User login

Cutaneous T-cell Lymphoma and Concomitant Atopic Dermatitis Responding to Dupilumab

Patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) often are diagnosed with atopic dermatitis (AD) or psoriasis before receiving their CTCL diagnosis. The effects of new biologic therapies for AD such as dupilumab, an IL-4/IL-13 antagonist, on CTCL are unknown. Dupilumab may be beneficial in CTCL given that helper T cell (TH2) cytokines are increased in advanced CTCL.1 We present a patient with definitive CTCL and concomitant AD who was safely treated with dupilumab and experienced improvement in both CTCL and AD.

Case Report

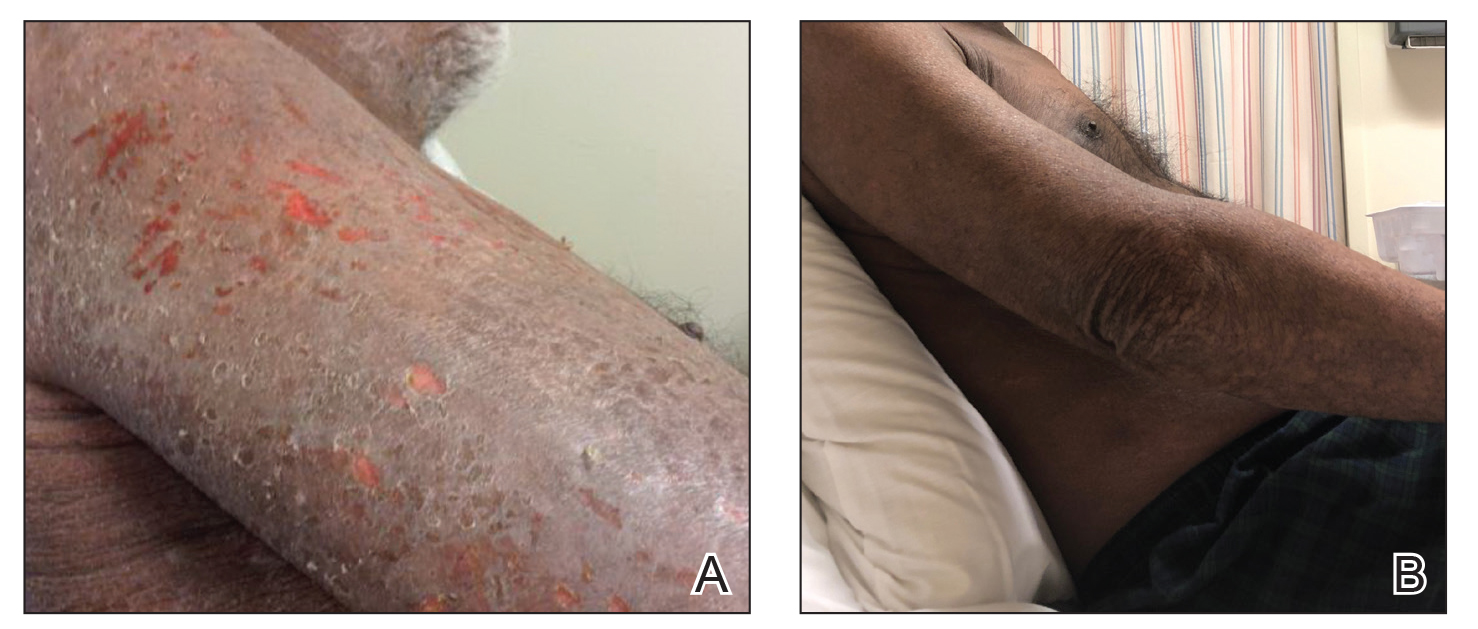

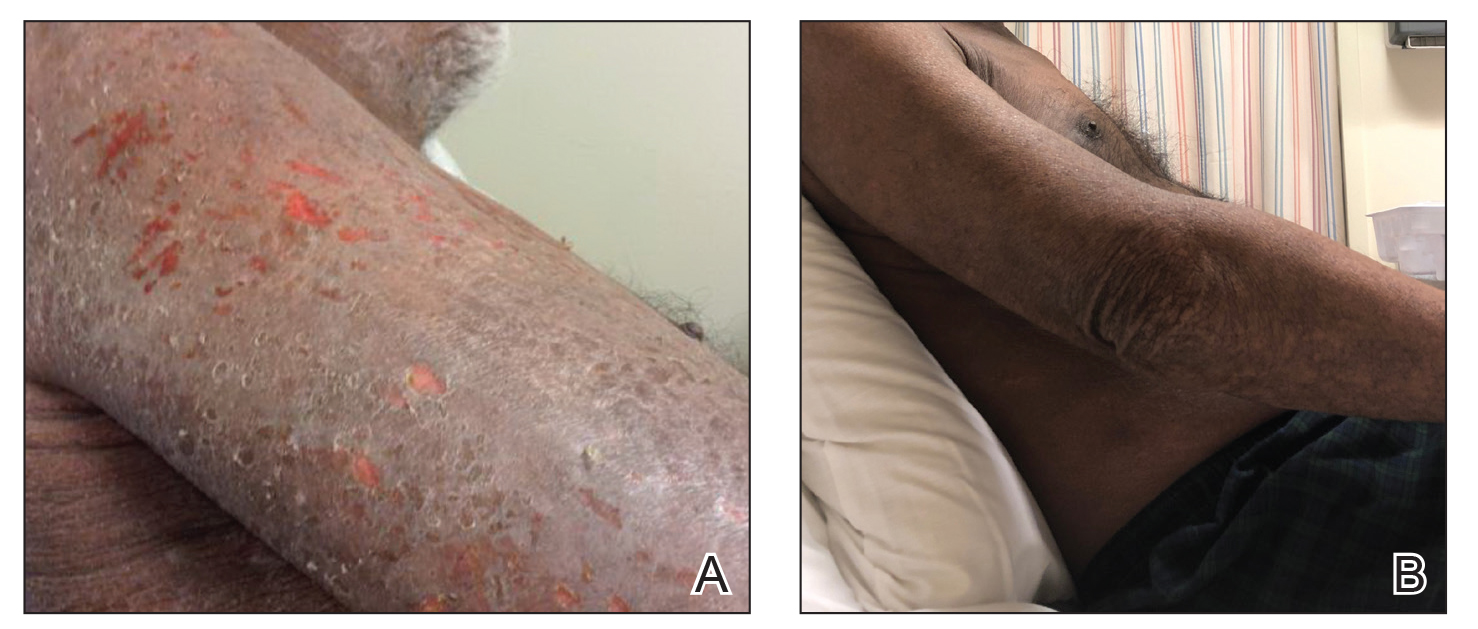

A 68-year-old man presented with increased itching from AD and a new rash on the arms, neck, chest, back, and lower extremities (Figures 1A and 2A). He had a medical history of AD and CTCL diagnosed by biopsy and peripheral blood flow cytometry (stage IVA1 [T4N0M0B2]) that was being treated with comprehensive multimodality therapy consisting of bexarotene 375 mg daily, interferon alfa-2b 3 mIU 3 times weekly, interferon gamma-1b 2 mIU 3 times weekly, total skin electron beam therapy followed by narrowband UVB twice weekly, and extracorporeal photopheresis every 4 weeks, which resulted in a partial clinical response for 6 months. A biopsy performed at the current presentation showed focal spongiosis and features of lichen simplex chronicus with no evidence suggestive of CTCL. Peripheral blood flow cytometry showed stable B1-staged disease burden (CD4/CD8, 2.6:1); CD4+/CD7−, 12% [91/µL]; CD4+/CD26−, 21% [155/µL]). Treatment with potent and superpotent topical steroids was attempted for more than 6 months and was unsuccessful in relieving the symptoms.

Given the recalcitrant nature of the patient’s rash and itching, dupilumab was added to his CTCL regimen. Prior to initiating dupilumab, the patient reported a numeric rating scale itch intensity of 7 out of 10. After 4 weeks of treatment with dupilumab, the patient reported a numeric rating scale itch intensity of 1. Over a 3-month period, the patient’s rash improved dramatically (Figures 1B and 2B), making it possible to decrease CTCL treatments—bexarotene decreased to 300 mg, interferon alfa-2b to 3 mIU twice weekly, interferon gamma-1b to 2 mIU twice weekly, extracorporeal photopheresis every 5 weeks, and narrowband UVB was discontinued completely. A comparison of the patient’s flow cytometry analysis from before treatment to 3 months after dupilumab showed an overall slight reduction in CTCL B1 blood involvement and normalization of the patient’s absolute eosinophil count and serum lactate dehydrogenase level. The patient tolerated the treatment well without any adverse events and has maintained clinical response for 6 months.

Comment

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas represent a heterogeneous group of T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders involving the skin.2 The definitive diagnosis of CTCL is challenging, as the clinical and pathologic features often are nonspecific in early disease. Frequently, undiagnosed patients are treated empirically with immunosuppressive agents. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and cyclosporine are both associated with progression or worsening of undiagnosed CTCL.3,4 Dupilumab was the first US Food and Drug Administration–approved biologic for the treatment of moderate to severe AD. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma has immunologic features, such as TH2 skewing, that overlap with AD; however, the effects of dupilumab in CTCL are not yet known.5,6 Our group has seen patients initially thought to have AD who received dupilumab without improvement and were subsequently diagnosed with CTCL, suggesting dupilumab did not affect CTCL tumor cells. Given these findings, there was concern that dupilumab might exacerbate undiagnosed CTCL. Our patient with definitive, severe, refractory CTCL noted marked improvement in both AD and underlying CTCL with the addition of dupilumab. No other treatments were added. The response was so dramatic that we were able to wean the doses and frequencies of several CTCL treatments. Our findings suggest that dupilumab may be beneficial in a certain subset of CTCL patients with a history of AD or known concomitant AD. Prospective studies are needed to fully investigate dupilumab safety and efficacy in CTCL and whether it has any primary effects on tumor burden in addition to benefit for itch and skin symptom relief.

- Guenova E, Watanabe R, Teague JE, et al. TH2 cytokines from malignant cells suppress TH1 responses and enforce a global TH2 bias in leukemic cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:3755-3763.

- Wilcox RA. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: 2016 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:151-165.

- Martinez-Escala ME, Posligua AL, Wickless H, et al. Progression of undiagnosed cutaneous lymphoma after anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1068-1076.

- Pielop JA, Jones D, Duvic M. Transient CD30+ nodal transformation of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma associated with cyclosporine treatment. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:505-511.

- Saulite I, Hoetzenecker W, Weidinger S, et al. Sézary syndrome and atopic dermatitis: comparison of immunological aspects and targets [published online May 17, 2016]. BioMed Res Int. doi:10.1155/2016/9717530.

- Sigurdsson V, Toonstra J, Bihari IC, et al. Interleukin 4 and interferon-gamma expression of the dermal infiltrate in patients with erythroderma and mycosis fungoides. an immuno-histochemical study. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:429-435.

Patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) often are diagnosed with atopic dermatitis (AD) or psoriasis before receiving their CTCL diagnosis. The effects of new biologic therapies for AD such as dupilumab, an IL-4/IL-13 antagonist, on CTCL are unknown. Dupilumab may be beneficial in CTCL given that helper T cell (TH2) cytokines are increased in advanced CTCL.1 We present a patient with definitive CTCL and concomitant AD who was safely treated with dupilumab and experienced improvement in both CTCL and AD.

Case Report

A 68-year-old man presented with increased itching from AD and a new rash on the arms, neck, chest, back, and lower extremities (Figures 1A and 2A). He had a medical history of AD and CTCL diagnosed by biopsy and peripheral blood flow cytometry (stage IVA1 [T4N0M0B2]) that was being treated with comprehensive multimodality therapy consisting of bexarotene 375 mg daily, interferon alfa-2b 3 mIU 3 times weekly, interferon gamma-1b 2 mIU 3 times weekly, total skin electron beam therapy followed by narrowband UVB twice weekly, and extracorporeal photopheresis every 4 weeks, which resulted in a partial clinical response for 6 months. A biopsy performed at the current presentation showed focal spongiosis and features of lichen simplex chronicus with no evidence suggestive of CTCL. Peripheral blood flow cytometry showed stable B1-staged disease burden (CD4/CD8, 2.6:1); CD4+/CD7−, 12% [91/µL]; CD4+/CD26−, 21% [155/µL]). Treatment with potent and superpotent topical steroids was attempted for more than 6 months and was unsuccessful in relieving the symptoms.

Given the recalcitrant nature of the patient’s rash and itching, dupilumab was added to his CTCL regimen. Prior to initiating dupilumab, the patient reported a numeric rating scale itch intensity of 7 out of 10. After 4 weeks of treatment with dupilumab, the patient reported a numeric rating scale itch intensity of 1. Over a 3-month period, the patient’s rash improved dramatically (Figures 1B and 2B), making it possible to decrease CTCL treatments—bexarotene decreased to 300 mg, interferon alfa-2b to 3 mIU twice weekly, interferon gamma-1b to 2 mIU twice weekly, extracorporeal photopheresis every 5 weeks, and narrowband UVB was discontinued completely. A comparison of the patient’s flow cytometry analysis from before treatment to 3 months after dupilumab showed an overall slight reduction in CTCL B1 blood involvement and normalization of the patient’s absolute eosinophil count and serum lactate dehydrogenase level. The patient tolerated the treatment well without any adverse events and has maintained clinical response for 6 months.

Comment

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas represent a heterogeneous group of T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders involving the skin.2 The definitive diagnosis of CTCL is challenging, as the clinical and pathologic features often are nonspecific in early disease. Frequently, undiagnosed patients are treated empirically with immunosuppressive agents. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and cyclosporine are both associated with progression or worsening of undiagnosed CTCL.3,4 Dupilumab was the first US Food and Drug Administration–approved biologic for the treatment of moderate to severe AD. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma has immunologic features, such as TH2 skewing, that overlap with AD; however, the effects of dupilumab in CTCL are not yet known.5,6 Our group has seen patients initially thought to have AD who received dupilumab without improvement and were subsequently diagnosed with CTCL, suggesting dupilumab did not affect CTCL tumor cells. Given these findings, there was concern that dupilumab might exacerbate undiagnosed CTCL. Our patient with definitive, severe, refractory CTCL noted marked improvement in both AD and underlying CTCL with the addition of dupilumab. No other treatments were added. The response was so dramatic that we were able to wean the doses and frequencies of several CTCL treatments. Our findings suggest that dupilumab may be beneficial in a certain subset of CTCL patients with a history of AD or known concomitant AD. Prospective studies are needed to fully investigate dupilumab safety and efficacy in CTCL and whether it has any primary effects on tumor burden in addition to benefit for itch and skin symptom relief.

Patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) often are diagnosed with atopic dermatitis (AD) or psoriasis before receiving their CTCL diagnosis. The effects of new biologic therapies for AD such as dupilumab, an IL-4/IL-13 antagonist, on CTCL are unknown. Dupilumab may be beneficial in CTCL given that helper T cell (TH2) cytokines are increased in advanced CTCL.1 We present a patient with definitive CTCL and concomitant AD who was safely treated with dupilumab and experienced improvement in both CTCL and AD.

Case Report

A 68-year-old man presented with increased itching from AD and a new rash on the arms, neck, chest, back, and lower extremities (Figures 1A and 2A). He had a medical history of AD and CTCL diagnosed by biopsy and peripheral blood flow cytometry (stage IVA1 [T4N0M0B2]) that was being treated with comprehensive multimodality therapy consisting of bexarotene 375 mg daily, interferon alfa-2b 3 mIU 3 times weekly, interferon gamma-1b 2 mIU 3 times weekly, total skin electron beam therapy followed by narrowband UVB twice weekly, and extracorporeal photopheresis every 4 weeks, which resulted in a partial clinical response for 6 months. A biopsy performed at the current presentation showed focal spongiosis and features of lichen simplex chronicus with no evidence suggestive of CTCL. Peripheral blood flow cytometry showed stable B1-staged disease burden (CD4/CD8, 2.6:1); CD4+/CD7−, 12% [91/µL]; CD4+/CD26−, 21% [155/µL]). Treatment with potent and superpotent topical steroids was attempted for more than 6 months and was unsuccessful in relieving the symptoms.

Given the recalcitrant nature of the patient’s rash and itching, dupilumab was added to his CTCL regimen. Prior to initiating dupilumab, the patient reported a numeric rating scale itch intensity of 7 out of 10. After 4 weeks of treatment with dupilumab, the patient reported a numeric rating scale itch intensity of 1. Over a 3-month period, the patient’s rash improved dramatically (Figures 1B and 2B), making it possible to decrease CTCL treatments—bexarotene decreased to 300 mg, interferon alfa-2b to 3 mIU twice weekly, interferon gamma-1b to 2 mIU twice weekly, extracorporeal photopheresis every 5 weeks, and narrowband UVB was discontinued completely. A comparison of the patient’s flow cytometry analysis from before treatment to 3 months after dupilumab showed an overall slight reduction in CTCL B1 blood involvement and normalization of the patient’s absolute eosinophil count and serum lactate dehydrogenase level. The patient tolerated the treatment well without any adverse events and has maintained clinical response for 6 months.

Comment

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas represent a heterogeneous group of T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders involving the skin.2 The definitive diagnosis of CTCL is challenging, as the clinical and pathologic features often are nonspecific in early disease. Frequently, undiagnosed patients are treated empirically with immunosuppressive agents. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and cyclosporine are both associated with progression or worsening of undiagnosed CTCL.3,4 Dupilumab was the first US Food and Drug Administration–approved biologic for the treatment of moderate to severe AD. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma has immunologic features, such as TH2 skewing, that overlap with AD; however, the effects of dupilumab in CTCL are not yet known.5,6 Our group has seen patients initially thought to have AD who received dupilumab without improvement and were subsequently diagnosed with CTCL, suggesting dupilumab did not affect CTCL tumor cells. Given these findings, there was concern that dupilumab might exacerbate undiagnosed CTCL. Our patient with definitive, severe, refractory CTCL noted marked improvement in both AD and underlying CTCL with the addition of dupilumab. No other treatments were added. The response was so dramatic that we were able to wean the doses and frequencies of several CTCL treatments. Our findings suggest that dupilumab may be beneficial in a certain subset of CTCL patients with a history of AD or known concomitant AD. Prospective studies are needed to fully investigate dupilumab safety and efficacy in CTCL and whether it has any primary effects on tumor burden in addition to benefit for itch and skin symptom relief.

- Guenova E, Watanabe R, Teague JE, et al. TH2 cytokines from malignant cells suppress TH1 responses and enforce a global TH2 bias in leukemic cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:3755-3763.

- Wilcox RA. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: 2016 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:151-165.

- Martinez-Escala ME, Posligua AL, Wickless H, et al. Progression of undiagnosed cutaneous lymphoma after anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1068-1076.

- Pielop JA, Jones D, Duvic M. Transient CD30+ nodal transformation of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma associated with cyclosporine treatment. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:505-511.

- Saulite I, Hoetzenecker W, Weidinger S, et al. Sézary syndrome and atopic dermatitis: comparison of immunological aspects and targets [published online May 17, 2016]. BioMed Res Int. doi:10.1155/2016/9717530.

- Sigurdsson V, Toonstra J, Bihari IC, et al. Interleukin 4 and interferon-gamma expression of the dermal infiltrate in patients with erythroderma and mycosis fungoides. an immuno-histochemical study. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:429-435.

- Guenova E, Watanabe R, Teague JE, et al. TH2 cytokines from malignant cells suppress TH1 responses and enforce a global TH2 bias in leukemic cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:3755-3763.

- Wilcox RA. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: 2016 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:151-165.

- Martinez-Escala ME, Posligua AL, Wickless H, et al. Progression of undiagnosed cutaneous lymphoma after anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1068-1076.

- Pielop JA, Jones D, Duvic M. Transient CD30+ nodal transformation of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma associated with cyclosporine treatment. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:505-511.

- Saulite I, Hoetzenecker W, Weidinger S, et al. Sézary syndrome and atopic dermatitis: comparison of immunological aspects and targets [published online May 17, 2016]. BioMed Res Int. doi:10.1155/2016/9717530.

- Sigurdsson V, Toonstra J, Bihari IC, et al. Interleukin 4 and interferon-gamma expression of the dermal infiltrate in patients with erythroderma and mycosis fungoides. an immuno-histochemical study. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:429-435.

Practice Points

- The diagnosis of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), particularly early-stage disease, remains challenging and often requires a combination of serial clinical evaluations as well as laboratory diagnostic examinations.

- Dupilumab and its effect on helper T cell (TH2) skewing may play a role in the future management of CTCL.

Erythematous Plaques and Nodules on the Abdomen and Groin

The Diagnosis: Inflammatory Urothelial Carcinoma

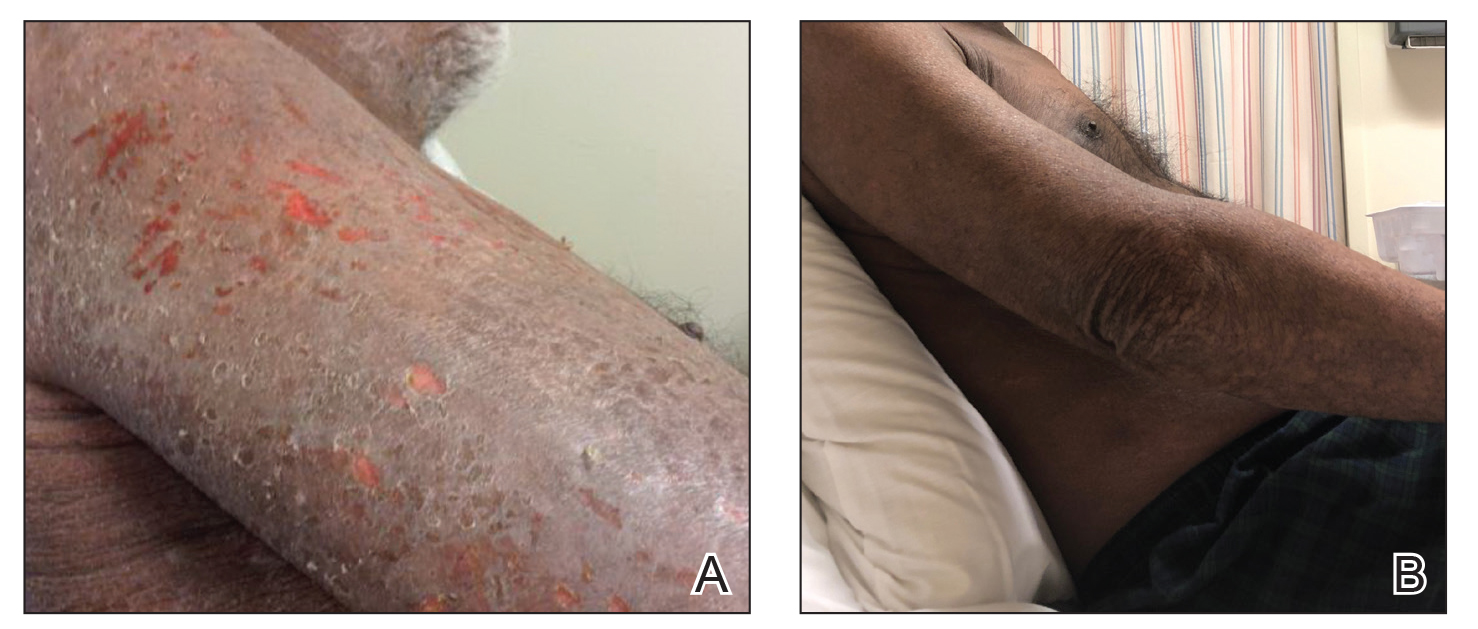

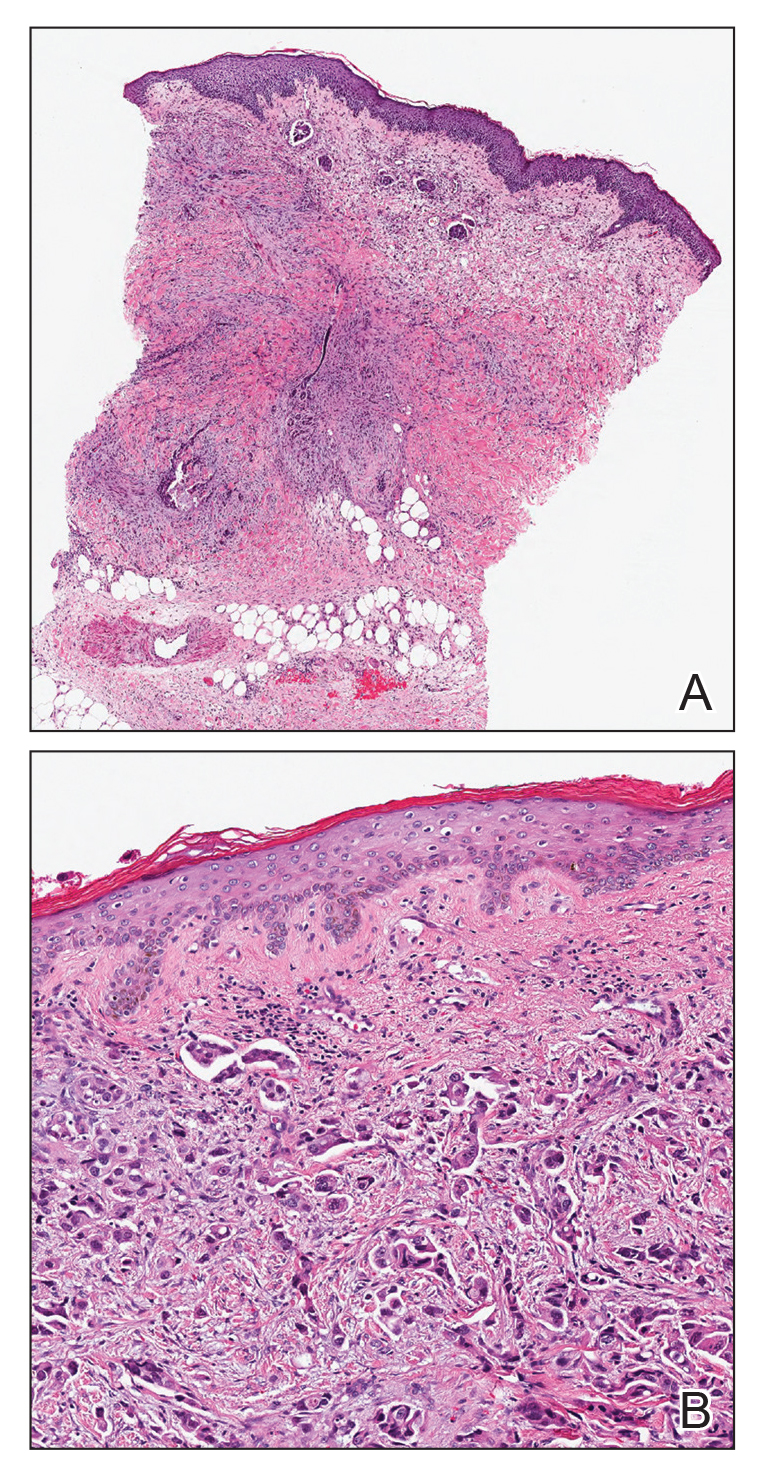

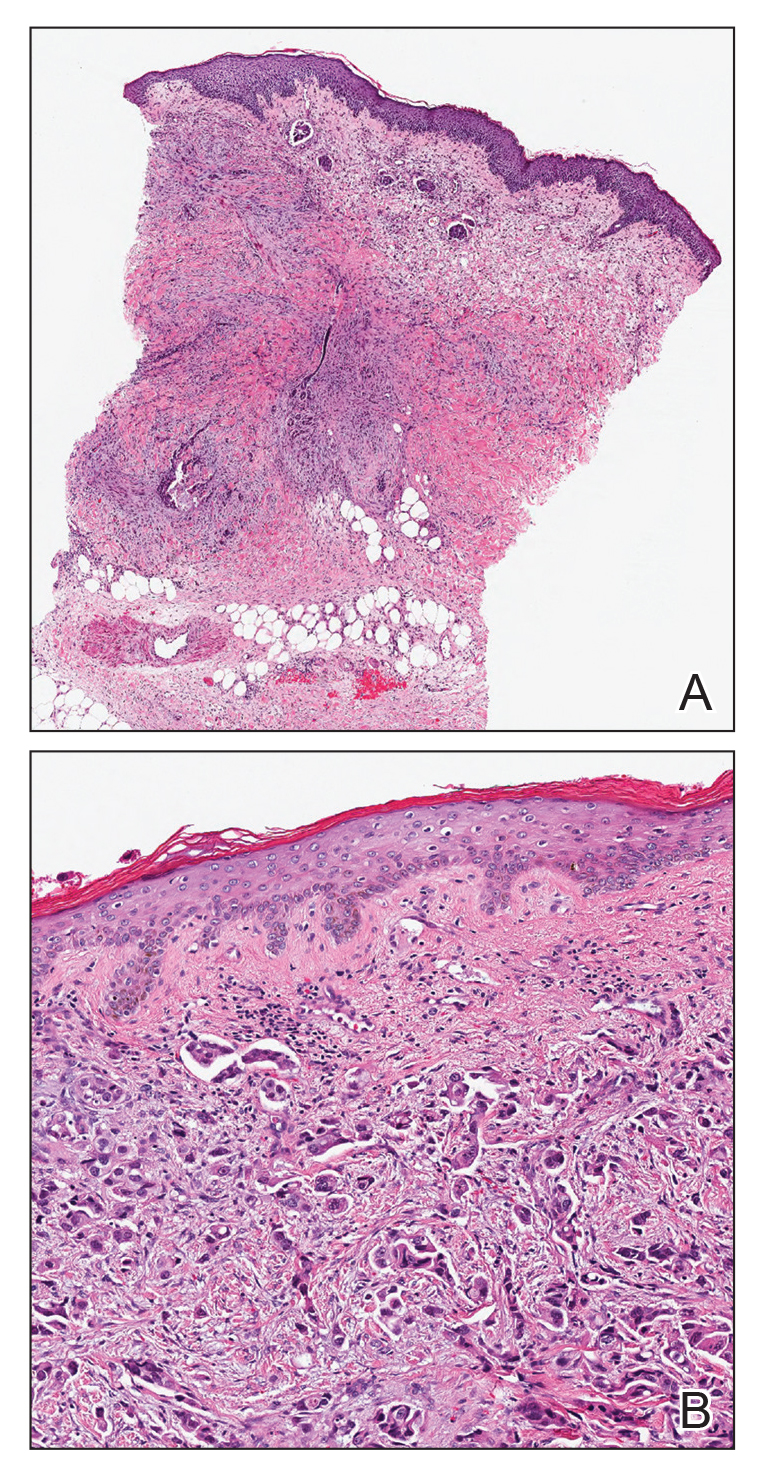

Microscopic examination revealed metastatic carcinoma with extensive dermal lymphatic invasion (Figure). Immunohistochemical stains were positive for p63 and GATA3, markers for urothelial carcinomas, and negative for S-100 and Melan-A, markers for melanoma. Thus, the biopsy was compatible with a diagnosis of urothelial carcinoma. Gram and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stains were negative for bacterial or fungal organisms. An additional 4-mm punch biopsy was performed of the left thigh at the distal-most aspect of the eruption to determine the extent of cutaneous metastasis. Pathology again showed metastatic urothelial carcinoma with extensive dermal lymphatic involvement and overlying epidermal spongiosis.

The patient had a history of bladder cancer diagnosed 1.5 years prior to presentation. It was a high-grade (World Health Organization) urothelial carcinoma that penetrated the bladder muscular wall, focally infiltrating into pericystic fat with multifocal seeding of pericystic lymphatics. It was unresponsive to bacillus Calmette-Guérin therapy. He underwent a cystoprostatectomy and bilateral staging lymph node dissection with clear surgical margins without adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation. He also reported a history of 2 prior cutaneous melanomas that were excised without sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Four months prior to presentation, he developed a mildly pruritic cutaneous eruption on the abdomen that was treated with topical miconazole for presumed tinea cruris without improvement. He also was previously diagnosed with candidiasis of his urostomy and was taking oral fluconazole. The patient was admitted for the abdominal pain and distension, and computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis revealed peritoneal carcinomatosis resulting in mechanical small bowel obstruction as well as enlarged pelvic and retroperitoneal lymph nodes. Confirmation of metastatic disease via skin biopsy avoided an invasive peritoneal biopsy. He was treated with triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% with moderate relief of pruritus, and a palliative percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube was placed for bowel decompression. The patient's hospital course was complicated by Proteus mirabilis bacteremia requiring cefepime. He was transitioned to home hospice and died 1 month after presentation.

Inflammatory carcinoma, also called carcinoma erysipeloides, is a type of cutaneous metastasis most commonly seen in breast adenocarcinoma. Reported cases secondary to urothelial carcinoma are rare and most often involve the abdomen, groin, and lower extremities.1-5 Clinically, inflammatory carcinoma presents as erythematous indurated patches or plaques with well-defined borders, often with edema, warmth, and tenderness. Its morphologic appearance is due to the obstruction of lymphatic vessels by tumor cells and the release of inflammatory cytokines. Its presentation can mimic other dermatoses such as cellulitis, erysipelas, fungal infection, radiation dermatitis, Majocchi granuloma, or contact dermatitis.6 Cutaneous metastases may be the first clinical manifestations of metastatic disease, and they may occur due to hematogenous and lymphatic spread, direct contiguous tissue invasion, or iatrogenic implantation following surgical excision of the primary tumor. Histologically, nuclear markers GATA3 and p63 stain positively in urothelial carcinomas and are negative in prostatic adenocarcinomas.7,8 Other markers may be used such as cytokeratins 7 and 20, which are cytoplasmic epithelial markers that both stain positive in urothelial neoplasms.9

Inflammatory carcinoma may be treated with radiation or systemic chemotherapy depending on the extent of systemic involvement in the patient; however, its presence portends a poor prognosis. Less than 1% of genitourinary malignancies have cutaneous involvement, and median disease-specific survival is less than 6 months from presentation of the cutaneous metastasis.10 Clinicians faced with a recalcitrant inflammatory cutaneous eruption should maintain a high index of suspicion for cutaneous metastases, particularly in patients with a history of cancer. Early dermatology referral may help establish the diagnosis and guide disease-targeted therapy or goals of care discussions.

- Grace SA, Livingood MR, Boyd AS. Metastatic urothelial carcinoma presenting as carcinoma erysipeloides. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:513-515.

- Zangrilli A, Saraceno R, Sarmati L, et al. Erysipeloid cutaneous metastasis from bladder carcinoma. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:534-536.

- Chang CP, Lee Y, Shih HJ. Unusual presentation of cutaneous metastasis from bladder urothelial carcinoma. Chin J Cancer Res. 2013;25:362-365.

- Aloi F, Solaroli C, Paradiso M, et al. Inflammatory type cutaneous metastasis of bladder neoplasm: erysipeloid carcinoma [in Italian]. Minerva Urol Nefrol. 1998;50:205-208.

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rutten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

- Al Ameer A, Imran M, Kaliyadan F, et al. Carcinoma erysipeloides as a presenting feature of breast carcinoma: a case report and brief review of literature. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:396-398.

- Chang A, Amin A, Gabrielson E, et al. Utility of GATA3 immunohistochemistry in differentiating urothelial carcinoma from prostate adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinomas of the uterine cervix, anus, and lung. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:1472-1476.

- Ud Din N, Qureshi A, Mansoor S. Utility of p63 immunohistochemical stain in differentiating urothelial carcinomas from adenocarcinomas of prostate. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2011;54:59-62.

- Bassily NH, Vallorosi CJ, Akdas G, et al. Coordinate expression of cytokeratins 7 and 20 in prostate adenocarcinoma and bladder urothelial carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;113:383-388.

- Mueller TJ, Wu H, Greenberg RE, et al. Cutaneous metastases from genitourinary malignancies. Urology. 2004;63:1021-1026.

The Diagnosis: Inflammatory Urothelial Carcinoma

Microscopic examination revealed metastatic carcinoma with extensive dermal lymphatic invasion (Figure). Immunohistochemical stains were positive for p63 and GATA3, markers for urothelial carcinomas, and negative for S-100 and Melan-A, markers for melanoma. Thus, the biopsy was compatible with a diagnosis of urothelial carcinoma. Gram and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stains were negative for bacterial or fungal organisms. An additional 4-mm punch biopsy was performed of the left thigh at the distal-most aspect of the eruption to determine the extent of cutaneous metastasis. Pathology again showed metastatic urothelial carcinoma with extensive dermal lymphatic involvement and overlying epidermal spongiosis.

The patient had a history of bladder cancer diagnosed 1.5 years prior to presentation. It was a high-grade (World Health Organization) urothelial carcinoma that penetrated the bladder muscular wall, focally infiltrating into pericystic fat with multifocal seeding of pericystic lymphatics. It was unresponsive to bacillus Calmette-Guérin therapy. He underwent a cystoprostatectomy and bilateral staging lymph node dissection with clear surgical margins without adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation. He also reported a history of 2 prior cutaneous melanomas that were excised without sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Four months prior to presentation, he developed a mildly pruritic cutaneous eruption on the abdomen that was treated with topical miconazole for presumed tinea cruris without improvement. He also was previously diagnosed with candidiasis of his urostomy and was taking oral fluconazole. The patient was admitted for the abdominal pain and distension, and computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis revealed peritoneal carcinomatosis resulting in mechanical small bowel obstruction as well as enlarged pelvic and retroperitoneal lymph nodes. Confirmation of metastatic disease via skin biopsy avoided an invasive peritoneal biopsy. He was treated with triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% with moderate relief of pruritus, and a palliative percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube was placed for bowel decompression. The patient's hospital course was complicated by Proteus mirabilis bacteremia requiring cefepime. He was transitioned to home hospice and died 1 month after presentation.

Inflammatory carcinoma, also called carcinoma erysipeloides, is a type of cutaneous metastasis most commonly seen in breast adenocarcinoma. Reported cases secondary to urothelial carcinoma are rare and most often involve the abdomen, groin, and lower extremities.1-5 Clinically, inflammatory carcinoma presents as erythematous indurated patches or plaques with well-defined borders, often with edema, warmth, and tenderness. Its morphologic appearance is due to the obstruction of lymphatic vessels by tumor cells and the release of inflammatory cytokines. Its presentation can mimic other dermatoses such as cellulitis, erysipelas, fungal infection, radiation dermatitis, Majocchi granuloma, or contact dermatitis.6 Cutaneous metastases may be the first clinical manifestations of metastatic disease, and they may occur due to hematogenous and lymphatic spread, direct contiguous tissue invasion, or iatrogenic implantation following surgical excision of the primary tumor. Histologically, nuclear markers GATA3 and p63 stain positively in urothelial carcinomas and are negative in prostatic adenocarcinomas.7,8 Other markers may be used such as cytokeratins 7 and 20, which are cytoplasmic epithelial markers that both stain positive in urothelial neoplasms.9

Inflammatory carcinoma may be treated with radiation or systemic chemotherapy depending on the extent of systemic involvement in the patient; however, its presence portends a poor prognosis. Less than 1% of genitourinary malignancies have cutaneous involvement, and median disease-specific survival is less than 6 months from presentation of the cutaneous metastasis.10 Clinicians faced with a recalcitrant inflammatory cutaneous eruption should maintain a high index of suspicion for cutaneous metastases, particularly in patients with a history of cancer. Early dermatology referral may help establish the diagnosis and guide disease-targeted therapy or goals of care discussions.

The Diagnosis: Inflammatory Urothelial Carcinoma

Microscopic examination revealed metastatic carcinoma with extensive dermal lymphatic invasion (Figure). Immunohistochemical stains were positive for p63 and GATA3, markers for urothelial carcinomas, and negative for S-100 and Melan-A, markers for melanoma. Thus, the biopsy was compatible with a diagnosis of urothelial carcinoma. Gram and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stains were negative for bacterial or fungal organisms. An additional 4-mm punch biopsy was performed of the left thigh at the distal-most aspect of the eruption to determine the extent of cutaneous metastasis. Pathology again showed metastatic urothelial carcinoma with extensive dermal lymphatic involvement and overlying epidermal spongiosis.

The patient had a history of bladder cancer diagnosed 1.5 years prior to presentation. It was a high-grade (World Health Organization) urothelial carcinoma that penetrated the bladder muscular wall, focally infiltrating into pericystic fat with multifocal seeding of pericystic lymphatics. It was unresponsive to bacillus Calmette-Guérin therapy. He underwent a cystoprostatectomy and bilateral staging lymph node dissection with clear surgical margins without adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation. He also reported a history of 2 prior cutaneous melanomas that were excised without sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Four months prior to presentation, he developed a mildly pruritic cutaneous eruption on the abdomen that was treated with topical miconazole for presumed tinea cruris without improvement. He also was previously diagnosed with candidiasis of his urostomy and was taking oral fluconazole. The patient was admitted for the abdominal pain and distension, and computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis revealed peritoneal carcinomatosis resulting in mechanical small bowel obstruction as well as enlarged pelvic and retroperitoneal lymph nodes. Confirmation of metastatic disease via skin biopsy avoided an invasive peritoneal biopsy. He was treated with triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% with moderate relief of pruritus, and a palliative percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube was placed for bowel decompression. The patient's hospital course was complicated by Proteus mirabilis bacteremia requiring cefepime. He was transitioned to home hospice and died 1 month after presentation.

Inflammatory carcinoma, also called carcinoma erysipeloides, is a type of cutaneous metastasis most commonly seen in breast adenocarcinoma. Reported cases secondary to urothelial carcinoma are rare and most often involve the abdomen, groin, and lower extremities.1-5 Clinically, inflammatory carcinoma presents as erythematous indurated patches or plaques with well-defined borders, often with edema, warmth, and tenderness. Its morphologic appearance is due to the obstruction of lymphatic vessels by tumor cells and the release of inflammatory cytokines. Its presentation can mimic other dermatoses such as cellulitis, erysipelas, fungal infection, radiation dermatitis, Majocchi granuloma, or contact dermatitis.6 Cutaneous metastases may be the first clinical manifestations of metastatic disease, and they may occur due to hematogenous and lymphatic spread, direct contiguous tissue invasion, or iatrogenic implantation following surgical excision of the primary tumor. Histologically, nuclear markers GATA3 and p63 stain positively in urothelial carcinomas and are negative in prostatic adenocarcinomas.7,8 Other markers may be used such as cytokeratins 7 and 20, which are cytoplasmic epithelial markers that both stain positive in urothelial neoplasms.9

Inflammatory carcinoma may be treated with radiation or systemic chemotherapy depending on the extent of systemic involvement in the patient; however, its presence portends a poor prognosis. Less than 1% of genitourinary malignancies have cutaneous involvement, and median disease-specific survival is less than 6 months from presentation of the cutaneous metastasis.10 Clinicians faced with a recalcitrant inflammatory cutaneous eruption should maintain a high index of suspicion for cutaneous metastases, particularly in patients with a history of cancer. Early dermatology referral may help establish the diagnosis and guide disease-targeted therapy or goals of care discussions.

- Grace SA, Livingood MR, Boyd AS. Metastatic urothelial carcinoma presenting as carcinoma erysipeloides. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:513-515.

- Zangrilli A, Saraceno R, Sarmati L, et al. Erysipeloid cutaneous metastasis from bladder carcinoma. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:534-536.

- Chang CP, Lee Y, Shih HJ. Unusual presentation of cutaneous metastasis from bladder urothelial carcinoma. Chin J Cancer Res. 2013;25:362-365.

- Aloi F, Solaroli C, Paradiso M, et al. Inflammatory type cutaneous metastasis of bladder neoplasm: erysipeloid carcinoma [in Italian]. Minerva Urol Nefrol. 1998;50:205-208.

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rutten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

- Al Ameer A, Imran M, Kaliyadan F, et al. Carcinoma erysipeloides as a presenting feature of breast carcinoma: a case report and brief review of literature. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:396-398.

- Chang A, Amin A, Gabrielson E, et al. Utility of GATA3 immunohistochemistry in differentiating urothelial carcinoma from prostate adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinomas of the uterine cervix, anus, and lung. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:1472-1476.

- Ud Din N, Qureshi A, Mansoor S. Utility of p63 immunohistochemical stain in differentiating urothelial carcinomas from adenocarcinomas of prostate. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2011;54:59-62.

- Bassily NH, Vallorosi CJ, Akdas G, et al. Coordinate expression of cytokeratins 7 and 20 in prostate adenocarcinoma and bladder urothelial carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;113:383-388.

- Mueller TJ, Wu H, Greenberg RE, et al. Cutaneous metastases from genitourinary malignancies. Urology. 2004;63:1021-1026.

- Grace SA, Livingood MR, Boyd AS. Metastatic urothelial carcinoma presenting as carcinoma erysipeloides. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:513-515.

- Zangrilli A, Saraceno R, Sarmati L, et al. Erysipeloid cutaneous metastasis from bladder carcinoma. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:534-536.

- Chang CP, Lee Y, Shih HJ. Unusual presentation of cutaneous metastasis from bladder urothelial carcinoma. Chin J Cancer Res. 2013;25:362-365.

- Aloi F, Solaroli C, Paradiso M, et al. Inflammatory type cutaneous metastasis of bladder neoplasm: erysipeloid carcinoma [in Italian]. Minerva Urol Nefrol. 1998;50:205-208.

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rutten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

- Al Ameer A, Imran M, Kaliyadan F, et al. Carcinoma erysipeloides as a presenting feature of breast carcinoma: a case report and brief review of literature. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:396-398.

- Chang A, Amin A, Gabrielson E, et al. Utility of GATA3 immunohistochemistry in differentiating urothelial carcinoma from prostate adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinomas of the uterine cervix, anus, and lung. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:1472-1476.

- Ud Din N, Qureshi A, Mansoor S. Utility of p63 immunohistochemical stain in differentiating urothelial carcinomas from adenocarcinomas of prostate. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2011;54:59-62.

- Bassily NH, Vallorosi CJ, Akdas G, et al. Coordinate expression of cytokeratins 7 and 20 in prostate adenocarcinoma and bladder urothelial carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;113:383-388.

- Mueller TJ, Wu H, Greenberg RE, et al. Cutaneous metastases from genitourinary malignancies. Urology. 2004;63:1021-1026.

An 82-year-old man presented with acute abdominal pain and distension as well as an abdominal rash of 4 months' duration that was expanding despite treatment with topical miconazole. He had a history of melanoma and bladder cancer treated with cystoprostatectomy. He previously was diagnosed with candidiasis of his urostomy and was taking oral fluconazole. Physical examination revealed a large, well-demarcated, erythematous, smooth plaque covering the entire abdomen, scrotum, penis, inguinal folds, and bilateral upper thighs, with several satellite plaques and firm nodules clustered around the umbilicus. An 8-mm punch biopsy of a periumbilical nodule was performed.

Low-Dose Radiotherapy for Primary Cutaneous Anaplastic Large-Cell Lymphoma While on Low-Dose Methotrexate

CD30+ primary cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders (pcLPDs) are the second most common cause of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, accounting for approximately 25% to 30% of cases.1 These disorders comprise a spectrum that includes primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (pcALCL); lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP); and borderline lesions, which share clinicopathologic features of both pcALCL and LyP. Lymphomatoid papulosis is characterized as chronic, recurrent, papular or papulonodular skin lesions that typically are multifocal and regress spontaneously within weeks to months, only leaving small scars with atrophy and/or hyperpigmentation.2 Cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma typically presents as solitary or grouped nodules or tumors that may undergo spontaneous partial or complete regression in approximately 25% of cases3 but often persist if not treated. Patients may have an array of lesions comprising the spectrum of CD30 pcLPDs.4

There is no curative therapy for CD30+ pcLPDs. Although active treatment is not necessary for LyP, low-dose methotrexate (MTX)(10–50 mg weekly) or phototherapy are the preferred initial suppressive therapies for symptomatic patients with scarring, facial lesions, or multiple symptomatic lesions.5 Observation with expectant follow-up is an option in pcALCL, though spontaneous regression is less likely than in LyP. For single or grouped pcALCL lesions, local radiation is the first-line therapy.6 Multifocal pcALCL lesions also can be treated with low-dose MTX,2,5 as in LyP, or local radiation to selected areas. Although local radiotherapy is considered a first-line treatment in pcALCL, there is limited evidence on its clinical efficacy as well as the optimal dose and technique. We report the complete response of refractory pcALCL lesions to low-dose radiation while remaining on MTX weekly without any adverse effects.

Case Report

A 51-year-old woman presented with a 3-year history of CD30+ pcLPD manifesting primarily as pcALCL involving the head and neck, as well as LyP involving the head, arms, and trunk (T3N0M0). For 2 years her treatment regimen included clobetasol propionate cream 0.05% as needed for new lesions and 2 courses of standard-dose localized external beam radiation for larger pcALCL tumors on the right cheek and right side of the chin (Figure 1)(total dose for each course of treatment was 20 Gy and 36 Gy, respectively, each administered over 2–3 weeks). Because new unsightly papulonodules continued to develop on the patient’s face, she subsequently required low-dose oral MTX 30 mg once weekly for suppression of new lesions and was stable on this regimen for a year. However, she experienced an increase in LyP/pcALCL activity on the face during a 2-week break from MTX when she developed a herpes zoster infection on the right side of the forehead.

On physical examination 1 month later, 5 tiny pink papules scattered on the left eyebrow, left cheek, and left side of the chin were noted. She was advised to continue applying the clobetasol cream as needed and was restarted on MTX 10 mg once weekly. However, she developed 2 additional 1-cm nodules on the left side of the chin, neck, and shoulder. Methotrexate was increased to 30 mg once weekly over 2 weeks, which was the original dose prior to interruption, but the nodules grew to 1.5-cm in diameter. Due to their clinical appearance, the nodules were believed to be early pcALCL lesions (Figure 2A). Given the cosmetically sensitive location of the nodules, palliative radiotherapy was recommended rather than observe for possible regression. Based on a prior report by Neelis et al7 demonstrating efficacy of low-dose radiotherapy for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and cutaneous B-cell lymphoma, we recommended starting with low radiation doses. Our patient was treated with 400 cGy twice to the left side of the chin and left side of the neck (800 cGy total at each site) while remaining on MTX 30 mg once weekly. This treatment was well tolerated without side effects and no evidence of radiation dermatitis. On follow-up examination 1 week later, the nodules had regressed and no new lesions were present (Figure 2B).

The patient has stayed on oral MTX and occasionally develops small lesions that quickly resolve with clobetasol cream. She has been followed for 3 years after radiotherapy and all 3 previously irradiated sites have remained recurrence free. Furthermore, she has not developed any new larger nodules or tumors and her MTX dose has been decreased to 15 mg once weekly.

Comment

Local radiotherapy is considered a first-line treatment of pcALCL; however, there is limited evidence on its clinical efficacy as well as the optimal dose and technique. Although no standard dose exists for pcALCL, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines8 recommend doses of 12 to 36 Gy in mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome subtypes of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, which are consistent with guidelines published by the European Society for Medical Oncology.9 High complete response rates have been demonstrated in pcALCL at doses of 34 to 44 Gy6; however, lesions tend to recur elsewhere on the skin in 36% to 41% of patients despite treatment.2,10 Lower doses of radiation therapy would provide several advantages over higher-dose therapy if a complete response could be achieved without greatly increasing the local recurrence rate. In cases of local recurrence, low-dose radiation would more easily permit retreatment of lesions compared to higher doses of radiation. Similarly, in patients with multifocal pcALCL, lower doses of radiotherapy may allow for treatment of larger skin areas while limiting potential treatment risks. Furthermore, low-dose therapy would allow for treatments to be delivered more quickly and with less inconvenience to the patient who is likely to need multiple future treatments to other areas. Low-dose radiation has been described with a favorable efficacy profile for mycosis fungoides7,11 but has not been studied in patients with CD30+ pcLPDs.

Our case is notable because the patient remained on MTX during radiation therapy. B

Conclusion

We reported the use of low-dose radiation therapy for the treatment of localized pcALCL in a patient who remained on low-dose oral MTX. Additional studies will be necessary to more fully evaluate the efficacy of using low-dose radiation both as monotherapy and in combination with MTX for pcALCL.

- Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

- Bekkenk MW, Geelen FA, van Voorst Vader PC, et al. Primary and secondary cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders: a report from the Dutch Cutaneous Lymphoma Group on the long-term follow-up data of 219 patients and guidelines for diagnosis and treatment. Blood. 2000;95:3653-3661.

- Willemze R, Beljaards RC. Spectrum of primary cutaneous CD30 (Ki-1)-positive lymphoproliferative disorders: a proposal for classification and guidelines for management and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:973-980.

- Kadin ME. The spectrum of Ki-1+ cutaneous lymphomas. Curr Probl Dermatol. 1990;19:132-143.

- Vonderheid EC, Sajjadian A, Kadin ME. Methotrexate is effective therapy for lymphomatoid papulosis and other primary cutaneous CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:470-481.

- Yu JB, McNiff JM, Lund MW, et al. Treatment of primary cutaneous CD30+ anaplastic large-cell lymphoma with radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70:1542-1545.

- Neelis KJ, Schimmel EC, Vermeer MH, et al. Low-dose palliative radiotherapy B-cell and T-cell lymphomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74:154-158.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. CD30 lymphoproliferative disorders section in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (Version 3.2016). http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nhl.pdf. Accessed September 26, 2016.

- Willemze R, Hodak E, Zinzani PL, et al; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Primary cutaneous lymphomas: EMSO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up [published online July 17, 2013]. Ann Onc. 2013;24(suppl 6):vi149-vi154.

- Liu HL, Hoppe RT, Kohler S, et al. CD30+ cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders: the Stanford experience in lymphomatoid papulosis and primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:1049-1058.

- Harrison C, Young J, Navi D, et al. Revisiting low dose total skin electron beam radiotherapy in mycosis fungoides. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81:651-657.

- Jaffe N, Farber S, Traggis D, et al. Favorable response of metastatic osteogenic sarcoma to pulse high-dose methotrexate with citrovorum rescue and radiation therapy. Cancer. 1973;31:1367-1373.

- Rosen G, Tefft M, Martinez A, et al. Combination chemotherapy and radiation therapy in the treatment of metastatic osteogenic sarcoma. Cancer. 1975;35:622-630.

- Kim YH, Aye MS, Fayos JV. Radiation necrosis of the scalp: a complication of cranial irradiation and methotrexate. Radiology. 1977;124:813-814.

CD30+ primary cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders (pcLPDs) are the second most common cause of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, accounting for approximately 25% to 30% of cases.1 These disorders comprise a spectrum that includes primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (pcALCL); lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP); and borderline lesions, which share clinicopathologic features of both pcALCL and LyP. Lymphomatoid papulosis is characterized as chronic, recurrent, papular or papulonodular skin lesions that typically are multifocal and regress spontaneously within weeks to months, only leaving small scars with atrophy and/or hyperpigmentation.2 Cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma typically presents as solitary or grouped nodules or tumors that may undergo spontaneous partial or complete regression in approximately 25% of cases3 but often persist if not treated. Patients may have an array of lesions comprising the spectrum of CD30 pcLPDs.4

There is no curative therapy for CD30+ pcLPDs. Although active treatment is not necessary for LyP, low-dose methotrexate (MTX)(10–50 mg weekly) or phototherapy are the preferred initial suppressive therapies for symptomatic patients with scarring, facial lesions, or multiple symptomatic lesions.5 Observation with expectant follow-up is an option in pcALCL, though spontaneous regression is less likely than in LyP. For single or grouped pcALCL lesions, local radiation is the first-line therapy.6 Multifocal pcALCL lesions also can be treated with low-dose MTX,2,5 as in LyP, or local radiation to selected areas. Although local radiotherapy is considered a first-line treatment in pcALCL, there is limited evidence on its clinical efficacy as well as the optimal dose and technique. We report the complete response of refractory pcALCL lesions to low-dose radiation while remaining on MTX weekly without any adverse effects.

Case Report

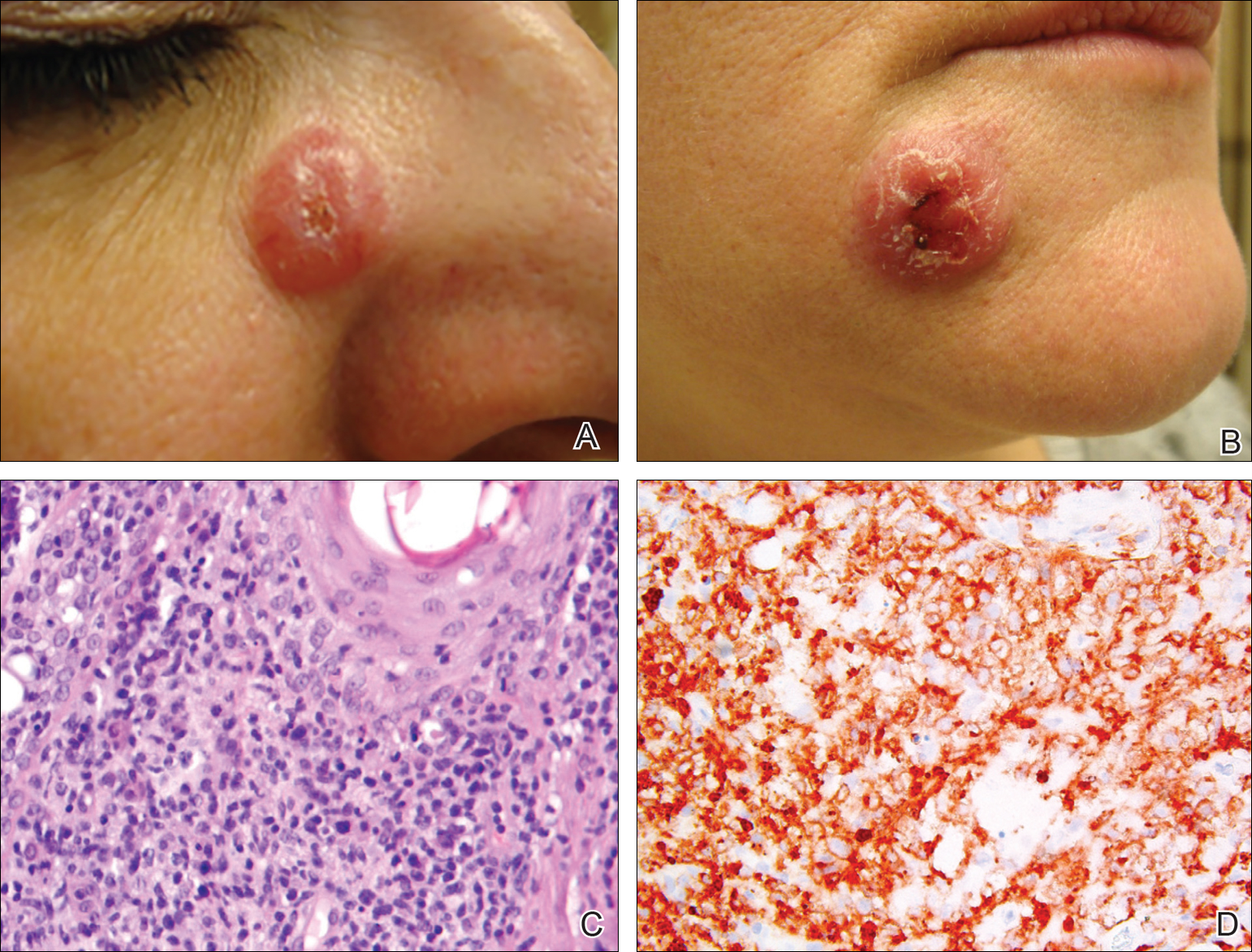

A 51-year-old woman presented with a 3-year history of CD30+ pcLPD manifesting primarily as pcALCL involving the head and neck, as well as LyP involving the head, arms, and trunk (T3N0M0). For 2 years her treatment regimen included clobetasol propionate cream 0.05% as needed for new lesions and 2 courses of standard-dose localized external beam radiation for larger pcALCL tumors on the right cheek and right side of the chin (Figure 1)(total dose for each course of treatment was 20 Gy and 36 Gy, respectively, each administered over 2–3 weeks). Because new unsightly papulonodules continued to develop on the patient’s face, she subsequently required low-dose oral MTX 30 mg once weekly for suppression of new lesions and was stable on this regimen for a year. However, she experienced an increase in LyP/pcALCL activity on the face during a 2-week break from MTX when she developed a herpes zoster infection on the right side of the forehead.

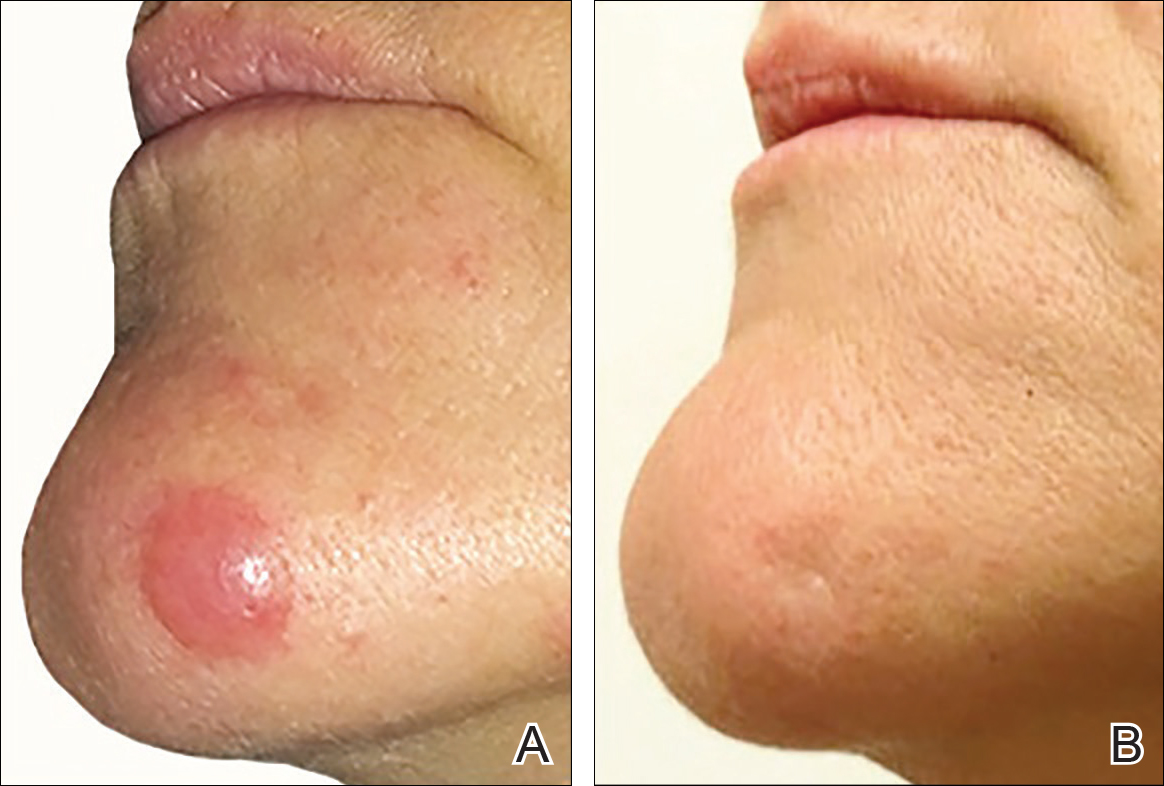

On physical examination 1 month later, 5 tiny pink papules scattered on the left eyebrow, left cheek, and left side of the chin were noted. She was advised to continue applying the clobetasol cream as needed and was restarted on MTX 10 mg once weekly. However, she developed 2 additional 1-cm nodules on the left side of the chin, neck, and shoulder. Methotrexate was increased to 30 mg once weekly over 2 weeks, which was the original dose prior to interruption, but the nodules grew to 1.5-cm in diameter. Due to their clinical appearance, the nodules were believed to be early pcALCL lesions (Figure 2A). Given the cosmetically sensitive location of the nodules, palliative radiotherapy was recommended rather than observe for possible regression. Based on a prior report by Neelis et al7 demonstrating efficacy of low-dose radiotherapy for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and cutaneous B-cell lymphoma, we recommended starting with low radiation doses. Our patient was treated with 400 cGy twice to the left side of the chin and left side of the neck (800 cGy total at each site) while remaining on MTX 30 mg once weekly. This treatment was well tolerated without side effects and no evidence of radiation dermatitis. On follow-up examination 1 week later, the nodules had regressed and no new lesions were present (Figure 2B).

The patient has stayed on oral MTX and occasionally develops small lesions that quickly resolve with clobetasol cream. She has been followed for 3 years after radiotherapy and all 3 previously irradiated sites have remained recurrence free. Furthermore, she has not developed any new larger nodules or tumors and her MTX dose has been decreased to 15 mg once weekly.

Comment

Local radiotherapy is considered a first-line treatment of pcALCL; however, there is limited evidence on its clinical efficacy as well as the optimal dose and technique. Although no standard dose exists for pcALCL, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines8 recommend doses of 12 to 36 Gy in mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome subtypes of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, which are consistent with guidelines published by the European Society for Medical Oncology.9 High complete response rates have been demonstrated in pcALCL at doses of 34 to 44 Gy6; however, lesions tend to recur elsewhere on the skin in 36% to 41% of patients despite treatment.2,10 Lower doses of radiation therapy would provide several advantages over higher-dose therapy if a complete response could be achieved without greatly increasing the local recurrence rate. In cases of local recurrence, low-dose radiation would more easily permit retreatment of lesions compared to higher doses of radiation. Similarly, in patients with multifocal pcALCL, lower doses of radiotherapy may allow for treatment of larger skin areas while limiting potential treatment risks. Furthermore, low-dose therapy would allow for treatments to be delivered more quickly and with less inconvenience to the patient who is likely to need multiple future treatments to other areas. Low-dose radiation has been described with a favorable efficacy profile for mycosis fungoides7,11 but has not been studied in patients with CD30+ pcLPDs.

Our case is notable because the patient remained on MTX during radiation therapy. B

Conclusion

We reported the use of low-dose radiation therapy for the treatment of localized pcALCL in a patient who remained on low-dose oral MTX. Additional studies will be necessary to more fully evaluate the efficacy of using low-dose radiation both as monotherapy and in combination with MTX for pcALCL.

CD30+ primary cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders (pcLPDs) are the second most common cause of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, accounting for approximately 25% to 30% of cases.1 These disorders comprise a spectrum that includes primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (pcALCL); lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP); and borderline lesions, which share clinicopathologic features of both pcALCL and LyP. Lymphomatoid papulosis is characterized as chronic, recurrent, papular or papulonodular skin lesions that typically are multifocal and regress spontaneously within weeks to months, only leaving small scars with atrophy and/or hyperpigmentation.2 Cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma typically presents as solitary or grouped nodules or tumors that may undergo spontaneous partial or complete regression in approximately 25% of cases3 but often persist if not treated. Patients may have an array of lesions comprising the spectrum of CD30 pcLPDs.4

There is no curative therapy for CD30+ pcLPDs. Although active treatment is not necessary for LyP, low-dose methotrexate (MTX)(10–50 mg weekly) or phototherapy are the preferred initial suppressive therapies for symptomatic patients with scarring, facial lesions, or multiple symptomatic lesions.5 Observation with expectant follow-up is an option in pcALCL, though spontaneous regression is less likely than in LyP. For single or grouped pcALCL lesions, local radiation is the first-line therapy.6 Multifocal pcALCL lesions also can be treated with low-dose MTX,2,5 as in LyP, or local radiation to selected areas. Although local radiotherapy is considered a first-line treatment in pcALCL, there is limited evidence on its clinical efficacy as well as the optimal dose and technique. We report the complete response of refractory pcALCL lesions to low-dose radiation while remaining on MTX weekly without any adverse effects.

Case Report

A 51-year-old woman presented with a 3-year history of CD30+ pcLPD manifesting primarily as pcALCL involving the head and neck, as well as LyP involving the head, arms, and trunk (T3N0M0). For 2 years her treatment regimen included clobetasol propionate cream 0.05% as needed for new lesions and 2 courses of standard-dose localized external beam radiation for larger pcALCL tumors on the right cheek and right side of the chin (Figure 1)(total dose for each course of treatment was 20 Gy and 36 Gy, respectively, each administered over 2–3 weeks). Because new unsightly papulonodules continued to develop on the patient’s face, she subsequently required low-dose oral MTX 30 mg once weekly for suppression of new lesions and was stable on this regimen for a year. However, she experienced an increase in LyP/pcALCL activity on the face during a 2-week break from MTX when she developed a herpes zoster infection on the right side of the forehead.

On physical examination 1 month later, 5 tiny pink papules scattered on the left eyebrow, left cheek, and left side of the chin were noted. She was advised to continue applying the clobetasol cream as needed and was restarted on MTX 10 mg once weekly. However, she developed 2 additional 1-cm nodules on the left side of the chin, neck, and shoulder. Methotrexate was increased to 30 mg once weekly over 2 weeks, which was the original dose prior to interruption, but the nodules grew to 1.5-cm in diameter. Due to their clinical appearance, the nodules were believed to be early pcALCL lesions (Figure 2A). Given the cosmetically sensitive location of the nodules, palliative radiotherapy was recommended rather than observe for possible regression. Based on a prior report by Neelis et al7 demonstrating efficacy of low-dose radiotherapy for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and cutaneous B-cell lymphoma, we recommended starting with low radiation doses. Our patient was treated with 400 cGy twice to the left side of the chin and left side of the neck (800 cGy total at each site) while remaining on MTX 30 mg once weekly. This treatment was well tolerated without side effects and no evidence of radiation dermatitis. On follow-up examination 1 week later, the nodules had regressed and no new lesions were present (Figure 2B).

The patient has stayed on oral MTX and occasionally develops small lesions that quickly resolve with clobetasol cream. She has been followed for 3 years after radiotherapy and all 3 previously irradiated sites have remained recurrence free. Furthermore, she has not developed any new larger nodules or tumors and her MTX dose has been decreased to 15 mg once weekly.

Comment

Local radiotherapy is considered a first-line treatment of pcALCL; however, there is limited evidence on its clinical efficacy as well as the optimal dose and technique. Although no standard dose exists for pcALCL, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines8 recommend doses of 12 to 36 Gy in mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome subtypes of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, which are consistent with guidelines published by the European Society for Medical Oncology.9 High complete response rates have been demonstrated in pcALCL at doses of 34 to 44 Gy6; however, lesions tend to recur elsewhere on the skin in 36% to 41% of patients despite treatment.2,10 Lower doses of radiation therapy would provide several advantages over higher-dose therapy if a complete response could be achieved without greatly increasing the local recurrence rate. In cases of local recurrence, low-dose radiation would more easily permit retreatment of lesions compared to higher doses of radiation. Similarly, in patients with multifocal pcALCL, lower doses of radiotherapy may allow for treatment of larger skin areas while limiting potential treatment risks. Furthermore, low-dose therapy would allow for treatments to be delivered more quickly and with less inconvenience to the patient who is likely to need multiple future treatments to other areas. Low-dose radiation has been described with a favorable efficacy profile for mycosis fungoides7,11 but has not been studied in patients with CD30+ pcLPDs.

Our case is notable because the patient remained on MTX during radiation therapy. B

Conclusion

We reported the use of low-dose radiation therapy for the treatment of localized pcALCL in a patient who remained on low-dose oral MTX. Additional studies will be necessary to more fully evaluate the efficacy of using low-dose radiation both as monotherapy and in combination with MTX for pcALCL.

- Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

- Bekkenk MW, Geelen FA, van Voorst Vader PC, et al. Primary and secondary cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders: a report from the Dutch Cutaneous Lymphoma Group on the long-term follow-up data of 219 patients and guidelines for diagnosis and treatment. Blood. 2000;95:3653-3661.

- Willemze R, Beljaards RC. Spectrum of primary cutaneous CD30 (Ki-1)-positive lymphoproliferative disorders: a proposal for classification and guidelines for management and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:973-980.

- Kadin ME. The spectrum of Ki-1+ cutaneous lymphomas. Curr Probl Dermatol. 1990;19:132-143.

- Vonderheid EC, Sajjadian A, Kadin ME. Methotrexate is effective therapy for lymphomatoid papulosis and other primary cutaneous CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:470-481.

- Yu JB, McNiff JM, Lund MW, et al. Treatment of primary cutaneous CD30+ anaplastic large-cell lymphoma with radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70:1542-1545.

- Neelis KJ, Schimmel EC, Vermeer MH, et al. Low-dose palliative radiotherapy B-cell and T-cell lymphomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74:154-158.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. CD30 lymphoproliferative disorders section in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (Version 3.2016). http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nhl.pdf. Accessed September 26, 2016.

- Willemze R, Hodak E, Zinzani PL, et al; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Primary cutaneous lymphomas: EMSO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up [published online July 17, 2013]. Ann Onc. 2013;24(suppl 6):vi149-vi154.

- Liu HL, Hoppe RT, Kohler S, et al. CD30+ cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders: the Stanford experience in lymphomatoid papulosis and primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:1049-1058.

- Harrison C, Young J, Navi D, et al. Revisiting low dose total skin electron beam radiotherapy in mycosis fungoides. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81:651-657.

- Jaffe N, Farber S, Traggis D, et al. Favorable response of metastatic osteogenic sarcoma to pulse high-dose methotrexate with citrovorum rescue and radiation therapy. Cancer. 1973;31:1367-1373.

- Rosen G, Tefft M, Martinez A, et al. Combination chemotherapy and radiation therapy in the treatment of metastatic osteogenic sarcoma. Cancer. 1975;35:622-630.

- Kim YH, Aye MS, Fayos JV. Radiation necrosis of the scalp: a complication of cranial irradiation and methotrexate. Radiology. 1977;124:813-814.

- Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

- Bekkenk MW, Geelen FA, van Voorst Vader PC, et al. Primary and secondary cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders: a report from the Dutch Cutaneous Lymphoma Group on the long-term follow-up data of 219 patients and guidelines for diagnosis and treatment. Blood. 2000;95:3653-3661.

- Willemze R, Beljaards RC. Spectrum of primary cutaneous CD30 (Ki-1)-positive lymphoproliferative disorders: a proposal for classification and guidelines for management and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:973-980.

- Kadin ME. The spectrum of Ki-1+ cutaneous lymphomas. Curr Probl Dermatol. 1990;19:132-143.

- Vonderheid EC, Sajjadian A, Kadin ME. Methotrexate is effective therapy for lymphomatoid papulosis and other primary cutaneous CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:470-481.

- Yu JB, McNiff JM, Lund MW, et al. Treatment of primary cutaneous CD30+ anaplastic large-cell lymphoma with radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70:1542-1545.

- Neelis KJ, Schimmel EC, Vermeer MH, et al. Low-dose palliative radiotherapy B-cell and T-cell lymphomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74:154-158.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. CD30 lymphoproliferative disorders section in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (Version 3.2016). http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nhl.pdf. Accessed September 26, 2016.

- Willemze R, Hodak E, Zinzani PL, et al; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Primary cutaneous lymphomas: EMSO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up [published online July 17, 2013]. Ann Onc. 2013;24(suppl 6):vi149-vi154.

- Liu HL, Hoppe RT, Kohler S, et al. CD30+ cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders: the Stanford experience in lymphomatoid papulosis and primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:1049-1058.

- Harrison C, Young J, Navi D, et al. Revisiting low dose total skin electron beam radiotherapy in mycosis fungoides. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81:651-657.

- Jaffe N, Farber S, Traggis D, et al. Favorable response of metastatic osteogenic sarcoma to pulse high-dose methotrexate with citrovorum rescue and radiation therapy. Cancer. 1973;31:1367-1373.

- Rosen G, Tefft M, Martinez A, et al. Combination chemotherapy and radiation therapy in the treatment of metastatic osteogenic sarcoma. Cancer. 1975;35:622-630.

- Kim YH, Aye MS, Fayos JV. Radiation necrosis of the scalp: a complication of cranial irradiation and methotrexate. Radiology. 1977;124:813-814.

Practice Points

- Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma tumors such as primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma can respond to low-dose radiation therapy, which enables future retreatment of sensitive sites.

- Low-dose radiation therapy requires a shorter course of therapy than traditional dosing, which is more convenient and less costly.