User login

Dearth of Hospitalist Investigators in Academic Medicine: A Call to Action

In their report celebrating the increase in the number of hospitalists from a few hundred in the 1990s to more than 50,000 in 2016, Drs Robert Wachter and Lee Goldman also noted the stunted growth of productive hospital medicine research programs, which presents a challenge to academic credibility in hospital medicine.1 Given the substantial increase in the number of hospitalists over the past two decades, we surveyed adult academic hospital medicine groups to quantify the number of hospitalist clinician investigators and identify gaps in resources for researchers. The number of clinician investigators supported at academic medical centers (AMCs) remains disturbingly low despite the rapid growth of our specialty. Some programs also reported a lack of access to fundamental research services. We report selected results from our survey and provide recommendations to support and facilitate the development of clinician investigators in hospital medicine.

DEARTH OF CLINICIAN INVESTIGATORS IN HOSPITAL MEDICINE

We performed a survey of hospital medicine programs at AMCs in the United States through the Hospital Medicine Reengineering Network (HOMERuN), a hospital medicine research collaborative that facilitates and conducts multisite research studies.2 The purpose of this survey was to obtain a profile of adult academic hospital medicine groups. Surveys were distributed via email to directors and/or senior leaders of each hospital medicine group between January and August 2019. In the survey, a clinician investigator was defined as “faculty whose primary nonclinical focus is scientific papers and grant writing.”

We received responses from 43 of the 86 invitees (50%), each of whom represented a unique hospital medicine group; 41 of the representatives responded to the questions concerning available research services. Collectively, these 43 programs represented 2,503 hospitalists. There were 79 clinician investigators reported among all surveyed hospital medicine groups (3.1% of all hospitalists). The median number of clinician investigators per hospital medicine group was 0 (range 0-12) (Appendix Figure 1), and 22 of 43 (51.2%) hospital medicine groups reported having no clinician investigators. Two of the hospital medicine groups, however, reported having 12 clinician investigators at their respective institutions, comprising nearly one third of the total number of clinician investigators reported in the survey.

Many of the programs reported lack of access to resources such as research assistants (56.1%) and dedicated research fellowships (53.7%) (Appendix Figure 2). A number of groups reported a need for more support for various junior faculty development activities, including research mentoring (53.5%), networking with other researchers (60.5%), and access to clinical data from multiple sites (62.8%).

One of the limitations of this survey was the manner in which the participating hospital medicine groups were chosen. Selection was based on groups affiliated with HOMERuN; among those chosen were highly visible US AMCs, including 70% of the top 20 AMCs based on National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding.3 Therefore, our results likely overestimate the research presence of hospital medicine across all AMCs in the United States.

LACK OF GROWTH OVER TIME: CONTEXTUALIZATION AND IMPLICATIONS

Despite the substantial growth of hospital medicine over the past 2 decades, there has been no proportional increase in the number of hospitalist clinician investigators, with earlier surveys also demonstrating low numbers.4,5 Along with the survey by Chopra and colleagues published in 2019,6 our survey provides an additional contemporary appraisal of research activities for adult academic hospital medicine groups. In the survey by Chopra et al, only 54% (15 of 28) of responding programs reported having any faculty with research as their major activity (ie, >50% effort), and 3% of total faculty reported having funding for >50% effort toward research.6 Our study expands upon these findings by providing more detailed data on the number of clinician investigators per hospital medicine group. Results of our survey showed a concentration of hospitalists within a small number of programs, which may have contributed to the observed lack of growth. We also expand on prior work by identifying a lack of resources and services to support hospitalist researchers.

The findings of our survey have important implications for the field of hospital medicine. Without a critical mass of hospitalist clinician investigators, the quality of research that addresses important questions in our field will suffer. It will also limit academic credibility of the field, as well as individual academic achievement; previous studies have consistently demonstrated that few hospitalists at AMCs achieve the rank of associate or full professor.5-9

POTENTIAL EXPLANATIONS FOR LACK OF RESEARCH GROWTH

The results of our study additionally offer possible explanations for the dearth of clinician investigators in hospital medicine. The limited access to research resources and fellowship training identified in our survey are critical domains that must be addressed in order to develop successful academic hospital medicine programs.4,6,8,10

Regarding dedicated hospital medicine research fellowships, there are only a handful across the country. The small number of existing research fellowships only have one or two fellows per year, and these positions often go unfilled because of a lack of applicants and lower salaries compared to full-time clinical positions.11 The lack of applicants for adult hospital medicine fellowship positions is also integrally linked to board certification requirements. Unlike pediatric hospital medicine where additional fellowship training is required to become board-certified, no such fellowship is required in adult hospital medicine. In pediatrics, this requirement has led to a rapid increase in the number of fellowships with scholarly work requirements (more than 60 fellowships, plus additional programs in development) and greater standardization among training experiences.12,13

The lack of fellowship applicants may also stem from the fact that many trainees are not aware of a potential career as a hospitalist clinician investigator due to limited exposure to this career at most AMCs. Our results revealed that nearly half of sites in our survey had zero clinician investigators, depriving trainees at these programs of role models and thus perpetuating a negative feedback loop. Lastly, although unfilled fellowship positions may indicate that demand is a larger problem than supply, it is also true that fellowship programs generate their own demand through recruitment efforts and the gradual establishment of a positive reputation.

Another potential explanation could relate to the development of hospital medicine in response to rising clinical demands at hospitals: compared with other medical specialties, AMCs may regard hospitalists as being clinicians first and academicians second.1,7,10 Also, hospitalists may be perceived as being beholden to hospitals and less engaged with their surrounding communities than other general medicine fields. With a small footprint in health equity research, academic hospital medicine may be less of a draw to generalists interested in pursuing this area of research. Further, there are very few underrepresented in medicine (URiM) hospital medicine research faculty.5

Another challenge to the career development of hospitalist researchers is the lack of available funding for the type of research typically conducted by hospitalists (eg, rigorous quality improvement implementation and evaluation, optimizing best evidence-based care delivery models, evaluation of patient safety in the hospital setting). As hospitalists tend to be system-level thinkers, this lack of funding may steer potential researchers away from externally funded research careers and into hospital operations and quality improvement positions. Also, unlike other medical specialties, there is no dedicated NIH funding source for hospital medicine research (eg, cardiology and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute), placing hospitalists at a disadvantage in seeking funding compared to subspecialists.

STRATEGIES TO ENHANCE RESEARCH PRESENCE

We recommend several approaches—ones that should be pursued simultaneously—to increase the number of clinician investigators in hospital medicine. First, hospital medicine groups and their respective divisions, departments, and hospitals should allocate funding to support research resources; this includes investing in research assistants, data analysts, statisticians, and administrative support. Through the funding of such research infrastructure programs, AMCs could incentivize hospitalists to research best approaches to improve the value of healthcare delivery, ultimately leading to cost savings.

With 60% of respondents identifying the need for improved access to data across multiple sites, our survey also emphasizes the requirement for further collaboration among hospital medicine groups. Such collaboration could lead to high-powered observational studies and the evaluation of interventions across multiple sites, thus improving the generalizability of study findings.

The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) and its research committee can continue to expand the research footprint of hospital medicine. To date, the committee has achieved this by highlighting hospitalist research activity at the SHM Annual Conference Scientific Abstract and Poster Competition and developing a visiting professorship exchange program. In addition to these efforts, SHM could foster collaboration and networking between institutions, as well as take advantage of the current political push for expanded Medicare access by lobbying for robust funding for the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, which could provide more opportunities for hospitalists to study the effects of healthcare policy reform on the delivery of inpatient care.

Another strategy to increase the number of hospitalist clinician investigators is to expand hospital medicine research fellowships and recruit trainees for these programs. Fellowships could be internally funded wherein a fellow’s clinical productivity is used to offset the costs associated with obtaining advanced degrees. As an incentive to encourage applicants to temporarily forego a full-time clinical salary during fellowship, hospital medicine groups could offer expanded moonlighting opportunities and contribute to repayment of medical school loans. Hospital medicine groups should also advocate for NIH-funded T32 or K12 training grants for hospital medicine. (There are, however, challenges with this approach because the number of T32 spots per NIH institute is usually fixed). The success of academic emergency medicine offers a precedent for such efforts: After the development of a K12 research training program in emergency medicine, the number of NIH-sponsored principal investigators in this specialty increased by 40% in 6 years.14 Additionally, now that fellowships are required for the pediatric hospital medicine clinician investigators, it would be revealing to track the growth of this workforce.12,13

Structured and formalized mentorship is an essential part of the development of clinician investigators in hospital medicine.4,7,8,10 One successful strategy for mentorship has been the partnering of hospital medicine groups with faculty of general internal medicine and other subspecialty divisions with robust research programs.7,8,15 In addition to developing sustainable mentorship programs, hospital medicine researchers must increase their visibility to trainees. Therefore, it is essential that the majority of academic hospital medicine groups not only hire clinician investigators but also invest in their development, rather than rely on the few programs that have several such faculty members. With this strategy, we could dramatically increase the number of hospitalist clinician investigators from a diverse background of training institutions.

SHM could also play a greater role in organizing events for networking and mentoring for trainees and medical students interested in pursuing a career in hospital medicine research. It is also critically important that hospital medicine groups actively recruit, retain, and develop URiM hospital medicine research faculty in order to attract talented researchers and actively participate in the necessary effort to mitigate the inequities prevalent throughout our healthcare system.

CONCLUSION

Despite the growth of hospital medicine over the past decade, there remains a dearth of hospitalist clinician investigators at major AMCs in the United States. This may be due in part to lack of research resources and mentorship within hospital medicine groups. We believe that investment in these resources, expanded funding opportunities, mentorship development, research fellowship programs, and greater exposure of trainees to hospitalist researchers are solutions that should be strongly considered to develop hospitalist clinician investigators.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank HOMERuN executive committee members, including Grant Fletcher, MD, James Harrison, PhD, BSC, MPH, Peter K. Lindenauer, MD, Melissa Mattison, MD, David Meltzer, MD, PhD, Joshua Metlay, MD, PhD, Jennifer Myers, MD, Sumant Ranji, MD, Gregory Ruhnke, MD, MPH, Edmondo Robinson, MD, MBA, and Neil Sehgal, MPH PhD, for their assistance in developing the survey. They also thank Tiffany Lee, MA, for her project management assistance for HOMERuN.

1. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000 – The 20th anniversary of the hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1009-1011. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1607958

2. Auerbach AD, Patel MS, Metlay JP, et al. The Hospital Medicine Reengineering Network (HOMERuN): a learning organization focused on improving hospital care. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):415-420. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000000139

3. Roskoski R Jr, Parslow TG. Ranking Tables of NIH funding to US medical schools in 2019. Blue Ridge Institute for Medical Research. Published 2020. Updated July 14, 2020. Accessed July 30, 2020. http://www.brimr.org/NIH_Awards/2019/NIH_Awards_2019.htm

4. Reid MB, Misky GJ, Harrison RA, Sharpe B, Auerbach A, Glasheen JJ. Mentorship, productivity, and promotion among academic hospitalists. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):23-27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1892-5

5. Miller CS, Fogerty RL, Gann J, Bruti CP, Klein R; The Society of General Internal Medicine Membership Committee. The growth of hospitalists and the future of the society of general internal medicine: results from the 2014 membership survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(11):1179-1185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4126-7

6. Chopra V, Burden M, Jones CD, et al; Society of Hospital Medicine Research Committee. State of research in adult hospital medicine: results of a national survey. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(4):207-211. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3136

7. Seymann GB, Southern W, Burger A, et al. Features of successful academic hospitalist programs: insights from the SCHOLAR (SuCcessful HOspitaLists in academics and research) project. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(10):708-713. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2603

8. Harrison R, Hunter AJ, Sharpe B, Auerbach AD. Survey of US academic hospitalist leaders about mentorship and academic activities in hospitalist groups. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(1):5-9. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.836

9. Dang Do AN, Munchhof AM, Terry C, Emmett T, Kara A. Research and publication trends in hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):148-154. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2148

10. Sehgal NL, Sharpe BA, Auerbach AA, Wachter RM. Investing in the future: building an academic hospitalist faculty development program. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(3):161-166. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.845

11. Ranji SR, Rosenman DJ, Amin AN, Kripalani S. Hospital medicine fellowships: works in progress. Am J Med. 2006;119(1):72.e1-72.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.07.061

12. Shah NH, Rhim HJ, Maniscalco J, Wilson K, Rassbach C. The current state of pediatric hospital medicine fellowships: a survey of program directors. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(5):324-328. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2571

13. Jerardi KE, Fisher E, Rassbach C, et al; Council of Pediatric Hospital Medicine Fellowship Directors. Development of a curricular framework for pediatric hospital medicine fellowships. Pediatrics. 2017;140(1):e20170698. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-0698

14. Lewis RJ, Neumar RW. Research in emergency medicine: building the investigator pipeline. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;72(6):691-695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.10.019

15. Flanders SA, Kaufman SR, Nallamothu BK, Saint S. The University of Michigan Specialist-Hospitalist Allied Research Program: jumpstarting hospital medicine research. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(4):308-313. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.342

In their report celebrating the increase in the number of hospitalists from a few hundred in the 1990s to more than 50,000 in 2016, Drs Robert Wachter and Lee Goldman also noted the stunted growth of productive hospital medicine research programs, which presents a challenge to academic credibility in hospital medicine.1 Given the substantial increase in the number of hospitalists over the past two decades, we surveyed adult academic hospital medicine groups to quantify the number of hospitalist clinician investigators and identify gaps in resources for researchers. The number of clinician investigators supported at academic medical centers (AMCs) remains disturbingly low despite the rapid growth of our specialty. Some programs also reported a lack of access to fundamental research services. We report selected results from our survey and provide recommendations to support and facilitate the development of clinician investigators in hospital medicine.

DEARTH OF CLINICIAN INVESTIGATORS IN HOSPITAL MEDICINE

We performed a survey of hospital medicine programs at AMCs in the United States through the Hospital Medicine Reengineering Network (HOMERuN), a hospital medicine research collaborative that facilitates and conducts multisite research studies.2 The purpose of this survey was to obtain a profile of adult academic hospital medicine groups. Surveys were distributed via email to directors and/or senior leaders of each hospital medicine group between January and August 2019. In the survey, a clinician investigator was defined as “faculty whose primary nonclinical focus is scientific papers and grant writing.”

We received responses from 43 of the 86 invitees (50%), each of whom represented a unique hospital medicine group; 41 of the representatives responded to the questions concerning available research services. Collectively, these 43 programs represented 2,503 hospitalists. There were 79 clinician investigators reported among all surveyed hospital medicine groups (3.1% of all hospitalists). The median number of clinician investigators per hospital medicine group was 0 (range 0-12) (Appendix Figure 1), and 22 of 43 (51.2%) hospital medicine groups reported having no clinician investigators. Two of the hospital medicine groups, however, reported having 12 clinician investigators at their respective institutions, comprising nearly one third of the total number of clinician investigators reported in the survey.

Many of the programs reported lack of access to resources such as research assistants (56.1%) and dedicated research fellowships (53.7%) (Appendix Figure 2). A number of groups reported a need for more support for various junior faculty development activities, including research mentoring (53.5%), networking with other researchers (60.5%), and access to clinical data from multiple sites (62.8%).

One of the limitations of this survey was the manner in which the participating hospital medicine groups were chosen. Selection was based on groups affiliated with HOMERuN; among those chosen were highly visible US AMCs, including 70% of the top 20 AMCs based on National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding.3 Therefore, our results likely overestimate the research presence of hospital medicine across all AMCs in the United States.

LACK OF GROWTH OVER TIME: CONTEXTUALIZATION AND IMPLICATIONS

Despite the substantial growth of hospital medicine over the past 2 decades, there has been no proportional increase in the number of hospitalist clinician investigators, with earlier surveys also demonstrating low numbers.4,5 Along with the survey by Chopra and colleagues published in 2019,6 our survey provides an additional contemporary appraisal of research activities for adult academic hospital medicine groups. In the survey by Chopra et al, only 54% (15 of 28) of responding programs reported having any faculty with research as their major activity (ie, >50% effort), and 3% of total faculty reported having funding for >50% effort toward research.6 Our study expands upon these findings by providing more detailed data on the number of clinician investigators per hospital medicine group. Results of our survey showed a concentration of hospitalists within a small number of programs, which may have contributed to the observed lack of growth. We also expand on prior work by identifying a lack of resources and services to support hospitalist researchers.

The findings of our survey have important implications for the field of hospital medicine. Without a critical mass of hospitalist clinician investigators, the quality of research that addresses important questions in our field will suffer. It will also limit academic credibility of the field, as well as individual academic achievement; previous studies have consistently demonstrated that few hospitalists at AMCs achieve the rank of associate or full professor.5-9

POTENTIAL EXPLANATIONS FOR LACK OF RESEARCH GROWTH

The results of our study additionally offer possible explanations for the dearth of clinician investigators in hospital medicine. The limited access to research resources and fellowship training identified in our survey are critical domains that must be addressed in order to develop successful academic hospital medicine programs.4,6,8,10

Regarding dedicated hospital medicine research fellowships, there are only a handful across the country. The small number of existing research fellowships only have one or two fellows per year, and these positions often go unfilled because of a lack of applicants and lower salaries compared to full-time clinical positions.11 The lack of applicants for adult hospital medicine fellowship positions is also integrally linked to board certification requirements. Unlike pediatric hospital medicine where additional fellowship training is required to become board-certified, no such fellowship is required in adult hospital medicine. In pediatrics, this requirement has led to a rapid increase in the number of fellowships with scholarly work requirements (more than 60 fellowships, plus additional programs in development) and greater standardization among training experiences.12,13

The lack of fellowship applicants may also stem from the fact that many trainees are not aware of a potential career as a hospitalist clinician investigator due to limited exposure to this career at most AMCs. Our results revealed that nearly half of sites in our survey had zero clinician investigators, depriving trainees at these programs of role models and thus perpetuating a negative feedback loop. Lastly, although unfilled fellowship positions may indicate that demand is a larger problem than supply, it is also true that fellowship programs generate their own demand through recruitment efforts and the gradual establishment of a positive reputation.

Another potential explanation could relate to the development of hospital medicine in response to rising clinical demands at hospitals: compared with other medical specialties, AMCs may regard hospitalists as being clinicians first and academicians second.1,7,10 Also, hospitalists may be perceived as being beholden to hospitals and less engaged with their surrounding communities than other general medicine fields. With a small footprint in health equity research, academic hospital medicine may be less of a draw to generalists interested in pursuing this area of research. Further, there are very few underrepresented in medicine (URiM) hospital medicine research faculty.5

Another challenge to the career development of hospitalist researchers is the lack of available funding for the type of research typically conducted by hospitalists (eg, rigorous quality improvement implementation and evaluation, optimizing best evidence-based care delivery models, evaluation of patient safety in the hospital setting). As hospitalists tend to be system-level thinkers, this lack of funding may steer potential researchers away from externally funded research careers and into hospital operations and quality improvement positions. Also, unlike other medical specialties, there is no dedicated NIH funding source for hospital medicine research (eg, cardiology and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute), placing hospitalists at a disadvantage in seeking funding compared to subspecialists.

STRATEGIES TO ENHANCE RESEARCH PRESENCE

We recommend several approaches—ones that should be pursued simultaneously—to increase the number of clinician investigators in hospital medicine. First, hospital medicine groups and their respective divisions, departments, and hospitals should allocate funding to support research resources; this includes investing in research assistants, data analysts, statisticians, and administrative support. Through the funding of such research infrastructure programs, AMCs could incentivize hospitalists to research best approaches to improve the value of healthcare delivery, ultimately leading to cost savings.

With 60% of respondents identifying the need for improved access to data across multiple sites, our survey also emphasizes the requirement for further collaboration among hospital medicine groups. Such collaboration could lead to high-powered observational studies and the evaluation of interventions across multiple sites, thus improving the generalizability of study findings.

The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) and its research committee can continue to expand the research footprint of hospital medicine. To date, the committee has achieved this by highlighting hospitalist research activity at the SHM Annual Conference Scientific Abstract and Poster Competition and developing a visiting professorship exchange program. In addition to these efforts, SHM could foster collaboration and networking between institutions, as well as take advantage of the current political push for expanded Medicare access by lobbying for robust funding for the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, which could provide more opportunities for hospitalists to study the effects of healthcare policy reform on the delivery of inpatient care.

Another strategy to increase the number of hospitalist clinician investigators is to expand hospital medicine research fellowships and recruit trainees for these programs. Fellowships could be internally funded wherein a fellow’s clinical productivity is used to offset the costs associated with obtaining advanced degrees. As an incentive to encourage applicants to temporarily forego a full-time clinical salary during fellowship, hospital medicine groups could offer expanded moonlighting opportunities and contribute to repayment of medical school loans. Hospital medicine groups should also advocate for NIH-funded T32 or K12 training grants for hospital medicine. (There are, however, challenges with this approach because the number of T32 spots per NIH institute is usually fixed). The success of academic emergency medicine offers a precedent for such efforts: After the development of a K12 research training program in emergency medicine, the number of NIH-sponsored principal investigators in this specialty increased by 40% in 6 years.14 Additionally, now that fellowships are required for the pediatric hospital medicine clinician investigators, it would be revealing to track the growth of this workforce.12,13

Structured and formalized mentorship is an essential part of the development of clinician investigators in hospital medicine.4,7,8,10 One successful strategy for mentorship has been the partnering of hospital medicine groups with faculty of general internal medicine and other subspecialty divisions with robust research programs.7,8,15 In addition to developing sustainable mentorship programs, hospital medicine researchers must increase their visibility to trainees. Therefore, it is essential that the majority of academic hospital medicine groups not only hire clinician investigators but also invest in their development, rather than rely on the few programs that have several such faculty members. With this strategy, we could dramatically increase the number of hospitalist clinician investigators from a diverse background of training institutions.

SHM could also play a greater role in organizing events for networking and mentoring for trainees and medical students interested in pursuing a career in hospital medicine research. It is also critically important that hospital medicine groups actively recruit, retain, and develop URiM hospital medicine research faculty in order to attract talented researchers and actively participate in the necessary effort to mitigate the inequities prevalent throughout our healthcare system.

CONCLUSION

Despite the growth of hospital medicine over the past decade, there remains a dearth of hospitalist clinician investigators at major AMCs in the United States. This may be due in part to lack of research resources and mentorship within hospital medicine groups. We believe that investment in these resources, expanded funding opportunities, mentorship development, research fellowship programs, and greater exposure of trainees to hospitalist researchers are solutions that should be strongly considered to develop hospitalist clinician investigators.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank HOMERuN executive committee members, including Grant Fletcher, MD, James Harrison, PhD, BSC, MPH, Peter K. Lindenauer, MD, Melissa Mattison, MD, David Meltzer, MD, PhD, Joshua Metlay, MD, PhD, Jennifer Myers, MD, Sumant Ranji, MD, Gregory Ruhnke, MD, MPH, Edmondo Robinson, MD, MBA, and Neil Sehgal, MPH PhD, for their assistance in developing the survey. They also thank Tiffany Lee, MA, for her project management assistance for HOMERuN.

In their report celebrating the increase in the number of hospitalists from a few hundred in the 1990s to more than 50,000 in 2016, Drs Robert Wachter and Lee Goldman also noted the stunted growth of productive hospital medicine research programs, which presents a challenge to academic credibility in hospital medicine.1 Given the substantial increase in the number of hospitalists over the past two decades, we surveyed adult academic hospital medicine groups to quantify the number of hospitalist clinician investigators and identify gaps in resources for researchers. The number of clinician investigators supported at academic medical centers (AMCs) remains disturbingly low despite the rapid growth of our specialty. Some programs also reported a lack of access to fundamental research services. We report selected results from our survey and provide recommendations to support and facilitate the development of clinician investigators in hospital medicine.

DEARTH OF CLINICIAN INVESTIGATORS IN HOSPITAL MEDICINE

We performed a survey of hospital medicine programs at AMCs in the United States through the Hospital Medicine Reengineering Network (HOMERuN), a hospital medicine research collaborative that facilitates and conducts multisite research studies.2 The purpose of this survey was to obtain a profile of adult academic hospital medicine groups. Surveys were distributed via email to directors and/or senior leaders of each hospital medicine group between January and August 2019. In the survey, a clinician investigator was defined as “faculty whose primary nonclinical focus is scientific papers and grant writing.”

We received responses from 43 of the 86 invitees (50%), each of whom represented a unique hospital medicine group; 41 of the representatives responded to the questions concerning available research services. Collectively, these 43 programs represented 2,503 hospitalists. There were 79 clinician investigators reported among all surveyed hospital medicine groups (3.1% of all hospitalists). The median number of clinician investigators per hospital medicine group was 0 (range 0-12) (Appendix Figure 1), and 22 of 43 (51.2%) hospital medicine groups reported having no clinician investigators. Two of the hospital medicine groups, however, reported having 12 clinician investigators at their respective institutions, comprising nearly one third of the total number of clinician investigators reported in the survey.

Many of the programs reported lack of access to resources such as research assistants (56.1%) and dedicated research fellowships (53.7%) (Appendix Figure 2). A number of groups reported a need for more support for various junior faculty development activities, including research mentoring (53.5%), networking with other researchers (60.5%), and access to clinical data from multiple sites (62.8%).

One of the limitations of this survey was the manner in which the participating hospital medicine groups were chosen. Selection was based on groups affiliated with HOMERuN; among those chosen were highly visible US AMCs, including 70% of the top 20 AMCs based on National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding.3 Therefore, our results likely overestimate the research presence of hospital medicine across all AMCs in the United States.

LACK OF GROWTH OVER TIME: CONTEXTUALIZATION AND IMPLICATIONS

Despite the substantial growth of hospital medicine over the past 2 decades, there has been no proportional increase in the number of hospitalist clinician investigators, with earlier surveys also demonstrating low numbers.4,5 Along with the survey by Chopra and colleagues published in 2019,6 our survey provides an additional contemporary appraisal of research activities for adult academic hospital medicine groups. In the survey by Chopra et al, only 54% (15 of 28) of responding programs reported having any faculty with research as their major activity (ie, >50% effort), and 3% of total faculty reported having funding for >50% effort toward research.6 Our study expands upon these findings by providing more detailed data on the number of clinician investigators per hospital medicine group. Results of our survey showed a concentration of hospitalists within a small number of programs, which may have contributed to the observed lack of growth. We also expand on prior work by identifying a lack of resources and services to support hospitalist researchers.

The findings of our survey have important implications for the field of hospital medicine. Without a critical mass of hospitalist clinician investigators, the quality of research that addresses important questions in our field will suffer. It will also limit academic credibility of the field, as well as individual academic achievement; previous studies have consistently demonstrated that few hospitalists at AMCs achieve the rank of associate or full professor.5-9

POTENTIAL EXPLANATIONS FOR LACK OF RESEARCH GROWTH

The results of our study additionally offer possible explanations for the dearth of clinician investigators in hospital medicine. The limited access to research resources and fellowship training identified in our survey are critical domains that must be addressed in order to develop successful academic hospital medicine programs.4,6,8,10

Regarding dedicated hospital medicine research fellowships, there are only a handful across the country. The small number of existing research fellowships only have one or two fellows per year, and these positions often go unfilled because of a lack of applicants and lower salaries compared to full-time clinical positions.11 The lack of applicants for adult hospital medicine fellowship positions is also integrally linked to board certification requirements. Unlike pediatric hospital medicine where additional fellowship training is required to become board-certified, no such fellowship is required in adult hospital medicine. In pediatrics, this requirement has led to a rapid increase in the number of fellowships with scholarly work requirements (more than 60 fellowships, plus additional programs in development) and greater standardization among training experiences.12,13

The lack of fellowship applicants may also stem from the fact that many trainees are not aware of a potential career as a hospitalist clinician investigator due to limited exposure to this career at most AMCs. Our results revealed that nearly half of sites in our survey had zero clinician investigators, depriving trainees at these programs of role models and thus perpetuating a negative feedback loop. Lastly, although unfilled fellowship positions may indicate that demand is a larger problem than supply, it is also true that fellowship programs generate their own demand through recruitment efforts and the gradual establishment of a positive reputation.

Another potential explanation could relate to the development of hospital medicine in response to rising clinical demands at hospitals: compared with other medical specialties, AMCs may regard hospitalists as being clinicians first and academicians second.1,7,10 Also, hospitalists may be perceived as being beholden to hospitals and less engaged with their surrounding communities than other general medicine fields. With a small footprint in health equity research, academic hospital medicine may be less of a draw to generalists interested in pursuing this area of research. Further, there are very few underrepresented in medicine (URiM) hospital medicine research faculty.5

Another challenge to the career development of hospitalist researchers is the lack of available funding for the type of research typically conducted by hospitalists (eg, rigorous quality improvement implementation and evaluation, optimizing best evidence-based care delivery models, evaluation of patient safety in the hospital setting). As hospitalists tend to be system-level thinkers, this lack of funding may steer potential researchers away from externally funded research careers and into hospital operations and quality improvement positions. Also, unlike other medical specialties, there is no dedicated NIH funding source for hospital medicine research (eg, cardiology and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute), placing hospitalists at a disadvantage in seeking funding compared to subspecialists.

STRATEGIES TO ENHANCE RESEARCH PRESENCE

We recommend several approaches—ones that should be pursued simultaneously—to increase the number of clinician investigators in hospital medicine. First, hospital medicine groups and their respective divisions, departments, and hospitals should allocate funding to support research resources; this includes investing in research assistants, data analysts, statisticians, and administrative support. Through the funding of such research infrastructure programs, AMCs could incentivize hospitalists to research best approaches to improve the value of healthcare delivery, ultimately leading to cost savings.

With 60% of respondents identifying the need for improved access to data across multiple sites, our survey also emphasizes the requirement for further collaboration among hospital medicine groups. Such collaboration could lead to high-powered observational studies and the evaluation of interventions across multiple sites, thus improving the generalizability of study findings.

The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) and its research committee can continue to expand the research footprint of hospital medicine. To date, the committee has achieved this by highlighting hospitalist research activity at the SHM Annual Conference Scientific Abstract and Poster Competition and developing a visiting professorship exchange program. In addition to these efforts, SHM could foster collaboration and networking between institutions, as well as take advantage of the current political push for expanded Medicare access by lobbying for robust funding for the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, which could provide more opportunities for hospitalists to study the effects of healthcare policy reform on the delivery of inpatient care.

Another strategy to increase the number of hospitalist clinician investigators is to expand hospital medicine research fellowships and recruit trainees for these programs. Fellowships could be internally funded wherein a fellow’s clinical productivity is used to offset the costs associated with obtaining advanced degrees. As an incentive to encourage applicants to temporarily forego a full-time clinical salary during fellowship, hospital medicine groups could offer expanded moonlighting opportunities and contribute to repayment of medical school loans. Hospital medicine groups should also advocate for NIH-funded T32 or K12 training grants for hospital medicine. (There are, however, challenges with this approach because the number of T32 spots per NIH institute is usually fixed). The success of academic emergency medicine offers a precedent for such efforts: After the development of a K12 research training program in emergency medicine, the number of NIH-sponsored principal investigators in this specialty increased by 40% in 6 years.14 Additionally, now that fellowships are required for the pediatric hospital medicine clinician investigators, it would be revealing to track the growth of this workforce.12,13

Structured and formalized mentorship is an essential part of the development of clinician investigators in hospital medicine.4,7,8,10 One successful strategy for mentorship has been the partnering of hospital medicine groups with faculty of general internal medicine and other subspecialty divisions with robust research programs.7,8,15 In addition to developing sustainable mentorship programs, hospital medicine researchers must increase their visibility to trainees. Therefore, it is essential that the majority of academic hospital medicine groups not only hire clinician investigators but also invest in their development, rather than rely on the few programs that have several such faculty members. With this strategy, we could dramatically increase the number of hospitalist clinician investigators from a diverse background of training institutions.

SHM could also play a greater role in organizing events for networking and mentoring for trainees and medical students interested in pursuing a career in hospital medicine research. It is also critically important that hospital medicine groups actively recruit, retain, and develop URiM hospital medicine research faculty in order to attract talented researchers and actively participate in the necessary effort to mitigate the inequities prevalent throughout our healthcare system.

CONCLUSION

Despite the growth of hospital medicine over the past decade, there remains a dearth of hospitalist clinician investigators at major AMCs in the United States. This may be due in part to lack of research resources and mentorship within hospital medicine groups. We believe that investment in these resources, expanded funding opportunities, mentorship development, research fellowship programs, and greater exposure of trainees to hospitalist researchers are solutions that should be strongly considered to develop hospitalist clinician investigators.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank HOMERuN executive committee members, including Grant Fletcher, MD, James Harrison, PhD, BSC, MPH, Peter K. Lindenauer, MD, Melissa Mattison, MD, David Meltzer, MD, PhD, Joshua Metlay, MD, PhD, Jennifer Myers, MD, Sumant Ranji, MD, Gregory Ruhnke, MD, MPH, Edmondo Robinson, MD, MBA, and Neil Sehgal, MPH PhD, for their assistance in developing the survey. They also thank Tiffany Lee, MA, for her project management assistance for HOMERuN.

1. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000 – The 20th anniversary of the hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1009-1011. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1607958

2. Auerbach AD, Patel MS, Metlay JP, et al. The Hospital Medicine Reengineering Network (HOMERuN): a learning organization focused on improving hospital care. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):415-420. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000000139

3. Roskoski R Jr, Parslow TG. Ranking Tables of NIH funding to US medical schools in 2019. Blue Ridge Institute for Medical Research. Published 2020. Updated July 14, 2020. Accessed July 30, 2020. http://www.brimr.org/NIH_Awards/2019/NIH_Awards_2019.htm

4. Reid MB, Misky GJ, Harrison RA, Sharpe B, Auerbach A, Glasheen JJ. Mentorship, productivity, and promotion among academic hospitalists. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):23-27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1892-5

5. Miller CS, Fogerty RL, Gann J, Bruti CP, Klein R; The Society of General Internal Medicine Membership Committee. The growth of hospitalists and the future of the society of general internal medicine: results from the 2014 membership survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(11):1179-1185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4126-7

6. Chopra V, Burden M, Jones CD, et al; Society of Hospital Medicine Research Committee. State of research in adult hospital medicine: results of a national survey. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(4):207-211. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3136

7. Seymann GB, Southern W, Burger A, et al. Features of successful academic hospitalist programs: insights from the SCHOLAR (SuCcessful HOspitaLists in academics and research) project. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(10):708-713. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2603

8. Harrison R, Hunter AJ, Sharpe B, Auerbach AD. Survey of US academic hospitalist leaders about mentorship and academic activities in hospitalist groups. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(1):5-9. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.836

9. Dang Do AN, Munchhof AM, Terry C, Emmett T, Kara A. Research and publication trends in hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):148-154. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2148

10. Sehgal NL, Sharpe BA, Auerbach AA, Wachter RM. Investing in the future: building an academic hospitalist faculty development program. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(3):161-166. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.845

11. Ranji SR, Rosenman DJ, Amin AN, Kripalani S. Hospital medicine fellowships: works in progress. Am J Med. 2006;119(1):72.e1-72.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.07.061

12. Shah NH, Rhim HJ, Maniscalco J, Wilson K, Rassbach C. The current state of pediatric hospital medicine fellowships: a survey of program directors. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(5):324-328. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2571

13. Jerardi KE, Fisher E, Rassbach C, et al; Council of Pediatric Hospital Medicine Fellowship Directors. Development of a curricular framework for pediatric hospital medicine fellowships. Pediatrics. 2017;140(1):e20170698. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-0698

14. Lewis RJ, Neumar RW. Research in emergency medicine: building the investigator pipeline. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;72(6):691-695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.10.019

15. Flanders SA, Kaufman SR, Nallamothu BK, Saint S. The University of Michigan Specialist-Hospitalist Allied Research Program: jumpstarting hospital medicine research. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(4):308-313. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.342

1. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000 – The 20th anniversary of the hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1009-1011. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1607958

2. Auerbach AD, Patel MS, Metlay JP, et al. The Hospital Medicine Reengineering Network (HOMERuN): a learning organization focused on improving hospital care. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):415-420. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000000139

3. Roskoski R Jr, Parslow TG. Ranking Tables of NIH funding to US medical schools in 2019. Blue Ridge Institute for Medical Research. Published 2020. Updated July 14, 2020. Accessed July 30, 2020. http://www.brimr.org/NIH_Awards/2019/NIH_Awards_2019.htm

4. Reid MB, Misky GJ, Harrison RA, Sharpe B, Auerbach A, Glasheen JJ. Mentorship, productivity, and promotion among academic hospitalists. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):23-27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1892-5

5. Miller CS, Fogerty RL, Gann J, Bruti CP, Klein R; The Society of General Internal Medicine Membership Committee. The growth of hospitalists and the future of the society of general internal medicine: results from the 2014 membership survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(11):1179-1185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4126-7

6. Chopra V, Burden M, Jones CD, et al; Society of Hospital Medicine Research Committee. State of research in adult hospital medicine: results of a national survey. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(4):207-211. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3136

7. Seymann GB, Southern W, Burger A, et al. Features of successful academic hospitalist programs: insights from the SCHOLAR (SuCcessful HOspitaLists in academics and research) project. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(10):708-713. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2603

8. Harrison R, Hunter AJ, Sharpe B, Auerbach AD. Survey of US academic hospitalist leaders about mentorship and academic activities in hospitalist groups. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(1):5-9. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.836

9. Dang Do AN, Munchhof AM, Terry C, Emmett T, Kara A. Research and publication trends in hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):148-154. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2148

10. Sehgal NL, Sharpe BA, Auerbach AA, Wachter RM. Investing in the future: building an academic hospitalist faculty development program. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(3):161-166. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.845

11. Ranji SR, Rosenman DJ, Amin AN, Kripalani S. Hospital medicine fellowships: works in progress. Am J Med. 2006;119(1):72.e1-72.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.07.061

12. Shah NH, Rhim HJ, Maniscalco J, Wilson K, Rassbach C. The current state of pediatric hospital medicine fellowships: a survey of program directors. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(5):324-328. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2571

13. Jerardi KE, Fisher E, Rassbach C, et al; Council of Pediatric Hospital Medicine Fellowship Directors. Development of a curricular framework for pediatric hospital medicine fellowships. Pediatrics. 2017;140(1):e20170698. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-0698

14. Lewis RJ, Neumar RW. Research in emergency medicine: building the investigator pipeline. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;72(6):691-695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.10.019

15. Flanders SA, Kaufman SR, Nallamothu BK, Saint S. The University of Michigan Specialist-Hospitalist Allied Research Program: jumpstarting hospital medicine research. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(4):308-313. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.342

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Hospital Ward Adaptation During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A National Survey of Academic Medical Centers

The coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has resulted in a surge in hospitalizations of patients with a novel, serious, and highly contagious infectious disease for which there is yet no proven treatment. Currently, much of the focus has been on intensive care unit (ICU) and ventilator capacity for the sickest of these patients who develop respiratory failure. However, most hospitalized patients are being cared for in general medical units.1 Some evidence exists to describe adaptations to capacity needs outside of medical wards,2-4 but few studies have specifically addressed the ward setting. Therefore, there is a pressing need for evidence to describe how to expand capacity and deliver medical ward–based care.

To better understand how inpatient care in the United States is adapting to the COVID-19 pandemic, we surveyed 72 sites participating in the Hospital Medicine Reengineering Network (HOMERuN), a national consortium of hospital medicine groups.5 We report results of this survey, carried out between April 3 and April 5, 2020.

METHODS

Sites and Subjects

HOMERuN is a collaborative network of hospitalists from across the United States whose primary goal is to catalyze research and share best practices across hospital medicine groups. Using surveys of Hospital Medicine leaders, targeted medical record review, and other methods, HOMERuN’s funded research interests to date have included care transitions, workforce issues, patient and family engagement, and diagnostic errors. Sites participating in HOMERuN sites are relatively large urban academic medical centers (Appendix).

Survey Development and Deployment

We designed a focused survey that aimed to provide a snapshot of evolving operational and clinical aspects of COVID-19 care (Appendix). Domains included COVID-19 testing turnaround times, personal protective equipment (PPE) stewardship,6 features of respiratory isolation units (RIUs; ie, dedicated units for patients with known or suspected COVID-19), and observed effects on clinical care. We tested the instrument to ensure feasibility and clarity internally, performed brief cognitive testing with several hospital medicine leaders in HOMERuN, then disseminated the survey by email on April 3, with two follow-up emails on 2 subsequent days. Our study was deemed non–human subjects research by the University of California, San Francisco, Committee on Human Research. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize survey responses.

RESULTS

Of 72 hospitals surveyed, 51 (71%) responded. Mean hospital bed count was 940, three were safety-net hospitals, and one was a community-based teaching center; responding and nonresponding hospitals did not differ significantly in terms of bed count (Appendix).

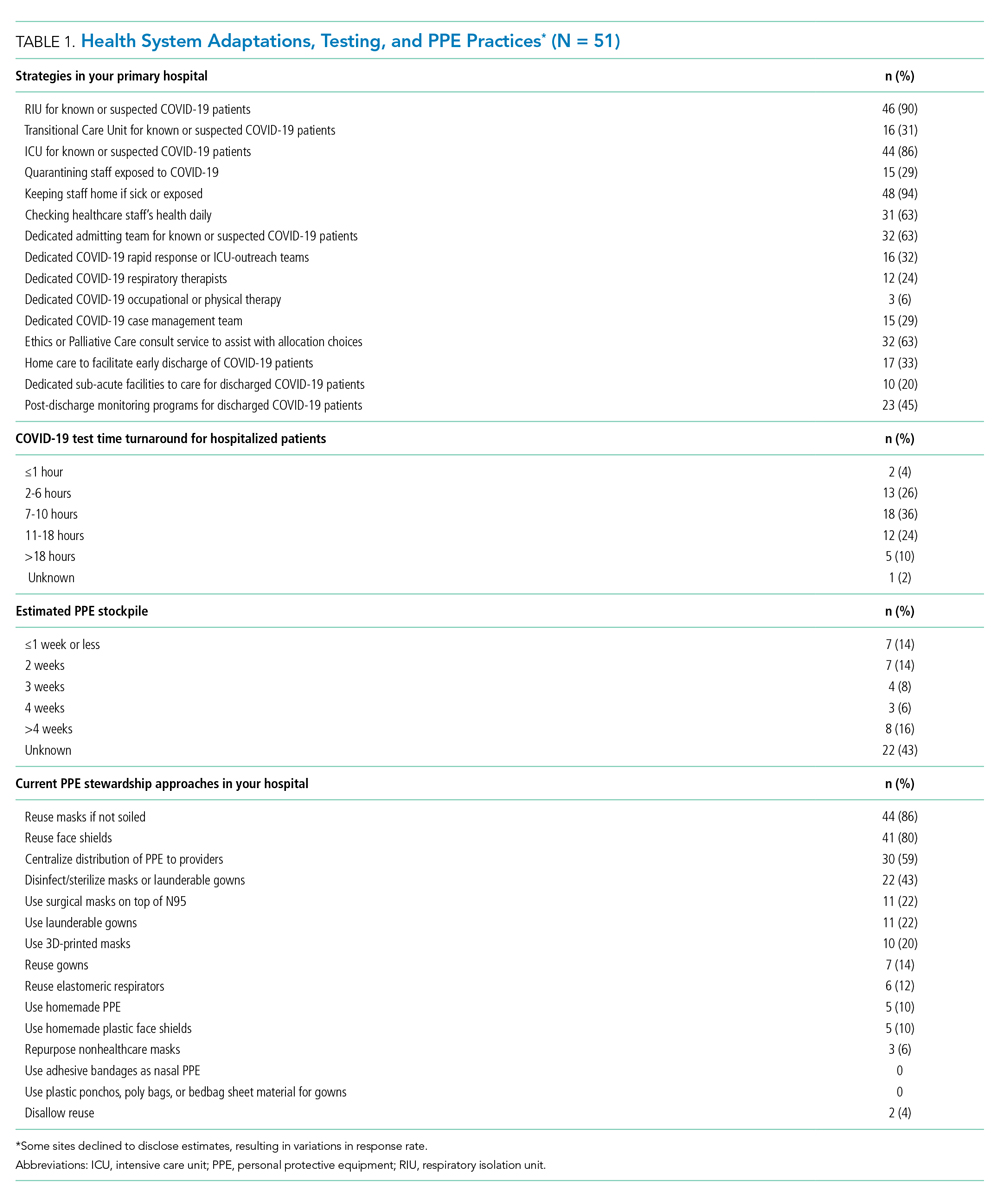

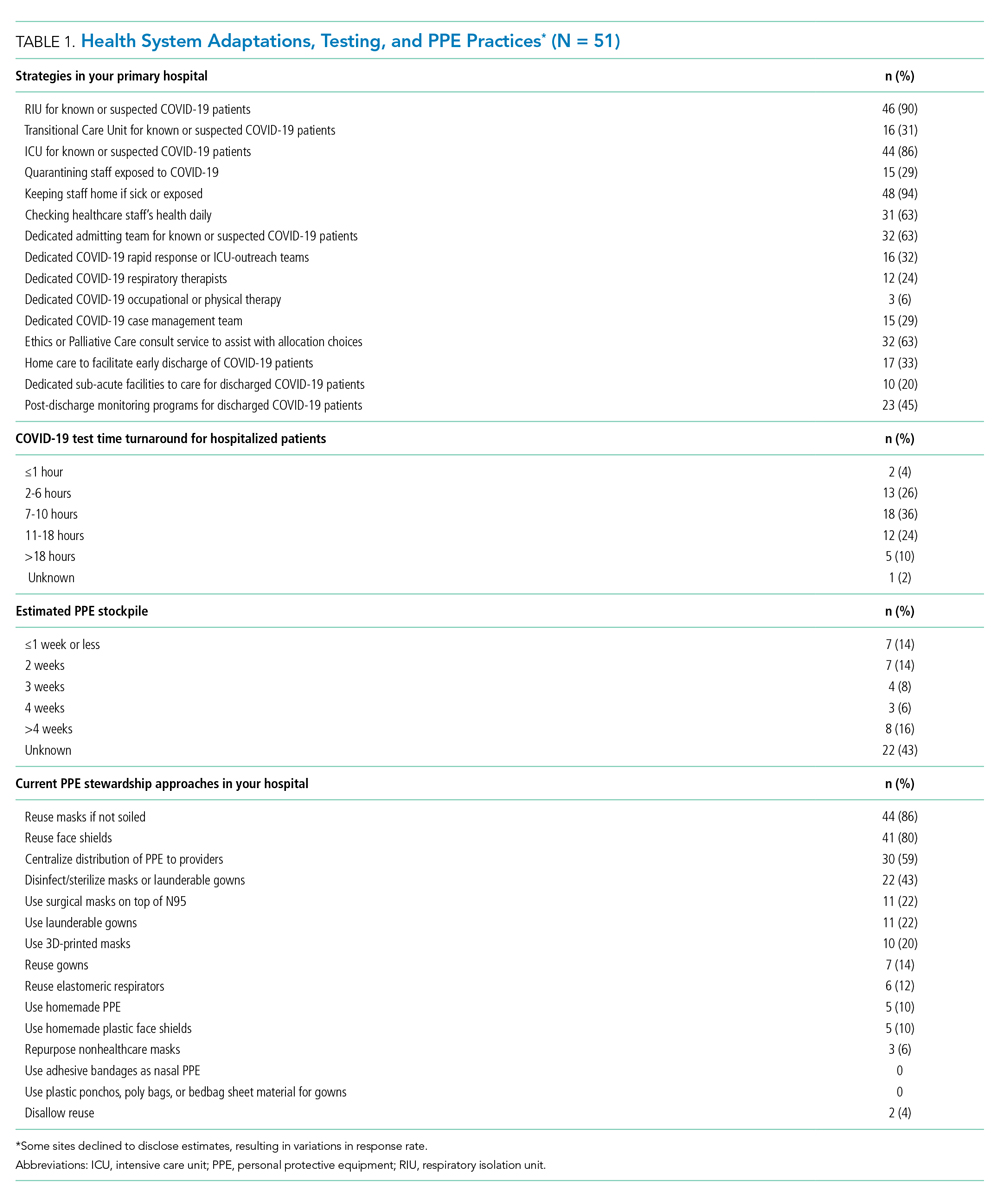

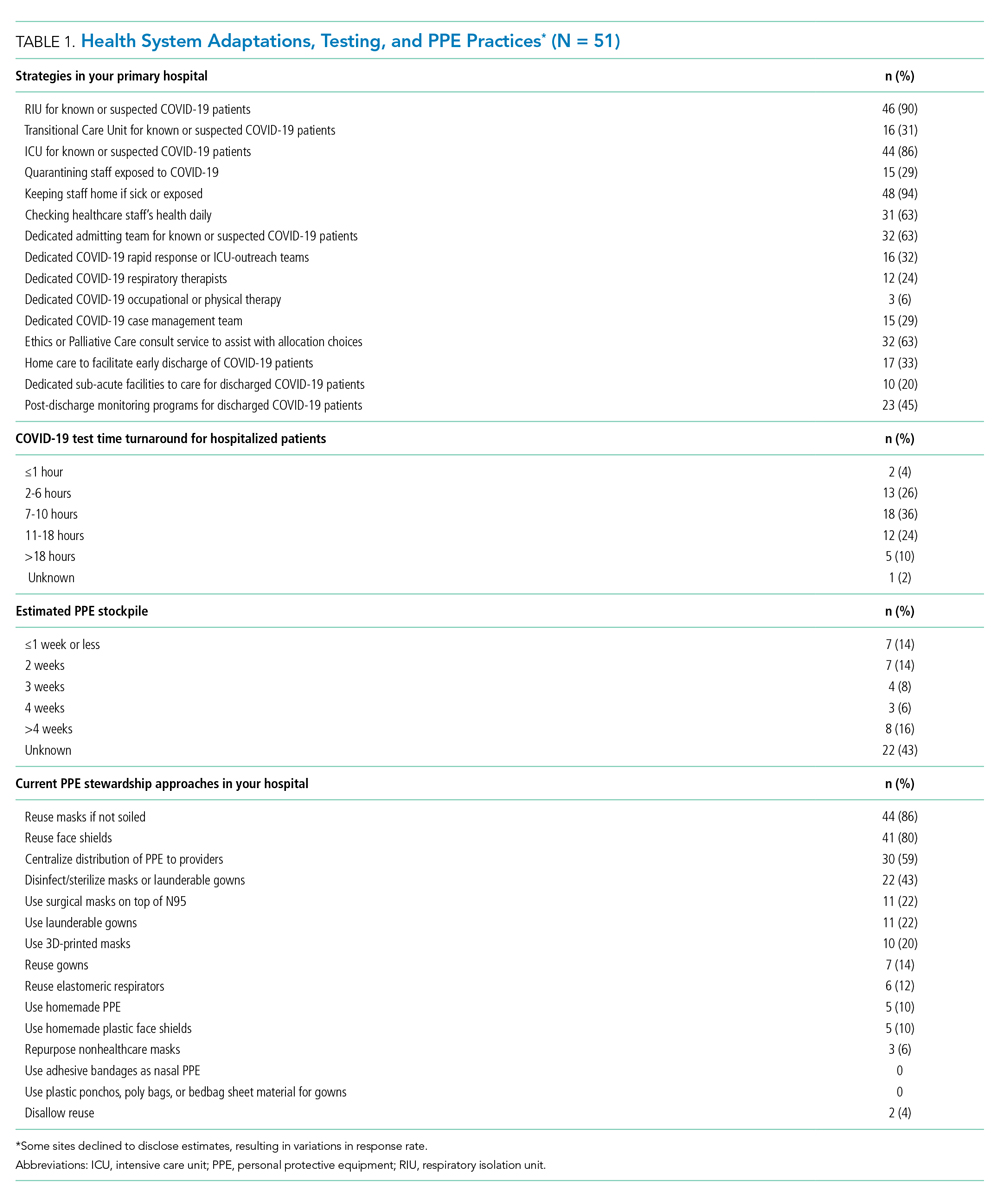

Health System Adaptations, Testing, and PPE Status

Nearly all responding hospitals (46 of 51; 90%) had RIUs for patients with known or suspected COVID-19 (Table 1). Nearly all hospitals took steps to keep potentially sick healthcare providers from infecting others (eg, staying home if sick or exposed). Among respondents, 32% had rapid response teams, 24% had respiratory therapy teams, and 29% had case management teams that were dedicated to COVID-19 care. Thirty-two (63%) had developed models, such as ethics or palliative care consult services, to assist with difficult resource-allocation decisions (eg, how to prioritize ventilator use if demand exceeded supply). Twenty-three (45%) had developed post-acute care monitoring programs dedicated to COVID-19 patients.

At the time of our survey, only 2 sites (4%) reported COVID-19 test time turnaround under 1 hour, and 15 (30%) reported turnaround in less than 6 hours. Of the 29 sites able to provide estimates of PPE stockpile, 14 (48%) reported a supply of 2 weeks or less. The most common approaches to PPE stewardship focused on reuse of masks and face shields if not obviously soiled, centralizing PPE distribution, and disinfecting or sterilizing masks. Ten sites (20%) were utilizing 3-D printed masks, while 10% used homemade face shields or masks.

Characteristics of COVID-19 RIUs

Forty-six hospitals (90% of all respondents) in our cohort had developed RIUs at the time of survey administration. The earliest RIU implementation date was February 10, 2020, and the most recent was launched on the day of our survey. Admission to RIUs was primarily based on clinical factors associated with known or suspected COVID-19 infection (Table 2). The number of non–critical care RIU beds among locations at that time ranged from 10 or less to more than 50. The mean number of hospitalist attendings caring for patients in the RIUs was 10.2, with a mean 4.1 advanced practice providers, 5.5 residents, and 0 medical students. The number of planned patients per attending was typically 5 to 15. Nurses and physicians typically rounded separately. Medical distancing (eg, reducing patient room entry) was accomplished most commonly by grouped timing of medication administration (76% of sites), video links to room outside of rounding times (54% of sites), the use of video or telemedicine during rounds (17%), and clustering of activities such as medication administration or phlebotomy. The most common criteria prompting discharge from the RIU were a negative COVID-19 test (59%) and hospital discharge (57%), though comments from many respondents suggested that discharge criteria were changing rapidly.

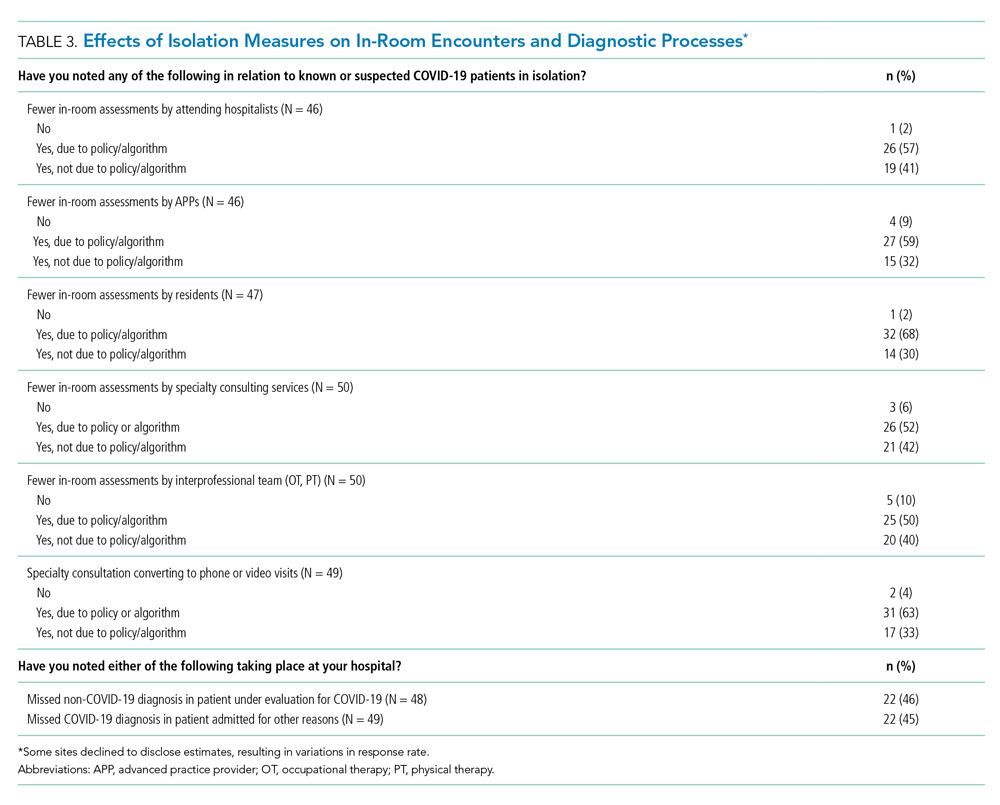

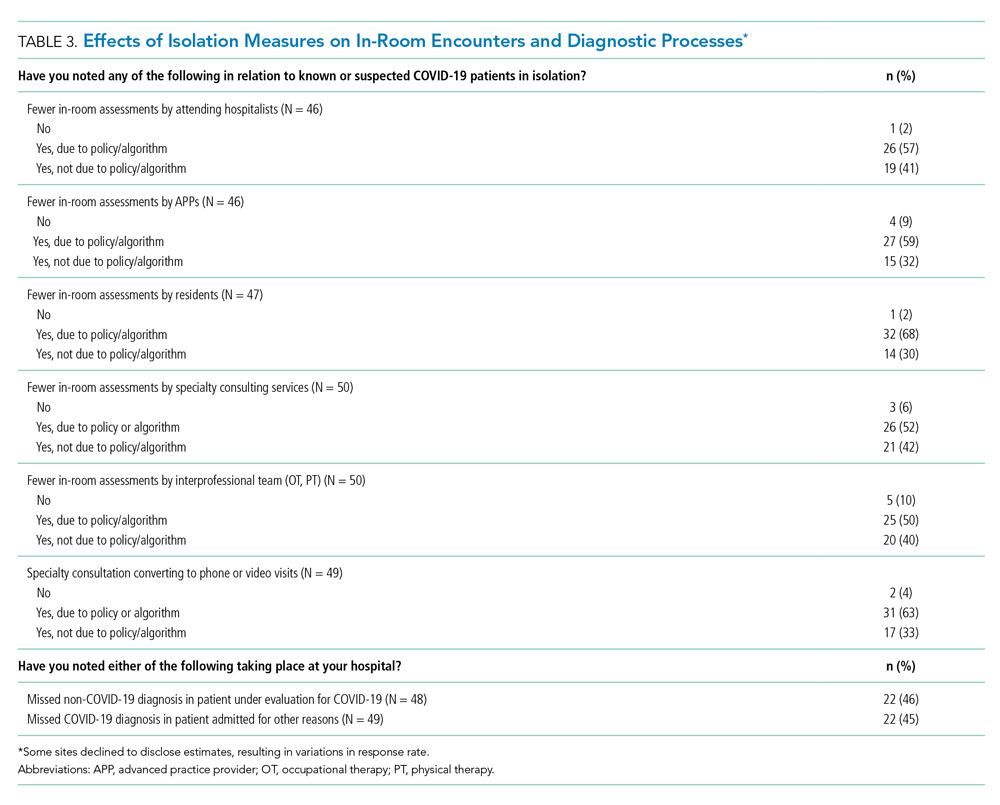

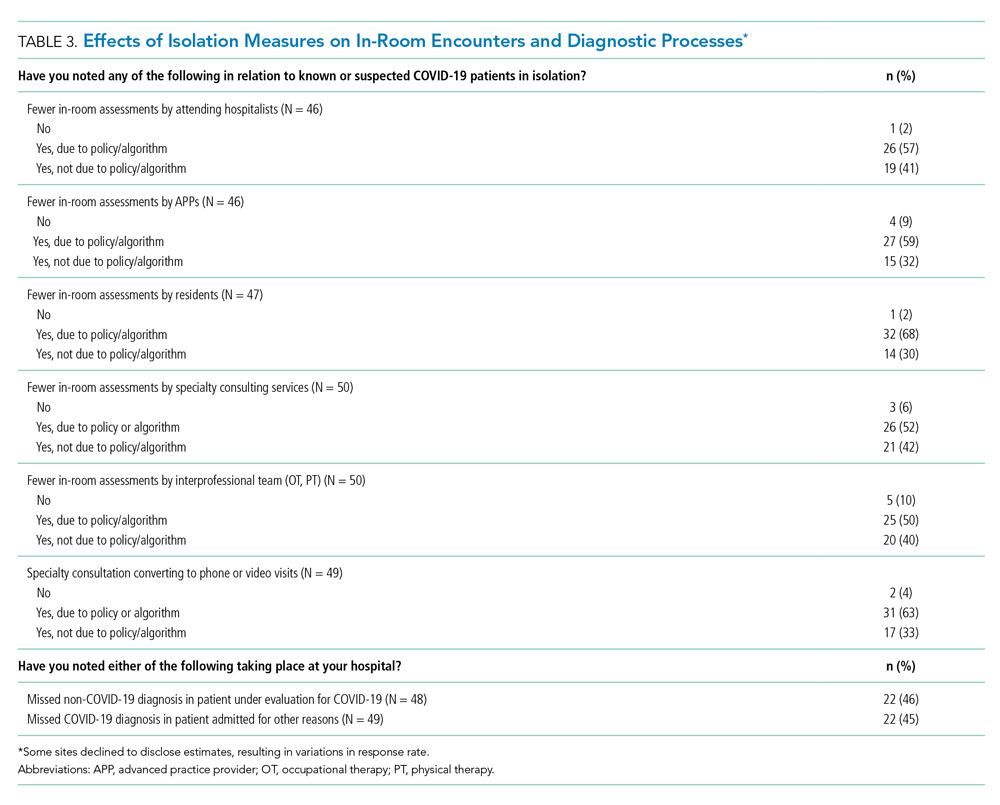

Effects of Isolation Measures on In-Room Encounters and Diagnostic Processes

More than 90% of sites reported decreases in in-room encounter frequency across all provider types whether as a result of policies in place or not. Reductions were reported among hospitalists, advanced practice providers, residents, consultants, and therapists (Table 3). Reduced room entry most often resulted from an established or developing policy, but many noted reduced room entry without formal policies in place. Nearly all sites reported moving specialty consultations to phone or video evaluations. Diagnostic error was commonly reported, with missed non–COVID-19 medical diagnoses among COVID-19 infected patients being reported by 22 sites (46%) and missed COVID-19 diagnoses in patients admitted for other reasons by 22 sites (45%).

DISCUSSION

In this study of medical wards at academic medical centers, we found that, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, hospitals made several changes in a short period of time to adapt to the crisis. These included implementation and rapid expansion of dedicated RIUs, greatly expanded use of inpatient telehealth for patient assessments and consultation, implementation of other approaches to minimize room entry (such as grouping in-room activities), and deployment of ethics consultation services to help manage issues around potential scarcity of life-saving measures such as ventilators. We also found that availability of PPE and timely testing was limited. Finally, a large proportion of sites reported potential diagnostic problems in the assessment of both patients suspected and those not suspected of having COVID-19.

RIUs are emerging as a primary modality for caring for non-ICU COVID-19 patients, though they never involved medical students; we hope the role of students in particular will increase as new models of training emerge in response to the pandemic.7 In contrast, telemedicine evolved rapidly to hold a substantial role in RIUs, with both ward and specialty teams using video visit technology to communicate with patients. COVID-19 has been viewed as a perfect use case for outpatient telemedicine,8 and a growing number of studies are examining its outpatient use9,10; however, to date, somewhat less attention has been paid to inpatient deployment. Although our data suggest telemedicine has found a prominent place in RIUs, it remains to be seen whether it is associated with differences in patient or provider outcomes. For example, deficiencies in the physical examination, limited face-to-face contact, and lack of physical presence could all affect the patient–provider relationship, patient engagement, and the accuracy of the diagnostic process.

Our data suggest the possibility of missing non–COVID-19 diagnoses in patients suspected of COVID-19 and missing COVID-19 in those admitted for nonrespiratory reasons. The latter may be addressed as routine COVID-19 screening of admitted patients becomes commonplace. For the former, however, it is possible that physicians are “anchoring” their thinking on COVID-19 to the exclusion of other diagnoses, that physicians are not fully aware of complications unique to COVID-19 infection (such as thromboembolism), and/or that the above-mentioned limitations of telemedicine have decreased diagnostic performance.

Although PPE stockpile data were not easily available for some sites, a distressingly large number reported stockpiles of 2 weeks or less, with reuse being the most common approach to extending PPE supply. We also found it concerning that 43% of hospital leaders did not know their stockpile data; we believe this is an important question that hospital leaders need to be asking. Most sites in our study reported test turnaround times of longer than 6 hours; lack of rapid COVID-19 testing further stresses PPE stockpile and may slow patients’ transition out of the RIU or discharge to home.

Our study has several limitations, including the evolving nature of the pandemic and rapid adaptations of care systems in the pandemic’s surge phase. However, we attempted to frame our questions in ways that provided a focused snapshot of care. Furthermore, respondents may not have had exhaustive knowledge of their institution’s COVID-19 response strategies, but most were the directors of their hospitalist services, and we encouraged the respondents to confer with others to gather high-fidelity data. Finally, as a survey of large academic medical centers, our results may not apply to nonacademic centers.

Approaches to caring for non-ICU patients during the COVID-19 pandemic are rapidly evolving. Expansion of RIUs and developing the workforce to support them has been a primary focus, with rapid innovation in use of technology emerging as a critical adaptation while PPE limitations persist and needs for “medical distancing” continue to grow. Although rates of missed COVID-19 diagnoses will likely be reduced with testing and systems improvements, physicians and systems will also need to consider how to utilize emerging technology in ways that can improve clinical care and provider safety while aiding diagnostic thinking. This survey illustrates the rapid adaptations made by our hospitals in response to the pandemic; ongoing adaptation will likely be needed to optimally care for hospitalized patients with COVID-19 while the pandemic continues to evolve.

Acknowledgment

Thanks to members of the HOMERuN COVID-19 Collaborative Group: Baylor Scott & White Medical Center – Temple, Texas - Tresa McNeal MD; Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center - Shani Herzig MD MPH, Joseph Li MD, Julius Yang MD PhD; Brigham and Women’s Hospital - Christopher Roy MD, Jeffrey Schnipper MD MPH; Cedars-Sinai Medical Center - Ed Seferian MD, ; ChristianaCare - Surekha Bhamidipati MD; Cleveland Clinic - Matthew Pappas MD MPH; Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center - Jonathan Lurie MD MS; Dell Medical School at The University of Texas at Austin - Chris Moriates MD, Luci Leykum MD MBA MSc; Denver Health and Hospitals Authority - Diana Mancini MD; Emory University Hospital - Dan Hunt MD; Johns Hopkins Hospital - Daniel J Brotman MD, Zishan K Siddiqui MD, Shaker Eid MD MBA; Maine Medical Center - Daniel A Meyer MD, Robert Trowbridge MD; Massachusetts General Hospital - Melissa Mattison MD; Mayo Clinic Rochester – Caroline Burton MD, Sagar Dugani MD PhD; Medical College of Wisconsin - Sanjay Bhandari MD; Miriam Hospital - Kwame Dapaah-Afriyie MD MBA; Mount Sinai Hospital - Andrew Dunn MD; NorthShore - David Lovinger MD; Northwestern Memorial Hospital - Kevin O’Leary MD MS; Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center - Eric Schumacher DO; Oregon Health & Science University - Angela Alday MD; Penn Medicine - Ryan Greysen MD MHS MA; Rutgers- Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital - Michael Steinberg MD MPH; Stanford University School of Medicine - Neera Ahuja MD; Tulane Hospital and University Medical Center - Geraldine Ménard MD; UC San Diego Health - Ian Jenkins MD; UC Los Angeles Health - Michael Lazarus MD, Magdalena E. Ptaszny, MD; UC San Francisco Health - Bradley A Sharpe, MD, Margaret Fang MD MPH; UK HealthCare - Mark Williams MD MHM, John Romond MD; University of Chicago – David Meltzer MD PhD, Gregory Ruhnke MD; University of Colorado - Marisha Burden MD; University of Florida - Nila Radhakrishnan MD; University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics - Kevin Glenn MD MS; University of Miami - Efren Manjarrez MD; University of Michigan - Vineet Chopra MD MSc, Valerie Vaughn MD MSc; University of Missouri-Columbia Hospital - Hasan Naqvi MD; University of Nebraska Medical Center - Chad Vokoun MD; University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill - David Hemsey MD; University of Pittsburgh Medical Center - Gena Marie Walker MD; University of Vermont Medical Center - Steven Grant MD; University of Washington Medical Center - Christopher Kim MD MBA, Andrew White MD; University of Washington-Harborview Medical Center - Maralyssa Bann MD; University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics - David Sterken MD, Farah Kaiksow MD MPP, Ann Sheehy MD MS, Jordan Kenik MD MPH; UW Northwest Campus - Ben Wolpaw MD; Vanderbilt University Medical Center - Sunil Kripalani MD MSc, Eduard E Vasilevskis MD, Kathleene T Wooldridge MD MPH; Wake Forest Baptist Health - Erik Summers MD; Washington University St. Louis - Michael Lin MD; Weill Cornell - Justin Choi MD; Yale New Haven Hospital - William Cushing MA, Chris Sankey MD; Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital - Sumant Ranji MD.

1. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. COVID-19 Projections: United States of America. 2020. Accessed May 5, 2020. https://covid19.healthdata.org/united-states-of-america

2. Iserson KV. Alternative care sites: an option in disasters. West J Emerg Med. 2020;21(3):484‐489. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2020.4.47552

3. Paganini M, Conti A, Weinstein E, Della Corte F, Ragazzoni L. Translating COVID-19 pandemic surge theory to practice in the emergency department: how to expand structure [online first]. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2020:1-10. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2020.57

4. Kumaraiah D, Yip N, Ivascu N, Hill L. Innovative ICU Physician Care Models: Covid-19 Pandemic at NewYork-Presbyterian. NEJM: Catalyst. April 28, 2020. Accessed May 5, 2020. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.20.0158

5. Auerbach AD, Patel MS, Metlay JP, et al. The Hospital Medicine Reengineering Network (HOMERuN): a learning organization focused on improving hospital care. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):415-420. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000000139

6. Livingston E, Desai A, Berkwits M. Sourcing personal protective equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic [online first]. JAMA. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.5317

7. Bauchner H, Sharfstein J. A bold response to the COVID-19 pandemic: medical students, national service, and public health [online first]. JAMA. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6166

8. Hollander JE, Carr BG. Virtually perfect? telemedicine for Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1679‐1681. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp2003539

9. Hau YS, Kim JK, Hur J, Chang MC. How about actively using telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic? J Med Syst. 2020;44(6):108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-020-01580-z

10. Smith WR, Atala AJ, Terlecki RP, Kelly EE, Matthews CA. Implementation guide for rapid integration of an outpatient telemedicine program during the COVID-19 pandemic [online first]. J Am Coll Surg. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.04.030

The coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has resulted in a surge in hospitalizations of patients with a novel, serious, and highly contagious infectious disease for which there is yet no proven treatment. Currently, much of the focus has been on intensive care unit (ICU) and ventilator capacity for the sickest of these patients who develop respiratory failure. However, most hospitalized patients are being cared for in general medical units.1 Some evidence exists to describe adaptations to capacity needs outside of medical wards,2-4 but few studies have specifically addressed the ward setting. Therefore, there is a pressing need for evidence to describe how to expand capacity and deliver medical ward–based care.

To better understand how inpatient care in the United States is adapting to the COVID-19 pandemic, we surveyed 72 sites participating in the Hospital Medicine Reengineering Network (HOMERuN), a national consortium of hospital medicine groups.5 We report results of this survey, carried out between April 3 and April 5, 2020.

METHODS

Sites and Subjects

HOMERuN is a collaborative network of hospitalists from across the United States whose primary goal is to catalyze research and share best practices across hospital medicine groups. Using surveys of Hospital Medicine leaders, targeted medical record review, and other methods, HOMERuN’s funded research interests to date have included care transitions, workforce issues, patient and family engagement, and diagnostic errors. Sites participating in HOMERuN sites are relatively large urban academic medical centers (Appendix).

Survey Development and Deployment

We designed a focused survey that aimed to provide a snapshot of evolving operational and clinical aspects of COVID-19 care (Appendix). Domains included COVID-19 testing turnaround times, personal protective equipment (PPE) stewardship,6 features of respiratory isolation units (RIUs; ie, dedicated units for patients with known or suspected COVID-19), and observed effects on clinical care. We tested the instrument to ensure feasibility and clarity internally, performed brief cognitive testing with several hospital medicine leaders in HOMERuN, then disseminated the survey by email on April 3, with two follow-up emails on 2 subsequent days. Our study was deemed non–human subjects research by the University of California, San Francisco, Committee on Human Research. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize survey responses.

RESULTS

Of 72 hospitals surveyed, 51 (71%) responded. Mean hospital bed count was 940, three were safety-net hospitals, and one was a community-based teaching center; responding and nonresponding hospitals did not differ significantly in terms of bed count (Appendix).

Health System Adaptations, Testing, and PPE Status

Nearly all responding hospitals (46 of 51; 90%) had RIUs for patients with known or suspected COVID-19 (Table 1). Nearly all hospitals took steps to keep potentially sick healthcare providers from infecting others (eg, staying home if sick or exposed). Among respondents, 32% had rapid response teams, 24% had respiratory therapy teams, and 29% had case management teams that were dedicated to COVID-19 care. Thirty-two (63%) had developed models, such as ethics or palliative care consult services, to assist with difficult resource-allocation decisions (eg, how to prioritize ventilator use if demand exceeded supply). Twenty-three (45%) had developed post-acute care monitoring programs dedicated to COVID-19 patients.

At the time of our survey, only 2 sites (4%) reported COVID-19 test time turnaround under 1 hour, and 15 (30%) reported turnaround in less than 6 hours. Of the 29 sites able to provide estimates of PPE stockpile, 14 (48%) reported a supply of 2 weeks or less. The most common approaches to PPE stewardship focused on reuse of masks and face shields if not obviously soiled, centralizing PPE distribution, and disinfecting or sterilizing masks. Ten sites (20%) were utilizing 3-D printed masks, while 10% used homemade face shields or masks.

Characteristics of COVID-19 RIUs

Forty-six hospitals (90% of all respondents) in our cohort had developed RIUs at the time of survey administration. The earliest RIU implementation date was February 10, 2020, and the most recent was launched on the day of our survey. Admission to RIUs was primarily based on clinical factors associated with known or suspected COVID-19 infection (Table 2). The number of non–critical care RIU beds among locations at that time ranged from 10 or less to more than 50. The mean number of hospitalist attendings caring for patients in the RIUs was 10.2, with a mean 4.1 advanced practice providers, 5.5 residents, and 0 medical students. The number of planned patients per attending was typically 5 to 15. Nurses and physicians typically rounded separately. Medical distancing (eg, reducing patient room entry) was accomplished most commonly by grouped timing of medication administration (76% of sites), video links to room outside of rounding times (54% of sites), the use of video or telemedicine during rounds (17%), and clustering of activities such as medication administration or phlebotomy. The most common criteria prompting discharge from the RIU were a negative COVID-19 test (59%) and hospital discharge (57%), though comments from many respondents suggested that discharge criteria were changing rapidly.

Effects of Isolation Measures on In-Room Encounters and Diagnostic Processes

More than 90% of sites reported decreases in in-room encounter frequency across all provider types whether as a result of policies in place or not. Reductions were reported among hospitalists, advanced practice providers, residents, consultants, and therapists (Table 3). Reduced room entry most often resulted from an established or developing policy, but many noted reduced room entry without formal policies in place. Nearly all sites reported moving specialty consultations to phone or video evaluations. Diagnostic error was commonly reported, with missed non–COVID-19 medical diagnoses among COVID-19 infected patients being reported by 22 sites (46%) and missed COVID-19 diagnoses in patients admitted for other reasons by 22 sites (45%).

DISCUSSION

In this study of medical wards at academic medical centers, we found that, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, hospitals made several changes in a short period of time to adapt to the crisis. These included implementation and rapid expansion of dedicated RIUs, greatly expanded use of inpatient telehealth for patient assessments and consultation, implementation of other approaches to minimize room entry (such as grouping in-room activities), and deployment of ethics consultation services to help manage issues around potential scarcity of life-saving measures such as ventilators. We also found that availability of PPE and timely testing was limited. Finally, a large proportion of sites reported potential diagnostic problems in the assessment of both patients suspected and those not suspected of having COVID-19.

RIUs are emerging as a primary modality for caring for non-ICU COVID-19 patients, though they never involved medical students; we hope the role of students in particular will increase as new models of training emerge in response to the pandemic.7 In contrast, telemedicine evolved rapidly to hold a substantial role in RIUs, with both ward and specialty teams using video visit technology to communicate with patients. COVID-19 has been viewed as a perfect use case for outpatient telemedicine,8 and a growing number of studies are examining its outpatient use9,10; however, to date, somewhat less attention has been paid to inpatient deployment. Although our data suggest telemedicine has found a prominent place in RIUs, it remains to be seen whether it is associated with differences in patient or provider outcomes. For example, deficiencies in the physical examination, limited face-to-face contact, and lack of physical presence could all affect the patient–provider relationship, patient engagement, and the accuracy of the diagnostic process.

Our data suggest the possibility of missing non–COVID-19 diagnoses in patients suspected of COVID-19 and missing COVID-19 in those admitted for nonrespiratory reasons. The latter may be addressed as routine COVID-19 screening of admitted patients becomes commonplace. For the former, however, it is possible that physicians are “anchoring” their thinking on COVID-19 to the exclusion of other diagnoses, that physicians are not fully aware of complications unique to COVID-19 infection (such as thromboembolism), and/or that the above-mentioned limitations of telemedicine have decreased diagnostic performance.

Although PPE stockpile data were not easily available for some sites, a distressingly large number reported stockpiles of 2 weeks or less, with reuse being the most common approach to extending PPE supply. We also found it concerning that 43% of hospital leaders did not know their stockpile data; we believe this is an important question that hospital leaders need to be asking. Most sites in our study reported test turnaround times of longer than 6 hours; lack of rapid COVID-19 testing further stresses PPE stockpile and may slow patients’ transition out of the RIU or discharge to home.

Our study has several limitations, including the evolving nature of the pandemic and rapid adaptations of care systems in the pandemic’s surge phase. However, we attempted to frame our questions in ways that provided a focused snapshot of care. Furthermore, respondents may not have had exhaustive knowledge of their institution’s COVID-19 response strategies, but most were the directors of their hospitalist services, and we encouraged the respondents to confer with others to gather high-fidelity data. Finally, as a survey of large academic medical centers, our results may not apply to nonacademic centers.

Approaches to caring for non-ICU patients during the COVID-19 pandemic are rapidly evolving. Expansion of RIUs and developing the workforce to support them has been a primary focus, with rapid innovation in use of technology emerging as a critical adaptation while PPE limitations persist and needs for “medical distancing” continue to grow. Although rates of missed COVID-19 diagnoses will likely be reduced with testing and systems improvements, physicians and systems will also need to consider how to utilize emerging technology in ways that can improve clinical care and provider safety while aiding diagnostic thinking. This survey illustrates the rapid adaptations made by our hospitals in response to the pandemic; ongoing adaptation will likely be needed to optimally care for hospitalized patients with COVID-19 while the pandemic continues to evolve.

Acknowledgment