User login

Is expectant management a safe alternative to immediate delivery in patients with PPROM close to term?

Preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM) refers to rupture of membranes prior to the onset of labor before 37 weeks’ gestation. It accounts for one-third of all preterm births.1 Pregnancy complications associated with PPROM include intrauterine infection (chorioamnionitis), preterm labor, and placental abruption. Should such complications develop, immediate delivery is indicated. When to recommend elective delivery in the absence of complications, however, remains controversial.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) currently recommends elective delivery at or after 34 weeks’ gestation,2 because the prevailing evidence suggests that the risk of pregnancy-related complications (especially ascending infection) exceeds the risks of iatrogenic prematurity at this gestational age. However, ACOG acknowledges that this recommendation is based on “limited and inconsistent scientific evidence.”2 To address deficiencies in the literature, investigators designed the PPROMT (preterm prelabor rupture of the membranes close to term) trial to study women with ruptured membranes before the onset of labor between 34 and 37 weeks’ gestation.

PPROMT study designMorris and colleagues present results of their multicenter, international, randomized controlled trial (RCT) of expectant management versus planned delivery in pregnancies complicated by PPROM at 34 0/7 through 36 6/7 weeks’ gestation carried out in 65 centers across 11 countries. A total of 1,839 women not requiring urgent delivery were randomly assigned to either immediate delivery (n = 924) or expectant management (n = 915).

No difference was noted in the primary outcome of neonatal sepsis between the immediate birth (n = 23 [2%]) and expectant management groups (n = 29 [3%]; relative risk [RR], 0.8; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.5–1.3). This also was true in the subgroup of women who were colonized with group B streptococcus (RR, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.2–4.5).

There also was no difference in the secondary outcome measure, a composite metric including sepsis, ventilation for 24 or more hours, or death (73 [8%] in the immediate delivery group vs 61 [7%] in the expectant management group; RR, 1.2; 95% CI, 0.9–1.6). However, infants born to women randomly assigned to immediate delivery, versus expectant management, had a significantly higher rate of respiratory distress syndrome (RR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.1–2.3) and mechanical ventilation (RR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.0–1.8). In addition, the immediate-delivery infants had a longer median stay in the special care nursery/neonatal intensive care unit (4.0 days, interquartile range [IQR], 0.0–10.0 vs 2.0 days, IQR, 0.0–7.0) and total hospital stay (6.0 days, IQR, 3.0–10.0 vs 4.0 days, IQR, 3.0–8.0). As expected, women in the expectant management group had a significantly longer hospital stay than women in the immediate delivery group, because 75% (688/912) were managed as inpatients. Interestingly, women in the immediate delivery group had a higher cesarean delivery rate than those in the expectant management group (239 [26%] vs 169 [19%], respectively; RR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.2–1.7), although no explanation was offered.

Strengths and limitationsMajor strengths of this study include the large sample size and superior study design. It is by far the largest RCT to address this question. Because this was a pragmatic RCT, certain practices (such as the choice of latency antibiotic regimen) varied across centers, although randomization would be expected to minimize the effect of such variables on study outcome.

A major limitation is that participant recruitment occurred over a period of more than 10 years, during which time antenatal and neonatal intensive care unit practices likely would have changed.

What this evidence means for practiceFew clinical studies have the potential to significantly change obstetric management. This report by Morris and colleagues is one such study. It was well designed, well executed, and powered to look at the most clinically relevant outcome, namely, neonatal sepsis. While these study results do call into question the current American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommendations to electively deliver patients with PPROM at or after 34 weeks’ gestation, additional discussion is needed at the national level before these recommendations can be changed.

—Denis A. Vaughan, MBBCh, BAO, MRCPI, and Errol R. Norwitz, MD, PhD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Goldenberg RL, Rouse DJ. Prevention of premature birth. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(5):313–320.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins–Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 160: premature rupture of membranes. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(1):192–194.

Preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM) refers to rupture of membranes prior to the onset of labor before 37 weeks’ gestation. It accounts for one-third of all preterm births.1 Pregnancy complications associated with PPROM include intrauterine infection (chorioamnionitis), preterm labor, and placental abruption. Should such complications develop, immediate delivery is indicated. When to recommend elective delivery in the absence of complications, however, remains controversial.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) currently recommends elective delivery at or after 34 weeks’ gestation,2 because the prevailing evidence suggests that the risk of pregnancy-related complications (especially ascending infection) exceeds the risks of iatrogenic prematurity at this gestational age. However, ACOG acknowledges that this recommendation is based on “limited and inconsistent scientific evidence.”2 To address deficiencies in the literature, investigators designed the PPROMT (preterm prelabor rupture of the membranes close to term) trial to study women with ruptured membranes before the onset of labor between 34 and 37 weeks’ gestation.

PPROMT study designMorris and colleagues present results of their multicenter, international, randomized controlled trial (RCT) of expectant management versus planned delivery in pregnancies complicated by PPROM at 34 0/7 through 36 6/7 weeks’ gestation carried out in 65 centers across 11 countries. A total of 1,839 women not requiring urgent delivery were randomly assigned to either immediate delivery (n = 924) or expectant management (n = 915).

No difference was noted in the primary outcome of neonatal sepsis between the immediate birth (n = 23 [2%]) and expectant management groups (n = 29 [3%]; relative risk [RR], 0.8; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.5–1.3). This also was true in the subgroup of women who were colonized with group B streptococcus (RR, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.2–4.5).

There also was no difference in the secondary outcome measure, a composite metric including sepsis, ventilation for 24 or more hours, or death (73 [8%] in the immediate delivery group vs 61 [7%] in the expectant management group; RR, 1.2; 95% CI, 0.9–1.6). However, infants born to women randomly assigned to immediate delivery, versus expectant management, had a significantly higher rate of respiratory distress syndrome (RR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.1–2.3) and mechanical ventilation (RR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.0–1.8). In addition, the immediate-delivery infants had a longer median stay in the special care nursery/neonatal intensive care unit (4.0 days, interquartile range [IQR], 0.0–10.0 vs 2.0 days, IQR, 0.0–7.0) and total hospital stay (6.0 days, IQR, 3.0–10.0 vs 4.0 days, IQR, 3.0–8.0). As expected, women in the expectant management group had a significantly longer hospital stay than women in the immediate delivery group, because 75% (688/912) were managed as inpatients. Interestingly, women in the immediate delivery group had a higher cesarean delivery rate than those in the expectant management group (239 [26%] vs 169 [19%], respectively; RR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.2–1.7), although no explanation was offered.

Strengths and limitationsMajor strengths of this study include the large sample size and superior study design. It is by far the largest RCT to address this question. Because this was a pragmatic RCT, certain practices (such as the choice of latency antibiotic regimen) varied across centers, although randomization would be expected to minimize the effect of such variables on study outcome.

A major limitation is that participant recruitment occurred over a period of more than 10 years, during which time antenatal and neonatal intensive care unit practices likely would have changed.

What this evidence means for practiceFew clinical studies have the potential to significantly change obstetric management. This report by Morris and colleagues is one such study. It was well designed, well executed, and powered to look at the most clinically relevant outcome, namely, neonatal sepsis. While these study results do call into question the current American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommendations to electively deliver patients with PPROM at or after 34 weeks’ gestation, additional discussion is needed at the national level before these recommendations can be changed.

—Denis A. Vaughan, MBBCh, BAO, MRCPI, and Errol R. Norwitz, MD, PhD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM) refers to rupture of membranes prior to the onset of labor before 37 weeks’ gestation. It accounts for one-third of all preterm births.1 Pregnancy complications associated with PPROM include intrauterine infection (chorioamnionitis), preterm labor, and placental abruption. Should such complications develop, immediate delivery is indicated. When to recommend elective delivery in the absence of complications, however, remains controversial.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) currently recommends elective delivery at or after 34 weeks’ gestation,2 because the prevailing evidence suggests that the risk of pregnancy-related complications (especially ascending infection) exceeds the risks of iatrogenic prematurity at this gestational age. However, ACOG acknowledges that this recommendation is based on “limited and inconsistent scientific evidence.”2 To address deficiencies in the literature, investigators designed the PPROMT (preterm prelabor rupture of the membranes close to term) trial to study women with ruptured membranes before the onset of labor between 34 and 37 weeks’ gestation.

PPROMT study designMorris and colleagues present results of their multicenter, international, randomized controlled trial (RCT) of expectant management versus planned delivery in pregnancies complicated by PPROM at 34 0/7 through 36 6/7 weeks’ gestation carried out in 65 centers across 11 countries. A total of 1,839 women not requiring urgent delivery were randomly assigned to either immediate delivery (n = 924) or expectant management (n = 915).

No difference was noted in the primary outcome of neonatal sepsis between the immediate birth (n = 23 [2%]) and expectant management groups (n = 29 [3%]; relative risk [RR], 0.8; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.5–1.3). This also was true in the subgroup of women who were colonized with group B streptococcus (RR, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.2–4.5).

There also was no difference in the secondary outcome measure, a composite metric including sepsis, ventilation for 24 or more hours, or death (73 [8%] in the immediate delivery group vs 61 [7%] in the expectant management group; RR, 1.2; 95% CI, 0.9–1.6). However, infants born to women randomly assigned to immediate delivery, versus expectant management, had a significantly higher rate of respiratory distress syndrome (RR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.1–2.3) and mechanical ventilation (RR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.0–1.8). In addition, the immediate-delivery infants had a longer median stay in the special care nursery/neonatal intensive care unit (4.0 days, interquartile range [IQR], 0.0–10.0 vs 2.0 days, IQR, 0.0–7.0) and total hospital stay (6.0 days, IQR, 3.0–10.0 vs 4.0 days, IQR, 3.0–8.0). As expected, women in the expectant management group had a significantly longer hospital stay than women in the immediate delivery group, because 75% (688/912) were managed as inpatients. Interestingly, women in the immediate delivery group had a higher cesarean delivery rate than those in the expectant management group (239 [26%] vs 169 [19%], respectively; RR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.2–1.7), although no explanation was offered.

Strengths and limitationsMajor strengths of this study include the large sample size and superior study design. It is by far the largest RCT to address this question. Because this was a pragmatic RCT, certain practices (such as the choice of latency antibiotic regimen) varied across centers, although randomization would be expected to minimize the effect of such variables on study outcome.

A major limitation is that participant recruitment occurred over a period of more than 10 years, during which time antenatal and neonatal intensive care unit practices likely would have changed.

What this evidence means for practiceFew clinical studies have the potential to significantly change obstetric management. This report by Morris and colleagues is one such study. It was well designed, well executed, and powered to look at the most clinically relevant outcome, namely, neonatal sepsis. While these study results do call into question the current American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommendations to electively deliver patients with PPROM at or after 34 weeks’ gestation, additional discussion is needed at the national level before these recommendations can be changed.

—Denis A. Vaughan, MBBCh, BAO, MRCPI, and Errol R. Norwitz, MD, PhD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Goldenberg RL, Rouse DJ. Prevention of premature birth. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(5):313–320.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins–Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 160: premature rupture of membranes. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(1):192–194.

- Goldenberg RL, Rouse DJ. Prevention of premature birth. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(5):313–320.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins–Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 160: premature rupture of membranes. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(1):192–194.

Does episiotomy at vacuum delivery increase maternal morbidity?

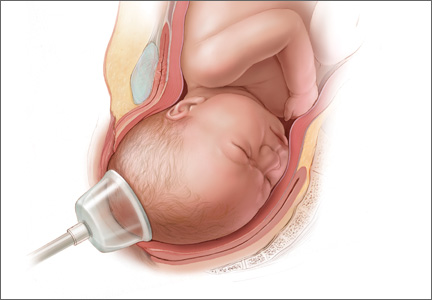

Episiotomy refers to an incision into the perineal body made during the second stage of labor to expedite delivery. It comes in 2 main flavors (midline and mediolateral), and neither one is particularly palatable. Routine use of episiotomy is strongly discouraged, for several reasons:

- There is little evidence of benefit

- It is associated with an increased risk of short- and long-term complications to both the mother and neonate, including postpartum hemorrhage, severe perineal injury, and pelvic floor dysfunction.1,2

Whether to perform an episiotomy at the time of operative vaginal delivery (forceps or vacuum), however, remains controversial.

Sagi-Dain and Sagi performed a meta- analysis of the existing literature in an effort to answer a single clinically relevant question: Should an episiotomy be performed at the time of vacuum delivery?

Details of the study

The primary endpoint was obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS), which are more commonly referred to in the United States as severe perineal injury (3rd- and 4th-degree perineal laceration). Secondary endpoints were, among others, neonatal outcomes (including Apgar scores, neonatal trauma, shoulder dystocia, neonatal resuscitation, and admission to the neonatal intensive care unit) and maternal complications (including postpartum hemorrhage, perineal infection, urinary retention, urinary/fecal incontinence, prolonged hospital stay, and analgesia use).

Of 812 original research reports initially identified that examined the effect of episiotomy at vacuum delivery on any measure of maternal or neonatal outcome, 15 articles encompassing 350,764 deliveries were included in the final analysis. Of these, 14 were observational cohort studies (13 retrospective and 1 prospective) plus 1 case-control analysis; no randomized trials were identified.

Overall, episiotomy was performed in 64.3% (SD, 18.8%; range, 28.7%-86.0%) of vacuum deliveries and was more common in nulliparous (58.7%; SD, 17.8%) than in multiparous women (34.2%; SD, 14.6%; P = .035). The investigators found that US and Canadian studies reported using mainly median episiotomy, whereas European, Scandinavian, and Australian studies used mainly mediolateral episiotomy.

Overall, OASIS occurred in 8.5% (SD, 10.6%; range 1.0%-23.6%) of vacuum deliveries, with a higher rate occurring in nulliparous compared with multiparous women (9.6%; [SD, 6.2%] vs 1.7% [SD, 1.3%], respectively; P = .031).

Median (midline) episiotomy at the time of vacuum delivery was associated with a significant increase in OASIS in both nulliparous (odds ratio [OR], 5.11; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.23-8.08) and multip- arous women (OR, 89.4; 95% CI, 11.8-677.1). A similar increase in OASIS was seen when a mediolateral episiotomy was performed at vacuum delivery in multiparous women (OR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.05-1.53), although no statistically significant relationship was evident between mediolateral episiotomy at vacuum delivery and OASIS in nulliparous women (OR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.43-1.07). Mediolateral episiotomy also was linked to increased rates of postpartum hemorrhage (OR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.16-2.86) and analgesia use (OR, 2.10; 95% CI, 1.39-3.17).

Strengths and limitations

Meta-analysis (systematic review) is not synonymous with a review of the literature. It has a very specific methodology and should be treated as original research, albeit in silico. Meta-analyses use precise statistical methods to combine and contrast results from a number of independent original research reports. The current study is an exemplary illustration of just how such an analysis should be conducted. As prescribed by the Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines,3 it included all study designs, both published and unpublished data, and was not limited to English language reports.

In addition, if results were unclear or data were missing, the investigators contacted the authors directly to verify the information. Prior published statistical analyses were disregarded, and the investigators conducted an independent evaluation of the pooled data using each patient as a separate data point. Data classification and coding were clearly described; the analysis was performed independently by 2 separate investigators; and a detailed assessment of data quality, heterogeneity, and sensitivity testing was included.

What this evidence means for practice

Episiotomy at the time of vacuum delivery does not appear to be of benefit, and it more likely than not increases maternal morbidity. This is especially true of median episiotomy (the type used most commonly in the United States), which increases the risk of OASIS at the time of vacuum delivery 5-fold in nulliparous and 89-fold in multiparous women.

Confidence in these conclusions is guarded. Based on the small number of reports, the lack of randomized trials, and the significant heterogeneity between the studies, the authors rated the overall quality of evidence as “low” to “very low” using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) working group criteria. Additional large prospective clinical trials are needed to definitively answer the question of whether episiotomy at vacuum delivery increases maternal morbidity.

Until such studies are available, however, it would be best if obstetric care providers avoid episiotomy at the time of vacuum delivery. On a personal note, I look forward to the day when a medical student turns to an attending and asks: “What is an episiotomy?” And the attending responds: “I don’t know. I’ve never seen one.” Only then will I be ready to retire.

>> Errol R. Norwitz, MD, PhD

1. Carroli G, Mignini L. Episiotomy for vaginal birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD000081.

2. Ali U, Norwitz ER. Vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2009;2(1):5-17.

3. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008-2012.

Episiotomy refers to an incision into the perineal body made during the second stage of labor to expedite delivery. It comes in 2 main flavors (midline and mediolateral), and neither one is particularly palatable. Routine use of episiotomy is strongly discouraged, for several reasons:

- There is little evidence of benefit

- It is associated with an increased risk of short- and long-term complications to both the mother and neonate, including postpartum hemorrhage, severe perineal injury, and pelvic floor dysfunction.1,2

Whether to perform an episiotomy at the time of operative vaginal delivery (forceps or vacuum), however, remains controversial.

Sagi-Dain and Sagi performed a meta- analysis of the existing literature in an effort to answer a single clinically relevant question: Should an episiotomy be performed at the time of vacuum delivery?

Details of the study

The primary endpoint was obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS), which are more commonly referred to in the United States as severe perineal injury (3rd- and 4th-degree perineal laceration). Secondary endpoints were, among others, neonatal outcomes (including Apgar scores, neonatal trauma, shoulder dystocia, neonatal resuscitation, and admission to the neonatal intensive care unit) and maternal complications (including postpartum hemorrhage, perineal infection, urinary retention, urinary/fecal incontinence, prolonged hospital stay, and analgesia use).

Of 812 original research reports initially identified that examined the effect of episiotomy at vacuum delivery on any measure of maternal or neonatal outcome, 15 articles encompassing 350,764 deliveries were included in the final analysis. Of these, 14 were observational cohort studies (13 retrospective and 1 prospective) plus 1 case-control analysis; no randomized trials were identified.

Overall, episiotomy was performed in 64.3% (SD, 18.8%; range, 28.7%-86.0%) of vacuum deliveries and was more common in nulliparous (58.7%; SD, 17.8%) than in multiparous women (34.2%; SD, 14.6%; P = .035). The investigators found that US and Canadian studies reported using mainly median episiotomy, whereas European, Scandinavian, and Australian studies used mainly mediolateral episiotomy.

Overall, OASIS occurred in 8.5% (SD, 10.6%; range 1.0%-23.6%) of vacuum deliveries, with a higher rate occurring in nulliparous compared with multiparous women (9.6%; [SD, 6.2%] vs 1.7% [SD, 1.3%], respectively; P = .031).

Median (midline) episiotomy at the time of vacuum delivery was associated with a significant increase in OASIS in both nulliparous (odds ratio [OR], 5.11; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.23-8.08) and multip- arous women (OR, 89.4; 95% CI, 11.8-677.1). A similar increase in OASIS was seen when a mediolateral episiotomy was performed at vacuum delivery in multiparous women (OR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.05-1.53), although no statistically significant relationship was evident between mediolateral episiotomy at vacuum delivery and OASIS in nulliparous women (OR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.43-1.07). Mediolateral episiotomy also was linked to increased rates of postpartum hemorrhage (OR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.16-2.86) and analgesia use (OR, 2.10; 95% CI, 1.39-3.17).

Strengths and limitations

Meta-analysis (systematic review) is not synonymous with a review of the literature. It has a very specific methodology and should be treated as original research, albeit in silico. Meta-analyses use precise statistical methods to combine and contrast results from a number of independent original research reports. The current study is an exemplary illustration of just how such an analysis should be conducted. As prescribed by the Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines,3 it included all study designs, both published and unpublished data, and was not limited to English language reports.

In addition, if results were unclear or data were missing, the investigators contacted the authors directly to verify the information. Prior published statistical analyses were disregarded, and the investigators conducted an independent evaluation of the pooled data using each patient as a separate data point. Data classification and coding were clearly described; the analysis was performed independently by 2 separate investigators; and a detailed assessment of data quality, heterogeneity, and sensitivity testing was included.

What this evidence means for practice

Episiotomy at the time of vacuum delivery does not appear to be of benefit, and it more likely than not increases maternal morbidity. This is especially true of median episiotomy (the type used most commonly in the United States), which increases the risk of OASIS at the time of vacuum delivery 5-fold in nulliparous and 89-fold in multiparous women.

Confidence in these conclusions is guarded. Based on the small number of reports, the lack of randomized trials, and the significant heterogeneity between the studies, the authors rated the overall quality of evidence as “low” to “very low” using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) working group criteria. Additional large prospective clinical trials are needed to definitively answer the question of whether episiotomy at vacuum delivery increases maternal morbidity.

Until such studies are available, however, it would be best if obstetric care providers avoid episiotomy at the time of vacuum delivery. On a personal note, I look forward to the day when a medical student turns to an attending and asks: “What is an episiotomy?” And the attending responds: “I don’t know. I’ve never seen one.” Only then will I be ready to retire.

>> Errol R. Norwitz, MD, PhD

Episiotomy refers to an incision into the perineal body made during the second stage of labor to expedite delivery. It comes in 2 main flavors (midline and mediolateral), and neither one is particularly palatable. Routine use of episiotomy is strongly discouraged, for several reasons:

- There is little evidence of benefit

- It is associated with an increased risk of short- and long-term complications to both the mother and neonate, including postpartum hemorrhage, severe perineal injury, and pelvic floor dysfunction.1,2

Whether to perform an episiotomy at the time of operative vaginal delivery (forceps or vacuum), however, remains controversial.

Sagi-Dain and Sagi performed a meta- analysis of the existing literature in an effort to answer a single clinically relevant question: Should an episiotomy be performed at the time of vacuum delivery?

Details of the study

The primary endpoint was obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS), which are more commonly referred to in the United States as severe perineal injury (3rd- and 4th-degree perineal laceration). Secondary endpoints were, among others, neonatal outcomes (including Apgar scores, neonatal trauma, shoulder dystocia, neonatal resuscitation, and admission to the neonatal intensive care unit) and maternal complications (including postpartum hemorrhage, perineal infection, urinary retention, urinary/fecal incontinence, prolonged hospital stay, and analgesia use).

Of 812 original research reports initially identified that examined the effect of episiotomy at vacuum delivery on any measure of maternal or neonatal outcome, 15 articles encompassing 350,764 deliveries were included in the final analysis. Of these, 14 were observational cohort studies (13 retrospective and 1 prospective) plus 1 case-control analysis; no randomized trials were identified.

Overall, episiotomy was performed in 64.3% (SD, 18.8%; range, 28.7%-86.0%) of vacuum deliveries and was more common in nulliparous (58.7%; SD, 17.8%) than in multiparous women (34.2%; SD, 14.6%; P = .035). The investigators found that US and Canadian studies reported using mainly median episiotomy, whereas European, Scandinavian, and Australian studies used mainly mediolateral episiotomy.

Overall, OASIS occurred in 8.5% (SD, 10.6%; range 1.0%-23.6%) of vacuum deliveries, with a higher rate occurring in nulliparous compared with multiparous women (9.6%; [SD, 6.2%] vs 1.7% [SD, 1.3%], respectively; P = .031).

Median (midline) episiotomy at the time of vacuum delivery was associated with a significant increase in OASIS in both nulliparous (odds ratio [OR], 5.11; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.23-8.08) and multip- arous women (OR, 89.4; 95% CI, 11.8-677.1). A similar increase in OASIS was seen when a mediolateral episiotomy was performed at vacuum delivery in multiparous women (OR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.05-1.53), although no statistically significant relationship was evident between mediolateral episiotomy at vacuum delivery and OASIS in nulliparous women (OR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.43-1.07). Mediolateral episiotomy also was linked to increased rates of postpartum hemorrhage (OR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.16-2.86) and analgesia use (OR, 2.10; 95% CI, 1.39-3.17).

Strengths and limitations

Meta-analysis (systematic review) is not synonymous with a review of the literature. It has a very specific methodology and should be treated as original research, albeit in silico. Meta-analyses use precise statistical methods to combine and contrast results from a number of independent original research reports. The current study is an exemplary illustration of just how such an analysis should be conducted. As prescribed by the Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines,3 it included all study designs, both published and unpublished data, and was not limited to English language reports.

In addition, if results were unclear or data were missing, the investigators contacted the authors directly to verify the information. Prior published statistical analyses were disregarded, and the investigators conducted an independent evaluation of the pooled data using each patient as a separate data point. Data classification and coding were clearly described; the analysis was performed independently by 2 separate investigators; and a detailed assessment of data quality, heterogeneity, and sensitivity testing was included.

What this evidence means for practice

Episiotomy at the time of vacuum delivery does not appear to be of benefit, and it more likely than not increases maternal morbidity. This is especially true of median episiotomy (the type used most commonly in the United States), which increases the risk of OASIS at the time of vacuum delivery 5-fold in nulliparous and 89-fold in multiparous women.

Confidence in these conclusions is guarded. Based on the small number of reports, the lack of randomized trials, and the significant heterogeneity between the studies, the authors rated the overall quality of evidence as “low” to “very low” using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) working group criteria. Additional large prospective clinical trials are needed to definitively answer the question of whether episiotomy at vacuum delivery increases maternal morbidity.

Until such studies are available, however, it would be best if obstetric care providers avoid episiotomy at the time of vacuum delivery. On a personal note, I look forward to the day when a medical student turns to an attending and asks: “What is an episiotomy?” And the attending responds: “I don’t know. I’ve never seen one.” Only then will I be ready to retire.

>> Errol R. Norwitz, MD, PhD

1. Carroli G, Mignini L. Episiotomy for vaginal birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD000081.

2. Ali U, Norwitz ER. Vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2009;2(1):5-17.

3. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008-2012.

1. Carroli G, Mignini L. Episiotomy for vaginal birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD000081.

2. Ali U, Norwitz ER. Vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2009;2(1):5-17.

3. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008-2012.

10 evidence-based recommendations to prevent surgical site infection after cesarean delivery

Infection is the second leading cause of pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, responsible for 13.6% of all maternal deaths.1 Cesarean delivery is the single most important risk factor for puerperal infection, increasing its incidence approximately 5- to 20-fold.2

Given that cesarean deliveries represent 32.7% of all births in the United States,3 the overall health and socioeconomic burden of these infections is substantial. In addition, more than half of all pregnancies are complicated by maternal obesity, which is associated with an increased risk of cesarean delivery as well as subsequent wound complications.4

In this review, we offer 10 evidence-based strategies to prevent surgical site infection (SSI) after cesarean delivery.

1 Maintain strict glycemic control in women with diabetes

Perioperative hyperglycemia is associated with an increased risk of postoperative infection in patients with diabetes

Ramos M, Khalpey Z, Lipsitz S, et al. Relationship of perioperative hyperglycemia and postoperative infections in patients who undergo general and vascular surgery. Ann Surg. 2008;248(4):585–591.

Hanazaki K, Maeda H, Okabayashi T. Relationship between perioperative glycemic control and postoperative infections. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(33):4122–4125.

Although data are limited on the impact of perioperative glycemic control on postcesarean infection rates, the association has been well documented in the general surgery literature. Results of a retrospective cohort study of 995 patients undergoing general or vascular surgery demonstrated that postoperative hyperglycemia increased the risk of infection by 30% for every 40-point increase in serum glucose levels from normoglycemia (defined as <110 mg/dL) (odds ratio, 1.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.03–1.64).5 Hyperglycemia causes abnormalities of leukocyte function, including impaired granulocyte adherence, impaired phagocytosis, delayed chemotaxis, and depressed bactericidal capacity. And all of these abnormalities in leukocyte function appear to improve with strict glycemic control, although the target range for blood glucose remains uncertain.6

2 Recommend preoperative antiseptic showering

Ask patients to shower with 4% chlorhexidine gluconate the night before surgery to reduce the presence of bacterial skin flora

Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, et al; Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection, 1999. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20(4):247–278.

Chlebicki MP, Safdar N, O’Horo JC, Maki DG. Preoperative chlorhexidine shower or bath for prevention of surgical site infection: a meta-analysis. Am J Infect Control. 2013;41(2):167–173.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, preoperative showering with chlorhexidine reduces the presence of bacterial skin flora. A study of more than 700 patients showed that preoperative showers with chlorhexidine reduced bacterial colony counts 9-fold, compared with only 1.3-fold for povidone-iodine.7 Whether this translates into a reduction in SSI remains controversial, in large part because of poor quality of the existing prospective trials, which used different agents, concentrations, and methods of skin preparation.8

Small clinical trials have found a benefit to chlorhexidine treatment the day before surgery.9,10 However, a recent meta-analysis of 16 randomized trials failed to show a significant reduction in the rate of SSI with chlorhexidine compared with soap, placebo, or no washing (relative risk [RR], 0.90; 95% CI, 0.77–1.05).11

3 Administer intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis

All patients who undergo cesarean delivery should be given appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis within 60 minutes before the skin incision

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 120: Use of prophylactic antibiotics in labor and delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(6):1472–1483.

Costantine MM, Rahman M, Ghulmiyah L, et al. Timing of perioperative antibiotics for cesarean delivery: a meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(3):301.e1–e6.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends the use of a single dose of a narrow-spectrum, first-generation cephalosporin (or a single dose of clindamycin with an aminoglycoside for those with a significant penicillin allergy) as SSI chemoprophylaxis for cesarean delivery.12 Due to concerns about fetal antibiotic exposure, such prophylaxis traditionally has been given after clamping of the umbilical cord. However, results of a recent meta-analysis of 5 randomized controlled trials demonstrated that antibiotic prophylaxis significantly reduced infectious morbidity (RR, 0.50; 95% CI, 0.33–0.78) when it was given 60 minutes before the skin incision, with no significant effect on neonatal outcome.13

4 Give a higher dose of preoperative antibiotics in obese women

Given the increased volume of distribution and the increased risk of postcesarean infection in the obese population, a higher dose of preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended

Robinson HE, O’Connell CM, Joseph KS, McLeod NL. Maternal outcomes in pregnancies complicated by obesity. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(6):1357–1364.

Pevzner L, Swank M, Krepel C, et al. Effects of maternal obesity on tissue concentrations of prophylactic cefazolin during cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(4):877–882.

The impact of maternal obesity on the risk of SSI after cesarean delivery was illustrated in a 2005 retrospective cohort study of 10,134 obese women. Moderately obese women with a prepregnancy weight of 90 to 100 kg were 1.6 times (95% CI, 1.31–1.95) more likely to have a wound infection, and severely obese women (>120 kg) were 4.45 times (95% CI, 3.00–6.61) more likely to have a wound infection after cesarean delivery, compared with women of normal weight.14

Moreover, a study of tissue concentrations of prophylactic cefazolin in obese women demonstrated that concentrations within adipose tissue at the site of the skin incision were inversely proportional to maternal body mass index (BMI).15 Given these findings, consideration should be given to using a higher dose of preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis in obese women, specifically 3 g of intravenous (IV) cefazolin for women with a BMI greater than 30 kg/m2 or an absolute weight of more than 100 kg.12

5 Use clippers for preoperative hair removal

If hair removal is necessary to perform the skin incision for cesarean delivery, the use of clippers is preferred

Tanner J, Norrie P, Melen K. Preoperative hair removal to reduce surgical site infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;11:CD004122.

In a Cochrane review of 3 randomized clinical trials comparing preoperative hair-removal techniques, shaving was associated with an increased risk of SSI, compared with clipping (RR, 2.09; 95% CI, 1.15–3.80).15 Shaving is thought to result in microscopic skin abrasions that can serve as foci for bacterial growth.

Interestingly, in this same Cochrane review, a separate analysis of 6 studies failed to show a benefit of preoperative hair removal by any means, compared with no hair removal,15 suggesting that routine hair removal may not be indicated for all patients.

6 Use chlorhexidine-alcohol for skin prep

Prepare the skin with chlorhexidine-alcohol immediately before surgery

Darouiche RO, Wall MJ Jr, Itani KM, et al. Chlorhexidine-alcohol versus povidone-iodine for surgical-site antisepsis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(1):18–26.

Kunkle CM, Marchan J, Safadi S, Whitman S, Chmait RH. Chlorhexidine gluconate versus povidone iodine at cesarean delivery: a randomized controlled trial. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014;18:1–5.

Data from a randomized multicenter trial of 849 patients showed that the use of a chlorhexidine-alcohol skin preparation immediately before surgery lowered the rate of SSI after clean-contaminated surgery, compared with povidone-iodine (RR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.41–0.85).16 Studies focusing on cesarean delivery alone are limited, although 1 small randomized trial found that chlorhexidine treatment significantly reduced bacterial growth at 18 hours after cesarean, compared with povidone-iodine (RR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.07–0.70).17

7 Consider an alcohol-based hand rub for preoperative antisepsis

Alcohol-based hand rubs may be more effective than conventional surgical scrub

Shen NJ, Pan SC, Sheng WH, et al. Comparative antimicrobial efficacy of alcohol-based hand rub and conventional surgical scrub in a medical center [published online ahead of print September 21, 2013]. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. pii:S1684–1182(13)00150–3.

Tanner J, Swarbrook S, Stuart J. Surgical hand antisepsis to reduce surgical site infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;1:CD004288.

Several agents are available for preoperative surgical hand antisepsis, including newer alcohol-based rubs and conventional aqueous scrubs that contain either chlorhexidine gluconate or povidone-iodine. In a prospective cohort study of 128 health care providers, use of an alcohol-based rub for surgical hand antisepsis was associated with a lower rate of positive bacterial culture (6.2%), compared with a chlorhexidine-based conventional scrub (47.6%; P<.001).18 However, if an aqueous-based scrub is the only option available for surgical hand antisepsis, a Cochrane review found that chlorhexidine gluconate scrubs were more effective than povidone-iodine scrubs in 3 trials, resulting in fewer colony-forming units of bacteria on the hands of the surgical team.19

8 Close the skin with subcuticular sutures

Use of subcuticular sutures for skin closure is associated with a lower risk of wound complications, compared with staples

Mackeen AD, Schuster M, Berghella V. Suture versus staples for skin closure after cesarean: a meta-analysis [published online ahead of print December 19, 2014]. Am J Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2014.12.020.

A meta-analysis of 12 randomized controlled trials including 3,112 women demonstrated that subcuticular closure is associated with a decreased risk of wound complications, compared with staple closure (RR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.28–0.87). The reduced risk remained significant even when stratified by obesity. Both closure techniques were shown to be equivalent with regard to postoperative pain, cosmetic outcome, and patient satisfaction.20

9 Close the subcutaneous tissue

Closure of the subcutaneous fat is associated with a decreased risk of wound disruption for women with a tissue thickness of more than 2 cm

Chelmow D, Rodriguez EJ, Sabatini MM. Suture closure of subcutaneous fat and wound disruption after cesarean delivery: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(5 pt 1):974–980.

Dahlke JD, Mendez-Figueroa H, Rouse DJ, Berghella V, Baxter JK, Chauhan SP. Evidence-based surgery for cesarean delivery: an updated systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(4):294–306.

A meta-analysis of 5 randomized controlled trials demonstrated that suture closure of subcutaneous fat is associated with a 34% decrease in the risk of wound disruption in women with fat thickness greater than 2 cm (RR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.48–0.91).21

A recent systematic review of evidence-based guidelines for surgical decisions during cesarean delivery also recommended this practice based on results of 9 published studies.22 In this review, however, subcutaneous drain placement did not offer any additional benefit, regardless of tissue thickness.22

10 Avoid unproven techniques

Several commonly performed techniques have not been associated with a decreased risk of SSI after cesarean delivery

Dahlke JD, Mendez-Figueroa H, Rouse DJ, Berghella V, Baxter JK, Chauhan SP. Evidence-based surgery for cesarean delivery: an updated systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(4):294–306.

CORONIS Trial Collaborative Group. The CORONIS Trial. International study of caesarean section surgical techniques: a randomised fractional, factorial trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2007;7:24. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-7-24.

Familiarity with the obstetric literature will help providers determine which interventions prevent SSI and which do not. Well-designed clinical studies have demonstrated no significant difference in the rate of postcesarean infectious morbidity with the administration of high concentrations of perioperative oxygen,22 saline wound irrigation,22 placement of subcutaneous drains,22 blunt versus sharp abdominal entry,23 and exteriorization of the uterus for repair.23

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Creanga AA, Berg CJ, Syverson C, Seed K, Bruce FC, Callaghan WM. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 2006–2010. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(1):5–12.

2. Leth RA, Moller JK, Thomsen RW, Uldbjerg N, Norgaard M. Risk of selected postpartum infections after cesarean section compared with vaginal birth: a five-year cohort study of 32,468 women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009;88(9):976–983.

3. Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman JK, et al. Births: final data for 2013. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64(1):1–65.

4. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 549: Obesity in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(1):213–217.

5. Dahlke JD, Mendez-Figueroa H, Rouse DJ, Berghella V, Baxter JK, Chauhan SP. Evidence-based surgery for cesarean delivery: an updated systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(4):294–306.

6. Ramos M, Khalpey Z, Lipsitz S, et al. Relationship of perioperative hyperglycemia and postoperative infections in patients who undergo general and vascular surgery. Ann Surg. 2008;248(4):585–591.

7. Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, Silver LC, Jarvis WR. Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee: Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection, 1999. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20(4):250–278.

8. Webster J, Osborne S. Preoperative bathing or showering with skin antiseptics to prevent surgical site infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9:CD004985.

9. Hayek LJ, Emerson JM, Gardner AM. A placebo-controlled trial of the effect of two preoperative baths or showers with chlorhexidine detergent on post-operative wound infection rates. J Hosp Infect. 1987;10(2):165–172.

10. Wihlborg O. The effect of washing with chlorhexidine soap on wound infection rate in general surgery: a controlled clinical study. Ann Chir Gynaecol. 1987;76(5):263–265.

11. Chlebicki MP, Safdar N, O’Horo JC, Maki DG. Preoperative chlorhexidine shower or bath for prevention of surgical site infection: a meta-analysis. Am J Infect Control. 2013;41(2):167–173.

12. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 120: Use of prophylactic antibiotics in labor and delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(6):1472–1483.

13. Costantine MM, Rahman M, Ghulmiyah L, et al. Timing of perioperative antibiotics for cesarean delivery: a meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(3):301.e1–e6.

14. Robinson HE, O’Connell CM, Joseph KS, McLeod NL. Maternal outcomes in pregnancies complicated by obesity. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(6):1357–1364.

15. Pevzner L, Swank M, Krepel C, et al. Effects of maternal obesity on tissue concentrations of prophylactic cefazolin during cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(4):877–882.

16. Tanner J, Norrie P, Melen K. Preoperative hair removal to reduce surgical site infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;11:CD004122.

17. Darouiche RO, Wall MJ Jr, Itani KM, et al. Chlorhexidine-alcohol versus povidone-iodine for surgical-site antisepsis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(1):18–26.

18. Kunkle CM, Marchan J, Safadi S, Whitman S, Chmait RH. Chlorhexidine gluconate versus povidone iodine at cesarean delivery: a randomized controlled trial. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014;18:1–5.

19. Shen NJ, Pan SC, Sheng WH, et al. Comparative antimicrobial efficacy of alcohol-based hand rub and conventional surgical scrub in a medical center [published online ahead of print September 21, 2013]. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. pii:S1684–1182(13)00150–3.

20. Tanner J, Swarbrook S, Stuart J. Surgical hand antisepsis to reduce surgical site infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;1:CD004288.

21. Mackeen AD, Schuster M, Berghella V. Suture versus staples for skin closure after cesarean: a meta-analysis [published online ahead of print December 19, 2014]. Am J Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2014.12.020.

22. Chelmow D, Rodriguez EJ, Sabatini MM. Suture closure of subcutaneous fat and wound disruption after cesarean delivery: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(5 Pt 1):974–980.

23. Hanazaki K, Maeda H, Okabayashi T. Relationship between perioperative glycemic control and postoperative infections. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(33):4122–4125.

Infection is the second leading cause of pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, responsible for 13.6% of all maternal deaths.1 Cesarean delivery is the single most important risk factor for puerperal infection, increasing its incidence approximately 5- to 20-fold.2

Given that cesarean deliveries represent 32.7% of all births in the United States,3 the overall health and socioeconomic burden of these infections is substantial. In addition, more than half of all pregnancies are complicated by maternal obesity, which is associated with an increased risk of cesarean delivery as well as subsequent wound complications.4

In this review, we offer 10 evidence-based strategies to prevent surgical site infection (SSI) after cesarean delivery.

1 Maintain strict glycemic control in women with diabetes

Perioperative hyperglycemia is associated with an increased risk of postoperative infection in patients with diabetes

Ramos M, Khalpey Z, Lipsitz S, et al. Relationship of perioperative hyperglycemia and postoperative infections in patients who undergo general and vascular surgery. Ann Surg. 2008;248(4):585–591.

Hanazaki K, Maeda H, Okabayashi T. Relationship between perioperative glycemic control and postoperative infections. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(33):4122–4125.

Although data are limited on the impact of perioperative glycemic control on postcesarean infection rates, the association has been well documented in the general surgery literature. Results of a retrospective cohort study of 995 patients undergoing general or vascular surgery demonstrated that postoperative hyperglycemia increased the risk of infection by 30% for every 40-point increase in serum glucose levels from normoglycemia (defined as <110 mg/dL) (odds ratio, 1.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.03–1.64).5 Hyperglycemia causes abnormalities of leukocyte function, including impaired granulocyte adherence, impaired phagocytosis, delayed chemotaxis, and depressed bactericidal capacity. And all of these abnormalities in leukocyte function appear to improve with strict glycemic control, although the target range for blood glucose remains uncertain.6

2 Recommend preoperative antiseptic showering

Ask patients to shower with 4% chlorhexidine gluconate the night before surgery to reduce the presence of bacterial skin flora

Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, et al; Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection, 1999. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20(4):247–278.

Chlebicki MP, Safdar N, O’Horo JC, Maki DG. Preoperative chlorhexidine shower or bath for prevention of surgical site infection: a meta-analysis. Am J Infect Control. 2013;41(2):167–173.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, preoperative showering with chlorhexidine reduces the presence of bacterial skin flora. A study of more than 700 patients showed that preoperative showers with chlorhexidine reduced bacterial colony counts 9-fold, compared with only 1.3-fold for povidone-iodine.7 Whether this translates into a reduction in SSI remains controversial, in large part because of poor quality of the existing prospective trials, which used different agents, concentrations, and methods of skin preparation.8

Small clinical trials have found a benefit to chlorhexidine treatment the day before surgery.9,10 However, a recent meta-analysis of 16 randomized trials failed to show a significant reduction in the rate of SSI with chlorhexidine compared with soap, placebo, or no washing (relative risk [RR], 0.90; 95% CI, 0.77–1.05).11

3 Administer intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis

All patients who undergo cesarean delivery should be given appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis within 60 minutes before the skin incision

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 120: Use of prophylactic antibiotics in labor and delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(6):1472–1483.

Costantine MM, Rahman M, Ghulmiyah L, et al. Timing of perioperative antibiotics for cesarean delivery: a meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(3):301.e1–e6.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends the use of a single dose of a narrow-spectrum, first-generation cephalosporin (or a single dose of clindamycin with an aminoglycoside for those with a significant penicillin allergy) as SSI chemoprophylaxis for cesarean delivery.12 Due to concerns about fetal antibiotic exposure, such prophylaxis traditionally has been given after clamping of the umbilical cord. However, results of a recent meta-analysis of 5 randomized controlled trials demonstrated that antibiotic prophylaxis significantly reduced infectious morbidity (RR, 0.50; 95% CI, 0.33–0.78) when it was given 60 minutes before the skin incision, with no significant effect on neonatal outcome.13

4 Give a higher dose of preoperative antibiotics in obese women

Given the increased volume of distribution and the increased risk of postcesarean infection in the obese population, a higher dose of preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended

Robinson HE, O’Connell CM, Joseph KS, McLeod NL. Maternal outcomes in pregnancies complicated by obesity. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(6):1357–1364.

Pevzner L, Swank M, Krepel C, et al. Effects of maternal obesity on tissue concentrations of prophylactic cefazolin during cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(4):877–882.

The impact of maternal obesity on the risk of SSI after cesarean delivery was illustrated in a 2005 retrospective cohort study of 10,134 obese women. Moderately obese women with a prepregnancy weight of 90 to 100 kg were 1.6 times (95% CI, 1.31–1.95) more likely to have a wound infection, and severely obese women (>120 kg) were 4.45 times (95% CI, 3.00–6.61) more likely to have a wound infection after cesarean delivery, compared with women of normal weight.14

Moreover, a study of tissue concentrations of prophylactic cefazolin in obese women demonstrated that concentrations within adipose tissue at the site of the skin incision were inversely proportional to maternal body mass index (BMI).15 Given these findings, consideration should be given to using a higher dose of preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis in obese women, specifically 3 g of intravenous (IV) cefazolin for women with a BMI greater than 30 kg/m2 or an absolute weight of more than 100 kg.12

5 Use clippers for preoperative hair removal

If hair removal is necessary to perform the skin incision for cesarean delivery, the use of clippers is preferred

Tanner J, Norrie P, Melen K. Preoperative hair removal to reduce surgical site infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;11:CD004122.

In a Cochrane review of 3 randomized clinical trials comparing preoperative hair-removal techniques, shaving was associated with an increased risk of SSI, compared with clipping (RR, 2.09; 95% CI, 1.15–3.80).15 Shaving is thought to result in microscopic skin abrasions that can serve as foci for bacterial growth.

Interestingly, in this same Cochrane review, a separate analysis of 6 studies failed to show a benefit of preoperative hair removal by any means, compared with no hair removal,15 suggesting that routine hair removal may not be indicated for all patients.

6 Use chlorhexidine-alcohol for skin prep

Prepare the skin with chlorhexidine-alcohol immediately before surgery

Darouiche RO, Wall MJ Jr, Itani KM, et al. Chlorhexidine-alcohol versus povidone-iodine for surgical-site antisepsis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(1):18–26.

Kunkle CM, Marchan J, Safadi S, Whitman S, Chmait RH. Chlorhexidine gluconate versus povidone iodine at cesarean delivery: a randomized controlled trial. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014;18:1–5.

Data from a randomized multicenter trial of 849 patients showed that the use of a chlorhexidine-alcohol skin preparation immediately before surgery lowered the rate of SSI after clean-contaminated surgery, compared with povidone-iodine (RR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.41–0.85).16 Studies focusing on cesarean delivery alone are limited, although 1 small randomized trial found that chlorhexidine treatment significantly reduced bacterial growth at 18 hours after cesarean, compared with povidone-iodine (RR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.07–0.70).17

7 Consider an alcohol-based hand rub for preoperative antisepsis

Alcohol-based hand rubs may be more effective than conventional surgical scrub

Shen NJ, Pan SC, Sheng WH, et al. Comparative antimicrobial efficacy of alcohol-based hand rub and conventional surgical scrub in a medical center [published online ahead of print September 21, 2013]. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. pii:S1684–1182(13)00150–3.

Tanner J, Swarbrook S, Stuart J. Surgical hand antisepsis to reduce surgical site infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;1:CD004288.

Several agents are available for preoperative surgical hand antisepsis, including newer alcohol-based rubs and conventional aqueous scrubs that contain either chlorhexidine gluconate or povidone-iodine. In a prospective cohort study of 128 health care providers, use of an alcohol-based rub for surgical hand antisepsis was associated with a lower rate of positive bacterial culture (6.2%), compared with a chlorhexidine-based conventional scrub (47.6%; P<.001).18 However, if an aqueous-based scrub is the only option available for surgical hand antisepsis, a Cochrane review found that chlorhexidine gluconate scrubs were more effective than povidone-iodine scrubs in 3 trials, resulting in fewer colony-forming units of bacteria on the hands of the surgical team.19

8 Close the skin with subcuticular sutures

Use of subcuticular sutures for skin closure is associated with a lower risk of wound complications, compared with staples

Mackeen AD, Schuster M, Berghella V. Suture versus staples for skin closure after cesarean: a meta-analysis [published online ahead of print December 19, 2014]. Am J Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2014.12.020.

A meta-analysis of 12 randomized controlled trials including 3,112 women demonstrated that subcuticular closure is associated with a decreased risk of wound complications, compared with staple closure (RR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.28–0.87). The reduced risk remained significant even when stratified by obesity. Both closure techniques were shown to be equivalent with regard to postoperative pain, cosmetic outcome, and patient satisfaction.20

9 Close the subcutaneous tissue

Closure of the subcutaneous fat is associated with a decreased risk of wound disruption for women with a tissue thickness of more than 2 cm

Chelmow D, Rodriguez EJ, Sabatini MM. Suture closure of subcutaneous fat and wound disruption after cesarean delivery: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(5 pt 1):974–980.

Dahlke JD, Mendez-Figueroa H, Rouse DJ, Berghella V, Baxter JK, Chauhan SP. Evidence-based surgery for cesarean delivery: an updated systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(4):294–306.

A meta-analysis of 5 randomized controlled trials demonstrated that suture closure of subcutaneous fat is associated with a 34% decrease in the risk of wound disruption in women with fat thickness greater than 2 cm (RR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.48–0.91).21

A recent systematic review of evidence-based guidelines for surgical decisions during cesarean delivery also recommended this practice based on results of 9 published studies.22 In this review, however, subcutaneous drain placement did not offer any additional benefit, regardless of tissue thickness.22

10 Avoid unproven techniques

Several commonly performed techniques have not been associated with a decreased risk of SSI after cesarean delivery

Dahlke JD, Mendez-Figueroa H, Rouse DJ, Berghella V, Baxter JK, Chauhan SP. Evidence-based surgery for cesarean delivery: an updated systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(4):294–306.

CORONIS Trial Collaborative Group. The CORONIS Trial. International study of caesarean section surgical techniques: a randomised fractional, factorial trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2007;7:24. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-7-24.

Familiarity with the obstetric literature will help providers determine which interventions prevent SSI and which do not. Well-designed clinical studies have demonstrated no significant difference in the rate of postcesarean infectious morbidity with the administration of high concentrations of perioperative oxygen,22 saline wound irrigation,22 placement of subcutaneous drains,22 blunt versus sharp abdominal entry,23 and exteriorization of the uterus for repair.23

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Infection is the second leading cause of pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, responsible for 13.6% of all maternal deaths.1 Cesarean delivery is the single most important risk factor for puerperal infection, increasing its incidence approximately 5- to 20-fold.2

Given that cesarean deliveries represent 32.7% of all births in the United States,3 the overall health and socioeconomic burden of these infections is substantial. In addition, more than half of all pregnancies are complicated by maternal obesity, which is associated with an increased risk of cesarean delivery as well as subsequent wound complications.4

In this review, we offer 10 evidence-based strategies to prevent surgical site infection (SSI) after cesarean delivery.

1 Maintain strict glycemic control in women with diabetes

Perioperative hyperglycemia is associated with an increased risk of postoperative infection in patients with diabetes

Ramos M, Khalpey Z, Lipsitz S, et al. Relationship of perioperative hyperglycemia and postoperative infections in patients who undergo general and vascular surgery. Ann Surg. 2008;248(4):585–591.

Hanazaki K, Maeda H, Okabayashi T. Relationship between perioperative glycemic control and postoperative infections. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(33):4122–4125.

Although data are limited on the impact of perioperative glycemic control on postcesarean infection rates, the association has been well documented in the general surgery literature. Results of a retrospective cohort study of 995 patients undergoing general or vascular surgery demonstrated that postoperative hyperglycemia increased the risk of infection by 30% for every 40-point increase in serum glucose levels from normoglycemia (defined as <110 mg/dL) (odds ratio, 1.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.03–1.64).5 Hyperglycemia causes abnormalities of leukocyte function, including impaired granulocyte adherence, impaired phagocytosis, delayed chemotaxis, and depressed bactericidal capacity. And all of these abnormalities in leukocyte function appear to improve with strict glycemic control, although the target range for blood glucose remains uncertain.6

2 Recommend preoperative antiseptic showering

Ask patients to shower with 4% chlorhexidine gluconate the night before surgery to reduce the presence of bacterial skin flora

Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, et al; Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection, 1999. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20(4):247–278.

Chlebicki MP, Safdar N, O’Horo JC, Maki DG. Preoperative chlorhexidine shower or bath for prevention of surgical site infection: a meta-analysis. Am J Infect Control. 2013;41(2):167–173.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, preoperative showering with chlorhexidine reduces the presence of bacterial skin flora. A study of more than 700 patients showed that preoperative showers with chlorhexidine reduced bacterial colony counts 9-fold, compared with only 1.3-fold for povidone-iodine.7 Whether this translates into a reduction in SSI remains controversial, in large part because of poor quality of the existing prospective trials, which used different agents, concentrations, and methods of skin preparation.8

Small clinical trials have found a benefit to chlorhexidine treatment the day before surgery.9,10 However, a recent meta-analysis of 16 randomized trials failed to show a significant reduction in the rate of SSI with chlorhexidine compared with soap, placebo, or no washing (relative risk [RR], 0.90; 95% CI, 0.77–1.05).11

3 Administer intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis

All patients who undergo cesarean delivery should be given appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis within 60 minutes before the skin incision

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 120: Use of prophylactic antibiotics in labor and delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(6):1472–1483.

Costantine MM, Rahman M, Ghulmiyah L, et al. Timing of perioperative antibiotics for cesarean delivery: a meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(3):301.e1–e6.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends the use of a single dose of a narrow-spectrum, first-generation cephalosporin (or a single dose of clindamycin with an aminoglycoside for those with a significant penicillin allergy) as SSI chemoprophylaxis for cesarean delivery.12 Due to concerns about fetal antibiotic exposure, such prophylaxis traditionally has been given after clamping of the umbilical cord. However, results of a recent meta-analysis of 5 randomized controlled trials demonstrated that antibiotic prophylaxis significantly reduced infectious morbidity (RR, 0.50; 95% CI, 0.33–0.78) when it was given 60 minutes before the skin incision, with no significant effect on neonatal outcome.13

4 Give a higher dose of preoperative antibiotics in obese women

Given the increased volume of distribution and the increased risk of postcesarean infection in the obese population, a higher dose of preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended

Robinson HE, O’Connell CM, Joseph KS, McLeod NL. Maternal outcomes in pregnancies complicated by obesity. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(6):1357–1364.

Pevzner L, Swank M, Krepel C, et al. Effects of maternal obesity on tissue concentrations of prophylactic cefazolin during cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(4):877–882.

The impact of maternal obesity on the risk of SSI after cesarean delivery was illustrated in a 2005 retrospective cohort study of 10,134 obese women. Moderately obese women with a prepregnancy weight of 90 to 100 kg were 1.6 times (95% CI, 1.31–1.95) more likely to have a wound infection, and severely obese women (>120 kg) were 4.45 times (95% CI, 3.00–6.61) more likely to have a wound infection after cesarean delivery, compared with women of normal weight.14

Moreover, a study of tissue concentrations of prophylactic cefazolin in obese women demonstrated that concentrations within adipose tissue at the site of the skin incision were inversely proportional to maternal body mass index (BMI).15 Given these findings, consideration should be given to using a higher dose of preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis in obese women, specifically 3 g of intravenous (IV) cefazolin for women with a BMI greater than 30 kg/m2 or an absolute weight of more than 100 kg.12

5 Use clippers for preoperative hair removal

If hair removal is necessary to perform the skin incision for cesarean delivery, the use of clippers is preferred

Tanner J, Norrie P, Melen K. Preoperative hair removal to reduce surgical site infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;11:CD004122.

In a Cochrane review of 3 randomized clinical trials comparing preoperative hair-removal techniques, shaving was associated with an increased risk of SSI, compared with clipping (RR, 2.09; 95% CI, 1.15–3.80).15 Shaving is thought to result in microscopic skin abrasions that can serve as foci for bacterial growth.

Interestingly, in this same Cochrane review, a separate analysis of 6 studies failed to show a benefit of preoperative hair removal by any means, compared with no hair removal,15 suggesting that routine hair removal may not be indicated for all patients.

6 Use chlorhexidine-alcohol for skin prep

Prepare the skin with chlorhexidine-alcohol immediately before surgery

Darouiche RO, Wall MJ Jr, Itani KM, et al. Chlorhexidine-alcohol versus povidone-iodine for surgical-site antisepsis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(1):18–26.

Kunkle CM, Marchan J, Safadi S, Whitman S, Chmait RH. Chlorhexidine gluconate versus povidone iodine at cesarean delivery: a randomized controlled trial. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014;18:1–5.

Data from a randomized multicenter trial of 849 patients showed that the use of a chlorhexidine-alcohol skin preparation immediately before surgery lowered the rate of SSI after clean-contaminated surgery, compared with povidone-iodine (RR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.41–0.85).16 Studies focusing on cesarean delivery alone are limited, although 1 small randomized trial found that chlorhexidine treatment significantly reduced bacterial growth at 18 hours after cesarean, compared with povidone-iodine (RR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.07–0.70).17

7 Consider an alcohol-based hand rub for preoperative antisepsis

Alcohol-based hand rubs may be more effective than conventional surgical scrub

Shen NJ, Pan SC, Sheng WH, et al. Comparative antimicrobial efficacy of alcohol-based hand rub and conventional surgical scrub in a medical center [published online ahead of print September 21, 2013]. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. pii:S1684–1182(13)00150–3.

Tanner J, Swarbrook S, Stuart J. Surgical hand antisepsis to reduce surgical site infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;1:CD004288.

Several agents are available for preoperative surgical hand antisepsis, including newer alcohol-based rubs and conventional aqueous scrubs that contain either chlorhexidine gluconate or povidone-iodine. In a prospective cohort study of 128 health care providers, use of an alcohol-based rub for surgical hand antisepsis was associated with a lower rate of positive bacterial culture (6.2%), compared with a chlorhexidine-based conventional scrub (47.6%; P<.001).18 However, if an aqueous-based scrub is the only option available for surgical hand antisepsis, a Cochrane review found that chlorhexidine gluconate scrubs were more effective than povidone-iodine scrubs in 3 trials, resulting in fewer colony-forming units of bacteria on the hands of the surgical team.19

8 Close the skin with subcuticular sutures

Use of subcuticular sutures for skin closure is associated with a lower risk of wound complications, compared with staples

Mackeen AD, Schuster M, Berghella V. Suture versus staples for skin closure after cesarean: a meta-analysis [published online ahead of print December 19, 2014]. Am J Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2014.12.020.

A meta-analysis of 12 randomized controlled trials including 3,112 women demonstrated that subcuticular closure is associated with a decreased risk of wound complications, compared with staple closure (RR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.28–0.87). The reduced risk remained significant even when stratified by obesity. Both closure techniques were shown to be equivalent with regard to postoperative pain, cosmetic outcome, and patient satisfaction.20

9 Close the subcutaneous tissue

Closure of the subcutaneous fat is associated with a decreased risk of wound disruption for women with a tissue thickness of more than 2 cm

Chelmow D, Rodriguez EJ, Sabatini MM. Suture closure of subcutaneous fat and wound disruption after cesarean delivery: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(5 pt 1):974–980.

Dahlke JD, Mendez-Figueroa H, Rouse DJ, Berghella V, Baxter JK, Chauhan SP. Evidence-based surgery for cesarean delivery: an updated systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(4):294–306.

A meta-analysis of 5 randomized controlled trials demonstrated that suture closure of subcutaneous fat is associated with a 34% decrease in the risk of wound disruption in women with fat thickness greater than 2 cm (RR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.48–0.91).21

A recent systematic review of evidence-based guidelines for surgical decisions during cesarean delivery also recommended this practice based on results of 9 published studies.22 In this review, however, subcutaneous drain placement did not offer any additional benefit, regardless of tissue thickness.22

10 Avoid unproven techniques

Several commonly performed techniques have not been associated with a decreased risk of SSI after cesarean delivery

Dahlke JD, Mendez-Figueroa H, Rouse DJ, Berghella V, Baxter JK, Chauhan SP. Evidence-based surgery for cesarean delivery: an updated systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(4):294–306.

CORONIS Trial Collaborative Group. The CORONIS Trial. International study of caesarean section surgical techniques: a randomised fractional, factorial trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2007;7:24. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-7-24.

Familiarity with the obstetric literature will help providers determine which interventions prevent SSI and which do not. Well-designed clinical studies have demonstrated no significant difference in the rate of postcesarean infectious morbidity with the administration of high concentrations of perioperative oxygen,22 saline wound irrigation,22 placement of subcutaneous drains,22 blunt versus sharp abdominal entry,23 and exteriorization of the uterus for repair.23

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Creanga AA, Berg CJ, Syverson C, Seed K, Bruce FC, Callaghan WM. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 2006–2010. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(1):5–12.

2. Leth RA, Moller JK, Thomsen RW, Uldbjerg N, Norgaard M. Risk of selected postpartum infections after cesarean section compared with vaginal birth: a five-year cohort study of 32,468 women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009;88(9):976–983.

3. Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman JK, et al. Births: final data for 2013. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64(1):1–65.

4. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 549: Obesity in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(1):213–217.

5. Dahlke JD, Mendez-Figueroa H, Rouse DJ, Berghella V, Baxter JK, Chauhan SP. Evidence-based surgery for cesarean delivery: an updated systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(4):294–306.

6. Ramos M, Khalpey Z, Lipsitz S, et al. Relationship of perioperative hyperglycemia and postoperative infections in patients who undergo general and vascular surgery. Ann Surg. 2008;248(4):585–591.

7. Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, Silver LC, Jarvis WR. Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee: Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection, 1999. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20(4):250–278.

8. Webster J, Osborne S. Preoperative bathing or showering with skin antiseptics to prevent surgical site infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9:CD004985.

9. Hayek LJ, Emerson JM, Gardner AM. A placebo-controlled trial of the effect of two preoperative baths or showers with chlorhexidine detergent on post-operative wound infection rates. J Hosp Infect. 1987;10(2):165–172.

10. Wihlborg O. The effect of washing with chlorhexidine soap on wound infection rate in general surgery: a controlled clinical study. Ann Chir Gynaecol. 1987;76(5):263–265.

11. Chlebicki MP, Safdar N, O’Horo JC, Maki DG. Preoperative chlorhexidine shower or bath for prevention of surgical site infection: a meta-analysis. Am J Infect Control. 2013;41(2):167–173.

12. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 120: Use of prophylactic antibiotics in labor and delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(6):1472–1483.

13. Costantine MM, Rahman M, Ghulmiyah L, et al. Timing of perioperative antibiotics for cesarean delivery: a meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(3):301.e1–e6.

14. Robinson HE, O’Connell CM, Joseph KS, McLeod NL. Maternal outcomes in pregnancies complicated by obesity. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(6):1357–1364.

15. Pevzner L, Swank M, Krepel C, et al. Effects of maternal obesity on tissue concentrations of prophylactic cefazolin during cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(4):877–882.

16. Tanner J, Norrie P, Melen K. Preoperative hair removal to reduce surgical site infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;11:CD004122.