User login

Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

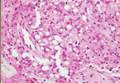

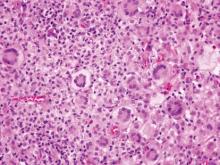

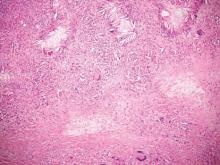

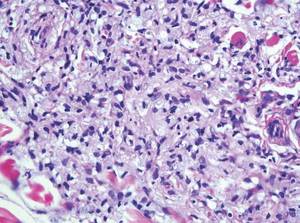

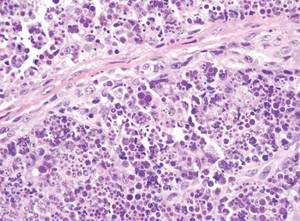

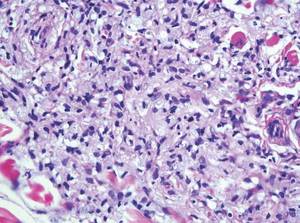

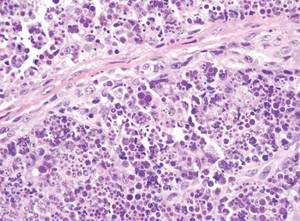

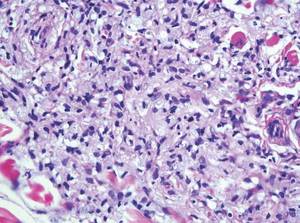

Cutaneous leishmaniasis is a parasitic infection caused by intracellular organisms found in tropical climates. Old World leishmaniasis is endemic to Asia, Africa, and parts of Europe, while New World leishmaniasis is native to Central and South Americas.1 Depending upon a host’s immune status and the specific Leishmania species, clinical presentations vary in appearance and severity, ranging from self-limited, localized cutaneous disease to potentially fatal visceral and mucocutaneous involvement. Most cutaneous manifestations of leishmaniasis begin as distinct, painless papules that may progress to nodules or become ulcerated over time.1 Histologically, leishmaniasis is diagnosed by the identification of intracellular organisms that characteristically align along the peripheral rim inside the vacuole of a histiocyte.2 This unique finding is called the “marquee sign” due to its resemblance to light bulbs arranged around a dressing room mirror (Figure 1).2Leishmania amastigotes (also known as Leishman-Donovan bodies) have kinetoplasts that are helpful in diagnosis but also may be difficult to detect.2 Along with the Leishmania parasites, there typically is a mixed inflammatory infiltrate of plasma cells, lymphocytes, histiocytes, and neutrophils (Figure 2).1,2 There also may be varying degrees of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and overlying epidermal ulceration.1

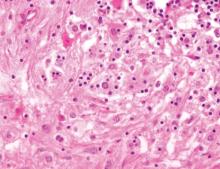

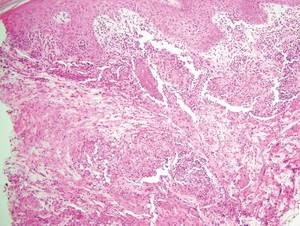

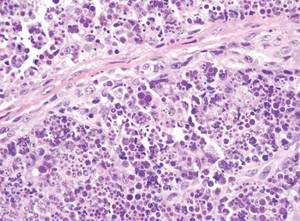

Cutaneous botryomycosis can present clinically as a number of various primary lesions, including papules, nodules, or ulcers that may resemble leishmaniasis.3 Botryomycosis represents a specific histologic collection of bacterial granules, most commonly caused by Staphylococcus aureus.3 The dermal granulomatous infiltrate seen in botryomycosis often is similar to that seen in chronic leishmaniasis; however, one histologic feature unique to botryomycosis is the presence of characteristic basophilic staphylococcal grains that are arranged in clusters resembling bunches of grapes (the term botryo means “bunch of grapes” in Greek).3 A thin, eosinophilic rim consisting of antibodies, bacterial debris, and complement proteins and glycoproteins may encircle the basophilic grains but does not need to be present for diagnosis (Figure 3).3

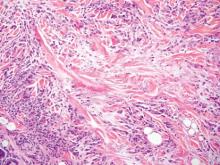

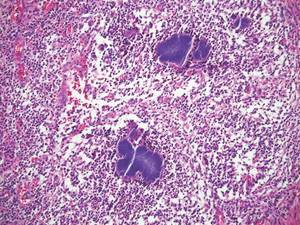

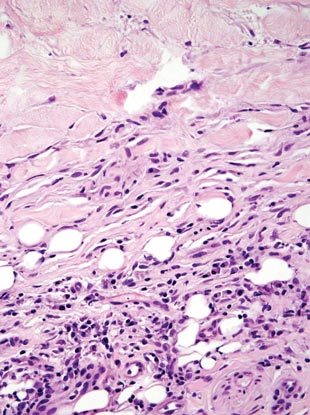

Lepromatous leprosy presents as a symmetric, widespread eruption of macules, patches, plaques, or papules that are most prominent in acral areas.4 Perivascular infiltration of lymphocytes and histiocytes is characteristic of lepromatous leprosy.2 Mycobacteria bacilli also are seen within histiocytic vacuoles, similarly to leishmaniasis; however, collections of these bacilli congregate within the center of a foamy histiocyte to form a distinctive histologic finding known as a globus. These individual histiocytes containing central globi are called Virchow cells (Figure 4).2 However, lepromatous leprosy can be distinguished from leishmaniasis histologically by carefully observing the intracellular location of the infectious organism. Mycobacteria bacilli are located in the center of a histiocyte vacuole whereas Leishmania parasites demonstrate a peripheral alignment along a histiocyte vacuole. If any uncertainty remains between a diagnosis of leishmaniasis and lepromatous leprosy, positive Fite staining for mycobacteria easily differentiates between the 2 conditions.2,4

Cutaneous lobomycosis, a rare fungal infection transmitted by dolphins, manifests clinically as an asymptomatic nodule that is similar in appearance to a keloid. Histologic similarities to leishmaniasis include pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and dermal granulomatous inflammation.4 The most distinguishing characteristic of lobomycosis is the presence of round, thick-walled, white organisms connected in a “string of beads” or chainlike configuration (Figure 5).2 Unlike leishmaniasis, lobomycosis fungal organisms would stain positive on periodic acid–Schiff staining.4

Cutaneous protothecosis is a rare clinical entity that presents as an isolated nodule or plaque or bursitis.4 It occurs following minor trauma and inoculation with Prototheca organisms, a genus of algae found in contaminated water.2,4 In its morula form, Prototheca adopts a characteristic arrangement within histiocytes that strikingly resembles a soccer ball (Figure 6).2 Conversely, nonmorulating forms of protothecosis can also be seen; these exhibit a central basophilic, dotlike structure within the histiocytes surrounded by a white halo.2 Definitive diagnosis of protothecosis can only be made upon successful culture of the algae.5

- Kevric I, Cappel MA, Keeling JH. New World and Old World leishmania infections: a practical review. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:579-593.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko CJ, et al. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. London, England: Elsevier Saunders; 2013.

- De Vries HJ, Van Noesel CJ, Hoekzema R, et al. Botryomycosis in an HIV-positive subject. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:87-90.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences UK; 2012.

- Hillesheim PB, Bahrami S. Cutaneous protothecosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:941-944.

Cutaneous leishmaniasis is a parasitic infection caused by intracellular organisms found in tropical climates. Old World leishmaniasis is endemic to Asia, Africa, and parts of Europe, while New World leishmaniasis is native to Central and South Americas.1 Depending upon a host’s immune status and the specific Leishmania species, clinical presentations vary in appearance and severity, ranging from self-limited, localized cutaneous disease to potentially fatal visceral and mucocutaneous involvement. Most cutaneous manifestations of leishmaniasis begin as distinct, painless papules that may progress to nodules or become ulcerated over time.1 Histologically, leishmaniasis is diagnosed by the identification of intracellular organisms that characteristically align along the peripheral rim inside the vacuole of a histiocyte.2 This unique finding is called the “marquee sign” due to its resemblance to light bulbs arranged around a dressing room mirror (Figure 1).2Leishmania amastigotes (also known as Leishman-Donovan bodies) have kinetoplasts that are helpful in diagnosis but also may be difficult to detect.2 Along with the Leishmania parasites, there typically is a mixed inflammatory infiltrate of plasma cells, lymphocytes, histiocytes, and neutrophils (Figure 2).1,2 There also may be varying degrees of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and overlying epidermal ulceration.1

Cutaneous botryomycosis can present clinically as a number of various primary lesions, including papules, nodules, or ulcers that may resemble leishmaniasis.3 Botryomycosis represents a specific histologic collection of bacterial granules, most commonly caused by Staphylococcus aureus.3 The dermal granulomatous infiltrate seen in botryomycosis often is similar to that seen in chronic leishmaniasis; however, one histologic feature unique to botryomycosis is the presence of characteristic basophilic staphylococcal grains that are arranged in clusters resembling bunches of grapes (the term botryo means “bunch of grapes” in Greek).3 A thin, eosinophilic rim consisting of antibodies, bacterial debris, and complement proteins and glycoproteins may encircle the basophilic grains but does not need to be present for diagnosis (Figure 3).3

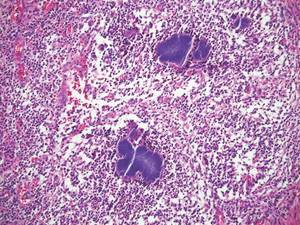

Lepromatous leprosy presents as a symmetric, widespread eruption of macules, patches, plaques, or papules that are most prominent in acral areas.4 Perivascular infiltration of lymphocytes and histiocytes is characteristic of lepromatous leprosy.2 Mycobacteria bacilli also are seen within histiocytic vacuoles, similarly to leishmaniasis; however, collections of these bacilli congregate within the center of a foamy histiocyte to form a distinctive histologic finding known as a globus. These individual histiocytes containing central globi are called Virchow cells (Figure 4).2 However, lepromatous leprosy can be distinguished from leishmaniasis histologically by carefully observing the intracellular location of the infectious organism. Mycobacteria bacilli are located in the center of a histiocyte vacuole whereas Leishmania parasites demonstrate a peripheral alignment along a histiocyte vacuole. If any uncertainty remains between a diagnosis of leishmaniasis and lepromatous leprosy, positive Fite staining for mycobacteria easily differentiates between the 2 conditions.2,4

Cutaneous lobomycosis, a rare fungal infection transmitted by dolphins, manifests clinically as an asymptomatic nodule that is similar in appearance to a keloid. Histologic similarities to leishmaniasis include pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and dermal granulomatous inflammation.4 The most distinguishing characteristic of lobomycosis is the presence of round, thick-walled, white organisms connected in a “string of beads” or chainlike configuration (Figure 5).2 Unlike leishmaniasis, lobomycosis fungal organisms would stain positive on periodic acid–Schiff staining.4

Cutaneous protothecosis is a rare clinical entity that presents as an isolated nodule or plaque or bursitis.4 It occurs following minor trauma and inoculation with Prototheca organisms, a genus of algae found in contaminated water.2,4 In its morula form, Prototheca adopts a characteristic arrangement within histiocytes that strikingly resembles a soccer ball (Figure 6).2 Conversely, nonmorulating forms of protothecosis can also be seen; these exhibit a central basophilic, dotlike structure within the histiocytes surrounded by a white halo.2 Definitive diagnosis of protothecosis can only be made upon successful culture of the algae.5

Cutaneous leishmaniasis is a parasitic infection caused by intracellular organisms found in tropical climates. Old World leishmaniasis is endemic to Asia, Africa, and parts of Europe, while New World leishmaniasis is native to Central and South Americas.1 Depending upon a host’s immune status and the specific Leishmania species, clinical presentations vary in appearance and severity, ranging from self-limited, localized cutaneous disease to potentially fatal visceral and mucocutaneous involvement. Most cutaneous manifestations of leishmaniasis begin as distinct, painless papules that may progress to nodules or become ulcerated over time.1 Histologically, leishmaniasis is diagnosed by the identification of intracellular organisms that characteristically align along the peripheral rim inside the vacuole of a histiocyte.2 This unique finding is called the “marquee sign” due to its resemblance to light bulbs arranged around a dressing room mirror (Figure 1).2Leishmania amastigotes (also known as Leishman-Donovan bodies) have kinetoplasts that are helpful in diagnosis but also may be difficult to detect.2 Along with the Leishmania parasites, there typically is a mixed inflammatory infiltrate of plasma cells, lymphocytes, histiocytes, and neutrophils (Figure 2).1,2 There also may be varying degrees of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and overlying epidermal ulceration.1

Cutaneous botryomycosis can present clinically as a number of various primary lesions, including papules, nodules, or ulcers that may resemble leishmaniasis.3 Botryomycosis represents a specific histologic collection of bacterial granules, most commonly caused by Staphylococcus aureus.3 The dermal granulomatous infiltrate seen in botryomycosis often is similar to that seen in chronic leishmaniasis; however, one histologic feature unique to botryomycosis is the presence of characteristic basophilic staphylococcal grains that are arranged in clusters resembling bunches of grapes (the term botryo means “bunch of grapes” in Greek).3 A thin, eosinophilic rim consisting of antibodies, bacterial debris, and complement proteins and glycoproteins may encircle the basophilic grains but does not need to be present for diagnosis (Figure 3).3

Lepromatous leprosy presents as a symmetric, widespread eruption of macules, patches, plaques, or papules that are most prominent in acral areas.4 Perivascular infiltration of lymphocytes and histiocytes is characteristic of lepromatous leprosy.2 Mycobacteria bacilli also are seen within histiocytic vacuoles, similarly to leishmaniasis; however, collections of these bacilli congregate within the center of a foamy histiocyte to form a distinctive histologic finding known as a globus. These individual histiocytes containing central globi are called Virchow cells (Figure 4).2 However, lepromatous leprosy can be distinguished from leishmaniasis histologically by carefully observing the intracellular location of the infectious organism. Mycobacteria bacilli are located in the center of a histiocyte vacuole whereas Leishmania parasites demonstrate a peripheral alignment along a histiocyte vacuole. If any uncertainty remains between a diagnosis of leishmaniasis and lepromatous leprosy, positive Fite staining for mycobacteria easily differentiates between the 2 conditions.2,4

Cutaneous lobomycosis, a rare fungal infection transmitted by dolphins, manifests clinically as an asymptomatic nodule that is similar in appearance to a keloid. Histologic similarities to leishmaniasis include pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and dermal granulomatous inflammation.4 The most distinguishing characteristic of lobomycosis is the presence of round, thick-walled, white organisms connected in a “string of beads” or chainlike configuration (Figure 5).2 Unlike leishmaniasis, lobomycosis fungal organisms would stain positive on periodic acid–Schiff staining.4

Cutaneous protothecosis is a rare clinical entity that presents as an isolated nodule or plaque or bursitis.4 It occurs following minor trauma and inoculation with Prototheca organisms, a genus of algae found in contaminated water.2,4 In its morula form, Prototheca adopts a characteristic arrangement within histiocytes that strikingly resembles a soccer ball (Figure 6).2 Conversely, nonmorulating forms of protothecosis can also be seen; these exhibit a central basophilic, dotlike structure within the histiocytes surrounded by a white halo.2 Definitive diagnosis of protothecosis can only be made upon successful culture of the algae.5

- Kevric I, Cappel MA, Keeling JH. New World and Old World leishmania infections: a practical review. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:579-593.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko CJ, et al. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. London, England: Elsevier Saunders; 2013.

- De Vries HJ, Van Noesel CJ, Hoekzema R, et al. Botryomycosis in an HIV-positive subject. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:87-90.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences UK; 2012.

- Hillesheim PB, Bahrami S. Cutaneous protothecosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:941-944.

- Kevric I, Cappel MA, Keeling JH. New World and Old World leishmania infections: a practical review. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:579-593.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko CJ, et al. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. London, England: Elsevier Saunders; 2013.

- De Vries HJ, Van Noesel CJ, Hoekzema R, et al. Botryomycosis in an HIV-positive subject. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:87-90.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences UK; 2012.

- Hillesheim PB, Bahrami S. Cutaneous protothecosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:941-944.

Necrobiosis Lipoidica Diabeticorum

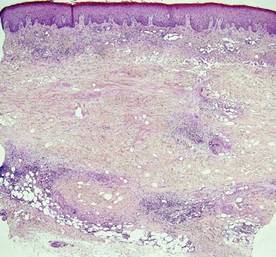

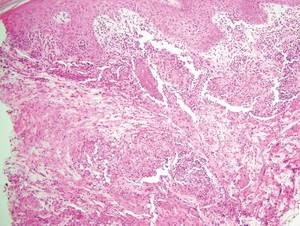

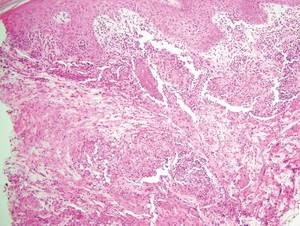

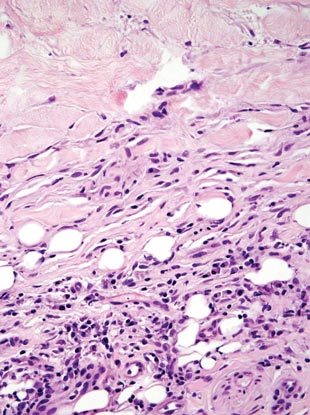

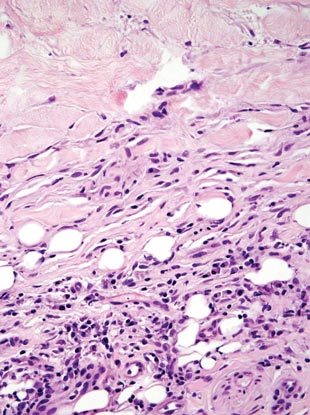

Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum (NLD) is a rare granulomatous skin manifestation that is strongly associated with diabetes mellitus. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum is more common among females and occurs primarily in the pretibial area.1 Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum may clinically manifest as single or multiple lesions that begin as small red papules and progress into patches or plaques. Lesions ultimately develop into areas of yellowish brown atrophic tissue with central depression and telangiectasia. The etiology of NLD is not completely understood, but it is thought to be a presentation of diabetic microangiopathy.1 Histologically, NLD demonstrates broad horizontal zones of necrobiosis with a surrounding inflammatory infiltrate that is principally composed of histiocytes but also may contain multinucleated giant cells, lymphocytes, and plasma cells (Figures 1 and 2). Occasionally, sarcoidal granulomas are seen in NLD. There also may be thickening of vessel walls and edema of the endothelial cells.1

|  |

Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD) is characterized by the presence of diffuse, large, pale histiocytes (commonly known as Rosai-Dorfman cells) with an admixed infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells (Figure 3).2 Additionally, Rosai-Dorfman cells display emperipolesis. They stain positively for S-100 protein and CD68 and negatively for CD1a.2 Clinically, cutaneous RDD has a myriad of manifestations but most commonly presents as cutaneous nodules that can be tender or pruritic. It also may be associated with systemic symptoms. Patients with cutaneous RDD often have an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and concomitant anemia.2

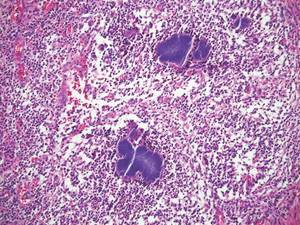

Granuloma annulare demonstrates necrobiosis and palisaded granulomatous dermatitis similar to NLD; however, the necrobiotic foci in granuloma annulare usually are more focal than in NLD and typically are surrounded by well-formed palisaded granulomas. There also is an increase in dermal mucin (Figure 4), which can be highlighted on colloidal iron or Alcian blue staining.1 Granuloma annulare also typically has scattered eosinophils rather than plasma cells as seen in NLD. Granuloma annulare also may present in an interstitial pattern, with scattered histiocytes, mucin, and eosinophils between collagen bundles. Granuloma annulare clinically presents as variably colored papules arranged in an annular pattern on the distal extremities but also can present as widespread papules or plaques.

Juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG) is a benign condition typically seen in children that is characterized by the presence of 1 or more pink or yellow nodules, most commonly presenting on the head and neck. Histologically, JXG demonstrates a dermal collection of histiocytes, lymphocytes, eosinophils, and characteristic Touton giant cells, which contain nuclei that are arranged in a wreathlike pattern and exhibit peripheral xanthomatization (Figure 5).3 The histiocytes in JXG typically stain positive for CD68 and negative for S-100 protein, though occasional S-100–positive cases are reported.3

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma presents as yellowish to brown plaques and nodules most commonly in the periorbital area. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is strongly associated with monoclonal gammopathy, typically IgGk monoclonal gammopathy. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is histologically similar to NLD but is distinguished by a nodular pattern of inflammation and the frequent presence of cholesterol clefts (Figure 6).4

Figure 6. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is distinguished by the nodularity

of the infiltrate, with necrobiotic collagen, palisaded histiocytes and giant

cells, and the presence of cholesterol clefts (H&E, original

magnification ×40).

1. Kota SK, Jammula S, Kota SK, et al. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum: a case-based review of literature. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:614-620.

2. Khoo JJ, Rahmat BO. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease. Malays J Pathol. 2007;29:49-52.

3. Cypel TK, Zuker RM. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: case report and review of the literature. Can J Plast Surg. 2008;16:175-177.

4. Inthasotti S, Wanitphakdeedecha R, Manonukul J. A 7-year history of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma following asymptomatic multiple myeloma: a case report. Dermatol Res Pract. 2011;2011:927852.

Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum (NLD) is a rare granulomatous skin manifestation that is strongly associated with diabetes mellitus. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum is more common among females and occurs primarily in the pretibial area.1 Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum may clinically manifest as single or multiple lesions that begin as small red papules and progress into patches or plaques. Lesions ultimately develop into areas of yellowish brown atrophic tissue with central depression and telangiectasia. The etiology of NLD is not completely understood, but it is thought to be a presentation of diabetic microangiopathy.1 Histologically, NLD demonstrates broad horizontal zones of necrobiosis with a surrounding inflammatory infiltrate that is principally composed of histiocytes but also may contain multinucleated giant cells, lymphocytes, and plasma cells (Figures 1 and 2). Occasionally, sarcoidal granulomas are seen in NLD. There also may be thickening of vessel walls and edema of the endothelial cells.1

|  |

Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD) is characterized by the presence of diffuse, large, pale histiocytes (commonly known as Rosai-Dorfman cells) with an admixed infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells (Figure 3).2 Additionally, Rosai-Dorfman cells display emperipolesis. They stain positively for S-100 protein and CD68 and negatively for CD1a.2 Clinically, cutaneous RDD has a myriad of manifestations but most commonly presents as cutaneous nodules that can be tender or pruritic. It also may be associated with systemic symptoms. Patients with cutaneous RDD often have an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and concomitant anemia.2

Granuloma annulare demonstrates necrobiosis and palisaded granulomatous dermatitis similar to NLD; however, the necrobiotic foci in granuloma annulare usually are more focal than in NLD and typically are surrounded by well-formed palisaded granulomas. There also is an increase in dermal mucin (Figure 4), which can be highlighted on colloidal iron or Alcian blue staining.1 Granuloma annulare also typically has scattered eosinophils rather than plasma cells as seen in NLD. Granuloma annulare also may present in an interstitial pattern, with scattered histiocytes, mucin, and eosinophils between collagen bundles. Granuloma annulare clinically presents as variably colored papules arranged in an annular pattern on the distal extremities but also can present as widespread papules or plaques.

Juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG) is a benign condition typically seen in children that is characterized by the presence of 1 or more pink or yellow nodules, most commonly presenting on the head and neck. Histologically, JXG demonstrates a dermal collection of histiocytes, lymphocytes, eosinophils, and characteristic Touton giant cells, which contain nuclei that are arranged in a wreathlike pattern and exhibit peripheral xanthomatization (Figure 5).3 The histiocytes in JXG typically stain positive for CD68 and negative for S-100 protein, though occasional S-100–positive cases are reported.3

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma presents as yellowish to brown plaques and nodules most commonly in the periorbital area. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is strongly associated with monoclonal gammopathy, typically IgGk monoclonal gammopathy. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is histologically similar to NLD but is distinguished by a nodular pattern of inflammation and the frequent presence of cholesterol clefts (Figure 6).4

Figure 6. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is distinguished by the nodularity

of the infiltrate, with necrobiotic collagen, palisaded histiocytes and giant

cells, and the presence of cholesterol clefts (H&E, original

magnification ×40).

Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum (NLD) is a rare granulomatous skin manifestation that is strongly associated with diabetes mellitus. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum is more common among females and occurs primarily in the pretibial area.1 Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum may clinically manifest as single or multiple lesions that begin as small red papules and progress into patches or plaques. Lesions ultimately develop into areas of yellowish brown atrophic tissue with central depression and telangiectasia. The etiology of NLD is not completely understood, but it is thought to be a presentation of diabetic microangiopathy.1 Histologically, NLD demonstrates broad horizontal zones of necrobiosis with a surrounding inflammatory infiltrate that is principally composed of histiocytes but also may contain multinucleated giant cells, lymphocytes, and plasma cells (Figures 1 and 2). Occasionally, sarcoidal granulomas are seen in NLD. There also may be thickening of vessel walls and edema of the endothelial cells.1

|  |

Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD) is characterized by the presence of diffuse, large, pale histiocytes (commonly known as Rosai-Dorfman cells) with an admixed infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells (Figure 3).2 Additionally, Rosai-Dorfman cells display emperipolesis. They stain positively for S-100 protein and CD68 and negatively for CD1a.2 Clinically, cutaneous RDD has a myriad of manifestations but most commonly presents as cutaneous nodules that can be tender or pruritic. It also may be associated with systemic symptoms. Patients with cutaneous RDD often have an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and concomitant anemia.2

Granuloma annulare demonstrates necrobiosis and palisaded granulomatous dermatitis similar to NLD; however, the necrobiotic foci in granuloma annulare usually are more focal than in NLD and typically are surrounded by well-formed palisaded granulomas. There also is an increase in dermal mucin (Figure 4), which can be highlighted on colloidal iron or Alcian blue staining.1 Granuloma annulare also typically has scattered eosinophils rather than plasma cells as seen in NLD. Granuloma annulare also may present in an interstitial pattern, with scattered histiocytes, mucin, and eosinophils between collagen bundles. Granuloma annulare clinically presents as variably colored papules arranged in an annular pattern on the distal extremities but also can present as widespread papules or plaques.

Juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG) is a benign condition typically seen in children that is characterized by the presence of 1 or more pink or yellow nodules, most commonly presenting on the head and neck. Histologically, JXG demonstrates a dermal collection of histiocytes, lymphocytes, eosinophils, and characteristic Touton giant cells, which contain nuclei that are arranged in a wreathlike pattern and exhibit peripheral xanthomatization (Figure 5).3 The histiocytes in JXG typically stain positive for CD68 and negative for S-100 protein, though occasional S-100–positive cases are reported.3

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma presents as yellowish to brown plaques and nodules most commonly in the periorbital area. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is strongly associated with monoclonal gammopathy, typically IgGk monoclonal gammopathy. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is histologically similar to NLD but is distinguished by a nodular pattern of inflammation and the frequent presence of cholesterol clefts (Figure 6).4

Figure 6. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is distinguished by the nodularity

of the infiltrate, with necrobiotic collagen, palisaded histiocytes and giant

cells, and the presence of cholesterol clefts (H&E, original

magnification ×40).

1. Kota SK, Jammula S, Kota SK, et al. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum: a case-based review of literature. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:614-620.

2. Khoo JJ, Rahmat BO. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease. Malays J Pathol. 2007;29:49-52.

3. Cypel TK, Zuker RM. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: case report and review of the literature. Can J Plast Surg. 2008;16:175-177.

4. Inthasotti S, Wanitphakdeedecha R, Manonukul J. A 7-year history of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma following asymptomatic multiple myeloma: a case report. Dermatol Res Pract. 2011;2011:927852.

1. Kota SK, Jammula S, Kota SK, et al. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum: a case-based review of literature. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:614-620.

2. Khoo JJ, Rahmat BO. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease. Malays J Pathol. 2007;29:49-52.

3. Cypel TK, Zuker RM. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: case report and review of the literature. Can J Plast Surg. 2008;16:175-177.

4. Inthasotti S, Wanitphakdeedecha R, Manonukul J. A 7-year history of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma following asymptomatic multiple myeloma: a case report. Dermatol Res Pract. 2011;2011:927852.