User login

Nodular Scleroderma in a Patient With Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection: A Coexistent or Causal Infection?

Case Report

A 63-year-old woman was referred to our clinic for evaluation of multiple papules and nodules on the neck and trunk that had been present for 2 years. Three years prior to presentation she had been diagnosed with systemic sclerosis (SSc) after developing progressive diffuse cutaneous sclerosis, Raynaud phenomenon with digital pitted scarring, esophageal dysmotility, myositis, pericardial effusion, and interstitial lung disease. Serologic test results were positive for anti-Scl-70 antibodies. Antinuclear antibody test results were negative for anti–double-stranded DNA, anti-nRNP, anti-Ro/La, anti-Sm, and anti-Jo-1 antibodies. The patient was treated with prednisolone 7.5 mg daily, nifedipine 15 mg daily, valsartan 80 mg daily, manidipine 20 mg daily, omeprazole 20 mg daily, and beraprost 80 mg daily. One year later, numerous asymptomatic flesh-colored papules and nodules developed on the neck, chest, abdomen, and back. There was no history of trauma or surgery at any of the affected sites.

On further investigation, anti–hepatitis C virus (HCV) antibodies were identified and confirmed by HCV ribonucleic acid polymerase chain reaction at the same time that the diagnosis of SSc was established. Hepatitis C virus genotype 3a was noted, and the patient’s viral load was 378,000 IU/mL. Therefore, a diagnosis of chronic HCV infection was established. The patient was initially unable to receive medical treatment due to lack of finances. A year and a half following the diagnosis of HCV infection, with worsening liver function tests and increasing viral load (1,369,113 IU/mL), the patient began therapy with peginterferon alfa-2b 80 mg weekly and ribavirin 800 mg daily. However, the medications were discontinued after 2 months when she developed severe hemolytic anemia related to ribavirin.

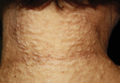

On physical examination, the patient was noted to have a masklike facies with a pinched nose and constricted opening of the mouth. Her skin was tightened and stiff extending from the fingers to the proximal extremities. Numerous well-circumscribed, flesh-colored, firm papules and nodules ranging from 2 to 20 mm in diameter were present on the neck (Figure 1), chest, abdomen (Figure 2), and back.

|

|

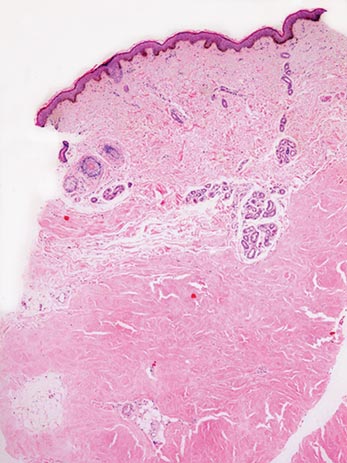

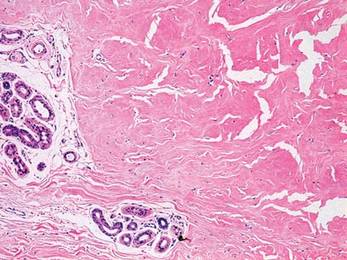

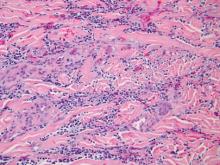

Two 4-mm punch biopsy samples obtained from a papule on the neck and a nodule on the abdomen revealed homogenized collagen bundles with scattered plump fibroblasts in the lower reticular dermis. Clinicopathologic correlation of the biopsy findings with the cutaneous examination resulted in a diagnosis of nodular scleroderma (Figures 3 and 4).

|

The patient began treatment with intralesional injections of triamcinolone 5 to 10 mg/mL for nodules as well as an ultrapotent corticosteroid cream, clobetasol propionate 0.05%, for small papules. Injections were performed at 4- to 8-week intervals and resulted in modest clinical improvement.

Comment

Scleroderma may be present only in the skin (morphea) or as a systemic disease (systemic scleroderma). Rarely, cutaneous involvement can exhibit a nodular or hypertrophic morphology, which has been described in the literature as nodular or keloidal scleroderma in a patient with known SSc1-10 and as nodular or keloidal morphea in localized cutaneous scleroderma.3,11-13

Histopathology

The distinction between the terms nodular scleroderma and keloidal scleroderma is not clear, and they are not necessarily interchangeable. To provide clarity, we find it useful to delineate specific histologic findings associated with the diagnoses of keloid, scleroderma, and the uncommon keloid/scleroderma overlap. The histopathologic findings of keloids include a fibrotic dermis and broad dispersed bundles of eosinophilic hyalinized collagen. The histopathologic findings of scleroderma include broad sclerotic bands of collagen throughout the dermis with loss of perieccrine fat. In the overlapping keloid/scleroderma condition, which is a variant of scleroderma, hyalinized collagen fibers and keloidal collagen appear in the same specimen.3,4

To distinguish these conditions, Barzilai et al5 proposed that only cases showing both clinical and histologic characteristics of a keloid should be referred to as keloidal morphea/scleroderma. They further stated that the terms nodular morphea or nodular scleroderma ought to be used only for cases that are indistinguishable histologically from scleroderma. The term morphea is appropriate when only a limited amount of skin disease is present, while scleroderma implies association with systemic disease.5 Likely, there is a histologic continuum in this variant of scleroderma, in which nodular morphea/scleroderma exists at one end and keloidal morphea/scleroderma exists at the other end.5,13

In the case of our patient, papulonodular lesions developed 1 year after the diagnosis of SSc was made, and the histopathologic examination revealed classic findings of scleroderma. As a result, our patient is most appropriately classified as having nodular scleroderma.

Clinical Features

Nodular scleroderma mostly affects young and middle-aged women and is clinically characterized by solitary or multiple firm, long-lasting papules or nodules on the upper trunk and chest, neck, and proximal extremities.1-4,6

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The triggers and cellular mechanisms of nodular scleroderma are unclear. Some authors have implicated matricellular protein and growth factors such as tenascin, connective tissue growth factor, and epidermal growth factor in nodule formation.7,8,11 Yamamoto et al9 cited chemical exposure to a silica-containing abrasive as the cause of nodular scleroderma in a worker.

Possible HCV Association

Some reports have indicated an association between nodular scleroderma and pathogens such as acid-fast bacteria10 and HCV.6 Of note, many extrahepatic conditions have been associated with HCV infection, such as membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, cutaneous vasculitis, lichen planus, and porphyria cutanea tarda.14

The association of HCV infection with systemic autoimmune disease (SAD) has been described in a number of instances; cryoglobulinemia has most commonly been linked to HCV.15 Although the association between HCV and other SADs is less clear, there is growing interest in a possible relationship between them. To that end, physicians of the HISPAMEC (Hispanoamerican Study Group of Autoimmune Manifestations Associated With Hepatitis C Virus) study group described the clinical and immunologic characteristics of 1020 patients with SAD and associated chronic HCV infection. The 3 most frequent SADs (>90% of cases) were Sjögren syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus.16 However, the strength of association differs for each SAD based on existing descriptions.16,17 Less commonly, there may be a causal relationship between HCV infection and SSc. It should be noted that most of these data are based on small series and case reports.6,16-19

The role of HCV in the pathogenesis of systemic scleroderma and other autoimmune diseases is unknown. It is also possible that the replication of HCV outside the liver, particularly in mononuclear cells, may suppress immune tolerance in genetically predisposed individuals.20

Conclusion

Nodular scleroderma associated with HCV infection is a rare entity. At present, it cannot be determined whether there is an etiopathologic association between HCV infection and SSc or whether the simultaneous diagnosis may be coincidental. Routine determination of HCV serology in scleroderma patients may help to clarify this issue.

1. Krell JM, Solomon AR, Glavey CM, et al. Nodular scleroderma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:343-345.

2. Cannick L 3rd, Douglas G, Crater S, et al. Nodular scleroderma: case report and literature review. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:2500-2502.

3. Rencic A, Brinster NK, Nousari CH. Keloid morphea and nodular scleroderma: two distinct clinical variants of scleroderma? J Cutan Med Surg. 2003;7:20-24.

4. Wriston CC, Rubin AI, Elenitsas R, et al. Nodular scleroderma: a report of 2 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:385-388.

5. Barzilai A, Lyakhovitsky A, Horowitz A, et al. Keloid-like scleroderma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:327-330.

6. Melani L, Caproni M, Cardinali C, et al. A case of nodular scleroderma. J Dermatol. 2005;32:1028-1031.

7. Mizutani H, Taniguchi H, Sakakura T, et al. Nodular scleroderma: focally increased tenascin expression differing from that in the surrounding scleroderma skin. J Dermatol. 1995;22:267-271.

8. Yamamoto T, Sawada Y, Katayama I, et al. Nodular scleroderma: increased expression of connective tissue growth factor. Dermatology. 2005;211:218-223.

9. Yamamoto T, Furuse Y, Katayama I, et al. Nodular scleroderma in a worker using a silica-containing abrasive. J Dermatol. 1994;21:751-754.

10. Cantwell AR Jr, Rowe L, Kelso DW. Nodular scleroderma and pleomorphic acid-fast bacteria. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116:1283-1290.

11. Yamamoto T, Sakashita S, Sawada Y, et al. Possible role of epidermal growth factor in the lesional skin of nodular morphea. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:312-313.

12. Jain K, Dayal S, Jain VK, et al. Blaschko linear nodular morphea with dermal mucinosis. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:953-955.

13. Kauer F, Simon JC, Sticherling M. Nodular morphea. Dermatology. 2009;218:63-66.

14. Gumber SC, Chopra S. Hepatitis C: a multifaceted disease. review of extrahepatic manifestations. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:615-620.

15. Ferri C, Greco F, Longombardo G, et al. Antibodies to hepatitis C virus in patients with mixed cryoglobulinemia. Arthritis Rheum. 1991;34:1606-1610.

16. Ramos-Casals M, Munoz S, Medina F, et al. Systemic autoimmune diseases in patients with hepatitis C virus infection: characterization of 1020 cases (The HISPAMEC Registry). J Rheumatol. 2009;36:1442-1448.

17. Ramos-Casals M, Jara LJ, Medina F, et al. Systemic autoimmune diseases co-existing with chronic hepatitis C virus infection (the HISPAMEC Registry): patterns of clinical and immunological expression in 180 cases. J Intern Med. 2005;257:549-557.

18. Abu-Shakra M, Sukenik S, Buskila D. Systemic sclerosis: another rheumatic disease associated with hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Rheumatol. 2000;19:378-380.

19. Yamamoto M, Yamamoto T, Tsuboi R. Discoid lupus erythematosus in a patient with scleroderma and hepatitis C virus infection. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30:969-971.

20. Abu-Shakra M, Shoenfeld Y. Chronic infections and autoimmunity. Immunol Ser. 1992;55:285-313.

Case Report

A 63-year-old woman was referred to our clinic for evaluation of multiple papules and nodules on the neck and trunk that had been present for 2 years. Three years prior to presentation she had been diagnosed with systemic sclerosis (SSc) after developing progressive diffuse cutaneous sclerosis, Raynaud phenomenon with digital pitted scarring, esophageal dysmotility, myositis, pericardial effusion, and interstitial lung disease. Serologic test results were positive for anti-Scl-70 antibodies. Antinuclear antibody test results were negative for anti–double-stranded DNA, anti-nRNP, anti-Ro/La, anti-Sm, and anti-Jo-1 antibodies. The patient was treated with prednisolone 7.5 mg daily, nifedipine 15 mg daily, valsartan 80 mg daily, manidipine 20 mg daily, omeprazole 20 mg daily, and beraprost 80 mg daily. One year later, numerous asymptomatic flesh-colored papules and nodules developed on the neck, chest, abdomen, and back. There was no history of trauma or surgery at any of the affected sites.

On further investigation, anti–hepatitis C virus (HCV) antibodies were identified and confirmed by HCV ribonucleic acid polymerase chain reaction at the same time that the diagnosis of SSc was established. Hepatitis C virus genotype 3a was noted, and the patient’s viral load was 378,000 IU/mL. Therefore, a diagnosis of chronic HCV infection was established. The patient was initially unable to receive medical treatment due to lack of finances. A year and a half following the diagnosis of HCV infection, with worsening liver function tests and increasing viral load (1,369,113 IU/mL), the patient began therapy with peginterferon alfa-2b 80 mg weekly and ribavirin 800 mg daily. However, the medications were discontinued after 2 months when she developed severe hemolytic anemia related to ribavirin.

On physical examination, the patient was noted to have a masklike facies with a pinched nose and constricted opening of the mouth. Her skin was tightened and stiff extending from the fingers to the proximal extremities. Numerous well-circumscribed, flesh-colored, firm papules and nodules ranging from 2 to 20 mm in diameter were present on the neck (Figure 1), chest, abdomen (Figure 2), and back.

|

|

Two 4-mm punch biopsy samples obtained from a papule on the neck and a nodule on the abdomen revealed homogenized collagen bundles with scattered plump fibroblasts in the lower reticular dermis. Clinicopathologic correlation of the biopsy findings with the cutaneous examination resulted in a diagnosis of nodular scleroderma (Figures 3 and 4).

|

The patient began treatment with intralesional injections of triamcinolone 5 to 10 mg/mL for nodules as well as an ultrapotent corticosteroid cream, clobetasol propionate 0.05%, for small papules. Injections were performed at 4- to 8-week intervals and resulted in modest clinical improvement.

Comment

Scleroderma may be present only in the skin (morphea) or as a systemic disease (systemic scleroderma). Rarely, cutaneous involvement can exhibit a nodular or hypertrophic morphology, which has been described in the literature as nodular or keloidal scleroderma in a patient with known SSc1-10 and as nodular or keloidal morphea in localized cutaneous scleroderma.3,11-13

Histopathology

The distinction between the terms nodular scleroderma and keloidal scleroderma is not clear, and they are not necessarily interchangeable. To provide clarity, we find it useful to delineate specific histologic findings associated with the diagnoses of keloid, scleroderma, and the uncommon keloid/scleroderma overlap. The histopathologic findings of keloids include a fibrotic dermis and broad dispersed bundles of eosinophilic hyalinized collagen. The histopathologic findings of scleroderma include broad sclerotic bands of collagen throughout the dermis with loss of perieccrine fat. In the overlapping keloid/scleroderma condition, which is a variant of scleroderma, hyalinized collagen fibers and keloidal collagen appear in the same specimen.3,4

To distinguish these conditions, Barzilai et al5 proposed that only cases showing both clinical and histologic characteristics of a keloid should be referred to as keloidal morphea/scleroderma. They further stated that the terms nodular morphea or nodular scleroderma ought to be used only for cases that are indistinguishable histologically from scleroderma. The term morphea is appropriate when only a limited amount of skin disease is present, while scleroderma implies association with systemic disease.5 Likely, there is a histologic continuum in this variant of scleroderma, in which nodular morphea/scleroderma exists at one end and keloidal morphea/scleroderma exists at the other end.5,13

In the case of our patient, papulonodular lesions developed 1 year after the diagnosis of SSc was made, and the histopathologic examination revealed classic findings of scleroderma. As a result, our patient is most appropriately classified as having nodular scleroderma.

Clinical Features

Nodular scleroderma mostly affects young and middle-aged women and is clinically characterized by solitary or multiple firm, long-lasting papules or nodules on the upper trunk and chest, neck, and proximal extremities.1-4,6

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The triggers and cellular mechanisms of nodular scleroderma are unclear. Some authors have implicated matricellular protein and growth factors such as tenascin, connective tissue growth factor, and epidermal growth factor in nodule formation.7,8,11 Yamamoto et al9 cited chemical exposure to a silica-containing abrasive as the cause of nodular scleroderma in a worker.

Possible HCV Association

Some reports have indicated an association between nodular scleroderma and pathogens such as acid-fast bacteria10 and HCV.6 Of note, many extrahepatic conditions have been associated with HCV infection, such as membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, cutaneous vasculitis, lichen planus, and porphyria cutanea tarda.14

The association of HCV infection with systemic autoimmune disease (SAD) has been described in a number of instances; cryoglobulinemia has most commonly been linked to HCV.15 Although the association between HCV and other SADs is less clear, there is growing interest in a possible relationship between them. To that end, physicians of the HISPAMEC (Hispanoamerican Study Group of Autoimmune Manifestations Associated With Hepatitis C Virus) study group described the clinical and immunologic characteristics of 1020 patients with SAD and associated chronic HCV infection. The 3 most frequent SADs (>90% of cases) were Sjögren syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus.16 However, the strength of association differs for each SAD based on existing descriptions.16,17 Less commonly, there may be a causal relationship between HCV infection and SSc. It should be noted that most of these data are based on small series and case reports.6,16-19

The role of HCV in the pathogenesis of systemic scleroderma and other autoimmune diseases is unknown. It is also possible that the replication of HCV outside the liver, particularly in mononuclear cells, may suppress immune tolerance in genetically predisposed individuals.20

Conclusion

Nodular scleroderma associated with HCV infection is a rare entity. At present, it cannot be determined whether there is an etiopathologic association between HCV infection and SSc or whether the simultaneous diagnosis may be coincidental. Routine determination of HCV serology in scleroderma patients may help to clarify this issue.

Case Report

A 63-year-old woman was referred to our clinic for evaluation of multiple papules and nodules on the neck and trunk that had been present for 2 years. Three years prior to presentation she had been diagnosed with systemic sclerosis (SSc) after developing progressive diffuse cutaneous sclerosis, Raynaud phenomenon with digital pitted scarring, esophageal dysmotility, myositis, pericardial effusion, and interstitial lung disease. Serologic test results were positive for anti-Scl-70 antibodies. Antinuclear antibody test results were negative for anti–double-stranded DNA, anti-nRNP, anti-Ro/La, anti-Sm, and anti-Jo-1 antibodies. The patient was treated with prednisolone 7.5 mg daily, nifedipine 15 mg daily, valsartan 80 mg daily, manidipine 20 mg daily, omeprazole 20 mg daily, and beraprost 80 mg daily. One year later, numerous asymptomatic flesh-colored papules and nodules developed on the neck, chest, abdomen, and back. There was no history of trauma or surgery at any of the affected sites.

On further investigation, anti–hepatitis C virus (HCV) antibodies were identified and confirmed by HCV ribonucleic acid polymerase chain reaction at the same time that the diagnosis of SSc was established. Hepatitis C virus genotype 3a was noted, and the patient’s viral load was 378,000 IU/mL. Therefore, a diagnosis of chronic HCV infection was established. The patient was initially unable to receive medical treatment due to lack of finances. A year and a half following the diagnosis of HCV infection, with worsening liver function tests and increasing viral load (1,369,113 IU/mL), the patient began therapy with peginterferon alfa-2b 80 mg weekly and ribavirin 800 mg daily. However, the medications were discontinued after 2 months when she developed severe hemolytic anemia related to ribavirin.

On physical examination, the patient was noted to have a masklike facies with a pinched nose and constricted opening of the mouth. Her skin was tightened and stiff extending from the fingers to the proximal extremities. Numerous well-circumscribed, flesh-colored, firm papules and nodules ranging from 2 to 20 mm in diameter were present on the neck (Figure 1), chest, abdomen (Figure 2), and back.

|

|

Two 4-mm punch biopsy samples obtained from a papule on the neck and a nodule on the abdomen revealed homogenized collagen bundles with scattered plump fibroblasts in the lower reticular dermis. Clinicopathologic correlation of the biopsy findings with the cutaneous examination resulted in a diagnosis of nodular scleroderma (Figures 3 and 4).

|

The patient began treatment with intralesional injections of triamcinolone 5 to 10 mg/mL for nodules as well as an ultrapotent corticosteroid cream, clobetasol propionate 0.05%, for small papules. Injections were performed at 4- to 8-week intervals and resulted in modest clinical improvement.

Comment

Scleroderma may be present only in the skin (morphea) or as a systemic disease (systemic scleroderma). Rarely, cutaneous involvement can exhibit a nodular or hypertrophic morphology, which has been described in the literature as nodular or keloidal scleroderma in a patient with known SSc1-10 and as nodular or keloidal morphea in localized cutaneous scleroderma.3,11-13

Histopathology

The distinction between the terms nodular scleroderma and keloidal scleroderma is not clear, and they are not necessarily interchangeable. To provide clarity, we find it useful to delineate specific histologic findings associated with the diagnoses of keloid, scleroderma, and the uncommon keloid/scleroderma overlap. The histopathologic findings of keloids include a fibrotic dermis and broad dispersed bundles of eosinophilic hyalinized collagen. The histopathologic findings of scleroderma include broad sclerotic bands of collagen throughout the dermis with loss of perieccrine fat. In the overlapping keloid/scleroderma condition, which is a variant of scleroderma, hyalinized collagen fibers and keloidal collagen appear in the same specimen.3,4

To distinguish these conditions, Barzilai et al5 proposed that only cases showing both clinical and histologic characteristics of a keloid should be referred to as keloidal morphea/scleroderma. They further stated that the terms nodular morphea or nodular scleroderma ought to be used only for cases that are indistinguishable histologically from scleroderma. The term morphea is appropriate when only a limited amount of skin disease is present, while scleroderma implies association with systemic disease.5 Likely, there is a histologic continuum in this variant of scleroderma, in which nodular morphea/scleroderma exists at one end and keloidal morphea/scleroderma exists at the other end.5,13

In the case of our patient, papulonodular lesions developed 1 year after the diagnosis of SSc was made, and the histopathologic examination revealed classic findings of scleroderma. As a result, our patient is most appropriately classified as having nodular scleroderma.

Clinical Features

Nodular scleroderma mostly affects young and middle-aged women and is clinically characterized by solitary or multiple firm, long-lasting papules or nodules on the upper trunk and chest, neck, and proximal extremities.1-4,6

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The triggers and cellular mechanisms of nodular scleroderma are unclear. Some authors have implicated matricellular protein and growth factors such as tenascin, connective tissue growth factor, and epidermal growth factor in nodule formation.7,8,11 Yamamoto et al9 cited chemical exposure to a silica-containing abrasive as the cause of nodular scleroderma in a worker.

Possible HCV Association

Some reports have indicated an association between nodular scleroderma and pathogens such as acid-fast bacteria10 and HCV.6 Of note, many extrahepatic conditions have been associated with HCV infection, such as membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, cutaneous vasculitis, lichen planus, and porphyria cutanea tarda.14

The association of HCV infection with systemic autoimmune disease (SAD) has been described in a number of instances; cryoglobulinemia has most commonly been linked to HCV.15 Although the association between HCV and other SADs is less clear, there is growing interest in a possible relationship between them. To that end, physicians of the HISPAMEC (Hispanoamerican Study Group of Autoimmune Manifestations Associated With Hepatitis C Virus) study group described the clinical and immunologic characteristics of 1020 patients with SAD and associated chronic HCV infection. The 3 most frequent SADs (>90% of cases) were Sjögren syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus.16 However, the strength of association differs for each SAD based on existing descriptions.16,17 Less commonly, there may be a causal relationship between HCV infection and SSc. It should be noted that most of these data are based on small series and case reports.6,16-19

The role of HCV in the pathogenesis of systemic scleroderma and other autoimmune diseases is unknown. It is also possible that the replication of HCV outside the liver, particularly in mononuclear cells, may suppress immune tolerance in genetically predisposed individuals.20

Conclusion

Nodular scleroderma associated with HCV infection is a rare entity. At present, it cannot be determined whether there is an etiopathologic association between HCV infection and SSc or whether the simultaneous diagnosis may be coincidental. Routine determination of HCV serology in scleroderma patients may help to clarify this issue.

1. Krell JM, Solomon AR, Glavey CM, et al. Nodular scleroderma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:343-345.

2. Cannick L 3rd, Douglas G, Crater S, et al. Nodular scleroderma: case report and literature review. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:2500-2502.

3. Rencic A, Brinster NK, Nousari CH. Keloid morphea and nodular scleroderma: two distinct clinical variants of scleroderma? J Cutan Med Surg. 2003;7:20-24.

4. Wriston CC, Rubin AI, Elenitsas R, et al. Nodular scleroderma: a report of 2 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:385-388.

5. Barzilai A, Lyakhovitsky A, Horowitz A, et al. Keloid-like scleroderma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:327-330.

6. Melani L, Caproni M, Cardinali C, et al. A case of nodular scleroderma. J Dermatol. 2005;32:1028-1031.

7. Mizutani H, Taniguchi H, Sakakura T, et al. Nodular scleroderma: focally increased tenascin expression differing from that in the surrounding scleroderma skin. J Dermatol. 1995;22:267-271.

8. Yamamoto T, Sawada Y, Katayama I, et al. Nodular scleroderma: increased expression of connective tissue growth factor. Dermatology. 2005;211:218-223.

9. Yamamoto T, Furuse Y, Katayama I, et al. Nodular scleroderma in a worker using a silica-containing abrasive. J Dermatol. 1994;21:751-754.

10. Cantwell AR Jr, Rowe L, Kelso DW. Nodular scleroderma and pleomorphic acid-fast bacteria. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116:1283-1290.

11. Yamamoto T, Sakashita S, Sawada Y, et al. Possible role of epidermal growth factor in the lesional skin of nodular morphea. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:312-313.

12. Jain K, Dayal S, Jain VK, et al. Blaschko linear nodular morphea with dermal mucinosis. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:953-955.

13. Kauer F, Simon JC, Sticherling M. Nodular morphea. Dermatology. 2009;218:63-66.

14. Gumber SC, Chopra S. Hepatitis C: a multifaceted disease. review of extrahepatic manifestations. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:615-620.

15. Ferri C, Greco F, Longombardo G, et al. Antibodies to hepatitis C virus in patients with mixed cryoglobulinemia. Arthritis Rheum. 1991;34:1606-1610.

16. Ramos-Casals M, Munoz S, Medina F, et al. Systemic autoimmune diseases in patients with hepatitis C virus infection: characterization of 1020 cases (The HISPAMEC Registry). J Rheumatol. 2009;36:1442-1448.

17. Ramos-Casals M, Jara LJ, Medina F, et al. Systemic autoimmune diseases co-existing with chronic hepatitis C virus infection (the HISPAMEC Registry): patterns of clinical and immunological expression in 180 cases. J Intern Med. 2005;257:549-557.

18. Abu-Shakra M, Sukenik S, Buskila D. Systemic sclerosis: another rheumatic disease associated with hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Rheumatol. 2000;19:378-380.

19. Yamamoto M, Yamamoto T, Tsuboi R. Discoid lupus erythematosus in a patient with scleroderma and hepatitis C virus infection. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30:969-971.

20. Abu-Shakra M, Shoenfeld Y. Chronic infections and autoimmunity. Immunol Ser. 1992;55:285-313.

1. Krell JM, Solomon AR, Glavey CM, et al. Nodular scleroderma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:343-345.

2. Cannick L 3rd, Douglas G, Crater S, et al. Nodular scleroderma: case report and literature review. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:2500-2502.

3. Rencic A, Brinster NK, Nousari CH. Keloid morphea and nodular scleroderma: two distinct clinical variants of scleroderma? J Cutan Med Surg. 2003;7:20-24.

4. Wriston CC, Rubin AI, Elenitsas R, et al. Nodular scleroderma: a report of 2 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:385-388.

5. Barzilai A, Lyakhovitsky A, Horowitz A, et al. Keloid-like scleroderma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:327-330.

6. Melani L, Caproni M, Cardinali C, et al. A case of nodular scleroderma. J Dermatol. 2005;32:1028-1031.

7. Mizutani H, Taniguchi H, Sakakura T, et al. Nodular scleroderma: focally increased tenascin expression differing from that in the surrounding scleroderma skin. J Dermatol. 1995;22:267-271.

8. Yamamoto T, Sawada Y, Katayama I, et al. Nodular scleroderma: increased expression of connective tissue growth factor. Dermatology. 2005;211:218-223.

9. Yamamoto T, Furuse Y, Katayama I, et al. Nodular scleroderma in a worker using a silica-containing abrasive. J Dermatol. 1994;21:751-754.

10. Cantwell AR Jr, Rowe L, Kelso DW. Nodular scleroderma and pleomorphic acid-fast bacteria. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116:1283-1290.

11. Yamamoto T, Sakashita S, Sawada Y, et al. Possible role of epidermal growth factor in the lesional skin of nodular morphea. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:312-313.

12. Jain K, Dayal S, Jain VK, et al. Blaschko linear nodular morphea with dermal mucinosis. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:953-955.

13. Kauer F, Simon JC, Sticherling M. Nodular morphea. Dermatology. 2009;218:63-66.

14. Gumber SC, Chopra S. Hepatitis C: a multifaceted disease. review of extrahepatic manifestations. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:615-620.

15. Ferri C, Greco F, Longombardo G, et al. Antibodies to hepatitis C virus in patients with mixed cryoglobulinemia. Arthritis Rheum. 1991;34:1606-1610.

16. Ramos-Casals M, Munoz S, Medina F, et al. Systemic autoimmune diseases in patients with hepatitis C virus infection: characterization of 1020 cases (The HISPAMEC Registry). J Rheumatol. 2009;36:1442-1448.

17. Ramos-Casals M, Jara LJ, Medina F, et al. Systemic autoimmune diseases co-existing with chronic hepatitis C virus infection (the HISPAMEC Registry): patterns of clinical and immunological expression in 180 cases. J Intern Med. 2005;257:549-557.

18. Abu-Shakra M, Sukenik S, Buskila D. Systemic sclerosis: another rheumatic disease associated with hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Rheumatol. 2000;19:378-380.

19. Yamamoto M, Yamamoto T, Tsuboi R. Discoid lupus erythematosus in a patient with scleroderma and hepatitis C virus infection. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30:969-971.

20. Abu-Shakra M, Shoenfeld Y. Chronic infections and autoimmunity. Immunol Ser. 1992;55:285-313.

Practice Points

- Nodular scleroderma is a rare form of cutaneous scleroderma that can occur in association with systemic scleroderma or localized morphea.

- The clinical features are characterized by solitary or multiple, firm, long-lasting papules or nodules on the neck, upper trunk, and proximal extremities.

- The pathogenesis is still unclear. Some reports have suggested that matricellular protein and growth factor, acid-fast bacteria, organic solvents, or the hepatitis C virus may be involved.

Rare Angioinvasive Fungal Infection in Association With Leukemia Cutis

Leukemia cutis (LC) is characterized by the infiltration of malignant neoplastic leukocytes or their precursors into the skin, most often in conjunction with systemic leukemia.1 Acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) is the second most common cause of LC and the most common form of leukemia among adults.1 Patients with leukemia often are in a relative or absolute immunocompromised state, which may be secondary to neutropenia, chemotherapy regimens, or immunosuppressive regimens following stem cell transplant (SCT). Thus, when evaluating cutaneous lesions consistent with LC in immunocompromised patients, there must be a high index of suspicion for concomitant opportunistic infections.

We report the case of a 52-year-old man with primary refractory AML following allogeneic SCT with relapse who presented with an LC lesion below the knee with concomitant invasive fungal infection despite being on prophylactic oral antifungal therapy.

Case Report

A 52-year-old man with primary refractory AML (M1) of 1 year’s duration presented for evaluation of a slowly progressing reddish purple nodule on the right knee of 2 to 4 months’ duration. The patient had undergone a matched unrelated donor allogeneic SCT 6 months following diagnosis of AML with subsequent disease progression despite reduction of posttransplant graft-versus-host disease prophylactic immune suppression and a cycle of clofarabine. The patient was hospitalized 2 months after the SCT for neutropenic fever and was found to have vancomycin-resistant enterococcal bacteremia, Clostridium difficile colitis, and possible fungal pneumonia. He was treated with voriconazole 200 mg twice daily, which he continued following discharge for antifungal prophylaxis. At the time of discharge, the patient reported that he noticed an asymptomatic “purple papule” on the right knee but did not seek further workup.

Two months later, the patient presented with a fever (temperature, 38.6°C) and leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 130 cells/mL [increased from 53 cells/mL 1 week prior to admission]). Due to his history of immunosuppression and neutropenia, the patient was placed on a broad-spectrum antibiotic regimen of cefepime, daptomycin, and linezolid on admission. Later, vancomycin and gentamicin were added and voriconazole was switched to caspofungin. The patient also received granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor for neutropenia. During the current hospitalization, blood cultures demonstrated vancomycin-resistant enterococcemia, and computed tomography of the chest revealed findings consistent with multilobar pneumonia.

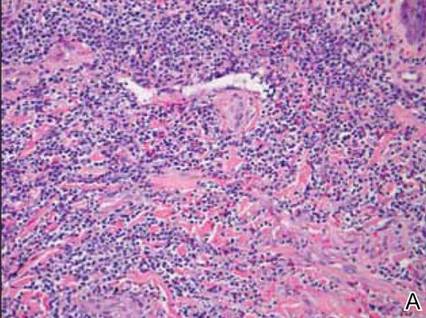

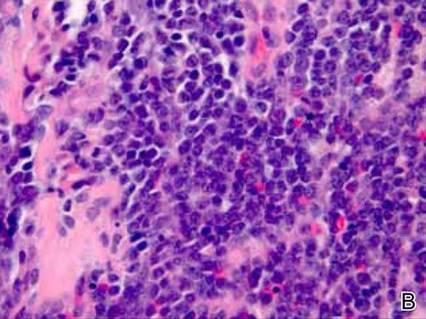

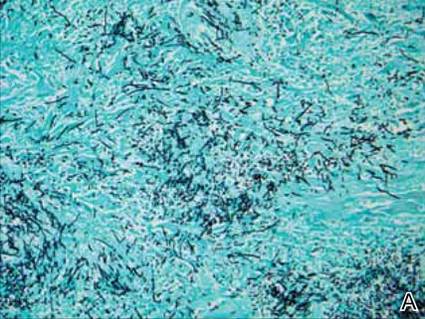

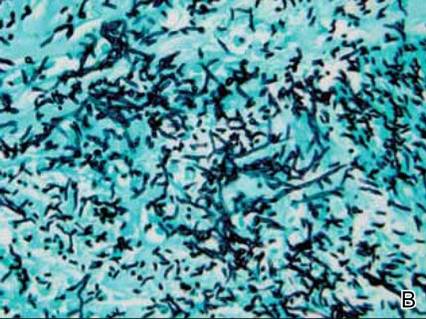

Dermatology was consulted to evaluate the purple nodule on the right knee, which had slowly progressed since his last admission. Physical examination revealed a violaceous, 1.5×1.5-cm nodule with central necrosis covered by black eschar with surrounding erythema (Figure 1). Biopsy specimens for routine histology and a tissue culture were obtained. Histopathologic examination revealed a dense diffuse infiltrate of large hyperchromatic mononuclear cells extending through the dermis, which was consistent with the patient’s known AML (Figure 2). Acid-fast bacillus staining was negative for mycobacterial organisms. Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain demonstrated an overwhelming number of septate fungal hyphae with acute-angle branching, concerning for Aspergillus species (Figure 3). Of note, an Aspergillus serum antigen test was performed at this time and was negative. On repeat review of the routine histologic sections, angioinvasion by hyphae was detected amidst the dense lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 4).

Given the patient’s immunocompromised state, the presence of angioinvasive fungi on the skin biopsy, and unresolved pneumonia, the patient was restarted on voriconazole for treatment of likely Aspergillus infection. He was continued on chemotherapy for the primary refractory AML and received a donor lymphocyte infusion prior to discharge. After the patient was discharged, the tissue culture grew Paecilomyces, a rare fungal species. The patient died 1 week after discharge.

|

|

Comment

Leukemia cutis is an extramedullary manifestation of leukemia that appears in 10% to 15% of patients with AML.2 The frequency of LC differs widely for the various types of AML, with the majority of cases occurring in the acute myelomonocytic leukemia (M4) or acute monocytic leukemia (M5) subtypes.3,4 One large study of AML patients (N=381) demonstrated an incidence of LC in 28.6% of patients with the M4 subtype and 42.9% of those with the M5 subtype, with an incidence of only 7.1% of patients with the M1 subtype.3 It occurs less frequently in chronic myeloproliferative diseases.2,4

Leukemia cutis has a wide range of cutaneous manifestations and may present with solitary or multiple papular, nodular, or plaquelike lesions that are red-brown, blue, violaceous, or hemorrhagic.4 Leukemia cutis occurs most commonly on the legs, followed by the arms, back, chest, scalp, and face.2,4 Leukemia cutis may be hard to distinguish clinically from other conditions such as cutaneous metastases of visceral malignancies, lymphoma, drug eruptions, and opportunistic infections. Leukemia cutis ulcers often measure only a few centimeters in diameter with a firmly adherent purulent or hemorrhagic crust and may occur in unusual locations. These lesions usually are treatment resistant and their persistence may help to lead to diagnosis.4

Microscopically, most LC lesions show a perivascular or periadnexal pattern of involvement or a dense diffuse, interstitial, or nodular atypical lymphocytic infiltrate involving the dermis and subcutis with sparing of the upper papillary dermis.2 The cytologic appearance of M1 and M2 subtypes of AML are characterized by medium-sized to large mononuclear cells with a light cytoplasm and large basophilic cell nuclei. The M4 and M5 subtypes of AML generally are dominated by medium-sized, round or oval-shaped mononuclear cells that may have eosinophilic cytoplasm and segmented or kidney-shaped basophilic nuclei.4 Immunophenotyping is crucial for diagnosis. In myeloid disorders, there is positive staining with markers of myeloid lineage such as myeloperoxidase, lysozyme, CD34, CD15, CD68, CD43, and CD117.5

In our patient, there was an ulcerated dense diffuse dermal infiltrate of large atypical lymphocytes consistent with LC and positive immunostaining consistent with LC associated with AML. Additionally, septate hyphae with acute-angle branching also were noted in the dermal blood vessels on hematoxylin and eosin and fungal staining, demonstrating concomitant fungal infection. Angioinvasion of organisms demonstrated on skin biopsy and persistent pneumonia noted on chest imaging suggested a disseminated infectious process.

Invasive fungal infections are an increasing cause of morbidity and mortality in immunocompromised individuals, including those with hematologic malignancies and hematologic SCTs. Despite an increasing number of antifungal therapies, outcomes are frequently suboptimal with mortality rates often greater than 50% depending on the pathogen and disease.6 Thus, there must be a high index of suspicion of infection even when a separate histopathologic diagnosis is available, such as the finding of leukemic infiltrates in this patient’s biopsy specimen. A similar case of LC has been reported with concomitant fungal infection involving Fusarium and Enterococcus.7 Patients with leukemic cells may develop leukemic infiltrates in response to cutaneous infection, and a high index of suspicion for 2 related but distinct processes is necessary.

Paecilomyces species are an emerging cause of opportunistic and usually severe human infections.8-11 The Paecilomyces species are saprophytic filamentous fungi that are found worldwide in soil as well as contaminants in the air and water.12Paecilomyces infection is generally associated with the use of immunosuppressive therapies, implants, or ocular surgery. Among species in this genus, Paecilomyces lilacinus and Paecilomyces variotii are of clinical importance. Most species have high susceptibility to the newer azoles such as voriconazole.6

Conclusion

Despite continued treatment with voriconazole, our patient still developed a rare fungal infection arising in a lesion of LC. He had signs of infection, including an elevated white blood cell count, fever, and malaise, which are nonspecific clinical findings that could have been attributed to known relapse of systemic leukemia or to known enterococcemia. Even in patients on antifungal prophylaxis and with other possible causes of leukocytosis, this case illustrates that there must be a high index of suspicion for angioinvasive fungal infection.

1. Aquilera SB, Zarraga M, Rosen L. Leukemia cutis in a patient with acute myelogenous leukemia: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2010;85:31-36.

2. Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros J, Prieto VG, et al. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:130.

3. Agis H, Weltermann A, Fonatsch C, et al. A comparative study on demographic, hematological, and cytogenetic findings and prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia with and without leukemia cutis. Ann Hematol. 2002;81:90-95.

4. Wagner G, Fenchel K, Back W, et al. Leukemia cutis—epidemiology, clinical presentation, and differential diagnoses. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012;10:27-36.

5. Hejmadi RK, Thompson D, Shah F, et al. Cutaneous presentation of aleukemic monoblastic leukemia cutis: a case report and review of literature with focus on immunohistochemistry. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(suppl 1):46.

6. Kontoyiannis DP. Invasive mycoses: strategies for effective management. Am J Med. 2012;125(suppl 1):25-38.

7. Feramisco JD, Hsiao JL, Fox LP, et al. Angioinvasive Fusarium and concomitant Enterococcus infection arising in association with leukemia cutis. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:926-929.

8. Antachopoulos C, Walsh TJ, Roilides E. Fungal infections in primary immunodeficiencies. Eur J Pediatr. 2007;166:1099-1117.

9. Carey J, D’Amico R, Sutton DA, et al. Paecilomyces lilacinus vaginitis in an immuno-competent patient. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:1155-1158.

10. Castro LG, Salebian A, Sotto MN. Hyalohyphomycosis by Paecilomyces lilacinus in a renal transplant patient and a review of human Paecilomyces species infections. J Med Vet Mycol. 1990;28:15-26.

11. Pastor FJ, Guarro J. Clinical manifestations, treatment and outcome of Paecilomyces lilacinus infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12:948-960.

12. Castelli MV, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Cuesta I, et al. Susceptibility testing and molecular classification of Paecilomyces spp. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:2926-2928.

Leukemia cutis (LC) is characterized by the infiltration of malignant neoplastic leukocytes or their precursors into the skin, most often in conjunction with systemic leukemia.1 Acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) is the second most common cause of LC and the most common form of leukemia among adults.1 Patients with leukemia often are in a relative or absolute immunocompromised state, which may be secondary to neutropenia, chemotherapy regimens, or immunosuppressive regimens following stem cell transplant (SCT). Thus, when evaluating cutaneous lesions consistent with LC in immunocompromised patients, there must be a high index of suspicion for concomitant opportunistic infections.

We report the case of a 52-year-old man with primary refractory AML following allogeneic SCT with relapse who presented with an LC lesion below the knee with concomitant invasive fungal infection despite being on prophylactic oral antifungal therapy.

Case Report

A 52-year-old man with primary refractory AML (M1) of 1 year’s duration presented for evaluation of a slowly progressing reddish purple nodule on the right knee of 2 to 4 months’ duration. The patient had undergone a matched unrelated donor allogeneic SCT 6 months following diagnosis of AML with subsequent disease progression despite reduction of posttransplant graft-versus-host disease prophylactic immune suppression and a cycle of clofarabine. The patient was hospitalized 2 months after the SCT for neutropenic fever and was found to have vancomycin-resistant enterococcal bacteremia, Clostridium difficile colitis, and possible fungal pneumonia. He was treated with voriconazole 200 mg twice daily, which he continued following discharge for antifungal prophylaxis. At the time of discharge, the patient reported that he noticed an asymptomatic “purple papule” on the right knee but did not seek further workup.

Two months later, the patient presented with a fever (temperature, 38.6°C) and leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 130 cells/mL [increased from 53 cells/mL 1 week prior to admission]). Due to his history of immunosuppression and neutropenia, the patient was placed on a broad-spectrum antibiotic regimen of cefepime, daptomycin, and linezolid on admission. Later, vancomycin and gentamicin were added and voriconazole was switched to caspofungin. The patient also received granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor for neutropenia. During the current hospitalization, blood cultures demonstrated vancomycin-resistant enterococcemia, and computed tomography of the chest revealed findings consistent with multilobar pneumonia.

Dermatology was consulted to evaluate the purple nodule on the right knee, which had slowly progressed since his last admission. Physical examination revealed a violaceous, 1.5×1.5-cm nodule with central necrosis covered by black eschar with surrounding erythema (Figure 1). Biopsy specimens for routine histology and a tissue culture were obtained. Histopathologic examination revealed a dense diffuse infiltrate of large hyperchromatic mononuclear cells extending through the dermis, which was consistent with the patient’s known AML (Figure 2). Acid-fast bacillus staining was negative for mycobacterial organisms. Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain demonstrated an overwhelming number of septate fungal hyphae with acute-angle branching, concerning for Aspergillus species (Figure 3). Of note, an Aspergillus serum antigen test was performed at this time and was negative. On repeat review of the routine histologic sections, angioinvasion by hyphae was detected amidst the dense lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 4).

Given the patient’s immunocompromised state, the presence of angioinvasive fungi on the skin biopsy, and unresolved pneumonia, the patient was restarted on voriconazole for treatment of likely Aspergillus infection. He was continued on chemotherapy for the primary refractory AML and received a donor lymphocyte infusion prior to discharge. After the patient was discharged, the tissue culture grew Paecilomyces, a rare fungal species. The patient died 1 week after discharge.

|

|

Comment

Leukemia cutis is an extramedullary manifestation of leukemia that appears in 10% to 15% of patients with AML.2 The frequency of LC differs widely for the various types of AML, with the majority of cases occurring in the acute myelomonocytic leukemia (M4) or acute monocytic leukemia (M5) subtypes.3,4 One large study of AML patients (N=381) demonstrated an incidence of LC in 28.6% of patients with the M4 subtype and 42.9% of those with the M5 subtype, with an incidence of only 7.1% of patients with the M1 subtype.3 It occurs less frequently in chronic myeloproliferative diseases.2,4

Leukemia cutis has a wide range of cutaneous manifestations and may present with solitary or multiple papular, nodular, or plaquelike lesions that are red-brown, blue, violaceous, or hemorrhagic.4 Leukemia cutis occurs most commonly on the legs, followed by the arms, back, chest, scalp, and face.2,4 Leukemia cutis may be hard to distinguish clinically from other conditions such as cutaneous metastases of visceral malignancies, lymphoma, drug eruptions, and opportunistic infections. Leukemia cutis ulcers often measure only a few centimeters in diameter with a firmly adherent purulent or hemorrhagic crust and may occur in unusual locations. These lesions usually are treatment resistant and their persistence may help to lead to diagnosis.4

Microscopically, most LC lesions show a perivascular or periadnexal pattern of involvement or a dense diffuse, interstitial, or nodular atypical lymphocytic infiltrate involving the dermis and subcutis with sparing of the upper papillary dermis.2 The cytologic appearance of M1 and M2 subtypes of AML are characterized by medium-sized to large mononuclear cells with a light cytoplasm and large basophilic cell nuclei. The M4 and M5 subtypes of AML generally are dominated by medium-sized, round or oval-shaped mononuclear cells that may have eosinophilic cytoplasm and segmented or kidney-shaped basophilic nuclei.4 Immunophenotyping is crucial for diagnosis. In myeloid disorders, there is positive staining with markers of myeloid lineage such as myeloperoxidase, lysozyme, CD34, CD15, CD68, CD43, and CD117.5

In our patient, there was an ulcerated dense diffuse dermal infiltrate of large atypical lymphocytes consistent with LC and positive immunostaining consistent with LC associated with AML. Additionally, septate hyphae with acute-angle branching also were noted in the dermal blood vessels on hematoxylin and eosin and fungal staining, demonstrating concomitant fungal infection. Angioinvasion of organisms demonstrated on skin biopsy and persistent pneumonia noted on chest imaging suggested a disseminated infectious process.

Invasive fungal infections are an increasing cause of morbidity and mortality in immunocompromised individuals, including those with hematologic malignancies and hematologic SCTs. Despite an increasing number of antifungal therapies, outcomes are frequently suboptimal with mortality rates often greater than 50% depending on the pathogen and disease.6 Thus, there must be a high index of suspicion of infection even when a separate histopathologic diagnosis is available, such as the finding of leukemic infiltrates in this patient’s biopsy specimen. A similar case of LC has been reported with concomitant fungal infection involving Fusarium and Enterococcus.7 Patients with leukemic cells may develop leukemic infiltrates in response to cutaneous infection, and a high index of suspicion for 2 related but distinct processes is necessary.

Paecilomyces species are an emerging cause of opportunistic and usually severe human infections.8-11 The Paecilomyces species are saprophytic filamentous fungi that are found worldwide in soil as well as contaminants in the air and water.12Paecilomyces infection is generally associated with the use of immunosuppressive therapies, implants, or ocular surgery. Among species in this genus, Paecilomyces lilacinus and Paecilomyces variotii are of clinical importance. Most species have high susceptibility to the newer azoles such as voriconazole.6

Conclusion

Despite continued treatment with voriconazole, our patient still developed a rare fungal infection arising in a lesion of LC. He had signs of infection, including an elevated white blood cell count, fever, and malaise, which are nonspecific clinical findings that could have been attributed to known relapse of systemic leukemia or to known enterococcemia. Even in patients on antifungal prophylaxis and with other possible causes of leukocytosis, this case illustrates that there must be a high index of suspicion for angioinvasive fungal infection.

Leukemia cutis (LC) is characterized by the infiltration of malignant neoplastic leukocytes or their precursors into the skin, most often in conjunction with systemic leukemia.1 Acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) is the second most common cause of LC and the most common form of leukemia among adults.1 Patients with leukemia often are in a relative or absolute immunocompromised state, which may be secondary to neutropenia, chemotherapy regimens, or immunosuppressive regimens following stem cell transplant (SCT). Thus, when evaluating cutaneous lesions consistent with LC in immunocompromised patients, there must be a high index of suspicion for concomitant opportunistic infections.

We report the case of a 52-year-old man with primary refractory AML following allogeneic SCT with relapse who presented with an LC lesion below the knee with concomitant invasive fungal infection despite being on prophylactic oral antifungal therapy.

Case Report

A 52-year-old man with primary refractory AML (M1) of 1 year’s duration presented for evaluation of a slowly progressing reddish purple nodule on the right knee of 2 to 4 months’ duration. The patient had undergone a matched unrelated donor allogeneic SCT 6 months following diagnosis of AML with subsequent disease progression despite reduction of posttransplant graft-versus-host disease prophylactic immune suppression and a cycle of clofarabine. The patient was hospitalized 2 months after the SCT for neutropenic fever and was found to have vancomycin-resistant enterococcal bacteremia, Clostridium difficile colitis, and possible fungal pneumonia. He was treated with voriconazole 200 mg twice daily, which he continued following discharge for antifungal prophylaxis. At the time of discharge, the patient reported that he noticed an asymptomatic “purple papule” on the right knee but did not seek further workup.

Two months later, the patient presented with a fever (temperature, 38.6°C) and leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 130 cells/mL [increased from 53 cells/mL 1 week prior to admission]). Due to his history of immunosuppression and neutropenia, the patient was placed on a broad-spectrum antibiotic regimen of cefepime, daptomycin, and linezolid on admission. Later, vancomycin and gentamicin were added and voriconazole was switched to caspofungin. The patient also received granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor for neutropenia. During the current hospitalization, blood cultures demonstrated vancomycin-resistant enterococcemia, and computed tomography of the chest revealed findings consistent with multilobar pneumonia.

Dermatology was consulted to evaluate the purple nodule on the right knee, which had slowly progressed since his last admission. Physical examination revealed a violaceous, 1.5×1.5-cm nodule with central necrosis covered by black eschar with surrounding erythema (Figure 1). Biopsy specimens for routine histology and a tissue culture were obtained. Histopathologic examination revealed a dense diffuse infiltrate of large hyperchromatic mononuclear cells extending through the dermis, which was consistent with the patient’s known AML (Figure 2). Acid-fast bacillus staining was negative for mycobacterial organisms. Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain demonstrated an overwhelming number of septate fungal hyphae with acute-angle branching, concerning for Aspergillus species (Figure 3). Of note, an Aspergillus serum antigen test was performed at this time and was negative. On repeat review of the routine histologic sections, angioinvasion by hyphae was detected amidst the dense lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 4).

Given the patient’s immunocompromised state, the presence of angioinvasive fungi on the skin biopsy, and unresolved pneumonia, the patient was restarted on voriconazole for treatment of likely Aspergillus infection. He was continued on chemotherapy for the primary refractory AML and received a donor lymphocyte infusion prior to discharge. After the patient was discharged, the tissue culture grew Paecilomyces, a rare fungal species. The patient died 1 week after discharge.

|

|

Comment

Leukemia cutis is an extramedullary manifestation of leukemia that appears in 10% to 15% of patients with AML.2 The frequency of LC differs widely for the various types of AML, with the majority of cases occurring in the acute myelomonocytic leukemia (M4) or acute monocytic leukemia (M5) subtypes.3,4 One large study of AML patients (N=381) demonstrated an incidence of LC in 28.6% of patients with the M4 subtype and 42.9% of those with the M5 subtype, with an incidence of only 7.1% of patients with the M1 subtype.3 It occurs less frequently in chronic myeloproliferative diseases.2,4

Leukemia cutis has a wide range of cutaneous manifestations and may present with solitary or multiple papular, nodular, or plaquelike lesions that are red-brown, blue, violaceous, or hemorrhagic.4 Leukemia cutis occurs most commonly on the legs, followed by the arms, back, chest, scalp, and face.2,4 Leukemia cutis may be hard to distinguish clinically from other conditions such as cutaneous metastases of visceral malignancies, lymphoma, drug eruptions, and opportunistic infections. Leukemia cutis ulcers often measure only a few centimeters in diameter with a firmly adherent purulent or hemorrhagic crust and may occur in unusual locations. These lesions usually are treatment resistant and their persistence may help to lead to diagnosis.4

Microscopically, most LC lesions show a perivascular or periadnexal pattern of involvement or a dense diffuse, interstitial, or nodular atypical lymphocytic infiltrate involving the dermis and subcutis with sparing of the upper papillary dermis.2 The cytologic appearance of M1 and M2 subtypes of AML are characterized by medium-sized to large mononuclear cells with a light cytoplasm and large basophilic cell nuclei. The M4 and M5 subtypes of AML generally are dominated by medium-sized, round or oval-shaped mononuclear cells that may have eosinophilic cytoplasm and segmented or kidney-shaped basophilic nuclei.4 Immunophenotyping is crucial for diagnosis. In myeloid disorders, there is positive staining with markers of myeloid lineage such as myeloperoxidase, lysozyme, CD34, CD15, CD68, CD43, and CD117.5

In our patient, there was an ulcerated dense diffuse dermal infiltrate of large atypical lymphocytes consistent with LC and positive immunostaining consistent with LC associated with AML. Additionally, septate hyphae with acute-angle branching also were noted in the dermal blood vessels on hematoxylin and eosin and fungal staining, demonstrating concomitant fungal infection. Angioinvasion of organisms demonstrated on skin biopsy and persistent pneumonia noted on chest imaging suggested a disseminated infectious process.

Invasive fungal infections are an increasing cause of morbidity and mortality in immunocompromised individuals, including those with hematologic malignancies and hematologic SCTs. Despite an increasing number of antifungal therapies, outcomes are frequently suboptimal with mortality rates often greater than 50% depending on the pathogen and disease.6 Thus, there must be a high index of suspicion of infection even when a separate histopathologic diagnosis is available, such as the finding of leukemic infiltrates in this patient’s biopsy specimen. A similar case of LC has been reported with concomitant fungal infection involving Fusarium and Enterococcus.7 Patients with leukemic cells may develop leukemic infiltrates in response to cutaneous infection, and a high index of suspicion for 2 related but distinct processes is necessary.

Paecilomyces species are an emerging cause of opportunistic and usually severe human infections.8-11 The Paecilomyces species are saprophytic filamentous fungi that are found worldwide in soil as well as contaminants in the air and water.12Paecilomyces infection is generally associated with the use of immunosuppressive therapies, implants, or ocular surgery. Among species in this genus, Paecilomyces lilacinus and Paecilomyces variotii are of clinical importance. Most species have high susceptibility to the newer azoles such as voriconazole.6

Conclusion

Despite continued treatment with voriconazole, our patient still developed a rare fungal infection arising in a lesion of LC. He had signs of infection, including an elevated white blood cell count, fever, and malaise, which are nonspecific clinical findings that could have been attributed to known relapse of systemic leukemia or to known enterococcemia. Even in patients on antifungal prophylaxis and with other possible causes of leukocytosis, this case illustrates that there must be a high index of suspicion for angioinvasive fungal infection.

1. Aquilera SB, Zarraga M, Rosen L. Leukemia cutis in a patient with acute myelogenous leukemia: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2010;85:31-36.

2. Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros J, Prieto VG, et al. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:130.

3. Agis H, Weltermann A, Fonatsch C, et al. A comparative study on demographic, hematological, and cytogenetic findings and prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia with and without leukemia cutis. Ann Hematol. 2002;81:90-95.

4. Wagner G, Fenchel K, Back W, et al. Leukemia cutis—epidemiology, clinical presentation, and differential diagnoses. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012;10:27-36.

5. Hejmadi RK, Thompson D, Shah F, et al. Cutaneous presentation of aleukemic monoblastic leukemia cutis: a case report and review of literature with focus on immunohistochemistry. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(suppl 1):46.

6. Kontoyiannis DP. Invasive mycoses: strategies for effective management. Am J Med. 2012;125(suppl 1):25-38.

7. Feramisco JD, Hsiao JL, Fox LP, et al. Angioinvasive Fusarium and concomitant Enterococcus infection arising in association with leukemia cutis. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:926-929.

8. Antachopoulos C, Walsh TJ, Roilides E. Fungal infections in primary immunodeficiencies. Eur J Pediatr. 2007;166:1099-1117.

9. Carey J, D’Amico R, Sutton DA, et al. Paecilomyces lilacinus vaginitis in an immuno-competent patient. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:1155-1158.

10. Castro LG, Salebian A, Sotto MN. Hyalohyphomycosis by Paecilomyces lilacinus in a renal transplant patient and a review of human Paecilomyces species infections. J Med Vet Mycol. 1990;28:15-26.

11. Pastor FJ, Guarro J. Clinical manifestations, treatment and outcome of Paecilomyces lilacinus infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12:948-960.

12. Castelli MV, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Cuesta I, et al. Susceptibility testing and molecular classification of Paecilomyces spp. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:2926-2928.

1. Aquilera SB, Zarraga M, Rosen L. Leukemia cutis in a patient with acute myelogenous leukemia: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2010;85:31-36.

2. Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros J, Prieto VG, et al. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:130.

3. Agis H, Weltermann A, Fonatsch C, et al. A comparative study on demographic, hematological, and cytogenetic findings and prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia with and without leukemia cutis. Ann Hematol. 2002;81:90-95.

4. Wagner G, Fenchel K, Back W, et al. Leukemia cutis—epidemiology, clinical presentation, and differential diagnoses. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012;10:27-36.

5. Hejmadi RK, Thompson D, Shah F, et al. Cutaneous presentation of aleukemic monoblastic leukemia cutis: a case report and review of literature with focus on immunohistochemistry. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(suppl 1):46.

6. Kontoyiannis DP. Invasive mycoses: strategies for effective management. Am J Med. 2012;125(suppl 1):25-38.

7. Feramisco JD, Hsiao JL, Fox LP, et al. Angioinvasive Fusarium and concomitant Enterococcus infection arising in association with leukemia cutis. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:926-929.

8. Antachopoulos C, Walsh TJ, Roilides E. Fungal infections in primary immunodeficiencies. Eur J Pediatr. 2007;166:1099-1117.

9. Carey J, D’Amico R, Sutton DA, et al. Paecilomyces lilacinus vaginitis in an immuno-competent patient. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:1155-1158.

10. Castro LG, Salebian A, Sotto MN. Hyalohyphomycosis by Paecilomyces lilacinus in a renal transplant patient and a review of human Paecilomyces species infections. J Med Vet Mycol. 1990;28:15-26.

11. Pastor FJ, Guarro J. Clinical manifestations, treatment and outcome of Paecilomyces lilacinus infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12:948-960.

12. Castelli MV, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Cuesta I, et al. Susceptibility testing and molecular classification of Paecilomyces spp. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:2926-2928.

Practice Points

- Immunosuppressed patients are at risk for atypical presentations of common infections as well as infection with rare pathogens.

- Skin biopsy and tissue culture play an important role in identifying infectious agents in immunosuppressed patients.

- Leukemic infiltrates may mask pathogens, and pathologists should strongly consider additional stains when indicated.