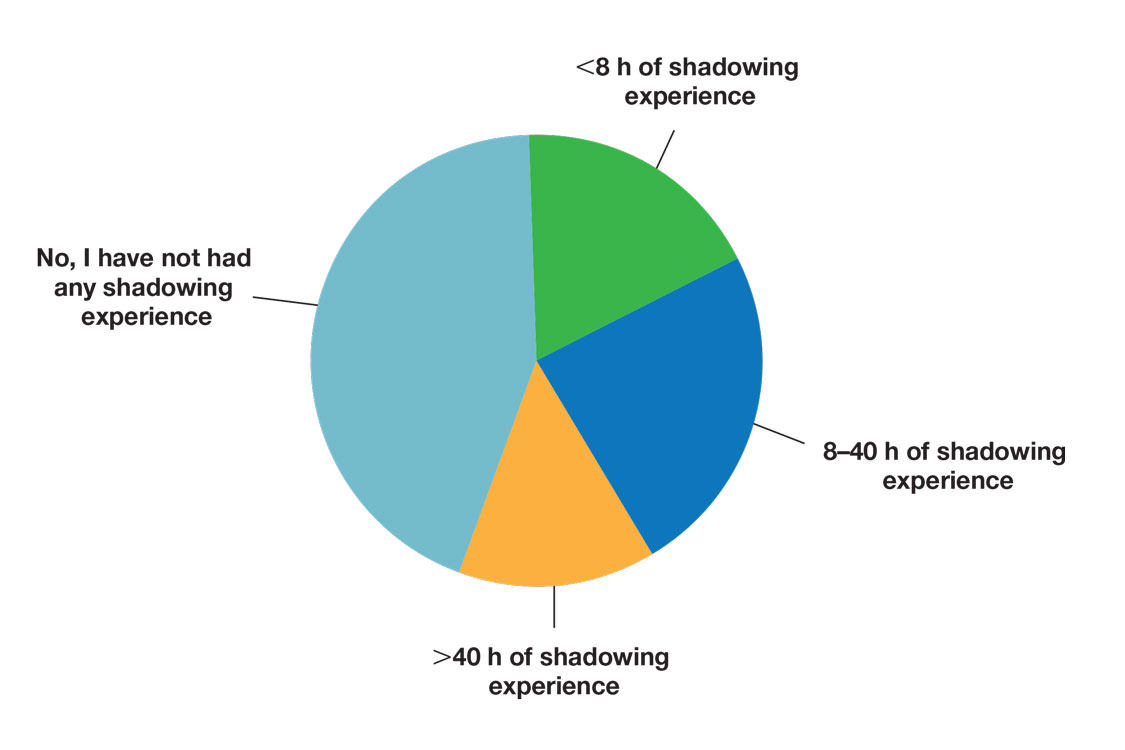

Many (56%) premedical students surveyed had shadowing experience to varying degrees. Approximately 18% had fewer than 8 hours of shadowing experience, 24% had 8 to 40 hours, and 14% had more than 40 hours. However, many (43%) premedical students had no shadowing experience (Figure 2). Similarly, 30% of premedical students responded to having a physician as a mentor.

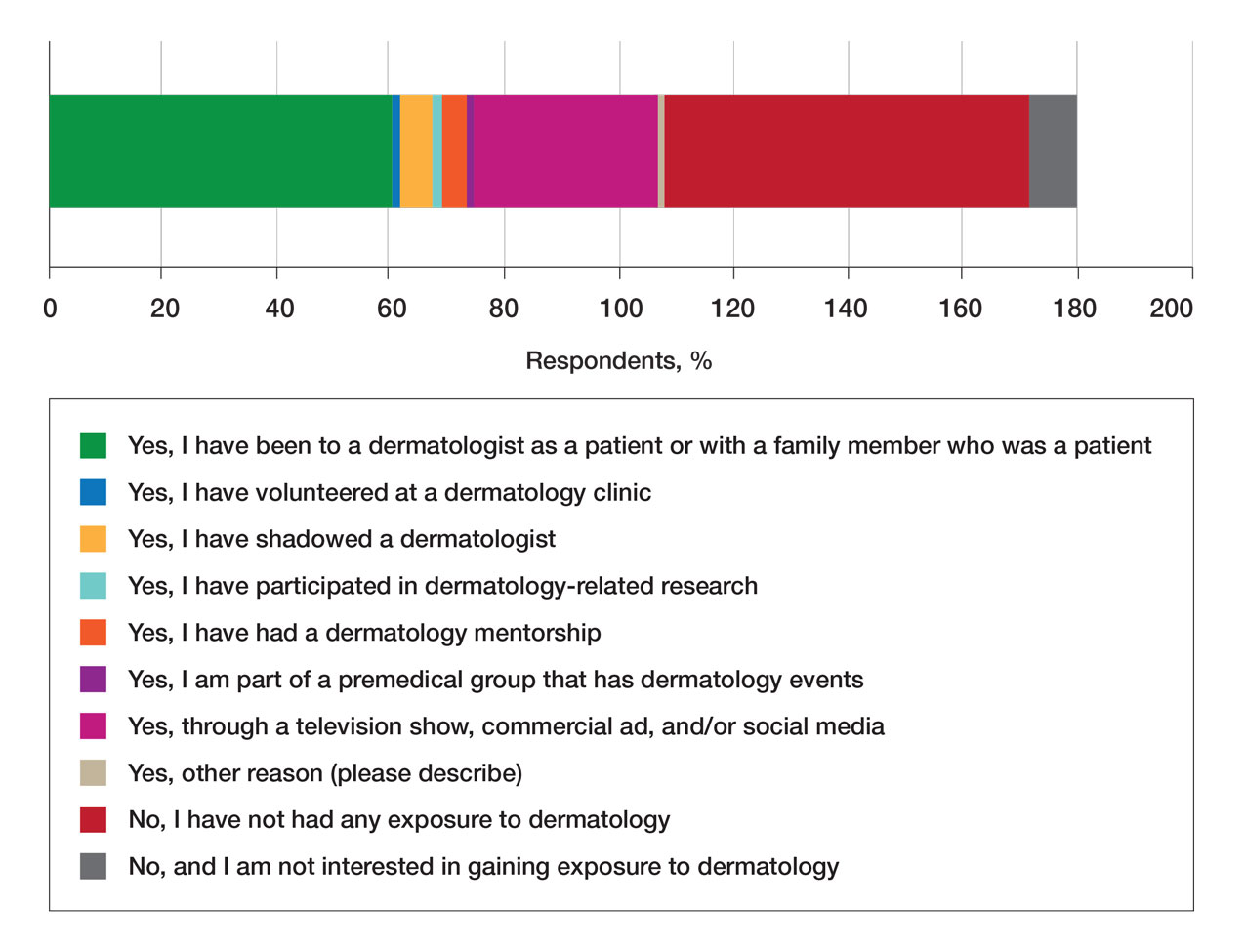

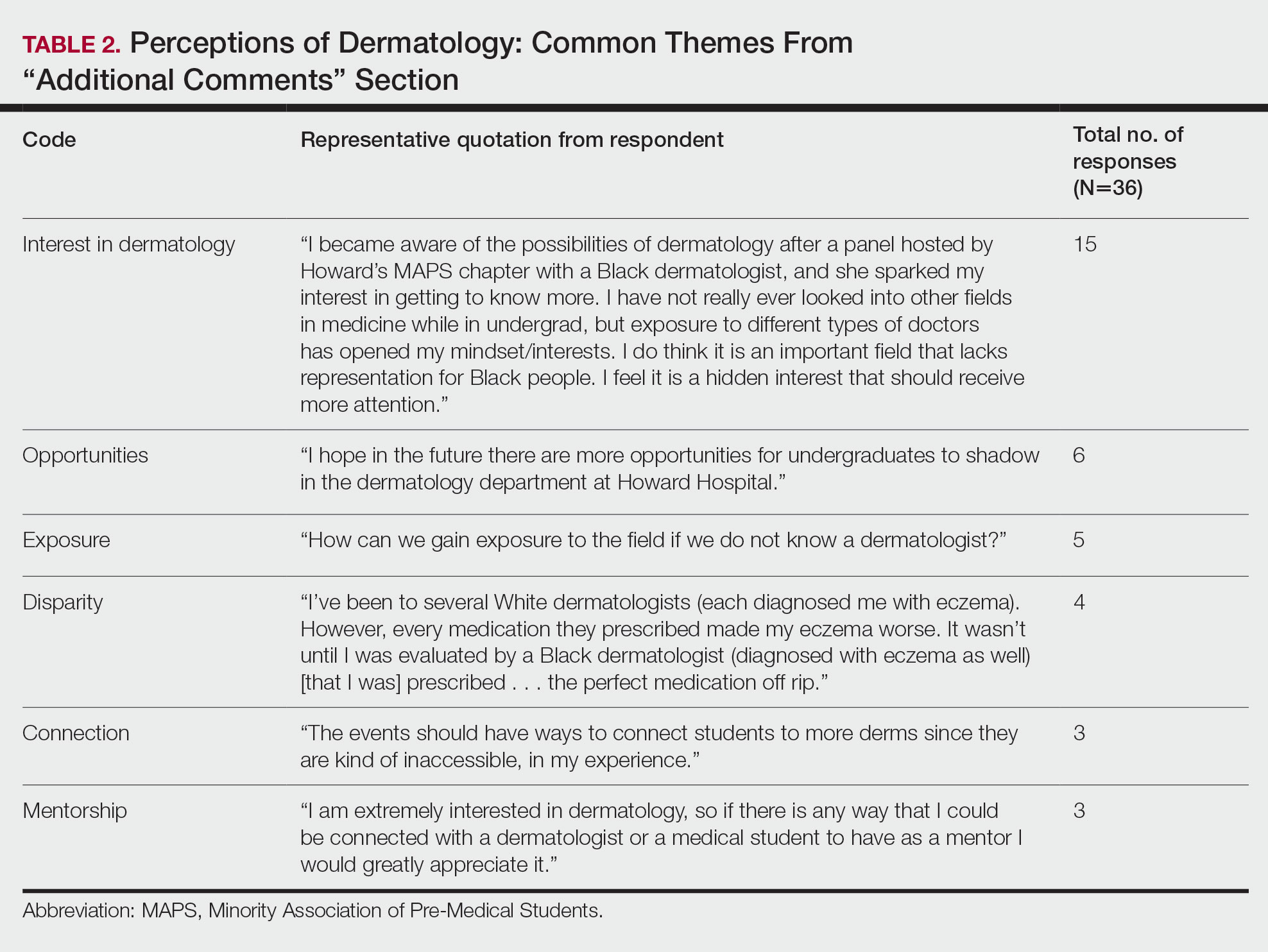

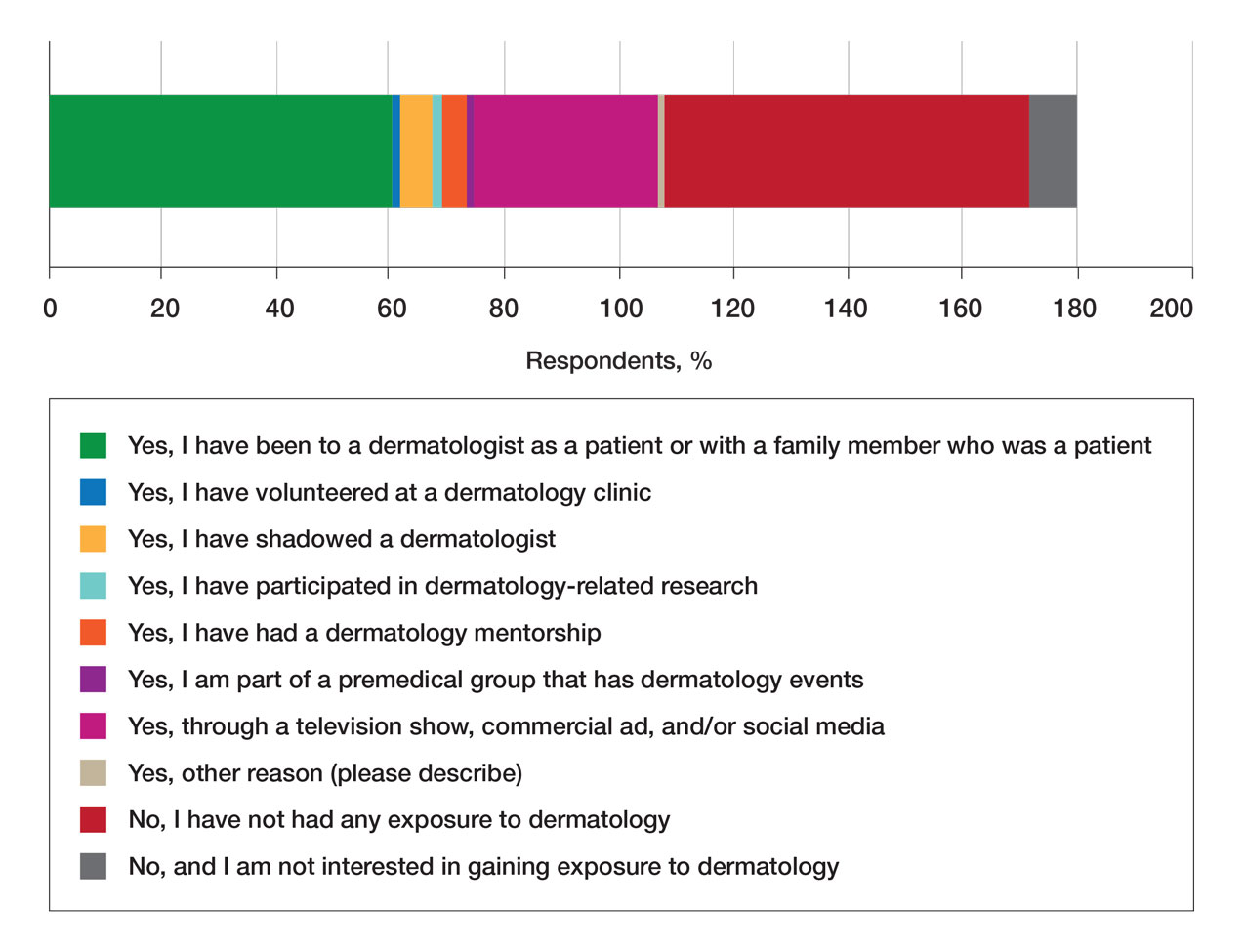

Regarding exposure to dermatology, 42% of premedical students had none. However, 58% of students had exposure to dermatology by being a patient themselves, 40% through seeing a dermatologist with a family member, 21% through seeing a dermatologist on television or social media, 5% through shadowing or volunteering, 3% through mentorship, and 1% through dermatology research (Figure 3).

Of students who said they were interested in dermatology (32%), 16% developed their interest before undergraduate education, while 9% developed interest in their freshman or sophomore year and 7% in their junior or senior year of undergraduate education. Three percent of respondents indicated that they had a dermatology mentorship.

Perceptions of Dermatology—To further evaluate the level of interest that UiM premedical students have in the field of dermatology, students were asked how much they agree or disagree on whether the field of dermatology is interesting. Sixty-three percent of the students agreed that the field of dermatology is interesting, 34% remained uncertain, and 3% disagreed. Additionally, students were asked whether they would consider dermatology as a career; 54% of respondents would consider dermatology as a career, 30% remained uncertain, and 16% would not consider dermatology as a career choice.

Nearly all (95%) students agreed that dermatologists do valuable work that goes beyond the scope of cosmetic procedures such as neuromodulators, fillers, chemical peels, and lasers. Some students also noted they had personal experiences interacting with a dermatologist. For example, one student described visiting the dermatologist many times to get a treatment regimen for their eczema.

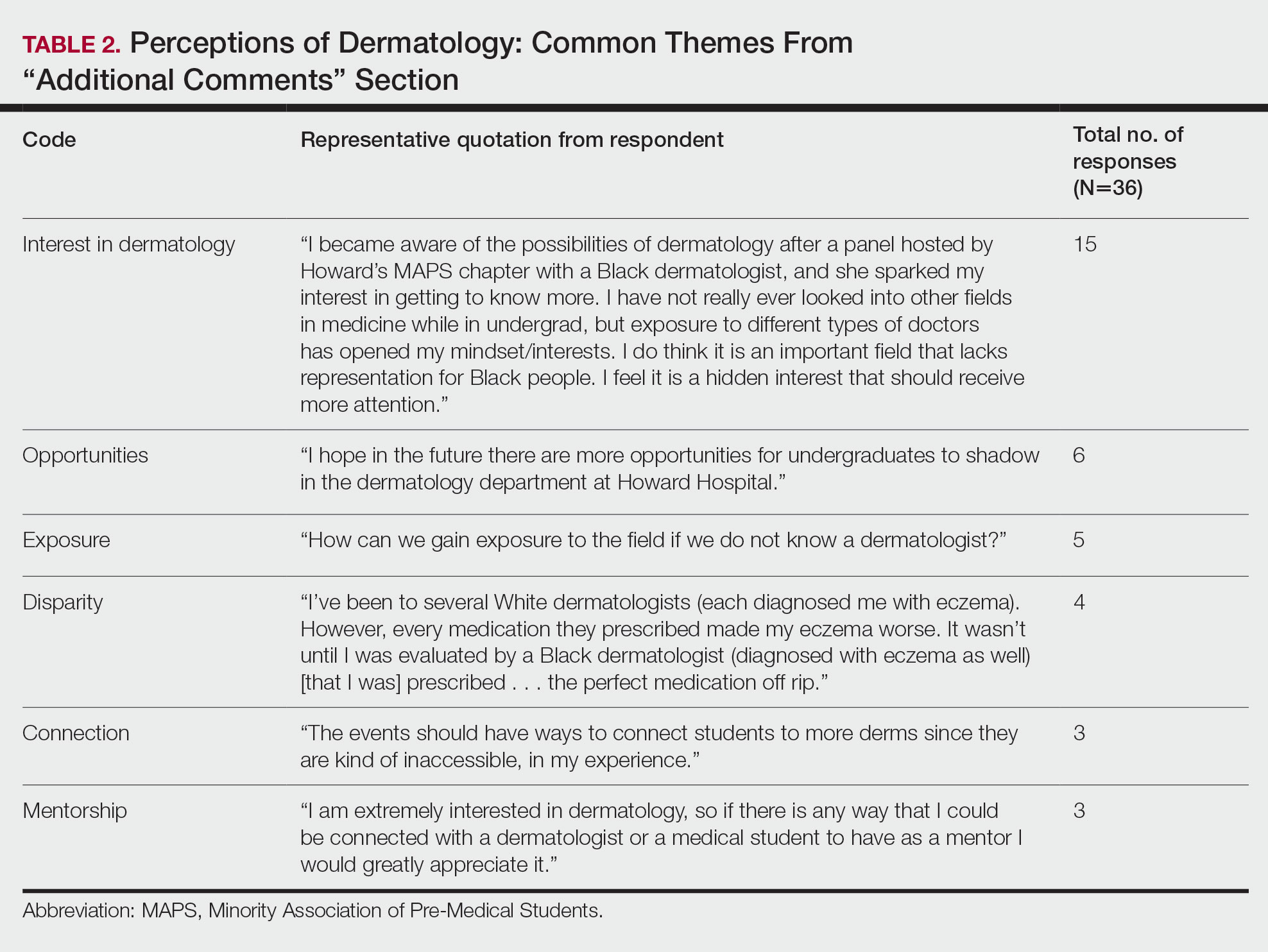

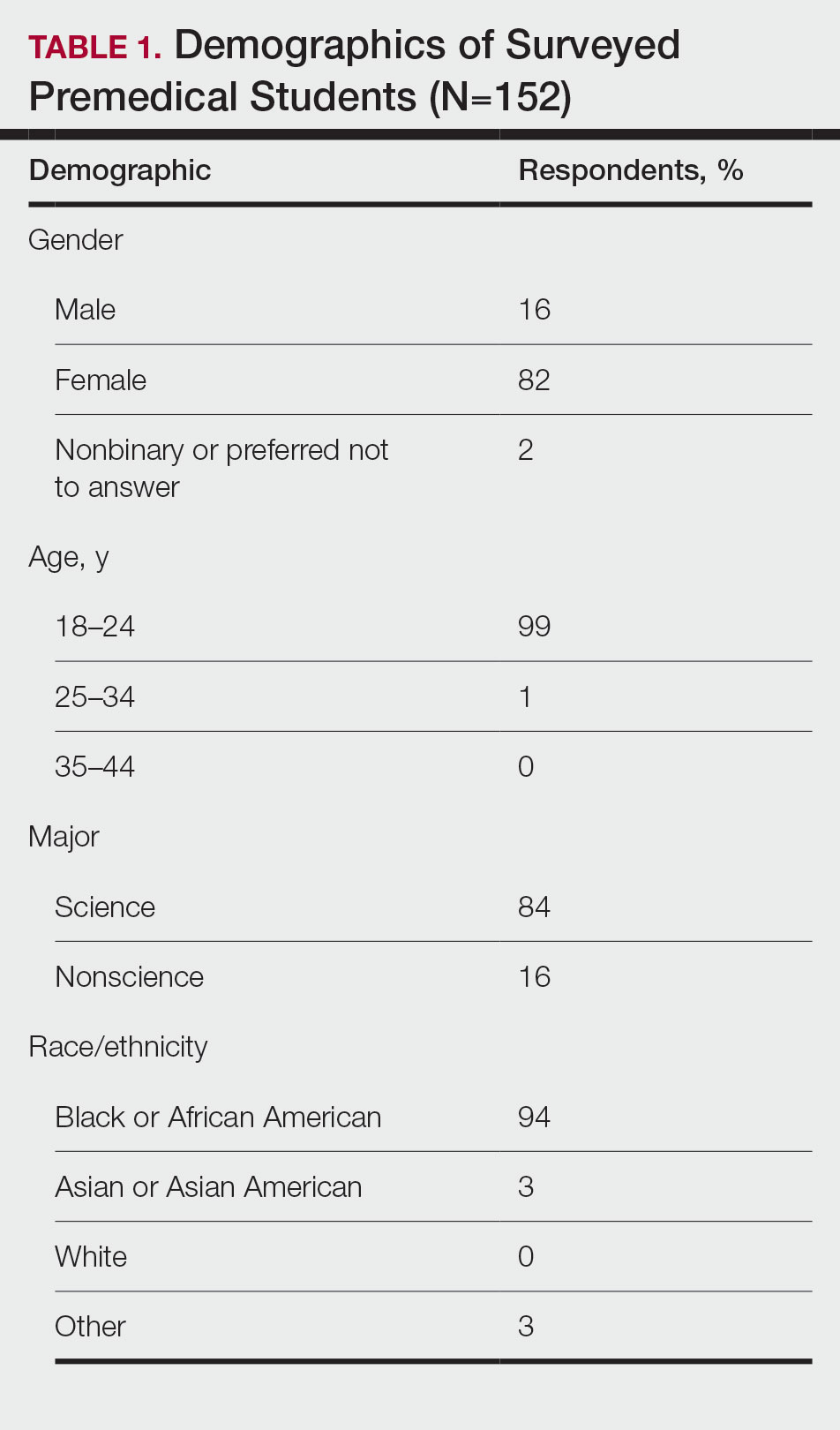

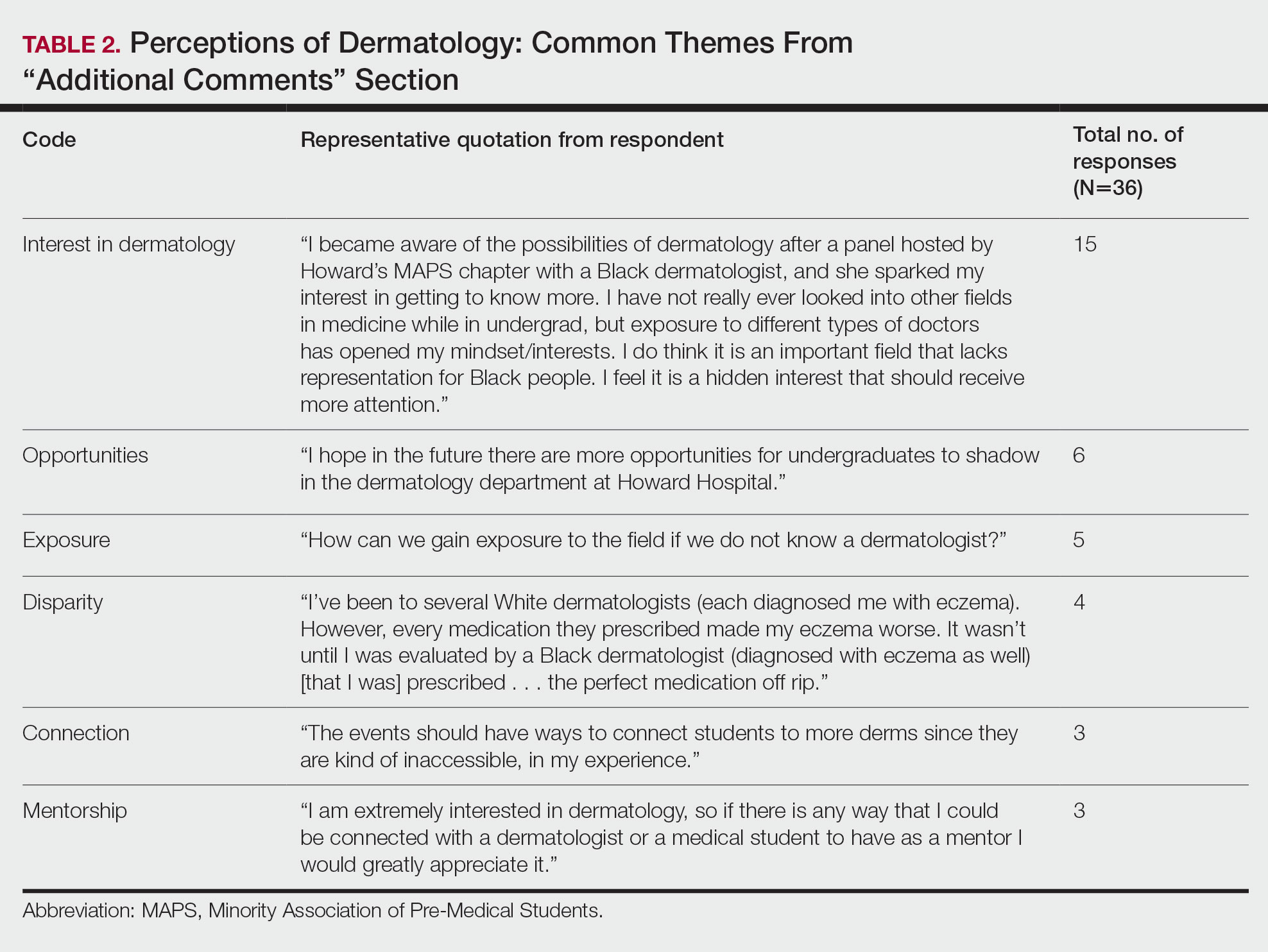

Overall themes from the survey are depicted in Table 2. Major themes found in the comments included the desire for more dermatology-related opportunities, mentorship, exposure, connections, and a discussion of disparities faced by Black patients and students within dermatology. Students also expressed an interest in dermatology and the desire to learn more about the specialty.

Comment

Interest in Dermatology—In this cross-sectional survey study of 152 UiM undergraduate students, it was found that many students were interested in dermatology as a career, and more than 70% would be interested in attending events that increased exposure to the field of dermatology. Of the students who had any exposure to dermatology, less than 5% had shadowed an actual dermatologist. The survey showed that there is great potential interest in exposing UiM undergraduate students to the field of dermatology. We found that UiM students are interested in learning more about dermatology, with 80% indicating that they would be willing to participate in dermatology-focused events if they were available. Overall, students mentioned a lack of opportunities, mentorship, exposure, and connections in dermatology despite their interest in the field.

Racial Disparities in Dermatology—Additionally, students discussed disparities they encountered with dermatology due to a lack of patient-provider race concordance and the perceived difference in care when encountering a race-concordant dermatologist. One student noted that they went to multiple White dermatologists for their eczema, and “it wasn’t until I was evaluated by a Black dermatologist (diagnosed with eczema as well) [that I was] prescribed . . . the perfect medication.” Another student noted how a Black dermatologist sparked their interest in getting to know more about the field and remarked that they “think it is an important field that lacks representation for Black people.” This research stresses the need for more dermatology mentorship among UiM undergraduates.

Family Influence on Career Selection—The majority of UiM students in our study became interested in medicine because of family, which is consistent with other studies. In a cross-sectional survey of 300 Pakistani students (150 medical and 150 nonmedical), 87% of students stated that their family had an influence on their career selection.8 In another study of 15 junior doctors in Sierra Leone, the most common reasons for pursuing medicine were the desire to help and familial and peer influence.9 This again showcases how family can have a positive impact on career selection for medical professionals and highlights the need for early intervention.

Shadowing—One way in which student exposure to dermatology can be effectively increased is by shadowing. In a study evaluating a 30-week shadowing program at the Pediatric Continuity Clinic in Los Angeles, California, a greater proportion of premedical students believed they had a good understanding of the job of a resident physician after the program’s completion compared to before starting the program (an increase from 78% to 100%).10 The proportion of students reporting a good understanding of the patient-physician relationship after completing the program also increased from 33% to 78%. Furthermore, 72% of the residents stated that having the undergraduates in the clinic was a positive experience.10 Thus, increasing shadowing opportunities is one extremely effective way to increase student knowledge and awareness of and exposure to dermatology.

Dermatology Mentors—Although 32% of students were interested in dermatology, 3% of students had mentorship in dermatology. In prior studies, it has been shown that mentorship is of great importance in student success and interest in pursuing a specialty. A report from the Association of American Medical Colleges 2019 Medical School Graduation Questionnaire found that the third most influential factor (52.1%) in specialty selection was role model influence.11 In fact, having a role model is consistently one of the top 3 influences on student specialty choice and interest in the last 5 years of survey research. Some studies also have shown mentorship as a positive influence in specialty interest at the undergraduate and graduate levels. A study on an undergraduate student interest group noted that surgeon mentorship and exposure were positive factors to students’ interests in surgery.12 In fact, the Association of American Medical Colleges noted that some surgical specialties, such as orthopedic surgery, had 45% of respondents who were interested in the specialty before medical school pursue their initial preference in medical school.13 Another survey corroborated these findings; more orthopedic-bound students compared with other specialties indicated they were more likely to pursue their field because of experiences prior to medical school.14

One of the reasons students might not have been exposed to as many opportunities for mentorship in dermatology is because the specialty is one of the smaller fields in medicine and tends to be concentrated in more well-resourced metropolitan areas.15 Dermatologists make up only 1.3% of the physician workforce.16 Because there might not be as much exposure to the field, students might also explore their interests in dermatology through other fields, such as through shadowing and observing primary care physicians who often treat patients with dermatologic issues. Skin diseases are a common reason for primary care visits, and one study suggested dermatologic diseases can make up approximately 8.4% of visits in primary care.17

Moreover, only 1% of medical schools require an elective in dermatology.18 With exposure being a crucial component to pursuing the specialty, it also is important to pursue formal mentorship within the specialty itself. One study noted that formal mentorship in dermatology was important for most (67%) respondents when considering the specialty; however, 39% of respondents mentioned receiving mentorship in the past. In fact, dermatology was one of the top 3 specialties for which respondents agreed that formal mentorship was important.19

Mentorship also has been shown to provide students with a variety of opportunities to develop personally and professionally. Some of these opportunities include increased confidence in their personal and professional success, increased desire to pursue a career in a field of interest, networking opportunities, career coaching, and support and research guidance.20 A research study among medical students at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York, New York, found that US Medical Licensing Examination Step 1 scores, clinical grades, and the chance of not matching were important factors preventing them from applying to dermatology.21

Factors in Dermatology Residency Selection—A survey was conducted wherein 95 of 114 dermatology program directors expressed that among the top 5 criteria for dermatology resident selection were Step 1 scores and clinical grades, supporting the notion that academic factors were given a great emphasis during residency selection.22 Furthermore, among underrepresented minority medical students, a lack of diversity, the belief that minority students are seen negatively by residencies, socioeconomic factors, and not having mentors were major reasons for being dissuaded from applying to dermatology.21 These results showcase the heightened importance of mentors for underrepresented minority medical students in particular.

In graduate medical education, resources such as wikis, social networking sites, and blogs provide media through which trainees can communicate, exchange ideas, and enhance their medical knowledge.23,24 A survey of 9606 osteopathic medical students showed that 35% of 992 respondents had used social media to learn more about residencies, and 10% believed that social media had influenced their choice of residency.25 Given the impact social media has on recruitment, it also can be employed in a similar manner by dermatologists and dermatology residency programs to attract younger students to the field.

Access to More Opportunities to Learn About Dermatology—Besides shadowing and mentorship, other avenues of exposure to dermatology are possible and should be considered. In our study, 80% of students agreed that they would attend an event that increases exposure to dermatology if held by the premedical group, which suggests that students are eager to learn more about the field and want access to more opportunities, which could include learning procedures such as suturing or how to use a dermatoscope, attending guest speaker events, or participating in Learn2Derm volunteer events.

Learn2Derm was a skin cancer prevention fair first organized by medical students at George Washington University in Washington, DC. Students and residents sought to deliver sunscreens to underserved areas in Washington, DC, as well as teach residents about the importance of skin health. Participating in such events could be an excellent opportunity for all students to gain exposure to important topics in dermatology.26

General Opinions of Dermatology—General opinions about dermatology and medicine were collected from the students through the optional “Additional Comments” section. Major themes found in the comments included the desire for more opportunities, mentorship, exposure, connections, and a discussion of disparities faced by Black patients/students within dermatology. Students also expressed an interest in dermatology and the desire to learn more about the specialty. From these themes, it can be gleaned that students are open to and eager for more opportunities to gain exposure and connections, and increasing the number of minority dermatologists is of importance.

Limitations—An important limitation of this study was the potential for selection bias, as the sample was chosen from a population at one university, which is not representative of the general population. Further, we only sampled students who were premedical and likely from a UiM racial group due to the demographics of the student population at the university, but given that the goal of the survey was to understand exposure to dermatology in underrepresented groups, we believe it was the appropriate population to target. Additionally, results were not compared with other more represented racial groups to see if these findings were unique to UiM undergraduate students.

Conclusion

Among premedical students, dermatology is an area of great interest with minimal opportunities available for exposure and learning because it is a smaller specialty with fewer experiences available for shadowing and mentorship. Although most UiM premedical students who were surveyed were exposed to the field through either the media or being a dermatology patient, fewer were exposed to the field through clinical experiences (such as shadowing) or mentorship. Most respondents found dermatology to be interesting and have considered pursuing it as a career. In particular, race-concordant mentoring in dermatologic care was valued by many students in garnering their interest in the field.

Most UiM students wanted more exposure to dermatology-related opportunities as well as mentorship and connections. Increasing shadowing, research, pipeline programs, and general events geared to dermatology are some modalities that could help improve exposure to dermatology for UiM students, especially for those interested in pursuing the field. This increased exposure can help positively influence more UiM students to pursue dermatology and help close the diversity gap in the field. Additionally, many were interested in attending potential dermatology informational events.

Given the fact that dermatology is a small field and mentorship may be hard to access, increasing informational events may be a more reasonable approach to inspiring and supporting interest. These events could include learning how to use certain tools and techniques, guest speaker events, or participating in educational volunteer efforts such as Learn2Derm.26

Future research should focus on identifying beneficial factors of UiM premedical students who retain an interest in dermatology throughout their careers and actually apply to dermatology programs and become dermatologists. Those who do not apply to the specialty can be identified to understand potential dissuading factors and obstacles. Ultimately, more research and development of exposure opportunities, including mentorship programs and informational events, can be used to close the gap and improve diversity and health outcomes in dermatology.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587.

- Bae G, Qiu M, Reese E, et al. Changes in sex and ethnic diversity in dermatology residents over multiple decades. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:92-94.

- McCleskey PE, Gilson RT, DeVillez RL. Medical student core curriculum in dermatology survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:30-35.e4.

- Pritchett EN, Pandya AG, Ferguson NN, et al. Diversity in dermatology: roadmap for improvement. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:337-341.

- National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: 2022 Main Residency Match. National Resident Matching Program; 2022. Accessed March 19, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/2022-Main-Match-Results-and-Data-Final-Revised.pdf

- 6. Akhiyat S, Cardwell L, Sokumbi O. Why dermatology is the second least diverse specialty in medicine: how did we get here? Clin Dermatol. 2020;38:310-315.

- Perlman KL, Williams NM, Egbeto IA, et al. Skin of color lacks representation in medical student resources: a cross-sectional study. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:195-196.

- Saad SM, Fatima SS, Faruqi AA. Students’ views regarding selecting medicine as a profession. J Pak Med Assoc. 2011;61:832-836.

- Woodward A, Thomas S, Jalloh M, et al. Reasons to pursue a career in medicine: a qualitative study in Sierra Leone. Global Health Res Policy. 2017;2:34.

- Thang C, Barnette NM, Patel KS, et al. Association of shadowing program for undergraduate premedical students with improvements in understanding medical education and training. Cureus. 2019;11:E6396.

- Murphy B. The 11 factors that influence med student specialty choice. American Medical Association. December 1, 2020. Accessed March 14, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org/residents-students/specialty-profiles/11-factors-influence-med-student-specialty-choice

- Vakayil V, Chandrashekar M, Hedberg J, et al. An undergraduate surgery interest group: introducing premedical students to the practice of surgery. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2020;13:339-349.

- 2021 Report on Residents Executive Summary. Association of American Medical Colleges; 2021. Accessed March 14, 2023. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/students-residents/data/report-residents/2021/executive-summary

- Johnson AL, Sharma J, Chinchilli VM, et al. Why do medical students choose orthopaedics as a career? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:e78.

- Feng H, Berk-Krauss J, Feng PW, et al. Comparison of dermatologist density between urban and rural counties in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1265-1271.

- Active Physicians With a U.S. Doctor of Medicine (U.S. MD) Degree by Specialty, 2019. Association of American Medical Colleges; 2019. Accessed March 14, 2023. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/active-physicians-us-doctor-medicine-us-md-degree-specialty-2019

- Rübsam ML, Esch M, Baum E, et al. Diagnosing skin disease in primary care: a qualitative study of GPs’ approaches. Fam Pract. 2015;32:591-595.

- Cahn BA, Harper HE, Halverstam CP, et al. Current status of dermatologic education in US medical schools. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:468-470.

- Mylona E, Brubaker L, Williams VN, et al. Does formal mentoring for faculty members matter? a survey of clinical faculty members. Med Educ. 2016;50:670-681.

- Ratnapalan S. Mentoring in medicine. Can Fam Physician. 2010;56:198.

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK, et al. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254.

- Gorouhi F, Alikhan A, Rezaei A, et al. Dermatology residency selection criteria with an emphasis on program characteristics: a national program director survey. Dermatol Res Pract. 2014;2014:692760.

- Choo EK, Ranney ML, Chan TM, et al. Twitter as a tool for communication and knowledge exchange in academic medicine: a guide for skeptics and novices. Med Teach. 2015;37:411-416.

- McGowan BS, Wasko M, Vartabedian BS, et al. Understanding the factors that influence the adoption and meaningful use of social media by physicians to share medical information. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14:e117.

- Schweitzer J, Hannan A, Coren J. The role of social networking web sites in influencing residency decisions. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2012;112:673-679.

- Medical students lead event addressing disparity in skin cancer morbidity and mortality. Dermatology News. August 19, 2021. Accessed March 14, 2023. https://www.mdedge.com/dermatology/article/244488/diversity-medicine/medical-students-lead-event-addressing-disparity-skin

Diversity of health care professionals improves medical outcomes and quality of life in patients. 1 There is a lack of diversity in dermatology, with only 4.2% of dermatologists identifying as Hispanic and 3% identifying as African American, 2 possibly due to a lack of early exposure to dermatology among high school and undergraduate students, a low number of underrepresented students in medical school, a lack of formal mentorship programs geared to underrepresented students, and implicit biases. 1-4 Furthermore, the field is competitive, with many more applicants than available positions. In 2022, there were 851 applicants competing for 492 residency positions in dermatology. 5 Thus, it is important to educate young students about dermatology and understand root causes as to why the number of u nderrepresented in medicine (UiM) dermatologists remains stagnant.

According to Pritchett et al,4 it is crucial for dermatologists to interact with high school and college students to foster an early interest in dermatology. Many racial minority students do not progress from high school to college and then from college to medical school, which leaves a substantially reduced number of eligible UiM applicants who can progress into dermatology.6 Increasing the amount of UiM students going to medical school requires early mediation. Collaborating with pre-existing premedical school organizations through presentations and workshops is another way to promote an early interest in dermatology.4 Special consideration should be given to students who are UiM.

Among the general medical school curriculum, requirements for exposure to dermatology are not high. In one study, the median number of clinical and preclinical hours required was 10. Furthermore, 20% of 33 medical schools did not require preclinical dermatology hours (hours done before medical school rotations begin and in an academic setting), 36% required no clinical hours (rotational hours), 8% required no dermatology hours whatsoever, and only 10% required clinical dermatology rotation.3 Based on these findings, it is clear that dermatology is not well incorporated into medical school curricula. Furthermore, curricula have historically neglected to display adequate representation of skin of color.7 As a result, medical students generally have limited exposure to dermatology3 and are exposed even less to presentations of dermatologic issues in historically marginalized populations.7

Given the paucity of research on UiM students’ perceptions of dermatology prior to medical school, our cross-sectional survey study sought to evaluate the level of interest in dermatology of UiM premedical undergraduates. This survey specifically evaluated exposure to dermatology, preconceived notions about the field, and mentorship opportunities. By understanding these factors, dermatologists and dermatology residency programs can use this information to create mentorship opportunities and better adjust existing programs to meet students’ needs.

Methods

A 19-question multiple-choice survey was administered electronically (SurveyMonkey) in May 2020 to premedical students at Howard University (Washington, DC). One screening question was used: “What is your major?” Those who considered themselves a science major and/or with premedical interest were allowed to complete the survey. All students surveyed were members of the Health Professions Society at Howard University. Students who were interested in pursuing medical school were invited to respond. Approval for this study was obtained from the Howard University institutional review board (FWA00000891).

The survey was divided into 3 sections: Demographics, Exposure to Medicine and Dermatology, and Perceptions of Dermatology. The Demographics section addressed gender, age, and race/ethnicity. The Exposure to Medicine and Dermatology section addressed interest in attending medical school, shadowing experience, exposure to dermatology, and mentoring. The Perceptions of Dermatology section addressed preconceived notions about the field (eg, “dermatology is interesting and exciting”).

Statistical Analysis—The data represented are percentages based on the number of respondents who answered each question. Answers in response to “Please enter any comments” were organized into themes, and the number of respondents who discussed each theme was quantified into a table.

Results

A total of 271 survey invitations were sent to premedical students at Howard University. Students were informed of the study protocol and asked to consent before proceeding to have their responses anonymously collected. Based on the screening question, 152 participants qualified for the survey, and 152 participants completed it (response rate, 56%; completion rate, 100%). Participants were asked to complete the survey only once.

Demographics—Eighty-four percent of respondents identified as science majors, and the remaining 16% identified as nonscience premedical. Ninety-four percent of participants identified as Black or African American; 3% as Asian or Asian American; and the remaining 3% as Other. Most respondents were female (82%), 16% were male, and 2% were either nonbinary or preferred not to answer. Ninety-nine percent were aged 18 to 24 years, and 1% were aged 25 to 34 years (Table 1).

Exposure to Medicine and Dermatology—Ninety-three percent of participants planned on attending medical school, and most students developed an interest in medicine from an early age. Ninety-six percent cited that they became interested in medicine prior to beginning their undergraduate education, and 4% developed an interest as freshmen or sophomores. When asked what led to their interest in medicine, family influence had the single greatest impact on students’ decision to pursue medicine (33%). Classes/school were the second most influential factor (24%), followed by volunteering (15%), shadowing (13%), other (7%), and peer influence (3%)(Figure 1).

Many (56%) premedical students surveyed had shadowing experience to varying degrees. Approximately 18% had fewer than 8 hours of shadowing experience, 24% had 8 to 40 hours, and 14% had more than 40 hours. However, many (43%) premedical students had no shadowing experience (Figure 2). Similarly, 30% of premedical students responded to having a physician as a mentor.

Regarding exposure to dermatology, 42% of premedical students had none. However, 58% of students had exposure to dermatology by being a patient themselves, 40% through seeing a dermatologist with a family member, 21% through seeing a dermatologist on television or social media, 5% through shadowing or volunteering, 3% through mentorship, and 1% through dermatology research (Figure 3).

Of students who said they were interested in dermatology (32%), 16% developed their interest before undergraduate education, while 9% developed interest in their freshman or sophomore year and 7% in their junior or senior year of undergraduate education. Three percent of respondents indicated that they had a dermatology mentorship.

Perceptions of Dermatology—To further evaluate the level of interest that UiM premedical students have in the field of dermatology, students were asked how much they agree or disagree on whether the field of dermatology is interesting. Sixty-three percent of the students agreed that the field of dermatology is interesting, 34% remained uncertain, and 3% disagreed. Additionally, students were asked whether they would consider dermatology as a career; 54% of respondents would consider dermatology as a career, 30% remained uncertain, and 16% would not consider dermatology as a career choice.

Nearly all (95%) students agreed that dermatologists do valuable work that goes beyond the scope of cosmetic procedures such as neuromodulators, fillers, chemical peels, and lasers. Some students also noted they had personal experiences interacting with a dermatologist. For example, one student described visiting the dermatologist many times to get a treatment regimen for their eczema.

Overall themes from the survey are depicted in Table 2. Major themes found in the comments included the desire for more dermatology-related opportunities, mentorship, exposure, connections, and a discussion of disparities faced by Black patients and students within dermatology. Students also expressed an interest in dermatology and the desire to learn more about the specialty.

Comment

Interest in Dermatology—In this cross-sectional survey study of 152 UiM undergraduate students, it was found that many students were interested in dermatology as a career, and more than 70% would be interested in attending events that increased exposure to the field of dermatology. Of the students who had any exposure to dermatology, less than 5% had shadowed an actual dermatologist. The survey showed that there is great potential interest in exposing UiM undergraduate students to the field of dermatology. We found that UiM students are interested in learning more about dermatology, with 80% indicating that they would be willing to participate in dermatology-focused events if they were available. Overall, students mentioned a lack of opportunities, mentorship, exposure, and connections in dermatology despite their interest in the field.

Racial Disparities in Dermatology—Additionally, students discussed disparities they encountered with dermatology due to a lack of patient-provider race concordance and the perceived difference in care when encountering a race-concordant dermatologist. One student noted that they went to multiple White dermatologists for their eczema, and “it wasn’t until I was evaluated by a Black dermatologist (diagnosed with eczema as well) [that I was] prescribed . . . the perfect medication.” Another student noted how a Black dermatologist sparked their interest in getting to know more about the field and remarked that they “think it is an important field that lacks representation for Black people.” This research stresses the need for more dermatology mentorship among UiM undergraduates.

Family Influence on Career Selection—The majority of UiM students in our study became interested in medicine because of family, which is consistent with other studies. In a cross-sectional survey of 300 Pakistani students (150 medical and 150 nonmedical), 87% of students stated that their family had an influence on their career selection.8 In another study of 15 junior doctors in Sierra Leone, the most common reasons for pursuing medicine were the desire to help and familial and peer influence.9 This again showcases how family can have a positive impact on career selection for medical professionals and highlights the need for early intervention.

Shadowing—One way in which student exposure to dermatology can be effectively increased is by shadowing. In a study evaluating a 30-week shadowing program at the Pediatric Continuity Clinic in Los Angeles, California, a greater proportion of premedical students believed they had a good understanding of the job of a resident physician after the program’s completion compared to before starting the program (an increase from 78% to 100%).10 The proportion of students reporting a good understanding of the patient-physician relationship after completing the program also increased from 33% to 78%. Furthermore, 72% of the residents stated that having the undergraduates in the clinic was a positive experience.10 Thus, increasing shadowing opportunities is one extremely effective way to increase student knowledge and awareness of and exposure to dermatology.

Dermatology Mentors—Although 32% of students were interested in dermatology, 3% of students had mentorship in dermatology. In prior studies, it has been shown that mentorship is of great importance in student success and interest in pursuing a specialty. A report from the Association of American Medical Colleges 2019 Medical School Graduation Questionnaire found that the third most influential factor (52.1%) in specialty selection was role model influence.11 In fact, having a role model is consistently one of the top 3 influences on student specialty choice and interest in the last 5 years of survey research. Some studies also have shown mentorship as a positive influence in specialty interest at the undergraduate and graduate levels. A study on an undergraduate student interest group noted that surgeon mentorship and exposure were positive factors to students’ interests in surgery.12 In fact, the Association of American Medical Colleges noted that some surgical specialties, such as orthopedic surgery, had 45% of respondents who were interested in the specialty before medical school pursue their initial preference in medical school.13 Another survey corroborated these findings; more orthopedic-bound students compared with other specialties indicated they were more likely to pursue their field because of experiences prior to medical school.14

One of the reasons students might not have been exposed to as many opportunities for mentorship in dermatology is because the specialty is one of the smaller fields in medicine and tends to be concentrated in more well-resourced metropolitan areas.15 Dermatologists make up only 1.3% of the physician workforce.16 Because there might not be as much exposure to the field, students might also explore their interests in dermatology through other fields, such as through shadowing and observing primary care physicians who often treat patients with dermatologic issues. Skin diseases are a common reason for primary care visits, and one study suggested dermatologic diseases can make up approximately 8.4% of visits in primary care.17

Moreover, only 1% of medical schools require an elective in dermatology.18 With exposure being a crucial component to pursuing the specialty, it also is important to pursue formal mentorship within the specialty itself. One study noted that formal mentorship in dermatology was important for most (67%) respondents when considering the specialty; however, 39% of respondents mentioned receiving mentorship in the past. In fact, dermatology was one of the top 3 specialties for which respondents agreed that formal mentorship was important.19

Mentorship also has been shown to provide students with a variety of opportunities to develop personally and professionally. Some of these opportunities include increased confidence in their personal and professional success, increased desire to pursue a career in a field of interest, networking opportunities, career coaching, and support and research guidance.20 A research study among medical students at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York, New York, found that US Medical Licensing Examination Step 1 scores, clinical grades, and the chance of not matching were important factors preventing them from applying to dermatology.21

Factors in Dermatology Residency Selection—A survey was conducted wherein 95 of 114 dermatology program directors expressed that among the top 5 criteria for dermatology resident selection were Step 1 scores and clinical grades, supporting the notion that academic factors were given a great emphasis during residency selection.22 Furthermore, among underrepresented minority medical students, a lack of diversity, the belief that minority students are seen negatively by residencies, socioeconomic factors, and not having mentors were major reasons for being dissuaded from applying to dermatology.21 These results showcase the heightened importance of mentors for underrepresented minority medical students in particular.

In graduate medical education, resources such as wikis, social networking sites, and blogs provide media through which trainees can communicate, exchange ideas, and enhance their medical knowledge.23,24 A survey of 9606 osteopathic medical students showed that 35% of 992 respondents had used social media to learn more about residencies, and 10% believed that social media had influenced their choice of residency.25 Given the impact social media has on recruitment, it also can be employed in a similar manner by dermatologists and dermatology residency programs to attract younger students to the field.

Access to More Opportunities to Learn About Dermatology—Besides shadowing and mentorship, other avenues of exposure to dermatology are possible and should be considered. In our study, 80% of students agreed that they would attend an event that increases exposure to dermatology if held by the premedical group, which suggests that students are eager to learn more about the field and want access to more opportunities, which could include learning procedures such as suturing or how to use a dermatoscope, attending guest speaker events, or participating in Learn2Derm volunteer events.

Learn2Derm was a skin cancer prevention fair first organized by medical students at George Washington University in Washington, DC. Students and residents sought to deliver sunscreens to underserved areas in Washington, DC, as well as teach residents about the importance of skin health. Participating in such events could be an excellent opportunity for all students to gain exposure to important topics in dermatology.26

General Opinions of Dermatology—General opinions about dermatology and medicine were collected from the students through the optional “Additional Comments” section. Major themes found in the comments included the desire for more opportunities, mentorship, exposure, connections, and a discussion of disparities faced by Black patients/students within dermatology. Students also expressed an interest in dermatology and the desire to learn more about the specialty. From these themes, it can be gleaned that students are open to and eager for more opportunities to gain exposure and connections, and increasing the number of minority dermatologists is of importance.

Limitations—An important limitation of this study was the potential for selection bias, as the sample was chosen from a population at one university, which is not representative of the general population. Further, we only sampled students who were premedical and likely from a UiM racial group due to the demographics of the student population at the university, but given that the goal of the survey was to understand exposure to dermatology in underrepresented groups, we believe it was the appropriate population to target. Additionally, results were not compared with other more represented racial groups to see if these findings were unique to UiM undergraduate students.

Conclusion

Among premedical students, dermatology is an area of great interest with minimal opportunities available for exposure and learning because it is a smaller specialty with fewer experiences available for shadowing and mentorship. Although most UiM premedical students who were surveyed were exposed to the field through either the media or being a dermatology patient, fewer were exposed to the field through clinical experiences (such as shadowing) or mentorship. Most respondents found dermatology to be interesting and have considered pursuing it as a career. In particular, race-concordant mentoring in dermatologic care was valued by many students in garnering their interest in the field.

Most UiM students wanted more exposure to dermatology-related opportunities as well as mentorship and connections. Increasing shadowing, research, pipeline programs, and general events geared to dermatology are some modalities that could help improve exposure to dermatology for UiM students, especially for those interested in pursuing the field. This increased exposure can help positively influence more UiM students to pursue dermatology and help close the diversity gap in the field. Additionally, many were interested in attending potential dermatology informational events.

Given the fact that dermatology is a small field and mentorship may be hard to access, increasing informational events may be a more reasonable approach to inspiring and supporting interest. These events could include learning how to use certain tools and techniques, guest speaker events, or participating in educational volunteer efforts such as Learn2Derm.26

Future research should focus on identifying beneficial factors of UiM premedical students who retain an interest in dermatology throughout their careers and actually apply to dermatology programs and become dermatologists. Those who do not apply to the specialty can be identified to understand potential dissuading factors and obstacles. Ultimately, more research and development of exposure opportunities, including mentorship programs and informational events, can be used to close the gap and improve diversity and health outcomes in dermatology.

Diversity of health care professionals improves medical outcomes and quality of life in patients. 1 There is a lack of diversity in dermatology, with only 4.2% of dermatologists identifying as Hispanic and 3% identifying as African American, 2 possibly due to a lack of early exposure to dermatology among high school and undergraduate students, a low number of underrepresented students in medical school, a lack of formal mentorship programs geared to underrepresented students, and implicit biases. 1-4 Furthermore, the field is competitive, with many more applicants than available positions. In 2022, there were 851 applicants competing for 492 residency positions in dermatology. 5 Thus, it is important to educate young students about dermatology and understand root causes as to why the number of u nderrepresented in medicine (UiM) dermatologists remains stagnant.

According to Pritchett et al,4 it is crucial for dermatologists to interact with high school and college students to foster an early interest in dermatology. Many racial minority students do not progress from high school to college and then from college to medical school, which leaves a substantially reduced number of eligible UiM applicants who can progress into dermatology.6 Increasing the amount of UiM students going to medical school requires early mediation. Collaborating with pre-existing premedical school organizations through presentations and workshops is another way to promote an early interest in dermatology.4 Special consideration should be given to students who are UiM.

Among the general medical school curriculum, requirements for exposure to dermatology are not high. In one study, the median number of clinical and preclinical hours required was 10. Furthermore, 20% of 33 medical schools did not require preclinical dermatology hours (hours done before medical school rotations begin and in an academic setting), 36% required no clinical hours (rotational hours), 8% required no dermatology hours whatsoever, and only 10% required clinical dermatology rotation.3 Based on these findings, it is clear that dermatology is not well incorporated into medical school curricula. Furthermore, curricula have historically neglected to display adequate representation of skin of color.7 As a result, medical students generally have limited exposure to dermatology3 and are exposed even less to presentations of dermatologic issues in historically marginalized populations.7

Given the paucity of research on UiM students’ perceptions of dermatology prior to medical school, our cross-sectional survey study sought to evaluate the level of interest in dermatology of UiM premedical undergraduates. This survey specifically evaluated exposure to dermatology, preconceived notions about the field, and mentorship opportunities. By understanding these factors, dermatologists and dermatology residency programs can use this information to create mentorship opportunities and better adjust existing programs to meet students’ needs.

Methods

A 19-question multiple-choice survey was administered electronically (SurveyMonkey) in May 2020 to premedical students at Howard University (Washington, DC). One screening question was used: “What is your major?” Those who considered themselves a science major and/or with premedical interest were allowed to complete the survey. All students surveyed were members of the Health Professions Society at Howard University. Students who were interested in pursuing medical school were invited to respond. Approval for this study was obtained from the Howard University institutional review board (FWA00000891).

The survey was divided into 3 sections: Demographics, Exposure to Medicine and Dermatology, and Perceptions of Dermatology. The Demographics section addressed gender, age, and race/ethnicity. The Exposure to Medicine and Dermatology section addressed interest in attending medical school, shadowing experience, exposure to dermatology, and mentoring. The Perceptions of Dermatology section addressed preconceived notions about the field (eg, “dermatology is interesting and exciting”).

Statistical Analysis—The data represented are percentages based on the number of respondents who answered each question. Answers in response to “Please enter any comments” were organized into themes, and the number of respondents who discussed each theme was quantified into a table.

Results

A total of 271 survey invitations were sent to premedical students at Howard University. Students were informed of the study protocol and asked to consent before proceeding to have their responses anonymously collected. Based on the screening question, 152 participants qualified for the survey, and 152 participants completed it (response rate, 56%; completion rate, 100%). Participants were asked to complete the survey only once.

Demographics—Eighty-four percent of respondents identified as science majors, and the remaining 16% identified as nonscience premedical. Ninety-four percent of participants identified as Black or African American; 3% as Asian or Asian American; and the remaining 3% as Other. Most respondents were female (82%), 16% were male, and 2% were either nonbinary or preferred not to answer. Ninety-nine percent were aged 18 to 24 years, and 1% were aged 25 to 34 years (Table 1).

Exposure to Medicine and Dermatology—Ninety-three percent of participants planned on attending medical school, and most students developed an interest in medicine from an early age. Ninety-six percent cited that they became interested in medicine prior to beginning their undergraduate education, and 4% developed an interest as freshmen or sophomores. When asked what led to their interest in medicine, family influence had the single greatest impact on students’ decision to pursue medicine (33%). Classes/school were the second most influential factor (24%), followed by volunteering (15%), shadowing (13%), other (7%), and peer influence (3%)(Figure 1).

Many (56%) premedical students surveyed had shadowing experience to varying degrees. Approximately 18% had fewer than 8 hours of shadowing experience, 24% had 8 to 40 hours, and 14% had more than 40 hours. However, many (43%) premedical students had no shadowing experience (Figure 2). Similarly, 30% of premedical students responded to having a physician as a mentor.

Regarding exposure to dermatology, 42% of premedical students had none. However, 58% of students had exposure to dermatology by being a patient themselves, 40% through seeing a dermatologist with a family member, 21% through seeing a dermatologist on television or social media, 5% through shadowing or volunteering, 3% through mentorship, and 1% through dermatology research (Figure 3).

Of students who said they were interested in dermatology (32%), 16% developed their interest before undergraduate education, while 9% developed interest in their freshman or sophomore year and 7% in their junior or senior year of undergraduate education. Three percent of respondents indicated that they had a dermatology mentorship.

Perceptions of Dermatology—To further evaluate the level of interest that UiM premedical students have in the field of dermatology, students were asked how much they agree or disagree on whether the field of dermatology is interesting. Sixty-three percent of the students agreed that the field of dermatology is interesting, 34% remained uncertain, and 3% disagreed. Additionally, students were asked whether they would consider dermatology as a career; 54% of respondents would consider dermatology as a career, 30% remained uncertain, and 16% would not consider dermatology as a career choice.

Nearly all (95%) students agreed that dermatologists do valuable work that goes beyond the scope of cosmetic procedures such as neuromodulators, fillers, chemical peels, and lasers. Some students also noted they had personal experiences interacting with a dermatologist. For example, one student described visiting the dermatologist many times to get a treatment regimen for their eczema.

Overall themes from the survey are depicted in Table 2. Major themes found in the comments included the desire for more dermatology-related opportunities, mentorship, exposure, connections, and a discussion of disparities faced by Black patients and students within dermatology. Students also expressed an interest in dermatology and the desire to learn more about the specialty.

Comment

Interest in Dermatology—In this cross-sectional survey study of 152 UiM undergraduate students, it was found that many students were interested in dermatology as a career, and more than 70% would be interested in attending events that increased exposure to the field of dermatology. Of the students who had any exposure to dermatology, less than 5% had shadowed an actual dermatologist. The survey showed that there is great potential interest in exposing UiM undergraduate students to the field of dermatology. We found that UiM students are interested in learning more about dermatology, with 80% indicating that they would be willing to participate in dermatology-focused events if they were available. Overall, students mentioned a lack of opportunities, mentorship, exposure, and connections in dermatology despite their interest in the field.