User login

COPD CARE Academy: Design of Purposeful Training Guided by Implementation Strategies

COPD CARE Academy: Design of Purposeful Training Guided by Implementation Strategies

Quality improvement (QI) initiatives within the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) play an important role in enhancing health care for veterans.1,2 While effective QI programs are often developed, veterans benefit only if they receive care at sites where the program is offered.3 It is estimated only 1% to 5% of patients receive benefit from evidence-based programs, limiting the opportunity for widespread impact.4,5

The Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) Coordinated Access to Reduce Exacerbations (CARE) Academy is a national training program designed to promote the adoption of a COPD primary care service.6 The Academy was created and iteratively refined by VA staff to include both clinical training emphasizing COPD management and program implementation strategies. Training programs such as COPD CARE are commonly described as a method to support adoption of health care services, but there is no consensus on a universal approach to training design.

This article describes COPD CARE training and implementation strategies (Table). The Academy began as a training program at 1 VA medical center (VAMC) and has expanded to 49 diverse VAMCs. The Academy illustrates how implementation strategies can be leveraged to develop pragmatic and impactful training. Highlights from the Academy's 9-year history are outlined in this article.

COPD CARE

One in 4 veterans have a COPD diagnosis, and the 5-year mortality rate following a COPD flare is ≥ 50%.7,8 In 2015, a pharmacy resident designed and piloted COPD CARE, a program that used evidence-based practice to optimize management of the disease.9,10

The COPD CARE program is delivered by interprofessional team members. It includes a postacute care call completed 48 hours postdischarge, a wellness visit (face-to-face or virtual) 1 month postdischarge, and a follow-up visit scheduled 2 months postdischarge. Clinical pharmacist practitioners (CPPs) prescribe and collaborate with the COPD CARE health care team. Evidence-based practices embedded within COPD CARE include treatment optimization, symptom evaluation, severity staging, vaccination promotion, referrals, tobacco treatment, and comorbidity management.11-16 The initial COPD CARE pilot demonstrated promising results; patients received timely care and high rates of COPD best practices.11

Academy Design and Implementation

Initial COPD CARE training was tailored to the culture, context, and workflow of the William S. Middleton Memorial Veteran’s Hospital in Madison, Wisconsin. Further service expansion required integration of implementation strategies that enable learners to apply and adapt content to fit different processes, staffing, and patient needs.

Formal Implementation Blueprint

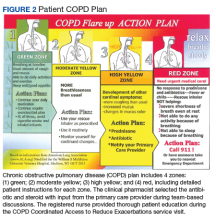

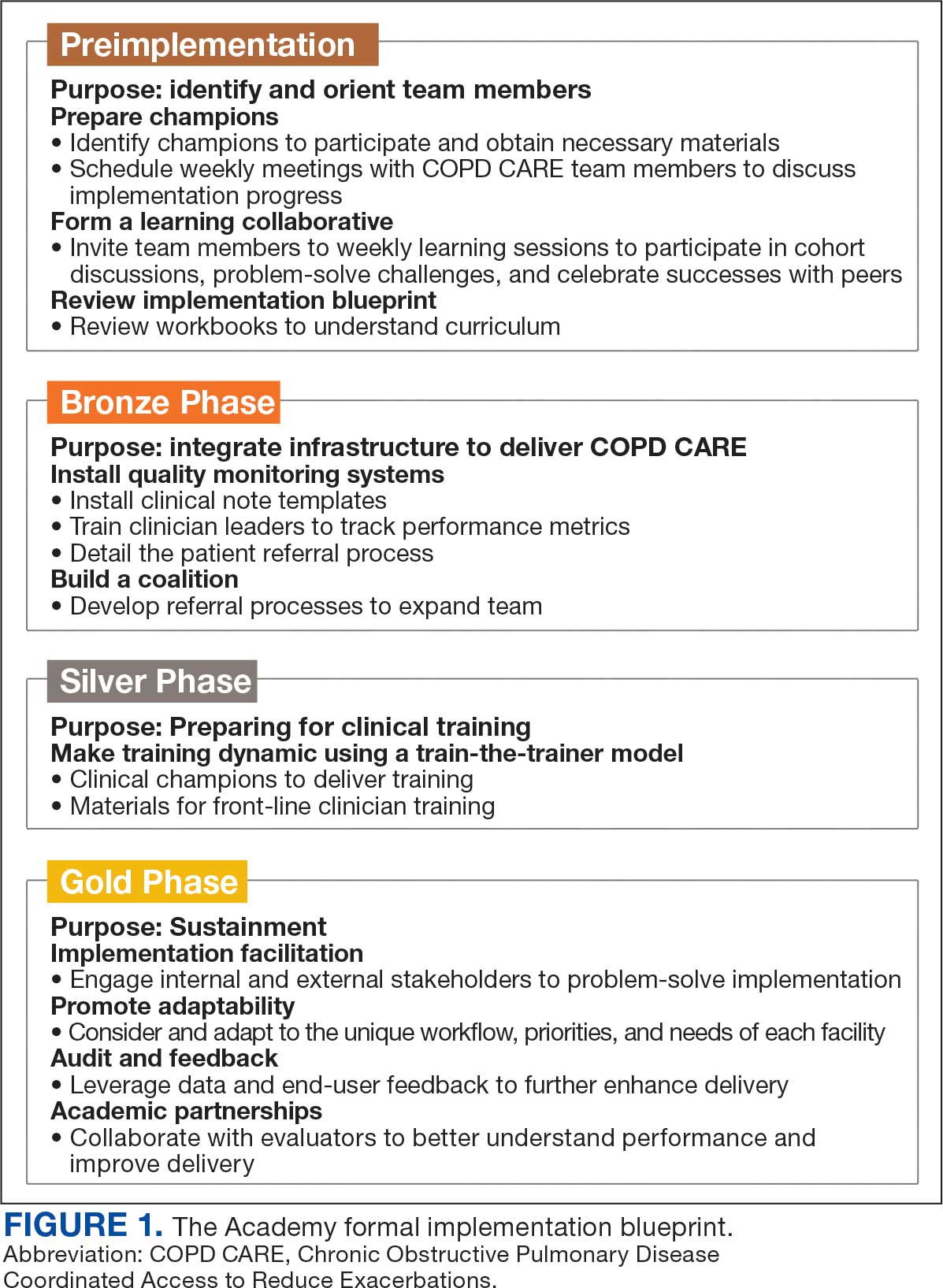

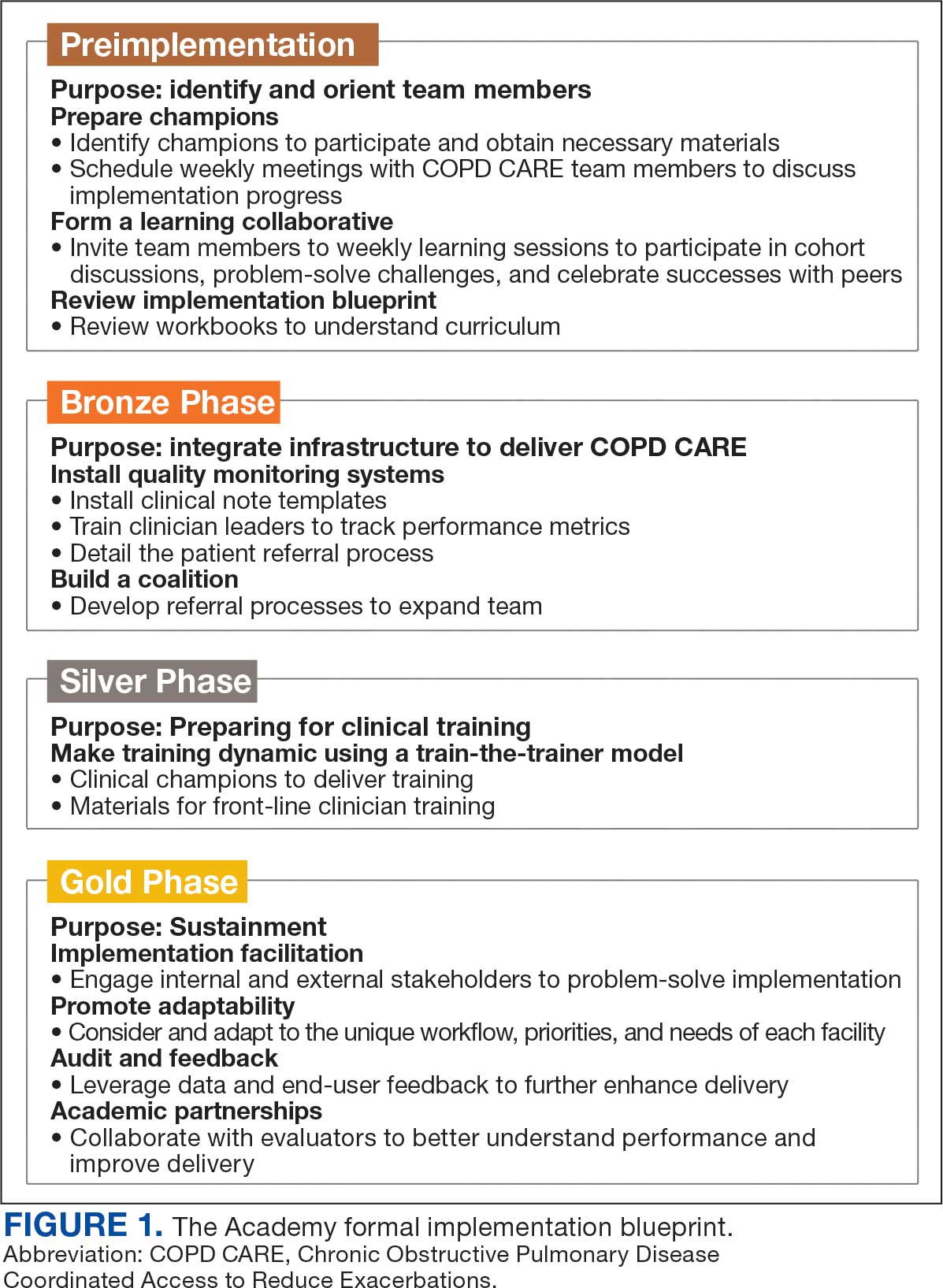

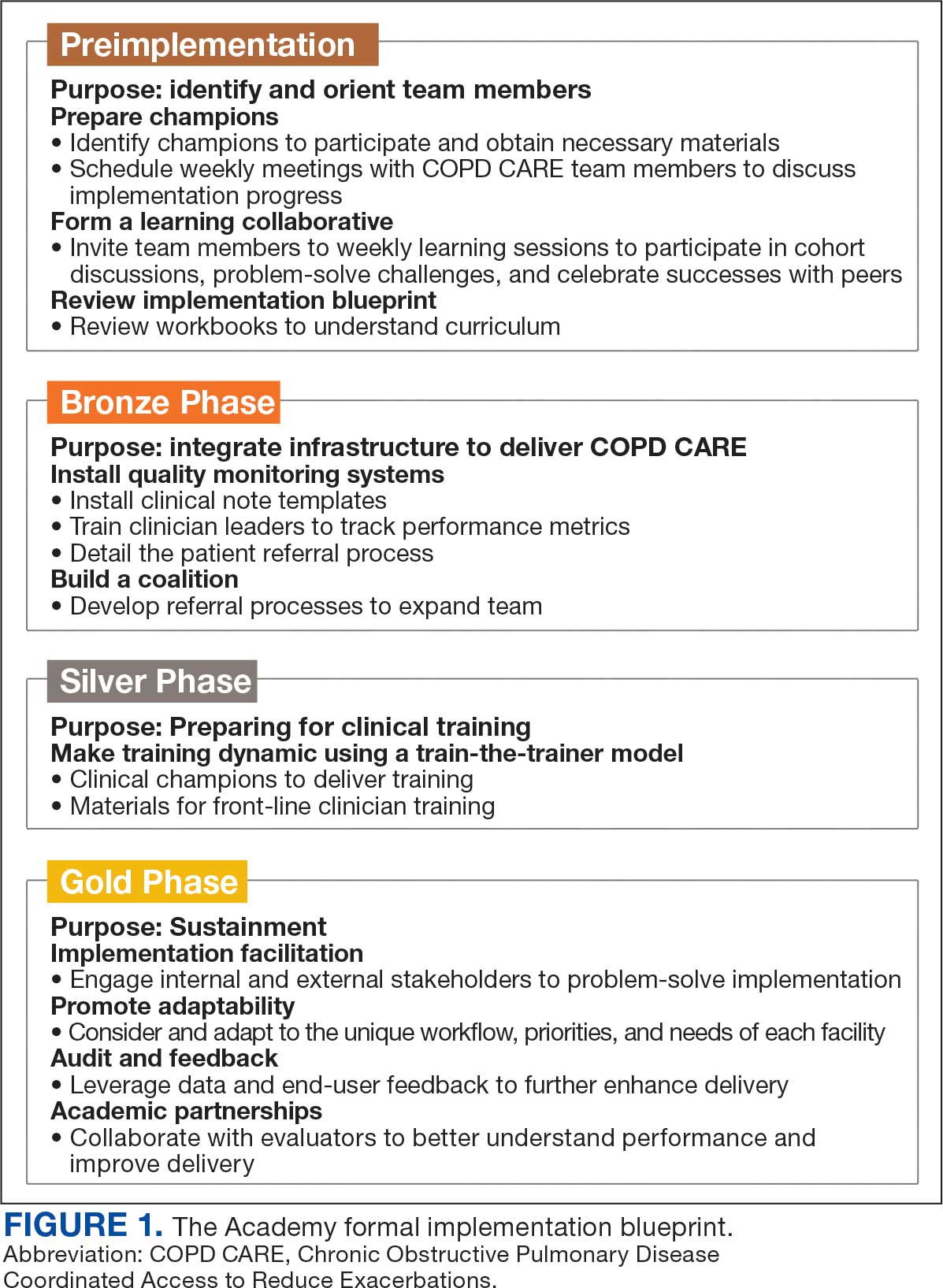

A key aspect of the Academy is the integration of a formal implementation blueprint that includes training goals, scope, and key milestones to guide implementation. The Academy blueprint includes 4 phased training workbooks: (1) preimplementation support from local stakeholders; (2) integration of COPD CARE operational infrastructure into workflows; (3) preparing clinical champions; and (4) leading clinical training (Figure 1). Five weekly 1-hour synchronous virtual discussions are used for learning the workbook content that include learning objectives and opportunities to strategize how to overcome implementation barriers.

Promoting and Facilitating Implementation

As clinicians apply content from the Academy to install informatics tools, coordinate clinical training, and build relationships across service lines, implementation barriers may occur. A learning collaborative allows peer-mentorship and shared problem solving. The Academy learning collaborative includes attendees across multiple VAMCs, allowing for diverse perspectives and cross-site learning. Within the field of dissemination and implementation science, this process of shared problem-solving to support individuals is referred to as implementation facilitation.17 Academy facilitators with prior experience provide a unique perspective and external facilitation from outside local VAMCs. Academy learners form local teams to engage in shared decision-making when applying Academy content. Following Academy completion, learning collaboratives continue to meet monthly to share clinical insights and operational updates.

Local Champions Promote Adaptability

One or more local champions were identified at each VAMC who were focused on the implementation of clinical training content and operational implementation of Academy content.18 Champions have helped develop adaptations of Academy content, such as integrating telehealth nursing within the COPD CARE referral process, which have become new best practices. Champions attend Academy sessions, which provide an opportunity to share adaptations to meet local needs.19

Using a Train-The-Trainer Model

Clinical training was designed to be dynamic and included video modeling, such as recorded examples of CPPs conducting COPD CARE visits and video clips highlighting clinical content. Each learner received a clinical workbook summarizing the content. The champion shares discussion questions to relate training content to the local clinical practice setting. The combination of live training, with videos of clinic visits and case-based discussion was intended to address differing learning styles. Clinical training was delivered using a train-the-trainer model led by the local champion, which allows clinicians with expertise to tailor their training. The use of a train-the-trainer model was intended to promote local buy-in and was often completed by frontline clinicians.

Informatics note templates provide clinicians with information needed to deliver training content during clinic visits. Direct hyperlinks to symptomatic scoring tools, resources to promote evidence-based medication optimization, and patient education resources were embedded within the electronic health record note templates. Direct links to consults for COPD referrals services discussed during clinical training were also included to promote ease of care coordination and awareness of referral opportunities. The integration of clinical training with informatics note template support was intentional to directly relate clinical training to clinical care delivery.

Audit and Feedback

To inform COPD CARE practice, the Academy included informatics infrastructure that allowed for timely local quality monitoring. Electronic health record note templates with embedded data fields track COPD CARE service implementation, including timely completion of patient visits, completion of patient medication reviews, appropriate testing, symptom assessment, and interventions made. Champions can organize template installation and integrate templates into COPD CARE clinical training. Data are included on a COPD CARE implementation dashboard.

An audit and feedback process is allows for the review of performance metrics and development of action plans.20,21 Data reports from note templates are described during the Academy, along with resources to help teams enhance delivery of their program based on performance metrics.

Building a Coalition

Within VA primary care, clinical care delivery is optimized through a team-based coalition of clinicians using the patient aligned care team (PACT) framework. The VA patient-centered team-based care delivery model, patient facilitates coordination of patient referrals, including patient review, scheduling, and completion of patient visits.22

Partnerships with VA Pharmacy Benefits Manager, VA Diffusion of Excellence, VA Quality Enhancement Research Initiative, VA Office of Pulmonary Medicine, and the VA Office of Rural Health have facilitated COPD CARE successes. Collaborations with VA Centers of Innovation helped benchmark the Academy’s impact. An academic partnership with the University of Wisconsin-Madison was established in 2017 and has provided evaluation expertise and leadership as the Academy has been iteratively developed, and revised.

Preliminary Metrics

COPD CARE has delivered > 2000 visits. CPPs have delivered COPD care, with a mean 9.4 of 10 best practices per patient visit. Improvements in veteran COPD symptoms have also been observed following COPD CARE patient visits.

DISCUSSION

The COPD CARE Academy was developed to promote rapid scale-up of a complex, team-based COPD service delivered during veteran care transitions. The implementation blueprint for the Academy is multifaceted and integrates both clinical-focused and implementation-focused infrastructure to apply training content.23 A randomized control trial evaluating the efficacy of training modalities found a need to expand implementation blueprints beyond clinical training alone, as training by itself may not be sufficient to change behavior.24 VA staff designed the Academy using clinical- and implementation-focused content within its implementation blueprint. Key components included leveraging clinical champions, using a train-the-trainer approach, and incorporating facilitation strategies to overcome adoption barriers.

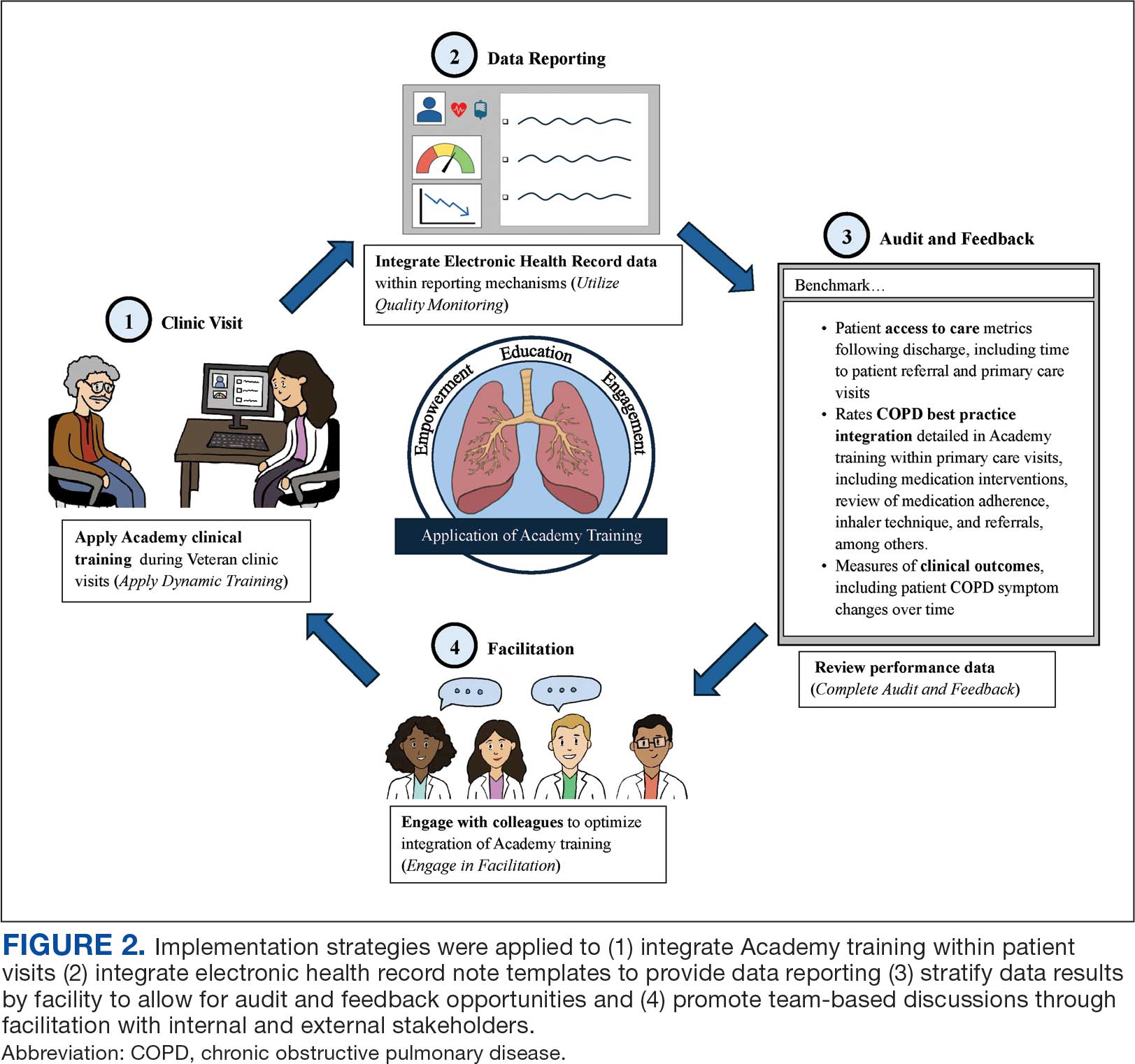

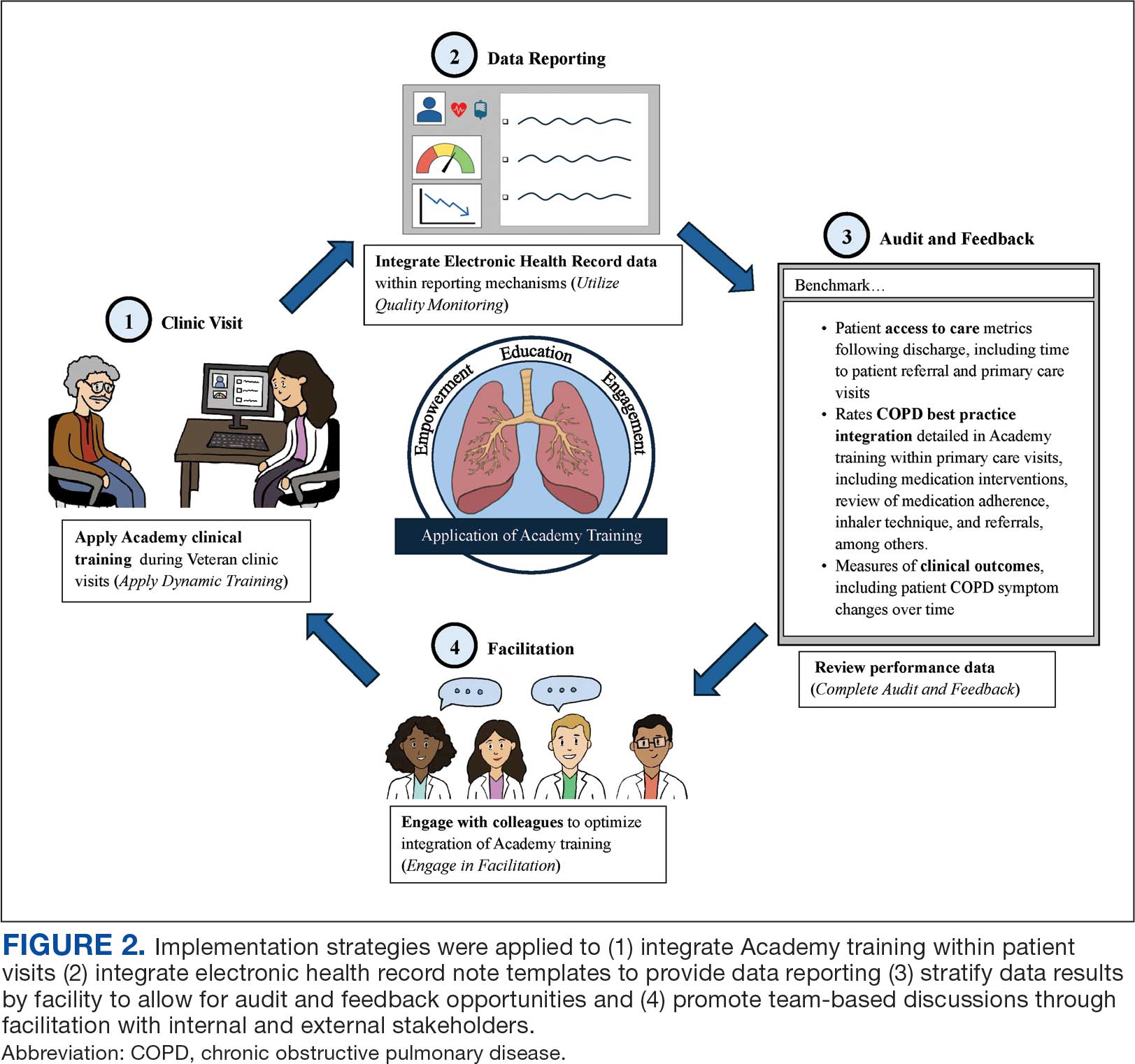

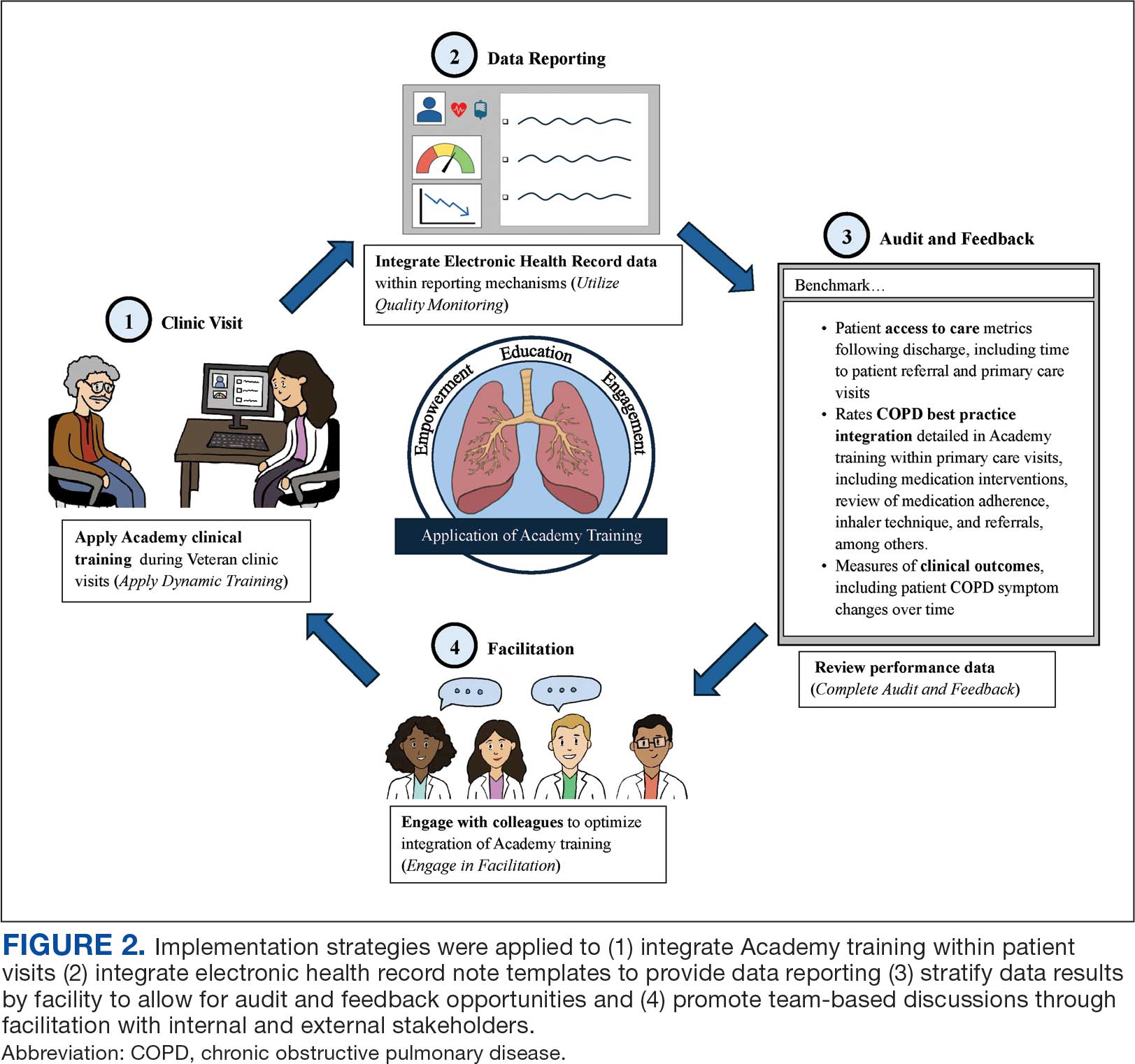

Lewis et al emphasize matching implementation strategies to barriers within VA staff who identify care coordination as a key challenge.23 The informatics infrastructure developed for Academy learners, including standardized note templates, video modeling examples of clinic visits, and data capture for audit and feedback, was designed to complement clinical training and standardize service workflows (Figure 2). There are opportunities to explore how to optimize technology in the Academy.

While Academy clinical training specifically focuses on COPD management, many implementation strategies can be considered to promote care delivery services for other chronic conditions. The Academy blueprint and implementation infrastructure, are strategies that may be considered within and outside the federal health care system. The opportunity for adaptations to Academy training enables clinical champions to promote tailored content to the needs of each unique VAMC. The translation of Academy implementation strategies for new chronic conditions will similarly require adaptations at each VAMC to promote adoption of content.

CONCLUSIONS

COPD CARE Academy is an example of the collaborative spirit within VA, and the opportunity for further advancement of health care programs. The VA is a national leader in Learning Health Systems implementation, in which “science, informatics, incentives and culture are aligned for continuous improvement and innovation.”25,26 There are many opportunities for VA staff to learn from one another to form partnerships between leaders, clinicians, and scientists to optimize health care delivery and further the VA’s work as a learning health system.

- Robinson CH, Thompto AJ, Lima EN, Damschroder LJ. Continuous quality improvement at the frontline: one interdisciplinary clinical team's four-year journey after completing a virtual learning program. Learn Health Syst. 2022;6(4):e10345. doi:10.1002/lrh2.10345

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Continuous quality improvement (CQI) for clinical teams: a systematic review of reviews. Accessed July 24, 2025. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/cyber_seminars/archives/video_archive.cfm?SessionID=4151

- Dondanville KA, Fina BA, Straud CL, et al. Launching a competency-based training program in evidence-based treatments for PTSD: supporting veteran-serving mental health providers in Texas. Community Ment Health J. 2021;57(5):910-919. doi:10.1007/S10597-020-00676-7

- Abildso CG, Zizzi SJ, Reger-Nash B. Evaluating an insurance- sponsored weight management program with the RE-AIM model, West Virginia, 2004-2008. Prev Chronic Dis. 2010;7(3):A46.

- Glasgow RE, Vinson C, Chambers D, Khoury MJ, Kaplan RM, Hunter C. National institutes of health approaches to dissemination and implementation science: current and future directions. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(7):1274- 1281. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.300755

- Portillo EC, Maurer MA, Kettner JT, et al. Applying RE-AIM to examine the impact of an implementation facilitation package to scale up a program for veterans with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Implement Sci Commun. 2023;4(1):143. doi:10.1186/S43058-023-00520-5

- McGhan R, Radcliff T, Fish R, Sutherland ER, Welsh C, Make B. Predictors of rehospitalization and death after a severe exacerbation of COPD. Chest. 2007;132(6):1748- 1755. doi:10.1378/chest.06-3018

- Anderson E, Wiener RS, Resnick K, Elwy AR, Rinne ST. Care coordination for veterans with COPD: a positive deviance study. Am J Manag Care. 2020;26(2):63-68. doi:10.37765/AJMC.2020.42394

- 2024 GOLD Report. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease - GOLD. Accessed July 24, 2025. https://goldcopd.org/2024-gold-report/

- Nici L, Mammen MJ, Charbek E, et al. Pharmacologic management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(9):e56-e69. doi:10.1164/rccm.202003-0625ST

- Portillo EC, Wilcox A, Seckel E, et al. Reducing COPD readmission rates: using a COPD care service during care transitions. Fed Pract. 2018;35(11):30-36.

- Portillo EC, Gruber S, Lehmann M, et al. Application of the replicating effective programs framework to design a COPD training program. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2021;61(2):e129-e135. doi:10.1016/J.JAPH.2020.10.023

- Portillo EC, Lehmann MR, Hagen TL, et al. Integration of the patient-centered medical home to deliver a care bundle for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease management. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2023;63(1):212-219. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2022.10.003

- Portillo E, Lehmann M, Hagen T, et al. Evaluation of an implementation package to deliver the COPD CARE service. BMJ Open Qual. 2023;12(1). doi:10.1136/BMJOQ-2022-002074

- Portillo E, Lehmann M, Maurer M, et al. Barriers to implementing a pharmacist-led COPD care bundle in rural settings: A qualitative evaluation. 2025 (under review).

- Population Health Management. American Hospital Association. Accessed July 24, 2025. https://www.aha.org/center/population-health-management

- Ritchie MJ, Dollar KM, Miller CK, et al. Using implementation facilitation to improve healthcare: implementation facilitation training manual. Accessed July 11, 2024. https:// www.queri.research.va.gov/tools/Facilitation-Manual.pdf

- Morena AL, Gaias LM, Larkin C. Understanding the role of clinical champions and their impact on clinician behavior change: the need for causal pathway mechanisms. Front Health Serv. 2022;2:896885. doi:10.3389/FRHS.2022.896885

- Ayele RA, Rabin BA, McCreight M, Battaglia C. Editorial: understanding, assessing, and guiding adaptations in public health and health systems interventions: current and future directions. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1228437. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2023.1228437

- Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, Ivers N. Audit and feedback as a quality strategy. In: Improving Healthcare Services. World Health Organization; 2019. Accessed July 24, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549284/

- Snider MDH, Boyd MR, Walker MR, Powell BJ, Lewis CC. Using audit and feedback to guide tailored implementations of measurement-based care in community mental health: a multiple case study. Implement Sci Commun. 2023;4(1):94. doi:10.1186/s43058-023-00474-8

- Patient Aligned Care Team (PACT) – Patient Care Services. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Accessed July 24, 2025. https://www.patientcare.va.gov/primarycare/PACT.asp

- Lewis CC, Scott K, Marriott BR. A methodology for generating a tailored implementation blueprint: an exemplar from a youth residential setting. Implementat Sci. 2018;13(1):68. doi:10.1186/s13012-018-0761-6

- Beidas RS, Edmunds JM, Marcus SC, Kendall PC. Training and consultation to promote implementation of an empirically supported treatment: a randomized trial. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(7):660-665. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201100401

- Kilbourne AM, Schmidt J, Edmunds M, Vega R, Bowersox N, Atkins D. How the VA is training the next-generation workforce for learning health systems. Learn Health Syst. 2022;6(4):e10333. doi:10.1002/LRH2.10333

- Easterling D, Perry AC, Woodside R, Patel T, Gesell SB. Clarifying the concept of a learning health system for healthcare delivery organizations: implications from a qualitative analysis of the scientific literature. Learn Health Syst. 2021;6(2):e10287. doi:10.1002/LRH2.10287

Quality improvement (QI) initiatives within the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) play an important role in enhancing health care for veterans.1,2 While effective QI programs are often developed, veterans benefit only if they receive care at sites where the program is offered.3 It is estimated only 1% to 5% of patients receive benefit from evidence-based programs, limiting the opportunity for widespread impact.4,5

The Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) Coordinated Access to Reduce Exacerbations (CARE) Academy is a national training program designed to promote the adoption of a COPD primary care service.6 The Academy was created and iteratively refined by VA staff to include both clinical training emphasizing COPD management and program implementation strategies. Training programs such as COPD CARE are commonly described as a method to support adoption of health care services, but there is no consensus on a universal approach to training design.

This article describes COPD CARE training and implementation strategies (Table). The Academy began as a training program at 1 VA medical center (VAMC) and has expanded to 49 diverse VAMCs. The Academy illustrates how implementation strategies can be leveraged to develop pragmatic and impactful training. Highlights from the Academy's 9-year history are outlined in this article.

COPD CARE

One in 4 veterans have a COPD diagnosis, and the 5-year mortality rate following a COPD flare is ≥ 50%.7,8 In 2015, a pharmacy resident designed and piloted COPD CARE, a program that used evidence-based practice to optimize management of the disease.9,10

The COPD CARE program is delivered by interprofessional team members. It includes a postacute care call completed 48 hours postdischarge, a wellness visit (face-to-face or virtual) 1 month postdischarge, and a follow-up visit scheduled 2 months postdischarge. Clinical pharmacist practitioners (CPPs) prescribe and collaborate with the COPD CARE health care team. Evidence-based practices embedded within COPD CARE include treatment optimization, symptom evaluation, severity staging, vaccination promotion, referrals, tobacco treatment, and comorbidity management.11-16 The initial COPD CARE pilot demonstrated promising results; patients received timely care and high rates of COPD best practices.11

Academy Design and Implementation

Initial COPD CARE training was tailored to the culture, context, and workflow of the William S. Middleton Memorial Veteran’s Hospital in Madison, Wisconsin. Further service expansion required integration of implementation strategies that enable learners to apply and adapt content to fit different processes, staffing, and patient needs.

Formal Implementation Blueprint

A key aspect of the Academy is the integration of a formal implementation blueprint that includes training goals, scope, and key milestones to guide implementation. The Academy blueprint includes 4 phased training workbooks: (1) preimplementation support from local stakeholders; (2) integration of COPD CARE operational infrastructure into workflows; (3) preparing clinical champions; and (4) leading clinical training (Figure 1). Five weekly 1-hour synchronous virtual discussions are used for learning the workbook content that include learning objectives and opportunities to strategize how to overcome implementation barriers.

Promoting and Facilitating Implementation

As clinicians apply content from the Academy to install informatics tools, coordinate clinical training, and build relationships across service lines, implementation barriers may occur. A learning collaborative allows peer-mentorship and shared problem solving. The Academy learning collaborative includes attendees across multiple VAMCs, allowing for diverse perspectives and cross-site learning. Within the field of dissemination and implementation science, this process of shared problem-solving to support individuals is referred to as implementation facilitation.17 Academy facilitators with prior experience provide a unique perspective and external facilitation from outside local VAMCs. Academy learners form local teams to engage in shared decision-making when applying Academy content. Following Academy completion, learning collaboratives continue to meet monthly to share clinical insights and operational updates.

Local Champions Promote Adaptability

One or more local champions were identified at each VAMC who were focused on the implementation of clinical training content and operational implementation of Academy content.18 Champions have helped develop adaptations of Academy content, such as integrating telehealth nursing within the COPD CARE referral process, which have become new best practices. Champions attend Academy sessions, which provide an opportunity to share adaptations to meet local needs.19

Using a Train-The-Trainer Model

Clinical training was designed to be dynamic and included video modeling, such as recorded examples of CPPs conducting COPD CARE visits and video clips highlighting clinical content. Each learner received a clinical workbook summarizing the content. The champion shares discussion questions to relate training content to the local clinical practice setting. The combination of live training, with videos of clinic visits and case-based discussion was intended to address differing learning styles. Clinical training was delivered using a train-the-trainer model led by the local champion, which allows clinicians with expertise to tailor their training. The use of a train-the-trainer model was intended to promote local buy-in and was often completed by frontline clinicians.

Informatics note templates provide clinicians with information needed to deliver training content during clinic visits. Direct hyperlinks to symptomatic scoring tools, resources to promote evidence-based medication optimization, and patient education resources were embedded within the electronic health record note templates. Direct links to consults for COPD referrals services discussed during clinical training were also included to promote ease of care coordination and awareness of referral opportunities. The integration of clinical training with informatics note template support was intentional to directly relate clinical training to clinical care delivery.

Audit and Feedback

To inform COPD CARE practice, the Academy included informatics infrastructure that allowed for timely local quality monitoring. Electronic health record note templates with embedded data fields track COPD CARE service implementation, including timely completion of patient visits, completion of patient medication reviews, appropriate testing, symptom assessment, and interventions made. Champions can organize template installation and integrate templates into COPD CARE clinical training. Data are included on a COPD CARE implementation dashboard.

An audit and feedback process is allows for the review of performance metrics and development of action plans.20,21 Data reports from note templates are described during the Academy, along with resources to help teams enhance delivery of their program based on performance metrics.

Building a Coalition

Within VA primary care, clinical care delivery is optimized through a team-based coalition of clinicians using the patient aligned care team (PACT) framework. The VA patient-centered team-based care delivery model, patient facilitates coordination of patient referrals, including patient review, scheduling, and completion of patient visits.22

Partnerships with VA Pharmacy Benefits Manager, VA Diffusion of Excellence, VA Quality Enhancement Research Initiative, VA Office of Pulmonary Medicine, and the VA Office of Rural Health have facilitated COPD CARE successes. Collaborations with VA Centers of Innovation helped benchmark the Academy’s impact. An academic partnership with the University of Wisconsin-Madison was established in 2017 and has provided evaluation expertise and leadership as the Academy has been iteratively developed, and revised.

Preliminary Metrics

COPD CARE has delivered > 2000 visits. CPPs have delivered COPD care, with a mean 9.4 of 10 best practices per patient visit. Improvements in veteran COPD symptoms have also been observed following COPD CARE patient visits.

DISCUSSION

The COPD CARE Academy was developed to promote rapid scale-up of a complex, team-based COPD service delivered during veteran care transitions. The implementation blueprint for the Academy is multifaceted and integrates both clinical-focused and implementation-focused infrastructure to apply training content.23 A randomized control trial evaluating the efficacy of training modalities found a need to expand implementation blueprints beyond clinical training alone, as training by itself may not be sufficient to change behavior.24 VA staff designed the Academy using clinical- and implementation-focused content within its implementation blueprint. Key components included leveraging clinical champions, using a train-the-trainer approach, and incorporating facilitation strategies to overcome adoption barriers.

Lewis et al emphasize matching implementation strategies to barriers within VA staff who identify care coordination as a key challenge.23 The informatics infrastructure developed for Academy learners, including standardized note templates, video modeling examples of clinic visits, and data capture for audit and feedback, was designed to complement clinical training and standardize service workflows (Figure 2). There are opportunities to explore how to optimize technology in the Academy.

While Academy clinical training specifically focuses on COPD management, many implementation strategies can be considered to promote care delivery services for other chronic conditions. The Academy blueprint and implementation infrastructure, are strategies that may be considered within and outside the federal health care system. The opportunity for adaptations to Academy training enables clinical champions to promote tailored content to the needs of each unique VAMC. The translation of Academy implementation strategies for new chronic conditions will similarly require adaptations at each VAMC to promote adoption of content.

CONCLUSIONS

COPD CARE Academy is an example of the collaborative spirit within VA, and the opportunity for further advancement of health care programs. The VA is a national leader in Learning Health Systems implementation, in which “science, informatics, incentives and culture are aligned for continuous improvement and innovation.”25,26 There are many opportunities for VA staff to learn from one another to form partnerships between leaders, clinicians, and scientists to optimize health care delivery and further the VA’s work as a learning health system.

Quality improvement (QI) initiatives within the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) play an important role in enhancing health care for veterans.1,2 While effective QI programs are often developed, veterans benefit only if they receive care at sites where the program is offered.3 It is estimated only 1% to 5% of patients receive benefit from evidence-based programs, limiting the opportunity for widespread impact.4,5

The Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) Coordinated Access to Reduce Exacerbations (CARE) Academy is a national training program designed to promote the adoption of a COPD primary care service.6 The Academy was created and iteratively refined by VA staff to include both clinical training emphasizing COPD management and program implementation strategies. Training programs such as COPD CARE are commonly described as a method to support adoption of health care services, but there is no consensus on a universal approach to training design.

This article describes COPD CARE training and implementation strategies (Table). The Academy began as a training program at 1 VA medical center (VAMC) and has expanded to 49 diverse VAMCs. The Academy illustrates how implementation strategies can be leveraged to develop pragmatic and impactful training. Highlights from the Academy's 9-year history are outlined in this article.

COPD CARE

One in 4 veterans have a COPD diagnosis, and the 5-year mortality rate following a COPD flare is ≥ 50%.7,8 In 2015, a pharmacy resident designed and piloted COPD CARE, a program that used evidence-based practice to optimize management of the disease.9,10

The COPD CARE program is delivered by interprofessional team members. It includes a postacute care call completed 48 hours postdischarge, a wellness visit (face-to-face or virtual) 1 month postdischarge, and a follow-up visit scheduled 2 months postdischarge. Clinical pharmacist practitioners (CPPs) prescribe and collaborate with the COPD CARE health care team. Evidence-based practices embedded within COPD CARE include treatment optimization, symptom evaluation, severity staging, vaccination promotion, referrals, tobacco treatment, and comorbidity management.11-16 The initial COPD CARE pilot demonstrated promising results; patients received timely care and high rates of COPD best practices.11

Academy Design and Implementation

Initial COPD CARE training was tailored to the culture, context, and workflow of the William S. Middleton Memorial Veteran’s Hospital in Madison, Wisconsin. Further service expansion required integration of implementation strategies that enable learners to apply and adapt content to fit different processes, staffing, and patient needs.

Formal Implementation Blueprint

A key aspect of the Academy is the integration of a formal implementation blueprint that includes training goals, scope, and key milestones to guide implementation. The Academy blueprint includes 4 phased training workbooks: (1) preimplementation support from local stakeholders; (2) integration of COPD CARE operational infrastructure into workflows; (3) preparing clinical champions; and (4) leading clinical training (Figure 1). Five weekly 1-hour synchronous virtual discussions are used for learning the workbook content that include learning objectives and opportunities to strategize how to overcome implementation barriers.

Promoting and Facilitating Implementation

As clinicians apply content from the Academy to install informatics tools, coordinate clinical training, and build relationships across service lines, implementation barriers may occur. A learning collaborative allows peer-mentorship and shared problem solving. The Academy learning collaborative includes attendees across multiple VAMCs, allowing for diverse perspectives and cross-site learning. Within the field of dissemination and implementation science, this process of shared problem-solving to support individuals is referred to as implementation facilitation.17 Academy facilitators with prior experience provide a unique perspective and external facilitation from outside local VAMCs. Academy learners form local teams to engage in shared decision-making when applying Academy content. Following Academy completion, learning collaboratives continue to meet monthly to share clinical insights and operational updates.

Local Champions Promote Adaptability

One or more local champions were identified at each VAMC who were focused on the implementation of clinical training content and operational implementation of Academy content.18 Champions have helped develop adaptations of Academy content, such as integrating telehealth nursing within the COPD CARE referral process, which have become new best practices. Champions attend Academy sessions, which provide an opportunity to share adaptations to meet local needs.19

Using a Train-The-Trainer Model

Clinical training was designed to be dynamic and included video modeling, such as recorded examples of CPPs conducting COPD CARE visits and video clips highlighting clinical content. Each learner received a clinical workbook summarizing the content. The champion shares discussion questions to relate training content to the local clinical practice setting. The combination of live training, with videos of clinic visits and case-based discussion was intended to address differing learning styles. Clinical training was delivered using a train-the-trainer model led by the local champion, which allows clinicians with expertise to tailor their training. The use of a train-the-trainer model was intended to promote local buy-in and was often completed by frontline clinicians.

Informatics note templates provide clinicians with information needed to deliver training content during clinic visits. Direct hyperlinks to symptomatic scoring tools, resources to promote evidence-based medication optimization, and patient education resources were embedded within the electronic health record note templates. Direct links to consults for COPD referrals services discussed during clinical training were also included to promote ease of care coordination and awareness of referral opportunities. The integration of clinical training with informatics note template support was intentional to directly relate clinical training to clinical care delivery.

Audit and Feedback

To inform COPD CARE practice, the Academy included informatics infrastructure that allowed for timely local quality monitoring. Electronic health record note templates with embedded data fields track COPD CARE service implementation, including timely completion of patient visits, completion of patient medication reviews, appropriate testing, symptom assessment, and interventions made. Champions can organize template installation and integrate templates into COPD CARE clinical training. Data are included on a COPD CARE implementation dashboard.

An audit and feedback process is allows for the review of performance metrics and development of action plans.20,21 Data reports from note templates are described during the Academy, along with resources to help teams enhance delivery of their program based on performance metrics.

Building a Coalition

Within VA primary care, clinical care delivery is optimized through a team-based coalition of clinicians using the patient aligned care team (PACT) framework. The VA patient-centered team-based care delivery model, patient facilitates coordination of patient referrals, including patient review, scheduling, and completion of patient visits.22

Partnerships with VA Pharmacy Benefits Manager, VA Diffusion of Excellence, VA Quality Enhancement Research Initiative, VA Office of Pulmonary Medicine, and the VA Office of Rural Health have facilitated COPD CARE successes. Collaborations with VA Centers of Innovation helped benchmark the Academy’s impact. An academic partnership with the University of Wisconsin-Madison was established in 2017 and has provided evaluation expertise and leadership as the Academy has been iteratively developed, and revised.

Preliminary Metrics

COPD CARE has delivered > 2000 visits. CPPs have delivered COPD care, with a mean 9.4 of 10 best practices per patient visit. Improvements in veteran COPD symptoms have also been observed following COPD CARE patient visits.

DISCUSSION

The COPD CARE Academy was developed to promote rapid scale-up of a complex, team-based COPD service delivered during veteran care transitions. The implementation blueprint for the Academy is multifaceted and integrates both clinical-focused and implementation-focused infrastructure to apply training content.23 A randomized control trial evaluating the efficacy of training modalities found a need to expand implementation blueprints beyond clinical training alone, as training by itself may not be sufficient to change behavior.24 VA staff designed the Academy using clinical- and implementation-focused content within its implementation blueprint. Key components included leveraging clinical champions, using a train-the-trainer approach, and incorporating facilitation strategies to overcome adoption barriers.

Lewis et al emphasize matching implementation strategies to barriers within VA staff who identify care coordination as a key challenge.23 The informatics infrastructure developed for Academy learners, including standardized note templates, video modeling examples of clinic visits, and data capture for audit and feedback, was designed to complement clinical training and standardize service workflows (Figure 2). There are opportunities to explore how to optimize technology in the Academy.

While Academy clinical training specifically focuses on COPD management, many implementation strategies can be considered to promote care delivery services for other chronic conditions. The Academy blueprint and implementation infrastructure, are strategies that may be considered within and outside the federal health care system. The opportunity for adaptations to Academy training enables clinical champions to promote tailored content to the needs of each unique VAMC. The translation of Academy implementation strategies for new chronic conditions will similarly require adaptations at each VAMC to promote adoption of content.

CONCLUSIONS

COPD CARE Academy is an example of the collaborative spirit within VA, and the opportunity for further advancement of health care programs. The VA is a national leader in Learning Health Systems implementation, in which “science, informatics, incentives and culture are aligned for continuous improvement and innovation.”25,26 There are many opportunities for VA staff to learn from one another to form partnerships between leaders, clinicians, and scientists to optimize health care delivery and further the VA’s work as a learning health system.

- Robinson CH, Thompto AJ, Lima EN, Damschroder LJ. Continuous quality improvement at the frontline: one interdisciplinary clinical team's four-year journey after completing a virtual learning program. Learn Health Syst. 2022;6(4):e10345. doi:10.1002/lrh2.10345

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Continuous quality improvement (CQI) for clinical teams: a systematic review of reviews. Accessed July 24, 2025. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/cyber_seminars/archives/video_archive.cfm?SessionID=4151

- Dondanville KA, Fina BA, Straud CL, et al. Launching a competency-based training program in evidence-based treatments for PTSD: supporting veteran-serving mental health providers in Texas. Community Ment Health J. 2021;57(5):910-919. doi:10.1007/S10597-020-00676-7

- Abildso CG, Zizzi SJ, Reger-Nash B. Evaluating an insurance- sponsored weight management program with the RE-AIM model, West Virginia, 2004-2008. Prev Chronic Dis. 2010;7(3):A46.

- Glasgow RE, Vinson C, Chambers D, Khoury MJ, Kaplan RM, Hunter C. National institutes of health approaches to dissemination and implementation science: current and future directions. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(7):1274- 1281. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.300755

- Portillo EC, Maurer MA, Kettner JT, et al. Applying RE-AIM to examine the impact of an implementation facilitation package to scale up a program for veterans with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Implement Sci Commun. 2023;4(1):143. doi:10.1186/S43058-023-00520-5

- McGhan R, Radcliff T, Fish R, Sutherland ER, Welsh C, Make B. Predictors of rehospitalization and death after a severe exacerbation of COPD. Chest. 2007;132(6):1748- 1755. doi:10.1378/chest.06-3018

- Anderson E, Wiener RS, Resnick K, Elwy AR, Rinne ST. Care coordination for veterans with COPD: a positive deviance study. Am J Manag Care. 2020;26(2):63-68. doi:10.37765/AJMC.2020.42394

- 2024 GOLD Report. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease - GOLD. Accessed July 24, 2025. https://goldcopd.org/2024-gold-report/

- Nici L, Mammen MJ, Charbek E, et al. Pharmacologic management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(9):e56-e69. doi:10.1164/rccm.202003-0625ST

- Portillo EC, Wilcox A, Seckel E, et al. Reducing COPD readmission rates: using a COPD care service during care transitions. Fed Pract. 2018;35(11):30-36.

- Portillo EC, Gruber S, Lehmann M, et al. Application of the replicating effective programs framework to design a COPD training program. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2021;61(2):e129-e135. doi:10.1016/J.JAPH.2020.10.023

- Portillo EC, Lehmann MR, Hagen TL, et al. Integration of the patient-centered medical home to deliver a care bundle for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease management. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2023;63(1):212-219. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2022.10.003

- Portillo E, Lehmann M, Hagen T, et al. Evaluation of an implementation package to deliver the COPD CARE service. BMJ Open Qual. 2023;12(1). doi:10.1136/BMJOQ-2022-002074

- Portillo E, Lehmann M, Maurer M, et al. Barriers to implementing a pharmacist-led COPD care bundle in rural settings: A qualitative evaluation. 2025 (under review).

- Population Health Management. American Hospital Association. Accessed July 24, 2025. https://www.aha.org/center/population-health-management

- Ritchie MJ, Dollar KM, Miller CK, et al. Using implementation facilitation to improve healthcare: implementation facilitation training manual. Accessed July 11, 2024. https:// www.queri.research.va.gov/tools/Facilitation-Manual.pdf

- Morena AL, Gaias LM, Larkin C. Understanding the role of clinical champions and their impact on clinician behavior change: the need for causal pathway mechanisms. Front Health Serv. 2022;2:896885. doi:10.3389/FRHS.2022.896885

- Ayele RA, Rabin BA, McCreight M, Battaglia C. Editorial: understanding, assessing, and guiding adaptations in public health and health systems interventions: current and future directions. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1228437. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2023.1228437

- Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, Ivers N. Audit and feedback as a quality strategy. In: Improving Healthcare Services. World Health Organization; 2019. Accessed July 24, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549284/

- Snider MDH, Boyd MR, Walker MR, Powell BJ, Lewis CC. Using audit and feedback to guide tailored implementations of measurement-based care in community mental health: a multiple case study. Implement Sci Commun. 2023;4(1):94. doi:10.1186/s43058-023-00474-8

- Patient Aligned Care Team (PACT) – Patient Care Services. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Accessed July 24, 2025. https://www.patientcare.va.gov/primarycare/PACT.asp

- Lewis CC, Scott K, Marriott BR. A methodology for generating a tailored implementation blueprint: an exemplar from a youth residential setting. Implementat Sci. 2018;13(1):68. doi:10.1186/s13012-018-0761-6

- Beidas RS, Edmunds JM, Marcus SC, Kendall PC. Training and consultation to promote implementation of an empirically supported treatment: a randomized trial. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(7):660-665. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201100401

- Kilbourne AM, Schmidt J, Edmunds M, Vega R, Bowersox N, Atkins D. How the VA is training the next-generation workforce for learning health systems. Learn Health Syst. 2022;6(4):e10333. doi:10.1002/LRH2.10333

- Easterling D, Perry AC, Woodside R, Patel T, Gesell SB. Clarifying the concept of a learning health system for healthcare delivery organizations: implications from a qualitative analysis of the scientific literature. Learn Health Syst. 2021;6(2):e10287. doi:10.1002/LRH2.10287

- Robinson CH, Thompto AJ, Lima EN, Damschroder LJ. Continuous quality improvement at the frontline: one interdisciplinary clinical team's four-year journey after completing a virtual learning program. Learn Health Syst. 2022;6(4):e10345. doi:10.1002/lrh2.10345

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Continuous quality improvement (CQI) for clinical teams: a systematic review of reviews. Accessed July 24, 2025. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/cyber_seminars/archives/video_archive.cfm?SessionID=4151

- Dondanville KA, Fina BA, Straud CL, et al. Launching a competency-based training program in evidence-based treatments for PTSD: supporting veteran-serving mental health providers in Texas. Community Ment Health J. 2021;57(5):910-919. doi:10.1007/S10597-020-00676-7

- Abildso CG, Zizzi SJ, Reger-Nash B. Evaluating an insurance- sponsored weight management program with the RE-AIM model, West Virginia, 2004-2008. Prev Chronic Dis. 2010;7(3):A46.

- Glasgow RE, Vinson C, Chambers D, Khoury MJ, Kaplan RM, Hunter C. National institutes of health approaches to dissemination and implementation science: current and future directions. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(7):1274- 1281. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.300755

- Portillo EC, Maurer MA, Kettner JT, et al. Applying RE-AIM to examine the impact of an implementation facilitation package to scale up a program for veterans with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Implement Sci Commun. 2023;4(1):143. doi:10.1186/S43058-023-00520-5

- McGhan R, Radcliff T, Fish R, Sutherland ER, Welsh C, Make B. Predictors of rehospitalization and death after a severe exacerbation of COPD. Chest. 2007;132(6):1748- 1755. doi:10.1378/chest.06-3018

- Anderson E, Wiener RS, Resnick K, Elwy AR, Rinne ST. Care coordination for veterans with COPD: a positive deviance study. Am J Manag Care. 2020;26(2):63-68. doi:10.37765/AJMC.2020.42394

- 2024 GOLD Report. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease - GOLD. Accessed July 24, 2025. https://goldcopd.org/2024-gold-report/

- Nici L, Mammen MJ, Charbek E, et al. Pharmacologic management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(9):e56-e69. doi:10.1164/rccm.202003-0625ST

- Portillo EC, Wilcox A, Seckel E, et al. Reducing COPD readmission rates: using a COPD care service during care transitions. Fed Pract. 2018;35(11):30-36.

- Portillo EC, Gruber S, Lehmann M, et al. Application of the replicating effective programs framework to design a COPD training program. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2021;61(2):e129-e135. doi:10.1016/J.JAPH.2020.10.023

- Portillo EC, Lehmann MR, Hagen TL, et al. Integration of the patient-centered medical home to deliver a care bundle for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease management. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2023;63(1):212-219. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2022.10.003

- Portillo E, Lehmann M, Hagen T, et al. Evaluation of an implementation package to deliver the COPD CARE service. BMJ Open Qual. 2023;12(1). doi:10.1136/BMJOQ-2022-002074

- Portillo E, Lehmann M, Maurer M, et al. Barriers to implementing a pharmacist-led COPD care bundle in rural settings: A qualitative evaluation. 2025 (under review).

- Population Health Management. American Hospital Association. Accessed July 24, 2025. https://www.aha.org/center/population-health-management

- Ritchie MJ, Dollar KM, Miller CK, et al. Using implementation facilitation to improve healthcare: implementation facilitation training manual. Accessed July 11, 2024. https:// www.queri.research.va.gov/tools/Facilitation-Manual.pdf

- Morena AL, Gaias LM, Larkin C. Understanding the role of clinical champions and their impact on clinician behavior change: the need for causal pathway mechanisms. Front Health Serv. 2022;2:896885. doi:10.3389/FRHS.2022.896885

- Ayele RA, Rabin BA, McCreight M, Battaglia C. Editorial: understanding, assessing, and guiding adaptations in public health and health systems interventions: current and future directions. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1228437. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2023.1228437

- Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, Ivers N. Audit and feedback as a quality strategy. In: Improving Healthcare Services. World Health Organization; 2019. Accessed July 24, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549284/

- Snider MDH, Boyd MR, Walker MR, Powell BJ, Lewis CC. Using audit and feedback to guide tailored implementations of measurement-based care in community mental health: a multiple case study. Implement Sci Commun. 2023;4(1):94. doi:10.1186/s43058-023-00474-8

- Patient Aligned Care Team (PACT) – Patient Care Services. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Accessed July 24, 2025. https://www.patientcare.va.gov/primarycare/PACT.asp

- Lewis CC, Scott K, Marriott BR. A methodology for generating a tailored implementation blueprint: an exemplar from a youth residential setting. Implementat Sci. 2018;13(1):68. doi:10.1186/s13012-018-0761-6

- Beidas RS, Edmunds JM, Marcus SC, Kendall PC. Training and consultation to promote implementation of an empirically supported treatment: a randomized trial. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(7):660-665. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201100401

- Kilbourne AM, Schmidt J, Edmunds M, Vega R, Bowersox N, Atkins D. How the VA is training the next-generation workforce for learning health systems. Learn Health Syst. 2022;6(4):e10333. doi:10.1002/LRH2.10333

- Easterling D, Perry AC, Woodside R, Patel T, Gesell SB. Clarifying the concept of a learning health system for healthcare delivery organizations: implications from a qualitative analysis of the scientific literature. Learn Health Syst. 2021;6(2):e10287. doi:10.1002/LRH2.10287

COPD CARE Academy: Design of Purposeful Training Guided by Implementation Strategies

COPD CARE Academy: Design of Purposeful Training Guided by Implementation Strategies

Reducing COPD Readmission Rates: Using a COPD Care Service During Care Transitions

A chronic obstructive pulmonary disease care service improves timely access to follow-up care and patient education at the time of transition from hospital to home.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the third leading cause of death worldwide and has an associated treatment cost of $9,800 per patient per year in the US.1-3 Within 5 years of hospital discharge for a COPD exacerbation, the rehospitalization risk is 44%, and the mortality rate is 55%.4 COPD affects more than 11 million Americans, and the disease prevalence among US veterans is 3-fold higher.5,6

Patients hospitalized for COPD have a 30-day readmission rate of 22.6%.7 Given the high patient burden, COPD was added to the Medicare Hospital Readmission Reductions Program in 2015, resulting in financial penalties for COPD readmissions within 30 days of hospital discharge.8 Ensuring timely access to follow-up care has been shown to significantly reduce risk for hospital readmissions.9 However, in a national review of Medicare claims, only 50% of patients readmitted to the hospital had a primary care provider (PCP) follow-up visit within 30 days of their hospital discharge.10 Despite the need to provide prompt patient follow-up during the transition from hospital to home, gaps within the health care system create barriers to providing timely postdischarge care.10-12 These gaps include breakdowns in practitioner and patient communication, lengthy time to follow-up, and incomplete medication reconciliation.13 To address this unmet need, clinics and hospitals require solutions that can be implemented quickly, using the resources of their current clinical models.

Pharmacists and registered nurses (RNs) within the US federal health care system are well positioned for involvement in the postdischarge care of high-risk patients with COPD. Ambulatory care practitioners within the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system are integrated into patient aligned care teams (PACT). Each team consists of a PCP, pharmacist, RN, social worker, dietitian, licensed practical nurse, and medical scheduling support assistant.14 Each PACT team works together to provide patient education, chronic disease management, and medication optimization, and each team member contributes their unique training and expertise.

Interprofessional care is considered an integral method to improve health outcomes through effective teamwork and communication.15 Although interprofessional interventions are cited extensively in the literature highlighting medicine and nursing, a gap exists in the exploration of pharmacist contributions within interprofessional teams.16 The incorporation of clinical pharmacists in the literature is especially limited when considering transitions of care and the patient medical home.17 Given the critical and collaborative role pharmacists play within the PACT medical home, the COPD CARE (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Coordinated Access to Reduce Exacerbations) service provides an opportunity to leverage pharmacists as prescribers with a scope of practice who coordinate transitions of care for patients with COPD.18 The service was designed to be collaborative within the PACT model and with the intent of reducing 30-day readmissions to the hospital or emergency department (ED) due to a COPD exacerbation.

This evaluation involved the identifying patients recently hospitalized for COPD; clinic follow-up, coordinated by a clinical pharmacist and nurse, within 30 days of hospital or ED discharge; the use of a COPD action plan; and timely triage of patients at high risk for COPD reexacerbation or with comorbid symptoms to PCPs. The COPD CARE service, leveraged the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model for transitions of care after COPD exacerbations. The PCMH is a primary care model focused on the following functions: (1) comprehensive care; (2) patient-centered care; (3) coordinated care; (4) accessible service; and (5) quality and safety.19

Methods

The COPD CARE service was implemented on October 1, 2015, and evaluated through March 1, 2016 (Figure 1). All veterans receiving primary care through the pilot clinic site with a hospital admission or ED visit for COPD exacerbation were offered this intervention.

Patient Eligibility and Recruitment

Patients were excluded from the service if COPD or COPD-related diagnoses were not listed in their electronic health record (EHR) problem list. Patients who had previously received components of the intervention through consultation with specialty services were excluded. If a patient declined the service, they received the standard of care. This project was undertaken for programmatic evaluation and qualified for quality improvement (QI) exemption; as such an internal review board approval was not required.

Intervention

Participants enrolled in the COPD CARE service were scheduled for an interprofessional postdischarge follow-up visit with a pharmacist and nurse at the pilot outpatient clinic site, and this visit was termed the COPD CARE health visit. Participants ideally were seen within 30 days of discharge. The goal was to improve access to care while preventing a 30-day readmission. Within this 30-day window, the target follow-up period was 2 to 3 weeks postdischarge for the face-to-face visit. Patients who required postdischarge care for additional medical conditions received a clinic appointment with their PCP on the same day as their COPD CARE health visit. The COPD CARE health visit focused on 3 objectives: (1) COPD disease management and referrals; (2) COPD plan development; and (3) inhaler technique review and teaching.20,21

COPD Monitoring

During the 45-minute COPD CARE health visit, the pharmacist provided extensive disease management based on the GOLD guideline recommendation.22 In addition, the pharmacist administered the COPD Assessment Test (CAT) and reviewed patient COPD exacerbation history to guide prescribing.22 The patient and pharmacist also reviewed previous spirometry results if obtained within the past 2 years. COPD triggers and symptoms were assessed along with opportunities for therapeutic and lifestyle modifications.

Plan Development

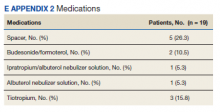

Patients in the COPD CARE service also were given a COPD plan to improve health outcomes. (Figure 2). The plan included patient instructions to initiate steroid and antibiotic therapy if the patient experienced symptoms of increased cough, mucus production, and purulence, thereby reaching the high-yellow zone.

Patient Referrals

Patient referrals also were a critical component of the COPD CARE service. Pharmacists placed referrals for tobacco treatment services, pulmonary rehabilitation, a COPD group education class, and referral to specialty care if needed.

Inhaler Technique Review

Either the pharmacist or RN review the inhaler technique, and corrections and teachback methods used to ensure patient understanding.23 Patients were encouraged to bring home inhalers into clinic for technique assessment. Demonstration inhalers also were available and used by pharmacists and nurses for inhaler teaching as needed. The pharmacist indicated through chart documentation whether the patient’s inhaler technique was correct or whether modifications were made to improve medication delivery. Medication reconciliation also was performed for inhaled devices to insure patients were using medications as prescribed.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of this evaluation was an assessment of interventions made by the interprofessional care team during the COPD CARE health visit. Secondary outcomes included assessment of 30-day readmission rates as well as patient access to the primary care team using this interprofessional care model.

Data were collected after study completion through review of the EHR at baseline and at the end of the evaluation period. Baseline demographic information was collected through a retrospective chart review. Readmission rates were calculated as a composite of ED visits and rehospitalization within 30 days of discharge due to a COPD exacerbation.

Patients’ spirometry results were used in composite with clinical symptoms and risk of exacerbations to calculate GOLD staging.24

Results

A total of 19 patients admitted to the hospital or ED received follow-up through the COPD CARE service. Patients included in this analysis were primarily older adult white males.

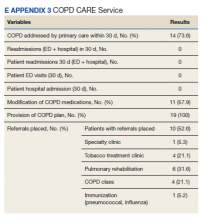

Referrals were placed for 53% of patients in the COPD CARE service, with 21% of patients accepting referral to tobacco treatment clinic, and 32% of patients accepting referral to pulmonary rehabilitation. COPD plans were issued to all of patients in this service. Pharmacists modified therapy 58% of the time, with a review of medications prescribed by the clinical pharmacist (eApendixes 1 and 2, available at mdedge.com/fedprac).

Patients had a 0% composite readmission rate to the ED or hospital for a COPD exacerbation within 30-days of discharge. Access to care, defined as a visit with the primary care PACT team within 30 days of discharge, was achieved in 14 of the 19 patients (73.7%). Additionally, 12 of 19 patients (63.2%) in the COPD CARE service no longer needed to see their PCP following discharge, saving their provider a visit.

The pharmacist corrected patient inhaler technique in 52.6% of the patients participating in the service.

Discussion

The intent of this QI initiative was to assess a novel clinic intervention for a high-risk patient population during COPD care transitions. The strengths of this intervention involved a rapid cycle implementation using the existing medical home model and its multiprong approach to coordinating care. This approach involved coordinating self-direction COPD plans, timely hospital follow-up, and the innovative use of the interprofessional primary care team.

The COPD CARE service improved patient access to follow-up with no COPD readmissions in the intervention group. The COPD CARE service also validated the use of a coordinated medical home consisting of clinical pharmacists and nurses who provided the initial COPD disease monitoring and plan development. This intervention also resulted in patients receiving greater access to their PACT teams within 30 days of discharge and a higher rate of referrals to tobacco cessation clinics within the COPD CARE group. In addition, use of tools that enabled patients to self-manage their care, such as the COPD plan, was greater in the COPD CARE group.

The interventions made in-clinic likely contributed to service results (eAppendix 3).

In addition, the COPD CARE service provided necessary referrals to pulmonary rehabilitation, nutrition, and tobacco treatment clinics at a higher rate than those patients in the standard of care group. The high percentage of referrals placed to tobacco treatment clinic and pulmonary rehabilitation contributes to improvements in COPD disease control long-term.25

The COPD CARE service may best be described as a model for application of the interprofessional team in clinical practice, with the clinical pharmacist uniquely positioned for chronic disease management in the postacute care setting.26 Previously, literature has documented pharmacists as integral members of the team during patient care transitions. Pharmacist completion of medication reconciliation compared with usual care has shown a 28% relative risk (RR) reduction in ED visits and a 67% RR reduction in adverse drug event-related hospital revisits.27 Findings of the COPD CARE service are consistent with the literature and advance the role of pharmacists within the medical home model as prescribers for disease management.27

The interprofessional, team-based design of the COPD CARE service also is supported by recent recommendations from the COPD Foundation, as detailed in the 2nd National COPD Readmission Summit.28 Use of a proactive, team-based care model is emphasized as a central element to coordinating care transitions, with an expectation of 360 degree accountability by all team members for the patients care both during and after hospitalization. The clearly defined roles of each team member within the COPD CARE service, coupled with the expectation that each team member practices with autonomy and accountability, exemplifies the COPD Foundation vision for enhancing COPD care. In addition, the COPD CARE service uses many of the best practices detailed by the COPD Foundation, including the use of spirometry, referrals to pulmonary rehabilitation, and use of motivational interviewing for tobacco treatment clinic referral.

Limitations

This QI initiative has several limitations. By virtue of the study being designed as a practice improvement intervention with rapid implementation, the existing clinic referral structures were used to offer the service to eligible patients. This standard of care included routine telephone contact by a nurse case manager following hospital discharge. Although all patients in the COPD CARE service received the intervention, 5 patients were not seen within the 30-day window, resulting in an implementation rate of 73%. Of the 5 patients that were not seen, 4 were discharged from the ED. Timely follow-up in primary care clinic from the ED required the use of a time-intensive chart review for referral and subsequent delay in intervention delivery.A streamlined clinic referral process from the ED likely would further improve patient scheduling and result in a greater number of patients who would receive the intervention within 30 days of discharge. Despite this limitation, the COPD CARE service was able to see a large percentage of patients within the 30-day time frame postdischarge.

Future Directions

Although a major objective of this service was to reduce readmissions 30 days postdischarge, it is possible interventions made in clinic may have long-term beneficial effects.25,29 Future research should evaluate the impact of this interprofessional service on long-term disease outcomes, thereby determining whether the promising readmission results are sustained beyond 30 days postdischarge.30 In addition, incorporation of respiratory therapy and inpatient pharmacists during hospital discharge could provide a more effective and sustainable transition from hospital to home before the COPD CARE clinic visit.

Future implementations and evaluations of this COPD CARE service will in turn benefit from a key component of our intervention, which includes the collection of timely CAT scores, spirometry data, and adherence rates for COPD patients.31 Furthermore, the intervention was successfully delivered to a population recently hospitalized or seen in the ED, and therefore, at high risk for future COPD exacerbations. This initiative provides positive proof of a concept QI project using the existing PACT team model to reduce 30-day readmission rates in patients with COPD at high risk for exacerbation. Future efforts will focus on delivering this intervention to patients with mild, moderate, and severe COPD within a wide range of primary clinics.

Conslusion

The COPD CARE service involved the coordinated postdischarge care facilitated by an interprofessional team of clinical pharmacists, nurses and PCPs. The COPD CARE service leveraged an interprofessional team, centered on the PACT medical home, to make clinic interventions resulting in a 0% readmission rate and 63.2% increase in PCP access. The COPD CARE service further demonstrated the impact of coordinated efforts by interprofessional teams to optimize care for COPD management.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Stephanie Gruber, PharmD; Lieneke Hafeman, RN; Molly Obermark, PharmD; Julia Peek, RT; Mark Regan, MD; Chris Roelke, RN; Steve Shoyer, PharmD; John Thielemann, RN; Sandy Tompkins, BS; and Wendi Wenger, RN, for their integral roles in the COPD CARE service.

1. World Health Organization. The top 10 causes of death. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs310/en. Updated May 24, 2018. Accessed May 30, 2018.

2. Ford ES, Murphy LB, Khavjou O, Giles WH, Holt JB, Croft JB. Total and state-specific medical and absenteeism costs of COPD among adults aged > 18 years in the United States for 2010 and projections through 2020. Chest. 2015;147(1):31-45.

3. American Lung Association. Trends in COPD (chronic bronchitis and emphysema): morbidity and mortality. http://www.lung.org/assets/documents/research/copd-trend-report.pdf. Published March 2013. Accessed May 30, 2018.

4. McGhan R, Radcliff T, Fish R, Sutherland ER, Welsh C, Make B. Predictors of rehospitalization and death after a severe exacerbation of COPD. Chest. 2007;132(6):1748-1755.

5. COPD Foundation. Patient groups back bill supporting US veterans with COPD. https://www.copdfoundation.org/About-Us/Press-Room/Press-Releases/Article/722/Patient-Groups-Back-Bill-Supporting-US-Veterans-with-COPD.aspx. Published November 9, 2010. Accessed May 30, 2018.

6. American Lung Association. Lung health and disease: how serious is COPD. http://www.lung.org/lung-health-and-diseases/lung-disease-lookup/copd/learn-about-copd/how-serious-is-copd.html. Published 2016. Accessed May 30, 2018.

7. Shah T, Press V, Huisingh-Scheetz M, White SR. COPD readmissions: addressing COPD in the era of value-based health care. Chest. 2016;150(4):916-926.

8. Mcllvennan CK, Eapen ZJ, Allen LA. Hospital readmissions reduction program. Circulation. 2015;13(20):1796-1803.

9. Jackson C, Shahsahebi M, Wedlake T, DuBard CA. Timeliness of outpatient follow-up: an evidence-based approach for planning after hospital discharge. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(2):115-122.

10. Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1418-1428.

11. Hitch B, Parlier AB, Reed L, Galvin SL, Fagan EB, Wilson CG. Evaluation of a team-based, transition-of-care management service on 30-day readmission rates. N C Med J. 2016;77(2):87-92.

12. Stone J, Hoffman G. Medicare hospital readmissions: issues, policy options. In: Turner PM ed. Medicare: Background, Benefits and Issues. Nova Science Pub Inc; 2011:123-150.

13. Kripalani S, Jackson AT, Schnipper JL, Coleman EA. Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(5):314-323.

14. Rosland A-M, Nelson K, Sun H, et al. The patient-centered medical home in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(7):e263-e272.

15. World Health Organization. Nursing and midwifery. http://www.who.int/hrh/nursing_midwifery/en. Accessed September 18, 2018.

16. Supper I, Catala O, Lustman M, Chemla C, Bourgueil Y, Letrilliart L. Interprofessional collaboration in primary health care: a review of facilitators and barriers perceived by involved actors. J Public Health (Oxf). 2015;37(4):716-727.

17. Melody KT, McCartney E, Sen S, Duenas G. Optimizing care transitions: the role of the community pharmacist. Integr Pharm Res Pract. 2016;5:43-51.

18. Ourth H, Groppi J, Morreale AP, Quicci-Roberts K. Clinical pharmacist prescribing activities in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2016;73(18):1406-1415.

19. US Department of Health and Human Services. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Defining the PCMH. https://pcmh.ahrq.gov/page/defining-pcmh. Accessed May 29, 2018.

20. Kaplan A. The COPD action plan. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55(1):58-59.

21. Turnock AC, Walters EH, Walters JA, Wood-Baker R. Action plans for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(4):CD005074.

22. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (2017 report). http://goldcopd.org/gold-2017-global-strategy-diagnosis-management-prevention-copd. Accessed May 29, 2018.

23. Bonini M, Usmani OS. The importance of inhaler devices in the treatment of COPD. COPD Res Pract. 2015;1:9.

24. Buist AS, Anzueto A, Calverley P, DeGuia TS, Fukuch Y. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 2006.

25. McCarthy B, Casey D, Devane D, Murphy K, Murphy E, Lacasse Y. Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(2):CD003793.

26. ASHP Research and Education Foundation. Pharmacy forecast 2016-2020: strategic planning advice. http://www.ashpfoundation.org/PharmacyForecast2016. Published December 2015. Accessed May 29, 2018.

27. Mekonnen AB, McLachlan AJ, Brien JE. Effectiveness of pharmacist-led medication reconciliation programmes on clinical outcomes at hospital transitions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2016;6(2):e010003.

28. Willard KS, Sullivan JB, Thomashow BM, et al. The 2nd national COPD readmissions summit and beyond: from theory to implementation. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2016;3(4):778-790.

29. Scanlon PD, Connett JE, Waller LA, et al; Lung Health Study Research Group. Smoking cessation and lung function in mild-to-moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The lung health study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(2, pt 1):381-390.

30. Shah T, Press VG, Huisingh-Scheetz M, White SR. COPD readmissions: addressing COPD in the era of value-based health care. Chest. 2016;150(4):916-926.

31. GlaxoSmithKline. COPD Assessment Test (CAT). Castest Online. http://www.catestonline.org/images/UserGuides/CATHCPUser%20guideEn.pdf. Updated October 2016.

A chronic obstructive pulmonary disease care service improves timely access to follow-up care and patient education at the time of transition from hospital to home.

A chronic obstructive pulmonary disease care service improves timely access to follow-up care and patient education at the time of transition from hospital to home.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the third leading cause of death worldwide and has an associated treatment cost of $9,800 per patient per year in the US.1-3 Within 5 years of hospital discharge for a COPD exacerbation, the rehospitalization risk is 44%, and the mortality rate is 55%.4 COPD affects more than 11 million Americans, and the disease prevalence among US veterans is 3-fold higher.5,6

Patients hospitalized for COPD have a 30-day readmission rate of 22.6%.7 Given the high patient burden, COPD was added to the Medicare Hospital Readmission Reductions Program in 2015, resulting in financial penalties for COPD readmissions within 30 days of hospital discharge.8 Ensuring timely access to follow-up care has been shown to significantly reduce risk for hospital readmissions.9 However, in a national review of Medicare claims, only 50% of patients readmitted to the hospital had a primary care provider (PCP) follow-up visit within 30 days of their hospital discharge.10 Despite the need to provide prompt patient follow-up during the transition from hospital to home, gaps within the health care system create barriers to providing timely postdischarge care.10-12 These gaps include breakdowns in practitioner and patient communication, lengthy time to follow-up, and incomplete medication reconciliation.13 To address this unmet need, clinics and hospitals require solutions that can be implemented quickly, using the resources of their current clinical models.

Pharmacists and registered nurses (RNs) within the US federal health care system are well positioned for involvement in the postdischarge care of high-risk patients with COPD. Ambulatory care practitioners within the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system are integrated into patient aligned care teams (PACT). Each team consists of a PCP, pharmacist, RN, social worker, dietitian, licensed practical nurse, and medical scheduling support assistant.14 Each PACT team works together to provide patient education, chronic disease management, and medication optimization, and each team member contributes their unique training and expertise.

Interprofessional care is considered an integral method to improve health outcomes through effective teamwork and communication.15 Although interprofessional interventions are cited extensively in the literature highlighting medicine and nursing, a gap exists in the exploration of pharmacist contributions within interprofessional teams.16 The incorporation of clinical pharmacists in the literature is especially limited when considering transitions of care and the patient medical home.17 Given the critical and collaborative role pharmacists play within the PACT medical home, the COPD CARE (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Coordinated Access to Reduce Exacerbations) service provides an opportunity to leverage pharmacists as prescribers with a scope of practice who coordinate transitions of care for patients with COPD.18 The service was designed to be collaborative within the PACT model and with the intent of reducing 30-day readmissions to the hospital or emergency department (ED) due to a COPD exacerbation.

This evaluation involved the identifying patients recently hospitalized for COPD; clinic follow-up, coordinated by a clinical pharmacist and nurse, within 30 days of hospital or ED discharge; the use of a COPD action plan; and timely triage of patients at high risk for COPD reexacerbation or with comorbid symptoms to PCPs. The COPD CARE service, leveraged the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model for transitions of care after COPD exacerbations. The PCMH is a primary care model focused on the following functions: (1) comprehensive care; (2) patient-centered care; (3) coordinated care; (4) accessible service; and (5) quality and safety.19

Methods

The COPD CARE service was implemented on October 1, 2015, and evaluated through March 1, 2016 (Figure 1). All veterans receiving primary care through the pilot clinic site with a hospital admission or ED visit for COPD exacerbation were offered this intervention.

Patient Eligibility and Recruitment

Patients were excluded from the service if COPD or COPD-related diagnoses were not listed in their electronic health record (EHR) problem list. Patients who had previously received components of the intervention through consultation with specialty services were excluded. If a patient declined the service, they received the standard of care. This project was undertaken for programmatic evaluation and qualified for quality improvement (QI) exemption; as such an internal review board approval was not required.

Intervention

Participants enrolled in the COPD CARE service were scheduled for an interprofessional postdischarge follow-up visit with a pharmacist and nurse at the pilot outpatient clinic site, and this visit was termed the COPD CARE health visit. Participants ideally were seen within 30 days of discharge. The goal was to improve access to care while preventing a 30-day readmission. Within this 30-day window, the target follow-up period was 2 to 3 weeks postdischarge for the face-to-face visit. Patients who required postdischarge care for additional medical conditions received a clinic appointment with their PCP on the same day as their COPD CARE health visit. The COPD CARE health visit focused on 3 objectives: (1) COPD disease management and referrals; (2) COPD plan development; and (3) inhaler technique review and teaching.20,21

COPD Monitoring

During the 45-minute COPD CARE health visit, the pharmacist provided extensive disease management based on the GOLD guideline recommendation.22 In addition, the pharmacist administered the COPD Assessment Test (CAT) and reviewed patient COPD exacerbation history to guide prescribing.22 The patient and pharmacist also reviewed previous spirometry results if obtained within the past 2 years. COPD triggers and symptoms were assessed along with opportunities for therapeutic and lifestyle modifications.

Plan Development

Patients in the COPD CARE service also were given a COPD plan to improve health outcomes. (Figure 2). The plan included patient instructions to initiate steroid and antibiotic therapy if the patient experienced symptoms of increased cough, mucus production, and purulence, thereby reaching the high-yellow zone.

Patient Referrals

Patient referrals also were a critical component of the COPD CARE service. Pharmacists placed referrals for tobacco treatment services, pulmonary rehabilitation, a COPD group education class, and referral to specialty care if needed.

Inhaler Technique Review