User login

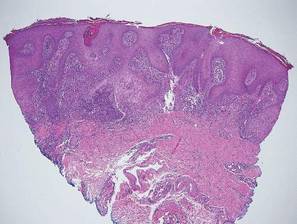

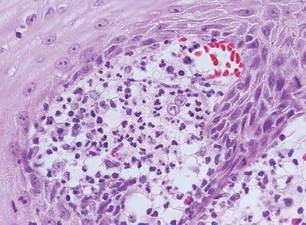

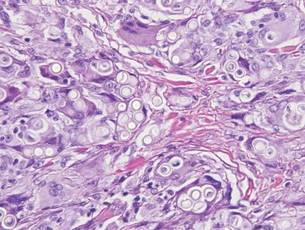

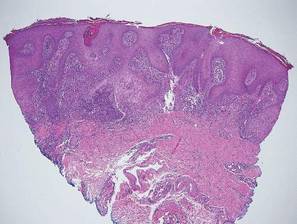

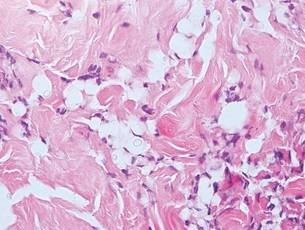

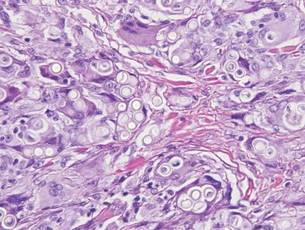

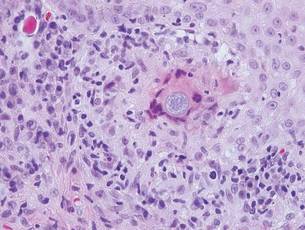

Chromoblastomycosis is a chronic fungal infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissues that demonstrates characteristic Medlar or sclerotic bodies that resemble copper pennies on histopathology.1 Cutaneous infection often results from direct inoculation, such as from a wood splinter. Clinically, the lesion typically is a pink papule that progresses to a verrucous plaque on the legs of farmers or rural workers in the tropics or subtropics. There usually are no associated constitutional symptoms. Several dematiaceous (darkly pigmented) fungi cause chromoblastomycosis, including Fonsecaea compacta, Cladophialophora carrionii, Rhinocladiella aquaspersa, Phialophora verrucosa, and Fonsecaea pedrosoi. Cellular division occurs by internal septation rather than budding. Skin biopsy can confirm the diagnosis.1 Chromoblastomycosis is histopathologically characterized by pseudoepitheli- omatous hyperplasia (Figure 1) with histiocytes and neutrophils surrounding distinct copper-colored Medlar bodies (6–12 μm)(Figure 2), which are fungal spores.1-3 Several conditions demonstrate pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal pustules and can be remembered by the mnemonic “here come big green leafy vegetables”: halogenoderma, chromoblastomycosis, blastomycosis, granuloma inguinale, leishmaniasis, and pemphigus vegetans.2 Treatment of chromoblastomycosis can be challenging, as no standard treatment has been established and therapy can be complicated by low cure rates and high relapse rates, especially in chronic and extensive disease. Treatment can include cryotherapy or surgical excision for small lesions in combination with systemic antifungals.4 Itraconazole (200–400 mg daily) for at least 6 months has been reported to have up to a 90% cure rate with mild to moderate disease and 44% with severe disease.5 Combination oral antifungal treatment with itraconazole and terbinafine has been recommended.6 There are reports of progression of chromoblastomycosis to squamous cell carcinoma, which is rare and occurred after long-standing, inadequately treated lesions.7

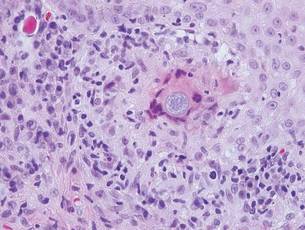

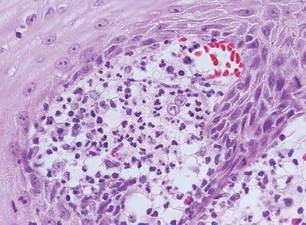

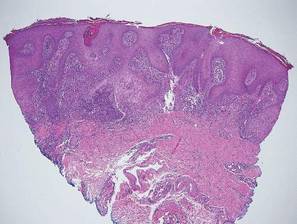

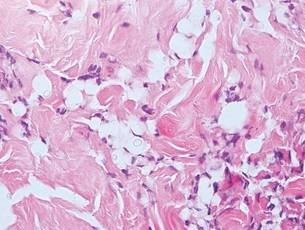

Blastomycosis also presents with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, as seen in chromoblastomycosis, but organisms typically are few in number and demonstrate a thick, asymmetrical, refractile wall and a dark nucleus. Although chromoblastomycosis and blastomycosis are similar in size (8–15 μm), the broad-based budding of blastomycosis (Figure 3) is a key feature and the yeast are not pigmented.1-3 Blastomycosis is caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis and is endemic to the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys, Great Lakes region, and Southeastern United States. Cutaneous infection typically occurs from inhalation of the dimorphic fungi into the lungs and occasional dissemination involving the skin, causing papulopustules and thick, crusted, warty plaques with central ulceration. Rarely, primary cutaneous blastomycosis can occur from direct inoculation, typically in a laboratory. Treatment of disseminated blastomycosis includes systemic antifungals.1

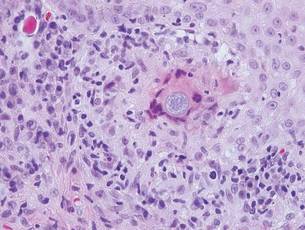

Coccidioidomycosis is characterized by large spherules (10–80 μm) with refractile walls and granular gray cytoplasm.2,3 Coccidioidomycosis spherules occasionally contain endospores2 and often are noticeably larger than surrounding histiocyte nuclei (Figure 4), whereas chromoblastomycosis, blastomycosis, cryptococcosis, and lobomycosis are more similar in size to histiocyte nuclei. Coccidioidomycosis is caused by Coccidioides immitis, a highly virulent dimorphic fungus found in the Southwestern United States, northern Mexico, and Central and South America. Pulmonary infection occurs by inhalation of arthroconidia, often from soil, and is asymptomatic in most patients; however, immunocompromised patients are predisposed to disseminated cutaneous infection. Facial lesions are most common and can present as papules, pustules, plaques, abscesses, sinus tracts, and/or ulcerations. Treatment of disseminated infection requires systemic antifungals; amphotericin B has proven most effective.1

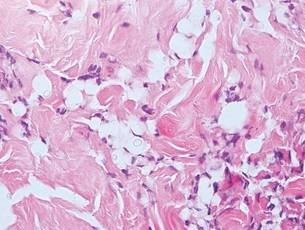

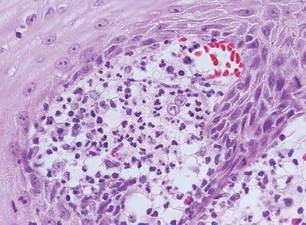

Cryptococcosis is characterized by vacuoles with small (2–20 μm), central, pleomorphic yeast (Figure 5). The vacuole is due to a gelati- nous capsule that stains red with mucicarmine and blue with Alcian blue.2,3 Cryptococcosis is caused by Cryptococcus neoformans and is associated with pigeon droppings. Disseminated infection in patients with human immunodefi- ciency virus often presents as umbilicated molluscumlike lesions and portends a poor prognosis with a mortality rate of up to 80%.8 Disseminated infection necessitates aggressive treatment with systemic antifungals.1

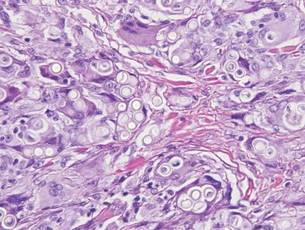

Lobomycosis demonstrates thick-walled, refractile spherules with surrounding histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. The yeast of lobomycosis (6–12 μm) is of similar size to chromoblastomycosis and blastomycosis, but linear chains resembling a child’s pop beads are characteristic of this condition (Figure 6).2,3 Lobomycosis is caused by Lacazia loboi and is acquired most frequently through contact with dolphins in Central and South America. Clinically, lesions present as slow-growing, keloidlike nodules, often on the face, ears, and distal extremities. Surgical treatment may be required given that oral antifungals typically are ineffective.1

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Shaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2012.

- Elston DM, Ferringer TC, Ko C, et al. Dermatopathology: Requisites in Dermatology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2014.

- Fernandez-Flores A, Saeb-Lima M, Arenas-Guzman R. Morphological findings of deep cutaneous fungal infections. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:531-556.

- Ameen M. Chromoblastomycosis: clinical presentation and management. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:849-854.

- Queiroz-Telles F, McGinnis MR, Salkin I, et al. Subcutaneous mycoses. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2003;17:59-85.

- Bonifaz A, Paredes-Solís, Saúl A. Treating chromoblastomycosis with systemic antifungals. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2004;5:247-254.

- Rojas OC, González GM, Moreno-Treviño M, et al. Chromoblastomycosis by Cladophialophora carrionii associated with squamous cell carcinoma and review of published reports. Mycopathologia. 2015;179:153-157.

- Durden FM, Elewski B. Cutaneous involvement with Cryptococcus neoformans in AIDS. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:844-848.

Chromoblastomycosis is a chronic fungal infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissues that demonstrates characteristic Medlar or sclerotic bodies that resemble copper pennies on histopathology.1 Cutaneous infection often results from direct inoculation, such as from a wood splinter. Clinically, the lesion typically is a pink papule that progresses to a verrucous plaque on the legs of farmers or rural workers in the tropics or subtropics. There usually are no associated constitutional symptoms. Several dematiaceous (darkly pigmented) fungi cause chromoblastomycosis, including Fonsecaea compacta, Cladophialophora carrionii, Rhinocladiella aquaspersa, Phialophora verrucosa, and Fonsecaea pedrosoi. Cellular division occurs by internal septation rather than budding. Skin biopsy can confirm the diagnosis.1 Chromoblastomycosis is histopathologically characterized by pseudoepitheli- omatous hyperplasia (Figure 1) with histiocytes and neutrophils surrounding distinct copper-colored Medlar bodies (6–12 μm)(Figure 2), which are fungal spores.1-3 Several conditions demonstrate pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal pustules and can be remembered by the mnemonic “here come big green leafy vegetables”: halogenoderma, chromoblastomycosis, blastomycosis, granuloma inguinale, leishmaniasis, and pemphigus vegetans.2 Treatment of chromoblastomycosis can be challenging, as no standard treatment has been established and therapy can be complicated by low cure rates and high relapse rates, especially in chronic and extensive disease. Treatment can include cryotherapy or surgical excision for small lesions in combination with systemic antifungals.4 Itraconazole (200–400 mg daily) for at least 6 months has been reported to have up to a 90% cure rate with mild to moderate disease and 44% with severe disease.5 Combination oral antifungal treatment with itraconazole and terbinafine has been recommended.6 There are reports of progression of chromoblastomycosis to squamous cell carcinoma, which is rare and occurred after long-standing, inadequately treated lesions.7

Blastomycosis also presents with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, as seen in chromoblastomycosis, but organisms typically are few in number and demonstrate a thick, asymmetrical, refractile wall and a dark nucleus. Although chromoblastomycosis and blastomycosis are similar in size (8–15 μm), the broad-based budding of blastomycosis (Figure 3) is a key feature and the yeast are not pigmented.1-3 Blastomycosis is caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis and is endemic to the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys, Great Lakes region, and Southeastern United States. Cutaneous infection typically occurs from inhalation of the dimorphic fungi into the lungs and occasional dissemination involving the skin, causing papulopustules and thick, crusted, warty plaques with central ulceration. Rarely, primary cutaneous blastomycosis can occur from direct inoculation, typically in a laboratory. Treatment of disseminated blastomycosis includes systemic antifungals.1

Coccidioidomycosis is characterized by large spherules (10–80 μm) with refractile walls and granular gray cytoplasm.2,3 Coccidioidomycosis spherules occasionally contain endospores2 and often are noticeably larger than surrounding histiocyte nuclei (Figure 4), whereas chromoblastomycosis, blastomycosis, cryptococcosis, and lobomycosis are more similar in size to histiocyte nuclei. Coccidioidomycosis is caused by Coccidioides immitis, a highly virulent dimorphic fungus found in the Southwestern United States, northern Mexico, and Central and South America. Pulmonary infection occurs by inhalation of arthroconidia, often from soil, and is asymptomatic in most patients; however, immunocompromised patients are predisposed to disseminated cutaneous infection. Facial lesions are most common and can present as papules, pustules, plaques, abscesses, sinus tracts, and/or ulcerations. Treatment of disseminated infection requires systemic antifungals; amphotericin B has proven most effective.1

Cryptococcosis is characterized by vacuoles with small (2–20 μm), central, pleomorphic yeast (Figure 5). The vacuole is due to a gelati- nous capsule that stains red with mucicarmine and blue with Alcian blue.2,3 Cryptococcosis is caused by Cryptococcus neoformans and is associated with pigeon droppings. Disseminated infection in patients with human immunodefi- ciency virus often presents as umbilicated molluscumlike lesions and portends a poor prognosis with a mortality rate of up to 80%.8 Disseminated infection necessitates aggressive treatment with systemic antifungals.1

Lobomycosis demonstrates thick-walled, refractile spherules with surrounding histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. The yeast of lobomycosis (6–12 μm) is of similar size to chromoblastomycosis and blastomycosis, but linear chains resembling a child’s pop beads are characteristic of this condition (Figure 6).2,3 Lobomycosis is caused by Lacazia loboi and is acquired most frequently through contact with dolphins in Central and South America. Clinically, lesions present as slow-growing, keloidlike nodules, often on the face, ears, and distal extremities. Surgical treatment may be required given that oral antifungals typically are ineffective.1

Chromoblastomycosis is a chronic fungal infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissues that demonstrates characteristic Medlar or sclerotic bodies that resemble copper pennies on histopathology.1 Cutaneous infection often results from direct inoculation, such as from a wood splinter. Clinically, the lesion typically is a pink papule that progresses to a verrucous plaque on the legs of farmers or rural workers in the tropics or subtropics. There usually are no associated constitutional symptoms. Several dematiaceous (darkly pigmented) fungi cause chromoblastomycosis, including Fonsecaea compacta, Cladophialophora carrionii, Rhinocladiella aquaspersa, Phialophora verrucosa, and Fonsecaea pedrosoi. Cellular division occurs by internal septation rather than budding. Skin biopsy can confirm the diagnosis.1 Chromoblastomycosis is histopathologically characterized by pseudoepitheli- omatous hyperplasia (Figure 1) with histiocytes and neutrophils surrounding distinct copper-colored Medlar bodies (6–12 μm)(Figure 2), which are fungal spores.1-3 Several conditions demonstrate pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal pustules and can be remembered by the mnemonic “here come big green leafy vegetables”: halogenoderma, chromoblastomycosis, blastomycosis, granuloma inguinale, leishmaniasis, and pemphigus vegetans.2 Treatment of chromoblastomycosis can be challenging, as no standard treatment has been established and therapy can be complicated by low cure rates and high relapse rates, especially in chronic and extensive disease. Treatment can include cryotherapy or surgical excision for small lesions in combination with systemic antifungals.4 Itraconazole (200–400 mg daily) for at least 6 months has been reported to have up to a 90% cure rate with mild to moderate disease and 44% with severe disease.5 Combination oral antifungal treatment with itraconazole and terbinafine has been recommended.6 There are reports of progression of chromoblastomycosis to squamous cell carcinoma, which is rare and occurred after long-standing, inadequately treated lesions.7

Blastomycosis also presents with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, as seen in chromoblastomycosis, but organisms typically are few in number and demonstrate a thick, asymmetrical, refractile wall and a dark nucleus. Although chromoblastomycosis and blastomycosis are similar in size (8–15 μm), the broad-based budding of blastomycosis (Figure 3) is a key feature and the yeast are not pigmented.1-3 Blastomycosis is caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis and is endemic to the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys, Great Lakes region, and Southeastern United States. Cutaneous infection typically occurs from inhalation of the dimorphic fungi into the lungs and occasional dissemination involving the skin, causing papulopustules and thick, crusted, warty plaques with central ulceration. Rarely, primary cutaneous blastomycosis can occur from direct inoculation, typically in a laboratory. Treatment of disseminated blastomycosis includes systemic antifungals.1

Coccidioidomycosis is characterized by large spherules (10–80 μm) with refractile walls and granular gray cytoplasm.2,3 Coccidioidomycosis spherules occasionally contain endospores2 and often are noticeably larger than surrounding histiocyte nuclei (Figure 4), whereas chromoblastomycosis, blastomycosis, cryptococcosis, and lobomycosis are more similar in size to histiocyte nuclei. Coccidioidomycosis is caused by Coccidioides immitis, a highly virulent dimorphic fungus found in the Southwestern United States, northern Mexico, and Central and South America. Pulmonary infection occurs by inhalation of arthroconidia, often from soil, and is asymptomatic in most patients; however, immunocompromised patients are predisposed to disseminated cutaneous infection. Facial lesions are most common and can present as papules, pustules, plaques, abscesses, sinus tracts, and/or ulcerations. Treatment of disseminated infection requires systemic antifungals; amphotericin B has proven most effective.1

Cryptococcosis is characterized by vacuoles with small (2–20 μm), central, pleomorphic yeast (Figure 5). The vacuole is due to a gelati- nous capsule that stains red with mucicarmine and blue with Alcian blue.2,3 Cryptococcosis is caused by Cryptococcus neoformans and is associated with pigeon droppings. Disseminated infection in patients with human immunodefi- ciency virus often presents as umbilicated molluscumlike lesions and portends a poor prognosis with a mortality rate of up to 80%.8 Disseminated infection necessitates aggressive treatment with systemic antifungals.1

Lobomycosis demonstrates thick-walled, refractile spherules with surrounding histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. The yeast of lobomycosis (6–12 μm) is of similar size to chromoblastomycosis and blastomycosis, but linear chains resembling a child’s pop beads are characteristic of this condition (Figure 6).2,3 Lobomycosis is caused by Lacazia loboi and is acquired most frequently through contact with dolphins in Central and South America. Clinically, lesions present as slow-growing, keloidlike nodules, often on the face, ears, and distal extremities. Surgical treatment may be required given that oral antifungals typically are ineffective.1

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Shaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2012.

- Elston DM, Ferringer TC, Ko C, et al. Dermatopathology: Requisites in Dermatology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2014.

- Fernandez-Flores A, Saeb-Lima M, Arenas-Guzman R. Morphological findings of deep cutaneous fungal infections. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:531-556.

- Ameen M. Chromoblastomycosis: clinical presentation and management. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:849-854.

- Queiroz-Telles F, McGinnis MR, Salkin I, et al. Subcutaneous mycoses. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2003;17:59-85.

- Bonifaz A, Paredes-Solís, Saúl A. Treating chromoblastomycosis with systemic antifungals. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2004;5:247-254.

- Rojas OC, González GM, Moreno-Treviño M, et al. Chromoblastomycosis by Cladophialophora carrionii associated with squamous cell carcinoma and review of published reports. Mycopathologia. 2015;179:153-157.

- Durden FM, Elewski B. Cutaneous involvement with Cryptococcus neoformans in AIDS. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:844-848.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Shaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2012.

- Elston DM, Ferringer TC, Ko C, et al. Dermatopathology: Requisites in Dermatology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2014.

- Fernandez-Flores A, Saeb-Lima M, Arenas-Guzman R. Morphological findings of deep cutaneous fungal infections. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:531-556.

- Ameen M. Chromoblastomycosis: clinical presentation and management. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:849-854.

- Queiroz-Telles F, McGinnis MR, Salkin I, et al. Subcutaneous mycoses. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2003;17:59-85.

- Bonifaz A, Paredes-Solís, Saúl A. Treating chromoblastomycosis with systemic antifungals. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2004;5:247-254.

- Rojas OC, González GM, Moreno-Treviño M, et al. Chromoblastomycosis by Cladophialophora carrionii associated with squamous cell carcinoma and review of published reports. Mycopathologia. 2015;179:153-157.

- Durden FM, Elewski B. Cutaneous involvement with Cryptococcus neoformans in AIDS. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:844-848.