User login

The importance of understanding disparities in IBD

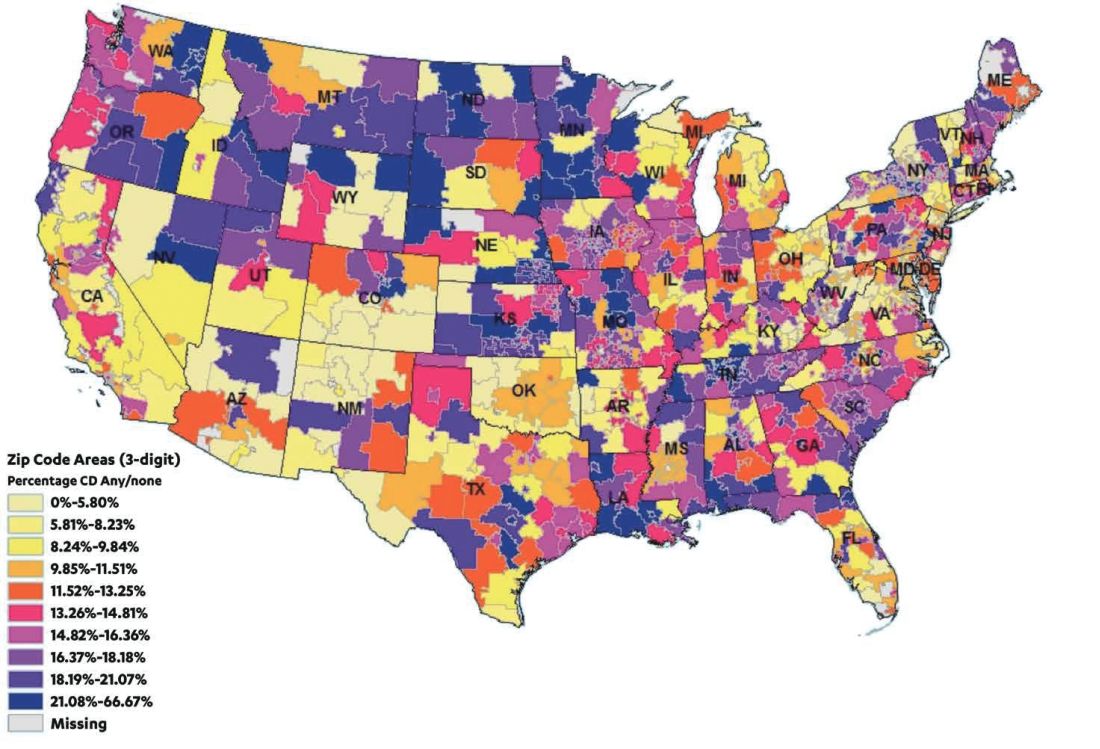

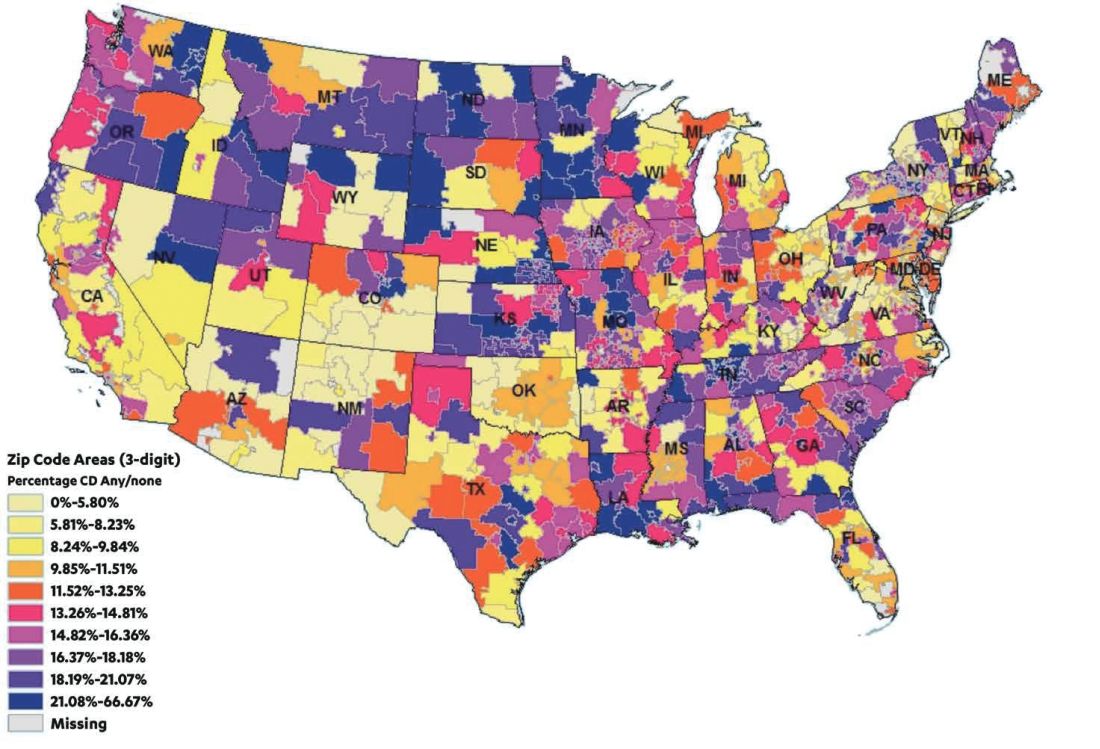

Assessing how race and other characteristics may impact the presentation and outcomes of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a powerful method for understanding the basic underpinnings of IBD (microbiome, environmental, immune, and genetic). Yet, exclusively viewing race with this biologic lens leaves out another critical explanation for potential differences in IBD presentation and outcomes, which is health disparities.

Health disparities are a specific type of health difference, linked with economic, social, or environmental disadvantages and in groups traditionally subjected to discrimination, exclusion, or disadvantages. These social determinants of health can, many times, have an even greater effect on disease presentation and outcomes than biological determinants. In the field of IBD, racial disparities are an underrecognized and understudied area. Yet what we do know is enough to demonstrate that critical disparities in IBD exist and that additional study and action are needed.

For example, surgery is more common in African Americans and Hispanics compared to Whites with IBD.1 Despite these findings, African Americans and Hispanics tend to have low use of biologics early in the disease course. Surgical outcomes are also worse in African Americans and Hispanics, who experience increased morbidity, mortality, and readmission after surgery.2

While the above outcomes may be attributable to inherent biologic differences, disparities quite likely have an important role. African Americans for example are less likely to see a GI or IBD specialist, more likely use the emergency room for their IBD care, and more likely to delay health visits because of transportation and financial issues. Non-Whites are more often seen in low–IBD volume hospitals, which can affect surgical outcomes. African Americans and Hispanics more often have reduced health literacy, which could affect their confidence and understanding in starting biologic therapy.

Fortunately, understanding and eliminating disparities in IBD is increasingly recognized as a priority area for research and action by the AGA and funding societies. We can do our part in many ways. We can immediately impact what is in our control right now (asking patients what economic and social barriers they may have to accessing care). We can advocate where we may not have direct control (policies that improve health access and social determinants of health). Finally, we can better understand and study social determinants of health in our research to get a more complete picture of how health disparities affect IBD presentation and outcomes.

Dr. Velayos is chief of gastroenterology at San Francisco Medical Center of the Permanente Medical Group, regional lead for inflammatory bowel disease for Northern California Kaiser Permanente, and chair of the immunology, microbiology, and inflammatory bowel disease section for the American Gastroenterological Association. He has no relevant conflicts to declare. Dr. Velayos made these comments during the AGA Institute Presidential Plenary at the annual Digestive Disease Week®.

References

1. Shi HY et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Feb;16(2):190-7.

2. Booth A et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021 Sep 23. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izab237.

Assessing how race and other characteristics may impact the presentation and outcomes of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a powerful method for understanding the basic underpinnings of IBD (microbiome, environmental, immune, and genetic). Yet, exclusively viewing race with this biologic lens leaves out another critical explanation for potential differences in IBD presentation and outcomes, which is health disparities.

Health disparities are a specific type of health difference, linked with economic, social, or environmental disadvantages and in groups traditionally subjected to discrimination, exclusion, or disadvantages. These social determinants of health can, many times, have an even greater effect on disease presentation and outcomes than biological determinants. In the field of IBD, racial disparities are an underrecognized and understudied area. Yet what we do know is enough to demonstrate that critical disparities in IBD exist and that additional study and action are needed.

For example, surgery is more common in African Americans and Hispanics compared to Whites with IBD.1 Despite these findings, African Americans and Hispanics tend to have low use of biologics early in the disease course. Surgical outcomes are also worse in African Americans and Hispanics, who experience increased morbidity, mortality, and readmission after surgery.2

While the above outcomes may be attributable to inherent biologic differences, disparities quite likely have an important role. African Americans for example are less likely to see a GI or IBD specialist, more likely use the emergency room for their IBD care, and more likely to delay health visits because of transportation and financial issues. Non-Whites are more often seen in low–IBD volume hospitals, which can affect surgical outcomes. African Americans and Hispanics more often have reduced health literacy, which could affect their confidence and understanding in starting biologic therapy.

Fortunately, understanding and eliminating disparities in IBD is increasingly recognized as a priority area for research and action by the AGA and funding societies. We can do our part in many ways. We can immediately impact what is in our control right now (asking patients what economic and social barriers they may have to accessing care). We can advocate where we may not have direct control (policies that improve health access and social determinants of health). Finally, we can better understand and study social determinants of health in our research to get a more complete picture of how health disparities affect IBD presentation and outcomes.

Dr. Velayos is chief of gastroenterology at San Francisco Medical Center of the Permanente Medical Group, regional lead for inflammatory bowel disease for Northern California Kaiser Permanente, and chair of the immunology, microbiology, and inflammatory bowel disease section for the American Gastroenterological Association. He has no relevant conflicts to declare. Dr. Velayos made these comments during the AGA Institute Presidential Plenary at the annual Digestive Disease Week®.

References

1. Shi HY et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Feb;16(2):190-7.

2. Booth A et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021 Sep 23. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izab237.

Assessing how race and other characteristics may impact the presentation and outcomes of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a powerful method for understanding the basic underpinnings of IBD (microbiome, environmental, immune, and genetic). Yet, exclusively viewing race with this biologic lens leaves out another critical explanation for potential differences in IBD presentation and outcomes, which is health disparities.

Health disparities are a specific type of health difference, linked with economic, social, or environmental disadvantages and in groups traditionally subjected to discrimination, exclusion, or disadvantages. These social determinants of health can, many times, have an even greater effect on disease presentation and outcomes than biological determinants. In the field of IBD, racial disparities are an underrecognized and understudied area. Yet what we do know is enough to demonstrate that critical disparities in IBD exist and that additional study and action are needed.

For example, surgery is more common in African Americans and Hispanics compared to Whites with IBD.1 Despite these findings, African Americans and Hispanics tend to have low use of biologics early in the disease course. Surgical outcomes are also worse in African Americans and Hispanics, who experience increased morbidity, mortality, and readmission after surgery.2

While the above outcomes may be attributable to inherent biologic differences, disparities quite likely have an important role. African Americans for example are less likely to see a GI or IBD specialist, more likely use the emergency room for their IBD care, and more likely to delay health visits because of transportation and financial issues. Non-Whites are more often seen in low–IBD volume hospitals, which can affect surgical outcomes. African Americans and Hispanics more often have reduced health literacy, which could affect their confidence and understanding in starting biologic therapy.

Fortunately, understanding and eliminating disparities in IBD is increasingly recognized as a priority area for research and action by the AGA and funding societies. We can do our part in many ways. We can immediately impact what is in our control right now (asking patients what economic and social barriers they may have to accessing care). We can advocate where we may not have direct control (policies that improve health access and social determinants of health). Finally, we can better understand and study social determinants of health in our research to get a more complete picture of how health disparities affect IBD presentation and outcomes.

Dr. Velayos is chief of gastroenterology at San Francisco Medical Center of the Permanente Medical Group, regional lead for inflammatory bowel disease for Northern California Kaiser Permanente, and chair of the immunology, microbiology, and inflammatory bowel disease section for the American Gastroenterological Association. He has no relevant conflicts to declare. Dr. Velayos made these comments during the AGA Institute Presidential Plenary at the annual Digestive Disease Week®.

References

1. Shi HY et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Feb;16(2):190-7.

2. Booth A et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021 Sep 23. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izab237.

The Vanishing Tide: As MACRA Moves In, IBD Quality Measures Move Out

Your next patient is a 67-year-old Medicare beneficiary with corticosteroid-dependent ulcerative colitis. Despite 4 months of maximally dosed mesalamine, his colitis flares with prednisone taper below 20 mg daily. Hepatitis B serologies and tuberculin skin test were negative 10 months ago. Which of the following do you recommend?

A. Steroid-sparing therapy initiation

B. Repeat latent tuberculosis screening in anticipation of anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy

C. Bone loss assessment

D. Pneumococcal vaccination

E. Tobacco use screening

Quality measure reporting is a costly undertaking, with medical practices spending an average of 15.1 hours per physician per week ($40,069 per physician annually) dealing with external quality measures.2 How did this expensive alphabet soup of quality measure reporting arise and how does it impact inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) care?

Why are IBD quality measures needed?

What makes a good quality measure?

Quality must be defined and measured before it can be improved. This is easier said than done, especially for IBD where a gold standard in “ideal care” is ill defined and continually evolving as new research emerges. Nonetheless, hundreds of health care quality measures have been proposed. Desirable quality measure attributes should satisfy three broad categories: importance, scientific soundness, and feasibility.10 Quality measures should address relevant and important aspects of health that are highly prevalent and for which evidence indicates a need for improvement. There should be strong evidence supporting the beneficial impact of adhering to a given measure.

Quality measures are commonly classified as process measures or outcome measures. Process measures (“doing the right thing”) are steps taken by providers in the care of an individual patient. These often derive from evidence-based best practices. Outcome measures (“having the desired result”) identify what happens to patients as a result of care received.8 Outcome measures may be more meaningful, but there are limitations in using them to study quality of IBD care. For example, factors beyond physician control affect patient outcomes and long delays may exist between care decisions and subsequent outcomes (e.g., surgery, malnutrition).8

What IBD quality measures already exist?

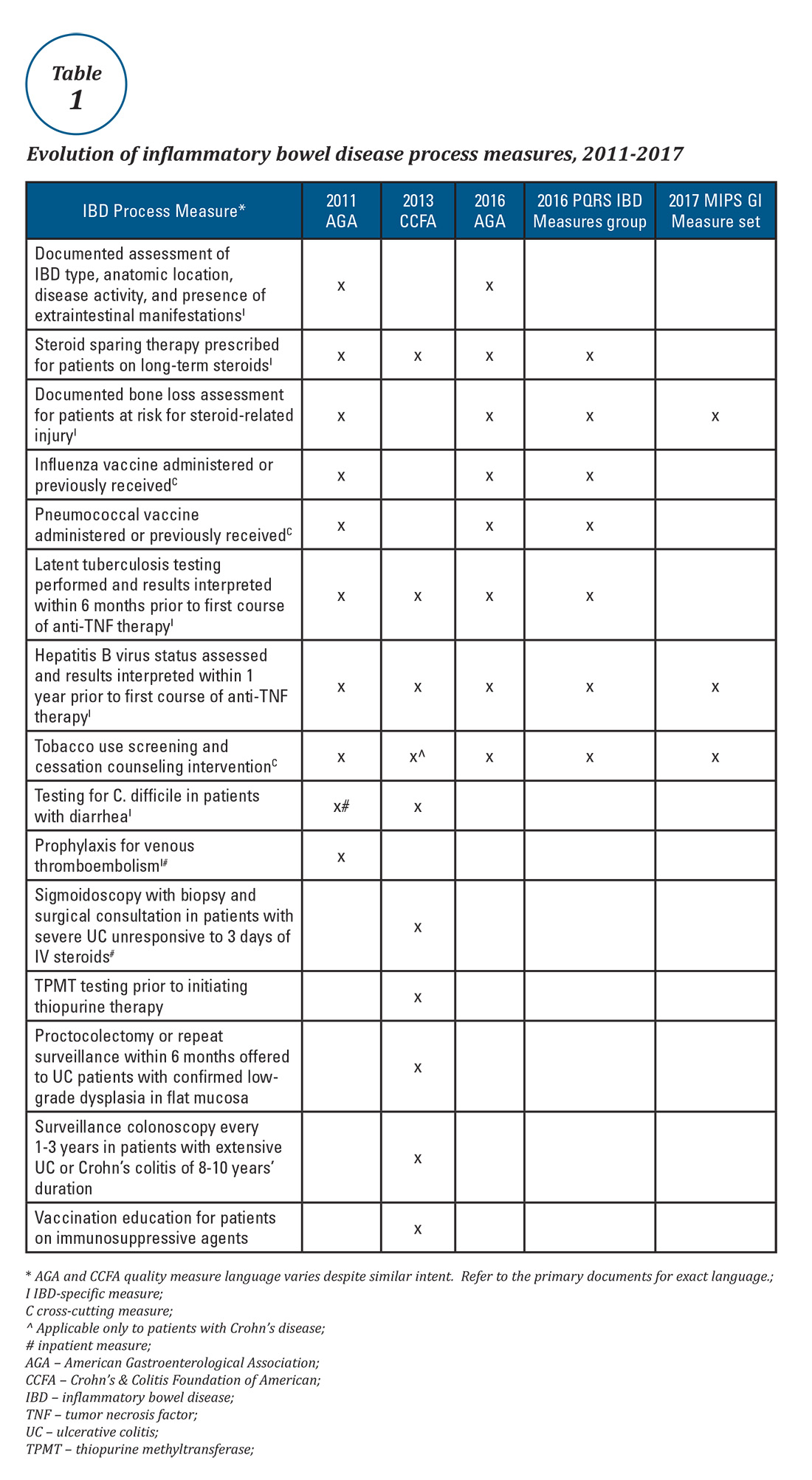

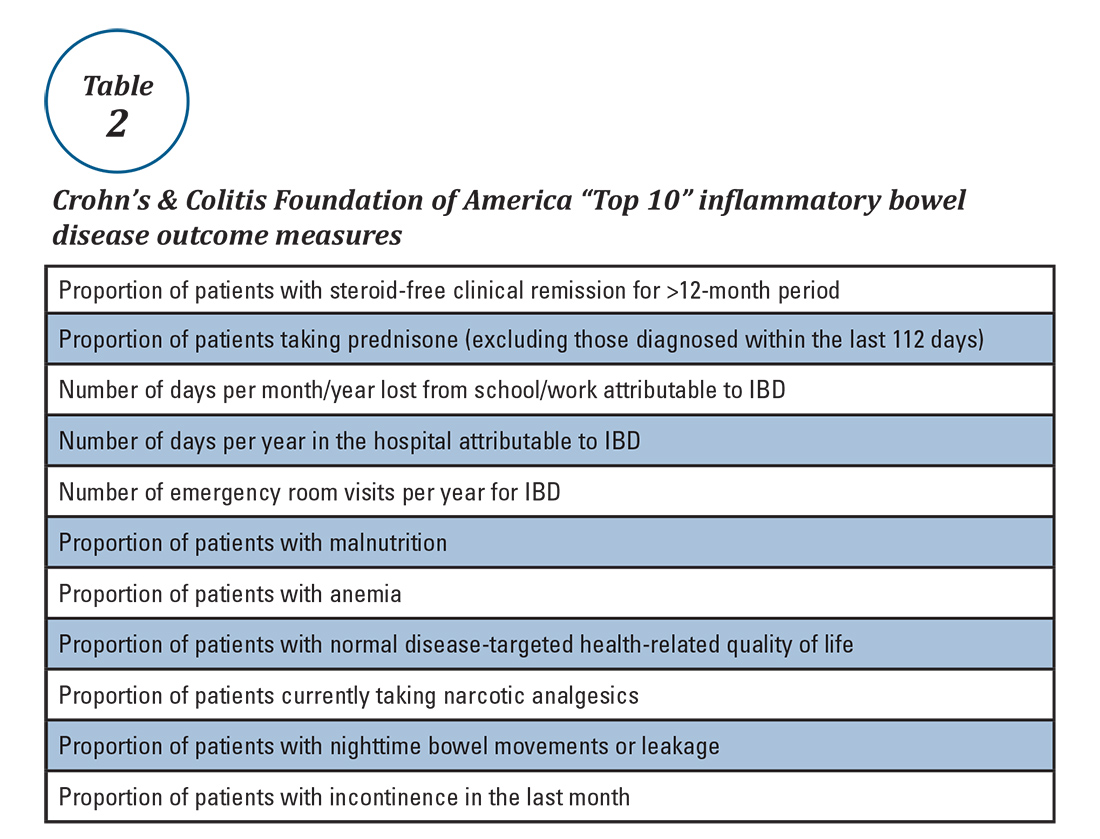

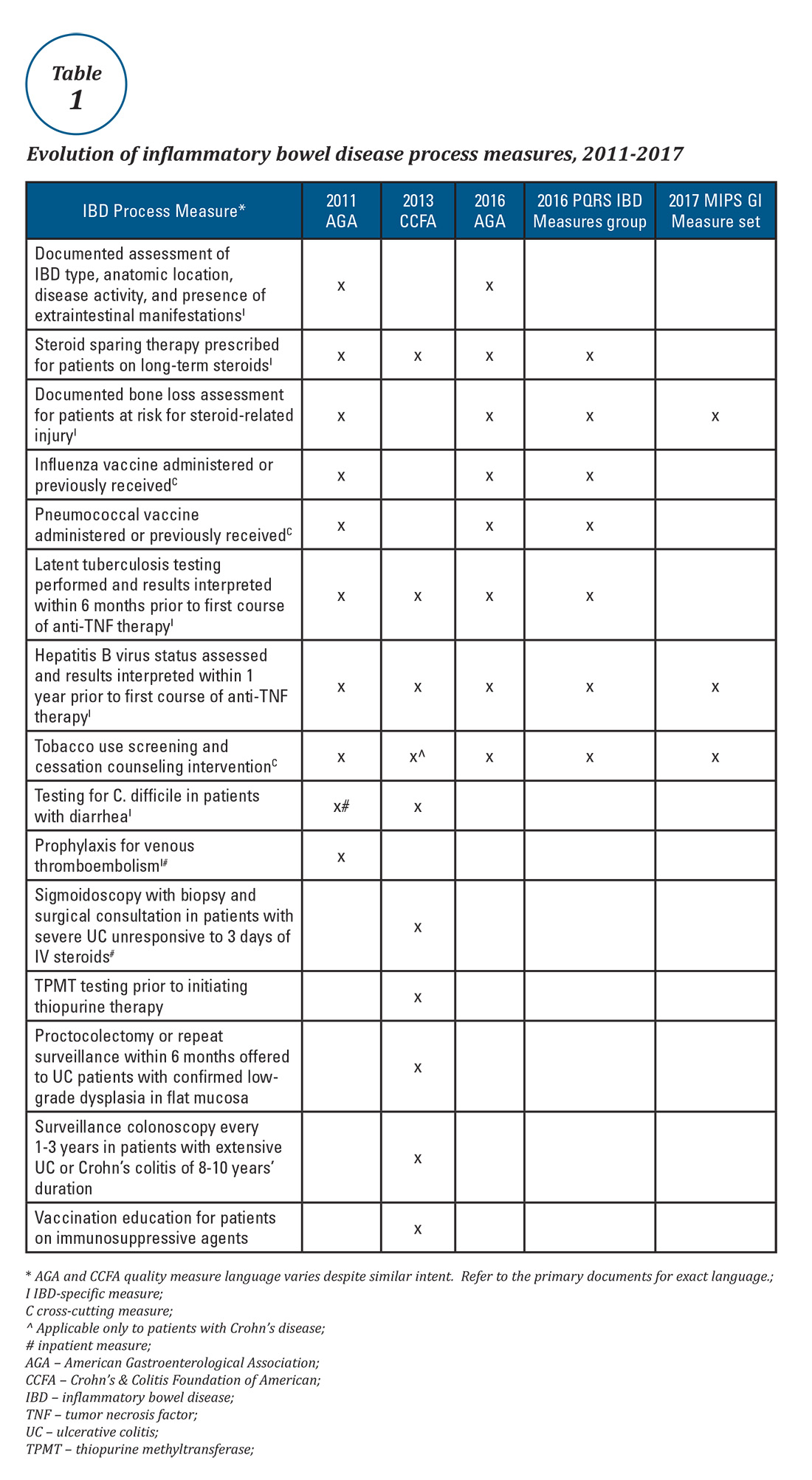

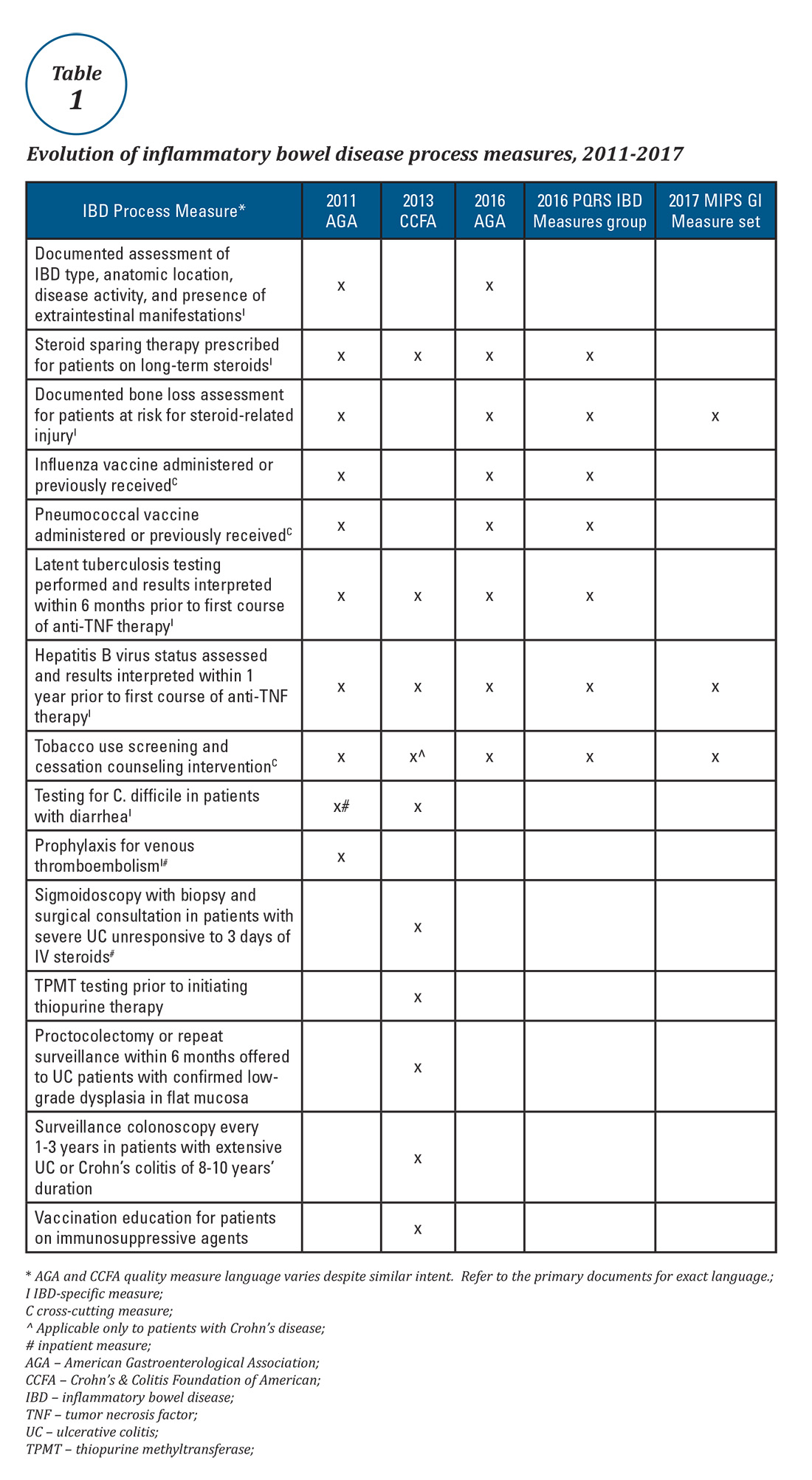

Expert panels from the AGA and the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America (CCFA) produced IBD quality measure sets comprising mostly process measures (Table 1). The original 10 AGA measures released in 2011 address aspects of disease assessment, treatment, complication prevention, and health care maintenance.12 They include seven IBD-specific measures, three cross-cutting measures – defined by Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) as being broadly applicable across multiple clinical settings – and two inpatient measures. A major goal of the AGA measures was to facilitate quality reporting to the former PQRS program.

What are some quality measure limitations?

Quality measure development has an evidence base but designing an optimal measure and demonstrating impact can be challenging. Few IBD process measures are validated and thus there is often logic but not data linking process measure adherence to improved outcomes. The denominator (number of eligible patients) and potential impact of broad adherence vary for each quality measure. For example, only a small fraction of IBD patients are infected with hepatitis B and fewer than 10% will experience viral reactivation during anti-TNF therapy.17,18 Even with optimal adherence to the hepatitis B measure, few reactivations will be prevented. The wording of some measures lacks precision, allowing physicians to potentially claim credit without improving care. For example, ordering a bone density scan satisfies the bone loss assessment measure, even if osteoporosis goes unrecognized and untreated. Finally, some measures relate to actions that may not be under the control of the gastroenterologist whose performance is being measured (e.g., administering vaccinations).

IBD quality measures under MIPS

Table 1 depicts the evolution of IBD process measures from 2011 to 2017. Rather than building upon initial experience to revise and refine IBD quality measures, the measures have instead been progressively culled with the changing pay-for-performance landscape. In 2016, AGA eliminated the two inpatient measures.19 Seven of the remaining eight measures formed the IBD Measures Group which was reportable under PQRS. In 2017, MIPS brought a seismic shift in quality measure focus. The PQRS IBD Measures Group was abolished – as were all Measures Groups – and replaced by a 16-item GI Measures Set. Although AGA advocated for all of the IBD measures to be included, the new GI Measures Set deemphasized the IBD-specific measures in favor of expanded cross-cutting measures (e.g., screening for abnormal body mass index, documenting current medications, sending specialist report to referring provider).20 This reflected a previously observed trend that gastroenterologists more often reported on cross-cutting measures than specialist-specific measures.21 However, there was no evidence-based justification for dropping certain IBD-specific measures (especially the steroid-sparing therapy measure) in favor of retaining the two chosen IBD-specific measures – bone loss assessment and hepatitis B screening – which apply to only a subset of IBD patients and have limited potential to impact clinical outcomes. Although it is not mandatory to report using the GI Measures Set, we suspect that many gastroenterologists will use this set to guide their initial reporting.

There are formidable regulatory obstacles to improving the IBD quality measures included in MIPS. CMS requires that new quality measures proposed for inclusion in MIPS be fully specified and tested for validity and reliability by the individual measure developers (such as AGA). This is a costly and time-intensive process that has complicated efforts to successfully advocate for inclusion of GI-specific quality measures in MIPS, as there is no existing infrastructure for quality measure testing.

A word about Alternative Payment Models (APMs)

APMs represent the non-MIPS pathway for participating in the QPP. APMs focus on chronic disease care coordination and qualify for lump-sum incentive payments by adhering to stringent standards and financial risk-sharing requirements. A detailed overview of APMs is beyond the scope of this discussion, as the vast majority of MACRA-eligible gastroenterologists will participate in MIPS and there are currently no GI-specific APMs. However, this is an evolving area and Project Sonar has been submitted to the Physician-Focused Payment Model Technical Advisory Committee for consideration as an APM for Crohn’s disease.23

Conclusion

Quality measurement and reporting are at a crossroads. Ideally, performance improvement should be an internally driven process that addresses specific local priorities and needs. Most medical practices (73%) believe that current externally driven quality measures do not represent care quality and only 28% use their quality scores to focus their internal quality improvement activities.2 The burden and cost of external quality reporting demand better alignment with local priorities as resources are currently being diverted away from internally driven efforts that might have the greatest potential to improve patient outcomes.24 The dawn of the MACRA era presents an opportunity to shape the future of the IBD quality movement. Through validating and prioritizing existing measures and developing novel, precisely stated, and high-value metrics, there remains vast (and measurable) potential to enhance patient outcomes.

Dr. McConnell is a fellow in gastroenterology and advanced inflammatory bowel disease, division of gastroenterology, University of California, San Francisco. Dr. Velayos is professor of medicine, co–medical director, Center for Crohn’s and Colitis, University of California, San Francisco.

References

1. September 2016 Medscape survey summary. Available at http://www.healthcaredive.com/news/survey-29-of-physicians-still-havent-heard-of-macra/429322/. Accessed March 23, 2017.

2. Casalino L.P., et al. Health Aff. 2016;35:401-6.

3. Rubin D.T., et al. Curr Med Res Opin. 2017;33:529-36.

4. David G., et al. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:S-647.

5. Nguyen G.C., et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1507-13.

6. Esrailian E., et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:1005-18.

7. Spiegel B.M., et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:68-74.

8. Kappelman M.D., et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:125-133.

9. Reddy S.I., et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1357-61.

10. National Quality Measures Clearinghouse. Available at https://www.qualitymeasures.ahrq.gov/help-and-about/quality-measure-tutorials/desirable-attributes-of-a-quality-measure. Accessed March 23, 2017.

11. McGlynn E.A. Med Care. 2003;41(1 Suppl):139-47.

12. American Gastroenterological Association. Available at https://www.gastro.org/practice/quality-initiatives/IBD_Measures.pdf. Accessed March 23, 2017.

13. Melmed G.Y., et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:662-8.

14. Feuerstein J.D., et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:421-8.

15. Sapir T., et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61:1862-9.

16. Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America. IBD Qorus. Available at http://www.ccfa.org/science-and-professionals/ibdqorus/. Accessed March 23, 2017.

17. Hou J.K., et al. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(Suppl 1):S-61.

18. Reddy K.R., et al. Gastroenterology. 2015;48:215-9.

19. American Gastroenterological Association. Available at http://www.gastro.org/practice-management/measures/2016_AGA_Measures_-_IBD.pdf. Accessed March 23, 2017.

20. American Gastroenterological Association. Available at http://www.gastro.org/news_items/gi-quality-measures-for-2017-are-released-in-macra-final-rule. Accessed March 23, 2017.

21. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Available at https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/PQRS/Downloads/2014_PQRS_Experience_Rpt.pdf. Accessed March 23, 2017.

22. Dahlhamer J.M., et al. MMWR. 2016;65:1166-9.

23. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. Available at https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/253406/ProjectSonarSonarMD.pdf. Accessed March 23, 2017.

24. Meyer G.S., et al. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21:964-8.

Your next patient is a 67-year-old Medicare beneficiary with corticosteroid-dependent ulcerative colitis. Despite 4 months of maximally dosed mesalamine, his colitis flares with prednisone taper below 20 mg daily. Hepatitis B serologies and tuberculin skin test were negative 10 months ago. Which of the following do you recommend?

A. Steroid-sparing therapy initiation

B. Repeat latent tuberculosis screening in anticipation of anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy

C. Bone loss assessment

D. Pneumococcal vaccination

E. Tobacco use screening

Quality measure reporting is a costly undertaking, with medical practices spending an average of 15.1 hours per physician per week ($40,069 per physician annually) dealing with external quality measures.2 How did this expensive alphabet soup of quality measure reporting arise and how does it impact inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) care?

Why are IBD quality measures needed?

What makes a good quality measure?

Quality must be defined and measured before it can be improved. This is easier said than done, especially for IBD where a gold standard in “ideal care” is ill defined and continually evolving as new research emerges. Nonetheless, hundreds of health care quality measures have been proposed. Desirable quality measure attributes should satisfy three broad categories: importance, scientific soundness, and feasibility.10 Quality measures should address relevant and important aspects of health that are highly prevalent and for which evidence indicates a need for improvement. There should be strong evidence supporting the beneficial impact of adhering to a given measure.

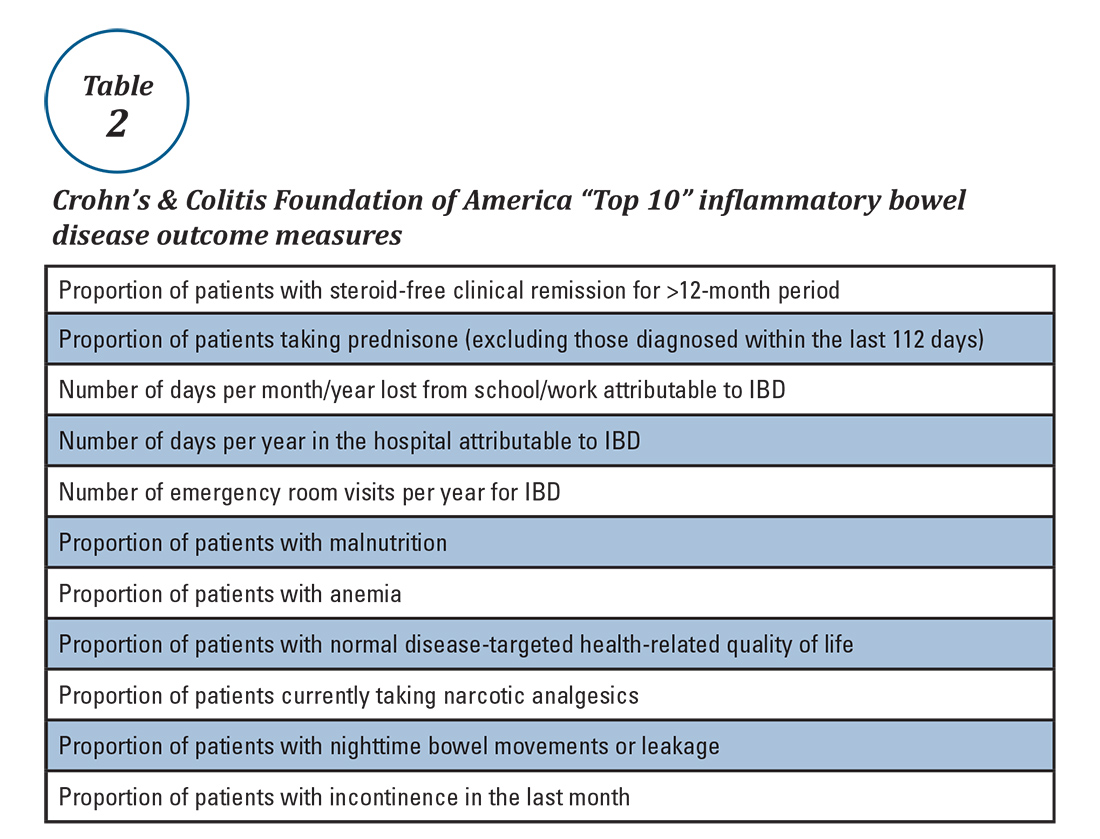

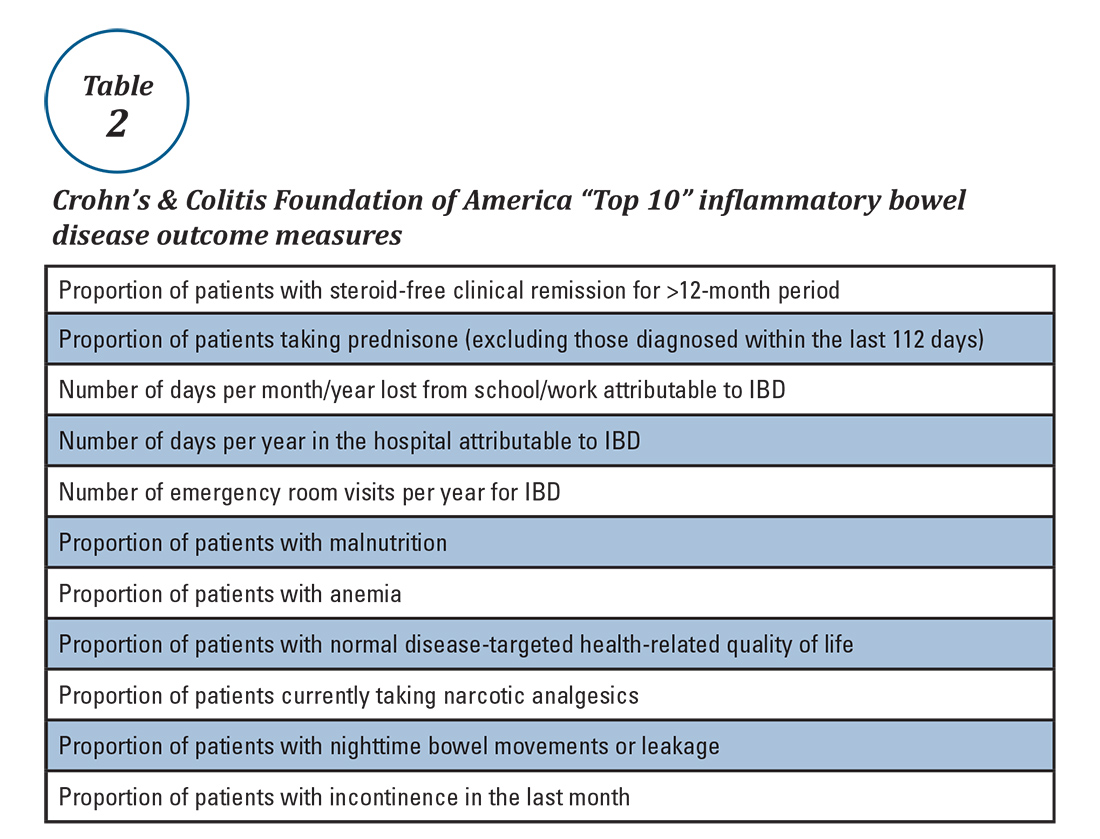

Quality measures are commonly classified as process measures or outcome measures. Process measures (“doing the right thing”) are steps taken by providers in the care of an individual patient. These often derive from evidence-based best practices. Outcome measures (“having the desired result”) identify what happens to patients as a result of care received.8 Outcome measures may be more meaningful, but there are limitations in using them to study quality of IBD care. For example, factors beyond physician control affect patient outcomes and long delays may exist between care decisions and subsequent outcomes (e.g., surgery, malnutrition).8

What IBD quality measures already exist?

Expert panels from the AGA and the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America (CCFA) produced IBD quality measure sets comprising mostly process measures (Table 1). The original 10 AGA measures released in 2011 address aspects of disease assessment, treatment, complication prevention, and health care maintenance.12 They include seven IBD-specific measures, three cross-cutting measures – defined by Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) as being broadly applicable across multiple clinical settings – and two inpatient measures. A major goal of the AGA measures was to facilitate quality reporting to the former PQRS program.

What are some quality measure limitations?

Quality measure development has an evidence base but designing an optimal measure and demonstrating impact can be challenging. Few IBD process measures are validated and thus there is often logic but not data linking process measure adherence to improved outcomes. The denominator (number of eligible patients) and potential impact of broad adherence vary for each quality measure. For example, only a small fraction of IBD patients are infected with hepatitis B and fewer than 10% will experience viral reactivation during anti-TNF therapy.17,18 Even with optimal adherence to the hepatitis B measure, few reactivations will be prevented. The wording of some measures lacks precision, allowing physicians to potentially claim credit without improving care. For example, ordering a bone density scan satisfies the bone loss assessment measure, even if osteoporosis goes unrecognized and untreated. Finally, some measures relate to actions that may not be under the control of the gastroenterologist whose performance is being measured (e.g., administering vaccinations).

IBD quality measures under MIPS

Table 1 depicts the evolution of IBD process measures from 2011 to 2017. Rather than building upon initial experience to revise and refine IBD quality measures, the measures have instead been progressively culled with the changing pay-for-performance landscape. In 2016, AGA eliminated the two inpatient measures.19 Seven of the remaining eight measures formed the IBD Measures Group which was reportable under PQRS. In 2017, MIPS brought a seismic shift in quality measure focus. The PQRS IBD Measures Group was abolished – as were all Measures Groups – and replaced by a 16-item GI Measures Set. Although AGA advocated for all of the IBD measures to be included, the new GI Measures Set deemphasized the IBD-specific measures in favor of expanded cross-cutting measures (e.g., screening for abnormal body mass index, documenting current medications, sending specialist report to referring provider).20 This reflected a previously observed trend that gastroenterologists more often reported on cross-cutting measures than specialist-specific measures.21 However, there was no evidence-based justification for dropping certain IBD-specific measures (especially the steroid-sparing therapy measure) in favor of retaining the two chosen IBD-specific measures – bone loss assessment and hepatitis B screening – which apply to only a subset of IBD patients and have limited potential to impact clinical outcomes. Although it is not mandatory to report using the GI Measures Set, we suspect that many gastroenterologists will use this set to guide their initial reporting.

There are formidable regulatory obstacles to improving the IBD quality measures included in MIPS. CMS requires that new quality measures proposed for inclusion in MIPS be fully specified and tested for validity and reliability by the individual measure developers (such as AGA). This is a costly and time-intensive process that has complicated efforts to successfully advocate for inclusion of GI-specific quality measures in MIPS, as there is no existing infrastructure for quality measure testing.

A word about Alternative Payment Models (APMs)

APMs represent the non-MIPS pathway for participating in the QPP. APMs focus on chronic disease care coordination and qualify for lump-sum incentive payments by adhering to stringent standards and financial risk-sharing requirements. A detailed overview of APMs is beyond the scope of this discussion, as the vast majority of MACRA-eligible gastroenterologists will participate in MIPS and there are currently no GI-specific APMs. However, this is an evolving area and Project Sonar has been submitted to the Physician-Focused Payment Model Technical Advisory Committee for consideration as an APM for Crohn’s disease.23

Conclusion

Quality measurement and reporting are at a crossroads. Ideally, performance improvement should be an internally driven process that addresses specific local priorities and needs. Most medical practices (73%) believe that current externally driven quality measures do not represent care quality and only 28% use their quality scores to focus their internal quality improvement activities.2 The burden and cost of external quality reporting demand better alignment with local priorities as resources are currently being diverted away from internally driven efforts that might have the greatest potential to improve patient outcomes.24 The dawn of the MACRA era presents an opportunity to shape the future of the IBD quality movement. Through validating and prioritizing existing measures and developing novel, precisely stated, and high-value metrics, there remains vast (and measurable) potential to enhance patient outcomes.

Dr. McConnell is a fellow in gastroenterology and advanced inflammatory bowel disease, division of gastroenterology, University of California, San Francisco. Dr. Velayos is professor of medicine, co–medical director, Center for Crohn’s and Colitis, University of California, San Francisco.

References

1. September 2016 Medscape survey summary. Available at http://www.healthcaredive.com/news/survey-29-of-physicians-still-havent-heard-of-macra/429322/. Accessed March 23, 2017.

2. Casalino L.P., et al. Health Aff. 2016;35:401-6.

3. Rubin D.T., et al. Curr Med Res Opin. 2017;33:529-36.

4. David G., et al. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:S-647.

5. Nguyen G.C., et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1507-13.

6. Esrailian E., et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:1005-18.

7. Spiegel B.M., et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:68-74.

8. Kappelman M.D., et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:125-133.

9. Reddy S.I., et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1357-61.

10. National Quality Measures Clearinghouse. Available at https://www.qualitymeasures.ahrq.gov/help-and-about/quality-measure-tutorials/desirable-attributes-of-a-quality-measure. Accessed March 23, 2017.

11. McGlynn E.A. Med Care. 2003;41(1 Suppl):139-47.

12. American Gastroenterological Association. Available at https://www.gastro.org/practice/quality-initiatives/IBD_Measures.pdf. Accessed March 23, 2017.

13. Melmed G.Y., et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:662-8.

14. Feuerstein J.D., et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:421-8.

15. Sapir T., et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61:1862-9.

16. Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America. IBD Qorus. Available at http://www.ccfa.org/science-and-professionals/ibdqorus/. Accessed March 23, 2017.

17. Hou J.K., et al. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(Suppl 1):S-61.

18. Reddy K.R., et al. Gastroenterology. 2015;48:215-9.

19. American Gastroenterological Association. Available at http://www.gastro.org/practice-management/measures/2016_AGA_Measures_-_IBD.pdf. Accessed March 23, 2017.

20. American Gastroenterological Association. Available at http://www.gastro.org/news_items/gi-quality-measures-for-2017-are-released-in-macra-final-rule. Accessed March 23, 2017.

21. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Available at https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/PQRS/Downloads/2014_PQRS_Experience_Rpt.pdf. Accessed March 23, 2017.

22. Dahlhamer J.M., et al. MMWR. 2016;65:1166-9.

23. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. Available at https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/253406/ProjectSonarSonarMD.pdf. Accessed March 23, 2017.

24. Meyer G.S., et al. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21:964-8.

Your next patient is a 67-year-old Medicare beneficiary with corticosteroid-dependent ulcerative colitis. Despite 4 months of maximally dosed mesalamine, his colitis flares with prednisone taper below 20 mg daily. Hepatitis B serologies and tuberculin skin test were negative 10 months ago. Which of the following do you recommend?

A. Steroid-sparing therapy initiation

B. Repeat latent tuberculosis screening in anticipation of anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy

C. Bone loss assessment

D. Pneumococcal vaccination

E. Tobacco use screening

Quality measure reporting is a costly undertaking, with medical practices spending an average of 15.1 hours per physician per week ($40,069 per physician annually) dealing with external quality measures.2 How did this expensive alphabet soup of quality measure reporting arise and how does it impact inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) care?

Why are IBD quality measures needed?

What makes a good quality measure?

Quality must be defined and measured before it can be improved. This is easier said than done, especially for IBD where a gold standard in “ideal care” is ill defined and continually evolving as new research emerges. Nonetheless, hundreds of health care quality measures have been proposed. Desirable quality measure attributes should satisfy three broad categories: importance, scientific soundness, and feasibility.10 Quality measures should address relevant and important aspects of health that are highly prevalent and for which evidence indicates a need for improvement. There should be strong evidence supporting the beneficial impact of adhering to a given measure.

Quality measures are commonly classified as process measures or outcome measures. Process measures (“doing the right thing”) are steps taken by providers in the care of an individual patient. These often derive from evidence-based best practices. Outcome measures (“having the desired result”) identify what happens to patients as a result of care received.8 Outcome measures may be more meaningful, but there are limitations in using them to study quality of IBD care. For example, factors beyond physician control affect patient outcomes and long delays may exist between care decisions and subsequent outcomes (e.g., surgery, malnutrition).8

What IBD quality measures already exist?

Expert panels from the AGA and the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America (CCFA) produced IBD quality measure sets comprising mostly process measures (Table 1). The original 10 AGA measures released in 2011 address aspects of disease assessment, treatment, complication prevention, and health care maintenance.12 They include seven IBD-specific measures, three cross-cutting measures – defined by Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) as being broadly applicable across multiple clinical settings – and two inpatient measures. A major goal of the AGA measures was to facilitate quality reporting to the former PQRS program.

What are some quality measure limitations?

Quality measure development has an evidence base but designing an optimal measure and demonstrating impact can be challenging. Few IBD process measures are validated and thus there is often logic but not data linking process measure adherence to improved outcomes. The denominator (number of eligible patients) and potential impact of broad adherence vary for each quality measure. For example, only a small fraction of IBD patients are infected with hepatitis B and fewer than 10% will experience viral reactivation during anti-TNF therapy.17,18 Even with optimal adherence to the hepatitis B measure, few reactivations will be prevented. The wording of some measures lacks precision, allowing physicians to potentially claim credit without improving care. For example, ordering a bone density scan satisfies the bone loss assessment measure, even if osteoporosis goes unrecognized and untreated. Finally, some measures relate to actions that may not be under the control of the gastroenterologist whose performance is being measured (e.g., administering vaccinations).

IBD quality measures under MIPS

Table 1 depicts the evolution of IBD process measures from 2011 to 2017. Rather than building upon initial experience to revise and refine IBD quality measures, the measures have instead been progressively culled with the changing pay-for-performance landscape. In 2016, AGA eliminated the two inpatient measures.19 Seven of the remaining eight measures formed the IBD Measures Group which was reportable under PQRS. In 2017, MIPS brought a seismic shift in quality measure focus. The PQRS IBD Measures Group was abolished – as were all Measures Groups – and replaced by a 16-item GI Measures Set. Although AGA advocated for all of the IBD measures to be included, the new GI Measures Set deemphasized the IBD-specific measures in favor of expanded cross-cutting measures (e.g., screening for abnormal body mass index, documenting current medications, sending specialist report to referring provider).20 This reflected a previously observed trend that gastroenterologists more often reported on cross-cutting measures than specialist-specific measures.21 However, there was no evidence-based justification for dropping certain IBD-specific measures (especially the steroid-sparing therapy measure) in favor of retaining the two chosen IBD-specific measures – bone loss assessment and hepatitis B screening – which apply to only a subset of IBD patients and have limited potential to impact clinical outcomes. Although it is not mandatory to report using the GI Measures Set, we suspect that many gastroenterologists will use this set to guide their initial reporting.

There are formidable regulatory obstacles to improving the IBD quality measures included in MIPS. CMS requires that new quality measures proposed for inclusion in MIPS be fully specified and tested for validity and reliability by the individual measure developers (such as AGA). This is a costly and time-intensive process that has complicated efforts to successfully advocate for inclusion of GI-specific quality measures in MIPS, as there is no existing infrastructure for quality measure testing.

A word about Alternative Payment Models (APMs)

APMs represent the non-MIPS pathway for participating in the QPP. APMs focus on chronic disease care coordination and qualify for lump-sum incentive payments by adhering to stringent standards and financial risk-sharing requirements. A detailed overview of APMs is beyond the scope of this discussion, as the vast majority of MACRA-eligible gastroenterologists will participate in MIPS and there are currently no GI-specific APMs. However, this is an evolving area and Project Sonar has been submitted to the Physician-Focused Payment Model Technical Advisory Committee for consideration as an APM for Crohn’s disease.23

Conclusion

Quality measurement and reporting are at a crossroads. Ideally, performance improvement should be an internally driven process that addresses specific local priorities and needs. Most medical practices (73%) believe that current externally driven quality measures do not represent care quality and only 28% use their quality scores to focus their internal quality improvement activities.2 The burden and cost of external quality reporting demand better alignment with local priorities as resources are currently being diverted away from internally driven efforts that might have the greatest potential to improve patient outcomes.24 The dawn of the MACRA era presents an opportunity to shape the future of the IBD quality movement. Through validating and prioritizing existing measures and developing novel, precisely stated, and high-value metrics, there remains vast (and measurable) potential to enhance patient outcomes.

Dr. McConnell is a fellow in gastroenterology and advanced inflammatory bowel disease, division of gastroenterology, University of California, San Francisco. Dr. Velayos is professor of medicine, co–medical director, Center for Crohn’s and Colitis, University of California, San Francisco.

References

1. September 2016 Medscape survey summary. Available at http://www.healthcaredive.com/news/survey-29-of-physicians-still-havent-heard-of-macra/429322/. Accessed March 23, 2017.

2. Casalino L.P., et al. Health Aff. 2016;35:401-6.

3. Rubin D.T., et al. Curr Med Res Opin. 2017;33:529-36.

4. David G., et al. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:S-647.

5. Nguyen G.C., et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1507-13.

6. Esrailian E., et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:1005-18.

7. Spiegel B.M., et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:68-74.

8. Kappelman M.D., et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:125-133.

9. Reddy S.I., et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1357-61.

10. National Quality Measures Clearinghouse. Available at https://www.qualitymeasures.ahrq.gov/help-and-about/quality-measure-tutorials/desirable-attributes-of-a-quality-measure. Accessed March 23, 2017.

11. McGlynn E.A. Med Care. 2003;41(1 Suppl):139-47.

12. American Gastroenterological Association. Available at https://www.gastro.org/practice/quality-initiatives/IBD_Measures.pdf. Accessed March 23, 2017.

13. Melmed G.Y., et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:662-8.

14. Feuerstein J.D., et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:421-8.

15. Sapir T., et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61:1862-9.

16. Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America. IBD Qorus. Available at http://www.ccfa.org/science-and-professionals/ibdqorus/. Accessed March 23, 2017.

17. Hou J.K., et al. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(Suppl 1):S-61.

18. Reddy K.R., et al. Gastroenterology. 2015;48:215-9.

19. American Gastroenterological Association. Available at http://www.gastro.org/practice-management/measures/2016_AGA_Measures_-_IBD.pdf. Accessed March 23, 2017.

20. American Gastroenterological Association. Available at http://www.gastro.org/news_items/gi-quality-measures-for-2017-are-released-in-macra-final-rule. Accessed March 23, 2017.

21. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Available at https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/PQRS/Downloads/2014_PQRS_Experience_Rpt.pdf. Accessed March 23, 2017.

22. Dahlhamer J.M., et al. MMWR. 2016;65:1166-9.

23. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. Available at https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/253406/ProjectSonarSonarMD.pdf. Accessed March 23, 2017.

24. Meyer G.S., et al. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21:964-8.